1. Introduction

Healthcare is undergoing a data- and computation-driven transformation across the continuum from prevention to diagnosis, treatment, and pharmacovigilance. Digitized clinical data and electronic health records enable large-scale learning of disease trajectories; imaging and biosignal analytics are increasingly automated; consumer wearables generate continuous real-world physiological streams; and precision-medicine initiatives and FAIR data practices are expanding data linkage and reuse to inform decision making [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. In parallel, the biopharmaceutical enterprise faces persistent productivity headwinds—rising costs, lengthy timelines, and high attrition—often summarized as “Eroom’s law.” These pressures have motivated methodologic and organizational innovations spanning target identification, hit discovery, and translational development [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence are beginning to address several of these bottlenecks. Protein structure prediction now supports target modelling at unprecedented accuracy; generative models accelerate de novo molecular design; and deep learning–driven virtual screening and phenotypic discovery have surfaced candidates with novel mechanisms [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. At the evidence-generation stage, adaptive trial designs and the systematic use of real-world evidence offer complementary pathways for efficient evaluation while maintaining rigor [

9,

20]. The COVID-19 pandemic further demonstrated both the promise and the challenges of data-enabled health systems. Safe and effective mRNA vaccines were delivered on compressed timelines, yet vaccine acceptance varied markedly across populations; county-level clustering analyses and social-behavior studies revealed geographic and sociodemographic heterogeneity relevant to future public-health responses [

4,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Concurrent efforts highlight the importance of reproducibility and generalizability of clinical prediction models in operational settings [

28,

29].

At the point of care, AI systems are advancing diagnostic support across modalities—from cardiologist-level arrhythmia detection in ambulatory ECGs to wavelet-based and deep-learning approaches for cardiovascular classification—illustrating how algorithmic methods can augment clinical decision-making [

2,

30,

31]. Health shocks also reverberate through the life-sciences sector and broader financial markets, underscoring the value of integrated analyses that combine macroeconomic and market indicators with domain-specific context [

32,

33,

34]. Against this backdrop, the development of new drugs remains a cornerstone of modern healthcare and the focal point of the following overview.

1.1. Overview of Healthcare and Drug Development

The development of new drugs is a cornerstone of modern healthcare, playing a critical role in improving public health and extending human lifespan. The pharmaceutical industry continuously strives to discover and develop innovative therapeutic agents that can treat a wide range of diseases and medical conditions, including cancer [

35], infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and COVID-19 [

36,

37], cardiovascular disorders [

38] , neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [

39], and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [

40]. This process, known as drug development, encompasses a series of complex steps, including drug discovery, pre-clinical testing, clinical trials, and regulatory approval [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

The process of drug development is multifaceted and involves several critical stages. It begins with the discovery phase, where potential therapeutic targets are identified, followed by preclinical research that assesses the safety and biological activity of the compounds in vitro and in animal models. Subsequently, clinical research is conducted in human subjects across multiple phases to evaluate the drug’s safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing. Upon successful completion of clinical trials, a comprehensive review is undertaken by regulatory authorities, such as the FDA, to determine the drug’s approval for public use. Even after approval, post-market surveillance is essential to monitor the drug’s performance in the general population and to identify any long-term or rare adverse effects [

46].

This rigorous and systematic approach ensures that new therapeutic agents are both safe and effective, ultimately contributing to the advancement of medical science and the improvement of patient care [

47].

1.2. Importance of Innovative Methods in Drug Discovery and Development

Innovative methods are essential in drug discovery and development to address the increasing demand for new and effective medications [

48]. Traditional drug development methods are often time-consuming, costly, and inefficient, with a high failure rate during clinical trials due to issues such as poor pharmacokinetics, unforeseen toxicity, lack of efficacy, and inadequate drug targeting [

49], and have often encountered significant setbacks during clinical trials due to various factors. For instance, the Alzheimer’s disease drug semagacestat was discontinued in Phase III trials after it was found to worsen cognitive function and increase the risk of skin cancer, highlighting unforeseen toxicity issues [

50]. Similarly, Pfizer’s cholesterol-lowering drug torcetrapib was terminated in Phase III trials due to an unexpected increase in mortality and cardiovascular events among patients, underscoring the challenges of safety in drug development [

51]. Another example is the cancer drug iniparib, which initially showed promise but ultimately failed in Phase III trials due to a lack of efficacy, demonstrating the difficulties in translating early-stage success into clinical benefits [

52]. These cases illustrate the limitations of traditional approaches and emphasize the need for innovative methods to improve the success rates of drug discovery and development. Therefore, there is a significant need for novel approaches that can accelerate the discovery process, reduce costs, and improve the success rates of new drug candidates. Advanced chemical techniques, particularly in catalysis, have emerged as powerful tools in this regard, offering new pathways for the synthesis of complex drug molecules [

53,

54].

Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into drug discovery processes has revolutionized the pharmaceutical industry. These technologies enable the analysis of vast datasets to identify potential drug candidates, predict their efficacy and toxicity, and optimize clinical trial designs, thereby significantly reducing the time and cost associated with drug development [

4,

18,

24,

27,

31,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Additionally, innovative approaches such as organ-on-a-chip technologies and 3D bioprinting have provided more accurate models for human physiology, improving the predictive power of preclinical studies and reducing reliance on animal testing [

61].

1.3. Current Challenges in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Pharmaceutical synthesis faces several challenges, including the need for precise control over chemical reactions, the production of high yields with minimal by-products, and the sustainability of the processes. Efficient catalytic processes are crucial to overcoming these challenges. Catalysts, by increasing the rate of chemical reactions and enhancing selectivity, can significantly streamline the synthesis of drug molecules. This not only improves the efficiency of the synthesis but also reduces the environmental impact and overall costs associated with drug production [

62,

63].

Moreover, the pharmaceutical industry is increasingly adopting green chemistry principles to address environmental concerns associated with traditional synthesis methods. These principles aim to minimize waste, reduce the use of hazardous substances, and improve energy efficiency in chemical processes [

64].

One significant advancement in this area is the implementation of solvent-free reactions, which eliminate the need for harmful organic solvents, thereby reducing waste and exposure to toxic chemicals [

65].

Additionally, biocatalysis has emerged as a powerful tool in sustainable pharmaceutical synthesis. By utilizing enzymes as catalysts, biocatalysis offers high selectivity and operates under mild conditions, leading to safer and more environmentally friendly processes [

66].

Furthermore, continuous flow chemistry is gaining traction as it allows for better control over reaction parameters, scalability, and integration of multi-step syntheses, enhancing both efficiency and safety in drug manufacturing [

67].

1.4. Role of Catalysis in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

The synthesis of complex drug molecules often involves multiple steps, each requiring precise control over the reaction conditions. Catalytic processes can simplify these synthetic routes by providing a direct and efficient means of forming key chemical bonds. For example, catalytic hydrogenation, oxidation, and carbon-carbon coupling reactions are widely used in the pharmaceutical industry to construct the intricate molecular architectures of many drugs. The use of advanced catalytic techniques can also enable the synthesis of novel drug molecules with enhanced therapeutic properties [

68]. Successful drugs developed through advanced catalytic processes include the anti-cancer drug paclitaxel (Taxol) [

69] and the HIV protease inhibitor indinavir (Crixivan) [

36,

70], demonstrating catalysis’s transformative impact on drug development.

Several successful drugs have been developed through the use of advanced catalytic processes. For instance, the anti-cancer drug paclitaxel (Taxol) was synthesized using a catalytic process that allowed for the efficient construction of its complex molecular structure [

69]. Similarly, the HIV protease inhibitor indinavir (Crixivan) was developed using catalytic hydrogenation, which played a crucial role in the synthesis of its active ingredient [

36,

70]. These examples illustrate the transformative impact of catalysis in drug development, leading to the creation of life-saving medications.

Catalytic processes are integral to the synthesis of many complex drug molecules. They facilitate the formation of chemical bonds in a controlled and efficient manner, essential for pharmaceutical production. Catalysts help achieve reactions otherwise difficult or impossible under standard conditions. In drug synthesis, catalysts lead to more efficient, sustainable processes, enabling the production of drugs with higher purity and larger quantities [

62,

71,

72].

Catalysis plays a pivotal role in modern pharmaceutical synthesis by enabling more efficient and sustainable chemical transformations. The application of catalysis in drug development has led to significant advancements in the synthesis of complex molecules, improving yields and selectivity while reducing environmental impact [

62].

One notable example is the synthesis of the anti-cancer drug paclitaxel (Taxol), which employs a semisynthetic route starting from 10-deacetylbaccatin III, a compound extracted from yew trees. This process utilizes catalytic steps to construct the complex taxane core, demonstrating the power of catalysis in assembling intricate molecular architectures [

73].

Similarly, the HIV protease inhibitor indinavir (Crixivan) was developed using catalytic asymmetric synthesis techniques to establish the necessary stereochemistry, highlighting the importance of catalysis in producing enantiomerically pure pharmaceuticals [

74].

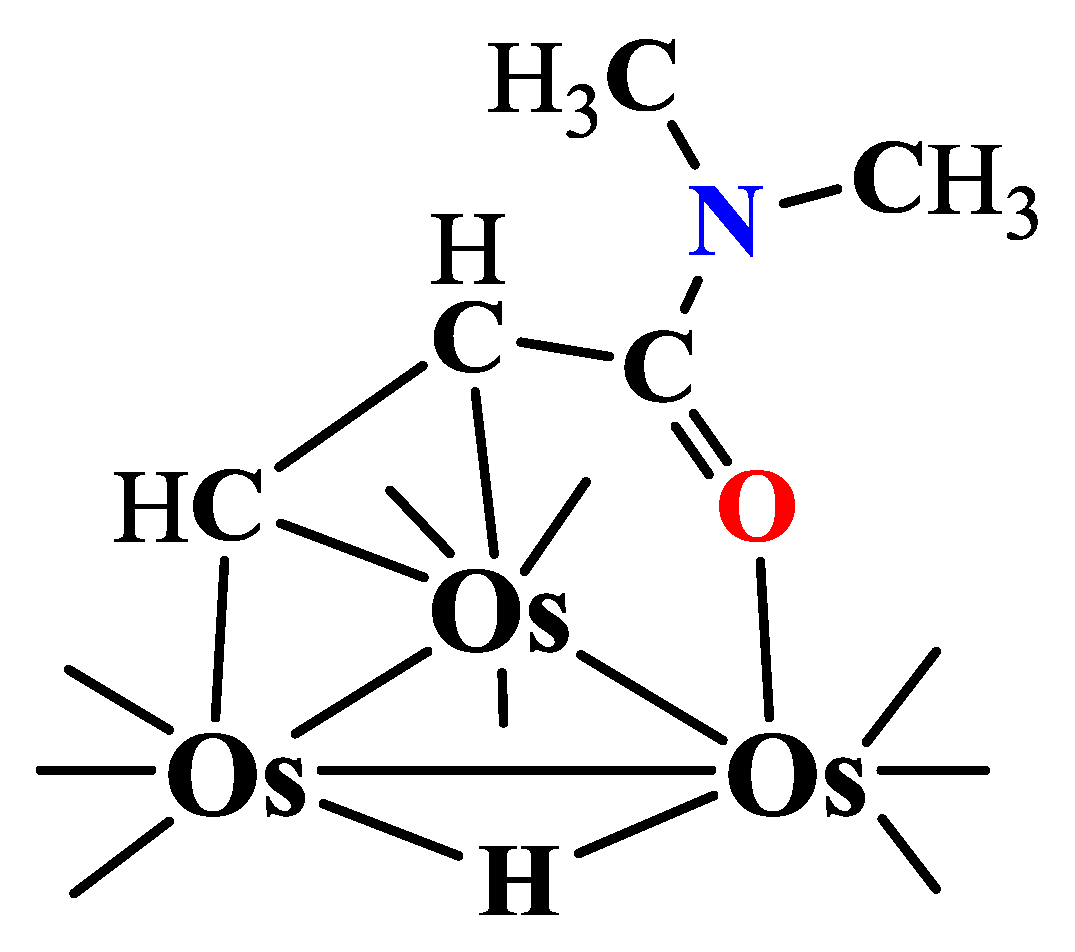

An illustrative example of catalytic C–H activation relevant to pharmaceutical synthesis involves osmium(II)-catalyzed functionalization of benzoic acids, as shown below:

This example demonstrates the use of osmium(II) catalysts in the selective activation of aromatic C–H bonds, providing a valuable synthetic route toward pharmaceutical intermediates [

75].

Advancements in catalytic methodologies, including transition metal catalysis, organocatalysis, and biocatalysis, have expanded the toolkit available for pharmaceutical synthesis. These approaches have facilitated the development of more efficient synthetic routes, enabling the rapid and cost-effective production of active pharmaceutical ingredients [

76].

Overall, the integration of catalysis into pharmaceutical synthesis continues to drive innovation, allowing for the creation of complex drug molecules with improved efficiency, selectivity, and sustainability.

1.5. Trinuclear Metal Carbonyl Clusters and Their Symmetrical Properties

Trinuclear metal carbonyl clusters, particularly osmium-based clusters, exhibit unique symmetrical properties making them effective catalysts. These clusters, arranged symmetrically with carbonyl ligands for stability, uniformly activate C-H bonds in substrates, enabling efficient, selective catalytic transformations. For example, osmium clusters like Os

3(CO)

12 have shown remarkable catalytic properties due to their symmetric configuration and electron-rich nature, facilitating robust activation of C-H bonds and subsequent carbon-carbon bond formation. Their activation of C-H bonds in unsaturated amides and esters is particularly relevant for pharmaceutical synthesis, where precise functionalization is required [

77,

78,

79].

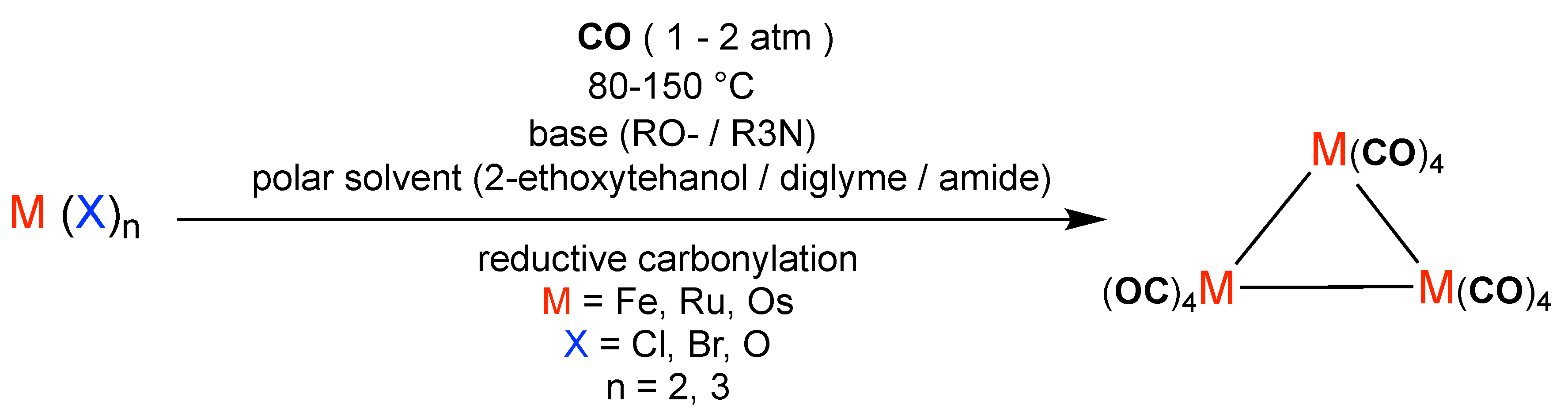

Trinuclear metal carbonyl clusters (M

3(CO)

12) can be synthesized through the reductive carbonylation of simple metal precursors under a carbon monoxide atmosphere. In a generic route (Figure X), metal halides or oxo complexes (M–X

n, where M = Fe, Ru, Os and X = halide or oxo,

–4) are treated with CO in the presence of a base (alkoxide or tertiary amine) and an appropriate polar solvent at elevated temperature (80–150

C) and pressure (1–20 atm CO). Under these conditions, the anionic ligands are displaced and the zero-valent trinuclear cluster M

3(CO)

12 is formed, often accompanied by salts or HX by-products. This reaction pathway highlights the fundamental strategy for assembling trinuclear carbonyl clusters, while allowing for subsequent ligand substitution (M

3) or bridging ligand incorporation (

-E, L = phosphine, E = main-group donor) to generate structurally diverse derivatives.

Figure 1 summarises this approach.

1.6. Symmetry in Chemical Catalysis

Symmetry plays a vital role in chemical catalysis, influencing the efficiency and selectivity of catalytic reactions. Symmetrical molecules and catalytic clusters can provide uniform environments that facilitate the formation of desired reaction products. In particular, the symmetrical arrangement of atoms in catalytic clusters can lead to enhanced catalytic activity and stability, making them ideal for use in pharmaceutical synthesis [

80,

81,

82].

In chemical reactions, symmetry can lead to more predictable and controlled outcomes. Symmetrical catalysts can provide uniform activation sites, reducing the likelihood of side reactions and improving the overall selectivity of the process. This is especially important in the synthesis of drug molecules, where the purity and specificity of the product are critical. Symmetry in catalysis can also contribute to the stability of the catalytic complexes, prolonging their active lifetimes and making the processes more efficient [

81,

82].

A prominent example of symmetrical catalysis is the use of C

2-symmetric ligands in asymmetric hydrogenation reactions, represented generally as:

Such symmetric ligands significantly enhance enantioselectivity, which is critical in synthesizing chiral pharmaceuticals with high purity and efficacy [

83].

1.7. Metal Catalyzed C-H Activation and Its Applications

The selective transformation of ubiquitous but unreactive C-H bonds to other functional groups has far-reaching practical implications, ranging from more efficient strategies for fine chemical synthesis to the replacement of current petrochemical feedstocks by less expensive and more readily available alkanes. Metal-catalyzed C-H bond activation and subsequent addition of the activated species to unsaturated compounds constitute one of the most economical and efficient methods in organic synthesis. This process is particularly valuable in the functionalization of unsaturated compounds into carbonyl-containing molecules, such as in transition metal-catalyzed hydroacylation, hydroesterification, hydrocarbamoylation, and hydroarylation [

84,

85].

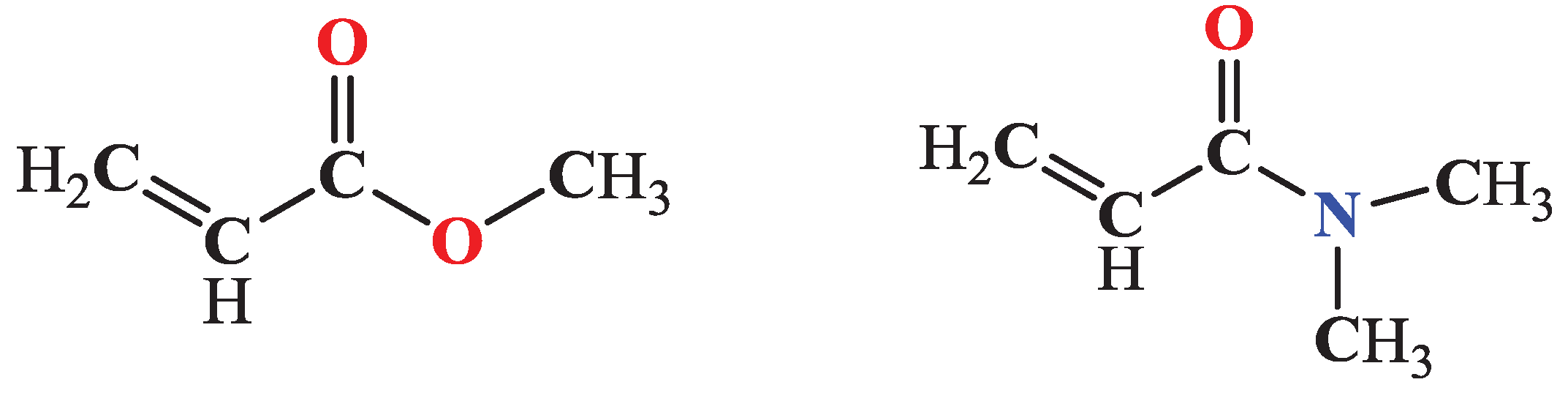

Figure 2 illustrates the molecular structures of methyl acrylate (MA) and

N,N-dimethyl-acrylamide (DMA), two key unsaturated compounds frequently used in industrial and pharmaceutical applications. The functionalization of such compounds through C-H activation can lead to the synthesis of more complex molecules with diverse applications in the chemical industry, pharmaceuticals, and organic research.

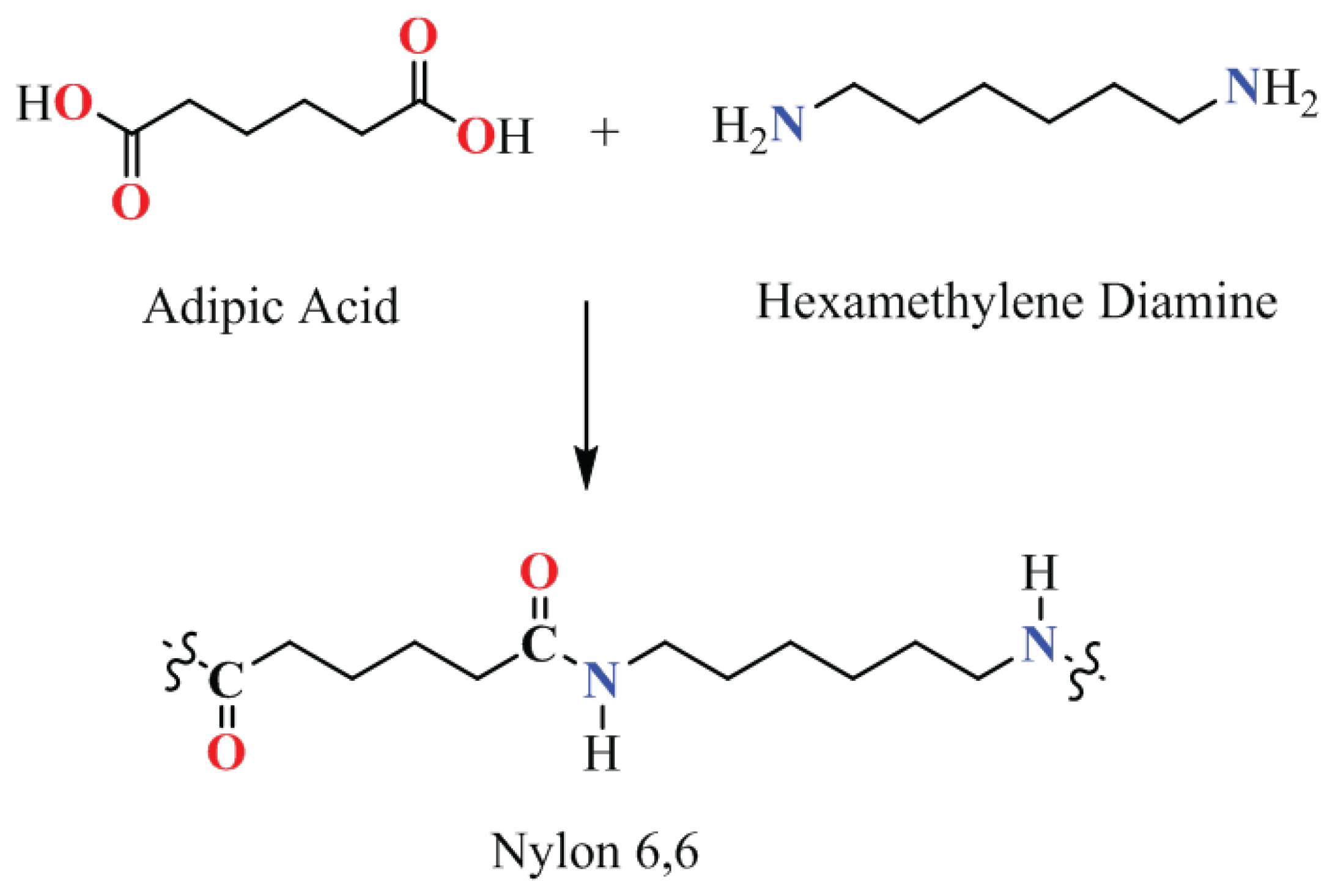

In the realm of industrial manufacturing, condensation polymers such as polyesters and polyamides are of great importance. Nylon, a prominent polyamide, has numerous applications due to its high durability and strength.

Figure 3 showcases the synthesis pathway of Nylon 6,6 from adipic acid and hexamethylene diamine. This synthesis pathway underscores the significance of efficient catalytic processes in producing valuable polymeric materials.

Adipic acid, which can be derived from the dimerization of MA, is a crucial intermediate in the production of nylon and polyurethanes. The industrial synthesis of adipic acid typically involves a mixture of nitric acid, cyclohexanone, and cyclohexanol, producing nitrous oxide as a byproduct, which is detrimental to the environment [

86]. Recent efforts to employ transition metals in adipic acid synthesis aim to improve green chemistry and reduce harmful byproducts [

87]. The ability to activate C-H bonds in simpler unsaturated hydrocarbons and convert them to valuable compounds like adipic acid highlights the potential of transition metal-catalyzed processes in enhancing both efficiency and environmental sustainability in chemical manufacturing. Furthermore, the activation and dimerization of olefins such as MA have been extensively studied using transition metal clusters of Pd, Ru, Pt, and Rh [

88]. These processes not only facilitate the synthesis of industrially important compounds like adipic acid but also play a vital role in pharmaceutical applications, offering new pathways for drug synthesis [

87,

88]. The unique C-H activation and dimerization of DMA using osmium trimetallic carbonyl clusters, as explored in this study, further demonstrate the versatility and potential of these catalytic processes in advancing drug discovery and development.

An illustrative osmium-based catalytic C–H activation involves aromatic substrates, described as follows:

This osmium-promoted transformation highlights osmium hexahydride complexes’ ability to efficiently activate aromatic C–H bonds, enabling streamlined pathways to complex aromatic pharmaceuticals [

89].

Recent advancements in transition-metal-catalyzed C–H activation have significantly expanded the toolkit available for constructing complex molecules. For instance, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium catalysts have been employed to achieve site-selective functionalization of C–H bonds, enabling the synthesis of diverse chemical architectures with high precision [

90].

Furthermore, the development of directing groups has facilitated the activation of specific C–H bonds in the presence of multiple reactive sites, enhancing the regioselectivity of these transformations [

91].

In addition to traditional transition metals, recent studies have explored the use of earth-abundant metals such as manganese and iron in C–H activation processes, aiming to improve the sustainability and cost-effectiveness of these methodologies [

92].

These advancements underscore the pivotal role of metal-catalyzed C–H activation in modern synthetic chemistry, offering streamlined routes to complex molecules and contributing to the development of more sustainable chemical processes.

In summary, the advancements in metal-catalyzed C-H activation and functionalization of unsaturated compounds offer promising avenues for both industrial and pharmaceutical applications. The figures provided illustrate key examples of such transformations, emphasizing their practical significance and potential for broadening the scope of catalytic processes in various fields.

1.8. C-H Activation in Drug Synthesis

C-H activation is a powerful tool in the synthesis of drug molecules, enabling the direct functionalization of carbon-hydrogen bonds. This process is crucial for the construction of complex molecular structures found in many pharmaceuticals. By selectively activating C-H bonds, chemists can introduce various functional groups into drug molecules, enhancing their biological activity and therapeutic potential [

90,

93,

94,

95].

The ability to activate C-H bonds opens up new possibilities for the design and synthesis of novel drug molecules. C-H activation allows for the direct modification of existing chemical structures, facilitating the rapid development of new therapeutic agents. This approach can also streamline synthetic routes, reducing the number of steps required to produce complex drug molecules and improving overall efficiency.

1.9. Role of Osmium in Catalytic C–H Activation

Osmium, a member of the platinum group metals, has garnered significant attention in the field of catalysis due to its unique electronic properties and ability to facilitate a variety of chemical transformations. Its high oxidation states and the formation of stable complexes make it an effective catalyst in numerous organic reactions, including those involving C–H bond activation [

96].

One of the most notable applications of osmium in catalysis is in the dihydroxylation of olefins. The Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation, which employs osmium tetroxide in conjunction with chiral ligands, has become a cornerstone in the synthesis of enantiomerically pure vicinal diols, compounds that are pivotal in the development of various pharmaceuticals [

97].

Beyond dihydroxylation, osmium complexes have demonstrated efficacy in hydrogenation reactions. Recent studies have shown that osmium-based catalysts can achieve high levels of activity and selectivity in the hydrogenation of unsaturated substrates, offering potential advantages over traditional catalysts in terms of reaction conditions and product yields [

96].

Triosmium dodecacarbonyl, Os

3(CO)

12, is synthesized by the reaction of osmium tetroxide (OsO

4) with carbon monoxide (CO) under conditions of high pressure and elevated temperature. The reaction is represented by the following equation:

This synthesis typically employs reaction conditions of approximately 175 °C and a carbon monoxide pressure of around 190 atmospheres, using a solvent such as xylene. The product, Os

3(CO)

12, forms as yellow crystals that can be purified through recrystallization from benzene. This method, providing an improved route to osmium carbonyl clusters, was first detailed by Bradford in 1967 [

98]. The molecular and crystal structure of Os

3(CO)

12 was first elucidated by Corey and Dahl in 1962, providing detailed structural insights into the cluster arrangement and carbonyl ligand bonding [

99].

In the realm of C–H activation, osmium’s ability to form multiple bonds with carbon and other ligands allows for the activation of otherwise inert C–H bonds. This capability is particularly valuable in the functionalization of hydrocarbons, enabling the direct transformation of simple molecules into more complex structures without the need for pre-functionalization [

97].

Furthermore, osmium’s role in catalysis extends to its incorporation into bimetallic complexes. For instance, osmium–tin and osmium–germanium carbonyl complexes have been explored for their unique reactivities and potential applications in organic synthesis [

100]. These bimetallic systems can offer synergistic effects, enhancing catalytic performance and selectivity.

The versatility of osmium in catalysis, particularly in C–H activation processes, underscores its potential in advancing pharmaceutical synthesis. By enabling more efficient and selective transformations, osmium-based catalysts can contribute to the development of novel therapeutic agents and the improvement of existing drug synthesis pathways.

1.10. Objective of the Study

This study aims to explore the application of symmetrical catalysis in drug development through the activation of C-H bonds in unsaturated amides and esters by trinuclear metal carbonyl clusters of Osmium. The objective is to demonstrate how these advanced catalytic techniques can enhance the efficiency and selectivity of drug synthesis, ultimately contributing to the development of new therapeutic agents. By providing a detailed analysis of the catalytic processes and their symmetrical properties, this research seeks to highlight the transformative impact of C-H activation on pharmaceutical synthesis and healthcare.

Building upon this foundation, our investigation delves into the unique symmetrical properties of trinuclear osmium clusters and their role in facilitating selective C–H activation in unsaturated amides and esters. By examining the mechanistic pathways and catalytic efficiencies of these symmetrical systems, we aim to elucidate how such configurations influence reaction outcomes. This study seeks to bridge the gap between structural symmetry in catalysis and its practical applications in synthesizing complex pharmaceutical compounds, thereby contributing to the advancement of efficient and sustainable drug development methodologies.

2. Literature Review

Previous research on C–H activation has demonstrated its potential to revolutionize drug synthesis. Studies have shown that C–H activation can be used to construct key structural motifs in pharmaceuticals, such as aromatic rings and heterocycles [

101]. These motifs are common in many drug molecules and are often challenging to synthesize using traditional methods. By leveraging C–H activation, researchers have developed more efficient and versatile synthetic strategies, leading to the discovery of new drugs and the improvement of existing ones.In medicinal chemistry, late–stage functionalization (LSF) built on C–H activation has become a mainstream strategy to diversify leads quickly, map structure–activity relationships, and modulate physicochemical properties without route redesign [

102,

103]. Broad, mechanism-grounded reviews now document how directed, undirected, photochemical, electrochemical, and enzymatic C–H methods enable transformations directly on druglike scaffolds [

104,

105,

106].

Symmetrical catalysis has gained significant attention in recent years due to its potential to enhance the efficiency and selectivity of chemical reactions. The symmetrical arrangement of atoms in catalytic complexes often leads to uniform reaction environments, reducing side reactions and improving product yields.In particular,

C2-symmetric ligand architectures (e.g., bisphosphines, bis(oxazolines), semicorrins) reduce the number of competing transition states and are a classic route to higher enantioselectivity and robustness [

107,

108]. Trinuclear metal carbonyl clusters, such as Os

3(CO)

12, Ru

3(CO)

12, and Fe

3(CO)

12, display high (pseudo-)symmetry (often D

3 or

) and have been exploited as (pre)catalysts or model platforms in homogeneous catalysis, with documented applications spanning hydrofunctionalizations and C–H transformations [

109,

110,

111].

Recent advances in symmetrical catalysis have demonstrated its broad applicability across different fields of chemistry. For instance, the use of symmetrical ligands in transition metal catalysis has been shown to enhance enantioselectivity in asymmetric synthesis, which is crucial for the production of chiral pharmaceuticals.Foundational analyses show how C

2 symmetry simplifies stereochemical manifolds and favors matched pathways in enantioselective catalysis [

107,

108]. Additionally, symmetrical catalysis has been leveraged in the development of new materials with unique electronic and optical properties, further expanding its potential applications .Symmetric scaffolds also underpin stereodirecting pincer and tripod ligands used in selective transformations relevant to materials precursors [

108].

Catalysis plays a pivotal role in drug development, enabling the efficient synthesis of complex drug molecules. The pharmaceutical industry has increasingly adopted advanced catalytic techniques to streamline drug synthesis, reduce costs, and improve the overall efficiency of production processes. Notably, the development of catalytic methods for C–H activation has revolutionized the field of drug synthesis by allowing for the direct functionalization of carbon–hydrogen bonds, which are abundant in organic molecules [

112].Comprehensive surveys highlight preparative-scale deployments (up to multi-kilogram) of C–H steps in discovery and development settings [

113], while modern LSF workflows integrate high-throughput experimentation and data-guided site-selectivity prediction [

103].

C–H activation has emerged as a powerful tool in drug synthesis, facilitating the introduction of functional groups into drug molecules in a highly controlled manner. This approach has been particularly valuable for the construction of complex molecular architectures that are often found in pharmaceuticals. Recent studies have demonstrated the utility of C–H activation in the synthesis of various drugs, highlighting its impact on the pharmaceutical industry. Instead, representative

validated applications include (i) preparative-scale direct arylations and olefinations to build biaryl or alkenyl motifs common in leads [

114,

115]; (ii) meta-selective LSF to tune electronics and ADME on advanced drug scaffolds [

116]; and (iii) streamlined access to key nucleoside precursors for antivirals via catalytic C-glycosylation followed by site-selective C–H oxidation [

117].

Note: flow-optimized two-step routes to marketed drugs like olaparib exist, but are not predicated on C–H activation per se.

As of 2025, significant progress has been made in the field of symmetrical catalysis and its application in drug development. New catalytic systems have been developed that offer even greater selectivity and efficiency in C–H activation processes. For instance, a recent study reported the use of rhodium clusters to facilitate aerobic hydrocarbon oxidative functionalization, aiding in the oxidative coupling of benzene and ethylene to form styrene. This catalytic process facilitates the synthesis of alkyl and alkenyl arenes, which can be used as precursors in pharmaceutical drug development [

118].Beyond the classic report, advances now address selectivity and sustainability in the benzene–ethylene oxidative coupling to styrene, including single-step strategies and mechanism-guided catalyst design [

119,

120]. In parallel,

mild C–H activation concepts (e.g., carboxylate-assisted CMD, redox-economical oxidants) have expanded functional-group tolerance critical for LSF [

121]. Photochemical decatungstate HAT and electrochemical C–H platforms provide orthogonal handles for late-stage sp

3 and sp

2 functionalization on complex molecules [

105,

106,

122].

In the pharmaceutical industry, C–H activation continues to drive innovation in drug synthesis. The development of new drugs for treating cancer, infectious diseases, and neurological disorders has been significantly accelerated by advancements in C–H activation techniques. Recent reviews catalog numerous LSF case studies across therapeutic areas and modalities (including peptides and nucleosides), emphasizing scalability and property modulation rather than total synthesis heroics [

103,

113].

The Fujiwara–Moritani reaction exemplifies a palladium-catalyzed oxidative coupling between arenes and olefins, facilitating C–H activation without prefunctionalization [

123,

124,

125].:

This method is valuable for installing vinyl groups directly onto (hetero)arenes; modern ligand/oxidant systems and directing groups expand selectivity and scope for LSF [

123].

The Murai reaction involves ruthenium-catalyzed addition of aromatic C–H bonds to alkenes (chelation-assisted hydroarylation) [

126,

127].:

Classically, Ru0 precursors (often generated from Ru3(CO)12) are used; related RuH2(CO)(PPh3)3 systems are also competent. The reaction provides a direct, protecting-group-sparing route to alkylated arenes and has been adapted to flow and greener protocols.

The Shilov system demonstrates platinum-catalyzed functionalization of methane to methanol via C–H activation [

128]:

This landmark system established key principles of alkane C–H activation relevant to modern oxidations and late-stage aliphatic functionalization.

C–H activation strategies are widely employed to build biaryls directly (“direct arylation”) using aryl halides under palladium catalysis [

114,

115].:

Direct (H/X) arylation avoids pre-made organoborons, shortens routes, and is established on druglike heterocycles, including scale-up examples [

113,

114].

Finally, complementary modalities broaden the LSF toolbox: decatungstate-mediated HAT for benzylic and unactivated C(sp

3)–H functionalization [

122], and electrocatalytic C–H functionalization (often paired with H

2 evolution) for C–N/C–C bond formations under mild conditions [

106]. These developments interface naturally with symmetry-guided catalyst design and with symmetric cluster platforms that provide uniform microenvironments for selective transformations [

109,

110].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Details

All chemicals were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification unless otherwise stated. Osmium carbonyl complexes, including Os3(CO)12, were sourced from STREM Chemicals. Reagent grade solvents, including methylene chloride, hexane, and heptane, were dried using standard methods and freshly distilled prior to use. N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) and methyl acrylate (MA) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. All reactions were conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere. Infrared spectra were recorded using a Thermo Nicolet Avatar 360 FT-IR spectrophotometer. 1H NMR and 31P NMR spectra were measured on a Varian Mercury 300 spectrometer at 300.1 MHz. Mass spectrometric (MS) measurements were performed with a VG 70S instrument using a direct-exposure probe with electron impact ionization (EI), and positive/negative ion mass spectra were acquired on a Micromass Q-TOF instrument using electrospray (ES) ionization. Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)213 was prepared according to previously published procedures. Product isolations were carried out by TLC in air using Analtech 0.50 mm silica gel 60 Å F254 glass plates and Analtech 0.25 mm aluminum oxide UV254 glass plates.

3.2. Synthetic Procedures

3.2.1. Synthesis of Trinuclear Metal Carbonyl Clusters

The synthesis of Os

3(CO)

10(NCCH

3)

2 was carried out following previously reported procedures [

129] with minor modifications. The detailed procedure is as follows:

A mixture of Os3(CO)12 (100 mg, 0.11 mmol) and trimethylamine N-oxide (25 mg, 0.33 mmol) was dissolved in 50 mL of methylene chloride in a 100 mL three-neck flask.

The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 hours under a nitrogen atmosphere.

After completion of the reaction, as indicated by IR spectroscopy, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure.

The resulting product, Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2, was purified by column chromatography using a mixture of hexane and methylene chloride (3:1) as the eluent.

3.2.2. Experimental Procedures

The experimental procedures for conducting C-H activation experiments were as follows:

3.2.3. General Procedure for C-H Activation

-

Os3(CO)10

(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was added to a 100 mL three-neck flask containing 60 mL of solvent (heptane or methylene chloride).

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) or methyl acrylate (MA) was added to the reaction mixture in a molar ratio of 1:5 or 1:2 with respect to the osmium complex.

The reaction mixture was heated to reflux with stirring for the specified time (7-12 hours) under a nitrogen atmosphere.

The progress of the reaction was monitored by IR spectroscopy.

Upon completion, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the products were isolated by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using a mixture of hexane and methylene chloride (3:1 or 1:1) as the eluent.

3.2.4. Synthesis of Specific Activated Compounds

-

Synthesis of Os2(CO)6(µ-H)(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH), 1:

-

Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was reacted with

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) (42.5 mg, 0.428 mmol) in 60 mL of heptane for 7 hours.

The product was isolated by TLC, yielding 13.1 mg (16.3%) of yellow Os2(CO)6(µ-H)(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH).

Solvent use rationale: Heptane is non-polar and non-coordinating with a higher b.p. (98

C), enabling hot reflux to drive C–H activation while avoiding competitive solvent binding to osmium.

-

Synthesis of Os4(CO)12(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH)2, 2:

-

Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was reacted with

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) (144.3 mg, 1.45 mmol) in 60 mL of methylene chloride for 12 hours.

The product was isolated by TLC, yielding 12.3 mg (15.4%) of Os4(CO)12(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH)2.

Solvent use rationale: Methylene chloride (CH

2Cl

2) is moderately polar and weakly coordinating with excellent solubility for Os carbonyl clusters; its low b.p. (40

C) allows gentle rt/reflux conditions that control reactivity and limit over-decarbonylation.

-

Synthesis of Os3(CO)9(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CH2CHCCHC(N(CH3)2)=O), 3:

-

Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was reacted with

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) (42.5 mg, 0.428 mmol) in 60 mL of heptane for 7 hours.

The product was isolated by TLC, yielding 23.0 mg (28.8%) of yellow Os3(CO)9(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CH2CHCCHC(N(CH3)2)=O).

Solvent use rationale: Heptane is non-polar and non-coordinating with a higher b.p. (98

C), enabling hot reflux to drive C–H activation while avoiding competitive solvent binding to osmium.

-

Synthesis of Os3(CO)8(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH)2, 4:

-

Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was reacted with

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) (144.3 mg, 1.45 mmol) in 60 mL of methylene chloride for 12 hours.

The product was isolated by TLC, yielding 5.0 mg (6.2%) of yellow Os3(CO)8(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2) CHCH)2.

Solvent use rationale: Methylene chloride (CH

2Cl

2) is moderately polar and weakly coordinating with excellent solubility for Os carbonyl clusters; its low b.p. (40

C) allows gentle rt/reflux conditions that control reactivity and limit over-decarbonylation.

-

Synthesis of Os6(CO)20(µ-H)(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH)2, 5:

-

Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was reacted with

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) (144.3 mg, 1.45 mmol) in 60 mL of methylene chloride for 12 hours.

The product was isolated by TLC, yielding 18.2 mg (22.5%) of Os6(CO)20(µ-H)(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2) CHCH)2.

Solvent use rationale: Methylene chloride (CH

2Cl

2) is moderately polar and weakly coordinating with excellent solubility for Os carbonyl clusters; its low b.p. (40

C) allows gentle rt/reflux conditions that control reactivity and limit over-decarbonylation.

-

Synthesis of HOs3(CO)10(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH), 6:

-

Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was reacted with

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) (192.4 mg, 1.94 mmol) in 30 mL of methylene chloride at room temperature for 2 hours.

The product was isolated by TLC, yielding 55.8 mg (69.1%) of yellow HOs3(CO)10(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH).

Solvent use rationale: Methylene chloride (CH

2Cl

2) is moderately polar and weakly coordinating with excellent solubility for Os carbonyl clusters; its low b.p. (40

C) allows gentle rt/reflux conditions that control reactivity and limit over-decarbonylation.

-

Synthesis of Os5(CO)15(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH)2, 7:

HOs3(CO)10(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH), 6 (30 mg, 0.032 mmol) was added to a NMR tube containing a solution of trimethylamine N-oxide (4.0 mg, 0.04 mmol) in 3 mL d-methylene chloride.

The reaction mixture was placed in an oil bath at 45C for 7 days with intermittent monitoring by NMR spectroscopy.

The solvent was then removed by evaporation at room temperature, and the product was isolated by TLC using a mixture of hexane and methylene chloride (1:1) as the eluent.

In order of elution, the products were: 3.0 mg of yellow Os3(CO)12 (10.34% yield), 5 mg of Os2(CO)6(µ-H)(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH), 1 (24.13% yield), and 10.2 mg of Os5(CO)15(µ-O=C(N(CH3)2)CHCH)2 (20.71% yield).

Solvent use rationale:d-Methylene chloride (CD

2Cl

2) is the deuterated analogue chosen for in-tube NMR monitoring over days, providing the same solvation as CH

2Cl

2 with minimal background signals.

-

Synthesis of Os3(CO)9(µ-H)(µ-O=C(OCH3)CHCH), 8:

Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 (80 mg, 0.085 mmol) was added to a 100 mL three-neck flask containing a solution of methyl acrylate (CH3OCOCHCH2) (36.91 mg, 0.42 mmol) in 60 mL hexane.

The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at reflux for 3 hours with intermittent monitoring by IR spectroscopy.

The solvent was then removed in vacuo, and the product was isolated by TLC using a mixture of hexane and methylene chloride (3:1) as the eluent.

-

In order of elution, the products were: 5.0 mg of yellow known compound Os3(CO)11(µ-H)(µ-Cl) (6.25% yield), 6.1 mg of yellow known compound

Os3(CO)12(µ-H)(µ-OH) (7.63% yield), and 23 mg of yellow Os3(CO)9(µ-H)(µ-O=C(OCH3)CHCH) (28.75% yield).

Solvent use rationale: Hexane is non-polar and non-coordinating with a moderate b.p. (69

C), supporting clean reflux with methyl acrylate while avoiding donor interference at the metal center.

Additional information in regard to Synthetic Information A.1, Analyticsl Techniques A.2, ORTEP Visualizations of compounds A.3, and Crystallographic Analyses A.4 are provided in the Supplementary Materials section A and have been discussed extensively.

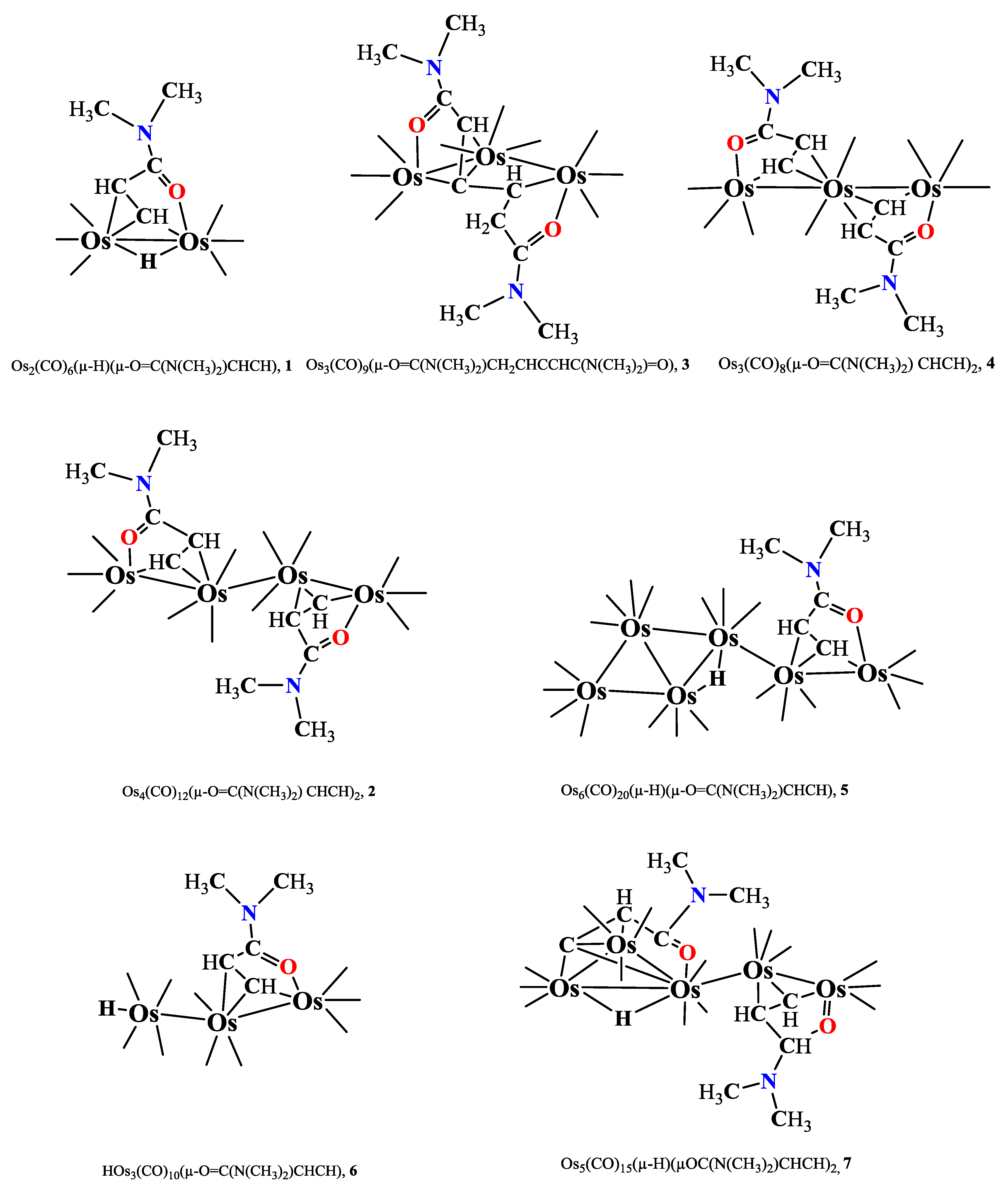

Figure 4.

Line structures of CH-activated osmium cluster compounds obtained from reactions of Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 and DMA.

Figure 4.

Line structures of CH-activated osmium cluster compounds obtained from reactions of Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 and DMA.

4. Results

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA), with the formula (CH

3)

2NC(=O)CHCH

2, is a clear, colorless to yellowish liquid with a boiling point of 171.0 ºC and a density of 0.964 g/cm

3. DMA is an unsaturated amide containing one

-hydrogen and two

-hydrogens along with a double bond between the

- and

-carbons. The compound Os

3(CO)

10(NCCH

3)

2, an activated form of Os

3(CO)

12,was prepared by Me

3NO–mediated decarbonylation of Os

3(CO)

12 in CH

2Cl

2/CH

3CN at rt, following a standard literature protocol [

130]; IR monitoring was used to confirm consumption of Os

3(CO)

12. It can be synthesized by reacting Os

3(CO)

12 with trimethylamine

N-oxide in a solvent mixture of methylene chloride and acetonitrile at room temperature over 2 hours, yielding nearly 100% conversion.

Upon reacting Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 with DMA, seven CH-activated osmium cluster compounds were obtained, depicted in Scheme 1.1. These include one Os2, three Os3, one Os4, one Os5, and one Os6 clusters, incorporating activated DMA. Among these, compounds 1, 5, and 7 feature bridging hydrides, while compound 6 includes a terminal hydride ligand.

4.1. Mechanistic Pathways and Transformations

The mechanism proposed for the transformation of Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2 into the activated products involves the decarbonylated form of Os3(CO)12, being electron-deficient, reacting readily with DMA. The oxygen atom in the carbonyl group of DMA directs the initial coordination, facilitating the activation of - and -hydrogens on the vinyl group.

Upon interaction with the decarbonylated osmium metal atoms, the oxygen atom in the carbonyl group of DMA first approaches and binds to the osmium atom, acting as a directing group. This coordination brings the remainder of the DMA molecule closer to the metal center, providing the grounds for the activation of - and -hydrogen atoms on the vinyl group ().

Once DMA approaches the activated Os3 cluster, its vinyl group (C2H3) coordinates to the osmium atom initially approached by the oxygen atom of DMA (). The transition metal forms a bond with the -hydrogen atom through a six-membered ring (Os-O-C-C-C-H), facilitating the activation and ultimate activation of the -hydrogen atom. This ring is more stable compared to a five-membered ring intermediate for the activation of the -hydrogen.

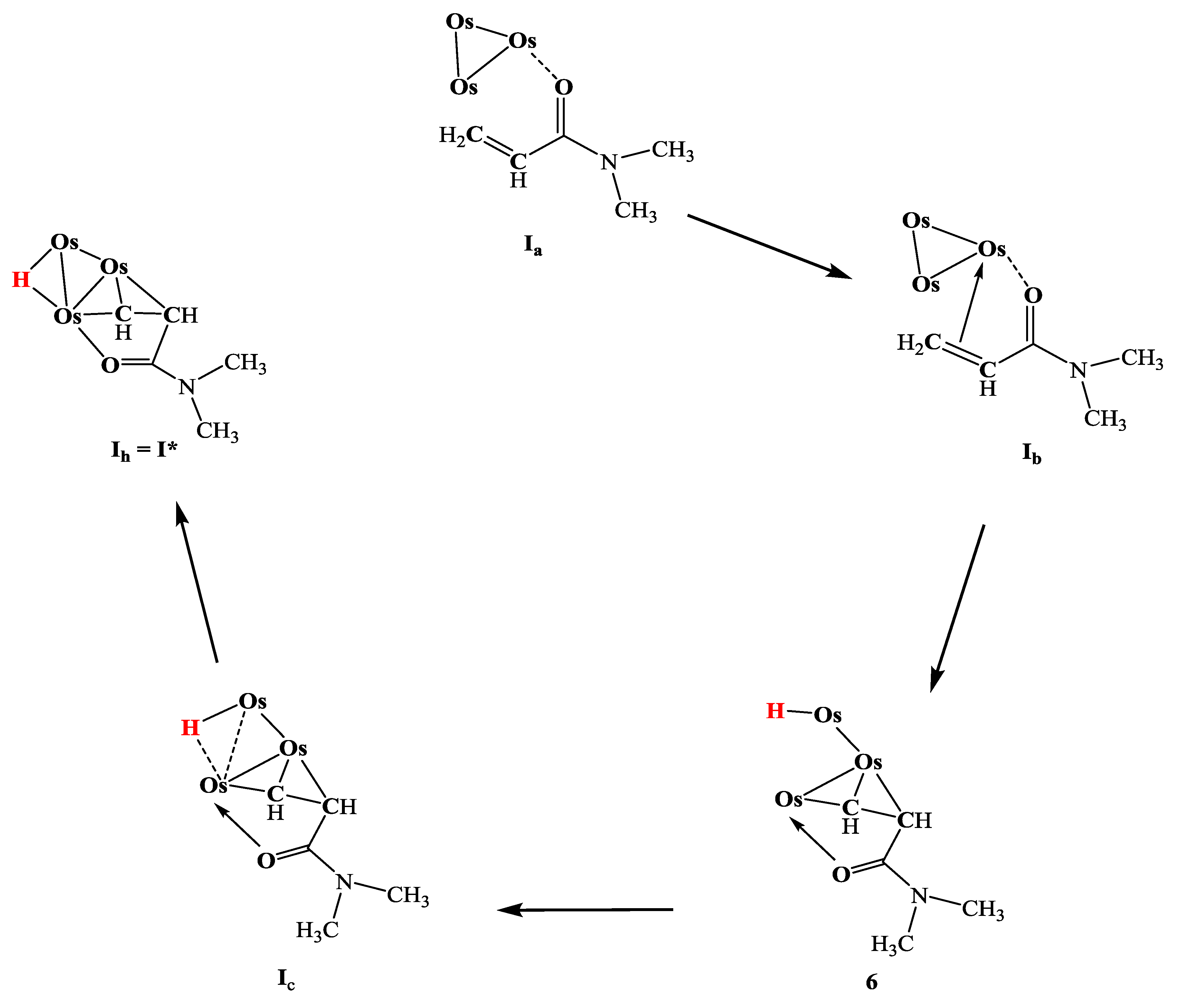

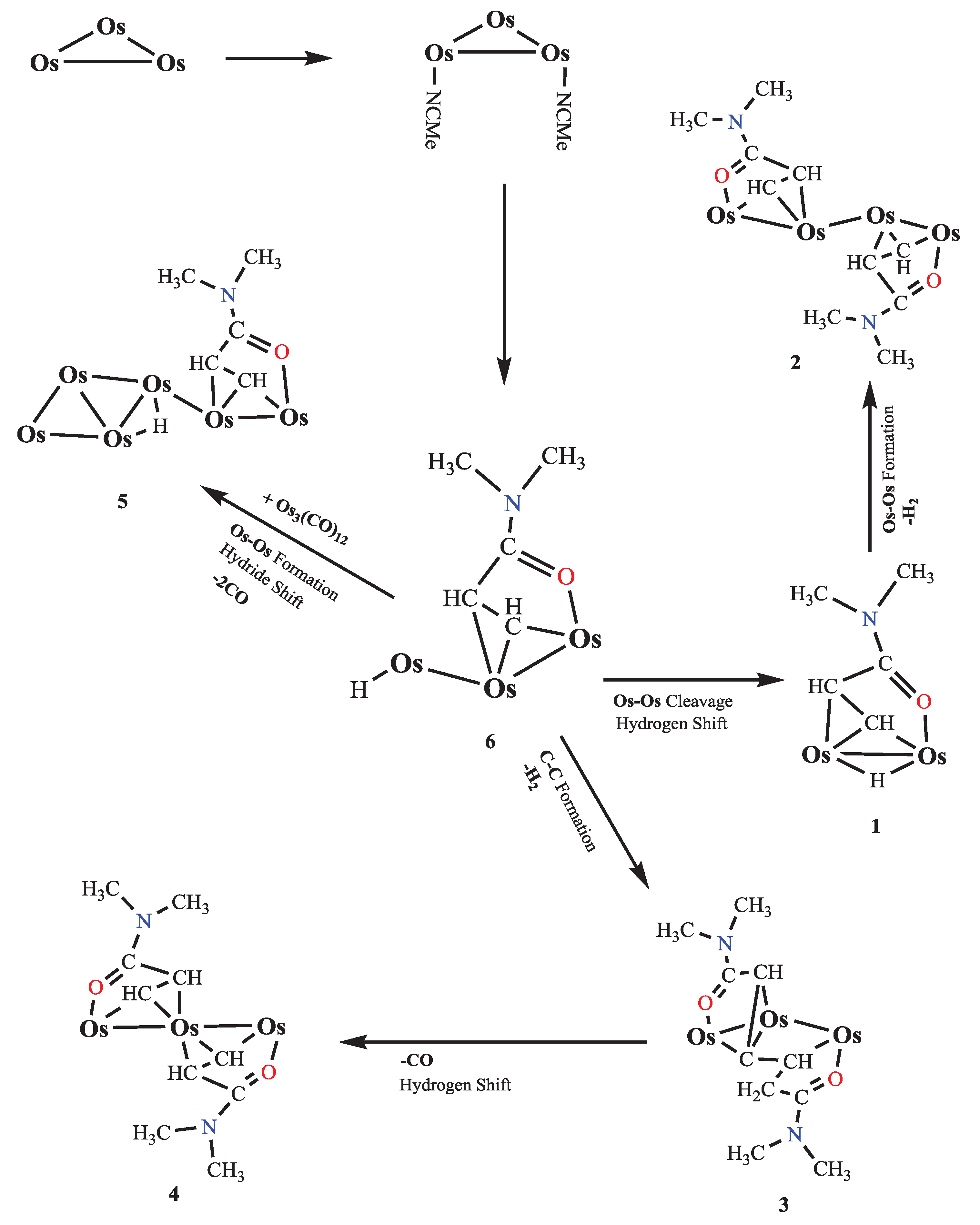

The proposed mechanism of C-H activation of

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) by the triosmium carbonyl cluster, as illustrated in

Figure 5, involves several key intermediates and transformations. Initially, the DMA molecule coordinates to the decarbonylated osmium cluster, forming intermediate

. The oxygen atom of the carbonyl group in DMA first binds to the osmium center, acting as a directing group that facilitates the activation of the

- and

-hydrogens on the vinyl group.

In the next step, the vinyl group of DMA coordinates to the osmium atom previously approached by the oxygen atom, resulting in intermediate . This coordination forms a six-membered ring (Os-O-C-C-C-H) which stabilizes the intermediate and facilitates the activation of the -hydrogen. The subsequent formation of intermediate involves the shift of the terminal hydride ligand to a bridging position, forming a more stable configuration. Finally, the reaction progresses to form the stable complex 6, where the hydride ligand remains coordinated to the osmium atoms. This step-wise transformation highlights the role of the osmium cluster in selectively activating the C-H bonds in DMA, paving the way for the efficient synthesis of complex organometallic structures. The proposed mechanism underscores the efficiency and selectivity of the symmetrical triosmium carbonyl cluster in catalyzing such intricate transformations.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism of C-H activation of DMA by triosmium carbonyl cluster and formation of intermediates.

Figure 6.

Proposed mechanism of C-H activation of DMA by triosmium carbonyl cluster and formation of intermediates.

The proposed mechanistic pathway for the C-H activation of

N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMA) by the triosmium carbonyl cluster is depicted in

Figure 7. The pathway begins with the triosmium cluster, Os

3(CO)

10(NCCH

3)

2, which is activated by the removal of acetonitrile ligands to form an electron-deficient species that can readily interact with DMA.

Initially, the electron-deficient Os3(CO)10 coordinates with DMA, leading to the formation of intermediate complex 6. The coordination involves the oxygen atom in the carbonyl group of DMA, which acts as a directing group, bringing the - and -hydrogens of the vinyl group into proximity with the osmium atoms. This facilitates the initial activation of these C-H bonds. From intermediate 6, the pathway can diverge into multiple transformations. One route involves the cleavage of an Os-Os bond and a subsequent hydrogen shift, leading to the formation of complex 1. In this transformation, the hydride ligand becomes bridging, and a new Os-Os bond is formed. This intermediate can further undergo transformations through C-C bond formation, resulting in the formation of complex 2. This step highlights the versatility of the osmium cluster in facilitating both C-H activation and C-C bond formation.

Another possible transformation from intermediate 6 involves the direct formation of complex 3 through a hydrogen shift and C-C bond formation. This pathway demonstrates the efficiency of the triosmium cluster in mediating multiple bond rearrangements, ultimately leading to the generation of complex 3. This complex can be further transformed into complex 4 by a similar mechanism, involving a CO ligand dissociation and a hydrogen shift, which stabilizes the resulting structure. Furthermore, the pathway from intermediate 6 can also lead to the formation of complex 5 through a series of transformations that include Os-Os bond formation, hydrogen shift, and the elimination of a CO ligand. This highlights the ability of the osmium cluster to undergo extensive reorganization to form stable multi-nuclear complexes.

The comprehensive mechanistic pathway outlined in

Figure 7 underscores the critical role of the triosmium carbonyl cluster in the selective activation of C-H bonds and the subsequent formation of complex organometallic structures. Each step in the proposed mechanism showcases the intricate dance of coordination, bond cleavage, and formation facilitated by the metal cluster, leading to the efficient synthesis of various CH-activated osmium complexes. This detailed mechanistic insight not only enhances our understanding of the fundamental processes governing C-H activation but also provides a robust framework for designing new catalytic systems aimed at efficient and selective synthesis of complex molecules, with potential applications in pharmaceutical drug development and other areas of chemical research.

5. Discussion

Understanding how the chemistry of our osmium (Os) clusters connects to pharmaceutical drug synthesis and concepts of “symmetrical catalysis” is critical for contextualizing this work. Below, we delineate the role of transition-metal catalysis in drug development and highlight how multi-metal (symmetrical) catalytic mechanisms – like those exhibited by Os clusters in our study – can translate to pharmaceutical applications. We cover small-molecule drugs (including anticancer, antiviral, and covalent inhibitors), larger biologics/advanced modalities, and both synthetic strategy and broader translational aspects (e.g. flow chemistry and sustainable feedstocks). Throughout, we draw parallels between the insights from our research (e.g. -C–H activation, dimerization, metal–ligand transformations in Os clusters) and established methods in drug synthesis, thereby bridging any gap between our results and pharmaceutical relevance.

5.1. Transition Metal Catalysis in Drug Development: Overview and Examples

Transition-metal catalysis is ubiquitous in modern pharmaceutical manufacturing and medicinal chemistry. Catalysts not only streamline the construction of complex small-molecule drugs by forging bonds in fewer steps, but also enable transformations with high selectivity (e.g. enantioselective catalysis) that are essential for preparing drug candidates [

62,

84,

131,

132].

Table 1 summarizes selected examples of metal-catalyzed steps in drug syntheses, illustrating the breadth of applications from cross-coupling to C–H activation and asymmetric catalysis [

133,

134,

135].

5.2. Cross-Coupling Reactions and Assembly of Drug Scaffolds

Cross-coupling reactions (e.g. Suzuki, Heck, Buchwald–Hartwig, etc.) [

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142] are foundational in building drug molecules, allowing chemists to join (often symmetrically replaceable) fragments under mild conditions. For instance, the Suzuki coupling was used on multi-kilogram scale to synthesize a Merck carbapenem antibiotic candidate , and similarly to assemble the macrocyclic anticancer agent discodermolide. The Heck coupling (Pd-catalyzed arylation of alkenes) is commonly employed to append vinyl or acrylamide moieties onto aromatic drug cores. These methods are pervasive in pharmaceutical process chemistry due to their reliability and scalability.

Notably, many covalent inhibitors (a rapidly growing class of drugs) contain an

-unsaturated amide (acrylamide) fragment that irreversibly binds a cysteine or other residue in the target protein. Approved examples include ibrutinib (BTK inhibitor) and osimertinib (EGFR inhibitor), among others. Installing such acrylamide warheads efficiently is a synthetic challenge that has been addressed by new catalytic strategies. A recent breakthrough demonstrated a one-step hydroaminocarbonylation of acetylene to produce acrylamides, enabling the synthesis of ibrutinib and osimertinib from simple anilines plus CO/H

2C=CH

2. This atom-economical Pd-catalyzed route (

Table 1) showcases how catalysis can directly forge complex drug fragments from basic feedstock molecules – a theme resonant with the multi-center acetylene transformations observed in our Os cluster chemistry (see Symmetrical Multimetal Catalysis, below).

5.3. C–H Activation and Late-Stage Functionalization

In recent years, direct C–H activation has emerged as a powerful strategy for late-stage functionalization (LSF) of drug leads[

131,

132,

133]. Instead of relying on pre-functionalized halides or handles, chemists harness catalysts (e.g. Pd, Ru, Ir) to activate C–H bonds in complex molecules and install new substituents in the final steps of a synthesis. This approach streamlines analog synthesis and can improve the retrosynthetic logic of assembling drugs. For example, directed Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H arylation has been used to diversify late intermediates of drug candidates (allowing rapid generation of analogs for SAR studies) [

134,

143,

144]. Such LSF methodologies are increasingly adopted in medicinal chemistry programs [

145], as highlighted by numerous recent reviews.

The mechanism of many C–H activation processes often involves a concerted metalation-deprotonation (CMD) [

146,

147] or related pathway, wherein a metal-base combination cleaves the C–H bond. Crucially, our osmium cluster studies demonstrate a beta C–H activation on an unsaturated amide (DMA) via a multicenter route – effectively an Os-mediated C–H activation at the

-carbon of an acrylamide. This is directly analogous to the C–H activation steps employed in refining drug molecules, albeit typically those use mononuclear catalysts. In our system, a cooperative multi-metal center abstracts a hydrogen and binds the organic fragment, forming a metal–carbon bond and a bridging hydride (Os–C and Os–H in the cluster). This mirrors how, for example, a Pd(II) catalyst might form a Pd–C (aryl) bond and a Pd–H byproduct in a CMD transition state – but here the tasks are split across two metal sites (one Os holding the carbon fragment, another Os carrying the hydride) in a symmetrical, bimetallic fashion. Such bifurcated C–H activation by multiple metals is a topic of great current interest, as it can facilitate activation of otherwise inert bonds by harnessing the strengths of each metal in a cooperative mode. Our findings provide a concrete example of this: a trinuclear Os framework that heterolytically cleaves a C–H bond across an Os–Os unit – essentially a cooperative (symmetrical) C–H activation analogous to heterobimetallic systems being explored for more efficient functionalization [

132,

134].

Importantly, late-stage C–H functionalization in pharma aims to functionalize complex molecules without disturbing existing functionality. The fact that our Os cluster can activate a specific C–H in a complex acrylamide (while tolerating functionalities like the amide carbonyl) suggests that multi-metal sites might offer selectivity advantages, perhaps via ambifacial or templated binding of a substrate. In a drug synthesis context, one could envision a bimetallic catalyst that clamps onto a substrate in a defined geometry (analogous to our cluster-substrate adduct) to activate a particular C–H bond selectively – a strategy to achieve regioselective functionalization of drug-like molecules that may be challenging with a single metal center alone.

5.4. Asymmetric and Specialized Catalysis in API Synthesis

Beyond cross-couplings and C–H functionalizations, many drugs require forming stereocenters or complex ring systems, where asymmetric catalysis is key. Osmium itself has played a historic role here: the Sharpless asymmetric dihydroxylation (AD) uses OsO

4 (with chiral ligands) to add two hydroxyls across a double bond in a stereocontrolled syn fashion [

147,

148]. This reaction – awarded the 2001 Nobel Prize – has found tremendous applications in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals [

145], as it creates vicinal diols that can be further elaborated into various functional groups. In fact, osmium tetroxide is often the reagent of choice for alkene dihydroxylation due to its high stereospecificity (delivering both oxygens to the same face of the alkene). Many active pharmaceutical ingredients incorporate diol motifs or are synthesized via diol intermediates, and Os-catalyzed dihydroxylation provides a direct route to those. For example, varenicline (Chantix

®), a smoking-cessation drug, was first manufactured by Pfizer through a route in which the key bicyclic intermediate was obtained by OsO

4 dihydroxylation of a benzonorbornadiene precursor. This catalytic dihydroxylation (performed with N-methylmorpholine N-oxide as co-oxidant to regenerate OsO

4 in situ) yielded a diol which was then transformed (via oxidative cleavage and reductive amination) into the aza-bicyclic core of varenicline. The osmium-catalyzed step was crucial to set multiple stereocenters and ring connectivity in one go, demonstrating how osmium-based catalysis can directly contribute to drug synthesis on scale. (Notably, process chemists later replaced this step with an ozonolysis route to avoid Os toxicity, but the Os-catalyzed dihydroxylation was the prototype that proved the viability of the synthetic strategy [

149,

150].)

Our study’s relevance here is twofold: (1) it underlines Os’s capability for complex transformations (beyond the well-known OsO4 oxidation) – e.g. multi-metal Os clusters performing dual additions, insertions, and C–C bond formations on unsaturated substrates; and (2) it provides structural and mechanistic insight into how symmetric (e.g. homobimetallic or multinuclear) catalysts might control such transformations. While we did not explicitly run an asymmetric catalysis in our Os cluster experiments, the symmetrical nature of the cluster (e.g. a tetrahedral Os4 core with two identical bridging acrylamide-derived ligands) hints at potential for symmetric induction. Many asymmetric catalysts are built on C2-symmetric frameworks or bimetallic complexes that enforce a symmetrical environment, and our system could be conceptually viewed in that light if adapted for catalysis. In summary, by studying stoichiometric Os cluster reactions, we lay groundwork for developing new catalytic systems (possibly cluster-derived) that could perform novel bond constructions relevant to pharmaceuticals, perhaps even in enantioselective fashion if chiral or symmetric ligands are introduced.

5.5. Symmetrical Multimetal Catalysis: Cooperative Mechanisms and Pharmaceutical Potential

One of the defining features of our Os clusters is the involvement of multiple metal centers acting in concert, which we refer to as symmetrical catalysis in the sense of cooperative, often symmetric, activation of substrates. In our results, for example, two or three osmium atoms share the task of activating a molecule of DMA (unsaturated amide): one Os–Os edge binds and cleaves the

-C–H bond, yielding a bridging

-alkenyl (from the deprotonated amide) and a bridging

-H hydride [

151]. In another transformation, we observed what appears to be the coupling of two unsaturated molecules across an Os

4 cluster, giving a complex with two identical acrylamide fragments bridging symmetrically (an Os4(CO)12 species with two

-O=C(NMe

2)CHCH ligands). Such dimerization or coupling of substrates on a cluster can be viewed as a model for a catalytic reaction where two molecules of a feedstock combine to form a new C–C bond – precisely the type of transformation one exploits in making larger drug molecules from smaller precursors [

81].

5.6. Cooperative C–H and C–C Activation by Bimetallic Systems

The cooperative mechanisms uncovered in our Os studies resonate strongly with the concept of bimetallic catalysis, which has gained traction as a way to activate strong bonds more efficiently. In bimetallic (or multimetal) systems, two metal centers can heterolytically cleave a bond by each taking a fragment – a classic example being two metals splitting a H–H or C–H bond, one taking H

−, the other H

+ (or R

− and H

+ in the case of a C–H). This is exactly what we see with the Os

3 cluster cleaving the C–H in DMA: one Os (with its neighbors) sequesters the hydride, while the adjacent Os centers bind the carbon piece, effectively performing a concerted metal–metal deprotonation [

152,

153]. Such heterolytic C–H activation across two metals has been demonstrated in modern catalyst research – for example, a Zr/Ir heterobimetallic complex was shown to activate benzene’s C–H bond by a cooperative mechanism (one metal interacting with a directing group, the other abstracting hydrogen). Similarly, various late–late heterobimetallic pairs (Ru/Rh, Rh/Au, etc.) have been studied that can cleave C–H bonds that monometallic analogues cannot, owing to a favorable division of roles between the metals.

From a pharmaceutical perspective, these cooperative activations mean that catalysts could be designed to directly functionalize molecules in new ways. For instance, if a bimetallic catalyst cleaves a C–H bond on a pharmacophore that is typically inert, one could append a new substituent at a very late stage – enabling diversification of complex drugs without pre-functionalization. This is aligned with the late-stage functionalization trend discussed above, but taking it further by involving two catalytic centers. Our Os cluster results suggest that even traditionally challenging C–H bonds (like -C–H in an acrylamide, which is vinylic in nature) can be activated when a multi-center approach is used. The implication is that symmetrical (multi-metal) catalysts might unlock transformations on drug molecules that are currently impossible or impractical with single-metal catalysts.

Beyond C–H bonds, cooperative metal systems also excel in coupling reactions that proceed through multi-center transition states. An illustrative case is the formation of a butadiene via coupling of two acetylene molecules across a Ru/Rh cluster. Here, one metal first forms a vinyl intermediate, and then the second metal helps insert another acetylene, ultimately yielding a spanning the two metals. This bears a striking parallel to what we suspect in our Os cluster: the coupling of two acrylamide-derived fragments to form a conjugated diene (with amide substituents) bridging the Os framework. In a catalytic scenario, such a transformation could afford a 1,4-dicarbonyl compound or a dienamide, which could be cyclized or elaborated into heterocycles found in medicinal chemistry. Indeed, many drug scaffolds contain conjugated dienes or enones (e.g. polyene macrolides, vitamin D analogues, etc.), and forming those via direct dimerization of simpler alkynes or alkenes is attractive. Our observation of a butadiene-like ligand on Os substantiates the feasibility of that approach: a symmetric catalyst might hold two molecules in just the right orientation to couple them – something a single metal center might struggle to do as selectively. Adams et al. previously demonstrated that metal carbonyl clusters can oxidatively dimerize activated olefins: e.g. a Ru5CO cluster added two methyl acrylates to form a new C–C bond, and a Re2 complex coupled vinyl acetate in a similar fashion. Those precedents, together with our results, reinforce that multimetallic platforms can promote symmetric bond formations (dimerizations, coupling of identical units) relevant to constructing symmetrical or complex intermediates for drugs.

5.7. Symmetry, Catalyst Design, and Selectivity

When we refer to “symmetrical catalysis” in the context of our title and work, we mean catalysis that involves either symmetric catalyst structures or symmetric reaction pathways (often both). Multinuclear complexes like our Os clusters often possess elements of symmetry (e.g. the Os

4 cluster with two identical ligands is

-symmetric). In catalysis, symmetry can be advantageous: a symmetric catalyst can present two identical binding pockets or reactive sites, enabling bifunctional activation of two identical groups. This principle is utilized, for example, in some dual-activation catalysts where each of two metal centers activates a different substrate in a complementary way (often called dual catalysis) [

81,

150]. In pharmaceutical synthesis, a symmetric bifunctional catalyst might, for instance, activate a protic nucleophile and an electrophile simultaneously at two sites to forge a bond – leading to higher rates or novel selectivities.

Our Os clusters provide a model for designing such catalysts. The cooperative interactions we observe (one Os–Os pair acting like a single bifunctional active site) suggest that if we tether two metal centers in a defined symmetric geometry, we might reproduce this effect catalytically. For example, envision an Os–(bridging ligand)–Os complex engineered to mimic our cluster’s transition state: it could abstract a proton with one Os while binding the substrate to the other, delivering a functionalized product and regenerating the Os–Os unit. This is analogous to some pincer-ligand complexes where a metal and a basic site on the ligand cooperatively cleave H–X bonds (metal–ligand bifunctional catalysis), but in our case the cooperation is metal–metal . The symmetry ensures both metals are held at the correct distance and orientation for this synergy. The result can be greater control over reaction pathway – potentially minimizing side reactions. Indeed, one reason industry values catalysts is selectivity: fewer byproducts means easier purification of drugs. Symmetric multi-metal catalysts, by orchestrating concerted transformations, could suppress free-radical pathways or random over-reactions that might occur if reagents aren’t held in place.

5.8. Flow Chemistry, Green Processes, and Raw Material Efficiency

On an industrial scale, efficiency and sustainability of drug synthesis are paramount. Catalysis (especially by robust metal complexes) aligns with green chemistry by enabling lower energy usage and atom economy. An emerging paradigm is continuous flow manufacturing of pharmaceuticals, where reactions are run in flow reactors for better heat/mass transfer and automation. Catalysts that are stable and active over long periods are crucial for flow [

154,

155,

156]. Multi-metal catalysts, by virtue of potentially higher stability (a cluster can distribute reactive events over several centers, possibly reducing strain on any single metal), could be good candidates for such continuous processes. For example, a supported bimetallic catalyst might carry out thousands of turnovers of a C–H activation or coupling in flow without degrading, thus improving the throughput and safety (no need to handle large batches of reactive intermediates). While our work is at the fundamental stage, the knowledge gained about Os cluster stability and reactivity under various conditions could inform how to design catalysts for continuous drug synthesis.

Another translational aspect is the use of raw materials: Catalysis allows use of simpler, more abundant starting materials (petrochemicals, biosourced molecules), reducing reliance on pre-functionalized reagents. We showed an Os cluster inserting CO (a cheap C1 source) and coupling unsaturated fragments, hinting that a catalyst could directly take

units (alkynes or alkenes) plus CO to build more complex scaffolds [

157,

158,

159,

160]. Indeed, the earlier example of Pd-catalyzed acetylene hydroaminocarbonylation to make drug acrylamides beautifully illustrates this philosophy: use gaseous acetylene and CO (commodity chemicals) to construct an advanced pharmaceutical intermediate in one pot. Such transformations improve the atom economy and supply chain simplicity for drug production – fewer steps from oil or biomass to medicine. In our case, demonstrating that Os clusters can effect CO insertion into an organic fragment suggests future catalysts might incorporate this step into a one-pot sequence (e.g. combine alkene + CO + another molecule to form a carboxylate or ketone in situ, relevant to making drug building blocks).

Finally, biomolecule conjugation and modification often rely on metal catalysis as well, which bridges to advanced biologic therapies. For instance, attaching a cytotoxic drug to an antibody to make an ADC (antibody–drug conjugate) frequently employs click chemistry – the Cu(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) – to quickly and selectively form triazole linkages. This bio-orthogonal reaction is inherently catalytic (Cu is regenerated) and takes place under mild conditions compatible with proteins. While our Os clusters are far from biological conditions, the broader point is that metal catalysts enable modification of large biomolecules in ways that classical chemistry cannot. There is ongoing research into metalloprotein and peptide functionalization – for example, using Pd or Ir complexes to catalyze late-stage diversifications on peptides, or Ru-based catalysts to install fluorescent tags on proteins. The ethos is similar to our approach with small molecules: harness unique transition-metal reactivity to achieve transformations on complex frameworks (whether a small drug or a big biomolecule) in a single step. In the future, it’s not inconceivable that multinuclear complexes could be designed to bind and modify proteins at two sites symmetrically, or to crosslink biomolecules in novel ways, expanding the toolkit for biologics development.

5.9. Conclusion: Bridging Cluster Chemistry to Drug Synthesis

In summary, although our study focuses on osmium cluster compounds in a fundamental inorganic chemistry context, its relevance to pharmaceutical catalysis is significant. We have demonstrated symmetrical, cooperative mechanisms – such as multi-metal C–H activation and C–C coupling – that closely parallel key steps in catalytic drug synthesis (C–H functionalization, cross-coupling, etc.). Osmium-based catalytic reactions (e.g. dihydroxylations) already have a track record in industry, and the unique reactions of Os clusters we report (e.g.

-C–H activation of acrylamides, dual insertion of unsaturated esters) represent fundamental reactivity that could be harnessed in future catalytic processes. By elucidating how an Os

3 or Os

4 cluster activates and transforms organic substrates, we provide insight into designing new catalysts – possibly bimetallic or cluster-derived – for efficient construction of pharmaceutical molecules. This could mean more direct routes to drugs (fewer steps, symmetric assembly of fragments), access to novel chemical space (through previously unknown transformations), and improved selectivity (via concerted multi-metal control of reaction pathways). In effect, our work helps bridge the gap between organometallic cluster chemistry and real-world drug synthesis: the mechanistic principles learned from the former can inspire the next generation of catalytic methods to streamline the production of medicines. By clarifying this connection, we address the reviewer’s concern – our results indeed align with the concepts of symmetrical catalysis and pharmaceutical synthesis, as the Os cluster reactivity showcases the very multi-center catalytic strategies that are poised to make drug development more efficient and innovative [

161,

162].

6. Conclusion

This work establishes a coherent stoichiometric platform for cooperative, symmetry-enabled transformations of unsaturated amides and esters at multinuclear osmium carbonyl clusters. Starting from Os3(CO)10(NCCH3)2, we isolated and structurally characterized a family of eight CH-activated products spanning di-, tri-, tetra-, penta- and hexa-osmium cores (1–8). These include (i) -C–H activation of an acrylamide to give bridging acryloyl ligation with terminal or bridging hydrides (1, 5, 6), (ii) assembly of multi-alkenyl architectures across Os–Os edges (2, 4, 7), and (iii) end-to-end dimerization of N,N-dimethylacrylamide bound within a triosmium framework (3), as well as the ester analogue from methyl acrylate (8). A unifying mechanistic picture emerges in which the key intermediate 6 undergoes concerted, cooperative bond reorganization—Os–Os cleavage/formation, hydride migration, and CO loss or insertion—to access the observed product manifold (Schemes and ORTEPs, Secs. 3–5).

What is learned about symmetry and cooperation. The clusters operate as bifunctional active sites in which two (or more) metal centers share the work of C–H activation and C–C construction. In practical terms, this means an Os–Os unit can heterolytically cleave a -C–H bond while simultaneously stabilizing the nascent Os–C and Os–H fragments. Across the series, we observe that symmetric binding modes (e.g., -acryloyl and -acryloyl motifs) template the geometry for coupling two identical unsaturated partners, rationalizing why dimerization pathways become accessible under mild conditions. Solvent gating (heptane vs. CH2Cl2 vs. hexane) reproducibly steers product distribution, underscoring that cluster symmetry, electron count, and medium cooperatively control selectivity (Sec. 3.2.4).

Relevance to pharmaceutical synthesis. Although no catalytic turnovers are claimed here, the reactions we delineate map directly onto bond constructions prized in pharmaceutical settings:

Late-stage functionalization of amide scaffolds. Site-specific -C–H activation on an acrylamide bound to a multinuclear site suggests a route to regiocontrolled installation of handles (C–C, C–O, C–N) on drug-like amides without prefunctionalization.

Symmetric C–C coupling of feedstocks. The dimerization and multi-bridging motifs (2, 3, 4, 7) are prototypes for coupling identical / units into conjugated or 1,4-dicarbonyl-like frameworks that frequently seed heterocycles and pharmacophores.

Integration of CO as a one-carbon synthon. Readily observed CO migration/expulsion across the series highlights that carbonylation steps can be embedded within a single multinuclear coordination sphere—an attractive blueprint for compacting step counts in API routes.

Process alignment. The tolerance of amide and ester functions, together with solvent-dependent selectivity, speaks to tunability crucial for flow chemistry and green metrics (atom economy, minimized protecting groups) emphasized in industrial manufacture.

Limitations and scope. The present study is intentionally foundational. All bond-making events are demonstrated stoichiometrically on isolable clusters; kinetics, turnover frequencies, and substrate generality are not yet established. The role of cluster nuclearity (di- vs. tri- vs. higher) in governing barrier heights is inferred from product connectivity rather than quantified. Finally, while osmium showcases rich cooperative reactivity and crystallographic tractability, translation to more abundant congeners remains to be tested.

Future directions. Building on these insights, we envisage four practical thrusts that bridge cluster chemistry to deployable pharma synthesis:

From stoichiometry to catalysis. Design turnover-capable bimetal/trimetal catalysts that mimic 6 as a resting state and cycle through the -C–H activation/C–C coupling motifs seen in 1–5,7–8. Metrics: TON/TOF, mass balance, and robustness screens in the presence of amide/ester functionality.

Scope on drug-like substrates. Probe directed and undirected -C–H activation on acrylamide/enoamide fragments embedded in representative small-molecule intermediates; map substituent, electronics, and steric effects that control regioselectivity.

Mechanistic quantification. Combine variable-temperature NMR (hydride exchange/EXSY), isotopic labeling (KIE for -C–H cleavage), and computation to distinguish CMD-like versus stepwise pathways across Os–Os edges; correlate with electron counts and symmetry elements observed crystallographically.

Translational engineering. (i) Port the cooperative blueprint to congeners (Ru, Rh) and supported/heterogenized analogues for improved practicality; (ii) evaluate continuous-flow operation where solvent choice already modulates selectivity; (iii) embed carbonylation events to deliver carboxyl/ketone motifs in situ from CO, minimizing step count.