1. Introduction

In the civilian sector, the traditional method involves using active sonar to locate aquatic targets. Due to the limited scanning range and lower power of the active sonar on ships, it is difficult to continuously track targets and conduct extensive monitoring[

1]. However, a high-efficiency underwater acoustic (UA) target recognition system, combined with passive distributed sonar, can provide continuous and effective support for marine ecological monitoring, vessel traffic management, and seabed geological exploration. This not only promotes the rational use of marine resources but also reduces the impact of human interventions on the marine environment, advancing the sustainable development of the marine economy. For example, the UA target recognition system can continuously track the migration routes of large marine organisms like whales, monitor changes in water quality, assisting marine conservation organizations and researchers to take timely protective measures[

2,

20,

21,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31].

Currently, there remain significant challenges in developing UA signal classification devices. With the advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies, the application of AI in the field of UA target classification is increasingly gaining attention[

12,

13,

14,

15]. Recent literature has showcased several innovative approaches based on deep learning and machine learning. Meanwhile, Wang et al. [

3] proposed a weighted-MUSIC direct localization method for Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks (UASN) based on a multi-cluster data model. Yu et al. [

4] employed Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks for modulation pattern recognition, utilizing the instantaneous features of UA signals for effective classification of modulation modes. This technique leverages the temporal dynamics and memory capabilities of LSTM to manage the complex variability in acoustic signals over time[

16,

17]. Wang et al. [

5] proposed a hybrid time series network structure that extracts hidden modulation classification features and accommodates variable-length signals to meet the fixed-length input requirements of conventional neural networks (CNN), enhancing the model’s flexibility and adaptability to diverse underwater signal datasets[

18,

19,

20,

21]. Wang et al. [

6] utilized Deep Neural Networks (DNN) to learn fused features of GFCC and Modified Empirical Mode Decomposition (MEMD), incorporating a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) layer to enhance the efficiency of the analysis[

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Over the past decade, various machine learning (ML) classification algorithms have been extensively applied to enhance the accuracy of classification tasks.

Zhang et al. [

7] examined 19 traditional classifiers, including Decision Trees (DT), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and k-nearest neighbors (KNN). They used Gammatone Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (GFCC) to model up to 16 UA targets and provided a comparative analysis of accuracy with other feature descriptors such as Mel-Frequency Cepstrum Coefficients, Autoregression, and Zero-Crossing While GFCC outperformed other features, its application was time-consuming. These studies highlight a trend towards integrating sophisticated computational models with traditional signal processing to improve the classification and analysis of UA signals, marking a pivotal shift towards more adaptive, accurate, and robust systems for UA target classification [

8].

This paper proposed a high-energy-efficiency underwater acoustic target recognition system based on sparse convolutional neural network circuits. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

(1) A DenseNet convolutional neural network model was employed as the framework for an underwater acoustic target recognition system. To address issues related to the complexity of the network, fine-grained pruning was implemented to achieve sparsity.

(2) Based on the sparse convolutional neural network structure, an underwater acoustic target recognition accelerator was designed. The accelerator's performance was experimentally validated on FPGA.

(3) The performance and power consumption of the underwater acoustic target recognition system were enhanced by optimizing the physical implementation of the circuit. The chip's power consumption and area were evaluated using Design Compiler synthesis, and comparisons were made with the performance of software simulations and FPGA deployments.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section II details the proposed method for UA target recognition. Section III discusses the design of the accelerator circuit. Section IV describes the simulation experiments of the underwater acoustic target recognition system and its verification on FPGA. Finally, conclusion is achieved in Section V.

2. Proposed Method

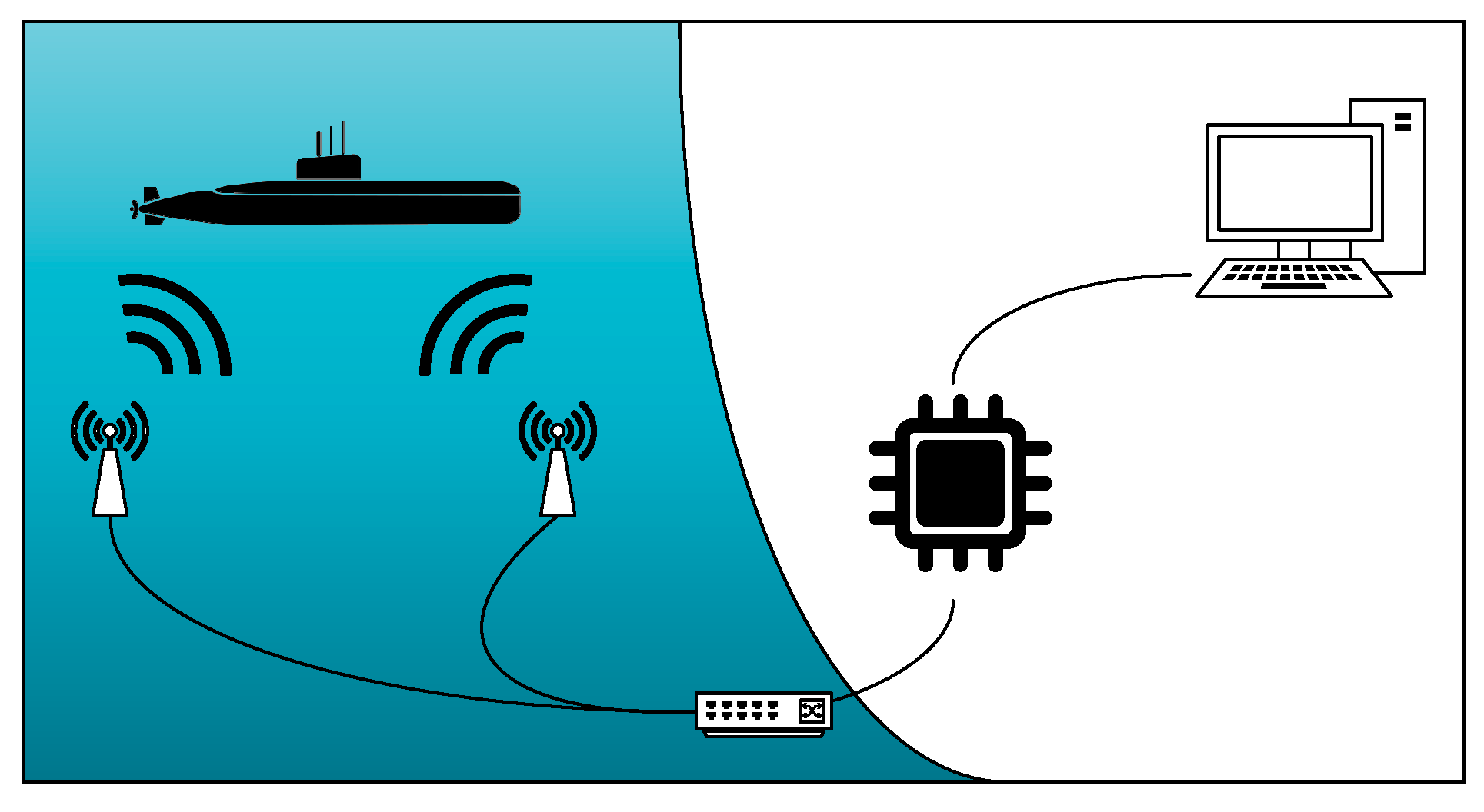

The underwater acoustic target recognition system proposed in this paper is shown in

Figure 1. This system captures the underwater acoustic target signals using passive sonar and processes these signals through a convolutional neural network chip, achieving high energy efficiency and precision in target recognition[

12,

13,

14,

15].

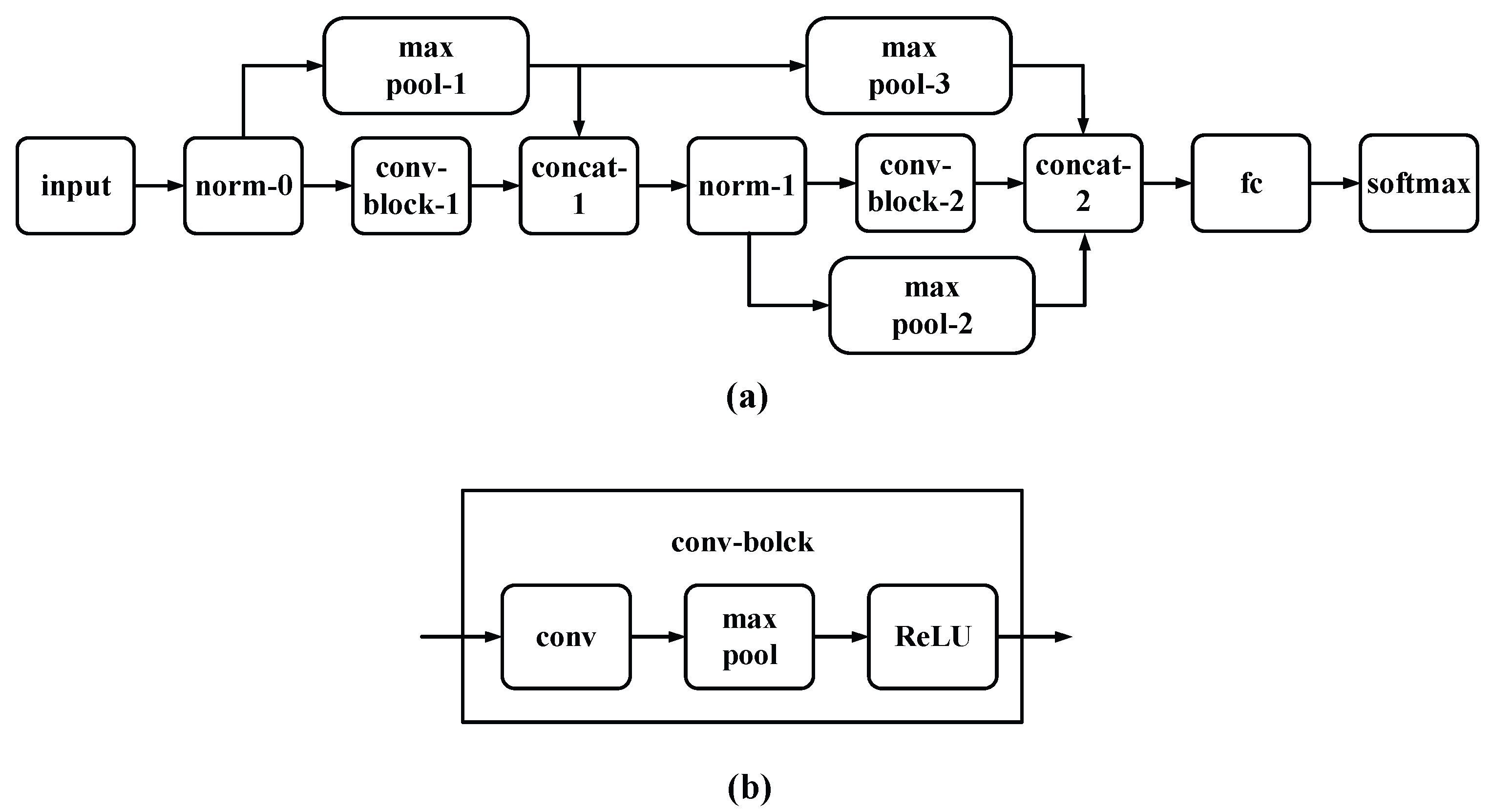

Inspired by the network originally introduced for image classification [

9], the UA recognition system is adapted with a dense architecture, as presented in

Figure 2(a), to accommodate the input of 1-D time-series data, such as acoustic signals[

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. For data preprocessing, the continuous acoustic signal in the time domain is segmented into multiple frames, each comprising 1 × 4096 samples.

At the beginning of the network, the input layer is immediately followed by a batch normalization layer. This layer facilitates the optimization process during training by normalizing the values of its input,

, based on the mean

and variance

computed over a minibatch for each input channel. The normalization adjusts the inputs to have zero mean and unit variance, which can help in accelerating the convergence of the training.

where

serves as a small constant added to the variance to ensure numerical stability and prevent division by zero during the normalization process.

Regarding the network architecture, UA recognition system is composed by sequentially stacking several convolutional blocks, each denoted as a "conv-block." As illustrated in

Figure 2(b), each conv-block comprises convolutional, max-pooling, and activation layers. Specifically, the convolutional layer employs 3 two-dimensional (2-D) kernels, each of size 5 × 5. The convolution operation can be mathematically represented by the equation below, where

denotes the input and

represents the convolution coefficients:

Here, indicates the convolution operation, and de-notes the bias term added to the convolution result.

Subsequently, spatial pooling is employed to downsample the output feature map by eliminating weaker features. Specifically, the max-pooling layer is configured with a pool size of 2×2. It significantly decreasing the computational burden on subsequent layers.

Following the max-pooling layer in the network architecture is the activation layer, which plays a pivotal role in CNN. Activation functions like the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) are commonly utilized in many renowned CNN architectures due to their ability to facilitate rapid convergence. However, ReLU presents a drawback as it leads to information loss when the input is less than zero. In contrast, the Exponential Linear Unit (eLU) aims to address this issue and potentially enhance network training effectiveness. The eLU function performs an identity operation on positive inputs, while applying an exponential non-linear transformation to negative inputs. Mathematically, the eLU function can be expressed as follows:

From an overall architecture perspective, UA target classification system comprises a backbone stream and several skip connections. This structure involves deep feature extraction through stacking two convolutional blocks; simultaneously, carefully engineered skip connections help to further enhance the gradient flow throughout the network. Compared to some traditional CNNs, skip connections optimize the use of feature maps extracted in previous convolutional blocks and help protect the network from the vanishing gradient problem. In skip connections, three widely used mechanisms include addition, lateral concatenation, and depth concatenation. In the addition mechanism, as explored in depth in ResNet [

10], different feature maps of the same dimensions are combined through element-wise addition. In lateral concatenation, multiple feature maps are connected along either horizontal or vertical dimensions. Unlike lateral concatenation, which expands the output space dimensions, depth concatenation merges input feature maps along the depth dimension. In terms of computational complexity, depth concatenation is more suitable for deployment in this study due to its adaptability. Since skip connections are built on feature representations of different scales, the max pooling layer is used to resize the spatial dimensions of previous feature maps to correctly fit the volume size of the backbone stream. In this setup, the output from each convolutional block can be represented by concatenation as follows[

11]:

A fully connected layer is configured with 11 neurons, corresponding to the classification of 11 target categories. Following the fully connected layer, a softmax layer and a classification layer are placed, where the softmax function is designed to produce decimal probabilities in alignment with the UA target categories. Assuming the output feature vector from the fully connected layer is denoted by

, the output of the softmax function can be expressed as:

Finally, the UA recognition system predicts the target of the incoming UA signal , identifying the category with the highest probability.

3. UA Target Recognition Accelerator

To achieve model compression and improve energy efficiency without significantly sacrificing accuracy, we employed magnitude-based fine-grained pruning on the DenseNet convolutional neural network model. This method aims to identify and remove the connections with the smallest contribution to the final prediction.

Specifically, our pruning process is an iterative loop. First, we evaluate the pre-trained, full-connected network. We then sort all weights in the network and set a global threshold based on a predetermined pruning ratio. All weight connections below this threshold are permanently removed, with their values set to zero.

After pruning, the network undergoes fine-tuning to retrain the remaining non-zero weights, thereby compensating for any performance degradation caused by the removed connections. This "pruning-and-fine-tuning" cycle is repeated multiple times until the preset pruning ratio is achieved. Through this iterative approach, we are able to progressively remove redundant connections while retaining the model’s core information to ensure the pruned sparse model still maintains high recognition accuracy.

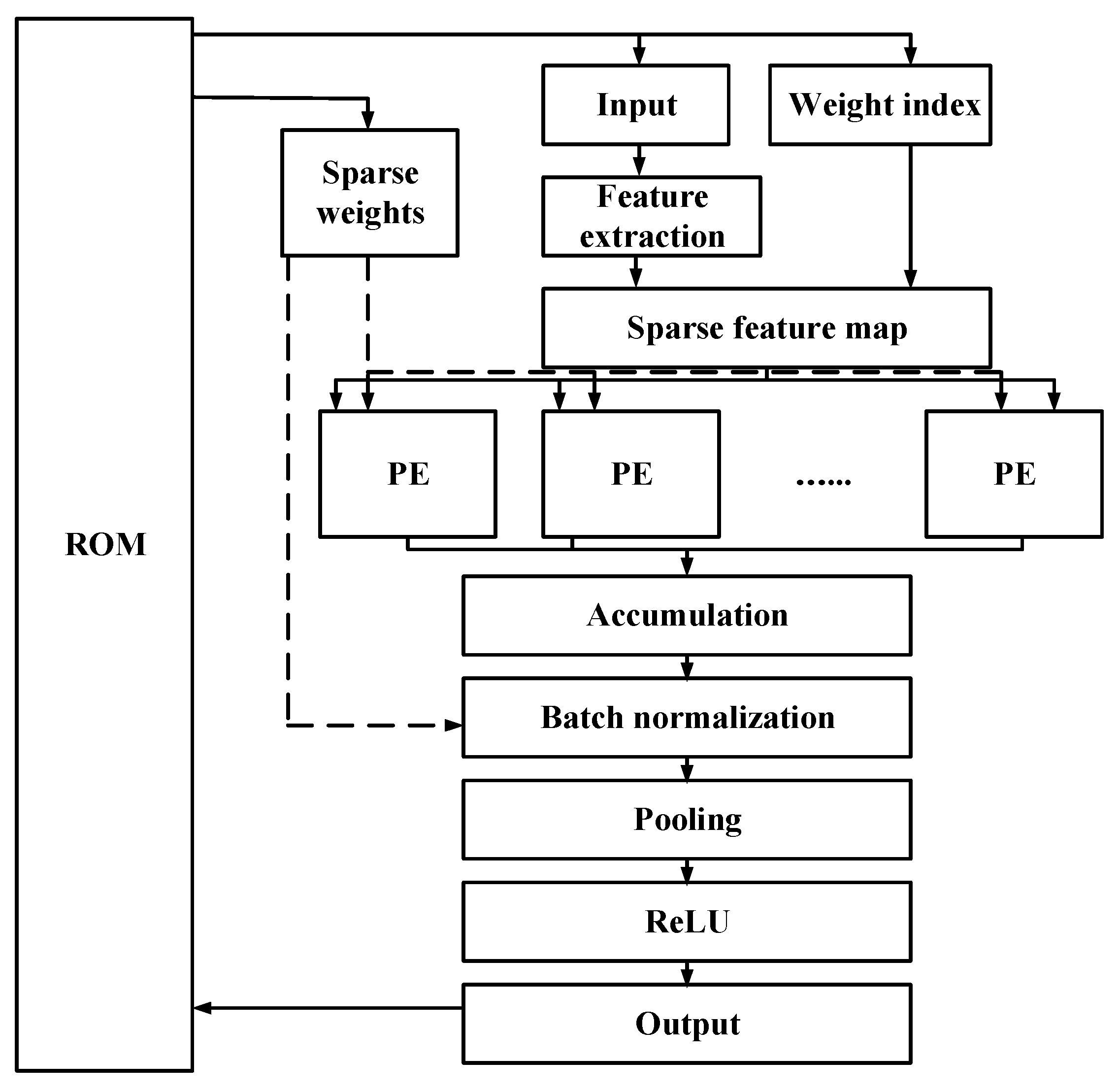

The overall architecture of the circuit is divided into two main parts: storage and computation. The storage section encompasses the caches for sparse weights, input, sparse weight indices, and output. In the computational module, the structure includes several components such as the feature extraction module, sparse feature map computation module, convolutional computing unit (Processing Element), accumulation module, normalization layer, pooling layer, and activation functions.

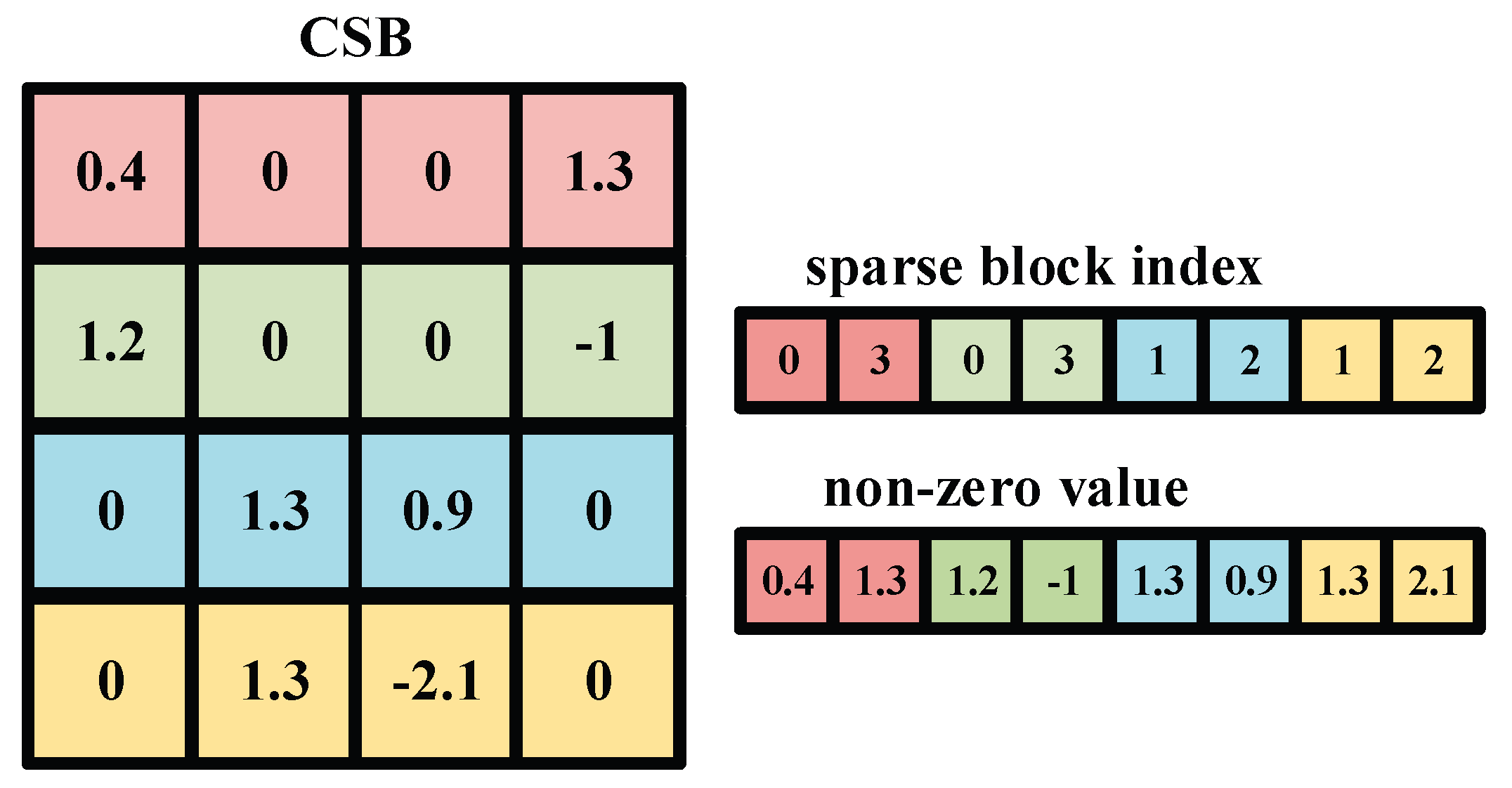

The Compressed Sparse Banks (CSB) format is a data structure utilized for the efficient storage of sparse matrices [

11]. CSB operates by dividing a sparse matrix into several blocks, referred to as "sparse banks," and then compressing each block, thereby facilitating effective storage of the entire matrix. The primary concept behind CSB is to partition the sparse matrix into blocks and compress each for storage. Specifically, CSB divides the matrix into several blocks of equal size and compresses each, including the values and the indices of the sparse blocks. This method significantly reduces memory usage, making it particularly well-suited for the storage and processing of large-scale sparse matrices.

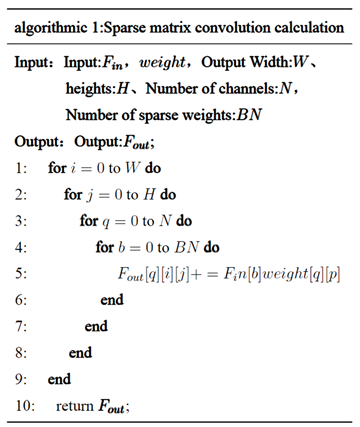

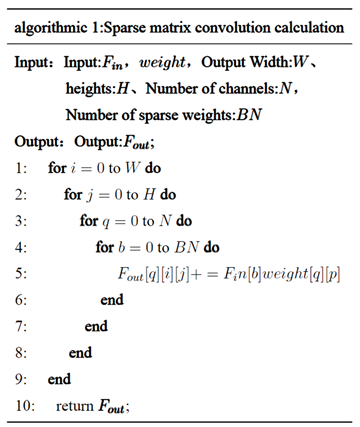

Therefore, in the hardware design of UA target recognition systems, CSB compression is employed to store the pruned sparse weights. The algorithm for the entire sparse matrix convolution computation process is as Algorithmic 1.

In this study, the sparse matrix convolution module takes as input the sparse weights and the sparsely indexed input feature maps processed by the weight index module. The sparse weight matrices stored using the CSB format are represented by two independent arrays. One array stores the values of the non-zero elements, allowing for the direct retrieval and computation of non-zero weight elements during convolution without the need for separate decoding. The other array, containing the indices of the sparse blocks. The parallel computation structure of the sparse matrix convolution unit utilizes preprocessed sparse input feature maps and sparse weights. These inputs are fed into multiple computing units where they undergo dot product operations in conjunction with weight parameters. The results of these operations are subsequently directed to an accumulator to aggregate the dot product outcomes, yielding the convolution output for a single channel. This architecture effectively leverages hardware resources and increases the degree of parallel processing.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

During software experimental testing, we utilized Matlab to process audio files from the ShipsEar dataset. We trimmed the blank portions from the original audio signals. Each signal was then segmented into 1000 continuous observational frames, converted into time series format. Each sample was defined to have a one-dimensional frame containing 4096 sample points. Furthermore, to investigate the performance of the proposed underwater acoustic target recognition system under various noise conditions, we randomly introduced Gaussian noise to the audio files. This adjustment created a range of signal-to-noise ratios (SNR), defined as the ratio of the average power of the received signal to the noise power, from -20 dB to 10 dB with a step size of 2 dB. The dataset was randomly divided into 70% for training and 30% for testing. Features of the transformed signals were then extracted, with each frame sample being resized to 64×64, containing 4096 sample points in total. In this section of the experiment, the neural network model was trained over 40 epochs with a minibatch size of 64 and an initial learning rate of 0.001.

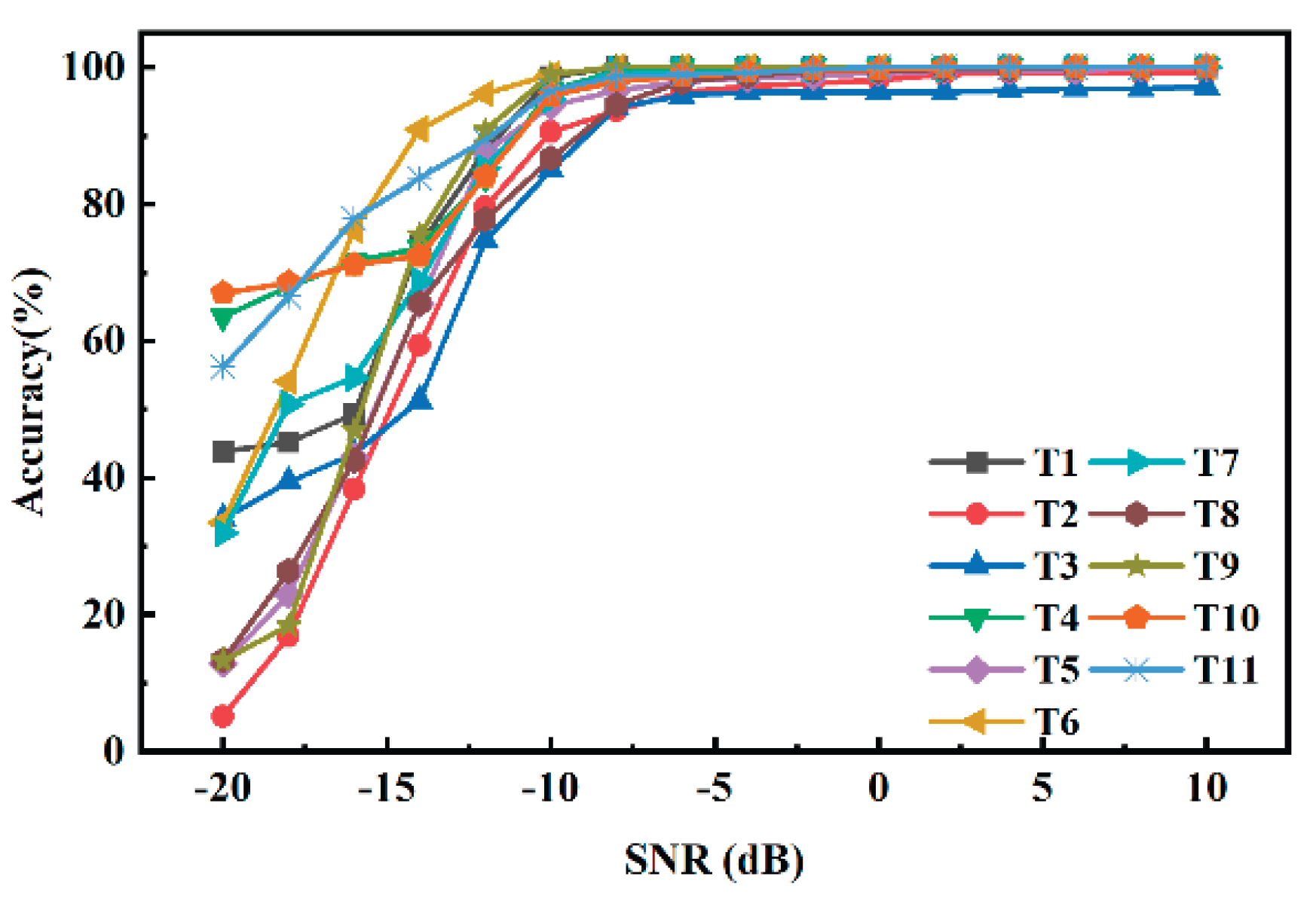

Figure 4 shows the detailed demonstration of the DenseNet convolutional neural network’s performance in recognizing 11 types of underwater acoustic targets. Under conditions of 0 dB SNR, the overall accuracy reached 98.73%. The accuracies vary among different targets due to the distinct radiation characteristics of the sounds they emit. This variation indicates that different targets exhibit unique feature representations in underwater acoustic signals. Accuracy generally improves with increasing SNR. At low SNRs, specifically from -20 dB to -10 dB, the model’s accuracy is significantly reduced. As the SNR exceeds 0 dB, the model’s accuracy stabilizes and remains high, indicating effective signal recognition. This improvement is attributed to reduced noise interference at higher SNRs, enabling the network to more easily distinguish between targets and noise, thus significantly enhancing accuracy compared to lower SNRs.

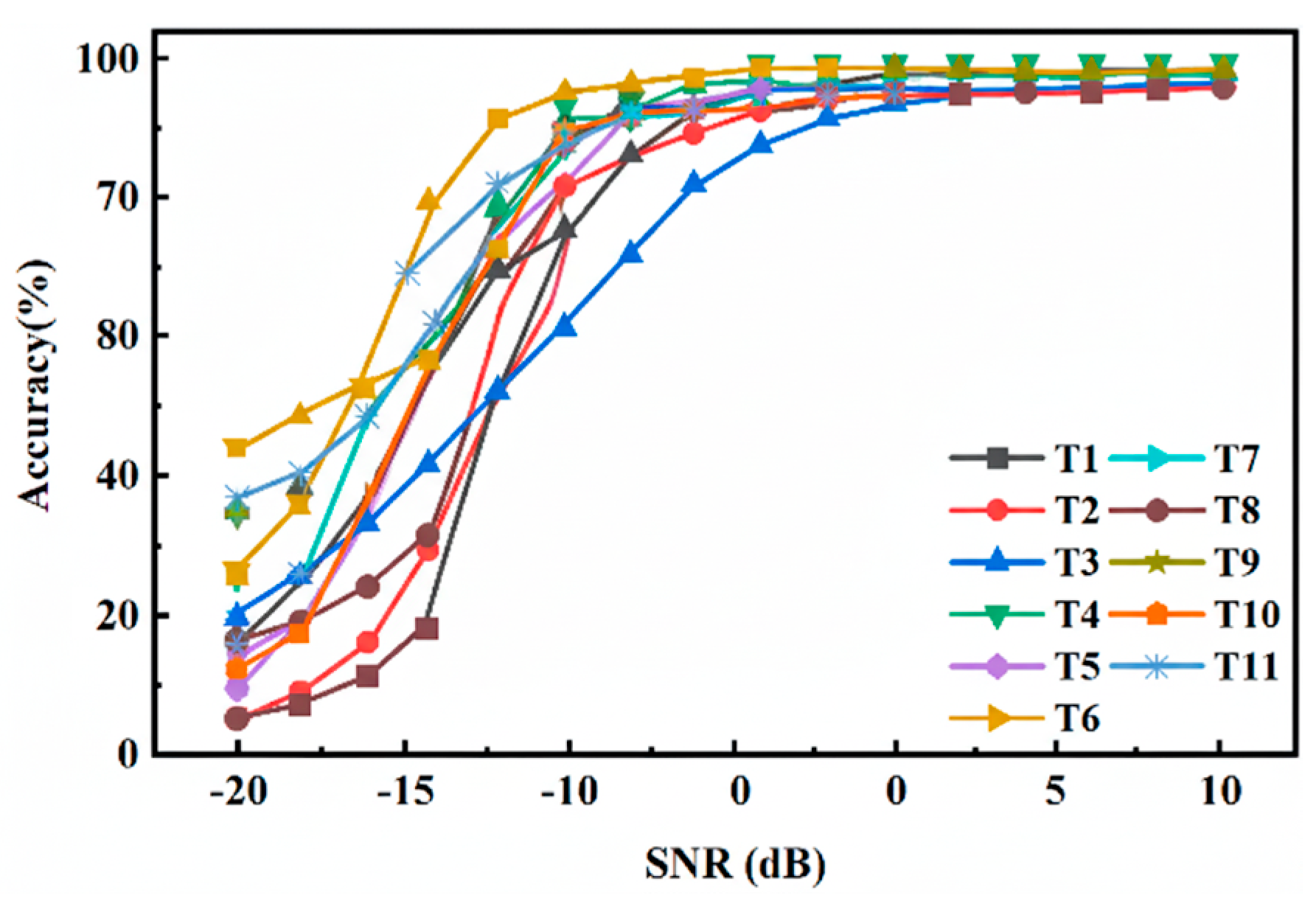

Figure 5 shows the results of the underwater acoustic target recognition using a DenseNet convolutional neural network, after implementing 50% fine-grained pruning. This pruning led to a decrease in recognition accuracy, with an overall accuracy of 96.11%. The decline in accuracy was more pronounced under conditions of low SNR. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fundamental trade-off between model sparsity and robustness in noisy environments. While pruning effectively removes redundant connections for compression, some of these connections, which may be deemed insignificant in high SNR conditions, play a crucial role in extracting subtle, complementary features from noisy signals. In low SNR environments, where the primary signal is heavily masked by noise, the model's ability to identify and utilize these weak features is critical for maintaining high performance. By removing these connections, the pruned model loses a degree of its built-in robustness, making it more susceptible to noise and leading to a more pronounced drop in accuracy. This decrease can be attributed to the reduction in network parameters due to pruning, which makes the network more sensitive to noise.

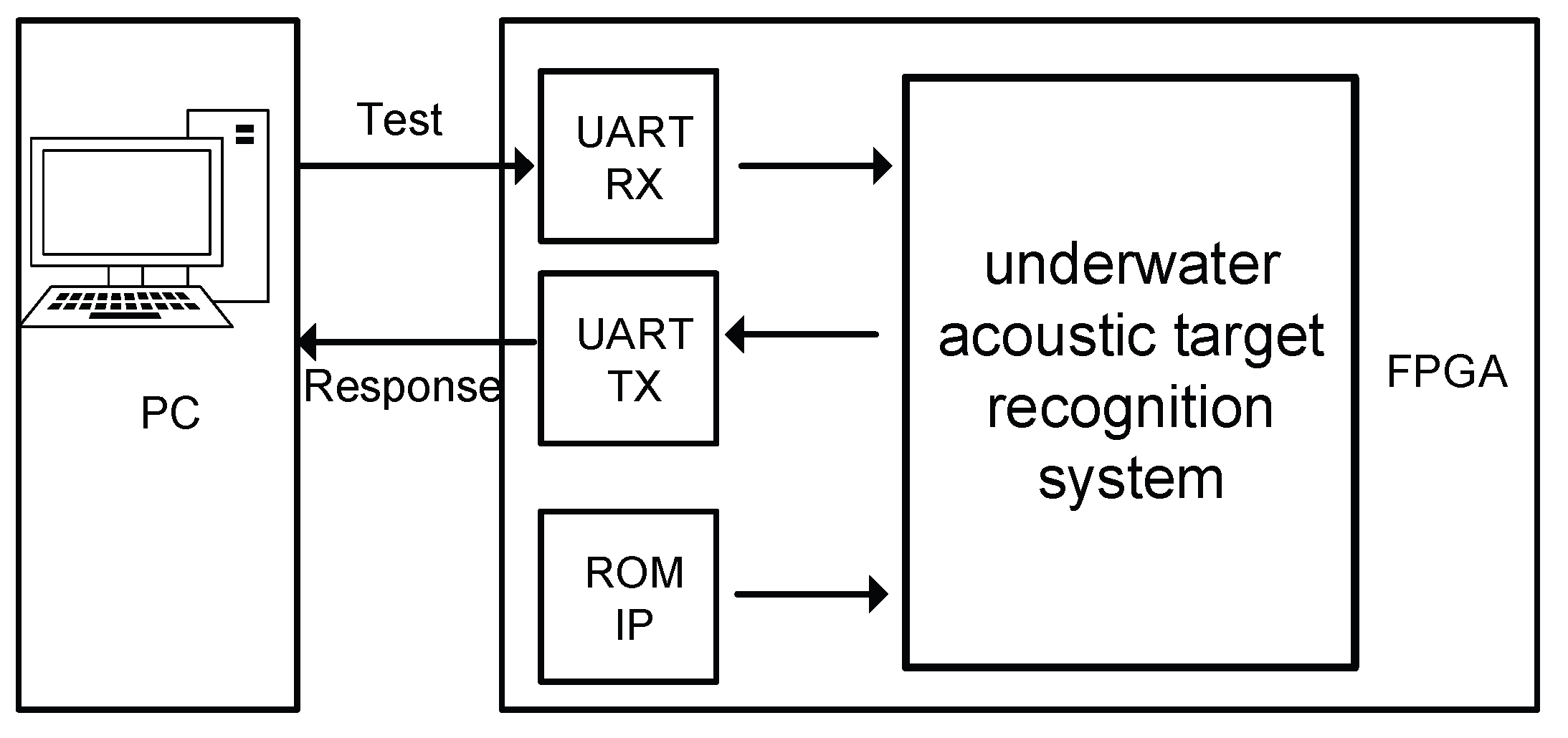

Figure 6 shows the overall hardware testing system design for the accelerator based on the DenseNet CNN, for UA target recognition. Initially, the network processes a single UA target signal under 0 dB SNR conditions. In this test, data are input into the FPGA circuit through the UART and the target recognition results are output through the decision signal. The test results, at a 10MHz clock, indicate that recognizing a single UA target requires 13.3 ns, with a power consumption of 189.02 mW. Subsequently, a more intensive test was performed by continuously feeding 1000 randomly selected UA target signals under 0 dB SNR conditions into the circuit. After analyzing all output results, the circuit demonstrated an accuracy of 95% in the recognition task of 1000 UA target signals at 0 dB SNR. It shows the effectiveness and robustness of the circuit on this UA target recognition task and dataset.

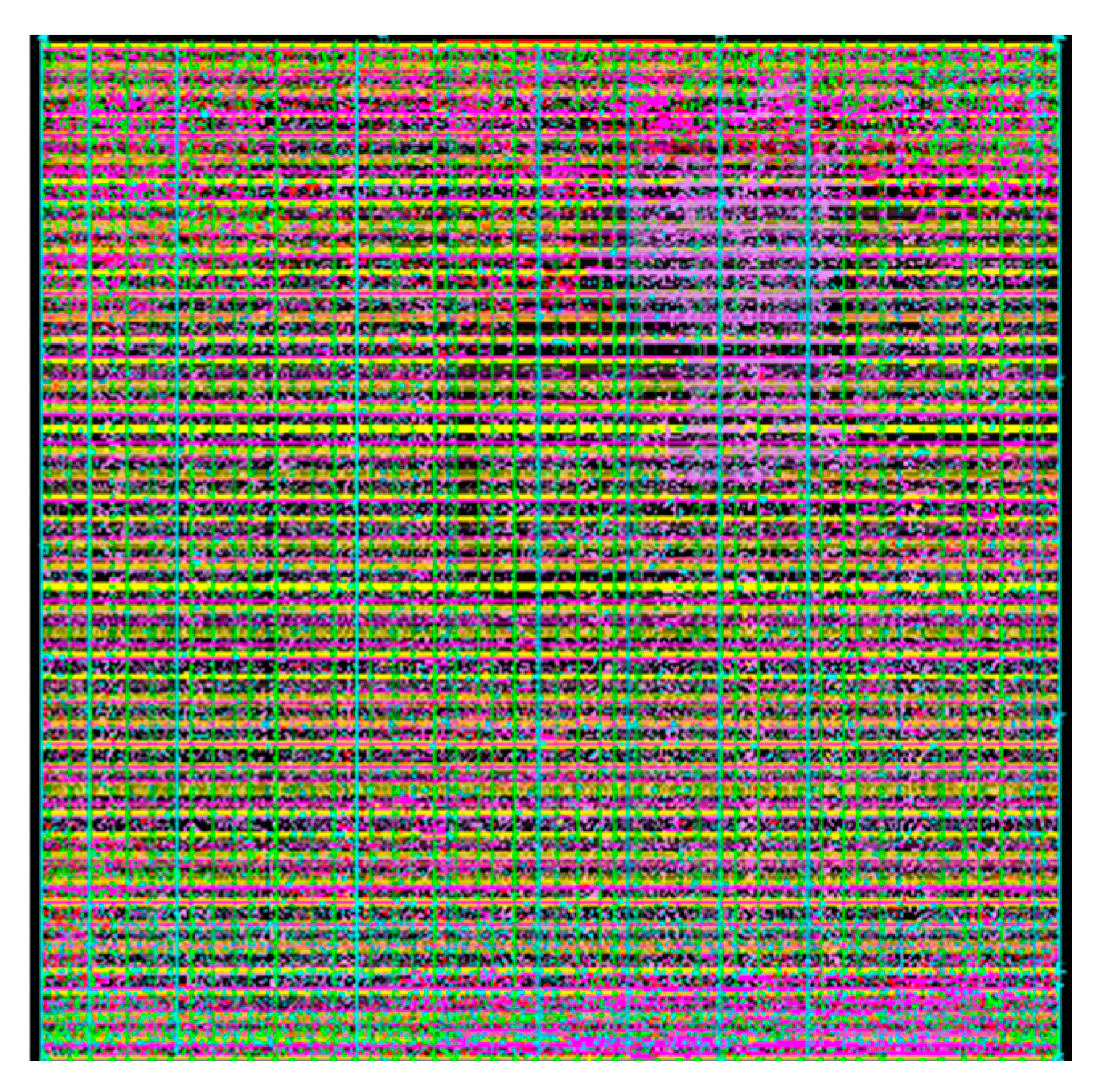

Figure 7 shows the circuit layout for the UA target recognition convolutional chip, based on TSMC 65nm technology. Simulation results indicate that the total area of the neural network chip is 0.21 mm². The total power consumption is measured at 90.82 mW, with the recognition time for a single target being 7.81 ns. The ASIC implementation of the UA target recognition system exhibits a significant reduction in power consumption and a substantial increase in computational speed compared to previous designs. This improvement underscores the benefits of using advanced ASIC technology in enhancing the efficiency and performance of specialized neural network applications in acoustic recognition tasks.

The overall architecture of the system, including the storage and computational modules that contribute to its high energy efficiency, is presented in

Figure 8. This design facilitates the impressive performance metrics achieved on the ASIC platform.

Table 2 presents a performance comparison of the DenseNet convolutional neural network for underwater acoustic target recognition deployed across different platforms. The ASIC solution significantly reduces power consumption and greatly enhances computational speed for the same convolutional neural network operations. This comparison highlights the efficiency of the ASIC architecture in optimizing both energy usage and processing time for complex neural computations.

5. Conclusion

This paper proposed the design of an underwater acoustic target recognition system based on a convolutional neural network, specifically employing a sparse DenseNet model. To address issues related to network complexity, fine-grained pruning was utilized to sparsify the weights. Software simulations show that at 0 dB SNR, the recognition accuracy was 98.73%. After applying 50% fine-grained pruning, accuracy slightly decreased to 96.11%, still validating the effectiveness and accuracy of the proposed method for this task. A prototype circuit was implemented on an FPGA, showing that recognition of a single UA target could be achieved in 13.3 ns with a power consumption of 189.02mW. When tested continuously on 1000 UA targets, the recognition accuracy reached 95%, indicating that the accelerator was capable of performing the recognition task effectively while maintaining high accuracy and efficiency. Furthermore, the total area of the chip for UA target recognition was 0.21 mm². The overall power consumption was 90.82mW, and the recognition time per target was only 7.81 ns when using an ASIC implementation. This highlights a substantial decrease in power requirements and an increase in computational speed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Wenhao Yang and Ding Ding; Data curation, Yinghao Lei, Liqin Zhu and Bingyao Peng; Formal analysis, Pei Tan; Funding acquisition, Ding Ding; Investigation, Bingyao Peng; Methodology, Wenhao Yang and Ding Ding; Project administration, Ding Ding; Resources, Liqin Zhu and Bingyao Peng; Software, Ao Ma, Pei Tan and Yinghao Lei; Supervision, Ding Ding; Validation, Ao Ma, Pei Tan and Yinghao Lei; Visualization, Liqin Zhu; Writing – original draft, Wenhao Yang and Ao Ma; Writing – review & editing, Ao Ma. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2025 National College Student Innovation Training Program Project, grant number 202510554085, and 2024 Hunan Provincial Undergraduate Innovation Training Program Project, grant number S202410554129, and The APC was funded by Hunan University of Technology and Business.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all individuals and institutions that provided support which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections, including administrative and technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| ASIC |

Application-Specific Integrated Circuit |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| CMOS |

Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor |

| CSB |

Compressed Sparse Banks |

| DNN |

Deep Neural Networks |

| DT |

Decision Trees |

| eLU |

Exponential Linear Unit |

| FPGA |

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays |

| GFCC |

Gammatone Frequency Cepstral Coefficients |

| GMM |

Gaussian Mixture Model |

| KNN |

k-nearest neighbors |

| LSTM |

Long Short-Term Memory |

| MEMD |

Modified Empirical Mode Decomposition |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| ReLU |

Rectified Linear Unit |

| SNR |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SVM |

Support Vector Machines |

| UA |

Underwater Acoustic |

| UASN |

Underwater Acoustic Sensor Networks |

References

- Wang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Q.; Cao, C.; Sang, Z.; Sun, M. Underwater communication signal recognition using sequence convolutional network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 46886–46899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Diamant, R. Adaptive modulation for long-range underwater acoustic communication. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 6844–6857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X. A direct position determination approach for underwater acoustic sensor networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2020, 69, 13033–13044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, F. Underwater acoustic target recognition: A combination of multi-dimensional fusion features and modified deep neural network. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1888. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Yu, S.; Li, G.; Xu, Y. The recognition method of MQAM signals based on BP neural network and bird swarm algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36078–36086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Wang, S. Bark-wavelet analysis and Hilbert–Huang transform for underwater target recognition. Def. Technol. 2013, 9, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L. Underwater target feature extraction and classification based on gammatone filter and machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Wavelet Analysis and Pattern Recognition (ICWAPR), Chengdu, China, 15–18 July 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, X.; Yuan, F.; Cheng, E. Underwater acoustic target recognition based on supervised feature-separation algorithm. Sensors 2018, 18, 4318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; van der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Zhang, C.; Yao, Z.; Xiao, W.; Nie, L.; Zhan, D.; Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, L. Efficient and effective sparse LSTM on FPGA with bank-balanced sparsity. In Proceedings of the 2019 ACM/SIGDA International Symposium on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA ’19), Seaside, CA, USA, 24–26 February 2019; pp. 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Xu, G.; Xu, X.; Jiang, H.; Tian, Z.; Ma, T. Multicenter Hierarchical Federated Learning with Fault-Tolerance Mechanisms for Resilient Edge Computing Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2025, 36, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.; Chen, X.; Huang, S.; Xiong, G.; Yan, K.; Zhou, X. Federal Learning Edge Network Based Sentiment Analysis Combating Global COVID-19. Comput. Commun. 2023, 204, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, X.; Shan, Y.; Li, F.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S. CLSpell: Contrastive Learning with Phonological and Visual Knowledge for Chinese Spelling Check. Neurocomputing 2023, 554, 126468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, F.; Li, S.; Dai, H.; Hu, C.; Dou, W.; Ni, Q. A K-Anonymity Based Schema for Location Privacy Preservation. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2017, 4, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, W. CNN-RNN Based Intelligent Recommendation for Online Medical Pre-Diagnosis Support. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2021, 18, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Wang, K.I.-K.; Wang, H.; Yang, L.T.; Jin, Q. Deep-Learning-Enhanced Human Activity Recognition for Internet of Healthcare Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 6429–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Xu, X.; Liang, W.; Zeng, Z.; Yan, Z. Deep-Learning-Enhanced Multitarget Detection for End–Edge–Cloud Surveillance in Smart IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 12588–12596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Li, W.; Yan, K.; Shimizu, S.; Wang, K.I.-K. Hierarchical Adversarial Attacks Against Graph-Neural-Network-Based IoT Network Intrusion Detection System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 9310–9319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Ren, J.; She, L.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. BOAT: A Block-Streaming App Execution Scheme for Lightweight IoT Devices. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 5, 1816–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Qiao, Y.; She, L.; Shen, R.; Ren, J.; Zhang, Y. Two Time-Scale Resource Management for Green Internet of Things Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, K.; Dong, L.; Pan, C.; Xu, W.; Yang, K. AI Driven Heterogeneous MEC System with UAV Assistance for Dynamic Environment: Challenges and Solutions. IEEE Netw. 2020, 35, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lv, P.; Wang, H.; Shi, C. SAR-U-Net: Squeeze-and-Excitation Block and Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling Based Residual U-Net for Automatic Liver Segmentation in Computed Tomography. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 208, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Liang, W.; Yan, K.; Li, W.; Wang, K. I.-K.; Ma, J.; Jin, Q. Edge-Enabled Two-Stage Scheduling Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning for Internet of Everything. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 10, 3295–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Nguyen, H.; Nguyen-Thoi, T.; Asteris, P. G.; Zhou, J. Improved Levenberg–Marquardt Backpropagation Neural Network by Particle Swarm and Whale Optimization Algorithms to Predict the Deflection of RC Beams. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38 (Suppl. 5), 3847–3869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Wang, K.; Dong, L.; Pan, C.; Yang, K. Stacked Autoencoder-Based Deep Reinforcement Learning for Online Resource Scheduling in Large-Scale MEC Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 9278–9290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Ren, J.; She, L.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Ren, K. EdgeSanitizer: Locally Differentially Private Deep Inference at the Edge for Mobile Data Analytics. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 5140–5151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Dong, L.; Wang, K.; Yang, K.; Pan, C. Distributed Resource Scheduling for Large-Scale MEC Systems: A Multiagent Ensemble Deep Reinforcement Learning with Imitation Acceleration. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 6597–6610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Liu, W.; Yang, Q.; Mao, X.; Li, F. Trust Based Task Offloading Scheme in UAV-Enhanced Edge Computing Network. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2021, 14, 3268–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bhuiyan, M. Z. A.; Yang, X.; Wang, T.; Xu, X.; Hayajneh, T.; Khan, F. AntiConcealer: Reliable Detection of Adversary Concealed Behaviors in EdgeAI-Assisted IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 22184–22193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, K. Compressive Sensing and Random Walk Based Data Collection in Wireless Sensor Networks. Comput. Commun. 2018, 129, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).