1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) has emerged as a significant global health challenge, characterized by a constellation of interconnected metabolic abnormalities, including central obesity, elevated blood pressure, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and impaired glucose regulation [

1]. Together, these risk factors significantly elevate the likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases, the two leading causes of global morbidity and mortality [

2]. Alarmingly, current estimates suggest that nearly one-quarter of the world’s adult population is affected by MetS, with prevalence continuing to rise in parallel with the global obesity epidemic and sedentary lifestyles [

3,

4].

Although MetS is not classified as a disease in itself, it functions as a potent indicator of underlying pathophysiological dysregulation[

5]. The clustering of its components is not random; rather, it reflects a shared basis in chronic low-grade systemic inflammation and insulin resistance [

6]. One of the challenges with MetS is its insidious progression [

7]. Often asymptomatic in its early stages [

2], it may go undetected until serious complications such as myocardial infarction [

8], stroke [

9], or type 2 diabetes manifest [

10]. This silent nature underscores the need for early identification and proactive management of individuals at risk [

11].

A growing body of evidence supports the use of inflammatory biomarkers as early indicators of metabolic dysregulation [

11]. Among these, C-reactive protein (CRP) has emerged as one of the most clinically relevant [

12]. CRP is a hepatic acute-phase protein produced in response to cytokines, especially interleukin-6 (IL-6), and its levels rise in response to systemic inflammation [

13]. Numerous studies have demonstrated a strong correlation between elevated serum CRP [

14] and the onset and severity of MetS [

15], suggesting its value in both risk prediction and monitoring disease progression. Elevated CRP levels are also associated with less frequently assessed, but clinically relevant, features of MetS such as endothelial dysfunction[

16], hypercoagulability[

17], and microalbuminuria [

18], further reinforcing its role as a surrogate marker of systemic inflammation and metabolic imbalance [

19]. CRP has emerged as a strong and independent predictor of both the onset of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease [

18,

19,

20].

Despite its clinical utility, measuring CRP in serum presents practical limitations, particularly in large-scale screening contexts or among populations where venipuncture is not feasible [

21]. Blood collection is invasive, potentially distressing, and may require trained personnel, sterile equipment, and controlled conditions, all of which are barriers in low-resource settings or when high-frequency monitoring is necessary.

This has led to growing interest in saliva as a diagnostic fluid [

22]. Saliva offers a convenient, non-invasive, and cost-effective alternative to blood, with the additional advantage of easy and repeated sampling [

23]. The use of saliva for diagnostic purposes is expanding across several domains, including infectious diseases, hormonal disorders, and cardiovascular risk assessment [

24,

25,

26]. Importantly, emerging evidence suggests that salivary CRP levels strongly correlate with serum CRP concentrations [

27] indicating that salivary CRP may reflect systemic inflammatory status and thus hold potential as a diagnostic biomarker for MetS.

Despite the growing number of studies investigating salivary CRP [

27,

28] the literature remains fragmented and inconclusive. Variability in population characteristics, saliva collection protocols, CRP assay methods, and diagnostic criteria for MetS has contributed to inconsistent findings. Some studies report strong associations between salivary CRP and MetS components [

29] however, questions remain about the consistency of salivary CRP in detecting early metabolic dysfunction compared to its serum counterpart. Given this gap in Knowledge, there is a compelling need to systematically evaluate the existing evidence. A rigorous synthesis of current research is necessary to determine whether salivary CRP can be considered a reliable, non-invasive alternative to serum-based CRP testing in identifying individuals at risk for MetS.

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to assess the association between salivary CRP levels and the presence of metabolic syndrome. By pooling data from diverse populations and methodologies, this study seeks to clarify the diagnostic potential of salivary CRP, evaluate its correlation with MetS components, and explore its possible integration into early screening programs and public health initiatives. Establishing saliva as a viable diagnostic medium for MetS could offer a transformative tool in the early detection and management of metabolic risk, especially in underserved populations and community settings

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

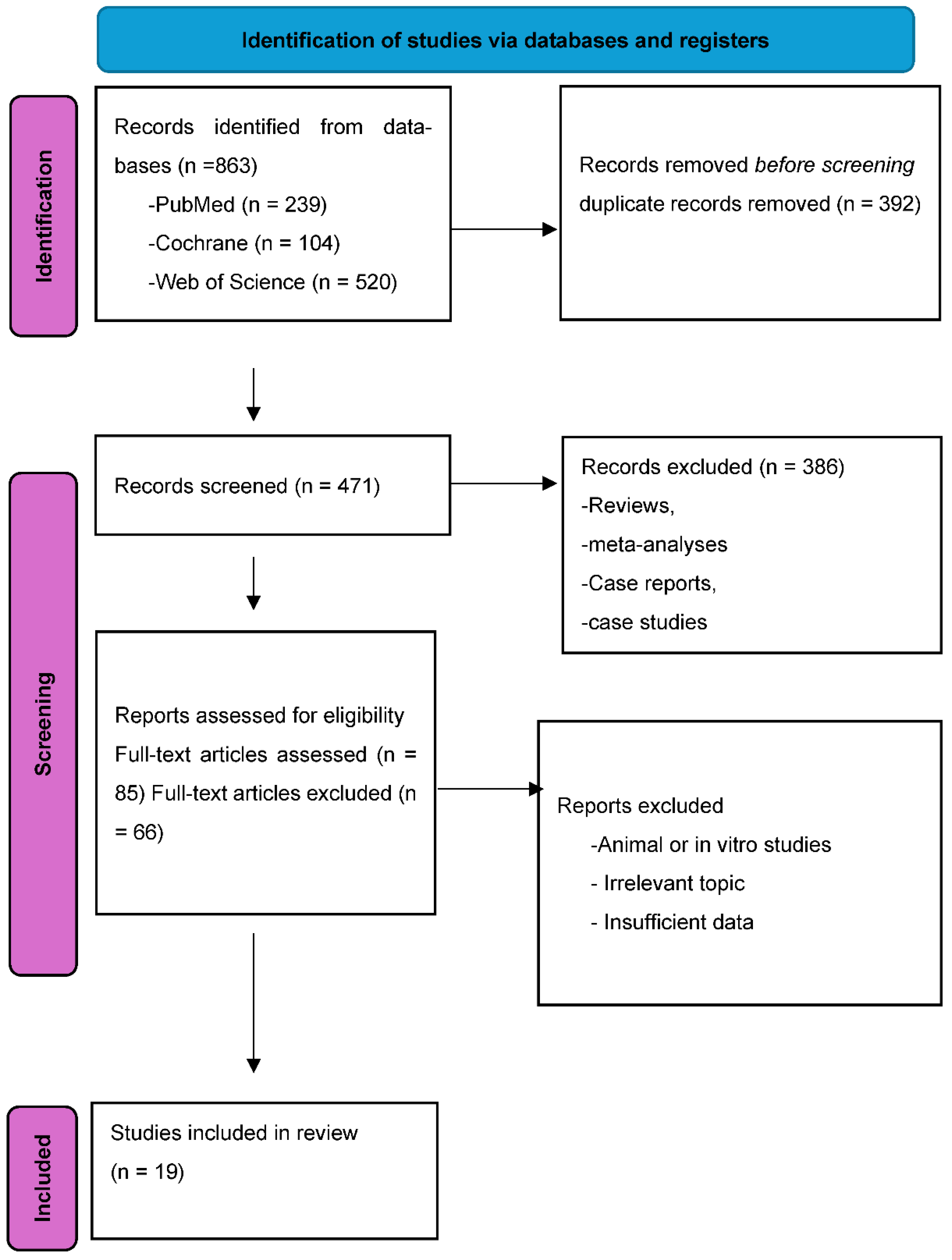

Publicly This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines.[

30] A structured literature search was performed in three electronic databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science, covering all records up to December 2024. PRISMA flow of the selection process is shown in

Figure 1.

The PECO (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome) framework guided study selection. The target population included individuals of any age, gender, and geographic location. The exposure of interest was salivary C-reactive protein (CRP) levels. Comparators were individuals without metabolic syndrome (MetS). The outcome was the presence of MetS, defined according to standard diagnostic criteria and characterized by one or more of the following: central obesity (BMI, waist circumference), hyperglycemia (type 2 diabetes, elevated glucose or HbA1c), hypertension, dyslipidemia (high LDL or low HDL), and cardiovascular disease.

Search terms included combinations of “saliva,” “salivary,” “C-reactive protein,” “CRP,” and metabolic-related terms such as “metabolic syndrome,” “obesity,” “BMI,” “type 2 diabetes,” “hypertension,” and “dyslipidemia.” No language restrictions were applied. After duplicate removal, titles and abstracts were screened, followed by full-text review.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

Original, peer-reviewed human studies.

Quantitative assessment of salivary CRP levels in both MetS and non-MetS groups.

Clear diagnostic criteria for MetS.

Exclusion criteria were:

Non-human or in vitro studies.

Lack of comparative salivary CRP data.

Review articles, case reports, editorials, or commentaries.

When data were missing or unclear, study authors were contacted. Two of the three contacted authors provided the required information; one study was excluded due to non-response.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two independent reviewers extracted study details including publication year, country, study design, sample size, age group, diagnostic criteria, CRP assay methods, and reported salivary CRP concentrations. All salivary CRP values were converted to picograms per milliliter (pg/mL) for consistency.

Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies. Studies scoring 1–3 were classified as low quality, 4–6 as moderate, and 7–9 as high quality. [

31,

32]Discrepancies were resolved through consensus.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

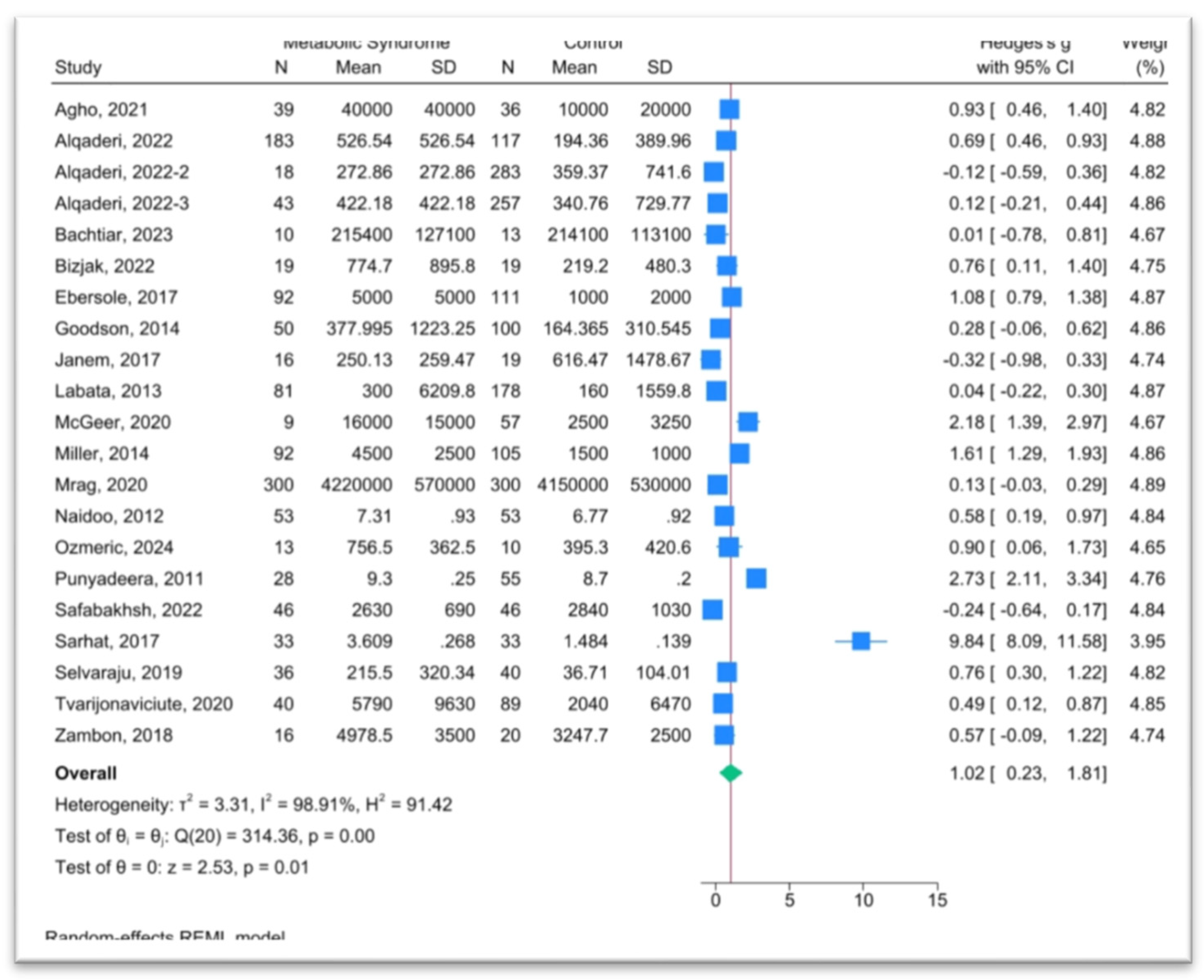

Meta-analysis was performed using STATA version 17. For each study, standardized mean differences (SMDs) were computed to account for varying measurement scales. Where CRP levels were reported as medians with interquartile ranges, mean and standard deviation values were estimated using validated statistical conversions.

A random-effects model (DerSimonian and Laird) was used to account for heterogeneity across populations, methodologies, and MetS definitions. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

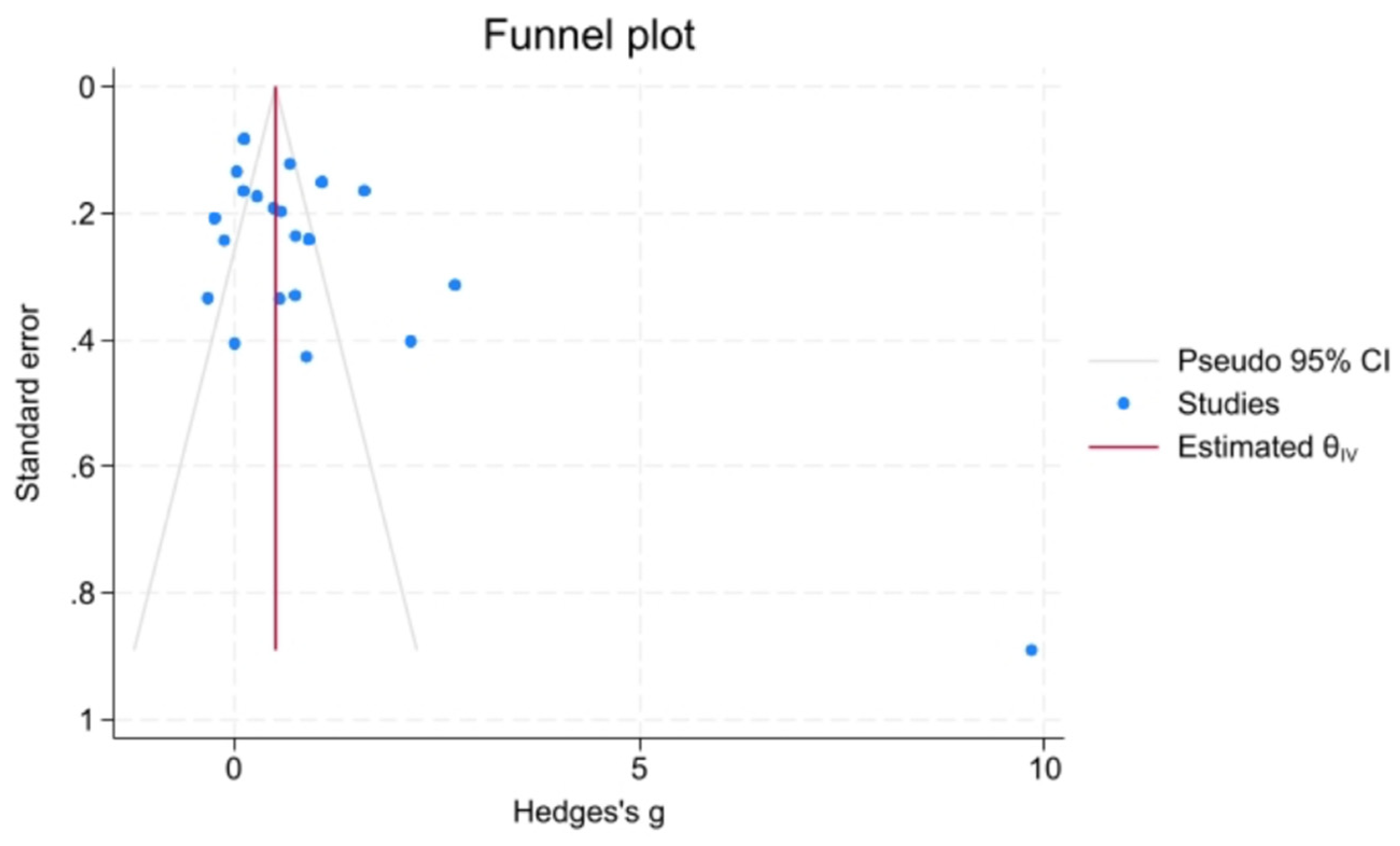

Heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic and Cochran’s Q test. I² values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were interpreted as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Publication bias was evaluated via funnel plot asymmetry, as seen in

Figure 2, and tested with Egger’s and Begg’s tests.

3. Results

Study Selection and Characteristics

A total of 863 records were identified through database searches. After removing 392 duplicates, 471 records underwent screening. Following abstract and full-text review, 19 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis, representing a cumulative sample of 3,157 individuals from 15 countries.

The included studies spanned diverse populations ranging from children to older adults and comprised both males and females. Most studies employed cross-sectional designs, with others utilizing case-control and cohort methodologies. The diagnostic criteria for MetS varied, with most studies referencing ATP III, IDF, or WHO guidelines. All studies used validated laboratory methods for salivary CRP quantification, predominantly enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Most studies were rated as moderate to high quality, with NOS scores ranging from 5 to 8 out of a possible 9. Common strengths included clearly defined objectives, appropriate selection of cases and controls, and reliable CRP assay techniques. However, several studies lacked detailed reporting on blinding procedures, sample size justification, or control for potential confounders such as oral health status and smoking. Variability in the diagnostic criteria used for defining MetS also introduced potential risk of misclassification bias. Despite these limitations, the overall quality of evidence was sufficient to support a meaningful meta-analysis, and no studies were excluded on the basis of poor quality alone. Quality scores were not significantly associated with effect sizes in subgroup analyses, suggesting that the observed association between salivary CRP and MetS was not driven solely by study quality.

Publication Bias

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). Most studies were rated as moderate to high quality. NOS scores for each study are presented in

Table 1. The primary methodological limitations observed were the lack of blinding and inconsistencies in the diagnostic criteria used for metabolic syndrome (MetS) across studies.

Key study characteristics are presented, including author, year, country, outcome assessed, participant age, study design, population source, and quality rating according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS). The studies represent diverse geographical regions, with NOS scores indicating moderate to high methodological quality.

4. Discussion

The findings of this meta-analysis demonstrate an elevation in salivary CRP levels among individuals with metabolic syndrome (MetS) compared to healthy controls. This aligns with the broader understanding of CRP as a sensitive marker of systemic inflammation and supports the emerging utility of saliva as a viable, non-invasive diagnostic medium for metabolic disorders [

27].

The observed association remained consistent despite substantial heterogeneity across studies, suggesting a strong underlying biological signal. Variability in study design, population demographics, CRP assay techniques, and diagnostic criteria for MetS likely contributed to the heterogeneity, yet the consistency of elevated salivary CRP across diverse settings underscores its potential reliability as a biomarker. Importantly, all studies included in the analysis reported elevated salivary CRP levels in participants with MetS or its components, such as obesity[

35], diabetes[

36], and cardiovascular disease [

37], providing consistent evidence of its diagnostic relevance across diverse clinical contexts. One exception was noted in a single study [

33], where CRP levels were higher in the control group compared to participants with diabetes; however, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.01).

The generalizability of the findings is reinforced by the geographic and demographic diversity of the included studies. Data were drawn from 15 countries, including both high-income and middle-income settings, and encompassed a wide age range, from children and adolescents to older adults. This global representation strengthens the argument that salivary CRP may be a universally appli-cable biomarker for MetS risk, adaptable to various healthcare environments, including those with limited access to conventional diagnostic tools. The inclusion of both pediatric and adult populations further suggests that salivary CRP can serve as a longitudinal indicator, potentially valuable throughout the life course.

At the molecular level, CRP is an acute-phase protein synthesized predominantly by hepatocytes in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 [

38]. While conventionally measured in serum [

39], CRP is increasingly detectable in saliva [

27] where its concentration reflects systemic inflammatory activity [

28]. This is particularly significant because saliva collection is non-invasive, stress-free, and easily repeatable, offering practical advantages over venipuncture, especially for vulnerable or high-volume populations [

40].

Previous literature supports the validity of salivary CRP as a proxy for systemic inflammation. Studies such as Ouellet-Morin et al. (2011) and Out et al. (2012) demonstrated moderate to strong correlations between salivary and serum CRP levels under controlled collection conditions, establishing proof-of-concept for clinical applicability [

28,

41]. La Fratta et al. (2018) extended this evidence by showing that salivary CRP dynamics mirror those of serum CRP across both physiological and pathological states [

42]. These findings are complemented by systematic reviews that confirm the analytical validity of salivary CRP assays and their potential utility in monitoring chronic inflammatory states [

21].

This review also revealed that salivary CRP levels were elevated not only in individuals diagnosed with MetS but also in subgroups defined by single MetS components. Five studies compared CRP levels in participants with and without diabetes [

33,

36,

43,

44,

45], nine in obese versus non-obese individuals [

34,

35,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52] and six in participants with cardiovascular disease [

37,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57]. Some studies addressed more than one component[

49] highlighting the multifactorial nature of MetS and the broad inflammatory footprint captured by CRP. This cumulative evidence suggests that salivary CRP could be useful not just for diagnosing MetS, but also for identifying early-stage metabolic risk and stratifying individuals by disease severity or progression likelihood.

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to synthesize evidence on salivary CRP specifically in the context of MetS. While previous reviews have focused on serum CRP [

58], or generalized inflammatory markers [

13], our work addresses a significant gap in the literature and affirms that salivary CRP correlates with metabolic dysfunction across multiple domains [

36,

59]. These findings are consistent with earlier meta-analyses of serum CRP [

15] suggesting that salivary assays may offer a practical alternative without sacrificing diagnostic accuracy.

From a public health perspective, the implications are substantial. Integrating saliva-based CRP testing into routine screening programs could facilitate earlier detection of metabolic risk, especially in settings where access to blood testing is limited or logistically challenging. This approach could be particularly impactful in pediatric care, school health screenings, and remote or resource-constrained environments. Additionally, the non-invasive nature of saliva collection lends itself to repeated sampling, making it suitable for monitoring inflammatory trends over time and assessing responses to interventions.

Despite the promising findings, several limitations should be acknowledged. The diagnostic criteria for MetS varied across studies, which may have influenced participant categorization and CRP level comparisons. Additionally, salivary CRP concentrations can be affected by local oral inflammatory conditions such as gingivitis or periodontitis, which were not consistently reported or controlled for. This introduces potential confounding, especially in populations with high rates of undiagnosed oral disease. Furthermore, the predominance of cross-sectional designs precludes causal inferences; longitudinal studies are needed to establish whether elevated salivary CRP precedes the onset of MetS or merely reflects existing disease.

To advance the field, future research must prioritize the standardization of saliva collection protocols and CRP assay techniques to reduce methodological variability and improve data comparability. Large-scale, prospective cohort studies should explore the predictive value of salivary CRP for MetS development over time, ideally adjusting for key confounders such as age, sex, smoking status, oral health, and medication use. It would also be beneficial to evaluate the cost-effectiveness and feasibility of deploying salivary CRP testing in real-world screening programs, particularly within schools, community clinics, and primary care settings.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis provides compelling evidence that salivary CRP is elevated in individuals with metabolic syndrome and supports its emerging role as a practical, non-invasive biomarker for early detection and risk stratification. While more research is needed to confirm its predictive utility and define clinical thresholds, salivary CRP represents a promising tool in the shift toward accessible, preventative, and personalized approaches to metabolic health surveillance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.A.; Data Curation, R.G., S.P., A.A.A., A.A., N.A., N.A.D., H.B., W.A.-S., S.A., F.A.; Statistical Analysis, S.P.; Investigation, R.G.; Methodology, R.G. H.A.; Project Administration, H.A.; Resources, R.G.; Supervision, H.A..; Visualization, H.A.; Writing (Original Draft Preparation), R.G.; Writing (Review & Editing) Y.B., H.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

References

- Samson, S.L. and A.J. Garber, Metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics, 2014. 43(1): p. 1-23.

- Huang, P., A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009; 2 (5–6): 231–7. [CrossRef]

- Saklayen, M.G., The Global Epidemic of the Metabolic Syndrome. Current Hypertension Reports, 2018. 20(2): p. 12. [CrossRef]

- Pigeot, I. and W. Ahrens, Epidemiology of metabolic syndrome. Pflügers Archiv-European Journal of Physiology, 2025: p. 1-12.

- Alberti, K.G.M., P. Zimmet, and J. Shaw, The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. The Lancet, 2005. 366(9491): p. 1059-1062. [CrossRef]

- Hotamisligil, G.S., Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature, 2006. 444(7121): p. 860-867.

- Grundy, S.M., Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology, 2008. 28(4): p. 629-636. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W., et al., Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation, 2005. 112(20): p. 3066-3072. [CrossRef]

- Mottillo, S., et al., The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2010. 56(14): p. 1113-1132.

- Cameron, A.J., J.E. Shaw, and P.Z. Zimmet, The metabolic syndrome: prevalence in worldwide populations. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics, 2004. 33(2): p. 351-375. [CrossRef]

- Gesteiro, E., et al., Early identification of metabolic syndrome risk: A review of reviews and proposal for defining pre-metabolic syndrome status. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases, 2021. 31(9): p. 2557-2574. [CrossRef]

- Kilpatrick, E.L. and D.M. Bunk, Reference measurement procedure development for C-reactive protein in human serum. Analytical chemistry, 2009. 81(20): p. 8610-8616. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, T.A., et al., Markers of inflammation and cardiovascular disease: application to clinical and public health practice: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Heart Association. circulation, 2003. 107(3): p. 499-511.

- Ridker, P.M., et al., C-Reactive Protein, the Metabolic Syndrome, and Risk of Incident Cardiovascular Events. Circulation, 2003. 107(3): p. 391-397. [CrossRef]

- Festa, A., et al., Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Circulation, 2000. 102(1): p. 42-47.

- Verma, S., et al., Endothelin antagonism and interleukin-6 inhibition attenuate the proatherogenic effects of C-reactive protein. Circulation, 2002. 105(16): p. 1890-1896. [CrossRef]

- Sakkinen, P.A., et al., Analytical and biologic variability in measures of hemostasis, fibrinolysis, and inflammation: assessment and implications for epidemiology. American journal of epidemiology, 1999. 149(3): p. 261-267. [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.D., et al., C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. jama, 2001. 286(3): p. 327-334.

- Ridker, P.M., et al., Measurement of C-reactive protein for the targeting of statin therapy in the primary prevention of acute coronary events. New England Journal of Medicine, 2001. 344(26): p. 1959-1965. [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M., et al., C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events: an 8-year follow-up of 14 719 initially healthy American women. Circulation, 2003. 107(3): p. 391-397. [CrossRef]

- Babaei, M., et al., The role of salivary C-reactive protein in systemic and oral disorders: A systematic review. Medical journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 2022. 36: p. 138. [CrossRef]

- Pfaffe, T., et al., Diagnostic potential of saliva: current state and future applications. Clinical chemistry, 2011. 57(5): p. 675-687. [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.A., et al., Saliva as a diagnostic tool for oral and systemic diseases. Journal of oral biology and craniofacial research, 2016. 6(1): p. 67-76. [CrossRef]

- Malon, R.S., et al., Saliva-based biosensors: noninvasive monitoring tool for clinical diagnostics. BioMed research international, 2014. 2014(1): p. 962903. [CrossRef]

- Malamud, D. and I.R. Rodriguez-Chavez, Saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Dental Clinics of North America, 2011. 55(1): p. 159.

- Sugimoto, M., et al., Quantification of salivary charged metabolites using capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight-mass spectrometry. Bio-protocol, 2020. 10(20): p. e3797-e3797. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.S., et al., Current developments in salivary diagnostics. Biomarkers in medicine, 2010. 4(1): p. 171-189. [CrossRef]

- Out, D., et al., Assessing salivary C-reactive protein: longitudinal associations with systemic inflammation and cardiovascular disease risk in women exposed to intimate partner violence. Brain Behav Immun, 2012. 26(4): p. 543-51. [CrossRef]

- Dezayee, Z.M. and M.S. Al-Nimer, Saliva C-reactive protein as a biomarker of metabolic syndrome in diabetic patients. Indian J Dent Res, 2016. 27(4): p. 388-391. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J., et al., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. bmj, 2021. 372.

- Wells, G.A., et al., The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000.

- Luchini, C., et al., Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. World Journal of Meta-Analysis, 2017. 5(4): p. 80-84. [CrossRef]

- Janem, W.F., et al., Salivary inflammatory markers and microbiome in normoglycemic lean and obese children compared to obese children with type 2 diabetes. PloS one, 2017. 12(3): p. e0172647. [CrossRef]

- Sarhat, E.R., I.J. Mohammed, and A.I. Hamad, Biochemistry of Serum and Saliva in Obese Individuals with Periodontitis: Case-control study. JODR, 2017. 4(1): p. 2-10. [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, T., et al., Elevated salivary C-reactive protein predicted by low cardio-respiratory fitness and being overweight in African children. Cardiovascular Journal of Africa, 2012. 23(9): p. 501-506. [CrossRef]

- Agho, E.T., et al., Salivary inflammatory biomarkers and glycated haemoglobin among patients with type 2 diabetic mellitus. BMC Oral Health, 2021. 21(1): p. 101. [CrossRef]

- Labat, C., et al., Inflammatory mediators in saliva associated with arterial stiffness and subclinical atherosclerosis. J Hypertens, 2013. 31(11): p. 2251-8; discussion 2258. [CrossRef]

- Ansar, W. and S. Ghosh, C-reactive protein and the biology of disease. Immunologic research, 2013. 56: p. 131-142.

- Pepys, M.B. and G.M. Hirschfield, C-reactive protein: a critical update. The Journal of clinical investigation, 2003. 111(12): p. 1805-1812. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Córdoba, B. and J. Santiago-García, Saliva: a fluid of study for OMICS. Omics: a journal of integrative biology, 2014. 18(2): p. 87-97. [CrossRef]

- Ouellet-Morin, I., et al., Validation of a high-sensitivity assay for C-reactive protein in human saliva. Brain Behav Immun, 2011. 25(4): p. 640-6. [CrossRef]

- Castagnola, M., et al., Potential applications of human saliva as diagnostic fluid. Acta Otorhinolaryngologica Italica, 2011. 31(6): p. 347.

- Bachtiar, E., et al., The utility of salivary CRP and IL-6 as a non-invasive measurement evaluated in patients with COVID-19 with and without diabetes. F1000Research, 2024. 12: p. 419.

- Mrag, M., et al., Saliva diagnostic utility in patients with type 2 diabetes: Future standard method. J Med Biochem, 2020. 39(2): p. 140-148. [CrossRef]

- Alqaderi, H., et al., Salivary Biomarkers as Predictors of Obesity and Intermediate Hyperglycemia in Adolescents. Front Public Health, 2022. 10: p. 800373. [CrossRef]

- Selvaraju, V., J.R. Babu, and T. Geetha, Association of salivary C-reactive protein with the obesity measures and markers in children. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes, 2019. 12: p. 1239-1247. [CrossRef]

- Safabakhsh, D., et al., Comparison of salivary interleukin-6, interleukin-8, C - reactive protein levels and total antioxidants capacity of obese individuals with normal-weight ones. Rom J Intern Med, 2022. 60(4): p. 215-221. [CrossRef]

- Bizjak, D.A., et al., Pro-inflammatory and (Epi-)genetic markers in saliva for disease risk in childhood obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis, 2022. 32(6): p. 1502-1510. [CrossRef]

- Alqaderi, H., et al., Salivary Biomarkers as Predictors of Obesity and Intermediate Hyperglycemia in Adolescents. Frontiers in Public Health, 2022. 10. [CrossRef]

- Goodson, J.M., et al., Metabolic Disease Risk in Children by Salivary Biomarker Analysis. Plos One, 2014. 9(6). [CrossRef]

- Tvarijonaviciute, A., et al., Saliva as a non-invasive tool for assessment of metabolic and inflammatory biomarkers in children. Clin Nutr, 2020. 39(8): p. 2471-2478. [CrossRef]

- Zambon, M., et al., Inflammatory and Oxidative Responses in Pregnancies With Obesity and Periodontal Disease. Reprod Sci, 2018. 25(10): p. 1474-1484. [CrossRef]

- Ebersole, J.L., et al., Salivary and serum adiponectin and C-reactive protein levels in acute myocardial infarction related to body mass index and oral health. J Periodontal Res, 2017. 52(3): p. 419-427. [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.S., et al., Utility of salivary biomarkers for demonstrating acute myocardial infarction. J Dent Res, 2014. 93(7 Suppl): p. 72s-79s.

- Punyadeera, C., et al., One-step homogeneous C-reactive protein assay for saliva. J Immunol Methods, 2011. 373(1-2): p. 19-25. [CrossRef]

- McGeer, P.L., et al., Saliva Diagnosis as a Disease Predictor. J Clin Med, 2020. 9(2). [CrossRef]

- Ozmeric, N., et al., Interaction between hypertension and periodontitis. Oral Dis, 2024. 30(3): p. 1622-1631. [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M., et al., C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. New England journal of medicine, 2000. 342(12): p. 836-843. [CrossRef]

- Podeanu, M.-A., et al., C-reactive protein as a marker of inflammation in children and adolescents with metabolic syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines, 2023. 11(11): p. 2961. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).