1. Introduction: Bridging Anti-Aging, Regeneration, and Oncology Through Senescence

Interest in senescence modulation has recently been brought to light as its role in aging, tissue repair, and cancer biology becomes clearer. Cellular senescence provides a common mechanistic foundation linking anti-aging medicine, regenerative aesthetics, and oncology [

1]. This review synthesizes the literature to clarify these intersections and identify translational opportunities. Rather than proposing senescence solely as a target for symptom management, this analysis frames it as a fundamental biological process with therapeutic implications across disciplines.

Human health and lifespan are closely linked to the aging process, which involves a gradual decline in physiological function and increased vulnerability to diseases, including cancer. Recent developments in senescence research have identified compelling therapeutic targets, ranging from the establishment of integrated treatment models for both regenerative and aesthetic treatments to anti-neoplastic interventions. This review synthesizes the mechanistic underpinnings that interrelate these disciplines, demonstrating how targeted interventions against senescent cells (SnC) provide valuable translational insights for developing integrated treatment models in regenerative medicine and oncology. The novelty of this work lies in its systematic synthesis of perspectives from these seemingly unrelated fields, unified by cellular senescence as a central mechanistic treatment target. This comprehensive analysis, based on an integrated synthesis of the literature, including over 50 key recent publications, is structured to provide a detailed overview of senescence modulation as a unified therapeutic approach. Ultimately, the goal is to identify potential therapeutic targets that induce tumor regression, mitigate age-related vulnerabilities, and promote tissue homeostasis and regeneration, leading to improved patient-reported outcomes and enhanced overall survival.

2. The Fundamental Role of Senescence: A Shared Biological Mechanism

Cellular senescence represents a core biological response to diverse stressors—including DNA damage, telomere attrition, and oncogenic signaling—that collectively drive cells into an irreversible state of arrest of the cell cycle and the establishment of the SnC state (

Figure 1) [

2,

3]. Persistent SnCs, characterized by altered metabolism and apoptosis resistance, become pathogenic through chronic secretion of SASP factors. Crucially, SnCs transform the cellular microenvironment by secreting a complex array of pro-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proteases, collectively known as the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP). While senescence initially acts as a tumor-suppressive mechanism, the chronic presence of SnCs and their SASP-mediated inflammation drives tissue dysfunction, chronic inflammation ("inflammaging"), and age-related pathology. Senescence subtypes—replicative, oncogene-induced, therapy-induced, and mitochondria-induced—illustrate the diversity of triggers and contexts shaping cellular outcomes [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

3. Senescence Modulation in Dermatology, Anti-Aging and Regenerative Aesthetics: A Different Approach to Rejuvenation

In dermatologic and aesthetic medicine, targeting senescence underlies new rejuvenation strategies. Studies have identified key senescence-related genes in dermatologic conditions such as psoriasis [

9]. Biologic agents, such as adalimumab (a TNF-α inhibitor), secukinumab (an IL-17A inhibitor), and ustekinumab (an IL-12/23 inhibitor), are effective in targeting specific cytokines. By neutralizing these pro-inflammatory cytokines, these monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) disrupt the inflammatory cascade that drives the characteristic skin lesions of psoriasis, leading to clinical remission and improved patient quality of life [

10]. The mechanism of action is linked to their anti-inflammatory properties, which can indirectly modulate the chronic, low-grade inflammation associated with SASP [

11]. Also, targeting SnCs holds significant promise in anti-aging and regenerative aesthetics. The accumulation of these cells in the skin contributes to visible signs of aging, including wrinkles, loss of elasticity, and impaired wound healing [

12]. Beyond cosmetic improvements, these targets also appear promising in chronic wound care through the clearance of SnCs that impede tissue repair and regeneration, offering significant advancements in regenerative medicine for dermatological applications [

13].

The field of senotherapeutics encompasses a diverse range of strategies, which are broadly classified as senolytics (aimed at eliminating SnCs) and senomorphics (aimed at suppressing the detrimental effects of the SASP). These interventions have emerged as central to anti-aging and regenerative strategies because they target the cellular drivers of inflammaging [

14]. For instance, some interventions in preclinical or early clinical research demonstrate the efficacy of these approaches in improving skin health, promoting collagen production, and enhancing tissue regeneration [

15,

16,

17]. The potential to reverse age-related aesthetic changes by directly addressing cellular senescence, which offers a novel and biologically grounded approach compared to traditional cosmetic procedures [

17]. Conventional approaches to addressing visible signs of aging, such as skin wrinkling and hair loss, often involve interventions like laser therapies [

18,

19], dermal fillers [

20], and polynucleotide (PN) or polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) injections, which aim to stimulate collagen production and tissue regeneration [

21,

22]. More advanced strategies include the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [

23] and various peptides, such as Pep 14, to promote cellular repair and revitalization [

24]. While these methods offer variable levels of aesthetic improvement, targeting cellular senescence directly with senolytics or senomorphics presents a novel and biologically grounded approach that could potentially enhance the longevity and efficacy of these traditional procedures by addressing the root cause of age-related tissue dysfunction, offering a promise for more profound and sustained rejuvenation [

25].

4. Senescence Modulation in Oncology: A Multi-level Therapeutic Target

Cellular senescence may play a complex, dualistic role in the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

26], as the definition and function of SnCs vary significantly depending on the tissue type, cellular origin, and specific stressors [

27]. The primary therapeutic target is the SnC itself, which must be eliminated or neutralized to prevent tumor recurrence [

28]. The key to this strategy lies in recognizing that SnCs and many established tumor cells share overlapping Senescence-Associated Pro-Survival Pathways (SAPS). This shared vulnerability provides a direct translational bridge between oncology and senotherapeutics [

28]. For instance, both SnCs and many cancer cells rely on the anti-apoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family of proteins (BCL-2, BCL-xL, and MCL-1) for their survival. This means that many pro-apoptotic cancer therapies developed for malignancies (e.g., BCL-2 inhibitors) often possess inherent senolytic activity, making them immediately relevant for clearing pathogenic SnCs in aging tissues [

27,

28,

29].

Beyond shared survival pathways, senescence also acts as a key effector mechanism in conventional anticancer therapies [

30]. For instance, chemotherapy and radiation induce Therapy-Induced Senescence (TIS) in cancer cells, initially acting as a barrier against tumor progression. However, the accumulation of these Therapy-Induced Senescent (TISnt) cells is a significant obstacle to long-term efficacy. This is due to the sustained secretion of the SASP, which remodels the TME to promote inflammation, angiogenesis, and, critically, therapy resistance and cancer recurrence [

29]; hence, treatment combination becomes necessary. The combination of traditional pro-senescence therapy (chemotherapy) with senolytics (to clear TISnt cells) [

30] or senomorphics (to suppress the detrimental SASP) is a primary strategy currently undergoing rigorous preclinical and clinical investigation to enhance treatment efficacy and reduce adverse effects [

31,

32].

Emerging modalities, including monoclonal antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and CAR-T cell therapy, increasingly intersect with senescence biology. SnCs can create an immunosuppressive TME that dampens the anti-tumor immune response, an effect that immunotherapeutic agents aim to overcome [

33]. The efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab (which target Programmed Death-1 [PD-1]), is directly linked to overcoming the TME's immunosuppressive state [

34]. Senescence-induced immunosuppression, often driven by components of the SASP, can lead to ICI resistance [

35]. This suggests a link between senescence modulation and ICI response. Similarly, the interplay between senescence pathways and the effectiveness of monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy is emerging as a critical area of investigation [

36]. These connections, including a potential link between senescence and cancer immunoediting, are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the TME. For instance, antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) serve as a highly targeted delivery system for potent cytotoxic drugs to SASP components that express specific cell surface markers [

35]. Neutralizing antibodies also inhibit the release or activity of pro-tumorigenic SASP factors, such as inflammatory cytokines [

37]. The use of mAbs, such as adalimumab, primarily used for inflammatory bowel disease and certain autoimmune diseases, and siltuximab, an interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitor employed in the treatment of Castleman’s disease, illustrates the principle of modulating inflammatory pathways exacerbated by SnCs [

35,

38]. This concept may extend to older agents, such as rituximab and regorafenib, whose known clinical effects can also be viewed through the lens of senescence modulation [

39,

40]. Lastly, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, which have revolutionized the treatment of hematologic malignancies, including lymphomas, leukemias, and myeloma [

41], are being engineered to target SnCs specifically. Emerging research indicates that CAR-T cells can be engineered to specifically target SnCs, with targets such as FAP-alpha (Fibroblast Activation Protein-alpha) and uPAR (urokinase plasminogen activator receptor) showing potential to not only enhance the anti-tumor immune response but also mitigate the pro-tumorigenic effects of the SASP within the TME [

42,

43].

Currently, the two most researched senolytics are the combination of dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with quercetin, a naturally occurring flavonoid (D+Q) [

44], and fisetin, another flavonoid found in various fruits and vegetables [

45], both of which are undergoing multiple clinical trials focused on age-related diseases [

37].

Lastly, RNA-based therapies (mRNA, siRNA, miRNA) can modulate senescence pathways with unprecedented specificity, representing a frontier in both oncology and regenerative medicine. The prospects of utilizing mRNA, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and microRNA (miRNA)-based therapies to directly target senescence pathways in cancer cells or the surrounding tumor microenvironment represent a significant area for future exploration [

46]. The prospect of combining advanced immunotherapeutic modalities with nucleic acid-based therapies to directly modulate senescence pathways in cancer cells or the surrounding tumor microenvironment represents a significant area for future exploration, aiming to improve patient prognosis and overall survival [

47].

5. Targeting Senescence: Therapeutic Agents and Approaches

Ultimately, the objective of targeting senescence is to induce tumor regression, mitigate age-associated vulnerabilities, and promote tissue homeostasis and regeneration, resulting in enhanced overall survival and improved patient outcomes [

32]. For instance, dasatinib, a small-molecule inhibitor that targets multiple tyrosine kinases, was initially developed as a second-generation inhibitor of BCR-ABL for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). It exhibits senolytic activity, which is believed to result from its ability to inhibit specific kinases essential for the survival of SnCs. This primary action, combined with quercetin's modulation of anti-apoptotic pathways and broader signaling networks, may converge to induce cell death more effectively in SnCs [

48]. The combination of D+Q warrants further investigation in humans in clinical trials.

On the other hand, senomorphic therapy targets SnCs by suppressing the harmful effects of the SASP without directly causing the death of these cells [

49]. Metformin, for instance, alters key metabolic and signaling pathways associated with aging by activating the 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, a key regulator of cellular energy balance, and inhibits the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, a central regulator of cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and autophagy. By modulating AMPK and mTOR, metformin can help reduce cellular damage caused by oxidative stress and promote cellular health [

50]. Dampening oxidative stress and inflammation can reduce the SASP and the underlying chronic inflammation, as evidenced by its therapeutic applications in type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases [

51]. Ruxolitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinases (JAKs), a family of intracellular enzymes that play a crucial role in cytokine signaling and inflammatory responses, effectively reduces the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, a significant component of the SASP. Its therapeutic efficacy in myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera, conditions marked by excessive inflammation and cytokine dysregulation, underscores its ability to modulate these pathways [

52]. Rapamycin, similarly, influences cellular aging and inflammation by directly inhibiting the mechanistic target of the mTOR pathway [

53], as described earlier [

51]. By suppressing mTOR signaling, rapamycin promotes cellular repair mechanisms, such as autophagy, which clears damaged cellular components, and can reduce the production of SASP factors. This modulation of mTOR can lead to decreased cellular senescence and inflammation, potentially contributing to an extended health span and offering therapeutic avenues for age-related conditions, as suggested by preclinical studies [

54]. Its applications in transplant immunosuppression and certain cancers highlight its capacity to modulate fundamental cellular processes [

55].

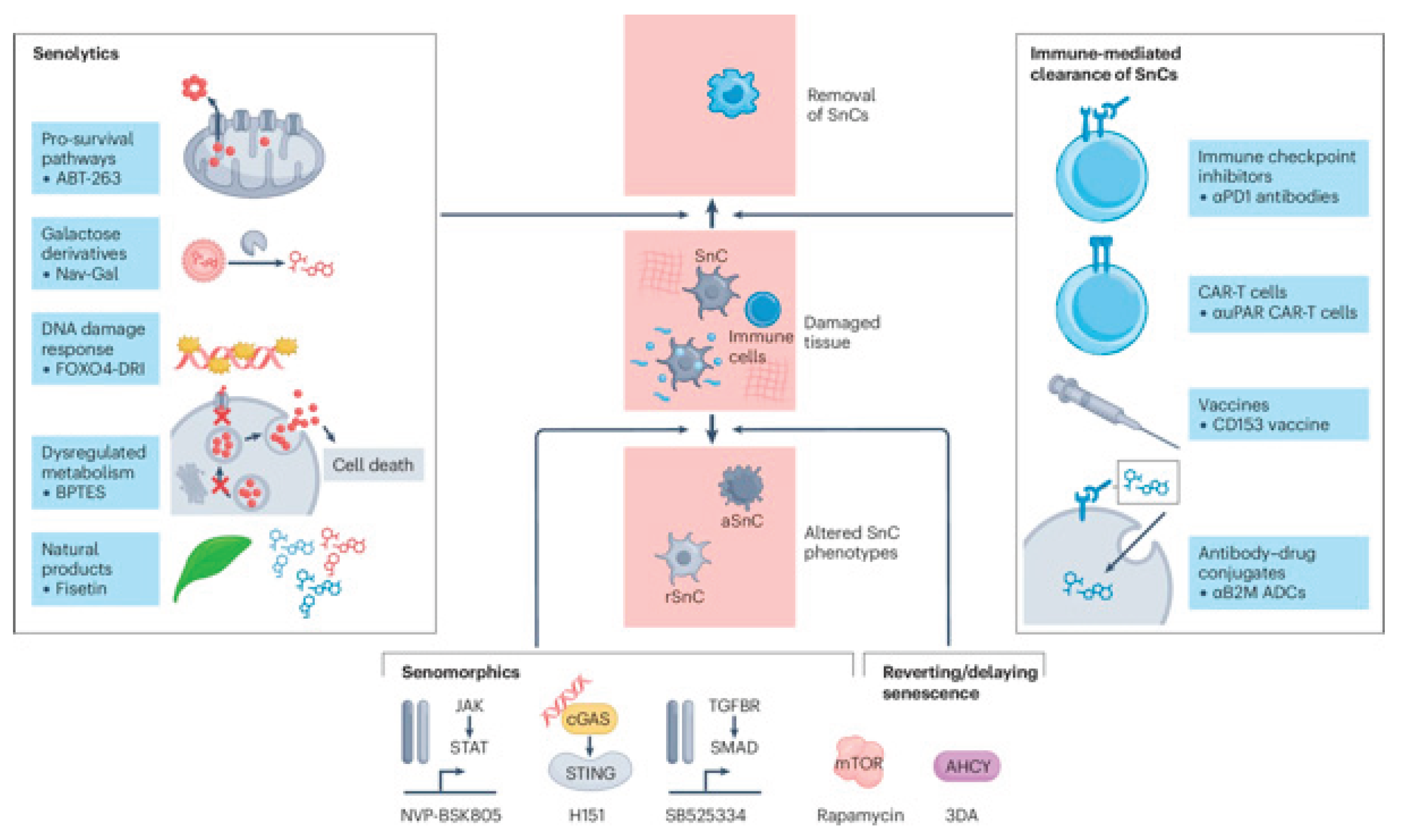

Ongoing research initiatives focus on identifying more specific and safer senolytics and senomorphics, developing biomarkers for monitoring the burden of SnCs, and designing clinical trials to validate these strategies (

Figure 2) [

56,

57]. The potential for personalized medicine, which involves tailoring senescence-modulating therapies to an individual's unique SnC profile and disease context, represents a significant area for future exploration [

56].

6. Discussion

This synthesis positions senescent cell modulation as a unifying therapeutic paradigm across anti-aging, regenerative, and oncologic fields. The convergence among these disciplines arises from their shared goal: eliminating or reprogramming the persistent senescent cell. Although SASP modulation remains valuable, the central focus now lies in identifying and clearing SnCs through context-specific biomarkers and targeted agents.

A critical challenge for the future of senotherapeutics, and a central reason the process is recognized as dynamic and multifaceted, is the heterogeneity and precise definition of the SnC phenotype. The search for a universal SnC marker is confounded by the fact that the constellation of markers varies widely based on the inducing stressor (e.g., replicative, oncogene-induced, or TIS), the specific organ or tissue type, and the cell's differentiation stage. While markers like SA-β-gal activity, upregulation of p16 and p21, and loss of Lamin B1 are commonly used, their presence is not uniform across all SnCs, particularly in vivo. This variability implies that a senolytic effective against a G1-arrested fibroblast may not eliminate a G2-arrested macrophage, underscoring the necessity for complex, context-specific constellations of markers [

58]. Recent advances, such as those by the NIH SenNet Consortium, are directly addressing this challenge through high-resolution, multi-omic approaches and standardization efforts that move beyond single-marker reliance [

59]. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and machine learning–driven analysis of senescence gene signatures (e.g., SenMayo, SenSig) have revealed transcriptional diversity and SASP variability across tissues, capturing entire molecular phenotypes missed by traditional low-plex panels. These methods correlate key hallmarks—cell cycle arrest markers (CDKN2A/p16, CDKN1A/p21), persistent DNA damage response (γH2AX foci), nuclear changes (LMNB1 loss, HMGB1 release), and SASP diversity (IL-6, SERPINE1)—with differential susceptibility to senolytic drugs.

The emerging consensus now supports a multi-marker approach to identify senescent cells in vivo reliably. This includes primary indicators of cell cycle arrest combined with at least two auxiliary markers reflecting SASP activity, metabolic reprogramming, or chromatin remodeling. Such robust identification is essential as the field transitions toward advanced therapies. A prime example is the development of senolytic CAR-T cells that target uPAR, a senescence-associated surface protein. These living-cell therapies achieve durable and prophylactic clearance of uPAR-positive senescent cells, yielding long-term improvements in metabolic fitness and physical performance in preclinical models—outperforming small-molecule senolytics that require repeated administration [

60].

From a translational perspective, combination therapies illustrate the field’s potential. For example, sequential treatment using chemotherapy to induce senescence followed by a senolytic to clear residual SnCs could yield more durable responses. Similarly, pairing immunotherapies with senomorphics may enhance anti-tumor immunity by mitigating SASP-induced immunosuppression. The integration of nucleic acid-based therapeutics offers another avenue for precise modulation of senescence pathways.

The application of nucleic acid-based therapeutics, such as mRNA and siRNA, further enriches this conceptual framework. These technologies offer a high degree of specificity and can be engineered to target the molecular machinery of SnCs or to deliver agents that modulate the SASP. For example, siRNA could be used to silence key SASP genes, while mRNA could be used to express proteins that promote senolytic activity. This level of precision could help overcome the challenges associated with the heterogeneity of SnC populations and their diverse SASP profiles.

Despite the observed convergence in therapeutic strategies—such as the use of classical anti-apoptotic agents (e.g., targeting the BCL-2 family of proteins) as senolytics—it is crucial to recognize that the underlying survival mechanisms in established tumor cells and SnCs are fundamentally distinct. Our framework, however, proposes that the identification of these shared molecular vulnerabilities, even if derived from different pathways, provides a valuable platform for translational research, specifically by addressing the pro-tumorigenic microenvironment created by the SASP. The precise identification and characterization of SnCs across different tissues and disease states require advanced multi-omic approaches.

Moreover, the long-term safety and systemic effects of senotherapeutics in humans need rigorous clinical validation. The potential for these agents to disrupt beneficial, transient senescence—such as that involved in wound healing—must be carefully considered. Nonetheless, the unified conceptual framework presented in this review provides a roadmap for future research.

As the field advances, a multidisciplinary perspective is crucial for bridging the gap between fundamental biological discoveries and their clinical applications. Translating laboratory findings into effective therapeutic regimens will require rigorous preclinical validation, thoughtful clinical trial design, and robust biomarker development to monitor both efficacy and safety. Moreover, the integration of emerging technologies—such as high-throughput screening, single-cell analytics, and advanced computational modeling—holds promise for accelerating the identification of novel senescence regulators and optimizing patient-specific interventions. Ethical considerations, including the long-term consequences of eliminating or altering the fate of SnCs, must also be addressed to ensure responsible translational progress.

7. Conclusions

The convergence of anti-aging medicine, aesthetics, and cancer research around the central theme of senescence modulation highlights the idea that targeting cellular senescence offers a comprehensive approach to addressing age-related decline, enhancing regenerative processes, and improving cancer treatment outcomes. The insights presented in this commentary lay the groundwork for a more integrated and biologically informed approach to addressing some of the most pressing challenges in human health. By shifting focus from SASP suppression to the identification and clearance of SnCs, these disciplines share a mechanistic foundation that enables cross-disciplinary innovation. Key areas for future research include the identification of more specific and safer senolytics and senomorphics, the development of biomarkers to track SnC burden, and the design of clinical trials to validate the efficacy of these strategies in various human diseases and conditions. The potential for personalized medicine approaches that tailor senescence-modulating therapies based on an individual's specific SnC profile and disease context is a significant point for future exploration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, and project administration, SJK. SJK has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dennis Malvin Hernandez Malgapo of EW Villa Medica Philippines and St. Luke’s Medical Center – College of Medicine for his editorial support. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used Gemini for the purposes of searching and integrating information. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3DA |

3-deazaadenosine |

| ADCs |

Antibody-drug conjugates |

| AHCY |

S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase |

| AMPK |

5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| aSnc |

Activated senescent cell |

| BAX |

Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| BCL-2 |

B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BCL-xL |

B-cell lymphoma-extra large |

| CAR |

Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CD153 vaccine |

Cluster of Differentiation 153 vaccine |

| CDK |

Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| cGAS |

Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| CML |

Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| D+Q |

Dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with quercetin, a naturally occurring flavonoid |

| DDR |

DNA damage response |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| E2F |

E2 promoter-binding factor |

| ER |

Endoplasmic reticulum |

| FAP-alpha |

Fibroblast Activation Protein-alpha |

| HNSCC |

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| IIS |

Inflammation-induced Senescence |

ICI

JAKs |

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Janus kinases |

| mAbs |

Monoclonal antibodies |

MCL

MIDAS |

Mantle cell lymphoma

Mitochondria-induced Senescence |

| miMOMP |

Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization |

| miRNA |

MicroRNA |

| mRNA |

Messenger RNA |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal stem cells |

| mTOR |

Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NSCLC |

Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OIS |

Oncogene-induced Senescence |

| PDRN |

Polydeoxyribonucleotide |

| PN |

Polynucleotide |

| Rb |

Retinoblastoma protein |

| RS |

Replicative senescence |

| rSnC |

Resident senescent cell |

| SA-β-gal |

Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase |

| SAHF |

Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci |

SAPS

SASP |

Senescence-associated pro-survival pathways

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| siRNA |

Small interfering RNA |

| SMAD |

Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog |

| SnC |

Senescent cell |

| STAT |

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| STING |

Stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| TGFBR |

Transforming growth factor beta receptor |

| TIS |

Therapy-induced Senescence |

TISnt

uPAR |

Therapy-induced Senescent Cells

Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor |

| αB2M ADCs |

Anti-beta-2-microglobulin Antibody-Drug Conjugates |

| αPD1 antibodies |

Anti-Programmed Death-1 antibodies |

| αuPAR CAR-T cells |

Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells |

References

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J. H.; Demaria, M. The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024, 25, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Z.; Yeo, H. L.; Wong, S. W.; Zhao, Y. Cellular senescence: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.; Gil, J. Senescence and aging: Causes, consequences, and therapeutic avenues. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C. A.; Wang, B.; Demaria, M. Senescence and cancer - role and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freund, A.; Patil, C. K.; Campisi, J. p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Embo j 2011, 30, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chien, Y.; Scuoppo, C.; Wang, X.; Fang, X.; Balgley, B.; Bolden, J. E.; Premsrirut, P.; Luo, W.; Chicas, A.; Lee, C. S.; et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Vredeveld, L. C.; Douma, S.; van Doorn, R.; Desmet, C. J.; Aarden, L. A.; Mooi, W. J.; Peeper, D. S. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 2008, 133, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Xu, C.; Mo, D. Identification and mechanistic insights of cell senescence-related genes in psoriasis. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, P.; Carmi, Y.; Cohen, I. Biologics for targeting inflammatory cytokines, clinical uses, and limitations. Int J Cell Biol 2016, 2016, 9259646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, H.; Gerjol, B. P.; Hahn, K.; von Gudenberg, R. W.; Knoedler, L.; Stallcup, K.; Emmert, M. Y.; Buhl, T.; Wyles, S. P.; Tchkonia, T.; et al. Senescence as a molecular target in skin aging and disease. Ageing Research Reviews 2025, 105, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R. S.; Bin Dayel, S.; Abahussein, O.; El-Sherbiny, A. A. Influences on Skin and Intrinsic Aging: Biological, Environmental, and Therapeutic Insights. J Cosmet Dermatol 2025, 24, e16688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, J.; Feng, J.; Cheng, H. Cellular Senescence and Anti-Aging Strategies in Aesthetic Medicine: A Bibliometric Analysis and Brief Review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2024, 17, 2243–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, A.; Accardi, G.; Aiello, A.; Caruso, C.; Galimberti, D.; Candore, G. Senotherapeutics to Counteract Senescent Cells Are Prominent Topics in the Context of Anti-Ageing Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, T.; Lee, X. E.; Ng, P. Y.; Lee, Y.; Dreesen, O. The role of cellular senescence in skin aging and age-related skin pathologies. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1297637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, L.; Ramponi, V.; Gupta, K.; Stevenson, T.; Mathew, A. B.; Barinda, A. J.; Herbstein, F.; Morsli, S. Emerging insights in senescence: pathways from preclinical models to therapeutic innovations. npj Aging 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E. L.; Pitcher, L. E.; Niedernhofer, L. J.; Robbins, P. D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Development of new approaches for skin care. Plast Reconstr Surg 2022, 150, 12s–19s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueangarun, S.; Visutjindaporn, P.; Parcharoen, Y.; Jamparuang, P.; Tempark, T. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of United States Food and Drug Administration-approved, home-use, low-level light/laser therapy devices for pattern hair loss: device design and technology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2021, 14, E64–e75. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari Beigvand, H.; Razzaghi, M.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Safari, S.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Mansouri, V.; Heidari, M. H. Assessment of laser effects on skin rejuvenation. J Lasers Med Sci 2020, 11, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbiyi, T.; Othman, S.; Familusi, O.; Calvert, C.; Card, E. B.; Percec, I. Better results in facial rejuvenation with fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2020, 8, e2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampridou, S.; Bassett, S.; Cavallini, M.; Christopoulos, G. The effectiveness of polynucleotides in esthetic medicine: A systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2025, 24, e16721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Wang, G.; Zhou, F.; Gong, L.; Zhang, J.; Qi, L.; Cui, H. Polydeoxyribonucleotide: A promising skin anti-aging agent. Chinese Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2022, 4, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, M. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretome promotes skin regeneration and rejuvenation: From mechanism to therapeutics. Cell Proliferation 2024, 57, e13586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alencar-Silva, T.; Barcelos, S. M.; Silva-Carvalho, A.; Sousa, M.; Rezende, T. M. B.; Pogue, R.; Saldanha-Araújo, F.; Franco, O. L.; Boroni, M.; Zonari, A.; et al. Senotherapeutic Peptide 14 Suppresses Th1 and M1 Human T Cell and Monocyte Subsets In Vitro. Cells 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L. E.; Prahalad, V.; Niedernhofer, L. J.; Robbins, P. D. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. Febs j 2023, 290, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, K.; Herbet, M.; Murias, M.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. Senolytics: charting a new course or enhancing existing anti-tumor therapies? Cellular Oncology 2025, 48, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudlova, N.; De Sanctis, J. B.; Hajduch, M. Cellular Senescence: Molecular Targets, Biomarkers, and Senolytic Drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongelli, A.; Atlante, S.; Barbi, V.; Bachetti, T.; Martelli, F.; Farsetti, A.; Gaetano, C. Treating Senescence like Cancer: Novel Perspectives in Senotherapy of Chronic Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Sun, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Shi, X.; Zhou, H. Persistent accumulation of therapy-induced senescent cells: an obstacle to long-term cancer treatment efficacy. International Journal of Oral Science 2025, 17, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piskorz, W. M.; Cechowska-Pasko, M. Senescence of Tumor Cells in Anticancer Therapy-Beneficial and Detrimental Effects. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imawari, Y.; Nakanishi, M. Senescence and senolysis in cancer: The latest findings. Cancer Sci 2024, 115, 2107–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajkowski, K.; Herbet, M.; Murias, M.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. Senolytics: charting a new course or enhancing existing anti-tumor therapies? Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2025, 48, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battram, A. M.; Bachiller, M.; Martín-Antonio, B. Senescence in the Development and Response to Cancer with Immunotherapy: A Double-Edged Sword. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S. M. A.; Hosseini-Fard, S. R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O'Byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr Oncol 2022, 29, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bo, M.; Gambirasi, M.; Vruzhaj, I.; Cecchin, E.; Pishdadian, A.; Toffoli, G.; Safa, A. Targeting Aging Hallmarks with Monoclonal Antibodies: A New Era in Cancer Immunotherapy and Geriatric Medicine. In International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2025; Vol. 26.

- Zingoni, A.; Antonangeli, F.; Sozzani, S.; Santoni, A.; Cippitelli, M.; Soriani, A. The senescence journey in cancer immunoediting. Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L. E.; Yousefzadeh, M. J.; Niedernhofer, L. J.; Robbins, P. D.; Zhu, Y. Cellular senescence: a key therapeutic target in aging and diseases. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, K.; Dai, Z. Targeting cytokine and chemokine signaling pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J. C.; Waselenko, J. K.; Maneatis, T. J.; Murphy, T.; Ward, F. T.; Monahan, B. P.; Sipe, M. A.; Donegan, S.; White, C. A. Rituximab therapy in hematologic malignancy patients with circulating blood tumor cells: association with increased infusion-related side effects and rapid blood tumor clearance. J Clin Oncol 1999, 17, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Blay, J. Y.; Pavlakis, N.; Yoshino, T.; Bruix, J. Evolving role of regorafenib for the treatment of advanced cancers. Cancer Treat Rev 2020, 86, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; DiPersio, J. F. ReCARving the future: bridging CAR T-cell therapy gaps with synthetic biology, engineering, and economic insights. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1432799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, R.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.-s.; Sun, C.; Zhuang, J. Immunoregulatory mechanisms in the aging microenvironment: Targeting the senescence-associated secretory phenotype for cancer immunotherapy. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meguro, S.; Makabe, S.; Yaginuma, K.; Onagi, A.; Tanji, R.; Matsuoka, K.; Hoshi, S.; Koguchi, T.; Kayama, E.; Hata, J.; et al. Targeting Senescence in Oncology: An Emerging Therapeutic Avenue for Cancer. In Current Oncology, 2025; Vol. 32.

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A. C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A. K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G. B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefzadeh, M. J.; Zhu, Y.; McGowan, S. J.; Angelini, L.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Xu, M.; Ling, Y. Y.; Melos, K. I.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C. L.; et al. Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, W.; Khalifeh, M.; Koot, M.; Palacio-Castañeda, V.; van Oostrum, J.; Ansems, M.; Verdurmen, W. P. R.; Brock, R. RNA-based logic for selective protein expression in senescent cells. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2024, 174, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratti, M.; Lampis, A.; Ghidini, M.; Salati, M.; Mirchev, M. B.; Valeri, N.; Hahne, J. C. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) as New Tools for Cancer Therapy: First Steps from Bench to Bedside. Target Oncol 2020, 15, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A. C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A. K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G. B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Gao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Luan, C.; Hua, M.; Liu, W.; Gong, W.; et al. Targeted apoptosis of senescent cells by valproic acid alleviates therapy-induced cellular senescence and lung aging. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, H. Cellular senescence in health, disease, and lens aging. In Pharmaceuticals, 2025; Vol. 18.

- Khansari, N.; Shakiba, Y.; Mahmoudi, M. Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2009, 3, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostojic, A.; Vrhovac, R.; Verstovsek, S. Ruxolitinib: a new JAK1/2 inhibitor that offers promising options for treatment of myelofibrosis. Future Oncol 2011, 7, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, D. W. Inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)-rapamycin and beyond. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M. V. Rapamycin extends life- and health span because it slows aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2013, 5, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroja-Mazo, A.; Revilla-Nuin, B.; Ramírez, P.; Pons, J. A. Immunosuppressive potency of mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors in solid-organ transplantation. World J Transplant 2016, 6, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T. E.; Zhou, Z. Senescent cells as a target for anti-aging interventions: From senolytics to immune therapies. J Transl Int Med 2025, 13, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, D.; Duran, I.; Gil, J. Senescence as a therapeutic target in cancer and age-related diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025, 24, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Carlos Acosta, J.; Adams, P. D.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F.; Baker, D. J.; Bishop, C. L.; Chandra, T.; Collado, M.; Gil, J.; Gorgoulis, V.; et al. Guidelines for minimal information on cellular senescence experimentation in vivo. Cell 2024, 187, 4150–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadevara, V.; Hudgins, A. D.; Rajesh, A.; Pappalardo, A.; Karpova, A.; Dey, A. K.; Hertzel, A.; Agudelo, A.; Rocha, A.; Soygur, B.; et al. SenNet recommendations for detecting senescent cells in different tissues. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2024, 25, 1001–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amor, C.; Fernández-Maestre, I.; Chowdhury, S.; Ho, Y.-J.; Nadella, S.; Graham, C.; Carrasco, S. E.; Nnuji-John, E.; Feucht, J.; Hinterleitner, C.; et al. Prophylactic and long-lasting efficacy of senolytic CAR T cells against age-related metabolic dysfunction. Nature Aging 2024, 4, 336–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).