1. Introduction: Bridging Anti-Aging, Regeneration, and Oncology Through Senescence

The science of senescence modulation is experiencing significant growth as a treatment target, primarily driven by an increasing interest in the interrelated applications across various medical disciplines [

1]. This review aims to investigate this concept, emphasizing the importance of understanding cellular senescence as a fundamental mechanism in the context of longevity, tissue regeneration, and cancer therapy research. The convergence of these seemingly unrelated fields through the lens of senescence modulation highlights a shift in the approach to longevity, aesthetic interventions, and oncological treatments.

2. Results

This review synthesizes information from over 50 recent publications to provide a comprehensive review of senescence modulation as a uniform treatment target.

2.1. The Fundamental Role of Senescence: A Shared Biological Mechanism

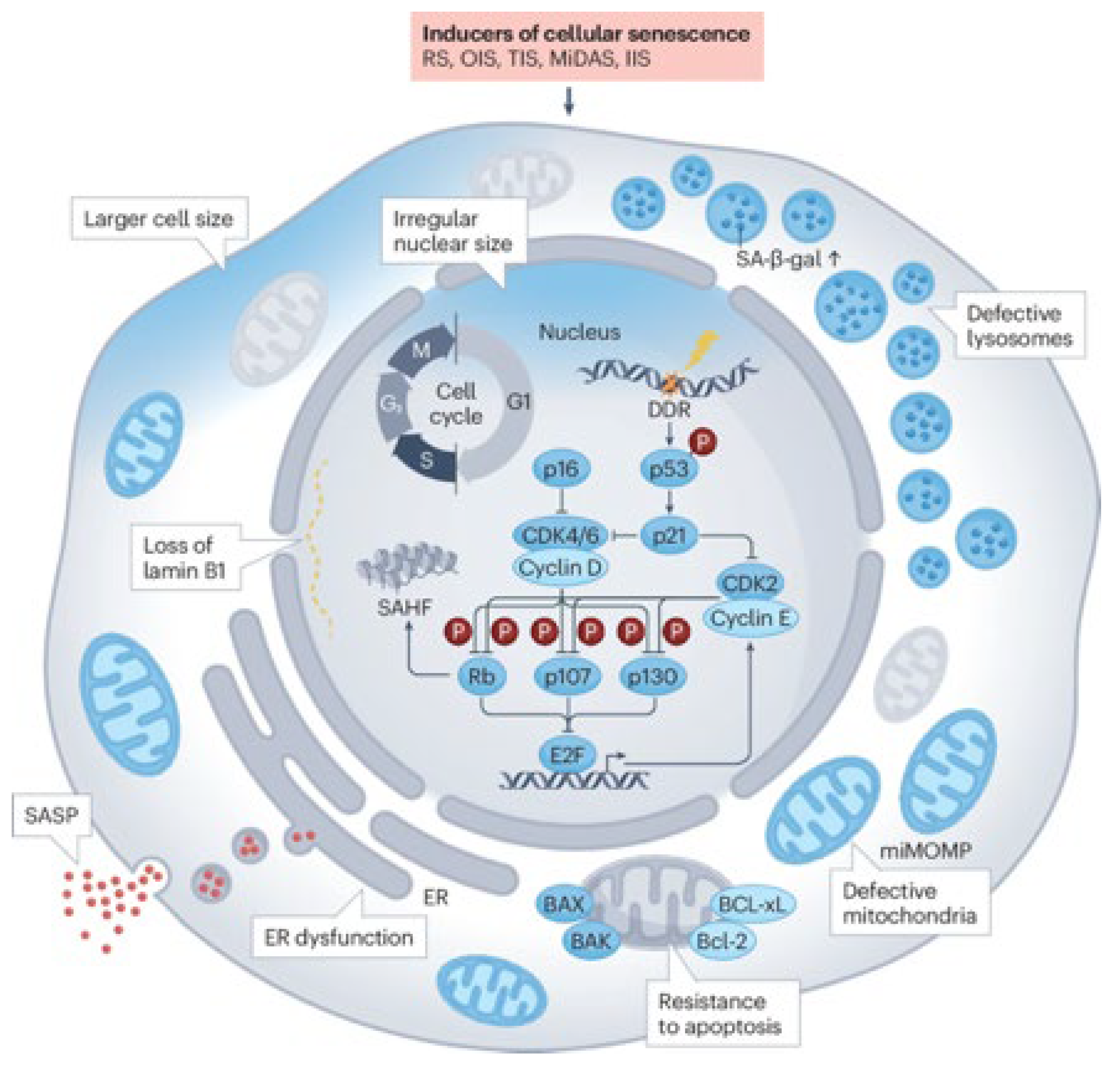

Cellular senescence is a fundamental biological process characterized by the irreversible arrest of the cell cycle, altered metabolism, and the secretion of a complex array of pro-inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and proteases, collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) (

Figure 1) [

2,

3]. While initially recognized as a tumor suppressor mechanism, the accumulation of senescent cells over time significantly contributes to tissue dysfunction, chronic inflammation (known as "inflammaging”), and the development of an age-related state [

4]. Likewise, as senescence acts as a crucial anti-tumor mechanism, researchers have identified specific molecular abnormalities in cancer cells to develop targeted therapies that selectively attack these vulnerabilities while minimizing harm to healthy cells [

5]. These treatment targets can include proteins, enzymes, or genes that play a crucial role in the growth and survival of cancer [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Figure 1.

Senescent Cell Characteristics and Classification [

2]

. Legend: RS: Replicative Senescence; OIS: Oncogene-induced Senescence; TIS: Therapy-induced Senescence; MIDAS: Mitochondria-induced Senescence; IIS: Inflammation-induced Senescence; SA-β-gal: Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase; DDR: DNA Damage Response; CDK: Cyclin-Dependent Kinase; Rb: Retinoblastoma protein; SAHF: Senescence-Associated Heterochromatin Foci; E2F: E2 promoter-binding factor; SASP: Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype; ER: Endoplasmic Reticulum; BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; BCL-xL: B-cell lymphoma-extra-large; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; miMOMP: mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization

Figure 1.

Senescent Cell Characteristics and Classification [

2]

. Legend: RS: Replicative Senescence; OIS: Oncogene-induced Senescence; TIS: Therapy-induced Senescence; MIDAS: Mitochondria-induced Senescence; IIS: Inflammation-induced Senescence; SA-β-gal: Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase; DDR: DNA Damage Response; CDK: Cyclin-Dependent Kinase; Rb: Retinoblastoma protein; SAHF: Senescence-Associated Heterochromatin Foci; E2F: E2 promoter-binding factor; SASP: Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype; ER: Endoplasmic Reticulum; BAX: Bcl-2-associated X protein; BCL-xL: B-cell lymphoma-extra-large; Bcl-2: B-cell lymphoma 2; miMOMP: mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization

2.1.1. Senescence Modulation in Dermatology, Anti-Aging and Regenerative Aesthetics: A Different Approach to Rejuvenation

Studies have identified key senescence-related genes in dermatologic conditions such as psoriasis [

11]. Biologic agents, such as adalimumab (a TNF-α inhibitor), secukinumab (an IL-17A inhibitor), and ustekinumab (an IL-12/23 inhibitor), are effective in targeting specific cytokines. By neutralizing these pro-inflammatory cytokines, these monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) disrupt the inflammatory cascade that drives the characteristic skin lesions of psoriasis, leading to clinical remission and improved patient quality of life [

12]. The mechanism of action is linked to their anti-inflammatory properties, which can indirectly modulate the chronic, low-grade inflammation associated with SASP [

13]. Also, targeting senescent cells holds significant promise in anti-aging and regenerative aesthetics. The accumulation of these cells in the skin contributes to visible signs of aging, including wrinkles, loss of elasticity, and impaired wound healing [

14]. Beyond cosmetic improvements, these targets also appear promising in chronic wound care through the clearance of senescent cells that impede tissue repair and regeneration, offering significant advancements in regenerative medicine for dermatological applications [

15].

Strategies to eliminate senescent cells (senolysis) or suppress the detrimental SASP (senomorphics) are presented as potential avenues for rejuvenation and tissue repair. For instance, some interventions in preclinical or early clinical research demonstrate the efficacy of these approaches in improving skin health, promoting collagen production, and enhancing tissue regeneration [

16,

17,

18]. The potential to reverse age-related aesthetic changes by directly addressing cellular senescence, which offers a novel and biologically grounded approach compared to traditional cosmetic procedures [

18]. Conventional approaches to addressing visible signs of aging, such as skin wrinkling and hair loss, often involve interventions like laser therapies [

19,

20], dermal fillers [

21], and polynucleotide (PN) or polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) injections, which aim to stimulate collagen production and tissue regeneration [

22,

23]. More advanced strategies include the use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [

24] and various peptides, such as Pep 14, to promote cellular repair and revitalization [

25]. While these methods offer variable levels of aesthetic improvement, targeting cellular senescence directly with senolytics or senomorphics presents a novel and biologically grounded approach that could potentially enhance the longevity and efficacy of these traditional procedures by addressing the root cause of age-related tissue dysfunction, offering a promise for more profound and sustained rejuvenation [

26].

2.1.2. Senescence Modulation in Oncology: A Multi-level Therapeutic Target

Senescence modulation is relevant in cancer therapy, as senescent cells can create an immunosuppressive microenvironment that dampens the anti-tumor immune response, an effect that immunotherapeutic agents aim to overcome [

27]. For instance, chemotherapeutic agents induce senescence in cancer cells, and there is potential for combining these agents with senolytics or senomorphics to enhance treatment efficacy or reduce adverse effects [

28]. Similarly, in mAb therapy, research has shown how senescence pathways may influence the response of cancer cells to antibody-mediated cell death or immune modulation [

29]. These agents can efficiently target and diminish senescence pathways by specifically removing senescent cells or disrupting their signaling molecules. This can be accomplished through several mechanisms, such as antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that transport cytotoxic drugs to senescent cells, or neutralizing antibodies that inhibit the release of components associated with the SASP [

30]. Agents like rituximab, adalimumab, pembrolizumab, and siltuximab demonstrate efficacy across various malignancies. For instance, pembrolizumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, is widely used in solid tumors such as melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [

31]. At the same time, rituximab is a cornerstone in the treatment of hematological malignancies, such as lymphoma and leukemia [

32]. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab target the PD-1 (Programmed Death-1) protein on T-cells, allowing them to recognize and attack melanoma cells. Siltuximab has been employed for Castleman's disease, and adalimumab, primarily used for inflammatory bowel disease and certain autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, underscores the broader implications of modulating inflammatory pathways, which are often exacerbated by senescent cells [

33]. Regorafenib, a multi-kinase inhibitor, is used in the treatment of various solid tumors, including colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors, highlighting the diverse mechanisms by which cancer therapies can interact with cellular pathways, including those related to senescence [

34].

Currently, the two most researched senolytics are the combination of dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with quercetin, a naturally occurring flavonoid (D+Q) [

35], and fisetin, another flavonoid found in various fruits and vegetables [

36], both of which are undergoing multiple clinical trials focused on age-related diseases [

30]. Another therapeutic agent that targets senescence is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, which has transformed the treatment of hematologic malignancies, including lymphomas, leukemias, and myeloma, and yielded notable remission rates in previously refractory conditions [

37]. Genetically engineered T-cells may facilitate the recognition and attack of cancer cells. Emerging research indicates that CAR-T cells can be engineered to specifically target senescent cells, with targets such as FAP-alpha (Fibroblast Activation Protein-alpha) and uPAR (urokinase plasminogen activator receptor) showing potential. By targeting these markers on senescent cells, CAR-T therapy could not only enhance the anti-tumor immune response but also mitigate the pro-tumorigenic effects of the SASP within the tumor microenvironment in both hematological malignancies and solid tumors, such as ovarian and lung cancer [

38]. Lastly, the prospects of utilizing mRNA, small interfering RNA (siRNA), and microRNA (miRNA)-based therapies to directly target senescence pathways in cancer cells or the surrounding tumor microenvironment represent a significant area for future exploration [

39]. The prospect of combining advanced immunotherapeutic modalities with nucleic acid-based therapies to directly modulate senescence pathways in cancer cells or the surrounding tumor microenvironment represents a significant area for future exploration, aiming to improve patient prognosis and overall survival [

40].

2.2. Targeting Senescence: Therapeutic Agents and Approaches

Ultimately, the objective of targeting senescence is to induce tumor regression, mitigate age-associated vulnerabilities, and promote tissue homeostasis and regeneration, resulting in enhanced overall survival and improved patient outcomes [

41]. For instance, dasatinib, a small-molecule inhibitor that targets multiple tyrosine kinases, was initially developed as a second-generation inhibitor of BCR-ABL for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). It exhibits senolytic activity, which is believed to result from its ability to inhibit specific kinases essential for the survival of senescent cells. This primary action, combined with quercetin's modulation of anti-apoptotic pathways and broader signaling networks, may converge to induce cell death more effectively in senescent cells [

42]. The combination of D+Q warrants further investigation in humans in clinical trials.

On the other hand, senomorphic therapy targets senescent cells by suppressing the harmful effects of the SASP without directly causing the death of these cells [

43]. Metformin, for instance, alters key metabolic and signaling pathways associated with aging by activating the 5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, a key regulator of cellular energy balance, and inhibits the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, a central regulator of cell growth, proliferation, metabolism, and autophagy. By modulating AMPK and mTOR, metformin can help reduce cellular damage caused by oxidative stress and promote cellular health [

44]. Dampening oxidative stress and inflammation can reduce the SASP and the underlying chronic inflammation, as evidenced by its therapeutic applications in type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases [

45]. Ruxolitinib, an inhibitor of Janus kinases (JAKs), a family of intracellular enzymes that play a crucial role in cytokine signaling and inflammatory responses, effectively reduces the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, a significant component of the SASP. Its therapeutic efficacy in myelofibrosis and polycythemia vera, conditions marked by excessive inflammation and cytokine dysregulation, underscores its ability to modulate these pathways [

46]. Rapamycin, similarly, influences cellular aging and inflammation by directly inhibiting the mechanistic target of the mTOR pathway [

47], as described earlier [

45]. By suppressing mTOR signaling, rapamycin promotes cellular repair mechanisms, such as autophagy, which clears damaged cellular components, and can reduce the production of SASP factors. This modulation of mTOR can lead to decreased cellular senescence and inflammation, potentially contributing to an extended health span and offering therapeutic avenues for age-related conditions, as suggested by preclinical studies [

48]. Its applications in transplant immunosuppression and certain cancers highlight its capacity to modulate fundamental cellular processes [

49].

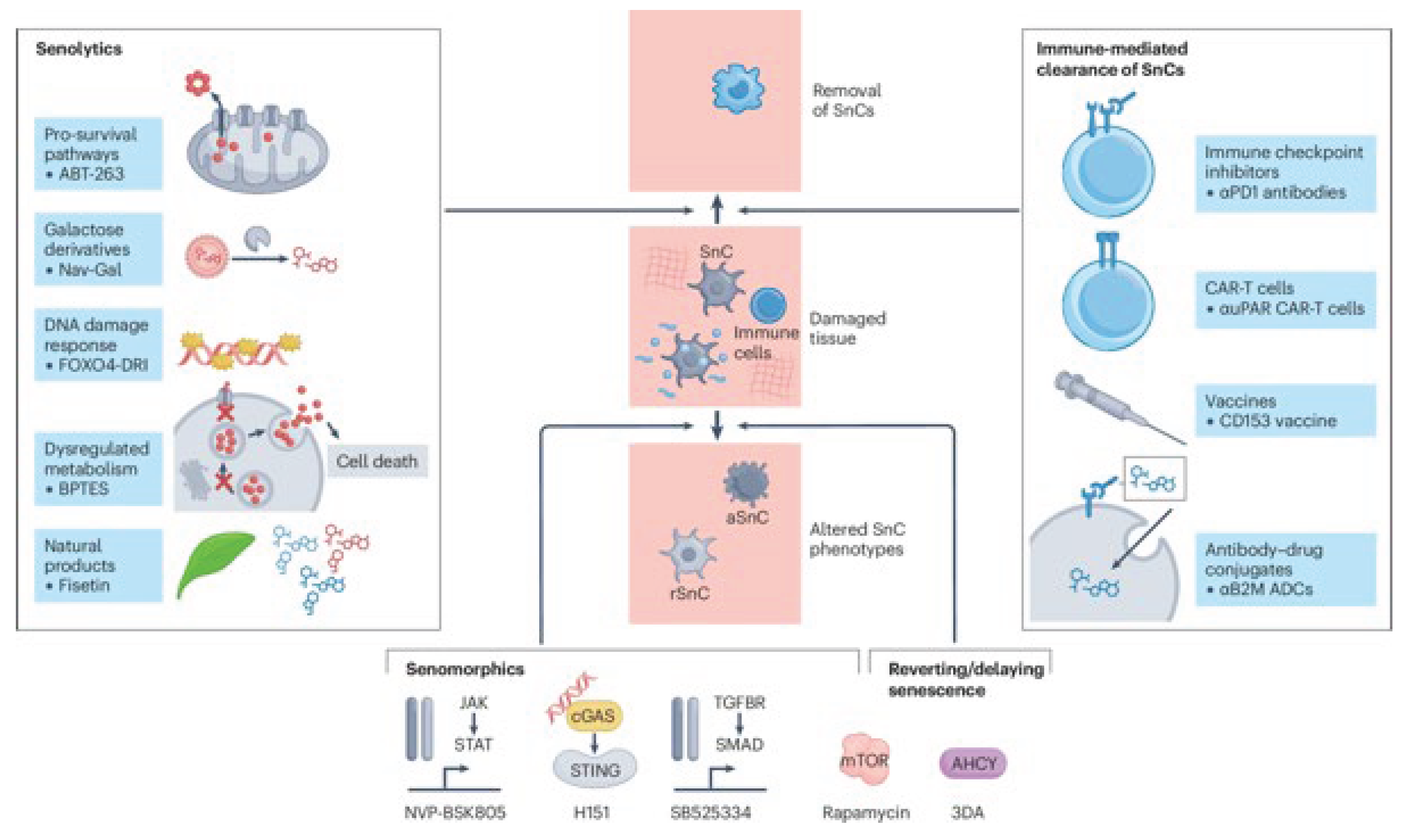

Ongoing research initiatives focus on identifying more specific and safer senolytics and senomorphics, developing biomarkers for monitoring the burden of senescent cells, and designing clinical trials to validate these strategies (

Figure 2)

[50,51]. The potential for personalized medicine, which involves tailoring senescence-modulating therapies to an individual's unique senescent cell profile and disease context, represents a significant area for future exploration [

50].

Figure 2.

Eliminating Senescent Cells: Therapeutic Strategies for Cancer and Age-Related Disease [

51]. Legend: SnC: Senescent Cell; aSnc: Activated Senescent Cell; rSnC: Resident Senescent Cell; αPD1 antibodies: anti-Programmed Death-1 antibodies; CAR-T cells: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells; αuPAR CAR-T cells: urokinase plasminogen activator receptor Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells; CD153 vaccine: Cluster of Differentiation 153 vaccine; αB2M ADCs: anti-beta-2-microglobulin Antibody-Drug Conjugates; JAK: Janus Kinase; STAT: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription; cGAS: cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; STING: Stimulator of Interferon Genes; TGFBR: Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor; SMAD: Small Mothers Against Decapentaplegic Homolog; mTOR: mammalian Target of Rapamycin; AHCY: S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase; 3DA: 3-Deazaadenosine; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid

Figure 2.

Eliminating Senescent Cells: Therapeutic Strategies for Cancer and Age-Related Disease [

51]. Legend: SnC: Senescent Cell; aSnc: Activated Senescent Cell; rSnC: Resident Senescent Cell; αPD1 antibodies: anti-Programmed Death-1 antibodies; CAR-T cells: Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells; αuPAR CAR-T cells: urokinase plasminogen activator receptor Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells; CD153 vaccine: Cluster of Differentiation 153 vaccine; αB2M ADCs: anti-beta-2-microglobulin Antibody-Drug Conjugates; JAK: Janus Kinase; STAT: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription; cGAS: cyclic GMP-AMP synthase; STING: Stimulator of Interferon Genes; TGFBR: Transforming Growth Factor Beta Receptor; SMAD: Small Mothers Against Decapentaplegic Homolog; mTOR: mammalian Target of Rapamycin; AHCY: S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase; 3DA: 3-Deazaadenosine; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid

3. Discussion

The concept of cellular senescence, once primarily understood as a terminal state of cell division arrest, is now recognized as a multifaceted and dynamic biological process with profound implications that transcend the traditional boundaries of anti-aging medicine, regenerative dermatology, and oncology. This review systematically synthesizes the emerging evidence, proposing a unified therapeutic paradigm centered on senescence modulation. This analysis highlights the convergence of strategies from seemingly disparate fields, demonstrating how interventions originally developed for anti-aging and regenerative aesthetics can provide valuable translational insights for potentiating oncological therapies. The key to this convergence lies in the dual and often paradoxical roles of SASP, which can be both a tumor-suppressive and a pro-tumorigenic force.

The SASP is the central mechanistic link that connects the accumulation of senescent cells to systemic dysfunction and disease. In the context of aging and regenerative aesthetics, the chronic presence of senescent cells and their SASP-mediated inflammation contributes directly to tissue degeneration. We have reviewed how this process manifests in visible signs of aging, such as wrinkles, loss of skin elasticity, and impaired wound healing, as well as functional decline in hair follicles and adipose tissue. For example, the persistence of senescent fibroblasts in the dermis compromises the efficacy of aesthetic treatments, such as radiofrequency and laser therapy, by creating a pro-aging microenvironment that hinders optimal tissue repair. Our review suggests that modulating this environment through senotherapeutic approaches—specifically, the use of senolytics to selectively eliminate senescent cells or senomorphics to suppress the detrimental effects of the SASP—could significantly enhance the regenerative outcomes of conventional aesthetic procedures. This synergistic approach transcends mere symptomatic treatment to address the root cause of age-related tissue pathology, promoting a more robust and sustainable state of rejuvenation. The identification of senomorphic peptides like Peptide 14, which modulate key pathways, such as PP2A, to reduce senescence burden, represents a promising direction for future applied science in this area.

The paradigm shifts considerably when we apply this lens to oncology. While acute senescence is a critical tumor-suppressive mechanism, often induced by chemotherapy and radiotherapy, persistent senescent cancer cells and the SASP they produce can become a liability. The SASP's constituents, such as IL-6, IL-8, and MMPs, can paradoxically fuel tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. This dual nature presents a compelling rationale for a two-pronged therapeutic strategy. First, current oncological treatments should aim to induce cellular senescence as a means of initial tumor control. Second, and crucially, these senescent cells must be subsequently cleared or their SASP mitigated to prevent them from promoting tumor recurrence and therapy resistance. This is where the translational potential of senotherapeutics from anti-aging medicine becomes most apparent.

The convergence of these fields opens novel avenues for combination therapies. For instance, the sequential application of a standard-of-care chemotherapeutic agent to induce senescence, followed by a senolytic drug to eliminate the senescent cancer cells, could represent a more potent and comprehensive anti-neoplastic strategy. Similarly, combining immunotherapies such as CAR-T cell therapy or monoclonal antibodies with a senomorphic agent could suppress the immunosuppressive SASP factors, creating a more favorable tumor microenvironment for immune-mediated clearance. The ability of the SASP to recruit immunosuppressive cells, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), underscores the need for such integrated approaches to overcome resistance mechanisms. By modulating the SASP, we can potentially enhance the efficacy of existing immunotherapies and circumvent the "escape" phase of cancer immunoediting.

The application of nucleic acid-based therapeutics, such as mRNA and siRNA, further enriches this conceptual framework. These technologies offer a high degree of specificity and can be engineered to target the molecular machinery of senescent cells or to deliver agents that modulate the SASP. For example, siRNA could be used to silence key SASP genes, while mRNA could be used to express proteins that promote senolytic activity. This level of precision could help overcome the challenges associated with the heterogeneity of senescent cell populations and their diverse SASP profiles.

Despite the promising therapeutic potential, significant challenges remain. The precise identification and characterization of senescent cells across different tissues and disease states require advanced multi-omic approaches. Moreover, the long-term safety and systemic effects of senotherapeutics in humans need rigorous clinical validation. The potential for these agents to disrupt beneficial, transient senescence—such as that involved in wound healing—must be carefully considered. Nonetheless, the unified conceptual framework presented in this review provides a roadmap for future research.

As the field advances, a multidisciplinary perspective is crucial for bridging the gap between fundamental biological discoveries and their clinical applications. Translating laboratory findings into effective therapeutic regimens will require rigorous preclinical validation, thoughtful clinical trial design, and robust biomarker development to monitor both efficacy and safety. Moreover, the integration of emerging technologies—such as high-throughput screening, single-cell analytics, and advanced computational modeling—holds promise for accelerating the identification of novel senescence regulators and optimizing patient-specific interventions. Ethical considerations, including the long-term consequences of eliminating or altering the fate of senescent cells, must also be addressed to ensure responsible translational progress.

4. Materials and Methods

This manuscript is structured as a scientific narrative review. The objective of this methodology was to systematically identify, select, and synthesize relevant literature to provide a comprehensive overview of senescence modulation strategies in anti-aging, regenerative aesthetics, and oncology. No new data were generated for this study.

4.1. Literature Search and Selection

A systematic search of peer-reviewed scientific literature was conducted across several databases, including PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar. The search was performed using a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to ensure a broad and relevant capture of publications. Key search terms included, but were not limited to: "cellular senescence," "senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)," "senolytics," "senomorphics," "anti-aging," "regenerative medicine," "regenerative aesthetics," "oncology," "cancer therapy," "chemotherapy," "immunotherapy," "CAR-T cell therapy," "monoclonal antibodies," "mRNA," and "siRNA." The searches were not restricted by publication date to allow for the inclusion of foundational and recent studies.

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The initial search results were screened based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Publications were included if they were original research articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or high-quality review articles published in English. The core focus was on studies that provided clear mechanistic insights into cellular senescence, its role in the pathophysiology of aging and cancer, and therapeutic strategies aimed at its modulation. Articles were excluded if they were abstracts, conference proceedings, editorials, or did not directly relate to the therapeutic modulation of senescence.

4.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Following the selection process, data from the included publications were extracted and synthesized to form a coherent narrative. The extracted information focused on the following key themes:

The fundamental biological mechanisms of cellular senescence.

The dual roles of the SASP in aging and oncology.

Specific examples of senotherapeutic agents (senolytics and senomorphics).

Applications of senescence modulation in anti-aging and regenerative aesthetics.

Applications of senescence modulation in various oncology therapy modalities (e.g., chemotherapy, immunotherapy, nucleic acid-based therapies).

Emerging therapeutic targets and future directions.

The synthesis process involved a critical analysis of the extracted data to identify key trends, points of convergence, and knowledge gaps across the different fields. The review aims to present a unified conceptual framework, highlighting the translational potential of these strategies.

5. Conclusions

The convergence of anti-aging medicine, aesthetics, and cancer research around the central theme of senescence modulation highlights the idea that targeting cellular senescence provides a comprehensive approach to addressing age-related decline, enhancing regenerative processes, and improving cancer treatment outcomes. The insights presented in this commentary lay the groundwork for a more integrated and biologically informed approach to addressing some of the most pressing challenges in human health. Key areas for future research include the identification of more specific and safer senolytics and senomorphics, the development of biomarkers to track senescent cell burden, and the design of clinical trials to validate the efficacy of these strategies in various human diseases and conditions. The potential for personalized medicine approaches that tailor senescence-modulating therapies based on an individual's specific senescent cell profile and disease context is a significant point for future exploration.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, supervision, and project administration, SJK. SJK has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the results of this review article are available online and can be found in the cited literature. Also, this review presents an overview of the research outcomes and analysis elaborated in the author's Second Level Master's Degree final thesis, titled "Convergence on Senescence Modulation: An Applied Science Review of Strategies in Anti-Aging, Regenerative Aesthetics, and Oncology Therapy," for the Master of Science (MSc) in Aesthetic and Regenerative Medicine at San Raffaele University of Rome, Italy, organized by Consorzio Humanitas in Rome, Italy.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Dr. Dennis Malvin Hernandez Malgapo of EW Villa Medica Philippines and St. Luke’s Medical Center – College of Medicine for his editorial support. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author used Gemini for the purposes of searching and integrating information. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3DA |

3-deazaadenosine |

| ADCs |

Antibody-drug conjugates |

| AHCY |

S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase |

| AMPK |

5' adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| aSnc |

Activated senescent cell |

| BAX |

Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 |

B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| BCL-xL |

B-cell lymphoma-extra large |

| CAR |

Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CD153 vaccine |

Cluster of Differentiation 153 vaccine |

| CDK |

Cyclin-dependent kinase |

| cGAS |

Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase |

| CML |

Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| D+Q |

Dasatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, with quercetin, a naturally occurring flavonoid |

| DDR |

DNA damage response |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| E2F |

E2 promoter-binding factor |

| ER |

Endoplasmic reticulum |

| FAP-alpha |

Fibroblast Activation Protein-alpha |

| HNSCC |

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| IIS |

Inflammation-induced Senescence |

| JAKs |

Janus kinases |

| mAbs |

Monoclonal antibodies |

| MIDAS |

Mitochondria-induced Senescence |

| miMOMP |

Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization |

| miRNA |

MicroRNA |

| mRNA |

Messenger RNA |

| MSCs |

Mesenchymal stem cells |

| mTOR |

Mechanistic target of rapamycin |

| NSCLC |

Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OIS |

Oncogene-induced Senescence |

| PDRN |

Polydeoxyribonucleotide |

| PN |

Polynucleotide |

| Rb |

Retinoblastoma protein |

| RS |

Replicative senescence |

| rSnC |

Resident senescent cell |

| SA-β-gal |

Senescence-Associated β-galactosidase |

| SAHF |

Senescence-associated heterochromatin foci |

| SASP |

Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| siRNA |

Small interfering RNA |

| SMAD |

Mothers against decapentaplegic homolog |

| SnC |

Senescent cell |

| STAT |

Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| STING |

Stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| TGFBR |

Transforming growth factor beta receptor |

| TIS |

Therapy-induced Senescence |

| uPAR |

Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor |

|

αB2M ADCs |

Anti-beta-2-microglobulin Antibody-Drug Conjugates |

|

αPD1 antibodies |

Anti-Programmed Death-1 antibodies |

|

αuPAR CAR-T cells |

Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells |

References

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. , Aging and aging-related diseases: From molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Han, J.; Elisseeff, J.H.; Demaria, M. , The senescence-associated secretory phenotype and its physiological and pathological implications. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2024, 25, 958–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Yeo, H.L.; Wong, S.W.; Zhao, Y. , Cellular senescence: Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.; Gil, J. , Senescence and aging: Causes, consequences, and therapeutic avenues. J Cell Biol 2018, 217, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, C.A.; Wang, B.; Demaria, M. , Senescence and cancer - role and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2022, 19, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, A.; Patil, C.K.; Campisi, J. , p38MAPK is a novel DNA damage response-independent regulator of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Embo j 2011, 30, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herranz, N.; Gallage, S.; Mellone, M.; Wuestefeld, T.; Klotz, S.; Hanley, C.J.; Raguz, S.; Acosta, J.C.; Innes, A.J.; Banito, A.; et al. mTOR regulates MAPKAPK2 translation to control the senescence-associated secretory phenotype. Nat Cell Biol 2015, 17, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge, R.M.; Sun, Y.; Orjalo, A.V.; Patil, C.K.; Freund, A.; Zhou, L.; Curran, S.C.; Davalos, A.R.; Wilson-Edell, K.A.; Liu, S.; et al. MTOR regulates the pro-tumorigenic senescence-associated secretory phenotype by promoting IL1A translation. Nat Cell Biol 2015, 17, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, Y.; Scuoppo, C.; Wang, X.; Fang, X.; Balgley, B.; Bolden, J.E.; Premsrirut, P.; Luo, W.; Chicas, A.; Lee, C.S.; et al. Control of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype by NF-κB promotes senescence and enhances chemosensitivity. Genes Dev 2011, 25, 2125–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Vredeveld, L.C.; Douma, S.; van Doorn, R.; Desmet, C.J.; Aarden, L.A.; Mooi, W.J.; Peeper, D.S. , Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell 2008, 133, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Xu, C.; Mo, D. , Identification and mechanistic insights of cell senescence-related genes in psoriasis. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, P.; Carmi, Y.; Cohen, I. , Biologics for Targeting Inflammatory Cytokines, Clinical Uses, and Limitations. Int J Cell Biol 2016, 2016, 9259646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thau, H.; Gerjol, B.P.; Hahn, K.; von Gudenberg, R.W.; Knoedler, L.; Stallcup, K.; Emmert, M.Y.; Buhl, T.; Wyles, S.P.; Tchkonia, T.; et al. Senescence as a molecular target in skin aging and disease. Ageing Research Reviews 2025, 105, 102686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, R.S.; Bin Dayel, S.; Abahussein, O.; El-Sherbiny, A.A. , Influences on Skin and Intrinsic Aging: Biological, Environmental, and Therapeutic Insights. J Cosmet Dermatol 2025, 24, e16688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; Wu, J.; Feng, J.; Cheng, H. , Cellular Senescence and Anti-Aging Strategies in Aesthetic Medicine: A Bibliometric Analysis and Brief Review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2024, 17, 2243–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, T.; Lee, X.E.; Ng, P.Y.; Lee, Y.; Dreesen, O. , The role of cellular senescence in skin aging and age-related skin pathologies. Front Physiol 2023, 14, 1297637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, L.; Ramponi, V.; Gupta, K.; Stevenson, T.; Mathew, A.B.; Barinda, A.J.; Herbstein, F.; Morsli, S. , Emerging insights in senescence: Pathways from preclinical models to therapeutic innovations. npj Aging 2024, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, E.L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. , Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Development of new approaches for skin care. Plast Reconstr Surg 2022, 150, 12s–19s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lueangarun, S.; Visutjindaporn, P.; Parcharoen, Y.; Jamparuang, P.; Tempark, T. , A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of United States Food and Drug Administration-approved, home-use, low-level light/laser therapy devices for pattern hair loss: Device design and technology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2021, 14, E64–e75. [Google Scholar]

- Heidari Beigvand, H.; Razzaghi, M.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Safari, S.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Mansouri, V.; Heidari, M.H. , Assessment of laser effects on skin rejuvenation. J Lasers Med Sci 2020, 11, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbiyi, T.; Othman, S.; Familusi, O.; Calvert, C.; Card, E.B.; Percec, I. , Better results in facial rejuvenation with fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2020, 8, e2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampridou, S.; Bassett, S.; Cavallini, M.; Christopoulos, G. , The effectiveness of polynucleotides in esthetic medicine: A systematic review. J Cosmet Dermatol 2025, 24, e16721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Wang, G.; Zhou, F.; Gong, L.; Zhang, J.; Qi, L.; Cui, H. , Polydeoxyribonucleotide: A promising skin anti-aging agent. Chinese Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2022, 4, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, M. , Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretome promotes skin regeneration and rejuvenation: From mechanism to therapeutics. Cell Proliferation 2024, 57, e13586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zonari, A.; Brace, L.E.; Al-Katib, K.; Porto, W.F.; Foyt, D.; Guiang, M.; Cruz, E.A.O.; Marshall, B.; Gentz, M.; Guimarães, G.R.; et al. Senotherapeutic peptide treatment reduces biological age and senescence burden in human skin models. NPJ Aging 2023, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Prahalad, V.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. , Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: Senolytics and senomorphics. Febs j 2023, 290, 1362–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battram, A.M.; Bachiller, M.; Martín-Antonio, B. , Senescence in the Development and Response to Cancer with Immunotherapy: A Double-Edged Sword. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, P.G.; Citrin, D.E.; Hildesheim, J.; Ahmed, M.M.; Venkatachalam, S.; Riscuta, G.; Xi, D.; Zheng, G.; Deursen, J.V.; Goronzy, J.; et al. Therapy-induced senescence: Opportunities to improve anticancer therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 2021, 113, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingoni, A.; Antonangeli, F.; Sozzani, S.; Santoni, A.; Cippitelli, M.; Soriani, A. , The senescence journey in cancer immunoediting. Mol Cancer 2024, 23, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pitcher, L.E.; Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D.; Zhu, Y. , Cellular senescence: A key therapeutic target in aging and diseases. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiravand, Y.; Khodadadi, F.; Kashani, S.M.A.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Hosseini, S.; Sadeghirad, H.; Ladwa, R.; O'Byrne, K.; Kulasinghe, A. , Immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Curr Oncol 2022, 29, 3044–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, J.C.; Waselenko, J.K.; Maneatis, T.J.; Murphy, T.; Ward, F.T.; Monahan, B.P.; Sipe, M.A.; Donegan, S.; White, C.A. Rituximab therapy in hematologic malignancy patients with circulating blood tumor cells: Association with increased infusion-related side effects and rapid blood tumor clearance. J Clin Oncol 1999, 17, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, M.; Li, T.; Niu, M.; Zhang, H.; Wu, Y.; Wu, K.; Dai, Z. , Targeting cytokine and chemokine signaling pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grothey, A.; Blay, J.Y.; Pavlakis, N.; Yoshino, T.; Bruix, J. , Evolving role of regorafenib for the treatment of advanced cancers. Cancer Treat Rev 2020, 86, 101993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A.C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A.K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G.B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles' heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefzadeh, M.J.; Zhu, Y.; McGowan, S.J.; Angelini, L.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Xu, M.; Ling, Y.Y.; Melos, K.I.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Inman, C.L.; et al. Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan. EBioMedicine 2018, 36, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; DiPersio, J.F. , ReCARving the future: Bridging CAR T-cell therapy gaps with synthetic biology, engineering, and economic insights. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1432799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amor, C.; Feucht, J.; Leibold, J.; Ho, Y.J.; Zhu, C.; Alonso-Curbelo, D.; Mansilla-Soto, J.; Boyer, J.A.; Li, X.; Giavridis, T.; et al. Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence-associated pathologies. Nature 2020, 583, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, W.; Khalifeh, M.; Koot, M.; Palacio-Castañeda, V.; van Oostrum, J.; Ansems, M.; Verdurmen, W.P.R.; Brock, R. , RNA-based logic for selective protein expression in senescent cells. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 2024, 174, 106636. [Google Scholar]

- Ratti, M.; Lampis, A.; Ghidini, M.; Salati, M.; Mirchev, M.B.; Valeri, N.; Hahne, J.C. , MicroRNAs (miRNAs) and Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs) as New Tools for Cancer Therapy: First Steps from Bench to Bedside. Target Oncol 2020, 15, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, K.; Herbet, M.; Murias, M.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. , Senolytics: Charting a new course or enhancing existing anti-tumor therapies? Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2025, 48, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A.C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A.K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G.B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xu, Q.; Wufuer, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, R.; Jiang, Z.; Dou, X.; Fu, Q.; Campisi, J.; Sun, Y. , Rutin is a potent senomorphic agent to target senescent cells and can improve chemotherapeutic efficacy. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e13921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, H. , Cellular senescence in health, disease, and lens aging. In Pharmaceuticals, 2025; Vol. 18.

- Khansari, N.; Shakiba, Y.; Mahmoudi, M. , Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 2009, 3, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostojic, A.; Vrhovac, R.; Verstovsek, S. , Ruxolitinib: A new JAK1/2 inhibitor that offers promising options for treatment of myelofibrosis. Future Oncol 2011, 7, 1035–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamming, D.W. , Inhibition of the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)-rapamycin and beyond. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagosklonny, M.V. , Rapamycin extends life- and health span because it slows aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2013, 5, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroja-Mazo, A.; Revilla-Nuin, B.; Ramírez, P.; Pons, J.A. , Immunosuppressive potency of mechanistic target of rapamycin inhibitors in solid-organ transplantation. World J Transplant 2016, 6, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.E.; Zhou, Z. , Senescent cells as a target for anti-aging interventions: From senolytics to immune therapies. J Transl Int Med 2025, 13, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.; Duran, I.; Gil, J. , Senescence as a therapeutic target in cancer and age-related diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2025, 24, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).