Submitted:

01 September 2025

Posted:

01 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

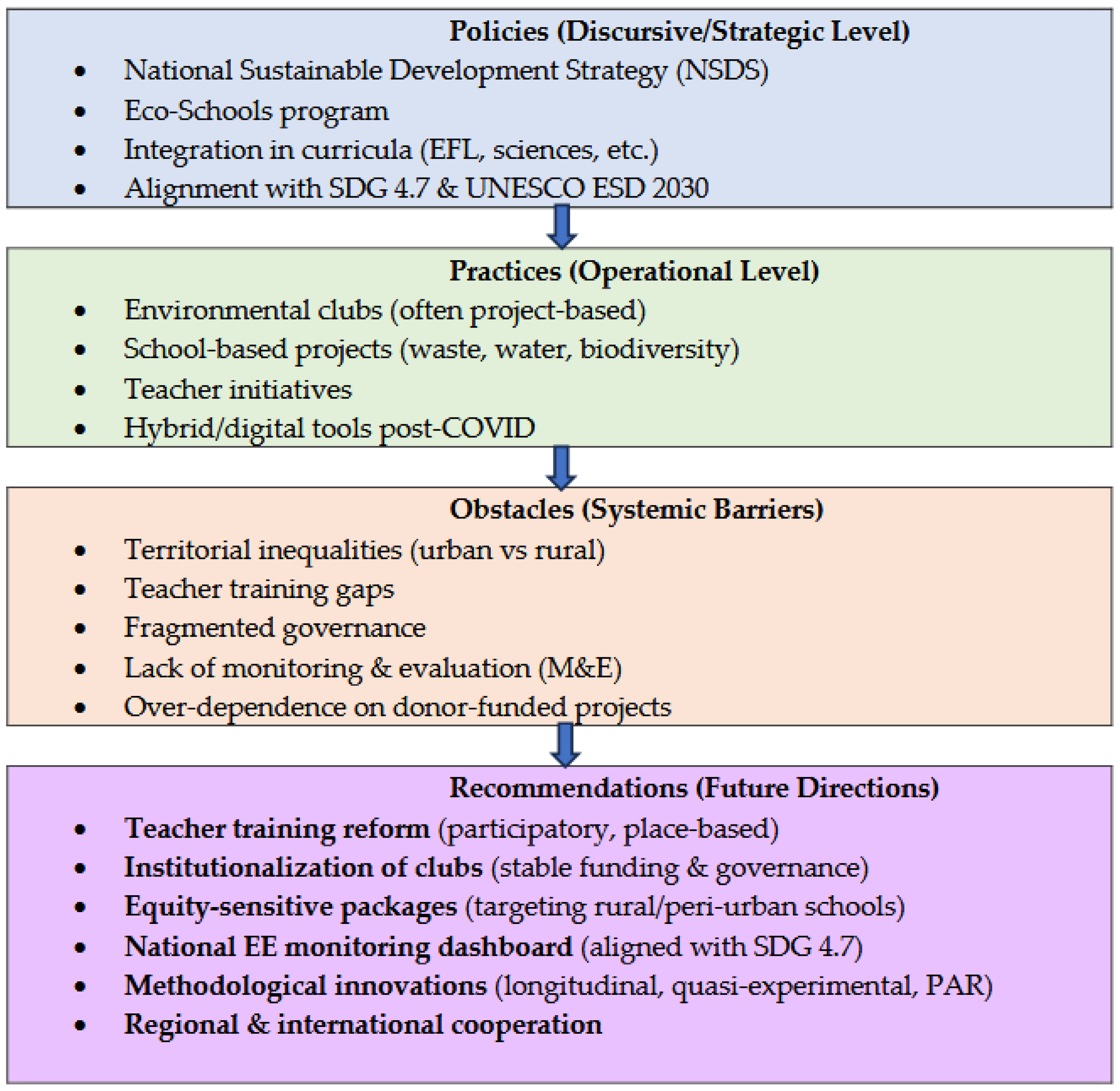

- Reform of initial and in-service teacher training, embedding mandatory modules on participatory, place-based, and interdisciplinary EE approaches.

- Institutionalisation of environmental clubs through baseline funding, shared governance, and simplified monitoring and evaluation mechanisms.

- Reduction of territorial inequalities via “equity packages” (educational kits, connectivity, coaching) targeted at rural and peri-urban areas.

- Creation of a national EE indicator dashboard aligned with SDG 4.7 to guide funding allocations and strengthen accountability.

1. Literature Review

2.1. Global Frameworks and Trends in Environmental Education

2.2. The Moroccan Policy Landscape

2.3. COVID-19 as a Disruptive and Catalytic Force

2.4. Research Gaps and Added Value of the Present Study

- Mapping Morocco’s EE alignment with SDG 4.7 and the UNESCO ESD 2030 Roadmap, situating it within a comparative Global South perspective (Africa, Asia, Latin America).

- Proposing actionable reforms that are directly operationalizable in Moroccan educational policy and practice, including teacher training reform, institutionalization of school environmental clubs, targeted equity packages for underserved areas, and the creation of a national EE monitoring dashboard.

2. Materials and Methods

- To what extent do Moroccan EE policies and practices align with global frameworks and post-pandemic priorities?

- What structural and institutional barriers (e.g., territorial inequalities, teacher capacity gaps, fragmented governance) limit equitable and context-sensitive EE?

- Which strategies—especially participatory, place-based, and justice-oriented approaches—can enhance EE’s transformative potential in Morocco?

2.1. Review Design and Rationale

2.2. Search Strategy and Information Sources

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

- Peer-reviewed articles or official policy documents focusing on EE/ESD theory, policy, or practice.

- Studies with a direct focus on Morocco, or comparative studies including Morocco.

- Clear methodological framing (empirical, policy-oriented, or conceptual).

- Non-refereed grey literature (e.g., blogs, non-peer-reviewed abstracts).

- Studies lacking methodological transparency or sufficient analytical depth.

- Publications outside the EE/ESD scope for Morocco.

- Theses/dissertations not formally peer-reviewed.

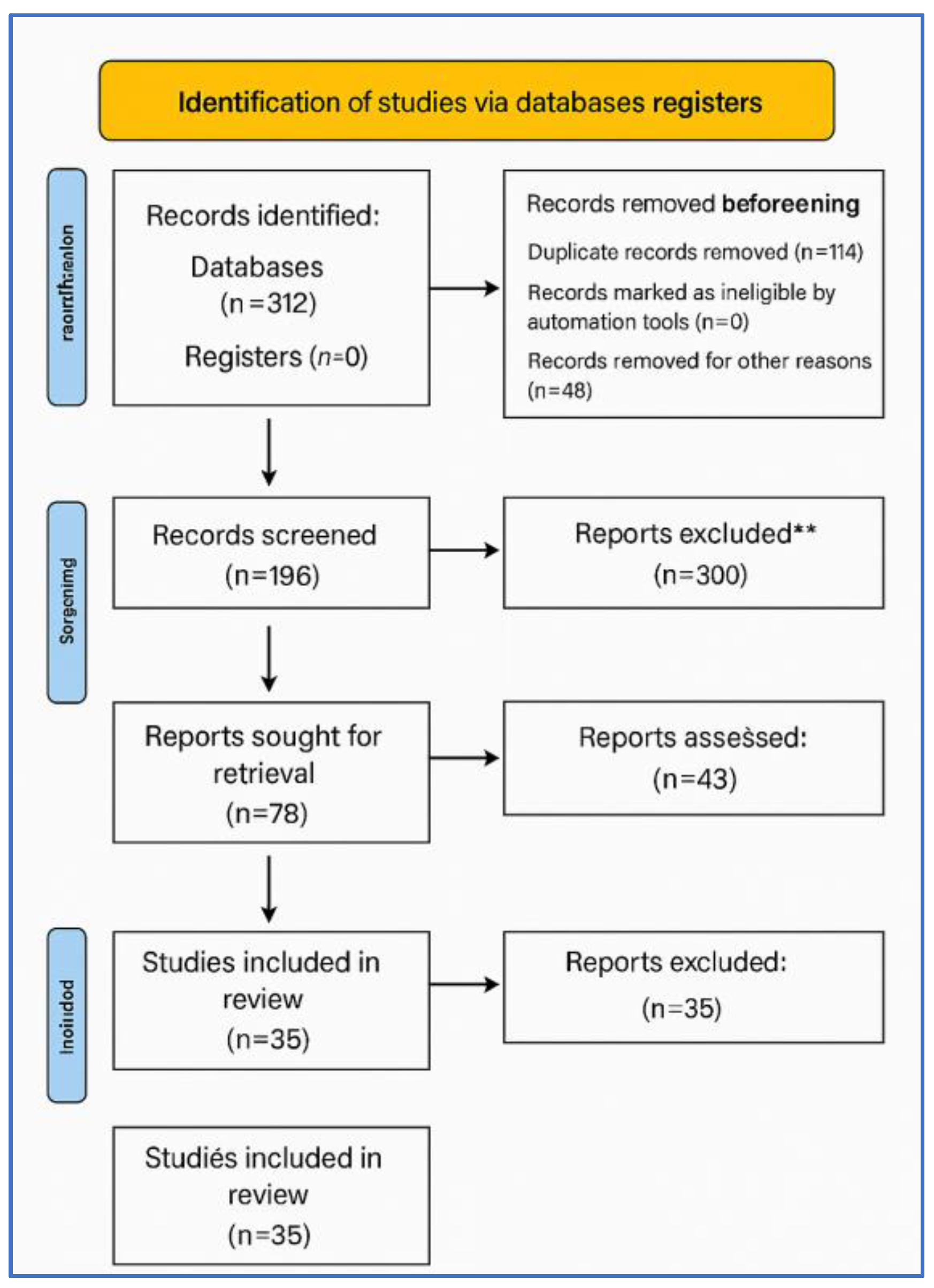

2.4. Study Selection and Inter-Rater Agreement

- Lack of focus on Morocco (n = 15)

- Absence of methodological transparency (n = 12)

- Insufficient analytical depth (n = 9)

- Not within EE/ESD scope (n = 7)

2.5. Data Extraction

- Authorship, year, setting, design, and sample.

- Methodological approach (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed).

- Thematic focus (policy, pedagogy, institutional barriers, COVID-19).

- Links to SDGs (esp. 4.7).

- Key findings and limitations.

2.7. Quality Appraisal and Risk of Bias

- High quality (≥80%),

- Acceptable (60–79%),

- Low (<60%).

- Language bias (English/French restriction excluding Arabic, mitigated via abstract screening).

- Publication bias (over-representation of positive results).

2.8. Data Synthesis and Analyses

2.9. Compliance with PRISMA 2020

2.10. Ethical Considerations and GenAI Disclosure

3. Results and Discussion

- Section 3.1—RQ1: To what extent do Moroccan EE policies and practices align with global frameworks and post-pandemic priorities?

- Section 3.2—RQ2: What structural and institutional barriers limit equitable and context-sensitive EE?

- Section 3.3—RQ3: Which strategies—especially participatory, place-based, and justice-oriented approaches—can enhance EE’s transformative potential in Morocco?

- 2 studies (≈6%) were rated Low quality (< 60%), often due to weak methodological reporting or limited generalizability.

3.1. Policy Alignment of Morocco’s Environmental Education with the SDGs and ESD 2030 Roadmap

3.2. Identifying Systemic and Structural Barriers to Moroccan Environmental Education

- Territorial inequality. Pronounced urban–rural/peri-urban gaps in infrastructure, staffing, and the functionality of environmental clubs restrict the continuity of EE in under-resourced areas. These findings echo national patterns [13,47] and resonate with broader evidence from the Global South, where structural disparities remain a major determinant of educational equity [48].

- Insufficient teacher preparation. Despite curricular references to sustainability, pre-service and in-service programs seldom embed participatory, place-based, or critical pedagogies. As a result, practice often remains informational rather than transformative, which undermines students’ capacity for critical ecological thinking [49,50,59]. This gap illustrates the need to shift from knowledge transmission toward competency-oriented approaches in line with Education for Sustainable Development (ESD).

- Fragmented institutional coordination. EE delivery is frequently dependent on short-term, donor-driven projects with limited integration into national curricula or governance frameworks. The lack of standardized guidance and light-touch monitoring and evaluation (M&E) mechanisms constrains both continuity and scalability [11,12,22,44]. This reliance on temporary initiatives reflects a systemic fragility that hampers the institutionalization of EE.

- Cross-cutting policy–practice gap. While national policies formally align with SDG 4.7 and the UNESCO ESD 2030 Roadmap, uneven implementation guidance—especially regarding roles, resources, and indicators—prevents effective local adaptation. The issue is particularly acute in rural and peri-urban contexts where resource constraints are most severe [1,13,53].

3.3. Post-Pandemic Dynamics and Policy Opportunities for Environmental Education in Morocco

- Institutionalize health–environment education, including One Health perspectives linking human, animal, and ecosystem health;

- Expand teacher professional development focused on participatory, place-based, and critical pedagogies;

- Embed adaptive hybrid approaches into school governance, ensuring continuity during future crises;

3.4. Bibliometric and Thematic Profile of the Reviewed Studies

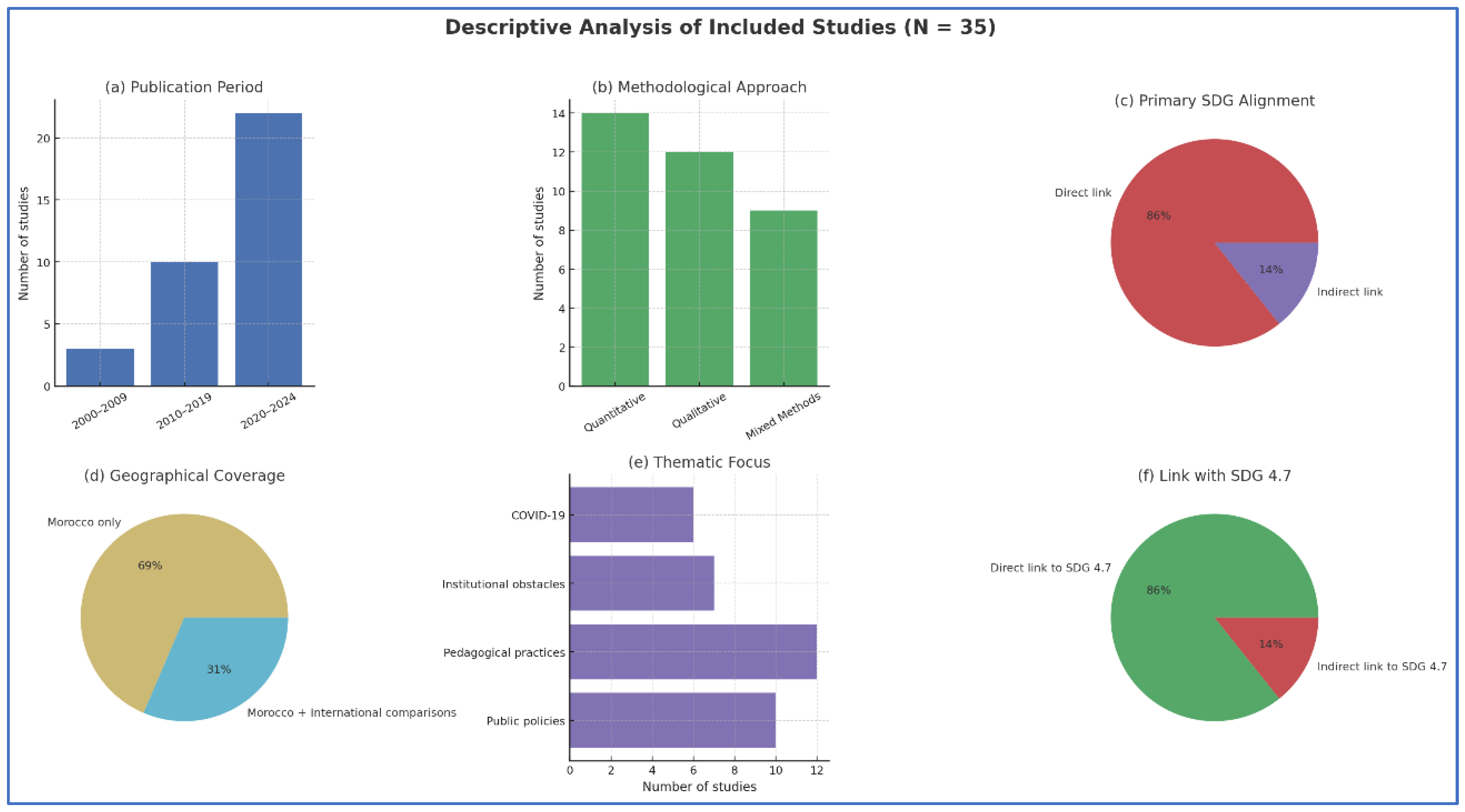

- Publication period—Three distinct phases were identified: a low output between 2000–2009, moderate growth during 2010–2019, and a pronounced surge after 2020 associated with the COVID-19 pandemic [Figure 2a].

- Methodological approach—Quantitative designs predominate (40%), followed by qualitative (34%) and mixed-methods (26%), with integrated designs gaining visibility after 2017 [Figure 2b].

- Primary SDG alignment—86% of studies are directly linked to the Sustainable Development Goals (mainly SDG 4.7), while 14% connect indirectly via SDGs 3, 6, and 13 [Figure 2c].

- Geographical coverage—69% of studies focus solely on Morocco, whereas 31% include international comparisons [Figure 2d].

- Thematic focus—The most common areas are pedagogical practices (31%), institutional obstacles (20%), COVID-19 integration (20%), and public policy (14%) [Figure 2e].

- SDG 4.7 linkages—86% explicitly connect with SDG 4.7, while 14% do so indirectly [Figure 2f].

3.5. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats Shaping the Future of Environmental Education in Morocco

- Yet, weaknesses remain pronounced. The geographic concentration of research in urban centers sidelines rural and mountain areas, which are precisely the regions most vulnerable to climate risks. Similarly, the lack of longitudinal and experimental designs weakens the capacity to evaluate the long-term impacts of interventions [57,58].

- Opportunities are significant: the alignment with SDG 4.7 and ESD 2030 opens avenues for international cooperation, funding, and scaling-up. Furthermore, the integration of health–environment dimensions in the wake of COVID-19 provides an entry point for embedding EE into broader resilience and public health policies [36,52]. Digital tools and citizen science further represent vectors for democratizing EE access across Morocco’s diverse territories.

- Threats, however, jeopardize these gains. Persistent inequalities in teacher preparation and resource allocation risk entrenching uneven access to EE. Additionally, policy volatility and dependence on external projects hinder institutional stability, while climate-related crises may shift policy priorities away from EE [38,45].

3.6. Situating Moroccan Environmental Education Within the Global Research Landscape

- Broadening methodological diversity, moving beyond cross-sectional surveys to include longitudinal, participatory, and experimental designs.

- Deeper institutional embedding of EE through teacher education, environmental clubs, and structured monitoring and evaluation frameworks.

- Strengthening international partnerships for knowledge exchange and capacity building, ensuring that Morocco can benefit from and contribute to South–South and North–South cooperation in EE.

3.7. General Synthesis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EE | Environmental Education |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| ESD | Education for Sustainable Development |

| NSDS | National Sustainable Development Strategy |

| MEN | Ministère de l’Éducation Nationale |

References

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, 2020; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=fr.

- Ardoin, N. M.; Bowers, A. W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental education outcomes for conservation: A systematic review. Biological Conservation 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadeeva, Z.; Mochizuki, Y. Competences for sustainable development and sustainability: Significance and challenges for ESD. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 2010, 11, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorina, L.; Gordova, M.; Khristoforova, I.; Sundeeva, L.; Strielkowski, W. Sustainable education and digitalization through the prism of the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V. J.; Navarro Jiménez, E.; Jiménez, M.; Hormeño Holgado, A.; Martínez González, M. B.; Tornero Aguilera, J. F.; Beltrán Velasco, A. J. Sustainable development goals in the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, S. N.; Stephens, J. C.; White, B. Environmental education in transition: A review of recent research in environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education 2019, 50, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonne, C. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for accelerating sustainable development. Environmental Research 2021, 193, 110482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdom of Morocco, Ministry of Energy, Mines and Sustainable Development. (2017). National Strategy for Sustainable Development (NSDS 2017): Executive summary and strategic framework. Rabat: Government of Morocco. Retrieved from African Clean Cities Platform:. Available online: https://www.africancleancities.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/4_National_Strategy_for_Sustainable_Development_and_Territorialization_of_its_Implementation_in_Morocco.pdf.

- Eco-Schools Global. (2025, January 28). 100 Green Flags rising in Morocco. Foundation for Environmental Education (FEE). Retrieved from:. Available online: https://www.ecoschools.global/news-stories/2025/1/28/100-green-flags-rising-in-morocco.

- El Gourari, W.; Ed-Dali, R. Environmental education in Moroccan EFL curricula: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics 2024, 6, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Batri, B.; Maskour, L.; Ksiksou, J.; Jeronen, E.; Ismaili, J.; Alami, A.; Lachkar, M. Environmental education in Moroccan primary schools: Promotion of representations, knowledge, and environmental activities. Ilkogretim Online 2020, 19, 653–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Batri, B.; Maskour, L.; Ksiksou, J.; Jeronen, E.; Ismaili, J.; Alami, A.; Lachkar, M. Education for sustainable development in Moroccan schools: Obstacles and opportunities. Education Sciences 2022, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehbouni, G. Environmental governance and education challenges in Morocco. Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy 2024, 15, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haelermans, C.; Korthals, R.; Jacobs, M.; de Leeuw, S.; Vermeulen, S.; de Wolf, I. COVID-19 and educational inequality: How school closures affect student outcomes. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0261114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, A. R.; Srisarajivakul, E. N.; Hasselle, A. J.; Pfund, R. A.; Knox, J. Remote learning and student well-being during COVID-19. Current Opinion in Psychology 2023, 48, 101632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettalongi, S. S.; Londol, M. M.; Umboh, S. E. The impact of COVID-19 on rural education in Indonesia. Borneo Educational Journal 2024, 3, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzediegwu, C.; Chang, S. X. Improper management of COVID-19 medical waste threatens environmental sustainability. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju Zaveroni, Y.; Lee, S. Integrating environmental and health education during COVID-19. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward AA, Borisenoka I, Bhagat N and LeBreton GTO. Environmental education during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from Ontario, Canada. Front. Educ. 2024; 9, 1430882. [CrossRef]

- Tzimiris, S.; Nikiforos, S.; Kermanidis, K. L. Hybrid learning and environmental education post-COVID-19. Education and Information Technologies 2023, 28, 1582–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochizuki, Y.; Vickers, E. Still ‘the conscience of humanity’? UNESCO’s vision of education for peace, sustainable development and global citizenship. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 2024, 54, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouamama, C.; El Hnot, H.; El Fellah Idrissi, B.; Akkaoui, E. G. Les clubs d’environnement dans les établissements scolaires au Maroc: Une voie prometteuse pour l’ancrage de l’éducation à l’environnement. European Scientific Journal 2017, 13, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, A. A.; Borisenoka, I.; Bhagat, N.; LeBreton, G. T. O. Environmental education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from Ontario, Canada. Frontiers in Education 2024, 9, 1430882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- abderrahmane riouch, saad benamar, halima ezzeri, & najat cherqi. Knowledge and representation of environmental education among high school students in morocco. Jilin Daxue Xuebao (Gongxueban)/Journal of Jilin University (Engineering and Technology Edition). 2024, 43, 46–66. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med, 2021; 18, e1003583. [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M. P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; Rousseau, M. C.; Vedel, I. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2019, 111, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement 1960, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). (2019). CASP qualitative checklist. CASP UK. Retrieved from:. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Tyndall, J. (2010). AACODS checklist: Appraising the quality of grey literature for inclusion in systematic reviews. Flinders University. Available online: https://dspace.flinders.edu.au/jspui/bitstream/2328/3326/4/AACODS_Checklist.pdf.

- Weihrich, H. The TOWS matrix—A tool for situational analysis. Long Range Planning 1982, 15, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J.; Tabish, H.; Welch, V.; Petticrew, M.; Pottie, K.; Clarke, M.; Tugwell, P. Applying an equity lens to interventions: Using PROGRESS-Plus to ensure equity considerations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2014, 67, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dis, E. A. M.; Bollen, J.; Zuidema, W.; van Rooij, R.; Bockting, C. L. H. ChatGPT: Five priorities for research. Nature 2023, 614, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherai, B.; El Hnot, H.; Idrissi, B. E. F.; Akkaoui, E. G. Les Clubs D’environnement Dans Les Établissements Scolaires Au Maroc: Une Voie Prometteuse Pour L’ancrage De L’éducation À L’environnement. European Scientific Journal, ESJ 2017, 13, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abderrahmane RIOUCH, and Saad BENAMAR. “Evaluation and Proposals for Improving the Situation of Environmental Education in Morocco.”. American Journal of Educational Research 2018, 6, 621–631. [CrossRef]

- Oleribe, O. O.; Taylor-Robinson, S. D.; Taylor-Robinson, A. W. COVID-19 post-pandemic reflections from sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now that we wish we knew then. Public health in practice (Oxford, England) 2024, 7, 100486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongoma, V.; Epule, T.; Brouziyne, Y.; et al. COVID-19 response in Africa: impacts and lessons for environmental management and climate change adaptation. Environ Dev Sustain 2024, 26, 5537–5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. (2017). Sacred Ecology (4th ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, M.; Kostova, Z.; Marcinkowski, T. Components of environmental literacy in elementary science education standards: Promoting environmental education for sustainability. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research 2009, 35, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hungerford, H. R.; Volk, T. L. Changing Learner Behavior Through Environmental Education. The Journal of Environmental Education 1990, 21, 8–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B. B. Environmental and health education viewed from an action-oriented perspective: a case from Denmark. Journal of Curriculum Studies 2004, 36, 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. Childhood nature connection and constructive hope: A review of research on connecting with nature and coping with environmental loss. People and Nature 2020, 2, 619–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, G. A.; Hoody, L. L. Closing the achievement gap: Using the environment as an integrating context for learning; State Education and Environment Roundtable (SEER): San Diego, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O.; Heras-Saizarbitoria, I. & Brotherton, MC. Assessing and Improving the Quality of Sustainability Reports: The Auditors’ Perspective. J Bus Ethics 2019, 155, 703–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huoponen, A. How eco-clubs foster pro-environmental behavior in a school context: A case from Finland. Fennia—International Journal of Geography, 2025; 202, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzorka, A.; Akiyode, O. & Isa, S.M. Strategies for engaging students in sustainability initiatives and fostering a sense of ownership and responsibility towards sustainable development. Discov Sustain 2024, 5, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayad, A.; Chakib, A.; Rouass, M.; Boustani, R. The status of environment in educational institutions: High schools of the city of Fez, Morocco, as a case study. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2015; 195, 1516–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zickafoose, A.; Ilesanmi, O.; Diaz-Manrique, M.; Adeyemi, A. E.; Walumbe, B.; Strong, R.; Wingenbach, G.; Rodriguez, M.; Dooley, K. Barriers and challenges affecting quality education (Sustainable Development Goal 4) in Sub-Saharan Africa by 2030. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulà, I.; Tilbury, D. Teacher education for the green transition and sustainable development (EENEE Analytical Report). European Commission, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Paço, A.; Upadhyay, D. Option or necessity: Role of environmental education as a transformative change agent. Evaluation and Program Planning 2023, 97, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Moussaouy, A.; Abderbi, J.; Daoudi, M. Environmental education in the teaching and learning of scientific disciplines in Moroccan high schools (Physics/Chemistry and Biology/Geology). International Education Studies 2014, 7, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education and digital inequity in the COVID-19 era: Challenges for developing countries (Policy brief). UNESCO, 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379874.

- Chankseliani, M.; McCowan, T. Higher education and the Sustainable Development Goals. Higher education 2021, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wals, A. E. J.; Brody, M.; Dillon, J.; Stevenson, R. B. Convergence between science and environmental education. Science 2014, 344, 583–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munasinghe, M. COVID-19 and sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainable Development 2020, 23(1–2), 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, J. M.; Esquivel-Martín, T. New insights for teaching the One Health approach: Transformative environmental education for sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W.; Plano Clark, V. L. Designing and conducting mixed methods research, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/designing-and-conducting-mixed-methods-research/book241842.

- Bryman, A. Social research methods, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; Available online: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/social-research-methods-9780199689453.

- Wafubwa RN, Soler-Hampejsek E, Muluve E, Osuka D, Austrian K. Adolescent school retention post COVID-19 school closures in Kenya: A mixed-methods study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19: e0315497. [CrossRef]

- Panakaje, N.; Rahiman, H. U.; Rabbani, M. R.; Kulal, A.; Pandavarakallu, M. T.; Irfana, S. COVID-19 and its impact on educational environment in India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 2022, 29, 27788–27804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vale, M. M.; Berenguer, E.; Argollo de Menezes, M.; Viveiros de Castro, E. B.; Pugliese de Siqueira, L.; Portela, R. C. Q. The COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity to weaken environmental protection in Brazil. Biological Conservation 2021, 255, 108994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damoah, B.; Omodan, B. I. Determinants of effective environmental education policy in South African schools. International Journal of Educational Research Open 2022, 3, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo Zambrano, R. V.; Milanes, C. B.; Pérez Montero, O.; Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Nexar Bolivar, L. O.; Cobeña Loor, D.; García Flores De Válgaz, R. G.; Cuker, B. A sustainable proposal for a cultural heritage declaration in Ecuador: Vernacular housing of Portoviejo. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, A. R.; Ford, M. E.; Brewer, C. A. A framework for integrating ecological literacy, civics literacy and environmental citizenship in environmental education. In E. A. Johnson & M. J. Mappin (Eds.), Environmental education and advocacy: Changing perspectives of ecology and education; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 227–266.

- Grund, J.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; Büssing, A. G. Emotions and transformative learning for sustainability: A systematic review. Sustainability Science 2024, 19, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMEZIANE, N. Place of the environment in the Moroccan curricula of Life and Earth Sciences in the secondary education. The Journal of Quality in Education 2018, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sbai, A.; El Mediouni, A.; Hakim, H.; Mentak, S. Analysis of students’ conceptions of biodiversity and the environment: A Moroccan case study. European Journal of Engineering Research and Science 2020, 5, 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhazzama, M.; Mssassi, S. The impact of experiential learning on Environmental Education during a Moroccan summer university. E3S Web of Conferences, 0003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Azzouzi, A.; Elachqar, A.; Kaddari, F. Integrating environmental education into physics instruction: Insights from teachers regarding students’ engagement. Randwick International of Education and Linguistics Science Journal 2023, 4, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eco-Schools Morocco (2025). 100 schools in Morocco earned the Green Flag for 2023/2024 through the Eco-Schools programme. Retrieved January 28, 2025, from Eco-Schools News website: https://www.ecoschools.global/news-stories/2025/1/28/100-green-flags-rising-in-morocco.

- Daoudi, M. Education in renewable energies: A key factor of Morocco’s 2030 Energy Transition Project. Exploring the impact on SDGs and future perspectives. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoudi, M. New paradigm for renewable energy education in Morocco. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Publications 2020, 3, 119–123. Available online: https://ijmrap.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/IJMRAP-V3N1P119Y20.pdf.

- Bekhat, B.; Madrane, M.; Idrissi, R. J.; Zerhane, R.; Laafou, M. Towards an effective environmental education: A survey in the Moroccan education system. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies 2020, 29, 1–10. Available online: https://ijias.issr-journals.org/abstract.php?article=IJIAS-20-313-01.

- Rachad, S.; Oughdir, L. Exploring the benefits of e-learning for life and earth sciences education in Moroccan high schools. Journal of E-Learning and Research. [CrossRef]

- Idrissi, H. Examining STEM pre-service teachers’ perceptions of climate change education: Insights from Morocco. Environmental Education Research 2025, 31, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alami, A.; Chait, A. Assessment of Citizens’ Knowledge, Attitudes and Behaviours toward Ecological and Environmental Problems in Morocco for Natural Resources Conservation and Sustainable Waste Management. Journal of Analytical Sciences and Applied Biotechnology (JASAB) 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fanini, L.; Fahd, S. Storytelling and environmental information: connecting schoolchildren and herpetofauna in Morocco. Integrative zoology 2009, 4, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guaadaoui, A.; El Alami, S.; Chait, A. Preserving the environment and establishing sustainable development: An overview on the Moroccan model. E3S Web of Conferences 2021, 234, 00065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifqiren, S.; Bouzit, S.; Kouchou, I.; Selmaoui, S. Modelling in the scientific approach to teaching life and earth sciences: Views and practices of Moroccan teachers. Journal of Education and E-Learning Research 2023, 10, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtuluş, M. A.; Tatar, N. A bibliometrical analysis of the articles on environmental education published between 1973 and 2019. Journal of Education in Science, Environment and Health 2021, 7, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourredine, H.; Barjenbruch, M.; Million, A.; El Amrani, B.; Chakri, N.; Amraoui, F. Linking Urban Water Management, Wastewater Recycling, and Environmental Education: A Case Study on Engaging Youth in Sustainable Water Resource Management in a Public School in Casablanca City, Morocco. Education Sciences 2023, 13, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laaloua, H. The role of education in addressing environmental challenges: A study of environmental education integration in Moroccan geography textbooks. International Journal of Social Science and Human Research 2023, 6, 2317–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaroufi, F.; El Malki, M.; Arabi, M. Environmental awareness in the Oriental region of Morocco: A review. E3S Web of Conferences 2024, 527, 04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachad, S.; Oughdir, L. What position does experimentation hold in environmental education and sustainable development in primary schools in Morocco? Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University 2022, 57, 1182–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait El Mokhtar, K.; Zerhane, R.; El Hammoumi, S.; Amiri, E. M.; Kaddam, M.; Drissi, M. M.; Janati-Idrissi, R. Pedagogical innovation and the development of 21st century skills and sustainable development in the teaching and learning of life and earth sciences in Morocco. E3S Web of Conferences, 0102; 412, 01022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerrouqi, Z.; Abderbi, J.; Ziani, S. Les concepts séismes et risques sismiques dans les manuels scolaires des Sciences de la Vie et de la Terre au Maroc. European Scientific Journal ESJ 2024, 20, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzemri, M.; Bensasi. E. Miloudi. La place de la dimension environnementale dans le nouveau curriculum du primaire au Maroc. Revue Internationale Des Sciences De Gestion 2021, 4. Retrieved from https://www.revue-isg.com/index.php/home/article/view/669.

- El Alaoui, A. A. E.; Abdelali, F.; Kafssi, M. The implementation of the sustainable development goals at the level of education in Morocco. Emirati Journal of Education and Literature, 2024; 2, 4–22. Available online: https://search.shamaa.org/PDF/Articles/TSEjel/EjelVol2No1Y2024/ejel_2024-v2-n1_004-022_eng_authsub.pdf.

- Zerrouqi, Z.; Iyada, A.; Bouamiech, M. Education on environment and its pollution using life and earth sciences textbooks in Moroccan middle schools. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 2016; 17, 707–717. Available online: http://www.ijias.issr-journals.org/abstract.php?article=IJIAS-16-074-07.

- Abid, C.; Essedaoui, A.; Selmaoui, S. Analysis of integrating education for sustainable development into the life and earth sciences curriculum at secondary school—Morocco. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University 2024, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Profil national du Maroc—Éducation en vue du développement durable; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Saayoun, S.; El Fathi, T.; Ghizlane, C.; Abidi, O.; Lamri, D.; Ibrahmi, E. Teacher perspectives on Life and Earth Sciences textbook evaluation in Moroccan middle and high schools. Journal of Educational and Social Research 2024, 14, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrissi Boutaybi, S.; Hartikainen, T.; Benyamina, Y.; Laine, S. Gardening School to Support Youth Inclusion and Environmental Sustainability in Morocco. Social Sciences 2024, 13, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lbadaoui-Darvas, M.; Lbadaoui, A.; Labjar, N.; El Hajjaji, S.; Nenes, A.; Takahama, S.; Roy, A. Introducing project-based climate education in Moroccan universities via a new air quality monitoring network in Rabat. E3S Web of Conferences 2023, 418, 05003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Type | High Quality | Acceptable Quality | Low Quality | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative/Mixed-methods | 8 | 13 | 2 | 23 |

| Qualitative | 1 | 9 | 0 | 10 |

| Policy/Official documents | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 9 | 24 | 2 | 35 |

| No. | Authors & Year | Context/Education Level | Study Type & Methodology | Main Obstacles | Levers/Good Practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | El-Batri et al. [11] | Primary schools (4, Morocco) | Quantitative (survey & test) | Limited contextualization; socio-economic inequalities | Adapt content to local context; practical activities fostering learning |

| 2 | El-Batri et al. [12] | Teachers (636, Fès–Meknès) | Quantitative (survey) | Lack of training/resources; reliance on traditional methods | Continuous professional development; active pedagogy; interdisciplinary integration |

| 3 | Sayad et al. [47] | High schools (6, Fez) | Quantitative (survey—teachers & students) | Lack of admin support; limited resources | Student & teacher willingness to engage in EE |

| 4 | Cherai et al. [34] | 15 schools (Tangier–Tétouan–Al Hoceima) | Mixed-method (survey + testimonies) | Heavy workload; lack of follow-up/materials | Teacher training; collaborative projects; participatory approaches |

| 5 | Ameziane [66] | Secondary LES curricula (10 high schools) | Documentary + Survey | Limited environmental content; overly informative approach; weak resources | Stronger curricular integration; diversified pedagogical methods |

| 6 | Sbai et al. [67] | High schools—Bouarfa & Jerada (Eastern Morocco) | Quantitative (survey + multivariate analysis) | Predominantly anthropocentric conceptions; limited ecological representation | Adapt pedagogy to include ecocentric values; context-sensitive content |

| 7 | Bouhazzama & Mssassi [68] | Tangier Summer University (30 participants) | Qualitative (case study; observation + interviews) | Limited resources; theory–practice gap; insufficient funding | Experiential learning workshops; emotional/contextual learning |

| 8 | El Moussaouy et al. [51] | Oujda Academy (90 physics & biology teachers) | Mixed-methods (documentary + survey) | Low EE integration; dominance of informative pedagogy; lack of interdisciplinarity | Curricular reform; teacher training; active, integrated pedagogies |

| 9 | El Azzouzi et al. [69] | Fez–Meknes (120 physics teachers) | Quantitative (survey) | Lack of curricular contextualization; weak teacher training | Curricular innovation; contextualized EE to stimulate engagement |

| 10 | Eco-Schools Morocco [70] | National (5,000+ schools) | Documentary—Institutional report | Dependence on external funding; territorial disparities | Community-based approaches; concrete projects (gardens, recycling, water) |

| 11 | Daoudi 71] | Morocco—prospective analysis | Theoretical (prospective scenarios) | Absence of renewable energy training in schools | Integrate energy topics into curricula |

| 12 | Daoudi [72] | Morocco—policy analysis | Documentary (policy review) | Education–energy sector disconnect | Align curricula with green transition & labor market |

| 13 | Bekhat et al. [73] | High schools (various regions) | Quantitative (survey) | Traditional pedagogy; limited resources | Continuous training; ecological field trips |

| 14 | Rachad & Oughdir [74] | Fès—150 high school students | Quantitative (survey; pre/post-test) | Digital divide; lack of practical tools | E-learning improved outcomes; supports blended learning |

| 15 | Idrissi [75] | Pre-service STEM teachers (Fès–Meknès) | Quantitative (survey) | Low climate content knowledge; weak training support | High motivation; integrate climate modules in training |

| 16 | El-Alami & Cit [76] | Morocco—general population (>500) | Quantitative (national survey) | Limited knowledge; low pro-environmental behaviours | Awareness campaigns; integration into education |

| 17 | Fanini & Fahd [77] | Primary schools (Tétouan) | Experimental (storytelling intervention) | Low student engagement without cultural relevance | Storytelling; use of local heritage |

| 18 | Guaadaoui et al. [78] | Morocco—national analysis | Conceptual (policy review) | Institutional fragmentation; regional disparities | Integrated national strategies; cross-sectoral planning |

| 19 | Ifqiren et al. [79] | 96 Life & Earth Sciences teachers | Quantitative (survey) | Limited use of modelling; weak training in methods | Introduce modelling tasks; teacher professional development |

| 20 | Kurtuluş & Tatar [80] | International (incl. Morocco) | Bibliometric review | Low Moroccan research presence | Position Morocco in global EE research; identify priorities |

| 20b | Nourredine et al. [81] | Casablanca—public high school | Case study—Participatory action | Weak curricular integration; low awareness | Experiential/interdisciplinary projects; researcher–school partnerships |

| 21 | Laaloua [82] | 8 high schools, Agadir (524 students) | Quantitative (survey + textbook analysis) | Limited human–environment links; weak multicultural lens | Enrich geography curricula; promote critical/multicultural thinking |

| 22 | Maaroufi et al. [83] | Oriental region | Regional review—Documentary | Regional disparities; lack of coordination | Context-adapted strategies; regional partnerships |

| 23 | Rachad & Oughdir [84] | Primary schools (teachers/admins) | Quantitative (survey) | Weak experimental culture; lack of teaching materials | Develop experimental pedagogy; teacher training |

| 24 | Ait El Mokhtar et al. [85] | Secondary schools—SVT | Mixed-methods (surveys + practice analysis) | Weak teacher training in 21st-century skills | Project-based learning; ICT integration; SD-oriented skills |

| 25 | Riouch & Benamar [35] | Morocco—national perspective | Documentary (critical analysis) | Institutional fragmentation; regional disparities; weak training | Intersectoral coordination; regionalized programs |

| 26 | Zerrouqi et al. [86] | Middle schools—SVT textbooks | Documentary (content analysis) | Limited content; lack of local contextualization | Revise textbooks; include local themes |

| 27 | Ouzemri & Bensasi (2021) [87] | orocco—primary curriculum | Mixed-method (curriculum analysis + policy review) | Curriculum–practice alignment gap | Update curriculum content; integrate EE dimension |

| 28 | El Alaoui, A. A. E., Abdelali, F., & Kafssi, M. [88] | Morocco—national level | Qualitative & policy analysis (documentary + institutional review) | Partial and uneven implementation of SDGs in education, weak governance, and fragmented strategies | Strengthen national coordination; reinforce teacher training; align curricula with SDG 4.7 and ESD 2030 Roadmap |

| 29 | Zerrouqi, Z., Iyada, A., & Bouamiech, M. (2016) [89] | Middle schools—SVT textbooks | Documentary (content analysis) | Limited content; local/global imbalance | Update textbooks; integrate local content |

| 29 | Abid et al. [90] | Secondary schools—SVT | Documentary (content analysis) | Uneven ESD integration | Harmonize ESD modules; strengthen interdisciplinary activities |

| 30 | UNESCO [91] | Morocco—national profile | Policy/institutional report | Weak EE/ESD integration; fragmentation | National commissions; supportive structures |

| 32 | Saayoun et al. [92] | Middle & high schools (243 teachers) | Quantitative (survey) | Cultural irrelevance; language issues | Teacher feedback loops; culturally adapted textbooks |

| 33 | Id-Babou et al. [93] | High schools—Guelmim (rural & urban) | Quantitative & qualitative (Q & interviews) | Incomplete biodiversity concept; weak pedagogical activities | Integrate biodiversity activities; curricular conceptualization |

| 34 | Idrissi Boutaybi et al. [94] | Gardening school for NEET youth | Qualitative (case study) | Barriers for vulnerable youth; limited resources | Place-based hands-on learning; partnerships; green jobs pathways |

| 35 | Lbadaoui-Darvas et al. [95] | Rabat universities—climate/air quality | Programmatic (project-based curriculum + sensors) | Limited monitoring coverage; climate vulnerability; resources | Sensor-based learning; Climate Club; capacity building; open data outreach |

| Dimension | Identified Barriers | Recommended Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Territorial nequality | Urban–rural/peri-urban disparities in infrastructure, staffing, connectivity, and functionality of environmental clubs [13,47,48,51]. | Targeted resourcing and operational support for under-served schools; minimum service standards for EE inputs |

| Teacher training | Limited integration of participatory, place-based, and critical EE pedagogies in pre-service/in-service programs [49,50,59]. | Systematic mainstreaming of EE in teacher education; practice-based modules, mentoring, and school-based inquiry |

| Institutional coordination | Reliance on short-term, project-based initiatives; weak guidance and uneven practices [11,12,23,44]. | Stable funding lines; standardized monitoring and evaluation; participatory school governance for EE |

| Policy–practice gap | Alignment with SDG 4.7/ESD 2030 but uneven implementation guidance (roles, resources, indicators), especially in rural/peri-urban contexts [1,13,53] | Locally grounded delivery models; multi-stakeholder engagement (schools–communities–NGOs–municipalities) |

| Theme | Challenges Identified | Opportunities for EE |

|---|---|---|

| Educational disruptions | School closures; uneven readiness for remote/hybrid delivery; limited guidance for EE activities online [14,15]. | Embed health–environment/One Health content in hybrid, flexible models; provide low-tech options and classroom–community projects that can continue during disruptions [52,56]. |

| Exacerbated inequalities | Widened digital and resource gaps in rural/peri-urban contexts; uneven access to clubs and materials [16]. | Targeted investment in devices/connectivity and EE kits; community-based initiatives with local authorities/NGOs; equity-sensitive monitoring of participation/outcomes [1]. |

| Ad hoc adaptations | Reliance on individual leadership; project discontinuity; limited institutional anchoring [23,24]. | Institutionalize clubs with baseline grants and light-touch M&E; formalize stewardship projects in school plans; create simple continuity protocols for crises |

| Policy window | Heightened awareness not yet translated into system-level reforms [55]. | Strengthen teacher PD (participatory/place-based EE; micro-credentials); integrate EE into standards and appraisal; align finance and indicators with ESD-2030 priority areas [1,49]. |

| Dimension | Key Result | Interpretation/Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Publication period | Three phases: low output (2000–2009, 9%), moderate growth (2010–2019, 28%), surge post-2020 (63%). | COVID-19 acted as a catalyst, intensifying EE research. Crises can mobilize scientific and institutional attention. |

| Methodological approach | 40% quantitative, 34% qualitative, 26% mixed. Mixed methods rising after 2017. | Segmentation reflects different research aims but limited triangulation. Growing use of mixed designs signals a positive trend toward integrative approaches. |

| SDG alignment | 86% direct link to SDG 4.7; 14% indirect via SDGs 3, 6, 13. | Strong discursive integration into global agendas. Yet, systemic institutionalization remains weak, limiting impact. |

| Geographical coverage | 69% Morocco only, 31% comparative. | Limited international benchmarking restricts policy transfer and cross-context learning. |

| Thematic focus | Pedagogy (31%), institutional barriers (20%), COVID-19 (20%), policy (14%). | Pedagogy dominates while governance and institutional analyses are underexplored. Pandemic themes highlight health–environment linkages. |

| Link with SDG 4.7 | 86% explicit, 14% indirect. | Confirms Morocco’s anchoring in SDG 4.7 but remains largely declarative; stronger operationalization is needed. |

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| - Steady growth in EE-related publications since 2015, reflecting rising academic and institutional interest (Figures a, b). | - Geographic concentration of studies in urban and coastal regions; underrepresentation of rural and mountain areas (Figures c, d). |

| - Diverse methodological approaches, including quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods, enabling triangulation of findings (Figures e, f). | - Limited longitudinal and experimental designs, reducing capacity for causal inference. |

| - Increasing thematic diversification, covering policy, pedagogy, community engagement, and post-pandemic adaptation. | - Fragmentation in data sources and inconsistent operational definitions of EE indicators, hindering cross-study comparability. |

| - Emerging collaborations between academia, NGOs, and governmental actors, fostering interdisciplinary approaches. | - Scarcity of large-scale, nationally representative datasets. |

| Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|

| - Alignment of Moroccan EE goals with the SDGs and the ESD 2030 roadmap, offering leverage for international funding and partnerships. | - Persistent socio-territorial inequalities in resources and teacher training, risking widening gaps in EE access and outcomes. |

| - Integration of health–environment education post-COVID-19, enhancing EE’s relevance for resilience and public health agendas. | - Vulnerability to political and funding shifts that can destabilize long-term EE programs. |

| - Potential for digital tools, citizen science, and place-based learning to extend EE’s reach to underserved areas. | - Climate-related crises and competing policy priorities may divert attention and resources from EE. |

| - Opportunities to institutionalize environmental clubs and embed participatory methods in teacher training. | - Risk of “project-based dependency” without sustainable institutional frameworks. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).