1. Introduction

The field of artificial intelligence is undergoing a marked shift from passive prediction to

agentic systems capable of reasoning, planning, and acting in open environments [

1]. Enabled by large language models (LLMs), such systems are moving beyond conversational interfaces to execute goal-directed, multi-step operations across heterogeneous digital and physical contexts [

2]. This evolution exposes gaps in coordination, safety, and scalability: most agent stacks resemble “bare-metal” systems that force bespoke solutions for state management, tool access, concurrency, and security, creating duplication of effort, brittle deployments, and elevated risk [

3].

An operating-system (OS) abstraction proved decisive in classical computing by virtualizing hardware and standardizing process, memory, and I/O management. Analogously, the

LLM as OS, Agents as Apps vision posits model-centric kernels with language as the interface, motivating OS-like services for tools and memory [

4]. This builds on decades of multi-agent systems (MAS) work that established facilitator/blackboard coordination (e.g., the Open Agent Architecture, OAA) and standardized communication (FIPA ACL) [

5,

6]. Contemporary prototypes begin to realize this viewpoint: AIOS presents an LLM Agent Operating System with a kernel exposing unified calls and managers for context, memory, storage, tools, and access control [

7]; KAOS explores management-role agents and shared resource scheduling on Kylin OS; and AgentStore composes heterogeneous agents via a meta-agent “marketplace,” evaluating on OS-style benchmarks [

8,

9]. In parallel, real-time OS research for autonomy (e.g., Siren) underscores determinism and bounded jitter as first-class properties increasingly relevant to interactive and embodied agents [

10].

Despite this momentum, two structural gaps persist. First, the literature lacks a

requirements-driven operating model that states functional and non-functional properties—reliability, performance,

security-by-design, scalability, interoperability, and operability—in a portable, testable form suitable for enterprise, edge, and embedded deployments. Second, time semantics are seldom elevated to enforceable contracts: beyond latency optimizations or context interrupts, there is little formal distinction between hard real-time (HRT), soft real-time (SRT), and delay-tolerant (DT) regimes, each requiring specific scheduling, I/O, memory, networking, and acceptance-test policies. Moreover, while access control appears in recent systems, zero-trust primitives—capability-scoped tools, encrypted memory, and immutable/auditable traces—are not consistently treated as kernel responsibilities, despite documented risks in agent ecosystems [

3].

Contributions. This paper advances a generalized

Agent Operating System (Agent-OS) that abstracts

models + tools + environments + human-in-the-loop (HITL) orchestration. Specifically, we: (i) formalize a prioritized requirements baseline spanning functional requirements (agent lifecycle; context/memory; tool and environment connectors; orchestration and multi-agent coordination; observability; safety and governance; model/cost management; interfaces; multitenancy) and non-functional requirements (reliability; performance;

security-by-design; scalability; interoperability; operations); (ii) introduce explicit latency classes—HRT/SRT/DT—with concrete targets (e.g., jitter and deadline budgets for HRT; onset and turn-time constraints for SRT) and derive class-tied policies for scheduling, I/O, memory, networking, and acceptance tests, aligning with lessons from real-time autonomy [

10]; (iii) propose a layered architecture comprising Kernel, Resource & Service, Agent Runtime, Orchestration & Workflow, and User & Application planes with cross-cutting governance; and (iv) position this specification as a portable blueprint for SmartTech-relevant scenarios, unifying conceptual visions [

4] with emerging system prototypes [

7,

8,

9].

Realizing robust Agent-OS platforms is critical for complex, real-world domains. In autonomous systems, verifiable real-time guarantees are essential for safe operation under dynamic conditions [

10]. In smart-city contexts, a principled OS layer can coordinate distributed agents managing infrastructure, logistics, and public services at scale. By grounding agent platforms in explicit requirements, time semantics, and security primitives, we aim to catalyze a transition from bespoke pipelines to interoperable, auditable, and scalable infrastructures suitable for rigorous engineering and eventual standardization.

2. Background and Related Work

The concept of Agent Operating Systems (Agent-OS), while gaining recent traction due to the proliferation of Large Language Models (LLMs), draws from decades of research in multi-agent systems, evolving from early distributed rule-based AI frameworks to modern LLM-driven architectures. Historical roots trace back to the 1990s with the Open Agent Architecture (OAA) [

5], which used a central blackboard for coordinating heterogeneous agents, emphasizing delegation and facilitation. Similarly, JACK Intelligent Agents [

11] employed a Belief-Desire-Intention (BDI) model for rational agent behavior in Java-based environments. Platforms like JADE and middleware such as AgentScope [

12] extended this to scalable development environments, emphasizing agent lifecycles and interoperability. These systems laid foundational abstractions for agent lifecycle management and communication, as seen in the FIPA Agent Communication Language (ACL) [

6], which standardized message passing and negotiation semantics. However, pioneering efforts targeted symbolic or

rule-based agents, focusing on service composition rather than today’s

LLM-centric,

tool-using,

multi-modal agents that must orchestrate models, data, UI actions, and environments with enterprise-grade observability and governance.

Conceptual proposals have bridged this gap by reimagining OS paradigms for AI. For instance, "LLM as OS, Agents as Apps" [

4] envisions LLMs as kernels with natural language as the interface, positioning agents as applications atop this substrate. This idea influences recent prototypes like AgentStore [

9], an "app store" for heterogeneous agents using a MetaAgent for task delegation, improving OSWorld benchmark performance from 11% to 24%. KAOS [

8], built on Kylin OS, introduces management-role agents for resource scheduling and vertical collaboration, enhancing multi-agent efficiency in dynamic settings. MMAC-Copilot [

13] extends this to multimodal domains, using collaborative chains to reduce hallucinations in GUI and game interactions, boosting GAIA benchmarks. Emerging 2025 works, such as Planet as a Brain [

14], extend AIOS to distributed "AgentSites" for agent migration; Alita [

15] enables autonomous reasoning via a generalist OS; Eliza [

16] integrates blockchain for decentralized security; and surveys like Fundamentals of Agentic AI [

1] and Large Model Agents [

2] highlight cooperation paradigms. AgentScope [

12] provides middleware roots for scalable simulations, while AI Agents Under Threat [

3] critiques security vulnerabilities in agent ecosystems. A Survey on MLLM-based Agents [

17] reviews device-use applications, referencing OS-level support for real-time interactions.

Taken together, these strands signal momentum toward OS-like abstractions, yet they also expose limitations: many works are preprint or product-driven with uneven empirical grounding, benchmarks rarely capture real-time and security constraints, standardization (MCP/A2A/OTel) and portability remain incomplete, and few proposals articulate a requirements-driven, latency-class- and security-by-design operating model suitable for audited, heterogeneous deployments.

On the other hand, Industrial efforts parallel these, with PwC Agent OS [

18] acting as a "switchboard" for cross-platform orchestration, integrating GPT-5 and clouds like AWS/Oracle. AG2 [

19] focuses on the multi-agent lifecycle from DeepMind, while Microsoft’s Copilot Runtime [

20] exposes local models via Phi Silica, and Apple’s Intelligence [

21] formalizes app intents. Standardization protocols like MCP [

22], A2A [

23], and OpenTelemetry [

24] enable tool access, inter-agent communication, and observability.

Critically, this literature reveals fragmentation: historical systems are outdated for LLMs, conceptual works lack implementation rigor, and prototypes prioritize efficiency over comprehensive governance. Real-time support is ad-hoc—e.g., Siren [

10] targets autonomous systems but not AI agents—while security surveys expose misuse risks without unified solutions. Workflows like Yu and Schmid’s framework [

25] model roles but ignore latency diversity. Weyns et al. [

26] define agent-based OS abstractly, yet miss modern scalability.

AIOS comparison. The most salient comparison is with AIOS [

7], a pioneering LLM-specific OS with a three-layer architecture (application, kernel, hardware) and managers for scheduling, context, tools, and access. AIOS reports ∼2.1× faster execution via unified system calls and an SDK, and introduces context-interrupt mechanisms for fairness. However, AIOS is primarily scoped to LLM agents, rather than a broader agentic ecosystem (e.g., multimodal environments and deep human-in-the-loop orchestration). Its requirements remain implicit, without a prioritized FR/NFR breakdown or data/ governance schemas. Real-time is addressed through latency reductions but not formalized into classes (HRT/SRT/DT) with enforceable SLOs, limiting applicability to safety-critical settings. Human-In-The-Loop (HITL) support is basic (user confirmation of risky actions), and the protocol surface is runtime-internal, rather than aligned to open standards such as MCP and A2A. his exposes a key gap: no unified, requirements-driven architecture supports latency-differentiated, portable agents with zero-trust governance across domains.

Table 1 summarizes the similarities and differences between the visionary “LLM as OS” proposal, the academic

AIOS prototype, and our generalized

Agent-OS, highlighting scope, architectural layers, requirements detail, real-time support, HITL integration, and standardization philosophy.

Our contribution fills this gap with a five-layer Agent-OS model and an explicit, requirements-driven specification (FR/NFR, including NFR7 for real-time), an Agent Contract for portability, and security-by-design as a kernel primitive (RBAC, capability-scoped tools, encrypted memory, auditable traces), yielding a scalable, interoperable framework for real-time AI in smart-city and enterprise contexts.

3. Requirements for an Agent Operating System

An Agent Operating System (Agent-OS) elevates agent-centric computation to a first-class platform abstraction, much as traditional operating systems virtualize hardware. Our specification is system engioneering requirements-driven and grounded in multi-agent systems (facilitation, lifecycles, messaging) [

5,

6,

25,

26], LLM-era systems (AIOS, KAOS, AgentStore, MMAC-Copilot) [

7,

8,

9,

13], real-time OS insights [

10], and surveys on large-model agents and risks [

2,

3].

In this section, we formalize the requirements for an Agent-OS, detailing functional and non-functional properties, introducing three latency classes—Hard Real-Time (HRT), Soft Real-Time (SRT), and Delay-Tolerant (DT)—with service-level objectives (SLOs), and stating measurable acceptance criteria that form a portable contract between application builders and platform providers. We organize the requirements into Functional (FR), Non-Functional (NFR), and Latency Classes. FRs cover lifecycle; context, memory, and knowledge; tools and environment access; orchestration; observability; safety and governance; model, cost, and placement management; interfaces and human-in-the-loop (HITL) surfaces; and multitenancy—each with stated interfaces (what is exposed) and acceptance (how verified). NFRs set targets for reliability, performance, security-by-design, scalability, interoperability, operations, and compliance. The latency classes attach concrete SLOs and map to robotics (HRT), speech/video assistants (SRT), and batch analytics (DT).

3.1. Functional Requirements (FR)

The functional requirements define what an Agent Operating System (Agent-OS) must provide to make agents reliable, scalable, and safe across diverse environments. Each requirement is expressed in plain terms, describes what the OS must offer, and sets measurable acceptance criteria, with examples that connect to LLM- and agent-centric applications (e.g., prompts, function-calling tools, vector stores, and RAG).

FR1—Agent lifecycle & scheduling.

Plain goal: Agents are easy to start, pause, resume, checkpoint, migrate (where allowed), and stop; many agents remain fair and responsive under load.

What the OS provides: A unified lifecycle manager for agent definitions (prompt/policy, plan, tool scopes) with APIs for spawn/pause/resume/kill; deterministic checkpoints that capture prompt state, scratchpad, tool cursors, and the context window; quotas and admission control; schedulers aware of token-rate budgets and model-gateway capacity (tokens per minute/second, TPM/TPS).

Why it matters: Prevents duplicated side effects after failures and preserves user trust during bursts.

Good enough if: ≥99% of agents recover within 60 s with no duplicate side effects; quotas enforced; a turn (prompt → completion → tools) replays deterministically under the same policy/seed.

LLM signals: Turn replay fidelity; tokenizer state saved in checkpoints; TPM/TPS budgeting per tenant/agent.

Example: A city-services assistant resumes after a reboot and finishes filing the same ticket without re-submitting the form.

FR2—Context, memory, and knowledge.

Plain goal: Agents have short-term working memory and long-term knowledge they can recall and cite.

What the OS provides: A context manager for LLM context windows (token-budget enforcement, sliding/summarization), episodic logs, and semantic long-term memory via pluggable backends (vector stores for embeddings, key–value caches, relational/object databases). Built-in RAG pipelines (retrieve → rank → ground) with citation/provenance and per-tenant namespaces.

Why it matters: Grounded recall reduces hallucinations and enables audits.

Good enough if: Context never exceeds max_context_tokens; RAG recall@K and citation coverage meet targets; memory growth stays within retention/redaction policies.

LLM signals: max_context_tokens, RAG hit-rate, attribution coverage, summarization drift checks.

Example: A planning agent embeds incident reports into a vector store and retrieves top-k sources with citations before proposing actions.

FR3—Tools & environments (action layer).

Plain goal: Agents safely invoke tools (APIs, apps, filesystems, IoT/robotics) with the right permissions.

What the OS provides: A typed tool registry with JSON/function-calling schema validation, capability-scoped permissions, secret redaction, and sandboxed execution; adapters for web/desktop automation, data platforms, and robot drivers; simulation mode for dry-runs.

Why it matters: Tool misuse is the main path to harmful side effects.

Good enough if: ≥99% schema-conformant calls; out-of-scope tools blocked and logged; tool sequences replayable for audit.

LLM signals: Function-call schema pass rate; scope-denial count; redaction events; per-tool round-trip latency.

Example: A maintenance agent reads a BACnet sensor and files a ticket, but is blocked from initiating payments it lacks scope for.

FR4—Orchestration & multi-agent coordination.

Plain goal: Coordinate complex jobs across agents and workflows; include people when needed.

What the OS provides: A workflow engine (DAG or state machine), planners/routers for agent-to-agent delegation, retries and idempotency with compensation, and human-in-the-loop (HITL) gates with prompt templates for approvals/corrections.

Why it matters: Long tasks fail without retries and human checkpoints.

Good enough if: Exactly-once semantics across retries; HITL actions complete within SLOs; delegation preserves tool/policy scopes end-to-end.

LLM signals: Prompt/plan template versions; HITL latency; delegation audit trail.

Example: A permitting workflow pauses for approval, then resumes a “draw-contract” agent with the approved prompt template.

FR5—Observability.

Plain goal: Operators can see what agents did, why, and how they performed.

What the OS provides: Structured logs, traces, and metrics with correlation IDs per task/turn; lineage from inputs/prompts through tool calls to outputs; LLM metrics (first-token onset, tokens/sec, prompt/completion token counts) and per-tool latencies; retrieval diagnostics (hit-rate, source hashes).

Why it matters: Debuggability and compliance depend on end-to-end visibility.

Good enough if: >99% of steps have trace spans; audits can reconstruct a run (with redactions).

LLM signals: onset_ms, tokens/sec, token counts, RAG source list, tool timings.

Example: Investigators replay a financial agent’s report with full provenance of RAG sources and tool timings.

FR6—Safety, security, and governance.

Plain goal: Prevent misuse, enforce least privilege, and record actions for accountability.

What the OS provides: Zero-trust RBAC (role-based access control) and capability scoping for tools/data; consent prompts for high-risk actions; tamper-evident audit logs; strict tenant isolation; defenses against prompt injection/jailbreaks and data exfiltration (content filters, allowlists, output redaction).

Why it matters: LLMs can be steered by crafted prompts; audits must hold up.

Good enough if: Unauthorized actions are blocked and logged; audit integrity is provable (hash/attestation); injection deflection meets target.

LLM signals: Injection block-rate; consent-gated action count; audit hash chain health.

Example: A data agent cannot paste credentials from its prompt into outbound emails; attempted exfiltration is blocked and recorded.

FR7—Model, cost, and placement management.

Plain goal: Automatically choose the right model/back end, balancing cost, latency, accuracy, and privacy.

What the OS provides: A model catalog (local/edge/cloud; base or fine-tuned; adapter/LoRA—low-rank adaptation—variants) with policy-based routing by context length, safety tier, and data residency; budgets/metering (tokens, currency) and placement controls (e.g., keep PHI—protected health information—on-prem); consistent tokenization contracts.

Why it matters: Cost and privacy constraints vary by tenant and task.

Good enough if: Routing complies with policy; budgets enforced with alerts; no privacy-class violations.

LLM signals: Model selection logs, budget adherence, privacy/placement decisions.

Example: A medical chatbot uses an on-prem 8B model for PHI and escalates to a 70B cloud model only when context exceeds local limits (with de-identified snippets).

FR8—Interfaces & HITL surfaces.

Plain goal: Agents are easy to integrate and supervise.

What the OS provides: Programmatic SDK/REST; a conversational “chat-as-shell”; multimodal I/O (speech, vision, screen, files) with streaming partials and barge-in (interrupt); reviewer consoles to edit prompts, plans, and tool scopes.

Why it matters: Human oversight reduces risk and improves UX.

Good enough if: Interactive turns meet onset/turn SLOs; reviewers intervene within SLA with full context and diffs.

LLM signals: First-token onset, turn latency, reviewer action latency, diff history.

Example: A video assistant streams captions within 200 ms first-token onset while a supervisor amends the prompt template live.

FR9—Multitenancy & portability.

Plain goal: Many teams safely share the platform; agents move across compliant runtimes without code changes.

What the OS provides: Strong isolation of data/logs/memory/keys per tenant; organizational policy inheritance; an exportable Agent Contract (prompt/policy templates, tool schema scopes, model/placement policy, budgets) for portability.

Why it matters: Portability reduces lock-in and eases cross-site deployments.

Good enough if: Isolation tests always pass; the same Agent Contract runs unchanged across reference runtimes with identical behavior/SLOs.

LLM signals: Contract fields (prompt templates, tool scopes, routing policy, budgets) validate across runtimes.

Example: A government agency exports an Agent Contract from a private cluster and replays it on a city-scale cloud deployment, preserving tool scopes and RAG policies.

3.2. Non-Functional Requirements (NFR) — Accessible, LLM-Aware

NFR1—Reliability and availability.

Target: The platform control plane (the service that schedules and supervises agents) provides at least 99.9% monthly availability; recovery time objective (RTO) is ≤60 s with idempotent replay of the last turn (prompt, model completion, and tool calls); automatic failover to a healthy model endpoint without losing the conversation state.

Why it matters: Conversational services and autonomous loops should not stall when a controller or model endpoint fails.

LLM signals: Replays preserve the context window and tokenizer state; side effects (e.g., tool calls) are not duplicated on retry.

NFR2—Performance and efficiency.

Target: Orchestration overhead at the 95th percentile (P95) is ≤200 ms (excluding model and tool execution). For interactive use, first-token onset (time to the first streamed token) is <1 s; for batch jobs, processing rate reaches at least 90% of the baseline tokens-per-second per core when batching is enabled.

Why it matters: People notice delays in conversations; background analytics must deliver good throughput and low cost.

LLM signals: Record onset time, tokens per second, and prompt/completion token counts; track RAG cache-hit rates and round-trip time for function/tool calls.

NFR3—Security by design.

Target: Single sign-on (SSO) with OpenID Connect, managed secrets, encryption in transit and at rest, capability-scoped tool access, tamper-evident audit logs, data-loss-prevention (DLP) and redaction for personally identifiable information (PII), and a prompt-injection/jailbreak deflection rate ≥95% on a standard test suite.

Why it matters: LLMs can be steered by crafted prompts; sensitive data must not leak.

LLM signals: Strict validation of function-calling/JSON schemas; input/output safety filters; signed tool manifests and proof that each call stayed within its declared scope.

NFR4—Scalability and elasticity.

Target: Horizontal scale-out of agent runtimes and model gateways; autoscaling based on queue depth and measured tokens-per-second; graceful degradation with back-pressure under load.

Why it matters: Real-world traffic is bursty (events, end-of-month reports, civic surges).

LLM signals: Shardable vector stores for embeddings; limits on concurrent sessions; fair token-rate limits per tenant and per agent.

NFR5—Interoperability and extensibility.

Target: Plugin/adapter model with versioned contracts; protocol-agnostic interfaces for tools and telemetry; backward compatibility for agent “contracts”.

Why it matters: Avoids vendor lock-in and supports mixed fleets of local and cloud models.

LLM signals: Model Context Protocol (MCP)–style tool contracts; adapters for different model providers (open-source and commercial); consistent function-calling schemas; portable prompt/plan templates.

NFR6—Operations.

Target: Health probes, circuit breakers, staged “canary” releases, documented runbooks, and policy dry-runs; service-level objective (SLO) dashboards and error budgets with continuous evaluation (CE) pipelines.

Why it matters: Models, prompts, and data drift over time; safe rollouts require guardrails.

LLM signals: CE on representative tasks (e.g., RAG Q&A, tool-use flows); automatic alerts on regressions in accuracy, safety, or cost; “shadow” routing to trial a new model without affecting users.

NFR7—Real-time responsiveness.

Target: Meet class-specific objectives—deadlines and jitter for Hard Real-Time (HRT), onset and full-turn latency for Soft Real-Time (SRT), and throughput/cost SLAs for Delay-Tolerant (DT)—and automatically reject deployments that fail a pre-deployment schedulability check.

Why it matters: Robots need determinism; people expect instant feedback; batch jobs must be efficient.

LLM signals: HRT pins models on device and avoids garbage collection in control loops; SRT enforces first-token and turn-time SLOs with streaming partials and “barge-in”; DT optimizes cost-per-token with resumable checkpoints.

NFR8—Compliance and governance.

Target: Retention and redaction controls, data-residency modes, end-to-end lineage for audits, separation of duties, and policy attestation.

Why it matters: Public-sector, healthcare, and enterprise settings require provable control and traceability.

LLM signals: Source attribution for generated claims; per-turn provenance (retrieved documents, embeddings, and tools used); audit logs are hashed/attested; “privacy classes” drive model choice and data placement.

3.3. Latency Classes (Time Semantics)

We classify agent workloads into three latency classes so the OS can apply the right scheduling, I/O, memory, and testing policies. We use the following terms: deadline (time by which a task must finish), deadline miss (task finishes after its deadline), jitter (variation in completion/onset time), WCET (worst-case execution time), onset latency (time to first token/response), and full-turn latency (time to complete an interaction).

Hard Real-Time (HRT) — deterministic and safety-critical.

Definition: Correctness depends on meeting every deadline; any miss is a system failure.

Why it matters: Some LLM-driven agents embed models inside closed-loop control pipelines (e.g., drone navigation, medical devices, factory lines). A late token or missed tool call could break synchronization and lead to unsafe or invalid actions.

Typical use cases: Token-bounded inference loops for robotics, “LLM + control policy” hybrids where the LLM interprets high-level goals, and real-time safety checks on generated actions.

Targets (SLOs): 1–20 ms execution slices; jitter ≤5 ms; zero deadline misses.

OS policies: EDF/RM scheduling; CPU/GPU/NPU reservations; pinned threads; fixed memory arenas (no GC); lock-free queues.

LLM anchors: Bounded context templates, capped output tokens, pre-validated tool paths, and lightweight local models for deterministic latency.

Acceptance: WCET profiling and 24h burn-in tests with 0 deadline misses [

10].

Example: A warehouse robot uses an LLM agent to interpret human commands (“pick from aisle 3”) but runs them through an HRT safety filter that must always respond in <10 ms before execution.

Soft Real-Time (SRT) — interactive and perceptual.

Definition: Occasional deadline misses are tolerable, but user-perceived responsiveness is crucial.

Why it matters: In LLM copilots (speech/video/chat), humans abandon interactions if responses feel delayed or jittery. First-token onset and smooth streaming are as important as accuracy.

Typical use cases: Conversational assistants, meeting summarizers, screen copilots, live captioning, multi-modal copilots.

Targets (SLOs): Onset (time-to-first-token) 150–300 ms; full-turn 0.8–1.2 s; jitter P95 ≤20%.

OS policies: Priority-queue scheduling; streaming partial completions; barge-in support; adaptive buffering; rolling context caches.

LLM anchors: TTFT (time-to-first-token), tokens/sec throughput, function-call round-trip times, RAG latency budgets (≤150 ms retrieval, ≤100 ms grounding).

Acceptance: Turn-level latency distributions; MOS for quality; network impairment tests.

Example: A real-time translator must show the first translated words within 200 ms while continuing to stream the rest of the sentence smoothly.

Delay-Tolerant (DT) — throughput and cost first.

Definition: Deadlines are coarse (minutes–hours); efficiency and completion rate dominate responsiveness.

Why it matters: LLM workloads like RAG sweeps, indexing, retraining, or batch question-answering do not need instant responses. The priority is minimizing cost-per-token and maximizing throughput while ensuring reproducibility.

Typical use cases: Overnight batch summarization, legal document RAG indexing, dataset labeling, long code refactoring pipelines.

Targets (SLOs): SLAs in minutes–hours; maximize throughput (tokens/sec and tasks/hour) per dollar while meeting accuracy/completeness targets.

OS policies: Queue-based best-effort scheduling; preemptible/low-priority workers; aggressive batching/prefetch; resumable checkpoints; idempotent retries.

LLM anchors: Embedding throughput, batch tokens/sec, RAG cache hit-rates, checkpoint integrity, retry idempotency.

Acceptance: Throughput–cost curves; checkpoint/resume fidelity; no duplicate tool calls across retries.

Example: A compliance office runs an overnight RAG sweep of 10M documents; runtime batches maximize tokens/sec while ensuring results can resume after preemption.

Choosing a class. Use Hard Real-Time (HRT) for agents where any missed deadline means failure—these are safety- or stability-critical (e.g., control loops or rapid safety checks). Use Soft Real-Time (SRT) when humans are in the loop and the priority is smooth, responsive interaction (e.g., speech, chat, or video copilots). Use Delay-Tolerant (DT) for long-running or batch workloads that can trade speed for throughput and cost efficiency (e.g., RAG indexing, bulk summarization). The Agent-OS enforces tailored scheduling, I/O, memory, and verification policies for each class, ensuring that applications receive the performance guarantees appropriate to their domain.

3.4. Agent Contract (excerpt)

Purpose. The Agent Contract serves as the declarative definition for an agent. It is a portable, machine-readable specification that outlines an agent’s operational parameters, resource needs, behavioral guardrails, capabilities, policies, latency class, and service-level objectives (SLOs). As a critical component of the ecosystem, it enables the Agent-OS to (i) schedule and place the agent correctly, (ii) enforce security and governance, (iii) provision memory, RAG, and tooling consistently, and (iv) ensure the same behavior across compliant runtimes, guaranteeing both performance and compliance.

Minimal viable contract (illustrative Canonical schema).

apiVersion: agentos/v0.2

kind: AgentContract

name: doc-rag-planner

class: { latency: SRT, slo: { onset_ms: 250, turn_ms: 1000, jitter_p95_pct: 20 } }

capabilities: [ "web.fetch", "fs.read", "summarize" ]

compute: { cpu: "1", mem: "2GiB" }

modelPolicy: { allow: ["local/8B","cloud/70B"], max_context_tokens: 16000 }

memory: { namespace: "city-planning", retention_days: 30,

rag: { top_k: 8, require_grounding: true } }

security: { consent_for: ["fs.write","payment.charge"] }

observability: { tracing: "opentelemetry", log_fields: ["prompt","sources"] }

HRT variant (one-line change):

class: { latency: HRT, slo: { deadline_ms: 10, jitter_ms: 5 } }

How the OS uses it (at a glance).

Real-time enforcement (FR1, NFR7). The declared class.latency selects the scheduler and checks: HRT → EDF/RM with deadline/jitter admission tests; SRT → priority queues, streaming, barge-in; DT → best-effort queues. Unschedulable deployments are rejected at admit time.

Tools (FR3, FR6).capabilities is the allowlist; everything else is blocked or requires consent in security.consent_for.

Memory/RAG (FR2).memory fixes namespace, retention, and grounding rules; citations are required when require_grounding=true.

Models/placement (FR7).modelPolicy constrains model choice and context limits; routing enforces these when composing prompts/completions.

Compute budgets (FR1/7).compute informs admission control and prevents token/CPU starvation.

Audit/telemetry (FR5, NFR8).observability ensures prompts, sources, and tool hashes are traceable for audits.

Why this helps. The contract acts like an “ABI for agents,” coupling real-time class (HRT/SRT/DT) with concrete SLOs (deadlines, onset/turn, throughput) so the Agent-OS can prove schedulability up front and enforce class-specific policies at runtime—while keeping behavior portable across vendors and clusters.

4. Conceptual Architecture

We propose a layered architecture for an Agent Operating System (Agent-OS) that treats models, tools, environments, and human-in-the-loop (HITL) interactions as first-class, schedulable resources. The design is guided by two complementary goals: systems rigor and ecosystem portability.

On the systems side, Agent-OS adopts a

microkernel-style control plane that enforces

real-time guarantees,

admission control, and

policy checks. Responsiveness is explicitly managed through three latency classes—

hard real-time (HRT),

soft real-time (SRT), and

deferred-time (DT)—each associated with

service-level objectives (SLOs) and validated via

pre-deployment schedulability tests [

10].

On the ecosystem side, the architecture embraces open and interoperable standards. Tool interfaces follow MCP-style descriptors, inter-agent communication is enabled via an A2A-like message bus, and observability is integrated with OpenTelemetry (OTel) to support unified tracing across heterogeneous components.

A central abstraction in this design is the Agent Contract, which serves as an application binary interface (ABI) for agents. The contract binds an agent’s declared capabilities, latency class, SLOs, memory/model policies, and resource budgets to its runtime execution profile. This provides both predictability for the system and portability for agents across deployments.

4.1. Design Principles

Keep the kernel minimal (microkernel). The secure “core” of the Agent-OS should stay small and easy to audit. Only the essentials live in the kernel: checking whether an agent can be admitted, scheduling according to latency class, managing minimal context, and enforcing policies. All richer services—such as memory/RAG, tool use, model routing, agent-to-agent messaging, and telemetry—are implemented outside the kernel as modular services with versioned contracts. This separation makes the system both safer and more flexible.

Schedule by class of workload. Different agents have different timing needs: some need hard real-time guarantees (HRT), some need interactive smoothness (SRT), and some can run in the background with a focus on cost efficiency (DT). The kernel enforces these service-level objectives (SLOs) end-to-end by picking the right scheduler (e.g., EDF/RM for HRT, priority queues for SRT, best-effort for DT), reserving resources, and checking each agent’s declared contract before it is admitted.

Zero-trust execution. Agents only get the exact data and tools they declare in their contract. Every call is checked against policy and logged. Sensitive or high-risk actions always require explicit human approval. This ensures safety and accountability, even if an agent is compromised or misconfigured.

Portable and open interfaces. Agents should run on different runtimes without rewriting. To achieve this, the OS uses open standards and versioned contracts: tools are described in schema-based formats (MCP-like), agents talk to each other through structured messages (A2A-style), and all activities are traced in standard telemetry formats (OTel). If an interface changes, it is versioned so old agents continue to work. This guarantees portability, interoperability, and long-term stability.

4.2. Layered Model

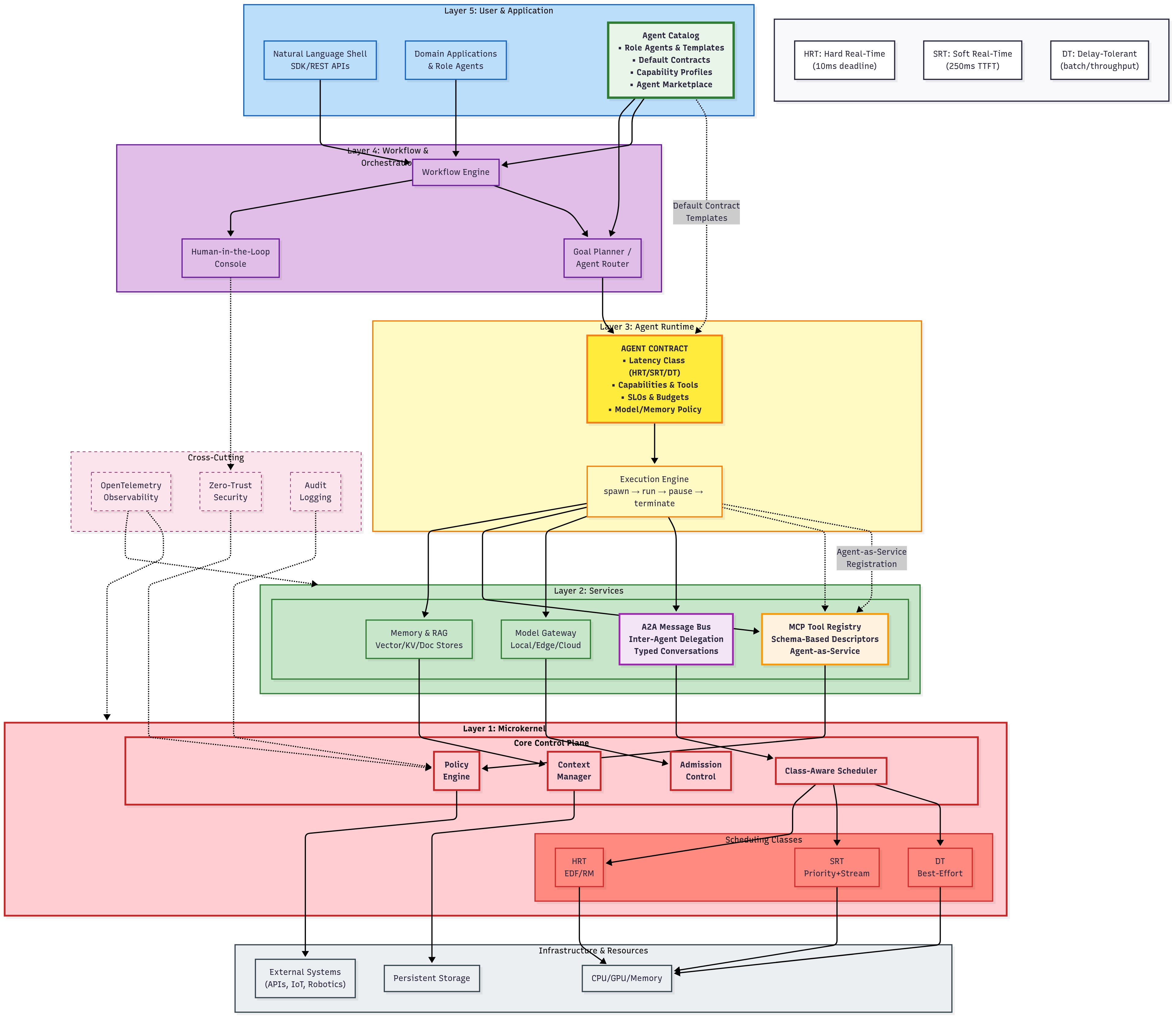

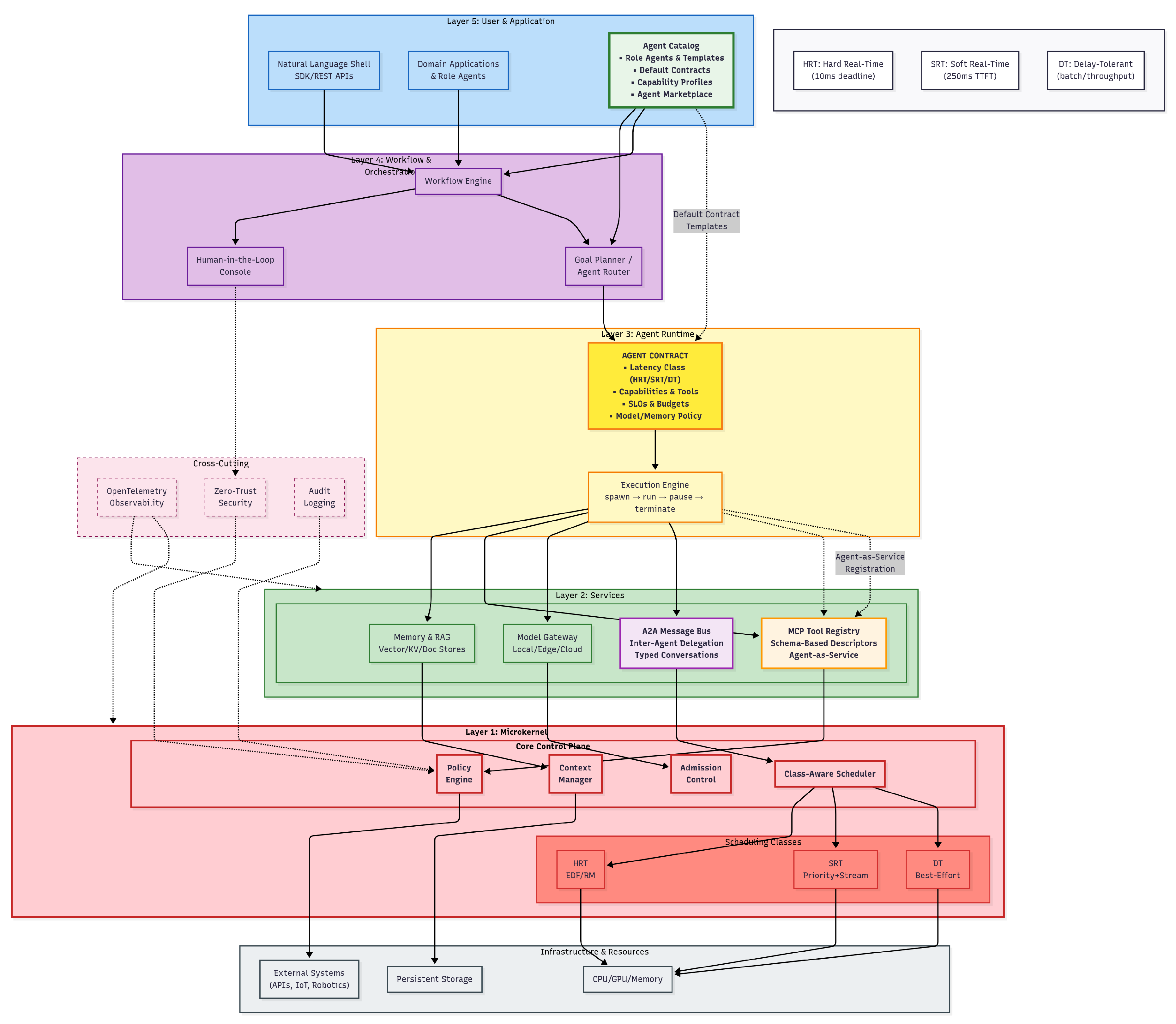

The proposed Agent-OS employs a five-layer architecture that parallels classical operating systems while targeting agentic workloads, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Following the principle that each layer should do one job well with a stable interface, the system uses a machine-readable

Agent Contract as its single source of truth—specifying capabilities, data/tool access, latency requirements (HRT/SRT/DT), and budget/policy constraints across all layers. The

User and Application layer defines contracts and task objectives, which the

Workflow and Orchestration layer decomposes into executable steps with per-step contracts delegated to specialized agents. The

Agent Runtime instantiates these agents, maintains conversation state, and creates checkpoints for recovery. Acting as the system’s enforcement mechanism, the

Kernel validates each step against its contract, manages real-time scheduling, and mediates all resource access. The

Services layer implements concrete operations—memory/knowledge management (embeddings, indexing, retrieval), tool execution via MCP, model routing, and inter-agent messaging—while

Observability captures OpenTelemetry traces and lineage data that flows upward for auditing and optimization.

Table 2 maps these components to their classical OS counterparts, demonstrating how traditional OS concepts extend naturally to agent coordination.

(1) User & Application layer

This is where end-users and upstream systems invoke the Agent-OS ecosystem (

Figure 1, top). Users may type or speak requests in a natural-language shell and developers integrate via SDKs/REST.

LLM agents are selected here as first-class application components: an

Agent Catalog exposes role agents (e.g., “city-services assistant”, “RAG summarizer”) packaged with default

Agent Contracts (capabilities, latency class, budgets, policies, prompt/plan templates). Each request is bound to a concrete contract—either the catalog default or an application override—and this binding travels with the request to drive scheduling, security, and routing in lower layers. This layer emphasizes usability and portability; enforcement and timing are delegated downstream.

(2) Workflow & Orchestration layer

User intents are compiled into agentic workflows: DAGs/state machines whose nodes are LLM-agent invocations and whose edges carry typed data and control. The orchestrator selects specialists from the Agent Catalog, binds each step to an Agent Contract, and composes them into a plan (e.g., Planner→BrowserAgent→DocRAGAgent→Writer). Steps can invoke an agent either as a service (stateless call with inputs/outputs) or as an instance (stateful session). Human-in-the-loop gates are inserted at risky transitions according to contract policy. Inter-agent delegation uses the Agent-to-Agent (A2A) bus with typed messages (conversation IDs, performatives), enabling marketplace, hierarchical, or blackboard patterns.

Dependencies: Orchestration instantiates or calls agents via the Runtime; any step that hits data, tools, or models must cross the Kernel (policy/scheduling) before reaching Services.

(3) Agent Runtime layer

This is where LLM agents reside and execute. An agent is materialized from its Agent Contract (capabilities, latency class/SLOs, model/memory policy, budgets, prompt/plan templates). The Runtime provides lifecycle primitives (spawn/pause/resume/checkpoint/terminate) and maintains per-turn state (prompt, tokenizer cursor, scratchpad, pending tool cursors). It supports (i) single-shot calls (agent-as-service), (ii) stateful sessions for interactive tasks, (iii) batch pipelines, and (iv) small guarded control loops. Checkpoints are deterministic (seed, policy, tool sequence) to enable replay after faults or migration. Agents can also be exposed to others “as tools”: the Runtime registers an agent’s service interface in the Tool registry so that another agent can invoke it via standard function-calling semantics. All external actions (tools, memory, model calls) are made through kernel-mediated invocations to ensure contract SLOs and scopes are enforced.

(4) Services layer

Agents consume shared services behind stable, replaceable APIs. Memory, also referred as Knowledge base, exposes a single API over pluggable backends (vector / KV / relational / object stores) and provides core primitives for embedding, indexing, retrieval, reranking, and citation/provenance with per-tenant namespaces, retention, and redaction. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is supported as one composition pattern (retrieve → generate → verify/attribute), rather than being the mechanism itself; the same primitives also serve planning, tool selection, and analytics.

The Tool service maintains an MCP-style typed registry for safe actions over apps, data, and devices; validates JSON/function-call schemas; scrubs secrets; and executes tools in sandboxes via adapters for web/desktop automation, data platforms, and robotics/IoT (with a simulation mode for dry runs). Agents published “as tools” appear here as well, enabling agent-as-a-service composition without bypassing policy.

The A2A bus transports typed inter-agent messages (conversation IDs, performatives) for delegation and coordination. The Model gateway routes across local/edge/cloud models (base, fine-tuned, adapter/LoRA variants), enforces placement/privacy (e.g., PHI on-premises), preserves tokenization consistency and max-context limits, and reports LLM metrics such as time-to-first-token (TTFT) and tokens/sec.

Observability exports OpenTelemetry (OTel) traces/logs/metrics and maintains end-to-end lineage from prompts and retrieved sources to tool arguments and outputs.

This layer maintains a dependency with the Kernel layer as Services call the Kernel’s policy engine for capability checks and consent gates, and expose narrow “driver-like” interfaces so implementations can be swapped without breaking contracts.

(5) Kernel layer

The Kernel is the small, trusted control plane on the hot path of all sensitive operations. Admission control validates each Agent Contract (latency class/SLOs, compute reservations, capabilities) and rejects unschedulable or under-scoped deployments a priori. Class-aware scheduling enforces timing semantics: Earliest Deadline First/Rate-Monotonic with reservations for hard real-time (HRT); priority queues with burst credits and streaming for soft real-time (SRT); and preemptible, best-effort queues for delay-tolerant (DT). Context primitives bound the LLM context window and provide checkpoint/rollback hooks. A policy engine applies zero-trust RBAC/capability checks, triggers consent for high-risk actions, and appends signed, tamper-evident audit records. All tool invocations—including agent-as-tool calls—traverse the Kernel using MCP-typed contracts, ensuring uniform enforcement. In terms of dependencies, every layer above issues requests that cross the kernel boundary; the Kernel dispatches to Services only after timing and policy checks succeed.

Layer inter-dependencies As shown in

Figure 1, control flows

downward

(User→ Orchestration → Runtime →Kernel→ Services).

LLM agents live in the Runtime, are invoked by Orchestration, and compose via two mechanisms: (i.) A2A messaging for delegation/coordination and (ii.) agent-as-service via the Tool registry (MCP schemas). Telemetry and provenance flow upward

(Services/Kernel→Observability→Orchestration/User).

The Agent Contract is the shared source of truth: attached at the User layer, compiled and propagated by Orchestration, bound at instantiation by the Runtime, enforced by the Kernel, and honored by Services. MCP provides portable schemas for discovery and invocation; A2A provides portable agent messaging; OTel provides portable traces and metrics. This yields an implementation-agnostic yet enforceable path from user intent to audited effect, with explicit HRT/SRT/DT timing guarantees and security-by-design across the stack.

Relation to a classical OS. Table 2 maps familiar OS ideas to their Agent-OS counterparts (e.g., a system call becomes a safe tool invocation; inter-process communication becomes agent-to-agent messaging; virtual memory becomes managed context and knowledge). This analogy helps practitioners reuse well-understood systems principles while working with LLM-driven agents.

4.3. Service Composition and Orchestration of Multi-Agent Applications

Composition is a main responsibility of the

Workflow & Orchestration layer (

Figure 1). This layer turns user intents into typed (i.e. schema-driven plan) and coordinates concrete agent invocations through the

Agent Runtime, while all sensitive operations (tool calls, memory/model access) traverse the

Kernel for scheduling and policy checks and use the

Services layer for memory/knowledge, tools, models, and telemetry.

How composition works (control plane).

A workflow is a typed graph (i.e. schema-constrained graph like DAG or state machine) whose nodes are steps and edges carry artifacts (e.g., documents, JSON facts, embeddings). Each step binds an Agent Contract (capabilities, latency class, policies, budgets) and declares input_schema/output_schema. Binding supports two modes: (i) strict (contract must match exactly; reject otherwise), and (ii) smooth (allow compatible upgrades within policy and capability envelopes). The orchestrator selects specialists (“planner”, “browser”, “summarizer”) and preserves least-privilege scopes across delegations.

How composition executes (data plane).

Within a step, an agent performs work by issuing tool calls using MCP-style schemas— similar to how programs make system calls to an operating system. When agents need to coordinate with each other, they send typed messages through the A2A bus (which includes conversation IDs and message types), supporting different coordination patterns like hierarchical control, marketplace negotiations, or shared blackboard systems. Every call passes through the Kernel layer, which acts as a gatekeeper—checking that the requested action matches its declared speed requirements (hard real-time, soft real-time, or deferred), stays within resource limits, and follows security policies before routing it to the appropriate Service.

Semantics and guarantees.

The orchestrator ensures each step runs exactly once by using unique step identifiers, detecting duplicates, and implementing SAGA-style rollback procedures when things go wrong. When human approval is needed (human-in-the-loop gates), the system treats these as special blocking steps with built-in timeouts and escalation procedures if no response arrives. The system maintains real-time performance throughout by tagging each step (and its agent) with speed requirements and pre-allocating necessary resources—if a plan cannot meet its timing requirements, it is rejected before it even starts. Complete tracking connects everything together—from initial prompts to retrieved information to tool inputs and final outputs—using OpenTelemetry traces and data lineage records.

Agents as services.

Agents can be packaged and shared as tools through the Tool Service using MCP-typed interfaces, creating an agent-as-a-service model that maintains full policy enforcement and tracking. This means a workflow step can invoke another agent just like calling any regular tool—the calling agent doesn’t need to know it’s actually another agent—while the Kernel still enforces all security rules and resource limits for the original caller.

Concise example.

workflow: city_permit_assistant

steps:

- id: plan

agent: planner

bind: smooth

contract: { latency_class: SRT, capabilities: [ "tools.plan" ] }

in: { user_query: string }

out: { plan: json }

- id: browse

agent: browser_agent

bind: strict

contract: { latency_class: SRT,

capabilities: [ "web.fetch" ],

policies: { allow: ["web.fetch"], deny: ["fs.write"] } }

in: { plan: json } # selected URLs from planner

out: { pages: [html] }

- id: summarize

agent: doc_rag_planner

bind: smooth

contract: { latency_class: SRT,

capabilities: [ "rag.retrieve", "summarize" ],

budgets: { tokens: 50k } }

in: { pages: [html] }

out: { answer: markdown, citations: [uri] }

- id: approve_send

type: HITL_approval

policy: { consent_for: ["email.send"] }

in: { answer, citations }

4.4. Contract Binding Semantics: Strict, Smooth, and Flexible

Goal. Not all deployments can satisfy an Agent Contract verbatim (e.g., a preferred model is unavailable or a privacy rule forces on-prem placement). We therefore distinguish three binding modes that preserve safety and auditability while improving practicality: strict (hard adherence), smooth (progressive, version-compatible upgrades), and flexible (policy-bounded substitutions and fallbacks).

Strict binding (reject on mismatch).

When safety or compliance is paramount, contracts become immutable specifications. The system treats every requirement—latency guarantees, data locality, specific capabilities—as non-negotiable. If even one constraint cannot be satisfied, the Kernel immediately rejects deployment rather than risk violation. This zero-tolerance approach protects high-stakes operations like financial transactions or medical diagnostics where "close enough" isn’t acceptable.

Smooth binding (progressive, version-compatible).

For long-running production systems, stagnation equals technical issues. This mode allows the orchestrator to automatically adopt newer, compatible versions of models and tools (within specified version ranges), using canary deployments to test changes on small traffic percentages first. The runtime continuously monitors key metrics (latency, throughput, accuracy)—if any degradation occurs, it instantly reverts to the previous stable configuration, ensuring improvements never compromise service quality.

Flexible binding (policy-bounded substitutions).

Most workloads benefit from pragmatic adaptation. When facing resource limitations, the orchestrator intelligently substitutes equivalent resources while maintaining core guarantees. For instance, if cloud-based speech recognition becomes unavailable, the system might switch to on-device processing—trading some accuracy for availability. Crucially, all substitutions require Kernel validation against security policies, and every decision is logged for audit trails, ensuring flexibility never compromises accountability or safety boundaries.

Hard vs. soft constraints. Contracts distinguish between must (hard) and prefer (soft) requirements. Hard constraints are inviolable—the system fails rather than compromises them. Soft constraints allow orchestrator-mediated tradeoffs under policy supervision. Critical aspects like latency class (HRT/SRT/DT), data privacy/placement, and high-risk capabilities (payment.charge, fs.write) are marked must. Resource preferences like model family, provider, or embedding store use prefer.

Binding algorithm (outline).

Normalize request: Merge configuration layers hierarchically (request override → role template → tenant policy → platform defaults).

Validate hard constraints: Reject immediately if any must requirement fails (e.g., HRT scheduling feasibility, mandated on-premise placement).

Resolve smooth upgrades: Select highest compatible versions within specified ranges; activate canary deployment with automatic rollback.

Apply flexible substitutions: Within prefer boundaries, optimize for cost/latency while maintaining SLOs; document reasoning in trace.

Seal binding: Generate immutable binding manifest containing selected model/tool versions, placements, and SLOs; attach to OpenTelemetry trace.

Minimal examples (illustrative).

# Strict binding for safety-critical operations

agent: "safety-kill-switch"

latency_class: HRT

must:

model: ["on_device_kwd_v3"]

placement: "edge-only"

deadline_ms: 10

capabilities: ["audio.detect_keyword", "agent.pause"]

# Smooth + Flexible for adaptive workloads

agent: "speech-copilot"

latency_class: SRT

must:

placement: ["on-prem", "edge"] # PHI compliance

prefer:

model: ["asr_local_v2..v3", "asr_cloud_v2"]

embed_store: ["vecdb_A", "vecdb_B"]

allow_fallbacks:

- when: "bandwidth_low"

substitute: { model: "asr_local_v2" }

- when: "context_exceeds_local"

substitute: { model: "llm_cloud_70B", redact: true }

4.5. Cross-Layer Responsibilities

Security and Governance

Security is enforced as a zero-trust property over LLM artifacts: prompts, plans, tool calls, retrieved passages, and outputs. Fine-grained role-based access control (RBAC) and capability scopes are checked on every function-calling request; high-risk tools (e.g., fs.write, payment.charge) require explicit human consent. Short-term context (prompt + scratchpad) and long-term memories (vector/KV/DB) are encrypted and, where required, attested. All privileged actions emit tamper-evident audit records that bind policy decisions to concrete items (prompt hash, tool manifest, source document IDs). This realizes FR6/NFR3/NFR8 for LLM agents without embedding ad-hoc checks in application code.

Multitenancy

Hard isolation covers agent context, embeddings, document indices, logs, and cryptographic keys. Organizational policy inheritance (e.g., department → team) allows central governance with scoped overrides. Isolation is validated by automated tests that replay representative LLM turns under tenant boundaries (FR9).

Operations

Health probes, circuit breakers, and canary releases keep the platform stable as prompts, models, and data drift. A continuous evaluation (CE) loop tracks accuracy, safety, and cost on representative LLM tasks (e.g., RAG QA, tool-use workflows), alerting on regressions (NFR6). Observability is standardized via OpenTelemetry (OTel) with end-to-end lineage that links inputs, retrieved chunks, tool arguments, and generated outputs (FR5).

Interoperability

Versioned contracts for agents, tools, and models—together with adapter SDKs—decouple agent logic from vendor runtimes. Deprecations follow explicit windows; portability is verified by replaying the same prompt/plan/tool sequence across compliant deployments with identical SLOs (NFR5).

4.6. End-to-End Flows with LLM Agents Examples

We illustrate the behavior of the proposed Agent-OS through three representative flows that correspond to different latency classes: soft real-time (SRT), delay-tolerant (DT), and hard real-time (HRT). Each flow highlights how contracts, execution semantics, and observability signals are expressed in LLM-centric terms.

Soft Real-Time (SRT): Speech Scheduling Copilot. In this flow, the agent contract specifies latency_class: SRT with a first-token target (TTFT) of ms and access to two tools: asr.transcribe and calendar.addEvent. Incoming speech is transcribed in a streaming fashion, and partial hypotheses are incrementally fed to the LLM. Within 250 ms, the model produces the first completion, proposing an event plan with required slots such as title and time. A retrieval step ensures grounding in user-specific constraints (e.g., working hours) by attaching relevant vector-store entries with citations. Before execution, the resulting tool call is displayed to the user for consent, with sensitive fields redacted. Upon approval, the event is committed and a confirmation is rendered through text-to-speech. Logs capture prompt fragments, retrieved document IDs, tool schemas, and detailed latency breakdowns. The key role of the LLM here is in enabling responsiveness through streaming, grounding via retrieval, and safety through typed function calls.

Delay-Tolerant (DT): Overnight RAG Indexing. In contrast, the DT flow targets throughput and cost efficiency rather than latency. The contract declares latency_class: DT with a budget of 3M tokens per hour and tools for file access (fs.read) and index updates (index.upsert). The orchestrator partitions the corpus into shards, which are normalized and embedded in parallel. Embeddings are batched and cached to maximize tokens processed per second, then upserted into the vector store with idempotent keys to guarantee repeatability. Quality assurance is performed by a lightweight LLM sampler that issues spot-check queries; shards with low recall are re-embedded. Observability focuses on throughput–cost curves, embedding cache hits, upsert idempotency, and recall@K. Here the LLM’s contribution is primarily in embedding and validation, with performance judged against cost SLAs rather than interaction latency.

Hard Real-Time (HRT): Speech-Guided Robot. The HRT case involves a mobile robot controlled through natural-language commands (e.g., “move forward two meters” or “stop”). Language understanding—comprising ASR, intent recognition, retrieval-based grounding, and plan generation—is managed by an LLM operating under an SRT contract. Safety, however, is guaranteed by an HRT loop with a declared period of 10 ms, deadline of 10 ms, and jitter ms. This loop is pinned to a dedicated core with fixed memory and no garbage collection, ensuring determinism. Every 10 ms the safety loop processes collision sensors and a keyword detector (e.g., “stop”) to produce a binary safe-to-move signal. The kernel authorizes motion only when both the HRT guard deems it safe and the LLM-proposed actuation path matches pre-validated schemas. Any hazard or keyword immediately triggers agent.pause, freezing the LLM turn and canceling pending tool calls. Verification includes worst-case execution time (WCET) analysis and a 24-hour burn-in with zero deadline misses. Runtime telemetry links LLM prompts, retrieved data, tool arguments, and HRT guard decisions, providing full auditability. This flow illustrates the necessity of combining SRT semantics for language-driven interaction with strict HRT enforcement for physical safety.

Overall, these three examples demonstrate how Agent-OS applies latency-aware contracts across diverse scenarios. The SRT copilot highlights responsiveness, the DT indexing pipeline emphasizes cost and throughput, and the HRT robot underscores deterministic safety. In all cases, the LLM is central, but its role is conditioned by the latency class and enforced by the operating system’s control plane.

4.7. Deployment Topologies (LLM-Aware)

An agent’s physical location—whether on a device, in the cloud, or on a private server—changes how it behaves. The Agent-OS is designed to manage agents across three common setups, ensuring that performance, security, and privacy are always handled correctly.

On the Device (Edge-Only)

This setup is for agents that need to be fast, private, and always available, even without an internet connection.

Everything runs directly on the user’s device (e.g., phone or laptop). For interactive tasks that require immediate responses (Soft Real-Time), a small, efficient on-device AI model is used. This allows near-instant replies and local speech-to-text processing. Less urgent background tasks (Deferred-Time) are postponed until the device is less busy. The Agent Contract enforces that all models and tools remain local, ensuring data never leaves the device and privacy is preserved.

A Mix of Device and Cloud (Hybrid)

This model combines the instant responsiveness of the device with the raw computing power of the cloud.

When a command is issued, a small local AI generates the first few words of the response immediately, reducing latency. The task is then handed off to a larger, more powerful cloud AI to finish the response, perform complex searches, or analyze large documents. The Agent Contract enforces placement and security rules—for instance, ensuring that sensitive data (e.g., health records) never leave the local environment.

Completely Offline (Air-Gapped On-Premises)

This is the maximum-security option, used by organizations that cannot risk any external connectivity (e.g., defense, finance, healthcare).

The entire Agent-OS runs on private servers inside the organization’s facilities. Only company-approved AI models and tools can be deployed. All data, documents, and logs remain securely on-site. Updates are carefully rolled out using canary releases, tested on a small portion of the system first. If any issue arises, the system automatically reverts to the previous stable version, guaranteeing reliability and continuity.

Regardless of deployment, the Agent Contract is the single source of truth. It defines the rules for speed, security, and capabilities, ensuring that every agent behaves predictably and safely across all environments.

4.8. Analogy: Traditional OS vs. Agent-OS

A useful way to situate the proposed architecture is by analogy with traditional operating systems (OS). Conventional OSs virtualize hardware resources—CPUs, memory, files, and devices—so that applications can run safely and efficiently without directly managing low-level details. Processes are the schedulable units, controlled by the kernel through lifecycle commands (spawn, pause, resume, terminate) and interacting via system calls and inter-process communication (IPC). The kernel enforces policies for priority scheduling, memory safety, protection, and access control, while observability relies on counters and I/O traces.

The Agent-OS extends this model upward to agentic workloads. Here, the schedulable entities are agents, each governed by an explicit contract that specifies latency class, service-level objectives (SLOs), capabilities, and budget constraints. Instead of syscalls, agents invoke tool calls, validated against declared scopes using Model Context Protocol (MCP)–style descriptors. IPC is replaced by Agent-to-Agent (A2A) messaging, which supports typed conversations for delegation and negotiation. Virtual memory maps to the context and knowledge layer, spanning short-term context windows and long-term vector stores, while file systems correspond to knowledge services for retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). Device drivers become tool and environment adapters for APIs, IoT devices, or robots. Finally, the OS shell is reimagined as a natural-language shell, enabling users to interact conversationally.

This analogy underscores both continuity and novelty: Agent-OS preserves the rigor of kernel-managed scheduling, isolation, and logging, while introducing abstractions tailored to LLM-centric execution.