3.1. The Classification Performance of Each Model on Each Data Augmentation

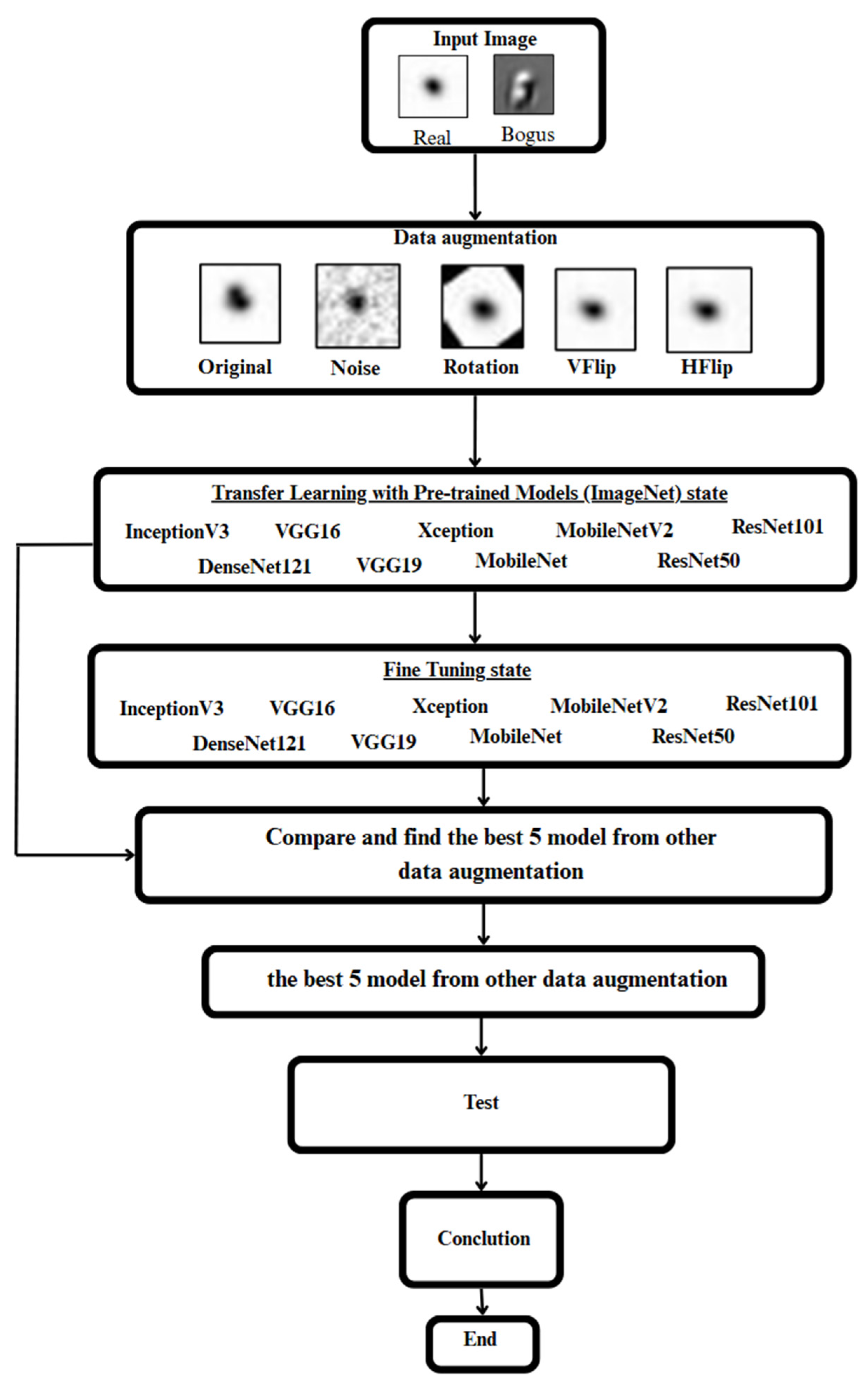

In this experiment, the training data consisted entirely of astronomical images augmented using Rotation, with the objective of enhancing the diversity of object orientations and improving the model’s ability to learn from rotationally varied perspectives. A total of nine Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures were tested—DenseNet121, InceptionV3, MobileNet, MobileNetV2, ResNet50, ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and Xception—under different batch sizes (32, 64, 128, and 256) and two training strategies: Transfer Learning (TL) and Fine-Tuning (FT).

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with original dataset.

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with original dataset.

| Rank |

Model |

Method |

Batch size |

Accuracy |

F1 Score (bogus) |

F1 Score (real) |

| 1 |

MobileNet |

fine_tuned |

64 |

0.98938 |

0.99393 |

0.95758 |

| 2 |

ResNet50 |

fine_tuned |

32 |

0.98634 |

0.99222 |

0.94410 |

| 3 |

VGG16 |

fine_tuned |

32 |

0.98634 |

0.99221 |

0.94479 |

| 4 |

VGG19 |

fine_tuned |

256 |

0.98331 |

0.99049 |

0.93168 |

| 5 |

MobileNet |

transfer |

32 |

0.98483 |

0.99130 |

0.94048 |

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with rotation dataset.

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with rotation dataset.

| Rank |

Model |

Method |

Batch size |

Accuracy |

F1 Score (bogus) |

F1 Score (real) |

| 1 |

Xception |

transfer |

128 |

0.97750 |

0.97739 |

0.97761 |

| 2 |

Xception |

transfer |

256 |

0.97375 |

0.97352 |

0.97398 |

| 3 |

VGG16 |

fine_tuned |

128 |

0.97500 |

0.97497 |

0.97503 |

| 4 |

VGG19 |

fine_tuned |

256 |

0.97188 |

0.97168 |

0.97207 |

| 5 |

Xception |

fine_tuned |

32 |

0.97188 |

0.97146 |

0.97227 |

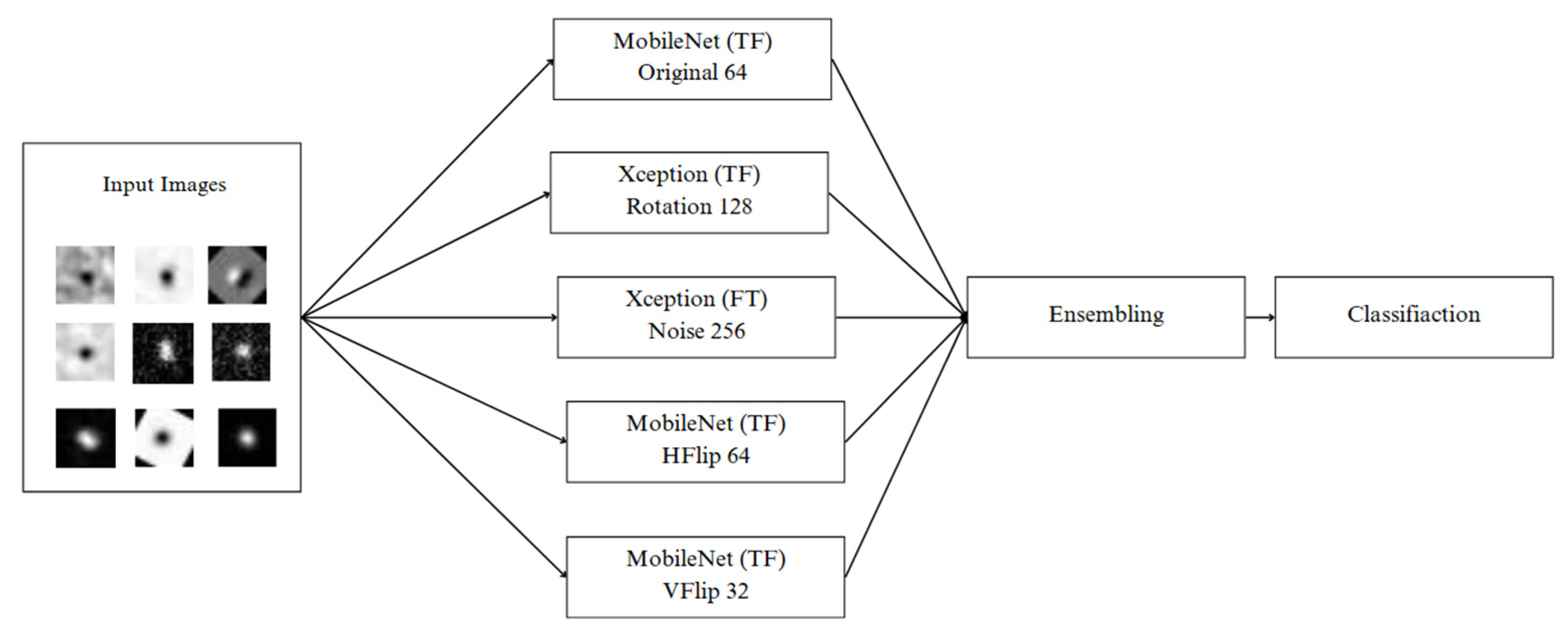

The results indicated that Xception consistently outperformed other models, particularly in Transfer Learning at batch size 128, where it achieved an accuracy of 0.97750 and an F1-score (real) of 0.97761, demonstrating exceptional capability in learning rotational patterns. Even in Fine-Tuning with batch size 256, Xception maintained excellent performance, with accuracy of 0.96938 and F1-score (real) of 0.96981, reflecting both high accuracy and stability. Another standout model was VGG16 (Fine-Tuned), which achieved accuracy of 0.97500 and F1-score (real) of 0.97503 at batch size 128, closely matching Xception’s performance and surpassing many other models.

MobileNet, known for its computational efficiency and compact architecture, also performed well in Transfer Learning at batch size 128, with accuracy of 0.96250 and F1-score (real) of 0.96245. However, when fine-tuned, MobileNet displayed signs of overfitting or class imbalance, particularly at batch size 128, where despite a high precision of 0.99826, the recall dropped to 0.71875, resulting in a reduced F1-score of 0.87610. This suggests that additional regularization or balancing techniques may be necessary when applying Rotation to lightweight models like MobileNet.

ResNet50 and ResNet101 exhibited greater variability. For example, ResNet50 fine-tuned at batch size 256 failed completely, with accuracy of 0.5 and F1-score of 0, indicating poor compatibility between deep ResNet architectures and Rotation augmentation without appropriate tuning. On the other hand, ResNet101 fine-tuned at batch size 32 performed well, achieving accuracy of 0.96438 and F1-score (real) of 0.96497, suggesting that smaller batch sizes may be more suitable for deep ResNet models under this augmentation strategy.

MobileNetV2 also demonstrated strong performance, with Transfer Learning at batch size 256 yielding accuracy of 0.96812 and F1-score (real) of 0.96854, which is impressive given the model’s lightweight and energy-efficient design. Similarly, VGG19 showed notable consistency in both Transfer and Fine-Tuned settings, with Fine-Tuned VGG19 at batch size 256 reaching accuracy of 0.97188 and F1-score (real) of 0.97207—among the highest in the experiment.

In conclusion, the results suggest that Xception (Transfer, batch size 128), VGG16 (Fine-Tuned, batch size 128), and VGG19 (Fine-Tuned, batch size 256) were the top three performers under Rotation-based augmentation, maintaining high accuracy and F1-scores across both “bogus” and “real” classes. Meanwhile, models like ResNet50 and MobileNet, in some configurations showed issues with performance imbalance or overfitting, highlighting the need for careful selection, hyperparameter tuning, and possibly the application of additional regularization methods. Ultimately, these findings demonstrate that Rotation alone can be a highly effective augmentation technique, provided that the model architecture and batch size are appropriately matched to the nature of the data.

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with noise dataset.

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with noise dataset.

| Rank |

Model |

Method |

Batch size |

Accuracy |

F1 Score (bogus) |

F1 Score (real) |

| 1 |

Xception |

transfer |

128 |

0.97750 |

0.97739 |

0.97761 |

| 2 |

Xception |

transfer |

256 |

0.97375 |

0.97352 |

0.97398 |

| 3 |

VGG16 |

fine_tuned |

128 |

0.97500 |

0.97497 |

0.97503 |

| 4 |

VGG19 |

fine_tuned |

256 |

0.97188 |

0.97168 |

0.97207 |

| 5 |

Xception |

fine_tuned |

32 |

0.97188 |

0.97146 |

0.97227 |

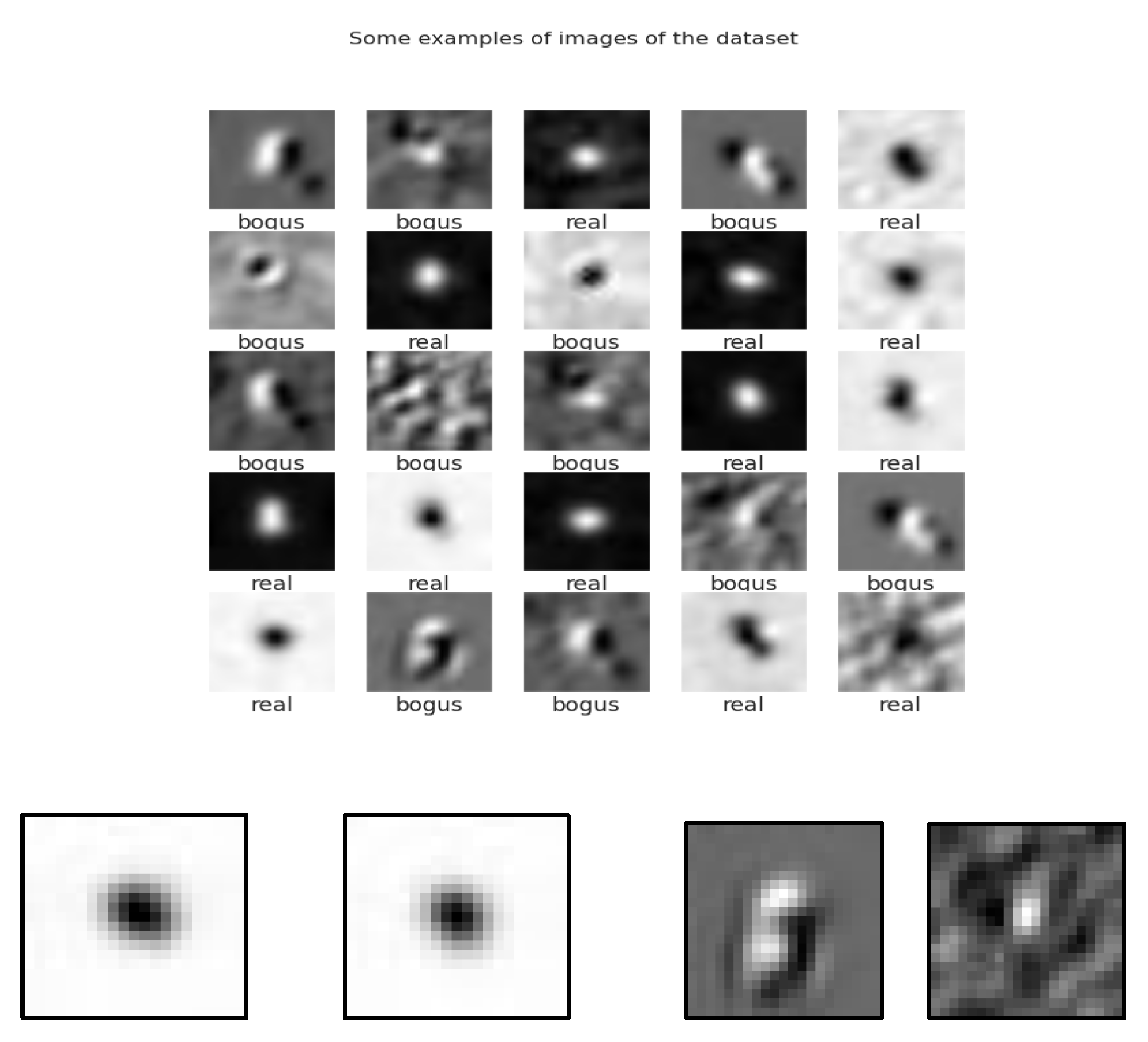

In this experiment, all models were trained using astronomical image data augmented with Noise, which involves injecting random disturbances into images to simulate the imperfections commonly found in real-world astronomical observations—such as blurring, sensor artifacts, or low-light conditions. The study compared the performance of nine Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures—DenseNet121, InceptionV3, MobileNet, MobileNetV2, ResNet50, ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and Xception—under two training strategies: Transfer Learning and Fine-Tuning, across a range of batch sizes (32, 64, 128, and 256).

Overall results indicate that most models failed to effectively learn from noise-augmented data, especially MobileNet, MobileNetV2, VGG16, VGG19, ResNet50, and ResNet101, all of which consistently yielded an accuracy of 0.50000 under all combinations of training strategy and batch size. This strongly suggests a failure in learning or a complete inability to distinguish between classes. Notably, the F1-score for the “real” class was 0.00000, indicating that these models failed to correctly classify any true instances or were severely biased toward the “bogus” (negative) class.

The few models that demonstrated some resilience to the effects of noise were Xception and InceptionV3, which still managed to achieve accuracy and F1-score values above random chance. The Xception model fine-tuned at batch size 256 was the best-performing model in this experiment, achieving an accuracy of 0.72625, precision (bogus) = 0.66667, recall (bogus) = 0.90500, and F1-score (bogus) = 0.76776, with a real-class F1-score of 0.66667—not exceptionally high but significantly better than all other models. Another model with relatively promising results was ResNet50 fine-tuned at batch size 256, which achieved accuracy = 0.85000 and F1-score (real) = 0.83827. While precision and recall were still lower than those observed in non-noise settings, the performance remained reasonably usable.

InceptionV3 showed mixed results, especially under Transfer Learning, where it achieved accuracy of 0.63187 and F1-score (real) = 0.43092 at batch size 32. Although not particularly high, this still indicates some degree of meaningful learning beyond random prediction. However, Fine-Tuning of InceptionV3 across several batch sizes often resulted in F1-scores for the real class dropping below 0.2—or even 0.1—which may indicate overfitting or over-adaptation to the noise, thereby degrading its ability to generalize to true class features.

Interestingly, several models—such as MobileNetV2 (transfer, batch 256)—showed high precision for the “real” class (e.g., 0.75) but extremely low F1-scores (e.g., 0.00746). This disparity suggests that while a few correct predictions may have occurred, the number of predictions for the “real” class was extremely low, leading to very poor recall and severely penalized F1-scores. This reinforces the conclusion that most models failed to cope with noise unless specifically adapted to handle such data.

In summary, the experiment demonstrates that Noise-based Data Augmentation significantly degrades model accuracy across most architectures and training strategies. The most noise-resilient model was Xception (fine-tuned, batch 256), followed by ResNet50 (fine-tuned, batch 256) and InceptionV3 (transfer, batch 32), all of which performed noticeably better than random baselines. However, these findings also underscore the need for advanced techniques—such as denoising preprocessing, noise-aware training strategies, or mixed augmentation pipelines—to enhance model robustness and generalization when training on noisy astronomical data

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with hflip dataset.

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with hflip dataset.

| Rank |

Model |

Method |

Batch size |

Accuracy |

F1 Score (bogus) |

F1 Score (real) |

| 1 |

MobileNet |

transfer |

64 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

| 2 |

Xception |

transfer |

32 / 64 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

| 3 |

VGG19 |

fine_tuned |

32 / 64 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

| 4 |

VGG16 |

fine_tuned |

64 / 256 |

0.99687 |

0.99688 |

0.99688 |

| 5 |

MobileNetV2 |

transfer |

256 |

0.99375 |

0.99379 |

0.99379 |

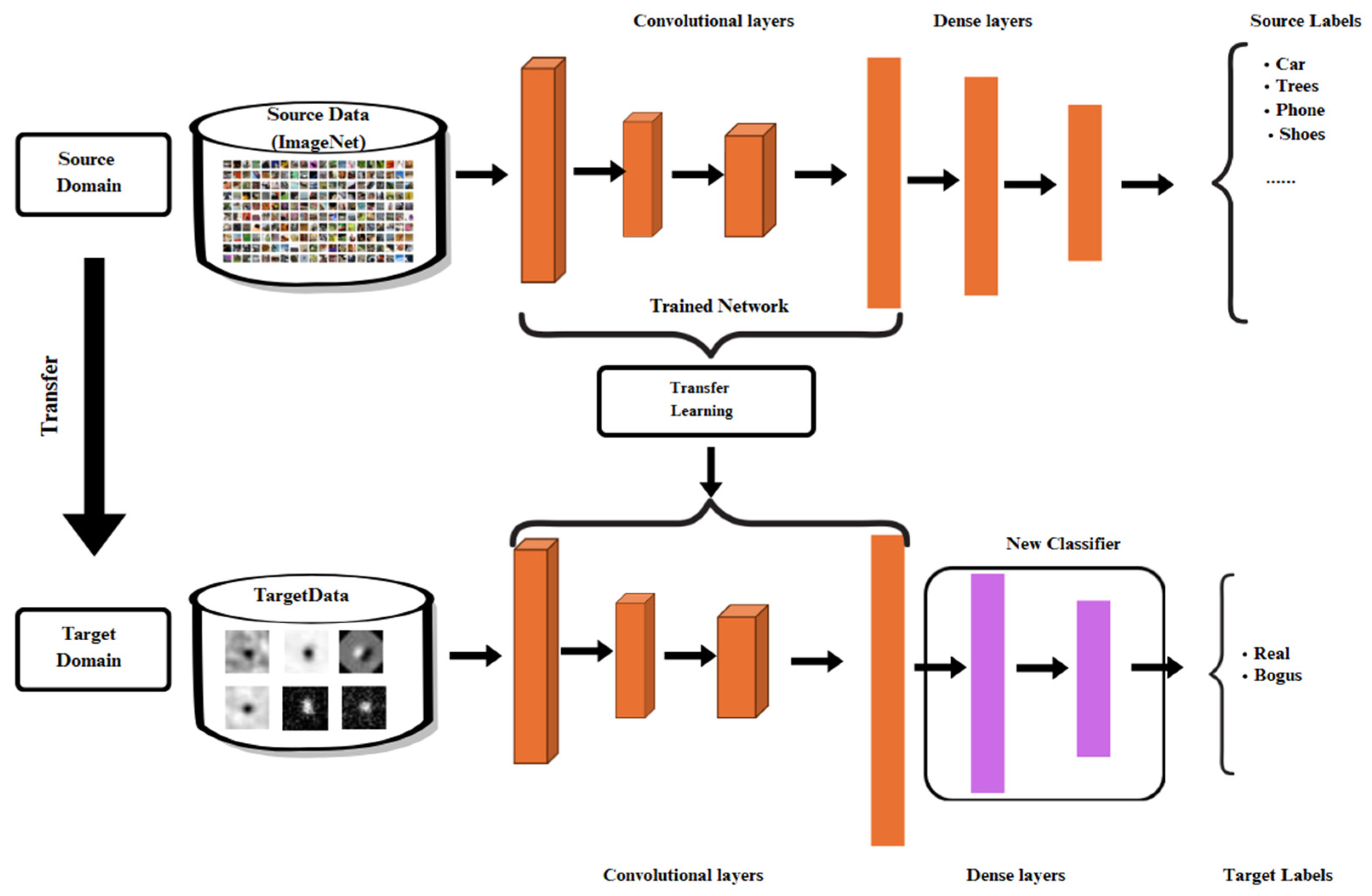

In this experiment, all data were trained using Horizontal Flip (HFlip) as a Data Augmentation technique. This method reflects the images horizontally to increase the diversity of object orientation in astronomical data. The objective was to enhance the capacity of Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to learn object features that may appear flipped when captured by telescopes from different directions. The study involved nine CNN architectures: DenseNet121, InceptionV3, MobileNet, MobileNetV2, ResNet50, ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and Xception, evaluated under both Transfer Learning and Fine-Tuning strategies, and across varying Batch Sizes (32, 64, 128, 256).

The results clearly demonstrated that most models performed consistently well, particularly Xception, MobileNet, InceptionV3, VGG16, and VGG19. These models frequently achieved Accuracy near 100% and high F1-scores for both “bogus” and “real” classes. For example, Xception (both transfer and fine-tuned) at batch sizes 64, 128, and 256 achieved Accuracy ranging from 0.99750 to 0.99813, with F1-scores for both classes between 0.99688 and 0.99875. This reflects the model’s deep and precise learning of flipped image characteristics—among the highest-performing results in the experiment.

Similarly, MobileNet (both transfer and fine-tuned) yielded outstanding performance. Notably, MobileNet (transfer, batch 128) achieved Accuracy = 0.99875 and F1-score (real) = 0.99875, comparable to Xception and VGG19 (fine-tuned) under several conditions. InceptionV3 also showed consistently strong results, with transfer models at batch sizes 64, 128, and 256 achieving Accuracy values between 0.99625 and 0.99750, and very high F1-scores across both classes. It is notable that F1-score (real) for these models never dropped below 0.99000 under optimal conditions.

VGG16 and VGG19 also performed remarkably well, especially in fine-tuned mode at batch sizes 64 and 256, achieving Accuracy between 0.99687 and 0.99813, with near-perfect F1-scores in both classes. DenseNet121, particularly in transfer learning mode at batch sizes 128 and 256, consistently produced F1-score (real) > 0.99315, demonstrating the architecture's robustness in learning from horizontally flipped images.

However, some models showed performance degradation. For example, MobileNetV2 (fine-tuned) at batch sizes 32, 64, and 128 exhibited Accuracy between 0.91 and 0.92, with F1-score (real) dropping to approximately 0.91–0.93. Additionally, ResNet101 and ResNet50 under certain conditions—particularly fine-tuned at batch sizes 128 or 256—completely failed to generalize, with Accuracy = 0.50000 and F1-score (real) = 0.00000, indicating an inability to learn or severe overfitting to one class.

In conclusion, Horizontal Flip was found to significantly enhance model performance in learning symmetrical or directionally inverted objects, especially when paired with well-designed deep architectures like Xception, MobileNet, and InceptionV3. While Fine-Tuning generally produced strong results, Transfer Learning also proved capable of generating powerful models—offering an efficient training strategy under limited computational resources. Therefore, HFlip can be considered a highly effective augmentation technique for improving classification accuracy in astronomical image analysis.

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with vflip dataset.

Table 2.

Comparison of classification results of different deep learning with vflip dataset.

| Rank |

Model |

Method |

Batch size |

Accuracy |

F1 Score (bogus) |

F1 Score (real) |

| 1 |

MobileNet |

transfer |

64 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

| 2 |

Xception |

transfer |

32 / 64 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

| 3 |

VGG19 |

fine_tuned |

32 / 64 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

0.99875 |

| 4 |

VGG16 |

fine_tuned |

64 / 256 |

0.99687 |

0.99688 |

0.99688 |

| 5 |

MobileNetV2 |

transfer |

256 |

0.99375 |

0.99379 |

0.99379 |

In this experiment, the dataset was augmented using Vertical Flip (VFlip)—a technique that mirrors astronomical images along the vertical axis—to enhance the model's ability to learn features from objects captured in reversed vertical orientations. This method is particularly valuable in astronomical image analysis, where object positions and orientations can vary across different observations. The experiment involved nine CNN architectures—DenseNet121, InceptionV3, MobileNet, MobileNetV2, ResNet50, ResNet101, VGG16, VGG19, and Xception—under both Transfer Learning and Fine-Tuning strategies, and across various Batch Sizes (32, 64, 128, and 256). The overall results demonstrated that deeper and structurally efficient models effectively handled the vertical flipping transformation. Specifically, models such as MobileNet, Xception, InceptionV3, VGG19, and VGG16 achieved consistently high performance across all key evaluation metrics—Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1-score—for both “bogus” and “real” classes. Notably, MobileNet (transfer) and VGG19 (fine-tuned) at batch sizes of 32, 64, and 128 achieved Accuracy and F1-score as high as 0.99875, indicating near-perfect classification of vertically flipped images.

Similarly, Xception (transfer) at batch size 256 reached Accuracy = 0.99813 and identical F1-scores of 0.99813 for both classes. Xception consistently maintained high performance across all batch sizes and training strategies. However, in some cases, such as Xception fine-tuned at batch 256, Accuracy slightly decreased to 0.98000 and F1-score (real) = 0.98039, which remains remarkably high and commendable.

Other models like DenseNet121 also showed excellent results, with transfer learning at batch sizes 32 or 64 yielding Accuracy between 0.99125 and 0.99313 and F1-score (real) exceeding 0.991. Similarly, InceptionV3 (transfer) at batch sizes 64 and 128 achieved Accuracy up to 0.99687 and F1-score (real) > 0.99688, reflecting robust and consistent performance. Despite their older architecture, VGG16 and VGG19 maintained outstanding accuracy—VGG16 fine-tuned at batch 256 achieved Accuracy = 0.99687 and F1-score (real) = 0.99688, comparable to top-performing models like Xception and MobileNet.

In contrast, models such as ResNet50 and ResNet101 exhibited more volatile performance. Specifically, ResNet101 fine-tuned at batch sizes 128 and 256 showed Accuracy = 0.50000 and F1-score (real) = 0.00000, indicating potential overfitting or heightened sensitivity to vertical flipping transformations. However, ResNet101 (transfer) at batch sizes 64 and 256 still produced Accuracy values around 0.92–0.93 and F1-score (real) > 0.92, suggesting that transfer learning may help mitigate VFlip's impact on ResNet's performance.

In summary, the experiment clearly shows that Vertical Flip (VFlip) augmentation significantly enhances model performance when applied with the right architectures particularly Xception, MobileNet, InceptionV3, VGG19, and VGG16. Fine-Tuning with moderate batch sizes (e.g., 64 or 128) consistently yielded very high evaluation scores. Moreover, Transfer Learning proved sufficient for models like MobileNet and Xception, achieving high performance without full retraining. Thus, VFlip stands out as a highly effective augmentation technique, especially in real-world systems requiring robustness and accuracy in scenarios with unpredictable image orientation.