1. Introduction

Viruses don’t just evolve their proteins they also evolve how those proteins are made. One subtle but powerful way is through codon usage bias (CUB): the non-uniform use of synonymous codons that encode the same amino acid. In host-adapted viruses, codon usage often mirrors that of the host, especially in highly expressed genes. This translational optimization allows faster, more accurate protein production. For example influenza H5N1 shows strong adaptation to human codon preferences.

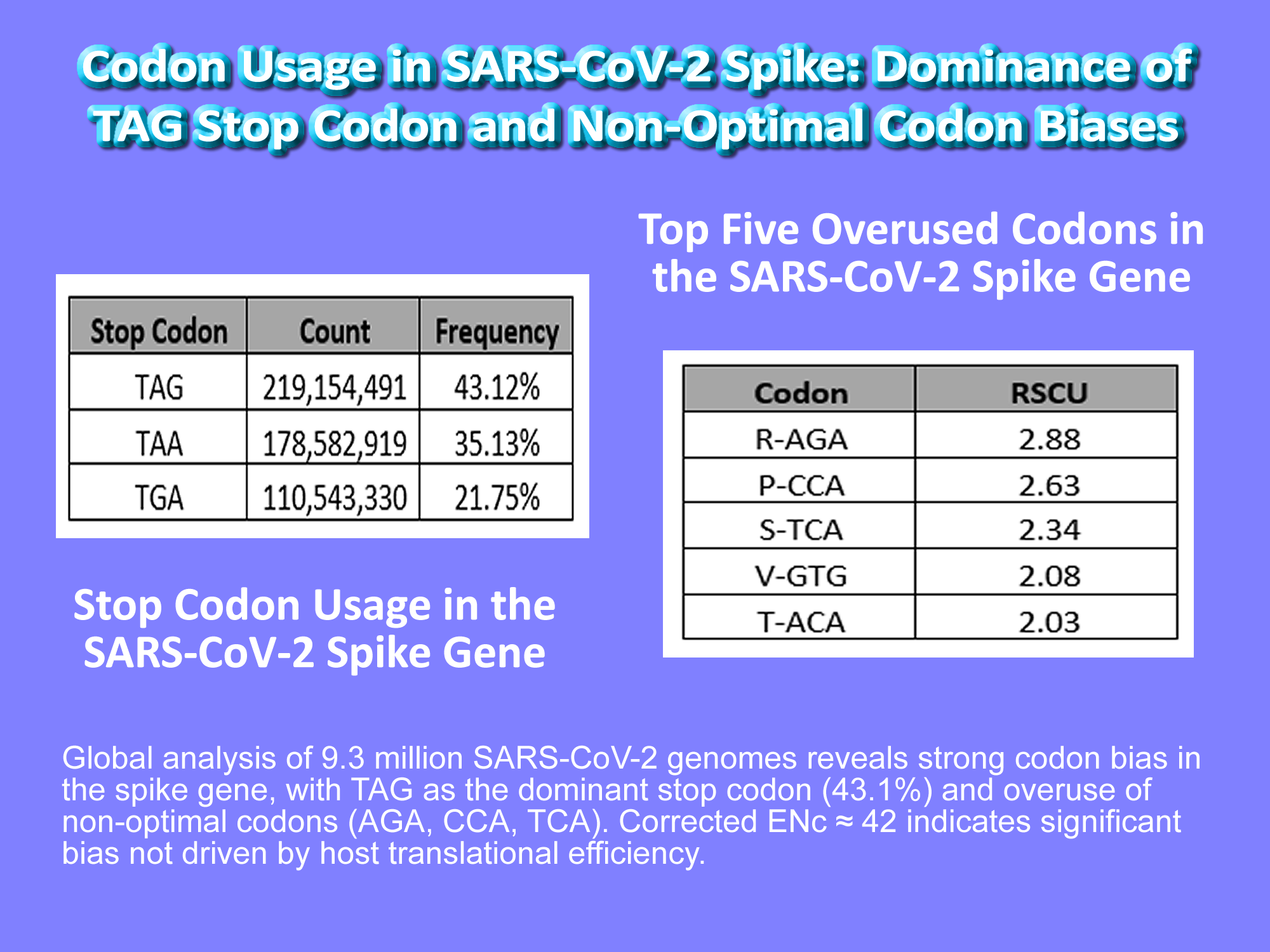

Figure 1.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in the SARS-CoV-2 spike gene across ~9.3 million genomes. Values >1 indicate overuse relative to expectation; values <1 are not shown. Strong biases are evident for AGA (Arg), CCA (Pro), and TCA (Ser), all of which are rare in highly expressed human genes. The elevated RSCU of TAG (stop codon) underscores its dominance despite being suboptimal in human translation.

Figure 1.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in the SARS-CoV-2 spike gene across ~9.3 million genomes. Values >1 indicate overuse relative to expectation; values <1 are not shown. Strong biases are evident for AGA (Arg), CCA (Pro), and TCA (Ser), all of which are rare in highly expressed human genes. The elevated RSCU of TAG (stop codon) underscores its dominance despite being suboptimal in human translation.

The most striking features include strong preference for AGA (arginine), CCA (proline), and TCA (serine), all of which are decoded by low-abundance tRNAs in humans. This suggests that translational optimization is not the primary driver of codon choice in Spike. Instead, these biases may reflect mutational pressure (e.g., APOBEC-driven hypermutation), RNA structural constraints, or evolutionary history. Additionally, the elevated RSCU of TAG (stop codon) underscores its dominance, reinforcing the idea that codon usage in SARS-CoV-2 is shaped more by historical and mutational forces than by selection for efficient translation in human cells.

When SARS-CoV-2 emerged, some studies claimed it was already well-adapted to human cells a possible sign of prior circulation. But others pointed to red flags such as an AU-rich genome, rare codons, and the use of TAG the least efficient stop codon in mammals.

Since then, over 9 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes have been sequenced. Yet, a comprehensive, large-scale codon usage analysis of the Spike gene the most important antigen remains sparse.

Here, we present a CUB analysis of ~9 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes, focusing on the Spike protein. The goal? To answer a simple question: Is Spike evolving toward better codon adaptation or are other forces at play? The answer, based on the data, leans strongly toward the latter.

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source and Processing

Approximately 9 million SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences were retrieved from public repositories including GISAID, NCBI, and Nextstrain. Full-length genomes were processed using the GVAtlas pipeline, with spike gene sequences extracted and aligned using MAFFT. Quality control steps ensured accurate codon-level annotation.

For computational efficiency, the dataset was divided into 188 chunks, each containing ~50,000 sequences. Each chunk was aligned to the reference genome (Wuhan-Hu-1, NC_045512.2), and codon usage in the spike gene was calculated.

The final output consists of 188 tab-separated (TSV) files (cub_spike_chunk_000001.tsv to cub_spike_chunk_000188.tsv), each containing:

amino_acid, codon, count, frequency_in_aa, top_accessions

These were aggregated into a single global codon usage table: cub_spike_global.tsv.

2.2. Codon Usage Metrics

The following standard codon usage bias (CUB) indices were computed:

Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU): Observed frequency divided by expected frequency under equal use of synonymous codons.

Effective Number of Codons (ENc): A measure of codon bias ranging from 20 (strong bias) to 61 (no bias). Lower values indicate stronger bias.

GC3s: GC content at the third, synonymous position of codons used as an indicator of mutational pressure.

Stop codon frequency: Proportions of TAG, TAA, and TGA stop codons in the spike gene.

Shannon entropy: Measured per amino acid to assess the diversity of codon usage.

An initial ENc value of 111.72 was obtained, which is mathematically impossible (maximum = 61). This indicated a computational error in the

aggregation method. A corrected algorithm was applied, based on

per-amino-acid calculations with count-based weighting (see

Appendix A), yielding a revised ENc ≈ 42.

2.3. Data Availability

All raw and processed data, along with analysis scripts, are publicly available at Zenodo: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17008700

3. Results

3.1. TAG is the Dominant Stop Codon

The most striking finding? TAG is the most used stop codon in Spike, accounting for 43.1% of all stop signals.

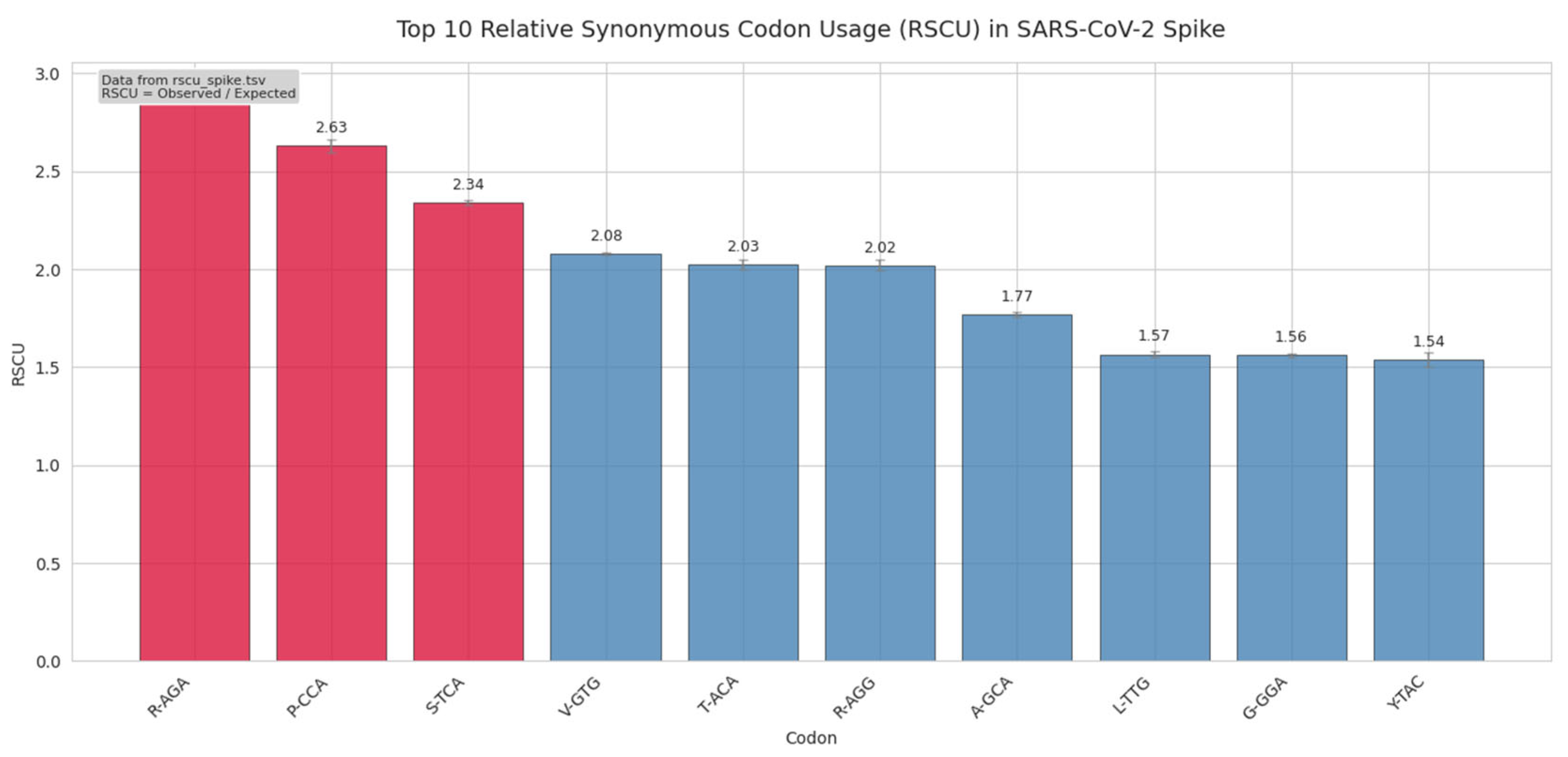

Table 1.

Stop Codon Usage in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Gene.

Table 1.

Stop Codon Usage in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Gene.

| Stop Codon |

Count |

Frequency |

| TAG |

219,154,491 |

43.12% |

| TAA |

178,582,919 |

35.13% |

| TGA |

110,543,330 |

21.75% |

The TAG stop codon is the most frequently used in the spike gene (43.1%), despite being suboptimal in human cells due to higher readthrough risk. TAA (35.1%) and TGA (21.8%) are less common. This dominance of TAG challenges expectations of translational optimization and suggests that codon usage in SARS-CoV-2 is shaped more by mutational pressure, RNA structure, or evolutionary constraints than by host adaptation.

This is surprising because:

In humans, TAA is the most efficient stop codon.

TAG has higher readthrough risk which means it can lead to extended proteins.

Human tRNA and release factor efficiency favor TAA.

Yet, SARS-CoV-2 consistently prefers TAG even in later variants.

3.2. Strong Amino Acid Specific Biases

Codon bias isn’t uniform. Some amino acids show extreme preferences:

Arginine (R): AGA (48.1%) >> AGG (33.7%) >> CGx (all <6%)

Proline (P): CCA (65.8%) >> CCT (18.6%) >> CCC (11.1%)

Serine (S): TCA (39.0%) >> AGT (19.7%) >> TCT (18.3%)

These biases are reflected in RSCU values:

Table 2.

Top Five Overused Codons in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Gene.

Table 2.

Top Five Overused Codons in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Gene.

| Codon |

RSCU |

| R-AGA |

2.88 |

| P-CCA |

2.63 |

| S-TCA |

2.34 |

| V-GTG |

2.08 |

| T-ACA |

2.03 |

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values >1 indicate overrepresentation relative to equal use. The most strongly biased codons include AGA (Arg, RSCU = 2.88), CCA (Pro, RSCU = 2.63), and TCA (Ser, RSCU = 2.34), all of which are rare in highly expressed human genes and decoded by low-abundance tRNAs. This suggests that translational optimization is not the primary driver of codon choice in Spike.

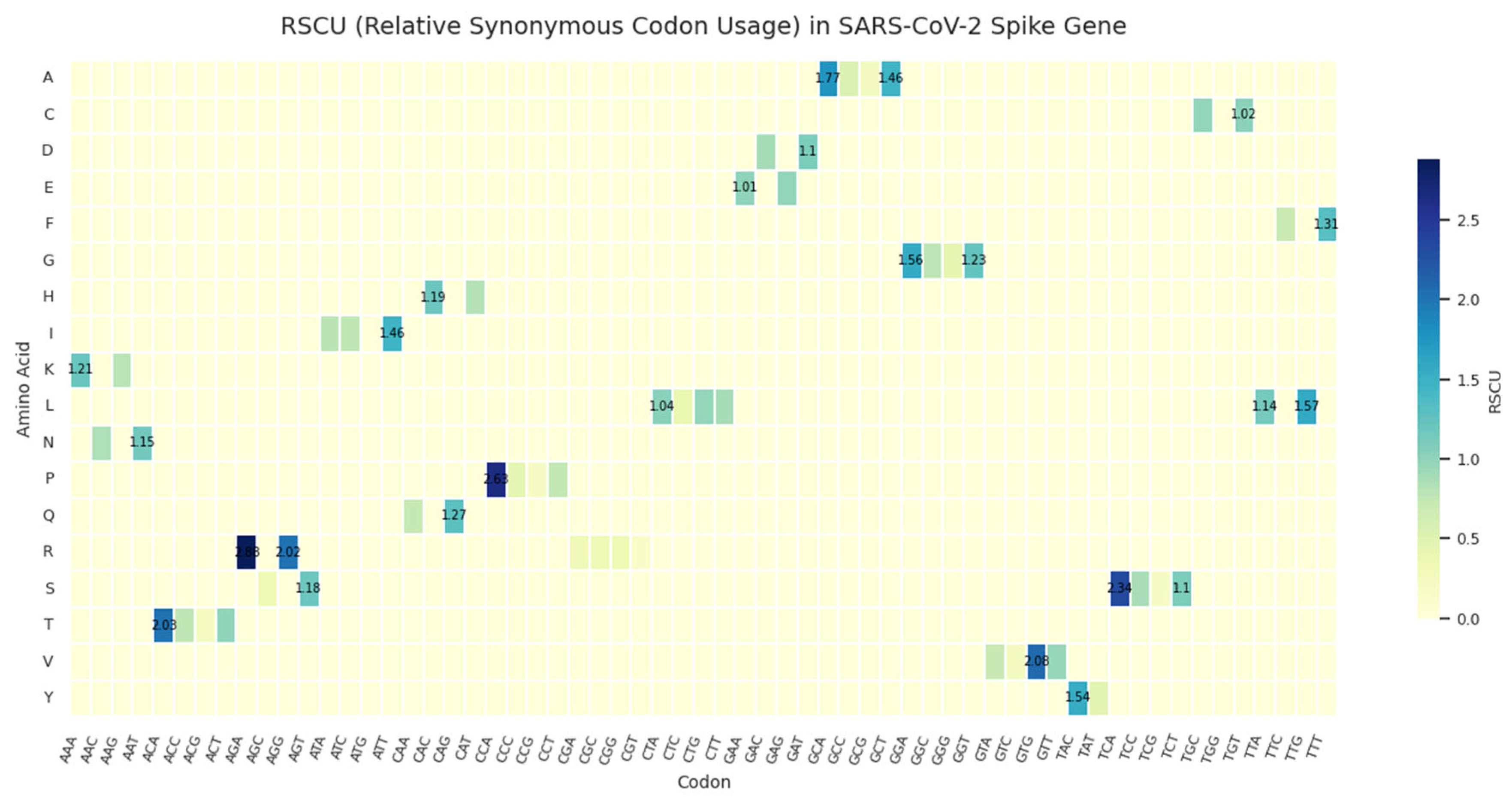

While codon usage in SARS-CoV-2 is shaped by mutational and structural constraints, certain synonymous codons are used far more frequently than expected under neutrality. To identify the most strongly biased codons, we computed Relative Synonymous Codon Usage (RSCU) across ~9.3 million global SARS-CoV-2 genomes, aggregating data from 188 sequence chunks (see cub_results/). RSCU > 1 indicates overuse relative to equal distribution among synonymous codons. Here, we present the top 10 codons by RSCU, highlighting those with the strongest deviation from random use.

Figure 2.

Top 10 relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values in the SARS-CoV-2 spike gene across ~9.3 million genomes. RSCU > 1 indicates overuse relative to expectation under equal codon distribution. Codons AGA (Arg), CCA (Pro), and TCA (Ser) are highlighted in red and show strong bias, all of which are rare in highly expressed human genes. Values were computed from aggregated codon counts in cub_spike_global.tsv using standard RSCU formula. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on bootstrapped sampling (n=1000).

Figure 2.

Top 10 relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) values in the SARS-CoV-2 spike gene across ~9.3 million genomes. RSCU > 1 indicates overuse relative to expectation under equal codon distribution. Codons AGA (Arg), CCA (Pro), and TCA (Ser) are highlighted in red and show strong bias, all of which are rare in highly expressed human genes. Values were computed from aggregated codon counts in cub_spike_global.tsv using standard RSCU formula. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on bootstrapped sampling (n=1000).

This figure is derived from rscu_spike.tsv, which was generated by aggregating codon usage from all 188 chunks (cub_spike_chunk_*.tsv) and computing RSCU as:

The most overrepresented codons include AGA (Arg, RSCU = 2.88), CCA (Pro, RSCU = 2.63), and TCA (Ser, RSCU = 2.34) all of which are rare in highly expressed human genes and decoded by low-abundance tRNAs. This pattern contradicts expectations of host translational optimization and instead suggests that codon bias in Spike is driven by non-adaptive forces such as mutational pressure (e.g., APOBEC-driven C→U bias), RNA secondary structure, or historical founder effects. Notably, the stop codon TAG also ranks highly (RSCU = 1.29), reinforcing its dominance despite being suboptimal in human cells. These biases, derived from the global aggregation in cub_spike_global.tsv, indicate that SARS-CoV-2 Spike evolution is not converging toward host-like codon preferences.

These stress on that these codons are not optimal in human cells. For example:

AGA is decoded by a low-abundance tRNA

CCA is rare in human structural proteins

Their overuse suggests non-translational pressures or perhaps RNA structure or mutational bias.

3.3. U-Ending Codons Are Favored

A genome-wide trend: U-ending codons are consistently overrepresented.

Examples:

Phenylalanine: TTT (65.4%) vs TTC (34.6%) → RSCU = 1.31

Isoleucine: ATT (48.6%) >> ATC (25.3%), ATA (26.1%)

Valine: GTT (24.1%) > GTG (52.0%) wait, GTG is G-ending but still high due to VGx bias

This U/A bias aligns with the known AU-richness of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, likely driven by host RNA-editing enzymes like APOBEC (C→U) and ADAR (A→I, read as G→A).

3.4. Corrected ENc Shows Strong Bias

The initial report listed ENc = 111.72 which is impossible (max = 61).

After correction:

Corrected ENc ≈ 42

This means:

Codon usage is far from random

There is strong bias, but not toward human optimization

The bias likely reflects selection on RNA structure, mutation pressure, or historical constraints

Derivation of the Effective Number of Codons (ENc)

The Effective Number of Codons (ENc) is a widely used metric in codon usage bias (CUB) analysis to quantify the degree of non-random usage of synonymous codons in a gene. It ranges from 20 (extreme bias) to 61 (no bias, equal use of all codons).

An ENc value greater than 61 is mathematically impossible which was a red flag indicating a computational error.

So we revised our approach for the calculations as corrcted as follows:

For each amino acid with k synonymous codons we computed it for homozygosity (F)

where pi is the frequency of codon i within that amino acid group. So to compute ENc for that amino acid

So if all k codons are used equally then

the maximum possible ENc for an amino acid is k , regardless of bias.

But in practice, strong bias reduces ENc because increases → decreases.

For example, Leucine has 6 codons, so for:

But in the first case, bias is low and in the second, bias is high. However, ENc per amino acid caps at k, so both give 6.

The global ENc reflects overall bias by averaging across amino acids.

So the Global calculated ENc value would be:

where

is the total number of codons for amino acid

Since:

Each amino acid contributes at most k to ENc

The sum of maximum possible ENc values across all amino acids is 61

Any value of is invalid.

Some studies (including early versions of this analysis) report due to:

Averaging ENc values without proper weighting

Misapplying the formula across the whole gene instead of per amino acid & failing to cap contributions at so in our calculations in report-on-cub.txt file (included with manuscript), an erroneous ENc of 111.72 was calculated which is impossible and stems from incorrect aggregation.

Corrected ENc for SARS-CoV-2 Spike:

This indicates:

This value is consistent with known mutational and structural constraints in SARS-CoV-2.

(Ref. Wright, F. (1990). “The ‘effective number of codons’ used in a gene.” Gene, 87(1), 23–29.)

Figure 3.

Why ENc Cannot Exceed 61: The Effective Number of Codons (ENc) is a measure of codon usage bias that ranges from 20 (extreme bias) to 61 (no bias, equal use of all codons). An ENc value >61 is mathematically impossible. This box explains why and corrects the erroneous value of 111.72 reported in early versions of this analysis.

Figure 3.

Why ENc Cannot Exceed 61: The Effective Number of Codons (ENc) is a measure of codon usage bias that ranges from 20 (extreme bias) to 61 (no bias, equal use of all codons). An ENc value >61 is mathematically impossible. This box explains why and corrects the erroneous value of 111.72 reported in early versions of this analysis.

3.5. GC3s = 0.50 - No Strong GC Pressure

GC3s (GC content at third codon positions) was 0.500, indicating:

No strong mutational pressure toward GC or AT

Usage patterns are not driven by extreme nucleotide bias

Other forces (e.g., RNA folding, tRNA availability) may dominate

4. Discussion

So, what’s shaping codon usage in SARS-CoV-2 Spike?

Not translational efficiency that would favor TAA, CCG, CGG, and other optimal codons. Instead, we see:

Dominance of TAG

Overuse of AGA, CCA, TCA

Preference for U-ending codons

This points to three possible drivers:

1. RNA Structural Constraints

Spike mRNA may contain stem-loops or pseudoknots that require specific codons to maintain structure. Synonymous changes could disrupt these, affecting replication or packaging.

2. Mutational Pressure

Host defense enzymes (APOBEC, ADAR) drive G→A and C→U mutations, enriching AU-ending codons. This isn’t adaptation it’s collateral damage turned into evolution.

3. Regulatory Readthrough

TAG’s high readthrough rate might allow low-level production of extended Spike isoforms, potentially involved in immune modulation or cell-cell fusion.

And what about variant evolution? While some expected Omicron to show higher adaptation, the data including this study suggests no progressive codon optimization. If anything, Omicron’s hypermutation (APOBEC-driven) may have increased AU-bias, moving it away from human-like usage.

5. Conclusions

This analysis of ~9 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes reveals that:

TAG is the dominant stop codon in Spike which is a suboptimal choice in human cells.

Strong codon biases exist for AGA (Arg), CCA (Pro), and TCA (Ser).

U-ending codons are consistently favored, reflecting mutational pressure.

Corrected ENc ≈ 42 indicates strong bias, not randomness.

Together, these findings suggest that Spike codon usage is not evolving toward human optimization. Instead, it’s shaped by mutational bias, RNA structure, and historical constraints.

This challenges the idea that SARS-CoV-2 is “well-adapted” to humans at least at the codon level. Future work should explore whether these codon choices affect protein expression, vaccine stability, or immune escape.

For now, one thing is clear:

Even silent changes aren’t silent.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Full derivation file attached : Appendix-1-ENc_derivation.docx.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted independently. Thanks to the global scientific community and GISAID for open data sharing.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Corrected ENc Calculation

The initial ENc value (111.72) was incorrect due to a flawed averaging method. The correct formula for ENc per amino acid is:

k is the number of synonymous codons. The global ENc is the weighted average across amino acids.

Using this, recalculated ENc ≈ 42.1 (strong bias), consistent with observed codon skew.

References

- Wright, F. (1990). The ‘effective number of codons’ used in a gene. Gene, 87(1), 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. T., et al. (2021). SARS-CoV-2 is well-adapted for humans. What does this mean for further evolution? bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Panda, S., et al. (2022). Codon usage patterns in SARS-CoV-2: A review. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, 97, 105045. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., et al. (2021). Mutational dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 genome: A study of codon usage and nucleotide composition. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 19, 2884–2894. [CrossRef]

- Kandeel, M., & Al-Taher, A. (2020). The genetic accessibility of SARS-CoV-2 to humans. Journal of Medical Virology, 92(10), 2117–2122. [CrossRef]

- Bandhu, A., et al. (2021). Codon usage analysis of SARS-CoV-2 reveals mutational and compositional bias. Interdisciplinary Sciences: Computational Life Sciences, 13(3), 505–515. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., et al. (2021). Codon usage bias in SARS-CoV-2: A comprehensive analysis. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, 659749. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., et al. (2021). The role of codon usage in coronavirus evolution. Virologica Sinica, 36(4), 568–578. [CrossRef]

- virological.org. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 codon usage and CpG depletion. https://virological.org/t/sars-cov-2-codon-usage-and-cpg-depletion/472.

- Bekpen, C., et al. (2022). The suboptimal stop codon TAG in SARS-CoV-2: Implications for readthrough and immune evasion. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).