1. Introduction

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) have emerged as one of the most actively studied technologies in marine engineering, driven by their versatility across scientific, industrial, and defense applications. Unlike traditional manned or remotely operated systems, AUVs offer persistent and cost-effective operation in hazardous and remote environments, reducing risks to human operators while expanding the scope of underwater exploration. Their capability to operate independently makes them particularly attractive for missions such as seabed mapping, environmental monitoring, infrastructure inspection, and naval reconnaissance [

1,

2,

3].

Recent years have witnessed rapid advancements in the enabling technologies that underpin AUV design and operation. Improvements in energy storage, including high-density lithium-ion batteries and fuel-cell systems, have significantly extended mission endurance. Progress in propulsion system design, aided by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and reduced-order modeling, has enhanced maneuverability and efficiency in complex hydrodynamic environments. At the same time, miniaturization of high-resolution sensors, such as sonar, optical imaging devices, and chemical probes, has broadened the range of measurable ocean parameters, enabling high-fidelity mapping of physical, chemical, and biological processes [

4,

5,

6].

A particularly transformative development lies in autonomy and onboard intelligence. Advances in machine learning, adaptive control, and real-time data processing now allow AUVs to make mission-critical decisions under uncertainty, adapt their trajectories to environmental variability, and coordinate as swarms for distributed sensing. These capabilities have expanded the operational horizon of AUVs from coastal monitoring to deep-ocean exploration and under-ice missions, where human access is limited or impossible [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Beyond technological progress, global challenges have further motivated AUV research. Climate change, biodiversity conservation, and pollution mitigation require sustained, large-scale ocean observation with spatial and temporal resolutions unachievable by conventional ship-based surveys. Similarly, offshore industries and defense operations demand reliable, long-duration platforms for inspection, surveillance, and asset protection. As a result, AUVs are now regarded as indispensable tools for addressing both fundamental scientific questions and pressing societal needs [

13,

14,

15].

In this context, the development of robust motion prediction models and surrogate frameworks is critical for ensuring the safe, efficient, and autonomous operation of AUVs. High-fidelity CFD simulations provide detailed insights into the complex flow physics of propulsion and maneuvering, however, their computational cost limits real-time applicability. Reduced-order models, surrogate approaches, and hybrid strategies have therefore become central research directions, bridging the gap between accuracy and computational efficiency. The present study contributes to this ongoing effort by developing and validating a surrogate motion prediction model for a duct–jet propelled AUV, with a focus on balancing fidelity and practicality for free-running simulations [

16,

17,

18].

The AUV considered in this study is equipped with a ducted propeller that enhances propulsive efficiency and suppresses cavitation, making it well suited for low-speed, high-thrust operations. Its principal particulars are presented in

Section 2. The CFD framework, including the computational setup, test matrix, and governing equations, is described in

Section 3.

Section 4 presents the methodology for constructing the surrogate model. Results of the CFD simulations are presented in

Section 5, while

Section 6 discusses the validation of the surrogate model. Finally, conclusions are summarized in

Section 7.

5. CFD Results

Table 5 summarizes the types of CFD simulations conducted for constructing the surrogate model, and includes the final zigzag simulation for the validation after the surrogate construction. For evaluating the accuracy of hull and propeller force and moment simulations, the grid triplet is employed, while the medium grid is used for the other simulations. In the POW test with the discretized propeller, a time step of

is applied, whereas all other simulations, including those with the surrogate model, use a time step of

. The basic composition of the test matrix follows the procedure described in [

23].

5.1. Hydrostatic

A hydrostatic simulation is carried out with the AUV fixed and the relative inflow velocity set to zero in order to determine the mass of the fully-attached AUV and the longitudinal center of gravity (

). Although mass and

are often provided from experiments, in this study they are derived directly from the simulated geometry to ensure an internal balance between buoyancy and weight as well as a zero trim moment. Since most simulations are performed under captive conditions and the free-running cases are limited to 3DOF motion, the

does not affect the vehicle’s attitude. However, as it serves as the effective center of rotation and the reference for moments, the

obtained from the hydrostatic analysis is consistently employed in the subsequent simulations to improve the prediction of yaw moments. The

is determined iteratively within the hydrostatic simulation by adjusting its position until the trim moment converges to zero. The final values of mass and

are presented in

Table 1.

5.2. Propeller Open-Water Test

As noted earlier, the hydrodynamic properties of the propeller are obtained using a discretized propeller under straight-ahead conditions (

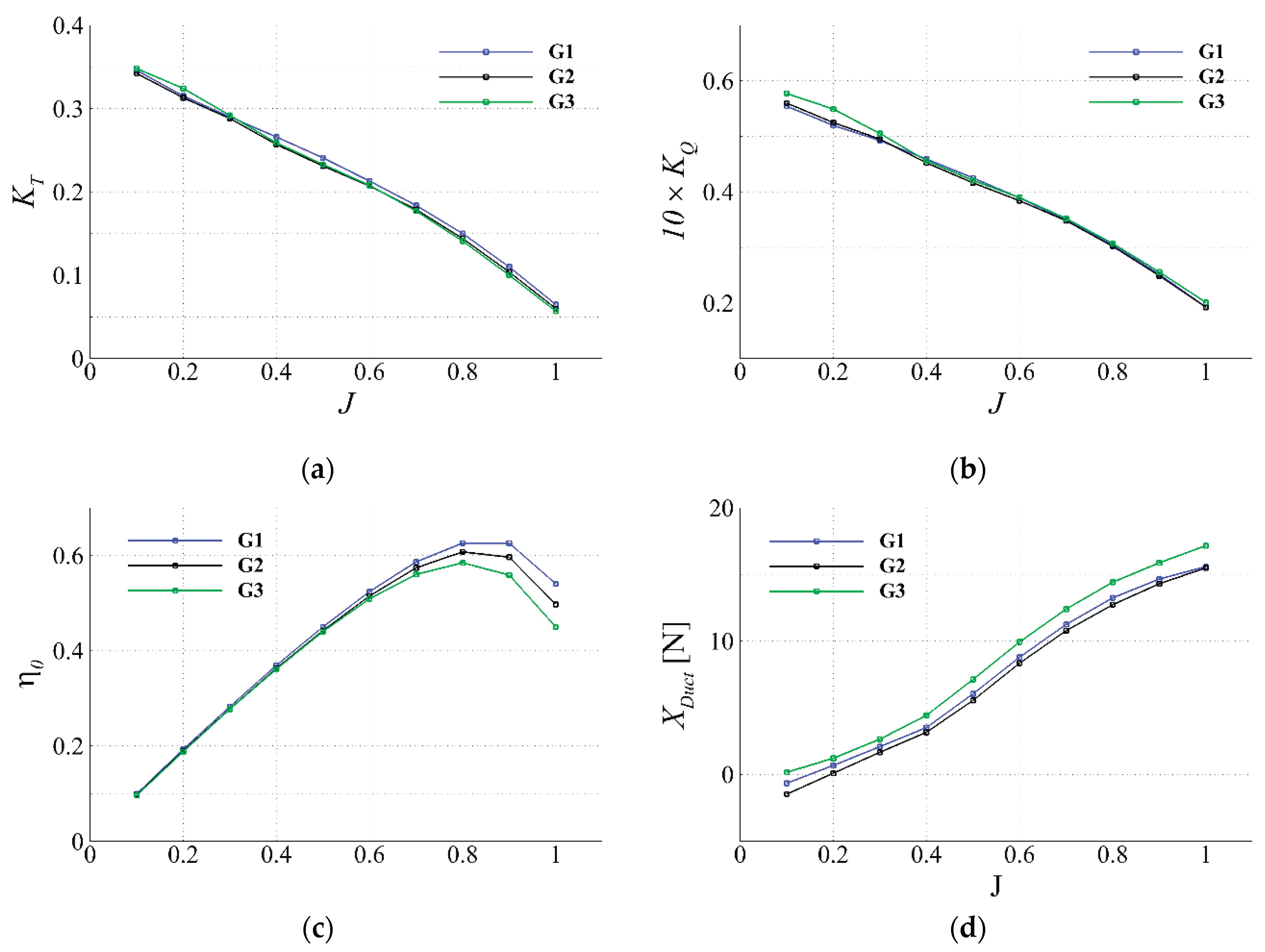

Figure 7).

Figure 8 and

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 present the thrust, torque, and propulsive efficiency computed from the grid triplet. The results show that the solutions converge toward nearly asymptotic values as the grid resolution increases. Among the three grids, the G2 case, which provides a median value for computational cost and accuracy, is considered suitable for subsequent body-force modeling.

Since the duct-jet propulsive system includes the duct itself, the convergence of the duct resistance is also examined (

Figure 8(d)). It is confirmed that the resistance on the duct achieves an accuracy comparable to that of the G1 when computed with the G2.

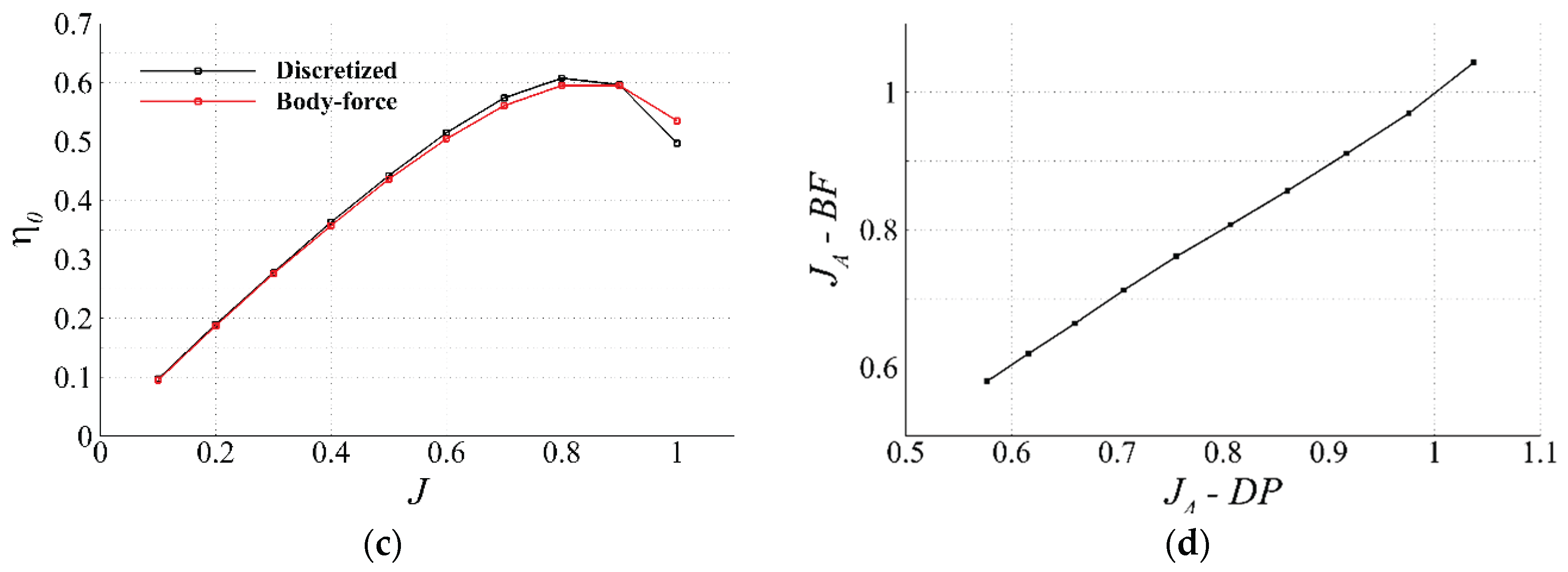

As shown in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8, the differences between the solution values (

,

,

) obtained from G1, G2, and G3 exhibit oscillatory convergence, which is reflected in the ratios

. Consequently, Richardson extrapolation does not provide reliable uncertainty estimates in many cases.

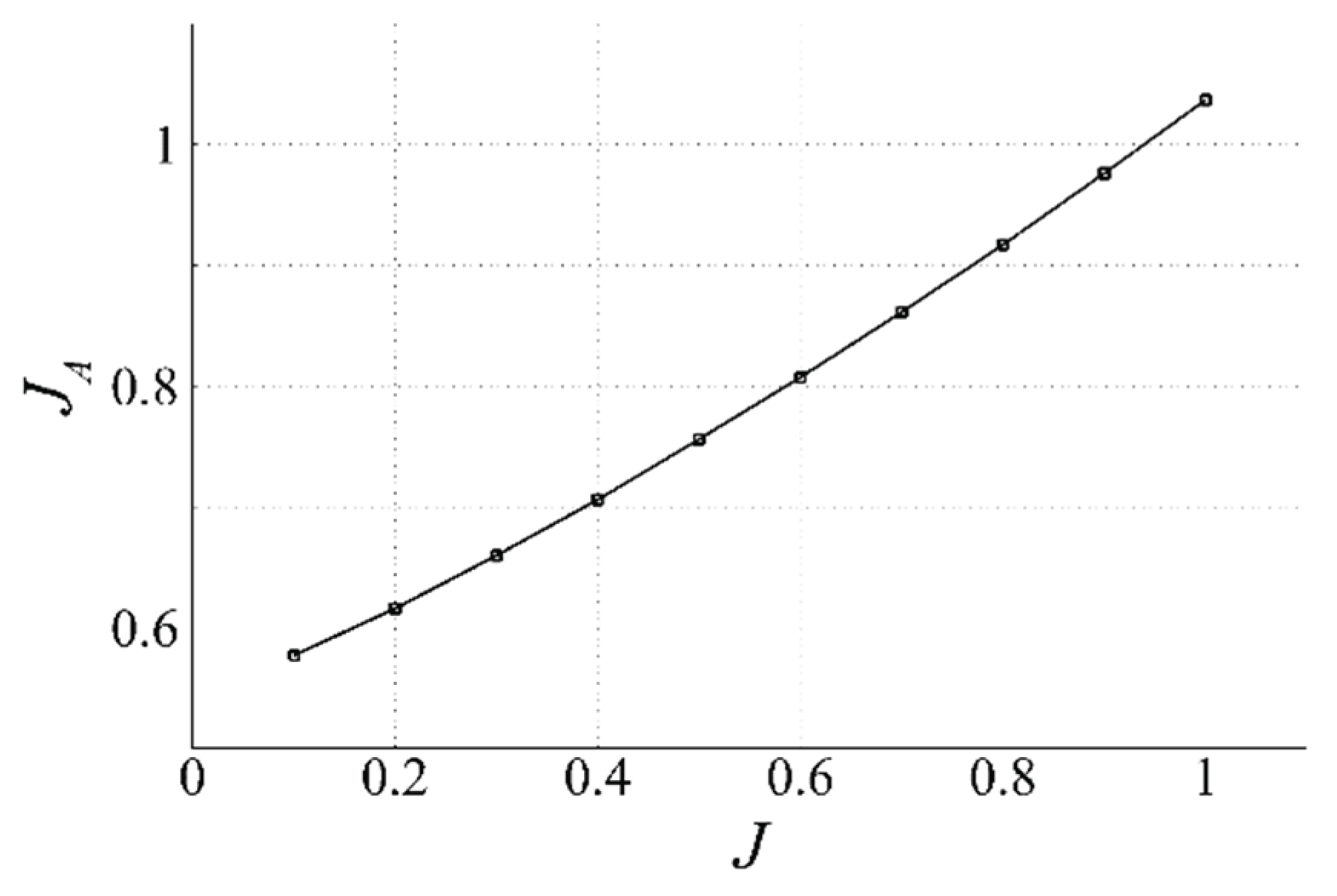

In the duct-jet propulsive system, deriving the regression formula for POW between the conventional advance coefficient and the propeller hydrodynamic properties without additionally measuring the flow velocity at the duct inlet leads to difficulties in body-force implementation. This is because the propeller inflow plane, which is typically prescribed at the propeller inlet, exhibits a flow velocity that increases significantly compared to the hull-relative velocity when a duct is present.

To address this, an additional regression relation is introduced between the hull-relative advance coefficient

and the duct-inlet advance coefficient

. Accordingly, the regression formula for the propeller hydrodynamic properties is expressed in terms of

rather than

. The computation of

is performed at the inflow plane shown previously in

Figure 5, and the relation between

and

is presented in

Figure 9 and

Table 9. In Equation (5a), the values of

and

are set to 0.5123 and 0.5096, respectively. The resulting variations in the POW coefficients are summarized in

Table 10 and

Table 11. The effect of grid resolution on the computed

values is found to be negligible.

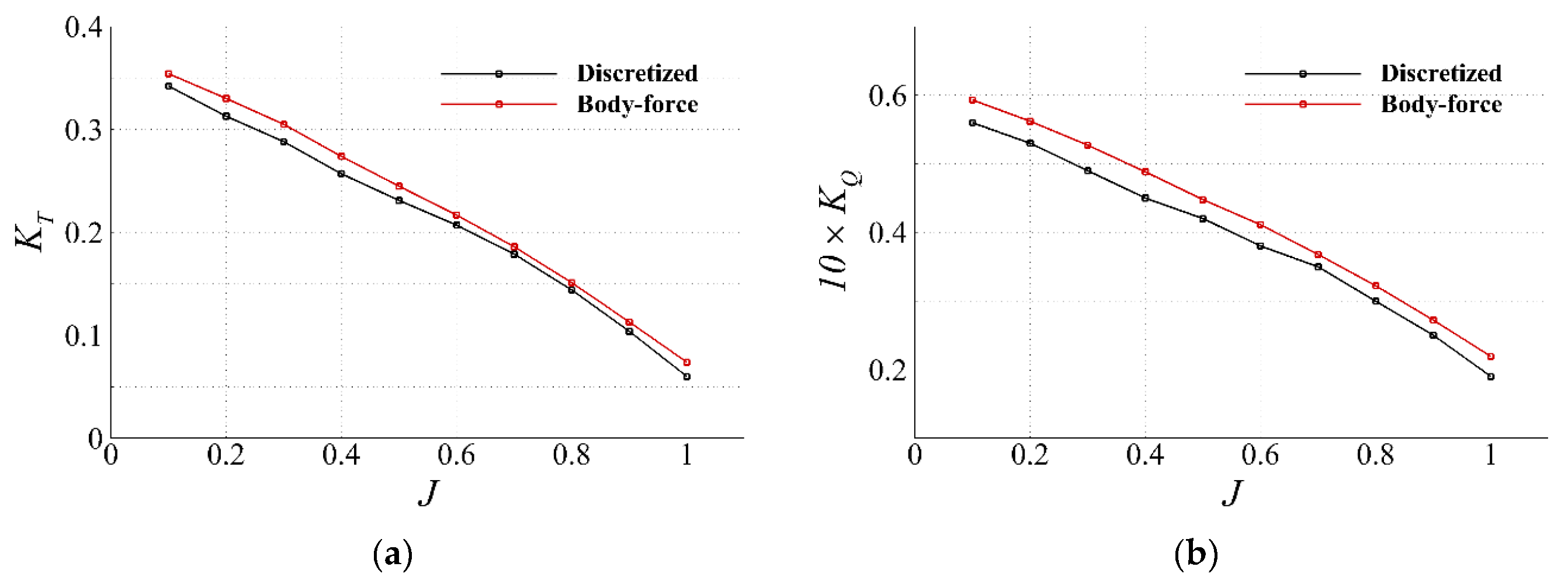

The body-force modeling is carried out using the POW regression formula based on

, and validation against the discretized propeller is performed through POW simulations.

Figure 10 presents a comparison of the hydrodynamic properties. For thrust, the body-force model shows an overestimation in the region of

, although the overall accuracy remains reasonable. In the case of torque, the body-force model generally exhibits an overestimation. This behavior appears unrelated to the accuracy of

measured for the discretized and body-force propellers, as shown in

Figure 11(d). Instead, it is considered to result from the interaction between the duct and the modified pressure field induced by the body-force propeller.

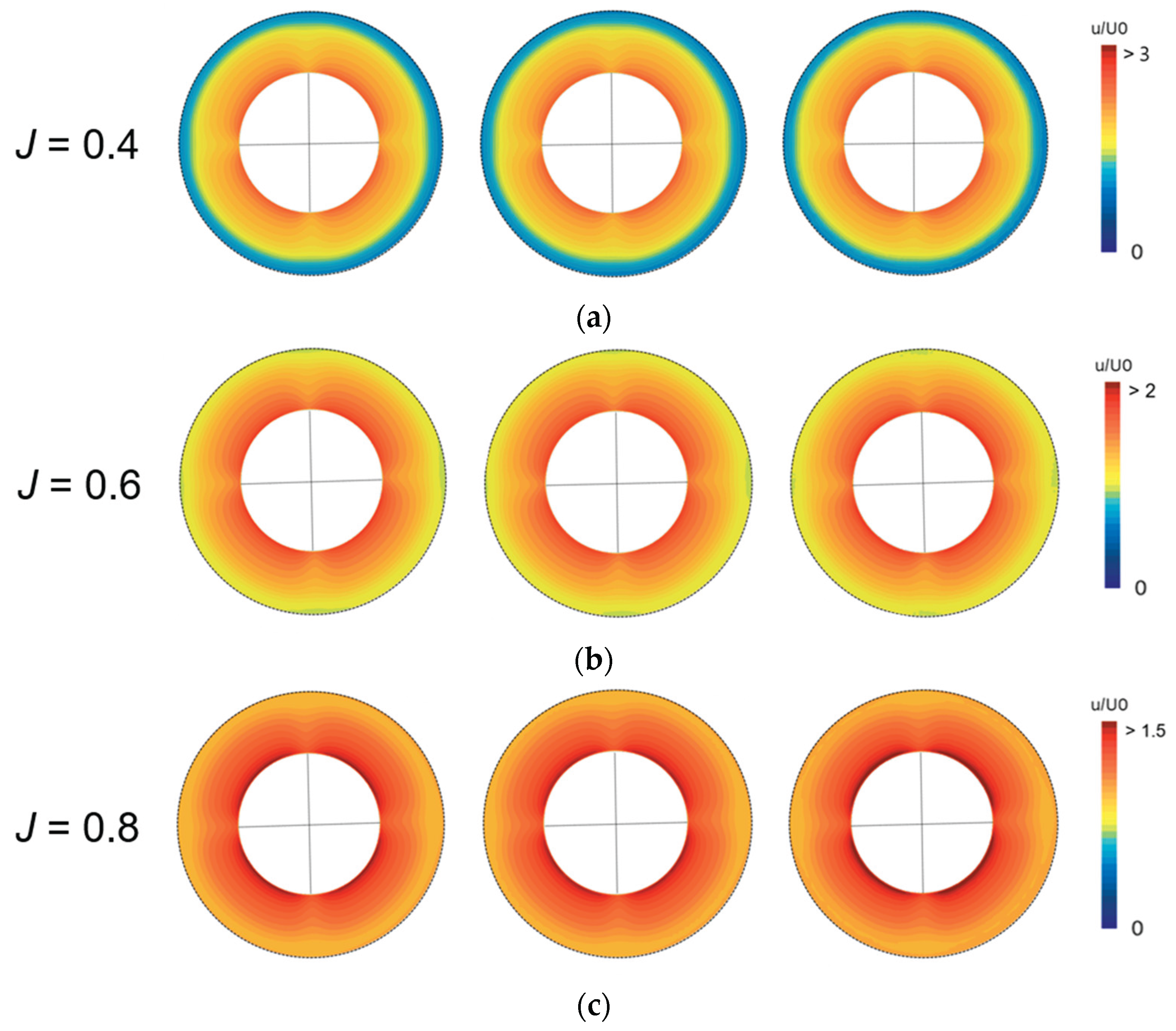

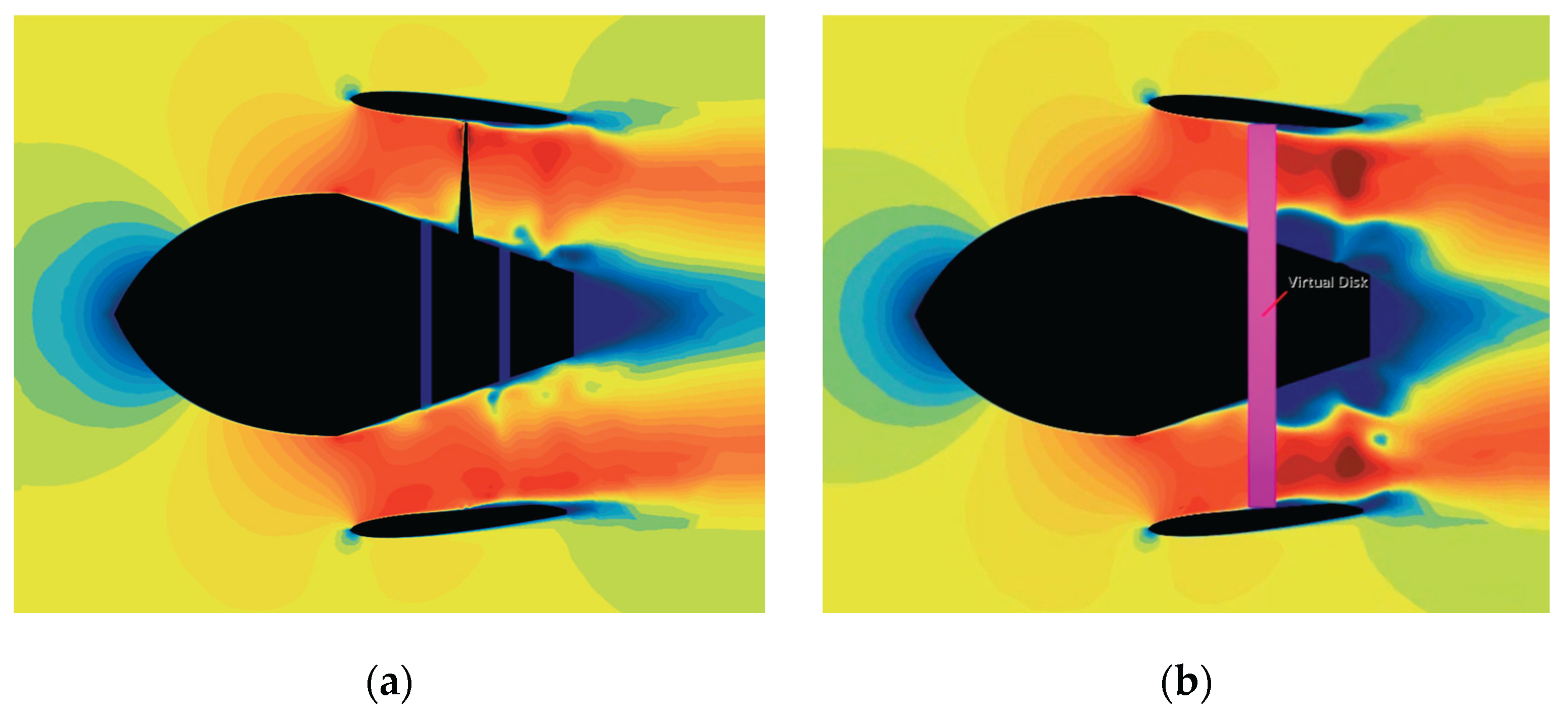

Since this issue is also related to grid resolution, the present study proceeds without further debugging to maintain a practical approach. Ultimately, torque does not influence the 3DOF simulations, and therefore no additional corrective measures are taken. Body-force modeling is not only important for predicting thrust but also for reproducing the flow field around the hull with sufficient fidelity, particularly because the rudder and propulsion system are usually placed in close proximity. As confirmed at representative advance coefficients, the body-force model predicts a velocity distribution similar to that of the discretized propeller (

Figure 12).

5.3. Resistance Test

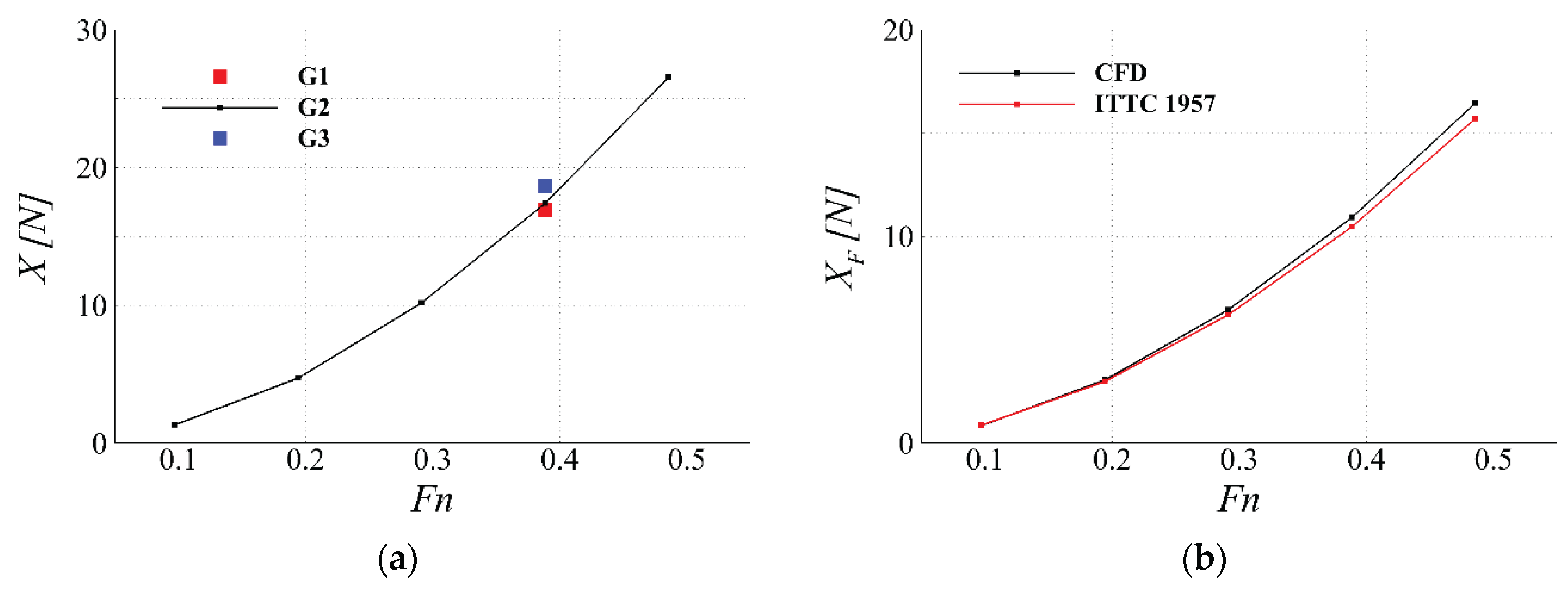

The resistance test (

Figure 13) focuses primarily on constructing Equation (11) and performing CFD data verification for AUV hull and rudders using the grid triplet.

In this setup, the duct is included, while the propeller is excluded to enable replacement with the body-force model. The simulation results are presented in

Figure 14. In addition, the measured frictional resistance during straight-ahead motion of the AUV shows close agreement with the ITTC 1957 regression formula (frictional resistance coefficient,

commonly used for ships. This suggests that if pressure-field regression is carried out for an AUV digital twin, the frictional resistance can be modeled as a major feature through a simple regression expression.

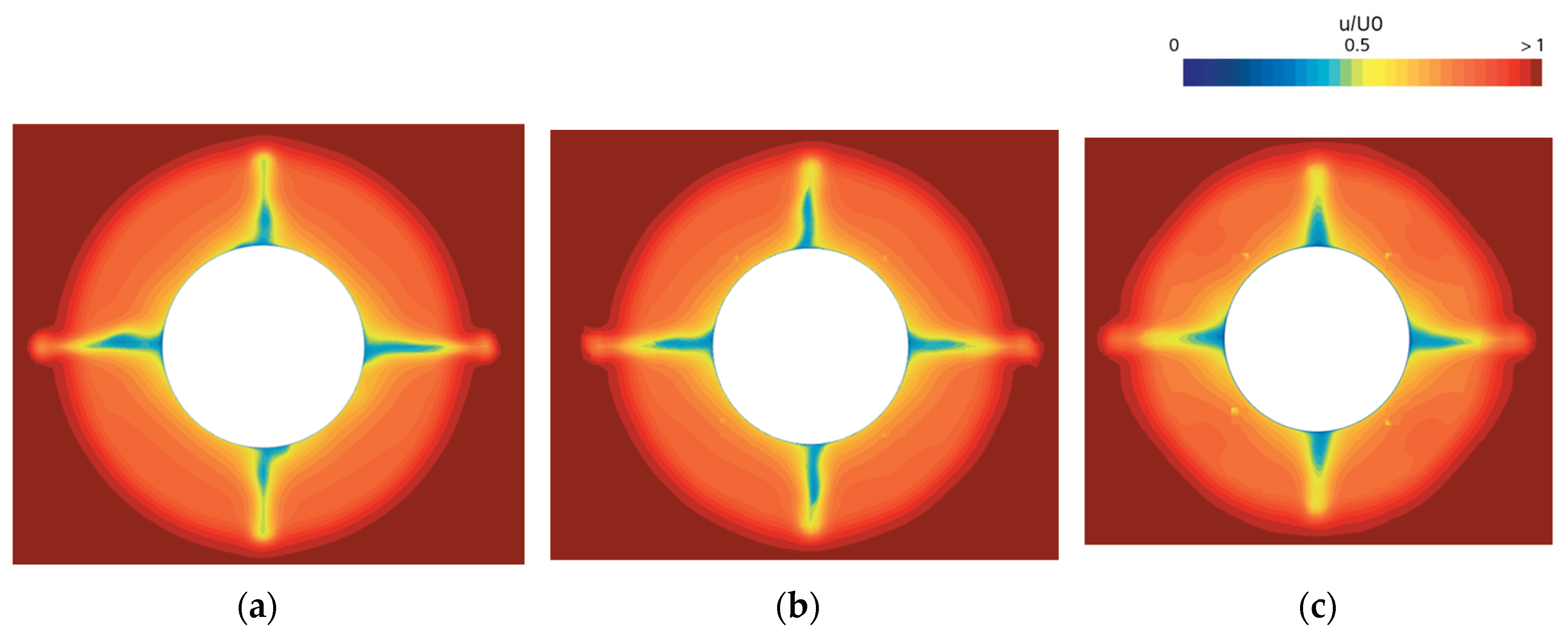

The coefficients applied in Equation (11) are listed in

Table 12. Furthermore, the grid dependency of the axial flow speed at the duct inlet, expressed as

, is examined (

Figure 15). Qualitatively, it is confirmed that the G2 resolution yields results nearly identical to those of the G1 grid.

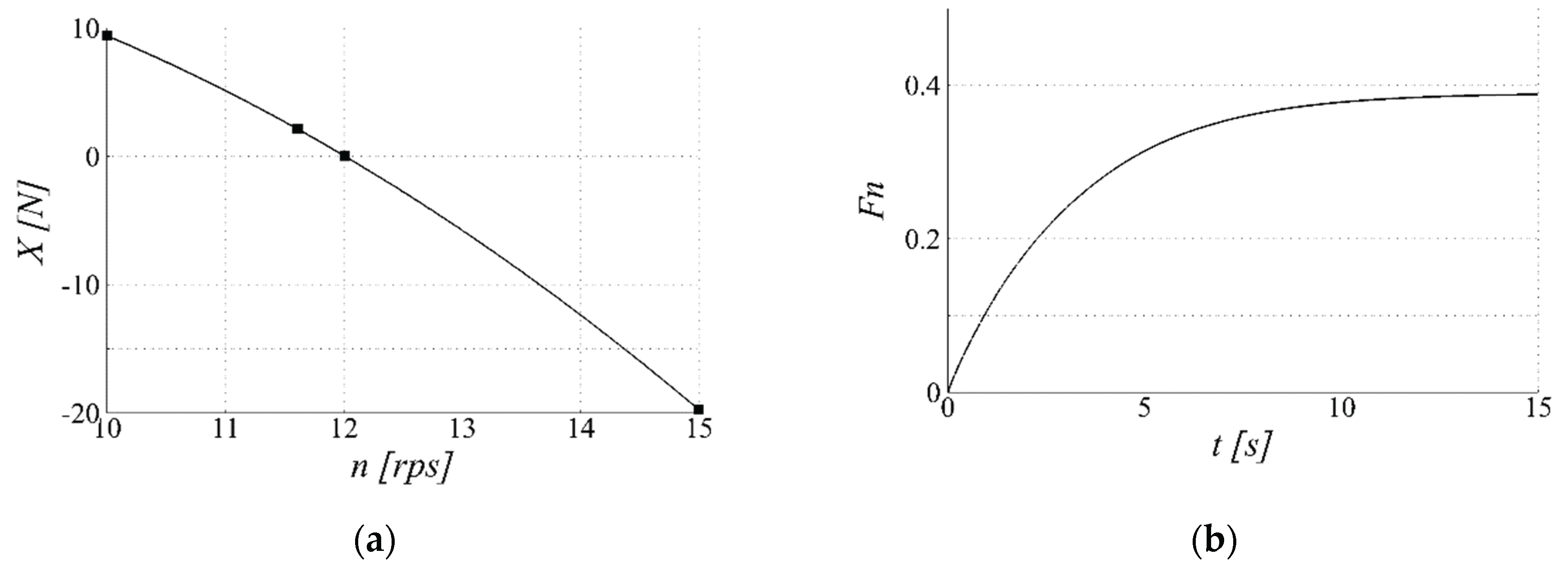

5.4. Self-Propulsion Test

In the self-propulsion test (

Figure 16), the body-force propulsion is implemented and the simulation is carried out in 1DOF. At the target Froude number, the propeller rotational speed

, the value of

used in Equation (8b), and the value of

used in Equation (12a) are prescribed. As shown in

Figure 17(a), three cases using different

are tested, and the final

is determined at the point where the longitudinal force coefficient

becomes zero. The propeller RPS obtained from CFD is directly applied in subsequent free-running simulations.

The values of and , however, are determined differently. First, the surrogate expressions required for the self-propulsion test (Equations (5), (8), (9), (11), and (12a)) are constructed. Then, by executing the surrogate and adjusting and , values of , , and comparable to those from CFD are identified. The final adjusted and values are 0.233 and 0.13, respectively.

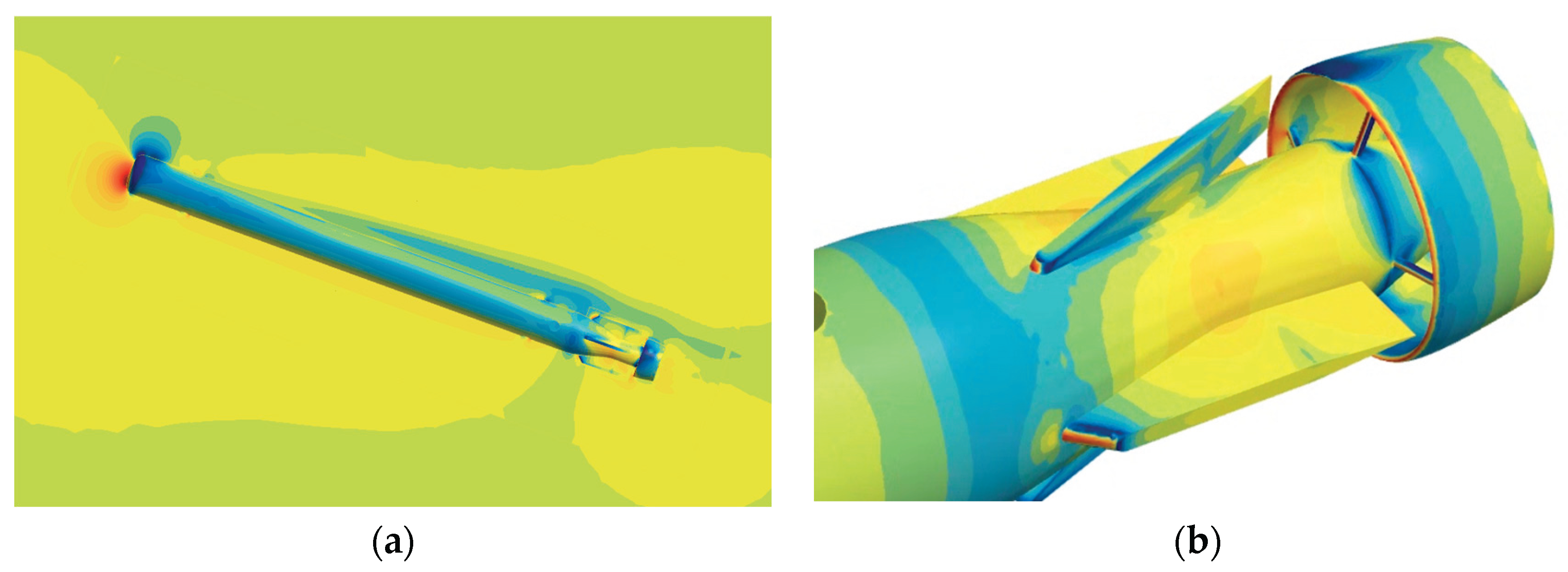

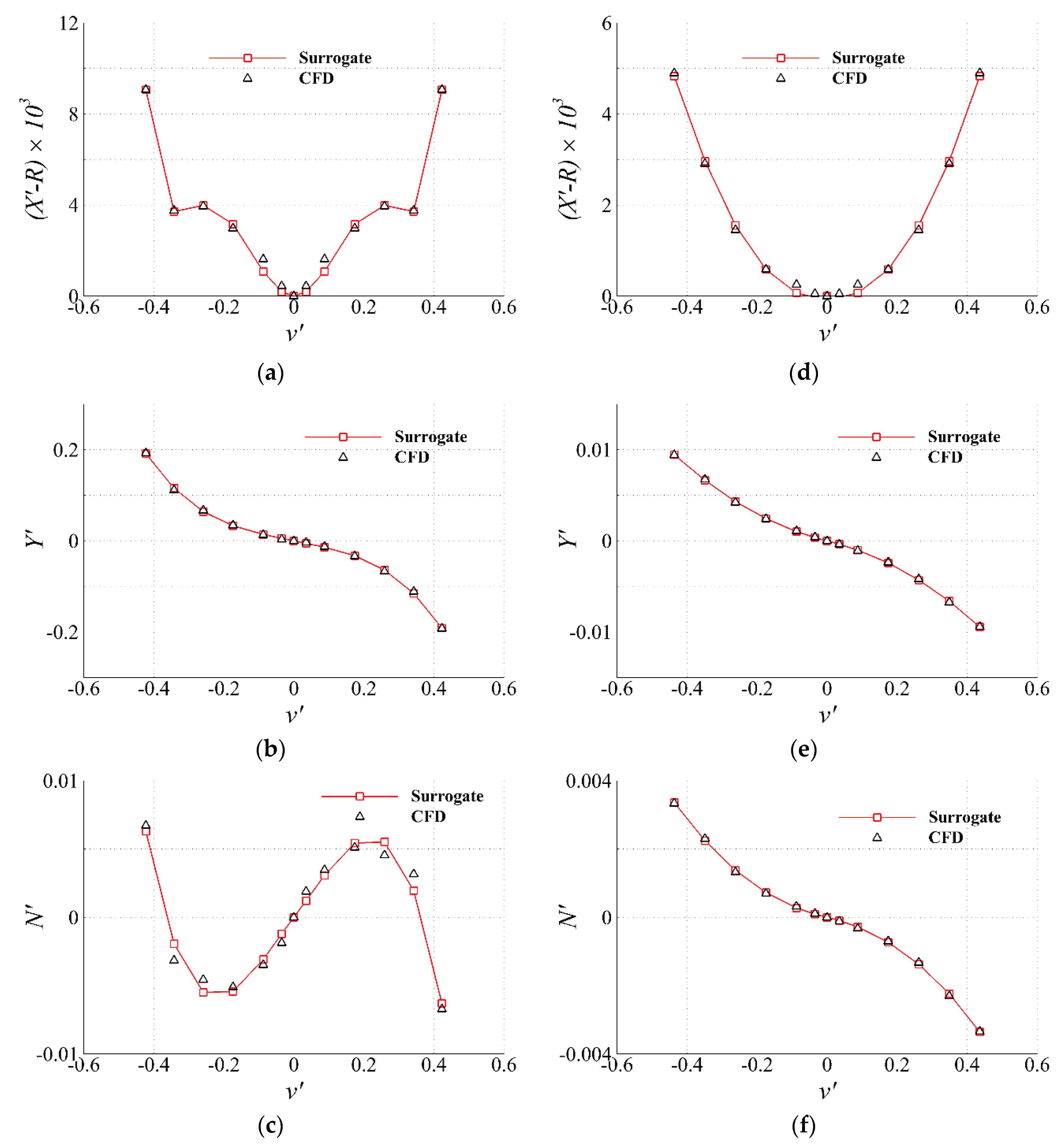

5.5. Static-Drift and Control-Fin Tests

In the static-drift test (

Figure 18(a)), the maneuvering coefficients associated with lateral velocity

are identified, while in the control-fin test (

Figure 18(b)), the maneuvering coefficients associated with the vertical rudder angle

are determined using the least-squares method. The reconstructed forces and moments based on the fitted coefficients are presented in

Figure 19. The coefficients applied in Surrogate Equation (12) are summarized in

Table 14 and

Table 15.

Table 13.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from static-drift simulations.

Table 13.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from static-drift simulations.

| Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

|

0.1574 |

|

-0.1686 |

|

0.0331 |

|

-1.9794 |

|

0.2658 |

|

0.0616 |

|

7.7387 |

|

-2.2175 |

|

-0.4145 |

Table 14.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from control-fin simulations.

Table 14.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from control-fin simulations.

| Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

|

-0.0018 |

|

-0.0094 |

|

-0.0023 |

|

0.0294 |

|

-0.0245 |

|

-0.0093 |

| |

|

|

-0.0082 |

|

-0.0069 |

Table 15.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from pure-sway simulations.

Table 15.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from pure-sway simulations.

| Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

|

-0.129 |

|

-0.0088 |

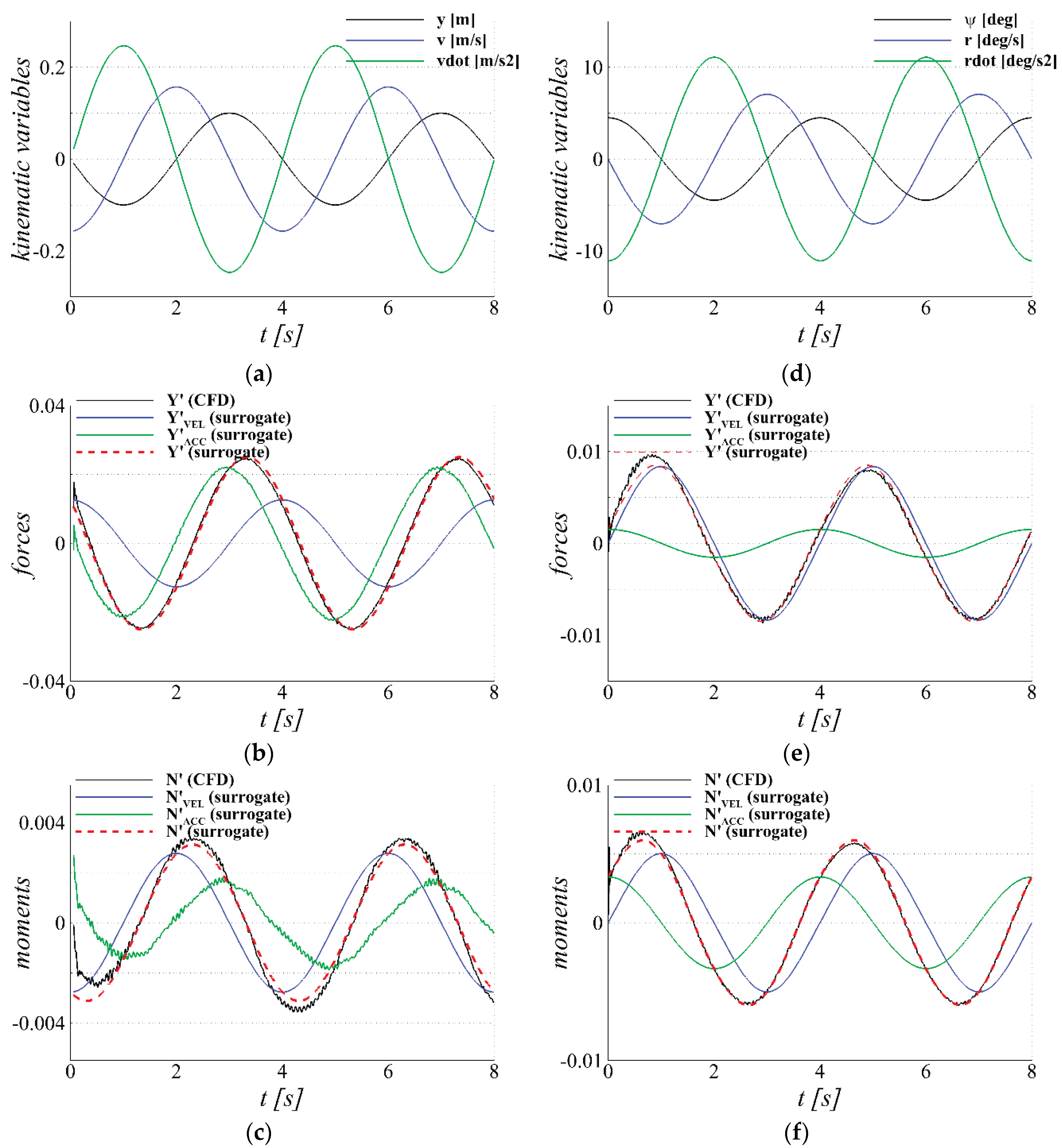

5.6. Pure-Sway and Pure-Yaw Tests

In the pure-sway test, the maneuvering coefficients associated with lateral acceleration

are obtained, while in the pure-yaw test, the coefficients associated with yaw rate

and yaw acceleration

are identified. As introduced in the test matrix (

Table 5), the pure-sway test is conducted by imposing a sinusoidal sway motion at the target Froude number, and the pure-yaw test is performed by superimposing a sinusoidal yaw motion (

Figure 20(a) and (d)). The resulting forces and moments during pure-sway are presented in

Figure 20(b) and (c), while those during pure-yaw are shown in

Figure 20(e) and (f).

In the pure-sway test, the velocity-dependent forces and moments (

,

) are subtracted from the measured total force and moment (

,

, respectively, using the surrogate regression expressions obtained from the static-drift test, and the acceleration-dependent terms (

,

) are identified through the least-squares method (

Table 15). In the pure-yaw test, both the velocity-dependent and acceleration-dependent forces and moments are simultaneously determined using the least-squares method (

Table 16).

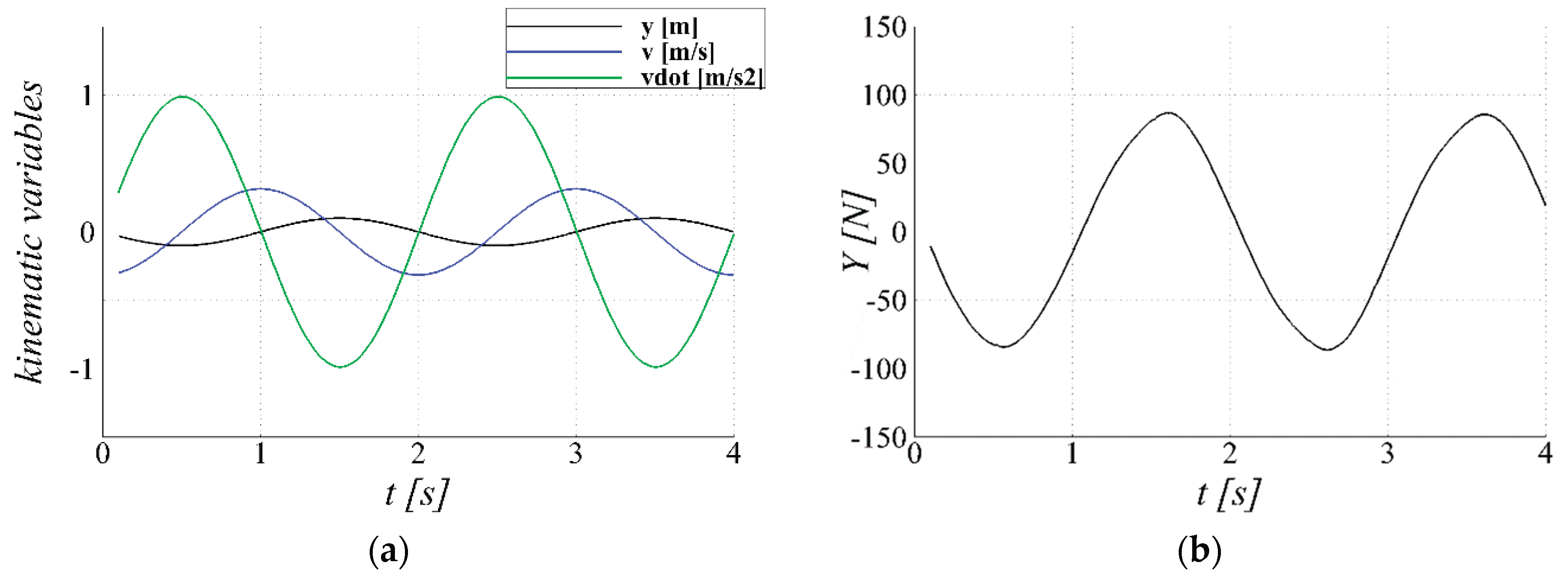

5.7. Forced-Oscillation

In the forced-oscillation test, the AUV is subjected to a sinusoidal sway motion at

to determine the added mass coefficient

(

Figure 21). To obtain the

, the simulation is briefly modeled assuming that the measured force is the sum of force affected by damping and inertia, which are assumed to be proportional to velocity and acceleration as follows.

where

denotes damping coefficient. Since the acceleration term exhibits sine function behavior, the side force is convoluted with the same sine function sharing the same frequency to obtain the

. The coefficient

is found to be negligible in the results and is therefore not reported. Since added mass does not vary significantly, the period and amplitude of the sinusoidal input are selected to represent the typical operating range of the AUV. The non-dimensionalized added moment of inertia in z-direction 0.009 from [X] is directly used for the estimation of dimensional value (

). A more accurate estimation of the AUV’s

would require a forced-oscillation test in yaw.

7. Conclusion

In this study, a surrogate model for AUV maneuvering is established using CFD, and its accuracy is assessed. The required CFD simulations are minimized, while the surrogate is analytically constructed through additional kinematic relations and a limited set of empirical parameters. The free-running predictions obtained from the surrogate demonstrate reasonable accuracy. It is anticipated that this framework can serve as a backbone for future developments, such as more advanced rudder models, propeller models incorporating side-force effects, and full 6DOF extensions.

In the free-running simulations, it is observed that the rudders of the current AUV design are relatively small, resulting in limited lifting force and confining zigzag motions to small values of drift angle . This finding implies the need for further surrogate validation at larger , particularly when side thruster models are incorporated. At the preliminary design stage, CFD proves to be valuable not only for predicting the flow field, but also for reproducing diverse scenarios through integration with controllers and propeller models. This reaffirms the advantage of predicting physical data directly from geometric information.

Nevertheless, the intrinsic limitation of high computational cost remains. Therefore, the present approach is expected to serve as a reduced-order model for hydrodynamic force prediction, particularly when coupled with control models or employed as training data for multivariate system identification.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.K., J.S. and H.C.; methodology, D.K. and J.S.; software, Y.K.; validation, Y.K. and D.K.; formal analysis, Y.K. and D.K.; investigation, Y.K. and D.K.; resources, J.S. and H.C.; data curation, D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.; writing—review and editing, D.K.; visualization, Y.K. and D.K.; supervision, D.K.; project administration, H.C.; funding acquisition, H.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Target AUV model geometry: (a) Fully appended AUV; (b) Vertical (up) and horizontal (down) rudders; (c) Propulsion region showing both duct and propeller blades. The clearance between the propeller rotor and AUV hull’s tail part is intentionally imposed to facilitate CFD computation.

Figure 1.

Target AUV model geometry: (a) Fully appended AUV; (b) Vertical (up) and horizontal (down) rudders; (c) Propulsion region showing both duct and propeller blades. The clearance between the propeller rotor and AUV hull’s tail part is intentionally imposed to facilitate CFD computation.

Figure 2.

Surface grids on AUV and y=0 plane: (a) near AUV nose; (b) near stern; (c) propeller blades; (d) propulsion system including a duct and struts.

Figure 2.

Surface grids on AUV and y=0 plane: (a) near AUV nose; (b) near stern; (c) propeller blades; (d) propulsion system including a duct and struts.

Figure 3.

Overset configuration demonstration: Overset regions for 4 rudders are shown

Figure 3.

Overset configuration demonstration: Overset regions for 4 rudders are shown

Figure 4.

Computation domain size.

Figure 4.

Computation domain size.

Figure 5.

Sectional area for obtaining averaged axial-speed at the duct inlet.

Figure 5.

Sectional area for obtaining averaged axial-speed at the duct inlet.

Figure 6.

Surrogate algorithm flowchart.

Figure 6.

Surrogate algorithm flowchart.

Figure 7.

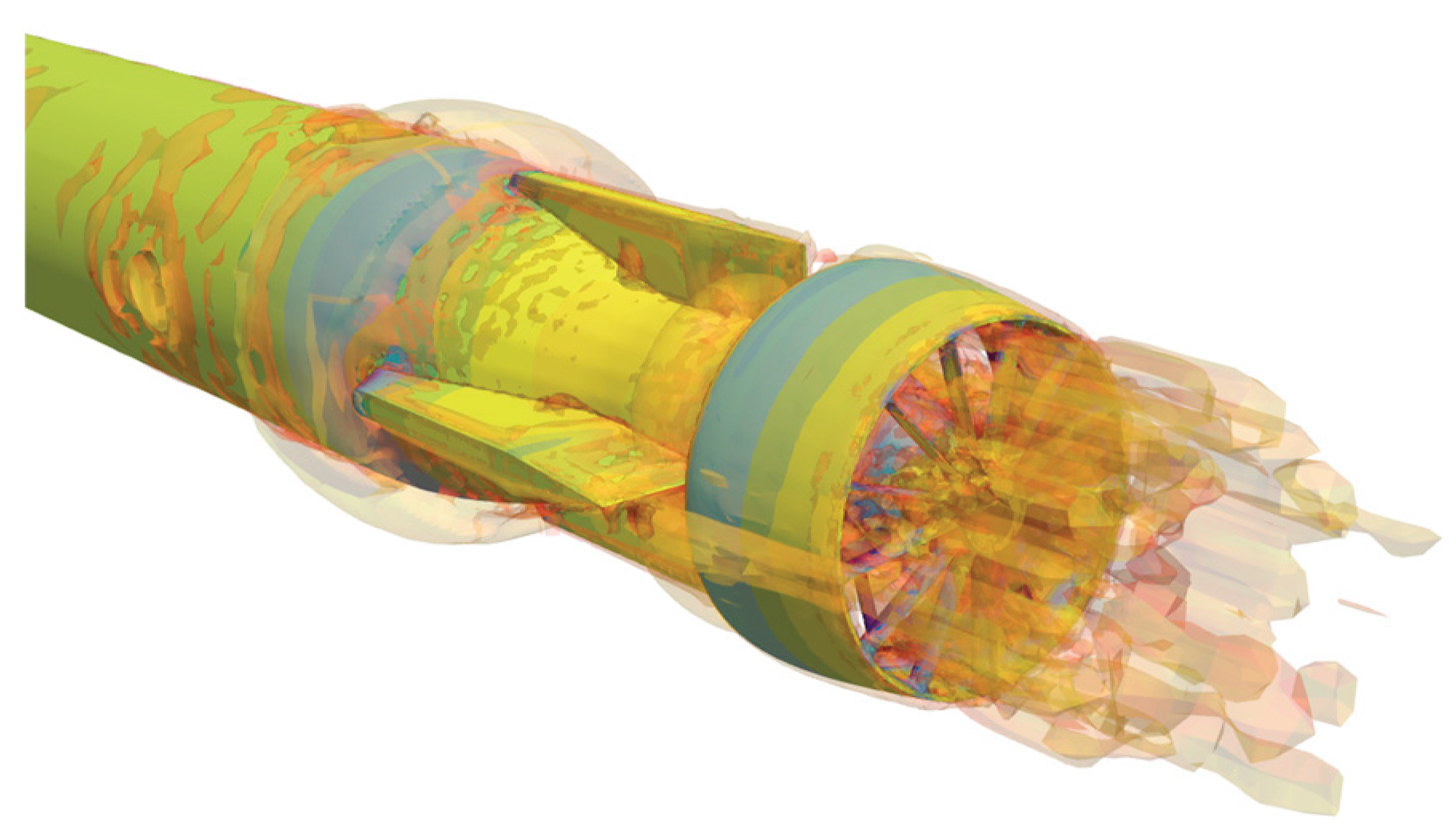

Propeller wake in POW simulation with a discretized propeller model (Q=10).

Figure 7.

Propeller wake in POW simulation with a discretized propeller model (Q=10).

Figure 8.

POW characteristic curves obtained via grid triplets of discretized propeller model: (a) thrust coefficient; (b) torque coefficient; (c) propeller open water efficiency; (d) duct resistance.

Figure 8.

POW characteristic curves obtained via grid triplets of discretized propeller model: (a) thrust coefficient; (b) torque coefficient; (c) propeller open water efficiency; (d) duct resistance.

Figure 9.

Correlation between and achieved from POW simulations using G2 DP model.

Figure 9.

Correlation between and achieved from POW simulations using G2 DP model.

Figure 10.

Grid triplet’s axial inflow speed distribution at duct inlet (left: G1, middle: G2, right: G3): (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

Figure 10.

Grid triplet’s axial inflow speed distribution at duct inlet (left: G1, middle: G2, right: G3): (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

Figure 11.

Validation of CFD BF model against DP model: (a) thrust coefficient; (b) torque coefficient; (c) propeller open-water efficiency; (d) advance coefficient at duct inlet.

Figure 11.

Validation of CFD BF model against DP model: (a) thrust coefficient; (b) torque coefficient; (c) propeller open-water efficiency; (d) advance coefficient at duct inlet.

Figure 12.

Axial inflow speed distribution near the propulsion system: (a) DP model; (b) BF model.

Figure 12.

Axial inflow speed distribution near the propulsion system: (a) DP model; (b) BF model.

Figure 13.

Pressure distribution at the steady state of resistance simulation.

Figure 13.

Pressure distribution at the steady state of resistance simulation.

Figure 14.

Resistance test results: (a) resistance curve against Froude number; (b) frictional resistance curve against Froude number.

Figure 14.

Resistance test results: (a) resistance curve against Froude number; (b) frictional resistance curve against Froude number.

Figure 15.

Grid triplet’s axial inflow speed at the duct inlet during resistance simulation: (a) G1; (b) G2; (c) G3.

Figure 15.

Grid triplet’s axial inflow speed at the duct inlet during resistance simulation: (a) G1; (b) G2; (c) G3.

Figure 16.

Pressure distribution and propeller wake (Q = 10) during self-propulsion simulation.

Figure 16.

Pressure distribution and propeller wake (Q = 10) during self-propulsion simulation.

Figure 17.

Self-propulsion simulation results at target Froude number: (a) propeller rotational speed tested for finding self-propulsion point; (b) time-history of ship speed represented as instantaneous Froude number during self-propulsion simulation using zero initial ship speed and propeller rotational speed found at self-propulsion point.

Figure 17.

Self-propulsion simulation results at target Froude number: (a) propeller rotational speed tested for finding self-propulsion point; (b) time-history of ship speed represented as instantaneous Froude number during self-propulsion simulation using zero initial ship speed and propeller rotational speed found at self-propulsion point.

Figure 18.

Pressure distributions: (a) static-drift (; (b) control-fin simulation (.

Figure 18.

Pressure distributions: (a) static-drift (; (b) control-fin simulation (.

Figure 19.

Measured forces and moment and regression curve for Surrogate in static-drift simulations: (a) surge force; (b) sway force; (c) yaw moment, and control-fin simulation: (d) surge force; (e) sway force; (f) yaw moment.

Figure 19.

Measured forces and moment and regression curve for Surrogate in static-drift simulations: (a) surge force; (b) sway force; (c) yaw moment, and control-fin simulation: (d) surge force; (e) sway force; (f) yaw moment.

Figure 20.

The measured time-histories: (a) sway displacement, velocity and acceleration from both pure-sway and pure-yaw; (b) sway force from pure-sway; (c) yaw moment from pure-sway; (d) yaw displacement, velocity and acceleration from pure-yaw; (e) sway force from pure-yaw; (f) yaw moment from pure-yaw.

Figure 20.

The measured time-histories: (a) sway displacement, velocity and acceleration from both pure-sway and pure-yaw; (b) sway force from pure-sway; (c) yaw moment from pure-sway; (d) yaw displacement, velocity and acceleration from pure-yaw; (e) sway force from pure-yaw; (f) yaw moment from pure-yaw.

Figure 21.

The measured time-histories during forced-oscillation simulation: (a) sway displacement, velocity and acceleration; (b) sway force.

Figure 21.

The measured time-histories during forced-oscillation simulation: (a) sway displacement, velocity and acceleration; (b) sway force.

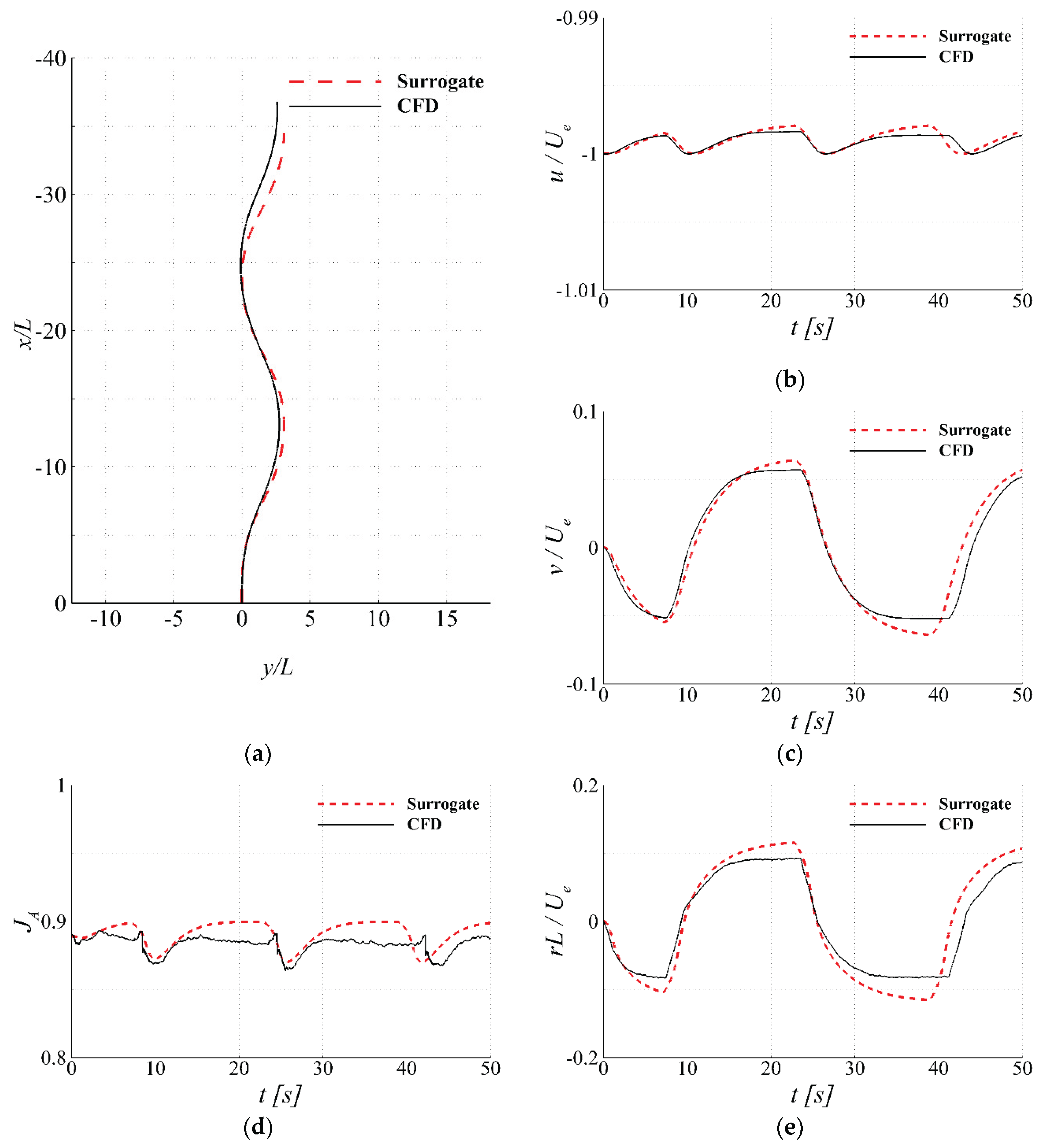

Figure 22.

Time-histories of kinematic variables and advance coefficient at the duct inlet during free-running zigzag simulations: (a) trajectory; (b) ship axial speed; (c) ship lateral speed; (d) advance coefficient at the duct inlet; (e) yaw speed; (f) drift-angle; (g) yaw and rudder angles.

Figure 22.

Time-histories of kinematic variables and advance coefficient at the duct inlet during free-running zigzag simulations: (a) trajectory; (b) ship axial speed; (c) ship lateral speed; (d) advance coefficient at the duct inlet; (e) yaw speed; (f) drift-angle; (g) yaw and rudder angles.

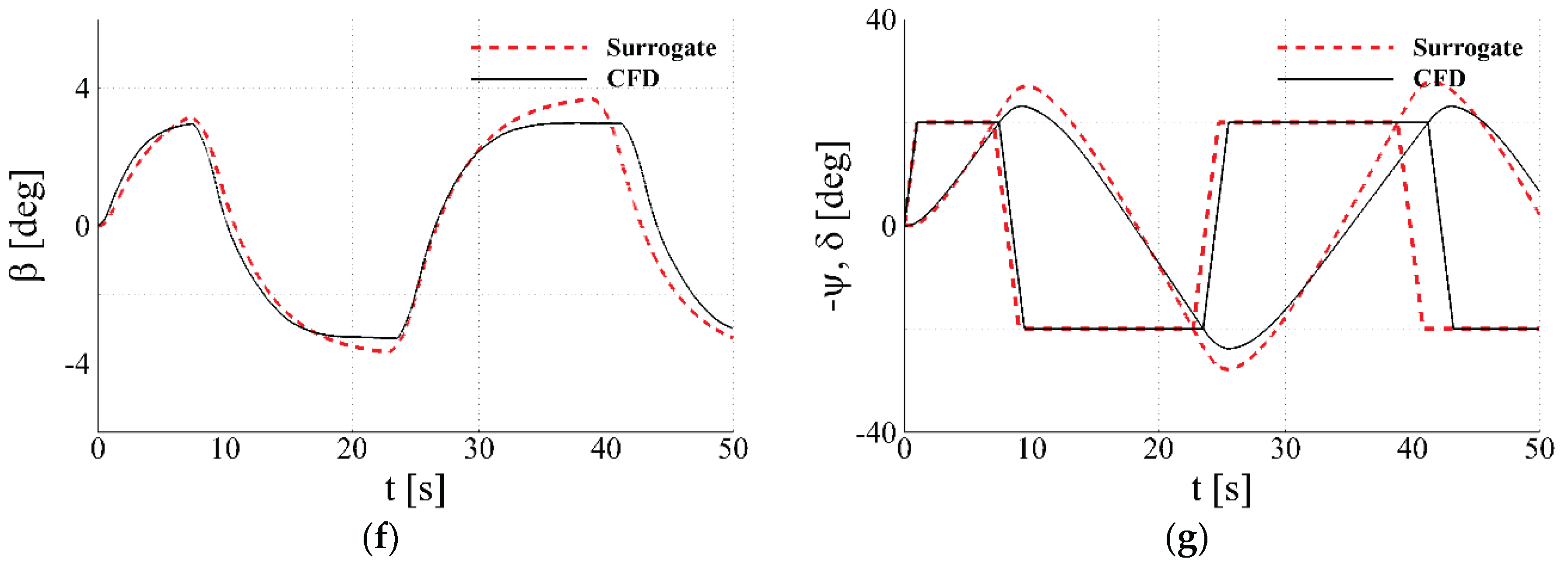

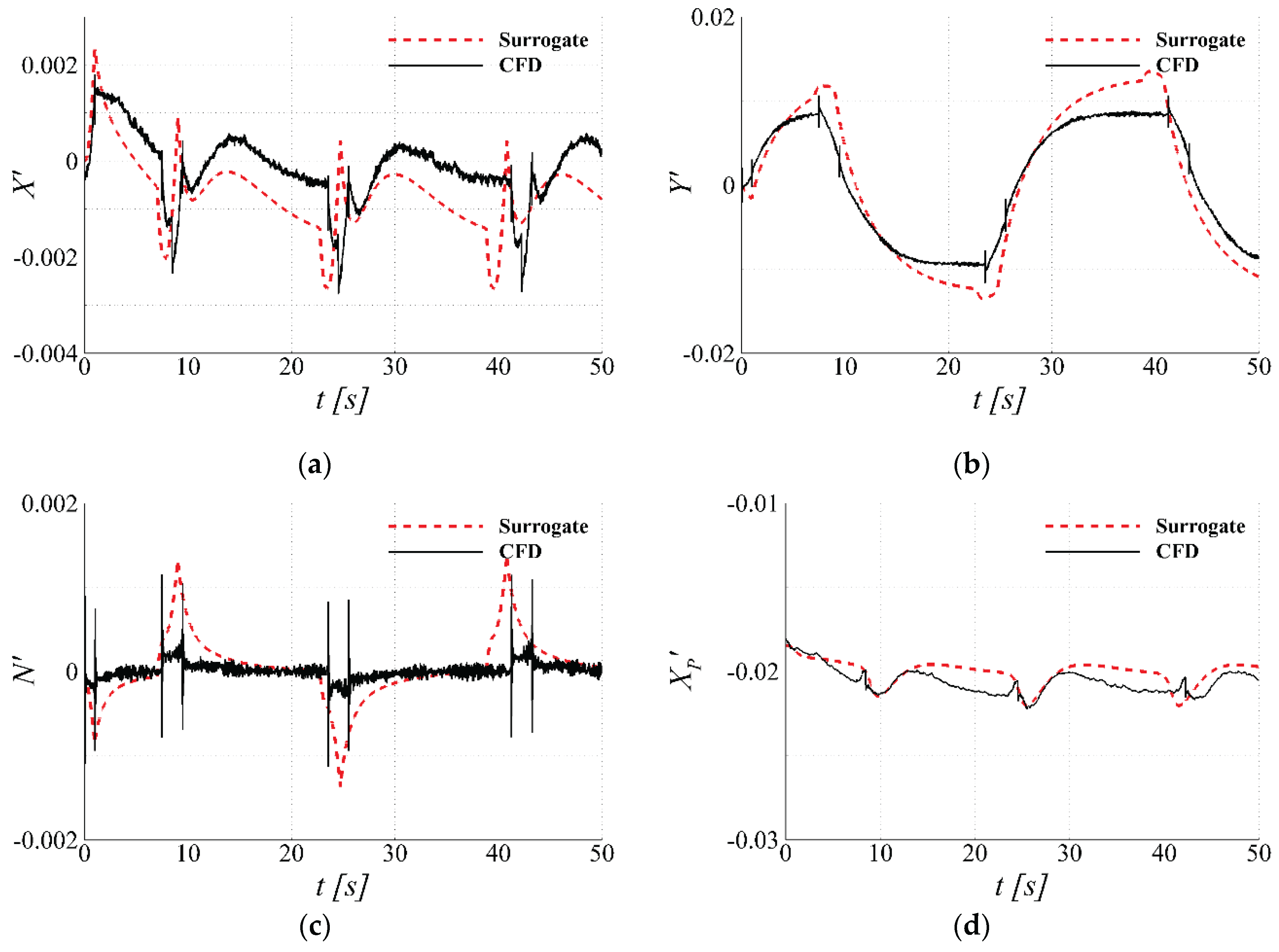

Figure 23.

Time-histories of forces and moment during free-running zigzag simulations: (a) total surge force; (b) total sway force; (c) total yaw moment; (d) propeller thrust.

Figure 23.

Time-histories of forces and moment during free-running zigzag simulations: (a) total surge force; (b) total sway force; (c) total yaw moment; (d) propeller thrust.

Table 1.

Main principals (Fully-attached AUV)

Table 1.

Main principals (Fully-attached AUV)

| Description |

Symbol |

Factor1

|

Value2

|

| Breadth |

|

|

0.074 |

| Mass |

|

|

3.830e-3

|

| Center of gravity3 (x-dir.) |

|

|

0.463 |

| Radius of gyration (z-dir.) |

|

|

0.166 |

| Moment of inertia (z-dir.) |

|

|

1.059e-4

|

| Location of rudder axis3 (x-dir.) |

|

|

0.904 |

| Location of propeller center3 (x-dir.) |

|

|

0.982 |

| Propeller diameter |

|

|

0.063 |

Table 2.

Number of grid points of grid triplet for POW simulation.

Table 2.

Number of grid points of grid triplet for POW simulation.

| Region |

|

# of cells [M] |

|

| G1 |

G2 |

G3 |

| Blade |

0.79 |

0.41 |

0.24 |

| Duct |

1.67 |

0.83 |

0.46 |

| Background |

0.07 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

| Total |

2.53 |

1.28 |

0.73 |

Table 3.

Number of grid points of grid triplet for simulations including hull and rudders.

Table 3.

Number of grid points of grid triplet for simulations including hull and rudders.

| Region |

|

# of cells [M] |

|

| G1 |

G2 |

G3 |

| Hull* |

3.02 |

1.47 |

0.78 |

| Rudders |

0.86 |

0.35 |

0.14 |

| Background |

0.17 |

0.07 |

0.03 |

| Total |

4.05 |

1.89 |

0.95 |

Table 4.

Boundary conditions.

Table 4.

Boundary conditions.

| BC |

|

|

* |

|

| Inlet |

|

Extrapolated |

|

|

| Exit |

Extrapolated |

Extrapolated |

Zero-gradient |

Zero-gradient |

| Wall |

Grid velocity |

Zero-gradient |

Zero-gradient |

Zero-gradient |

Table 5.

Simulation test-matrix.

Table 5.

Simulation test-matrix.

| Simulation |

Condition |

Grid system |

| Hydrostatic |

Static |

G2 |

| POW (discretized) |

= 0.1 - 1.0 |

G1, G2, G3 |

| POW (body-force) |

= 0.1 - 1.0 |

G2 |

| Resistance |

Fn = 0.097, 0.19, 0.29, 0.39, 0.48 |

G1, G2, G3 |

| Self-propulsion1

|

Fn = 0.39 |

G2 |

| Static-drift |

= 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 [deg] |

G2 |

| Control-fin |

= 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 [deg] |

G2 |

| Pure-sway |

y = (0.1)sin(0.5πt), Fn = 0.39 |

G2 |

| Pure-yaw2

|

ψ=(0.1/)cos(0.5πt) |

G2 |

| Forced-oscillation |

y = (0.1)sin(πt), Fn = 0 |

G2 |

| Zigzag1

|

= +20/20 |

G2 |

Table 6.

results from POW simulations using grid triplets with the DP model.

Table 6.

results from POW simulations using grid triplets with the DP model.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.1 |

0.346 |

0.342 |

0.348 |

-1.1 |

1.6 |

-0.72 |

| 0.2 |

0.315 |

0.313 |

0.324 |

-0.7 |

3.5 |

-0.2 |

| 0.3 |

0.29 |

0.288 |

0.292 |

-0.8 |

1.5 |

-0.51 |

| 0.4 |

0.266 |

0.257 |

0.259 |

-3.3 |

0.6 |

-5.04 |

| 0.5 |

0.241 |

0.231 |

0.233 |

-3.8 |

0.5 |

-7.11 |

| 0.6 |

0.213 |

0.207 |

0.208 |

-2.8 |

0.4 |

-7.91 |

| 0.7 |

0.184 |

0.179 |

0.177 |

-2.7 |

-1.2 |

2.25 |

| 0.8 |

0.15 |

0.144 |

0.141 |

-4.3 |

-1.9 |

2.24 |

| 0.9 |

0.11 |

0.104 |

0.1 |

-5.8 |

-3.2 |

1.82 |

| 1 |

0.065 |

0.06 |

0.057 |

-8.3 |

-4.8 |

1.73 |

| Abs. Ave.* |

|

|

|

3.4 |

1.9 |

|

Table 7.

results from POW simulations using grid triplets with the DP model .

Table 7.

results from POW simulations using grid triplets with the DP model .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.1 |

0.0554 |

0.056 |

0.0577 |

1 |

3.1 |

0.33 |

| 0.2 |

0.052 |

0.0525 |

0.0549 |

1 |

4.6 |

0.22 |

| 0.3 |

0.0492 |

0.0495 |

0.0505 |

0.6 |

2.1 |

0.29 |

| 0.4 |

0.0459 |

0.0452 |

0.0456 |

-1.6 |

1 |

-1.63 |

| 0.5 |

0.0425 |

0.0416 |

0.0421 |

-2.1 |

1.1 |

-1.81 |

| 0.6 |

0.0389 |

0.0384 |

0.039 |

-1.2 |

1.5 |

-0.79 |

| 0.7 |

0.035 |

0.0348 |

0.0352 |

-0.8 |

1.2 |

-0.65 |

| 0.8 |

0.0305 |

0.0302 |

0.0307 |

-1.2 |

1.8 |

-0.66 |

| 0.9 |

0.0252 |

0.0249 |

0.0256 |

-1 |

2.9 |

-0.35 |

| 1 |

0.0193 |

0.0192 |

0.0201 |

-0.5 |

4.7 |

-0.1 |

| Abs. Ave. |

|

|

|

1.1 |

2.4 |

|

Table 8.

results from POW simulations using grid triplets with the DP model .

Table 8.

results from POW simulations using grid triplets with the DP model .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 0.1 |

0.099 |

0.097 |

0.096 |

-2.1 |

-1.4 |

1.54 |

| 0.2 |

0.193 |

0.19 |

0.188 |

-1.7 |

-1 |

1.77 |

| 0.3 |

0.282 |

0.278 |

0.277 |

-1.4 |

-0.5 |

2.95 |

| 0.4 |

0.369 |

0.363 |

0.361 |

-1.7 |

-0.3 |

5.1 |

| 0.5 |

0.45 |

0.442 |

0.44 |

-1.8 |

-0.6 |

3.03 |

| 0.6 |

0.524 |

0.515 |

0.509 |

-1.6 |

-1.2 |

1.42 |

| 0.7 |

0.586 |

0.574 |

0.56 |

-2 |

-2.4 |

0.84 |

| 0.8 |

0.626 |

0.607 |

0.584 |

-3.1 |

-3.6 |

0.86 |

| 0.9 |

0.626 |

0.596 |

0.559 |

-4.8 |

-5.8 |

0.83 |

| 1 |

0.54 |

0.497 |

0.45 |

-7.9 |

-8.8 |

0.9 |

| Abs. Ave. |

|

|

|

2.8 |

2.6 |

|

Table 9.

, , and values measured from POW simulations using G2 DP model. .

Table 9.

, , and values measured from POW simulations using G2 DP model. .

|

|

|

|

| 0.1 |

0.255 |

1.472 |

0.577 |

| 0.2 |

0.510 |

1.571 |

0.616 |

| 0.3 |

0.765 |

1.684 |

0.660 |

| 0.4 |

1.020 |

1.802 |

0.706 |

| 0.5 |

1.275 |

1.927 |

0.756 |

| 0.6 |

1.530 |

2.059 |

0.807 |

| 0.7 |

1.785 |

2.195 |

0.861 |

| 0.8 |

2.040 |

2.339 |

0.917 |

| 0.9 |

2.295 |

2.488 |

0.976 |

| 1.0 |

2.550 |

2.644 |

1.037 |

Table 10.

Coefficients of POW characteristics regression curve built upon .

Table 10.

Coefficients of POW characteristics regression curve built upon .

| Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

|

0.3582 |

|

0.0582 |

|

-0.1993 |

|

-0.0256 |

|

-0.0937 |

|

-0.0128 |

Table 11.

Coefficients of POW characteristics regression curve built upon .

Table 11.

Coefficients of POW characteristics regression curve built upon .

| Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

|

0.6187 |

|

0.0919 |

|

-0.4329 |

|

-0.0551 |

|

-0.0981 |

|

-0.0140 |

Table 12.

Coefficients of resistance regression curve (

Figure 14(a)).

Table 12.

Coefficients of resistance regression curve (

Figure 14(a)).

| Coefficient |

Value |

|

-0.2792 |

|

6.5738 |

|

100.212 |

Table 16.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from pure-yaw simulations.

Table 16.

Coefficients of regression curves achieved from pure-yaw simulations.

| Coefficient |

Value |

Coefficient |

Value |

|

-0.04458 |

|

-0.02690 |

|

-0.03431 |

|

-0.01989 |

|

-0.00432 |

|

-0.00944 |