1. Introduction

Advanced chronic illnesses and terminal stages pose a significant challenge to public health and healthcare systems worldwide, not only due to their high prevalence but also because of the economic and emotional burden they impose on patients and their families. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 56.8 million people globally are in need of palliative care (PC), with an estimated 25.7 million requiring such care during their final year of life [

1].

Education plays a pivotal role in the development of the competencies necessary to deliver high-quality palliative care. Therefore, nursing education, must emphasize holistic care, conceptual knowledge, effective communication, interprofessional collaboration, and emotional preparedness for death. These components are essential to improve patient outcomes and to meet the growing demand for palliative services [

2,

3].

There is a growing consensus regarding the need to incorporate a standardized set of core subjects related to palliative care into undergraduate nursing curricula [

4]. However, this transformation remains unresolved, largely due to the multidimensional nature of palliative care, which complicates instructional planning. Moreover, several barriers hinder the effective integration of PC into nursing education programs, including curricular overload, a shortage of qualified faculty, and limited access to clinical practice settings. These constraints undermine confidence in clinical competencies, which are essential for providing interdisciplinary, ethical, and empathetic palliative care [

5,

6,

7].

From a pedagogical perspective, it is imperative to rethink the traditional paradigms of nursing education. This necessitates the adoption of innovative educational models that incorporate diverse pedagogical languages and strategies, such as simulation and multimodal learning. These approaches enable students to engage with and experience real-life care situations through multiple cognitive and experiential pathways [

8,

9].

Early curricular integration, combined with the reinforcement of experiential, practical, and pedagogical training, is key to enhancing knowledge in palliative care [

10]. The incorporation of gamification into MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) has emerged as an innovative pedagogical strategy by which to raise awareness and improve education in this field. By embedding game-based dynamics, mechanics, and elements, gamified learning fosters active participation, intrinsic motivation, and autonomous learning. This approach enables students to interact with content in a multimodal format, take on challenges, and collaborate, thereby enriching their educational experience in virtual environments [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Among the most recent applications of gamification in the classroom are initiatives such as “Bed Race, The End of Life Game,” a board game designed to teach the principles of palliative and end-of-life care [

15], and “The Palliative Care Room,” a gamified social intervention aimed at enhancing learning outcomes [

16].

Despite its potential, the literature on the gamification of palliative care education remains limited. However, studies have reported that gamified interventions can promote empathy, deepen knowledge, enhance communication, and increase student motivation and engagement [

17,

18]. Nonetheless, critics argue that introducing playful elements into sensitive educational contexts may risk trivializing complex topics, potentially undermining the emotional or ethical depth of the learning experience. Additionally, questions concerning the generalizability of gamification across diverse learner groups and educational settings remain. Some studies suggest that its benefits depend largely on participants’ prior experience and the specific design of the intervention [

18,

19,

20].

In light of the limited evidence available regarding gamified educational interventions in palliative care, this study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of a gamified program in enhancing palliative care knowledge among nursing students at a public university. The overarching goal is to contribute to the comprehensive training of future healthcare professionals by strengthening their clinical, ethical, and humanistic competencies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling Method

A quasi-experimental pre–post study design without a control group was conducted within the nursing program at Universidad Técnica del Norte in Ecuador, between October 2024 and February 2025. The study population included students enrolled in the seventh academic level and those undertaking their rotating internship during the May 2024 to April 2025 academic period and the September 2024 to August 2025 academic period.

To determine the sample size, stratified probabilistic sampling was employed, with proportional allocation based on the academic period (stratum) in which students were enrolled. From a target population of 208 students, the sample size was calculated using the Stata statistical software. Given the quasi-experimental design, which aimed to detect a statistically significant difference in mean scores before and after the educational intervention, a two-tailed test was applied, with a 95% confidence level (α = 0.05), 80% statistical power (1–β = 0.80), and a 5% margin of error. Additionally, a 10% replacement rate was considered to account for potential losses or dropouts during the course of the study.

This approach yielded a minimum required sample of 136 students, proportionally distributed across the defined strata. This ensured the adequate representation of the target population and the statistical robustness of the findings.

2.1.1. Blinding

Considering that the study had a quasi-experimental design without a control group or randomization, neither participants nor the research team were blinded to the educational intervention. However, blinding was applied during data analysis to mitigate potential bias.

To minimize bias, participant anonymity was ensured through the use of alphanumeric codes, thereby preventing any association with personal identifiers. Data collection instruments were administered without immediate feedback. Additionally, clear role separation was maintained between those implementing the intervention and those conducting the statistical analysis, with the latter having exclusive access to the anonymized database.

Despite the open-label nature of the study, these methodological safeguards helped reduce the risk of information, observation, and confirmation biases, in alignment with the methodological guidelines of the TREND statement for non-randomized educational trials.

2.2. Study Setting

The study was conducted in the academic and clinical training environments of the Nursing Program at Universidad Técnica del Norte, specifically within secondary-level healthcare institutions located in Ibarra, Otavalo, Lago Agrio, and Tena.

2.3. Design and Development of the Gamified Educational Intervention in Palliative Care

A virtual educational strategy was designed and implemented in the format of a gamified MOOC (Massive Open Online Course), which was delivered through the Moodle platform. The pedagogical approach was grounded in meaningful learning, patient-centered care, and gamification, which were considered to promote active learning aimed at developing professional competencies. The instructional design adhered to the guidelines and recommendations of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), the World Health Organization (WHO) [

21], and Ecuador's National Technical Standard for Palliative Care [

22].

The instructional plan comprised ten thematic modules delivered over five weeks, addressing foundational, ethical, humanistic, and clinical aspects of palliative care. Each module integrated multimedia resources, curated readings, and gamified interactive components such as information prompts, visual cues, progressive challenges, and real-time feedback to encourage active and autonomous student participation. These tools supported the meaningful construction of knowledge and the achievement of defined learning outcomes.

To ensure the quality and relevance of the content, the Delphi technique was employed; this is a structured consensus method that involves successive rounds of expert evaluation. Ten professionals specializing in palliative care, nursing, and health education reviewed the content and training strategy across two rounds, applying criteria related to clarity, coherence, relevance, and applicability. The process led to the refinement of the intervention, as evidenced by Aiken’s content validity coefficient (V > 0.85) and Fleiss’ Kappa inter-rater agreement index (k > 0.80).

Moodle was selected as the learning platform due to its widespread use in health education and its capacity to host and distribute educational content. It served as the central repository for the course materials, which were developed in Word and HTML using Dreamweaver. The platform also hosted evaluation instruments and gamified interactive resources [

15].

Two faculty tutors were assigned to support the intervention group, providing guidance through the platform and its discussion forums. The online course spanned a total of 60 instructional hours, equivalent to 10 academic credits.

Pre- and post-intervention assessments were conducted using the Spanish version of the Palliative Care Quiz for Nursing (PCQN-SV). Additionally, a custom questionnaire was administered to evaluate student satisfaction with the methodology and the usability, accessibility, and functionality of the Moodle platform. A score of ≥13 correct responses (out of 20) was considered an adequate level of palliative care knowledge.

The PCQN-SV demonstrated solid psychometric properties. The content validity index (S-CVI) reached 0.83, indicating strong domain representation. The internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was 0.67, and the Kuder–Richardson 20 (KR-20) reliability coefficient was 0.72; both of these are acceptable as educational assessment tools [

23].

2.4. Variables

2.4.1. The Independent Variable (IV), Was the Gamified Educational Intervention, Which Involved the Use of Instructional Strategies Incorporating Game-Based Elements. This Intervention Aimed to Enhance Nursing Students’ Knowledge of Palliative Care

2.4.2. The Dependent Variable (DV), Was the Level of Knowledge Regarding Palliative Care, Assessed Both Before and After the Intervention. This Allowed for the Evaluation of the Intervention’s Effect on Students’ Knowledge Levels

The demographic variables included age, gender, academic level, and the hospital practice area. Palliative care knowledge was measured using the Spanish version of the Palliative Care Quiz for Nursing (PCQN-SV) [

23,

24], which comprises three dimensions: Philosophy and principles of palliative care (4 items), Pain and symptom management (13 items), and Psychosocial and spiritual principles (3 items).

All items were presented in multiple-choice format with three response options: “true,” “false,” or “don’t know.” For statistical analysis, these responses were recoded using a binary coding scheme.

2.5. Data Collection Procedure

The questionnaire was administered virtually through an online platform, enabling students engaged in clinical practice across different healthcare settings to participate. The estimated time required to complete the instrument ranged from 15 to 20 minutes.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The qualitative variables were summarized using measures such as means and standard deviations (SD). To assess the differences in knowledge scores, a paired t-test was applied when normality assumptions were met, yielding statistically significant results (t = 11.05; p < 0.001). For non-parametric data, the Mann–Whitney U test was used, which confirmed a shift toward higher post-intervention scores (p < 0.001), indicating a significant improvement. The effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d, adjusted with Hedges’ correction. Binary logistic regression was also used to estimate the adjusted odds ratios (ORs), evaluating the contextual impact of the intervention. A 95% confidence level was applied. All categorical variables were coded in the database. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

The unit of analysis was the individual student. However, because the sample included students placed in different hospitals, the hospital variable was incorporated as a stratification factor in the logistic regression models. This allowed the analysis to adjust for potential clustering effects by practice site, thereby improving the precision of effect estimation across institutional contexts.

3. Results

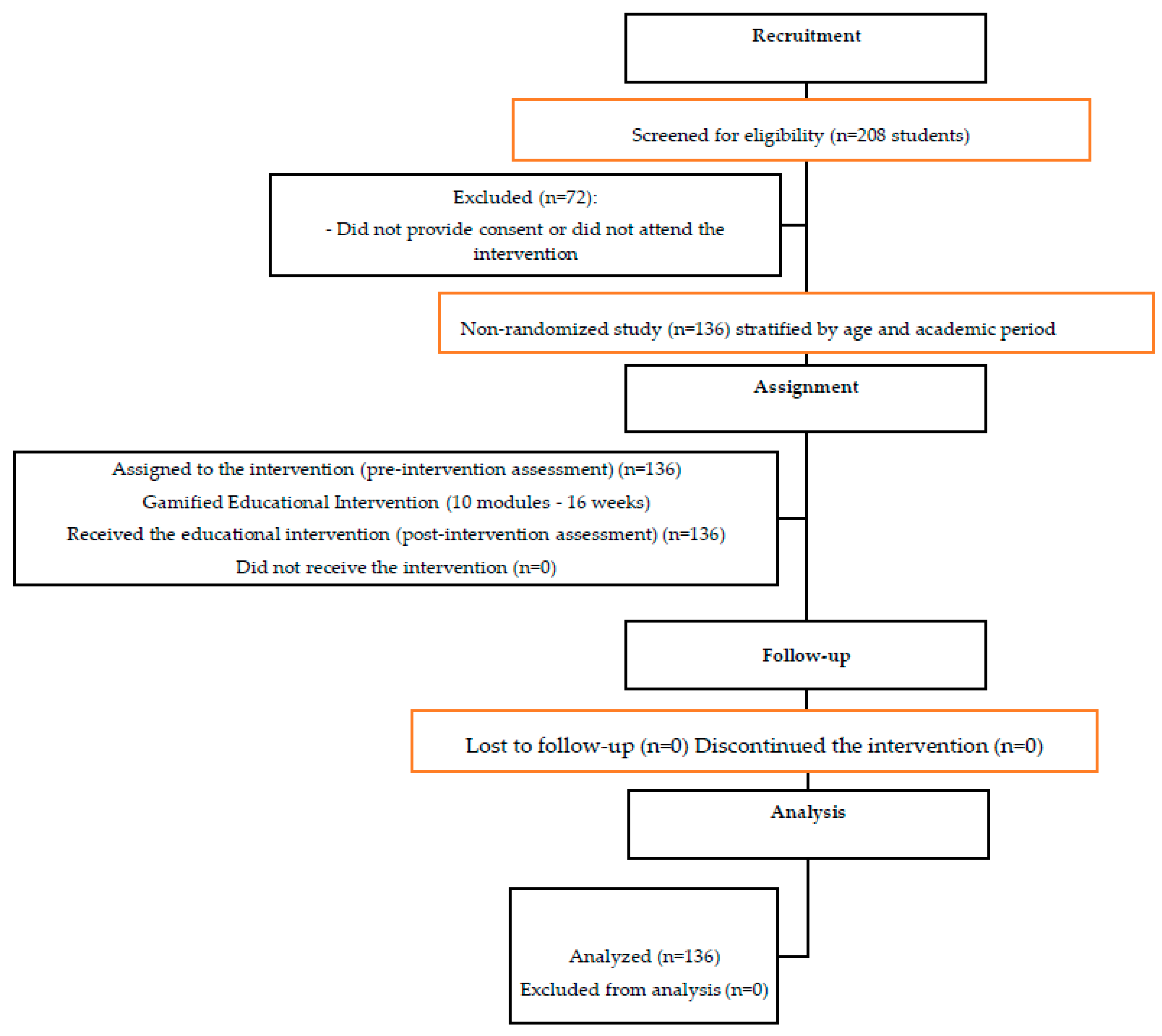

The study was conducted and reported in accordance with the TREND statement for non-randomized intervention studies. Figure 1 presents the participant flow diagram based on the TREND guidelines.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant selection according to the TREND statement.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participant selection according to the TREND statement.

A total of 208 nursing students were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 136 met the inclusion criteria and actively participated in the educational intervention, as illustrated in

Figure 1. It is important to note that although the study was not randomized, a cohort-stratified sampling approach was employed, ensuring adequate representation across the various academic stages included in the study.

All enrolled students completed the intervention, with no losses to follow-up or dropouts reported. As a result, the analysis was conducted on the full planned sample (n = 136), maintaining the intention-to-treat principle outlined in the study protocol and thereby reinforcing the consistency and methodological robustness of the findings.

This methodological approach allows for a cautious and realistic assessment of the intervention's impact, while simultaneously strengthening the study’s internal validity. It aligns with international recommendations for educational research conducted using non-randomized designs. The baseline characteristics of the participants were comparable across strata, as summarized in

Table 1.

3.1. Pre- and Post-Intervention Analysis

A total of 136 nursing students were evaluated (mean age: 22.9 ± 1.89 years; 73.5% female), with these students distributed across two academic periods (53.6% and 46.4%, respectively). Pre- and post-intervention assessments were conducted using the full sample (n = 136) at both time points.

During the pre-intervention phase, the score distribution exhibited mild positive skewness (0.300) and near-normal kurtosis (0.104), indicating the absence of significant bias. The baseline knowledge levels were low in 72.8% of students (n = 99), with a mean score of 11.86 (SD = 2.36), reflecting high variability and heterogeneity in knowledge levels.

Following the intervention, the mean score increased significantly to 15.80 (SD = 1.12), accompanied by a reduction in score dispersion and a relative improvement in 39.2% of students (n = 53). The post-intervention distribution showed moderate negative skewness (–0.508) and slight negative kurtosis (–0.135), indicating a concentration of higher scores and general symmetry without significant bias. The inferential analysis revealed statistically significant differences between pre- and post-intervention scores (t(135) = 11.05, p < 0.001).

In addition to the statistical significance, the effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d for paired samples, yielding a value of d = 1.33. This was based on the difference between the post-intervention mean (M = 15.80) and the pre-intervention mean (M = 11.35), with a pooled standard deviation of approximately 3.35. According to the established benchmarks (d ≥ 0.80), this represents a large effect size, demonstrating the substantial impact of the educational intervention. The paired-sample t-test yielded a t-value of 11.05 with a p-value < 0.001, confirming the statistically significant differences between pre- and post-intervention knowledge scores.

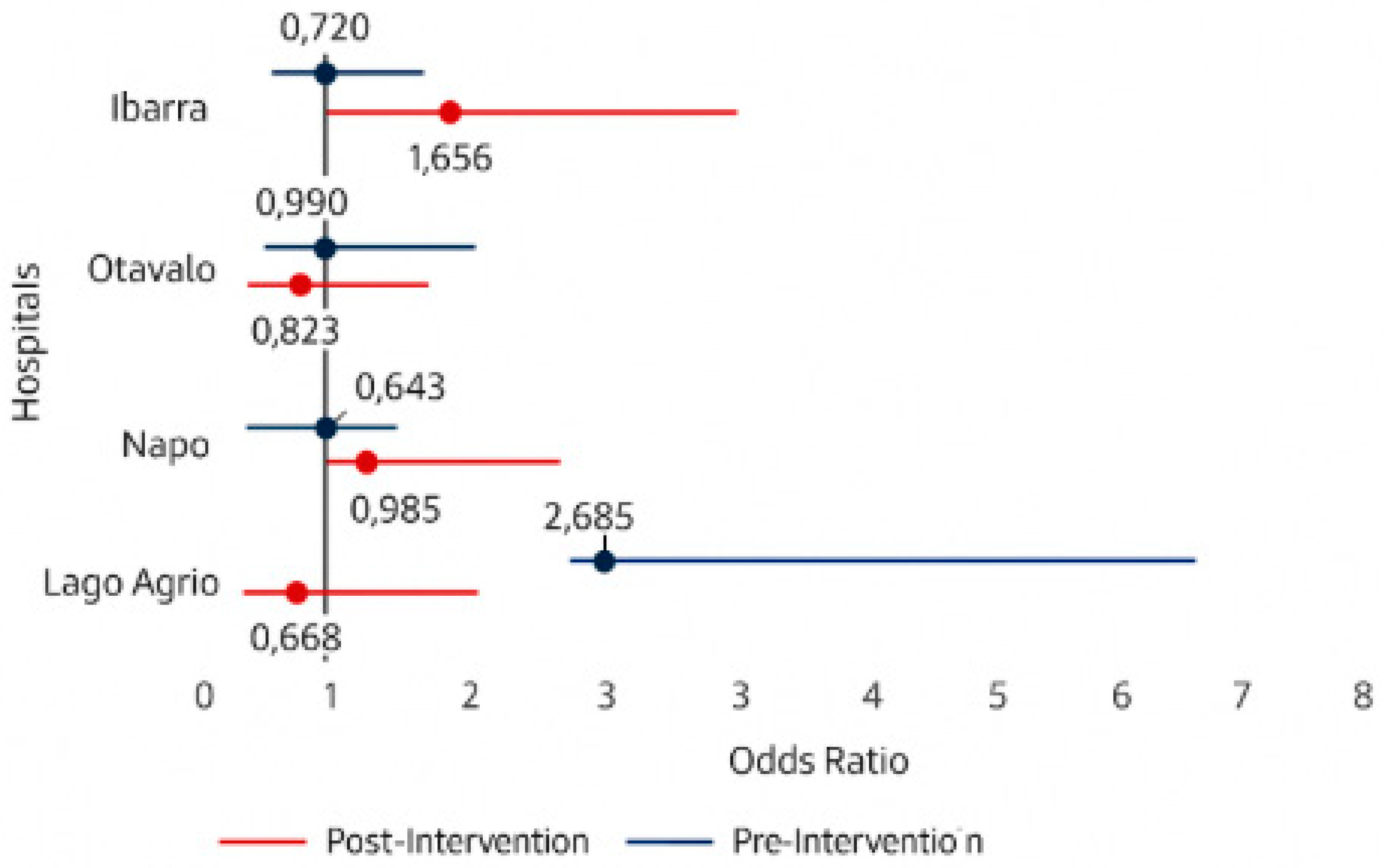

3.2. Adjusted Odds Ratio Analysis for High Palliative Care Scores by Hospital and Intervention Phase.

Figure 1 presents the adjusted odds ratios (ORs) for achieving high scores on the PCQN-SV questionnaire, stratified by the hospital and intervention phase, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals. During the pre-intervention phase, no statistically significant differences were observed among hospitals, indicating comparable baseline knowledge levels across sites. However, in the post-intervention phase, a statistically significant improvement was identified exclusively in the Lago Agrio site (OR = 2.65; 95% CI: 1.04–6.75), suggesting that the intervention had a localized positive effect in this setting. In contrast, the adjusted ORs for the remaining hospitals did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios of high scores on the palliative care questionnaire, by hospital, before and after the intervention.

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios of high scores on the palliative care questionnaire, by hospital, before and after the intervention.

3.3. Comparison of Adjusted Probabilities of High Knowledge After the Intervention, by Hospital.

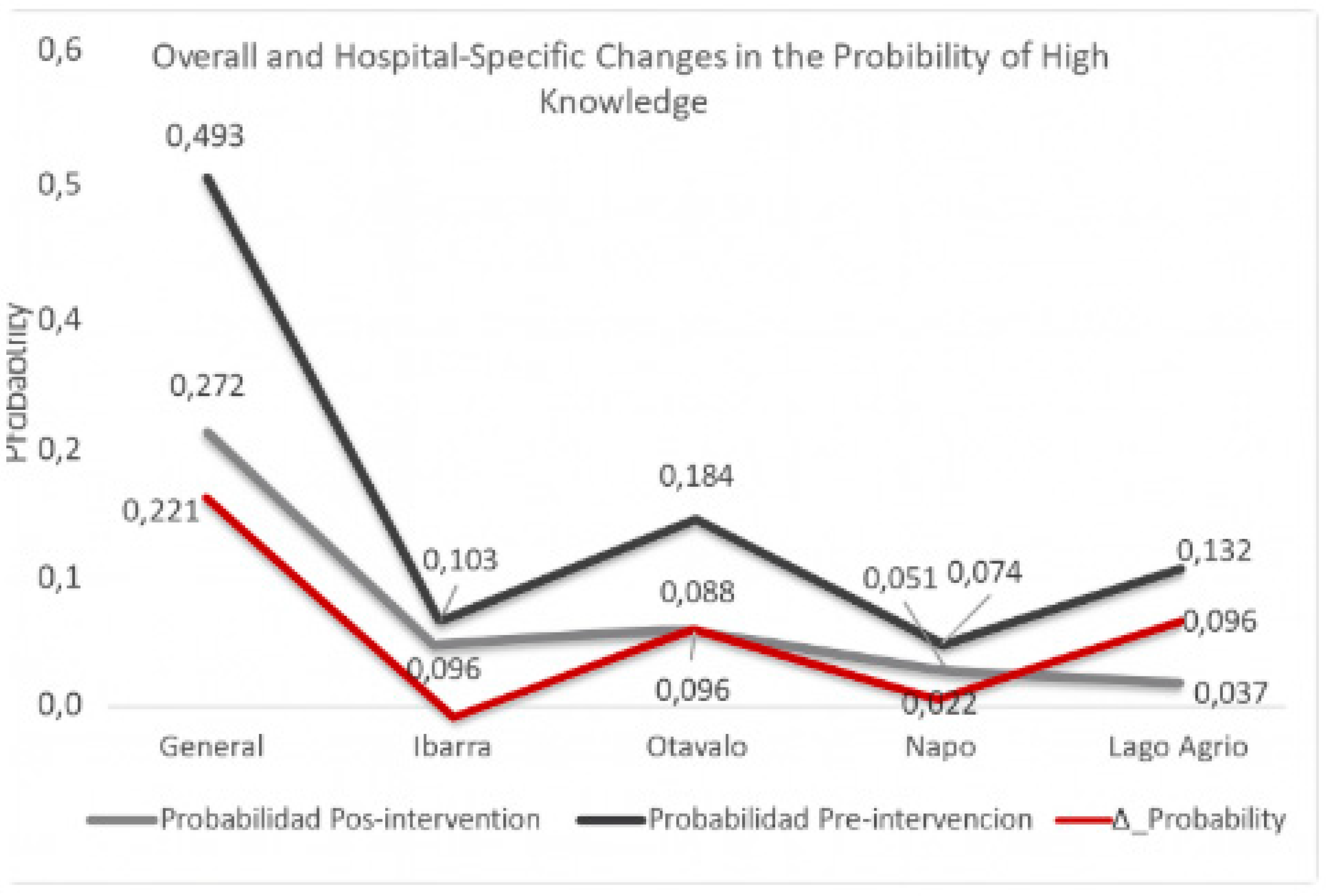

Figure 2 displays the absolute difference in the adjusted probabilities of achieving a high level of knowledge in palliative care, comparing pre- and post-intervention assessments across the hospitals where students completed their clinical rotations. Each probability was estimated using binary logistic regression, and the difference was calculated as the absolute increase between the predicted probabilities before and after the intervention. This approach enabled the identification of the proportion of students who achieved high knowledge levels as a direct result of the intervention, and allowed for a clearer visualization of inter-hospital differences, highlighting the overall impact of the implemented program.

An absolute increase in the probability of attaining high scores was observed in all hospitals following the intervention, although the magnitude of change varied by site. Lago Agrio exhibited the greatest increase, which aligns with the previously reported OR findings. This analysis underscores the tangible effect of the intervention in terms of the proportion of students who benefited.

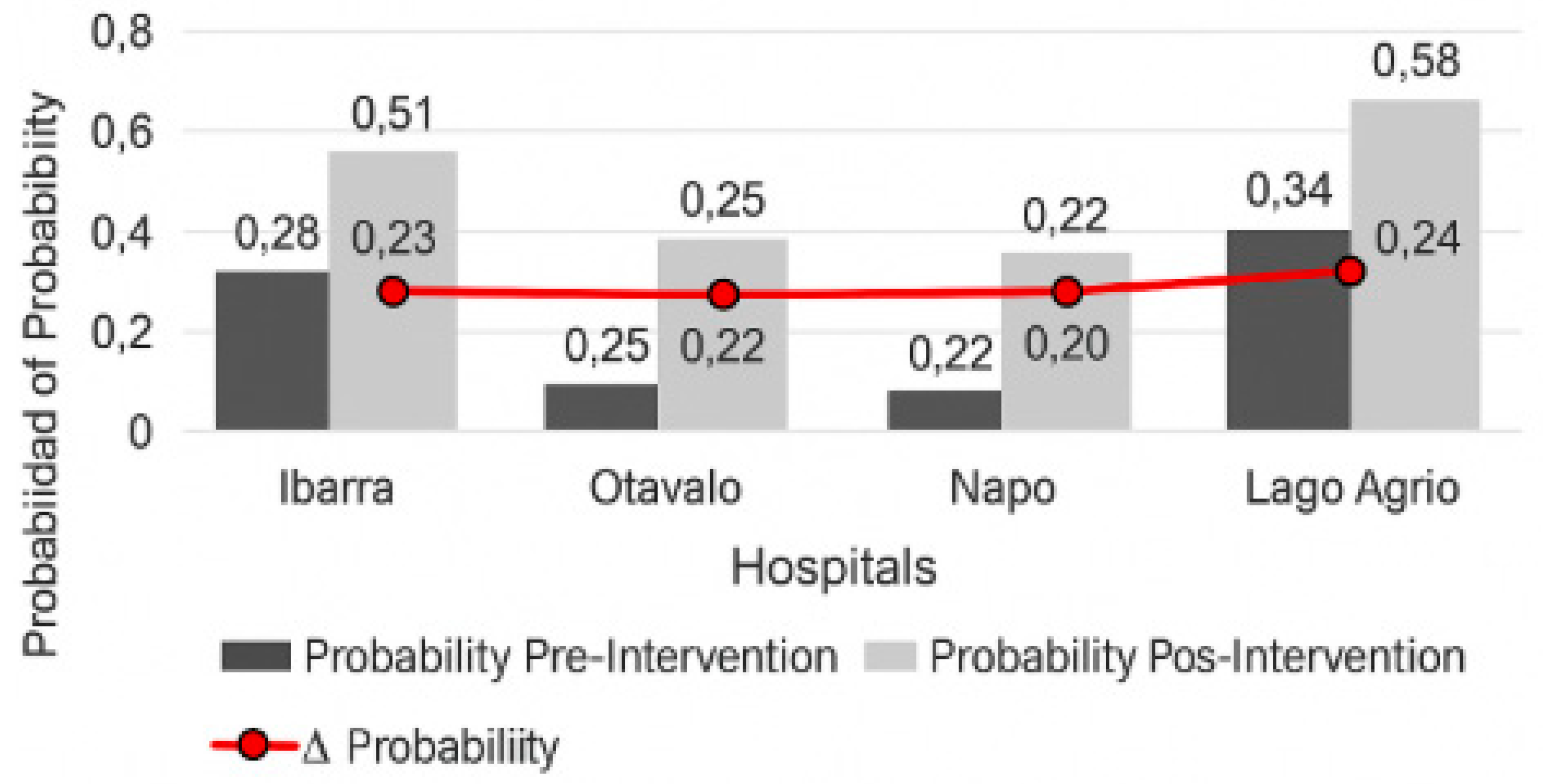

Figure 3 displays the adjusted probabilities of achieving a high level of knowledge on the PCQN-SV questionnaire for each hospital, before and after the gamified educational intervention. Probabilities were estimated using binary logistic regression, with hospital included as a stratification variable. This approach allowed the model to generate adjusted values that reflect inter-institutional differences and enabled the identification of hospitals where the greatest changes occurred across the two evaluation points.

An overall increase in the adjusted probabilities of high scores was observed in all hospitals following the intervention. However, the magnitude of these improvements varied: the most pronounced changes were recorded in Lago Agrio and Otavalo, whereas the increases in Ibarra and Napo were more modest. These findings illustrate the differentiated benefits of the intervention across healthcare training sites.

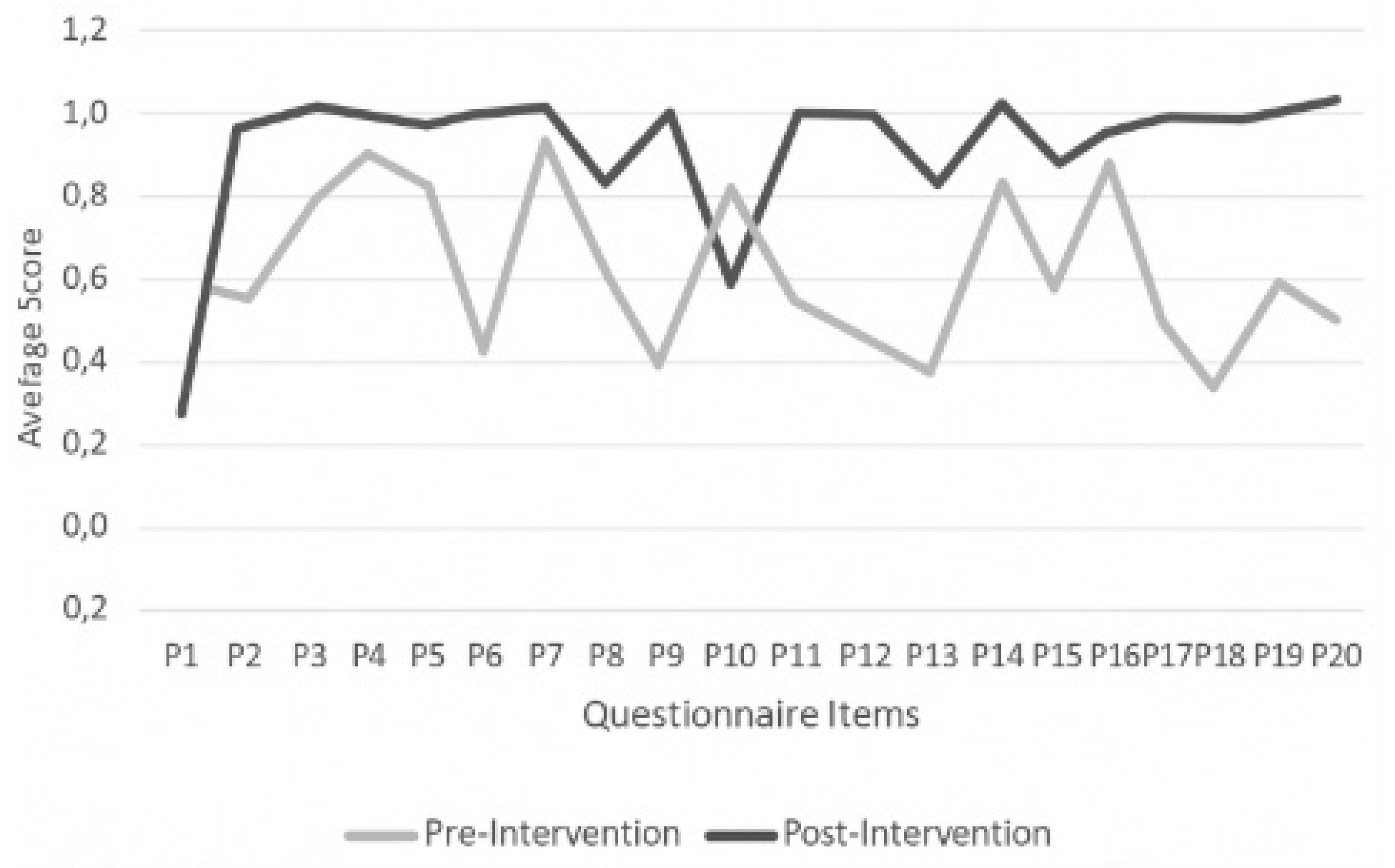

Figure 4 presents the mean scores obtained by students, stratified by individual questionnaire items and comparing pre- and post-intervention assessments. This item-level analysis revealed an overall improvement in the average scores following the intervention, with variations observed depending on the specific content addressed by each question and its corresponding dimension within the questionnaire.

These findings demonstrate that the intervention had a targeted impact across the thematic areas covered, particularly in those components that were reinforced through the training strategy.

4. Discussion

The results indicate a reduction in both the mean and standard deviation from pre- to post-intervention, suggesting a clear change in palliative care (PC) knowledge levels following the intervention. This pattern aligns with previous research reporting that structured educational interventions in PC are highly effective at improving competency, particularly when students begin with low baseline knowledge levels [

25,

26,

27]. However, the literature also highlights that knowledge levels are associated with age and experience, while attitude scores are more closely tied to formal training and clinical exposure to end-of-life care [

19]. Thus, continuous and context-specific interventions, supported by tailored implementation and monitoring strategies, are essential [

27,

28,

29].

The decrease in the standard deviation from 2.36 (pre-intervention) to 1.12 (post-intervention) indicates less score dispersion, suggesting that the students’ responses were more homogenous. This is consistent with the literature on dispersion metrics, which posits that a lower standard deviation reflects a higher concentration of scores around the mean [

30,

31].

The reading strategy evaluation showed a significant increase in scores post-intervention (t-comp = 10.66 > t-critical = 4.30), confirming the program's effectiveness. This mirrors findings from other studies where well-designed strategies enhance both knowledge and confidence in palliative care, including communication and symptom management [

19].

Educational interventions in palliative care consistently demonstrate improvements in students’ knowledge, attitudes, and competencies. Variations among studies are primarily due to differences in target populations [

32], intervention formats [

19,

27] and the specific outcome domains assessed [

19]. Prior to the intervention, no statistically significant differences were observed in the odds ratios (ORs) of high knowledge scores across hospitals, suggesting baseline homogeneity.

This finding aligns with other studies in similar contexts, where both nursing and medical students exhibited uniformly low PC knowledge before training, regardless of the institution or region [

32]. According to Ausubel’s theory of meaningful learning, the absence of prior knowledge hinders the integration of new concepts. This underscores the need for structured, context-based educational interventions centered on the learner.

While the results were positive, generalization should be approached with caution, as the intervention was conducted in a single public university in Ecuador. Factors such as access to technology, faculty preparedness, and academic workload may influence the program’s scalability in other settings.

Unlike studies reporting uniform knowledge baselines, our results showed that students had significantly low and heterogeneous levels prior to the intervention. This could be attributed to the use of gamification [

33,

34,

35] as a pedagogical tool to enhance long-term knowledge retention and promote the development of the soft skills required to care for vulnerable patients.

Compared with similar international interventions, the odds ratio observed in Lago Agrio (OR = 2.65) is consistent with the effects reported globally. Although most studies do not explicitly report ORs, the effect sizes and increases in knowledge are often comparable or greater, supporting the intervention’s effectiveness [

27,

33].

Both quantitative (means, standard deviation, t-tests, ORs) and qualitative (literature review, pedagogical interpretation) data confirm that the educational intervention had a positive effect on PC knowledge. Nonetheless, the literature, suggests that the impact of such interventions is not uniform across all measured dimensions. This implies that the intervention exerted a targeted effect, which should inform future strategies to enhance learning in underdeveloped areas.

This study presents certain limitations. The short-term evaluation limits generalizability and prevents an assessment of knowledge retention over time. Moreover, potential uncontrolled external variables may have influenced the outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The gamified educational intervention had a significant impact on nursing students’ knowledge of palliative care, evidenced by a statistically significant increase in post-intervention scores (p < 0.001) and a large effect size (Cohen’s d = 1.33), confirming its pedagogical effectiveness. The proportion of students with high knowledge levels increased from 27.2% to 97.79%; this was accompanied by a reduction in the dispersion of scores and more homogenous responses. The hospital-level analysis revealed contextual differences, with Lago Agrio showing the greatest impact. These findings support the integration of active learning strategies such as gamification into palliative care education, advocating for their curricular inclusion and ongoing evaluation.

Author Contributions

J.V.-A.: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing; data analysis and interpretation; K.J.-J.: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing; M.C.-G.: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing; J.L.A.-G.: Data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software; supervision; validation; visualization; writing—original draft; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and approved the final published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by internal funds from Universidad Técnica del Norte.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with bioethical principles for research and the Ecuadorian Organic Law on Personal Data Protection (Official Register Supplement No. 459, May 26, 2021) [

36]. All participants were ensured anonymity and confidentiality of their information. Ethical approval was obtained from the UPEC Ethics Committee [CP-0000001360-CEIHS], approval date: December 10, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individuals involved in the study. Prior to participation, the research team explained the study’s objectives and significance, and each participant provided informed consent. Upon agreement, each student received a personalized access link to the online questionnaire via email, ensuring the confidentiality of responses.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included within the article. Further information can be requested from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the authorities of the Faculty of Health Sciences at Universidad Técnica del Norte. We would like to thank the seventh-semester students and those in clinical internship from the Nursing Program who are currently serving in healthcare facilities located in Zones 1 and 2 of Ecuador.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| PC |

Palliative Care |

| MSP |

Ministry of Public Health |

| UPEC |

Universidad Politécnica Estatal del Carchi |

| PCQN |

Palliative Care Quiz for Nursing |

| CEISH |

Human Research Ethics Committee |

| SIIU |

Integrated University Information System |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| PAHO |

Pan American Health Organization |

| UTN |

Universidad Técnica del Norte. |

References

- World Health Organization, “Palliative care for noncommunicable diseases,” 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/publications-detail/ncd-ccs-2019.

- H. R. Agustina et al., “A Scoping Review of Palliative Care Education for Preregistration Student Nurses in the Asia Pacific Region,” 2025, Dove Medical Press Ltd. [CrossRef]

- R. Yash Pal, M. T. Chua, L. Guo, R. Kumar, L. Shi, and W. Sen Kuan, “The Impact of Palliative and End-of-Life Care Educational Intervention in Emergency Departments in Singapore: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis,” Medicina (Lithuania), vol. 61, no. 2, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Chover-Sierra and A. Martínez-Sabater, “Analysis of Spanish nursing students’ knowledge in palliative care. An online survey in five colleges,” Nurse Educ Pract, vol. 49, p. 102903, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Durojaiye, R. Ryan, and O. Doody, “Student nurse education and preparation for palliative care: A scoping review,” PLoS One, vol. 18, no. 7 July, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ke Ziwei, Chen Mengjiao, Zhang Yongjie, Zhang Mengqi, and Yang Yeqin, “Optimizing palliative care education through undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions: Application of importance-performance analysis and Borich needs assessment model,” Nurse Educ Today, vol. 122, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Q. Yoong et al., “The impact of a student death doula service-learning experience in palliative care settings on nursing students: A pilot mixed-methods study.,” Death Stud, pp. 1–13, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. C. Gillan and S. Johnston, “Nursing students satisfaction and self-confidence with standardized patient palliative care simulation focusing on difficult conversations,” Palliat Support Care, vol. 22, no. 5, pp. 1237–1244, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Dudley, L. Rauch, T. Adelman, and D. Canham, “Addressing cultural competency and primary palliative care needs in community health nursing education,” Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing, vol. 24, no. 5, pp. 265–270, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Natuhwera, E. Namisango, and P. Ellis, “Knowledge, Self-Efficacy, and Correlates in Palliative and End-of-Life Care: Quantitative Insights from Final-Year Nursing and Medical Students in a Mixed-Methods Study,” Palliat Care Soc Pract, vol. 19, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Khaldi, R. Bouzidi, and F. Nader, “Gamification of e-learning in higher education: a systematic literature review,” Dec. 01, 2023, Springer. [CrossRef]

- M. Khalil, J. Wong, B. De Koning, M. Ebner, and F. Paas, “Gamification in MOOCs: A review of the state of the art,” in IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference, EDUCON, IEEE Computer Society, May 2018, pp. 1629–1638. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Major and M. Mira da Silva, “Gamification in MOOCs: A systematic literature review,” 2023, Taylor and Francis Ltd. [CrossRef]

- L. Li, F. Wang, Q. Liang, L. Lin, and X. Shui, “Nurses knowledge of palliative care: systematic review and meta-analysis,” BMJ Support Palliat Care, vol. 14, no. e2, pp. e1585–e1593, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Harris and C. Atkinson, “Palliative medicine education—Bed Race, The End of Life Board Game in undergraduates,” BMJ Support Palliat Care, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 411–417, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Reigada et al., “Palliative care stay room – designing, testing and evaluating a gamified social intervention to enhance palliative care awareness,” BMC Palliat Care, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Schenell, J. Österlind, M. Browall, C. Melin-Johansson, C. L. Hagelin, and E. Hjorth, “Teaching to prepare undergraduate nursing students for palliative care: nurse educators’ perspectives,” BMC Nurs, vol. 22, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. E. J. van Gaalen, J. Brouwer, J. Schönrock-Adema, T. Bouwkamp-Timmer, A. D. C. Jaarsma, and J. R. Georgiadis, “Gamification of health professions education: a systematic review,” Advances in Health Sciences Education, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 683–711, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Lyttle et al., “An Educational Intervention to Enhance Palliative Care Training at HBCUs,” J Pain Symptom Manage, vol. 65, no. 5, pp. 418–427, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. W. S. Cheng, T. Davenport, D. Johnson, K. Vella, and I. B. Hickie, “Gamification in Apps and Technologies for Improving Mental Health and Well-Being: Systematic Review,” JMIR Ment Health, vol. 6, no. 6, p. e13717, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Vereecke et al., “Experiential workshop on innovative teaching methods to improve palliative care education.,” Int J Integr Care, vol. 23, no. S1, p. 309, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Salud Pública del Ecuador, “Norma Técnica de Cuidados Paliativos,” 2015.

- Chover-Sierra, A. Martínez-Sabater, and Y. R. Lapeña-Moñux, “An instrument to measure nurses’ knowledge in palliative care: Validation of the Spanish version of Palliative Care Quiz for Nurses,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 5, p. e0177000, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Ross, B. McDonald, and J. McGuinness, “The palliative care quiz for nursing (PCQN): The development of an instrument to measure nurses’ knowledge of palliative care,” J Adv Nurs, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 126–137, Jan. 1996. [CrossRef]

- W. Etafa et al., “Nurses’ knowledge about palliative care and attitude towards end- of-life care in public hospitals in Wollega zones: A multicenter cross-sectional study,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 10 October, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hao, L. Zhan, M. Huang, X. Cui, Y. Zhou, and E. Xu, “Nurses’ knowledge and attitudes towards palliative care and death: a learning intervention,” BMC Palliat Care, vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Menekli, R. Doğan, Ç. Erce, and İ. Toygar, “Effect of educational intervention on nurses knowledge about palliative care: Quasi-experimental study,” Nurse Educ Pract, vol. 51, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Ghizzardi et al., “Education Programs for Informal Caregivers of Noncancer Patients in Home-Based Palliative Care: A Scoping Review,” J Palliat Med, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Dobbs et al., “Feasibility of the Palliative Care Education in Assisted Living Intervention for Dementia Care Providers: A Cluster Randomized Trial,” Gerontologist, vol. 64, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Dobbs et al., “Feasibility of the Palliative Care Education in Assisted Living Intervention for Dementia Care Providers: A Cluster Randomized Trial,” Gerontologist, vol. 64, no. 1, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. V Mardia, “Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications,” Biometrika, vol. 57, no. 3, p. 519, 1970, [Online]. Available: http://biomet.oxfordjournals.org/.

- Ghizzardi et al., “Education Programs for Informal Caregivers of Noncancer Patients in Home-Based Palliative Care: A Scoping Review,” J Palliat Med, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Koivisto and J. Hamari, “El auge de los sistemas de información motivacionales: una revisión de la investigación de gamificación.,” Revista Internacional de Gestión de Información, vol. 45, no. December 2018, pp. 191–210, 2019. Accessed: Jul. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/ininma/v45y2019icp191-210.html.

- S. Rafiee, I. Azizi-Fini, Z. S. Banihashemi, and S. Yadollahi, “Knowledge and attitude towards palliative care and associated factors among nurse: a cross-sectional descriptive study,” BMC Nurs, vol. 23, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Gentry et al., “Serious gaming and gamification education in health professions: systematic review,” Mar. 01, 2019, JMIR Publications Inc. [CrossRef]

- Asamblea Nacional del Ecuador, “Ley Orgánica de Protección de datos personales,” May 2021.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).