Submitted:

28 August 2025

Posted:

30 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

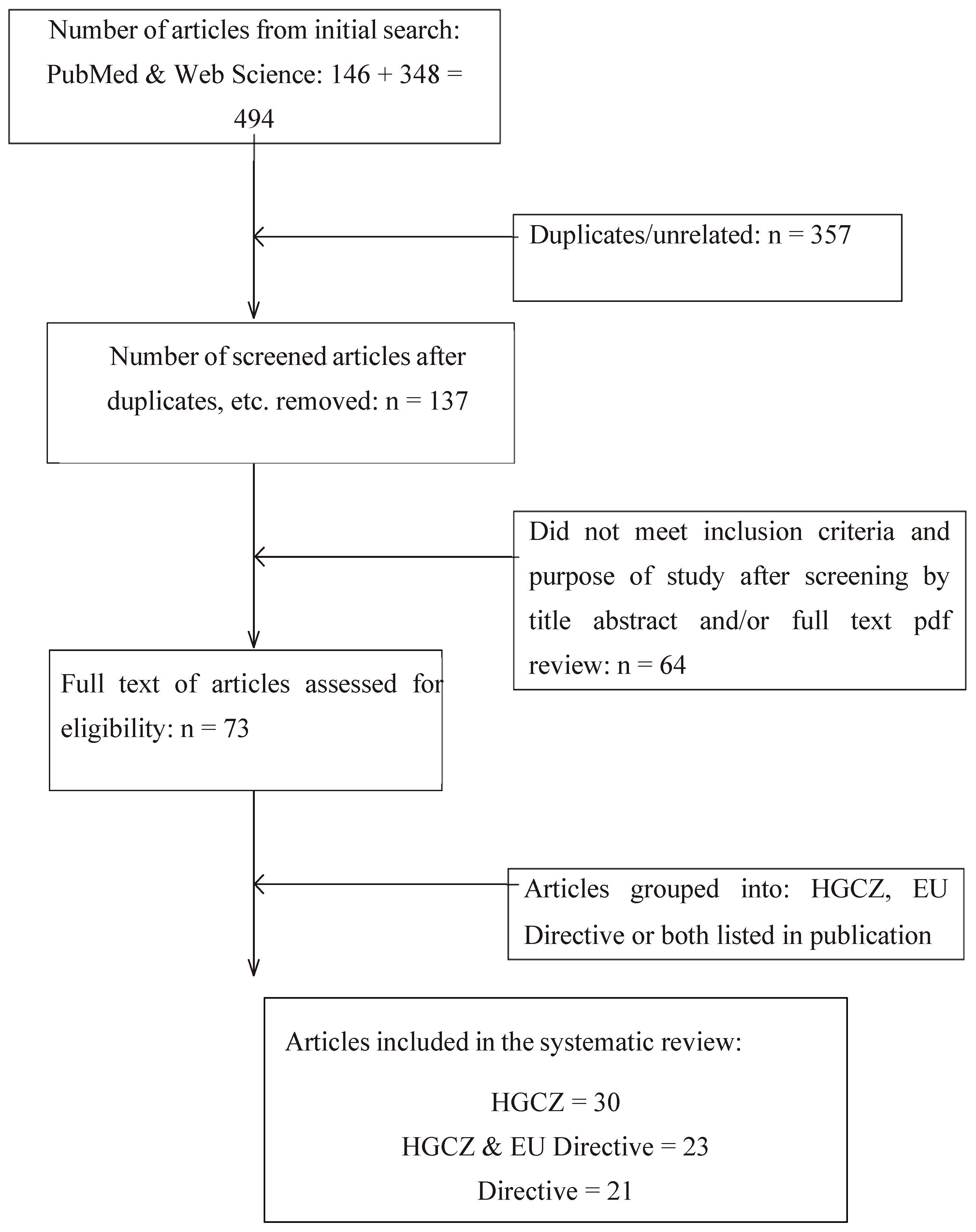

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

References

- Armstrong, T.J., et al., Scientific basis of ISO standards on biomechanical risk factors. Scand J Work Environ Health, 2018. 44(3): p. 323–329. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, T.J., et al., Authors’ response: Letter to the Editor concerning OCRA as preferred method in ISO standards on biomechanical risk factors. Scand J Work Environ Health, 2018. 44(4): p. 439–440. [CrossRef]

- IS0, I.O.f.S., ISO 2631-1:1997 Mechanical vibration and shock — Evaluation of human exposure to whole-body vibration, in Part 1: General requirements. 1997, IS0 International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland.

- 2002/44, E.D., Directive 2002/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 June 2002 on the minimum health and safety requirements regarding the exposure of workers to the risks arising from physical agents (vibration). 2002, European Commision: Official Journal of the European Communities.

- Nelson, C.M. and P.F. Brereton, The European vibration directive. Ind Health, 2005. 43(3): p. 472–9.

- Bovenzi, M., Health risks from occupational exposures to mechanical vibration. Med Lav, 2006. 97(3): p. 535–41.

- Donati, P.S., M; Szopa, J.; Starck, J..; Iglesias, E.G.; Senovilla, L.P.; Fischer, S.; Flaspoeler, E.; Reinert, D.; de Beeck, R.O.; , Workplace exposure to vibration in Europe: an expert review. 2008, European Agency for Safety and Health at Work: Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Peters, M.D., et al., Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc, 2015. 13(3): p. 141–6.

- Griffin, M.J., Minimum health and safety requirements for workers exposed to hand-transmitted vibration and whole-body vibration in the European Union; a review. Occup Environ Med, 2004. 61(5): p. 387–97. [CrossRef]

- Hulshof, C.T., et al., Evaluation of an occupational health intervention programme on whole-body vibration in forklift truck drivers: a controlled trial. Occup Environ Med, 2006. 63(7): p. 461–8.

- Ross, P.T. and N.L. Bibler Zaidi, Limited by our limitations. Perspect Med Educ, 2019. 8(4): p. 261–264.

- Sumpter, J.P., et al., A ‘Limitations’ section should be mandatory in all scientific papers. Science of The Total Environment, 2023. 857: p. 159395.

- Griffin, M.J.P., P.M.; Fischer, S.; Kaulbars, U.; Donati, P.M.; Bereton, P.F.;, Guide to good practice on Whole-Body Vibration - Non-binding guide to good practice with a view to implementation of Directive 2002/44/EC on the minimum health and safety requirements regarding the exposure of workers to the risks arising from physical agents (vibrations). (EU Good Practice Guide WBV), T.W.P.V.m.b.t.A.C.o.S.a.H.a.W.i.c.w.t.E. Commission., Editor. 2006. p. 65.

- Dong, R.G., D.E. Welcome, and T.W. McDowell, Some important oversights in the assessment of whole-body vibration exposure based on ISO-2631-1. Appl Ergon, 2012. 43(1): p. 268–9.

- Maeda, S., Necessary research for standardization of subjective scaling of whole-body vibration. Ind Health, 2005. 43(3): p. 390–401. [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, N.J., G.S. Newell, and L. Notini, Earth moving machine whole-body vibration and the contribution of Sub-1Hz components to ISO 2631-1 metrics. Ind Health, 2009. 47(4): p. 402–10.

- Waters, T., et al., A new framework for evaluating potential risk of back disorders due to whole body vibration and repeated mechanical shock. Ergonomics, 2007. 50(3): p. 379–95.

- Bainbridge, A., et al., Whole body vibrations and lower back pain: a systematic review of the current literature. BMJ Mil Health, 2025.

- Tricco, A.C., et al., PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med, 2018. 169(7): p. 467–473.

- Giacomin, J., Absorbed power of small children. Clin Biomech (Bristol), 2005. 20(4): p. 372–80.

- Cuschieri, S., The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth, 2019. 13(Suppl 1): p. S31–s34.

- Ghaferi, A.A., T.A. Schwartz, and T.M. Pawlik, STROBE Reporting Guidelines for Observational Studies. JAMA Surg, 2021. 156(6): p. 577–578. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., et al., Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med, 2010. 7(2): p. e1000217.

- Atal, M.K., et al., Occupational exposure of dumper operators to whole-body vibration in opencast coal mines: an approach for risk assessment using a Bayesian network. Int J Occup Saf Ergon, 2022. 28(2): p. 758–765.

- Burgess-Limerick, R. and D. Lynas, Long duration measurements of whole-body vibration exposures associated with surface coal mining equipment compared to previous short-duration measurements. J Occup Environ Hyg, 2016. 13(5): p. 339–45. [CrossRef]

- Candiotti, J.L., et al., Analysis of Whole-Body Vibration Using Electric Powered Wheelchairs on Surface Transitions. Vibration, 2022. 5(1): p. 98–109.

- Chaudhary, D.K., et al., Whole-body vibration exposure of heavy earthmoving machinery operators in surface coal mines: a comparative assessment of transport and non-transport earthmoving equipment operators. Int J Occup Saf Ergon, 2022. 28(1): p. 174–183.

- Chen, J.C., et al., Predictors of whole-body vibration levels among urban taxi drivers. Ergonomics, 2003. 46(11): p. 1075–90.

- Conrad, L.F., et al., Selecting seats for steel industry mobile machines based on seat effective amplitude transmissibility and comfort. Work, 2014. 47(1): p. 123–36.

- Dhatrak, S.V., I.A. Shah, and S.S. Prajapati, Determinants of discomfort from combined exposure to noise and vibration in dumper operators of mining industry in India. J Occup Environ Hyg, 2024. 21(6): p. 389–396.

- Eger, T., et al., Vibration induced white-feet: overview and field study of vibration exposure and reported symptoms in workers. Work, 2014. 47(1): p. 101–10.

- Garcia-Mendez, Y., et al., Health risks of vibration exposure to wheelchair users in the community. J Spinal Cord Med, 2013. 36(4): p. 365–75.

- Grenier, S.G., T.R. Eger, and J.P. Dickey, Predicting discomfort scores reported by LHD operators using whole-body vibration exposure values and musculoskeletal pain scores. Work, 2010. 35(1): p. 49–62.

- Hischke, M. and R.F. Reiser, 2nd, Effect of Rear Wheel Suspension on Tilt-in-Space Wheelchair Shock and Vibration Attenuation. PM R, 2018. 10(10): p. 1040–1050.

- Howard, B., R. Sesek, and D. Bloswick, Typical whole body vibration exposure magnitudes encountered in the open pit mining industry. Work, 2009. 34(3): p. 297–303.

- Jack, R.J., et al., Six-degree-of-freedom whole-body vibration exposure levels during routine skidder operations. Ergonomics, 2010. 53(5): p. 696–715. [CrossRef]

- Lan, F.Y., et al., An investigation of a cluster of cervical herniated discs among container truck drivers with occupational exposure to whole-body vibration. J Occup Health, 2016. 58(1): p. 118–27.

- Lee, C.D., et al., Usability and Vibration Analysis of a Low-Profile Automatic Powered Wheelchair to Motor Vehicle Docking System. Vibration, 2023. 6(1): p. 255–268.

- Lynas, D. and R. Burgess-Limerick, Whole-Body Vibration Associated with Dozer Operation at an Australian Surface Coal Mine. Ann Work Expo Health, 2019. 63(8): p. 881–889.

- Lynas, D. and R. Burgess-Limerick, Whole-body vibration associated with underground coal mining equipment in Australia. Appl Ergon, 2020. 89: p. 103162.

- Marin, L.S., et al., Assessment of Whole-Body Vibration Exposure in Mining Earth-moving Equipment and Other Vehicles Used in Surface Mining. Ann Work Expo Health, 2017. 61(6): p. 669–680. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, C.G. and J. Nadal, Transmissibility of helicopter vibration in the spines of pilots in flight. Aviat Space Environ Med, 2005. 76(6): p. 576–80.

- Paddan, G.S. and M.J. Griffin, EVALUATION OF WHOLE-BODY VIBRATION IN VEHICLES. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 2002. 253(1): p. 195–213.

- Park, M.S., et al., Health risk evaluation of whole-body vibration by ISO 2631-5 and ISO 2631-1 for operators of agricultural tractors and recreational vehicles. Ind Health, 2013. 51(3): p. 364–70. [CrossRef]

- Pollard, J., et al., The effect of vibration exposure during haul truck operation on grip strength, touch sensation, and balance. Int J Ind Ergon, 2017. 57: p. 23–31.

- Prajapati, S.S., et al., Whole-body Vibration Exposure Experienced by Dumper Operators in Opencast Mining According to ISO 2631-1:1997 and ISO 2631-5:2004: A Case Study. Indian J Occup Environ Med, 2020. 24(2): p. 114–118.

- Sharma, A. and B.B. Mandal, A Critical Assessment of Boundary Limits of Health Risks Associated with WBV Exposure Based on Field Studies on LHD Vehicles in Indian Underground Coal Mines. Indian J Occup Environ Med, 2024. 28(3): p. 198–206. [CrossRef]

- Smets, M.P., T.R. Eger, and S.G. Grenier, Whole-body vibration experienced by haulage truck operators in surface mining operations: a comparison of various analysis methods utilized in the prediction of health risks. Appl Ergon, 2010. 41(6): p. 763–70.

- Smith, S.D., Seat vibration in military propeller aircraft: characterization, exposure assessment, and mitigation. Aviat Space Environ Med, 2006. 77(1): p. 32–40.

- Upadhyay, R., et al., Role of whole-body vibration exposure and posture of dumper operators in musculoskeletal disorders: a case study in metalliferous mines. Int J Occup Saf Ergon, 2022. 28(3): p. 1711–1721. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R., et al., Association between Whole-Body Vibration exposure and musculoskeletal disorders among dumper operators: A case-control study in Indian iron ore mines. Work, 2022. 71(1): p. 235–247.

- Zarei, S., et al., Assessment of semen quality of taxi drivers exposed to whole body vibration. J Occup Med Toxicol, 2022. 17(1): p. 16.

- Blaxter, L., et al., Neonatal head and torso vibration exposure during inter-hospital transfer. Proc Inst Mech Eng H, 2017. 231(2): p. 99–113.

- Blood, R.P., P.W. Rynell, and P.W. Johnson, Whole-body vibration in heavy equipment operators of a front-end loader: role of task exposure and tire configuration with and without traction chains. J Safety Res, 2012. 43(5-6): p. 357–64.

- Blood, R.P., et al., Whole-body Vibration Exposure Intervention among Professional Bus and Truck Drivers: A Laboratory Evaluation of Seat-suspension Designs. J Occup Environ Hyg, 2015. 12(6): p. 351–62.

- Bovenzi, M., et al., A cohort study of sciatic pain and measures of internal spinal load in professional drivers. Ergonomics, 2015. 58(7): p. 1088–102.

- Bovenzi, M., et al., Relationships of low back outcomes to internal spinal load: a prospective cohort study of professional drivers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health, 2015. 88(4): p. 487–99.

- Calvo, A., et al., Vibration and Noise Transmitted by Agricultural Backpack Powered Machines Critically Examined Using the Current Standards. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019. 16(12).

- Coggins, M.A., et al., Evaluation of hand-arm and whole-body vibrations in construction and property management. Ann Occup Hyg, 2010. 54(8): p. 904–14.

- Ehman, E.C., et al., Vibration safety limits for magnetic resonance elastography. Phys Med Biol, 2008. 53(4): p. 925–35.

- Hanumegowda, P.K. and S. Gnanasekaran, Risk factors and prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in metropolitan bus drivers: An assessment of whole body and hand-arm transmitted vibration. Work, 2022. 71(4): p. 951–973.

- Jonsson, P.M., et al., Comparison of whole-body vibration exposures in buses: effects and interactions of bus and seat design. Ergonomics, 2015. 58(7): p. 1133–42.

- McBride, D., et al., Low back and neck pain in locomotive engineers exposed to whole-body vibration. Arch Environ Occup Health, 2014. 69(4): p. 207–13. [CrossRef]

- Milosavljevic, S., et al., Exposure to whole-body vibration and mechanical shock: a field study of quad bike use in agriculture. Ann Occup Hyg, 2011. 55(3): p. 286–95.

- Noorloos, D., et al., Does body mass index increase the risk of low back pain in a population exposed to whole body vibration? Appl Ergon, 2008. 39(6): p. 779–85. [CrossRef]

- Okunribido, O.O., et al., City bus driving and low back pain: a study of the exposures to posture demands, manual materials handling and whole-body vibration. Appl Ergon, 2007. 38(1): p. 29–38.

- Picoral Filho, J.G., et al., Case study on vibration health risk and comfort levels in loading crane trucks. Int J Health Plann Manage, 2019. 34(4): p. e1448–e1463.

- Rehn, B., et al., Neck pain combined with arm pain among professional drivers of forest machines and the association with whole-body vibration exposure. Ergonomics, 2009. 52(10): p. 1240–7. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Perez, J.F., et al., Characterization of workers or population percentage affected by low-back pain (LPB), sciatica and herniated disc due to whole-body vibrations (WBV). Heliyon, 2024. 10(11): p. e31768.

- Supej, M., J. Ogrin, and H.C. Holmberg, Whole-Body Vibrations Associated With Alpine Skiing: A Risk Factor for Low Back Pain? Front Physiol, 2018. 9: p. 204.

- Tarabini, M., B. Saggin, and D. Scaccabarozzi, Whole-body vibration exposure in sport: four relevant cases. Ergonomics, 2015. 58(7): p. 1143–50.

- Thrailkill, E.A., B.R. Lowndes, and M.S. Hallbeck, Vibration analysis of the sulky accessory for a commercial walk-behind lawn mower to determine operator comfort and health. Ergonomics, 2013. 56(1): p. 115–25. [CrossRef]

- Vallone, M., et al., Risk exposure to vibration and noise in the use of agricultural track-laying tractors. Ann Agric Environ Med, 2016. 23(4): p. 591–597.

- Birlik, G., Occupational exposure to whole body vibration-train drivers. Ind Health, 2009. 47(1): p. 5–10.

- Cann, A.P., A.W. Salmoni, and T.R. Eger, Predictors of whole-body vibration exposure experienced by highway transport truck operators. Ergonomics, 2004. 47(13): p. 1432–53.

- de la Hoz-Torres, M.L., et al., A methodology for assessment of long-term exposure to whole-body vibrations in vehicle drivers to propose preventive safety measures. J Safety Res, 2021. 78: p. 47–58.

- de la Hoz-Torres, M.L., et al., Whole Body Vibration Exposure Transmitted to Drivers of Heavy Equipment Vehicles: A Comparative Case According to the Short- and Long-Term Exposure Assessment Methodologies Defined in ISO 2631-1 and ISO 2631-5. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2022. 19(9).

- Funakoshi, M., et al., Measurement of whole-body vibration in taxi drivers. J Occup Health, 2004. 46(2): p. 119–24. [CrossRef]

- Futatsuka, M., et al., Whole-body vibration and health effects in the agricultural machinery drivers. Ind Health, 1998. 36(2): p. 127–32.

- Johnson, P.W., et al., A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Truck Seat Intervention: Part 1-Assessment of Whole Body Vibration Exposures. Ann Work Expo Health, 2018. 62(8): p. 990–999.

- Kåsin, J.I., N. Mansfield, and A. Wagstaff, Whole body vibration in helicopters: risk assessment in relation to low back pain. Aviat Space Environ Med, 2011. 82(8): p. 790–6.

- Kim, J.H., et al., Whole Body Vibration Exposures and Health Status among Professional Truck Drivers: A Cross-sectional Analysis. Ann Occup Hyg, 2016. 60(8): p. 936–48.

- Lewis, C.A. and P.W. Johnson, Whole-body vibration exposure in metropolitan bus drivers. Occup Med (Lond), 2012. 62(7): p. 519–24.

- Mahbub, M.H., et al., A systematic review of studies investigating the effects of controlled whole-body vibration intervention on peripheral circulation. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging, 2019. 39(6): p. 363–377.

- Mahbub, M.H., et al., Acute Effects of Whole-Body Vibration on Peripheral Blood Flow, Vibrotactile Perception and Balance in Older Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020. 17(3).

- Mandal, B.B. and N.J. Mansfield, Contribution of individual components of a job cycle on overall severity of whole-body vibration exposure: a study in Indian mines. Int J Occup Saf Ergon, 2016. 22(1): p. 142–51. [CrossRef]

- Mayton, A.G., C.C. Jobes, and S. Gallagher, Assessment of whole-body vibration exposures and influencing factors for quarry haul truck drivers and loader operators. Int J Heavy Veh Syst, 2014. 21(3): p. 241–261.

- Mayton, A.G., et al., Investigation of human body vibration exposures on haul trucks operating at U.S. surface mines/quarries relative to haul truck activity. Int J Ind Ergon, 2018. 64: p. 188–198.

- Medina Santiago, A., et al., Diagnosis and Study of Mechanical Vibrations in Cargo Vehicles Using ISO 2631-1:1997. Sensors (Basel), 2023. 23(24).

- Moschioni, G., B. Saggin, and M. Tarabini, Long term WBV measurements on vehicles travelling on urban paths. Ind Health, 2010. 48(5): p. 606–14.

- Orelaja, O.A., et al., Evaluation of Health Risk Level of Hand-Arm and Whole-Body Vibrations on the Technical Operators and Equipment in a Tobacco-Producing Company in Nigeria. J Healthc Eng, 2019. 2019: p. 5723830.

- Rehn, B., et al., Whole-body vibration exposure and non-neutral neck postures during occupational use of all-terrain vehicles. Ann Occup Hyg, 2005. 49(3): p. 267–75.

- Sherwin, L.M., et al., Influence of tyre inflation pressure on whole-body vibrations transmitted to the operator in a cut-to-length timber harvester. Appl Ergon, 2004. 35(3): p. 253–61.

- Wolfgang, R. and R. Burgess-Limerick, Whole-body vibration exposure of haul truck drivers at a surface coal mine. Appl Ergon, 2014. 45(6): p. 1700–4. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X., C. Trask, and A.M. Kociolek, Whole-body vibration exposure of occupational horseback riding in agriculture: A ranching example. Am J Ind Med, 2017. 60(2): p. 215–220.

- Zeng, X., et al., Whole body vibration exposure patterns in Canadian prairie farmers. Ergonomics, 2017. 60(8): p. 1064–1073.

- Tiemessen, I.J., C.T. Hulshof, and M.H. Frings-Dresen, Low back pain in drivers exposed to whole body vibration: analysis of a dose-response pattern. Occup Environ Med, 2008. 65(10): p. 667–75.

- Davies, H.W., et al., Exposure to Whole-Body Vibration in Commercial Heavy-Truck Driving in On- and Off-Road Conditions: Effect of Seat Choice. Ann Work Expo Health, 2022. 66(1): p. 69–78.

- Ittianuwat, R., M. Fard, and K. Kato, Evaluation of seatback vibration based on ISO 2631-1 (1997) standard method: The influence of vehicle seat structural resonance. Ergonomics, 2017. 60(1): p. 82–92.

- Fard, M., et al., Effects of seat structural dynamics on current ride comfort criteria. Ergonomics, 2014. 57(10): p. 1549–61.

- Bovenzi, M. and C.T. Hulshof, An updated review of epidemiologic studies on the relationship between exposure to whole-body vibration and low back pain (1986-1997). Int.Arch.Occup.Environ.Health, 1999. 72(6): p. 351–365. [CrossRef]

- Bernard, B., P., et al., Low back and musculoskeletal disorders: Evidence for work-relatedness., in Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and Workplace Factors, B.P. Bernard and e. al, Editors. 1997, U.S. Dep Health and Human Services - CDC&P - National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). Cincinnati, Oh. p. 6–1–6–39.

- Teschke, K., et al., Whole Body Vibration and Back Disorders Among Motor Vehicle Drivers and Heavy Equipment Operators - A Review of the Scientific. 1999: Vancouver, BC.

- Seidel, H., et al., Intraspinal forces and health risk caused by whole-body vibration – predictions for European drivers.

- and different field conditions. Int J Ind Ergon, 2008. 38: p. 856–867.

- Schmidt, A.L., et al., Risk of lumbar spine injury from cyclic compressive loading. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 2012. 37(26): p. E1614–21. [CrossRef]

- Hulshof, C.T., J.H. Verbeek, and F.J. van Dijk, Development and evaluation of an occupational health services programme on the prevention and control of effects of vibration. Occup.Med.(Lond), 1993. 43 Suppl 1: p. S38–S42.

- Cohen, A.G., CC; Fine, LJ; Bernard, BP; McGlothlin, JD;, ed. Elements of Ergonomics Programs - A Primer Based on Workplace Evaluations of Musculoskeletal Disorder. PB97-144901, ed. N.I.f.O.S.a. Health. 1997, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health: Cincinnati, Ohio.

- (NIOSH), N.I.f.O.S.a.H. Elements of Ergonomics Programs. 2024 [cited 2025 8/24/2025]; The Elements of Ergonomics Programs is a step–by–step guide]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ergonomics/ergo-programs/.

- command, N.a.m.c.f.h.p. Human Vibration Guide. 2023 [cited 2025 8/24/2025]; Human Vibration Guide 2023]. Available from: https://www.med.navy.mil/Portals/62/Documents/NMFA/NMCPHC/root/Industrial%20Hygiene/Human-Vibration-Technical-Guide.pdf.

- Johanning, E., Whole-body vibration-related health disorders in occupational medicine--an international comparison. Ergonomics, 2015. 58(7): p. 1239–52.

| Machinery/Vehicle | Usage / Industry | HGCZ | HGCZ & EU-Directive | EU Directive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | tractor, combine, horse | agriculture | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 2 | helicopter, propeller aircraft | aviation | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | truck, dumper, skidder | construction | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| 4 | forest machine, frame saw, timber harvester | forestry | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | ambulance, wheelchair, MRI | health / medical | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | fork lift, platform, pot hauler | industrial | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 7 | dumpster, haul truck, earth mover, dozer | Mining | 15 | 4 | 0 |

| 8 | ski, snowboards, bicycle, kite | sport | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 9 | bus, cars, taxi, All-Terraine-Vehicle, rail | transport | 3 | 9 | 7 |

| Sum | 30 | 21 | 21 |

| All studies | % | HGCZ | % | HGCZ & EU Directive | % | EU Directive | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total No of studies | 74 | 100% | 30 | 100% | 23 | 100% | 21 | 100 |

| RMS listed | 73 | 99 | 30 | 100 | 22 | 96 | 21 | 100 |

| Crest factor listed | 38 | 51 | 17 | 57 | 14 | 61 | 7 | 33 |

| VDV listed | 52 | 70 | 22 | 73 | 17 | 74 | 13 | 62 |

| ISO 2631-5 included | 17 | 23 | 5 | 17 | 6 | 26 | 6 | 9 |

| Study limitation included | 36 | 49 | 16 | 53 | 10 | 43 | 10 | 48 |

| ISO 2631-1 Annex B limitation | 3 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 4 | n/a | n/a |

| Quantitative guidance | 54 | 73 | 25 | 83 | 14 | 61 | 15 | 71 |

| Qualitative guidance | 20 | 27 | 5 | 17 | 9 | 39 | 6 | 29 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).