1. Introduction

In contemporary scientific communication, figures function as a primary medium for conveying complex ideas. While textual narratives—abstracts, methods, and results—provide comprehensive descriptions, it is often the figures that deliver immediate, intuitive access to the essence of a contribution. The exponential rise in global publication volume has been paralleled by large-scale infrastructures such as PubMed, Semantic Scholar, and ScienceDirect, which facilitate text-centric exploration. However, the automated processing of visual evidence, particularly compound figures, remains comparatively immature. Prior studies underscore that graphical depictions are more cognitively memorable and accessible than text alone [

1,

2], and many landmark contributions rely primarily on figures to convey their insights [

3].

A major bottleneck in this context arises from the ubiquity of compound figures, constituting over 30% of scientific visual material [

4]. Such figures typically combine subimages drawn from distinct experimental conditions, modalities, or conceptual settings. Unlike single-topic illustrations that can be assigned a unified semantic category, compound figures defy monolithic interpretation. This heterogeneity limits their utility in retrieval systems, knowledge extraction pipelines, and automated summarization frameworks. The challenge lies not only in delineating the subfigures visually, but also in preserving the semantic correspondence between each subfigure and its associated textual explanation.

Fortunately, most compound figures are accompanied by captions that explicitly describe their subcomponents. Captions employ symbolic indices to create an alignment between text and corresponding subimages. These indices serve a dual role: they encode spatial layout while simultaneously defining semantic groupings. Exploiting these cues offers a principled way to bridge visual regions and their textual references, suggesting that figure decomposition should be guided not solely by visual segmentation but also by semantic anchoring from captions.

Traditional solutions have approached this problem through heuristic rules and handcrafted layout assumptions [

5,

6,

7], including line-segmentation, region-growing, or morphological filtering. While effective for regular grid-like arrangements, such heuristics collapse when facing irregular or free-form layouts. More critically, they ignore caption semantics, resulting in outputs that may be visually segmented but semantically fragmented.

Data-driven alternatives have attempted to improve robustness. For example, Tsutsui et al.[

8] formulated subfigure localization as an object detection task. This approach successfully identifies distinct visual regions, yet it disregards the symbolic anchors linking them to captions, leaving a semantic gap between figure structure and textual interpretation. Similarly, Shi et al.[

9] advanced the field by proposing grid-aware spatial clustering, but the assumption of layout regularity remains a critical limitation, especially when semantic groupings diverge from visual proximity.

To confront these challenges, we introduce SEMCLIP, a decomposition model that explicitly integrates semantic anchoring into figure parsing. Central to SEMCLIP is the definition of master images: mid-level semantic entities that either correspond to an individual subfigure or aggregate multiple subfigures unified by a shared label. By anchoring decomposition to detected symbolic labels, SEMCLIP ensures a tight coupling between segmented visual regions and caption-based descriptions.

Our framework adopts a two-phase pipeline. In the initial stage, a label detection module identifies caption-like annotations, capturing both positional information and latent semantic grouping. These anchors inform a hypothesized structural layout. In the subsequent stage, this structural prior is fused with localized visual signals—such as saliency cues, boundary continuity, and textural features—to yield master image segments. To address challenges of annotation sparsity and class imbalance, we propose a dual-path training paradigm that decouples optimization for detection and semantic grouping, thereby enhancing generalization across diverse figure layouts.

Unlike existing methods that are constrained by geometric regularity or detached from caption semantics, SEMCLIP dynamically adapts to both hierarchical and irregular structures. Its emphasis on caption-figure coherence guarantees that each decomposed unit is interpretable in both visual and textual domains.

The contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

We present SEMCLIP, a semantic-aware decomposition framework that partitions compound figures into caption-aligned master images.

We introduce a cascaded two-stage design that first localizes symbolic label anchors and then integrates them with visual descriptors for semantic-aware segmentation.

We develop a bifurcated training strategy that alleviates label imbalance and sparsity, resulting in robust decomposition across a wide range of layouts.

2. Related Work

2.1. Compound Figure Parsing in Scientific Literature

Figures serve as a central medium for presenting results, visualizing experimental conditions, and communicating methodological designs. Prior studies highlight that visual elements strongly enhance memorability and visibility of scholarly content [

3]. Within this visual ecosystem, compound figures—constructed from multiple heterogeneous subpanels—represent more than 30% of all figures in research publications [

4]. Although beneficial to human readers, this compositional complexity creates difficulties for automatic systems, which often assume a single semantic focus per figure.

Early research on compound figure parsing primarily relied on heuristic rules and handcrafted segmentation cues. Representative approaches attempted to separate subfigures by exploiting uniform backgrounds [

5], or by leveraging edge and line detection signals [

6], frequently combined with assumptions of spatial alignment or symmetry. Such methods achieved reasonable outcomes on clean, grid-structured layouts, but quickly deteriorated when confronted with irregular arrangements, overlapping components, or inconsistent spacing.

With the adoption of deep learning, the field gradually shifted from rule-driven segmentation to data-driven recognition. Tsutsui et al. [

8] redefined the decomposition task as an object detection problem, applying YOLOv2 [

10] trained on synthetic data to improve generalization. Shi et al. [

9] proposed LADN, a detection framework explicitly incorporating grid layout priors. While these approaches advanced the state of the art, they remain limited in maintaining consistency with caption semantics, which is essential for grounded interpretation and scientific utility. In contrast, SEMCLIP places subfigure labels at the core of the parsing process, using them as semantic anchors to align decomposition with textual descriptions, thereby ensuring interpretability and supporting multimodal reasoning.

2.2. Object Detection as a Basis for Semantic Anchoring

Object detection, a cornerstone of computer vision, addresses the joint challenge of localizing and classifying meaningful objects. Traditional systems built on handcrafted descriptors such as SIFT [

11] and HOG [

12], coupled with sliding-window classifiers. Despite their innovation, these methods were limited by poor scalability and weak robustness in cluttered scenes.

The breakthrough arrived with deep convolutional networks. OverFeat [

13] pioneered dense CNN-based detection, and the R-CNN family [

14,

15,

16] achieved substantial accuracy gains by combining region proposals with dedicated classification modules. However, their two-stage designs incurred significant inference overhead. To remedy this, single-stage detectors emerged, epitomized by the YOLO series [

10,

17,

18], which enabled real-time performance with competitive precision. Among them, YOLOv3 strikes a practical balance between speed and accuracy, making it especially suitable for large-scale processing. In SEMCLIP, this detection paradigm is adopted to identify symbolic annotations such as “(a)” and “(b)”, which then function as semantic anchors. To counter the heavy imbalance and sparsity of such labels in scientific images, we design a dual-branch optimization strategy that decouples detection from semantic association, improving robustness across diverse figure types.

2.3. Modeling Visual Relationships and Contextual Semantics

Understanding visual scenes extends beyond detecting individual entities; it requires modeling the relations among them. Visual Relationship Detection (VRD) tackles this by predicting triplets in the form (subject, predicate, object), thereby capturing structural or functional dependencies. Pioneering work [

20] explored structured learning for relation triplets, while situation recognition [

19] integrated contextual reasoning. Human-centric relational detection was emphasized by Gkioxari et al. [

21], who designed bidirectional mechanisms to capture interaction-specific links.

Building on these insights, SEMCLIP interprets subfigure labels as relational pivots. By explicitly linking labels with their associated subregions, the model embeds a semantic relationship graph between visual components and their textual references. This design ensures that decomposition is not merely a segmentation task but also a process of semantic contextualization, preserving interpretive meaning across the figure as a whole.

2.4. Layout Analysis and Structural Parsing of Documents

Research in document layout analysis provides another relevant foundation. This line of work investigates how to segment and classify diverse document elements—paragraphs, charts, tables, or figures—especially in scanned or digital corpora. Recent approaches have advanced by integrating multimodal signals, combining visual cues, textual embeddings, and spatial configurations to construct coherent document structures.

Such multimodal layout parsers have achieved notable progress in tasks like chart interpretation, table recognition, and diagram segmentation, enabling models to capture logical and hierarchical document relationships. Inspired by this paradigm, SEMCLIP formulates compound figure parsing as a special case of layout interpretation. In this framing, segmentation is guided not only by visual boundaries but also by the structural signals encoded in subfigure labels and captions. This layout-aware stance provides SEMCLIP with the ability to reconcile spatial structure with semantic fidelity.

2.5. Cross-Modal Retrieval and Scientific Knowledge Mining

Finally, our work intersects with cross-modal retrieval and scientific knowledge extraction, both of which seek to align visual figures with textual semantics. Systems in this domain enable figure-to-text retrieval, automated captioning, and the population of knowledge graphs from scholarly literature. Central to these applications is precise subfigure segmentation and robust caption alignment.

SEMCLIP directly contributes to this ecosystem by generating decompositions that preserve semantic alignment between visual subfigures and their caption references. This fine-grained structuring not only facilitates more accurate multimodal representation learning and figure-based search, but also strengthens tasks such as evidence mining and claim verification in scientific discourse.

3. The Proposed Framework

This section introduces the design of our framework, SEMCLIP (Semantic Layout-aware Compound Image Parser), developed to decompose compound figures into mid-level semantic units termed master images. The primary difficulty arises from the fact that such master images do not always coincide with clear pixel-level boundaries nor consistent visual signatures. Hence, classical bottom-up segmentation, which depends mainly on visual similarity, is insufficient for capturing the underlying semantic organization.

To address this ill-posed segmentation scenario, SEMCLIP leverages external semantic cues—namely the symbolic subfigure labels (e.g., “(a)”, “(b)”)—as anchoring references. These labels, which are intrinsically tied to caption text, provide both spatial layout hints and semantic grouping signals. By explicitly incorporating these annotations, SEMCLIP grounds the decomposition process in semantically meaningful structure.

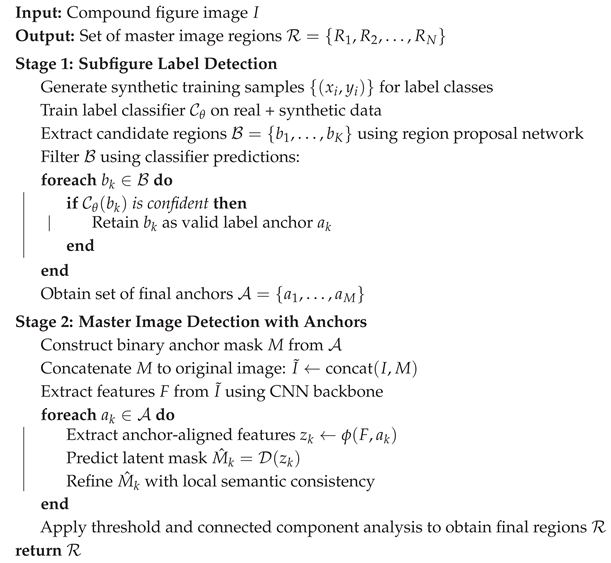

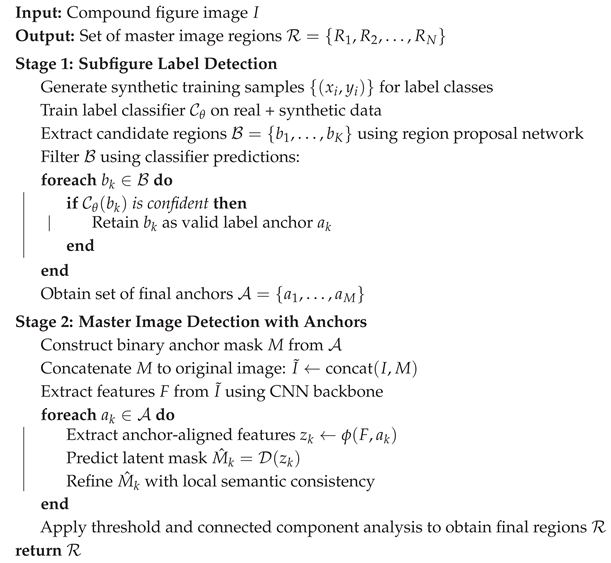

The framework is organized into a two-phase pipeline. The first stage establishes semantic layout priors through a Subfigure Label Detection Module, responsible for locating symbolic labels inside the figure. The second stage exploits this detected layout information to regulate the predictions of the Master Image Detection Module, thereby refining decomposition into coherent units. This hierarchical strategy mirrors how humans typically interpret figures: first identifying labeled cues that reveal structural layout, and then parsing the contained visuals into semantically interpretable groups.

3.1. Subfigure Label Detection for Semantic Layout Priors

The symbolic labels serve as the semantic nucleus of SEMCLIP. Notations like “(a)”, “(b)” encode both spatial positioning and links to descriptive caption spans. Nevertheless, reliably detecting them is non-trivial: severe label imbalance is common, where frequent indices like “(a)” dominate and rare ones like “(h)” are scarcely represented, making naïve classifiers biased.

To counteract this, SEMCLIP separates the task into two synergistic submodules: (1) a balanced label classifier that achieves high recognition fidelity under skewed data, and (2) a region proposal mechanism regularized by semantic consistency from the classifier.

Step 1: Balanced Label Classification with Synthetic Data.

We employ a ResNet-152 based classifier

[

22] trained on a combination of real and synthetically rendered labels, the latter introduced to even out the distribution of classes. Given training samples

with

, the learning objective follows a cross-entropy formulation:

This balanced augmentation strategy ensures that the classifier maintains accuracy across both frequent and rare label categories, achieving robust performance even under long-tailed distributions.

Step 2: Classifier-regularized Region Proposals.

Standard region proposal networks rely solely on geometric overlap for bounding box regression. In contrast, we enforce semantic consistency by integrating classifier predictions into the proposal evaluation. For a candidate

compared to its ground-truth

, we define:

where

tunes the weight, and

activates the semantic constraint when classifier output diverges from the expected label. This design penalizes geometrically valid but semantically inconsistent proposals, yielding a more reliable set of anchors.

By explicitly bifurcating classification and localization while also coupling them via semantic constraints, this stage constructs a strong semantic layout prior that guides subsequent decomposition.

|

Algorithm 1: SEMCLIP: Semantic Layout-aware Compound Image Parsing

|

|

3.2. Anchor-driven Master Image Segmentation

Once symbolic anchors are obtained, the system progresses to segmenting the figure into semantically consistent master images. This component is designed to approximate the human parsing process: leveraging anchors to infer the global structure, followed by refining local visual groupings.

Step 1: Encoding Layout Masks.

Detected anchors are encoded as a binary mask

marking label positions, concatenated with the original image to form:

thus incorporating both raw visual data and structural layout.

Step 2: Feature Extraction and Anchor Projection.

A CNN backbone produces a feature map

from

. Using ROI pooling

, we project anchor coordinates

into latent descriptors:

Step 3: Inferring Latent Masks.

Each descriptor

is passed through a decoder

to predict a soft segmentation mask:

These masks are upsampled and binarized to obtain spatial support for candidate master images.

Step 4: Refining by Semantic Coherence.

To enforce intra-region uniformity, coherence is assessed by comparing pixel features to the region mean:

Regions with coherence below threshold

are retained, filtering out noisy or semantically inconsistent masks.

3.3. Optional Extension: Caption-Guided Matching

To explicitly link subfigures to textual references, we integrate an optional Caption Embedding Alignment Module (CEAM). For each label

, its caption span

is embedded via a language encoder

:

while visual embedding

is obtained from pooled region features. Alignment is optimized through:

which encourages multimodal consistency and can serve as auxiliary supervision when dense caption labels are available.

3.4. Discussion and Design Benefits

The SEMCLIP framework provides several benefits. First, by treating subfigure labels as semantic anchors, segmentation is semantically grounded and each master image remains aligned with its caption reference. Second, label imbalance is effectively addressed by decoupling classification and localization, ensuring rare classes are recognized without degrading frequent ones. Third, the pipeline is inherently interpretable: each stage corresponds to intuitive human-like reasoning steps, from label spotting to structural grouping. This makes SEMCLIP both transparent and reliable. Finally, the modularity of the design allows easy integration of enhancements such as caption alignment or additional semantic filters, extending its utility to downstream tasks including figure retrieval, multimodal QA, and scientific content summarization.

4. Experiments

We now provide a thorough empirical study to validate the performance and reliability of the proposed SEMCLIP framework. Our evaluation encompasses the full pipeline, including subfigure label recognition, label detection, and master image segmentation. To gain deeper insights, we further carry out ablation experiments, domain-transfer assessments, and fine-grained breakdown analyses. This section details dataset construction, training methodology, quantitative benchmarks, qualitative case studies, and diagnostic error analysis.

4.1. Dataset Construction and Annotation Protocol

To enable rigorous testing, we curated a benchmark of 1000 compound figures sourced from prestigious publishers, namely The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC), Springer Nature, and the American Chemical Society (ACS). The corpus spans a wide spectrum of disciplines and figure formats, ranging from microscopy imagery to chemical diagrams. This diversity captures heterogeneous layouts, including clean grids, irregular scatterings, and multimodal composites that combine plots with experimental visuals.

Annotations were carried out using Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Annotators decomposed each compound figure into semantically interpretable units, termed master images, and linked them with their corresponding symbolic labels. Each annotation underwent manual verification to guarantee accuracy in both text correctness and bounding box geometry. Moreover, every subfigure was assigned to one of five semantic categories—microscopy, graph, illustration, diffraction, and chemical structure—enabling richer downstream analysis.

From the entire collection, 794 figures were allocated for training while 198 were reserved for evaluation. This split was chosen to balance statistical sufficiency with layout coverage, ensuring that the test partition reflects both regular and non-standard figure structures.

4.2. Training Procedures and Data Augmentation Strategies

SEMCLIP is trained through a staged process covering three modules: subfigure label classification, label detection, and master image segmentation. Each stage is optimized under a specialized regime to maximize its specific role while remaining compatible with the overall pipeline.

1. Subfigure Label Classifier.

We start by training a ResNet-152 classifier [

22]. The training set blends real subfigure crops with dynamically generated synthetic labels. Synthetic data are created by sampling background patches from figures and overlaying letters in varying fonts, sizes, and styles, rendered stochastically in both upper and lowercase. This augmentation yields balanced distributions across label classes and curtails overfitting. The classifier achieves nearly perfect recognition on validation labels and provides semantic supervision for subsequent detection.

2. Subfigure Label Detector.

Training proceeds in two stages. Initially, a region proposal network is optimized for 10,000 iterations to predict bounding boxes of candidate label regions. Thereafter, fine-tuning for an additional 3,000 iterations incorporates the pretrained classifier, ensuring that candidate regions not only match geometrically but also align semantically. During this phase, bounding boxes are filtered jointly by Intersection-over-Union (IoU) thresholds and classification agreement, thereby reducing false positives and producing reliable anchors.

3. Master Image Detector.

Finally, the master image module is trained for 12,000 iterations using gold-standard label annotations. Each input is augmented with a binary anchor mask derived from detected label positions, concatenated with the original image. This layout-aware representation enables the network to condition predictions on both appearance and structural cues, resulting in subfigure partitions that are semantically consistent.

4.3. Subfigure Label Detection Performance

We report subfigure label detection accuracy in terms of mean Average Precision (mAP), measured across labels “a” through “h”. Three systems are compared: YOLOv3 [

18] as a baseline, SLDv1 (our detector without classifier refinement), and SLDv2 (our final detector with classifier regularization).

As shown in

Table 1, YOLOv3 exhibits substantial variability across classes, especially failing on less frequent labels such as “h”. SLDv1 reduces this disparity by separating classification from localization. SLDv2 yields the best performance overall, raising the average mAP to 88.8%. This improvement stems directly from classifier-guided training, which suppresses semantically inconsistent predictions and compensates for label imbalance.

4.4. Master Image Detection Results

We evaluate master image segmentation by measuring True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), and Average Precision (AP) under IoU threshold 0.5. Our method is benchmarked against the decomposition approach of Tsutsui et al. [

8].

Table 2 shows that SEMCLIP significantly outperforms the baseline, with a 14% increase in AP and a drastic reduction in false positives. Even on irregular and overlapping layouts, our method produces compact, caption-aligned decompositions that maintain semantic validity.

4.5. Ablation Study: Impact of Anchor Mask Encoding

To evaluate the contribution of layout-aware encoding, we compared the full SEMCLIP system with a variant lacking anchor masks. The results are summarized in

Table 3.

The performance drops notably when anchor masks are removed, demonstrating that spatial layout priors are indispensable for distinguishing between closely packed or irregular subfigures. This underscores the importance of explicitly encoding layout cues.

4.6. Cross-Domain Evaluation: Generalization Across Figure Types

We also examine robustness across heterogeneous figure categories.

Table 4 reports detection AP and label accuracy across four figure types.

Despite substantial variation in content and style, SEMCLIP consistently delivers high accuracy across all domains. This suggests strong adaptability to both appearance differences and layout irregularities.

4.7. Qualitative Case Studies and Error Analysis

Finally, we analyze typical failure modes. Errors are most often caused by degraded or occluded labels, inconsistent placement of symbolic annotations, or interference from surrounding graphical elements. Some false positives arise from visually salient text such as legends or axis markers, which the detector confuses with subfigure labels. These errors suggest potential improvements via multimodal integration, e.g., caption grounding or OCR-based restoration of noisy labels.

The experimental evidence confirms that SEMCLIP achieves state-of-the-art performance in compound figure decomposition. Its integration of semantic anchors, classifier-informed detection, and layout priors yields significant gains across benchmarks. Ablation results demonstrate the necessity of each component, while cross-domain analysis establishes robustness across scientific disciplines. Altogether, SEMCLIP emerges as a reliable foundation for figure understanding and multimodal retrieval.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This work presented SEMCLIP, a semantic-driven framework designed for decomposing compound figures in scientific literature. In contrast to conventional heuristic or grid-based methods, SEMCLIP exploits symbolic subfigure labels as semantic anchors and integrates them with learned visual representations to achieve layout-guided decomposition. Through this anchor-centric design, the model is able to extract intermediate-level master images that simultaneously maintain structural integrity and semantic alignment with associated captions. By coupling a robust subfigure label detector with a layout-aware segmentation module, SEMCLIP effectively resolves the inherent ambiguity of compound figures and establishes a principled bridge between visual structure and textual semantics.

Empirical validation across a carefully constructed dataset demonstrates that SEMCLIP consistently surpasses existing baselines. Significant improvements are observed in both label detection and master image segmentation, particularly under challenging scenarios involving irregular layouts or skewed label distributions. The two-phase training paradigm—comprising classifier-regularized detection followed by anchor-guided segmentation—proves highly effective, enabling generalization across multiple categories such as microscopy images, illustrations, and structured graphs.

Nevertheless, several limitations remain, pointing toward fertile directions for future exploration. A primary concern is the sequential dependency inherent in our pipeline. Errors originating from the label detection stage can propagate downstream and compromise segmentation, e.g., undetected labels may result in entire regions being omitted from decomposition. Addressing this cascading error issue could involve integrating multi-hypothesis detection, confidence calibration, or redundancy-aware reasoning to mitigate the risk of early-stage failures.

Another limitation arises from reliance on fixed anchor priors during detection. Although anchor-based frameworks improve efficiency, predefined aspect ratios can misalign with real-world scientific figures that exhibit skewed, rotated, or irregular shapes. This misalignment can degrade boundary precision for master images. Future work may leverage adaptive anchor generation strategies or transition toward anchor-free paradigms, such as keypoint- or center-based detection models, which dynamically infer spatial priors directly from data distributions.

A further avenue lies in deepening the integration of caption semantics. While SEMCLIP already leverages subfigure labels as explicit semantic cues, the broader linguistic context encoded in captions—such as experimental conditions, cross-panel dependencies, or narrative hierarchies—is not yet fully exploited. Incorporating natural language understanding components that align figure layouts with caption discourse could unlock richer multimodal reasoning capabilities and improve scientific interpretability.

Finally, the principles introduced by SEMCLIP can be extended beyond figure parsing toward holistic document-level visual understanding. Potential applications include automated figure-caption alignment, diagram reconstruction, visual explanation of experimental workflows, and scientific visual question answering. Realizing these goals will require large-scale multimodal pretraining objectives, expanded domain diversity, and more scalable annotation pipelines. We regard SEMCLIP as an important step toward unified modeling of structured scientific visuals and anticipate that it will inspire further progress at the intersection of vision, language, and scientific AI.

References

- Colin Ware, Information visualization: perception for design, Elsevier, 2012.

- Douglas L Nelson, Valerie S Reed, and John R Walling, “Pictorial superiority effect.,” Journal of experimental psychology: Human learning and memory, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 523, 1976.

- Po-shen Lee, Jevin D West, and Bill Howe, “Viziometrics: Analyzing visual information in the scientific literature,” IEEE Transactions on Big Data, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 117–129, 2017.

- Alba G Seco de Herrera, Stefano Bromuri, Roger Schaer, and Henning Müller, “Overview of the medical tasks in imageclef 2016,” CLEF Working Notes. Evora, Portugal, 2016.

- Po-Shen Lee and Bill Howe, “Detecting and dismantling composite visualizations in the scientific literature,” in International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods. Springer, 2015, pp. 247–266.

- Mario Taschwer and Oge Marques, “Automatic separation of compound figures in scientific articles,” Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 77, no. 1, pp. 519–548, 2018.

- Pengyuan Li, Xiangying Jiang, Chandra Kambhamettu, and Hagit Shatkay, “Compound image segmentation of published biomedical figures,” Bioinformatics, vol. 34, no. 7, pp. 1192–1199, 2017.

- Satoshi Tsutsui and David J Crandall, “A data driven approach for compound figure separation using convolutional neural networks,” in 2017 14th IAPR International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR). IEEE, 2017, vol. 1, pp. 533–540.

- Xiangyang Shi, Yue Wu, Huaigu Cao, Gully Burns, and Prem Natarajan, “Layout-aware subfigure decomposition for complex figures in the biomedical literature,” in ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2019, pp. 1343–1347.

- Joseph Redmon and Ali Farhadi, “Yolo9000: better, faster, stronger,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2017, pp. 7263–7271.

- David G Lowe, “Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints,” International journal of computer vision, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 91–110, 2004.

- Navneet Dalal and Bill Triggs, “Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection,” 2005.

- Pierre Sermanet, David Eigen, Xiang Zhang, Michaël Mathieu, Rob Fergus, and Yann LeCun, “Overfeat: Integrated recognition, localization and detection using convolutional networks,”. arXiv, 2013; arXiv:1312.6229.

- Ross Girshick, “Fast r-cnn,” in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, 2015, pp. 1440–1448.

- Shaoqing Ren, Kaiming He, Ross Girshick, and Jian Sun, “Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks,” in Advances in neural information processing systems, 2015, pp. 91–99.

- Ross Girshick, Jeff Donahue, Trevor Darrell, and Jitendra Malik, “Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2014, pp. 580–587.

- Joseph Redmon, Santosh Divvala, Ross Girshick, and Ali Farhadi, “You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 779–788.

- Joseph Redmon and Ali Farhadi, “Yolov3: An incremental improvement,”. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1804.02767.

- Mark Yatskar, Luke Zettlemoyer, and Ali Farhadi, “Situation recognition: Visual semantic role labeling for image understanding,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2016, pp. 5534–5542.

- Cewu Lu, Ranjay Krishna, Michael Bernstein, and Li Fei-Fei, “Visual relationship detection with language priors,” in European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, 2016, pp. 852–869.

- Georgia Gkioxari, Ross Girshick, Piotr Dollár, and Kaiming He, “Detecting and recognizing human-object interactions,” in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2018, pp. 8359–8367.

- Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun, “Deep residual learning for image recognition,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 4171–4186.

- Endri Kacupaj, Kuldeep Singh, Maria Maleshkova, and Jens Lehmann. 2022. An Answer Verbalization Dataset for Conversational Question Answerings over Knowledge Graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.06734, arXiv:2208.06734 (2022).

- Magdalena Kaiser, Rishiraj Saha Roy, and Gerhard Weikum. 2021. Reinforcement Learning from Reformulations In Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 459–469.

- Yunshi Lan, Gaole He, Jinhao Jiang, Jing Jiang, Wayne Xin Zhao, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2021. A Survey on Complex Knowledge Base Question Answering: Methods, Challenges and Solutions. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-21. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 4483–4491. Survey Track.

- Yunshi Lan and Jing Jiang. 2021. Modeling transitions of focal entities for conversational knowledge base question answering. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers).

- Mike Lewis, Yinhan Liu, Naman Goyal, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Omer Levy, Veselin Stoyanov, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2020. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 7871–7880.

- Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter. 2019. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Pierre Marion, Paweł Krzysztof Nowak, and Francesco Piccinno. 2021. Structured Context and High-Coverage Grammar for Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) 2021.

- Pradeep, K. Atrey, M. Anwar Hossain, Abdulmotaleb El Saddik, and Mohan S. Kankanhalli. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: a survey. Multimedia Systems 2010, 16, 345–379. [Google Scholar]

- Meishan Zhang, Hao Fei, Bin Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yixin Cao, Fei Li, and Min Zhang. Recognizing everything from all modalities at once: Grounded multimodal universal information extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2024, 2024.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, and Tat-Seng Chua. Universal scene graph generation. Proceedings of the CVPR 2025.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Jingkang Yang, Xiangtai Li, Juncheng Li, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. Learning 4d panoptic scene graph generation from rich 2d visual scene. Proceedings of the CVPR 2025.

- Yaoting Wang, Shengqiong Wu, Yuecheng Zhang, Shuicheng Yan, Ziwei Liu, Jiebo Luo, and Hao Fei. Multimodal chain-of-thought reasoning: A comprehensive survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.12605, arXiv:2503.12605, 2025.

- Hao Fei, Yuan Zhou, Juncheng Li, Xiangtai Li, Qingshan Xu, Bobo Li, Shengqiong Wu, Yaoting Wang, Junbao Zhou, Jiahao Meng, Qingyu Shi, Zhiyuan Zhou, Liangtao Shi, Minghe Gao, Daoan Zhang, Zhiqi Ge, Weiming Wu, Siliang Tang, Kaihang Pan, Yaobo Ye, Haobo Yuan, Tao Zhang, Tianjie Ju, Zixiang Meng, Shilin Xu, Liyu Jia, Wentao Hu, Meng Luo, Jiebo Luo, Tat-Seng Chua, Shuicheng Yan, and Hanwang Zhang. On path to multimodal generalist: General-level and general-bench. In Proceedings of the ICML, 2025.

- Jian Li, Weiheng Lu, Hao Fei, Meng Luo, Ming Dai, Min Xia, Yizhang Jin, Zhenye Gan, Ding Qi, Chaoyou Fu, et al. A survey on benchmarks of multimodal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.08632, arXiv:2408.08632, 2024.

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dong Yu Li Deng. Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. NOW Publishers, May 2014. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deep-learning-methods-and-applications/.

- Eric Makita and Artem Lenskiy. A movie genre prediction based on Multivariate Bernoulli model and genre correlations. (May), mar 2016a. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.08608.

- Junhua Mao, Wei Xu, Yi Yang, Jiang Wang, and Alan L Yuille. Explain images with multimodal recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.1090, arXiv:1410.1090, 2014.

- Deli Pei, Huaping Liu, Yulong Liu, and Fuchun Sun. Unsupervised multimodal feature learning for semantic image segmentation. In The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pp. 1–6. IEEE, aug 2013. ISBN 978-1-4673-6129-3. 10.1109/IJCNN.2013.6706748. URL http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?arnumber=6706748.

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, arXiv:1409.1556, 2014.

- Richard Socher, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng. Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer. In C J C Burges, L Bottou, M Welling, Z Ghahramani, and K Q Weinberger (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26, pp. 935–943. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5027-zero-shot-learning-through-cross-modal-transfer.pdf.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Enhancing video-language representations with structural spatio-temporal alignment. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024.

- A. Karpathy and L. Fei-Fei, “Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions,” TPAMI, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 664–676, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Retrofitting structure-aware transformer language model for end tasks. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2151–2161, 2020a.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Meishan Zhang, Yijiang Liu, Chong Teng, and Donghong Ji. Mastering the explicit opinion-role interaction: Syntax-aided neural transition system for unified opinion role labeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 11513–11521, 2022.

- Wenxuan Shi, Fei Li, Jingye Li, Hao Fei, and Donghong Ji. Effective token graph modeling using a novel labeling strategy for structured sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4232–4241, 2022.

- Hao Fei, Yue Zhang, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Latent emotion memory for multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 7692–7699, 2020b.

- Fengqi Wang, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Jingye Li, Shengqiong Wu, Fangfang Su, Wenxuan Shi, Donghong Ji, and Bo Cai. Entity-centered cross-document relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 9871–9881, 2022.

- Ling Zhuang, Hao Fei, and Po Hu. Knowledge-enhanced event relation extraction via event ontology prompt. Inf. Fusion 2023, 100, 101919.

- Adams Wei Yu, David Dohan, Minh-Thang Luong, Rui Zhao, Kai Chen, Mohammad Norouzi, and Quoc V Le. Qanet: Combining local convolution with global self-attention for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09541, arXiv:1804.09541, 2018.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11719, arXiv:2305.11719, 2023a.

- Jundong Xu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, Qian Liu, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Faithful logical reasoning via symbolic chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18357, arXiv:2405.18357, 2024.

- Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. SearchQA: A new Q&A dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.05179, arXiv:1704.05179, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Bobo Li, Fei Li, Libo Qin, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Lasuie: Unifying information extraction with latent adaptive structure-aware generative language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022, pages 15460–15475, 2022a.

- Guang Qiu, Bing Liu, Jiajun Bu, and Chun Chen. Opinion word expansion and target extraction through double propagation. Computational linguistics, 2011; 27.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, Donghong Ji, and Xiaohui Liang. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 2021; 22.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Cross2StrA: Unpaired cross-lingual image captioning with cross-lingual cross-modal structure-pivoted alignment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2593–2608, 2023b.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Tat-seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2024a. Multimodal emotion-cause pair extraction with holistic interaction and label constraint. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications, 2024.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Shengqiong Wu, Lizi Liao, Yinwei Wei, Tat-Seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2025. Revisiting conversation discourse for dialogue disentanglement. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 2025; 43, 1.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Yuhan Wu, Jinsong Zhang, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Yijiang Liu, Lizi Liao, Tat-Seng Chua, and Donghong Ji. 2023. DiaASQ: A Benchmark of Conversational Aspect-based Sentiment Quadruple Analysis. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2023. 13449–13467.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. 2024b. Harnessing holistic discourse features and triadic interaction for sentiment quadruple extraction in dialogues. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, Vol. 38. 18462–18470.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, William Yang Wang, Shuicheng Yan, and Tat-Seng Chua. 2025a. Combating Multimodal LLM Hallucination via Bottom-Up Holistic Reasoning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 39. 8460–8468.

- Shengqiong Wu, Weicai Ye, Jiahao Wang, Quande Liu, Xintao Wang, Pengfei Wan, Di Zhang, Kun Gai, Shuicheng Yan, Hao Fei, et al. 2025b. Any2caption: Interpreting any condition to caption for controllable video generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.24379, arXiv:2503.24379 (2025).

- Han Zhang, Zixiang Meng, Meng Luo, Hong Han, Lizi Liao, Erik Cambria, and Hao Fei. 2025. Towards multimodal empathetic response generation: A rich text-speech-vision avatar-based benchmark. In Proceedings of the ACM on Web Conference 2025. 2872–2881.

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-seng Chua. 2025. Grammar induction from visual, speech and text. Artificial Intelligence 2025, 41, 104306.

- Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05250, arXiv:1606.05250, 2016.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Bobo Li, and Donghong Ji. Encoder-decoder based unified semantic role labeling with label-aware syntax. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 12794–12802, 2021a.

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in ICLR, 2015.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. Better combine them together! integrating syntactic constituency and dependency representations for semantic role labeling. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 549–559, 2021b.

- K. Papineni, S. K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in ACL, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Hao Fei, Bobo Li, Qian Liu, Lidong Bing, Fei Li, and Tat-Seng Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11255, arXiv:2305.11255, 2023a.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. 10.18653/v1/N19-1423. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Leigang Qu, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. CoRR 2023, abs/2309.05519.

- Qimai Li, Zhichao Han, and Xiao-Ming Wu. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Meishan Zhang, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Video-of-thought: Step-by-step video reasoning from perception to cognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024b.

- Naman Jain, Pranjali Jain, Pratik Kayal, Jayakrishna Sahit, Soham Pachpande, Jayesh Choudhari, et al. Agribot: agriculture-specific question answer system. IndiaRxiv 2019.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Dysen-vdm: Empowering dynamics-aware text-to-video diffusion with llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7641–7653, 2024c.

- Mihir Momaya, Anjnya Khanna, Jessica Sadavarte, and Manoj Sankhe. Krushi–the farmer chatbot. In 2021 International Conference on Communication information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Chenliang Li, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, and Donghong Ji. Inheriting the wisdom of predecessors: A multiplex cascade framework for unified aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, pages 4096–4103, 2022b.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Donghong Ji, and Jingye Li. Learn from syntax: Improving pair-wise aspect and opinion terms extraction with rich syntactic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3957–3963, 2021.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Chong Teng, Tat-Seng Chua, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5923–5934, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Qian Liu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Scene graph as pivoting: Inference-time image-free unsupervised multimodal machine translation with visual scene hallucination. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5980–5994, 2023b.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: an automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments,” in IEEMMT, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Vitron: A unified pixel-level vision llm for understanding, generating, segmenting, editing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2024,, 2024d.

- Abbott Chen and Chai Liu. Intelligent commerce facilitates education technology: The platform and chatbot for the taiwan agriculture service. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning 2021, 11, 1–10.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Xiangtai Li, Jiayi Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Towards semantic equivalence of tokenization in multimodal llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05127, arXiv:2406.05127, 2024.

- Jingye Li, Kang Xu, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. MRN: A locally and globally mention-based reasoning network for document-level relation extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 1359–1370, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, and Meishan Zhang. Matching structure for dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, pages 6373–6391, 2022c.

- Hu Cao, Jingye Li, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Bobo Li, Liang Zhao, and Donghong Ji. OneEE: A one-stage framework for fast overlapping and nested event extraction. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 1953–1964, 2022.

- Isakwisa Gaddy Tende, Kentaro Aburada, Hisaaki Yamaba, Tetsuro Katayama, and Naonobu Okazaki. Proposal for a crop protection information system for rural farmers in tanzania. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2411.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management 2020, 57, 102311.

- Jingye Li, Hao Fei, Jiang Liu, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Chong Teng, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Unified named entity recognition as word-word relation classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 10965–10973, 2022.

- Mohit Jain, Pratyush Kumar, Ishita Bhansali, Q Vera Liao, Khai Truong, and Shwetak Patel. Farmchat: a conversational agent to answer farmer queries. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies 2018, 2, 1–22.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Imagine that! abstract-to-intricate text-to-image synthesis with scene graph hallucination diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 79240–79259, 2023d.

- P. Anderson, B. P. Anderson, B. Fernando, M. Johnson, and S. Gould, “SPICE: semantic propositional image caption evaluation,” in ECCV, 2016, pp. 382–398.

- Hao Fei, Tat-Seng Chua, Chenliang Li, Donghong Ji, Meishan Zhang, and Yafeng Ren. On the robustness of aspect-based sentiment analysis: Rethinking model, data, and training. ACM Transactions on Information Systems 2023, 41, 50:1–50:32.

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Bobo Li, Meishan Zhang, Jianguo Wei, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Constructing holistic spatio-temporal scene graph for video semantic role labeling. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5281–5291, 2023a.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14734–14751, 2023e.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, and Donghong Ji. Nonautoregressive encoder-decoder neural framework for end-to-end aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023, 34, 5544–5556. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03044, 2015; 2, 5arXiv:1502.03044, 2(3):5, 2015.

- Seniha Esen Yuksel, Joseph N Wilson, and Paul D Gader. Twenty years of mixture of experts. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2012, 23, 1177–1193.

- Sanjeev Arora, Yingyu Liang, and Tengyu Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. In ICLR, 2017.

Table 1.

Subfigure label detection evaluated using mAP across classes.

Table 1.

Subfigure label detection evaluated using mAP across classes.

| Method |

a |

b |

c |

d |

e |

f |

g |

h |

average |

| YOLOv3 |

85.3% |

92.2% |

78.6% |

86.0% |

67.5% |

69.3% |

67.7% |

71.0% |

77.2% |

| SLDv1 |

87.5% |

92.4% |

86.2% |

88.4% |

86.2% |

83.0% |

79.6% |

78.1% |

85.1% |

| SLDv2 |

88.3% |

93.4% |

85.4% |

88.5% |

85.7% |

87.8% |

84.7% |

96.7% |

88.8% |

Table 2.

Compound figure decomposition results at IoU > 0.5.

Table 2.

Compound figure decomposition results at IoU > 0.5.

| Method |

True Positive |

False Positive |

AP |

| Tsutsui et al. |

900 |

309 |

80.23% |

| SEMCLIP (Ours) |

961 |

24 |

94.38% |

Table 3.

Ablation results on anchor mask encoding.

Table 3.

Ablation results on anchor mask encoding.

| Setting |

AP |

| w/o Anchor Mask |

87.29% |

| Full SEMCLIP |

94.38% |

Table 4.

Cross-type evaluation on different figure categories.

Table 4.

Cross-type evaluation on different figure categories.

| Figure Type |

Detection AP |

Label Accuracy |

| Microscopy |

95.6% |

98.3% |

| Graph |

93.8% |

99.2% |

| Illustration |

92.5% |

97.1% |

| Structure |

94.3% |

98.0% |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).