1. Introduction

The Syrian conflict, which began in 2011, has become one of the most devastating humanitarian crises of the 21st century. Many of the approximately 6-7 million Syrians who fled the country had limited agency in the decision to flee, compounding their trauma and heightening their vulnerability [

1]. Research has shown that exposure to war-related violence, in combination with the fear, instability, and uncertainty of forced migration, significantly increases the risk of psychological distress, impacting emotional, cognitive, behavioural, physical, and social development [

2,

3,

4]. Since 2015, approximately 60,000 Syrian refugees have resettled in Canada, contributing to an increased need for accessible, culturally sensitive, and trauma-informed healthcare and social support services [

5].

Research consistently highlights the high prevalence of both mental and physical health challenges among Syrian refugees. A study conducted in Denmark reported that Syrian refugees are over ten times more likely to develop depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared to the general population [

6]. In Germany, refugees from Syria showed significantly higher prevalence rates for depression and anxiety [

3,

7]. Studies focusing on other vulnerable populations exposed to adverse mental health outcomes have also shown significantly increased rates of serious somatic comorbidities [

8,

9,

10]. For instance, war veterans suffering from mental health concerns were at significantly higher risk to develop physical health problems including cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, chronic pain conditions, gastrointestinal illnesses, and cancer [

11]. Whether somatic pathology precedes the onset of mental disorders or arises as a consequence, the co-occurrence of mental and physical illness represents a potent interaction that amplifies overall health vulnerability [

8].

Mental disorders are typically diagnosed using standardized clinical assessments grounded in the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Two widely used and validated clinical and diagnostic tools include the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for screening, diagnosing, and monitoring the severity of depression [

12,

13,

14], and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) for generalized anxiety [

15,

16]. Each of these psychometric assessments carries its own strengths and limitations; however, a common drawback across all is the inherent subjectivity of self-reported responses. A persistent challenge in mental health research has been the reliance on symptom-based, self-perceived diagnostic systems [

17]. The development of objective diagnostic tools based on biological changes to complement these assessments would increase clinical reliability. Integrating validated metabolic biomarkers alongside traditional psychometric instruments could provide critical support in both improving diagnostic accuracy for specific mental health conditions and guiding more personalized, biologically informed treatment strategies.

The emerging field of metabolomics offers powerful insights into the dynamic metabolic responses of living systems to both pathophysiological challenges and epigenetic regulation linked to trauma and stress [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Metabolomics has been successful in disease diagnosis, including neurological and psychiatric disorders, cancers, and metabolic and cardiovascular diseases [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Psychiatric disorders and altered mental health states may be reflected in discrete metabolic changes that can be identified through biochemical pathway information. Thus, metabolomics may potentially discover robust predictive, diagnostic, and prognostic biomarkers [

21,

27,

29,

30]. The use of proton nuclear magnetic resonance (

1H NMR) spectroscopy in metabolomics is particularly effective in untargeted discovery of biological signaling pathways or metabolic fingerprints linked to pathophysiological states using clinically accessible biofluids [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. As saliva collection is the most accessible and least invasive clinical sample, it is becoming a prominent choice for large-scale, longitudinal biomarker identification [

37,

38,

39]. Notably, saliva contains 308 quantifiable metabolites that change significantly in response to a variety of different physiological states and stressors, of which 76 can be detected and quantified by NMR analyses [

40].

The present study was designed to determine whether 1H NMR spectroscopy of saliva can be used to identify metabolomic biomarkers associated with mental health outcomes among individuals from the Syrian refugee community. Participants were invited to complete psychometric assessments measuring symptoms of depression and generalized anxiety disorder, which were evaluated both individually and through a composite stress score. Based on these assessments, participants were grouped according to relative levels of psychological distress to identify salivary metabolites that may reflect symptoms of depression and anxiety. This approach seeks to integrate objective biological measures with lived experience to better understand and support the mental well-being of individuals affected by forced displacement and trauma.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Recruitment and Psychometric Assessments

This study included 88 Syrian adults (female n=44; male n=44) recruited through Lethbridge Family Services – Immigrant Services. Each participant was invited to complete two questionnaires in English or Arabic: the PHQ-9 for depression and the GAD-7 for generalized anxiety disorder. The session was facilitated with the support of translators fluent in Syrian Arabic and familiar with the cultural context of the participants.

Each assessment was scored based on the respective scoring guides, which was then used to help divide the participants into comparison groups meeting the diagnostic criteria for depression and anxiety, and overall mental distress (a composite score). The PHQ-9 and the GAD-7 were each given a score from 0 to 3 with respect to the symptom severity (0 being no prevalence, 1 being low, 2 being moderate, and 3 being severe). Composite stress scores were formulated based on a sum of both assessments, ranging from a score of 0-3 as low stress, and 4-6 as high stress. Depression and anxiety comparisons were also considered independently based on their corresponding test. Low anxiety and depression were scored as 0 to 1, while high anxiety and depression were scored as 2 to 3.

2.2. Saliva Sample Collection

Saliva sample collection via Salimetrics SalivaBio Oral Swab kits (Salimetrics, PA, USA) was performed in the evening at the time when the three psychometric assessments were completed. Participants were instructed to abstain from eating, drinking, smoking, chewing gum, or engaging in oral hygiene activities for at least one hour prior to saliva sample collection. Prior to sample collection, participants rinsed their mouth with water and waited approximately ten minutes to ensure proper salivary flow. Salivettes were then given and placed under participants’ tongues. After two minutes, the salivettes were placed in conical tubes and kept on dry ice for transport and were subsequently stored at −80 °C until further processing.

2.3. Sample Preparation

Samples were removed from a -80 o C freezer and allowed to thaw to room temperature. To collect the saliva, salivettes were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 1,500 g. For each sample, 200 μL of collected saliva, 320 μL of phosphate buffer, and 80 μL of D2O were pipetted into 2 mL microfuge tubes to be centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4o C. Phosphate buffer was prepared as a 4:1 ratio of KH2PO4:K2HPO4 in a 4:1 H2O:D2O solution to obtain a final concentration of 0.5 M. The D2O contained a weight per volume (w/v) ratio of 0.02709 trimethylsilylpropanoic acid (TSP) as a chemical shift reference for 1H NMR spectroscopy. Sodium azide (NaN3, 0.03% w/v) was added as an antimicrobial agent, and total buffer pH was titrated to 7.40 using 3M HCl. Following centrifugation, the prepared samples were returned to the -80o C freezer for future 1H NMR analysis. On the day of sample analysis in the 1H NMR spectrometer, the microfuge tubes were removed from the -80o C freezer, allowed to thaw at room temperature and 550 μL of supernatant was transferred to labelled 5 mm NMR tubes.

2.4. NMR Data Acquisition and Processing

The data were acquired using a 700 MHz Bruker Avance III HD spectrometer (Bruker, ON, Canada), equipped with a 5 mm triple resonance TBO-Z probe. The Bruker 1-D NOESY gradient water suppression pulse sequence ‘noesygppr1d’ was used. The data were collected according to the procedures outlined in Paxman et al. (2018) [

22]. The spectra were phase shifted, baseline corrected, and line-broadened by 0.3 Hz using TopSpin 3.5 patch level 7 (Bruker BioSpin, Billerica, MA, USA). All spectra were converted to ascii files and exported to MATLAB (MathWorks, MA, USA) for further analysis. The spectra underwent dynamic adaptive binning (DAB) [

41], followed by manual adjustment to correct for any errors in the algorithm. The bin containing the water peak was removed resulting in a total of 332 bins for all saliva spectra. The spectra were normalized to the total area of all bins, log transformed, and Pareto scaled. All spectra peaks were referenced to TSP (0.00δ) [

42].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Three hundred and thirty-two bins in NMR spectra were first analyzed for all comparison groups and deemed significant or non-significant using a decision tree algorithm [

43]. The 332 bins were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilkes test, followed by the Mann-Whitney U test and all p-values were Bonferroni-Holm corrected for multiple comparisons. As an additional bin selection method, variable importance analysis based on random variable combination (VIAVC) was used [

44]. The framework of VIAVC includes binary matrix resampling, which (1) guarantees that each variable has been selected with the same probability and generated different variable combinations, (2) the importance of each variable by assessing the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve [

45], and (3) outputting the rank of the final remaining informative variables. Model classification was determined using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and orthogonal projection of latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) [

46] in MetaboanalystR 3.0 [

47]. The Human Metabolome Database and the Chenomx 8.5 NMR Suite (Chenomx Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada) were used for metabolite identification (Wishart, 2018). Pathway topology analysis was completed using MetaboAnalyst by selecting the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database for

homo sapiens as the library, the hypergeometric test for over-representation analysis, and relative betweenness for the topology analysis [

48,

49].

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

Of the total samples collected (n=88), 30 samples (18 female, 12 male) had an insufficient amount of saliva for NMR analysis (new n=58; female n=26, male n=32). Due to several incomplete surveys, only those who completed all sections of the associated questionnaires were considered for further analysis. The final composite comparison therefore included 21 females (11 low and 10 high scores) and 31 males (21 low and 10 high scores). The depression comparison included 26 females (15 low and 11 high levels) and 32 males (18 low and 14 high levels). Finally, the anxiety comparison included 26 females (16 low and 10 high levels) and 32 males (25 low and 7 high levels).

Table 1 shows a summary of the sociodemographic variables deemed to possibly influence the metabolic makeup of the participants in the study. This information was obtained at the time of sample collection.

3.2. Mental Health and Distress Have a Long-term Impact on Metabolomic Profiles

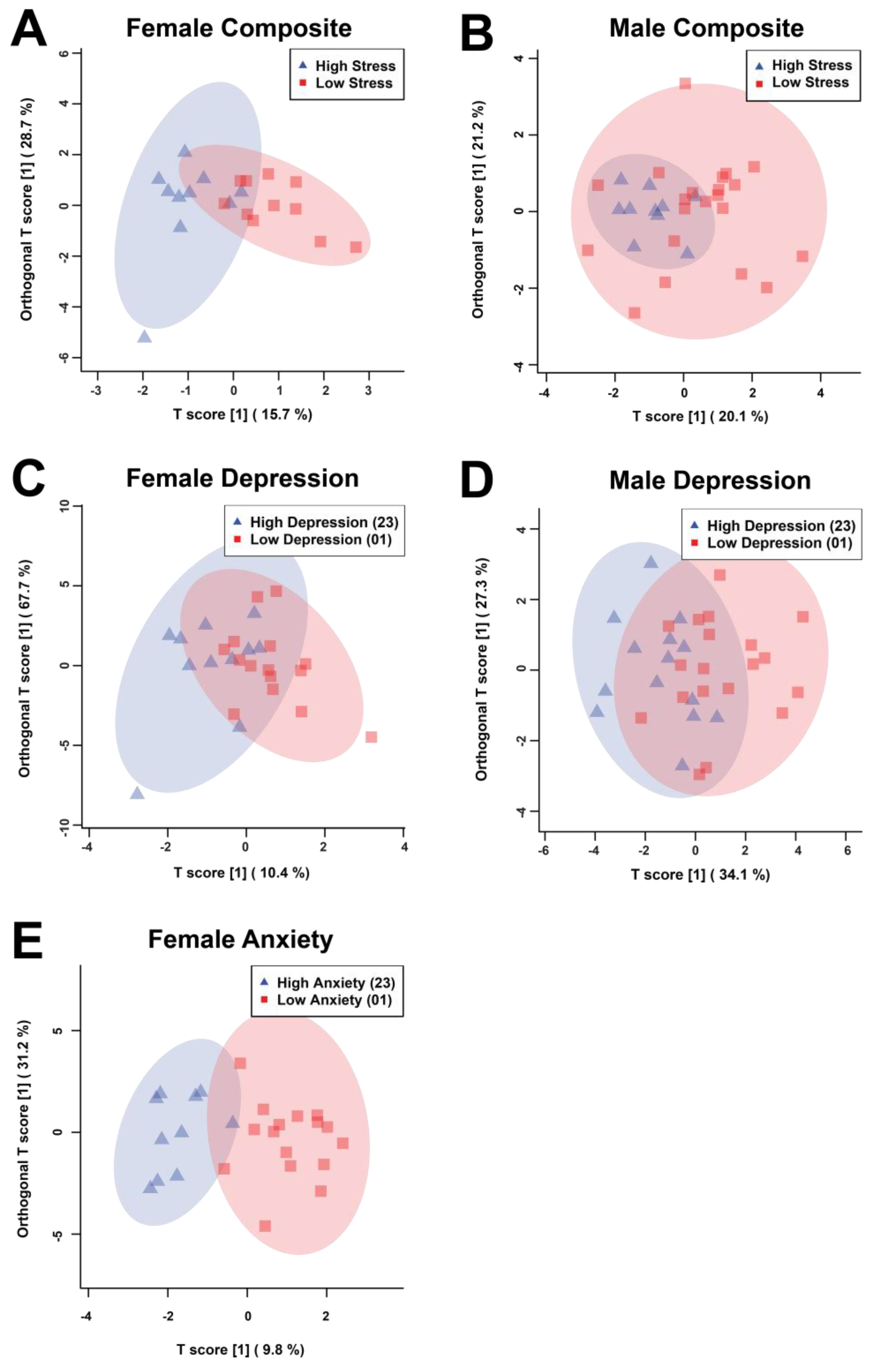

The statistical analysis included 332 bins created from the spectra of the salivary metabolomic profiles. The bins determined to be significant by either the univariate Mann-Whitney U (MW) test or the multivariate variable importance analysis based on random variable combination (VIAVC) tests were used to construct orthogonal projection of latent structures discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) scores plots for all of the comparisons (

Figure 1, Supplementary

Table 1). The male anxiety comparison’s sample population and distribution failed to pass permutation testing and was therefore not continued for analysis. These tests examined which bins led to differences in metabolic profiles between the associated comparison groups. These analyses resulted in the following subdivision of bins: female composite (

Figure 1A) - 2 MW and 8 VIAVC bins; male composite (

Figure 1B) - 3 MW and 8 VIAVC bins; female depression (

Figure 1C) - 2 MW and 15 VIAVC bins; male depression (

Figure 1D) - 10 MW and 5 VIAVC bins; and female anxiety (

Figure 1E) - 7 MW and 22 VIAVC bins.

In male composite distress scores, there was complete overlap between the high and low groups, as indicated by both a poor quality of the model (Q2) and variation explained by the model (R2) that did not pass cross-validation (Q2 = –0.114, p = 0.286; R2 = 0.203, p = 0.433), whereas female composite distress scores had more notable group separation and passed cross-validation (Q2 = 0.388, p = 0.0035; R2 = 0.626, p = 0.007). For depression, males had more discernable separation than their composite distress scores and passed cross-validation (Q2 = 0.115, p = 0.0355; R2 = 0.366, p = 0.0435) and females still had separation that passed cross-validation (Q2 = 0.199, p = 0.0225; R2 = 0.396, p = 0.016), but the separation was less than observed for their composite distress scores. Female anxiety was found to have the best group classification and passed cross-validation testing (Q2 = 0.254, p = 0.0115; R2 = 0.765, p = 0.0025).

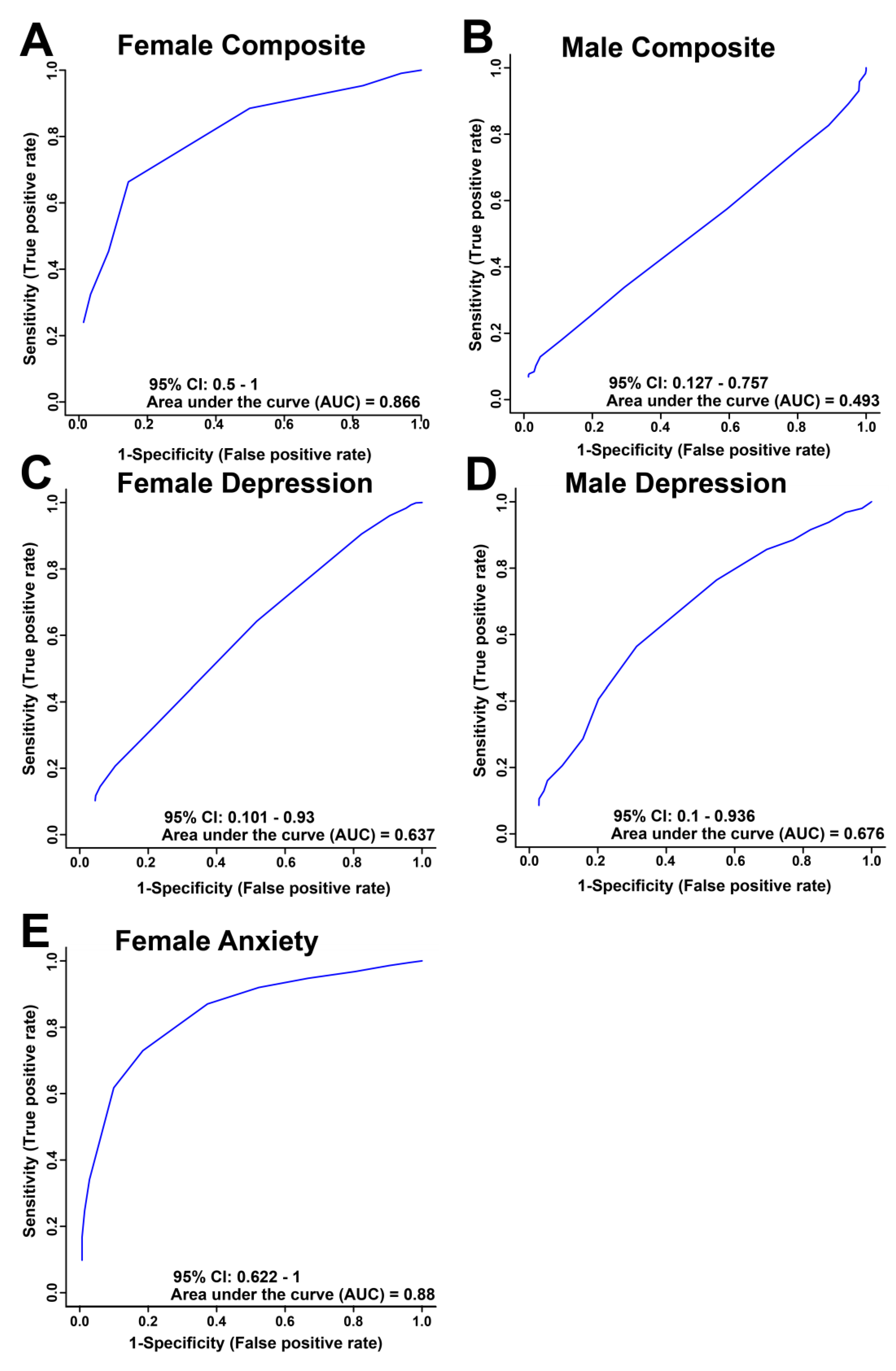

Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were used to determine the sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of each comparison model using the metabolite bins identified as significantly altered by VIAVC testing (

Figure 2). The comparisons of high and low for both female and male composite distress and depression, and female anxiety gave an area under the curve (AUC) and 95% confidence interval (shown in brackets) of 0.866 (0.5-1;

Figure 2A), 0.493 (0.127-0.757,

Figure 2B), 0.637 (0.101-0.93,

Figure 2C), 0.676 (0.1-0.936,

Figure 2D) and 0.88 (0.622-1,

Figure 2E), respectively. The ROC curve for both the female composite and anxiety show relatively good group classification.

3.3. Pathway Analysis Reveals Sex Differences in the Metabolic Response to Distress

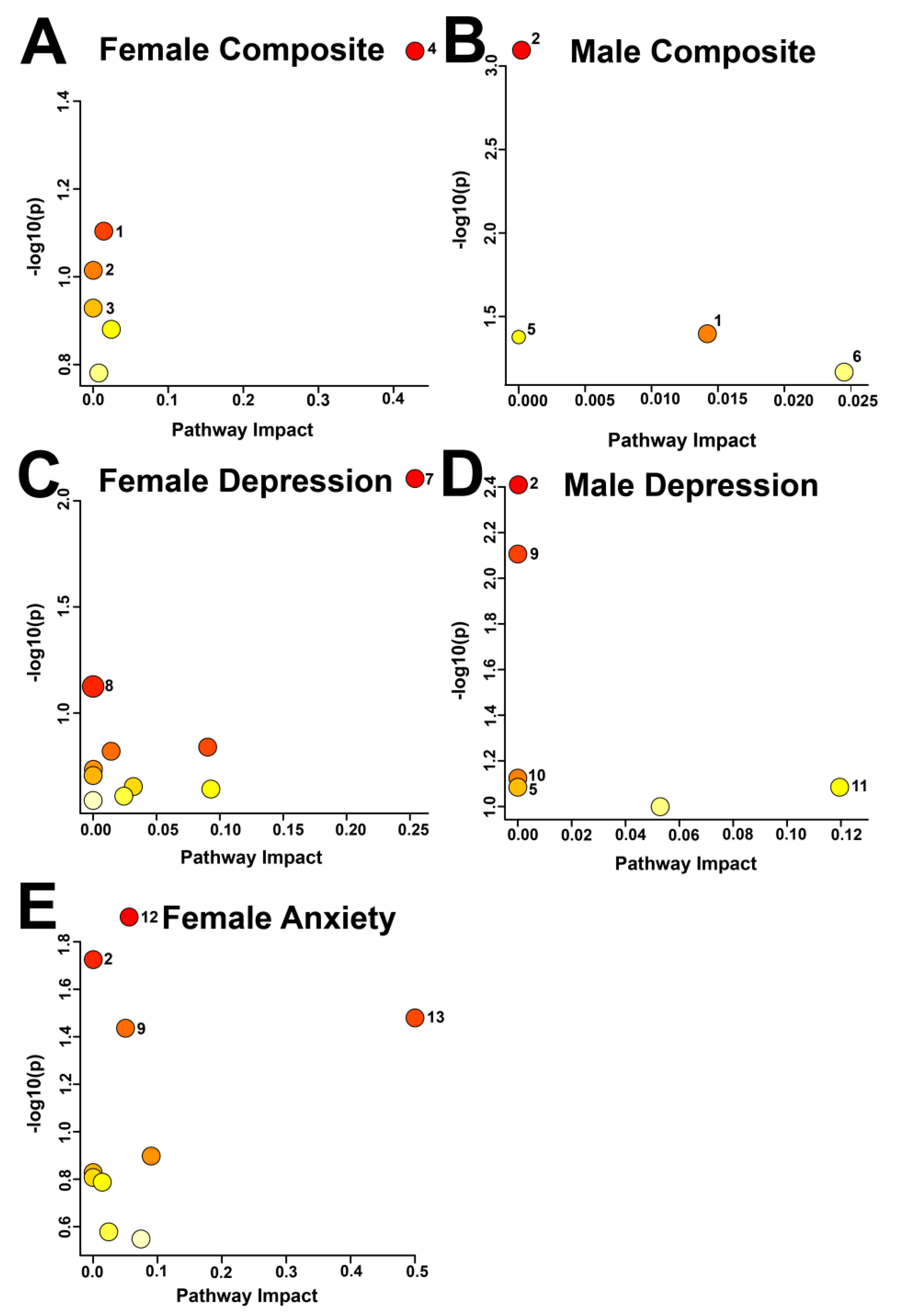

Metabolic pathway topology analysis identified 13 pathways that were potentially impacted across the different comparison groups (

Figure 3,

Table 2), based on an α-threshold of 0.1. In the female composite distress comparison, the potentially impacted pathways were taurine and hypotaurine metabolism, followed by sphingolipid metabolism and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. In the male composite distress comparison, glycerophospholipid metabolism, sphingolipid metabolism, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis were potentially altered.

In the female anxiety comparison, the following four pathways were potentially altered: glycolysis/gluconeogenesis; amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism; beta-alanine metabolism; and riboflavin metabolism. The male depression comparison indicated glycolysis/gluconeogenesis and the pentose phosphate pathways may have been impacted. Terpenoid backbone biosynthesis and caffeine metabolism were the only potentially impacted pathways in the female depression comparison.

4. Discussion

By combining objective biological indicators with insights from lived experience, the present study offers comprehensive understanding of mental well-being in individuals affected by forced displacement and trauma. The novelty of this study is the identification of sex-specific salivary biomarkers as robust indicators of mental wellbeing among Syrian refugees. The study adopted standardized questionnaires and a new composite score as indicators of mental distress in Syrian refugees along with a metabolomics approach via 1H NMR spectroscopy. The present OPLS-DA models demonstrated differences of salivary metabolic profiles, with good group classification being observed for anxiety and composite score among females and some classification observed for depression among males. In total, 63 out of 332 bins were labelled as containing significant metabolic differences through multivariate and univariate analysis. 31 unique metabolites were identified from the 63 bins during metabolite identification. These results suggest that salivary metabolic profiles may provide an objective supplementary method to aid in the diagnosis of anxiety and depression in particularly vulnerable populations.

Many of the identified metabolites and their associated pathways are interrelated, which may be explained by the observation that depression and anxiety are often comorbid and share common risk factors, such as psychological distress [

50,

51,

52]. By contrast, some of the identified pathways also enhance further understanding of the disparity between depression and anxiety. Although it is unlikely that the study of metabolites alone would be sufficient to predict the complex phenotype of distress vulnerability, including transition from at-risk states to clinically diagnosable mental disorders [

27,

53], the present results suggest certain metabolites that may contribute to the pathogenesis or symptomatology of depression and anxiety to guide future research.

4.1. Energy Metabolism and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

The present findings indicate that metabolites found in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis were the most frequently disrupted, expressing differences in the metabolomes between high and low distress across all comparisons. Glucose concentrations were lower in males with depression and higher in females with anxiety. Previous studies have shown that lower glucose levels are related to increased brain activity, as glucose is the main source of energy for neurochemical processes [

54,

55,

56]. As the brain consumes a quarter of total body glucose, critically low levels of circulating glucose may underlie a jeopardized energy metabolism in patients with major depressive disorder [

57]. By contrast, higher availability of glucose in females may reflect an altered brain energy metabolism, as suggested by experimental findings in mice with elevated anxiety-like behaviours [

57,

58]. Chronically perturbed glucose concentrations may damage mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA, generating by-products that promote systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and accelerate cellular aging [

8,

59]. In cases of metabolic dysfunction or neuroinflammation, glucose may accumulate if utilization is impaired. A combination of altered glucose regulation and mitochondrial dysregulation may induce deficient energy utilization in times of higher energy demand, as previously observed in females with anxiety [

58].

Components of mitochondrial dysfunction and inflammation may play a role in depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders [

8,

60,

61,

62]. Brain tissue has a high energy demand for maintenance of transmembrane potentials, signal transduction, and synaptic plasticity. Gardner and Boles suggested several pathophysiological mechanisms underlying mitochondrial function in major depression [

60]. Mitochondria play a pivotal role in cellular energy metabolism, neuronal amino-acid, lipid, and steroid metabolism, modulation of cellular calcium levels, and the regulation of apoptosis [

63,

64,

65]. It was suggested that impaired mitochondrial function might lead to disrupted neural plasticity and reduced cellular resilience, which may promote the development and progression of mood disorders [

62]. The disturbance of the energy supply to the mitochondria, either as a cause or consequence of depression, may contribute to the pathophysiology of depressive symptoms [

61].

Lactate is generally regarded as an indicator for the adaptive response of energy failure. Hence, the reduced lactate levels in male participants may reflect the energy supply/demand imbalance that potentially accompanies their depression [

66,

67]. In humans, aerobic glycolysis takes place in oxygen-rich cellular environments, whereas anaerobic glycolysis occurs during a lack of available oxygen, reducing pyruvate to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase [

68]. Glial cells, using the lactate shuttle, are responsible for transforming glucose into lactate and providing it to neurons. These observations support the finding of reduced glucose availability and corresponding decrease in lactate levels in males with depression.

4.2. Sphingolipid and Glycerophospholipid Metabolism

Sphingolipids and glycerophospholipids are the most common lipids in brain membranes and have a larger role in neuronal activity, cellular signaling [

69,

70], signal transduction, cell growth, cell death [

71], and disease pathologies [

72,

73]. O-Phosphoethanolamine, which had altered concentration in both the male and female composite comparisons, is an important precursor to the glycerophospholipid phosphatidylethanolamine. In the CDP-ethanolamine pathway the enzyme ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase converts phosphoethanolamine into CDP- ethanolamine, which is then subsequently converted to phosphatidylethanolamine by ethanolamine phosphotransferase [

74,

75]. Previous studies focusing on peripheral lipid metabolism in depressive patients have found an increase in activity compared to controls [

51]. Levels of lipids and their associated enzymes can account for severity of depression and measure the success of potential treatments [

76]. Further work has shown a correlation between sphingolipids and inflammatory processes within the brain, involving either lipid cleavage or lipid turnover [

71]. Moreover, clinically effective antidepressants inhibit sphingolipid production in the hippocampus, which may be essential for their therapeutic efficacy. Accordingly, membrane-forming lipids have high potential in the treatment of anxiety disorders [

51]. Therefore, lipid-based therapies may offer personalized treatment, such as targeted dietary supplementation of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [

77], or pharmacological interference of lipids, such as glycerolipids, with lipid-regulating enzymes [

72,

78].

4.3. Taurine/Hypotaurine Metabolism

Taurine was highly upregulated in the female composite distress comparison, and taurine and hypotaurine metabolism emerged as the most significantly altered pathway, showing both the largest pathway impact and the lowest p-value. Taurine is an abundant central amino acid involved in synaptic inhibition and has been shown to increase significantly under stressful conditions [

79], suggesting a critical role in neuroprotection [

80]. It also acts as an inhibitory neuromodulator with known antianxiety properties [

81] and may mitigate glutamate-induced mitochondrial damage and neuronal cell death by regulating intracellular calcium levels. In addition, taurine contributes to several key neurophysiological processes, including osmotic balance, membrane stabilization, detoxification, and neuromodulation [

82]. These findings point to taurine as a potentially sex-specific neuroprotective metabolite that may buffer the effects of stress particularly in females.

4.4. Sex Differences

Sex differences usually are highly associated with a discriminatory metabolite signature in healthy humans and therefore should be considered in metabolomics studies using both male and female participants [

83,

84]. Overall, the current findings indicate that females had greater metabolic discrepancy in relation to mental distress severity than males, suggested by the statistical significance portrayed in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. This does not indicate that females were more emotionally influenced by psychiatric distress than males, but rather, females generally showed greater variation in metabolites representing mental distress severity through a salivary

1H-NMR-based technique from a metabolic perspective, especially when investigating the discrepancy of a composite stress score and anxiety. Earlier investigations of sex differences in metabolites indicated that sex-specific patterns may be correlated to the effects of sex hormones, as sex differences emerge during reproductive years and gradually decline after menopause [

85]. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating sex-specific analyses in metabolomic research on mental health, particularly in marginalized and vulnerable populations, as they reveal underlying biological variation that may inform more precise, personalized approaches to diagnosing and managing psychiatric distress and trauma.

4.5. Limitations

The present study offers novel insights into the mechanistic pathways underlying mental health and vulnerability to distress. Nevertheless, the relatively small sample size highlights the need for further investigation before any clinical applications can be considered. While psychometric questionnaires are commonly used to assess mental health, they have inherent limitations, as some scales may not fully capture the heterogeneity and complexity of psychiatric conditions in clinical presentation [

50]. Incomplete assessments of symptoms in this study may have limited statistical power and reduced the ability to more thoroughly explore sex-specific metabolic signature. Future studies should incorporate larger, more diverse cohorts to enhance statistical robustness and better capture the influence of sex, gender, and other sociodemographic variables on metabolic profiles. Incorporating linear regression models that control for socioeconomic status, cultural background, and health disparities would also increase the generalizability and equity relevance of the findings. Additionally, the cross-sectional design precludes longitudinal within-subject analyses, which are necessary to account for dynamic changes due to circadian rhythms, lifestyle, and nutrition. Finally, while saliva provides a practical, non-invasive sampling method, its composition reflects a filtered subset of blood metabolites, often at different concentrations [

40,

86]. Thus, complementary

1H NMR spectroscopy using blood samples may offer greater sensitivity and resolution in detecting subtle metabolic signatures associated with mental distress and resilience.

5. Conclusions

The present univariate and multivariate analyses revealed characteristic salivary metabolic “fingerprints” indicative of adverse mental health outcomes. Several significantly altered metabolites may serve as potential sex-specific salivary biomarkers for depression and anxiety. Pathways related to energy metabolism were most affected by mental distress, alongside notable changes in sphingolipid and taurine/hypotaurine metabolism. These findings suggest that ¹H NMR spectroscopy-based metabolomics offers a promising, non-invasive approach for innovative, complementary mental health and distress screening using easily accessible saliva samples. The observed metabolic signatures may provide an objective tool to aid in the diagnosis of depression and anxiety in vulnerable populations, enabling rapid screening and the delivery of targeted, personalized interventions to those at highest risk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: P-values of salivary metabolites found to be significant in comparisons tested in either the Mann-Whitney U test, or Variable Importance Analysis based on random Variable Combination (VIAVC). Metabolites for which more than one NMR resonance peak was identified as significant are represented as metabolite.1, metabolite.2, … metabolite.n. † Indicates metabolites that were present in two or more similar sex comparisons while ‡ indicates metabolites that were present in both sexes and/or multiple comparisons.

Author Contributions

T.H., T.M. and G.M. conceptualized and designed the study and supervised all personnel working on the project. T.H. recruited participants, collected samples, and carried out survey data collection. S.M., T.H, and L.K. processed all samples, collected metabolomics data, and carried out the data analysis. All authors contributed to writing and editing of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Scheme Grant # 363195 (G.M.) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Discovery Grant #05519 (G.M.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the University of Lethbridge Human Participant Research Committee (protocol number 2019-065, approved July 7, 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study have not been uploaded to an onlne database accessible to the public due to privacy restrictions. However, the corresponding authors will make the data available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors are extremely grateful to all the participants who took part in this study. The authors acknowledge the incredible support of Nickolej Villiger and Lethbridge Family Services -Immigrant Services in allowing us to use their facility and support participants during the process of data collection. The authors greatly appreciate the assistance of Hadil Karem and Abdullah Mouslli for Arabic translations and participant recruitment, Amelia Greeno for her work as team phlebotomist, and Andrea Slingerland and Nicole Hautala for their assistance throughout the project. The authors also acknowledge the assistance and expertise of Michael Opyr in coding some of the MATLAB scripts used for data analysis, as well as Michael Gale, Joshua Heynen, Jamie Petersson, and Ben Wright, for training and directing the undergraduate students affiliated with the project. In addition, we thank the University of Lethbridge for the use of the Magnetic Resonance Facility, which provided access to and training on the NMR spectrometer. This research was also supported by Safeway Ltd., London Drugs Ltd., and Lethbridge Family Services - Immigrant Services.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Figures at a Glance (2020). Available online at http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html.

- Akgul, S., Husnu, S., Derman, O., Ozmert, E. N., Bideci, A., & Hasanoglu, E. (2019). Mental health of Syrian refugee adolescents: How far have we come? Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 61(6), 839-845. [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, E., Zbidat, A., Schmitt, G. M., & Erim, Y. (2018). Prevalence of Mental Distress Among Syrian Refugees With Residence Permission in Germany: A Registry-Based Study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(393). [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., Khabbaz, F., & Legate, N. (2016). Regulatory focus, coping strategies and symptoms of anxiety and depression: A comparison between Syrian refugees in Turkey and Germany. PloS One, 13(10). [CrossRef]

- Government of Canada, S. C. (2019, February 12). Study: Syrian refugees who resettled in Canada in 2015 and 2016. The Daily. Retrieved November 29, 2021, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190212/dq190212a-eng.htm.

- Peconga, E. K., & Høgh Thøgersen, M. (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety in adult Syrian refugees: What do we know? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48(7), 677-687. [CrossRef]

- Borho, A., Viazminsky, A., Morawa, E., Schmitt, G. M., Georgiadou, E., Erim, Y. (2020). The prevalence and risk factors for mental distress among Syrian refugees in Germany: a register-based follow-up study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 362. [CrossRef]

- Mellon, S. H., Gautam, A., Hammamieh, R., Jett, M., & Wolkowitz, O. M. (2018). Metabolism, Metabolomics, and Inflammation in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 83(10), 866-875. [CrossRef]

- Mellon, S. H., Bersani, F. S., Lindqvist, D., Hammamieh, R., Donohue, D., Dean, K., Jett, M., Yehuda, R., Flory, J., Reus, V. I., Bierer, L. M., Makotkine, I., Abu Amara, D., Henn Haase, C., Coy, M., Iiidoyle, F. J., Marmar, C., & Wolkowitz, O. M. (2019). Metabolomic analysis of male combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. PLoS ONE, 14(3), 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Stromme, E. M., Haj-Younes, J., Hasha, W., Fadnes L.T., Kumar, B., & Diaz, E. (2019). Chronic pain and migration-related factors among Syrian refugees: a cross-sectional study. European Journal of Public Health. Volume 29 (4). https://doi-org.ezproxy.uleth.ca/10.1093/eurpub/ckz185.422.

- Sareen, J., Cox, B. J., Stein, M. B., Afifi, T. O., Fleet, C., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007). Physical and mental comorbidity, disability, and suicidal behavior associated with posttraumatic stress disorder in a large community sample. Psychosomatic medicine.

- Grupp, F., Piskernik, B., & Mewes, R. (2020). Is depression comparable between asylum seekers and native Germans? An investigation of measurement invariance of the PHQ-9. Journal of affective disorders, 262, 451-458. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine, 16(9), 606-613. [CrossRef]

- Martin, A., Rief, W., Klaiberg, A., & Braehler, E. (2006). Validity of the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire Mood Scale (PHQ-9) in the general population. General Hospital Psychiatry, 28(1), 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Löwe, B., Decker, O., Müller, S., Brähler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., & Herzberg, P. Y. (2008). Validation and Standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the General Population. Medical care, 46(3), 266-274. [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092. [CrossRef]

- Niciu, M. J., Mathews, D. C., Nugent, A. C., Ionescu, D. F., Furey, M. L., Richards, E. M., Machado-Vieira, R., & Zarate, C. A. (2014). Developing Biomarkers in Mood Disorders Research Through the Use of Rapid-Acting Antidepressants. Depression & Anxiety (1091-4269), 31(4), 297-307. [CrossRef]

- Ambeskovic, A., Hopkins, G., Hoover, T., Joseph, J. T., Montina, T., & Metz, G. (2023). Metabolomic signatures of Alzheimer’s disease indicate brain region-specific neurodegenerative progression. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24, 14769.

- Heynen, J. P., Paxman, E. J., Sanghavi, S., McCreary, J. K., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2022). Trans- and multigenerational social isolation stress programs the blood plasma metabolome in the F3 generation. Metabolites, 12, 572.

- Heynen, J. P., McHugh, R. R., Boora, N. S., Simcock, G., Kildea, S., Austin, M. P., Laplante, D. P., King, S., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2023). Urinary 1H NMR metabolomic analysis of prenatal maternal stress due to a natural disaster reveals metabolic risk factors for non-communicable diseases: the QF2011 Queensland flood study. Metabolites, 13, 579.

- Kenney, T., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2025). Metabolomics as the missing piece in Epigenetics Research. Environmental Epigenetics, dvaf014. [CrossRef]

- Paxman, E. J. et al. (2018). Prenatal maternal stress from a natural disaster alters urinary metabolomic profiles in Project Ice Storm participants. Science Report, 8(12932).

- Stroud, J. E., Gale, M. S., Zwart, S. R., Heer, M., Smith, S. M., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2022). Longitudinal metabolomic profiles reveal sex-specific adjustments to long-duration spaceflight and return to earth. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, (79), 578.

- DeBerardinis, Ralph J., & Thompson, Craig B. (2012). Cellular Metabolism and Disease: What Do Metabolic Outliers Teach Us? Cell, 148(6), 1132-1144. [CrossRef]

- Emwas, A.-H., Salek, R., Griffin, J., & Merzaban, J. (2013). NMR-based metabolomics in human disease diagnosis: applications, limitations, and recommendations. Metabolomics, 9(5), 1048-1072. [CrossRef]

- Han, W., Sapkota, S., Camicioli, R., Dixon, R. A., & Li, L. (2017). Profiling novel metabolic biomarkers for Parkinson's disease using in-depth metabolomic analysis. Movement Disorders, 32(12), 1720-1728. [CrossRef]

- Pedrini, M., Cao, B., Nani, J. V. S., Cerqueira, R. O., Mansur, R. B., Tasic, L., Hayashi, M. A. F., McIntyre, R. S., & Brietzke, E. (2019). Advances and challenges in development of precision psychiatry through clinical metabolomics on mood and psychotic disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 93, 182-188. [CrossRef]

- Wanner, Z. R., Southam, C. G., Sanghavi, P., Boora, N. S., Paxman, E. J., Dukelow, S. P., Benson, B. W., Montina, T., Metz, G. A., & Debert, C. T. (2021). Alterations in urine metabolomics following sport-related concussion: A 1H NMR-based analysis. Frontiers in Neurology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Poplawski, J., Radmilovic, A., Montina, T. D., & Metz, G. A. (2020). Cardiorenal metabolic biomarkers link early life stress to risk of non-communicable diseases and Adverse Mental Health Outcomes. Scientific Reports, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Poplawski, J., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2024). Early life stress shifts critical periods and causes precocious visual cortex development. PLoS ONE, 19 (12), e0316384. [CrossRef]

- Bykowski, E. A., Petersson, J. N., Dukelow, S., Ho, C., Debert, C. T., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2021a). Urinary biomarkers indicative of recovery from Spinal Cord Injury: A pilot study. IBRO Neuroscience Reports, 10, 178–185. [CrossRef]

- Bykowski, E. A., Petersson, J. N., Dukelow, S., Ho, C., Debert, C. T., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2021b). Urinary metabolomic signatures as indicators of injury severity following traumatic brain injury: A pilot study. IBRO Neuroscience Reports. 11, 200-206.

- Bykowski, E. A., Petersson, J. N., Dukelow, S., Ho, C., Debert, C. T., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2023). Identification of serum metabolites as prognostic biomarkers following spinal cord injury: A pilot study. Metabolites. 13, 605.

- Bykowski, E. A., Petersson, J. N., Dukelow, S., Ho, C., Debert, C. T., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2024). Blood-derived metabolic signatures as biomarkers of injury severity in traumatic brain injury: A pilot study. Metabolites. 14, 105.

- Petersson, J. N., Bykowski, E. A., Ekstrand, C., Dukelow, S. P., Ho, C., Debert, C. T., Montina, T., & Metz, G. A. S. (2024). Unraveling metabolic changes following stroke: Insights from a urinary metabolomics analysis. Metabolites, 14, 145.

- Scott, H. D., Buchan, M., Chadwick, C., Field, C. J., Letourneau, N., Montina, T., Leung, B. M., & Metz, G. A. (2020). Metabolic dysfunction in pregnancy: Fingerprinting the maternal metabolome using Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Endocrinology, Diabetes & Metabolism, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Chiappin, S., Antonelli, G., Gatti, R., & De Palo, E. F. (2007). Saliva specimen: a new laboratory tool for diagnostic and basic investigation. Clinica Chimica Acta, 383(1–2), 30–40. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y., Kodama, H., Satoh, T., et al. (2010). Diurnal changes in salivary amino acid concentrations. Vivo, 24(6), 837–842.

- Silwood, C. J., Lynch, E., Claxson, A. W., & Grootveld, M. C. (2002). 1H and (13)C NMR spectroscopic analysis of human saliva. Journal of Dental Research, 81(6), 422–427.

- Dame, Z., Aziat, F., Mandal, R., Krishnamurthy, R., Bouatra, S., Borzouie, S., Guo, A., Sajed, T., Deng, L., Lin, H., Liu, P., Dong, E., & Wishart, D. (2015). The human saliva metabolome. Metabolomics, 11(6), 1864-1883. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.E., Mahle, D.A., Doom, T.E. et al. (2011). Dynamic adaptive binning: an improved quantification technique for NMR spectroscopic data. Metabolomics, 7(179). [CrossRef]

- Craig, A., Cloarec, O., Holmes, E., Nicholson, J. K., & Lindon, J. C. (2006). Scaling and Normalization Effects in NMR Spectroscopic Metabonomic Data Sets. Analytical Chemistry, 78(7), 2262-2267. [CrossRef]

- Goodpaster, A. M., Romick-Rosendale, L. E., & Kennedy, M. A. (2010). Statistical significance analysis of nuclear magnetic resonance-based metabonomics data. Analytical Biochemistry, 401(1), 134-143.

- Yun, Y. H., Liang, F., Deng, B. C. et al. (2015). Informative metabolites identification by variable importance analysis based on random variable combination. Metabolomics. 11, 1539–1551. [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, T. (2006). An Introduction to ROC Analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters, 27(8), 861-874. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, S., Johansson, E., Sjöström, L., Mellerowicz, E. J., Edlund, U., Shockcor, J. P., & Trygg, J. (2008). Visualization of GC/TOF-MS-Based Metabolomics Data for Identification of Biochemically Interesting Compounds Using OPLS Class Models. Analytical Chemistry, 80(1), 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z., Chong, J., Li, S., & Xia, J. (2020). MetaboAnalystR 3.0: Toward an optimized workflow for global metabolomics. Metabolites, 10(5), 186. [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D. S., Jewison, T., Guo, A. C., et al. (2013). HMDB 3.0–The human metabolome database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Research, 41, D801–D807. [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D. S., Feunang, Y. D., Marcu, A., Guo, A. C., Liang, K., Vázquez-Fresno, R., Sajed, T., Johnson, D., Li, C., Karu, N., Sayeeda, Z., Lo, E., Assempour, N., Berjanskii, M., Singhal, S., Arndt, D., Liang, Y., Badran, H., Grant, J., Serra-Cayuela, A., Liu, Y., Mandal, R., Neveu, V., Pon, A., Knox, C., Wilson, M., Manach, C., & Scalbert, A. (2018). HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46(D1):D608-D617. PMID: 29140435; PMCID: PMC5753273. [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J., & Charney, D. (2000). Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and anxiety, 12(S1), 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Müller, C. P., Reichel, M., Mühle, C., Rhein, C., Gulbins, E., & Kornhuber, J. (2015). Brain membrane lipids in major depression and anxiety disorders. BBA - Molecular & Cell Biology of Lipids, 1851(8), 1052-1065. [CrossRef]

- Nemeroff, C. B. (2002). Comorbidity of Mood and Anxiety Disorders: The Rule, Not the Exception? The American journal of psychiatry, 159(1), 3-4. [CrossRef]

- Gui, S. W., Liu, Y. Y., Zhong, X. G., Liu, X. Y., Zheng, P., Pu, J. C., Zhou, J., Chen, J. J., Zhao, L. B., Liu, L. X., Xu, G. W., & Xie, P. (2018). Plasma disturbance of phospholipid metabolism in major depressive disorder by integration of proteomics and metabolomics. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat.14:1451-1461. [CrossRef]

- Kanemaru, K., & Diksic, M. (2009). The Flinders Sensitive Line of rats, a rat model of depression, has elevated brain glucose utilization when compared to normal rats and the Flinders Resistant Line of rats. Neurochemistry international, 55(7), 655-661. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, S. H., Evans, K. R., Krüger, S., Mayberg, H. S., Meyer, J. H., McCann, S., Arifuzzman, A. I., Houle, S., & Vaccarino, F. J. (2001). Changes in Regional Brain Glucose Metabolism Measured With Positron Emission Tomography After Paroxetine Treatment of Major Depression. The American journal of psychiatry, 158(6), 899-905. [CrossRef]

- Xie, X., Shen, Q., Yu, C., Xiao, Q., Zhou, J., Xiong, Z., Li, Z., & Fu, Z. (2020). Depression-like behaviors are accompanied by disrupted mitochondrial energy metabolism in chronic corticosterone-induced mice. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, 200, N.PAG-N.PAG. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Filiou, M. D., Reckow, S., Gormanns, P., Maccarrone, G., & Kessler, M. S. (2011). Proteomic and metabolomic profiling of a trait anxiety mouse model implicate affected pathways. Mol Cell Proteomics,10. M111.008110.

- Filiou, M. D., Asara, J. M., Nussbaumer, M., Teplytska, L., Landgraf, R., & Turck, C. W. (2014). Behavioral extremes of trait anxiety in mice are characterized by distinct metabolic profiles. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 58, 115-122. [CrossRef]

- Kusminski, C. M. & Scherer, P. E. (2012). Mitochondrial dysfunction in white adipose tissue. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23:435–443.

- Gardner, A., & Boles, R. G. (2011). Beyond the serotonin hypothesis: Mitochondria, inflammation and neurodegeneration in major depression and affective spectrum disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 35(3), 730-743. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. W., Kelley, K. W., O'Connor, J. C., Dantzer, R., & Freund, G. G. (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 9(1), 46-56. [CrossRef]

- Manji, H., Kato, T., Di Prospero, N. A., Ness, S., Flint Beal, M., Krams, M., & Chen, G. (2012). Impaired mitochondrial function in psychiatric disorders. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 13(5), 293-307. [CrossRef]

- Gleichmann, M. & Mattson, M. P. (2011). Neuronal calcium homeostasis and dysregulation. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 14, 1261–1273.

- MacAskill, A. F., Atkin, T. A. & Kittler, J. T. (2010). Mitochondrial trafficking and the provision of energy and calcium buffering at excitatory synapses. Eur. J. Neurosci. 32, 231–240.

- Mattson, M. P., Gleichmann, M. & Cheng, A. (2008). Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron 60, 748–766.

- Valenza, F., Aletti, G., Fossali, T., Chevallard, G., Sacconi, F., Irace, M., & Gattinoni, L. (2005). Lactate as a marker of energy failure in critically ill patients: hypothesis. Critical care (London, England), 9(6), 588-593. [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Chen, C., Hou, L. J., Zhou, C. J., Fang, L., & Chen, J. J. (2020). Dual metabolomic platforms identified a novel urinary metabolite signature for Hepatitis B virus-infected patients with depression. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 13:1677–1683.17.

- Dashty, M. (2013). A quick look at biochemistry: Carbohydrate metabolism. Clinical Biochemistry, 46(15), 1339-1352. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S. N., Wang, H. Y. J., & Woods, A. S. (2005). Direct profiling of lipid distribution in brain tissue using MALDI-TOFMS, Analytical Chemistry, 77, 4523–4527.

- Jain, M., Ngoy, S., Sheth, S. A., Swanson, R. A., Rhee, E. P., Liao, R., Clish, C. B., Mootha, V. K., & Nilsson, R. (2014). A systematic survey of lipids across mouse tissues, Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 306, E854–E868.

- Rao, R. P., Vaidyanathan, N., Rengasamy, M., Oommen, A. M., Somaiya, N., & Jagannath, M. R. (2013). Sphingolipid Metabolic Pathway: An Overview of Major Roles Played in Human Diseases. Journal of Lipids, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Humer, E., Pieh, C., & Probst, T. (2020). Metabolomic Biomarkers in Anxiety Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(13), 4784-4784. [CrossRef]

- Tracey, T. J.; Steyn, F. J.; Wolvetang, E. J.; & Ngo, S. T. (2018). Neuronal lipid metabolism: Multiple pathways driving functional outcomes in health and disease. Frontiers of Molecular Neuroscience. 11, 10.

- Farooqui, A. A., Horrocks, L. A., Farooqui, T. (2000). Glycerophospholipids in brain: their metabolism, incorporation into membranes, functions, and involvement in neurological disorders. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids, 106, 1-29.

- Lykidis, A., Wang, J., Karim, M. A., & Jackowski, S. (2001). Overexpression of a mammalian ethanolamine-specific kinase accelerates the CDP-ethanolamine pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(3), 2174–2179. [CrossRef]

- Buttgereit, F., Burmester, G. R., & Brand, M. D. (2000). Bioenergetics of immune functions: fundamental and therapeutic aspects. Immunology Today, 21(4), 194–199. [CrossRef]

- Su, K. P., Tseng, P. T., Lin, P.-Y., Okubo, R., Chen, T. Y., Chen, Y. W., & Matsuoka, Y. J. (2018). Association of use of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids with changes in severity of anxiety symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama Netw. 1, e182327.

- Hozumi, Y. & Goto, K. (2012). Diacylglycerol kinase β in neurons: Functional implications at the synapse and in disease. Adv. Biol. Regul. 52, 315–325.

- Wu, J. Y., Tang, X. W., Schloss, J. V., & Faiman, M. D. (1998). Regulation of taurine biosynthesis and its physiological significance in the brain. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 442, 339.

- Chung, Y. C. E., Chen, H. C., Chou, H. C. L., Chen, I. M., Lee, M. S., Chuang, L. C., Liu, Y. W., Lu, M. L., Chen, C. H., Wu, C. S., Huang, M. C., Liao, S. C., Ni, Y. H., Lai, M. S., Shih, W. L., & Kuo, P. H. (2019). Exploration of microbiota targets for major depressive disorder and mood related traits. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 111, 74-82. [CrossRef]

- Rainesalo, S., Keranen, T., Palmio, J., Peltola, J., Oja, S. S., & Saransaari, P. (2004). Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid amino acids in epileptic patients. Neurochem Res., (1):319-24.

- Wright C. E., & Gaull G. E. (1988). Role of Taurine in Brain Development and Vision. In: Huether G. Amino Acid Availability and Brain Function in Health and Disease. NATO ASI Series (Series H: Cell Biology), vol 20. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Rist, M. J., Roth, A., Frommherz, L., Weinert, C. H., Krüger, R., Merz, B., Bunzel, D., Mack, C., Egert, B., Bub, A., Görling, B., Tzvetkova, P., Luy, B., Hoffmann, I., Kulling, S. E., & Watzl, B. (2017). Metabolite patterns predicting sex and age in participants of the Karlsruhe Metabolomics and Nutrition (KarMeN) study. PLoS ONE, 12(8). [CrossRef]

- Ruoppolo, M., Scolamiero, E., Caterino, M., Mirisola, V., Franconi, F., & Campesi, I. (2015). Female and male human babies have distinct blood metabolomic patterns. Molecular bioSystems, 11(9), 2483-2492. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R., Balhara, Y. P. S., & Gupta, C. S. (2011). Gender differences in stress response: Role of developmental and biological determinants. Industrial psychiatry journal, 20(1), 4-10. [CrossRef]

- Takeda, I., Stretch, C., Barnaby, P., et al. (2009). Understanding the human salivary metabolome. NMR in Biomedicine, 22(6), 577–584. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).