1. Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is among the leading causes of cancer-related deaths around the world, with the 5-year survival rate generally less than 10% [

1,

2]. Only a small portion of patients (<20%) are candidates for radical surgery with R0 margin that can significantly prolong survival, as the tumour is typically diagnosed at an advanced stage. An estimated 30–40% of patients with pancreatic cancer are presented in a locally advanced stage at the time of diagnosis [

3].

Successful stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT, also called stereotactic ablative radiotherapy, SABR) of pancreatic lesions leads to better local control (LC), but requires the application of very high Biologically Effective Doses (BED) (≥ 100 Gy), and a significant positive impact of LC on overall survival (OS) has been shown [

4,

5,

6]. The tumour lesion and surrounding healthy tissues are subject to significant physiological movements, with vast majority of the movements caused by respiration, and this is most evident in regions close to the diaphragm – the lung bases and upper-abdomen [

7,

8]. Monitoring tumour respiratory movements in free breathing (FB) using 4D CT and compensating them with expanded Internal Tumour Volume (ITV) is widely used approach, but it can limit the possibilities of applying the above-mentioned ablative doses, reducing the effectiveness of SBRT [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Respiratory mitigation using abdominal compression, respiratory gating, and fiducial-based intrafractional motion tracking (typically with robotic arm-based linacs) are also used as motion management for patients in FB. Voluntary breath hold (BH) in inhale or exhale phase significantly reduces respiratory movements and is most often used with surface guidance or intrafractional tracking with cine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). It is very effective and favourable in terms of dose distribution, but requires strict patient cooperation, is not completely reproducible, and significantly prolongs the duration of SBRT [

9,

13,

14].

At Specialty Hospital Radiochirurgia Zagreb, from April 2017 to September 2022, we were using Calypso Tracking System (Varian Medical Systems) as intrafractional fiducial-based tumour motion tracking for upper-abdominal tumours, mainly for locally advanced pancreatic cancer (LAPC) [

15]. We considered Calypso (when applicable) as probably the best intrafractional motion management during SBRT [[16]. However, in 2022. Varian Medical Systems [

17] announced that they will no longer be supporting Calypso tracking system from 2024. onwards and will not be producing new fiducials, and we had to adapt our methodology to the phase out of technology.

We came up with a new approach - SBRT for upper abdominal lesions (including LAPC) in Total Intravenous Anaesthesia (TIVA) with Assist-Control Mechanical Ventilation (ACMV) combined with AlignRT (Vision RT, London, UK) optical surface guidance (OSG) system as intrafractional motion management. Using TIVA with ACMV to control patients’ BH (what we named “TIVA controlled BH”), respiratory movements were almost completely eliminated and bowel movements were widely reduced. Consequently, the tumour target became almost motionless. Under these conditions, the clinical target volume-planning target volume (CTV-PTV) margins were reduced down to 2 mm, thus enabling high precision and safety of ablative dose delivery to the tumour, with excellent protection of surrounding organs at risk (OAR). We started performing SBRT in TIVA controlled BH in October 2022. Using this technique, we managed to apply prescribed doses up to 35 Gy (BED10 = 157.5 Gy) in a single-fraction to the pancreatic tumour.

This paper intends to present TIVA controlled BH with OSG as intrafractional motion management technique during single-fraction SBRT for LAPC, and preliminary clinical results (LC, OS and toxicity), aiming to show at least non-inferiority of this approach compared to Calypso. To our best knowledge, there are no published data on the usage of TIVA with ACMV combined with OSG as an intrafractional motion management system during SBRT for LAPC, although some experiences on using total endotracheal anaesthesia during SBRT were reported. This motion management technique during SBRT can be used for other upper abdominal lesions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

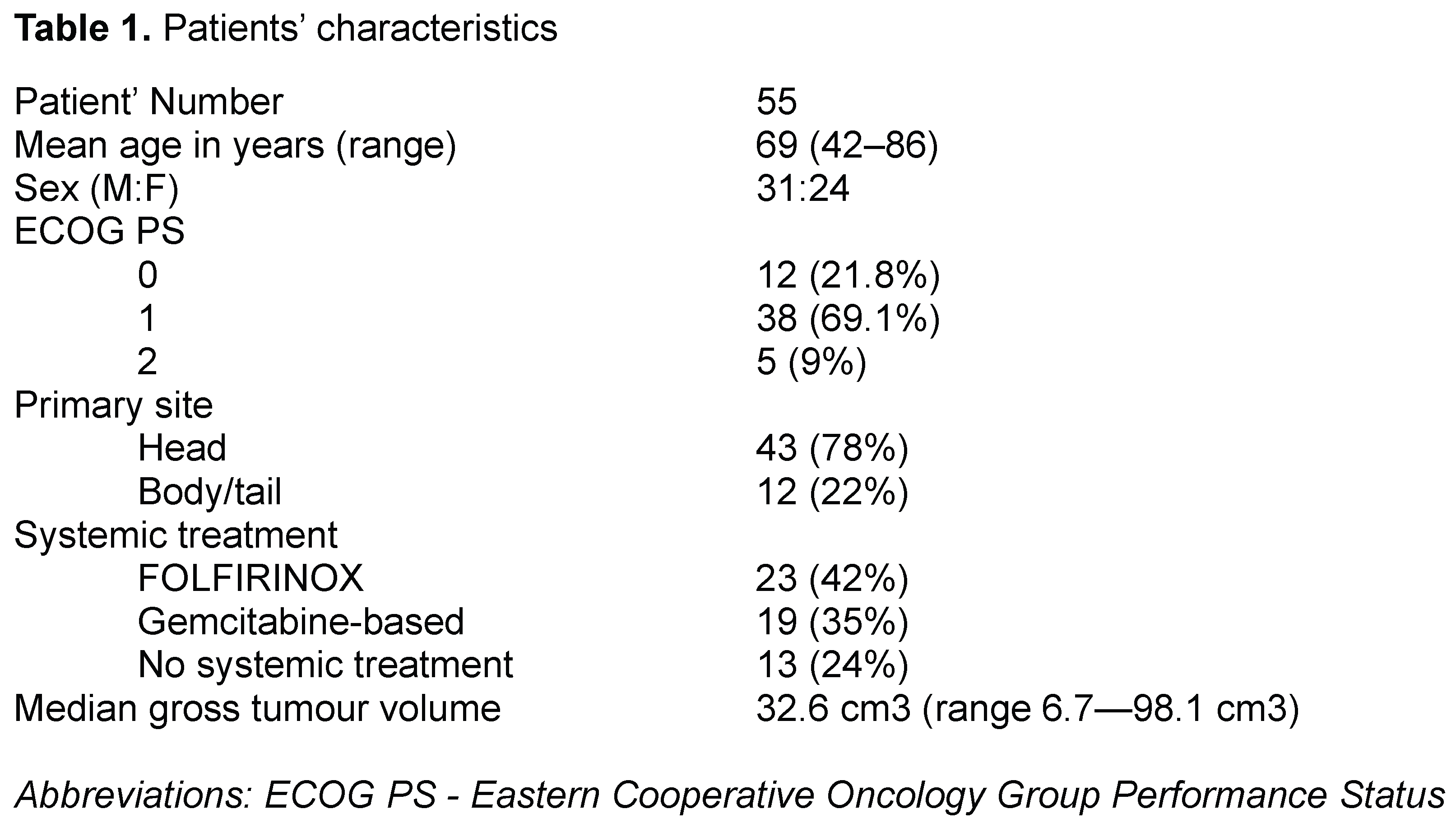

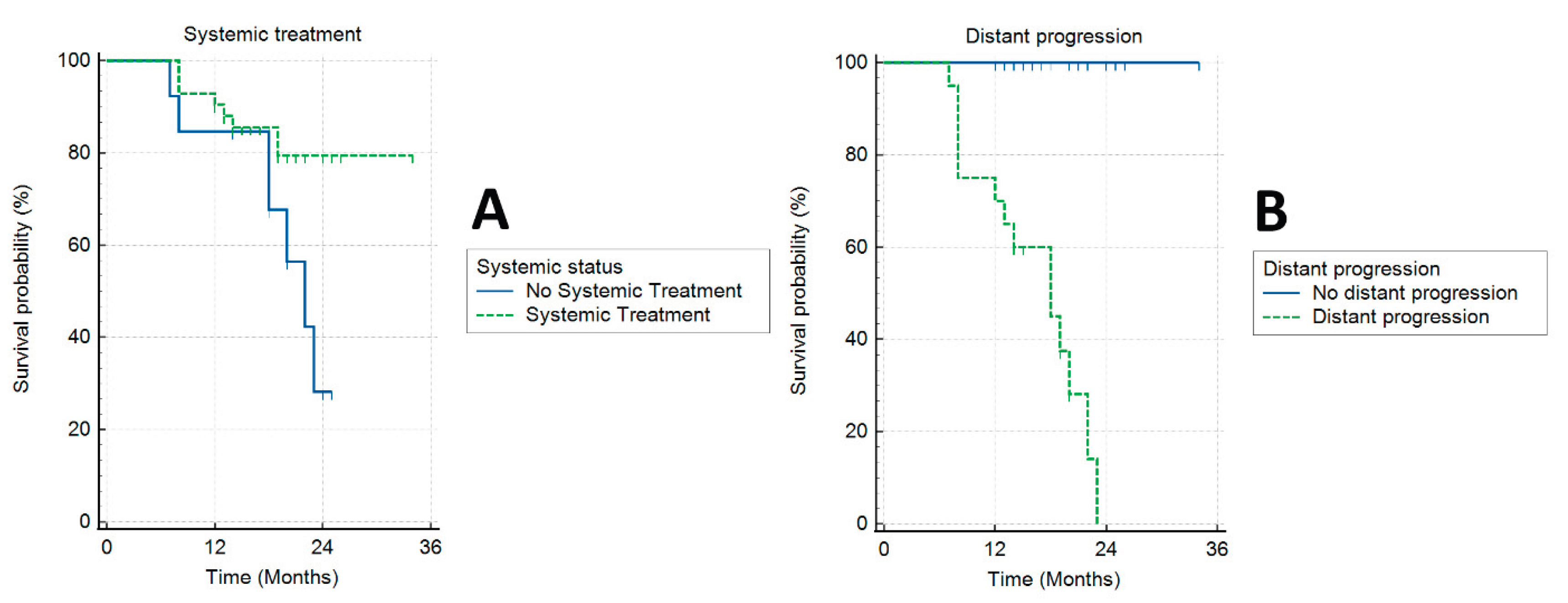

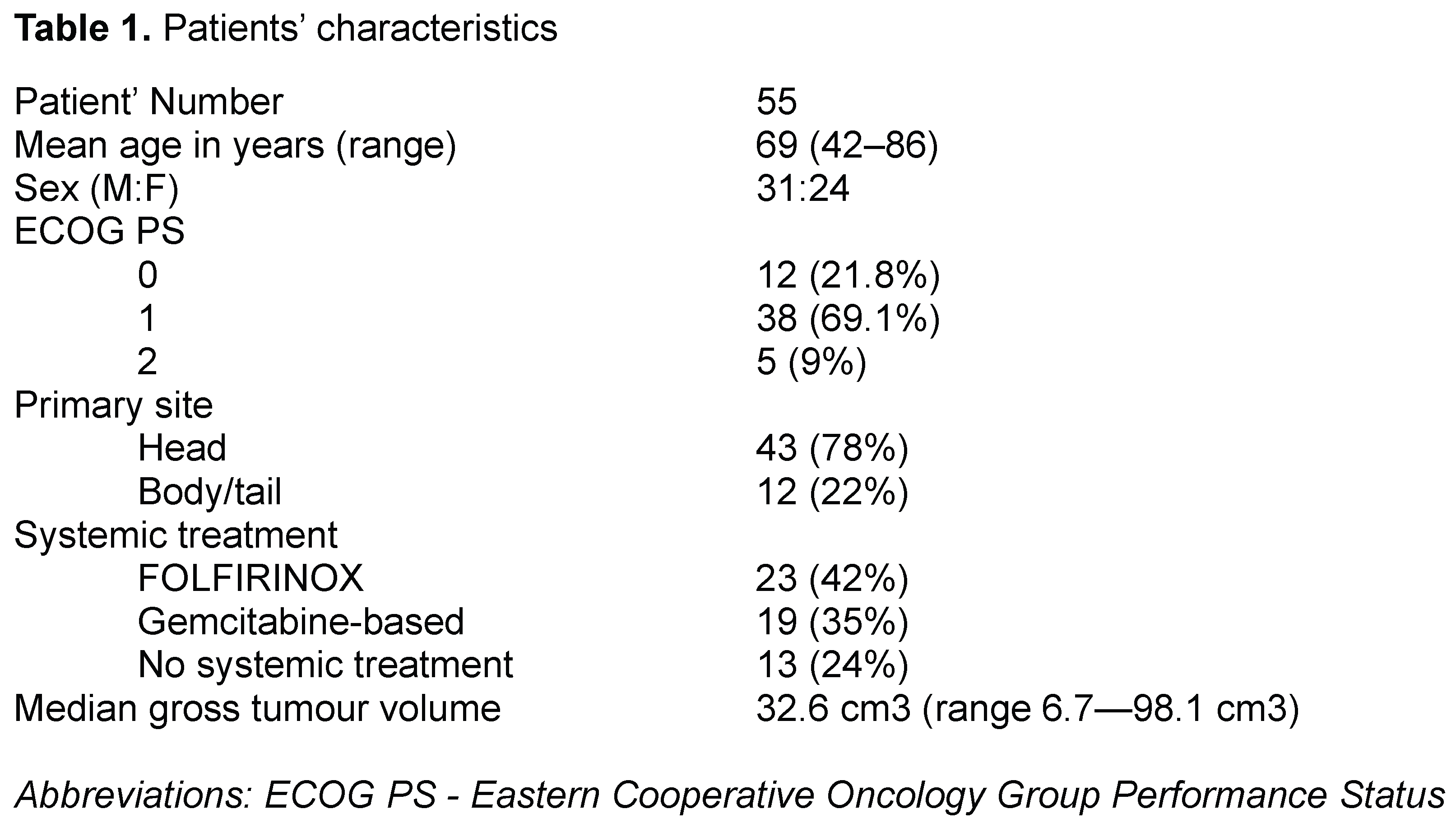

Medical data of 55 patients diagnosed with LAPC, treated between December/2022 and June/2024 and regularly followed up in our institution, were analysed and enrolled in this retrospective, single-arm, and single-institution experimental study, approved by the institutional Ethics Committee. Patients’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

All medical procedures in our study were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, also meeting comparable international and national ethical standards. All patients involved in the study signed informed consent. Our institution’s multidisciplinary team (MDT), consisting of radiation oncologists, pancreatic/biliary surgeons, radiologists, medical physicists, and medical oncologists, discussed and approved all patients for SBRT. Inclusion criteria were: unresectable, histologically proven pancreatic adenocarcinoma; ECOG 0–2; age ≥ 18; no signs of regional or distant metastasis and gastric or duodenal obstruction on diagnostic imaging; no previous abdominal radiotherapy.

The recommendations from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines and American Hepato–Pancreato–Biliary Association/Society of surgical Oncology/Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract were followed to define unresectable pancreatic cancer [

6,

18]. Multi-Slice Computed Tomography (MSCT) pancreas protocol was performed for each patient, and 3T MRI of the abdomen and/or Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) were added as needed. Each patient was examined by our anaesthesiologist and radiation oncologist for final approval.

Forty-two patients (76.4%) received systemic treatment. Thirty-five patients (83.3%) started the systemic treatment after SBRT and 7 patients (16.7%) started the systemic treatment (2 cycles) before SBRT and continued after SBRT. To avoid possible toxicities of concurrent application, systemic therapy was held at least one week before and after SBRT.

2.2. Patients’ Preparations for the Treatment (Title - Impossible to Revise)

We provided all patients with written recommendations on diet and medications - proton pump inhibitors and antiflatulent drugs - to reduce flatulence and weight loss, in order to minimize unwanted daily anatomical variations. The time from the planning to the start of the treatment was 7 - 10 days.

2.3. Total Intravenous Anaesthesia with Assist-Control Mechanical Ventilation

The anaesthesiologic assessment included a clinical examination of the patient, a review of patient’s medical documentation with special attention to comorbidities, and a review of the patient’s laboratory findings. Patients with heart and/or lung disease history had to have a recent examination by a cardiologist (heart ultrasound included), and/or a pulmonologist (spirometry included).

Absolute contraindications for TIVA with ACMV were: recent myocardial infarction, ejection fraction below 40%, cardiac failure, uncontrolled hypertension, and cardiac rhythm disturbance with hemodynamic repercussions, severe pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary fibrosis, severe obstructive-restrictive ventilation disorders, and pleural effusion. All patients were ASA II or ASA III according to the American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) classification.

Patient preparation before anaesthesia for planning and SBRT was the same for all patients. The patients were hospitalized on the day of planning and treatment. If additional treatment (e.g. monitoring, correction and optimization of vital functions, volume replacement, and achieving euglycemia and electrolyte balance) was needed, the patients were hospitalized the day before.

Thirty minutes after preparation and premedication, i.e. gastroprotection and sedation (pantoprazole, metoclopramide and midazolam per os), patients were transferred to the operating room and placed on TIVA. Procedure started with patient preoxygenation. The medications used for induction and maintenance of anaesthesia were: midazolam and propofol for sedation and hypnosis, sufentanyl for analgesia and rocurronium for muscle relaxation, in the prescribed dose per kilogram of body weight.

Supraglottic device I-Gel (Intersurgical L.T.D.) was placed to establish the airway [

19]. In cases of inability to place the I-Gel or excessive "air leakage", the patient was intubated.

Patients were ventilated with volume control ventilation - tidal volume of 6 ml/kg body weight. The selected ventilation modality was applied for both planning and SBRT.

Intraprocedural monitoring consisted of electrocardiogram, non-invasive blood pressure (NIPB), oxygenation saturation (SpO2) and end-tidal CO2 monitoring. During SBRT, NIBP monitoring was substituted with invasive arterial pressure (IBP) monitoring. The duration of the SBRT procedure makes NIBP unsuitable, as NIBP does not have the temporal resolution that IBP has. The need for accurate monitoring of respiratory manoeuvres’ effects on hemodynamics justified the invasiveness of the IBP placement.

After induction of anaesthesia and airway clearance, the patients were transferred to MSCT device for planning or to linac for SBRT treatment, as needed. At the time of planning or SBRT, the selected controlled ventilation modality was terminated using an “expiratory” BH for 30 seconds on average, alternating with preset ventilation. The manoeuvre was repeated as necessary. Blood gases were taken during the SBRT procedure, after induction and immediately after the procedure was completed. This primarily served to monitor the changes in partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arterial blood caused by ventilation interruptions.

Upon completion of procedure (planning or SBRT), awake, spontaneously breathing and hemodynamically stable patient was brought back to the department for continued recovery with monitoring of vital functions (heart rate, NIBP, SpO2). After an average two-hour stay in the department, the patients were discharged home.

2.4. Optical Surface Guidance

AlignRT (Vision RT, London, UK) monitoring system was used for OSG, combined with cone beam CT (CBCT) for image guidance (IG) [

20]. Two systems were used both for patient positioning and motion tracking. According to the manufacturer’s specifications, AlignRT system tracks any movements of the body contour in real time with a frequency of 5–10 Hz, a lag time < 100 milliseconds, and submillimetre accuracy.

The patient’s body contour on planning MSCT was defined as the default body contour (DBC), and region of interest (ROI) was specified as a segment of patient’s skin above the PTV. Anatomical position of the tumour on the planning MSCT was the therapeutic position.

AlignRT was used as “on-off” gating management during the treatment, monitoring the alignment of a ROI of DBC with patient’s body contour ROI on the treatment table. Gating windows allowed for a tolerable mismatch of ROIs in any direction within the 2 mm. As long as ROIs were aligned within the stated gating windows, the beam was “on”. Whenever the ROIs’ mismatch exceeded the gating windows, AlignRT automatically shot the beam off.

2.5. Tumour Movements During SBRT in TIVA Controlled BH - Assessed by Calypso System

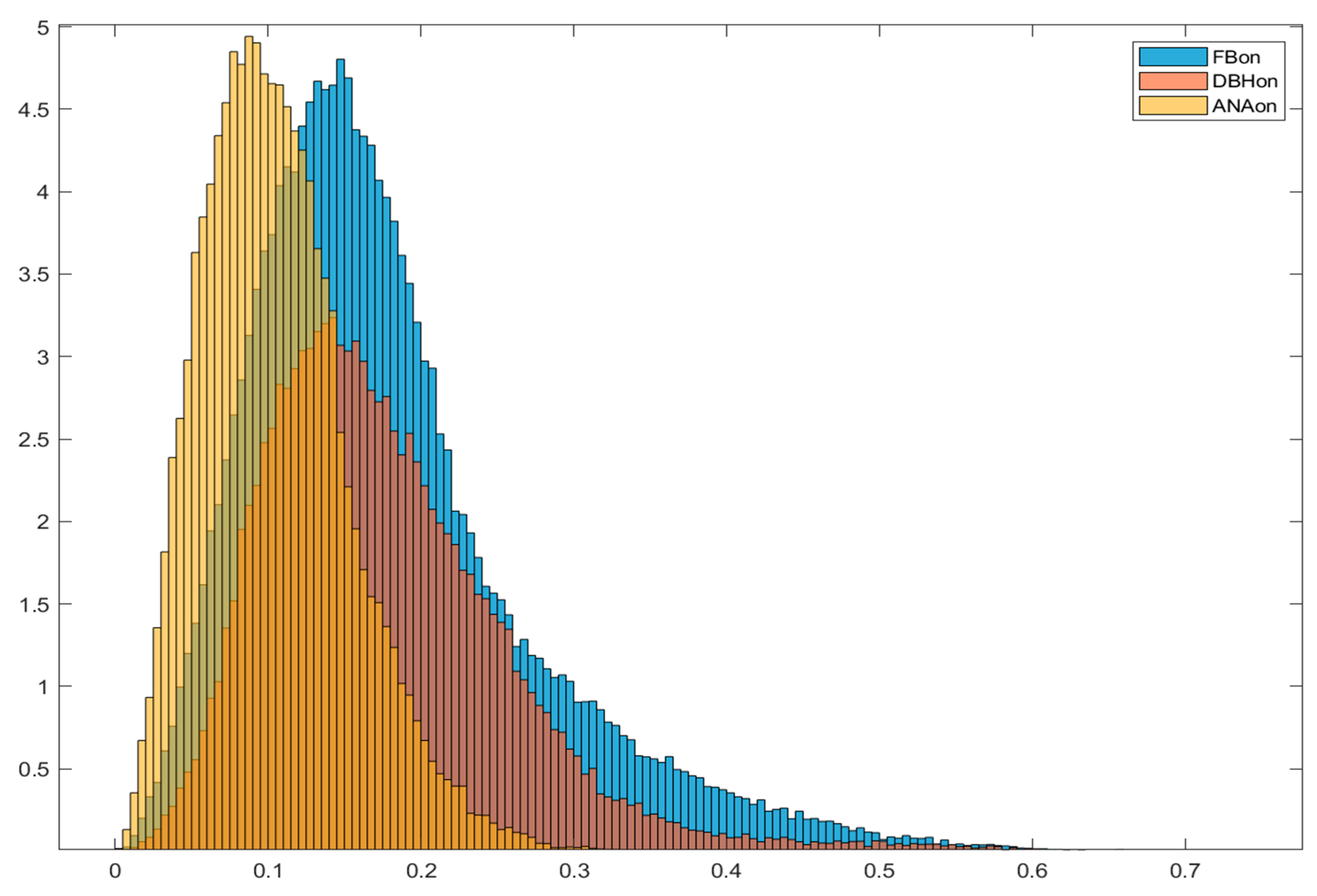

During 2023 we continued with implantation of Calypso fiducials in upper abdominal lesions (UAL), and treated those patients with SBRT in TIVA controlled BH, but using Calypso system as motion management. There were total of 23 patients with UAL that were treated in such manner. We compared this subgroup to 23 patients with UAL treated in voluntary BH with implanted Calypso fiducials and 23 patients with UAL treated in FB with implanted Calypso fiducials. By analysing radial movement histograms (

Figure 1.), initial positioning displacement and treatment length we came to the following conclusions:

Movement Analysis and Positioning Accuracy: TIVA controlled BH achieved the smallest geometric displacement (0.05 cm) and rotation (3.8 degrees), indicating improved positioning stability.

Movement Tracking and Treatment Time: TIVA controlled BH reduces median radial movement during treatment to 0.26 cm with a total treatment time of 46.2 minutes (~2 hours), compared to FB and voluntary BH which have higher movement and longer treatment times. During beam-on, TIVA controlled BH showed the lowest median radial movement (0.1 cm) and longest average treatment interval (19.5 s), indicating better motion control

Movement Histograms and Data Visualization: Normalized histograms of tracking movement during all treatment phases and beam-on periods confirmed reduced motion with TIVA controlled BH compared to FB and voluntary BH, supporting improved treatment precision.

Clinical Implications and Future Directions: TIVA controlled BH reduced uncertainties, improved repeatability and imaging, enabling single-fraction treatment with elective lymph nodes irradiation, and eliminating the need for fiducials.

2.6. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy

The TIVA procedure was essentially used to perform most identical exhale BHs for the patients during planning and SBRT procedures, by controlling respiratory shifts.

A contrast-free MSCT scan in TIVA controlled BH with a slice thickness of 1 mm was performed for planning purpose. Additionally, contrast-enhanced MSCT (with late arterial phase) and contrast-free MRI of the upper abdomen (T1 and T2 with high spatial fidelity) in voluntary BH were acquired for all patients. The contrast enhanced MR sequences tend to overestimate the actual volumes, so the contrast-free MR imaging was used.

The planning MSCT was coregistered (with deformable registration methods as needed) with MRI and contrast-enhanced MSCT. The CTV was defined as the gross tumour volume (GTV), with no additional margins and contoured on the T1 or T2 images of the MRI. Further corrections of CTV on planning MSCT scans were performed if necessary. We followed the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO), American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) and NCCN recommendations on CTV and OAR delineation.

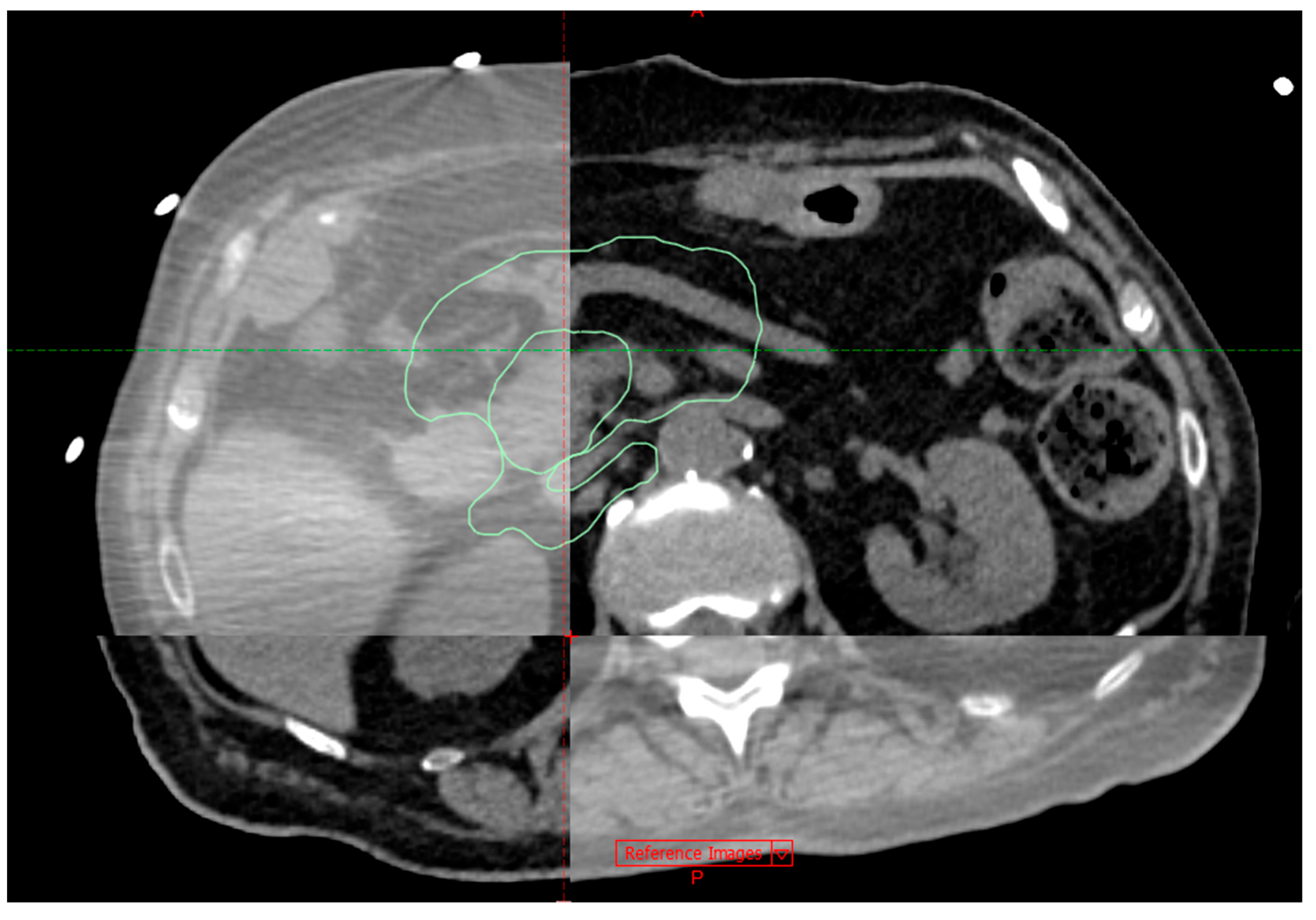

Patients were in a supine position with their arms by the side, on a vacuum pillow (

Figure 2.). No additional immobilization methods were used. A Varian EDGE® linear accelerator (Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used for treatment delivery.

All SBRT plans were optimized and delivered using Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy (VMAT), with Flattening filter free (FFF) 10 MV photon beams and dose rates up to 2400 MU/min. Criteria for stated beam energy and dose delivery technique were: 1) to achieve the best dose distributions; 2) to provide plans with low modulation and high QA passing rates. Alpha/beta ratio = 10 Gy was used to calculate the Biological effective dose to tumour (BED10).

SBRT procedure was performed in a single-fraction manner, using two PTVs – for regional lymph nodes (as NCCN Guidelines suggest that broad coverage of mesenteric vasculature ± nodal regions should be considered when feasible) and for primary tumour lesion.

Regional lymph nodes received the elective dose of 15 Gy (BED10 = 37.5 Gy) to the PTV borders, with mean dose of 18 Gy inside the PTV.

Pancreatic tumour received the simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) with prescribed dose of 30 – 35 Gy (BED10 = 120 – 157.5 Gy), in the following manner:

The mean dose to the SIB-PTV was considerably higher than the prescription dose,

No planning constraints on the dose maximums were set, as long as they were inside the SIB-PTV.

The optimization of the dose distribution was performed with the purpose of achieving a required target coverage of V(98–99.5%) = 80% of the prescribed dose for the SIB-PTV.

The result was a highly heterogeneous dose distribution inside the SIB-PTV. Average maximum was 138.7% (ranging 126.8 to 148.4%) of the prescription dose.

The PTV-CTV margin was defined according to van Herk’s formula: 2.5Σ + 0.7σ → 2.5 × 0.4 mm + 0.7 × 1.4 mm = 2 mm, in X, Y and Z directions:

Σ = 0.4 mm, as determined by end-to-end tests; for systemic error

σ = 2 mm, defined as gating windows; for random error.

Consequently, both PTVs were generated using 2 mm margin to CTVs. The average conformity index (the ratio of the volume of the 80% isodose line to the volume of the SIB-PTV) was 1.07 (ranging 1.03 to 1.12).

The OARs were divided into 2 groups:

Primary (directly adjacent to pancreas and highly radiosensitive) OARs: (stomach, duodenum, small bowel)

2. Other OARs (liver, great vessels, spinal cord, kidneys)

We followed dose-volume constraints according to Murphy et al. for the primary OARs, and AAMP recommendations for the other OARs, respectively [

21,

22]. As long as stated OAR constraints were met, the target coverage was prioritized over OAR sparing. The

Table 2. summarizes the dose–volume constraints.

Initial positioning was performed using AlignRT and coregistration of planning MSCT with CBCT using soft tissue and bony anatomy. After the treatment started, the beam was on as long as the patient was both in TIVA controlled BH and body contour was within the gating windows of AlignRT.

CBCT was regularly repeated after the 50% of the dose was delivered to recheck any possible mismatch of CTVs or OARs, and if needed, further corrections were made using CBCT. If AlignRT detected significant and permanent deviation of ROIs at any time during the treatment, the procedure was repeated.

According to the system’s reports, the “beam on” was on average 11.6% of treatment time, calculated from the first beam engage to the end of the treatment. Average treatment time was 46 minutes, while TIVA procedure took up an additional 68 minutes on average.

2.7. Response Evaluation and Follow-Up

Follow up was regularly scheduled every 3 months after SBRT by the treating radiation oncologist with clinical examination, a contrast-enhanced MSCT scan and blood tests, including Ca 19-9. Contrast-enhanced MRI imaging was added in case of regional and/or distant relapse suspicion. RECIST criteria were used for analysis of local and distant control [

23]. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.03 was used to score acute and late toxicity.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

End points were: OS, LC (i.e. freedom from local progression - FFLP), progression-free survival (PFS) and toxicity. One-year OS was calculated as a ratio of patients that survived at least 12 months and all patients. FFLP was defined as radiological progression of the primary lesion within the PTV. FFLP and PFS were calculated from the time of diagnosis to the first radiological assessment of local progression or regional/distal progression, respectively. Patients that did not develop disease progression were censored at the date of the last scan. OS, FFLP, PFS, and rates were calculated from the time of diagnosis to death, following the Kaplan–Meier method. The log-rank test statistic was used for univariate analysis, with significant difference considered when p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

All patients completed the treatment in a single-fraction with no delays. Median follow-up was 15 months (range 7–32 months). Forty-one patients (74.5%) received prescribed dose of 31.25 Gy, which was a median dose. Ten patients (18.2%) received prescribed dose of 30 Gy – the dose was reduced to meet the OAR constraints. Four patients (7.3%) with particularly favourable anatomy received prescribed dose of 35 Gy. Treatments lasted between 30-70 minutes, and there were 10-14 beam-ons per treatment, each lasting approximately 18-36 seconds and the times between them were beam-offs. Eleven patients (20%) had Calypso fiducials implanted.

Figure 3. represents a planning MSCT coregistration with CBCT on a treatment table.

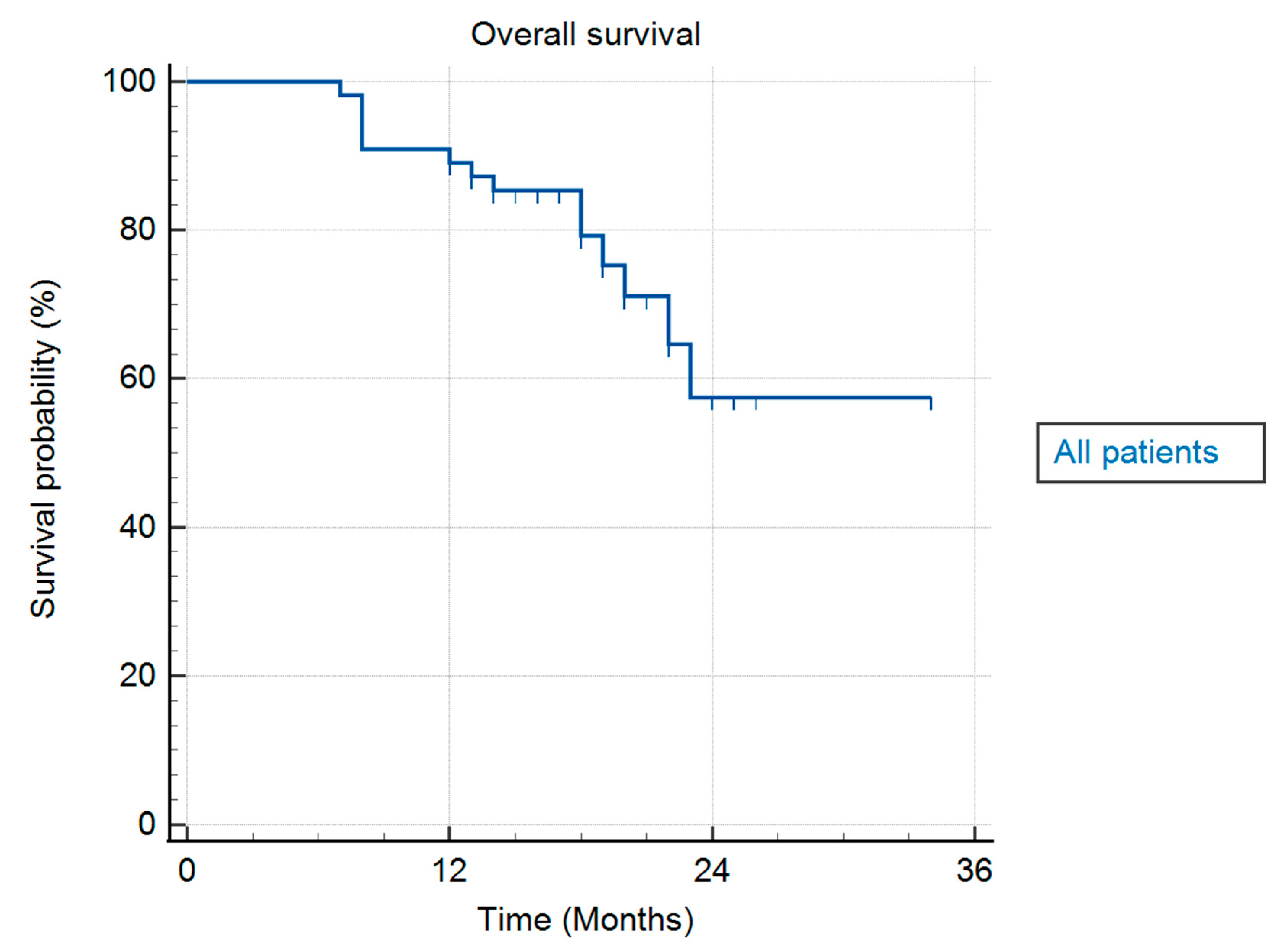

Mean OS was 26.7 months (range 7–34 months), presented as median OS was not achieved. Median time from diagnosis to SBRT was 2 months (range 1–5 months). One-year FFLP, one-year OS, and one-year PFS were 100%, 90.9%, and 85.5%, respectively.

Table 3. summarizes the results for FFLP, PFS, and OS. In

Figure 4, an actuarial curve for OS is shown.

Forty-two patients (76.4%) received systemic treatment. On actuarial analysis, patients that received chemotherapy had significantly better OS (log-rank, p = 0.05) (

Figure 5A).One patient (2%) had radiological local disease progression (at 23 months, accompanied by distal progression). Other patients had either local regression or stable local disease. Seven patients (12.7%) had complete local response to treatment, with no visible primary lesion on diagnostic imaging during follow-up, typically 12 months after SBRT.

Median PFS was 12 months (range 7–23 months). Twenty patients (36.4%) had distant progression of the disease, and 35 patients (63.6%) had systemic stable disease. On actuarial analysis patients that had no distant progression had better OS (log-rank, p = 0.0001) (

Figure 5B).

Median tumour volume (GTV) was 32.6 cm3 (range 6.7—98.1 cm3). On actuarial analysis, there was no impact of tumour volume on OS.

Acute toxicities grade 1 and grade 2 (fatigue, nausea, abdominal spasm or abdominal pain) were successfully treated with proton pump inhibitors, antiemetics and spasmolytics. Late toxicities Grade 1 (abdominal spasm or pain, and/or gastroesophageal reflux), developing six months or later after SBRT, were successfully treated with similar symptomatic treatment. No patients reported grade 2 late toxicities. Toxicity summary is shown in

Table 4.

Forty-one patients (74.5%) were alive at the time of analysis. Thirty-five patients (85.4%) from this subgroup received systemic treatment.

4. Discussion

SBRT as the treatment for patients with upper abdominal (including pancreatic) lesions today is considered as well established and effective treatment. Also, positive impact of dose escalation to LC and OS has been shown.

Single-fraction SBRT is very appealing, although still not thoroughly investigated concept in radiation oncology [

24]. The avoidance of single-fraction SBRT for pancreatic lesions (and upper abdominal targets, in general) still exists in general, primarily due to increased gastrointestinal (GI) toxicities previously reported [

26,

27]. Furthermore, multifractional SBRT regimes (3 – 5 fractions), became generally established to present day, as they have shown to limit GI toxicity, [

28].

Motion management techniques in FB have essentially two approaches: 1) to establish the whole volume of lesion’s movements and to irradiate that volume (e.g. 4D CT generated ITV); 2) to track the movements in real time and irradiate moving target (e.g. fiducial based), or to irradiate the lesion in certain anatomical position (e.g. respiratory gating). On the other hand, techniques in BH attempt to mitigate or cease the lesion’s movements and reduce PTV-CTV margins (e.g. voluntary BH). In both cases (FB and BH) there are still considerable uncertainties that limit considerable dose escalations and single-fraction SBRT in upper abdominal region.

The motion management technique presented in our paper had essentially the opposite approach and it was actually inspired by intracranial stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) – not to track the movements, but to irradiate the non-moving target. We aimed to minimise tumour’s and OARs’ movements in a way to “mimic” the SRS. The encouraging reports from Greco et al. on prostatic cancer single-fraction SBRT were our further inspiration [

29,

30].

Eleven patients (20%) were treated with Calypso fiducials implanted, and our calculations showed lesions’ radial movements < 1 mm. Guided by Van Herk’s formula, we set both the PTV-CTV margin and AlignRT’s gating windows to 2 mm. Consequently, superior OARs spare was achieved that enabled safe single-fraction dose escalation to the tumour with extremely heterogeneous dose distributions that might have been potentially beneficial in treating central, hypoxic radioresistant areas.

Although we could not find any published data on the use of the TIVA with ACMV combined with OSG as an integrated intrafractional motion management technique during SBRT for LAPC, recently, non-invasive mechanical ventilation has been explored in radiotherapy [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Also, several forms of high frequency ventilation with or without anaesthesia have been applied in radiotherapy to suppress respiratory motion in the thorax and upper abdomen [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Mechanical ventilation provides two ways to reduce organ movement: by regulating breathing [

42,

43] and by prolonged BH combined with preoxygenation and induced hypocapnia. [

44,

45]. There are presumed advantages of TIVA with ACMV - no respiratory training or preparation for the patient is required; no hypercapnia during the procedure; the entire procedure takes less time compared to SBRT in voluntary BH; each respiratory cycle and ventilation parameters are identical during planning and SBRT. Possible disadvantages are - the patient needs to be put under TIVA twice; patient is dislocated from the anaesthesiologic team during the procedure which makes monitoring more challenging.

The considerable proportion of patients in our study (74.5%) were alive at the time of the analysis and all patients in this subgroup were free from local and distant relapse. Furthermore, 98% of all patients had local regression or stable disease with 12.7% patients having complete local response to treatment, with no visible primary lesion on diagnostic imaging which could lead to the potential conclusion that dose escalated single-fraction SBRT approach could yield better clinical outcomes.

The toxicity profile of SBRT in our study was very acceptable, as patients reported grade ≤ 2 acute and grade ≤ 1 late toxicity, and it is our impression that general absence of severe toxicity in our study could have been related to successful OARs sparing.

Possible disadvantages of this study are arising from its retrospective and single institution nature. However, in our opinion, presented preliminary results could be potentially valuable and encouraging basis for future prospective studies on this topic.

5. Conclusions

TIVA controlled BH combined with OSG as intrafractional motion management system during dose escalated single-fraction SBRT for LAPC presented in our study as an effective and safe local treatment for LAPC. Satisfying LC and OS with very acceptable toxicities were shown. The technique is at least non-inferior (in terms of efficacy and safety) compared to Calypso system for motion management. Our results indicated that the TIVA controlled BH and OSG enabled effective OARs sparing with a high dose heterogeneity inside the lesion and steep dose falloff outside, consequently allowing for safe dose escalated single-fraction SBRT. This approach could lead to possible improvements of clinical outcomes for the patients and could be considered as a part of the multimodality treatment for LAPC.

Future prospective clinical trials are needed to define the role of dose escalated single-fraction SBRT in the improvement of clinical outcomes for patients with LAPC.

Author Contributions

investigation, H.K., M.K.I. and M.L.; resources A.A. and H.F.; data curation, SD, KS; writing—original draft preparation, H.K., M.K.I. and D.K.; writing-review and editing. A.M.K., M.K.I. and D.S.; visualization, H.K. and D.K.; supervision, D.S.; project administration, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Specialty Hospital Radiochirurgia Zagreb (code number: 03/2025, date: 21 May 2025). All data in the current study had no personal identifiers and were kept confidential.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Authors wish to express their gratitude to the following radiation therapists: Jadranko Oroz, Domagoj Brkić, Sanja Brezovec and Marica Keser for their care and efforts while introducing this technology in our Institution.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| SBRT |

Stereotactic body radiotherapy |

| SABR |

Stereotactic ablative radiotherapy |

| LC |

Local control |

| BED |

Biologically Effective Dose |

| OS |

Overall survival |

| FB |

Free breathing |

| ITV |

Internal Tumour Volume |

| BH |

Breath hold |

| CTV |

Clinical target volume |

| PTV |

Planning target volume |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| LAPC |

Locally advanced pancreatic cancer |

| TIVA |

Total Intravenous Anaesthesia |

| ACMV |

Assist-Control Mechanical Ventilation |

| OSG |

Optical surface guidance |

| OAR |

Organs at risk |

| ECOG PS |

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status |

| MDT |

Multidisciplinary team |

| NCCN |

National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| MSCT |

Multi-Slice Computed Tomography |

| PET/CT |

Positron emission tomography/computed tomography |

| ASA |

American Society of Anaesthesiology |

| NIPB |

Non-invasive blood pressure |

| IBP |

Invasive arterial pressure |

| CBCT |

Cone beam CT |

| IG |

Image guidance |

| DBC |

Default body contour |

| ROI |

Region of interest |

| GTV |

Gross tumour volume |

| ESTRO |

European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology |

| ASTRO |

American Society for Radiation Oncology |

| SIB |

Simultaneous integrated boost |

| NCI |

National Cancer Institute |

| CTCAE |

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| FFLP |

Freedom from local progression |

| PFS |

Progression-free survival |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

References

- Tonini, V.; Zanni, M. Pancreatic cancer in 2021: What you need to know to win. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 5851–5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, J.D.; Surana, R.; Valle, J.W.; Shroff, R.T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2020, 395, 2008–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moningi, S.; Dholakia, A.S.; Raman, S.P.; Blackford, A.; Cameron, J.L.; Le, D.T.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.M.C.; Hacker-Prietz, A.; Rosati, L.M.; Assadi, R.K.; et al. The Role of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer: A Single-Institution Experience. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2015, 22, 2352–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyngold, M.; Parikh, P.; Crane, C.H. Ablative radiation therapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer: Techniques and results. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Version 2.2025. Available online: https://www. nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/pancreatic.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Dhont J, Harden SV, Chee LYS, Aitken K, Hanna GG, Bertholet J. Image-guided Radiotherapy to Manage Respiratory Motion: Lung and Liver. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2020, 32, 792–804. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussels, B.; Goethals, L.; Feron, M.; Bielen, D.; Dymarkowski, S.; Suetens, P.; Haustermans, K. Respiration-induced movement of the upper abdominal organs: a pitfall for the three-dimensional conformal radiation treatment of pancreatic cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2003, 68, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, T.B.; Nestle, U.; Grosu, A.-L.; Partridge, M. SBRT in pancreatic cancer: What is the therapeutic window? Radiother. Oncol. 2015, 114, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, F.; Yorke, E.D.; Davidson, M.; Zhang, Z.; Jackson, A.; Mageras, G.; Wu, A.J.; Goodman, K.A. Modeling Pancreatic Tumor Motion Using 4-Dimensional Computed Tomography and Surrogate Markers. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2015, 91, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens, E.; van der Horst, A.; Kroon, P.S.; Van Hooft, J.E.; Fajardo, R.D.; Fockens, P.; Van Tienhoven, G.; Bel, A. Differences in respiratory-induced pancreatic tumor motion between 4D treatment planning CT and daily cone beam CT, measured using intratumoral fiducials. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 1257–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Santanam, L.; Noel, C.; Parikh, P.J. Planning 4-Dimensional Computed Tomography (4DCT) Cannot Adequately Represent Daily Intrafractional Motion of Abdominal Tumors. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013, 85, 999–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palta, M.; Godfrey, D.; Goodman, K.A.; Hoffe, S.; Dawson, L.A.; Dessert, D.; Hall, W.A.; Herman, J.M.; Khorana, A.A.; Merchant, N.; et al. Radiation Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer: Executive Summary of an ASTRO Clinical Practice Guideline. Pract. Radiat. Oncol. 2019, 9, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, T.B.; Haustermans, K.; Huguet, F.; Morganti, A.G.; Mukherjee, S.; Belka, C.; Krempien, R.; Hawkins, M.A.; Valentini, V.; Roeder, F. ESTRO ACROP guidelines for target volume definition in pancreatic cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2020, 154, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Device Network. Verdict Media Limited. Available online: https://www.medicaldevice-network.com/news/ newsvarian-medical-gets-fda-approval-calypso-soft-tissue-Beacon-transponder-4323298/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

- Kaučić, H.; Kosmina, D.; Schwarz, D.; Mack, A.; Šobat, H.; Čehobašić, A.; Leipold, V.; Andrašek, I.; Avdičević, A.; Mlinarić, M. Stereotactic Ablative Radiotherapy Using CALYPSO® Extracranial Tracking for Intrafractional Tumor Motion Management-A New Potential Local Treatment for Unresectable Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer? Results from a Retrospective Study. Cancers (Basel). 2022, 14, 2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.varian.com/.

- Callery, M.P.; Chang, K.J.; Fishman, E.K.; Talamonti, M.S.; Traverso, L.W.; Linehan, D.C. Pretreatment Assessment of Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Expert Consensus Statement. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2009, 16, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.intersurgical.com/.

- https://visionrt.com/our-solutions/alignrt/.

- Murphy, J.D.; Christman-Skieller, C.; Kim, J.; Dieterich, S.; Chang, D.T.; Koong, A. A Dosimetric Model of Duodenal Toxicity After Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2010, 78, 1420–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedict, S.H.; Yenice, K.M.; Followill, D.; Galvin, J.M.; Hinson, W.; Kavanagh, B.; Keall, P.; Lovelock, M.; Meeks, S.; Papiez, L.; et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy: The report of AAPM Task Group 101. Med Phys. 2010, 37, 4078–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhauer, E.A.; Therasse, P.; Bogaerts, J.; Schwartz, L.H.; Sargent, D.; Ford, R.; Dancey, J.; Arbuck, S.; Gwyther, S.; Mooney, M.; et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1. 1). Eur. J. Cancer 2009, 45, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlizzi, M.; Limkin, E.; Sellami, N.; Louvel, G.; Blanchard, P. Is single-fraction the future of stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)? A critical appraisal of the current literature. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2023, 39, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutera, P.A.; Bernard, M.E.; Gill, B.S.; Harper, K.K.; Quan, K.; Bahary, N.; Burton, S.A.; Zeh, H.; Heron, D.E. One- vs. Three-Fraction Pancreatic Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy for Pancreatic Carcinoma: Single Institution Retrospective Review. Front Oncol. 2017, 7, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, D.; Goodman, K.A.; Lee, F.; Chang, S.; Kuo, T.; Ford, J.M.; et al. Gemcitabine chemotherapy and single-fraction stereotactic body radiotherapy for locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008, 72, 678–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellenberg, D.; Kim, J.; Christman-Skieller, C.; Chun, C.L.; Columbo, L.A.; Ford, J.M.; et al. Single-fraction stereotactic body radiation therapy and sequential gemcitabine for the treatment of locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011, 81, 181–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollom, E.L.; Alagappan, M.; von Eyben, R.; Kunz, P.L.; Fisher, G.A.; Ford, J.A.; et al. Single- versus multifraction stereotactic body radiation therapy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: outcomes and toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014, 90, 918–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Fuks, Z. Single-Dose Radiotherapy for Prostate Cancer-Lessons Learned From Single-Fraction High-Dose-Rate Brachytherapy-Reply. JAMA Oncol. 2021, 7, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Vazirani, A.A.; Pares, O.; Pimentel, N.; Louro, V.; Morales, J.; Nunes, B.; Vasconcelos, A.L.; Antunes, I.; Kociolek, J.; Fuks, Z. The evolving role of external beam radiotherapy in localized prostate cancer. Semin Oncol. 2019, 46, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkes, M.J. Breath-holding and its breakpoint. Exp Physiol. 2006, 91, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkes, M.J.; Green, S.; Stevens, A.M.; Clutton-Brock, T.H. Assessing and ensuring patient safety during breath-holding for radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, M.J.; Green, S.; Stevens, A.M.; Parveen, S.; Stephens, R.; Clutton-Brock, T.H. Safely prolonging single breath-holds to >5min in patients with cancer; feasibility and applications for radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.J.; Green, S.; Stevens, A.M.; Parveen, S.; Stephens, R.; Clutton-Brock, T.H. Reducing the within-patient variability of breathing for radiotherapy delivery in conscious, unsedated cancer patients using a mechanical ventilator. Br J Radiol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ooteghem, G.; Dasnoy-Sumell, D.; Lambrecht, M.; et al. Mechanically-assisted non-invasive ventilation: a step forward to modulate and to improve the reproducibility of breathing-related motion in radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2019, 133, 132–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.S.; Parkes, M.J.; Snowden, C.; et al. Mitigating respiratory motion in radiation therapy: rapid, shallow, non-invasive mechanical ventilation for internal thoracic targets. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2019, 103, 1004–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, P.; Kraus, H.-J.; Mühlnickel, W.; Sassmann, V.; Hering, W.; Strauch, K. High-frequency jet ventilation for complete target immobilization and reduction of planning target volume in stereotactic high single-dose irradiation of stage I non-small cell lung cancer and lung metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010, 78, 136–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galmén, K.; Freedman, J.; Toporek, G.; Goździk, W.; Harbut, P. Clinical application of high frequency jet ventilation in stereotactic liver ablations – a methodological study. F1000 Res. 2018, 7, 773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audag, N.; Van Ooteghem, G.; Liistro, G.; Salini, A.; Geets, X.; Reychler, G. Intrapulmonary percussive ventilation leading to 20-minutes breath-hold potentially useful for radiation treatments. Radiother Oncol. 2019, 141, 292–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, I.M.; Nair, G.B.; Maurer, B.; Guerrero, T.M. High frequency percussive ventilation for respiratory immobilization in radiotherapy. Tech Innov patient Support Radiat Oncol. 2019, 9, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emert, F.; Missimer, J.; Eichenberger, P.A.; et al. Enhanced deep-inspiration breath hold superior to high-frequency percussive ventilation for respiratory motion mitigation: a physiology-driven, MRI-guided assessment toward optimized lung cancer treatment with proton therapy. Front Oncol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ooteghem, G.; Dasnoy-Sumell, D.; Lambrecht, M.; et al. Mechanically-assisted non-invasive ventilation: a step forward to modulate and to improve the reproducibility of breathing-related motion in radiation therapy. Radiother Oncol. 2019, 133, 132–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, N.S.; Parkes, M.J.; Snowden, C.; et al. Mitigating respiratory motion in radiation therapy: rapid, shallow, non-invasive mechanical ventilation for internal thoracic targets. Int J Radiat Oncol. 2019, 103, 1004–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.J.; Green, S.; Stevens, A.M.; Clutton-Brock, T.H. Assessing and ensuring patient safety during breath-holding for radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, M.J.; Green, S.; Stevens, A.M.; Parveen, S.; Stephens, R.; Clutton-Brock, T.H. Safely prolonging single breath-holds to > 5 min in patients with cancer; feasibility and applications for radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 2016. https:// doi.org/ 10. 1259/ bjr. 20160 194., Parkes MJ, Green S, Kilby W, Cashmore J, Ghafoor Q, Clutton-Brock TH. The feasibility, safety and optimization of multiple prolonged breath-holds for radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).