1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by dysregulated immune responses, with the synovial membrane serving as the primary site of pathogenic immune cell activation, autoantibody production (e.g., rheumatoid factor, anti-citrullinated protein antibodies), and early inflammatory cascades that cause synovitis and osteochondral destruction [

1,

2,

3]. RA affects approximately 1% of the global population and presents a significant burden due to joint pain, stiffness, and progressive disability [

4]. Citrullination, a post-translational modification where peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD) enzymes convert arginine residues to citrulline, is considered a key driver in RA pathogenesis [

5]. The citrullination by PADI4(Protein-arginine deiminase type-4) is influenced by multiple factors, including genetic predisposition, smoking, bacterial or viral infections, and autophagy [

3,

6].

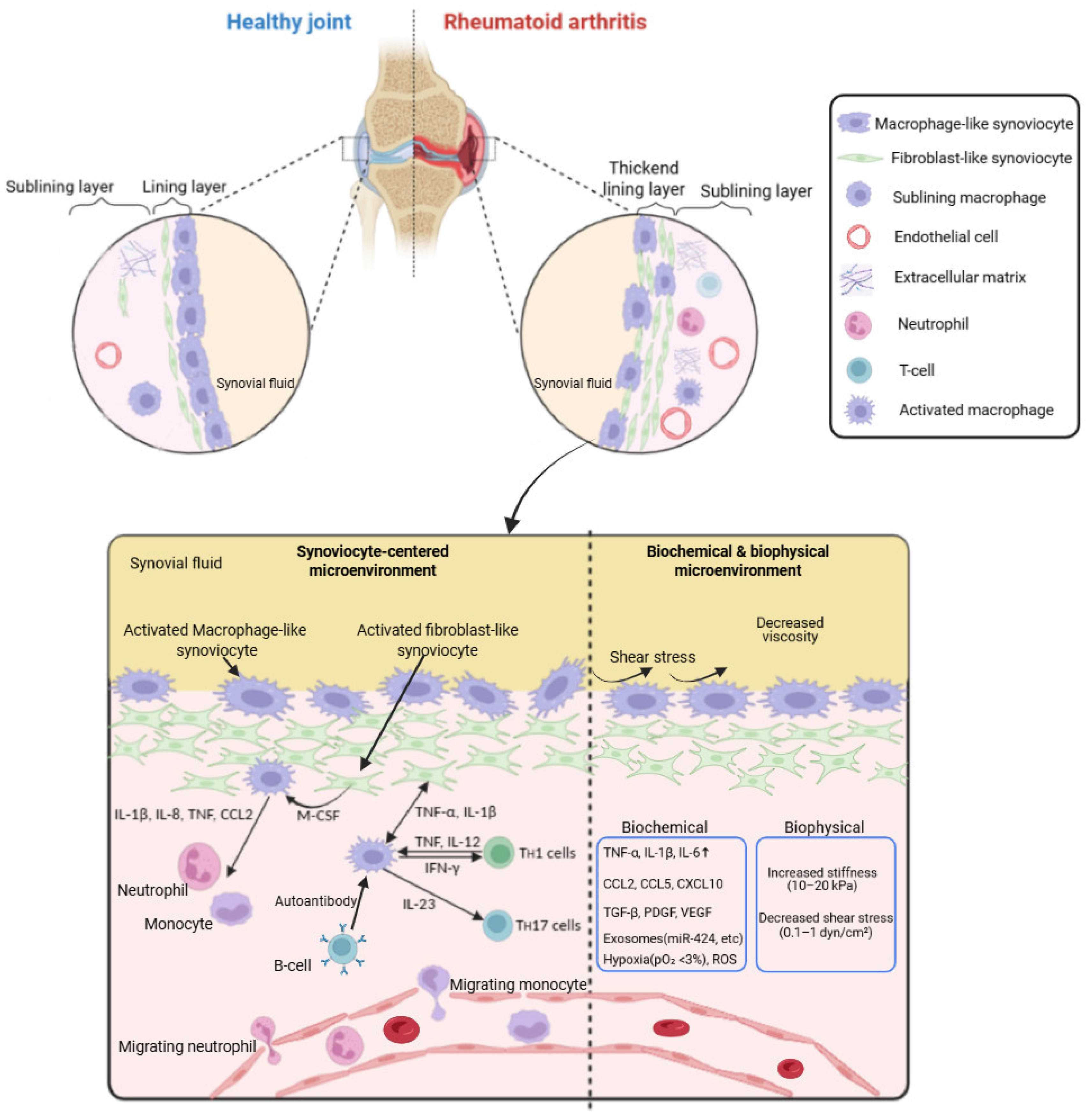

The synovial membrane, or synovium, is the principal site of pathological processes in RA, undergoing hyperplasia of fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS), dense infiltration of immune cells, and neovascularization that together form the invasive pannus tissue [

7]. In RA, the primary pathological changes in the synovium include synovial hyperplasia, inflammation, increased angiogenesis, and exudation, all of which lead to cartilage degradation and bone erosion. The synovial lining becomes thickened due to the proliferation of synovial cells including fibroblasts and macrophages. The immune cell–fibroblast–bone axis constitutes a central regulatory triad in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), wherein dysregulated crosstalk between activated immune cells (e.g., macrophages, T/B lymphocytes), fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS), and osteochondral cells (osteoclasts, osteoblasts) drives synovial hyperplasia, chronic inflammation, and osteochondral damage via RANKL/MMP-mediated cartilage degradation and bone erosion [

2,

7]. Within this altered synovial microenvironment, complex biochemical cues, such as elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6), and biophysical changes, such as increased tissue stiffness, drive the aggressive phenotype of resident stromal and immune cells, perpetuating chronic inflammation [

8].

Traditional in vitro culture systems and animal models have provided valuable insights into RA pathogenesis, but they often fail to recapitulate the human-specific, multicellular architecture and dynamic mechanical forces present in the diseased synovium, limiting their predictive power for therapeutic screening [

9]. Moreover, these often focus on narrowly defined parameters based on specific study objectives rather than addressing the complex organ-level and tissue or cell interaction dynamics inherent to the human body [

9,

10,

11]. Consequently, traditional in vitro and animal models are inherently limited in the replication of the microenvironment of synovial tissue. To overcome these limitations, microengineering approaches including microfluidic “synovium-on-a-chip” platforms, tunable hydrogel scaffolds, and 3D-bioprinted synovial organoids have emerged as powerful tools to reconstruct key features of the synovial niche with precise control over cellular composition, mechanical properties, and soluble factor gradients [

12].

Recent advances include vascularized synovium-on-a-chip devices that mimic leukocyte extravasation under physiologically relevant shear stresses, droplet-based microfluidic systems for single-cell transcriptomic profiling of patient-derived synovial cells, and stimuli-responsive hydrogels that release therapeutics in response to RA-specific enzymatic activity [

13,

14,

15]. By integrating microscale engineering with primary human cells and advanced sensing modalities, these platforms enable real-time monitoring of cytokine secretion, barrier integrity, and cell migration, thereby offering unprecedented insight into RA pathophysiology and drug responses in a patient-relevant context [

10].

In this review, we outline the pathological hallmarks of the RA synovial microenvironment, then survey traditional models, and finally discuss the latest microengineering strategies to model and manipulate this niche along with emerging opportunities.

2. Microenvironment of RA Synovium

Understanding the in vivo synovial microenvironment, the complex milieu of molecular and mechanical signals, is pivotal in establishing a RA synovial membrane model for unraveling RA pathogenesis and developing targeted therapies.

2.1. Structural Components

The synovium is a specialized connective tissue that lines the inner surface of synovial joints, bursae, and tendon sheaths [

16,

17]. It plays a crucial role in joint lubrication, immune regulation, and nutrient exchange. The synovial membrane comprises two distinct layers: the intimal layer (intima, synovial lining) and the subintimal layer (subintima, subsynovial tissue) [

16]. The intimal layer with specialized synoviocytes is 1–3 cell layers thick and faces the joint space. Unlike other epithelia, it lacks a basement membrane, allowing for efficient molecular exchange between synovial fluid and the subintima. This layer is responsible for synthesizing hyaluronic acid, lubricin, and cytokines essential for joint lubrication and immune responses. In RA, the intima expands to 10–20 layers, predominantly FLS, forming the aggressive pannus that invades cartilage and bone [

18]. The subintimal layer contains blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves [

19,

20,

21]. It provides structural support and facilitates immune cell trafficking between the bloodstream and the joint cavity. Nerve endings within this layer contribute to nociception in inflammatory joint diseases and reduced nerve supply is observed in superficial intimal regions of synovial membrane harvested from RA patients [

20].

2.2. Cellular Components

The synovium contains various lineages of resident and infiltrating cells, each playing a key role in joint homeostasis and disease [

22]. It harbors two main types of synoviocytes: type A synoviocytes (Resident synovial macrophage, RSMs) and type B synoviocytes (Fibroblast-like synoviocytes, FLSs)(

Figure 1).

Synovial tissue contains both tissue-resident macrophages and infiltrating monocyte-derived macrophages. Resident macrophages form a protective barrier at the lining and contribute to homeostasis, while monocyte-derived cells amplify inflammation via TNF-α and IL-1β production. [

23,

24]. RSMs are derived from the monocyte/ macrophage lineage and are highly phagocytic, responsible for clearing debris, apoptotic cells, and immune complexes [

24,

25]. These cells express Fc-gamma immunoglobin receptor (FcγR) with positive CD68 and CD 163, whereas the expression of major histocompatibility class II molecules (MHC-II) is identified [

23]. During the early stages of the immune response, they can absorb and degrade extracellular constituents, cell debris, microorganisms, and many antigens within the synovial membrane. They secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-1β) in diseases like RA, contributing to joint inflammation.

FLSs are mesenchymal-derived cells responsible for synovial fluid production and synthesize hyaluronic acid, lubricin, and extracellular matrix components [

25]. In RA, FLS become hyperproliferative and produce matrix-degrading enzymes (MMPs, Matrix metalloproteinases), driving cartilage destruction [

18]. Recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies identify distinct fibroblast subsets in the synovium which include CD55

+ homeostatic FLS with the maintenance of synovial lubrication and ECM integrity and CD248

+ pathogenic FLS with the induction of inflammation and cartilage destruction in RA [

26]. T and B lymphocytes, plasma cells, and dendritic cells infiltrate the synovium, forming ectopic lymphoid-like structures that sustain autoantibody production and cytokine secretion [

27].

2.3. Extracellular Matrix

The extracellular matrix (ECM) of the synovium is a dynamic structure that maintains tissue homeostasis and facilitates cell signaling. It is composed of collagen, proteoglycans (aggrecan, decorin), non-collagen protein, glycoprotein (fibronectin, laminin), and matrix-degrading enzymes, which collectively regulate synovial architecture and function [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. An amorphous or fine fibrillar ultrastructure was found in the synovial inner lining including collagens III, IV, V, and VI with little type I collagen [

28]. Altered ECM composition—e.g., fibronectin and type III collagen deposition—changes matrix porosity and ligand presentation, affecting cell adhesion and migration [

35]. Once the components and structure of ECM change, it can lead to the occurrence and development of arthritis disease by elevated angiogenesis, accelerated cell differentiation, immune activation, and other adverse immunologic events.

2.4. Biochemical and Mechanical Cues

The RA synovial membrane is a dynamic interface where biochemical and mechanical signals converge to drive disease progression. Biochemical environment factors include proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, extracellular vesicles, hypoxia, and reactive oxygen species. Several proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are elevated in RA synovial fluid and tissue, driving FLS activation, leukocyte recruitment, and osteoclastogenesis [

6,

36]. Chemokines orchestrate leukocyte migration into the synovium, monocytes recruiting, and T-cell retention [

36]. In RA synovial membrane, VEGF promotes angiogenesis, and TGF-β modulates proliferation and extracellular matrix production of FLS whereas PDGF supports fibroblast survival and migration [

37]. Synovial exosomes carry miRNAs and proteins that modulate FLS and immune cell function, propagating inflammation and joint damage [

38]. Hypoxia (pO

2<20 mm Hg) is characteristic of RA synovium, stabilizing HIF-1α/2α in FLS and macrophages to upregulate angiogenic and glycolytic genes [

39,

40]. On the other hand, oxidative stress from elevated ROS contributes to DNA damage, NF-κB activation, and MMP induction in FLS [

41].

Mechanical cues involve matrix stiffness, shear stress, mechanical strain, and rheological changes of synovial fluid. RA synovial tissue exhibits increased stiffness versus healthy [

41]. Stiff matrix enhances FLS activation via integrin-mediated mechanotransduction, promoting invasive behavior and MMP expression [

42]. RA synovial fluid flow generates decreased shear stress across the intima due to less viscosity, and FLS become activated and invasive under certain shear on the synovium-on-a-chip model, whereas shear stress modulates FLS calcium signaling and influences cytokine release [

43]. During cyclic strain on the synovium in joint movement, FLS senses stretch via cadherin and ADAM15, triggering invasive phenotypes through MAPK pathways [

44].

2.5. Crosstalk Between RA Synoviocytes and Inflammatory Cells

The synovium becomes inflamed, with increased numbers of inflammatory cells including T cells (Th1 and Th17 cells), B cells, dendritic cells, mast cells, and macrophages, and neovascularization—forming the pannus that invades cartilage and bone [

45,

46,

47]. IFN-γ from Th1 cells activates resident synovial macrophages and promotes inflammation, whereas, IL-17 secreted by Th17 cells enhances neutrophil recruitment and synovial inflammation [

46,

47]. Activated macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and matrix metalloproteinase, which leads to the formation of pannus, an abnormal layer of tissue that invades and damages surrounding cartilage and bone [

47,

48,

49]. On the other hand, B cells contribute to RA through the production of autoantibodies including the anti-citrullinated protein antibodies and rheumatoid factor which enhances osteoclast activation [

3,

50].

The autoimmune response selectively directs immunological aggression toward multiple molecular and structural constituents of the synovial membrane, with ECM proteins, and post-translationally modified antigens serving as principal pathogenic foci [

46,

51]. In some individuals with genetic susceptibility, early self-reactivity against post-translationally modified proteins develops mostly in mucosal areas, with subsequent targeting of synovial tissue by effector T cells [

52].

The immune system stimulates fibroblast-like synoviocytes to exert inflammatory and tissue-destructive effects and exacerbate RA pathogenesis [

26,

48]. FLSs, the resident mesenchymal cells of the synovium, display abnormal behaviors such as hyperproliferation, resistance to cell death, and invasive properties in RA [

26]. They can directly interact with T cells through the presentation of antigens and co-stimulatory molecules such as ICAM-1, leading to the activation of autoreactive T cells [

52]. Activated T cells, in turn, produce pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-17 and IFN-γ, which further stimulate FLSs to produce inflammatory mediators and proteases [

47,

48]. FLSs also release chemokines (e.g., CCL2, CCL5) that recruit macrophages into the synovial tissue. Kuo et al. suggested that HBEGF

+ inflammatory macrophages are enriched in RA tissues and could promote the fibroblast’s invasiveness depending on the response of synovial fibroblast EGFR to EGF ligand expressed by them. This interaction between FLSs and macrophages creates a positive feedback loop that sustains the inflammatory environment within the joint.

2. Traditional Models and Their Limitation

Traditional in vitro models of the rheumatoid arthritis (RA) synovium employ monocultures, co-cultures, and explant-conditioned media to mimic key aspects of the inflamed joint microenvironment.

Primary studies utilized the traditional 2D culture of fibroblast-like synoviocytes derived from synovial fluid to study the inflammatory process in RA for better insights into the pathogenesis of the disease and facilitating the drug discovery processes [

53,

54]. The monolayer 2D culture could be expanded with the help of coculture models which can be utilized to study complex cell interactions. A previous study suggested that human synovial fibroblasts derived from deidentified synovial tissues of RA patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty remarkably suppressed TNF-mediated induction of IFN-β autocrine loop and downstream expression of IFN-stimulated genes (CXCL9, CXCL10, macrophage activators) without cell contact when coculture macrophages by the trans-well culture mode [

54]. Chwastek et al. performed the coculture of human fibroblast-like synoviocytes and peripheral-like neurons differentiated from neuroepithelial stem cells by transwell insert mode to mimic synoviocyte-neuron interaction responsible for the induction of chronic pain in rheumatoid arthritis [

55].

Explant-conditioned media models incorporate the full complement of synovial secretome to induce dendritic cell or FLS activation but cannot model cell–cell contact. Tissue explants represent a critical bridge between in vitro cell culture models and in vivo animal studies [

56,

57]. They consist of ex vivo cultured tissue fragments that retain the three-dimensional structure, cellular diversity, and ECM composition of the original tissue. It maintains native cellular architecture, allowing for a more accurate recapitulation of disease pathology compared to traditional 2D or even some 3D culture models. Synovial tissue explants could be obtained from synovial biopsies or surgical synovectomy samples from RA patients and be used to study synovial fibroblast activation, angiogenesis, immune cell infiltration, and testing of targeted therapies, including TNF-α, IL-6, and JAK inhibitors. Wu et al. demonstrated that Kirenol, a diterpenoid extracted from the Chinese herb

Siegesbeckiae inhibited the migration, invasion, and proinflammatory IL-6 secretion of FLSs by using RA-associated synovial fibroblasts derived from the culture of RA synovial explants [

58].

Because they often fail to recapitulate the complex microenvironment of the synovium, more physiologically relevant models should be necessary.

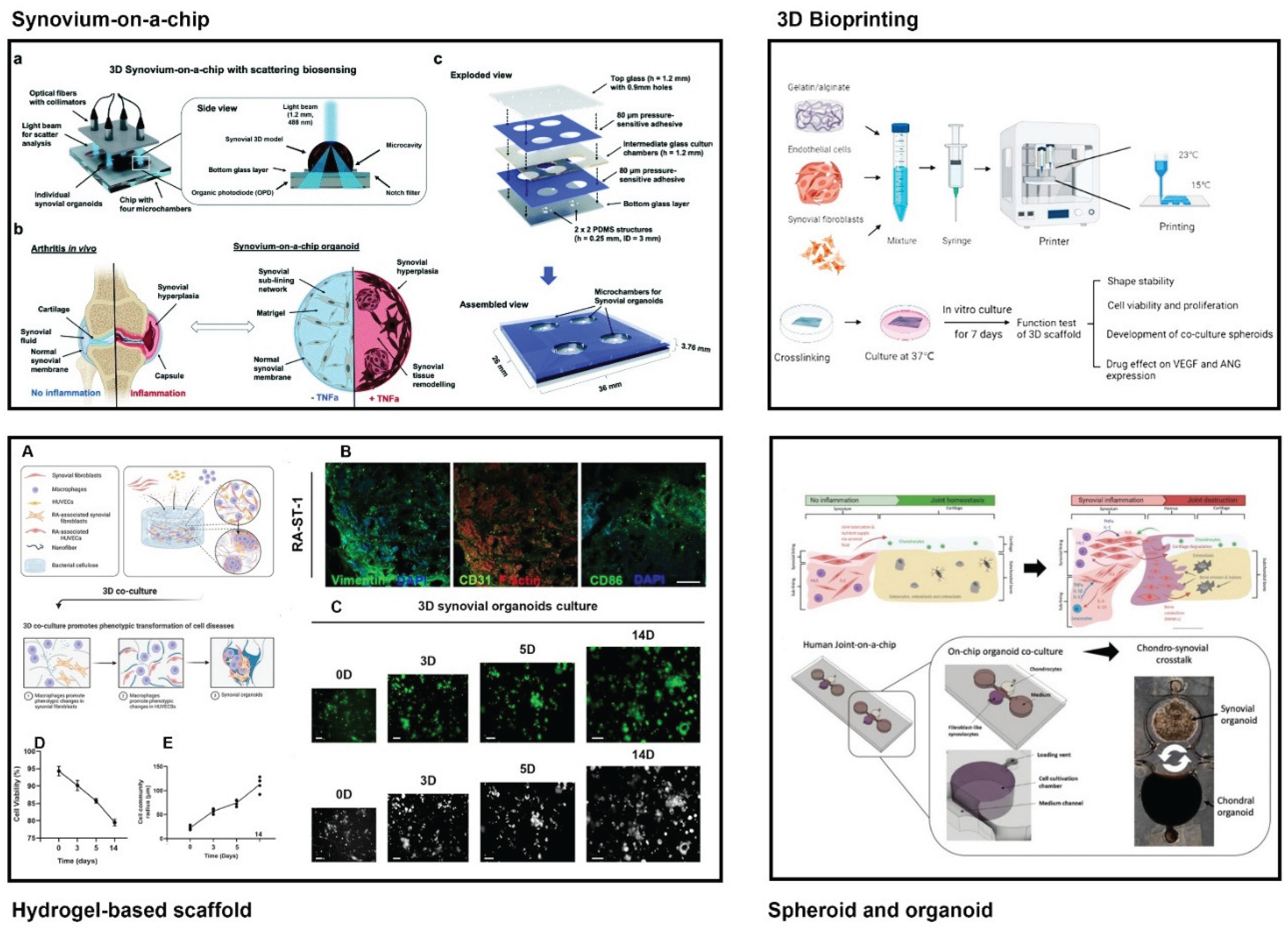

3. Microengineering Strategy to Recapitulate the Microenvironment of RA Synovium

Microengineering models have been developed to overcome the shortcomings of traditional RA synovial models and transformed RA synovial research by providing platforms that recapitulate the complex cellular, molecular, and biophysical characteristics of the inflamed synovium(

Figure 2,

Table 1).

3.1. Synovium-on-a-Chip

Synovium-on-a-chip platforms have emerged as a promising tool for modeling synovial membrane structure and function, investigating joint disorders, and evaluating drug responses [

59]. These microfluidic devices incorporate synoviocytes, ECM, and biochemical factors to recreate the structural and functional characteristics of the synovial membrane, under physiologically relevant conditions, providing a dynamic platform for disease modeling and drug testing [

10]. Furthermore, such a chip system is very cost-effective due to the requirement of fewer cells and microliter levels of reagents compared to traditional 2D and 3D cell culture models.

Vascularization: Because enhanced angiogenesis is known as a major change in RA, the vascularization component of synovium-on-a-chip could not be neglected. Initial vascularized synovium-on-a-chip was designed to be capable of the three-dimensional configuration of synovium and its vasculature as well as simulation of biomechanical stress and inflammatory stimulation, using a commercially available platform, The Chip-S1

® (Emulate Inc., Boston, USA) [

13]. Their model was established from primary human fibroblast-like synoviocytes for replicating the synovial lining and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) for recreating its associated vasculature, in which the attachment of monocytes to the surface of the endothelial channel occurred in the inflamed condition by IL−1β, thus simulating the cell recruitment in the early inflammatory stages seen in vivo.

Recently, more complicated synovium-on-a-chip models have emerged in order to make a perfect simulation of the synovial microenvironment including vasculature, monocyte, and synovial fluid [

60,

61,

62]. One of the well-accepted multi-channel OoC systems includes a vascularized synovium compartment with the endothelial channel, synovial fluid compartment, and cartilage compartment. Researchers identified the process of monocyte extravasation into the synovium in the first hours after TNF-α stimulation on this OoC in which fibrin gel was used as a biocompatible matrix to perform the 3D culture of synovial fibroblasts and articular chondrocytes in microfluidic devices.

Mechanical simulation: Fluid shear stress was focused in the synovial research field due to its influences on several synovial components during physiologic and pathologic movement [

63]. When co-cultured human dermal fibroblast, macrophage (THP-1 monocyte), primary human osteoblast, and chondrocyte using a µ-Slide I Luer ibiTreat (Ibidi, Germany) system regulated by regulated by a Masterflex

® Ismatec

® Reglo ICC Peristaltic Pump, it could simulate synovium as well as several components of synovial joint under mechanical stress [

61]. In terms of synovium, despite the application of human dermal fibroblast instead of human synovial fibroblast, these results demonstrated that the complex nature of in vivo human joint conditions could be simulated by this microfluidic co-culture system at 24 h and it might serve as a powerful tool for studying the pathophysiology of rheumatic diseases and testing potential therapeutics. A research group prepared the microfluidic chip by injection of the suspension of synovial fibroblast at a density of 1 × 10

7 cells/mL and linkage of a pressure-driven pumping system (Elveflow, OB1 MKII) coupled with a flow rate sensor to perfuse up to 6 cell-loaded microfluidic chips at the same time at a specific level of shear stress [

63]. The levels of TNFα released by synovial fibroblasts showed a linear increase with the intensity of the shear, with a 5-fold increase from shear stress of 3 to 8 dyne/cm

2, and a 2-fold increase from shear stress of 8 to 15 dyne/cm

2 in this synovium-on-a-chip model. In this study, the mechanical stimulation downregulated the release of IL-6 and MMPs for a short time exposure, whereas the stimulation for longer than 24 hours upregulated the levels of both IL-6 and MMPs. The other researchers demonstrated that upregulated expression of genes, HAS-1(hyaluronic acid synthase), and HAS-3 were observed when 0%–12% cyclic tensile strain was applied to hFLS for 2 h at 0.2 Hz on this synovium-on-a-chip [

13].

Integration of the immune/nervous system: Some authors focused on the importance of the lymphatic system and draining lymph nodes in the pathogenesis of RA inflammation in the synovium, and some authors emphasized that more attention should be given to immune cell and cytokine flow from the lymphatic vasculature in the in vitro model of the RA-afflicted synovium [

64,

65]. However, there has been no synovium-on-a-chip that combines the synovial membrane with supplying lymphatics, but advanced techniques for microchannel fabrication and controllable fluid dynamics, modeling lymphatic vasculature could allow researchers to find its therapeutic targets and study lymphatic structural and functional change in the pathogenesis of the other diseases.

Some authors attempted to elucidate possible interaction between synoviocytes and neurons in RA [

55,

66]. Synoviocytes could produce inflammatory mediators that activate and sensitize neurons and neurons, in turn, release neuropeptides like substance P, which further activate synoviocytes and other immune cells, perpetuating inflammation. the combination of synovial inflammation and nerve involvement in RA is a major contributor to the persistent and often debilitating pain that characterizes the disease. However, the synovium-on-a-chip combined with neurons has not been developed.

A research group conducted the study to identify the role of lymphatic dysfunction in RA and first demonstrated altered lymphatic function with near-infrared lymphangiography in RA patients. A researcher established a three-dimensional organoid culture model to simulate the synovial tissue containing synovial fibroblasts, memory CD4+ T cells, and memory B cells [

67]. By using fluorescence imaging and image analysis software, they identified the cytokine secretion profiles to recapitulate the interactions between immune cells and synoviocytes in the RA synovium.

3.2. Hydrogel-Based 3D Scaffolds

Hydrogel-based 3D scaffolds offer a biomimetic approach to engineering the RA synovial microenvironment by providing customizable mechanical properties, biochemical cues, and spatial organization that recapitulate key aspects of synovial physiology and pathology in vitro. Hydrogels are hydrophilic polymer networks capable of absorbing large amounts of water, closely mimicking the hydrated nature of native ECM and providing a supportive 3D milieu for cell encapsulation and migration [

68,

69]. Key tunable properties include crosslinking density (controlling pore size and stiffness), degradation rate (via hydrolytic or enzymatic mechanisms), and presentation of bioactive ligands (e.g., RGD peptides) to direct cell adhesion and signaling [

69,

70]. Mechanical properties can be tailored to match the RA synovial stiffness range (5–20 kPa) by adjusting polymer concentration, crosslinker type (e.g., UV-initiated methacrylation, Schiff base chemistry), and incorporation of reinforcing nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, nanoclay) [

71].

3.2.1. Natural Hydrogel Scaffolds

Collagen type I and type II hydrogels replicate the primary protein constituents of synovial ECM, supporting FLS attachment, proliferation, and MMP-mediated remodeling [

72]. Collagen hydrogels crosslinked with genipin or riboflavin exhibit tunable stiffness (1–10 kPa) and degradation rates, enabling studies of mechanotransduction in FLS activation and invasion [

73]. HA-based hydrogels could support chondrocyte and FLS viability while providing a promising platform for designing immunomodulatory biomaterials toward the treatment of RA [

74]. Methacrylated HA (HAMA) crosslinked under UV light yields hydrogels with tunable stiffness (2–15 kPa) and degradation, enabling studies of FLS migration under variable mechanical settings [

75]. GelMA hydrogels combine gelatin’s cell-adhesive motifs with photo-crosslinkable methacrylate groups, allowing precise control over crosslink density and mechanical properties [

76]. GelMA scaffolds with stiffness tuned to 5–20 kPa have been used to culture RA FLS and MSCs, reproducing hyperplastic lining formation and inflammatory cytokine profiles comparable to patient synovium [

15]. Alginate hydrogels crosslinked with calcium ions provide a simple, rapid gelation system for encapsulating synovial cells, though lack inherent cell-adhesive motifs [

77]. Composite alginate-collagen or alginate-gelatin hydrogels combine alginate’s mechanical tunability with biological cues from proteins, supporting co-culture of FLS, macrophages, and endothelial cells to model pannus tissue [

72,

77]. Chitosan–Matrigel composites (70:30 v/v) provide a low-cost, biocompatible 3D matrix in which both RA and non-RA FLS form dense networks, with compressive moduli comparable to soft tissues (~1–10 kPa) and high cell viability over 7 days [

78].

3.2.2. Synthetic Hydrogel Scaffolds

PEG hydrogels offer low protein adsorption, batch consistency, and facile functionalization with cell-adhesive peptides (e.g., RGD) and protease-sensitive linkers [

79]. PEG-diacrylate (PEGDA) hydrogels with stiffness gradients from 2 to 20 kPa have been employed to investigate FLS durotaxis and mechanosensitive gene expression (e.g., PRG4, MMPs). Short amphiphilic peptides (e.g., RADA16-I) spontaneously form nanofiber networks mimicking ECM fibrils, supporting 3D culture of FLS and immune cells without exogenous crosslinkers [

80]. These hydrogels enable injectable scaffold formats that gel in situ within the synovial cavity, providing minimally invasive platforms for drug delivery and cell therapy [

71].

Encapsulation of FLS and macrophages within hydrogels enables measurement of cell invasion, ECM degradation, and cytokine secretion under controlled mechanics [

14]. Dual-responsive hydrogels release therapeutics in response to MMP activity or pH changes in the inflamed synovium [

15]. Hydrogel scaffolds serve as platforms for testing anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory agents, revealing stiffness-dependent drug efficacy and FLS apoptosis profiles [

81].

3.3. Spheroids and Organoids

The 3D tissue engineering approach(spheroid) is a promising strategy that can recapitulate 3D physiological structures based on the cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions [

43,

82]. They might stimulate the synovial structural features and RA pathogenesis with various cellular components including synovial fibroblast, endothelial cells, macrophages, neurons, and immune cells. Furthermore, its application is expanding through advanced 3D in vitro tissue engineering approaches, including scaffold-free strategies (e.g., cell sheets and self-organization) and scaffold-based systems utilizing synthetic or natural polymers [

82,

83,

84]. Kiener et al. demonstrated that FLSs formed a compacted lining architecture through 3-week cultivation in spherical extracellular-matrix micromasses [

85]. The histological evaluation of FLSs micromass architecture showed rearranged FLSs around the extracellular matrix resembling the synovial lining, and the survival and compaction of monocytes/macrophages were observed in the new lining structure. Philippon et al. developed a 3D spheroid model of synovial tissue having the umbilical vein endothelial cells, FLSs, and macrophages derived from monocytes with a collagen-based 3D scaffold [

86]. In the presence of fibroblast growth factor 2, vascular endothelial growth factor, and RA synovial fluid, spheroids with RA fibroblast-like-synoviocytes showed outgrowth of macrophages within the spheroids. A 3D co-culture platform, a novel synovial organoid system developed by Chinese researchers contains THP-1-derived M1 macrophages, human umbilical vein endothelial cells, rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes and bacterial cellulose as a scaffold, which can mimic inflammatory and vascular microenvironment as well as synovial pathology in RA synovial tissues [

87]. In 2021, Rothbauer et al. presented a novel organoid-on-a-chip platform that simulates the interactions between synovium and cartilage in human joints [

88]. They established a chip-based three-dimensional tissue coculture model that recapitulates the reciprocal cross-talk between individual synovial and chondral organoids. Synovial organoids were made from Matrigel suspension containing FLSs harvested from RA patients undergoing synovectomy and chondral organoids from commercial human chondrocytes. In RA-FLS organoids, a considerably higher secretion performance was observed in MMP-13 and VEGF with an increase for later passages, which again equalized over three weeks of cell culture. Their results indicated that when co-cultivated with synovial organoids, chondral organoids induced a higher degree of cartilage physiology and architecture and showed different cytokine responses compared to their respective monocultures, highlighting the importance of reciprocal tissue-level cross-talk in the modeling of arthritic diseases.

3.4. 3D bioprinting

Bioprinting technologies—extrusion, stereolithography—pattern FLS, macrophages, and endothelial cells within GelMA or fibrin bioinks to fabricate vascularized synovial tissue analogs [

89]. High resolution printing (<50 µm) permits microvascular network formation and precise spatial organization of lining and sublining layers. GelMA-based bioinks have been successfully 3D-printed into microarchitectures that guide FLS alignment and vascular channel formation, facilitating studies of angiogenesis and cell invasion [

90]. Low-cost, 3D-printed droplet microfluidic instruments enable single-cell RNA-seq of disaggregated RA synovial tissue, identifying pathogenic fibroblast and immune subpopulations [

14,

91]. Such platforms facilitate routine clinical profiling of synovial biopsies and discovery of novel therapeutic targets.

3.5. Embedded Sensors and Real-Time Readouts

Embedding sensors into microengineered RA synovial membrane platforms can transform static models into dynamic, data-rich systems. Real-time readouts of pH, O

2, metabolites, cytokines, and mechanics yield unprecedented insight into RA pathophysiology and therapeutic responses [

92,

93]. The first three-dimensional synovium-on-a-chip platform integrated with non-invasive light scattering biosensing technology was developed to track the initiation and progression of pro-inflammatory synovial tissue responses, facilitating real-time, longitudinal analysis of dynamic tissue-level remodeling during pathological processes such as RA [

94]. This synovium-on-a-chip platform employs a microengineered hydrogel matrix combined with a dynamic particle suspension system, encapsulating synovial cells and functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles. In this study, researchers only used purified primary FLSs harvested from RA patients through at least five passages from immune cells like lymphocytes and resident synovial macrophages inside microfluidic devices. This microfluidic 3D light-scattering technology could discriminate the diseased phenotype as early as post-seeding day 2-3 instead of approximately 14 to 21 days post-seeding for conventional microtiter-based 3D synovial models with proliferation assays and cytokine assays such as ELISA. This innovative platform successfully recapitulated synovial inflammation, fibroblast activation, and extracellular matrix remodeling, offering a powerful tool for studying arthritis pathophysiology and drug responses under physiologically relevant conditions.

Table 1.

Comparative Evaluation of Microengineering Strategies to Recapitulate the RA Synovial Membrane.

Table 1.

Comparative Evaluation of Microengineering Strategies to Recapitulate the RA Synovial Membrane.

| Strategy |

Key Features |

Advantages |

Limitations |

Ref |

| Synovium-on-a-Chip |

Two-chamber PDMS device with FLS/macrophage layer and perfusable endothelial chamber |

Precise fluid control; Real-time imaging; Replication of synovial shear stress and gradients; Immune cell-endothelial-FLS crosstalk |

PDMS’s absorption; moderate throughput; Bubble formation; material adsorption; Limited long-term culture, Complex fabrication; specialized imaging |

[10,60,95,96] |

| Hydrogel-Based Micropatterned Scaffolds |

PEG/collagen hydrogels patterned with micro-wells for FLS + endothelial co-culture; static or low-flow conditions |

Accessible fabrication; tunable mechanics; supports basic co-culture assays |

Lacks dynamic shear; limited remodeling; incomplete ECM complexity |

[15,69,71,79,81] |

| Spheroid Microtissues |

Self-assembled RAFLS/macrophage spheroids in non-adherent microwells; can integrate with perfusion |

Mimics cellular condensation; easy high-throughput; relevant cell–cell contacts |

Lacks perfusion; limited diffusion; no mechanical cues |

[86] |

| Synovial Organoid |

3D encapsulation of Fibroblasts/HUVEC /Macrophages in a 3D fibrin-GelMA hydrogel system to investigate inflammation-mediated angiogenesis |

Captures 3D architecture; High-throughput imaging: Real-time visualization of angiogenesis through fluorescence imaging |

Limited mechanical loading; organoid heterogeneity; standardization challenges |

[96,97,98,99] |

| 3D Bioprinted Synovial Constructs |

Bioinks of decellularized ECM + FLS printed into defined geometries; optional perfusable channels |

Customizable geometry, tunable stiffness, patient-specific potential |

Avascular constructs; microvasculature printing limits; bioink optimization challenges |

[72,77,90,96] |

| Biosensor-Integrated Platforms |

Electrochemical/optical sensors embedded in microfluidic chips to monitor pH, O2, cytokines in real-time |

Real-time biochemical or optical monitoring; non-invasive; multiplex capability |

Sensor drift; integration complexity; potential interference |

[94,100] |

Figure 2.

Microengineering of rheumatoid arthritis synovial membrane models. Reproduced from [

13,

87,

88,

94]. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0).

Figure 2.

Microengineering of rheumatoid arthritis synovial membrane models. Reproduced from [

13,

87,

88,

94]. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 (CC BY 4.0).

4. Conclusion and Future Perspective

In this review, we have described recent progress in the development of microengineering RA synovial membrane models for better recapitulation of its microenvironment. Microengineering has yielded a suite of sophisticated in vitro models that capture the multifactorial nature of the RA synovial microenvironment. By integrating cellular heterogeneity, hydrogel-based scaffolds, biochemical gradients, mechanical forces, 3D bioprinting, organoids, and real-time biosensing, these platforms might overcome the limitations of traditional culture and animal models, offering unprecedented opportunities for mechanistic insight, drug discovery, and personalized therapy.

Despite substantial progress, numerous challenges still require scientific solutions. Due to variability in hydrogel composition, chip fabrication, and primary cell sources, we should establish consensus protocols and quality-control metrics. Incorporation of immune cells and tertiary lymphoid structures remains limited in the existing synovium-on-a-chip.

Therefore, future models should integrate adaptive immune components and lymphatics to make a perfect recapitulation of RA synovial microenvironment, by combining organoid and organ-on-a-chip technique. In addition, long-term culture (> weeks) under dynamic conditions to simulate chronic inflammation and tissue remodeling should be realized. In the near future, AI-based analysis of imaging and sensor data should be developed to identify predictive biomarkers and optimize device parameters on microengineering models.

Funding

This work was not supported by any grants

Acknowledgments

We would like to give thanks to Dr Hyok-Chol Choe for his help to edition of manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

None

References

- McInnes IB and Schett G. The Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. New England Journal of Medicine 2011; 365: 2205-2219. [CrossRef]

- Komatsu N and Takayanagi H. Mechanisms of joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis - immune cell-fibroblast-bone interactions. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2022; 18: 415-429. [CrossRef]

- Cheng M, Wei W and Chang Y. The Role and Research Progress of ACPA in the Diagnosis and Pathological Mechanism of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Human Immunology 2025; 86. [CrossRef]

- Finckh A, Gilbert B, Hodkinson B, Bae SC, Thomas R, Deane KD, Alpizar-Rodriguez D and Lauper K. Global epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2022; 18: 591-602. [CrossRef]

- Mueller AL, Payandeh Z, Mohammadkhani N, Mubarak SMH, Zakeri A, Bahrami AA, Brockmueller A and Shakibaei M. Recent Advances in Understanding the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis: New Treatment Strategies. Cells 2021; 10. [CrossRef]

- Han P, Liu XY, He J, Han LY and Li JY. Overview of mechanisms and novel therapies on rheumatoid arthritis from a cellular perspective. Frontiers in Immunology 2024; 15. [CrossRef]

- Alivernini S, Firestein GS and McInnes IB. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Immunity 2022; 55: 2255-2270. [CrossRef]

- Canavan M, Marzaioli V, McGarry T, Bhargava V, Nagpal S, Veale DJ and Fearon U. Rheumatoid arthritis synovial microenvironment induces metabolic and functional adaptations in dendritic cells. Clinical and Experimental Immunology 2020; 202: 226-238. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Su R, Wang H, Wu RH, Fan YX, Bin ZX, Gao C and Wang CH. The promise of Synovial Joint-on-a-Chip in rheumatoid arthritis. Frontiers in Immunology 2024; 15. [CrossRef]

- Li ZA, Sant S, Cho SK, Goodman SB, Bunnell BA, Tuan RS, Gold MS and Lin H. Synovial joint-on-a-chip for modeling arthritis: progress, pitfalls, and potential. Trends in Biotechnology 2023; 41: 511-527. [CrossRef]

- Reihs EI, Windhager R, Toegel S, Kiener HP, Ertl P and Rothbauer M. Development of an Animal-Product-Free Synovial Biochip Model as First Step Towards Multi-Tissue Crosstalk Models in Osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2022; 30: S89-S89. [CrossRef]

- Zheng FY, Fu FF, Cheng Y, Wang CY, Zhao YJ and Gu ZZ. Organ-on-a-Chip Systems: Microengineering to Biomimic Living Systems. Small 2016; 12: 2253-2282. [CrossRef]

- Thompson CL, Hopkins T, Bevan C, Screen HRC, Wright KT and Knight MM. Human vascularised synovium-on-a-chip: a mechanically stimulated, microfluidic model to investigate synovial inflammation and monocyte recruitment. Biomedical Materials 2023; 18. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson W, Donlin LT, Butler A, Rozo C, Bracken B, Rashidfarrokhi A, Goodman SM, Ivashkiv LB, Bykerk VP, Orange DE, Darnell RB, Swerdlow HP and Satija R. Single-cell RNA-seq of rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue using low-cost microfluidic instrumentation. Nature Communications 2018; 9. [CrossRef]

- Wu YQ, Ge Y, Wang ZS, Zhu Y, Tian TL, Wei J, Jin Y, Zhao Y, Jia Q, Wu J and Ge L. Synovium microenvironment-responsive injectable hydrogel inducing modulation of macrophages and elimination of synovial fibroblasts for enhanced treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2024; 22. [CrossRef]

- Horky D and Tichy F. The ultrastructure of equine synovial membrane. Acta Veterinaria Brno 1995; 64: 225-229. [CrossRef]

- Morris CJ, Hollywell CA, Scott DL, Farr M, Hawkins CF and Walton KW. Ultrastructure of the Synovial-Membrane in Seronegative Inflammatory Arthropathies. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1983; 76: 27-31. [CrossRef]

- Marsh LJ, Kemble S, Nisa PR, Singh R and Croft AP. Fibroblast pathology in inflammatory joint disease. Immunological Reviews 2021; 302: 163-183. [CrossRef]

- Rovenska E and Huttl S. Synovial-Membrane - the Ultrastructure of Lymphatic Microvasculature. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology 1986; 12-12.

- Widenfalk B. Sympathetic Innervation of Normal and Rheumatoid Synovial Tissue. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery 1991; 25: 31-33. [CrossRef]

- Cao M, Ong MTY, Yung PSH, Tuan RS and Jiang Y. Role of synovial lymphatic function in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2022; 30: 1186-1197. [CrossRef]

- Croft AP, Campos J, Jansen K, Turner JD, Marshall J, Attar M, Savary L, Wehmeyer C, Naylor AJ, Kemble S, Begum J, Dürholz K, Perlman H, Barone F, McGettrick HM, Fearon DT, Wei K, Raychaudhuri S, Korsunsky I, Brenner MB, Coles M, Sansom SN, Filer A and Buckley CD. Distinct fibroblast subsets drive inflammation and damage in arthritis. Nature 2019; 570: 246-251. [CrossRef]

- Kurowska-Stolarska M and Alivernini S. Synovial tissue macrophages in joint homeostasis, rheumatoid arthritis and disease remission. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2022; 18: 384-397. [CrossRef]

- Boutet MA, Courties G, Nerviani A, Le Goff B, Apparailly F, Pitzalis C and Blanchard F. Novel insights into macrophage diversity in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. Autoimmunity Reviews 2021; 20. [CrossRef]

- Micheroli R, Elhai M, Edalat S, Frank-Bertoncelj M, Bürki K, Ciurea A, MacDonald L, Kurowska-Stolarska M, Lewis MJ, Goldmann K, Cubuk C, Kuret T, Distler O, Pitzalis C and Ospelt C. Role of synovial fibroblast subsets across synovial pathotypes in rheumatoid arthritis: a deconvolution analysis. Rmd Open 2022; 8. [CrossRef]

- Cheng LY, Wang YY, Wu RH, Ding TT, Xue HW, Gao C, Li XF and Wang CH. New Insights From Single-Cell Sequencing Data: Synovial Fibroblasts and Synovial Macrophages in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in Immunology 2021; 12. [CrossRef]

- Edilova MI, Akram A and Abdul-Sater AA. Innate immunity drives pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Biomedical Journal 2021; 44: 172-182. [CrossRef]

- Klein T and Bischoff R. Physiology and pathophysiology of matrix metalloproteases. Amino Acids 2011; 41: 271-290. [CrossRef]

- Fraser JRE, Laurent TC and Laurent UBG. Hyaluronan: Its nature, distribution, functions and turnover. Journal of Internal Medicine 1997; 242: 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Mayston V, Mapp PI, Davies PG and Revell PA. Fibronectin in the Synovium of Chronic Inflammatory Joint Disease. Rheumatology International 1984; 4: 129-133. [CrossRef]

- Midwood K, Sacre S, Piccinini AM, Inglis J, Trebaul A, Chan E, Drexler S, Sofat N, Kashiwagi M, Orend G, Brennan F and Foxwell B. Tenascin-C is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4 that is essential for maintaining inflammation in arthritic joint disease. Nature Medicine 2009; 15: 774-U711. [CrossRef]

- Iozzo RV and Schaefer L. Proteoglycan form and function: A comprehensive nomenclature of proteoglycans. Matrix Biology 2015; 42: 11-55. [CrossRef]

- Burrage PS, Mix KS and Brinckerhoff CE. Matrix metalloproteinases: Role in arthritis. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2006; 11: 529-543. [CrossRef]

- Debelle L and Tamburro AM. Elastin: molecular description and function. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology 1999; 31: 261-272. [CrossRef]

- Madsen SF, Sinkeviciute D, Karsdal M, Bay-Jensen AC and Thudium C. Cytokine Driven ECM Production Is Highly Dependent on Disease Drivers in Fibroblastlike Synoviocytes. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2023; 82: 1221-1221. [CrossRef]

- Erin Nevius, Ana Cordeiro Gomes and Pereira JP. A comprehensive review of inflammatory cell migration in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016; 51: 20. [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz MJ. New potential therapeutic approaches targeting synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis. Biochemical Pharmacology 2021; 194. [CrossRef]

- Mahvash Sadeghi, Jalil Tavakol Afshari, Afsane Fadaee, Fatemeh Kheradmand, Sajad Dehnavi and Mojgan Mohammadi. Exosomal miRNAs involvement in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Heliyon 2025; 11. [CrossRef]

- Quiñonez-Flores CM, González-Chávez SA and Pacheco-Tena C. Hypoxia and its implications in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Biomedical Science 2016; 23. [CrossRef]

- Guo X and Chen GJ. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Is Critical for Pathogenesis and Regulation of Immune Cell Functions in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in Immunology 2020; 11. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Fan DP, Cao XX, Ye QB, Wang Q, Zhang MX and Xiao C. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in the Rheumatoid Arthritis-Associated Synovial Microenvironment. Antioxidants 2022; 11. [CrossRef]

- Caire R, Audoux E, Courbon G, Michaud E, Petit C, Dalix E, Chafchafi M, Thomas M, Vanden-Bossche A, Navarro L, Linossier MT, Peyroche S, Guignandon A, Vico L, Paul S and Marotte H. YAP/TAZ: Key Players for Rheumatoid Arthritis Severity by Driving Fibroblast Like Synoviocytes Phenotype and Fibro-Inflammatory Response. Frontiers in Immunology 2021; 12. [CrossRef]

- Piluso S, Li Y, Abinzano F, Levato R, Teixeira LM, Karperien M, Leijten J, van Weeren R and Malda J. Mimicking the Articular Joint with Models. Trends in Biotechnology 2019; 37: 1063-1077. [CrossRef]

- Janczi T, Böhm B, Fehrl Y, Hartl N, Behrens F, Kinne RW, Burkhardt H and Meier F. Mechanical forces trigger invasive behavior in synovial fibroblasts through N-cadherin/ADAM15-dependent modulation of LncRNA H19. Scientific Reports 2025; 15. [CrossRef]

- Neofotistou-Themeli E, Goutakoli P, Chanis T, Semitekolou M, Sevdali E and Sidiropoulos P. Fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis: novel roles in joint inflammation and beyond. Frontiers in Medicine 2025; 11. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen A, Lastowska A, Bollmann M, Kourmoulakis S, van der Plas CE, Ekwall AKH, Zaiss DM, Firestein GS and Svensson MND. Role of Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells in the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2023; 75: 1596-1597.

- Cua DJ and Tato CM. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system (vol 10, pg 479, 2010). Nature Reviews Immunology 2010; 10: 612-612. [CrossRef]

- Nanke Y. The Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis Breakthroughs in Molecular Mechanisms 1 and 2. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023; 24. [CrossRef]

- Komatsu N and Takayanagi H. Inflammation and bone destruction in arthritis: synergistic activity of immune and mesenchymal cells in joints. Frontiers in Immunology 2012; 3. [CrossRef]

- Scherer HU, Huizinga TWJ, Krönke G, Schett G and Toes REM. The B cell response to citrullinated antigens in the development of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature Reviews Rheumatology 2018; 14: 157-169. [CrossRef]

- Tu JJ, Hong WM, Zhang PY, Wang XM, Körner H and Wei W. Ontology and Function of Fibroblast-Like and Macrophage-Like Synoviocytes: How Do They Talk to Each Other and Can They Be Targeted for Rheumatoid Arthritis Therapy? Frontiers in Immunology 2018; 9. [CrossRef]

- Tu JJ, Huang W, Zhang WW, Mei JW and Zhu C. Two Main Cellular Components in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Communication Between T Cells and Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes in the Joint Synovium. Frontiers in Immunology 2022; 13. [CrossRef]

- Feng YH, Mei LY, Wang MJ, Huang QC and Huang RY. Anti-inflammatory and Pro-apoptotic Effects of 18beta-Glycyrrhetinic Acid and Models of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021; 12. [CrossRef]

- Donlin LT, Jayatilleke A, Giannopoulou EG, Kalliolias GD and Ivashkiv LB. Modulation of TNF-Induced Macrophage Polarization by Synovial Fibroblasts. Journal of Immunology 2014; 193: 2373-2383. [CrossRef]

- Chwastek J, Kedziora M, Borczyk M, Korostynski M and Starowicz K. Mimicking the Human Articular Joint with In Vitro Model of Neurons-Synoviocytes Co-Culture. International Journal of Stem Cells 2024; 17: 91-98. [CrossRef]

- Li K, Zhu Y, Alini M, Stoddart MJ, Grad S and Li Z. Establishment of a Coculture System with Osteochondral and Synovial Explants as an Ex Vivo Inflammatory Osteoarthritis Model. European Cells & Materials 2024; 47: 15-29. [CrossRef]

- Chan MWY, Gomez-Aristizábal A, Mahomed N, Gandhi R and Viswanathan S. A tool for evaluating novel osteoarthritis therapies using multivariate analyses of human cartilage-synovium explant co-culture. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2022; 30: 147-159. [CrossRef]

- Wu J, Li Q, Jin L, Qu Y, Liang BB, Zhu XT, Du HY, Jie LG and Yu QH. Kirenol Inhibits the Function and Inflammation of Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes in Rheumatoid Arthritis in vitro and in vivo. Frontiers in Immunology 2019; 10. [CrossRef]

- Wu QR, Liu JF, Wang XH, Feng LY, Wu JB, Zhu XL, Wen WJ and Gong XQ. Organ-on-a-chip: recent breakthroughs and future prospects. Biomedical Engineering Online 2020; 19. [CrossRef]

- Wampler Muskardin T MC, Ma B, Van Buren K, Niewold T, Chen W. Vascularized ‘Synovium-on-a-Chip’ – A Novel and Adaptable Model for Dissecting Inflammatory Biology Underlying Rheumatoid Arthritis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021; 73.

- Mirazi H and Wood ST. Microfluidic Co-Culture for Modeling Human Joint Inflammation in Osteoarthritis Research. bioRxiv 2025; 19. [CrossRef]

- Tibbe MP, Leferink AM, van den Berg A, Eijkel JCT and Segerink LI. Microfluidic Gel Patterning Method by Use of a Temporary Membrane for Organ-On-Chip Applications. Advanced Materials Technologies 2018; 3. [CrossRef]

- Piluso S, Li Y, Texeira LM, Padmanaban P, Rouwkema. J, Leijten J, Weeren Rv, Karperien M and Malda J. Effect of fluid flow-induced shear stress on the behavior of synovial fibroblasts in a bioinspired synovium-on-chip model(In Press). Journal of Cartilage & Joint Preservation 2025; [CrossRef]

- Bell RD, Rahimi H, Kenney HM, Lieberman AA, Wood RW, Schwarz EM and Ritchlin CT. Altered Lymphatic Vessel Anatomy and Markedly Diminished Lymph Clearance in Affected Hands of Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatology 2020; 72: 1447-1455. [CrossRef]

- Henderson AR, Choi H and Lee E. Blood and Lymphatic Vasculatures On-Chip Platforms and Their Applications for Organ-Specific In Vitro Modeling. Micromachines 2020; 11. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti S, Hore Z, Pattison LA, Lalnunhlimi S, Bhebhe CN, Callejo G, Bulmer DC, Taams LS, Denk F and Smith ES. Sensitization of knee-innervating sensory neurons by tumor necrosis factor-α-activated fibroblast-like synoviocytes: an in vitro, coculture model of inflammatory pain. Pain 2020; 161: 2129-2141. [CrossRef]

- Li YX, Sun K, Shao Y, Wang C, Xue F, Chu CL, Gu ZZ, Chen ZZ and Bai J. Next-Generation Approaches for Biomedical Materials Evaluation: Microfluidics and Organ-on-a-Chip Technologies. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2025; 14. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira IM, Fernandes DC, Cengiz IF, Reis RL and Oliveira JM. Hydrogels in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: drug delivery systems and artificial matrices for dynamic in vitro models. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine 2021; 32. [CrossRef]

- Ansari M, Darvishi A and Sabzevari A. A review of advanced hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2024; 12. [CrossRef]

- Fang WZ, Yang M, Liu M, Jin YW, Wang YH, Yang RX, Wang Y, Zhang KL and Fu Q. Review on Additives in Hydrogels for 3D Bioprinting of Regenerative Medicine: From Mechanism to Methodology. Pharmaceutics 2023; 15. [CrossRef]

- Wang TY, Huang C, Fang ZY, Bahatibieke A, Fan DP, Wang X, Zhao HY, Xie YJ, Qiao K, Xiao C and Zheng YD. A dual dynamically cross-linked hydrogel promotes rheumatoid arthritis repair through ROS initiative regulation and microenvironment modulation-independent triptolide release. Materials Today Bio 2024; 26. [CrossRef]

- Amelia Heslington, Catharien M. U. Hilkens, Ana Marina Ferreira and Melo P. Functional Synovium-Based 3D Models in the Context of Human Disease and Inflammation. Advanced Nanobiomed Research 2025; [CrossRef]

- Ali A, Jori C, Kumar A and Khan R. Recent trends in stimuli-responsive hydrogels for the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023; 89. [CrossRef]

- Wang YP, Wang JR, Ma MZ, Gao R, Wu Y, Zhang CN, Huang PS, Wang WW, Feng ZJ and Gao JB. Hyaluronic-Acid-Nanomedicine Hydrogel for Enhanced Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis by Mediating Macrophage-Synovial Fibroblast Cross-Talk. Biomaterials Research 2024; 28. [CrossRef]

- Spearman BS, Agrawal NK, Rubiano A, Simmons CS, Mobini S and Schmidt CE. Tunable methacrylated hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels as scaffolds for soft tissue engineering applications. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A 2020; 108: 279-291. [CrossRef]

- Meagan Makarczyk, Matias Preisegger, Qi Gao, Bruce Bunnell, Stuart Goodman, Gold Michael and Lin H. An innervated synovium-cartilage chip for modeling knee joint inflammatiom and associated pain. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2025; 33: S468-S469.

- Lin JT, Sun AR, Li J, Yuan TY, Cheng WX, Ke LQ, Chen JH, Sun W, Mi SL and Zhang P. A Three-Dimensional Co-Culture Model for Rheumatoid Arthritis Pannus Tissue. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021; 9. [CrossRef]

- Bisconti F, Vilardo B, Corallo G, Scalera F, Gigli G, Chiocchetti A, Polini A and Gervaso F. An Assist for Arthritis Studies: A 3D Cell Culture of Human Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes by Encapsulation in a Chitosan-Based Hydrogel. Advanced Therapeutics 2024; 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang HJ, Zhou ZY, Zhang FJ and Wan C. Hydrogel-Based 3D Bioprinting Technology for Articular Cartilage Regenerative Engineering. Gels 2024; 10. [CrossRef]

- Zhao Y, Song SL, Wang DD, Liu H, Zhang JM, Li ZH, Wang JC, Ren XZ and Zhao YL. Nanozyme-reinforced hydrogel as a HO-driven oxygenerator for enhancing prosthetic interface osseointegration in rheumatoid arthritis therapy. Nature Communications 2022; 13. [CrossRef]

- Wu YQ, Wang ZS, Ge Y, Zhu Y, Tian TL, Wei J, Jin Y, Zhao Y, Jia Q, Wu J and Ge L. Microenvironment Responsive Hydrogel Exerting Inhibition of Cascade Immune Activation and Elimination of Synovial Fibroblasts for Rheumatoid Arthritis Therapy. Journal of Controlled Release 2024; 370: 747-762. [CrossRef]

- Guillame-Gentil O, Semenov O, Roca AS, Groth T, Zahn R, Vörös J and Zenobi-Wong M. Engineering the Extracellular Environment: Strategies for Building 2D and 3D Cellular Structures. Advanced Materials 2010; 22: 5443-5462. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama K. Progress and Future Prospects of Clinical Research on Scaffold-Free Biofabrication by the Kenzan Method. Tissue Engineering Part A 2022; 28: S275-S275.

- Chen H, Xue HQ, Zeng HX, Dai MH, Tang CX and Liu LL. 3D printed scaffolds based on hyaluronic acid bioinks for tissue engineering: a review. Biomaterials Research 2023; 27. [CrossRef]

- Kiener HP, Watts GFM, Cui YJ, Wright J, Thornhill TS, Sköld M, Behar SM, Niederreiter B, Lu J, Cernadas M, Coyle AJ, Sims GP, Smolen J, Warman ML, Brenner MB and Lee DM. Synovial Fibroblasts Self-Direct Multicellular Lining Architecture and Synthetic Function in Three-Dimensional Organ Culture. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2010; 62: 742-752. [CrossRef]

- Philippon EML, van Rooijen LJE, Khodadust F, van Hamburg JP, van der Laken CJ and Tas SW. A novel 3D spheroid model of rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue incorporating fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and macrophages. Frontiers in Immunology 2023; 14. [CrossRef]

- Wang XC, He JX, Zhang Q, He J and Wang QW. Constructing a 3D co-culture synovial tissue model for rheumatoid arthritis research. Materials Today Bio 2025; 31. [CrossRef]

- Rothbauer M, Byrne RA, Schobesberger S, Calvo IO, Fischer A, Reihs EI, Spitz S, Bachmann B, Sevelda F, Holinka J, Holnthoner W, Redl H, Toegel S, Windhager R, Kiener HP and Ertl P. Establishment of a human three-dimensional chip-based chondro-synovial coculture joint model for reciprocal cross talk studies in arthritis research. Lab on a Chip 2021; 21: 4128-4143. [CrossRef]

- Badillo-Mata JA, Camacho-Villegas TA and Lugo-Fabres PH. 3D Cell Culture as Tools to Characterize Rheumatoid Arthritis Signaling and Development of New Treatments. Cells 2022; 11. [CrossRef]

- Petretta M, Villata S, Scozzaro MP, Roseti L, Favero M, Napione L, Frascella F, Pirri CF, Grigolo B and Olivotto E. In Vitro Synovial Membrane 3D Model Developed by Volumetric Extrusion Bioprinting. Applied Sciences-Basel 2023; 13. [CrossRef]

- Jiang ZQ, Shi HR, Tang XY and Qin JL. Recent advances in droplet microfluidics for single-cell analysis. Trac-Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023; 159. [CrossRef]

- Clarke GA, Hartse BX, Asli AEN, Taghavimehr M, Hashemi N, Shirsavar MA, Montazami R, Alimoradi N, Nasirian V, Ouedraogo LJ and Hashemi NN. Advancement of Sensor Integrated Organ-on-Chip Devices. Sensors 2021; 21. [CrossRef]

- Yoojeong Kim, Erick C. Chica-Carrillo and Lee HJ. Microfabricated sensors for non-invasive, real-time monitoring of organoids. Micro and Nano Systems Letters 2024; 12. [CrossRef]

- Rothbauer M, Höll G, Eilenberger C, Kratz SRA, Farooq B, Schuller P, Calvo IO, Byrne RA, Meyer B, Niederreiter B, Küpcü S, Sevelda F, Holinka J, Hayden O, Tedde SF, Kiener HP and Ertl P. Monitoring tissue-level remodelling during inflammatory arthritis using a three-dimensional synovium-on-a-chip with non-invasive light scattering biosensing. Lab on a Chip 2020; 20: 1461-1471. [CrossRef]

- Mondadori C, Palombella S, Salehi S, Talò G, Visone R, Rasponi M, Redaelli A, Sansone V, Moretti M and Lopa S. Recapitulating monocyte extravasation to the synovium in an organotypic microfluidic model of the articular joint. Biofabrication 2021; 13. [CrossRef]

- Khan I, Prabhakar A, Delepine C, Tsang H, Pham V and Sur M. A low-cost 3D printed microfluidic bioreactor and imaging chamber for live-organoid imaging. Biomicrofluidics 2021; 15. [CrossRef]

- Calvo IO, Byrne RA, Karonitsch T, Niederreiter B, Kartnig F, Alasti F, Holinka J, Ertl P and Kiener HP. 3D Synovial Organoid Culture Reveals Cellular Mechanisms of Tissue Formation and Inflammatory Remodelling. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2017; 76: A49-A50. [CrossRef]

- Lin X, Lin TY, Wang XC, He JX, Gao X, Lyu S, Wang QW and Chen J. Sesamol serves as a p53 stabilizer to relieve rheumatoid arthritis progression and inhibits the growth of synovial organoids. Phytomedicine 2023; 121. [CrossRef]

- Qi Gao, Xiurui Zhang, Meagan J. Makarcyzk, Laurel Elizabeth Wong, Madison Sidney Virgil Quig, Issei Shinohara, Masatoshi Murayama, Simon Kwoon-Ho Chow, Bruce A. Bunnell, Hang Lin and Goodman SB. Macrophage phenotypes modulate neoangiogenesis and fibroblast profiles in synovial-like organoid cultures. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 2025; 33: 11. [CrossRef]

- Tawade P and Mastrangeli M. Integrated Electrochemical and Optical Biosensing in Organs-on-Chip. Chembiochem 2024; 25. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).