Submitted:

27 August 2025

Posted:

28 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

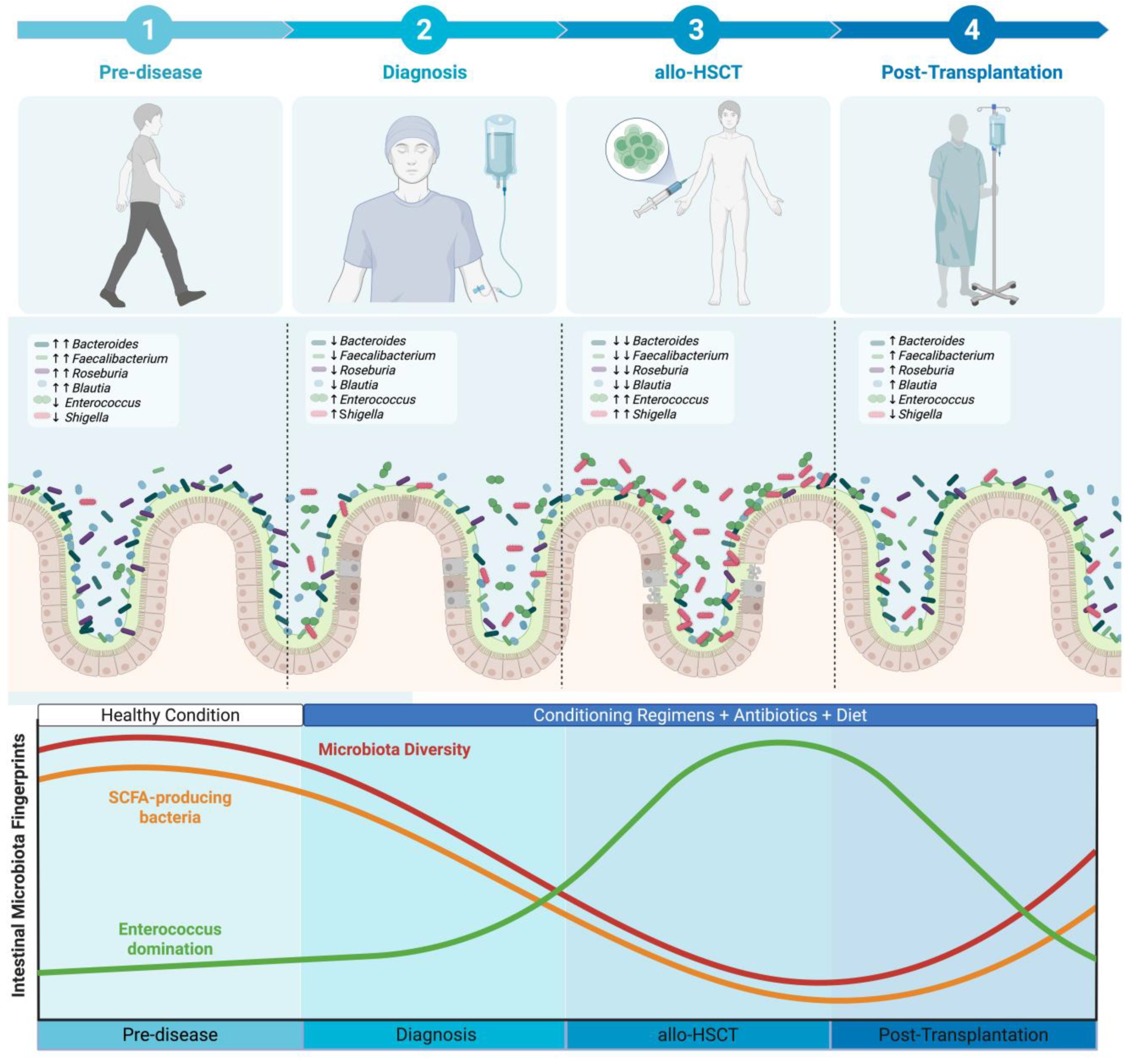

2. The Dynamics of Intestinal Microbiota Through the Patient Journey

3. Intestinal Microbiota Fingerprints Prior to Allo-HSCT

| Outcomes |

Author, year N |

Finding |

| Overall Survival[12,13,17] | Peled 2020[13] 606 |

↓Overall Mortality Higher alpha diversity prior to allo-HSCT was associated with a lower risk of mortality (HR 0.41; 95% CI 0.24-0.71) |

| Liu 2017[12] 57 |

↓Overall Mortality Patients with higher phylogenetic diversity had lower overall mortality rates (HR 0.37; 95% CI 0.18-0.77; p = 0.008) |

|

| Masetti 2023[17]β 90 |

↑Overall Survival Patients with higher intestinal diversity exhibited a higher probability of overall survival (88.9% ± 5.7% vs. 62.7% ± 8.2%; p = 0.011). |

|

| Transplantation-related mortality[13] | Peled 2020[13] 606 |

↓Transplant-related mortality Higher alpha diversity prior to allo-HSCT was associated with a lower risk of transplant-related mortality (HR 0.44; 95% CI 0.22-0.87). |

| aGvHD[17] | Masetti 2023[17]β 90 |

↓aGvHD The cumulative incidence of grade 2 to 4 aGvHD was significantly lower in the higher diversity group than in the lower diversity group (20.0% ± 6.0% [SE] vs 44.4% ± 7.4% [SE]; p = .017). The cumulative incidence of grade 3 to 4 aGvHD was significantly lower in the higher diversity group than in the lower diversity group (2.2% ± 2.2% [SE] vs 20.0% ± 6.0% [SE]; p = .007). |

| Biagi 2019[37] 36 |

The diversity between pre-HSCT samples were greater in individuals who developed intestinal GvHD (0.86 ± 0.15) than in individuals without GvHD (0.72 ± 0.15, p = 0.001) and individuals who developed less severe skin GvHD (0.77 ± 0.15, p = 0.02). |

4. Intestinal Microbiota Fingerprints During Allo-HSCT

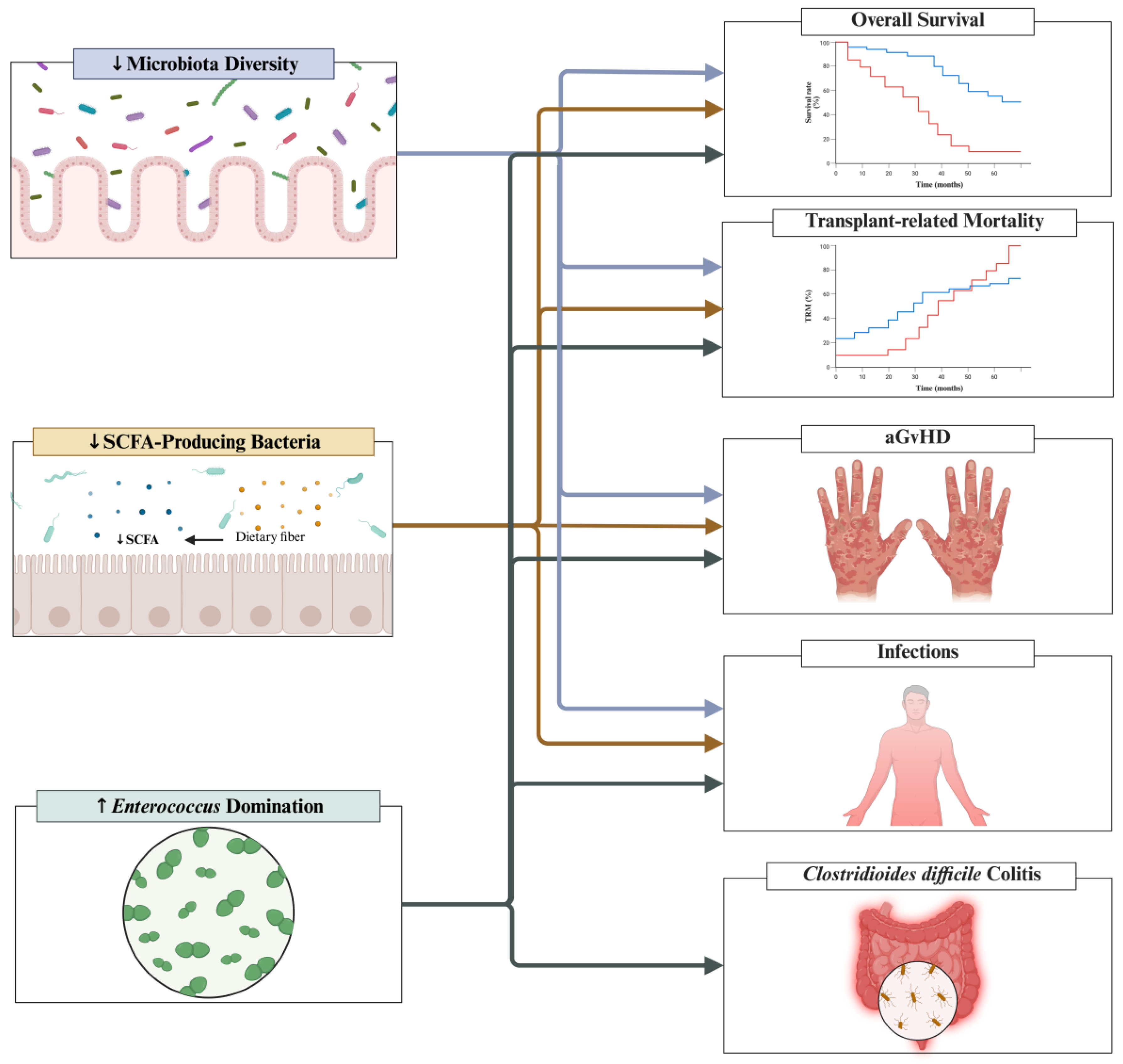

4.1. Intestinal Diversity and Implications to Clinical Outcomes

| Outcome |

Author, year N Sample Timing |

Finding |

| Overall Survival[13,19,20] | Peled 2020[13] 704 At engraftment |

↑Overall Survival Patients were categorized into low- vs. high- diversity groups based on the median value. High diversity at engraftment was associated with a significant improve in overall survival (HR 0.75; 95% CI 0.58-0.96). This association was also identified after multivariable adjustment for age, intensity of the conditioning regimen, graft source and HCT-CI (HR 0.71; 95% CI 0.55-0.92). When considered as a continuous variable, high intestinal diversity was also associated with improved overall survival in both univariate (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.37-0.91) and multivariate (HR 0.50; 95% CI 0.31-0.80) analysis. |

| Taur 2014[19] 80 At engraftment |

↑Overall Survival Overall survival at 3 years was 36%, 60% and 67% for low, intermediate and high diversity groups (p = 0.19). Patients with low diversity (inverse Simpson <2) were 3 times more likely to die within the follow-up when compared to those with higher microbial diversity (HR 3.13, 95% CI 1.39-7.98; p=0.05; adjusted HR 2.56; 95% CI 1.03-7.23; p = 0.42). Low diversity showed a strong effect on mortality after multivariate adjustment for other clinical predictors (transplant related mortality: adjusted hazard ratio, 5.25; p = 0.014). |

|

| Gu 2022[20] 86 At engraftment |

↑Overall Survival Patients were categorized into low- vs. high- diversity groups based on the median Shannon Index value. When compared to patients with low diversity, patients with high diversity had significantly higher two-year overall survival (83.7% vs. 60.6%; p=0.026). After adjusting for disease risk, pretransplant comorbidity, and previous chemotherapy, low intestinal diversity was an independent predictor of all-cause death (HR 2.62; 95% CI 1.06-6.49; p = 0.038) in a multivariate analysis. |

|

| Transplantation-related mortality[19,20,36] | Taur 2014[19] 80 At engraftment |

↑Transplant-related mortality Transplant-related mortality was 9%, 23%, and 53% for high, intermediate and low diversity groups, respectively (p = 0.03). Patients with low diversity (inverse Simpson <2) were 7.5 times more likely to experience transplant-related mortality within the follow-up when compared to those with higher microbial diversity (HR 7.54; 95% CI 2.12-47.88; p=0.001; adjusted hazard ratio, 5.25; 95% CI 1.36-35.07; p = 0.014). |

| Gu 2022[20] 86 At engraftment |

↑Transplantation-related Mortality When compared to patients in the high diversity group, patients in the low-diversity group had higher estimated 2-year transplanted related mortality (20.0% vs. 4.7%; p = 0.04). After adjusting for pretransplant comorbidity, disease status at the time of allo-HSCT and previous chemotherapy, low intestinal diversity was an independent predictor of transplant-related mortality (HR 4.95; 95% CI 1.03-23.76; p = 0.046). |

|

| Galloway-Pena 2019[36] 44 At engraftment |

↓Transplantation-related Mortality The Shannon diversity index at the time of engraftment was significantly associated with TRM (coefficient = -1.44; p = 0.02) |

|

| aGvHD[16,19,22,24,36,42] | Jenq 2015[24] 64 D+12 |

↓GvHD-related mortality Increased intestinal diversity was associated with reduced GvHD-related mortality (p = 0.005). |

| Mancini 2017[16] 96 D+10 |

↑aGvHD Decreased intestinal diversity at D+10 was associated with increased risk of early onset aGvHD (OR 7.833; 95% CI 2.141-28.658; p = 0.038). |

|

| Taur 2014[19] 80 At engraftment |

↑GvHD-related mortality GvHD-related mortality was higher in patients with low diversity (p = 0.018). |

|

| Payen 2020[22] 70 At the onset of GvHD |

↑aGvHD severity Patients with severe aGvHD had significantly lower indexes of alpha diversity: Chao1 (p = 0.039) and Simpson (p = 0.013) |

|

| Golob 2017[42] 66 At engraftment Weekly samples from prior to allo-HSCT until D+100 |

↑aGvHD severity Patients with severe aGvHD had a significantly lower alpha diversity index compared to both the control group and patients without severe aGvHD (p < 0.05). This finding was statistically significant when analyzing all stool samples collected over the allo-HSCT and when analyzing only samples collected at the engraftment period. |

|

| Galloway-Pena 2019[36] 44 At engraftment |

The Shannon diversity index at the time of engraftment was significantly associated with the incidence of aGvHD (P = 0.02) | |

| Infections[19] | Taur 2014[19] 80 At engraftment |

↑Infection-related mortality Infection related mortality was higher in patients with low diversity (p = 0.018). |

4.2. SCFA-Producting Bacteria and Implications to Clinical Outcomes

| Outcomes |

Author, year N Sample Timing |

Finding |

| Overall Survival[24] | Jenq 2015[24] 64 D+12 |

↑Overall Survival Increased Blautia abundance was strongly associated with improved overall survival (p < 0.001). |

|

Transplantation-related Mortality[26] |

Meedt, 2022[26] 201 aGvHD onset // D+30 |

↑Transplant-related Mortality Low BCoAT copy numbers at D+30/GvHD were significantly associated with increased risk of transplant related mortality (HR 4.459; 95% CI 1.1018-19.530; p = 0.047). |

| aGvHD[21,22,24,26,38] | Jenq 2015[24] 64 D+12 |

↓GvHD-related mortality By using a taxonomic discovery analysis, increase in the genus Blautia was significantly associated with reduced GvHD-related mortality (p = 0.01). By stratifying patients based on Blautia median abundance, patients with higher abundance had reduced GvHD-related mortality (p = 0.04). In a multivariable analysis, Blautia abundance remained associated with GvHD-related mortality (HR 0.18; 95% CI 0.05-0.63; p = 0.007). ↓Refractory GvHD Increased Blautia abundance was associated with reduced development of acute GvHD that required treatment with systemic corticosteroids or was steroid refractory (p = 0.01). In a multivariable analysis, Blautia abundance remained associated with refractory GvHD (HR 0.3; 95% CI 0.14-0.64; p = 0.002). ↓Liver GvHD Increased Blautia abundance was associated with reduced liver GvHD (p = 0.02). |

| Payen 2020[22] 70 aGvHD onset |

↓aGvHD severity When compared to controls (patients undergoing allo-HSCT without GvHD), patients with severe GvHD had a significant depletion of the Blautia coccoides group (p = 0.07). Similar findings were found when compared to patients with mild aGvHD (p = 0.036). ↓aGvHD severity When compared to controls (patients undergoing allo-HSCT without GvHD), patients with severe GvHD had a significant depletion of Anaerostipes (p = 0.015). ↓aGvHD severity When compared to controls (patients undergoing allo-HSCT without GvHD), patients with severe GvHD had a significant depletion of Faecalibacterium (p = 0.011). ↓aGvHD severity When compared to controls (patients undergoing allo-HSCT without GvHD), patients with severe GvHD had a significant depletion of Lachnoclostridium (p = 0.019). ↓GvHD severity When compared to controls (patients undergoing allo-HSCT without GvHD), patients with severe GvHD had significantly lower levels of total SCFAs (12.50 vs. 2.42; p = 0.0003), acetate (8.87 vs. 2.15; p = 0.002), butyrate (1.11 vs. 0.06; p = 0.001), and propionate (2.33 vs. 0.10; p = 0.0009). |

|

| Romick-Rosendale 2018[21] 42 D+14 |

↓GvHD When compared to patients that developed GvHD, patients without GvHD had significantly higher levels of butyrate (1.77 vs. 0.0550; p = 0.0142), propionate (6.63 vs. 0.208; p = 0.0108) and acetate (39.6 vs. 7.92; p = 0.047) at samples collected at D+14. |

|

| Meedt, 2022[26] 201 aGvHD onset // D+30 |

↑GI-GvHD severity Low BCoAT copy numbers at GvHD onset were correlated with GI-GvHD severity (p = 002; r = 0.3). ↑GI-GvHD Patients with GI-GvHD had lower BCoAT copy numbers than patients with other organs manifestations (0 copies vs. 3.16 x 106 copies; p = 0.006; r = 0.3). ↑GvHD-related Mortality Patients with low BCoAT copy numbers displayed significantly higher GvHD-associated mortality rate than those with high BCoAT concentrations (p = 0.04). |

|

| Artacho 2024[38] 70 Prior to allo-HSCT and Engraftment |

↑GvHD A significant decrease in acetate levels was detected in patients who developed GvHD (log2FC median = -2.36; p = 0.049). |

|

| Infections[25] | Haak 2018[25] 360 At engraftment |

↓LRTI The incidence of viral LRTI at 180 days was 17.3% and 16.1% for groups in which butyrate-producing bacteria were absent or low, respectively, and 3.2% for the high butyrate-producing group (p = 0.005). Patients with the highest abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria were independently associated with a fivefold decrease in risk of viral LRTI (HR 0.22; 95% CI 0.04-0.69; p = 0.06). |

4.3. Intestinal Domination and Implications to Clinical Outcomes

| Outcomes |

Autor, year N Sample Timing |

Implication |

| Overall Survival[18,28] | Messina 2024[18] 98 Stools were collected once prior to HSCT, weekly until D+30 and then at days D+45, D+90 and D+180 |

↓Overall survival Patients with Enterococcus domination had decreased overall survival (p = 0.01). Overall survival Bacteroides domination at any time point was not significantly associated with overall survival (p = 0.08). Akkermansia domination at any time point was not significantly associated with overall survival (p = 0.14). Blautia domination at any time point was not significantly associated with overall survival (p value NR). Lactobacillus domination was not significantly associated with overall survival (p = 0.52). Streptococcus domination was not significantly associated with overall survival (p = 0.70). |

| Stein-Thoeringer 2019[28] 1325 Samples were collected in the early post-transplant period (D0 to D+21) |

↓Overall survival Patients with Enterococcus domination in the early-post transplant period had significantly reduced overall survival in univariate analysis (HR 1.97; 95% CI 1.45 – 2.66; p < 0.001). This finding remained significant in a multivariate analysis adjusted for graft source, age, conditioning intensity, gender and underlying disease (HR 2.06; 95% CI 1.50-2.82; p < 0.0001). |

|

| Transplantation-related Mortality[18] | Messina 2024[18] 98 Stools were collected once prior to HSCT, weekly until D+30 and then at days D+45, D+90 and D+180 |

↑Treatment-related mortality Patients with Enterococcus domination had increased treatment-related mortality (p = 0.02). |

| aGvHD[28] | Stein-Thoeringer 2019[28] 1325 Samples were collected in the early post-transplant period (D0 to D+21) |

↑GvHD-related mortality Patients with Enterococcus domination in the early-post transplant period had significantly increased GvHD-related mortality in univariate analysis (HR 2.04; 95% CI 1.18-3.52; p = 0.05). This finding remaining significant in a multivariate analysis adjusted for graft source, age, conditioning intensity, gender and underlying disease (HR 2.60; 95% CI 1.46-4.62; p < 0.01). ↑GvHD severity (grade 2-4) Patients with Enterococcus domination in the early-post transplant period had significantly increased GvHD severity (grade 2-4) in univariate analysis (HR 1.44; 95% CI 1.10-1.88; p < 0.01). This finding remaining significant in a multivariate analysis adjusted for graft source, age, conditioning intensity, gender and underlying disease (HR 1.32; 95% CI 1.00-1.75; p < 0.05). |

| Infections[18,30] | Messina 2024[18] 98 Stools were collected once prior to HSCT, weekly until D+30 and then at days D+45, D+90 and D+180 |

↑BSI Patients with Enterococcus domination at any time point had increased risk for BSI (63% vs. 35%; p = 0.01). |

| Taur 2012[30] 94 Prior to allo-HSCT After allo-HSCT (until D+35) |

↑BSI Patients with Enterococcus domination had a 9-fold increased risk of VRE bacteremia (HR 9.35; 95% CI 2.43-45.44; p = 0.001). |

|

| Taur 2012[30] 94 Prior to allo-HSCT After allo-HSCT (until D+35) |

↑BSI Patients with Proteobacteria domination had a 5-fold increased risk of gram-negative bacteremia (HR 5.46; 95% CI 1.03-19.91; p = 0.047). |

|

| Clostridioides difficile colitis[18] | Messina 2024[18] 98 Stools were collected once prior to HSCT, weekly until D+30 and then at days D+45, D+90 and D+180 |

↑Clostridioides difficile colitis Patients with Enterococcus domination at any time point had increased risk for BSI (34% vs. 16%; p = 0.04). |

| Other[18] | Messina 2024[18] 98 Stools were collected once prior to HSCT, weekly until D+30 and then at days D+45, D+90 and D+180 |

↑Relapse-related mortality Patients with Enterococcus domination had increased relapse-related mortality (p = 0.08). |

5. Strategies to Modulate the Intestinal Microbiota During Allo-HSCT

6. Challenges in Translating Intestinal Microbiota Research into Allo-HSCT Clinical Practice

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Allo-HSCT | Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

| BSI | Bloodstream infection |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| D | Day |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FMT | Fecal microbiota transplantation |

| LRTI | Lower respiratory tract infection |

| SCFA | Short-chain fatty acid |

| SE | Standard error |

| STORMS | Strengthening The Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies |

| GvHD | Graft versus host disease |

| GFO | Glutamine, fiber and oligosaccharides |

| HR | Hazard Ratio |

| TRM | Transplantation-related mortality |

References

- Hill, G.R.; Betts, B.C.; Tkachev, V.; Kean, L.S.; Blazar, B.R. Current Concepts and Advances in Graft-Versus-Host Disease Immunology. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 39, 19–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, J.L.; Levine, J.E.; Reddy, P.; Holler, E. Graft-versus-Host Disease. The Lancet 2009, 373, 1550–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagasia, M.; Arora, M.; Flowers, M.E.D.; Chao, N.J.; McCarthy, P.L.; Cutler, C.S.; Urbano-Ispizua, A.; Pavletic, S.Z.; Haagenson, M.D.; Zhang, M.-J.; et al. Risk Factors for Acute GVHD and Survival after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Blood 2012, 119, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilett, E.E.; Jørgensen, M.; Noguera-Julian, M.; Nørgaard, J.C.; Daugaard, G.; Helleberg, M.; Paredes, R.; Murray, D.D.; Lundgren, J.; MacPherson, C.; et al. Associations of the Gut Microbiome and Clinical Factors with Acute GVHD in Allogeneic HSCT Recipients. Blood Advances 2020, 4, 5797–5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesher, L.; Rolston, K.V.I. Febrile Neutropenia in Transplant Recipients. In Principles and Practice of Transplant Infectious Diseases; Safdar, A., Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4939-9032-0. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, A.J.; Battiwalla, M. Relapse after Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Expert Review of Hematology 2010, 3, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, M.; Schreiber, H.; Elder, A.; Heidenreich, O.; Vormoor, J.; Toffalori, C.; Vago, L.; Kröger, N. Epidemiology and Biology of Relapse after Stem Cell Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2018, 53, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, A.; Kaiser, T.; Shields-Cutler, R.; Graiziger, C.; Holtan, S.G.; Rehman, T.U.; Wasko, J.; Weisdorf, D.J.; Dunny, G.; Khoruts, A.; et al. Dysbiosis Patterns during Re-Induction/Salvage versus Induction Chemotherapy for Acute Leukemia. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway-Peña, J.R.; Smith, D.P.; Sahasrabhojane, P.; Ajami, N.J.; Wadsworth, W.D.; Daver, N.G.; Chemaly, R.F.; Marsh, L.; Ghantoji, S.S.; Pemmaraju, N.; et al. The Role of the Gastrointestinal Microbiome in Infectious Complications during Induction Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer 2016, 122, 2186–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, S.; Fukushima, K.; Maeda, T.; Motooka, D.; Nakamura, S.; Fujita, J.; Yokota, T.; Shibayama, H.; Oritani, K.; Kanakura, Y. Pre- and Post-serial Metagenomic Analysis of Gut Microbiota as a Prognostic Factor in Patients Undergoing Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Br J Haematol 2020, 188, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henig, I.; Yehudai-Ofir, D.; Zuckerman, T. The Clinical Role of the Gut Microbiome and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. haematol 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Frank, D.N.; Horch, M.; Chau, S.; Ir, D.; Horch, E.A.; Tretina, K.; Van Besien, K.; Lozupone, C.A.; Nguyen, V.H. Associations between Acute Gastrointestinal GvHD and the Baseline Gut Microbiota of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients and Donors. Bone Marrow Transplant 2017, 52, 1643–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peled, J.U.; Gomes, A.L.C.; Devlin, S.M.; Littmann, E.R.; Taur, Y.; Sung, A.D.; Weber, D.; Hashimoto, D.; Slingerland, A.E.; Slingerland, J.B.; et al. Microbiota as Predictor of Mortality in Allogeneic Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, A. Gut Microbiota in Acute Leukemia: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1045497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holler, E.; Butzhammer, P.; Schmid, K.; Hundsrucker, C.; Koestler, J.; Peter, K.; Zhu, W.; Sporrer, D.; Hehlgans, T.; Kreutz, M.; et al. Metagenomic Analysis of the Stool Microbiome in Patients Receiving Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: Loss of Diversity Is Associated with Use of Systemic Antibiotics and More Pronounced in Gastrointestinal Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2014, 20, 640–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, N.; Greco, R.; Pasciuta, R.; Barbanti, M.C.; Pini, G.; Morrow, O.B.; Morelli, M.; Vago, L.; Clementi, N.; Giglio, F.; et al. Enteric Microbiome Markers as Early Predictors of Clinical Outcome in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: Results of a Prospective Study in Adult Patients. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2017, 4, ofx215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masetti, R.; Leardini, D.; Muratore, E.; Fabbrini, M.; D’Amico, F.; Zama, D.; Baccelli, F.; Gottardi, F.; Belotti, T.; Ussowicz, M.; et al. Gut Microbiota Diversity before Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation as a Predictor of Mortality in Children. Blood 2023, 142, 1387–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, J.A.; Tan, C.Y.; Ren, Y.; Hill, L.; Bush, A.; Lew, M.; Andermann, T.; Peled, J.U.; Gomes, A.; Van Den Brink, M.R.M.; et al. Enterococcus Intestinal Domination Is Associated With Increased Mortality in the Acute Leukemia Chemotherapy Population. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2024, 78, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taur, Y.; Jenq, R.R.; Perales, M.-A.; Littmann, E.R.; Morjaria, S.; Ling, L.; No, D.; Gobourne, A.; Viale, A.; Dahi, P.B.; et al. The Effects of Intestinal Tract Bacterial Diversity on Mortality Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Blood 2014, 124, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Xiong, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Hou, C.; Dou, L.; Zhu, B.; Liu, D. The Impact of Intestinal Microbiota in Antithymocyte Globulin–Based Myeloablative Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Cancer 2022, 128, 1402–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romick-Rosendale, L.E.; Haslam, D.B.; Lane, A.; Denson, L.; Lake, K.; Wilkey, A.; Watanabe, M.; Bauer, S.; Litts, B.; Luebbering, N.; et al. Antibiotic Exposure and Reduced Short Chain Fatty Acid Production after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2018, 24, 2418–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payen, M.; Nicolis, I.; Robin, M.; Michonneau, D.; Delannoye, J.; Mayeur, C.; Kapel, N.; Berçot, B.; Butel, M.-J.; Le Goff, J.; et al. Functional and Phylogenetic Alterations in Gut Microbiome Are Linked to Graft-versus-Host Disease Severity. Blood Advances 2020, 4, 1824–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardzikova, S.; Andrijkova, K.; Svec, P.; Beke, G.; Klucar, L.; Minarik, G.; Bielik, V.; Kolenova, A.; Soltys, K. Gut Diversity and the Resistome as Biomarkers of Febrile Neutropenia Outcome in Paediatric Oncology Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenq, R.R.; Taur, Y.; Devlin, S.M.; Ponce, D.M.; Goldberg, J.D.; Ahr, K.F.; Littmann, E.R.; Ling, L.; Gobourne, A.C.; Miller, L.C.; et al. Intestinal Blautia Is Associated with Reduced Death from Graft-versus-Host Disease. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation 2015, 21, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haak, B.W.; Littmann, E.R.; Chaubard, J.-L.; Pickard, A.J.; Fontana, E.; Adhi, F.; Gyaltshen, Y.; Ling, L.; Morjaria, S.M.; Peled, J.U.; et al. Impact of Gut Colonization with Butyrate Producing Microbiota on Respiratory Viral Infection Following Allo-HCT. Blood 2018, blood-2018-01-828996. [CrossRef]

- Meedt, E.; Hiergeist, A.; Gessner, A.; Dettmer, K.; Liebisch, G.; Ghimire, S.; Poeck, H.; Edinger, M.; Wolff, D.; Herr, W.; et al. Prolonged Suppression of Butyrate-Producing Bacteria Is Associated With Acute Gastrointestinal Graft-vs-Host Disease and Transplantation-Related Mortality After Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra, S.; Szabo, A.; Clurman, A.; McShane, K.; Waters, N.; Eastwood, D.; Samanas, L.; Fei, T.; Armijo, G.; Abedin, S.; et al. Mitigation of Gastrointestinal Graft-versus-Host Disease with Tocilizumab Prophylaxis Is Accompanied by Preservation of Microbial Diversity and Attenuation of Enterococcal Domination. haematol 2022, 108, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein-Thoeringer, C.K.; Nichols, K.B.; Lazrak, A.; Docampo, M.D.; Slingerland, A.E.; Slingerland, J.B.; Clurman, A.G.; Armijo, G.; Gomes, A.L.C.; Shono, Y.; et al. Lactose Drives Enterococcus Expansion to Promote Graft-versus-Host Disease. Science 2019, 366, 1143–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, K.; Hayashi, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Sato, N.; Shimohigoshi, M.; Miyaoka, D.; Yokota, C.; Watanabe, M.; Hisaki, Y.; Kamei, Y.; et al. An Enterococcal Phage-Derived Enzyme Suppresses Graft-versus-Host Disease. Nature 2024, 632, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taur, Y.; Xavier, J.B.; Lipuma, L.; Ubeda, C.; Goldberg, J.; Gobourne, A.; Lee, Y.J.; Dubin, K.A.; Socci, N.D.; Viale, A.; et al. Intestinal Domination and the Risk of Bacteremia in Patients Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2012, 55, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Sheikh, T.M.M.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Yao, F.; Wang, M.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Shafiq, M.; Xie, Q.; et al. Exploring the Dynamics of Gut Microbiota, Antibiotic Resistance, and Chemotherapy Impact in Acute Leukemia Patients: A Comprehensive Metagenomic Analysis. Virulence 2024, 15, 2428843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. The Effect of Antibiotics on the Composition of the Intestinal Microbiota - a Systematic Review. Journal of Infection 2019, 79, 471–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taur, Y.; Coyte, K.; Schluter, J.; Robilotti, E.; Figueroa, C.; Gjonbalaj, M.; Littmann, E.R.; Ling, L.; Miller, L.; Gyaltshen, Y.; et al. Reconstitution of the Gut Microbiota of Antibiotic-Treated Patients by Autologous Fecal Microbiota Transplant. Sci Transl Med 2018, 10, eaap9489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masetti, R.; D’Amico, F.; Zama, D.; Leardini, D.; Muratore, E.; Ussowicz, M.; Fraczkiewicz, J.; Cesaro, S.; Caddeo, G.; Pezzella, V.; et al. Febrile Neutropenia Duration Is Associated with the Severity of Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis in Pediatric Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Recipients. Cancers 2022, 14, 1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doki, N.; Suyama, M.; Sasajima, S.; Ota, J.; Igarashi, A.; Mimura, I.; Morita, H.; Fujioka, Y.; Sugiyama, D.; Nishikawa, H.; et al. Clinical Impact of Pre-Transplant Gut Microbial Diversity on Outcomes of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Ann Hematol 2017, 96, 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galloway-Peña, J.R.; Peterson, C.B.; Malik, F.; Sahasrabhojane, P.V.; Shah, D.P.; Brumlow, C.E.; Carlin, L.G.; Chemaly, R.F.; Im, J.S.; Rondon, G.; et al. Fecal Microbiome, Metabolites, and Stem Cell Transplant Outcomes: A Single-Center Pilot Study. Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biagi, E.; Zama, D.; Rampelli, S.; Turroni, S.; Brigidi, P.; Consolandi, C.; Severgnini, M.; Picotti, E.; Gasperini, P.; Merli, P.; et al. Early Gut Microbiota Signature of aGvHD in Children given Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Hematological Disorders. BMC Med Genomics 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artacho, A.; González-Torres, C.; Gómez-Cebrián, N.; Moles-Poveda, P.; Pons, J.; Jiménez, N.; Casanova, M.J.; Montoro, J.; Balaguer, A.; Villalba, M.; et al. Multimodal Analysis Identifies Microbiome Changes Linked to Stem Cell Transplantation-Associated Diseases. Microbiome 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, E.; Zama, D.; Nastasi, C.; Consolandi, C.; Fiori, J.; Rampelli, S.; Turroni, S.; Centanni, M.; Severgnini, M.; Peano, C.; et al. Gut Microbiota Trajectory in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015, 50, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar Ud Din, M.; Lin, Y.; Lyu, C.; Yi, C.; Fang, A.; Mao, F. Advancing Therapeutic Strategies for Graft-versus-Host Disease by Targeting Gut Microbiome Dynamics in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Mol Med 2025, 31, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, A.; Ebadi, M.; Rehman, T.U.; Elhusseini, H.; Kazadi, D.; Halaweish, H.; Khan, M.H.; Hoeschen, A.; Cao, Q.; Luo, X.; et al. Randomized Double-Blind Phase II Trial of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Versus Placebo in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation and AML. JCO 2023, 41, 5306–5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, J.L.; Pergam, S.A.; Srinivasan, S.; Fiedler, T.L.; Liu, C.; Garcia, K.; Mielcarek, M.; Ko, D.; Aker, S.; Marquis, S.; et al. Stool Microbiota at Neutrophil Recovery Is Predictive for Severe Acute Graft vs Host Disease After Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2017, 65, 1984–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; He, C.; An, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Fu, W.; Wang, M.; Shan, Z.; Xie, J.; Yang, Y.; et al. The Role of Short Chain Fatty Acids in Inflammation and Body Health. IJMS 2024, 25, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, R.-G.; Zhou, D.-D.; Wu, S.-X.; Huang, S.-Y.; Saimaiti, A.; Yang, Z.-J.; Shang, A.; Zhao, C.-N.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Health Benefits and Side Effects of Short-Chain Fatty Acids. Foods 2022, 11, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, E.R.; Lam, Y.K.; Uhlig, H.H. Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Linking Diet, the Microbiome and Immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 2024, 24, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Lao, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, S. Research Advances on Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Gastrointestinal Acute Graft- versus -Host Disease. Therapeutic Advances in Hematology 2024, 15, 20406207241237602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolling, T.; Zhai, B.; Gjonbalaj, M.; Tosini, N.; Yasuma-Mitobe, K.; Fontana, E.; Amoretti, L.A.; Wright, R.J.; Ponce, D.M.; Perales, M.A.; et al. Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation Outcomes Are Linked to Intestinal Mycobiota Dynamics and an Expansion of Candida Parapsilosis Complex Species. Nat Microbiol 2021, 6, 1505–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sun, H.; Cao, W.; Han, L.; Song, Y.; Wan, D.; Jiang, Z. Applications of Gut Microbiota in Patients with Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation. Exp Hematol Oncol 2020, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metafuni, E.; Di Marino, L.; Giammarco, S.; Bellesi, S.; Limongiello, M.A.; Sorà, F.; Frioni, F.; Maggi, R.; Chiusolo, P.; Sica, S. The Role of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in the Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant Setting. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshifuji, K.; Inamoto, K.; Kiridoshi, Y.; Takeshita, K.; Sasajima, S.; Shiraishi, Y.; Yamashita, Y.; Nisaka, Y.; Ogura, Y.; Takeuchi, R.; et al. Prebiotics Protect against Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease and Preserve the Gut Microbiota in Stem Cell Transplantation. Blood Advances 2020, 4, 4607–4617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdandoust, E.; Hajifathali, A.; Roshandel, E.; Zarif, M.N.; Pourfathollah, A.A.; Parkhideh, S.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Amini-Kafiabad, S. Gut Microbiota Intervention by Pre and Probiotics Can Induce Regulatory T Cells and Reduce the Risk of Severe Acute GVHD Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Transplant Immunology 2023, 78, 101836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckerson, J.; Szydlo, R.M.; Hickson, M.; Mactier, C.E.; Innes, A.J.; Gabriel, I.H.; Palanicawandar, R.; Kanfer, E.J.; Macdonald, D.H.; Milojkovic, D.; et al. Impact of Route and Adequacy of Nutritional Intake on Outcomes of Allogeneic Haematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Haematologic Malignancies. Clinical Nutrition 2019, 38, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lier, Y.F.; Davids, M.; Haverkate, N.J.E.; De Groot, P.F.; Donker, M.L.; Meijer, E.; Heubel-Moenen, F.C.J.I.; Nur, E.; Zeerleder, S.S.; Nieuwdorp, M.; et al. Donor Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Ameliorates Intestinal Graft-versus-Host Disease in Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karimi, M.; Shirsalimi, N.; Hashempour, Z.; Salehi Omran, H.; Sedighi, E.; Beigi, F.; Mortezazadeh, M. Safety and Efficacy of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) as a Modern Adjuvant Therapy in Various Diseases and Disorders: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1439176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biernat, M.M.; Urbaniak-Kujda, D.; Dybko, J.; Kapelko-Słowik, K.; Prajs, I.; Wróbel, T. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in the Treatment of Intestinal Steroid-Resistant Graft-versus-Host Disease: Two Case Reports and a Review of the Literature. J Int Med Res 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battipaglia, G.; Malard, F.; Rubio, M.T.; Ruggeri, A.; Mamez, A.C.; Brissot, E.; Giannotti, F.; Dulery, R.; Joly, A.C.; Baylatry, M.T.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation before or after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Transplantation in Patients with Hematologic Malignancies Carrying Multidrug-Resistance Bacteria. Haematologica 2019, 104, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, A.J.; Mullish, B.H.; Fernando, F.; Adams, G.; Marchesi, J.R.; Apperley, J.F.; Brannigan, E.; Davies, F.; Pavlů, J. Faecal Microbiota Transplant: A Novel Biological Approach to Extensively Drug-Resistant Organism-Related Non-Relapse Mortality. Bone Marrow Transplant 2017, 52, 1452–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, R.; Mullish, B.H.; McDonald, J.A.K.; Ghazy, A.; Williams, H.R.T.; Brannigan, E.T.; Mookerjee, S.; Satta, G.; Gilchrist, M.; Duncan, N.; et al. Disease Prevention Not Decolonization: A Model for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Patients Colonized With Multidrug-Resistant Organisms. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021, 72, 1444–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neemann, K.; Eichele, D.D.; Smith, P.W.; Bociek, R.; Akhtari, M.; Freifeld, A. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Fulminant CLostridium Difficile Infection in an Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplant Patient. Transplant Infectious Dis 2012, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, C.G.; Ganc, A.J.; Ganc, R.L.; Petrolli, M.S.; Hamerschlack, N. Fecal Microbiota Transplant after Hematopoietic SCT: Report of a Successful Case. Bone Marrow Transplant 2015, 50, 145–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluestone, H.; Kronman, M.P.; Suskind, D.L. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Recurrent Clostridium Difficile Infections in Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2018, 7, e6–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, A.J.; Mullish, B.H.; Ghani, R.; Szydlo, R.M.; Apperley, J.F.; Olavarria, E.; Palanicawandar, R.; Kanfer, E.J.; Milojkovic, D.; McDonald, J.A.K.; et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplant Mitigates Adverse Outcomes Seen in Patients Colonized With Multidrug-Resistant Organisms Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, P.E. Regulatory Considerations for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Products. Cell Host & Microbe 2020, 27, 173–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyama, S.; Tatsumi, H.; Shiraishi, T.; Yoshida, M.; Tatekoshi, A.; Endo, A.; Ishige, T.; Shiwa, Y.; Ibata, S.; Goto, A.; et al. Possible Clinical Outcomes Using Early Enteral Nutrition in Individuals with Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Nutrition 2021, 83, 111093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Amico, F.; Biagi, E.; Rampelli, S.; Fiori, J.; Zama, D.; Soverini, M.; Barone, M.; Leardini, D.; Muratore, E.; Prete, A.; et al. Enteral Nutrition in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic SCT Promotes the Recovery of Gut Microbiome Homeostasis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyama, S.; Sato, T.; Tatsumi, H.; Hashimoto, A.; Tatekoshi, A.; Kamihara, Y.; Horiguchi, H.; Ibata, S.; Ono, K.; Murase, K.; et al. Efficacy of Enteral Supplementation Enriched with Glutamine, Fiber, and Oligosaccharide on Mucosal Injury Following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Case Rep Oncol 2014, 7, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riwes, M.M.; Golob, J.L.; Magenau, J.; Shan, M.; Dick, G.; Braun, T.; Schmidt, T.M.; Pawarode, A.; Anand, S.; Ghosh, M.; et al. Feasibility of a Dietary Intervention to Modify Gut Microbial Metabolism in Patients with Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Nat Med 2023, 29, 2805–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcari, S.; Ng, S.C.; Zitvogel, L.; Sokol, H.; Weersma, R.K.; Elinav, E.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G.; Tilg, H.; Ianiro, G. The Microbiome for Clinicians. Cell 2025, 188, 2836–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcari, S.; Mullish, B.H.; Asnicar, F.; Ng, S.C.; Zhao, L.; Hansen, R.; O’Toole, P.W.; Raes, J.; Hold, G.; Putignani, L.; et al. International Consensus Statement on Microbiome Testing in Clinical Practice. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2025, 10, 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzayi, C.; Renson, A.; Genomic Standards Consortium; Massive Analysis and Quality Control Society; Furlanello, C.; Sansone, S.-A.; Zohra, F.; Elsafoury, S.; Geistlinger, L.; Kasselman, L.J.; et al. Reporting Guidelines for Human Microbiome Research: The STORMS Checklist. Nat Med 2021, 27, 1885–1892. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).