1. Introduction

In the past decade, the black soldier fly (BSF), Hermetia illucens (L.) (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) has been gaining interest in both the scientific research and industrial applications. As an efficient decomposer of organic waste, BSF larvae are extensively investigated for the bioconversion of waste into protein and fertilizer, making it a keystone species in sustainable agriculture and circular food systems (Tomberlin & van Huis, 2020; Tomberlin et al., 2022). At the same time, BSF is increasingly recognised as a model organism for fundamental studies in evolutionary biology and behavioural ecology (Tomberlin et al., 2025). Yet, this potential remains largely underexplored: Industry priorities have overwhelmingly driven most of the research towards larval life history traits, rendering the reproductive biology of the adult as a “black box”. A recent bio-economic analysis even suggested that improving larval growth and conversion efficiency yields higher economic returns than improving reproductive traits. Yet, reproduction is the ‘heartbeat’ of any species’ life cycle and in the case of a mass-reared insect like BSF, neglecting the reproductive phase constrains both scientific understanding and industrial optimization (Lemke, Dickerson & Tomberlin, 2023; Meneguz et al., 2023; Tomberlin et al., 2025).

Insects vary drastically across lineages in reproductive strategies (Wilson, 1999) and emerging evidence suggests BSF is unique in many ways. For instance, many classical insect models such as Drosophila melanogaster, are income breeders. In a strict sense, this means these organisms require feeding as adults to reproduce, and more loosely speaking, foraging can still extend lifespan and increase reproductive fitness for those using a hybrid-strategy (Zhang et al., 2025a). By contrast, capital breeders such as BSF do not need to feed as adults to successfully reproduce (Tomberlin, Sheppard & Joyce, 2002a). Instead, adult reproduction is almost entirely dependent on nutritional reserves accumulated during the larval stage. BSF also exhibit protandry (Tomberlin et al., 2002a) where males emerge several days before females, the timing of whose emergence is modulated by larval nutrition (Zhang et al., 2025a). In nature (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001) and captive colonies (Lemke, Rollison & Tomberlin, 2024), adults can form lek-like swarms in which both sexes can mate multiple times in a polygynandrous mating system (Manas et al., 2025b), that impacts both pre- and postcopulatory sexual selection. Moreover, increasing reports from industrial optimization suggests that reproduction in BSF can also be environmentally modulated (Chia et al., 2018; Addeo et al., 2022). Factors such as like UV-light spectrum and intensity (Zhang et al., 2010), the presence of specific substrate volatiles for oviposition (Zheng et al., 2013), and even the physical design of mating cages (Grosso et al., 2025) can significantly influence mating success and fecundity in captivity, further driving shifts in the mating system.

Understanding the features of BSF reproduction has broad implications for both evolutionary biology and applied entomology. For decades, classical model organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster Meigen 1830 (Diptera: Drosophilidae) have dominated the fundamental research landscape (Kohler, 1994; Markow, 2015). While it is undeniable that D. melanogaster has yielded pivotal insights in science, it also represents only a narrow slice of insect diversity and its utility has often stemmed from an assumption of laboratory tractability (Ankeny & Leonelli, 2011). In fact, comparative studies now suggest that laboratory strains of D. melanogaster often differ significantly from wild populations, underscoring the need for broader taxonomic representation of model systems (Markow, 2015). Indeed, laboratory rearing conditions represent an alternative ecological niche by which species evolve and diverge from their wild counterparts (Kohler, 1994). Moreover, recent NIH budget cuts have substantially reduced funding for the D. melanogaster bioinformatics repository, FlyBase (flybase.org, May 2025), highlighting the risks of over-reliance on single model species and heralding the need to diversify and develop alternative models. The emergence of BSF as a research model is therefore timely, representing a different lineage (viz., a basal group of the lower Brachycera) with a different reproductive strategy that can also bridge evolutionary biology and applied entomology in ways that few other insect models can. Not only does the BSF lek-like system make it relatable to organisms across the animal tree of life (including lekking crustaceans, insects, fish, amphibians, birds, and mammals) (Lemke, 2025), but BSF is also positioned centrally within the Dipteran lineage between many economically- and culturally-important Nematocera (including mosquitoes, gnats, midges, black flies, drain flies, sand flies, and crane flies) and the Muscomorpha (including hover flies, Tsetse flies, blow flies, bot flies, Tachnid flies, true fruit flies, stalk-eyed flies, and Drosophila) (Yeates & Wiegmann, 2005; Lambkin et al., 2013).

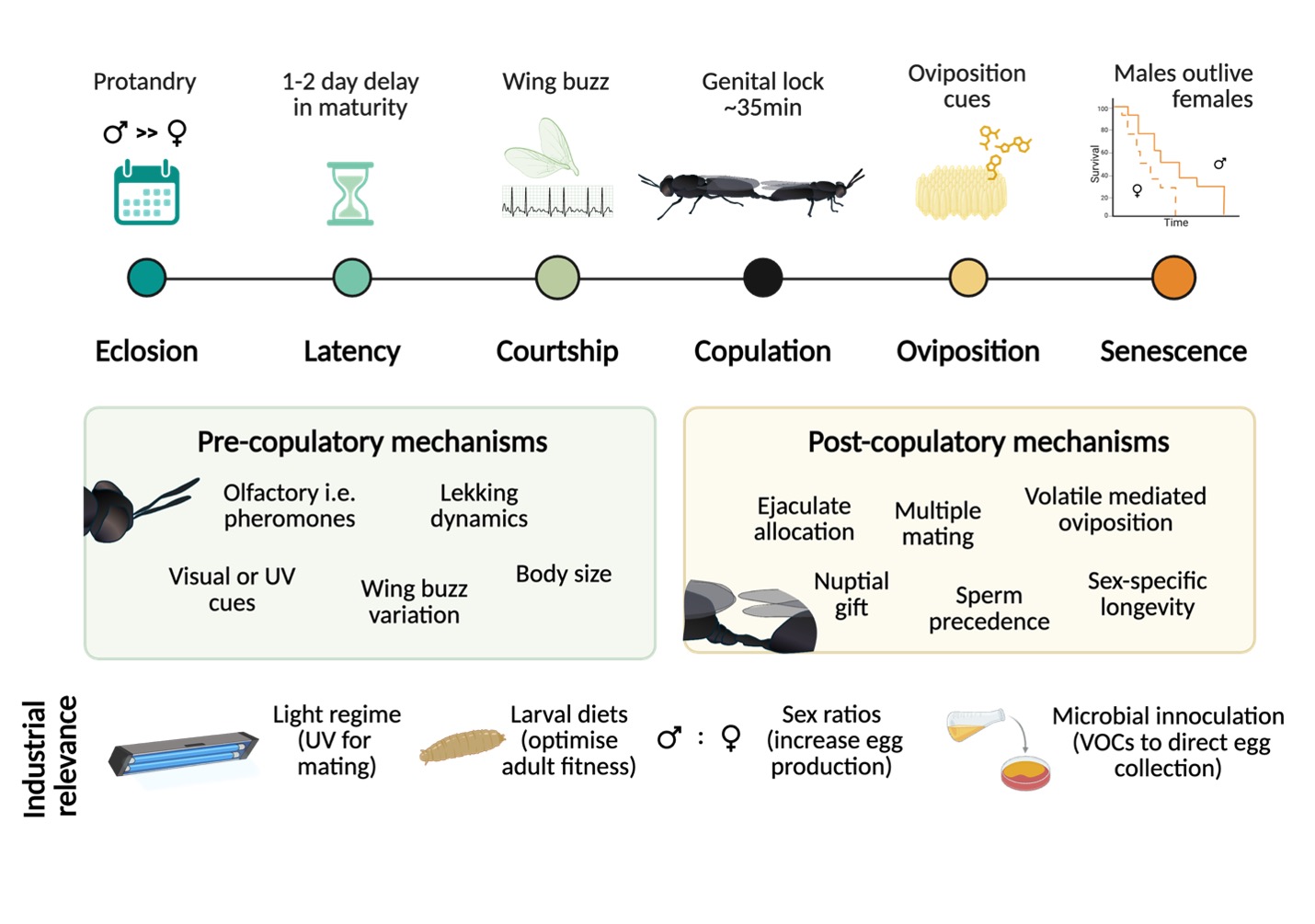

Here, we synthesise emerging empirical evidence on BSF reproduction into a comprehensive conceptual framework, identifying key research gaps (

Figure 1). We examine processes that govern reproduction from adult emergence and sexual maturation, through mating latency, courtship and copulation, to sperm transfer and storage, as well as oviposition and senescence. Throughout this review, we discuss these elements in the context of sexual selection theory and aim to reposition BSF as a viable model for reproductive evolution and behavioural ecology. We also discuss how external factors, from lighting regimes to substrate cues can influence reproduction and emphasise opportunities to translate fundamental knowledge into improved rearing practices. By comparing BSF with classical models and drawing insights from other taxa, we highlight key areas for future research.

2. Mechanisms and Dynamics of Reproduction

Reproduction in BSF is a complex process shaped by nutritional history, social context, and environmental cues. From latency to senescence, both males and females exhibit dynamic physiological and behavioural adaptations that challenge earlier depictions of BSF as a monogamous or behaviourally uniform species (Nakamura et al., 2016; Park et al., 2017; Giunti et al., 2018; Freitas Spindola, 2019; Macavei et al., 2020; Malawey et al., 2020; Surendra et al., 2020; Awal et al., 2022). To clarify this issue and others, we summarise how the pre-copulatory, copulatory and post-copulatory phases contribute to overall reproductive success.

2.1. Pre-Copulatory Phase

2.1.1. Latency and Sexual Maturation

Protandry is a defining feature of BSF, with males emerging several days before females (Tomberlin et al., 2002a; Meyermans et al., 2025). In butterflies and other insects, protandry is a common tendency, occurring in ~36% of species (Teder et al., 2021), and is believed to be a strategy used by males to better monopolise females. Protandry may be an adaptive mechanism to facilitate the alignment of male persistence and female receptivity (Zhang et al., 2025b), since by emerging prior to females, this minimises the female’s time spent unmated (Fagerström & Wiklund, 1982). The total degree of the separation between males and female emergences, i.e., sexual bimaturism (SBM) in BSF is modulated by larval nutrition and interacts with adult body size and longevity (Generalovic et al., 2025), being also a covariate of size dimorphism (Teder et al., 2021), meaning as females grow in size relative to males, the degree of SBM also increases. In BSF, protandry also seems predicated on the condition that adults do not need to feed or forage prior to mating (Tomberlin et al., 2002a). Instead, they rely almost exclusively on the resource accumulation during the larval stage (Lemke et al., 2023; Harjoko et al., 2023). However, BSF may not be strict capital breeders, and there is some evidence to suggest that supplemental nutrition can benefit adult fitness as well (Thinn & Kainoh, 2022; Klüber et al., 2023; Barrett et al., 2025), though this is not always consistent (Lemke et al., 2023; Coudron et al., 2025a). Certainly, reproduction can proceed without feeding but provisioning adults with water can aid by preventing dehydration (Sheppard et al., 2002) and to also promote welfare (Barrett et al., 2025).

Immediately post-eclosion, male BSF also possess some sperm (ca. 3,000 - 11,000 spermatazoa) (Munsch-Masset et al., 2023), similar to D. melanogaster. Males also typically delay initiating mating by one to two days post-eclosion, likely synchronizing with the timeline of female oocyte maturation (Tomberlin et al., 2002a; Meyermans et al., 2025). This timing is also suspected to coincide with wild population dynamics, since BSF males would use this time to establish their position within a lekking site while females emerge and mature (Lemke et al., 2025). Indeed, in true fruit fly species (Ceratitis capitata; Tephritidae) and other Diptera where males display in groups, reproductive success is modulated by position within the lek, e.g., a central position or on specific trees (Shelly, 2018). Male BSF continue to produce sperm throughout life but testes size shrinks with age, suggesting that there could be an upper limit on lifetime total sperm production of up to ~50 000 per male (Munsch-Masset et al., 2023; Manas et al., 2024). Recent experimental work also suggests that sperm quantity is influenced by social exposure and housing conditions, which is likely an adaptive response to sperm competition risk (Manas, Labrousse & Bressac, 2025a). Sperm length may also play a role in competitive fertilization success and BSF have relatively long sperm (Malawey et al., 2019, 2020), being 6-times longer than the average length of other animals with internal fertilization (Munsch-Masset et al., 2023),, with a notable exception of Drosophila (Lüpold et al., 2016), e.g., the giant sperm species Drosophila bifurca (Pitnick, Markow & Spicer, 1995; Luck et al., 2007). Although inadequate larval nutrition in BSF can generate smaller males with shorter sperm (Zhang et al., 2025b), it is still unclear if there are potential trade-offs in quantity versus quality and whether these would translate to direct fitness effects.

In contrast to males, the ovaries of female BSF develop post-emergence, with synchronous egg maturation from a single ovariole (Munsch-Masset et al., 2023). This distinguishes BSF from many other proovigenic insects where their eggs are all mature at the onset of their adult life, as well as many insects whose fecundity is linked to both the number and variation of ovarioles (Moore, 2014).Synovogenic egg development (i.e., starting adult life with immature eggs) in other insects is thought to be related to stochastic developmental conditions, which aligns with BSF development, given that larvae can subsist on nutrient-poor substrates. Hence, rather than being a fixed number, total female egg number in BSF is instead tightly correlated with adult body size (Spearman’s ρ = 0.73) which in turn depends on larval nutrition (Gobbi, Martínez-Sánchez & Rojo, 2013; Shrestha et al., 2025). As such, BSF exhibit large variations in fertility (i.e., hatching rate) that can range from 30 to 90% and can also be influenced by early development conditions (Laursen et al., 2024; Zhang & Puniamoorthy, 2025). However, it is harder to disentangle what proportion of this variability in fertility is a female versus male mediated effect as the problem could arise with either sperm or eggs.

2.1.2. Navigation and Lekking

The mechanisms by which adult insects locate mating sites can differ. Damselflies seek out riverbanks (Hetaerina spp.; Odonata) (Córdoba-Aguilar et al., 2009), neotropical orchid bees target treefalls or decaying wood to collect volatile compounds (Euglossini: Hymenoptera: Apidiae (Kimsey, 1980) whilst coprophagous insects such as dung beetles gather at dung pats that act as competitive mating arenas (Hanski & Cambefort, 2016). To date, the exact mechanisms by which BSF locate mating sites in the wild remain largely unknown. Inferences from industrial observations suggest that flies may be guided by gradients in light, because newly eclosed adults from darkened pupation area will be attracted towards illuminated zones (Dortmans et al., 2017; Coudron et al., 2025b). This is exploited in mass-rearing systems for automated counting, since flies can be funneled through a pinhole (James et al., 2024). This behaviour may mirror patterns of natural emergence in the wild since the larvae are negatively phototropic and often wander off prior to pupation (Giannetti et al., 2022).

While natural lekking sites have been described as occurring hundreds to thousands of meters from emergence zones (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001; Lemke et al., 2023), it is unclear whether stochasticity (e.g., updrafts of wind) or specific cues drive BSF navigation to leks in the wild. Other lekking or aggregating insects often follow chemical trails, detect conspecifics swarming frequencies, or seek out certain landmarks (Alcock, 1984). For instance, Neotropical owl butterflies, Caligo spp., (Srygley & Penz, 1999) gather towards forest edges, and a close relative of BSF, Hermetia comstockii show preference for Agave plants (Alcock, 1990)). What sparse reports of wild BSF are clearly biased towards the ovipositing females, since these are attracted to the volatiles emanating from anthropogenic wastes. Historically BSF were found in “dense mats” on the sides of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOS) where solid manure from chickens and/or pigs accumulated line (Tomberlin et al. 2002 citing Lorimar 2001 [white paper]), or in the nearby kudzu-infested tree (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001). But, since the introduction of feed-through pesticides targeting house flies after ca. 1980 (Sheppard et al., 2002), BSF populations may have been unintentionally affected, since BSF are also highly sensitive to such pesticides (Tomberlin, Sheppard & Joyce, 2002b). In addition, BSF are apparently reluctant to enter enclosed spaces (e.g., homes or CAFO buildings) (Furman, Young & Catts, 1959; Sheppard et al., 2002), making the only obvious link between the mating site to the oviposition site, which can be thousands of meters away (Lemke et al., 2023) is the distance females must fly on limited energy reserves (Tomberlin et al., 2002a; Harjoko et al., 2023).

Other lekking species utilise and respond to semiochemicals, the most famous of which might be male fruit flies which can be attracted with Trimudlure or essential oils, such that they can be easily trapped and leks artificially created (Shelly, Whittier & Kaneshiro, 1993) (Refer to

Section 4.4 for further discussion). But unlike these other insects, the mechanism for how BSF assemble in leks is puzzling considering that BSF might not emit any attraction pheromones (Lemke

et al., 2023). Within the artificial environment, mating flies often display spatial segregation away from the oviposition sites and towards less-humid microenvironments (Unpublished data). This suggests that in an industrial setting, dedicated mating arenas and oviposition areas within the cage could enhance reproductive success (Salari & De Goede, 2024) (Refer to Box 1 and section 4.3 for further discussion).

2.1.3. Courtship and Mounting

In BSF, male activity and courtship is triggered by female flight or entry into a swarm . In captivity, females have been observed to momentarily leave their perch (on artificial plants or walls) to enter male swarms occurring near artificial light sources (Lemke et al., 2024) before returning to perch or descending in copula. This observed behaviour appears to mirror natural history descriptions in which females visit the lek, where, due to protandry, males are already present (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001; Lemke et al., 2023). Indeed, similar temporal patterns in perching and flight activity have been described in the lekking Synpetrum danae (Sulzer) (Odonata: Anisoptera: Libellulidae), in which reproductive activity peaked at solar noon with male flight activity, compared to females whose activity increased in the early afternoon (Michiels & Dhondt, 1989).

BSF males initiate courtship by performing aerial displays of wing-fanning, and it may be wing-interference patterns (WIPs) that are recognised by conspecifics (Rebora et al., 2024). In addition to these visual displays, male BSF produce vibratory songs (Giunti et al., 2018; Laudani et al., 2024), similar to many other groups of insects (e.g., crickets, grasshoppers, fruit flies) (Baker, Clemens & Murthy, 2019). Wing-buzzing might be a valuable predictor of mating success (Briceño et al., 2002; Aldersley & Cator, 2019), as is the case for in mosquitoes and fruit flies, but in BSF, it could have also evolved as an anti-predator defense, as seen in the blow fly, Lucilia sericata (Meigen) (Diptera: Calliphoridae) (Sawyer et al., 2021). In Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae), males and females match the harmonics of their buzzing by rapidly modulating the tone of their wingbeats (Aldersley & Cator, 2019). Besides tone, mating songs need to have the proper rhythm (Eberhard & Gelhaus, 2009), as it could provide sex-specific cues about potential mates. In BSF, an earlier study suggested longer duration of wing-buzzing was positively correlated with body size and mating success (Giunti et al., 2018), but more recent work shows an opposite trend with shorter wing-buzzing preferred (Laudani et al., 2024), suggesting the trait is may be plastic.

While air borne, BSF males mount females and attempt genital engagement. Successful pairs in copula generally rotate their position 180 degrees resulting in a tail-to-tail posture that is maintained during copulation while perched on a surface, although some remain mounted from behind (Chiabotto et al., 2024). The ability to rotate between the two positions is enabled by flexible genitalia (Rollinson et al., 2025) and may also allow the pair to take flight and relocate in response to disturbance (pers. obs.).

BOX 1: Debates on Mate Discrimination and Lekking

In BSF, detection and discrimination of mates may be facilitated by sexual dimorphism in wing interference patterns created by differences in structural colouration (Butterworth et al., 2021; Rebora et al., 2024). These likely facilitate the differential development of photoreceptive sensitivity of the ommatidia in BSF compound eyes (Oonincx et al., 2016). In fact, evidence suggests that visual neural pathways are more developed in males than females (Barrett et al., 2022). These visual cues may compensate for BSF’s limited head mobility and reliance on proprioception while in flight (Paulk & Gilbert, 2006). While some suggest that these may be cues that enable mate recognition in BSF (Rebora et al., 2024), others contend that BSF males cannot discriminate between sexes or kin (Giunti et al., 2018; Laudani et al., 2024) and that these may be artifacts from experimental studies.

Another argument against mate discrimination is the lack of sexual dimorphism in their cuticular hydrocarbon (CHCs) profiles (Lemke et al., 2023), though the same is the case for the New World screw worm fly, Cochliomyia hominivorax (Pomonis, 1989). Instead, many sexually reproducing insects communicate via sociochemical signals once they make physical contact (Ingleby, 2015). For instance, the CHCs of Drosophila can encode information based on species, sex, reproductive status, age, social rank, which together mediate attractiveness (Holze, Schrader & Buellesbach, 2021). In BSF, however, it is unclear as to how adults differentiate amongst each other and what are the actual cues that signal attractiveness, especially in the context of lekking or mating amidst a swarm. Indeed, females entering swarming leks (associated with flies) have historically been described as exhibiting little if any mate choice (simply allowing males to choose them) (Alcock, 1987); though likely stems from a lack of evidence (and the difficult of obtaining such evidence in field studies) rather than evidence for the contrary.

Lekking is the aggregation of many individuals at a mating site, often in structured hierarchies. It is a complex phenomenon, characterised by several behaviours including a lack of male parental care, sex-based dispersion, territoriality, and the absence of resource monopolization. However, lekking itself is no longer viewed within a strict definition (Alcock, 1987). Each of these criteria can be viewed as a continuum in multidimensional parameter space, like the Hutchinsonian niche (Hutchinson, 1957) to give a more holistic view of lekking systems. Moreover, the lek mating system itself also can be modeled along a gradient of increasing resource dependence and mate-monopolization (Emlen & Oring, 1977; Parker, 1978; Thornhill & Alcock, 1983), and can shift dynamically if these underlying factors change. For instance, when males are unable to control access to females, this leads to scramble competition polygyny (Herberstein, Painting & Holwell, 2017). Conversely, when females become rare, the mating system can also shift to (and between) resource-defense polygyny or female-defense polygyny if males start to monopolise female resources or the females themselves (Buzatto & Machado, 2008). For instance, the males of the Wellington tree weta, Hemideina crassidens (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae) guard tree galleries needed by females as diurnal refugia (Kelly, 2006), whereas territorial male wasps (Hymenoptera) guard the hives from which females emerge or the flowers they visit (Alcock et al., 1978). Similarly, the water used by aquatic species, the fruit used by parasites, or carcasses used by scavengers can be guarded by males, but such is not the case for lekking in which mating occurs independent of such resources. Mating systems that fall shy of these two extremes, but still have some similarity to a true lek, are called ‘lek-like’. Lekking has been described in one other congener Hermetia comstockii (Diptera: Stratimyidae) which defend perches on agave plants (Alcock, 1990), but not in more distantly related Merosargus cingulatus (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), which mate near their oviposition site of decomposing vegetation (Barbosa, 2011), or to Inopus rubiceps (Macquart) (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) which engages in scramble competition (Alcock, 1990).

In BSF, there exists debate as to whether lekking as a whole is preserved in captivity (Lemke et al., 2023; Lemke, 2025) and whether large aggregations are even a prerequisite for BSF mating (Laudani et al., 2024), since mating has now been described in lone pairs of BSF (Jensen et al., 2025). Some studies report a clear behavioural segregation of the sexes (Lemke et al., 2024) but other aspects of lekking are often not reported because most detailed behavioural studies in BSF are typically done at small scale (i.e., as few as 2 individuals in a 1m3). However, when BSF are reared at the industrial scale, (i.e., cages housing thousands of individuals per cubic meter), this makes manual observations of individual behaviour impossible. Moreover, a highly competitive breeding environment may facilitate a new evolutionary (sub)optimum whereby satellite leks of lone individuals are favored. Some field and lab observations document stable male aggregations (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001; Lemke et al., 2024), whilst other reports mention no aggregation except ephemeral mating balls involving multiple males (Permana, Fitri & Julita, 2020) which might be mistaken for leks. In other words, to date, there exists a lack of evidence (but not necessarily disproving) that BSF colonies exhibit a structured and spatiotemporally mediated hierarchy and whether this is directly linked with variation in reproductive fitness.

2.2. Copulatory Phase

2.2.1. Copulatory Mechanics, Duration and Sperm Transfer

Copulation in BSF is marked by genital engagement lasting approximately 35 minutes [insert +/- SD) (Manas et al., 2025a), the onset of which is defined by a physical 'lock' between the male and female genitalia. Rival males cease interruption attempts and the duration of the genital lock appears mostly unaffected by adult size but varies with age (Manas et al., 2025b, 2025a), suggesting that BSF might not engage in mate guarding. However, overall mating duration is prolonged in inbred cohorts and individuals that experienced poor larval nutrition (Laudani et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025a) but it is notable that sperm transfer does not occur continuously throughout this time frame. Dissection of females at different times during mating suggests that sperm is delivered during the latter half of copulation, approximately after the first 25 minutes, following the transmission of seminal fluids (Manas et al., 2025a). Matings might last between 20-42 minutes (Giunti et al., 2018), with an average of 33.32 ± 10.19 min (Manas et al., 2024), but potentially can be as long as 50.2 ± 26.6 min, since mean copulation duration increasing with each subsequent mating (Manas et al., 2025b). At the end, both sexes disengage and typically perform grooming behaviours for 101.15 ± 17.47 s (males) or 296.92 ± 39.22 s (females) (Giunti et al., 2018; Laudani et al., 2024). While at present there is little evidence to suggest mate guarding taking place in BSF, in other species, such as Parastrachia japonensis Scott (Hemiptera: Cydinae), mating duration is an alternative mating tactic (AMT) dependent on the density of females (Tsukamoto, Kuki & Tojo, 1994). When females are dense and the species exhibits scramble competition, 93% of matings were ‘short’, but when females became rare, males monopolised females by increasing mating duration 91-fold from 14.9 ± 10.3 seconds to 22.6 ± 14.7 min (Tsukamoto et al., 1994).

2.2.2. Sperm Storage

After mating, BSF females store sperm in multiple spermathecae, enabling fertilization of several egg clutches over time. Females possess complex sperm storage organs: Three spherical spermathecae, attached to three sclerotised rods that end in hinges, which are connected to three separate fishnet canals (that also contain sperm) (Munsch-Masset et al., 2023; Bruno et al., 2025). The total number of sperm stored in females can vary from the hundreds to the thousands (Manas et al., 2024) and it may take about 48h for approximately 50% of transferred sperm to reach the sperm storage reservoirs. Most critically, recent work has shown that a single mating is enough to fill a female’s sperm reservoirs in excess, which challenges previous hypothesis that females were sperm limited (Permana et al., 2020), and instead supports the view that a single ejaculate can provide sufficient sperm for multiple clutches. In addition, recent work also suggests that stored sperm quantity but not viability decreases over time, suggesting that a possibility for sperm dumping or sperm digestion by females. In addition, the social environment or presence of rival males appears to also influence sperm storage because females that mate in the presence of conspecifics also retained more sperm than those isolated post-copulation (Manas et al., 2025a).

Box 2: Reproductive Skews and Re-Mating in BSF

Reproduction in BSF can be dependent on both biotic—e.g., sex ratio, density(Hoc et al., 2019)—and abiotic factors (e.g. light, temperature, stressors(Dearlove et al., 2025)) and experimental studies suggest that mating frequencies can vary dramatically across populations and colonies (Jones & Tomberlin, 2021; Dickerson et al., 2024; Lemke et al., 2024; Meyermans et al., 2025; Lemke et al., 2025). In fact, in populations of 500 M:500 F, only 43-120 mating events were observed over a week, suggesting steep reproductive skews (Meyermans et al., 2025). Indeed a recent experiment has shown that in test populations of 15 M: 15 F, 48% of males did not mate, and of those that did, 50% of BSF mated multiply (Manas et al., 2025b). In addition to the dominance of a few individuals, if some are mating multiple times, but not all flies mate, this suggests a low effective population size, owing potentially to population substructures. For the population, the majority of matings occur on the D1 or D2 of being in mating cages, but continue to occur at a low rate after this, reaching a plateau between D4 and D6 (Tomberlin et al., 2002a; Dickerson et al., 2024; Lemke et al., 2024). Although such reproductive skews are consistent with a lek-based system, in which a minority of males achieve most or all copulations, thus far, no studies have quantified relative reproductive fitness as a function of mating rates (sensu Bateman’s gradients (Bateman, 1946)). Behavioural assays have observed male BSF to mate up to four times and females up to twice (Chiabotto et al., 2024; Laudani et al., 2024) but higher female polyandry, up to 5-times, has been supported by parentage assignments (Hoffmann, 2021). These recent studies highlight the potential for strong postcopulatory sexual selection, influencing ejaculate-female interactions, and overall reproductive fitness.

2.3. Post-Copulatory Phase

2.3.1. Oviposition

Following copulation, oviposition for BSF typically occurs between four to six days post emergence and females lay eggs in small, dry crevices near the actual oviposition substrate that is often wet and humid. Indeed, this adaption to thrive in moist substrates is one that must have allowed Diptera to transition away from aquatic development into terrestrial niches. For BSF, female fecundity, i.e. the number of eggs laid, can vary as a function of adult nutrition (Thinn & Kainoh, 2022; Klüber et al., 2023; Barrett et al., 2025), body size (Gobbi et al., 2013), age (Dickerson et al., 2024), and even genetic relatedness (Laudani et al., 2024). Several recent studies suggest female BSF can oviposit multiple times (Hoffmann, 2021; Jones & Tomberlin, 2021; Chiabotto et al., 2024; Laudani et al., 2024), though assertions continue to be made that BSF oviposit only once (Sibonje, 2024). Originally these additional clutches were thought to be completely infertile (Nakamura et al., 2016) but it has now shown that female BSF can potentially lay two to three fertile clutches after only a single mating (Manas et al., 2024).

The timing of oviposition itself can be both genetically and environmentally influenced. Inbred strains exhibit longer pre-oviposition intervals (Laudani et al., 2024), while adequate adult feeding shortens the time between copulation and oviposition (Barrett et al., 2025). Likewise, delaying mating (e.g., as an artifact of experimental set-up) is also suspected to cause females to haphazardly lay eggs when females lay single (or additional) clutches (Dickerson et al., 2024; Muraro et al., 2024; Lemke et al., 2024) far away from the larval substrate. Off-target egg laying can quickly snowball since females are attracted to VOCs released by eggs (Klüber et al., 2024). Fecundity and fertility (i.e. the proportion of larvae that hatch) can trade-off at industrial scale (Hoc et al., 2019) and recent study suggests that larval nutrition can induce phenotypic plasticity in both female fecundity as well as fertility (Zhang & Puniamoorthy, 2025).

2.3.2. Aging & Senescence

Aging in adult BSF is often marked by visible changes in the physical condition of flies including wing damage, limb loss, and desiccation. These likely occur from repeated attempts to mate or oviposit despite declining energy reserves, since in other mass-reared Diptera, harassment is associated with injury to females (Meza et al., 2025). Observations from both laboratory and industrial settings report older BSF frequently crashing to cage floor during flight or even spinning erratically after having broken one of their wings. In BSF, aging can be estimated based on the decreasing opacity of the abdominal ‘windows’ (Harjoko et al., 2023) though which one can observe changes in the stored nutrient reserves. These translucent windows are thought to have evolved to mimic the petiole of Polistes paper wasps (James, 1935; Alcock, 1990). Observing changes in it can serve as a non-invasive indicator of physiological decline and has been successfully adopted for population management in industrial settings (Salari & De Goede, 2024).

Experimental studies suggest that longevity in both sexes can be extended by provisioning adults with water (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2002) and food (Lemke et al., 2023; Barrett et al., 2025). Interestingly, the seminal components transferred by males to females may also contribute to female longevity, potentially acting as nuptial gifts (Harjoko et al., 2023) for females to digest (Manas et al., 2024) by supplying amino acids and/or lipids that may support egg development and/or metabolic function. Older males exhibit reduced mating frequency (Dickerson et al., 2024) and fertility, due to declining sperm viability (Malawey et al., 2020). This means that housing mixed ages of BSF adults can reduce the efficiency of reproduction at the industrial scale (Lemke et al., 2025). For instance, older, less competitive males may interfere with females mating with younger mates, as observed in Tephritid flies (Papanastasiou et al., 2011), which has necessitated habitat design that features distinct areas for each sex. Similarly, female clutch size and egg viability also declines with age and egg collections from mixed age cohorts will undoubtedly exhibit a greater variability in survival and overall fitness.

Box 3: Dynamics of oviposition site selection

In natural settings, mating and oviposition often occur at spatially distant and distinct sites (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001; Lemke et al., 2023; Lemke, 2024), which one hypothesis states could have evolved to dilute predation pressure (Rathore, Isvaran & Guttal, 2023). BSF larvae are polyphagous and are able to thrive on a wide range of substrates but most accounts of wild-trapped females are typically associated with anthropogenic waste (Sripontan et al., 2017; Nyakeri et al., 2017; Ewusie et al., 2019; Ferdousi et al., 2022; Purkayastha & Sarkar, 2023; Sable & Chavan, 2024; Yaseen et al., 2025) Controlled experiments have revealed that BSF prefer to oviposit in vegetable/fruit waste (Kotzé & Tomberlin, 2020; Laksanawimol, Singsa & Thancharoen, 2023; Zim et al., 2023), though may also utilise the medium near aged carrion (Kotzé & Tomberlin, 2020), or manure (Zim et al., 2023). However, experiments have also shown that female BSF do not necessarily select the oviposition site which coincides with highest fitness (Boafo et al., 2023; Tekaat, 2024), meaning there are other ecological factors at play, and possibly maternal-offspring conflicts. The selection of oviposition sites (ergo larval foraging sites) is undoubtably driven by volatised cues emitted by microbial communities and conspecifics (Zheng et al., 2013; Klüber et al., 2024; Thomas et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2025b). Key attractants included tetradecanoic acid, sulcatone and acetophone that could increase oviposition. Such olfactory actions have been confirmed by amputating BSF antennae for choice test experiments (Klüber et al., 2024). Importantly, there could be a physiological switch that is triggered post-mating for females (Lemke et al., 2025), as has been found in Tephritidae (Jang et al., 1999), because unmated/virgin female BSF showed no clear behavioural preferences for oviposition cues, whilst gravid females exhibited a clear response to the tetradecanoic acid (Klüber et al., 2024), or various plant-based attractants (Laksanawimol et al., 2023). However, electroantennographic recordings confirm the olfactory abilities of BSF in response to various volatiles by both sexes with substantial overlap in their responses (Piersanti et al., 2024), despite female antennae having longer flagellum than males, which would suggest increased function (Pezzi et al., 2021). Moreover, it is unclear whether oviposition behaviour is modulated by seminal fluid proteins; molecules similar to sex peptide in Drosophila that are transferred in the male ejaculate, triggering a cascade of behavioural and physiological changes in females (Chapman et al., 2003). Interestingly, they evolved as a way to increase male fitness often at a cost to their fitness (Wigby & Chapman, 2005), which has engendered a great deal of study by evolutionary biologists.

3. Implications for Evolutionary Biology

The black soldier fly (BSF) offers a distinctive combination of traits that make it a promising model for reproductive evolution. As a capital breeder (Stephens et al., 2009), adult reproduction is fueled almost entirely by larval-derived reserves, decoupling gametogenesis and courtship investment from adult foraging. This life-history mode shifts sexual selection dynamics relative to other income-breeding insects (Stephens et al., 2009) as well as all the anautogenous blood-feeding Diptera (which require a blood meal to produce eggs), and some potential trade-offs include those between larval resource allocation, somatic growth, longevity, and reproductive output (Miller, 2005). Multiple mating by females influences sperm competition among males, a ubiquitous force in insect reproduction (Parker, 1970). Comparative studies also show how sperm traits evolve under such competition: Drosophila bifurca produces the longest sperm in the animal kingdom, while lepidopterans package sperm into nutrient-rich spermatophores (Pitnick et al., 1995; Vahed, 1998). Mating system studies in BSF now document polygynandry, steep reproductive skews, extended sperm storage, and possible cryptic female choice, including ejaculate digestion and selective sperm retention (Muraro et al., 2024; Manas et al., 2024, 2025a). These patterns provide a framework to quantify pre- vs post-copulatory sexual selection gradients under varying sex ratios, densities, and age structures. Because BSF lek-like aggregations can be labile in captivity (Lemke, 2025), they also allow experimental manipulation of mating system architecture.

Phenotypic plasticity in response to larval diet affects key reproductive traits, including body size, fecundity and sperm length, that also interacts with heritable variation to shape evolutionary potential (Gobbi et al., 2013; Shrestha et al., 2025; Zhang & Puniamoorthy, 2025). Selection for adult body weight or oviposition output can yield rapid responses but also risks inbreeding depression (Meyermans et al., 2025). Laboratory studies show BSF can adapt within generations to suboptimal diets (Jiggins, 2024), supporting their use in experimental evolution. Recent genomic surveys indicate substantial diversity among global BSF populations, including behavioural and reproductive incompatibilities between some strains (Silvaraju et al., 2025). This raises the possibility of a cryptic species complex (Ståhls et al., 2020; Generalovic et al., 2023; Athanassiou et al., 2024) and provides an avenue to examine potential mechanisms governing reproductive isolation under domestication. The interaction between industrial selection pressures and ancestral reproductive behaviours such as mate-site separation from oviposition sites (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001), also enables tests of how evolutionary “holdovers” persist or decay in closed systems (Lemke et al., 2024).

3.1. Cryptic Female Choice, Sperm Competition and Sexual Conflict

The complex interactions between males and females, both pre- and post-copulation reveal a potential for sex-specific strategies that can influence fitness. Insects such as Drosophila, crickets, and butterflies can bias sperm use through differential storage or ejection of sperm from less-preferred males (Eberhard, 1991). The highly specialised sperm storage organs of BSF females are capable of retaining more sperm than required to fertilise a single clutch (Manas et al., 2024). Retention duration, sperm viability, and selective sperm use suggest potential for cryptic female choice as described in other Stratiomyidae (Barbosa, 2009, 2011, 2012, 2015). Females may regulate sperm uptake or storage, discard rival sperm, or bias fertilization toward preferred males, but such mechanisms remain largely untested in BSF.

Males exhibit strategic ejaculate allocation, and can adjust their sperm investment in response to perceived competition (Manas et al., 2025a). Sperm length in BSF is unusually long for internally fertilizing animals (Malawey et al., 2019, 2020) and is sensitive to larval diet quality (Zhang & Puniamoorthy, 2025), suggesting potential trade-offs between sperm quality and quantity that could shape competitive fertilization outcomes. However, the degree to which sperm precedence follows “last male wins” patterns, as seen in other Diptera, is unknown, nor how this pattern may subsequently break down with high amounts of remating (Zeh & Zeh, 1997; Laturney, van Eijk & Billeter, 2018) or as flies senesce (Mack, Priest & Promislow, 2003). Indeed this phenomena is quite complex, since last-male sperm precedence may arise, not just males remove or displace their rivals’ sperm, but also as alluded to if the female herself digests or ejects the first males’ sperm from her genital tract prior to a subsequent mating (Luck et al., 2007; Schnakenberg, Siegal & Bloch Qazi, 2012).

Although not formally tested, the mating system of BSF may also be subject to sexual antagonism or sexual conflict, and vice-versa (Bedhomme et al., 2009; Candolin, 2019; Plesnar-Bielak & Łukasiewicz, 2021). Specifically, sexual conflict refers to interactions between males and females that can impose fitness costs on one sex while benefiting the other, potentially driving coevolutionary dynamics between male manipulation and female resistance (Chapman & Partridge, 1996). Often, the number of matings that optimises fitness for males is higher than it is for the females (Wigby & Chapman, 2005). As mentioned before, BSF males have been seen to mate up to 4 times, whereas females can mate twice or more (Chiabotto et al., 2024). Male harassment to secure these extra matings may interfere with female oviposition or even induce injury (Pitnick & García–González, 2002), such that increased exposure to males may be negatively associated with female lifetime fitness (Fowler & Partridge, 1989; Morrow & Gage, 2001). In addition, males may transfer seminal fluid proteins (e.g. sex peptides) that influence female re-mating latency or stimulate reproductive development (Kubli, 1992). These act to increase the male’s fitness at the cost of female’s (Wigby & Chapman, 2005). In fact, mating in BSF has been shown to reduce male longevity whilst increasing females’ suggesting a potential trade-off between mating frequency and fitness for each sex (Harjoko et al., 2023).

Together, these processes place BSF among the minority of capital-breeding insects (e.g., Lepidoptera of the families Notodontidate, Arctiidae, Lymantriidae, Saturniidae and Lasiocampidae (Tammaru & Haukioja, 1996), and others) in which both sperm competition and cryptic female choice can be studied under controlled conditions. The combination of tractable rearing, measurable reproductive traits, and manipulable social context makes BSF a suitable system for testing predictions of post-copulatory sexual selection theory, from sperm allocation models to sexual conflict evolution.

4. Implications for Industrial Applications

Industrial BSF production depends on predictable, high-output reproduction, yet adult reproductive biology remains a major bottleneck. While larval traits dominate economic models (Zaalberg et al., 2024), adult reproduction is the rate-limiting step in closed-cycle rearing (Boller, 1972). Optimizing adult phase management requires translating evolutionary and behavioural insights into practical protocols.

4.1. Genetics and Population Structure

High genetic diversity among global BSF stocks (Ståhls et al., 2020; Sandrock et al., 2021; Kaya et al., 2021; Generalovic et al., 2023) underlines the need for controlled breeding strategies to prevent inbreeding depression and maintain adaptive capacity. Selective breeding regimes for increased body size, fecundity, or other traits must thus consider potential correlated (or antagonistic) trade-offs in mating behaviour or sperm traits Recent work suggests that within populations, age (Dickerson et al., 2024; Lemke et al., 2025) and genetic heterogeneity (Laudani et al., 2024; Meyermans et al., 2025) influence mating rates, sperm competition intensity, and egg viability, As for. Overrepresentation of old or non-competitive males appears to depress productivity (Dickerson et al., 2024; Lemke et al., 2025), thus managing the instantaneous operational sex ratios (iOSR) by rotating breeding cohorts is predicted to reduce skewed mating success and maintain effective population size.

4.2. Nutritional Management

Studies have shown that for BSF, adult access to water and nutrient supplements (viz., honey, pollen, or sugar water) can extend lifespan, shorten pre-oviposition intervals, and improve egg output under some conditions (Thinn & Kainoh, 2022; Klüber et al., 2023; Barrett et al., 2025). So, although BSF are typically considered capital breeders, providing adults access to nutrition will shift their position within the capital-income breeding continuum (Davis et al., 2016), and many sympatric sister species have been shown to occupy slightly different ecological niches in this way, such as in Curculio weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) (Pélisson et al., 2013). Interestingly, in Hymenoptera and Lepidoptera income breeding is negatively associated with ovigeny index (the initial egg load divided by the potential lifetime fecundity) but allows for individuals to engage in mixed strategies to compensate for deficient nutrition acquired as larvae. The opposite is true too, with capital breeding and strict proovigeny (the emergence of a female’s entire potential lifetime complement of eggs) is associated with stable and predictable larval conditions (Pélisson et al., 2012). For BSF, since larval diet can influence adult reproductive strategies, supplementing the nutrition of adult breeding stocks may be necessary to sustain high fecundity, especially to compensate for the fact that waste remediation efforts by industry will necessarily require larvae to be fed on low quality feed stocks. However, such changes could extend generation times and overall gains should be balanced against longer production cycles and increased labor (Lemke et al., 2023).

4.3. Sex Ratios and Cage Design

Because some lek-like behaviours appear to persist in captive BSF (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001; Lemke et al., 2023, 2024) it is theorised that physical separation of the mating and oviposition zones within cages, proper provisioning of microclimates, and a precise control of light gradients can enhance reproductive success (Lemke et al., 2025). Such has been done for mass-reared fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae), which require specialised habitat design with separate environments for male and female premating development (Liedo et al., 2007; Meza et al., 2025). A recent report indicates that BSF microhabitat preference is related to their age, and so different cohorts of flies may be physically isolated through cage compartmentalization to (Salari & De Goede, 2024) which ultimately should help to maintain a proper iOSR and age-structure of the breeding zone, increasing fertile egg production.

In addition, cage designs should consider enhanced structural complexity by including artificial or live plants. For BSF, the increased perching area provided by the plants has been shown to increase mating rates, although the magnitude of the effects varies with the density of the plants provided (Lemke et al., 2024; Grosso et al., 2025). In the dragonfly species S. danae, females preferred higher perches and overgrown regions of their outdoor cage and their preferred height increased along with higher temperatures (Michiels & Dhondt, 1989), further suggesting the importance of habitat design and abiotic interactions for optimizing BSF production. Although not necessary for BSF, live plants can help modulate ambient humidity via transpiration of water vapor, as well as to ameliorate air quality by assimilating ammonia (NH3) into their leaf tissues (Zayed et al., 2023). By mimicking natural conditions, the effects of providing plants can potentially improve insect welfare by reducing stress, as is the case in captive cockroaches (Blattodea) (Free & Wolfensohn, 2023).

4.4. Chemical Ecology and Oviposition Control

The interplay between VOC-mediated oviposition cues and deterrents opens opportunities for chemical manipulation of oviposition behaviour in industrial mass-rearing. In addition to attractants, some compounds (e.g., decanoic acid) have been shown to delay oviposition behaviour in BSF, while others increase off-target laying. Because synthetic blends combining multiple VOCs elicit stronger responses than individual components alone (Thomas et al., 2024), this means that a precise blend can be engineered as part of a push–pull strategy (Menger et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2022) to more precisely direct egg-laying both away from cage materials and towards the trap. Once realised, this will improve collection efficiency, reduce off-target oviposition, and facilitate automated egg harvesting.

In addition to directing oviposition, aromatherapy using both plant essential oils (e.g., α-copaene derived from sweet orange, grapefruit, guava, papaya, and mango; methyl eugenol; raspberry keytone; α-Pinene; Zingerone) (Zeni et al., 2021) and synthetic compounds (e.g., Trimedlure) (Shelly et al., 1993) has been shown to artificially stimulate lek formation and mating in many species of Tephridae. Of course, because Tephritids have co-opted secondary plant metabolites as a rendezvous-signal for their mating aggregations (often in fruit trees), a similar effect of a secondary plant metabolite on BSF is mere speculation until such a plant-insect interaction can be uncovered.

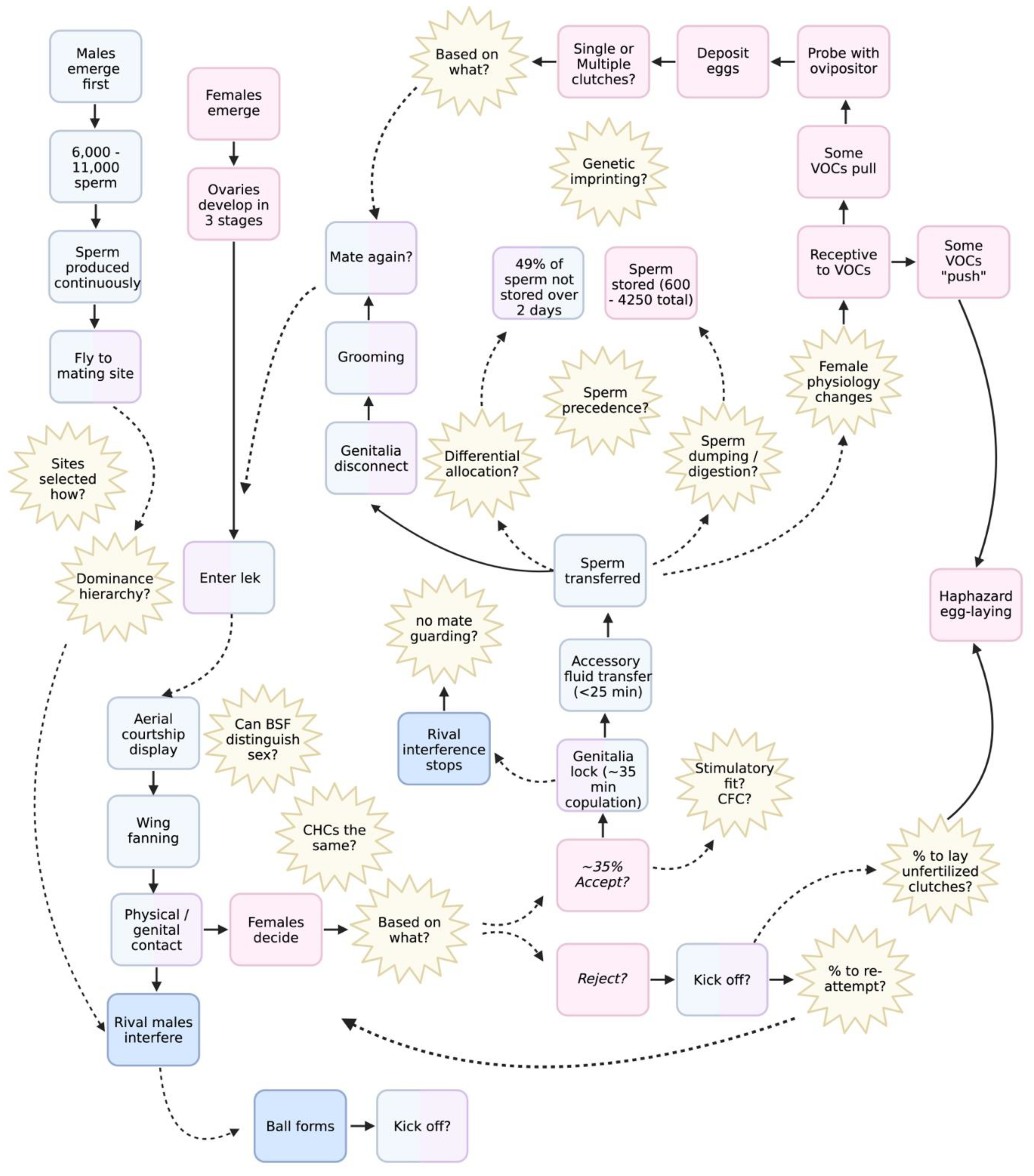

5. Conceptual Model

The previous sections highlight many important research gaps still yet to be unveiled. Here we have condensed them into a single process flow diagram depicting the BSF mating system (

Figure 1), described as follows:

As adults, male BSF emerge first, followed by females due to protandry. From this point males fly to a lekking site, but it is unknown what drives site selection or the mechanisms that determine the dominance hierarchy therein. Females then fly to visit the lek. Aerial courtship commences and males will fan and buzz their wings. Whether or not BSF can recognise conspecifics or distinguish between sexes based on WIPs is unknown, nor what features a successful BSF courtship song has, or whether gentilic stridulation is necessary for females to accept mates. The characteristics that a female might select or reject a mate based on are also unknown, as are whether alternative mating tactics emerge from a result of these preferences. During mating rivals could interfere but can also be rebuffed by the females who ‘kicks’ them off. Successful mating seems to occur once BSF lock genitalia for ~30 minutes (but potentially up to 1 hr), though this total duration might be plastic, and it is not known whether BSF utilise mate guarding as an AMT. For ~25 minutes, seminal fluid is transferred to the female, of which might include something like sex peptide found in Drosophila. How mating or non-gametic material transferred during mating acts to influence female physiological changes is also unknown but speculated to occur. During the last 5 minutes of mating sperm is transferred to females. After mating flies groom themselves. During the next few days, sperm compete with one another within the genital tract of the female, and may either be stored in her spermathecae, digested, or discarded. What enables BSF sperm to outcompete their rivals such as sperm precedence is not fully understood, nor the potential mechanisms of post-reproductive (cryptic) choice in females such as genetic imprinting. After mating females become receptive to volatile organic compounds which can then direct them towards or away from an oviposition site. Once there, the female extends her ovipositor which has gustatory and hygroreceptors and probes the area. If abiotic conditions are suboptimal at the oviposition site, this may drive the female to haphazardly lay her eggs outside of the target area. Of course, both males and females have the option to remate, but it is not fully understood what leads an individual to mate multiply (or not at all), nor what drives females remate prior to or after oviposition. Moreover, many of these interactions might have male and/or female components driving them, leaving many opportunities for future research.

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Studying BSF reproduction aids in addressing both fundamental evolutionary questions and practical constraints for industry. As a capital-breeding, lek-like species with plastic reproductive traits, BSF offer a rare opportunity to experimentally test pre- and post-copulatory processes. In addition, as a non-pest species that is easily culturable, BSF provides an avenue to study reproductive processes that are happening in other insect species with similar life history and reproductive traits.

Future research priorities include: (i) Identifying the visual, chemical, and acoustic cues used for mate recognition and lek formation in wild and captive context; (ii) Quantifying sperm precedence patterns and female control over fertilization; (iii) Investigating the potential trade-offs between production efficiency (larval size and nutrition), supplemental adult nutrition, and breed stock resilience (adult reproduction); (v) Documenting the variation in BSF phenome with respect to differing genetic provenances and nutritional legacies; and (v) Developing management strategies to balance genetic diversity with targeted selection.

Achieving these will require controlled experiments, comparative fieldwork, and molecular tools to track paternity and reproductive investment. In addition, standardizing methodologies such as population densities, light regimes, and cage designs, will improve reproducibility and comparisons across studies. We propose that future research leverage this model to bridge gaps between behavioural ecology, reproductive physiology, and insect biotechnology.

References

- ADDEO, N.F. , LI, C., RUSCH, T.W., DICKERSON, A.J., TARONE, A.M., BOVERA, F. & TOMBERLIN, J.K. (2022) Impact of age, size, and sex on adult black soldier fly Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) thermal preference. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 8, 129–139. Wageningen Academic Publishers.

- Alcock, J. Convergent Evolution in Perching and Patrolling Site Preferences of Some Hilltopping Insects of the Sonoran Desert. Southwest. Nat. 1984, 29, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, J. Leks and hilltopping in insects. J. Nat. Hist. 1987, 21, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, J. A Large Male Competitive Advantage in a Lekking Fly, Hermetia Comstocki Williston (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Psyche: A J. Èntomol. 1990, 97, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, J.; Barrows, E.M.; Gordh, G.; Hubbard, L.J.; Kirkendall, L.; Pyle, D.W.; Ponder, T.L.; Zalom, F.G. The ecology and evolution of male reproductive behaviour in the bees and wasps. Zoöl. J. Linn. Soc. 1978, 64, 293–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldersley, A.; Cator, L.J. Female resistance and harmonic convergence influence male mating success in Aedes aegypti. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ANKENY, R.A. & LEONELLI, S. (2011) What’s so special about model organisms? Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part A 42, 313–323.

- ATHANASSIOU, C.G. , COUDRON, C.L., DERUYTTER, D., RUMBOS, C.I., GASCO, L., GAI, F., SANDROCK, C., DE SMET, J., TETTAMANTI, G., FRANCIS, A., PETRUSAN, J.-I. & SMETANA, S. (2024) A decade of advances in black soldier fly research: from genetics to sustainability. Brill.

- AWAL, MD.R. , RAHMAN, MD.M., CHOUDHURY, MD.A.R., HASAN, MD.M., RAHMAN, MD.T. & MONDAL, MD.F. (2022) Influences of artificial light on mating of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens)—a review. International Journal of Tropical Insect Science, 1–5.

- Baker, C.A.; Clemens, J.; Murthy, M. Acoustic Pattern Recognition and Courtship Songs: Insights from Insects. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 42, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, F. Cryptic female choice by female control of oviposition timing in a soldier fly. Behav. Ecol. 2009, 20, 957–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F. Copulation duration in the soldier fly: the roles of cryptic male choice and sperm competition risk. Behav. Ecol. 2011, 22, 1332–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F. Males responding to sperm competition cues have higher fertilization success in a soldier fly. Behav. Ecol. 2012, 23, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BARBOSA, F. (2015) An integrative view of postcopulatory sexual selection in a soldier fly: Interplay between cryptic male choice and sperm competition. In Cryptic Female Choice in Arthropods: Patterns, Mechanisms and Prospects (eds A.V. PERETTI & A. AISENBERG), pp. 385–401. Springer International Publishing, Cham.

- Barrett, M.; Godfrey, R.K.; Sterner, E.J.; Waddell, E.A. Impacts of development and adult sex on brain cell numbers in the Black Soldier Fly, Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Arthropod Struct. Dev. 2022, 70, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BARRETT, M., PATEL, N., MCCARRY, B., SHELLENBERGER, G., SCHWARTZ, E., FIOCCA, K. & WADDELL, E. (2025) Dietary preferences and impacts of feeding on behavior, longevity, and reproduction in adult black soldier flies (Diptera: Stratiomyidae; Hermetia illucens). OSF. https://osf.io/p74xq_v1 [accessed 29 May 2025].

- Bateman, A.J. Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila. Heredity 1948, 2, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedhomme, S.; Bernasconi, G.; Koene, J.M.; Lankinen, Å.; Arathi, H.S.; Michiels, N.K.; Anthes, N. How does breeding system variation modulate sexual antagonism? Biol. Lett. 2009, 5, 717–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boafo, H.; Gbemavo, D.; Timpong-Jones, E.; Eziah, V.; Billah, M.; Chia, S.; Aidoo, O.; Clottey, V.; Kenis, M. Substrates most preferred for black soldier fly Hermetia illucens (L.) oviposition are not the most suitable for their larval development. J. Insects Food Feed. 2022, 9, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boller, E. Behavioral aspects of mass-rearing of insects. BioControl 1972, 17, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño, R.D.; Eberhard, W.G.; Vilardi, J.C.; Liedo, P.; Shelly, T.E. VARIATION IN THE INTERMITTENT BUZZING SONGS OF MALE MEDFLIES (DIPTERA: TEPHRITIDAE) ASSOCIATED WITH GEOGRAPHY, MASS-REARING, AND COURTSHIP SUCCESS. Fla. Èntomol. 2002, 85, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, D.; Manas, F.; Bonelli, M.; Gold, M.; Marzari, M.; Roma, D.; Valoroso, M.; Montali, A.; Guillaume, J.; Rebora, M.; et al. BugBook: life cycle, reproduction, and morphofunctional characterisation of the gut, fat body, and haemocytes in the black soldier fly. J. Insects Food Feed. 28. [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, N.J.; White, T.E.; Byrne, P.G.; Wallman, J.F. Love at first flight: wing interference patterns are species-specific and sexually dimorphic in blowflies (Diptera: Calliphoridae). J. Evol. Biol. 2021, 34, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzatto, B.A.; Machado, G. Resource defense polygyny shifts to female defense polygyny over the course of the reproductive season of a Neotropical harvestman. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2008, 63, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CANDOLIN, U. (2019) Sexual selection and sexual conflict. In Encyclopedia of Ecology pp. 310–318. Elsevier.

- Chapman, T.; Bangham, J.; Vinti, G.; Seifried, B.; Lung, O.; Wolfner, M.F.; Smith, H.K.; Partridge, L. The sex peptide of Drosophila melanogaster: Female post-mating responses analyzed by using RNA interference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003, 100, 9923–9928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, T.; Partridge, L. Sexual conflict as fuel for evolution. Nature 1996, 381, 189–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHIABOTTO, C., GROSSO, F., DORETTO, A. MENEGUZ, M. (2024) Observation of mating behavior using marked flies of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) under sunlight condition. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 10, 2017–2029. Brill.

- Chiabotto, C.; Grosso, F.; Doretto, A.; Meneguz, M. Observation of mating behavior using marked flies of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) under sunlight condition. J. Insects Food Feed. 2024, 10, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CÓRDOBA-AGUILAR, A. , RAIHANI, G., SERRANO-MENESES, M.A. & CONTRERAS-GARDUÑO, J. (2009) The Lek Mating System of Hetaerina Damselflies (Insecta: Calopterygidae). Behaviour 146, 189–207. Brill.

- COUDRON, C.L. , ADAMAKI-SOTIRAKI, C., YAKTI, W., PASCUAL, J.J., WIKLICKY, V., SANDROCK, C., VAN PEER, M., ATHANASSIOU, C., PEGUERO, D.A., RUMBOS, C., NASER EL DEEN, S., VELDKAMP, T., DERUYTTER, D. & CAMBRA-LÓPEZ, M. (2025a) Bugbook: Basic information and good practices on how to maintain stock populations for Tenebrio molitor and Hermetia illucens for research. Brill.

- COUDRON, C.L. , ADAMAKI-SOTIRAKI, C., YAKTI, W., PASCUAL, J.J., WIKLICKY, V., SANDROCK, C., VAN PEER, M., ATHANASSIOU, C., PEGUERO, D.A., RUMBOS, C., NASER EL DEEN, S., VELDKAMP, T., DERUYTTER, D. & CAMBRA-LÓPEZ, M. (2025b) Bugbook: Basic information and good practices on how to maintain stock populations for Tenebrio molitor and Hermetia illucens for research. Brill.

- Cui, Z.; Si, P.; Liu, L.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Q. Push-pull strategy for integrated control of Bactrocera minax (Diptera, Tephritidae) based on olfaction and vision. J. Appl. Èntomol. 2022, 146, 1243–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.B.; Javoiš, J.; Kaasik, A.; Õunap, E.; Tammaru, T. An ordination of life histories using morphological proxies: capital vs. income breeding in insects. Ecology 2016, 97, 2112–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DEARLOVE, E. , VAN GESTEL, C.A.M., LOUREIRO, S., SVENDSEN, C., LLOYD, M., MUGO-KAMIRI, L., PETERSEN, J.M., BESSETTE, E., EDWARDS, S., LIM, F.S., HERREN, P., HERNÁNDEZ PELEGRÍN, L., PIENAAR, R.D., HUDITZ, H., MOSTAFAIE, A., ET AL. (2025) BugBook: Determining multiple stressor interactions in mass-reared insects based on principles of ecotoxicology. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed, 1–18.

- Dickerson, A.J.; Lemke, N.B.; Li, C.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Crippen, T. Impact of age on the reproductive output of Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). J. Econ. Èntomol. 2024, 117, 1225–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DORTMANS, B. , DIENER, S., VERSTAPPEN, B. & ZURBRÜGG, C. (2017) Black soldier fly biowaste processing.

- Eberhard, W.G. COPULATORY COURTSHIP AND CRYPTIC FEMALE CHOICE IN INSECTS. Biol. Rev. 1991, 66, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBERHARD, W.G. & GELHAUS, J.K. (2009) Genitalic stridulation during copulation in a species of crane fly, Tipula (Bellardina) sp. (Diptera: Tipulidae). Rev. Biol. Trop. 57, 6.

- Emlen, S.T.; Oring, L.W. Ecology, Sexual Selection, and the Evolution of Mating Systems. Science 1977, 197, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewusie, E.; Kwapong, P.; Ofosu-Budu, G.; Sandrock, C.; Akumah, A.; Nartey, E.; Tetegaga, C.; Agyakwah, S. The black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): Trapping and culturing of wild colonies in Ghana. Sci. Afr. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerström, T.; Wiklund, C. Why do males emerge before females? protandry as a mating strategy in male and female butterflies. Oecologia 1982, 52, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdousi, L.; Sultana, N.; Bithi, U.H.; Lisa, S.A.; Hasan, R.; Siddique, A.B. Nutrient Profile of Wild Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Prepupae Reared on Municipal Dustbin’s Organic Waste Substrate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B: Biol. Sci. 2022, 92, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, K.; Partridge, L. A cost of mating in female fruitflies. Nature 1989, 338, 760–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, D.; Wolfensohn, S. Assessing the Welfare of Captive Group-Housed Cockroaches, Gromphadorhina oblongonota. Animals 2023, 13, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FREITAS SPINDOLA, A. (2019) Morphological and Physiological Reproductive Aspects of Black Soldier Fly: Applications for Optimal Industrial Scale Production. Thesis,.

- Furman, D.P.; Young, R.D.; Catts, P.E. Hermetia illucens (Linnaeus) as a Factor in the Natural Control of Musca domestica Linnaeus. J. Econ. Èntomol. 1959, 52, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GENERALOVIC, T.N. , SANDROCK, C., ROBERTS, B.J., MEIER, J.I., HAUSER, M., WARREN, I.A., PIPAN, M., DURBIN, R. & JIGGINS, C.D. (2023) Cryptic diversity and signatures of domestication in the Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens). bioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.10.21.563413v2 [accessed ]. 11 August.

- GENERALOVIC, T.N. , ZHOU, W., ZHAO, L.C., LEONARD, S., WARREN, I.A., PIPAN, M. & JIGGINS, C.D. (2025) Repeatable phenotypic but not genetic response to selection on body size in the black soldier fly. bioRxiv. https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.02.25.640052v1 [accessed ]. 29 May.

- Giannetti, D.; Schifani, E.; Reggiani, R.; Mazzoni, E.; Reguzzi, M.C.; Castracani, C.; Spotti, F.A.; Giardina, B.; Mori, A.; Grasso, D.A. Do It by Yourself: Larval Locomotion in the Black Soldier Fly Hermetia illucens, with a Novel “Self-Harvesting” Method to Separate Prepupae. Insects 2022, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunti, G.; Campolo, O.; Laudani, F.; Palmeri, V. Male courtship behaviour and potential for female mate choice in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Èntomol. Gen. 2018, 38, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, P.; Martínez-Sánchez, A.; Rojo, S. The effects of larval diet on adult life-history traits of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Eur. J. Èntomol. 2013, 110, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, F.; Lattarulo, A.; Meneguz, M.; Padula, C. Biomimicry in love-cage design: boosting black soldier fly mass production. J. Insects Food Feed. 11. [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.J. Dung Beetle Ecology. J. Anim. Ecol. 1993, 62, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoko, D.N.; Hua, Q.Q.H.; Toh, E.M.C.; Goh, C.Y.J.; Puniamoorthy, N. A window into fly sex: mating increases female but reduces male longevity in black soldier flies. Anim. Behav. 2023, 200, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, W.L.; Menz, M.H.; Wotton, K.R. Lords of the flies: dipteran migrants are diverse, abundant and ecologically important. Biol. Rev. 2025, 100, 1635–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- HERBERSTEIN, M.E. , PAINTING, C.J. & HOLWELL, G.I. (2017) Scramble competition polygyny in terrestrial arthropods. In Advances in the study of behavior (eds M. NAGUIB, J. PODOS, L.W. SIMMONS, L. BARRETT, S.D. HEALY & M. ZUK), pp. 237–295. Elsevier, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- Hoc, B.; Noël, G.; Carpentier, J.; Francis, F.; Megido, R.C.; Falabella, P. Optimization of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) artificial reproduction. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0216160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HOFFMANN, L. (2021) Genetic diversity and mating systems in a mass-reared black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) population. Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, Western Cape, South Africa.

- Holze, H.; Schrader, L.; Buellesbach, J. Advances in deciphering the genetic basis of insect cuticular hydrocarbon biosynthesis and variation. Heredity 2020, 126, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HUTCHINSON, G.E. (1957) A treatise on limnology. (No Title) Volume I.

- Ingleby, F.C. Insect Cuticular Hydrocarbons as Dynamic Traits in Sexual Communication. Insects 2015, 6, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.; Seth, A.; Marcireau, A.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Hu, T.; Atayde, R. FlyCount: High-Speed Counting of Black Soldier Flies Using Neuromorphic Sensors. IEEE Sensors J. 2024, 25, 2861–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAMES, M.T. (1935) The genus Hermetia in the United States (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society 30, 165–170.

- Jang, E.B.; McInnis, D.O.; Kurashima, R.; Carvalho, L.A. Behavioural switch of female Mediterranean fruit fly, Ceratitis capitata: mating and oviposition activity in outdoor field cages in Hawaii. Agric. For. Èntomol. 1999, 1, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K.; Thormose, S.; Noer, N.; Schou, T.; Kargo, M.; Gligorescu, A.; Nørgaard, J.; Hansen, L.; Zaalberg, R.; Nielsen, H.; et al. Controlled and polygynous mating in the black soldier fly: advancing breeding programs utilizing quantitative genetic designs. J. Insects Food Feed. 11. [CrossRef]

- Insects to Feed the World. J. Insects Food Feed. 2024, 10, 1–353. [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; Tomberlin, J. Effects of adult body size on mating success of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (L.) (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). J. Insects Food Feed. 2021, 7, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Generalovic, T.N.; Ståhls, G.; Samayoa, A.C.; Nunes-Silva, C.G.; Roxburgh, H.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Ewusie, E.A.; Kenis, M.; Hanboonsong, Y.; et al. Global population genetic structure and demographic trajectories of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens. BMC Biol. 2021, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.D. Resource quality or harem size: what influences male tenure at refuge sites in tree weta (Orthoptera: Anostostomatidae)? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2006, 60, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimsey, L.S. The behaviour of male orchid bees (Apidae, Hymenoptera, Insecta) and the question of leks. Anim. Behav. 1980, 28, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KLÜBER, P., AROUS, E., JERSCHOW, J., FRAATZ, M., BAKONYI, D., RÜHL, M. & ZORN, H. (2024) Fatty acids derived from oviposition systems guide female black soldier flies (Hermetia illucens) toward egg deposition sites. Insect Science 31, 1231–1248.

- Klüber, P.; Arous, E.; Zorn, H.; Rühl, M. Protein- and Carbohydrate-Rich Supplements in Feeding Adult Black Soldier Flies (Hermetia illucens) Affect Life History Traits and Egg Productivity. Life 2023, 13, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pickering, A.; Kohler, R.E. Lords of the Fly: Drosophila Genetics and the Experimental Life. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 1995, 24, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzé, Z.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Johnson, R. Influence of Substrate Age and Interspecific Colonization on Oviposition Behavior of a Generalist Feeder, Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), on Carrion. J. Med Èntomol. 2020, 57, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubli, E. My favorite molecule. The sex-peptide. BioEssays 1992, 14, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laksanawimol, P.; Singsa, S.; Thancharoen, A. Behavioral responses of different reproductive statuses and sexes in Hermetia illucens (L) adults to different attractants. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambkin, C.L.; Sinclair, B.J.; Pape, T.; Courtney, G.W.; Skevington, J.H.; Meier, R.; Yeates, D.K.; Blagoderov, V.; Wiegmann, B.M. The phylogenetic relationships among infraorders and superfamilies of Diptera based on morphological evidence. Syst. Èntomol. 2012, 38, 164–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laturney, M.; van Eijk, R.; Billeter, J.-C. Last male sperm precedence is modulated by female remating rate inDrosophila melanogaster. Evol. Lett. 2018, 2, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laudani, F.; Campolo, O.; Latella, I.; Modafferi, A.; Palmeri, V.; Giunti, G. Does Hermetia illucens recognize sibling mates to avoid inbreeding depression? Èntomol. Gen. 2024, 44, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, S.F.; Flint, C.A.; Bahrndorff, S.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Kristensen, T.N. Reproductive output and other adult life-history traits of black soldier flies grown on different organic waste and by-products. Waste Manag. 2024, 181, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LEMKE, N.B. (2024) Artificial plant perches reveal sex-specific behavior in the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens. Theatre, Singapore Expo, Singapore.

- LEMKE, N.B. (2025) All About Lekking: A Comprehensive Examination of Lekking and the Lek Mating System in the Black Soldier Fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Preprints. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202501.0515/v1 [accessed ]. 29 May.

- Lemke, N.B.; Dickerson, A.J.; Tomberlin, J.K. No neonates without adults. BioEssays 2022, 45, e2200162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.; Li, C.; Dickerson, A.; Salazar, D.; Rollinson, L.; Mendoza, J.; Miranda, C.; Crawford, S.; Tomberlin, J. Heterogeny in cages: Age-structure and attractant availability impacts fertile egg production in the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens. J. Insects Food Feed. 20. [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.B.; Rollison, L.N.; Tomberlin, J.K. Sex-Specific Perching: Monitoring of Artificial Plants Reveals Dynamic Female-Biased Perching Behavior in the Black Soldier Fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Insects 2024, 15, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedo, P.; Salgado, S.; Oropeza, A.; Toledo, J. IMPROVING MATING PERFORMANCE OF MASS-REARED STERILE MEDITERRANEAN FRUIT FLIES (DIPTERA: TEPHRITIDAE) THROUGH CHANGES IN ADULT HOLDING CONDITIONS: DEMOGRAPHY AND MATING COMPETITIVENESS. Fla. Èntomol. 2007, 90, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luck, N.; Dejonghe, B.; Fruchard, S.; Huguenin, S.; Joly, D. Male and female effects on sperm precedence in the giant sperm species Drosophila bifurca. Genetica 2006, 130, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüpold, S.; Manier, M.K.; Puniamoorthy, N.; Schoff, C.; Starmer, W.T.; Luepold, S.H.B.; Belote, J.M.; Pitnick, S. How sexual selection can drive the evolution of costly sperm ornamentation. Nature 2016, 533, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macavei, L.I.; Benassi, G.; Stoian, V.; Maistrello, L.; Lanz-Mendoza, H. Optimization of Hermetia illucens (L.) egg laying under different nutrition and light conditions. PLOS ONE 2020, 15, e0232144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, P.D.; Priest, N.K.; Promislow, D.E.L. Female age and sperm competition: last-male precedence declines as female age increases. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2003, 270, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; McGuane, A.; Walsh, E.; Rusch, T.; Hjelmen, C.; Delclos, P.; Rangel, J.; Zheng, L.; Cai, M.; Yu, Z.; et al. Interaction of age and temperature on heat shock protein expression, sperm count, and sperm viability of the adult black soldier fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). J. Insects Food Feed. 2021, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malawey, A.S.; Mercati, D.; Love, C.C.; Tomberlin, J.K.; Stull, V. Adult Reproductive Tract Morphology and Spermatogenesis in the Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Ann. Èntomol. Soc. Am. 2019, 112, 576–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manas, F.; Labrousse, C.; Bressac, C. Plastic responses in sperm expenditure to sperm competition risk in black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens, Diptera) males. J. Insect Physiol. 2025, 161, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manas, F.; Piterois, H.; Labrousse, C.; Beaugeard, L.; Uzbekov, R.; Bressac, C. Gone but not forgotten: dynamics of sperm storage and potential ejaculate digestion in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 241205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manas, F.; Venon, P.; Yang, L.; Labrousse, C.; Bressac, C. Multiple mating is not driven by size and sperm management in black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). Èntomol. Exp. et Appl. 2025, 173, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markow, T.A. The secret lives of Drosophila flies. eLife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneguz, M.; Miranda, C.; Cammack, J.; Tomberlin, J. Adult behaviour as the next frontier for optimising industrial production of the black soldier flyHermetia illucens (L.) (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). J. Insects Food Feed. 2023, 9, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, D.J.; Omusula, P.; Holdinga, M.; Homan, T.; Carreira, A.S.; Vandendaele, P.; Derycke, J.-L.; Mweresa, C.K.; Mukabana, W.R.; van Loon, J.J.A.; et al. Field Evaluation of a Push-Pull System to Reduce Malaria Transmission. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0123415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyermans, R.; Broeckx, L.; Mondelaers, J.; Gorssen, W.; Frooninckx, L.; Janssens, S.; Van Miert, S.; Buys, N. Exploring the potential of crossbreeding to enhance black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) production. J. Insects Food Feed. 2025, 11, 1703–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, J.S.; Ibañez-Palacios, J.; Cardenas-Enriquez, D.P.; Luis-Alvares, J.H.; Liedo, P. Bi-environmental cage for colony management in the mass rearing of Anastrepha ludens (Diptera: Tephritidae). Insect Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MICHIELS, N.K. & DHONDT, A.A. (1989) Differences in male and female activity patterns in the dragonfly Sympetrum danae (Sulzer) and their relation to mate-finding (Anisoptera: Libellulidae). Odonatologica 18, 349–364.

- MILLER, W.E. (2005) Reproductive bulk in capital-breeding Lepidoptera. Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 59, 228–232.

- MOORE, P. (2014) Reproductive physiology and behaviour. In Evoltuion of Insect Mating Systems (eds D.M. SHUKER & L.W. SIMMONS), pp. 78–91Illustrated. Oxford University Press, United Kingdom.

- Morrow, E.H.; Gage, M.J. Sperm competition experiments between lines of crickets producing different sperm lengths. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2001, 268, 2281–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munsch-Masset, P.; Labrousse, C.; Beaugeard, L.; Bressac, C. The reproductive tract of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) is highly differentiated and suggests adaptations to sexual selection. Èntomol. Exp. et Appl. 2023, 171, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraro, T.; Lalanne, L.; Pelozuelo, L.; Calas-List, D. Mating and oviposition of a breeding strain of black soldier fly Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): polygynandry and multiple egg-laying. J. Insects Food Feed. 2024, 10, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S.; Ichiki, R.T.; Shimoda, M.; Morioka, S. Small-scale rearing of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), in the laboratory: low-cost and year-round rearing. Appl. Èntomol. Zoöl. 2016, 51, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]