Introduction

An estimated 10% of the population in some countries are being conceived through IVF [

1]. With clinical indications for IVF expanding, the proportion of children conceived through IVF will be increasing. Thus, the requirement to increase the effectiveness of such treatments including the economics and time-efficiency of selecting the most functionally viable embryo for transfer is acutely felt. Each clinic operates its own adapted and optimized protocols for embryo culture, testing, and transfer. The question is whether embryologists and decision-makers in the laboratory would be willing to adapt the protocol for the potential of having a more valuable screening test with the associated increase in the live birth rates. Physicians’ reluctance to change and adopt new technology is widely recognized [

2,

3]. However, Reproductive Medicine Physicians and embryologists have been more willing to do so. Such as with the adoption of PGT-A, embryologists had to change their protocols to match the operational requirements of the aneuploidy diagnostic test [

4,

5].

Into this space metabolomics has emerged as a new front runner as a promising non-invasive method for assessing blastocyst competence by analysing the biochemical composition of spent embryo culture media (SBM) [

6,

7]. Unlike traditional morphological assessment, metabolomics provides a functional snapshot of embryonic metabolism, offering insights into viability and implantation potential. Key metabolites are being correlated with developmental outcomes, supporting its use as a complementary selection tool in IVF [

8,

9]. Ongoing advances in analytical techniques and machine learning are enhancing its diagnostic value [

10,

11].

However, with increasing demands for better performance, efficacy standards and overall workload in IVF clinics; the need for the most robust, cost-effective, non-invasive, and user-friendly testing capabilities is recognized. The willingness to adapt clinical practice in order to adopt cutting-edge technology the technology must consider more the operational requirements of the user. Thus, requiring hatching [

12] and fresh media culturing prior to transfer or vitrification [

10,

13], is not as dramatic a change to IVF protocols as compared to what has happened previously.

Nevertheless, for the translation of “discovery concepts” from the research laboratory to use in IVF clinics; the practicality and efficacy of an SBM Metabolomic competency test for blastocyst-embryo selection has to face compromises and be modified to the reality of clinical practice.

In the development of a metabolomic assessment system of spent blastocyst media (SBM) we had a strict sample inclusion criteria: day5 PGT-A confirmed Euploid, hatched, FET IVF embryos only [

10,

12]. However, in everyday practicality the proposed test needs to be applied to fresh and frozen blastocyst transfer (FET). PGT-A testing and confirmation of Euploidy must not be a requirement. Whilst “day5” hatched has to be flexible to accommodate blastocysts in the process of hatching but not fully hatched at day -5/ 6 even day-7

in vitro culture. In addition the output data has to be informative and yet easily understandable by the embryologist.

Furthermore, the yes or no concept, as seen in PGT-A, of euploidy versus aneuploidy, has proved unreliable and litigious [

14,

15]. Indeed, given all the stages at which a pregnancy failure can occur; a successful pregnancies (and IVF pregnancies) are a function of probability and not certainty [

16]. Thus, at best a test can only indicate a probability of success, and selection based on such tests, tips the balance of probabilities in favour of successful blastocyst-embryo implantation and live birth.

In this respect an embryologist faces multiple dilemmas: A simple high, versus low probability may be completely unhelpful as the choice may be between all high or all low probability scoring IVF blastocysts. This has proved a particularly contentious issue in aneuploidy testing, as all PGT-A abnormal blastocyst-embryos are discarded, regardless if the issue in reporting is of complex mosaic or only segmental positives [17, 18]. There is also accuracy and precision issues; the always present false positive and false negative rate of a test [

19]. Thus, particularly in reproductive medicine, a single test result given as a definitively determinist is not only wrong, as in a significant number of times false positive, but also extremely detrimental. For example, in the adoption of PGT-A testing, this has resulted in women with low probability IVF Success going to Zero prospect of achieving a successful pregnancy; as potentially viable blastocyst, scored by PGT-A as “defective”, have been discarded [

20].

Thus, a graduation scale of probability of implantation/viability in any assessment test of which blastocyst-embryo to select for transfer or storage, is much more clinically valid. This is not only a clinical matter of treatment management toward successful IVF, but also for holistic wellness; managing patient emotional expectations.

Methods and Data Samples

Moving from Ai/ML “Black Box” algorithm to a functional probabilistic algorithm

Further interrogation of our Ai/ML algorithms identified which markers alone and in ratio with specific other peaks, significantly correlated with outcomes.

A generic rule is that you need a minimum of 10 individual sample entries per variable being utilised in your Ai/ML system build. This then has to be tested by a unique data set not previously seen by the algorithm (a nieve data set). The entire Ai/ML algorithm process can remain unclear with no functional insight but yield answers. The confidence level in such systems is largely dependent on the quality of inputted data and its sample n-value, i.e. approaching millions of samples for complex factor/variable computing algorithms [

22].

Reducing the number of variables in an algorithms makes a system more robust and less prone to overfitting data, which is a major weakness of Ai/ML. However, this can be at the expense of sensitivity (more so than specificity) and a compromise has to be reached with respect to available data. By normalising we reduced algorithms inputted factors by half i.e. one correlating metabolite peak divided by another correlating peak.

We moved this further in the development of PMT-PC by only considering the mechanistic biological significance of only using the ratio of the most statistically significant associated identified metabolite peaks that were also potentially seen in day5 day6 and day7 blastocyst-embryos in the process of hatching rather than just being present in fully hatched embryos.

In moving to a more practical approach to SBM samples that will be tested, we tailored the prediction algorithm and in so doing we took a Bayesian probability approach to the reporting algorithm. Thus providing a graduation of probability and not a yes/no or even high or low probability classification.

In this development process 400 pre outcome analysed SBM MALDI-ToF mass spectra from day 5 hatched, and transferred blastocyst were selected from our database of prospectively analysed SBM spectra for comparison. Fifteen of the selected spectra were subsequently rejected for incomplete/uncertain outcome data or poor spectra not matching QC checks. Of the remaining three hundred and eight five, 193 (50.1%) resulted in viable implantation pregnancies (detectable heart beat at 16 weeks gestation). The remaining 192 failed to implant or were, biochemical and first trimester, losses.

Results

Previous Ai/ML analysis of SBM spectra had identified thirty five metabolite mass peaks between 250m/z and 1000m/z correlating with blastocyst implantation only and/or viable IVF Embryo implantation (at 16 week gestation) [10, 12, 21]. Analysis showed that seventeen ratio pairs (Mr.), from these mass peak identified metabolites, had the highest statistical association with implantation and or viable implantation.

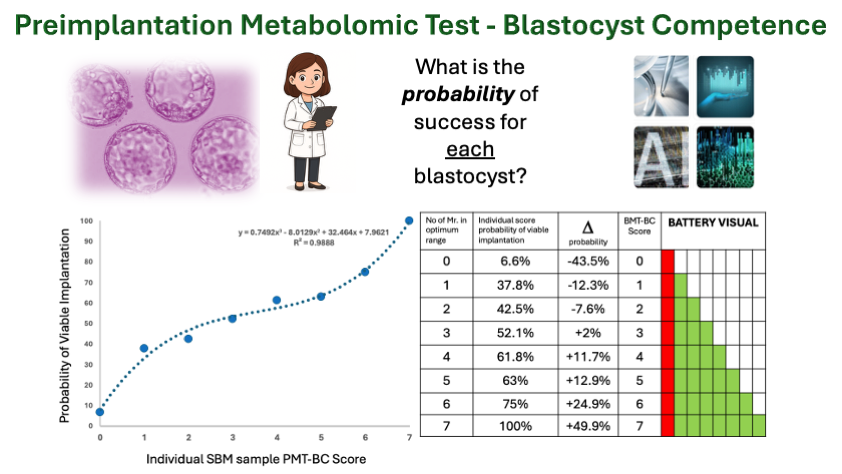

The optimum arithmetic range for the individual Mr. that correlated with implantation and viable implantation was then determined (see figure 1).

In multiple comparisons seven pairs of peak mass defined ratio (Mr.) showed substantive changes in probability. Semi- independent, these Mr. biomarkers displayed additive increase in a Bayesian type scoring system; such that the more Mr. in the optimum range the greater the probability of implantation and viable pregnancy (figure 2).

However, consistent with the fact that the input data contained a significant number of viable blastocysts (metabolically competent) that resulted in failed clinical viable transfer, the negative predictive value of the test i.e. lack of the metabolic biomarkers in optimum ratio, showed a much stronger and statistically significant regression than the positive predictive value because of the number of metabolic competent blastocysts (BMT-BC -true positives/TP ) inherently mislabelled as (clinical) true negatives (TN). (Figure 3A). Never-the-less using a Bayesian type approach to PPV and NPV calculation, a cut off was established that those scoring less than PMT-BC of 3 had (a high confidence score of) significantly lower probability of IVF success and those scoring greater than three, a (high confidence score of) significantly higher probability of IVF success. (figure 3B). Furthermore, a probability of success could be assigned to every score and therefore individually to each IVF Blastocyst-embryo.

Discussion

The next major step in assisted reproductive technology is the ability to select the IVF blastocyst Embryo that will implant and result in a life birth. Thus, evaluation tests have been introduced; from visual (Gardner scoring) and morphometrics (time lapse and image analysis); genetics via aneuploid detection (PGT-A); and now biochemistry signatures through metabolomics [

6,

7].

Becoming pregnant and giving birth relies on multiple factors and circumstances occurring and is therefore a matter of when biology, physiology and biochemistry start to align [

23]. Maternal age can alter their relative effects but it remains a matter of “chance” [

24]. Thus, test claiming definitive classifications, and extrapolated in commercial marketing were always unrealistic and going to lead to litigation [

14,

15].

Yet research into identifying tests for blastocyst/embryo competence, the quantitative scientific mathematics of certainty - accuracy (TP + TN/ (TP + TN + FP + FN) has dominated the approach. Despite, one of the many major stumbling block has been the lack of scientific certainty surrounding the definition of outcome groups and identification of the competent blastocyst-embryo against which we evaluate biomarkers:

Firstly, is the definition of success. Blastocyst Implantation alone does not guarantee life birth and is only one of the 2 tissue specific functional feature of blastocyst competence; trophoblast cell competence and not, but it is linked to, inner cell mass competence [

25].

Secondly, although the number of blastocyst achieving live birth can be counted; that is not all the competent IVF Blastocyst/embryos, as there are many other causes of IVF failure which are due to maternal physiological factors, such as endometrial physiology [

26].

Thus, many IVF competent Blastocyst-Embryo fail, and are miss classified as incompetent and true positives and true negatives are unknown; FN and FP cannot be calculated and therefore neither can accuracy. The in ability to accurately identify the target population – IVF competent blastocyst-embryos to transfer - makes identification of feature that are characteristic, and therefore act as biomarkers distinguishing the incompetent IVF blastocyst, particularly difficult.

However, the mathematics of chance and probability is well developed and extended in applications of biochemistry and biological game theory [27, 28]. In IVF we control some key factors and, on average, 30% of blastocyst transfers result in success. Furthermore, knowing that life birth can only arise from within the IVF competent blastocyst-embryo competent population, we have a derived defined population of success which should have an enrichment, or greater representation, of the defining biomarkers than in the non-live birth population. Thus, the mathematics of probability association that tests hypotheses, such as a Bayesian approach, are required. We chose to compare near equal numbers of Viable implanting versus non-implanting and failing pregnancies to enrich the sampled data set of metabolic biomarkers of blastocyst-embryo competence.

Comparing relative probabilities of success, be it implantation or viability at 16 weeks of gestation, differences in the percentage incidence of features therefore identifies biomarkers of the Competent IVF blastocyst-embryo [

29]. The mathematics of chance are not straight forward nor simply linear; but the more associating biomarkers the greater the probability of success and is a process not susceptible to Ai/ML algorithm overfitting [

30].

Here we have followed a Bayesian approach incorporating prior knowledge gained from our Ai/ML studies of metabolomic spectral patterns and IVF blastocyst outcomes, and Bayesian definition of positive predictive value (p Viable|Test+) and negatives predictive value (p Not viable|Test-). Individually each BMT-BC score of number of Mr. in optimum ratio had an increasing probability of correctly identifying viable implantation, clinically the most metabolically competent blastocyst-embryo to transfer.

The cumulative enrichment of implanting versus non- implanting blastocysts at each cutoff category e.g. less than 3 or equal & greater than 4 Mr. ratio pairs at optimum - PMT-BC Score, were calculated.

This, along with calculated positive and negative predictive values, were more biological informative: Negative predictive values correlated in a tight liner regression against Mr. PMT-BC cut off values (r=0.99 ). However, positive prediction values correlated, but not in a simple linear regression (r= 0.94). This is entirely consistent with a significant minority of IVF blastocyst transfers failures being due to endometrial receptivity and other issues, but not blastocyst-embryo competence. This creates a bias of inaccuracy, or deviation, for PPV but not NPV (which PPV should mirror). In clinical IVF success situations this deviation from predicted biological success in pregnancy is biologically and clinically informative of the nature of an individual’s infertility.

Thus, absence of the identified metabolic markers described by the PMT-BC test (zero or low number of Mr. at optimum), is indicative of probable non-viability and implantation incompetent IVF blastocyst-embryos. Conversely, presence of increasing metabolic biomarkers in ratio, identifies viable/competent blastocyst-embryo. Therefore any subsequent failure after transfer of high PMT-BC scoring Blastocyst-embryo SBM samples is indicating infertility due to endometrial receptivity and other reproductive physiology causes/issues.

PMT-BC is a robust preimplantation metabolic blastocyst competence test: Orthogonal to Gardner -like visual morphometrics and PGT-A evaluation, matching real-life needs of the IVF-Embryology clinic: Stratifying the probability of a pre-transfer IVF Blastocyst-Embryo for successful viable implantation. Furthermore, a high score in PMT-BC is also addressing the identification and clinically defining of endometrial receptivity failure, cases & incidence; vis-à-vis the identification of competent blastocysts, true positives, but clinical negatives/failed IVF transfers.

Ethical Approval

All couples gave consent for the culture media to be used. The study was approved by VCRM’s Institutional Review Board (fshararaVCRMED20230126).

Conflicts of Interest Declaration

Dr Ray K Iles is Chief Scientific officer of Embryomic Ltd and the Inventor of patents EP2976647B1 and EP3198279B1; Dr Sara Nasser is a Medical Advisor to Embryomic Ltd. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kushnir, V.A.; Smith, G.D.; Adashi, E.Y. The Future of IVF: The New Normal in Human Reproduction. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 29, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nov, O.; Schecter, W. Dispositional resistance to change and hospital physicians' use of electronic medical records: A multidimensional perspective. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2012, 63, 648–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarantou, V.; Kazakopoulou, S.; Chatzoudes, D.; Chatzoglou, P. Resistance to change: an empirical investigation of its antecedents. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2018, 31, 426–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harton, G.; Braude, P.; Lashwood, A.; Schmutzler, A.; Traeger-Synodinos, J.; Wilton, L.; Harper, J.C. ESHRE PGD consortium best practice guidelines for organization of a PGD centre for PGD/preimplantation genetic screening. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 26, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deq229. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F.; Coonen, E.; Goossens, V.; Kokkali, G.; Rubio, C.; Meijer-Hoogeveen, M.; Moutou, C.; Vermeulen, N.; De Rycke, M.; ESHRE PGT Consortium Steering Committee. ESHRE PGT Consortium good practice recommendations for the organisation of PGT. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmuidinaite, R.; Sharara, F.I.; Iles, R.K. Current Advancements in Noninvasive Profiling of the Embryo Culture Media Secretome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesaik, J. Noninvasive Biomarkers of Human Embryo Developmental Potential PREprints.org. 2025, https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202504.1568/v1.

- Vergouw, C.; Botros, L.; Roos, P.; Lens, J.; Schats, R.; Hompes, P.; Burns, D.; Lambalk, C. Metabolomic profiling by near-infrared spectroscopy as a tool to assess embryo viability: a novel, non-invasive method for embryo selection. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seli, E.; Vergouw, C.G.; Morita, H.; Botros, L.; Roos, P.; Lambalk, C.B.; Yamashita, N.; Kato, O.; Sakkas, D. Noninvasive metabolomic profiling as an adjunct to morphology for noninvasive embryo assessment in women undergoing single embryo transfer. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. I. Sharara, S.A. Butler, R.J. Pais, R. Zmuidinaite, S. Keshavarez, R.K. Iles “BESST, a Non-Invasive computational Tool for Embryo selection using mas spectral profiling of embryo culture media. EMJ Repro Health, 2019, 5(1):59-60, https://www.emjreviews.com/reproductive-health/abstract/besst-a-non-invasive-computational-tool-for-embryo-selection-using-mass-spectral-profiling-of-embryo-culture-media/.

- Wang, R.; Pan, W.; Jin, L.; Li, Y.; Geng, Y.; Gao, C.; Chen, G.; Wang, H.; Ma, D.; Liao, S. Artificial intelligence in reproductive medicine. Reproduction 2019, 158, R139–R154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iles, R.K.; Zmuidinaite, R.; Iles, J.K.; Nasser, S. The influence of Hatching on blastocyst metabolomic analysis: Mass Spectral analysis of Spent blastocyst media in Ai/ML prediction of IVF Embryo implantation potential– To Hatch or not to Hatch? PREprints 2025. [CrossRef]

- Simopoulou, M.; Sfakianoudis, K.; Rapani, A.; Giannelou, P.; Anifandis, G.; Bolaris, S.; Pantou, A.; Lambropoulou, M.; Pappas, A.; Deligeoroglou, E.; et al. Considerations Regarding Embryo Culture Conditions: From Media to Epigenetics. Vivo 2018, 32, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducharne, J. IVF Patients Say a Test Caused Them to Discard Embryos. Now They’re Suing. TIME Magazine March 6 2025 https://time.com/7264271/ivf-pgta-test-lawsuit/.

- Klipstein, S.; Daar, J. Impact of shifting legal and scientific landscapes on in vitro fertilization litigation. Fertil. Steril. 2023, 119, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Machado, H. Uncertainty, risks and ethics in unsuccessful in vitro fertilisation treatment cycles. Heal. Risk Soc. 2010, 12, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.; Pennell, C.E.; McLean, N.J.; Oddy, W.H.; Newnham, J.P. The over-estimation of risk in pregnancy. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 32, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, P. Clinical management of mosaic results from preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) of blastocysts: a committee opinion. Fertility and Sterility. 2020; 114(2):246-54.

- Simon, R. Sensitivity, Specificity, PPV, and NPV for Predictive Biomarkers. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2015, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viville, S.; Aboulghar, M. PGT-A: what’s it for, what’s wrong? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2025, 42, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iles, R.K., Zmuidinaite, R., Iles, J.K., Nasser, S. The influence of defining desired outcomes on prediction algorithms: Mass Spectral analysis of Spent blastocyst media in Ai/ML prediction of IVF Embryo implantation potential – Implantation, or Viability, or both? PREprints 2025.

- Aliferis, C.; Simon, G. Overfitting, Underfitting and General Model Overconfidence and Under-Performance Pitfalls and Best Practices in Machine Learning and AI. In: Simon, G.J., Aliferis, C. (eds) Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Health Care and Medical Sciences. Health Informatics 2024. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Stirnemann, J.J.; Samson, A.; Bernard, J.-P.; Thalabard, J.-C. Day-specific probabilities of conception in fertile cycles resulting in spontaneous pregnancies. Hum. Reprod. 2013, 28, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konje, J.; Ladipo, O. (2021, August 31). Sex and Conception Probability. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health. Retrieved 28 Jul. 2025, from https://oxfordre.com/publichealth/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190632366.001.0001/acrefore-9780190632366-e-179.

- Chousal, J.N.; Morey, R.; Srinivasan, S.; Lee, K.; Zhang, W.; Yeo, A.L.; To, C.; Cho, K.; Garzo, V.G.; Parast, M.M.; et al. Molecular profiling of human blastocysts reveals primitive endoderm defects among embryos of decreased implantation potential. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 113701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, W.; Li, D. Recurrent implantation failure: A comprehensive summary from etiology to treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 13, 1061766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, S.; Kreft, J.-U.; Schroeter, A.; Pfeiffer, T. Use of Game-Theoretical Methods in Biochemistry and Biophysics. J. Biol. Phys. 2008, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Pennington, S.R.; Parnell, A.C. Bayesian methods for proteomic biomarker development. EuPA Open Proteom. 2015, 9, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Zhang, F.; Burman, C.; Sharples, L. Bayesian Solutions for Assessing Differential Effects in Biomarker Positive and Negative Subgroups. Pharm. Stat. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, J.L.; Choma, M.A.; Onofrey, J.A. Bias in medical AI: Implications for clinical decision-making. PLOS Digit. Health 2024, 3, e0000651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).