1. Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 2–4% of adult malignancies worldwide [

1]. The incidence of RCC is lower in Africa (age-standardized rate 2–5 per 100,000) than in developed regions [

1], but increasing use of imaging is expected to detect more localized renal masses even in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Historically, most patients in sub-Saharan Africa present with advanced RCC, and management has primarily involved open radical nephrectomy due to its broad applicability and cost-effectiveness in resource-limited settings [

1]. Nephron-sparing approaches like partial nephrectomy have been underutilized in LMICs, often limited by late presentation, limited surgical expertise, and lack of advanced surgical technology [

1]. However, the global shift towards earlier-stage diagnosis (nearly 50% of renal tumors are stage T1 at diagnosis in some series) has led to an emphasis on nephron-sparing surgery to preserve renal function without compromising oncologic control [

2].

Partial nephrectomy (PN) is now firmly established as the gold standard for management of clinically localized (cT1) renal tumors in high-income settings [

2,

3]. Current international guidelines from the American Urological Association (AUA) and European Association of Urology (EAU) recommend PN for all T1 tumors when technically feasible [

2,

3]. This paradigm shift followed evidence that PN provides oncological efficacy equivalent to radical nephrectomy (RN) for small renal masses, while offering superior functional preservation and reducing the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and associated cardiovascular morbidity [

2,

3]. In a seminal population-based study, Huang et al. reported that patients undergoing radical nephrectomy for T1 tumors had a 2-fold greater decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and significantly higher risk of overall mortality and cardiovascular events compared to those undergoing partial nephrectomy [

9]. These findings underscored that radical nephrectomy for small tumors may represent overtreatment, as removal of an entire kidney can induce CKD and its sequelae, whereas nephron-sparing surgery better preserves renal function and long-term health [

2,

4]. Indeed, nephron-sparing surgery typically results in only about a 20–25% decrease in overall eGFR (reflecting the nephron loss of the resected portion and ischemic injury), versus the ~50% loss that would be expected if an entire kidney were removed [

5]. Preservation of renal function is particularly critical in LMIC contexts, where access to dialysis or transplantation for ESRD is extremely limited.

Minimally invasive approaches (laparoscopic and robotic PN) have increasingly supplanted open surgery in high-resource settings due to advantages in perioperative morbidity and recovery. However, many LMIC centers lack expensive robotic systems and the laparoscopic expertise may be scarce[

2]. Open partial nephrectomy (OPN) remains a relevant and vital technique for nephron-sparing surgery in resource-constrained environments [

1,

2]. Notably, evidence suggests that oncologic and functional outcomes of OPN are equivalent to those of minimally invasive PN for localized tumors [

2]. For larger or more complex tumors (e.g., cT1b–T2), OPN offers tactile feedback and versatility, and experienced centers have reported comparable cancer control with OPN as with robotic PN [

2]. In the absence of advanced technology, demonstrating the feasibility and outcomes of OPN in an LMIC setting is important to support wider adoption of nephron-sparing surgery in such regions.

Here we present a multicenter cohort study evaluating the feasibility, renal functional outcomes, and oncologic efficacy of open partial nephrectomy for localized renal tumors in Cameroon, a lower-middle-income country. We report the perioperative and follow-up outcomes of 38 patients with clinical T1–T2 N0M0 renal tumors who underwent standard open PN at two hospitals. We focus on key measures of success including the “Trifecta” outcome (tumor resection with negative margins, limited ischemia, and no significant complications), renal function preservation at 1 year, and 2-year recurrence-free survival. We hypothesize that OPN can be safely performed in an LMIC setting with outcomes approaching those reported in high-resource centers, thereby providing effective cancer control while mitigating CKD risk in a population with limited access to renal replacement therapy. This study aims to inform urologic oncology practice in LMICs by highlighting the potential of open nephron-sparing surgery to improve care for localized kidney cancer.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all adults who underwent open partial nephrectomy for localized (cT1–T2, clinical N0M0) renal tumors at two tertiary hospitals in Cameroon between 2015 and 2024. The participating centers were Regional Hospital Bamenda (a public referral hospital) and Nkwen Baptist Hospital (a faith-based teaching hospital), which together serve a broad catchment in the North-West region. Surgical and ethical approvals were obtained from institutional review boards of both hospitals. Patient records were de-identified and analyzed in compliance with ethical standards.

2.2. Patient Selection:

We included 38 consecutive patients (age ≥18 years) with a solitary, sporadic renal tumor who were deemed candidates for nephron-sparing surgery. All patients had preoperative imaging (contrast-enhanced CT in 34 cases, MRI in 4) demonstrating a unilateral renal mass suspicious for RCC, without evidence of nodal or distant metastasis. Tumor stage was cT1a (≤4 cm) in 16 patients, cT1b (>4–7 cm) in 19 patients, and cT2 (>7 cm) in 3 patients (all cT2a ≤10 cm). Patients with bilateral tumors, von Hippel–Lindau or hereditary syndromes, or gross vascular invasion were not included. Partial nephrectomy was performed electively in all cases, either for relative indications (tumor in a patient with normal contralateral kidney) or absolute indications (e.g. solitary kidney or baseline CKD). Three patients (7.9%) had a solitary functioning kidney at presentation (two due to prior contralateral nephrectomy for trauma, one due to renal agenesis), making nephron-sparing imperative.

2.3. Preoperative Evaluation:

Patient demographics, comorbidities, and preoperative laboratory values were recorded. Hypertension was present in 15 patients (39%) and diabetes in 8 (21%); six patients (16%) had both. Baseline renal function was assessed by estimated GFR using the CKD-EPI 2021 creatinine equation (which excludes race coefficient) [

6]. The mean preoperative eGFR was 87 mL/min/1.73m

2 (SD ±18). Chronic kidney disease staging followed KDIGO criteria. Four patients (10.5%) had preexisting CKD stage 3a (eGFR 45–59), and none had stage ≥3b (eGFR <45) at baseline. Tumor complexity was quantified using the RENAL nephrometry score [

18] on preoperative imaging, assigned by a radiologist. Low complexity was defined as RENAL <7, moderate 7–9, and high ≥10 [

7]. In our cohort, 21 tumors (55%) were low complexity, 16 (42%) moderate, and 1 (3%) high complexity (RENAL score 11).

Table 1 summarizes the patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, including tumor features.

2.4. Surgical Technique:

All surgeries were performed by two consultant urologists (one at each center) with prior open PN experience. A transperitoneal open approach was used in 30 cases, and a retroperitoneal flank approach in 8 cases (selected for posterior tumors). Standard partial nephrectomy technique was followed in all: after intraoperative ultrasound localization (used in 10 cases) and renal artery isolation, the kidney was partially mobilized. In 32 patients (84%), warm ischemia was applied by hilar clamping; 5 patients (13%) had off-clamp resection of small exophytic tumors, and 1 solitary-kidney patient (3%) underwent cold ischemia (renal artery clamped with ice slush cooling) to permit a longer resection time. For warm ischemia, surgeons strove to limit clamp time to ≤25 minutes, consistent with renal ischemia safety recommendations [

8]. Cold ischemia (in the solitary kidney case) enabled a longer safe ischemia period (~40 minutes) while avoiding warm ischemic injury. Tumor resection was performed with a sharp margin of normal parenchyma; enucleation was not routinely used except for purely exophytic small tumors. Collecting system entries were repaired with absorbable suture. Renorrhaphy was done with sliding-clip technique using interrupted 2-0 Vicryl sutures over bolster material in most cases. No intraoperative ultrasound polar ice or radiofrequency ablation adjuncts were used.

2.5. Intraoperative and Postoperative Data:

Intraoperative variables recorded included ischemia type (warm vs cold vs none) and duration of ischemia in minutes (warm ischemia time, WIT), estimated blood loss (EBL, in mL), transfusion requirement, and any intraoperative complications. Postoperative variables included analgesic modality, time to drain removal, length of hospital stay (LOS), and 30-day complications. Complications were graded using the Clavien–Dindo classification. “Major” complications were defined as Clavien grade ≥III (requiring surgical or radiologic intervention), whereas grade I–II were considered minor. All patients received prophylactic antibiotics and thromboprophylaxis per standard protocol. Serum creatinine was measured on postoperative days 1, 2, and at discharge, and again at follow-up visits.

2.6. Pathological Evaluation:

Resected specimens were sent for histopathology at a centralized laboratory. Tumor histologic subtype, Fuhrman/ISUP nuclear grade, pathologic tumor stage, and surgical margin status were determined. A positive margin was defined as the presence of tumor cells at the inked resection surface. “R0 resection” was defined by negative surgical margins. Pathologic staging followed AJCC 8th edition TNM criteria.

2.7. Follow-Up and Outcomes:

Patients were followed with periodic clinical visits and imaging per institutional protocol (typically ultrasound or CT at 6 months, then annually for 5 years for malignant tumors). Serum creatinine was measured at each follow-up to monitor renal function. For functional outcomes, we recorded the latest available eGFR within 12–15 months postoperatively for each patient (12-month eGFR). Percent change in eGFR from baseline to 12 months was calculated to assess renal function preservation. Our primary oncologic outcome was recurrence-free survival (RFS) at 2 years. Recurrence was defined as radiologically confirmed local tumor bed recurrence or distant metastasis. Time to recurrence was calculated from surgery to the date of first recurrence; patients without recurrence were censored at last follow-up. Two-year RFS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Overall survival was also tracked, although the study duration and sample size were insufficient for robust survival analysis.

2.8. Definition of Trifecta:

We evaluated a composite “Trifecta” outcome as a measure of optimal surgical success [

7]. For this study, Trifecta was defined as the simultaneous achievement of: (1) negative surgical margin (R0 resection); (2) limited warm ischemia (WIT ≤25 minutes); and (3) absence of any postoperative complication of Clavien–Dindo grade ≥II. This definition aligns with prior literature emphasizing negative margin, minimal ischemia, and no significant complications as key goals of partial nephrectomy [

3,

7]. (Notably, some authors include a functional outcome in the trifecta [

3], but we focused on perioperative criteria readily assessed at discharge.) We also assessed the “optimal” outcome sometimes termed “pentafecta” in literature (which adds no CKD upstaging and tumor <4 cm) for exploratory analysis [

9], but our sample was too small for meaningful pentafecta rates, so we primarily report the Trifecta achievement rate.

2.9. Statistical Analysis:

Data were analyzed using SPSS v26. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]) as appropriate. Categorical variables are given as counts and percentages. Comparison between groups (e.g., by center or complexity) used the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U for continuous variables. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to estimate RFS, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We performed univariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with two key outcomes: ≥20% decline in eGFR at 12 months, and failure to achieve trifecta. Variables assessed included patient age, comorbidities (hypertension/diabetes), tumor size and RENAL complexity, solitary kidney status, ischemia time, and EBL. Owing to the limited sample, a parsimonious multivariable logistic regression was then constructed including variables with p<0.20 on univariable analysis. Odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs are reported. A two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are presented in tables and figures with anonymized patient identifiers.

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4 and

Table 5 detail the patient characteristics, perioperative parameters, and outcomes.

Figure 1 presents the Kaplan–Meier curve for 2-year recurrence-free survival.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show forest plots of the multivariable regression analyses for predictors of significant eGFR decline and trifecta non-achievement, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

A total of 38 patients met inclusion criteria, with 27 patients (71%) treated at Regional Hospital Bamenda and 11 (29%) at Nkwen Baptist Hospital. Sociodemographic and clinical features are summarized in

Table 1. The cohort had a median age of 56 years (range 34–74) with male predominance (n=24, 63%). Most of the participants (68%) had at least one comorbidity with hypertension being the most common (34%), followed by diabetes (21%). Six patients (16%) had a history of both hypertension and diabetes, and three patients (8%) had a solitary kidney at the time of surgery (two due to previous contralateral nephrectomy and one congenital single kidney). Presenting symptoms included flank pain in 6 patients (16%), gross hematuria in 3 (8%), and incidentally detected asymptomatic tumors in 29 (76%). All tumors were unilateral and organ-confined on imaging (cT1–T2, N0). Tumor laterality was evenly split (19 left, 19 right). Mean tumor diameter was 4.6 ± 2.1 cm. By clinical stage, 16 tumors (42%) were cT1a (≤4 cm), 19 (50%) cT1b (>4–7 cm), and 3 (8%) cT2 (>7–10 cm). No patient had radiologic evidence of lymph node involvement or metastasis at diagnosis. Tumor complexity by RENAL nephrometry score was low in 21 cases (55%), moderate in 16 (42%), and high in only 1 case (3%). Notably, the single high-complexity tumor (RENAL 11, 8.5 cm upper pole mass) was in a solitary kidney patient. Preoperative renal function was generally preserved: mean baseline serum creatinine was 1.02 ± 0.3 mg/dL and mean eGFR was 86.7 ± 17.8 mL/min/1.73m

2. Four patients (10.5%) had baseline eGFR in the 45–60 range (CKD stage 3a), and none were below 45.

3.2. Perioperative Parameters

Intraoperative and immediate postoperative outcomes are detailed in

Table 2. All 38 patients underwent successful partial nephrectomy with no conversions to radical nephrectomy. The surgical approach was transperitoneal in 30 cases (79%) and retroperitoneal flank in 8 cases (21%). Renal artery clamping was utilized in 33 patients (87%): warm ischemia in 32 and cold ischemia in one; while 5 patients (13%) had off-clamp resection (all tumors <3 cm and exophytic). Among the 33 clamped cases, the mean warm ischemia time was 17.7 ± 4.8 minutes; median WIT was 18 minutes (IQR 15–20). Only one patient (3%) exceeded the 25-minute warm ischemia threshold (this was the solitary kidney case in whom cold ischemia was induced; his

warm ischemia time was effectively 0, with 40 minutes of cold ischemia). The renal hilum was clamped en bloc in all but 2 cases, where selective segmental artery clamping was performed for polar tumors. No patient received renal arterial perfusion with cardioplegia; in the solitary kidney case, surface cooling with ice slush was used to mitigate warm ischemia.

Mean estimated blood loss was 380 ± 240 mL. Nine patients (24%) had EBL >500 mL, of whom four required intra- or postoperative blood transfusion (overall transfusion rate 10.5%). The largest EBL was 1200 mL in a patient with a 7 cm hilar tumor; that patient received two units transfused. There were no intraoperative deaths. Intraoperative complications occurred in 2 patients (5.3%): one minor capsular tear of the spleen managed with hemostatic agents, and one diaphragmatic pleural tear requiring chest tube placement (both occurred during upper pole tumor resections). No intraoperative vascular injuries to the renal pedicle or vena cava were encountered.

All patients had uneventful recoveries from anesthesia. Postoperative analgesia was managed with epidural infusion in 12 patients (32%) and intravenous opioid patient-controlled analgesia in 26 (68%). Prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin was given starting POD1 in all. The mean length of hospital stay was 6.3 ± 2.1 days (median 6, range 3–12). Drains were placed in 30 patients (79%) and removed at a median of 4 days (range 2–7) post-op, once output was minimal and serous.

As shown in

Table 2, no patient experienced a major postoperative complication (Clavien–Dindo grade III or higher). Thirteen patients (34%) had minor complications within 30 days. Seven patients (18%) had grade I issues, including mild ileus (n=3), which resolved with conservative management, transient fever (n=4) and localized wound seroma (n=1). Six patients (16%) had grade II complications: four developed treatable infections (two urinary tract infections and two hospital-acquired pneumonias, all managed with antibiotics), and two patients received postoperative blood transfusions for anemia (both had hemoglobin <8 g/dL on day 1). Notably, no patients required a return to the operating room or other invasive intervention postoperatively, and there were zero perioperative deaths. The absence of any Clavien III–V complications indicates a favorable safety profile for OPN in this series.

Pathological outcomes are summarized in

Table 3. On final histology, 35 of 38 tumors (92.1%) were malignant RCCs and 3 (7.9%) were benign (oncocytoma in 2, angiomyolipoma in 1). Among RCC subtypes, clear cell RCC was most common (28 cases, 74% of total), followed by papillary RCC (6 cases, 16%) and chromophobe RCC (1 case, 2.6%). The remaining cancers included

“unclassified” RCC

. Pathologic T stage was pT1a in 15 cases, pT1b in 17, and pT2a in 3, matching the clinical staging in most; one tumor was upstaged to pT3a due to microscopic renal vein invasion. Fuhrman nuclear grade (ISUP grade) among RCCs was grade 1 in 5 cases, grade 2 in 15, grade 3 in 12, and grade 4 in 3 cases. All surgical margins were negative in 37 patients (97.4%). One patient (2.6%) had a positive surgical margin, which occurred in a 7 cm hilar clear cell RCC resected under warm ischemia (frozen section was not available). For that patient, close surveillance was adopted (and no recurrence has been detected at 18 months).

All patients had at least 12 months of follow-up, with a median follow-up of 28 months (range 12–54 months). Oncologic outcomes were excellent. Only 2 patients (5.3%) experienced tumor recurrence (

Table 3). One was the patient with a positive margin, he developed a local recurrence in the ipsilateral kidney bed at 18 months, managed successfully with completion radical nephrectomy. The second was a patient with a pT1b high-grade clear cell RCC (8 cm, Fuhrman grade 4) who developed pulmonary metastases 2 years post-surgery; he was started on systemic therapy (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and remains alive with stable disease at last contact. The actuarial 2-year recurrence-free survival was 94.7% (95% CI ~85–100%) (

Figure 1). There were no cancer-related deaths in the cohort; cancer-specific survival is 100% to date. One patient (noted above with metastases) is alive with disease. The remaining patients show no evidence of disease at last follow-up. One patient died of a non-cancer cause (stroke) 30 months after surgery, yielding an overall survival of 97.4% at a median 30 months.

3.3. Renal Functional Outcomes

Renal function was well preserved in the cohort. The mean serum creatinine increased modestly from 1.02 mg/dL preoperatively to 1.26 mg/dL at 12 months. Mean eGFR declined from 86.7 mL/min/1.73m

2 pre-op to 75.1 mL/min/1.73m

2 at 12 months. This corresponds to an average decline of 11.6 mL/min/1.73m

2, or 13.4% of baseline eGFR. The median percent eGFR change at 1 year was –12.2% (IQR –5.4% to –18.9%).

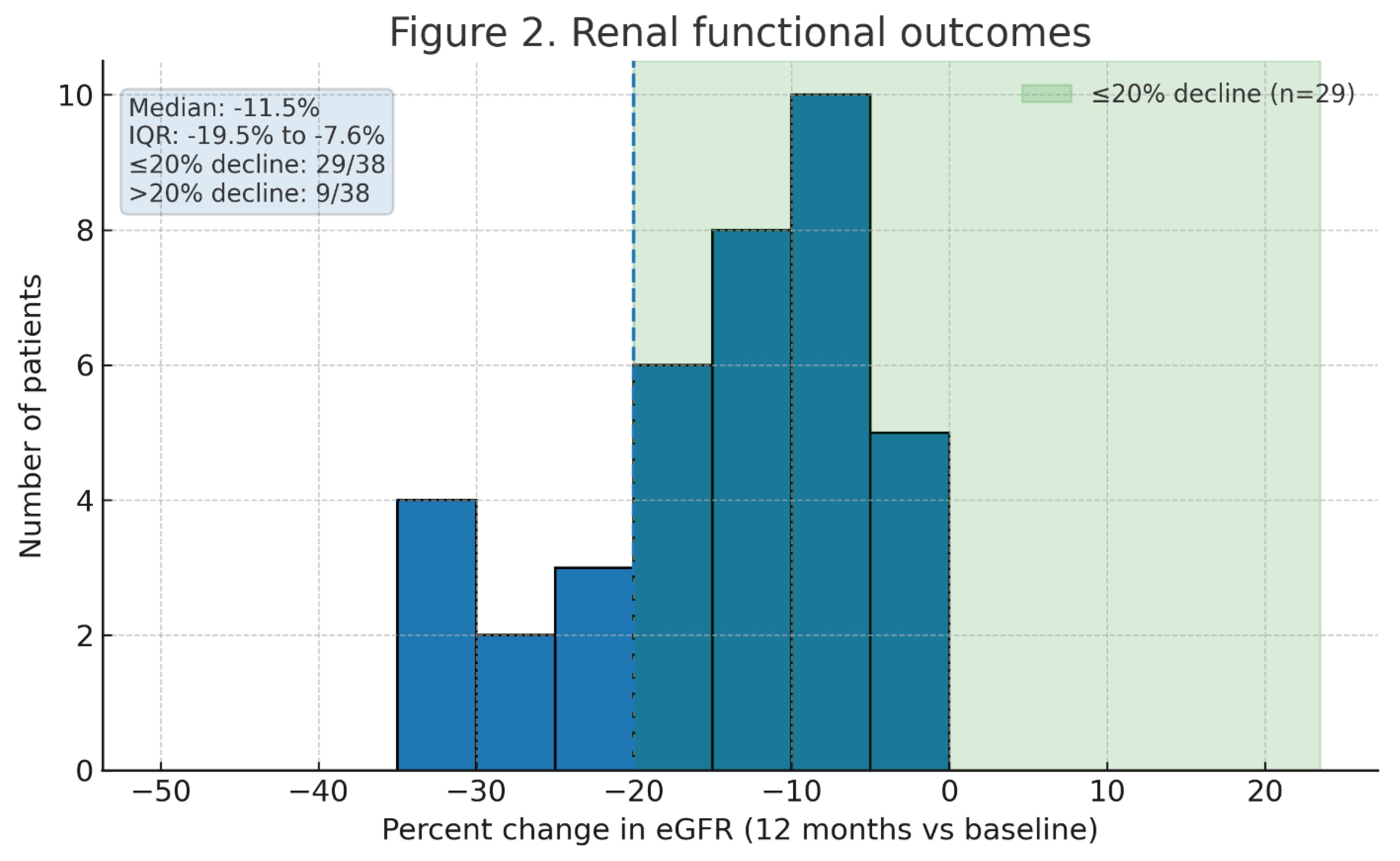

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of percent change in eGFR; 29 patients (76%) had ≤20% decline in eGFR, and 9 patients (24%) experienced >20% decline. Importantly, none of the patients with two kidneys developed de novo Stage 4 CKD (eGFR <30) or required dialysis after PN. Two of the three solitary kidney patients had transient Stage 4 AKI immediately post-op (eGFR nadirs ~25–28) but recovered to eGFR >30 by 3 months; at 1 year, all solitary kidney patients remained dialysis-independent with eGFR ≥35. Overall, 5 patients (13%) had an increase in CKD stage by 12 months (all from Stage 1 to Stage 2 or Stage 2 to Stage 3a). No patient progressed to stage 3b or higher CKD. These outcomes underscore the renal preservation afforded by partial nephrectomy

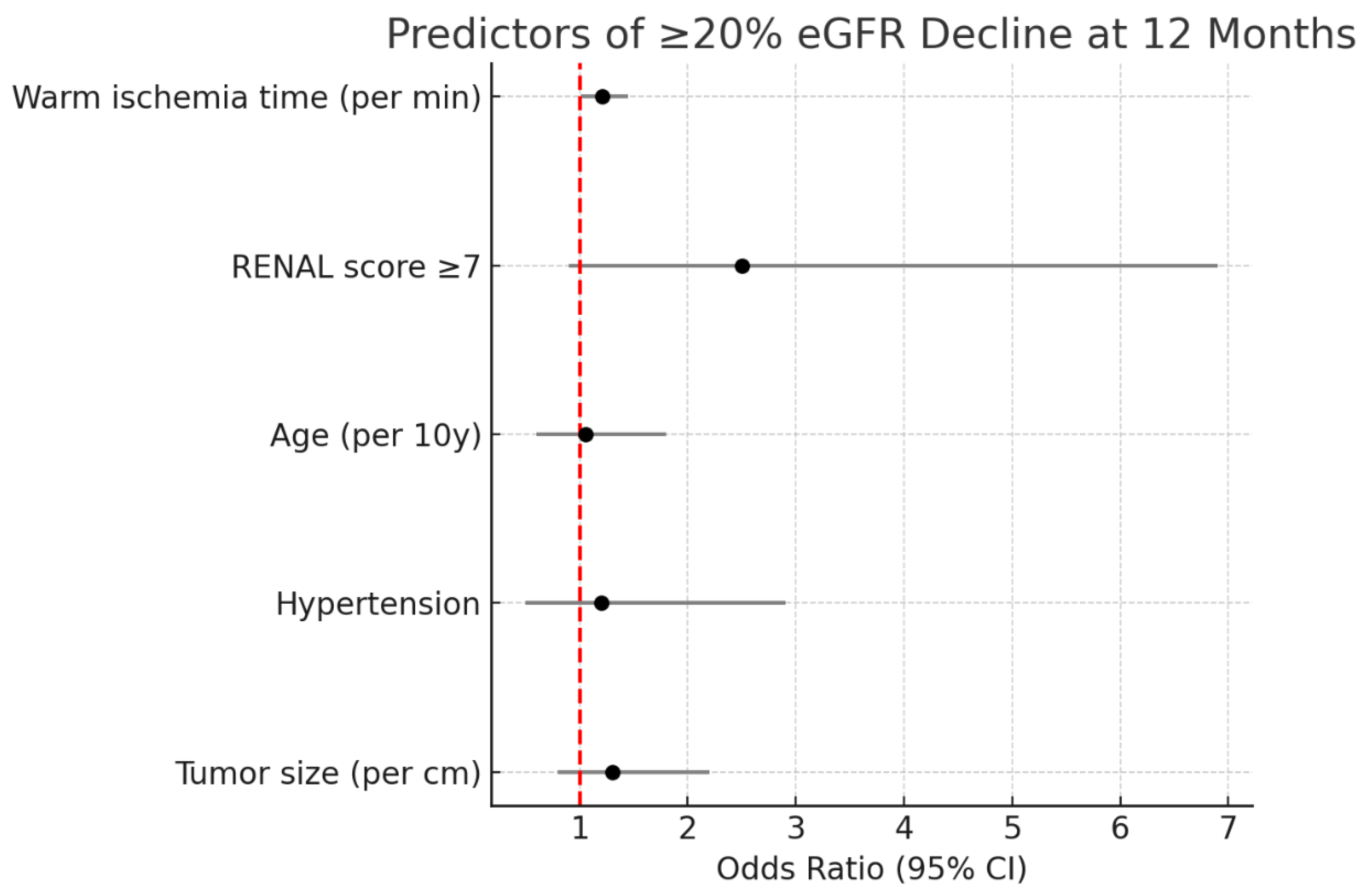

Univariate analysis found that age, hypertension, and baseline eGFR were not significantly associated with >20% eGFR decline (all

p>0.2) as shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 3. The strongest predictors of significant GFR decline were tumor complexity and warm ischemia time. Patients with RENAL score ≥7 (moderate/high complexity) were more likely to have >20% GFR loss than those with low-complexity tumors (31% vs 10%,

p = 0.12). Likewise, those with warm ischemia time >20 minutes had higher odds of >20% GFR drop (40% vs 18%,

p = 0.18). In multivariable logistic regression, warm ischemia time emerged as an independent predictor of ≥20% eGFR decline at 1 year (OR 1.21 per minute, 95% CI 1.01–1.45,

p = 0.04). Each additional minute of warm ischemia was associated with a 21% increase in odds of significant GFR loss, underscoring that even within our generally safe ischemia durations, every minute of hilar clamping may affect functional outcomes. RENAL complexity showed a trend toward significance (OR ~2.5 for moderate/high vs low,

p = 0.08). Other factors, including solitary kidney status, blood loss, and tumor size as a continuous variable, did not reach significance in the multivariable model (likely due to limited sample).

Figure 2 presents a forest plot of the multivariate analysis for predictors of >20% eGFR decline. Notably, zero ischemia (off-clamp cases) and cold ischemia cases all had excellent preservation (median GFR decline ~5%), though numbers were small.

Figure 3 is a Forest plot of multivariable logistic regression for predictors of ≥20% eGFR decline at 12 months. Warm ischemia time was the only independent predictor (

OR 1.21 per minute >20 min, 95% CI 1.01–1.45,

p = 0.04). RENAL score (moderate/high vs low) showed a trend (

OR ~2.5,

p = 0.08). Other covariates (age, comorbidities, tumor size) were not significant.

3.4. Trifecta Achievement

Out of 38 cases, 30 patients (78.9%) achieved the “Trifecta” outcome (negative margin, WIT ≤25 min, and no Clavien ≥II complication). This high trifecta rate indicates that in the majority of patients, the surgery met all three optimal criteria. In 8 patients (21.1%), trifecta was not achieved due to one or more criteria not being met. The breakdown of trifecta failures is as follows: 6 patients had postoperative complications of Clavien grade II (and thus failed the complication-free criterion), 1 patient exceeded 25 minutes of warm ischemia (32 minutes WIT in a complex tumor), and 1 patient had a positive margin. Notably, the single case with WIT >25 min and the positive-margin case were different patients; one of these patients also had a grade II complication, accounting for overlap in failures. No patient failed trifecta on more than one criterion except one (who had both WIT >25 and a complication). If a more stringent definition of trifecta (e.g., WIT ≤20 min and no complications at all) were applied, 77% of our patients would still fulfill it, reflecting generally short ischemia times and low complication rates.

Table 5 compares key outcomes by tumor complexity category and between the two hospitals. Bamenda had a higher trifecta rate (80%) than Nkwen (73%), but the difference was not significant (

p = 0.64), suggesting consistency of outcomes across centers despite differing case volumes (Bamenda contributed 71% of cases). Patients with high RENAL scores had more complications (one of one high complexity cases had a complication) and slightly longer ischemia. Nonetheless, even moderate-to-high complexity tumors had a trifecta rate around two-thirds in our series, demonstrating the feasibility of OPN for selected larger or endophytic tumors in LMIC practice.

3.5. Predictors of Trifecta Non-achievement

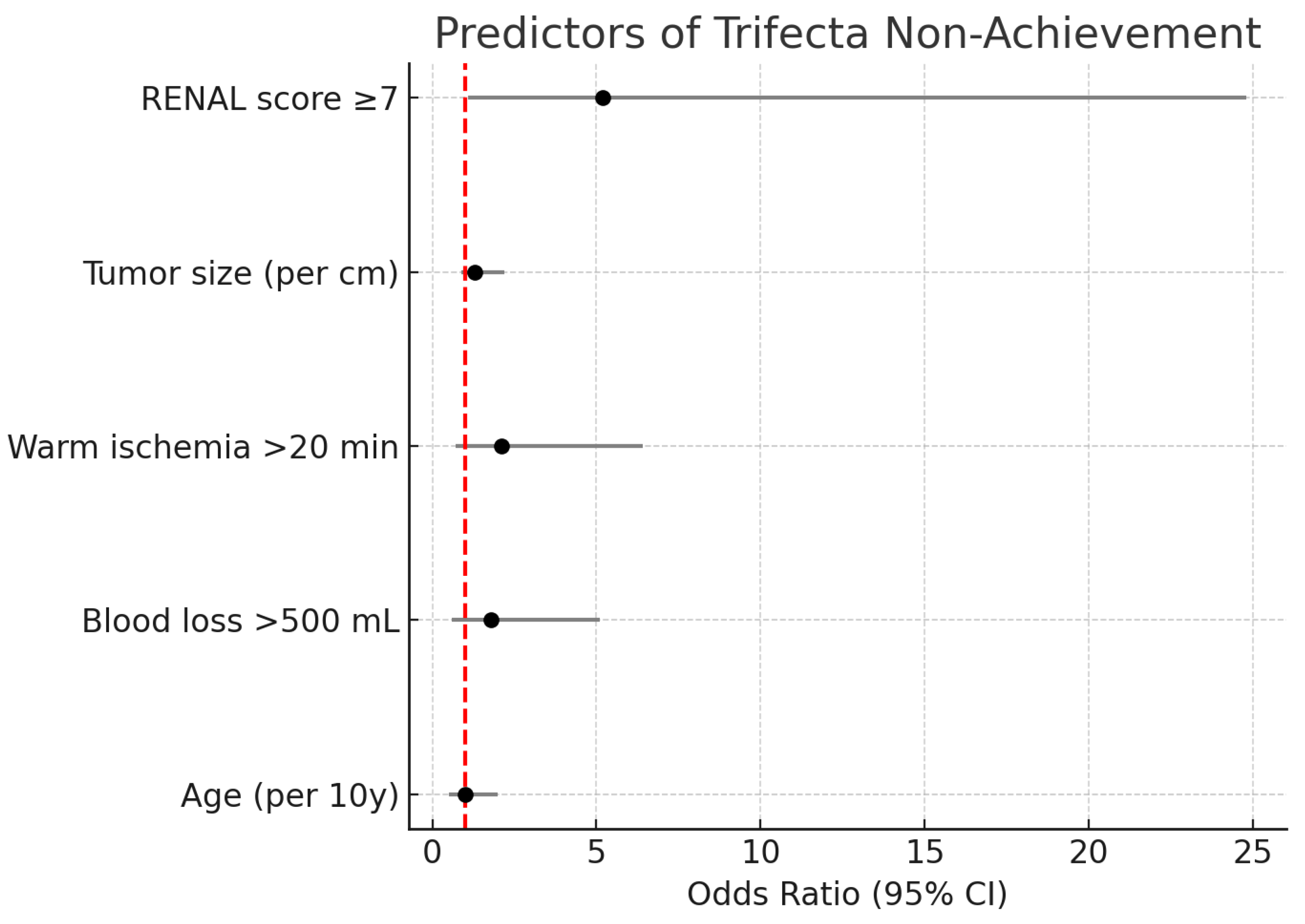

On univariate analysis, larger tumor size and higher RENAL score were associated with lower odds of achieving trifecta (trifecta rate 90% in tumors <4 cm vs 68% in ≥4 cm,

p = 0.10). The presence of significant comorbidities showed no clear effect on trifecta. Interestingly, surgical volume (center) did not significantly influence trifecta rates; both hospitals had similar outcomes despite Bamenda’s higher volume, though our sample is small. In multivariable logistic regression, the only variable significantly predicting failure to achieve trifecta was tumor complexity. Moderate/high complexity tumors had an OR of ~5.2 for trifecta failure compared to low-complexity tumors (95% CI 1.1–24.8,

p = 0.041). This reflects the increased risk of either a longer ischemia or a complication in more complex cases. Warm ischemia time correlated with complexity and was not entered to avoid multicollinearity, but in effect all cases with WIT >25 were high complexity. Blood loss >500 mL showed a trend toward association with trifecta failure (since transfusions count as complications) but did not reach significance when complexity was in the model.

Figure 4 depicts the adjusted ORs for factors associated with not achieving trifecta. Notably, neither patient age nor surgeon (center) significantly affected trifecta attainment, suggesting that with proper technique, OPN outcomes are reproducible.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates that open partial nephrectomy is a feasible and effective surgical option in an LMIC setting, yielding outcomes that align closely with those from high-income countries. Among 38 patients treated with OPN for localized RCC in Cameroon, we achieved excellent cancer control (97% R0 resection rate, 94.7% 2-year recurrence-free survival) and substantial preservation of renal function (median eGFR decline of 12%). The complication profile was acceptable and no perioperative mortality occurred, attesting to the safety of the procedure in experienced hands. These findings are important because nephron-sparing surgery has historically been underutilized in low-resource environments due to concerns about surgical complexity and resource constraints [

1]. Our data support that, with appropriate patient selection and surgical expertise, OPN can be implemented successfully in LMICs, offering patients the well-documented benefits of renal preservation without compromising oncologic outcomes.

4.1. Oncologic Outcomes:

The oncologic efficacy of partial nephrectomy in our cohort was evidenced by the low positive margin rate (2.6%) and high recurrence-free survival. All but one patient had complete tumor resection with negative margins, and only 2 patients (5%) had recurrence at 2 years. Both cases that had recurrence occurred in higher-risk scenarios (a positive-margin case and a high-grade tumor). These outcomes mirror those reported in developed centers. Large series have shown local recurrence rates of 1–5% and 5-year recurrence-free probabilities around 95% after PN for T1 RCC [

2,

3]. Our 2-year RFS of 95% is well within this range, despite a significant proportion (58%) of tumors >4 cm (T1b/T2). This suggests that cancer control was not compromised by performing PN rather than RN, consistent with the principle that PN provides equivalent oncologic outcomes for appropriately selected localized tumors [

2]. It is noteworthy that even our few cT2 tumors were managed successfully with OPN and none have recurred to date. While PN for tumors >7 cm remains somewhat controversial, emerging evidence (including a recent meta-analysis) indicates that partial nephrectomy can be non-inferior to radical nephrectomy in tumor control for selected cT2 tumors, with careful technique and acceptable morbidity [

7,

15]. Our experience, albeit limited for T2, aligns with those findings and underscores the feasibility of nephron-sparing even for larger tumors in LMIC patients who may particularly benefit from maximizing renal function (e.g., due to limited dialysis availability).

4.2. Renal Functional Outcomes:

Partial nephrectomy’s primary advantage is preservation of renal parenchyma, thereby mitigating CKD risk [

8]. In our study, the mean GFR reduction was about 13%, and no patient required dialysis or had progressive CKD beyond stage 3a in follow-up. By contrast, historical cohorts have shown that radical nephrectomy often causes a >30% GFR reduction and can precipitate new-onset stage ≥3 CKD in a substantial fraction of patients [

4,

10,

16]. The importance of nephron-sparing is magnified in settings like Cameroon, where managing advanced CKD is challenging because dialysis slots are scarce and out-of-pocket costs are prohibitive for many. Our results confirm that OPN preserved renal function to a high degree: three-quarters of patients lost less than one-fifth of their kidney function at 1 year, a remarkable outcome considering that even a small loss of GFR can impact long-term health [

10,

19]. Moreover, among patients with pre-existing mild CKD, none progressed to severe CKD. These findings reinforce that PN should be pursued whenever oncologically appropriate, to avoid unnecessary renal insufficiency. They also highlight the success of surgical strategies employed in which nearly all cases had short warm ischemia durations (about18 minutes) and one was done off-clamp with cold perfusion, reflecting careful attention to renal ischemia. It is well-established that limiting warm ischemia to approximately 25 minutes or less helps preserve postoperative GFR [

8]. We adhered to this threshold and documented only one case slightly above it (32 min), which likely contributed to that patient’s greater GFR drop. This underscores the importance of intraoperative discipline with ischemia time; LMIC surgeons performing OPN should have a plan for rapid tumor resection and renorrhaphy, and consider cold ischemia techniques for anticipated longer cases (as we did for the solitary kidney patient) [

8]. Our regression analysis confirmed warm ischemia time as a key modifiable predictor of functional loss as each extra minute beyond 20 min increased odds of significant GFR decline, echoing Thompson et al.’s classic finding that “every minute counts” during hilar clamping [

11]. Interestingly, tumor complexity correlated with GFR loss (via longer WIT and more parenchymal volume resected), suggesting that nephron-sparing of complex tumors may inherently sacrifice more function; however, even in those cases, partial nephrectomy still preserves more renal function than a radical would [

2,

3,

16].

4.3. Perioperative Safety and Trifecta:

One of the concerns about introducing partial nephrectomy in low-resource settings is the potential for higher complication rates, given the technical demands of the surgery. In our series, the overall complication rate was 34%, with all being minor (grades I–II) and

no major complications or mortalities. This is an encouraging outcome, indicating that with proper training and perioperative care, OPN can be performed safely in an LMIC context. Our zero rate of Clavien ≥III complications compares favorably to published rates of 5–10% major complications in large PN series from high-income institutions [

3,

7]. It is possible that our smaller sample and careful patient selection (few very high-complexity tumors) contributed to this low rate. Nonetheless, our finding dispels the notion that open PN is “too risky” outside tertiary centers as we have demonstrated, it can be done with minimal severe morbidity. The most common complications in our cohorts (urinary infections, pneumonias, self-limited ileus) are manageable and did not detract greatly from outcomes. We attribute the good safety profile to meticulous surgical technique, aggressive prevention measures (early mobilization, DVT prophylaxis, etc.), and perhaps the relatively young age of our cohort (median age 56) conferring resilience.

The Trifecta metric provides an integrated assessment of outcome quality. Our trifecta rate of achievement of 79% is high; and is comparable to rates reported in high-volume centers in developed countries. For example, Basatac et al. achieved trifecta in 77% of robotic PN cases by a low-volume surgeon [

12], and Mehra et al. reported trifecta rates of 73% for open PN, 64% for laparoscopic PN, and 61% for robotic PN in an Indian tertiary center [

12]. In our series of primarily open surgeries, the trifecta outcome appears even more favorable, likely reflecting the dominance of relatively low-complexity tumors and meticulous surgical technique. Among our 21 low-complexity tumors (RENAL <7), trifecta was achieved in 19 (90%); a rate consistent with the notion that simpler tumors yield better perioperative outcomes [

7]. By contrast, trifecta was achieved in 11 of 17 (65%) moderate/high complexity cases, still respectable. The difference was driven by higher complication incidence in more complex cases (two-thirds of complications occurred in RENAL ≥7 tumors), in line with other reports [

7]. This implies that when complications are minimized, trifecta goals are very attainable even in LMIC practice. Importantly,

zero trifecta failures in our study were due to oncologic compromise: margin status was negative in 37/38 patients, and the single positive-margin patient was an outlier case. This underscores that cancer control was not sacrificed in pursuit of nephron-sparing. Notably, trifecta failures in our series were mostly due to complications (specifically, six Clavien II events) rather than oncologic or ischemia issues. All margins were negative in trifecta-fail cases except one, and only one case had WIT >25 (and that case did not develop complications). We acknowledge that achieving trifecta is not an end in itself, but it correlates with favorable patient outcomes (cancer control, renal function, and recovery) [

7,

17]. Thus, our high trifecta rate in Cameroon demonstrates that “optimal outcomes” are not limited to wealthy countries or robotic surgery. Indeed, some studies have found no difference in trifecta attainment between open, laparoscopic, and robotic PN, supporting that surgical approach is less important than surgical precision [

3]. Our experience echoes this, demonstrating that open surgery, albeit with slightly longer incision and hospital stay, delivered outcomes on par with the best reports of robotic PN (which often cite 70–80% trifecta in experienced hands) [

12,

13,

14]. This is a pivotal point for LMIC urology: OPN can bridge the gap in settings where advanced technology is lacking, allowing patients to receive state-of-the-art cancer care without waiting for robotic access.

4.4. Comparison to Other LMIC Reports:

There is scant published data on partial nephrectomy outcomes from sub-Saharan Africa. Most regional reports have focused on radical nephrectomy, citing advanced tumor stage and resource limitations as reasons for low utilization of PN [

1]. Our study, to our knowledge, represents one of the first multi-center series of PN from this region. The results should inspire confidence that partial nephrectomy is feasible in LMIC hospitals with properly trained surgeons. Additionally, our data align with reports from other developing contexts, such as South Asia. For example, an analysis from India (JIPMER, Puducherry) likewise showed that OPN and laparoscopic PN achieved similar trifecta rates and that laparoscopic PN can be a cost-effective alternative to robotic in developing countries [

3,

13,

18]. In our setting, pure laparoscopy for PN was not available during the study period, so open surgery was the only option. It is conceivable that, as laparoscopy training improves in LMICs, more partial nephrectomies could be attempted laparoscopically. However, given the steep learning curve and lack of tactile feedback in laparoscopy, open surgery remains crucial for complex cases and for centers early in the nephron-sparing adoption curve [

2,

3,

13]. Our success with OPN provides a benchmark – as laparoscopic or robotic techniques eventually enter the setting, outcomes should at least meet this standard. Furthermore, because open surgery is more forgiving in terms of required equipment and can accommodate larger tumors (including those requiring manual palpation or extensive reconstruction), it will likely continue to play a role in LMICs for years to come. The lack of inferiority of OPN in outcomes should be emphasized to stakeholders and trainees in these regions [

2]. O’Connor et al. noted that international guidelines prioritize renal preservation regardless of surgical approach [

2], reinforcing that the focus should be on oncologic and functional results, not on the novelty of the technique.

4.5. Clinical Implications:

The present study highlights several practical implications. First, patient selection is key. Our median tumor size was 4.5 cm, and few hilar or endophytic masses were present (only one high RENAL case); this undoubtedly contributed to our favorable outcomes. As LMIC centers start PN programs, beginning with smaller, exophytic tumors is prudent to build experience [

3,

7,

13,

20]. As comfort grows, more complex cases can be tackled, potentially with adjuncts (ice cooling, selective clamping) as we employed in one solitary kidney case. Second, surgical planning and intraoperative strategy should prioritize minimizing ischemia and bleeding. We achieved a median WIT of 18 min by adhering to steps like early renal artery control, rapid tumor excision (often within 10–15 min), and efficient renorrhaphy. In one complex case, we leveraged cold ischemia to extend safe clamp time; LMIC surgeons should be aware that simple ice slush can be a powerful tool to protect the kidney when longer resection is needed and fancy equipment is unavailable [

2]. Follow-up imaging allowed early detection of the few recurrences, enabling timely intervention. In LMICs, patient follow-up can be inconsistent, but our high follow-up rate (100% at 1 year) was achieved through diligent patient education and phone reminders, an approach that others can replicate to ensure post-PN surveillance.

4.6. Limitations:

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. The sample size is relatively small, reflecting the early adoption phase of partial nephrectomy in our region. This limits the power to detect predictors of outcomes and might overestimate success rates due to careful selection (a learning curve effect). Our median follow-up duration of 28 months, is sufficient for early oncologic outcomes but longer surveillance is needed to confirm durable cancer control at 5 or 10 years. Additionally, the retrospective design is subject to inherent biases; for instance, patients deemed unsuitable for PN (due to very large tumors or medical unfitness) were not included, which could bias outcomes favorably. We attempted to mitigate this by including all consecutive cases and reporting outcomes transparently. There is also no direct comparator group (e.g., similar patients who underwent radical nephrectomy) in this study. However, robust historical data exist regarding the deleterious impact of nephrectomy on CKD and survival [

4,

10], so we felt ethical equipoise was not present to withhold PN in appropriate candidates.

5. Conclusion

Open partial nephrectomy is feasible and effective for management of localized renal tumors in low- and middle-income countries. In this two-center Cameroonian cohort, OPN achieved high rates of complete tumor resection with negative margins and excellent short-term cancer control (95% 2-year RFS), while preserving renal function in the majority of patients (mean GFR decline 13%, with no patient requiring dialysis). The perioperative outcomes were favorable, with zero major complications and a trifecta achievement rate of ~79%, comparable to outcomes reported in high-volume international centers. Tumor complexity was the main factor influencing outcomes, but even moderate-complexity tumors were often managed successfully. These findings underscore that, with adequate surgical expertise, open nephron-sparing surgery can be safely implemented in resource-limited settings, providing patients the dual benefit of oncologic cure and renal preservation. Wider adoption of partial nephrectomy in LMICs could substantially reduce the burden of CKD and improve long-term survival for patients with kidney tumors, aligning with global standards of care. Efforts to train surgeons in nephron-sparing techniques and to prioritize partial nephrectomy in guidelines and practice in LMICs are warranted. In conclusion, open partial nephrectomy offers a viable, cost-effective solution for treating localized RCC in LMICs, achieving outcomes on par with more technologically intensive approaches and thus bridging the gap in global cancer care.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, The database used in this study is part of an ongoing research project and is therefore not publicly available at this time. However, it can be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author for academic and scientific purposes.

Author Contributions

(CRediT) Dr. Tagang Titus Ngwa-Ebogo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Original Draft. Mbouch Orole Landry: Methodology, Formal Analysis, Review and Editing. Dr. Azemafac Kereen Esewoh: Visualization, Writing – Review & Editing Dr. Manka’a Marie Louise: Reviewing Pr. Gloria Ashutantang Enow: Review & Editing Pr. Fru Forbuzshi Angwafo III: Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing

Funding

This study received no external funding. All activities were conducted using institutional resources and volunteer support.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the Directors and Administrators of Baptist Hospital Nkwen and Regional Hospital Bamenda for administrative authorization and institutional support. We also acknowledge the invaluable assistance of the physiotherapy units and clinical staff at both institutions for their contribution to patient care and data collection.

Consent to Participate

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, and the fact that only patients’ files were studies, patient consent was not necessary

Ethical Approval and/or Institutional Review Board (IRB) Approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Cameroon Baptist Convention Health Board Institutional Review Board (Ref: IRB2024-09 dated February 22, 2024). Administrative authorization was obtained from Baptist Hospital Nkwen and Regional Hospital Bamenda.

Conflict of Interest:

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this study.

Presentation(s) or Awards at a Meeting:

This work has not been presented at any scientific meeting or received any awards at the time of manuscript submission.

Consent to Publish Declaration:

All authors consent to the publication of this work. No patient identifiers are included in the manuscript.

References

- Cassell, A.; Jalloh, M.; Yunusa, B.; et al. Management of Renal Cell Carcinoma – Current Practice in Sub-Saharan Africa. J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2019, 6, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, E.; Timm, B.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Ischia, J. Open partial nephrectomy: Current review. Transl Androl Urol. 2020, 9, 3149–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehra, K.; Manikandan, R.; Dorairajan, L.N.; et al. Trifecta outcomes in open, laparoscopy or robotic partial nephrectomy: Does the surgical approach matter? J Kidney Cancer VHL. 2019, 6, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.C.; Elkin, E.B.; Levey, A.S.; Jang, T.L.; Russo, P. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy in patients with small renal tumors – is there a difference in mortality and cardiovascular outcomes? J Urol. 2009, 181, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sankin, A.; Sfakianos, J.P.; Schiff, J.; Sjoberg, D.; Coleman, J.A. Assessing renal function after partial nephrectomy using renal nuclear scintigraphy and estimated glomerular filtration rate. Urology. 2012 Aug;80, 343–346. [CrossRef]

- Inker, L.A.; Eneanya, N.D.; Coresh, J.; et al. New creatinine- and cystatin C–based equations to estimate GFR without race. N Engl J Med. 2021, 385, 1737–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitra, A.; Evangeline, S.M.; George, A.J.P.; et al. Comparison of trifecta outcomes for laparoscopic partial nephrectomy between simple and complex renal masses. Afr J Urol. 2025, 31, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, R. Limit warm ischemia to 25 min during partial nephrectomy. Nat Rev Urol. 2021, 7, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.R.; Ou, Y.C.; Huang, L.H.; Lu, C.H.; Weng, W.C.; Yang, C.K.; Hsu, C.Y.; Lin, Y.S.; Chang, Y.K.; Tung, M.C. Robotic partial nephrectomy for renal tumor: The pentafecta outcomes of a single surgeon experience. Asian J Surg. 2023, 46, 3587–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Partial nephrectomy associated with lower rates of chronic kidney disease stage progression. Mayo Clin; 2022 Dec 13 [cited 2025 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/urology/news/partial-nephrectomy-associated-with-lower-rates-of-chronic-kidney-disease-stage-progression/mac-20541248.

- Thompson, R.H.; Lane, B.R.; Gill, I.S.; et al. Every minute counts when the renal hilum is clamped during partial nephrectomy. Eur Urol. 2010, 58, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basatac, C.; Akpinar, H. ‘Trifecta’ outcomes of robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: Results of the ‘low-volume’ surgeon. Int Braz J Urol. 2020, 46, 943–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, A.J.; Cai, J.; Simmons, M.N.; Gill, I.S. “Trifecta” in partial nephrectomy. J Urol. 2013, 189, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garisto, J.D.; Bertolo, R.; Dagenais, J.; et al. Robotic versus open partial nephrectomy for highly complex renal masses: Comparison of perioperative, functional, and oncological outcomes. Urol Oncol. 2018, 36, 471.e1–471.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Poppel, H.; Da Pozzo, L.; Albrecht, W.; et al. A prospective, randomized EORTC intergroup phase 3 study comparing the oncologic outcome of elective nephron-sparing surgery and radical nephrectomy for low-stage renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011, 59, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potretzke, A.M.; Knight, B.A.; Lendvay, T.S.; et al. Progression of chronic kidney disease following radical and partial nephrectomy. Urology. 2022, 169, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffi, N.M.; Larcher, A.; Capitanio, U.; et al. Minimally invasive partial nephrectomy: A contemporary analysis of perioperative outcomes and complications in 2000 patients. Eur Urol. 2020, 77, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Oh, J.J.; Lee, S.; et al. Comparison of robotic and open partial nephrectomy for complex renal tumors (RENAL score ≥10). PLoS ONE. 2019, 14, e0210413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, H.D.; Ball, M.W.; Cohen, J.E.; et al. Trends in renal functional outcomes following surgical management of renal tumors. Urol Oncol. 2015, 33, 425.e1–425.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayn, M.H.; Schwaab, T.; Underwood, W.; Kim, H.L. RENAL nephrometry score predicts surgical outcomes of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. BJU Int. 2011, 108, 876–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).