Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

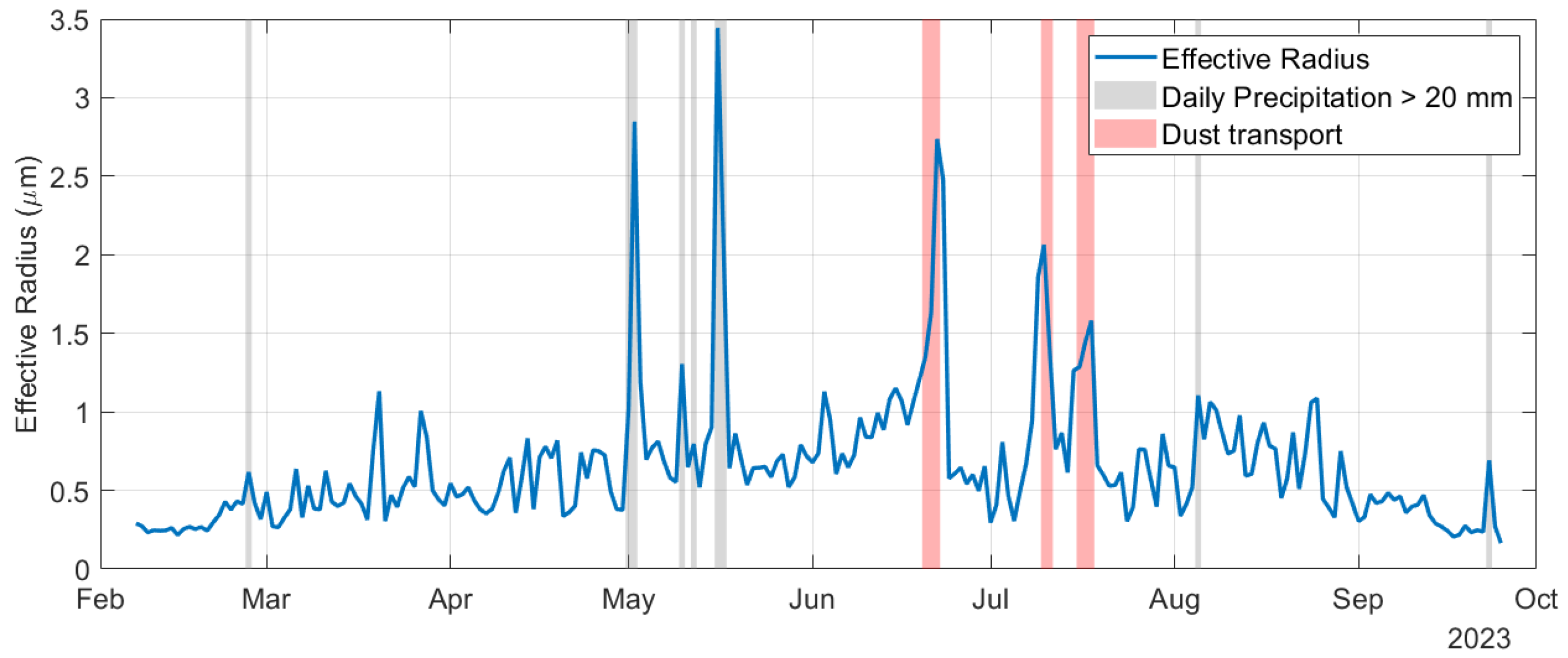

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

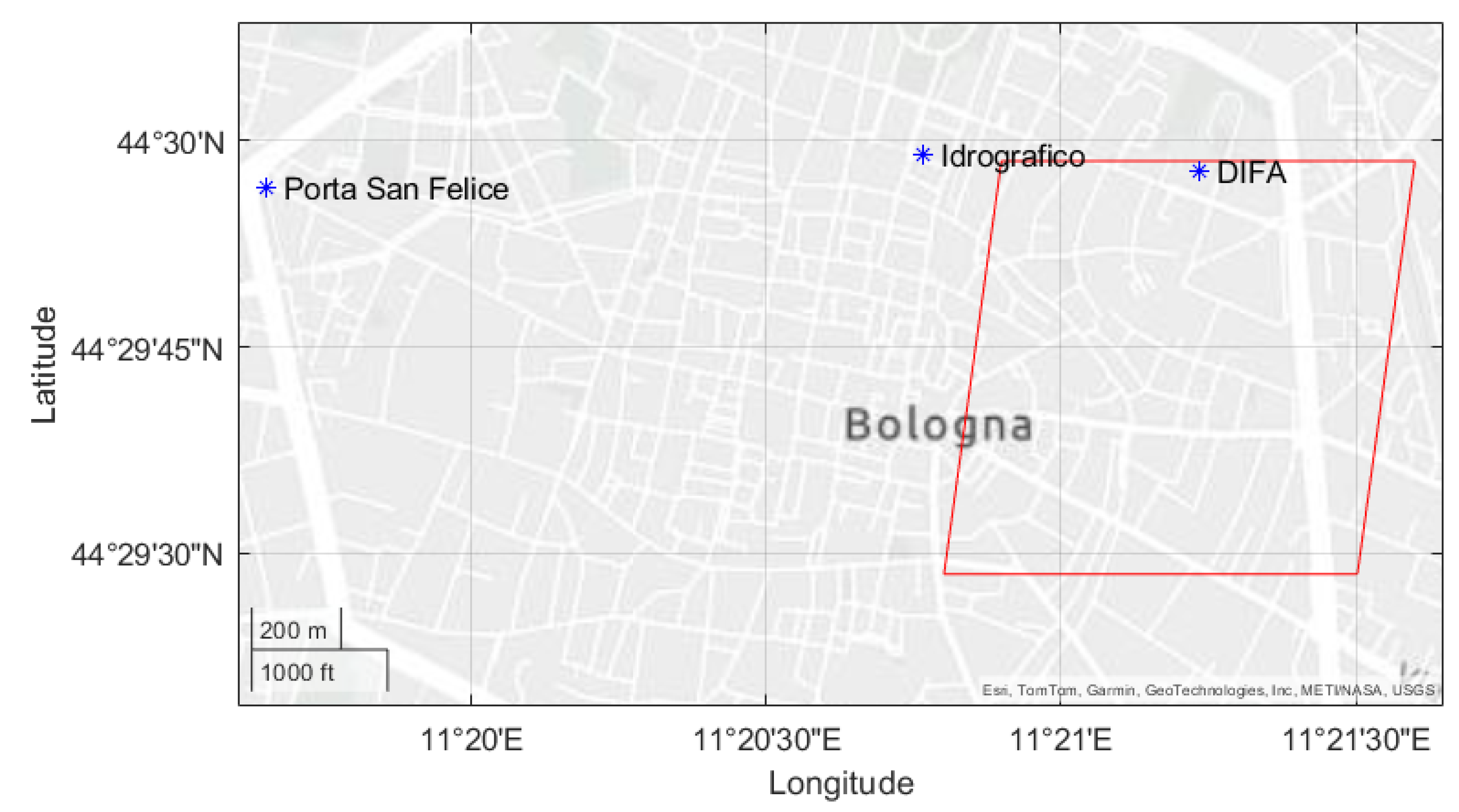

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methodology

2.3. OPC Data

- the Number Ratio (NR) of each particle type in each size bin,

- the average single particle Extinction Efficiency of each particle type in each size bin

- “salt” LOAC type related to “Soluble” OPAC type (here considered at RH = 50%),

- “mineral” LOAC type related to “Insoluble” OPAC type,

- “carbon” LOAC type related to “Soot” OPAC type,

2.4. AOD

2.5. Auxiliary Variables

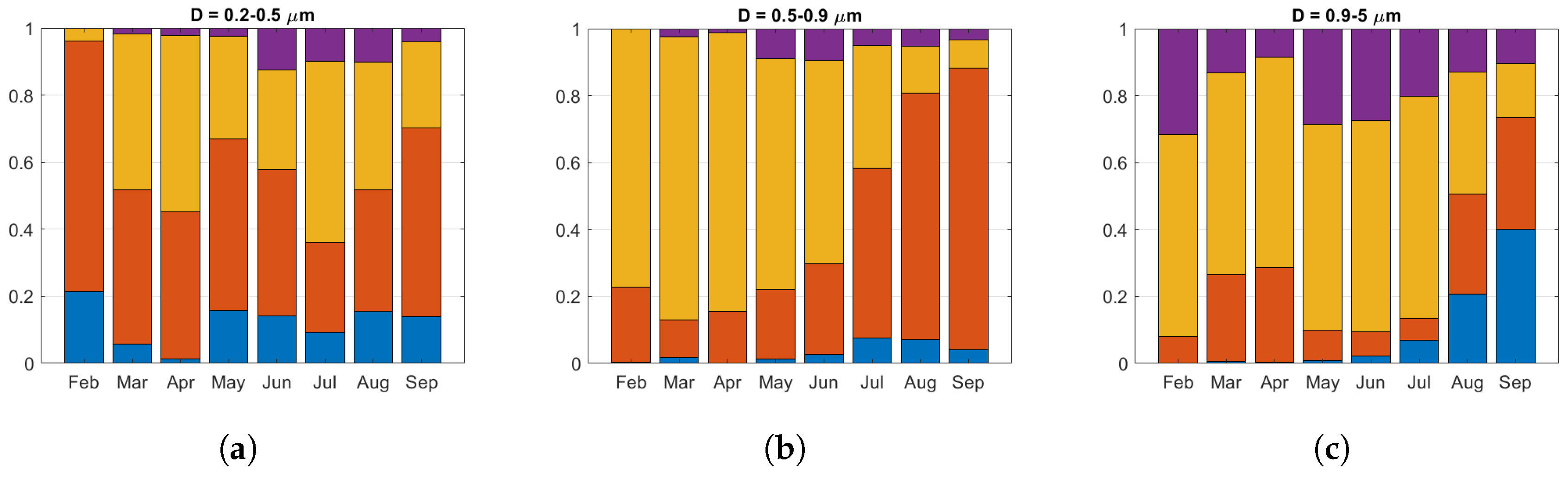

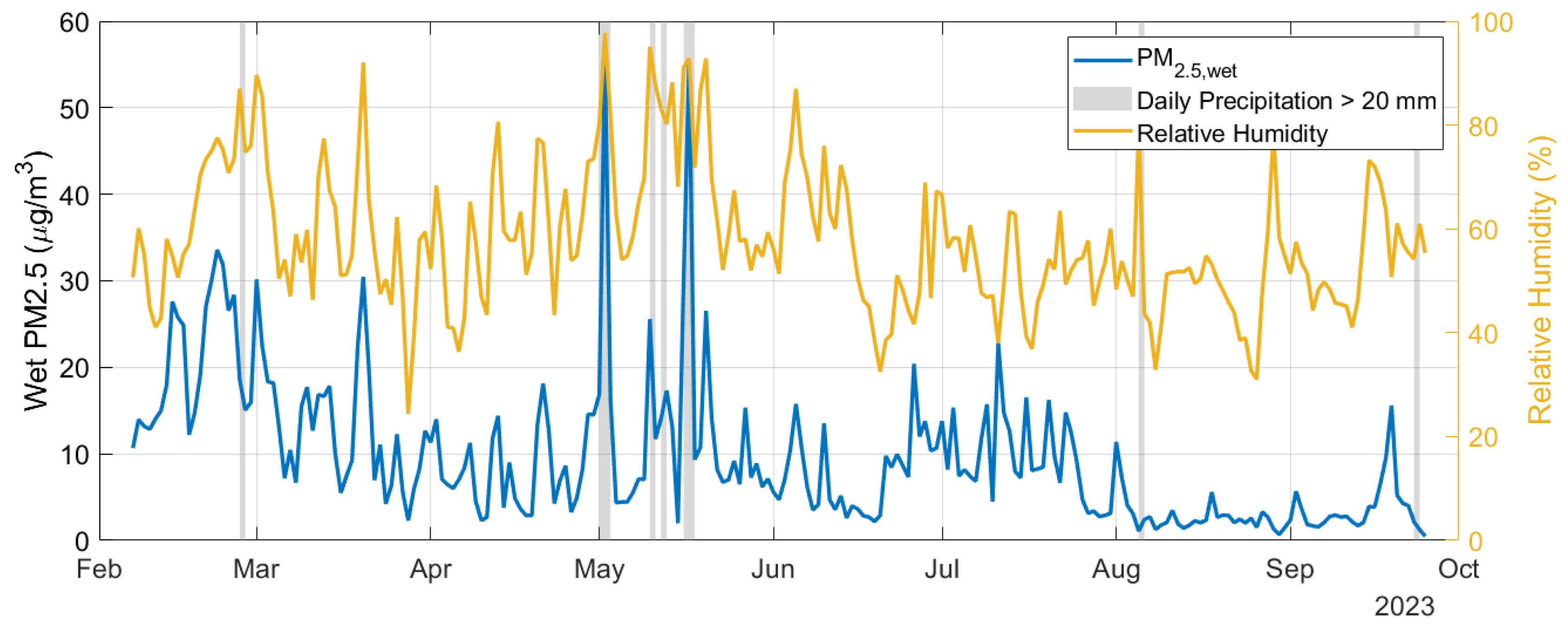

3. Results

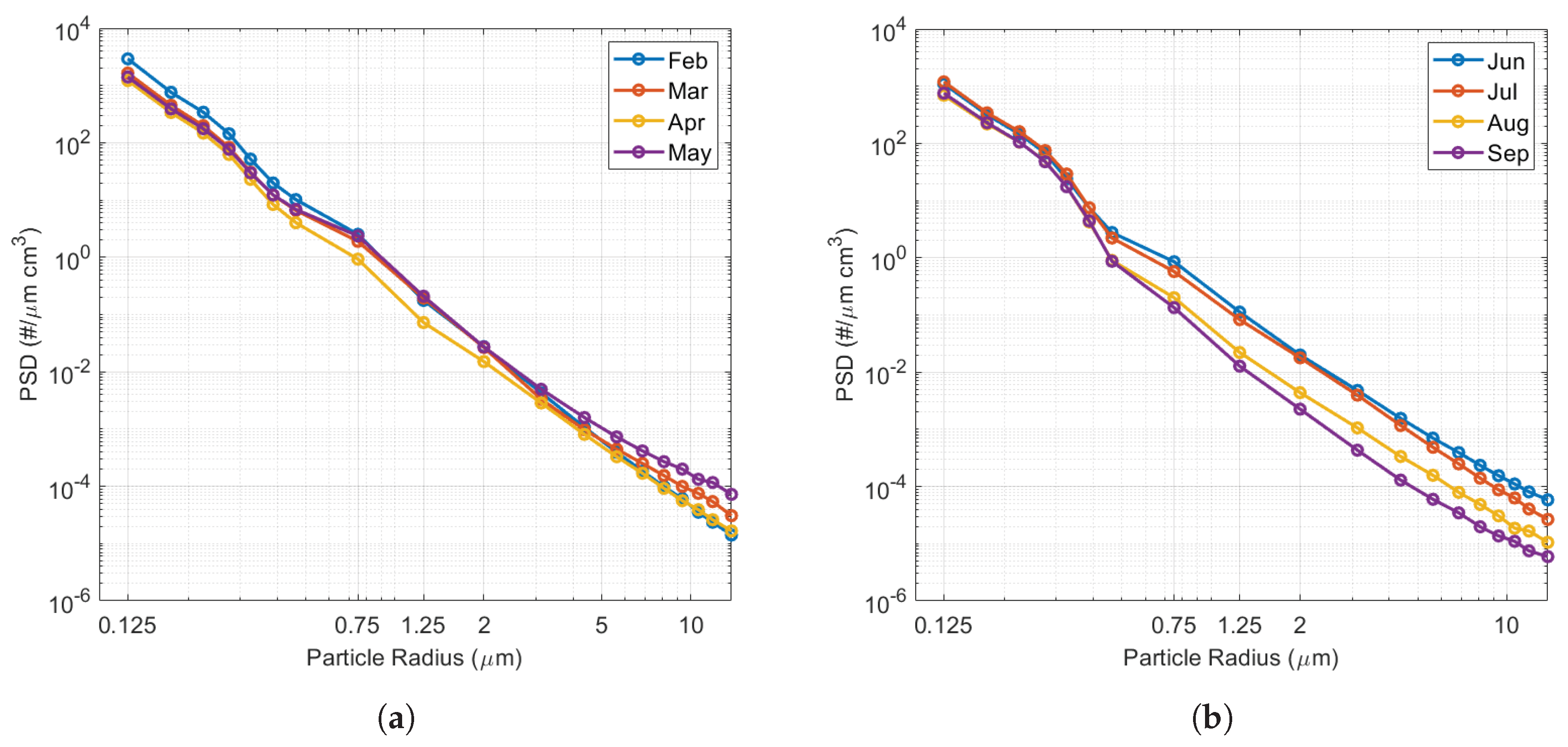

3.1. Analysis of the Particle Concentration Variability

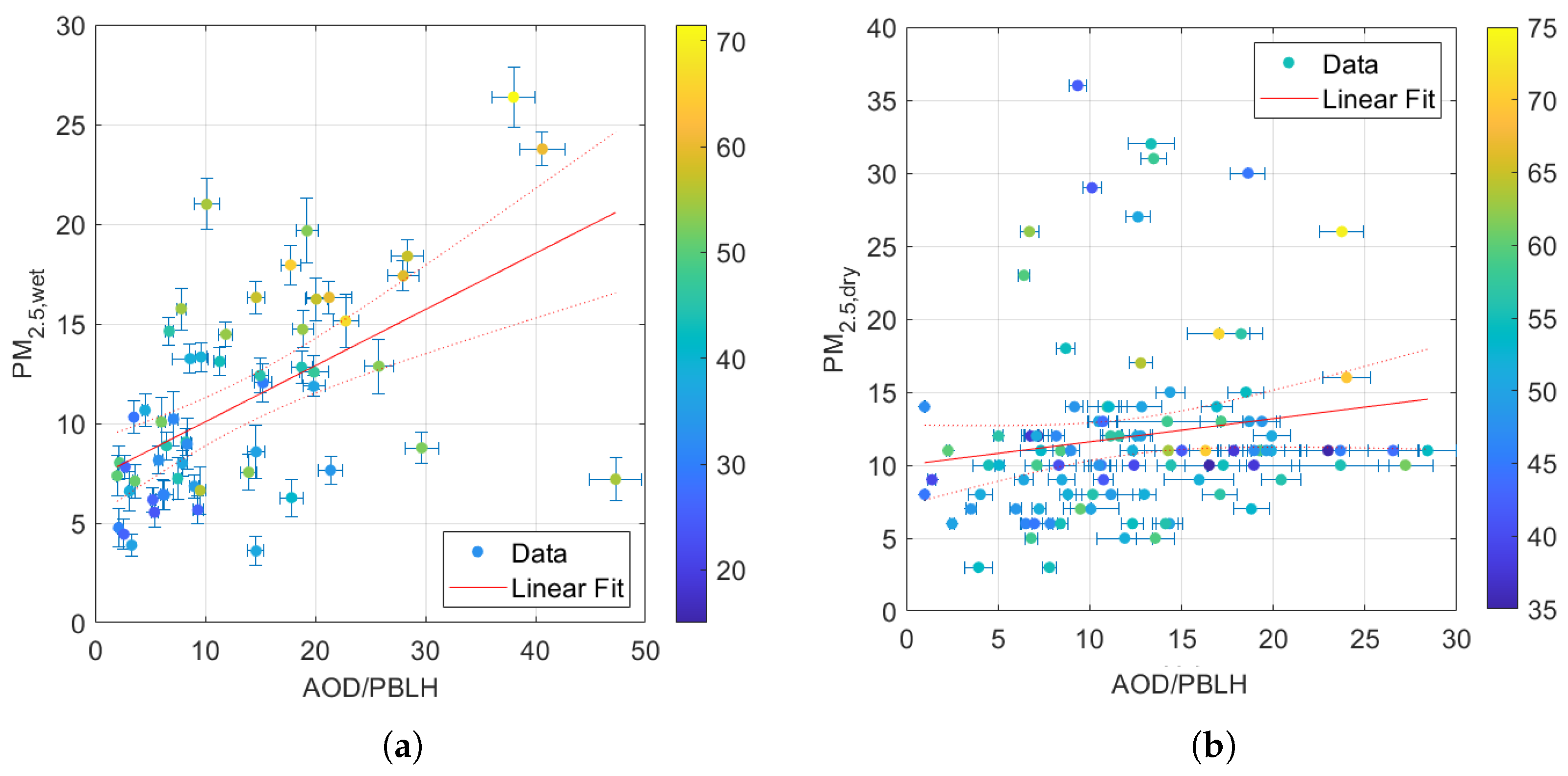

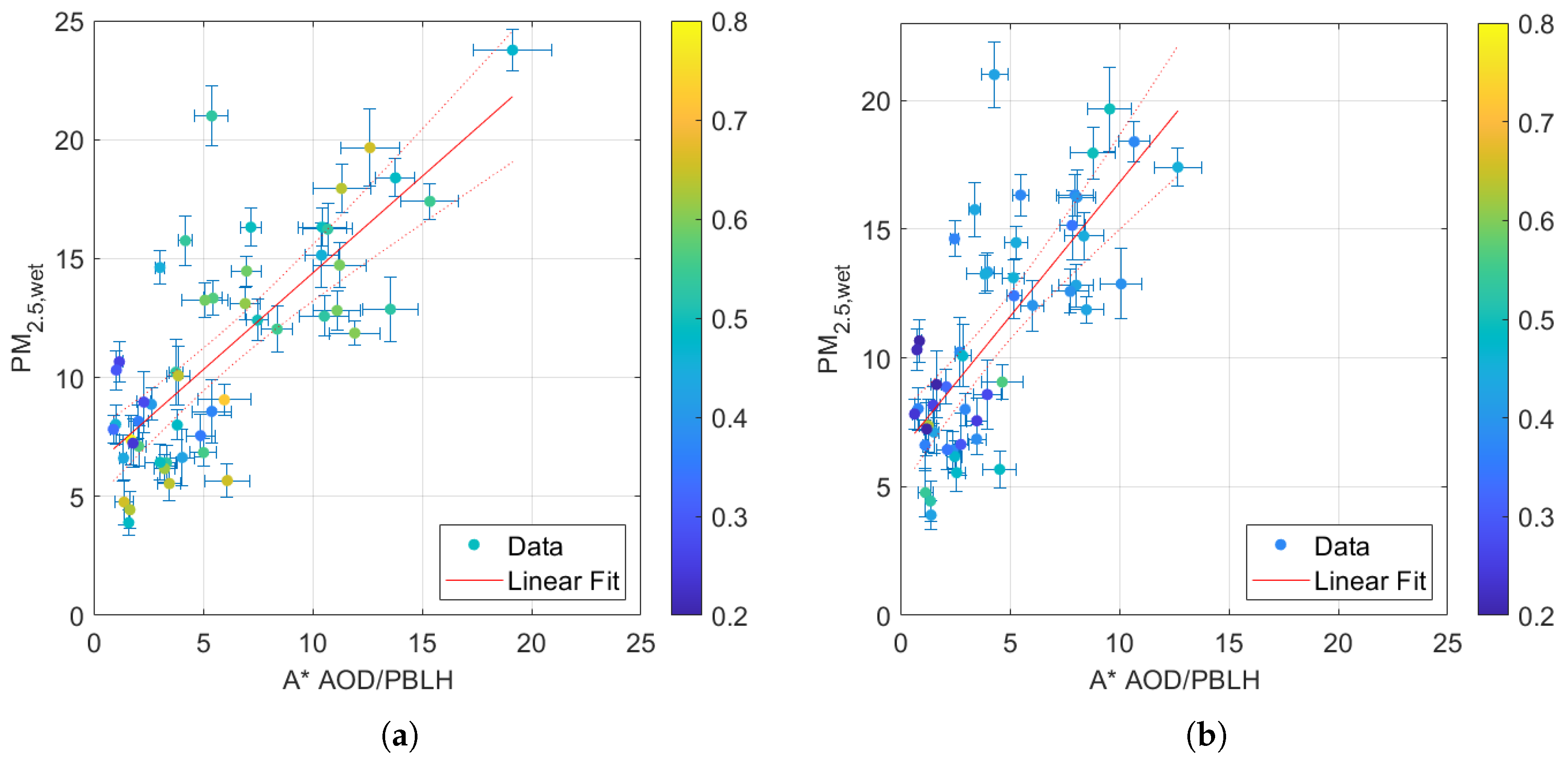

3.2. Methodology Application

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sharma, S.; Chandra, M.; Kota, S.H. Health effects associated with PM2.5: A systematic review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2020, 6, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangavel, P.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.C. Recent insights into particulate matter (PM2.5)-mediated toxicity in humans: An overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. World health statistics 2013; World Health Organization, 2013.

- Martin, R.V.; Brauer, M.; van Donkelaar, A.; Shaddick, G.; Narain, U.; Dey, S. No one knows which city has the highest concentration of fine particulate matter. Atmospheric Environment: X 2019, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, R.M.; Christopher, S.A. Remote Sensing of Particulate Pollution from Space: Have We Reached the Promised Land? Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 2009, 59, 645–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Christopher, S.A. Intercomparison between satellite-derived aerosol optical thickness and PM2.5 mass: Implications for air quality studies. Geophysical Research Letters 2003, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelemeijer, R.; Homan, C.; Matthijsen, J. Comparison of spatial and temporal variations of aerosol optical thickness and particulate matter over Europe. Atmospheric Environment 2006, 40, 5304–5315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Dey, S.; Christopher, S.; Liu, R.; Bi, J.; Balyan, P.; Liu, Y. A review of statistical methods used for developing large-scale and long-term PM2.5 models from satellite data. Remote Sensing of Environment 2022, 269, 112827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yuan, S.; Fan, S.; Song, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Y. Satellite remote sensing for estimating PM2.5 and its components. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2021, 7, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, L.; Riccio, A.; Ferrini, B.; D’Angelo, L.; Rovelli, G.; Casati, M.; Angelini, F.; Barnaba, F.; Gobbi, G.; Cataldi, M.; et al. Satellite AOD conversion into ground PM10, PM2.5 and PM1 over the Po valley (Milan, Italy) exploiting information on aerosol vertical profiles, chemistry, hygroscopicity and meteorology. Atmospheric Pollution Research 2019, 10, 1895–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive - EU - 2024/2881 - EN - EUR-LEX. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L_202402881. Accessed: 2025-08-07.

- Di Antonio, L.; Di Biagio, C.; Foret, G.; Formenti, P.; Siour, G.; Doussin, J.F.; Beekmann, M. Aerosol optical depth climatology from the high-resolution MAIAC product over Europe: differences between major European cities and their surrounding environments. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2023, 23, 12455–12475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nicolantonio, W.; Cacciari, A.; Tomasi, C. Particulate Matter at Surface: Northern Italy Monitoring Based on Satellite Remote Sensing, Meteorological Fields, and in-situ Samplings. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2009, 2, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvani, B.; Pierce, R.B.; Lyapustin, A.I.; Wang, Y.; Ghermandi, G.; Teggi, S. Seasonal monitoring and estimation of regional aerosol distribution over Po valley, northern Italy, using a high-resolution MAIAC product. Atmospheric Environment 2016, 141, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stafoggia, M.; Schwartz, J.; Badaloni, C.; Bellander, T.; Alessandrini, E.; Cattani, G.; de’ Donato, F.; Gaeta, A.; Leone, G.; Lyapustin, A.; et al. Estimation of daily PM10 concentrations in Italy (2006–2012) using finely resolved satellite data, land use variables and meteorology. Environment International 2017, 99, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyapustin, A.; Wang, Y.; Korkin, S.; Huang, D. MODIS Collection 6 MAIAC algorithm. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2018, 11, 5741–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieger, P.; Fierz-Schmidhauser, R.; Weingartner, E.; Baltensperger, U. Effects of relative humidity on aerosol light scattering: results from different European sites. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2013, 13, 10609–10631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänel, G. An attempt to interpret the humidity dependencies of the aerosol extinction and scattering coefficients. Atmospheric Environment (1967) 1981, 15, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagulian, F.; Barbiere, M.; Kotsev, A.; Spinelle, L.; Gerboles, M.; Lagler, F.; Redon, N.; Crunaire, S.; Borowiak, A. Review of the Performance of Low-Cost Sensors for Air Quality Monitoring. Atmosphere 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, J.B.; Dulac, F.; Berthet, G.; Lurton, T.; Vignelles, D.; Jégou, F.; Tonnelier, T.; Jeannot, M.; Couté, B.; Akiki, R.; et al. LOAC: a small aerosol optical counter/sizer for ground-based and balloon measurements of the size distribution and nature of atmospheric particles – Part 1: Principle of measurements and instrument evaluation. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2016, 9, 1721–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, C.; Decesari, S.; Mircea, M.; Giulianelli, L.; Finessi, E.; Rinaldi, M.; Fuzzi, S.; Marinoni, A.; Duchi, R.; Perrino, C.; et al. Size-resolved aerosol chemical composition over the Italian Peninsula during typical summer and winter conditions. Atmospheric Environment 2010, 44, 5269–5278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, L.; Riccio, A.; Perrone, M.; Sangiorgi, G.; Ferrini, B.; Bolzacchini, E. Mixing height determination by tethered balloon-based particle soundings and modeling simulations. Atmospheric Research 2011, 102, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnaba, F.; Putaud, J.P.; Gruening, C.; dell’Acqua, A.; Dos Santos, S. Annual cycle in co-located in situ, total-column, and height-resolved aerosol observations in the Po Valley (Italy): Implications for ground-level particulate matter mass concentration estimation from remote sensing. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2010, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardelli, I.; Bacco, D.; Rinaldi, M.; Bonafè, G.; Scotto, F.; Trentini, A.; Bertacci, G.; Ugolini, P.; Zigola, C.; Rovere, F.; et al. A three-year investigation of daily PM2.5 main chemical components in four sites: the routine measurement program of the Supersito Project (Po Valley, Italy). Atmospheric Environment 2017, 152, 418–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotto, F.; Bacco, D.; Lasagni, S.; Trentini, A.; Poluzzi, V.; Vecchi, R. A multi-year source apportionment of PM2.5 at multiple sites in the southern Po Valley (Italy). Atmospheric Pollution Research 2021, 12, 101192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tositti, L.; Brattich, E.; Masiol, M.; Baldacci, D.; Ceccato, D.; Parmeggiani, S.; Stracquadanio, M.; Zappoli, S. Source apportionment of particulate matter in a large city of southeastern Po Valley (Bologna, Italy). Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2013, 21, 872–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Christopher, S.A.; Wang, J.; Gehrig, R.; Lee, Y.; Kumar, N. Satellite remote sensing of particulate matter and air quality assessment over global cities. Atmospheric Environment 2006, 40, 5880–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilley, L.R.; Shaw, M.; Pound, R.; Kramer, L.J.; Price, R.; Young, S.; Lewis, A.C.; Pope, F.D. Evaluation of a low-cost optical particle counter (Alphasense OPC-N2) for ambient air monitoring. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2018, 11, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattich, E.; Bracci, A.; Zappi, A.; Morozzi, P.; Di Sabatino, S.; Porcù, F.; Di Nicola, F.; Tositti, L. How to Get the Best from Low-Cost Particulate Matter Sensors: Guidelines and Practical Recommendations. Sensors 2020, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Shah, S.; Jiang, W. On-line outlier detection and data cleaning. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2004, 28, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, J.B.; Thaury, C.; Mineau, J.L.; Gaubicher, B. Small-angle light scattering by airborne particulates: Environnement S.A. continuous particulate monitor. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 085901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M.; Koepke, P.; Schult, I. Optical Properties of Aerosols and Clouds: The Software Package OPAC. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 1998, 79, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.; Fang, H.; Wang, L.; Wei, J.; Zhang, M.; Su, X.; Bilal, M.; Liang, X. MODIS high-resolution MAIAC aerosol product: Global validation and analysis. Atmospheric Environment 2021, 264, 118684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozovsky, I.; Ohneiser, K.; Lyapustin, A.; Ansmann, A.; Chudnovsky, A. The impact of different aerosol layering conditions on the high-resolution MODIS/MAIAC AOD retrieval bias: The uncertainty analysis. Atmospheric Environment 2023, 309, 119930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Münkel, C.; Eresmaa, N.; Räsänen, J.; Karppinen, A. Retrieval of mixing height and dust concentration with lidar ceilometer. Boundary Layer Meteorol. 2007, 124, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haman, C.L.; Lefer, B.; Morris, G.A. Seasonal Variability in the Diurnal Evolution of the Boundary Layer in a Near-Coastal Urban Environment. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology 2012, 29, 697–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arpae Emilia-Romagna. https://www.arpae.it/it. Accessed: 2025-06-30.

- Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET). https://aeronet.gsfc.nasa.gov/new_web/index.html. Accessed: 2025-06-30.

- Holben, B.; Eck, T.; Slutsker, I.; Tanré, D.; Buis, J.; Setzer, A.; Vermote, E.; Reagan, J.; Kaufman, Y.; Nakajima, T.; et al. AERONET—A Federated Instrument Network and Data Archive for Aerosol Characterization. Remote Sensing of Environment 1998, 66, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzola, M.; Lanconelli, C.; Lupi, A.; Busetto, M.; Vitale, V.; Tomasi, C. Columnar aerosol optical properties in the Po Valley, Italy, from MFRSR data. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2010, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Tao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Su, L. Satellite-based estimation of regional particulate matter (PM) in Beijing using vertical-and-RH correcting method. Remote Sensing of Environment 2010, 114, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Size bin | Bin Edges () | Bin Diameter () |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 | ||

| 6 | ||

| 7 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 9 | ||

| 10 | 4 | |

| 11 | ||

| 12 | ||

| 13 | ||

| 14 | ||

| 15 | ||

| 16 | ||

| 17 | ||

| 18 | ||

| 19 |

| Size class | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D () |

| X | Definition | R | RMSE () | error | error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | 0.5587 | 0.312 | 4.28 | 0.282 + 40% | 7.26 + 26% | |

| 0.7610 | 0.579 | 3.11 | 0.812 ± 24% | 6.27 ± 23% | ||

| 0.7337 | 0.538 | 3.03 | 1.042± 27% | 6.38±23% | ||

| 0.6997 | 0.490 | 3.18 | 0.431 ± 30% | 6.63 ± 24% | ||

| 0.7196 | 0.518 | 3.09 | 0.587 ± 28% | 6.54±23% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).