1. Introduction

1.1. Personalization in Clinical Medicine and Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence in clinical medicine (Clinical AI) has grown rapidly in the past decade, yet both AI and medicine have developed in parallel since the mid-20th century. Both fields have shifted gradually from top-down to bottom-up reasoning, increasing the capacity to model individual variation.

In medicine, treatments were historically based on expert consensus about population averages (Djulbegovic 2017). The adoption of evidence-based medicine (EBM) in the early 1990s led to reproducible standards rooted in group trials (Guyatt 1992). However, EBM often overlooks individual variability within groups (Nikles 2015). Precision “n-of-1” medicine now focuses on heterogeneous treatment effects and individual outcomes (Troqe 2024).

Artificial Intelligence has followed a parallel trajectory. Early rule-based expert systems encoded rigid human heuristics (Buchanan 1984). Machine Learning (ML) in the 1990s enabled data-driven pattern learning, but models often generalized without individual context (Ezugwu 2024). Deep learning models now allow AI to adapt to complex, multimodal inputs for individualized inference (Ullah 2024). Modern AI increasingly emphasizes personalization, akin to precision medicine.

1.2. The AI Socratic Paradox

This convergence is a double-edged sword. While medicine and AI appear aligned, their integration reveals a tension surrounding epistemic humility. Historically, as medical knowledge grows, so does awareness of its limits (Ahmed 2024). In contrast, AI advances often amplify confidence, providing less room for epistemic humility. This tension becomes salient in the context of personalized medicine (Katz 2025).

At its core, personalized medicine asks clinicians to judge when to follow established precedent and when a patient’s unique features warrant deviation. Clinical AI aims to automate this reasoning, adapting to heterogeneous patient profiles (Desai 2024). Yet as clinical AI becomes the new precedent at scale, a regress arises: for true personalization, an AI must not only make predictions but also know when to deviate from its own recommendations. This demands a form of metacognitive self-awareness; a technical analogue to Socratic wisdom: “I know that I know nothing.” We term this the AI Socratic Paradox.

Importantly, the AI Socratic Paradox is not merely a philosophical abstraction; it manifests across each stage of AI system development, revealing epistemic vulnerabilities with concrete ramifications for reliability, safety, and personalization. It thus offers a conceptual framework for analyzing, critiquing, and advancing the design and evaluation of AI in medicine.

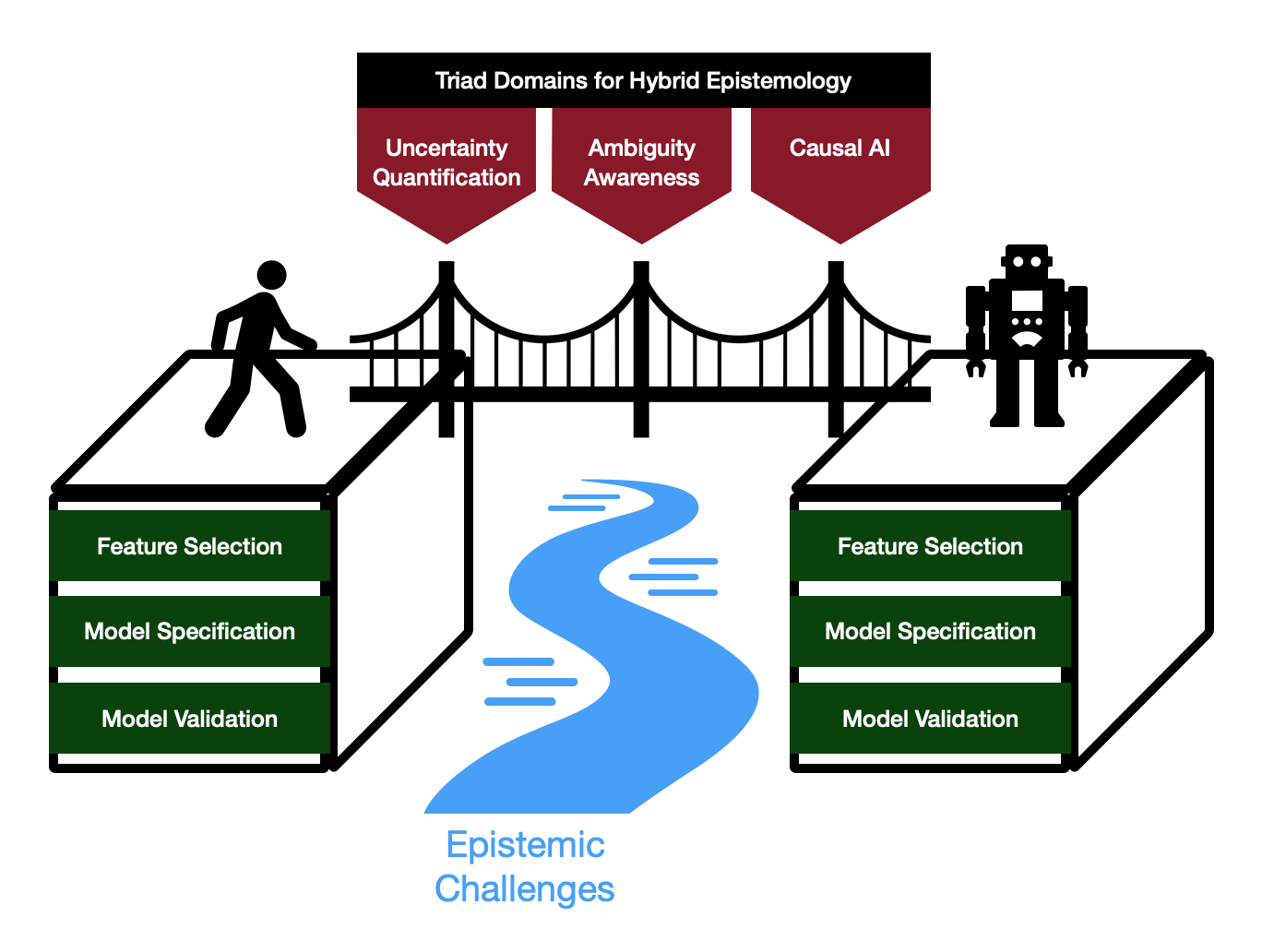

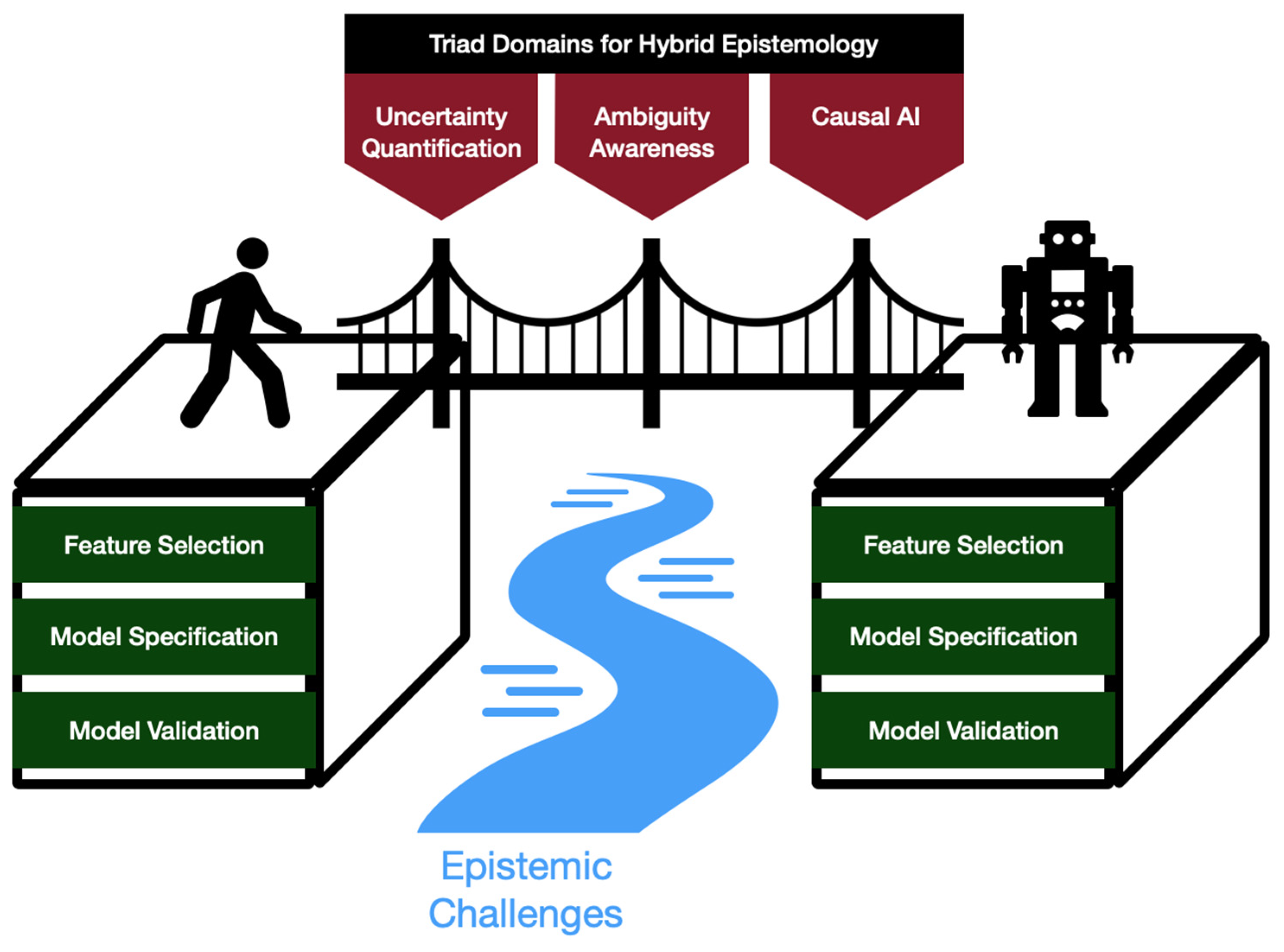

To structure our examination of these challenges, we draw from three complementary research domains: Uncertainty Quantification, Ambiguity Awareness, and Causal AI. While each is a substantial field in its own right, here we group them as an organizing Triad, selected for their combined potential to address the AI Socratic Paradox. Detailed discussion of Triad-aligned methods appears in

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5, within the context of specific lifecycle phases.

1.3. Contributions

This work advances the understanding of epistemic challenges and responses in personalized clinical AI through the following contributions (conceptually depicted in

Figure 1):

1. Conceptual Definition: We formalize the AI Socratic Paradox as a regress problem arising when clinical AI systems, intended to enable personalization, themselves become the precedent.

2. Lifecycle Mapping: We map manifestations of this paradox onto three critical phases of AI development (feature selection, model specification, and model validation) highlighting the distinct epistemic issues at each stage.

3. Hybrid Epistemology: We employ the established concept of Hybrid Epistemology, which frames clinical AI as a human–machine system with bidirectional reasoning, as a lens for analyzing challenges posed by the AI Socratic Paradox (Babushkina 2022).

4. Triad-Structured Review: We draw on three complementary research domains (Uncertainty Quantification, Ambiguity Awareness, and Causal AI), grouped here as an organizing Triad, for analyzing responses to the AI Socratic Paradox. We apply this scaffold in a structured review of methods across the AI development lifecycle, identifying advantages, limitations, and opportunities for embedding epistemic awareness into technical practice.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Overview of the AI Socratic Paradox framework: Triad domains (uncertainty quantification, ambiguity awareness, causal AI) offer a means of bridging human and machine cognitions into a hybrid system that overcomes epistemic challenges across the AI development lifecycle (feature selection, model specification, model validation).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Overview of the AI Socratic Paradox framework: Triad domains (uncertainty quantification, ambiguity awareness, causal AI) offer a means of bridging human and machine cognitions into a hybrid system that overcomes epistemic challenges across the AI development lifecycle (feature selection, model specification, model validation).

2. Related Works

While the Socratic paradox (“knowing that one knows nothing”) has appeared in some AI ethics discussions (Vega 2025), it has not, to our knowledge, been systematized as a framework for analyzing AI across the technical development lifecycle. This work examines the potential of such a framework when applied to Feature Selection, Model Specification, and Model Validation in clinical AI.

Existing scholarship at the intersection of AI and epistemology reflects a disciplinary divide (Stenseke 2022). Philosophical literature on epistemic challenges such as uncertainty, ambiguity, and the limitations of machine knowledge typically remains conceptual and only occasionally informs clinical AI system design (Babushkina 2022, Alvarado 2023, Durán 2022, López-Rubio 2021, van Baalen 2021). Technical reviews, meanwhile, have largely concentrated on algorithmic performance and validation, with less philosophical grounding (Lalli 2021, Bharati 2024, Morone 2025, Lamsaf 2025, Seoni 2023).

Approaches to uncertainty quantification, ambiguity management, and causal inference, though increasingly prominent, tend to be pursued in relative isolation. Existing reviews seldom integrate these strands through an explicit epistemic lens (Hüllermeier 2021, Jiao 2024, Campagner 2020). By structuring our analysis around the Socratic paradox and grouping relevant technical domains as a conceptual triad, this work seeks to highlight both the gaps and the potential for more integrated, epistemically informed frameworks in clinical AI.

3. Feature Selection as a Metacognitive Requirement

A model’s inferences are bounded by the information it ingests. Therefore, the model would require metacognitive awareness to reason about the sufficiency of its own feature set. This is the first facet of the AI Socratic Paradox: determining which variables and information (i.e. features) should constitute the model’s “world”.

Since the 1950s, feature selection has shifted from expert-driven curation of low dimensional datasets to algorithm-centric selection for high dimensional datasets. Early constraints on data volume (e.g. data collection costs) made human judgment tractable. Advances in multi-omics, wearables, and EHR logging now produce vast feature spaces. This exacerbates the “curse of dimensionality”, where signals are diluted as features grow (Mirza 2019). This necessitated formal, data-driven selection methods, classically grouped as filter, wrapper, and embedded approaches (Pudjihartono 2022).

Filter methods (such as Chi-squared test, Mutual Information and Pearson Correlation), select the features which are most highly correlated with the output values. Selection occurs independently of the model, before training begins (Remeseiro 2019, Brown 2012). Wrapper methods (such as recursive feature elimination) iteratively train the chosen classifier algorithm using various feature sets, selecting the set associated with the best performance (Guyon 2002). Embedded methods (such as LASSO regularization and gradient boosting) integrate feature selection into the classification algorithm itself, incentivizing the model to downweight features that do not contribute meaningfully (Pudjihartono 2022).

3.1. Epistemic Challenges in Feature Selection

Despite practical value, the aforementioned strategies optimize statistical convenience, not epistemic validity. Crucially, statistical selection methods cannot adjudicate whether features carry real-world meaning (Moraffah 2024). ML models do not learn concepts in the world; they fit patterns over whatever features they are given. Consequently, they will always find a pattern, even when inputs are mis-specified (Babushkina 2022). Poor feature selection thus entrenches mistaken assumptions about what is relevant or real. In this subsection, we introduce 2 implicated epistemic problems: feature ontology ambiguity and the identification problem.

Feature ontology ambiguity

Clinical variables can have varied causal-ontological relationships, including redundancy, confounding, mediation, and collider structures, among others (Malec 2023). Mishandling these relations yields biased or incoherent feature sets. For example, confounding bias arises when a variable shares a common cause with the outcome, inflating spurious associations (Skelly 2012). Collider bias arises when conditioning on a variable jointly influenced by exposure and outcome, inducing noncausal associations and compromising validity (Holmberg 2022).

Compounding this, many clinical constructs (e.g., fatigue, apathy, and hypertension) are inherently overlapping or vague, so models that assume crisp categories risk oversimplification (Newman-Griffis 2021, Daumas 2022, Pickering 2005).

Identification problem

Many clinically relevant constructs are difficult to observe directly, forcing reliance on proxy variables that may be misaligned. This predates ML: “surrogate endpoints” such as blood pressure or tumor size have historically failed to track true end-organ function (Aronson 2005). For example, in the 1990 Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST), antiarrhythmics that improved the surrogate endpoints actually worsened mortality (Epstein 1991).

ML can amplify such mismatches. In the widely deployed Optum algorithm, cost was used as a proxy for illness severity. However, because Black patients often incur lower expenditures despite similar or worse health, the system systematically under-referred Black patients for extra care (Obermeyer 2019). Proxy misalignment can silently propagate harmful downstream decisions.

3.2. Triad-Informed Approaches to Feature Selection Challenges

The frictions in 3.1 show why algorithmic selectors are insufficient: they optimize statistical convenience under fixed representations and cannot assess causal role, conceptual clarity, or measurement validity. Earlier, we noted the complementary limitation of expert-only curation in high dimensional settings. Taken together, these gaps motivate a hybrid, iterative workflow (Pudjihartono 2022). In this section, we highlight emerging triad-informed approaches which address these epistemic challenges and thereby enable hybrid feature selection.

Addressing feature ontology ambiguity

Causal Inference methods show promise in resolving ontological ambiguities. They use Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs) to explicitly map causal-ontological relationships. For example, Structural Causal Models (SCMs) use DAGs to select covariates that minimize confounding, close backdoor paths, and ensure valid causal inference (Lamsaf 2025). A 2023 ICU study used SCMs to emulate a target trial of oxygen targets and estimate 90-day mortality effects, illustrating clinical applicability (Gani 2023). SCMs have the advantage of enabling counterfactual (“what if”) queries (Tikka 2023). However, they require fully specified causal and measurement equations for every feature, a rigid demand that can lead to arbitrary assumptions when clinical constructs are vague (Bareinboim 2016).

Causal Bayesian Network (CBN) models, a subtype of SCMs, have the added flexibility of encoding graph dependencies as joint probability distributions (Mascaro 2023). In this setting, a variable’s Markov blanket (its parents, children, and the other parents of those children) “screens” it off from the rest of the network, supplying all information needed for optimal prediction. The smallest such shielding set is the Markov boundary, which serves as a principled basis for excluding redundant or irrelevant features (Triantafillou 2021). CBNs allow encoding uncertain or partially known dependencies as probabilistic relationships without committing to precise functional forms. However, CBNs still require each node to represent a well-defined variable and cannot by themselves resolve conceptual vagueness or overlapping clinical constructs (Wagan 2024).

For this purpose, fuzzy logic can represent graded membership and partial truths, capturing the inherently imprecise boundaries of many clinical features and improving selection in settings where categories are not crisp (Kempowsky-Hamon 2015). Fuzzy feature selection has recently been validated in the context of breast cancer (Paja 2023). While fuzzy approaches effectively handle vagueness, they cannot resolve relational ambiguities without the use of causal inference methods. A combination of the two may be ideal (Saki 2024).

Addressing the identification problem

To address the misalignment of proxy variables, proxy-target relationships must be made explicit and testable. Structural Equation Models (SEMs) address this using a “measurement model” and a “structural model”. The measurement model links latent variables (true unobserved targets) to observed proxies; the structural model links the latent variables to each other. This dual structure allows SEMs to aggregate multiple proxies for each target, quantifying misalignment (Christ 2014). Application studies have shown SEM’s success in health risk prediction, improving fairness among patient cohorts (Kraus 2024). A unique advantage of SEMs is their ability to quantify measurement error, although they require (sometimes impractically) that all relevant confounders have been measured (Christ 2014, Sullivan 2021).

A complementary approach, Proximal Causal Inference (PCI), enables the identification of causal effects in the presence of unmeasured confounders using proxies for the confounders (Eric 2024). In a study, PCI successfully predicted the effect of right-side heart catheterization on 30-day survival, even when patients’ disease severities (important confounders) were not known (Liu 2025). However, PCI’s limitation is that it can only use proxies that satisfy strict validity conditions (Rakshit 2025).

In summary, feature selection underpins model reasoning, but faces epistemic challenges that algorithmic methods alone cannot resolve.

Feature ontology ambiguity and the

identification problem call for hybrid strategies that integrate domain expertise into AI methods (summarized in

Table 1), using causal inference, ambiguity-aware frameworks, and explicit modeling of latent structures.

4. Model Specification as a Metacognitive Requirement

AI models are bounded by their specifications, so a model would require metacognitive awareness to judge whether its own specifications are suitable. This is the second aspect of the AI Socratic Paradox: specifying the system.

Model Specification operates at two scopes: a narrow machine-focused scope and a broader hybrid human-machine scope. The narrow scope is well-covered by existing practices, whereas the broader scope remains an active research frontier.

In the narrow sense, model specification entails choosing model architecture and hyperparameter settings. Common families of architectures in healthcare ML include tree-based models, convolutional neural networks, recurrent neural networks, transformers, graph-based models, and Bayesian models (Woodman 2023). Each involves tradeoffs in computational cost, performance, and interpretability. Hyperparameters, such as learning rate, depth, or number of layers, are typically tuned by k-fold cross-validation using grid search, random search, or Bayesian optimization (Vincent 2023).

Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) systems automate core specification choices by defining a search space of algorithms and hyperparameters, applying a search strategy to explore candidates, and using performance estimation to select models (Vincent 2023). AutoML largely addresses machine-focused specification.

4.1. Epistemic Challenges in Model Specification

At the broader human-machine level, a central question arises: how should the model be situated within human decision-making processes?. Troqe et al. emphasize that situatedness is non-trivial, and that AI tools must be embedded in the organizational and cognitive context of human sensemaking (Troqe 2024). Building on this premise, we specify two epistemic frictions that impede situatedness in practice: the signification problem and misaligned class ontologies.

Signification problem

In supervised learning, labels are assigned to data points. For humans, labels signify concepts; for models, labels signify patterns. For example, “dog” denotes a conceptual category for humans, whereas for the model the label “dog” indicates that an image shares feature patterns with other images labeled “dog” (Babushkina 2022).

Patterns are not concepts. Learned patterns may be trivial or spuriously correlated rather than clinically meaningful, such as background or acquisition artifacts. This gap leads to failures in hybrid reasoning (Babushkina 2022). For example, pneumothorax models have focused on chest tube image artifacts rather than the pleural line, yielding confident but non-conceptual signals that miss cases without tubes (Banerjee 2023).

Misaligned class ontologies

Superficially, the task of selecting a diagnosis resembles an ML classification task. However, the two are ontologically misaligned. ML classes are crisply defined and mutually exclusive (Hsu 2002), whereas disease categories are more ontologically messy (Bodenreider 2004).

Diseases can overlap (for example, SIRS and sepsis share criteria and presentations), evolve with guideline changes (for example, the definition of hypertension has repeatedly shifted), and depend on context (Baddam 2025, Pickering 2005). Categories are reconfigured over time (such as folding Asperger’s syndrome into autism spectrum disorder in DSM-5) reflecting historical and sociocultural factors as much as biology (King 2016). Some are diagnoses of exclusion which are only established after alternative causes are ruled out, as with fibromyalgia– although even this is contested across the literature (Qureshi 2021, Berwick 2022). This fluidity and overlap are not captured by traditional ML classification.

4.2. Triad-Informed Approaches to Model Specification Challenges

Reverberi et. al. propose that Hybrid human–AI decisions are Bayesian-like: clinicians integrate model outputs with prior knowledge and situational context (Reverberi 2022). This requires that model insights are interpretable as evidence. However, challenges like the signification problem and misaligned class ontology hinder this integration. In this section, we review Triad-informed solutions that address these challenges.

Addressing the signification problem

The signification problem (i.e., the gap between machine patterns and human concepts) has long been characterized as a problem of regress, implying that no technical approach can fully resolve it (Harnad 1990). However, Concept Alignment attempts to mitigate the practical impacts of this gap by structuring representation spaces to better approximate human conceptual spaces (Rane 2024, Muttenthaler 2025). Existing approaches fall into two groups: measuring alignment and refining alignment.

Measurement techniques such as Representational Similarity Analysis (RSA) assess how well the model’s internal similarity structure matches human conceptual understanding. RSA compares model-derived pairwise distances among concepts to human-derived pairwise similarity judgments for the same concept pairs (Ogg 2024). RSA is advantageous due to its scalable data collection approach using simple similarity judgments, but it is limited by its inability to capture hierarchical relationships. In contrast, Abstraction Alignment uses explicit hierarchical medical taxonomies to assess not only whether the model aligns with human concepts, but also whether it considers the correct level of abstraction (an illustrative analogy: not grouping zebras and barcodes together just because they both have stripes). Abstraction Alignment has successfully identified model–human concept misalignments in image classification tasks (such as models learning visual rather than biological abstractions) but clinical validation remains limited (Boggust 2025).

In the refining phase of Concept Alignment, model representations are adjusted to better match concepts. Contrastive learning, the most established refinement approach, pulls together representations of conceptually similar instances and pushes apart dissimilar ones (Marjieh 2025). A limitation is that contrastive learning can mistakenly push apart semantically similar samples due to false negative pairings, which arise because the method assumes every non-positive pairing in the batch is a negative (Huynh 2022). Nonetheless, studies demonstrate gains on real-world EHR and imaging tasks (Zang 2021, Ghesu 2022). Notably, ConceptCLIP shows that contrastive learning guided by clinical concepts improves zero-shot accuracy and concept-level explainability across several medical imaging tasks (Nie 2025).

Addressing misaligned class ontologies

The mismatch between crisp ML classes and messy clinical categories can distort clinical reasoning. To mitigate this, models should integrate ontological structures directly into training to better track clinical realities.

Concept Bottleneck Models (CBMs) enforce a human-defined concept layer through which predictions must pass, making intermediate concepts explicit and editable. This ties the model’s decision space to the ontology clinicians actually use (Koh 2020). Recent clinical variants demonstrate that concept-based pipelines can maintain accuracy while improving interpretability and clinician trust in specialized tasks such as choroidal tumor and skin disease diagnosis (Wu 2025, Pang 2024). A practical limitation, however, is the need for hand-annotated concepts, which creates labeling burden and potential inaccuracies (Park 2024).

Another promising approach, involving Bayesian models with domain-informed priors, provides a probabilistic path to aligning ontologies. It uses a loss function ϕ, specified by a domain expert, to encode clinical knowledge. Φ effectively regularizes the model’s priors toward ontologically coherent hypotheses. On a MIMIC-IV clinical task, this approach improved accuracy and reduced rule violations compared to standard priors. However, a limitation is that the priors are architecture-specific, meaning they must be relearned every time the model’s structure changes. This process can be computationally expensive and sometimes infeasible (Sam 2024).

In summary, model specification extends beyond choices of architecture and hyperparameters. It also encompasses the deeper epistemic challenges of integrating machine reasoning with human clinical reasoning. Addressing this requires Triad-informed models (summarized in

Table 2) to bridge human–machine epistemologies and enable trustworthy clinical decision support.

5. Model Validation as a Metacognitive Requirement

Evaluating the effectiveness of an AI system is critical, especially in clinical medicine. We designate Model Validation as the third metacognitive aspect of the AI Socratic Paradox: does the system truly accomplish its intended function?

This task has proven challenging. High-profile clinical AI systems often fail in real-world use despite strong claims of efficacy. For example, an external validation of Epic’s widely deployed sepsis prediction model found it identified only 33% of true sepsis cases and generated frequent false alarms, far below the performance indicated during internal trials (Wong 2021). Similarly, Google’s diabetic retinopathy system, when trialed in Thai clinics, suffered markedly reduced performance due to real-world factors like poor lighting and image quality, absent from the original validation datasets (Heaven 2020).

Model validation, like specification, must occur at multiple levels. We identify three tiers: internal validation (performance on seen data), external validation (generalization to new contexts), and situated validation, which assesses the model’s behavior and trustworthiness when embedded within a broader human–machine system. The first two are relatively narrow and machine-focused, while the third, which is often overlooked, demands a broader lens.

Internal validation is evaluation within the context of the training dataset and is addressed by well-established methods. K-fold cross validation methods repeatedly train and test the model on different data subsets, reducing overfitting and improving reliability compared to a single split. Bootstrap validation samples the dataset with replacement to bolster stability (Steyerberg 2019).

External validation is evaluation on data from unfamiliar settings to evaluate generalizability. Established approaches include testing on independent datasets from new institutions or populations, temporal external validation using data from later periods, and prospective validation, which assesses real-time predictions in clinical practice (Austin 2016, Ramspek 2021).

However, even a model that performs well in both internal and external validation may nevertheless fail if its role within the clinical workflow is misunderstood or unstable. This third tier, situated validation, asks whether the model functions effectively as part of a hybrid decision-making system (Salwei 2022).

5.1. Epistemic Challenges in Model Validation

Situated validation is an emerging topic. There is growing consensus that clinical AI must move beyond the prevailing “linear paradigm”, where models are validated once before deployment and then assumed valid throughout their lifespan (Dolin 2025). Rosenthal et al propose a dynamic systems approach in which models are continually and iteratively re-evaluated alongside the evolving clinical environment (Rosenthal 2025).

This dynamic validation paradigm depends on feedback loops between models and clinicians, requiring a shared and fluent hybrid epistemology. Several persistent barriers impede this fluency. Here we address two major challenges: misaligned uncertainty semantics and domain shift vulnerability.

Misaligned uncertainty semantics

Philosophers Babuskina and Votsis highlight a fundamental misalignment between machine outputs and human interpretations. Deep learning models’ outputs commonly take the form “85% pneumonia, 10% cancer, 5% tuberculosis” (Babushkina 2022). These percentages are softmax-transformed logits from the final layer of the neural network (Zhang 2020).

These should not be interpreted as probabilities. For example, it is incorrect to conclude that “the patient more likely has pneumonia than cancer”. The model has no basis for inferring frequentist probabilities. Instead, these scores represent degrees of possibility. Deep learning models implicitly convert labels into fuzzy sets, and then determine degrees of membership for each input instance. Therefore a more accurate interpretation is: ‘the patterns in the input sample are more easily attributed to patterns in pneumonia cases than those in cancer cases’ (Babushkina 2022). High possibility is not necessarily related to high probability (Zadeh 1999). The central question is how these possibility scores should inform clinical judgement.

Domain Shift Vulnerability

AI models often falter when deployed in environments that differ from those seen in training. This problem, known as domain shift, frequently arises in clinical practice due to changes in patient populations, disease prevalence, protocols, technology, and methods of data acquisition (Musa 2025). In unfamiliar scenarios, models experience increased epistemic uncertainty and may provide overconfident predictions. This undermines trust and safety (Blattmann 2025).

Mitigating the risks requires more than uncertainty reporting. It is crucial to distinguish epistemic uncertainty (arising from the model’s limited perspective) from aleatoric uncertainty (arising from inherent noise in the data). Developing methods for separating and communicating both remains an open challenge (Bickford 2025).

5.2. Triad-Informed Approaches to Model Validation Challenges

In this subsection, we present a combination of Triad-informed approaches which help to mitigate the above epistemic challenges.

Addressing misaligned uncertainty semantics

Conformal prediction is one approach to resolving the gap between possibility (as expressed by deep learning models) and probability (as required for actionable clinical insights). It is a model-agnostic wrapper that translates fuzzy softmax outputs into statistical guarantees. It creates prediction sets that, at a user-specified coverage level (e.g. 95%), are guaranteed to contain the true answer (Angelopoulos 2022). Conformal prediction has been validated in clinical workflows, significantly reducing misclassification in prostate-biopsy slides, multiple sclerosis subtype detection, and melanoma skin-lesion triage (Olsson 2022, Sreenivasan 2025, Fayyad 2024). Shanmugam et al improve upon conformal prediction by employing Test-Time Augmentation, shrinking conformal sets by up to 30 percent without loss of accuracy. However, an enduring limitation is that conformal prediction hinges on softmax scores accurately ranking candidate labels (Shanmugam 2025).

Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) more directly integrate probability theory into deep learning by treating each network weight as a probability distribution rather than a single fixed value. This facilitates explicit representation of both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty, making outputs interpretable as genuine probabilities (Kendall 2017). BNNs were evaluated in the context of hybrid clinical workflows by demonstrating their ability to identify and refer to uncertain cases for human medical expert review, enhancing overall performance (Liebig 2017). However, reliability of BNNs is contingent upon representative datasets and well-chosen priors, which are not always possible with clinical data (Kendall 2017).

Addressing domain-shift vulnerability

The first step in improving robustness to domain shift is to detect inputs that are significantly different from the model’s training data. Out-Of-Distribution (OOD) Detection, a research area in Uncertainty Quantification, provides a number of suitable approaches.

Out-of-Distribution detector for Neural networks (ODIN) is a baseline OOD detection method. It perturbs inputs in such a way that the model’s confidence improves for in-distribution inputs, but not for others. It flags the latter as OOD samples. Generalized ODIN (G-ODIN), improves on this by eliminating the need for validation data from the foreign distributions (Hsu 2020). These approaches are versatile because they can be implemented as post hoc wrappers on softmax outputs with low computational overhead (Liang 2017). However, they inherit the tendency of softmax scores to be overconfident under high epistemic uncertainty, which limits reliability under shift (Guo 2017).

A second class of OOD approaches, called Mahalanobis Distance-Based Methods, examine internal feature embeddings at a chosen network layer. They measure the distance in feature space from a test sample to class-specific centroids computed from in-distribution training data. Large distances suggest an OOD sample (Lee 2018). This approach has been validated across chest CT distribution shifts and MRI applications for segmentation (González 2022). A limitation is that Mahalanobis methods assume approximately Gaussian, well-clustered features at the chosen layer, and performance degrades when those assumptions do not hold (Müller 2025). A third OOD approach, Deep Ensembles, offer the highest performance with the highest computational price. They combine the predictions of multiple independently trained networks. Agreement suggests in-distribution status, while disagreement indicates an OOD sample (Lakshminarayanan 2017).

Detecting domain shift is only the first step. Adversarial Domain Adaptation goes further by adapting models to a target domain, even without labeled target data. It trains a feature extractor to produce domain-invariant representations while a domain discriminator tries to identify the source versus target origin. By learning to fool the discriminator, the feature extractor aligns representations across domains, which reduces performance loss under shift (HassanPour 2023). ADA has been validated retrospectively for chest X-ray classification, but prospective clinical validation remains limited (Mus 2025).

Whereas ADA follows the linear paradigm which may not be sufficiently adaptive for dynamic clinical environments, Drift-triggered Continual Learning is more adaptive. It uses statistical tests such as maximum mean discrepancy to detect distributional drift and trigger model updates using new data. A drawback to this approach is the risk of “catastrophic forgetting”, where frequent updates to accommodate new data erode previously learned performance (Subasri 2025).

In sum, model validation is essential yet persistently challenging. Real-world failures underscore the need for dynamic, in-workflow validation, and two key frictions hinder it: misaligned uncertainty semantics and domain shift. Triad informed methods (summarized in

Table 3), including improved uncertainty quantification, OOD detection, and adaptive learning, can mitigate these frictions and help systems remain reliable and safe as data and practice evolve. Validation should be a continuous process that integrates humans and models across the clinical AI lifecycle.

6. Discussion

6.1. Towards an Integrated AISP-Aware Ecosystem

Section 3,

Section 4 and

Section 5 identified distinct epistemic challenges across

Feature Selection,

Model Specification, and

Model Validation, with Triad-informed techniques addressing each challenge individually. However, these challenges are all manifestations of the underlying AI Socratic Paradox (AISP). Designing AISP-aware systems requires end-to-end frameworks that unify Triad approaches into an ecosystem.

Foundational scaffolding exists, such as SALIENT, a comprehensive implementation framework that structures clinical AI development along two intersecting axes: project stages (problem definition, solution design, development/testing, implementation, and ongoing monitoring) and cross-cutting themes (technical validity, clinical utility, ethics/equity, human–machine interaction, and governance/oversight). This matrix ensures that each theme is addressed at every stage of the lifecycle (Vegt 2023). Another framework, proposed by Shimgekar et al., automates the lifecycle using a modular Agentic AI pipeline (Shimgekar 2025). Building on such frameworks may make it operationally feasible to embed the AISP-aware practices emphasized in this paper.

A key limitation of most implementation frameworks is linearity, whereas epistemic uncertainty is nonlinear (Lavin 2022). Insights or failures at one stage can have implications for earlier or later stages. For instance, validation failures may expose proxy identification problems requiring upstream feature re-engineering, while concept misalignment in model specification may necessitate downstream validation protocol adjustments. Addressing such interdependencies calls for dynamic feedback loops that connect all phases of development rather than progressing in a fixed order (Li 2025).

Recent work shows the feasibility of this paradigm: Rosenthal et al. demonstrate benefits of dynamic deployment and continuous retraining (Rosenthal 2025), while Feng et al. propose AI quality improvement units for ongoing monitoring and governance (Feng 2022). In sum, realizing an AISP-aware ecosystem calls for extending current frameworks with nonlinear epistemic feedback throughout the system.

6.2. AISP as an Impetus for Epistemic Humility

However, despite significant technical advances, the AI Socratic Paradox persists. At its core lies a philosophical regress: for an AI model M to determine the limits of its own knowledge, it would require a second evaluator model M′, which itself would require evaluation by M′′, and so on, ad infinitum. This regress cannot be eliminated by technical approaches, including the Triad methods discussed in this paper.

Philosophers of medicine have emphasized that irreducible uncertainty, contextual nuance, and tacit knowledge are inseparable from clinical practice (Greenhalgh 2018, Topol 2019). “N=1” medicine resists exhaustive codification and algorithmic closure (Mol 2008). Breakthroughs often hinge on a clinician’s ability to think beyond established protocols, as exemplified by Dr. Najjar’s well-known diagnosis of Susannah Cahalan (Cahalan 2012).

The enduring lesson is epistemic humility. While technical progress can asymptotically reduce uncertainty, it cannot eradicate unknowns and ambiguities in clinical care. The responsible course is to employ AI as a tool for insight, without allowing it to eclipse creative, relational, and intuitive dimensions of person-centered medicine.

Author Contributions

Anshuman Madhukar: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Dr. Suhas Srinivasan (Stanford University) for his mentorship and encouragement in developing this review. Dr. Srinivasan provided valuable feedback on the outline and offered comments on the manuscript, motivating the author to pursue publication.

Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

During the preparation of this work the author(s) used Perplexity AI in order to support language editing and clarity of expression. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH. Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet. 2017;390(10092):415-423.

- Guyatt G, Cairns J, Churchill D, et al. Evidence-based medicine. A new approach to teaching the practice of medicine. JAMA. 1992;268(17):2420-2425.

- Nikles J, Mitchell G. The essential role of N-of-1 trials in the movement toward personalized medicine. Med Care. 2015;53(4):301-306.

- Troqe, B., Lakemond, N.., & Holmberg, G.. (2024). From Half-Truths to Situated Truths: Exploring Situatedness in Human-AI Collaborative Decision-Making in the Medical Context. Journal of Competences, Strategy & Management, 12, 1–15.

- Buchanan BG, Shortliffe EH. Rule-Based Expert Systems: The MYCIN Experiments of the Stanford Heuristic Programming Project. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1984.

- Ezugwu AE, Ho Y-S, Egwuche OS, Ekundayo OS, Van Der Merwe A, Saha AK, Pal J. Classical Machine Learning: Seventy Years of Algorithmic Learning Evolution. Data Intelligence. Accepted July 15, 2024. arXiv:2408.01747.

- Ullah R, Sarwar N, Alatawi MN, et al. Advancing personalized diagnosis and treatment using deep learning architecture. Frontiers in Medicine. 2025;12:1545528.

- Ahmed N, Devitt KS, Keshet I, et al. Epistemological humility in the era of COVID-19. Patient Exp J. 2024;11(2):1-8.

- Katz RA, Graham SS, Buchman DZ. The need for epistemic humility in AI-assisted pain assessment. Med Health Care Philos. 2025 Mar 15;28(2):339–349. [CrossRef]

- Desai RJ, Glynn RJ, Solomon SD, Claggett B, Wang SV, Vaduganathan M. Individualized Treatment Effect Prediction with Machine Learning — Salient Considerations. NEJM Evidence. 2024 Apr;3(4):EVIDoa2300041. [CrossRef]

- Babushkina D, Votsis A. The ethics and epistemology of explanatory AI in medicine and psychiatry. Ethics and Information Technology. 2022 Sep;24(3–4):443–56. [CrossRef]

- Vega, C. Knowing you know nothing in the age of generative AI. Nature Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 2025;12:471. [CrossRef]

- Stenseke, J. Interdisciplinary Confusion and Resolution in the Context of Moral Machines. Sci Eng Ethics. 2022 May 19;28(3):24. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alvarado, R. AI as an Epistemic Technology. Sci Eng Ethics 29, 32 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Durán, J.M., Sand, M. & Jongsma, K. The ethics and epistemology of explanatory AI in medicine and healthcare. Ethics Inf Technol 24, 42 (2022). [CrossRef]

- López-Rubio, E., Ratti, E. Data science and molecular biology: prediction and mechanistic explanation. Synthese 198, 3131–3156 (2021). [CrossRef]

- van Baalen S, Boon M, Verhoef P. From clinical decision support to clinical reasoning support systems. J Eval Clin Pract. 2021 Jun;27(3):520-528. Epub 2021 Feb 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lalli Myllyaho, Mikko Raatikainen, Tomi Männistö, Tommi Mikkonen, Jukka K. Nurminen. Systematic literature review of validation methods for AI systems. Journal of Systems and Software, Volume 181, 2021, 111050, ISSN 0164-1212. [CrossRef]

- S. Bharati, M. R. H. Mondal and P. Podder, “A Review on Explainable Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare: Why, How, and When?,” in IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 1429-1442, April 2024. [CrossRef]

- Morone G, De Angelis L, Martino Cinnera A, Carbonetti R, Bisirri A, Ciancarelli I, Iosa M, Negrini S, Kiekens C, Negrini F. Artificial intelligence in clinical medicine: a state-of-the-art overview of systematic reviews with methodological recommendations for improved reporting. Front Digit Health. 2025 Mar 5;7:1550731. [CrossRef]

- Lamsaf, A.; Carrilho, R.; Neves, J.C.; Proença, H. Causality, Machine Learning, and Feature Selection: A Survey. Sensors 2025, 25, 2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoni S, Jahmunah V, Salvi M, Barua PD, Molinari F, Acharya UR. Application of uncertainty quantification to artificial intelligence in healthcare: A review of last decade (2013–2023). Computers in Biology and Medicine. 2023;165:107441. [CrossRef]

- Hüllermeier, E., Waegeman, W. Aleatoric and epistemic uncertainty in machine learning: an introduction to concepts and methods. Mach Learn 110, 457–506 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Jiao L, Wang Y, Liu X, Li L, Liu F, Ma W, Guo Y, Chen P, Yang S, Hou B. Causal Inference Meets Deep Learning: A Comprehensive Survey. Research. 2024 Sep 10;7:0467. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Campagner A, Cabitza F, Ciucci D. Three-Way Decision for Handling Uncertainty in Machine Learning: A Narrative Review. Rough Sets. 2020 Jun 10;12179:137–52. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Mirza B, Wang W, Wang J, Choi H, Chung NC, Ping P. Machine Learning and Integrative Analysis of Biomedical Big Data. Genes (Basel). 2019 Jan 28;10(2):87. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pudjihartono N, Fadason T, Kempa-Liehr AW, O’Sullivan JM. A Review of Feature Selection Methods for Machine Learning-Based Disease Risk Prediction. Front Bioinform. 2022 Jun 27;2:927312. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Remeseiro B, Bolon-Canedo V. A review of feature selection methods in medical applications. Comput Biol Med. 2019 Sep;112:103375. Epub 2019 Jul 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown G, Pocock A, Zhao MJ, Luján M. Conditional likelihood maximisation: a unifying framework for information theoretic feature selection. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2012;13:27-66.

- Guyon, I., Weston, J., Barnhill, S. et al. Gene Selection for Cancer Classification using Support Vector Machines. Machine Learning 46, 389–422 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Moraffah R, Sheth P, Vishnubhatla S, Liu H. (2024). Causal Feature Selection for Responsible Machine Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.02696.

- Malec SA, Taneja SB, Albert SM, Elizabeth Shaaban C, Karim HT, Levine AS, Munro P, Callahan TJ, Boyce RD. Causal feature selection using a knowledge graph combining structured knowledge from the biomedical literature and ontologies: A use case studying depression as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. J Biomed Inform. 2023 Jun;142:104368. [CrossRef]

- Skelly AC, Dettori JR, Brodt ED. Assessing bias: the importance of considering confounding. Evidence-Based Spine Care Journal. 2012 Feb;3(1):9–12. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Holmberg MJ, Andersen LW. Collider Bias. JAMA. 2022;327(13):1282–1283. [CrossRef]

- Newman-Griffis D, Divita G, Desmet B, Zirikly A, Rosé CP, Fosler-Lussier E. Ambiguity in medical concept normalization: An analysis of types and coverage in electronic health record datasets. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021 Mar 1;28(3):516-532. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Daumas L, Corbel C, Zory R, Corveleyn X, Fabre R, Manera V, Robert P. Associations, overlaps and dissociations between apathy and fatigue. Scientific Reports. 2022 May 5;12:7387. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Pickering TG. Do we really need a new definition of hypertension? Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2005;7(12):702-704.

- Aronson JK. Biomarkers and surrogate endpoints. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2005 May;59(5):491-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Epstein AE, Bigger JT Jr, Wyse DG, Romhilt DW, Reynolds-Haertle RA, Hallstrom AP. Events in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST): mortality in the entire population enrolled. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991 Jul;18(1):14-9. Erratum in: J Am Coll Cardiol 1991 Sep;18(3):888. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019 Oct 25;366(6464):447-453. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gani MO, Kethireddy S, Adib R, Hasan U, Griffin P, Adibuzzaman M. Structural causal model with expert augmented knowledge to estimate the effect of oxygen therapy on mortality in the ICU. Artif Intell Med. 2023 Mar;137:102493. [CrossRef]

- Tikka, “Identifying Counterfactual Queries with the R Package cfid”, The R Journal, 2023.

- Bareinboim E, & Pearl J, Causal inference and the data-fusion problem, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 (27) 7345-7352. (2016). [CrossRef]

- Triantafillou S, Jabbari F, Gregory F. Cooper Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, PMLR 161:1434-1443, 2021.

- Mascaro, S., Wu, Y., Woodberry, O. et al. Modeling COVID-19 disease processes by remote elicitation of causal Bayesian networks from medical experts. BMC Med Res Methodol 23, 76 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wagan AA, Talpur S, Narejo S. Clustering uncertain overlapping symptoms of multiple diseases in clinical diagnosis. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024 Oct 2;10:e2315. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kempowsky-Hamon T, Valle C, Lacroix-Triki M, Hedjazi L, Trouilh L, Lamarre S, Labourdette D, Roger L, Mhamdi L, Dalenc F, Filleron T, Favre G, François JM, Le Lann MV, Anton-Leberre V. Fuzzy logic selection as a new reliable tool to identify molecular grade signatures in breast cancer--the INNODIAG study. BMC Med Genomics. 2015 Feb 7;8:3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paja, W. Application of the Fuzzy Approach for Evaluating and Selecting Relevant Objects, Features, and Their Ranges. Entropy. 2023 Aug 17;25(8):1223. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Saki A, Faghihi U. Integrating Fuzzy Logic with Causal Inference: Enhancing the Pearl and Neyman-Rubin Methodologies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.13731. 2024 Jun 19.

- Christ SL, Lee DJ, Lam BL, Diane ZD. Structural Equation Modeling: A Framework for Ocular and Other Medical Sciences Research. Ophthalmic Epidemiology. 2014 Feb;21(1):1–13. [CrossRef] [PubMed Central]

- Kraus E, Kern C. Measurement Modeling of Predictors and Outcomes in Algorithmic Fairness. In: Proceedings of the 3rd AAAI Workshop on Algorithmic Fairness through the Lens of Time (AFFECT 2024). CEUR Workshop Proceedings; 2024.

- Sullivan AJ, VanderWeele TJ. Bias and sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounders in linear structural equation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.05775. 2021.

- Tchetgen EJ, Ying A, Cui Y, Shi X, Miao W. “An Introduction to Proximal Causal Inference.” Statist. Sci. 39 (3) 375 - 390, August 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Park C, Li K, Tchetgen EJ, Regression-based proximal causal inference, American Journal of Epidemiology, Volume 194, Issue 7, July 2025, Pages 2030–2036. [CrossRef]

- Rakshit P, Shi X, Tchetgen Tchetgen E. Adaptive Proximal Causal Inference with Some Invalid Proxies. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.19623. 2025 Jul 25.

- Woodman RJ, Mangoni AA. A comprehensive review of machine learning algorithms and their application in geriatric medicine: present and future. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2023 Nov;35(11):2363-2397. Epub 2023 Sep 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vincent, A.M., Jidesh, P. An improved hyperparameter optimization framework for AutoML systems using evolutionary algorithms. Sci Rep 13, 4737 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Banerjee I, Bhattacharjee K, Burns JL, Trivedi H, Purkayastha S, Seyyed-Kalantari L, Patel BN, Shiradkar R, Gichoya J. “Shortcuts” Causing Bias in Radiology Artificial Intelligence: Causes, Evaluation, and Mitigation. J Am Coll Radiol. 2023 Sep;20(9):842-851. Epub 2023 Jul 27. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hsu CW, Lin CJ. A comparison of methods for multi-class support vector machines. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks. 2002;13(2):415–425.

- Bodenreider, O. The Unified Medical Language System (UMLS): integrating biomedical terminology. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32(Database issue):D267–D270.

- Baddam S, Burns B. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. [Updated 2025 Jun 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547669/.

- King BH, Navot N, Bernier R, Webb SJ. Update on diagnostic classification in autism. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2014 Mar;27(2):105-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qureshi AG, Jha SK, Iskander J, Avanthika C, Jhaveri S, Patel VH, Rasagna Potini B, Talha Azam A. Diagnostic Challenges and Management of Fibromyalgia. Cureus. 2021 Oct 11;13(10):e18692. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Berwick R, Barker C, Goebel A; guideline development group. The diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome. Clinical Medicine (London). 2022 Nov;22(6):570-574. [CrossRef]

- Reverberi C, Rigon T, Solari A, Hassan C, Cherubini P; GI Genius CADx Study Group; Cherubini A. Experimental evidence of effective human-AI collaboration in medical decision-making. Sci Rep. 2022 Sep 2;12(1):14952. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harnad, S. The symbol grounding problem. Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena. 1990;42(1–3):335–346.

- Rane S, Bruna PJ, Sucholutsky I, Kello C, Griffiths TL. Concept Alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.08672. 2024 Jan 9.

- Muttenthaler L, Utsumi Y, Brielmann AA, Cichy RM, Hebart MN. Human alignment of neural network representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.01201. 2025 Feb 16.

- Ogg M, Wolmetz M. Measuring Alignment between Human and Artificial Intelligence with Representational Similarity Analysis. In: Proceedings of the Cognitive Computational Neuroscience Conference (CCNeuro 2024). 2024.

- Boggust A, Bang H, Strobelt H, Satyanarayan A. Abstraction Alignment: Comparing Model-Learned and Human-Encoded Conceptual Relationships. In: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’25), April 26–May 01, 2025, Yokohama, Japan. ACM, New York, NY, USA. [CrossRef]

- Marjieh R, Kumar S, Campbell D, Zhang L, Bencomo G, Snell J, Griffiths TL. Learning Human-Aligned Representations with Contrastive Learning and Generative Similarity. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.19420. 2025 Jan 31.

- Huynh T, Kornblith S, Walter MR, Maire M, Khademi M. “Boosting Contrastive Self-Supervised Learning with False Negative Cancellation,” 2022 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2022, pp. 986-996. [CrossRef]

- Zang C, Wang F. SCEHR: Supervised Contrastive Learning for Clinical Risk Prediction using Electronic Health Records. Proc IEEE Int Conf Data Min. 2021 Dec;2021:857-866. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghesu FC, Georgescu B, Mansoor A, Yoo Y, Neumann D, Patel P, Vishwanath RS, Balter JM, Cao Y, Grbic S, Comaniciu D. Contrastive self-supervised learning from 100 million medical images with optional supervision. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2022 Nov;9(6):064503. Epub 2022 Nov 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nie Y, He S, Bie Y, Wang Y, Chen Z, Yang S. ConceptCLIP: Towards Trustworthy Medical AI via Concept-Enhanced Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.15579. 2025.

- Koh PW, Nguyen T, Tang YS, Mussmann S, Pierson E, Kim B, Liang P. Concept Bottleneck Models. Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). PMLR 119:5338–5348, 2020.

- Wu Y, Liu Y, Yang Y, Yao MS, Yang W, Shi X, Yang L, Li D, Liu Y, Yin S, Lei C, Zhang M, Gee JC, Yang X, Wei W, Gu S. A concept-based interpretable model for the diagnosis of choroid neoplasias using multimodal data. Nature Communications. 2025;16(1):3504. [CrossRef]

- Pang W, Ke X, Tsutsui S, Wen B. Integrating Clinical Knowledge into Concept Bottleneck Models. In: Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 15006. Springer, Cham; 2024. p. 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Park S, Mun J, Oh D, Lee N. An Analysis of Concept Bottleneck Models: Measuring, Understanding, and Mitigating the Impact of Noisy Annotations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.16705. 2025 May 22.

- Sam D, Pukdee R, Jeong DP, Byun Y, Kolter JZ. Bayesian Neural Networks with Domain Knowledge Priors. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.13410. 2024 Feb 20.

- Wong A, Otles E, Donnelly JP, et al. External Validation of a Widely Implemented Proprietary Sepsis Prediction Model in Hospitalized Patients. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2021;181(8):1065–1070. [CrossRef]

- Heaven, WD. Google’s medical AI was super accurate in a lab. Real life was a different story. MIT Technology Review. 2020 Apr 27.

- Steyerberg, EW. Chapter 17: Internal and external validation of prediction models. In: Steyerberg EW. Clinical Prediction Models: A Practical Approach to Development, Validation, and Updating. 2nd ed. Available online: www.clinicalpredictionmodels.org/extra-material/chapter-17.

- Ramspek CL, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, van Diepen M. External validation of prognostic models: what, why, how, when and where? Clinical Kidney Journal. 2021;14(1):49–58. [CrossRef]

- Austin PC, van Klaveren D, Vergouwe Y, Nieboer D, Lee DS, Steyerberg EW. Geographic and temporal validity of prediction models: different approaches were useful to examine model performance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2016 Nov;79:76–85. [CrossRef]

- Salwei ME, Carayon P. A Sociotechnical Systems Framework for the Application of Artificial Intelligence in Health Care Delivery. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2022 Dec;16(4):194-206. Epub 2022 May 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rosenthal JT, Beecy A, Sabuncu MR. Rethinking clinical trials for medical AI with dynamic deployments of adaptive systems. NPJ Digital Medicine. 2025 May 6; 8:252. [CrossRef]

- Dolin P, Li W, Dasarathy G, Berisha V. Statistically Valid Post-Deployment Monitoring Should Be Standard for AI-Based Digital Health. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.05701. 2025. arXiv:2506.05701. 2025.

- Zhang, A., Lipton, Z. C., Li, M., & Smola, A. J. (2020). Dive into Deep Learning. Journal of the American College of Radiology, JACR.

- Zadeh, L. A. (1999). Fuzzy sets as a basis for a theory of possibility. Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 100, 9–34.

- Musa, A., Prasad, R. & Hernandez, M. Addressing cross-population domain shift in chest X-ray classification through supervised adversarial domain adaptation. Sci Rep 15, 11383 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Blattmann M, Lindenmeyer A, Franke S, Neumuth T, Schneider D. Implicit versus explicit Bayesian priors for epistemic uncertainty estimation in clinical decision support. PLOS Digit Health. 2025 Jul 29;4(7):e0000801. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cao S, Zhang Z. Deep Hybrid Models for Out-of-Distribution Detection. In: Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2022:4733–4741.

- Bickford Smith F, Kossen J, Trollope E, et al. Rethinking Aleatoric and Epistemic Uncertainty. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML). 2025.

- Angelopoulos AN, Bates S. A Gentle Introduction to Conformal Prediction and Distribution-Free Uncertainty Quantification. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.07511. 2022.

- Olsson H, Kartasalo K, Mulliqi N, Capuccini M, Ruusuvuori P, Samaratunga H, Delahunt B, Lindskog C, Janssen EAM, Blilie A; ISUP Prostate Imagebase Expert Panel; Egevad L, Spjuth O, Eklund M. Estimating diagnostic uncertainty in artificial intelligence assisted pathology using conformal prediction. Nat Commun. 2022 Dec 15;13(1):7761. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sreenivasan, A.P., Vaivade, A., Noui, Y. et al. Conformal prediction enables disease course prediction and allows individualized diagnostic uncertainty in multiple sclerosis. npj Digit. Med. 8, 224 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Fayyad J, Alijani S, Najjaran H, Empirical validation of Conformal Prediction for trustworthy skin lesions classification, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, Volume 253, 2024, 108231, ISSN 0169-2607. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam D, Lu H, Sankaranarayanan S, Guttag J. Test-time augmentation improves efficiency in conformal prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.22764. 2025.

- Kendall A, Gal Y. What uncertainties do we need in Bayesian deep learning for computer vision? Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2017:5574-5584.

- Leibig, C., Allken, V., Ayhan, M.S. et al. Leveraging uncertainty information from deep neural networks for disease detection. Sci Rep 7, 17816 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Hsu YC, Shen Y, Jin H and Kira Z, “Generalized ODIN: Detecting Out-of-Distribution Image Without Learning From Out-of-Distribution Data,” 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 2020, pp. 10948-10957. [CrossRef]

- Liang S, Li Y, Srikant R. Enhancing The Reliability of Out-of-Distribution Image Detection in Neural Networks. In: CVPR 2017;15058–15066.

- Guo C, Pleiss G, Sun Y, Weinberger KQ. On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks. NeurIPS 2017:1321–1330.

- Lee K, Lee K, Lee H, Shin J. A Simple Unified Framework for Detecting Out-of-Distribution Samples and Adversarial Attacks. NeurIPS 2018.

- González C, Gotkowski K, Fuchs M, Bucher A, Dadras A, Fischbach R, Kaltenborn IJ, Mukhopadhyay A. Distance-based detection of out-of-distribution silent failures for Covid-19 lung lesion segmentation. Med Image Anal. 2022 Nov;82:102596. [CrossRef]

- Müller M, Hein M. Mahalanobis++: Improving OOD Detection via Feature Normalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.18032. 2025.

- Lakshminarayanan B, Pritzel A, Blundell C. Simple and Scalable Predictive Uncertainty Estimation Using Deep Ensembles. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2017;30:6405–6416.

- HassanPour Zonoozi, M., Seydi, V. A Survey on Adversarial Domain Adaptation. Neural Process Lett 55, 2429–2469 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Subasri V, Krishnan A, Kore A, et al. Detecting and Remediating Harmful Data Shifts for the Responsible Deployment of Clinical AI Models. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(6):e2513685. [CrossRef]

- Vegt AH, Scott I, Dermawan K, Schnetler RJ, Kalke VR, Lane PJ, Implementation frameworks for end-to-end clinical AI: derivation of the SALIENT framework, Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, Volume 30, Issue 9, September 2023, Pages 1503–1515. [CrossRef]

- Shimgekar SR, Vassef S, Goyal A, Kumar N, Saha K. Agentic AI framework for End-to-End Medical Data Inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.18115. 2025.

- Lavin, A., Gilligan-Lee, C.M., Visnjic, A. et al. Technology readiness levels for machine learning systems. Nat Commun 13, 6039 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Kesselman C, Nguyen TH, Xu BY, Bolo K, Yu K. From Data to Decision: Data-Centric Infrastructure for Reproducible ML in Collaborative eScience. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.16051. 2025.

- Feng, J., Phillips, R.V., Malenica, I. et al. Clinical artificial intelligence quality improvement: towards continual monitoring and updating of AI algorithms in healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 5, 66 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T., Papoutsi, C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med 16, 95 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Topol, E. J. (2019). Deep medicine: how artificial intelligence can make healthcare human again. First edition.

- Mol, A. The Logic of Care: Health and the Problem of Patient Choice. Routledge; 2008.

- Cahalan, S. Brain on Fire: My Month of Madness. Simon & Schuster; 2012.

Table 1.

Advantages, limitations, and references for the feature selection approaches discussed in

Section 3.2.

Table 1.

Advantages, limitations, and references for the feature selection approaches discussed in

Section 3.2.

| Epistemic Challenge |

Approach |

Triad Domain |

Advantages |

Limitations |

References |

| Feature ontology ambiguity |

Structural Causal Models (SCMs) |

Causal AI |

Enables counterfactual inference |

Require fully specified causal and measurement equations for every feature |

Lamsaf 2025,

Gani 2023,

Tikka 2023,

Bareinboim 2016 |

| |

Causal Bayesian Network (CBN) models |

Causal AI |

Allow encoding uncertain or partially known dependencies as probabilistic relationships |

Cannot resolve conceptual vagueness; require well-defined random variables |

Mascaro 2023,

Triantafillou 2021,

Wagan 2024 |

| |

Fuzzy Logic |

Ambiguity Awareness |

Handle conceptual vagueness |

Do not resolve causal/relational ambiguities |

Kempowsky-

Hamon 2015,

Paja 2023,

Saki 2024 |

| Identification problem |

Structural Equation Models (SEMs) |

Causal AI |

Quantify measurement error |

Require all relevant confounders to be measured |

Christ 2014,

Kraus 2024,

Sullivan 2021 |

| |

Proximal Causal Inference (PCI) |

Causal AI |

Resolves causal effects despite unmeasured confounders |

Strict validity conditions for proxies |

Eric 2024,

Liu 2025,

Rakshit 2025 |

Table 2.

Advantages, limitations, and references for the model specification approaches discussed in

Section 4.2.

Table 2.

Advantages, limitations, and references for the model specification approaches discussed in

Section 4.2.

| Epistemic Challenge |

Approach |

Triad Domain |

Advantages |

Limitations |

References |

| Signification problem |

Representation Similarity Analysis (RSA) |

Ambiguity Awareness |

Scalable data collection via simple similarity judgments |

Cannot capture hierarchical relationships |

Ogg 2024 |

| |

Abstraction Alignment |

Ambiguity Awareness |

Models hierarchical medical taxonomies |

Limited clinical validation |

Boggust 2025 |

| |

Contrastive Learning |

Ambiguity Awareness |

Adjusts model representations to match concepts; improves zero-shot accuracy and concept-level explainability |

Sensitivity to false negative concept pairings |

Marjieh 2025,

Huynh 2022,

Zang 2021,

Ghesu 2022,

Nie 2025 |

| Misaligned class ontologies |

Concept Bottleneck Models (CBMs) |

Ambiguity Awareness |

Improves model interpretability |

Labeling burden (concept annotations) |

Koh 2020,

Wu 2025,

Pang 2024,

Park 2024 |

| |

Bayesian models with domain- informed priors |

Causal AI |

Enables probabilistic embeddings of clinical knowledge |

Priors are not generalizable across architectures |

Sam 2024 |

Table 3.

Advantages, limitations, and references for the model validation approaches discussed in

Section 5.2.

Table 3.

Advantages, limitations, and references for the model validation approaches discussed in

Section 5.2.

| Epistemic Challenge |

Approach |

Triad Domain |

Advantages |

Limitations |

References |

| Misaligned uncertainty semantics |

Conformal Prediction |

Uncertainty Quantification |

Creates statistical coverage guarantees |

Prediction sets are sometimes too large to be clinically helpful |

Angelopoulos 2022,

Olsson 2022.

Sreenivasan 2025,

Fayyad 2024,

Shanmugam 2025 |

| |

Bayesian Neural Networks (BNNs) |

Uncertainty Quantification |

Explicitly represent both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty |

Require representative datasets and well-chosen priors |

Kendall 2017,

Liebig 2017 |

| Domain-shift vulnerability |

ODIN/G-ODIN |

Uncertainty Quantification |

Lightweight, versatile baseline |

Overconfident under high epistemic uncertainty |

Hsu 2020,

Liang 2017,

Guo 2017 |

| |

Mahalanobis Distance-Based OOD Methods |

Uncertainty Quantification |

Directly examine internal feature embeddings |

Strict assumptions (Gaussian, well-clustered features) |

Lee 2018,

González 2022,

Müller 2025, |

| |

Deep Ensemble OOD Methods |

Uncertainty Quantification |

Highest accuracy |

High computational cost |

Lakshminarayanan 2017 |

| |

Adversarial Domain Adaptation |

Ambiguity Awareness |

Does not require labelled data from target distribution |

Follows linear, rather than dynamic, paradigm |

HassanPour 2023,

Mus 2025 |

| |

Drift-triggered Continual Learning |

Uncertainty Quantification |

Follows dynamic paradigm |

Catastrophic forgetting |

Subasri 2025 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).