Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

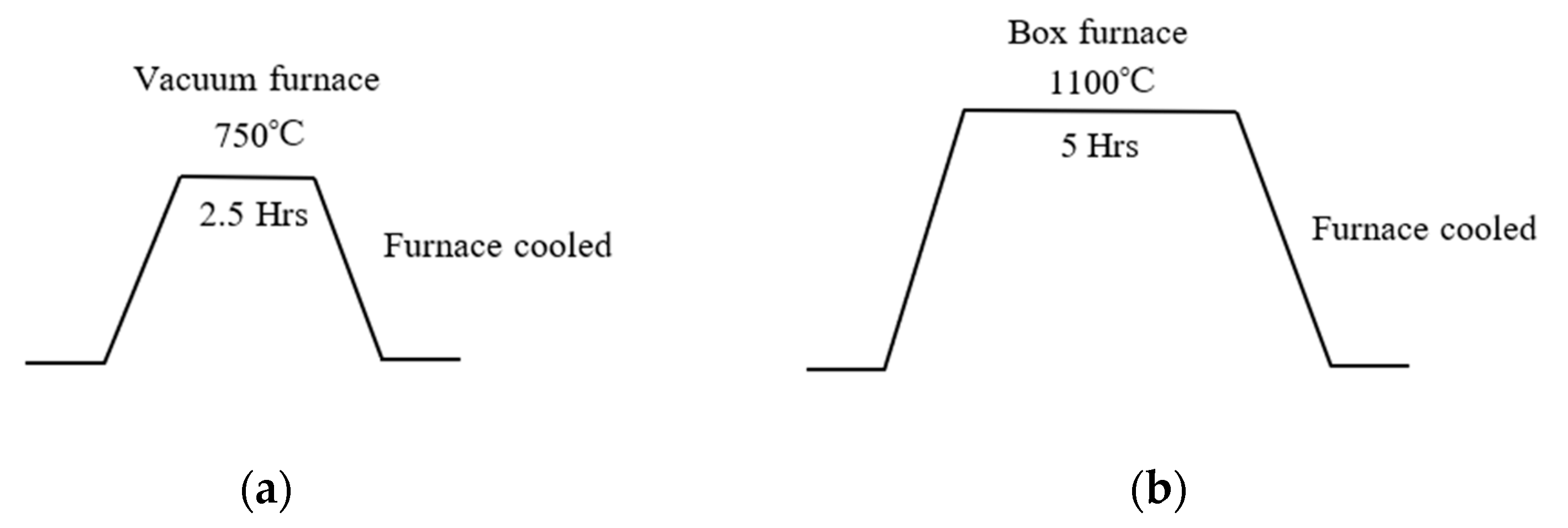

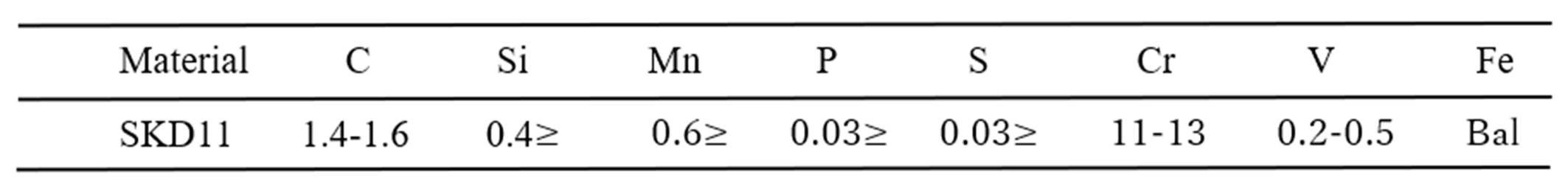

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

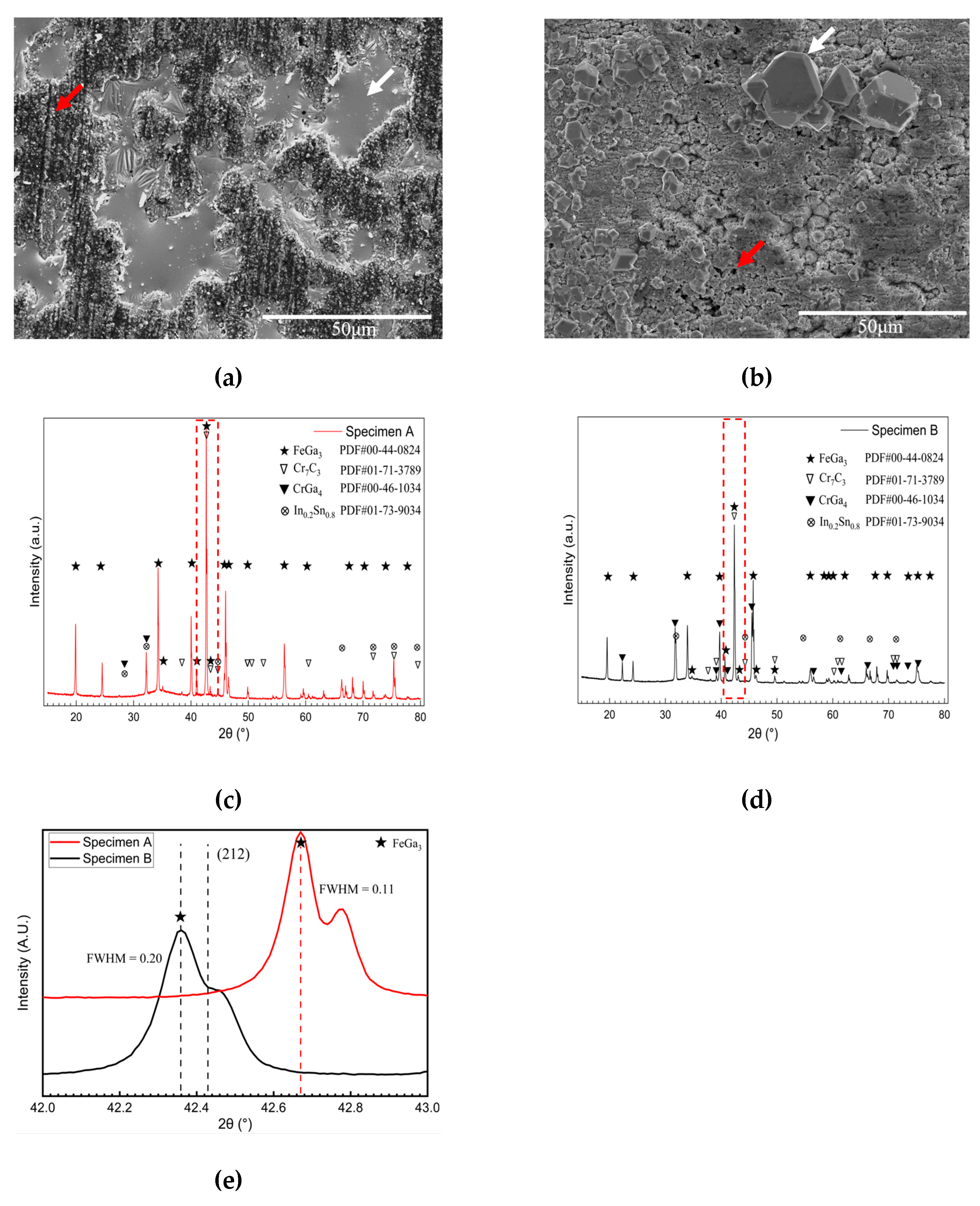

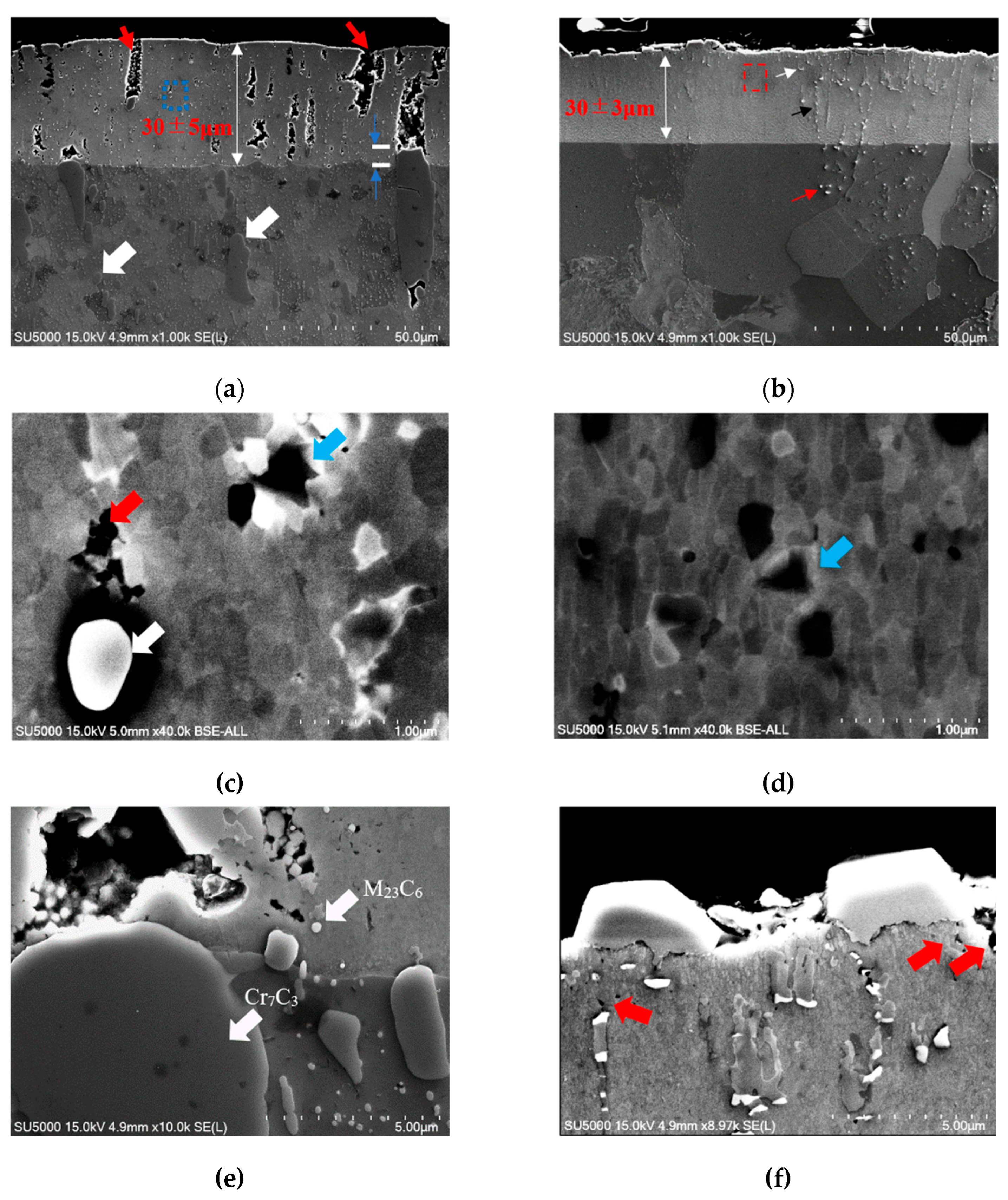

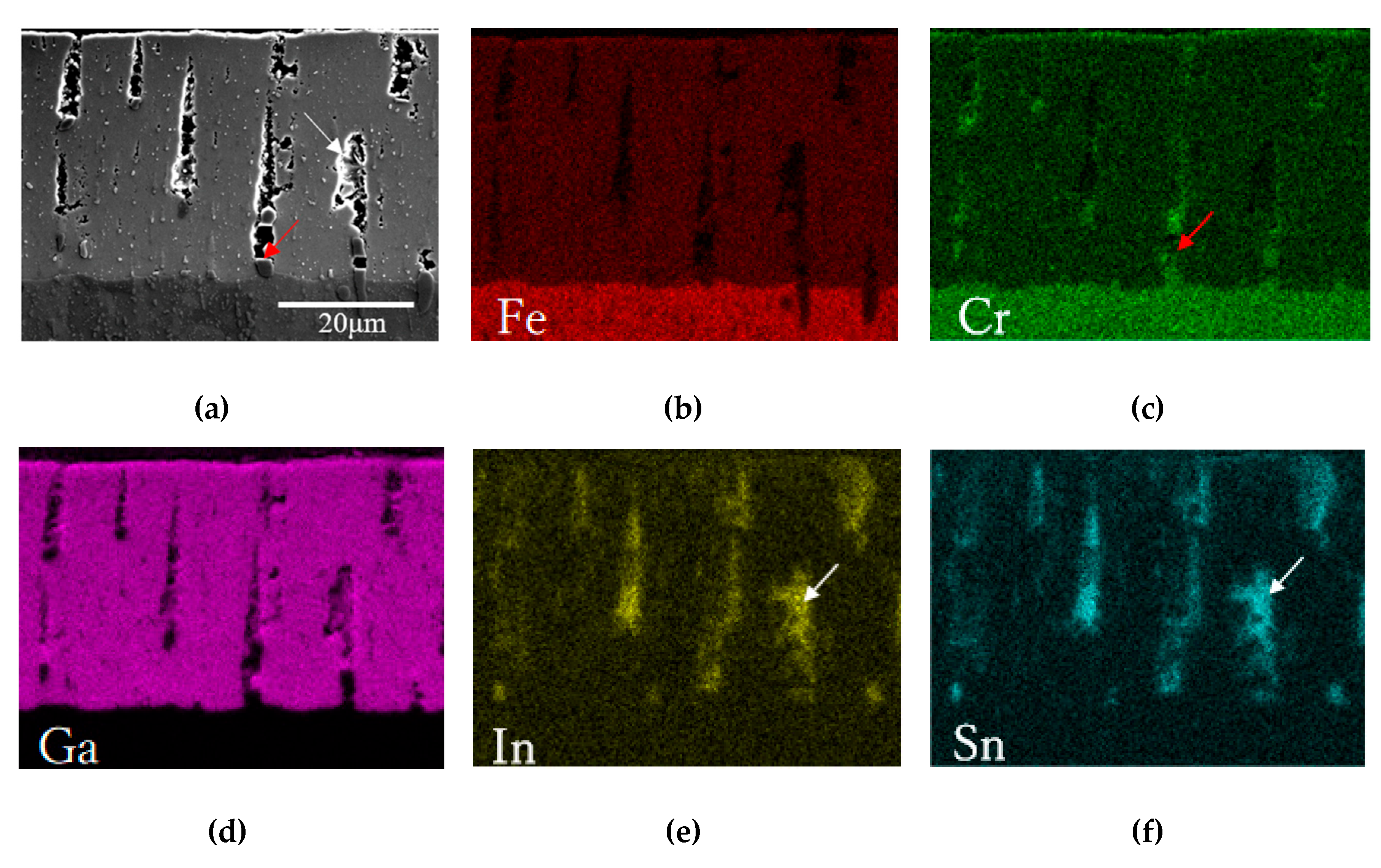

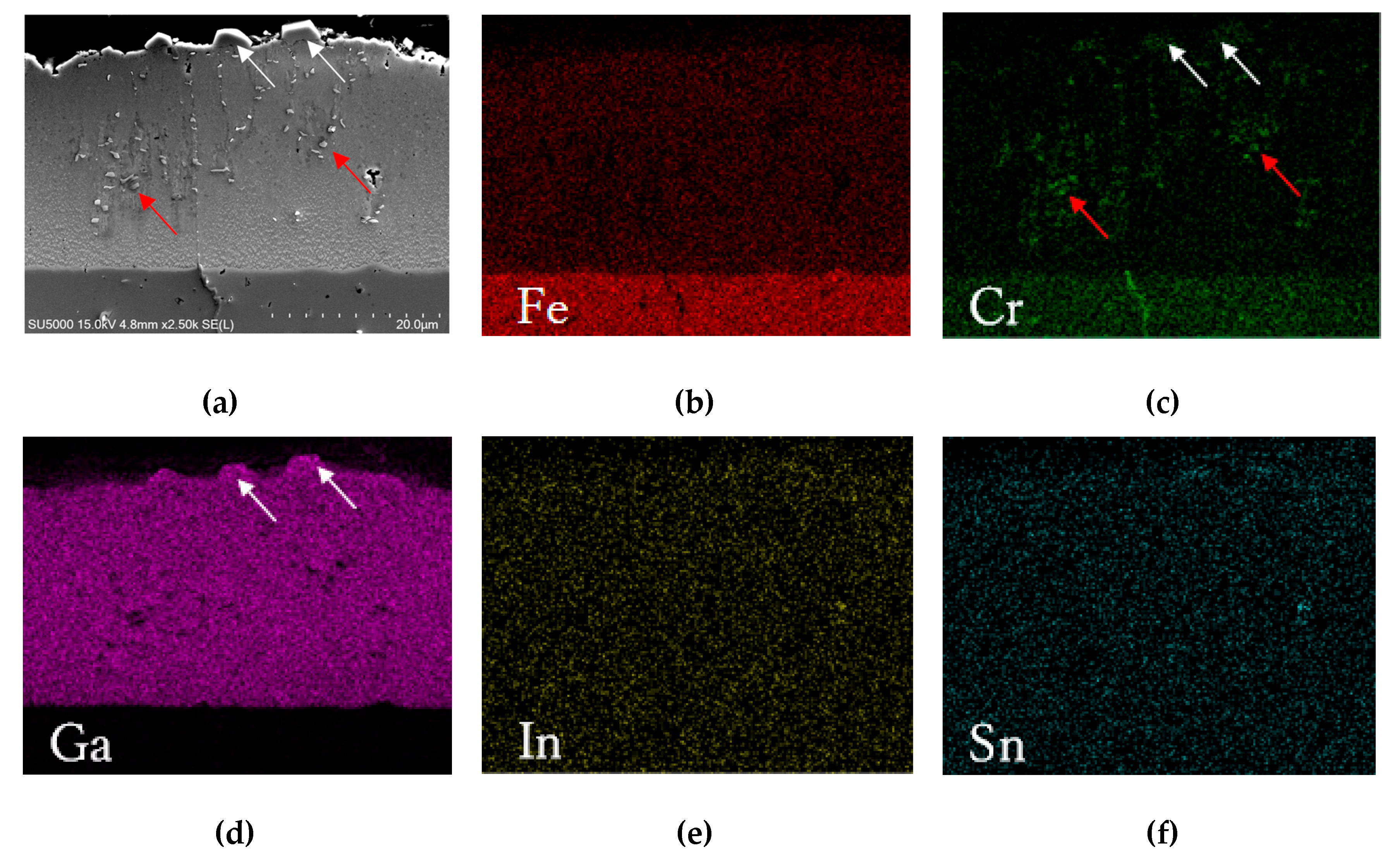

3.1. Microstructure

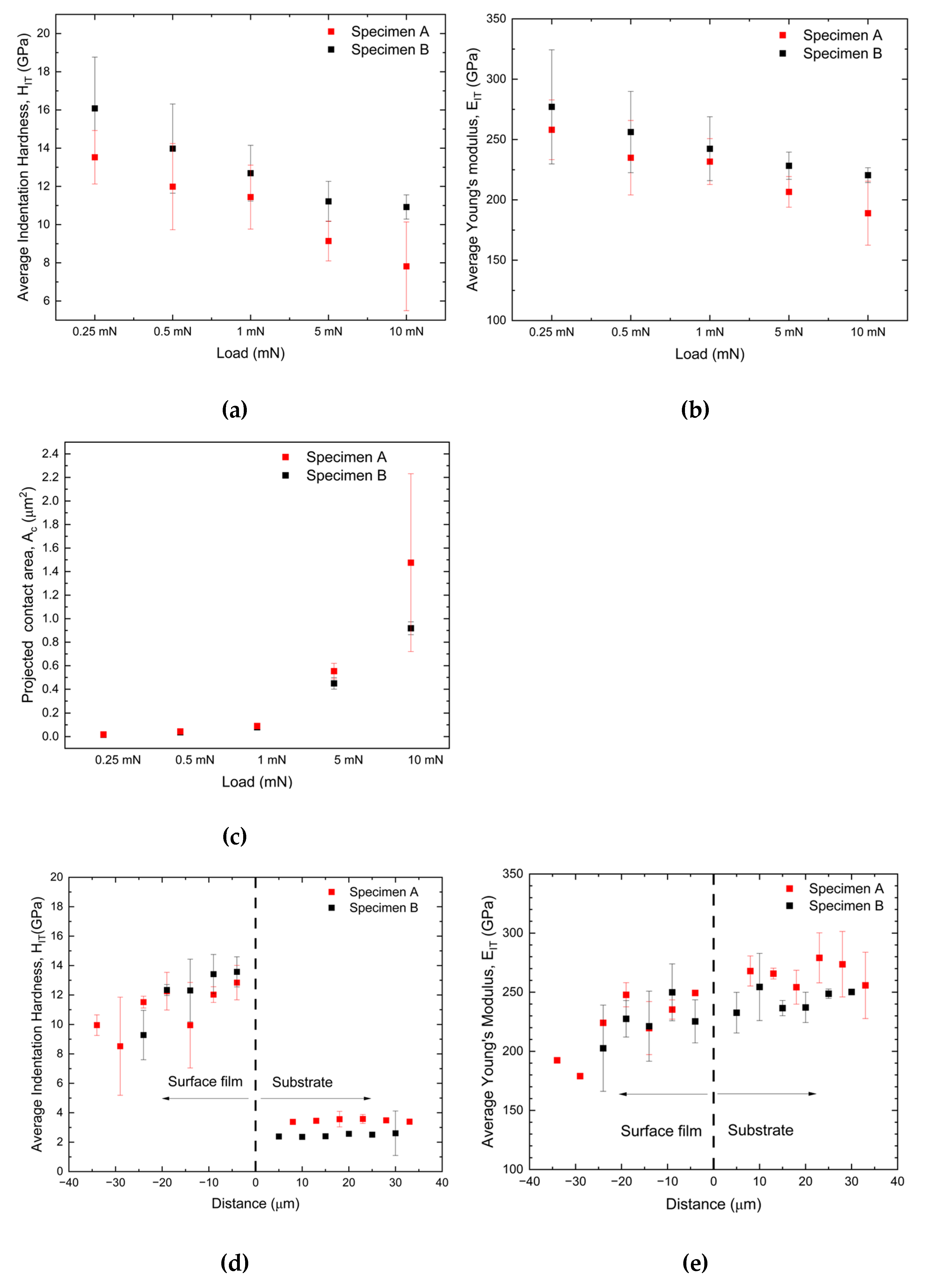

3.2. Mechanical Test

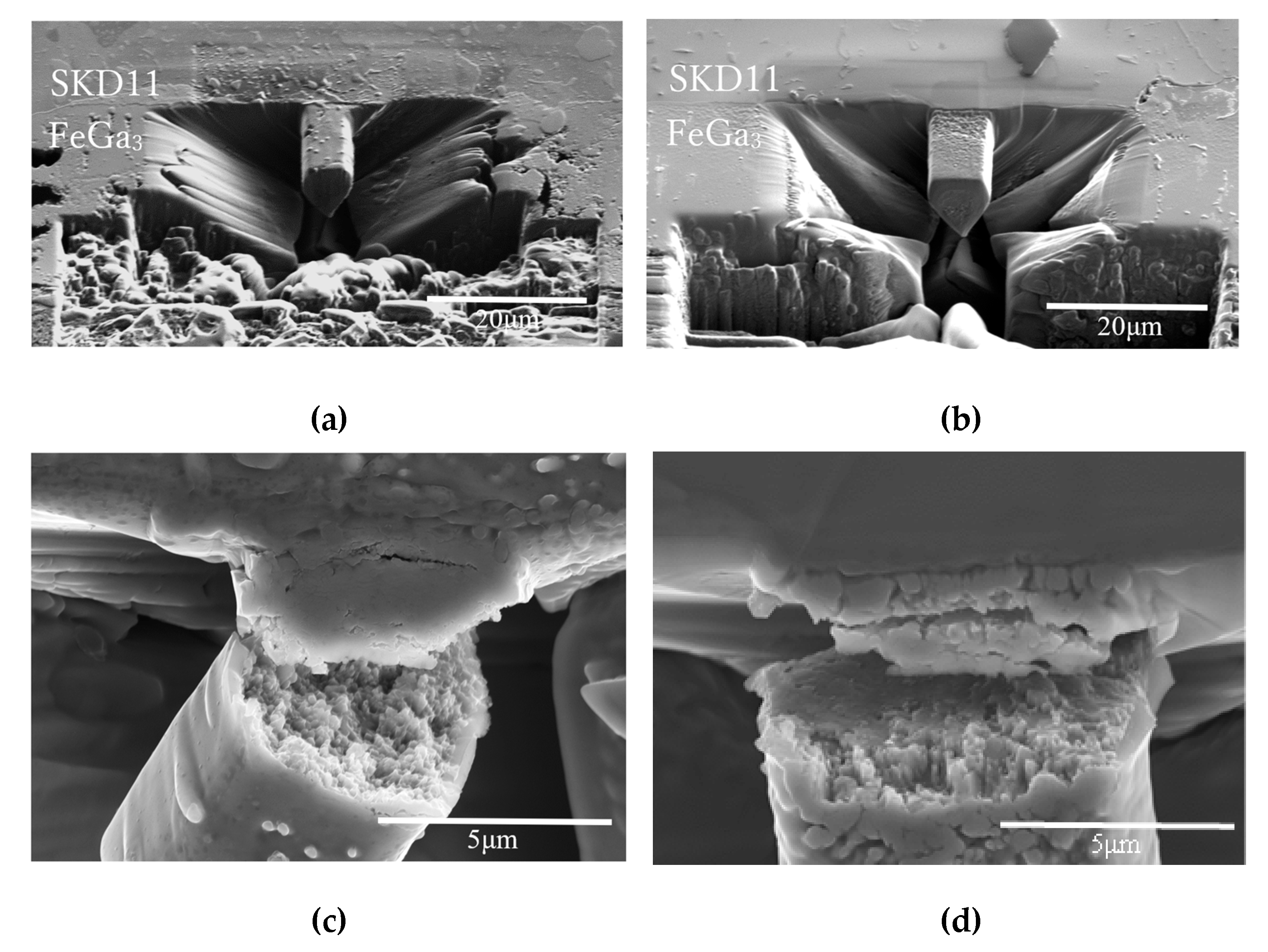

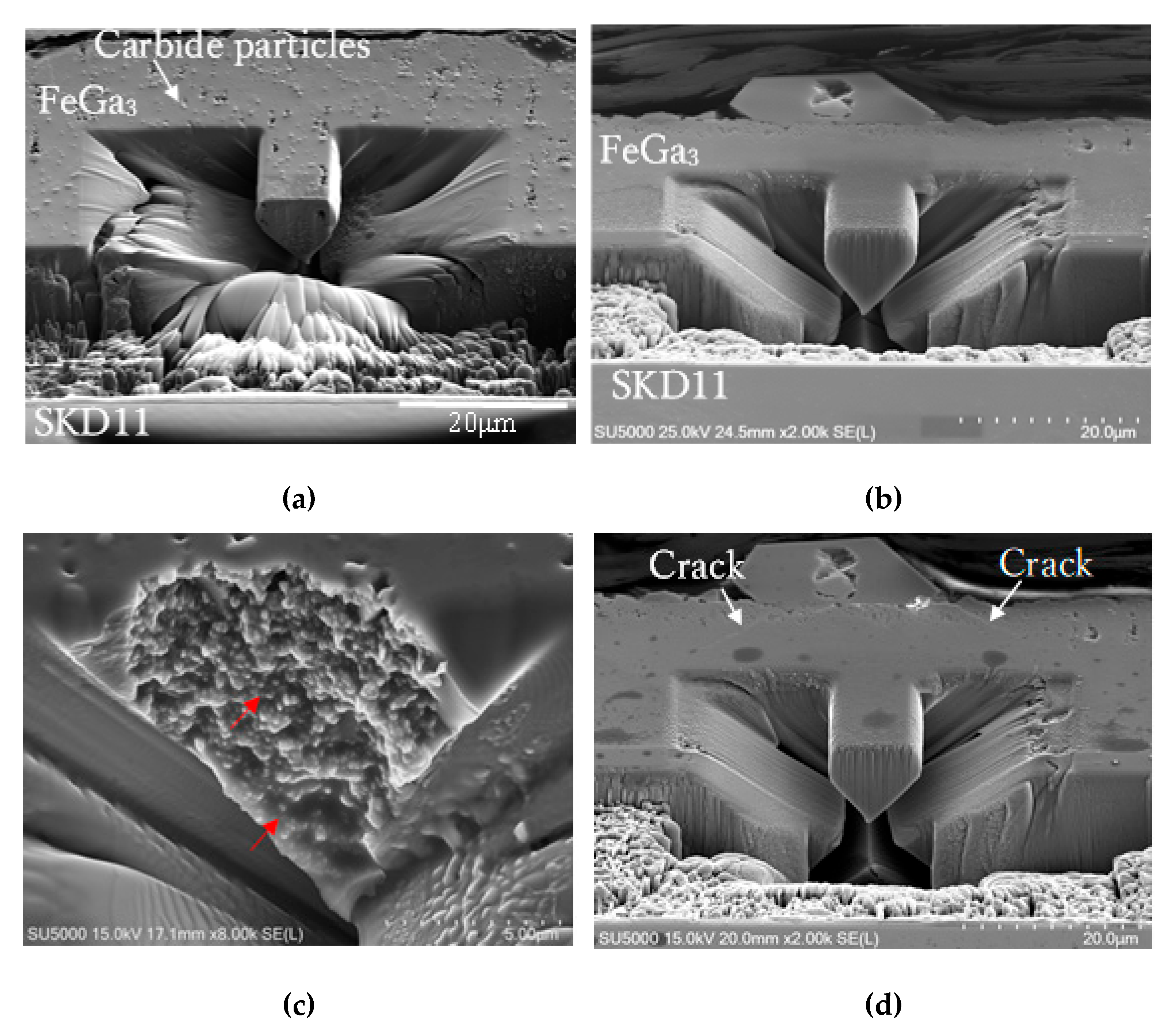

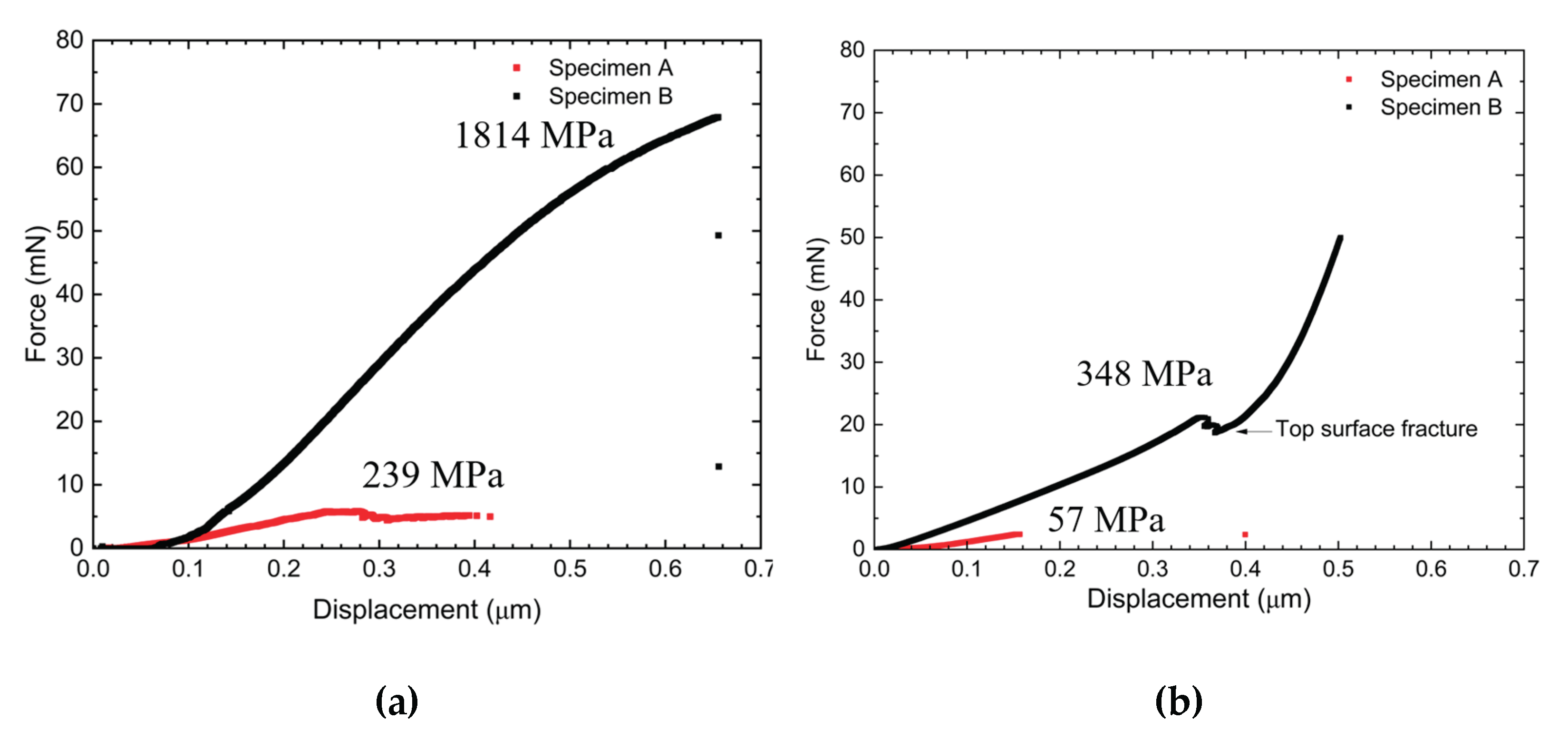

3.3. Microcantilever Test

4. Discussion

4.1. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties

4.2. Microcantilever Beam Shearing Test

5. Conclusions

- 1)

- The FeGa3 surface film on an annealed substrate exhibits high porosity due to the inability of the reaction between the gallium-based liquid metal and chromium carbide. On the other hand, the FeGa3 on decarburised SKD11 substrate showed less porosity due to the dissolution of the chromium carbide precipitates into the SKD11 matrix.

- 2)

- FeGa3 surface film on both substrates shows the nanohardness of approximately 11 – 13 GPa.

- 3)

- The decarburisation process significantly improved the shear strength of the compound layer. The compound layer on the decarburised substrate showed more than six times higher shear strength than that on the annealed substrate, indicating enhanced potential for practical applications under high mechanical stresses.

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Handschuh-Wang, S.; Stadler, F.J.; Zhou, X. Critical Review on the Physical Properties of Gallium-Based Liquid Metals and Selected Pathways for Their Alteration. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 20113–20142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cheng, J.; Wang, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, W. A Protective FeGa3 film on the steel surface prepared by in-situ hot-reaction with liquid metal. Mater. Lett. 2018, 228, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behling, R. Modern Diagnostic X-Ray Sources; CRC Press: Second edition. | Boca Raton : CRC Press, 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J.; Yu, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, S.; Zhu, S.; Ye, Q.; Yang, J.; Liu, W. Ga-based liquid metal with good self-lubricity and high load-carrying capacity. Tribol. Int. 2019, 129, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.C. Corrosion of Materials by Liquid Metals. In Liquid-Metals Handbook; 1952; pp. 144–183 ISBN 1251006011111.

- Barbier, F.; Blanc, J. Corrosion of martensitic and austenitic steels in liquid gallium Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1557/JMR.1999.0099. [CrossRef]

- Dasarathy, C. ; W. Hume-Rothery The System Iron-Gallium. 1965, 286, 141–157. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, D.H.; Johnson, R.L. Gallium-Rich Films as Boundary Lubricants in Air and in Vacuum to 10 −9 mm Hg. A S L E Trans. 1963, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luebbers, P.R.; Michaud, W.F.; Chopra, O.K. Compatibility of ITER candidate structural materials with static gallium; Argonne, IL, 1993. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Mao, H.; Ning, H.; Deng, Z.; Wu, X. Friction Behavior and Self-Lubricating Mechanism of SLD-MAGIC Cold Worked Die Steel during Different Wear Conditions. Metals (Basel). 2023, 13, 809–10.3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindersson, S. Reactivity of Galinstan with Specific Transition Metal Carbides, Uppsala Universitet: Uppsala, Sweden, 2014.

- Geddis, P.; Wu, L.; McDonald, A.; Chen, S.; Clements, B. Effect of static liquid Galinstan on common metals and non-metals at temperatures up to 200 °C. Can. J. Chem. 2020, 98, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H.; Kim, J.J.; Jung, J.A.; Choi, K.J.; Bang, I.C.; Kim, J.H. A study on corrosion behavior of austenitic stainless steel in liquid metals at high temperature. J. Nucl. Mater. 2012, 422, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.A.; Lim, M.J. A relationship of porosity and mechanical properties of spark plasma sintered scandia stabilized zirconia thermal barrier coating. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101263–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Aswal, D.K. Recent Advances in Thin Films; Kumar, S. , Aswal, D.K., Eds.; Materials Horizons: From Nature to Nanomaterials; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2020; ISBN 978-981-15-6115-3. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, A.; Holmberg, K.; Franklin, S. A methodology for coating selection. Tribol. Ser. 1993, 25, 429–439. [Google Scholar]

- Kiryukhantsev-Korneev, P.; Sytchenko, A.; Pogozhev, Y.; Vorotilo, S.; Orekhov, A.; Loginov, P.; Levashov, E. Structure and properties of zr-mo-si-b-(N) hard coatings obtained by d.c. magnetron sputtering of zrb2-mosi2 target. Materials (Basel). 2021, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, H.; He, Z.; He, B.; Tang, Z.; Fang, X.; Cai, Z.; Cao, Z.; An, L. Effect of Metallic Coatings on the Wear Performance and Mechanism of 30CrMnSiNi2A Steel. Materials (Basel). 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yang, L.; Tian, W.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Z. Spontaneous Ga whisker formation on FeGa3. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2018, 28, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Maio, D.; Roberts, S.G. Measuring fracture toughness of coatings using focused-ion-beam-machined microbeams. J. Mater. Res. 2005, 20, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrick Madaraka Mwema; Jen, T. -C.; Zhu, L. Thin Film Coatings: Properties, Deposition, and Applications; CRC Press, 2022; ISBN 9781032065106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonczy, S.T.; Randall, N. An ASTM standard for quantitative scratch adhesion testing of thin, hard ceramic coatings. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2005, 2, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Cripps, A.C. Nanoindentation; Mechanical Engineering Series; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-9871-2. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Tatami, J.; Iijima, M. Measurement of mechanical properties of BaTiO3 layer in multi-layered ceramic capacitor using a microcantilever beam specimen. J. Ceram. Soc. Japan 2019, 127, 335–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Takenaka, M.; Yamasaki, S.; Morikawa, T. Micromechanical testing for quantitative characterization of apparent slip system: Extinction of persistence of slip in carbon bearing Fe-3% Si. Scr. Mater. 2023, 232, 115473–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, N.S.; Luo, X. FIB Micro-/Nano-fabrication; Second Edi.; Yi Qin, 2015; ISBN 9780323312677. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Okajo, S.; Yamasaki, S.; Morikawa, T. Persistent slip observed in TiZrNbHfTa: A body-centered high-entropy cubic alloy. Scr. Mater. 2021, 200, 113895–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, T.; Baiz, S.; Bataillou, L.; Klochko, A. Liquid metal embrittlement of molybdenum by the eutectic gallium-indium-tin alloy. Materialia 2022, 25, 101523–10.1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherrer, P. Bestimmung der Grösse und der inneren Struktur von Kolloidteilchen mittels Röntgenstrahlen. Göttinger Nachrichten Gesell 1918, 2, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.; Chiang, Y.W.; Santos, R.M. X-Ray Diffraction Techniques for Mineral Characterization: A Review for Engineers of the Fundamentals, Applications, and Research Directions. Minerals 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.N.; Xu, B.S.; Wang, H.D.; Wang, C.B. Measurement of residual stresses using nanoindentation method. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2015, 40, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.-H.; Xu, H.-X.; Ye, X.-X.; Leng, B.; Qiu, H.-X.; Zhou, X.-T. Corrosion behavior of pure metals (Ni and Ti) and alloys (316H SS and GH3535) in liquid GaInSn. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2024, 35, 54–10.1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Yuan, G.; Tan, J.; Chang, S.; Tu, S. The Influence of Crystallographic Orientation and Grain Boundary on Nanoindentation Behavior of Inconel 718 Superalloy Based on Crystal Plasticity Theory. Chinese J. Mech. Eng. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillonneau, G.; Kermouche, G.; Bergheau, J.M.; Loubet, J.L. A new method to determine the true projected contact area using nanoindentation testing. Comptes Rendus - Mec. 2015, 343, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Cripps, A.C. Nanoindentation Testing. In Springer; Mechanical Engineering Series; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4419-9871-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Ong, S.P.; Hautier, G.; Chen, W.; Richards, W.D.; Dacek, S.; Cholia, S.; Gunter, D.; Skinner, D.; Ceder, G.; et al. Commentary: The materials project: A materials genome approach to accelerating materials innovation. APL Mater. 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhns, O.T. Advanced Mechanics of Solids; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2003; ISBN 978-3-642-07850-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternero, F.; Rosa, L.G.; Urban, P.; Montes, J.M.; Cuevas, F.G. Influence of the total porosity on the properties of sintered materials—a review. Metals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).