Introduction

Throughout history, female artists have received significantly less recognition for their contributions compared to their male counterparts, a disparity that art museums and cultural institutions must confront. The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York has long been considered a pioneer in shaping the direction of modern and contemporary art, as it has influenced public opinion, academic research, and the art market since its founding in 1929. However, MoMa has faced growing criticism for the gender bias within its acquisitions, exhibitions, and retrospectives. Research indicates that only 15% of artworks purchased by MoMA between 1929 and 2020 were created by women artists (Museum of Modern Art, 2021). This statistic points to persistent institutional bias, reflective of a broader social framework that has historically marginalized women in the arts. Despite increasing global advocacy for gender equality, cultural institutions have been slow to respond and adjust their practices. The continued underrepresentation of women in MoMA’s permanent collection signals that these disparities are not incidental but systemic, actively contributing to the marginalization of women in the art world.

The underrepresentation of women within MoMA’s collection cannot be explained solely by narratives of historical exclusion. Curatorial decisions continue to be shaped by patriarchal norms and women face unequal access to professional networks and resources. This ongoing cycle of exclusion is further sustained by the lack of diversity among decision-makers—museum directors, curators, and trustees—making structural change especially challenging. Understanding the depth of these barriers requires a closer look at the institutional practices that have shaped them.

As such, this study examines gender disparities within MoMA’s collection by exploring their historical origins and evaluating their ongoing influence. It seeks to identify patterns of marginalization by tracing the evolution of representation over nearly a century, emphasizing key moments when gender inequities were either addressed or overlooked. Two guiding questions shape this research 1): How has the representation of female artists at MoMA evolved over time? 2) What structural and institutional factors have contributed to female marginalization in the creation, curation, and preservation of modern and contemporary art?

In recent years, MoMA has taken steps to confront these disparities by curating exhibitions centered on women artists, revising acquisition strategies to enhance diversity, and partnering with organizations that support women in the arts. For example, in 2010, MoMA presented Pictures by Women, an exhibition showcasing a range of photographs created by women artists and hosted a symposium on the role of feminist politics within art institutions (Museum of Modern Art, 2010; Museum of Modern Art, n.d.). While these initiatives signal a broader institutional shift toward inclusivity, questions remain about whether such efforts reflect a sustained commitment to structural change or merely serve as symbolic gestures of inclusion.

Responding to the persistent challenges faced by women artists, this analysis highlights the difficulty of achieving gender equality within modern art institutions, suggesting that meaningful change requires a fundamental re-evaluation of how value is assigned to artistic production and how gender equity is recognized within the canon. Study findings also highlight collaboration as a crucial strategy for addressing systemic inequalities. Ultimately, this research contributes to broader discussions on representation, institutional power, and social justice in the arts—dialogues that are vital to building a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable cultural legacy for future generations.

Previous Work

The Historical Roots of Gender Bias

Feminist scholars have increasingly illuminated how art history’s narratives have systematically excluded women, both as creators and as subjects of serious study. Linda Nochlin (1971), for example, has dismantled the myth of male artistic genius by redirecting attention to the structural barriers that have historically limited women’s artistic careers—such as lack of access to formal education, restricted professional opportunities, and confining domestic expectations. Similarly, scholars like Griselda Pollock (1988) have critiqued the masculinist frameworks that have shaped art historical discourse and institutional practices. According to Pollock, museums are not neutral spaces but are rather active agents in upholding patriarchal values because they curate and promote pieces that privilege male-centered ideologies and aesthetics. This body of feminist scholarship highlights how both historical and institutional practices have led to the marginalization of women’s contributions within the art world.

More recent scholarship and activism have shifted from questions of visibility and inclusion to interrogating the institutional and cultural frameworks that continue to position women artists as peripheral creators. Groups like the Guerrilla Girls have played a crucial role in exposing and challenging gender inequities in the art world. Since their founding in 1985, the Guerrilla Girls have used humor, visual satire, and statistical evidence to confront the exclusion of women from major institutions such as MoMA. Their iconic poster—“Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?”—sharply criticized how women are often objectified rather than recognized as artists, sparking widespread discussion within the art community (Getty Research Institute, n.d.). Parallel to these activist efforts, scholars such as Whitney Chadwick (2007) have offered global perspectives on how female artists have historically been marginalized through institutional indifference and cultural narratives that prioritize male creators. Chadwick emphasizes that women’s work is often positioned in opposition to mainstream art rather than being fully integrated into it. For example, even when women are included in exhibitions, their work is often framed within limiting narratives—such as being categorized solely under “women’s art” rather than being integrated into the broader canon. This form of symbolic inclusion often reinforces marginalization rather than challenging it. Together, these scholarly and activist perspectives reinforce the understanding that institutions like MoMA have not only favored male artists but have also relegated women to secondary status, both in representation and in recognition. As these critiques demonstrate, meaningful inclusion in the art world requires more than visibility – it require restructuring institutional priorities and re-evaluating how cultural legitimacy is assigned in the art world.

Contemporary Trends within Art Institutions

While museums have acted to improve gender inequality within their collections, progress remains slow and inconsistent. In 2022, The Art Newspaper published a major report revealing that only 11 percent of artworks acquired by top U.S. museums were by female artists (McGivern 2022). That such a gap persists—even amid widespread calls for diversity and inclusion—establishes the scale of female artists’ marginalization. The study also noted that exhibitions displaying the work of female artists appeared significantly less often than those featuring male artists, suggesting that acquisition efforts alone are insufficient to address systemic inequities. Even when museums work to diversify their collections, critics have pointed out that many works end up in side galleries, not the main spaces—suggesting these efforts may be tokenistic. In his article in New York Magazine, Jerry Saltz (2007) acknowledged the intentions behind these more inclusive practices but emphasized that lasting change requires an ongoing institutional readiness to address such disparities, rather than one-off initiatives. To ensure meaningful representation, museums must commit to integrating the works of female artists into their acquisition and curatorial practices for the long-term.

MoMA’s recent acquisitions feature works by renowned female artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Marlene Dumas, and Yayoi Kusama. Although these additions signify progress, they fall short of addressing the underlying structural inequalities within the art world. The continued underrepresentation of contemporary female artists raises critical concerns about whether current institutional practices can adequately support the development of future generations of women creators.

Intersectional Gaps

While gender inequality remains a critical lens through which to examine disparities in art institutions, it is also essential to account for intersecting factors such as race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, which often exacerbate these inequities. Black, Latina, and multiracial women artists face heightened marginalization within dominant art narratives, with their contributions frequently overlooked or excluded from mainstream recognition. Scholars such as bell hooks and Audre Lorde have long advocated for an intersectional framework—one that understands cultural contexts as shaped by overlapping and interdependent systems of oppression and power.

MoMA’s collections have historically featured relatively few works by women artists of color. A notable exception occurred in 2020 with the inclusion of Faith Ringgold’s American People Series into the museum’s permanent collection, a significant moment for the recognition of Black women’s art (Shoard 2024). While this acquisition was widely seen as a positive step, it was accompanied by notable restrictions regarding access to and display of the collection. Moreover, the contributions of pioneering Black women artists such as Alma Thomas, Howardena Pindell, and Carrie Mae Weems have received minimal attention within mainstream curatorial narratives. Similarly, Latina artists like Carmen Herrera and Beatriz González have only recently begun to attain the recognition long overdue to them, revealing the need for proactive efforts to account for historical exclusions.

That said, issues of representation in museums go beyond curatorial decisions and inclusion – they are also deeply shaped by the interpretive frameworks that define how art is understood and valued. Scholars such as Aruna D’Souza (2018) argue that institutions often instrumentalize artists of color, framing their work primarily through the lens of identity politics rather than engaging with the works’ aesthetic and conceptual significance. This approach risks reducing complex artistic practices to simplistic narratives of exploitation and resistance, further marginalizing underrepresented voices. Without a shift in how art framed and contextualized – which cannot be achieved through superficial metrics or tokenistic inclusion – institutions risk reinforcing the very exclusions they claim to address.

Methodology and Research Design

Data Collection

Data for this study were drawn from MoMA’s online collection database (1929–2023), which includes metadata on artist gender, acquisition year, medium, and exhibition history (MoMA Collection, 2025). The analysis focused on two datasets: artworks.csv file (130,262 entries across 21 variables) and the artists.csv file (15,091 entries across 6 variables). These datasets were examined to assess patterns in gender representation within the museum’s collection. While the dataset is extensive, it presents several limitations: it lacks metadata for non-binary and transgender artists, and the data reflects historical biases such as the misgendering, omission, or marginalization of women artists.

The Model

The two datasets—

artworks.csv and

artists.csv—served as inputs to the model.

Figure 1 presents a diagram outlining the workflow used for trend prediction.

To forecast trends in gender representation, both linear and polynomial regression models were employed. Regression analysis was conducted to capture varying data patterns over time. Notably, representation of female artists exhibited an accelerating trend in later years that linear regression failed to capture fully. In contrast, polynomial regression more accurately reflected this acceleration, providing a better fit for modeling the increase in the representation of female artists within the dataset. Overall, the predictive analysis reveals a steady upward trend in the inclusion of female artists, with polynomial regression offering enhanced modeling, particularly in later years.

Results and Discussion

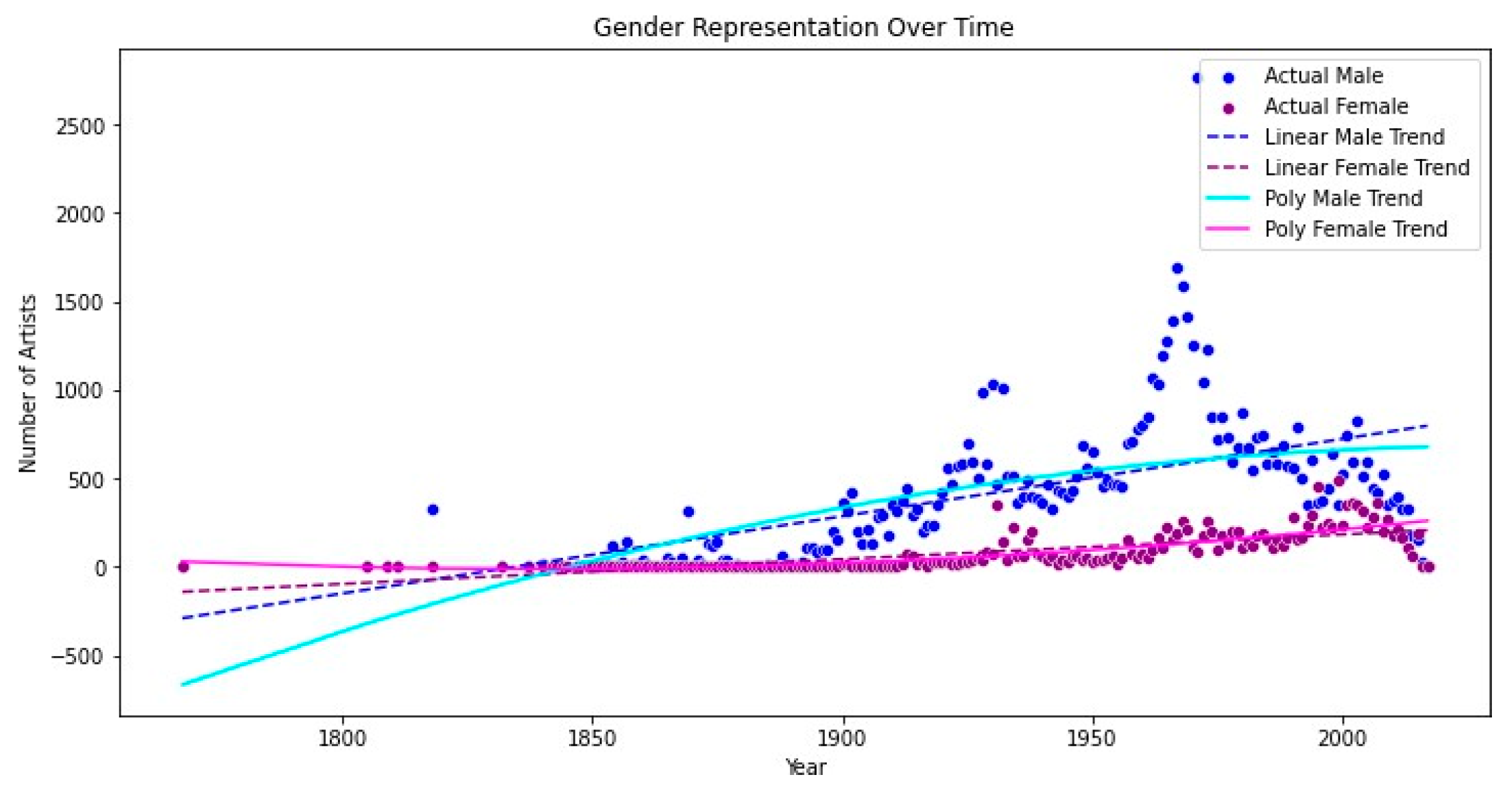

To evaluate patterns of inclusion and exclusion within MoMA’s collection, this study employed regression analysis to identify trends in gender representation over time, as seen in

Figure 2. Additionally, intersectional frameworks were applied to explore how race, class, and gender dynamics intersect to shape representational disparities in institutional art practices, aligning with Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1989) foundational argument that systems of oppression do not act independently, but rather overlap to marginalize some identities more than others.

Patterns in museum acquisitions reflect a long-standing prioritization of the work of male artists. Acquisition of pieces by male artists remained consistently higher throughout the time period of the study. As

Figure 2 indicates, however, there were several fluctuations, particularly after 1950, with the highest data points nearing 2,500 male artists.

Figure 2 also highlights a pronounced increase in representation during the late 20th century, accompanied by a wider dispersion of data points. Because scattered or dispersed data points signify greater variability within the dataset, this graph reflects greater variability in male representation. In contrast, there is a steady increase in the representation of female artists over time, with less fluctuation and more consistency. Nevertheless, the data demonstrates that male artists have continued to receive more institutional attention than their female counterparts, despite the rise in the representation of female artists within MoMA’s collection.

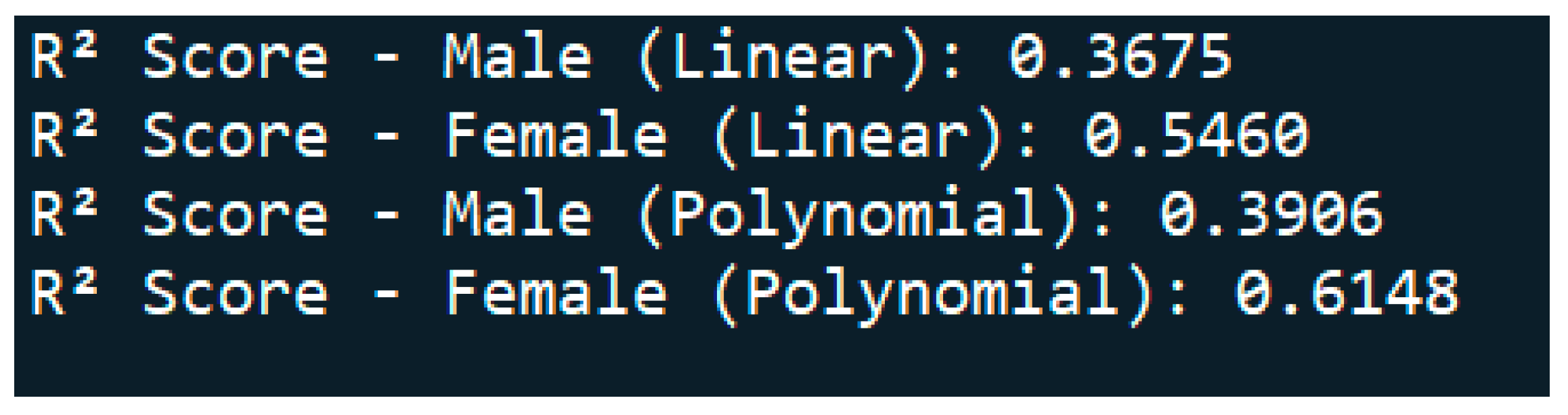

While the linear regression indicates a general upward trend, the polynomial regression provides a better fit (R

2 = 0.3906), suggesting underlying non-linear growth (

Figure 3).

Interestingly, the linear regression model for female artists yields a higher R² value than for males. The polynomial regression offers an improved fit for both genders, with the female trend line achieving the strongest fit (R² = 0.6148), compared to the male trend line (R² = 0.3906), emphasizing the consistent increase in the representation of female artists among MoMA’s collections up until 2023.

These results suggest that the gender gap was relatively narrow prior to 1900. Beginning in the mid-20th century, however, this gap began to widen. Following the 1950s, the inclusion of male artists surged dramatically, while female representation remained comparatively modest. This period reflects the height of gender disparity within the dataset, despite substantial fluctuations in male representation. Overall, the data illustrates how gender representation in museum collections has been both uneven and consistent with historical biases, particularly in the post-1950 era.

Qualitative Findings

Further analysis of MoMA’s collection reveals consistent patterns of gender imbalance across various measures. Visual data illustrates disparities not only in the overall distribution of male and female artists, but also among specific nationalities, artistic disciplines, and mediums. These disparities point to larger historical biases that have influenced whose work is collected, exhibited, and celebrated.

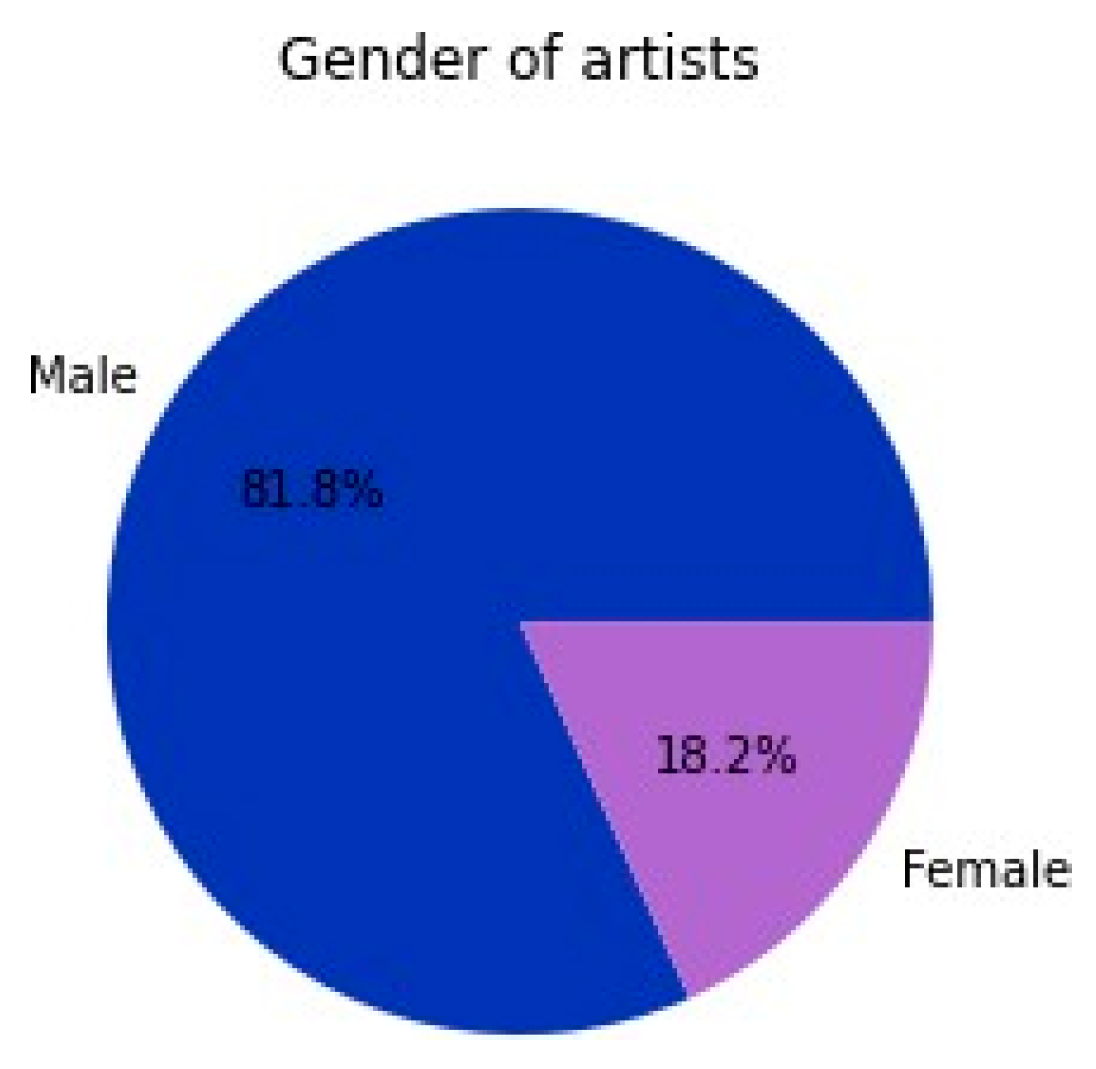

Gender disparity is immediately visible in the general makeup of the collection. The pie chart provided in

Figure 4 displays the gender breakdown of artists in MoMA’s collection, revealing that 81.8% are male and only 18.2% are female. This gap reflects a significant gender imbalance, one shaped by longstanding historical and institutional biases in the art world.

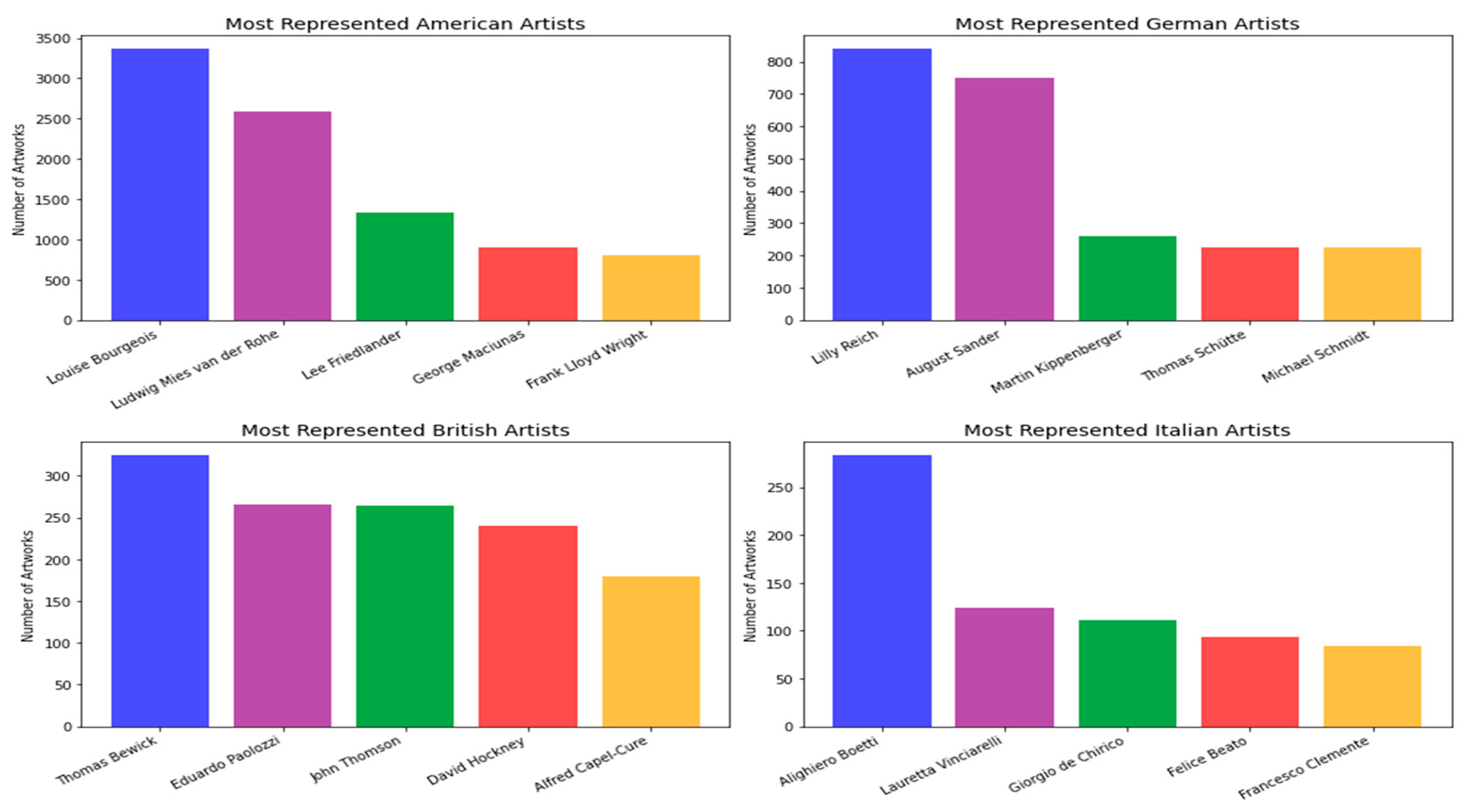

Gender patterns also persist across nationalities. The bar chart shown in

Figure 5 indicates artist representation by nationality, with American artists appearing most frequently. Louise Bourgeois has the highest representation, followed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lee Friedlander. A similar pattern of male predominance emerges across British, German, and Italian artist categories.

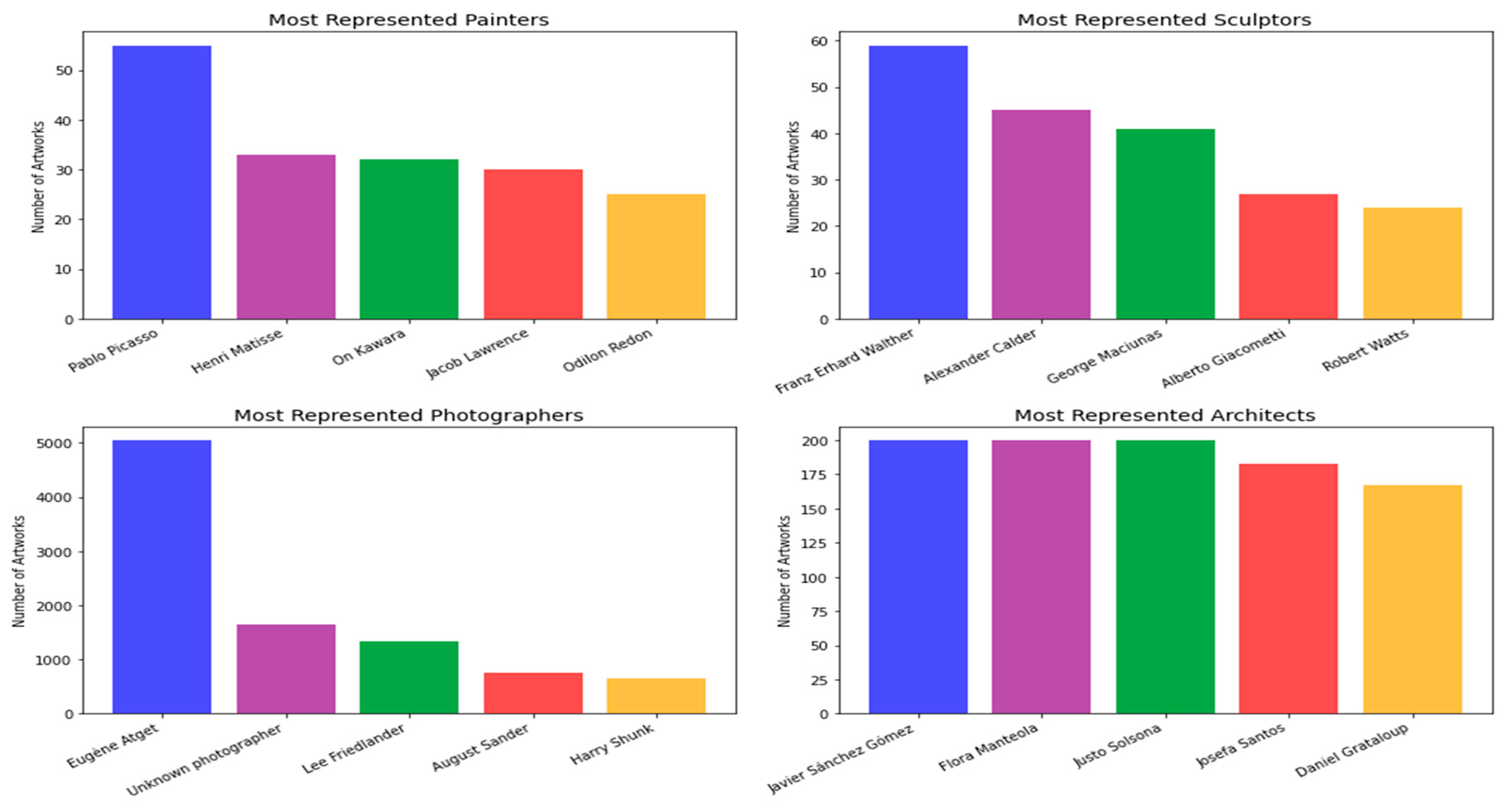

Inequities in gender representation become even more apparent when broken down by artistic discipline.

Figure 6 shows male dominance across various artistic disciplines, including painting, sculpture, architecture, and photography. Photography accounts for the highest number of works but is top representation is exclusively male. In architecture, while male representation is somewhat more distributed, there are no female artists among the most represented. Painting, traditionally regarded as a prestigious medium, reveals an extreme gender imbalance, with Pablo Picasso as the leading figure. Sculpture similarly follows a pattern of male overrepresentation.

Representation among the most collected artists offers additional insight into gender-based acquisition trends. A closer examination of

Figure 7 shows that Eugène Atget produced the highest number of works in the collection at approximately 5,000, followed by Lesley Van der Werf with around 2,500. Sarah Benjamin stands out as one of the most represented female artists, with around 3,500 works, whereas Lily Peters has roughly 750. The top-ranked male artist has significantly more works than the top-ranked female artist. This disparity becomes more pronounced further down the rankings: the fifth most represented woman has approximately 250 pieces, while her male counterpart has about 1,500. These figures suggest that women artists have historically encountered barriers to inclusion, potentially due to systemic biases in acquisition practices, underscoring the importance of advancing more equitable representation policies.

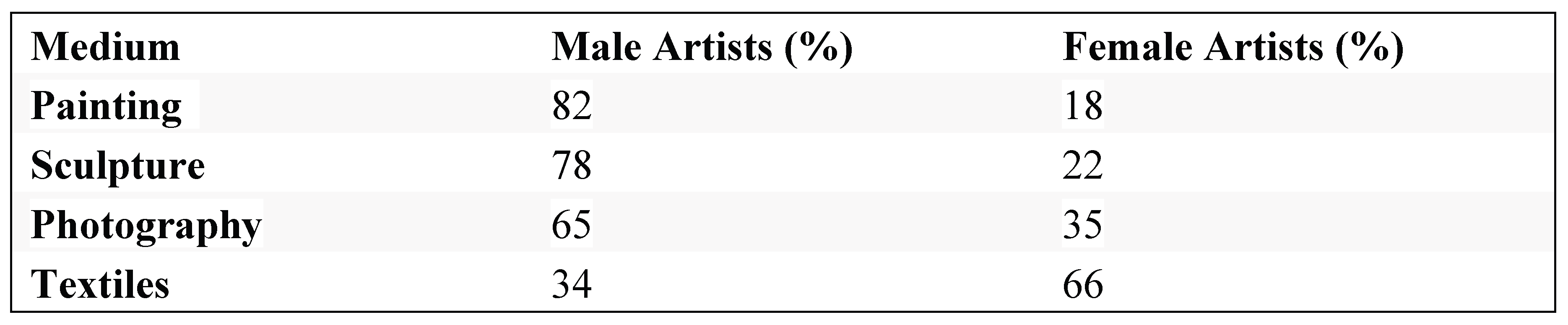

Finally, considering gender representation by artistic medium reveals additional contrasts.

Figure 8 presents gender representation across four artistic mediums in MoMA’s collection. Male artists significantly outnumber female artists in painting (82% vs. 18%), sculpture (78% vs. 22%), and photography (65% vs. 35%). In contrast, textiles is the only medium where female artists represent the majority, comprising 66% of the artists in the collection. These figures highlight medium-specific gender disparities in the museum’s holdings.

This study’s results have brought to light the many dimensions of male overrepresentation within MoMA’s collection, revealing how gender imbalances manifest across nationalities and mediums. The data not only reflects a disproportionate presence of male artists overall but also shows how men continue to dominate traditionally prestigious fields like painting and sculpture. Research has likewise revealed a persistent bias favoring male artists as “innovators,” such as Picasso and Pollock. In contrast, female artists were often excluded from gallery spaces and the collector networks that contributed works to MoMA. Although the museum’s 2019 reinstallation aimed to increase the visibility of women artists, it drew criticism for practicing checklist feminism—including works by women without fully acknowledging or addressing their historical exclusion and marginalization (Reilly 2019). With such criticisms in mind, this study points to the need for museums to examine the practices that perpetuate gender disparities and influence the cultural narratives presented to the public, not only in terms of inclusion, but also in terms of nationality, medium, and other forms of representation.

Conclusion

This paper has examined gender disparities within MoMA’s collection, revealing how deeply embedded institutional biases have historically positioned male artists as central figures of modernism. Although the findings indicate a narrowing gender gap, recent initiatives suggest that achieving systemic change requires the implementation of proactive acquisition policies, with funding specifically designated for women and non-binary artists. Greater emphasis must also be placed on displaying the work of women of color and LGBTQ+ artists, whose contributions remain underrepresented. To accomplish these goals, MoMA should consider forming partnerships with organizations that support female artists, as well as launching mentorship programs for emerging women artists. Transparency is also key; the institution should publish annual diversity statistics related to acquisitions and exhibitions. While regression models effectively capture broad trends, deeper learning models offer more precise analysis. Expanding the dataset to include global museum collections would therefore provide a more comprehensive perspective on representation in the art world. Such efforts can inform actionable recommendations and help address the structural barriers female artists continue to face.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Chadwick, W. (2007). Women, Art, and Society. Thames & Hudson.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167.

- D’Souza, A. (2018). Whitewalling: Art, race & protest in 3 acts. Badlands Unlimited.

- Getty Research Institute. (n.d.) Guerrilla Girls Archive. https://www.getty.edu/research/special_collections/notable/guerrilla_girls.html.

-

MoMA collection - automatic update. (2025). Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Museum of Modern Art. (2021). Collection of gender diversity report [Technical report]. Museum of Modern Art.

- Museum of Modern Art. (n.d.). Modern Women: Women Artists at the Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/interactives/modern_women/exhibitions/.

- Museum of Modern Art. (2010). Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography. https://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/1038.

- Nochlin, L. (1971). Why have there been no great women artists? ARTnews, 69(9), 22–39. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/retrospective/why-have-there-been-no-great-women-artists-4201/.

- Pollock, G. (1988). Vision and difference: Feminism, femininity and the histories of art. Routledge.

- Reilly, M. (2019, October 21). MoMA has rehangs—but has it changed? ARTnews. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/reviews/moma-rehang-art-historian-maura-reilly-13484/.

- Saltz, J. (2007, November 15). Where are all the women? New York Magazine. https://nymag.com/arts/art/features/40979/.

- Shoard, C. (2024, April 16). Faith Ringgold’s response to Picasso painting acquired by MoMA in landmark move. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2024/apr/16/faith-ringgold-picasso-moma-black-american.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).