Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Understanding Hallucinations

2.1. Definition of Hallucinations

2.2. Categories of Hallucinations

-

Intrinsic hallucinations (factuality errors) occur when a model generates content that contradicts established facts, its training data, or referenced input [6,12,13,62,137,286,315]. Following the taxonomic names in [292] the subtypes of this category may include (but are not limited to):

- ○

- Entity-error hallucinations, where the model generates non-existent entities or misrepresents their relationships (e.g., inventing fake individuals, non-existent biographical details [87] or non-existent research papers), often measured via entity-level consistency metrics [98], as shown in [13,28,208,286].

- ○

- ○

- ○

-

Extrinsic hallucinations (faithfulness errors) appear when the generated content deviates from the provided input or user prompt. These hallucinations are generally characterized by the inability to verify the generated output which may or may not be true but, in either case, it is either not directly deducible from the user prompt or it contradicts itself [12,13,62,219,279,292]. Extrinsic hallucinations may manifest as:

- ○

- ○

- ○

- Emergent hallucinations, defined as those arising unpredictably in larger models due to scaling effects [92]. These can be attributed to cross-domain reasoning and modality fusion especially in multi-modal settings or Chain of Thought (CoT) prompting scenarios [13,92,123], multi-step inference errors [147] and abstraction or alignment issues as shown in [28,62] and [123]. For instance, self-reflexion demonstrates mitigation capabilities, effectively reducing hallucinations only in models above a certain threshold (e.g., 70B parameters), while paradoxically increasing errors in smaller models due to limited self-diagnostic capacity [292].

2.3. Underlying Causes of Hallucinations

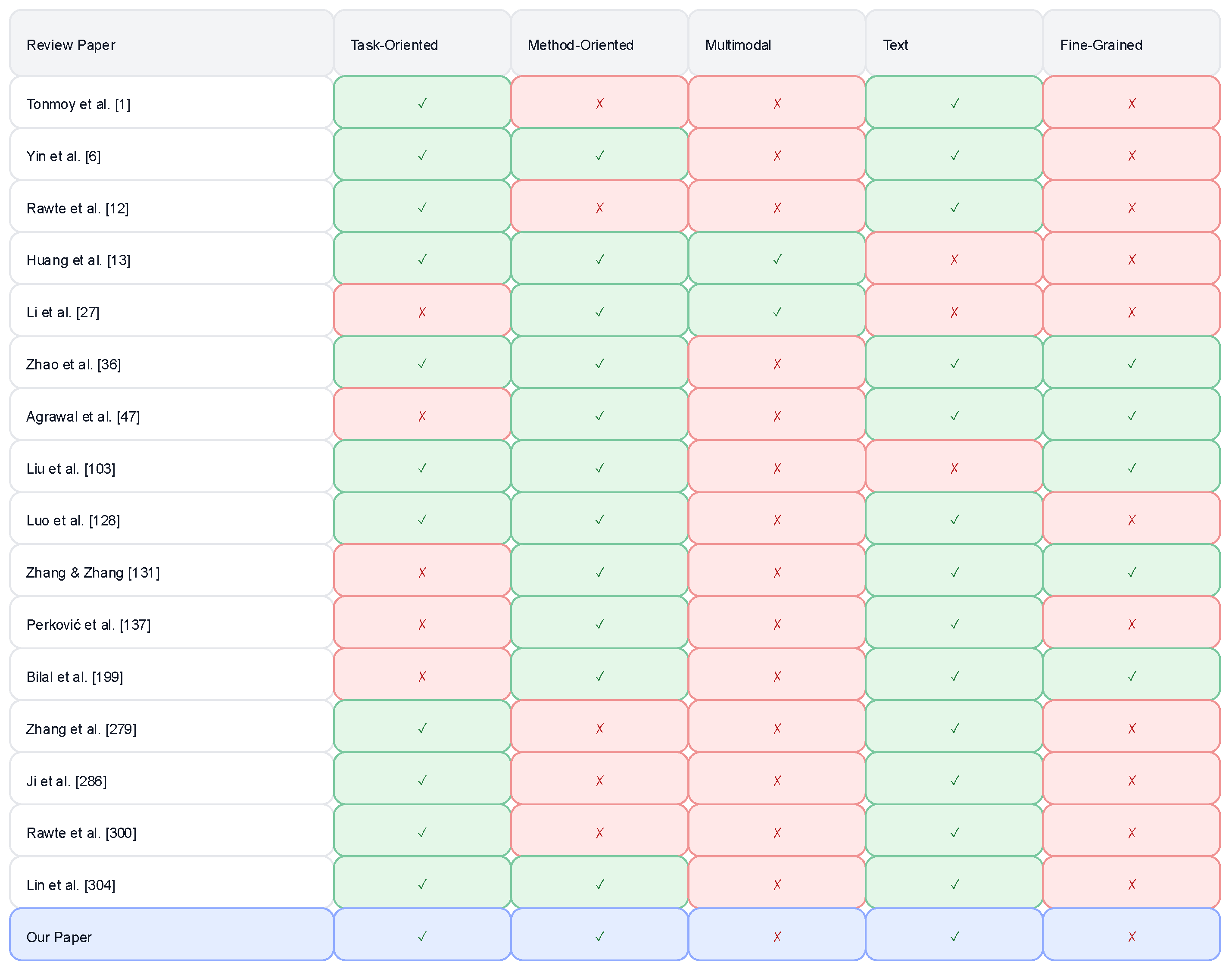

3. Related Works

4. Review Methodology, Proposed Taxonomy, Contributions and Limitations

4.1. Review Methdology

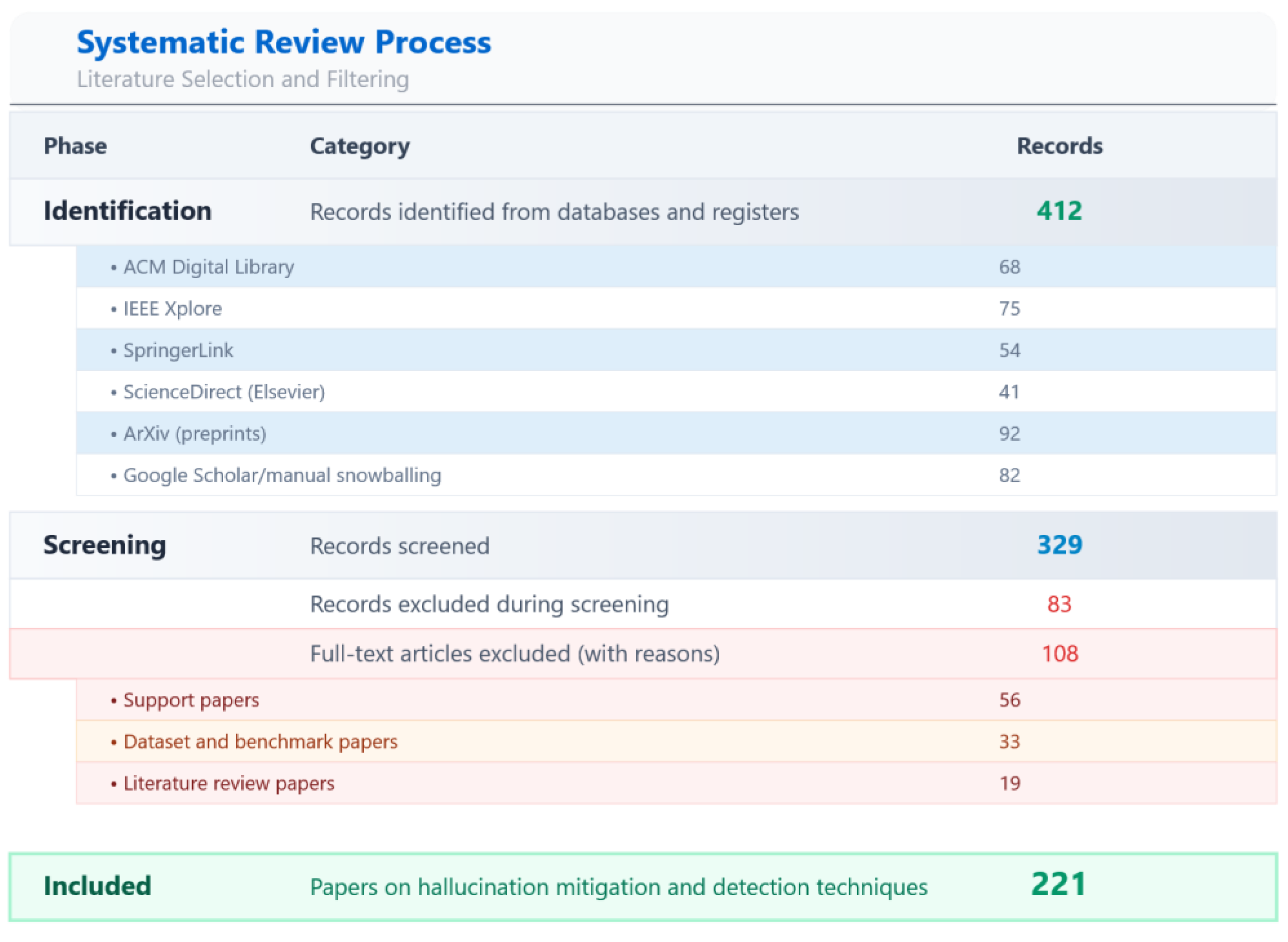

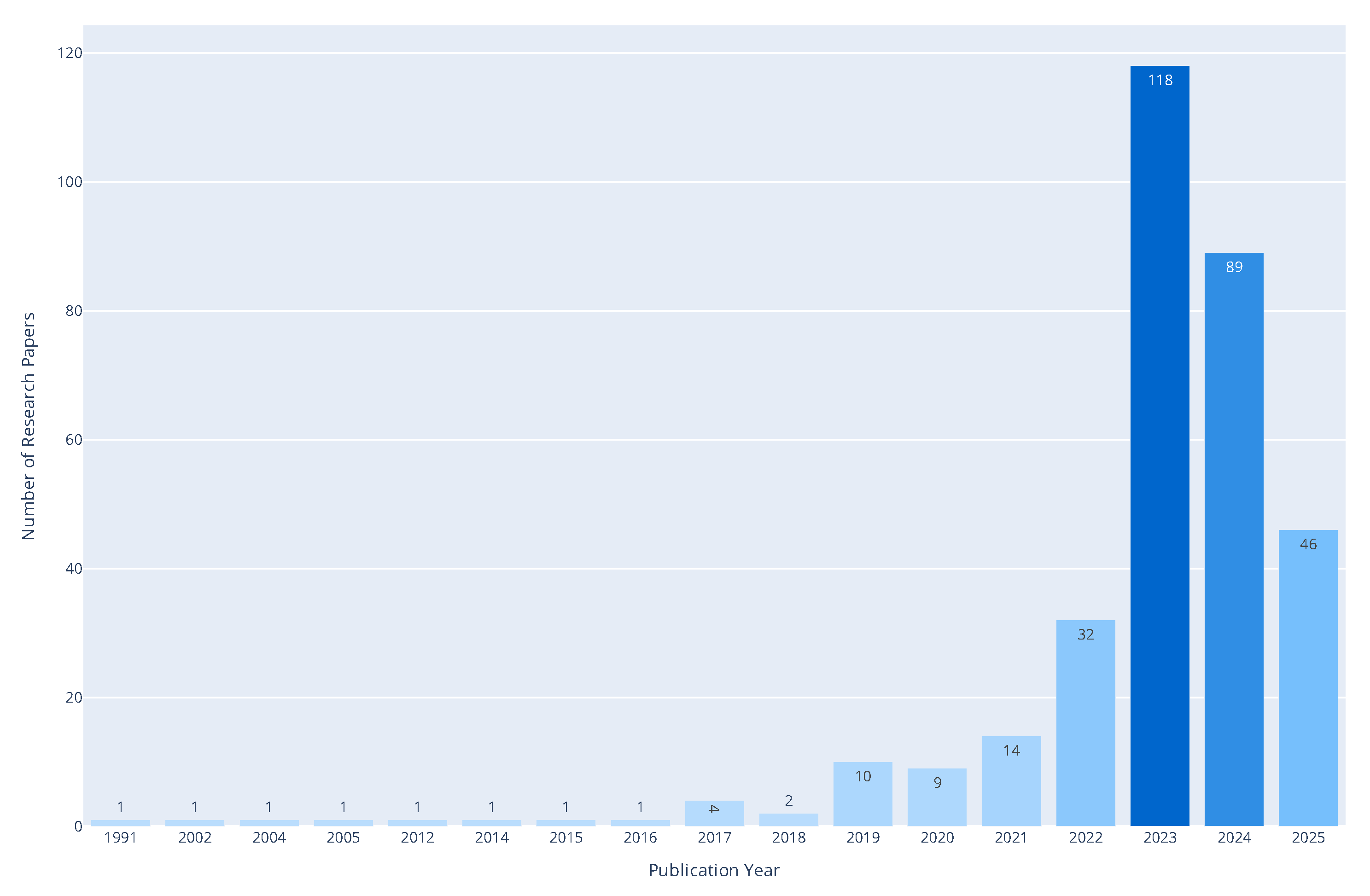

- Literature Retrieval: We systematically collected research papers from major electronic archives—including Google Scholar, ACM Digital Library, IEEE Xplore, Elsevier, Springer, and ArXiv—with a cutoff date of August 12, 2025. Eligible records were restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles, conference papers, preprints under peer review, and technical reports, while non-academic sources such as blogs or opinion pieces were excluded. A structured query was used, combining keywords: ("mitigation" AND "hallucination" AND "large language models") OR "evaluation". In addition, we examined bibliographies of retrieved works to identify further relevant publications.

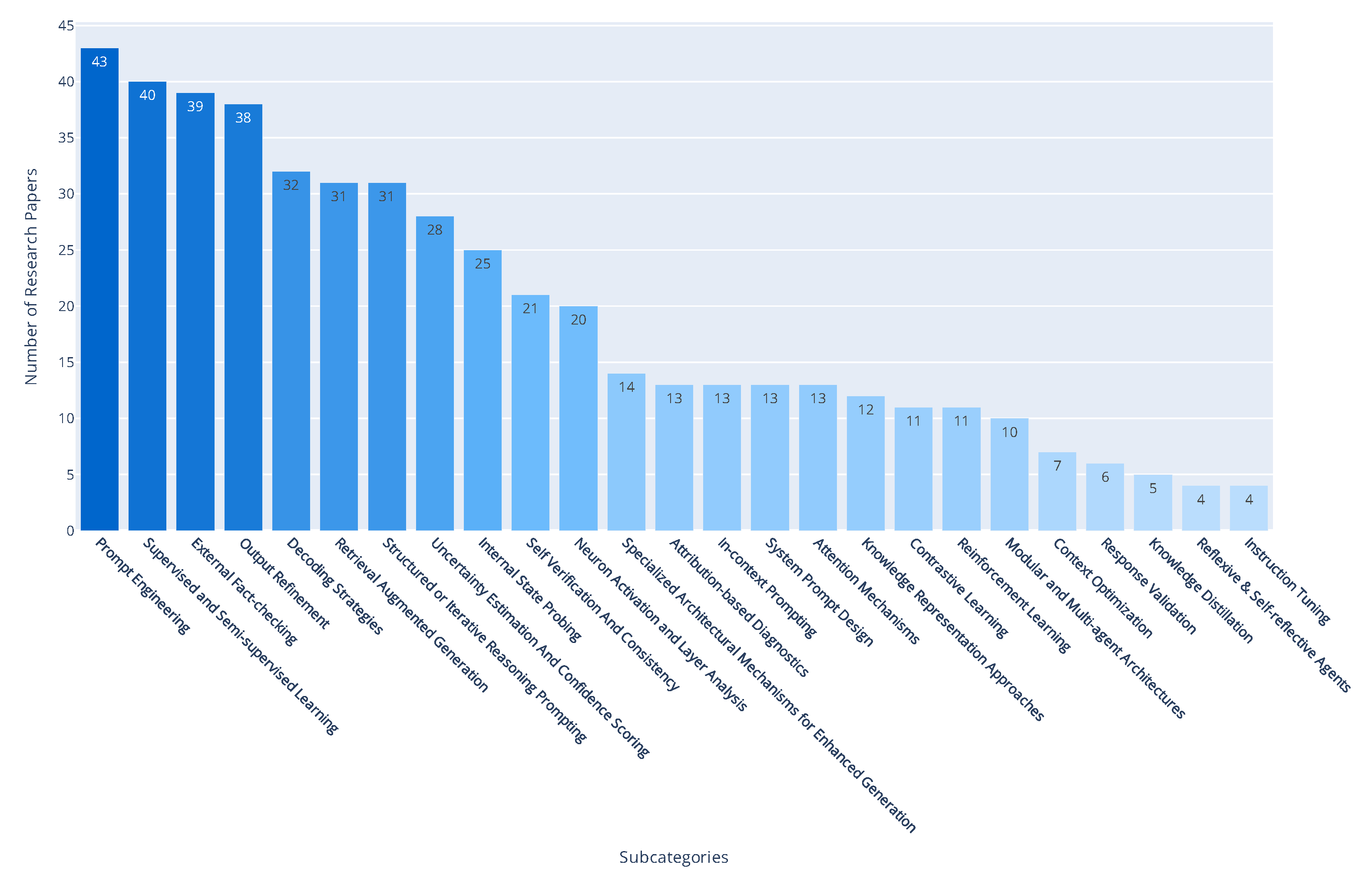

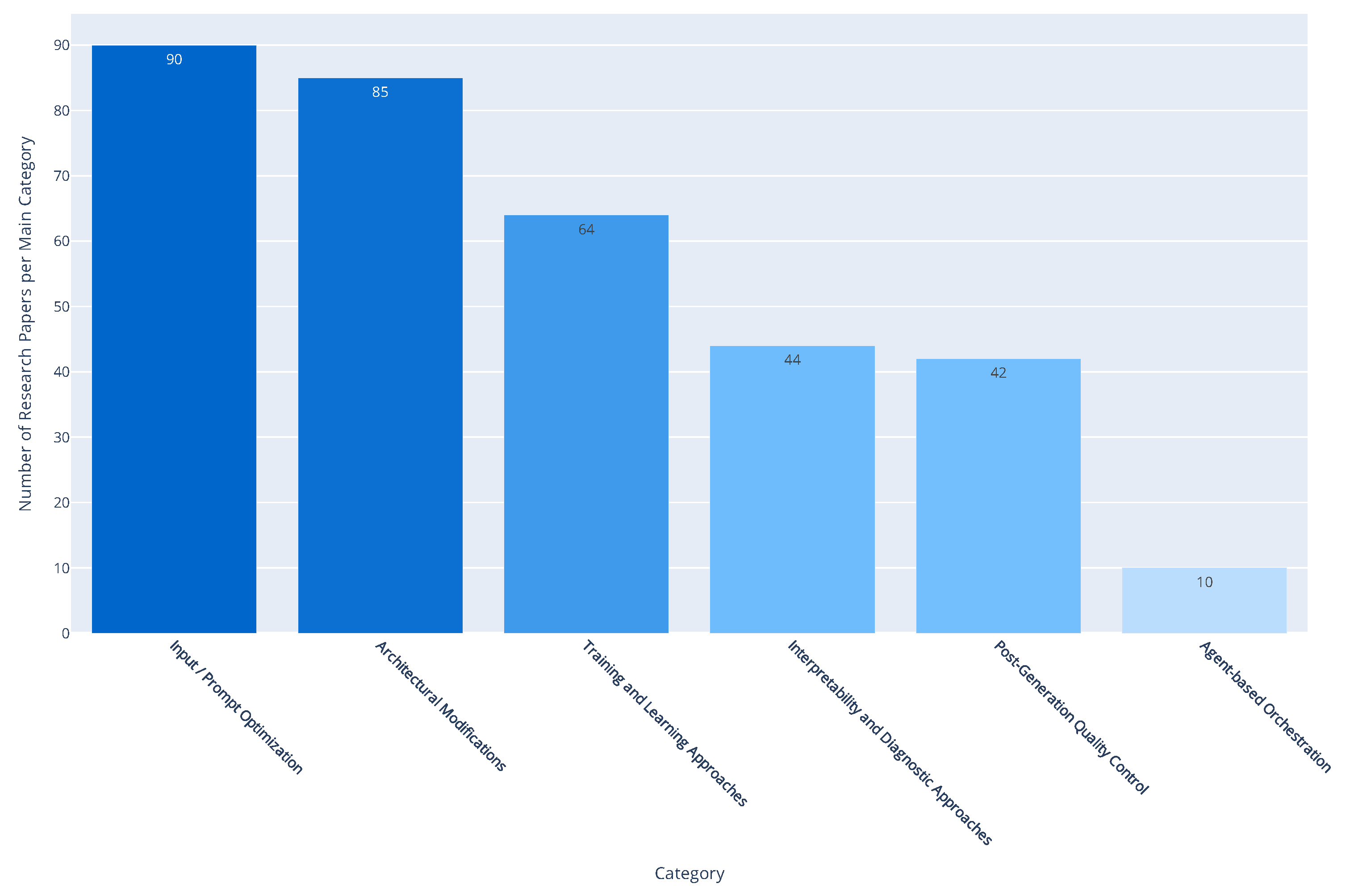

- Screening: The screening process followed a two-stage approach. First, titles and abstracts were screened for topical relevance. Records passing this stage underwent a full-text review to assess eligibility. Out of 412 initially retrieved records, 83 were excluded as irrelevant at the screening stage. The 329 eligible papers were then examined in detail and further categorized into support studies, literature reviews, datasets/benchmarks, and works directly proposing hallucination detection or mitigation methods. The final set of 221 studies formed the basis of our taxonomy. This process is summarized in the PRISMA-style diagram below.

- Paper-level tagging, where every study was assigned one or more tags corresponding to its employed mitigation strategies. Our review accounts for papers that propose multiple methodologies by assigning them multiple tags, ensuring a comprehensive representation of each paper’s contributions.

- Thematic clustering, where we consolidated those tags into six broad categories presented analytically in 4.2. This enabled us to generate informative visualizations that reflect the prevalence and trends among different mitigation techniques.

- Content-specific retrieval: To gain deeper insight into mitigation strategies, we developed a custom Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) system based on the Mistral language model as an additional research tool, which enabled us to extract content-specific passages directly from the research papers.

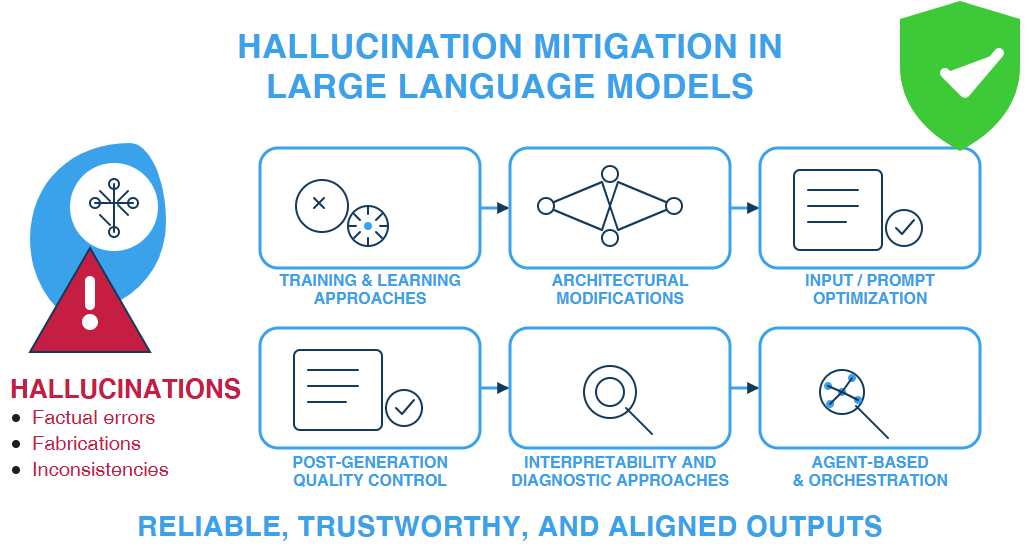

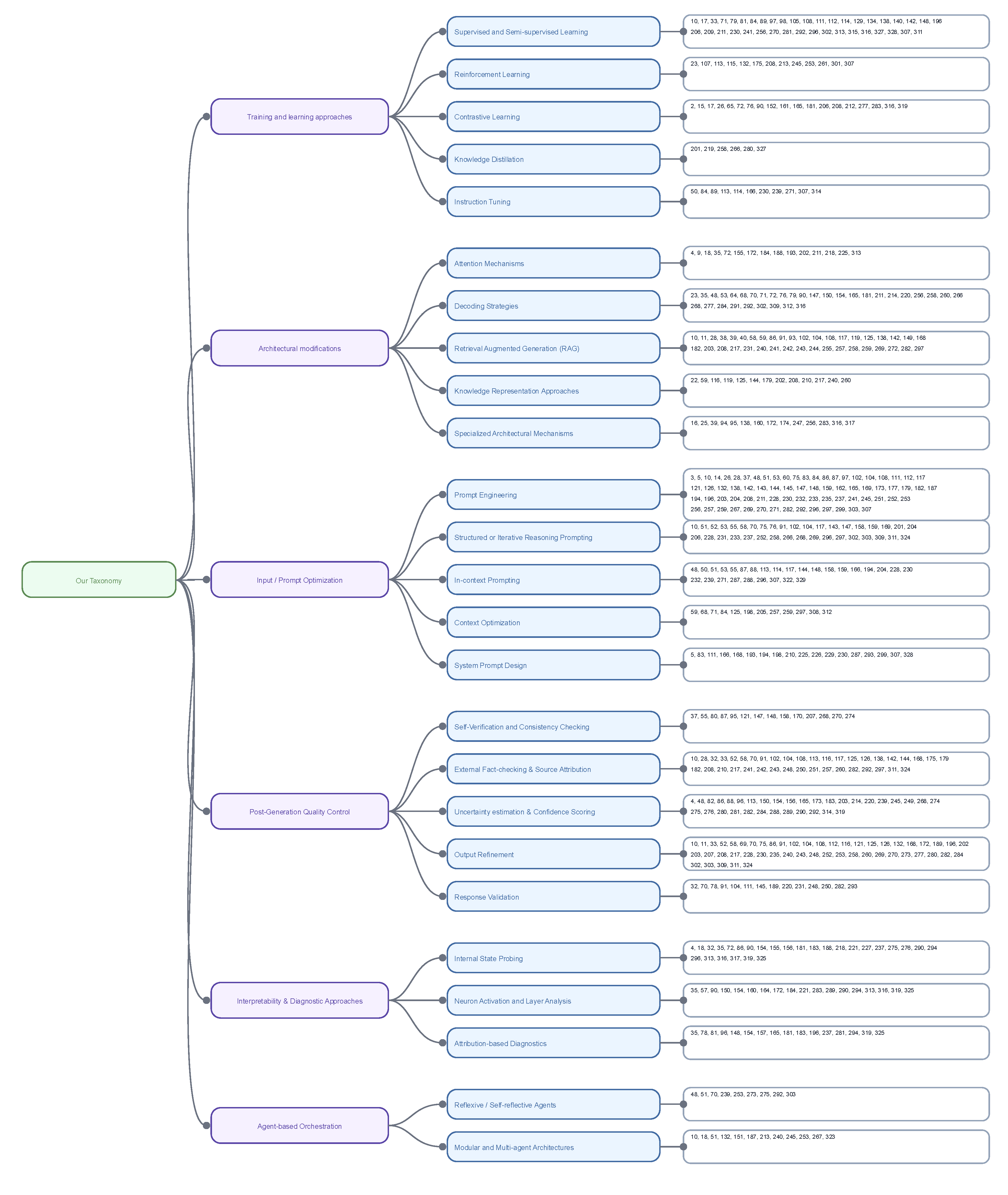

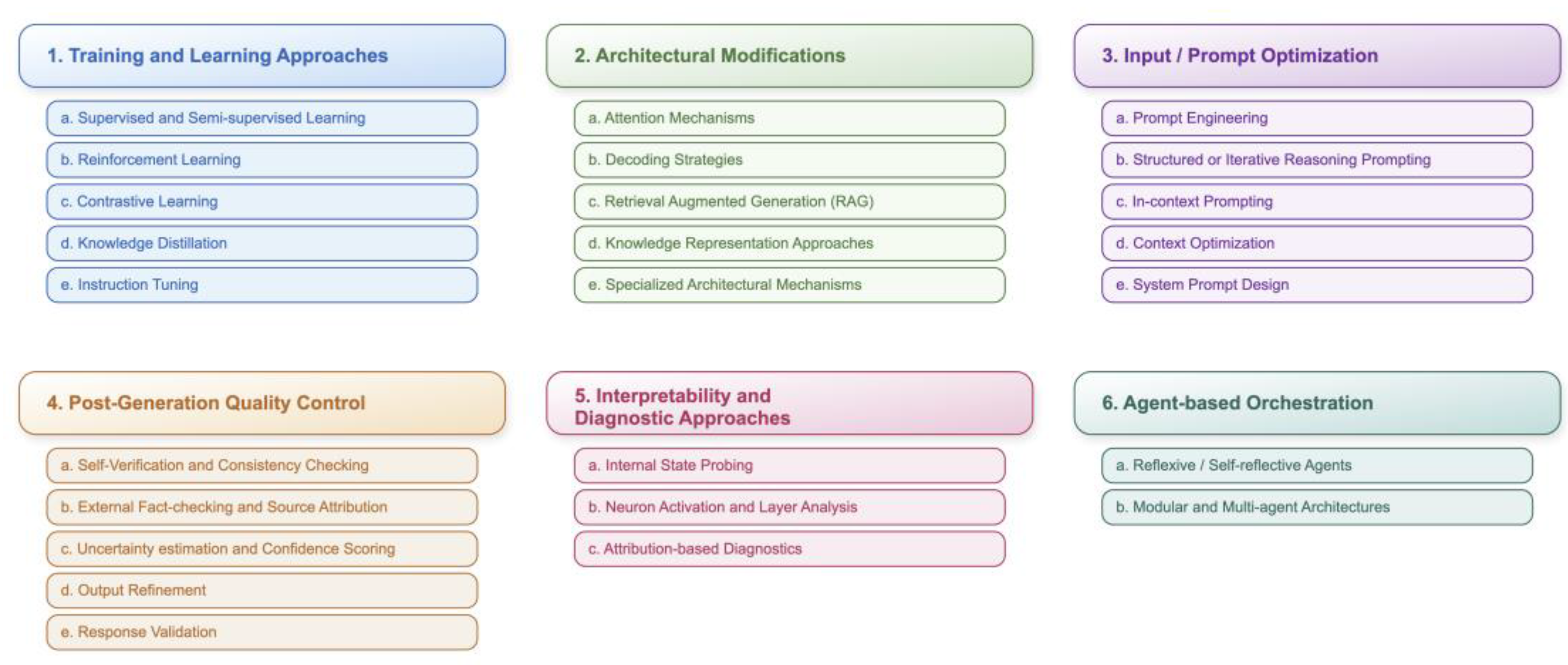

4.2. Proposed Taxonomy and Review Organization

- Training and Learning Approaches (5.1): Encompasses diverse methodologies employed to train and refine AI models, shaping their capabilities and performance (e.g., Supervised Learning, Reinforcement Learning, Knowledge Distillation).

- Architectural Modifications (5.2): Covers structural changes and enhancements made to AI models and their inference processes to improve performance, efficiency, and generation quality (e.g., Attention Mechanisms, Decoding Strategies, Retrieval Augmented Generation).

- Input/Prompt Optimization (5.3): Focuses on strategies for crafting and refining the text provided to AI models to steer their behavior and output, often specifically to mitigate hallucinations (e.g., Prompt Engineering, Context Optimization).

- Post-Generation Quality Control (5.4): Encompasses essential post-generation checks applied to text outputs, aiming to identify or correct inaccuracies (e.g., Self-verification, External Fact-checking, Uncertainty Estimation).

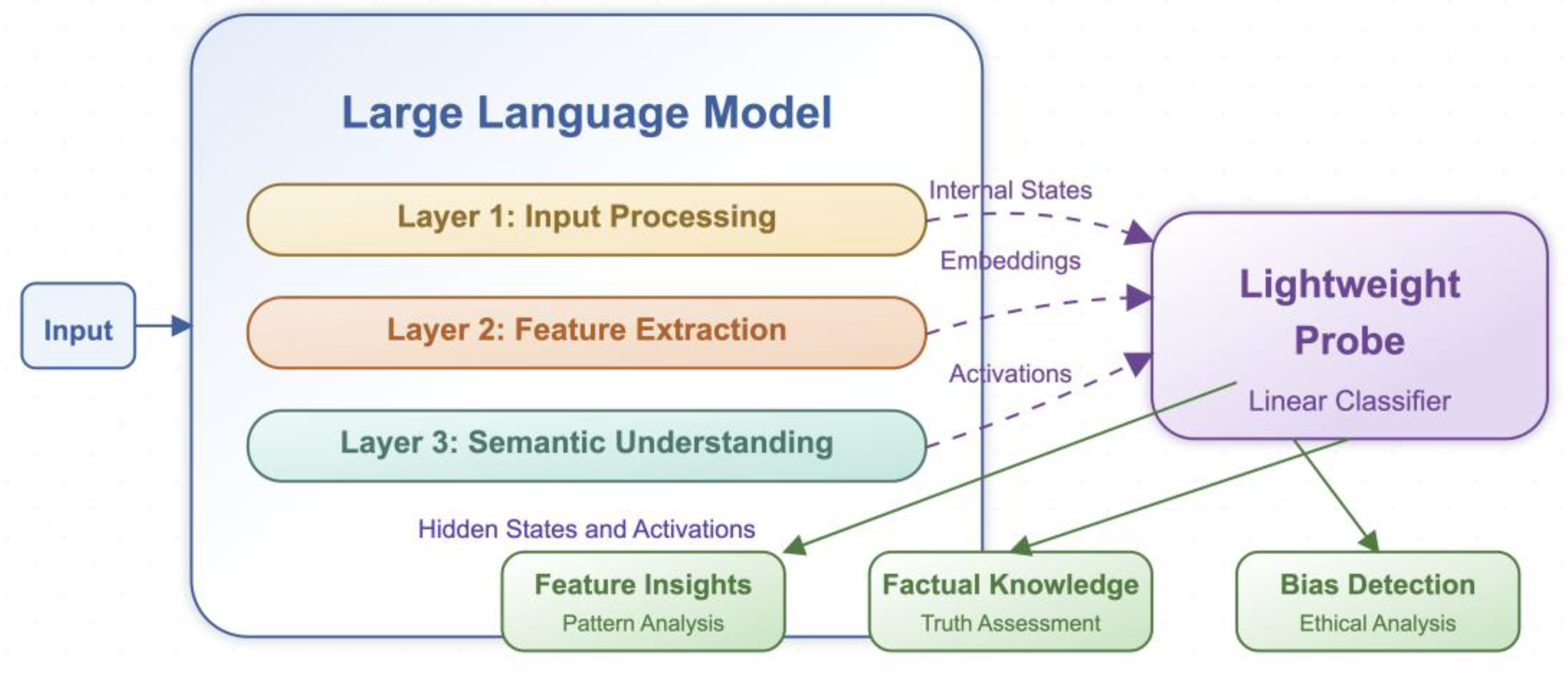

- Interpretability and Diagnostic Approaches (5.5): Encompasses methods that help researchers understand why and where a model may be hallucinating (e.g., Internal State Probing, Attribution-based diagnostics).

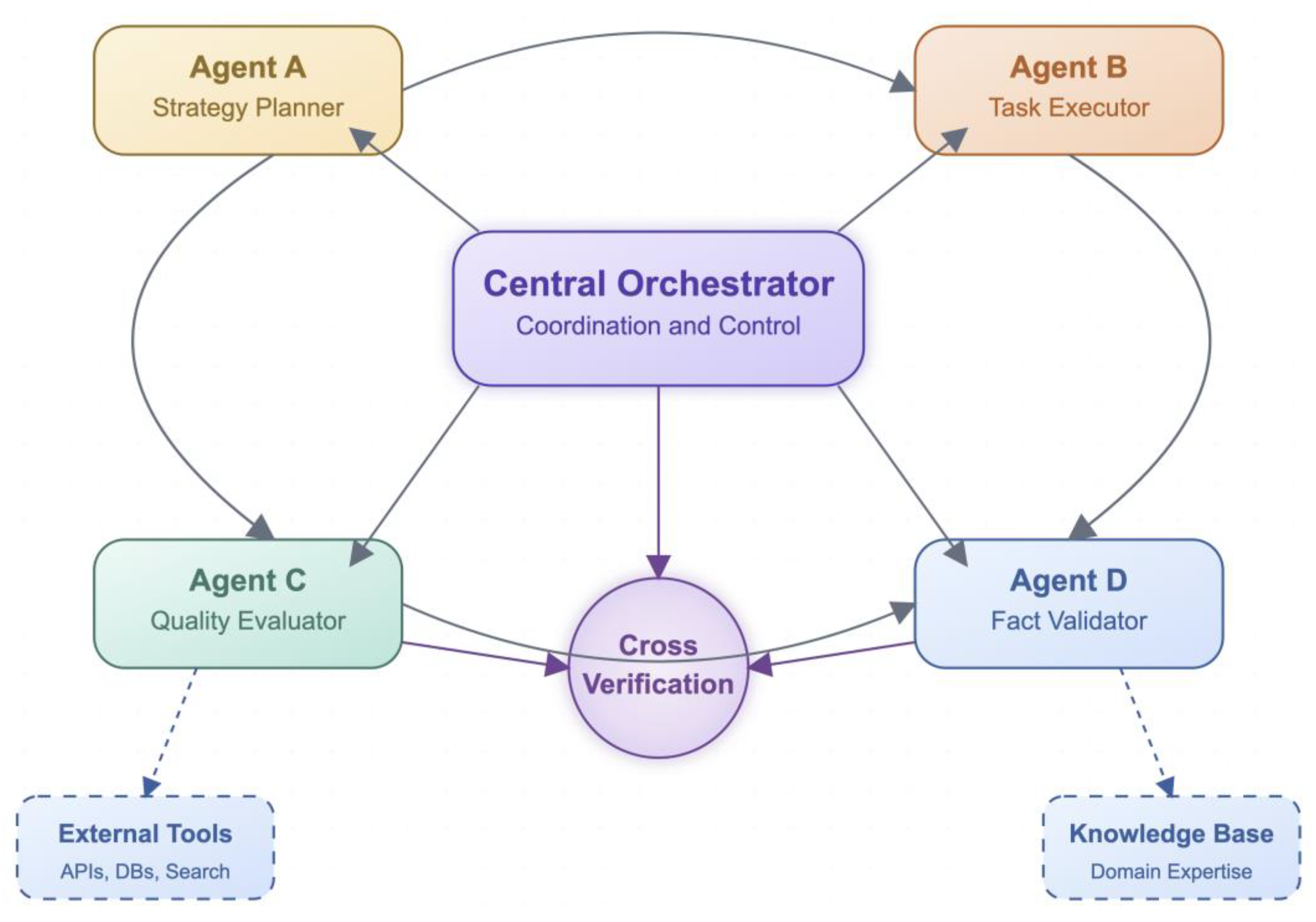

- Agent-based Orchestration (5.6): Includes frameworks comprising single or multiple LLMs within multi-step loops, enabling iterative reasoning, tool usage, and dynamic retrieval (e.g., Reflexive Agents, Multi-agent Architectures).

4.3. Contributions and Key Findings

5. Methods for Mitigating Hallucinations

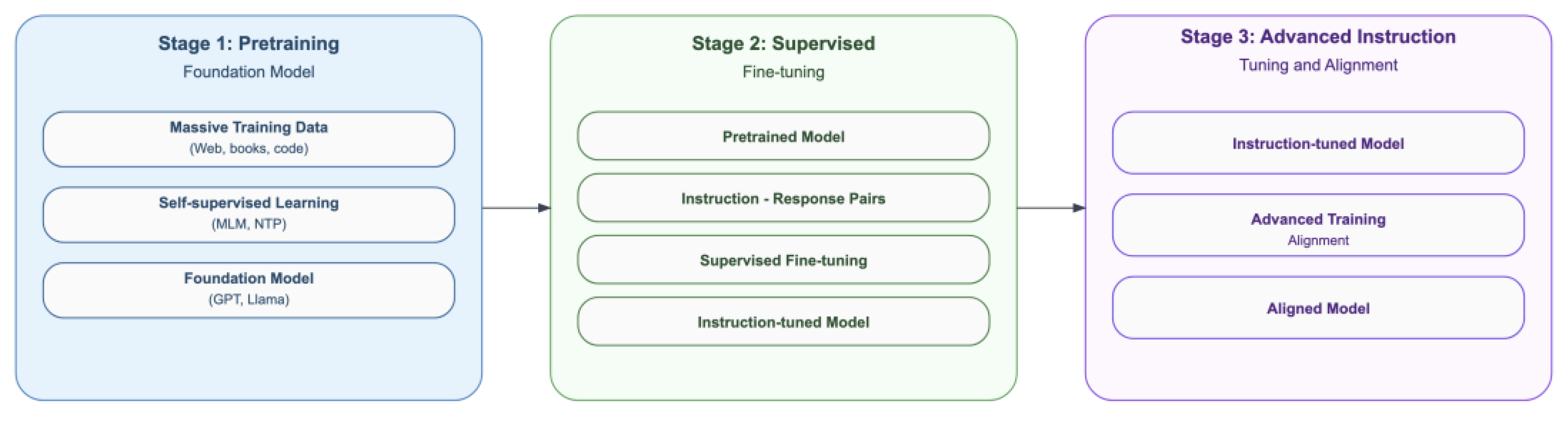

5.1. Training and Learning Approaches

5.1.1. Supervised and Semi-Supervised Learning

- Fine-Tuning with factuality objectives, where techniques such as FactPEGASUS make use of ranked factual summaries for factuality-aware fine-tuning [105] while FAVA generates synthetic training data using a pipeline involving error insertion and post-processing to detect and correct fine-grained hallucinations [112]. Similarly, Faithful Finetuning employs weighted cross-entropy and fact-grounded QA losses to enhance faithfulness and minimize hallucinations [209]. Principle Engraving fine-tunes the base LLaMA model on self-aligned responses that adhere to specific principles [230], while [292] explores how the combination of supervised fine-tuning and RLHF impacts hallucinations. Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) provide the conceptual basis for [17] which introduces Adversarial Feature Hallucination Networks (AFHN). AFHN synthesizes fake features for new classes by using labeled samples as conditional context. The framework uses a classification regularizer for feature discriminability and an anti-collapse regularizer that boosts the diversity of the synthesized features.

- Synthetic Data & Weak Supervision, where studies automatically generated hallucinated data or weak labels for training. For instance, in [68] hallucinated tags are prepended to the model inputs so that it can learn from annotated examples to control hallucination levels while [81] uses BART and cross-lingual models with synthetic hallucinated datasets for token-level hallucination detection. Similarly, Petite Unsupervised Research and Revision (PURR) involves fine-tuning a compact model on synthetic data comprised of corrupted claims and their denoised versions [235] while TrueTeacher uses labels generated by a teacher LLM to train a student model on factual consistency [311].

- Preference-Based Optimization and Alignment: In [114] a two-stage framework first combines supervised fine-tuning using curated legal QA data and Hard Sample-aware Iterative Direct Preference Optimization (HIPO) to ensure factuality by leveraging signals based on human preferences while in [270] a lightweight classifier is finetuned on contrastive pairs (hallucinated vs. non-hallucinated outputs). Similarly, mFACT—a metric for factual consistency—is derived from training classifiers in different target languages [79], while Contrastive Preference Optimization (CPO) combines a standard negative-log likelihood loss with a contrastive loss to finetune a model on a dataset consisting of triplets (source, hallucinated translation, corrected translation) [206]. UPRISE employs a retriever model that is trained using signals from an LLM to select optimal prompts for zero-shot tasks, allowing the retriever to directly internalize alignment signals from the LLM [322]. Finally, behavioral tuning uses label data (dialogue history, knowledge sources, and corresponding responses) to improve alignment [84].

- Knowledge-Enhanced Adaptation: Techniques like HALO injects Wikidata entity triplets or summaries via fine-tuning [140] while Joint Entity and Summary Generation employs a pre-trained Longformer model which is finetuned on the PubMed dataset, in order to mitigate hallucinations by supervised adaptation and data filtering [134]. The impact of injecting new knowledge in LLMs via supervised finetuning and the potential risk of hallucinations is also studied in [89].

- Hallucination Detection Classifiers: [142] involves fine-tuning a LLaMA-2-7B model to classify hallucination-prone queries using labeled data while in [129] a sample selection strategy improves the efficiency of supervised fine-tuning by reducing annotation costs while preserving factuality through supervision.

- Training of factuality classifiers: Supervised finetuning is used to train models on labeled text data in datasets such as HDMBENCH, TruthfulQA, and multilingual datasets demonstrating improvements in task-specific performance and factual alignment [33,138,211]. Additionally, training enables classifiers to detect properties such as honesty and lies within intermediate representations resulting in increased accuracy and separability of these concepts as shown in [148,256,296].

- Synthetic data creation: In the Fine-Grained Process Reward Model (FG-PRM), various hallucination types are injected into correct solutions of reasoning steps. The synthetic dataset thus created is used to train six Process Reward Models, each able to detect and mitigate a specific hallucination type [111] while techniques such as RAGTruth includes human-annotated labels indicating whether generated responses are grounded in retrieved content, which enables supervised training and evaluation of hallucination detection models [241]. Similarly, [97] addresses over-reliance on parametric knowledge by introducing an entity-based substitution framework that generates conflicting QA instances by replacing named entities in the context and answer.

- Refining pipelines: Supervised training is used to train a critic model using the base LLM’s training data and synthetic negatives [71]. TOPICPREFIX is an augmentation technique that prepends topic entities from Wikipedia to improve contextual grounding and factuality [108] while the training of the Hypothesis Verification Model (HVM) on the FATE dataset aims to help the model recognize faithful and unfaithful text [302], while similar approaches discern between truthful and untruthful representations [313,315,316]. Self-training is used to train models on synthetic data with superior results compared to crowdsourced data [327] and finally, in WizardLM a LLaMA model is finetuned on generated instructions, thus resulting in better generalization [328].

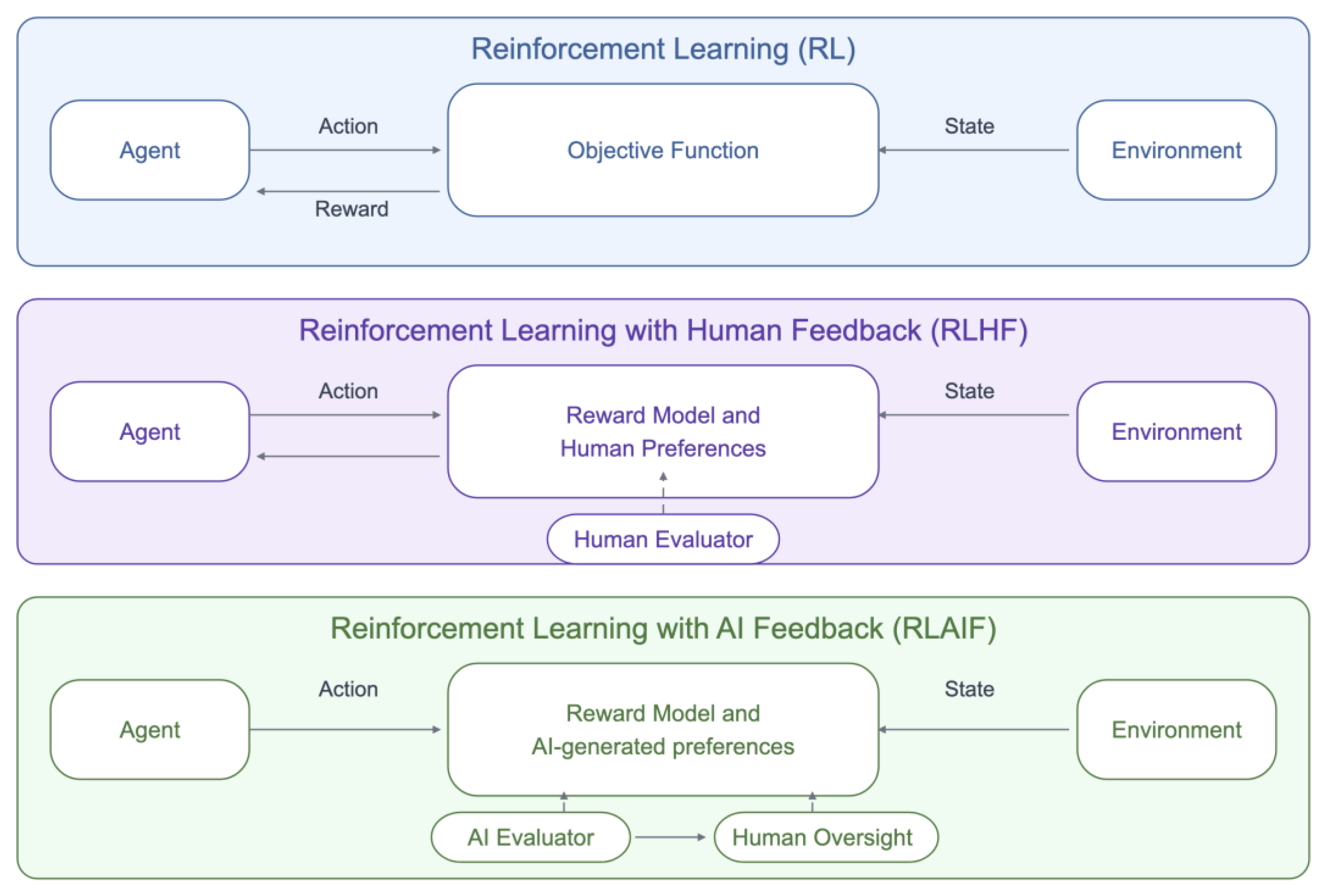

5.1.2. Reinforcement Learning

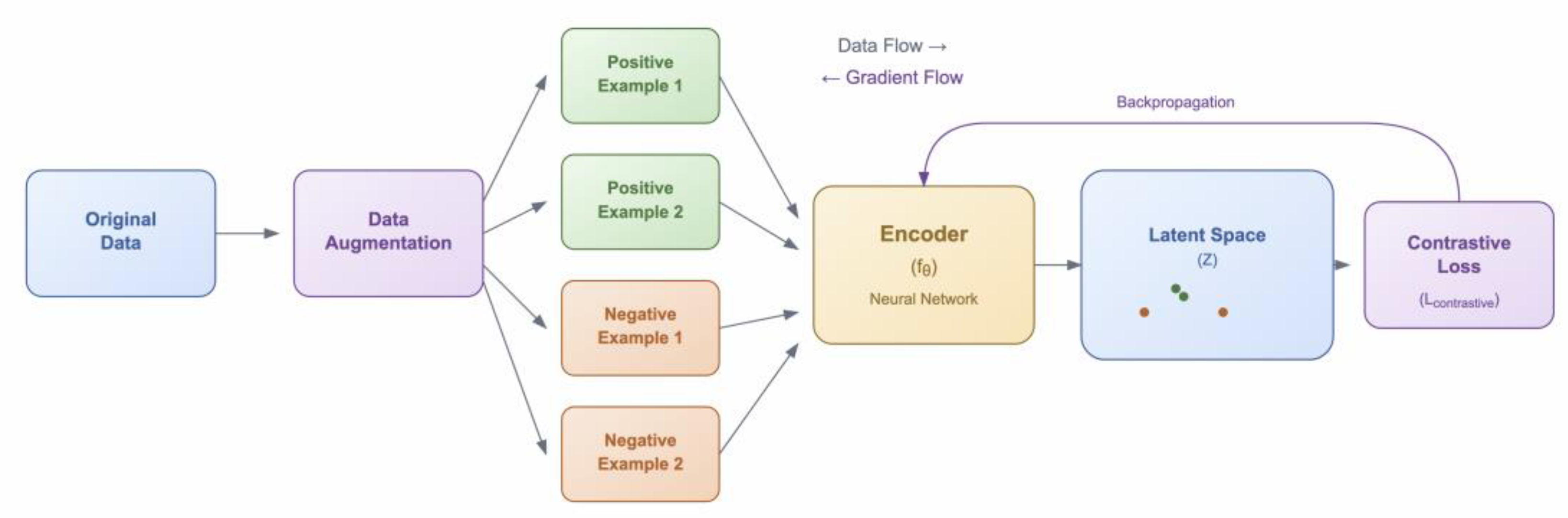

5.1.3. Contrastive Learning

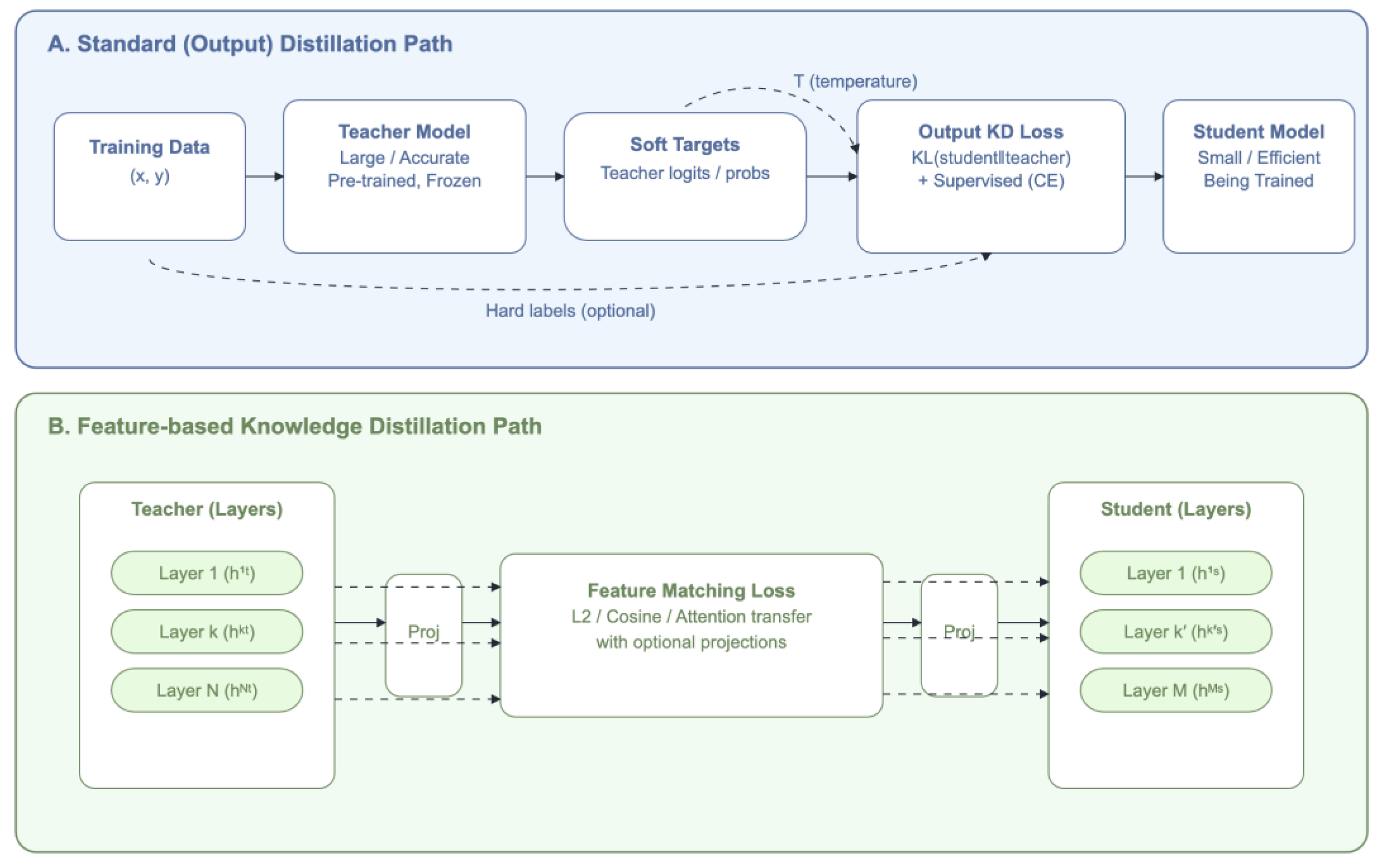

5.1.4. Knowledge Distillation

5.1.5. Instruction Tuning

- Factual alignment, such as in [114], where LLMs are finetuned using a dataset of legal instructions and responses, explicitly grounding outputs in legal knowledge, thus aligning their behavior to domain-specific prompts and reducing factual hallucinations. Curriculum-based Contrastive Learning-based Cross-lingual Chain-of-Thought (CCL-XCoT) combines curriculum-based cross-lingual contrastive learning with instruction fine-tuning to transfer factual knowledge from high-resource to low-resource languages. Furthermore, its Cross-lingual Chain of Thought (XCoT) strategy guides the model to reason in a high-resource language and then generate in the target language, thereby reducing context-related hallucinations [50].

- Consistency alignment, which is achieved in [153] during a two-stage supervised fine-tuning process: The first step uses instruction–response pairs while in the second step, pairs of semantically similar instructions, which are implemented via contrastive-style learning, are used to enforce aligned responses across instructions.

- Data-centric grounding, where Self-Instruct introduces a scalable, semi-automated method for generating diverse data without human annotation [271]. It begins with a small set of instructions and uses a pre-trained LLM to generate new tasks and corresponding input-output examples, which are then filtered and used to fine-tune the model, thus generating more aligned and grounded outputs.

5.2. Architectural Modifications

5.2.1. Attention Mechanisms

5.2.2. Decoding Strategies

- Probabilistic Refinement & Confidence-Based Adjustments, where techniques such as Context-aware decoding adjust token selection by prioritizing information aligned with relevant context so as to emphasize contextual information over its internal prior knowledge. This is achieved by amplifying the difference between output probabilities with and without the context, effectively downplaying prior knowledge when more relevant contextual details are available [66], [312]. Another direction involves entropy-based decoding adjustments, where the model’s cross-layer entropy or confidence values are used to penalize hallucination-prone outputs [150] and Conditional Pointwise Mutual Information (CPMI) which adjusts the score of the conditional entropy of the next-token distribution so as to prioritize tokens more aligned with the source [214]. [256] uses logits and their probabilities to refine the standard decoding process by interpreting and manipulating the outputs during generation, while Confident Decoding integrates predictive uncertainty into a beam search variant to reduce hallucinations, with epistemic uncertainty guiding token selection towards greater faithfulness [284]. Similarly, [220] modifies the beam search decoding process to prioritize outputs with lower uncertainty. This method leverages the connection between hallucinations and predictive uncertainty, demonstrating that higher predictive uncertainty correlates with a greater chance of hallucinations [220]. Selective abstention Learning (SEAL) introduces a selective abstention learning framework where an LLM is trained to output a special [REJ] token when predictions conflict with its parametric knowledge. During inference, its abstention-aware decoding leverages the [REJ] probability to penalize uncertain trajectories, thereby guiding generation toward more factual outputs [24]. Finally, Factual-nucleus sampling extends the concept of nucleus sampling [291] by adjusting the sampling randomness during decoding based on the sentence position, thereby significantly reducing factual errors [108].

- Beyond probabilistic refinements, some decoding strategies are inspired by contrastive learning to explicitly counter hallucinations. For instance, Decoding by Contrasting Retrieval Heads (DeCoRe) induces hallucinations through masking specific retrieval heads responsible for extracting contextual information and dynamically contrasting the outputs of the original base LLM and its hallucination-prone counterpart [72]. Delta mitigates hallucinations by randomly masking spans of the input prompt and then contrasting the output distributions generated for both the original and the masked prompts, thus effectively reducing the generation of hallucinated content [76]. Contrastive Decoding is an alternative to search-based decoding methods like nucleus or top-k sampling, which optimizes the difference between the log-likelihoods of an LLM and a SLM by introducing a plausibility constraint that filters out low-probability tokens [64]. Similarly, the Self-Highlighted Hesitation mechanism (SH2) uses contrastive decoding to manipulate the decision-making process at the token level by appending low-confidence tokens to the original context, thus leading the decoder to hesitate before generation [277]. Spectral Editing of Activations (SEA) projects token representations into directions of maximum information, thus amplifying signals that correlate with factuality while suppressing those linked to hallucinated outputs [283]. Similarly, Induce-then-contrast (ICD) constructs a "factually weak LLM" by inducing hallucinations from the original LLM, via fine-tuning with non-factual samples. These induced hallucinations are subsequently leveraged as a penalty term, thus effectively downplaying untruthful predictions [26]. In Active Layer Contrastive Decoding (ActLCD), a reward-driven classifier uses a reinforcement learning policy to determine when to apply contrastive decoding between selected layers, effectively framing decoding as a Markov decision process [15]. Finally, Self-contrastive Decoding (SCD) reduces the influence of tokens which are over-represented in the model’s training data to directly affect the selection of tokens during text generation, thus reducing knowledge overshadowing [165].

- Verification & Critic-Guided Mechanisms: A number of decoding strategies work in tandem with verification and critic-guided mechanisms to further improve the generation capabilities of the decoder. Critic-driven Decoding combines the probabilistic output of an LLM with a "text critic" classifier which assesses the generated text and steers the decoding process away from the generation of hallucinations [71]. Self-consistency samples from a diverse set of reasoning paths and selects the most consistent answer, leveraging the idea that correct reasoning tends to converge on the same answer. Furthermore, the consistency among the sampled paths can serve as an uncertainty estimate which helps to identify and mitigate potential hallucinations [268]. In Think While Effectively Articulating Knowledge (TWEAK) the generated sequences at each decoding step, along with their potential future sequences, are treated as hypotheses, which are subsequently reranked by an NLI model or a Hypothesis Verification Model (HVM) according to the extent to which they are supported by the input facts [302]. In a similar line of research, mFACT integrates a novel faithfulness metric directly into the decoding process, thereby evaluating each candidate summary regarding its factual consistency with the source document. Candidates that fall below a predetermined mFACT threshold are then pruned, effectively guiding the generation towards more factually accurate outputs [79]. Finally, Reducing Hallucination in Open-domain Dialogues (RHO) generates a set of candidate responses using beam search and re-ranks them based on their factual consistency, which is determined by analyzing various trajectories over knowledge graph sub-graphs extracted from an external knowledge base [260].

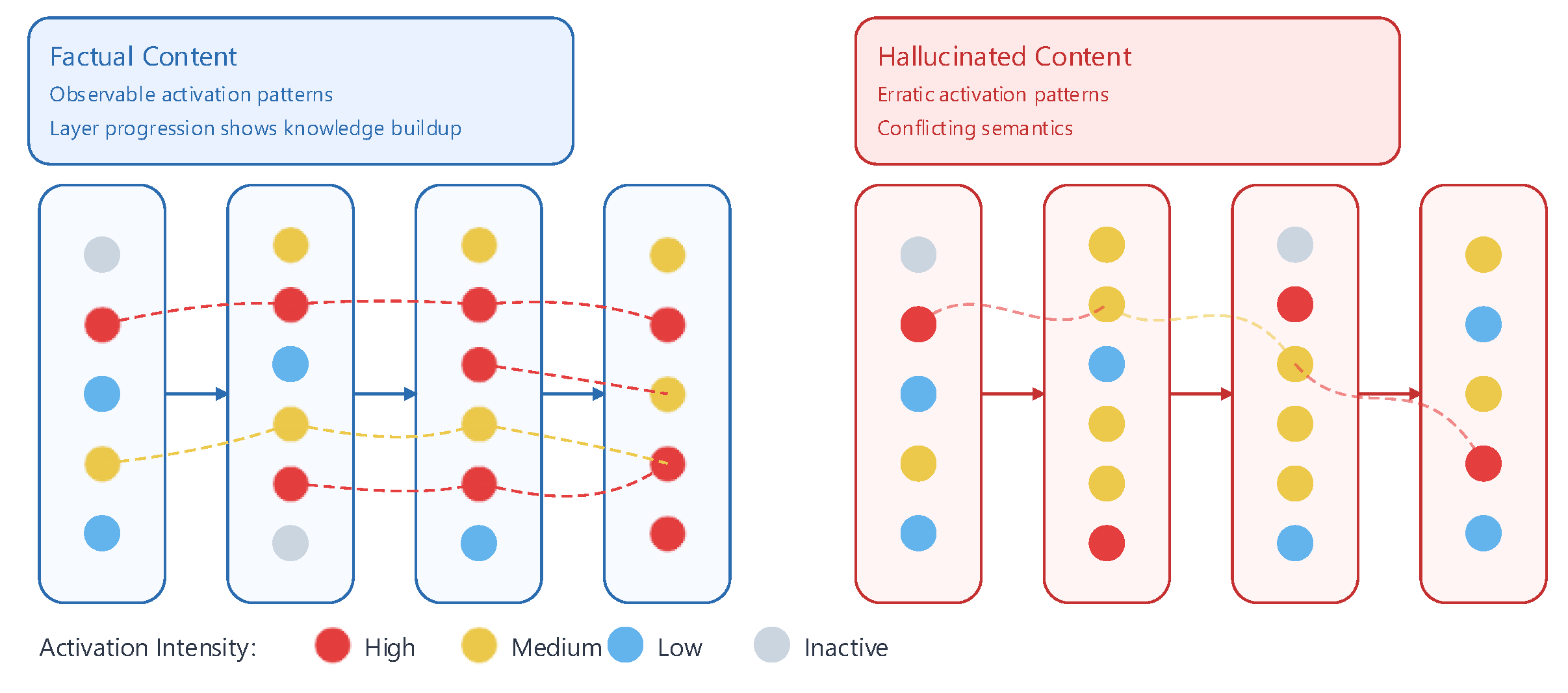

- Internal Representation Intervention & Layer Analysis: Understanding how LLMs encode information regarding the possible replies to a query, particularly within their early internal states, is particularly useful for developing decoding strategies that mitigate hallucinations [290]. Intermediate outputs which are prone to hallucinations often exhibit diffuse activation patterns, where activations are spread across multiple competing concepts rather than being focused on relevant references. In-context sharpness metrics, proposed in [154], leverage this observation by enforcing sharper token activations to ensure that predictions are derived from high-confidence knowledge areas. Similarly, Inference-time Intervention (ITI) involves shifting activations during inference and applies these adjustments iteratively until the full response is generated [155] while DoLa leverages differences in logits from earlier vs. later layers promoting the factual knowledge encoded in higher layers as opposed to syntactically plausible but less factual contributions from lower layers [90]. Activation Decoding is another constrained decoding method that directly adjusts token probabilities based on entropy-derived activations without having to retrain the model [154]. Finally, LayerSkip, uses self-speculative decoding and trains models with layer dropout and early exit loss, enabling tokens to be predicted from earlier layers and verified by later layers, thus accelerating inference while mitigating hallucinations [174].

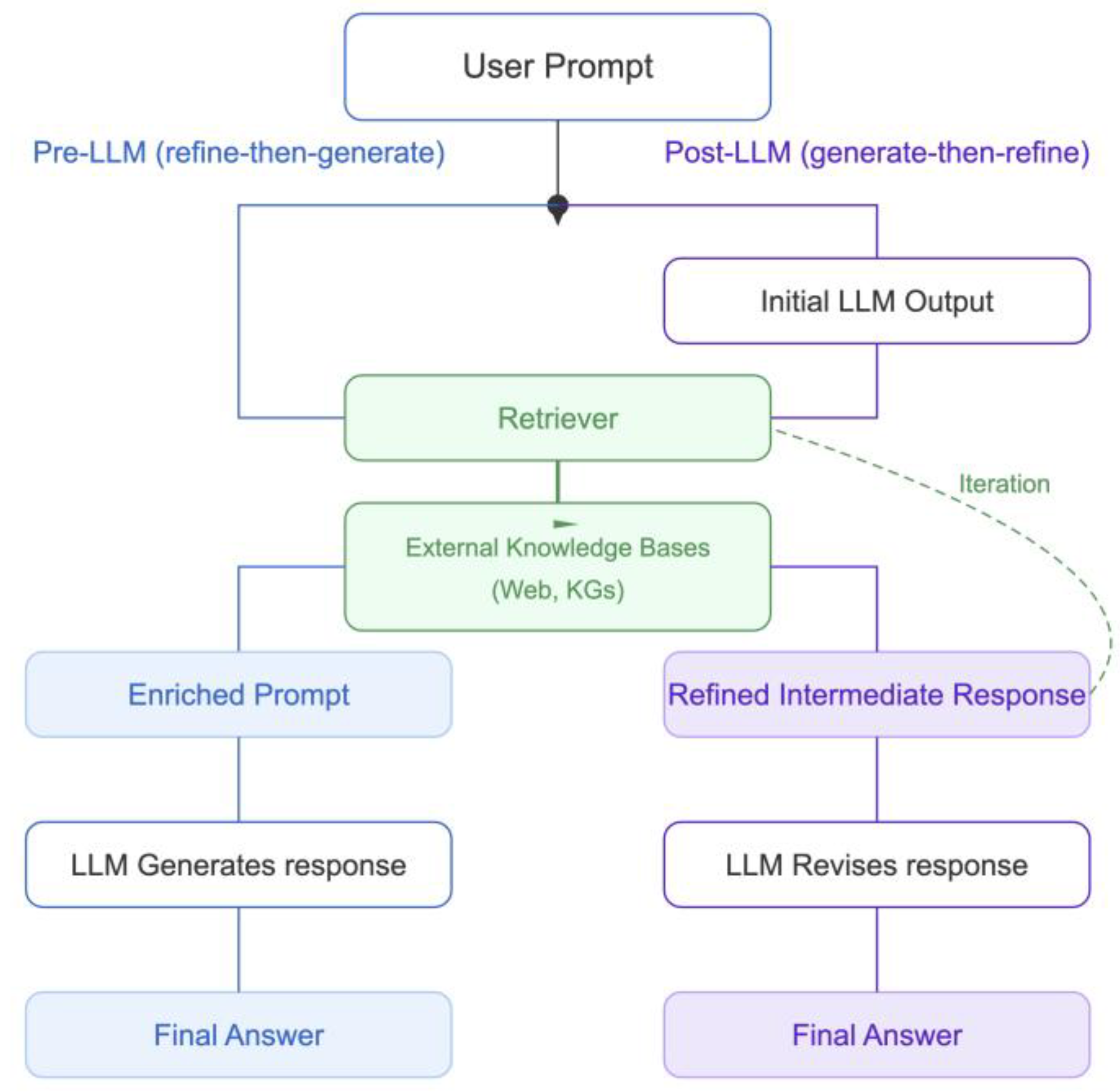

- RAG-based Decoding: RAG-based decoding strategies integrate external knowledge to enhance factual consistency and mitigate hallucinations [255,258]. For instance, REPLUG prepends a different retrieved document for every forward pass of the LLM and averages the probabilities from these individual passes, thus allowing the model to produce more accurate outputs by synthesizing information from multiple relevant contexts simultaneously [255]. Similarly, Retrieval in Decoder (RID) dynamically adjusts the decoding process based on the outcomes of the retrieval, allowing the model to adapt its generation based on the confidence and relevance of the retrieved information [258].

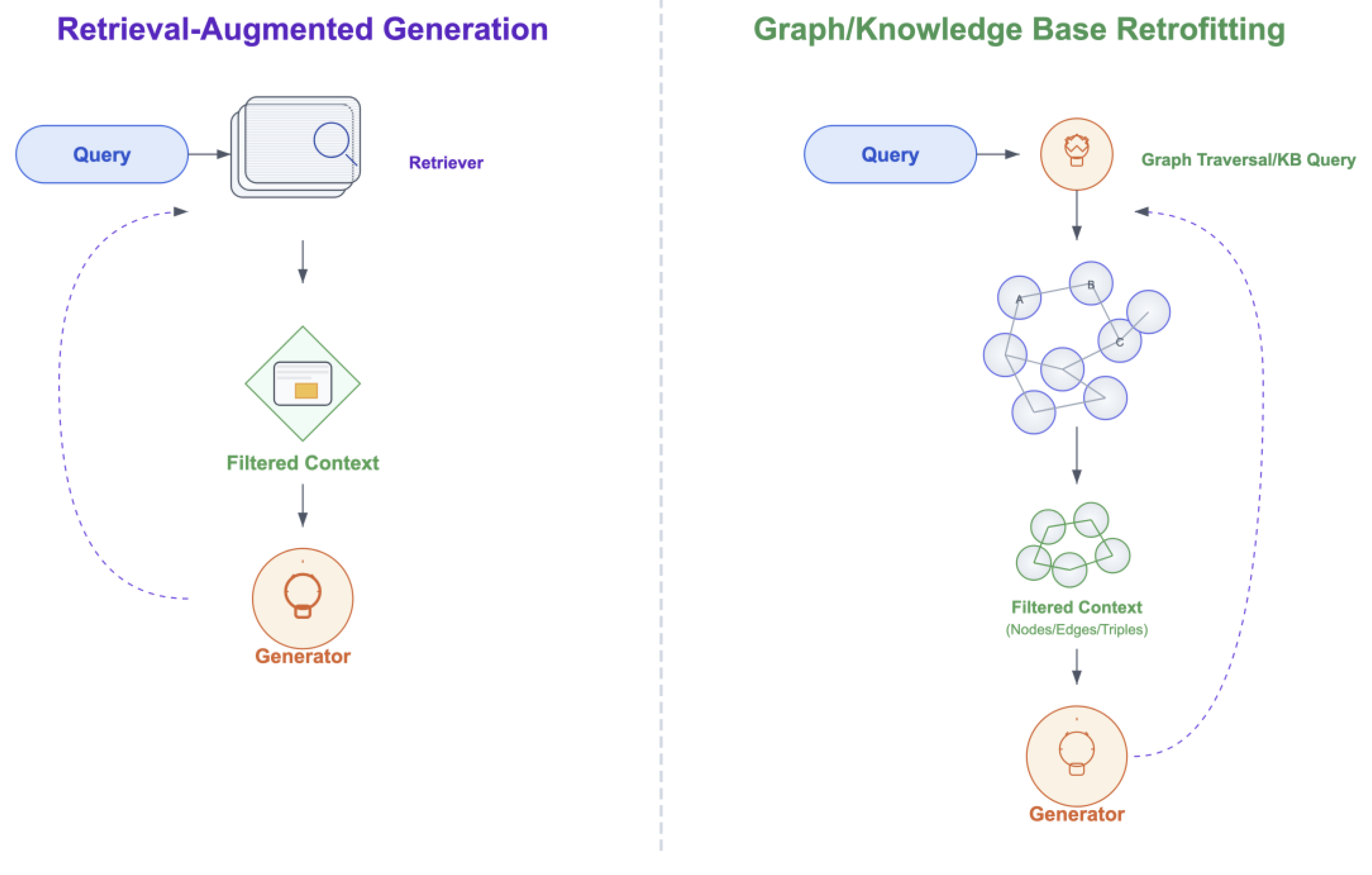

5.2.3. Retrieval-Augmented Generation

5.2.4. Knowledge Representation Approaches

5.2.5. Specialized Architectural Mechanisms for Enhanced Generation

5.3. Input / Prompt Optimization

5.3.1. Prompt Engineering

- In dataset creation and evaluation, prompt engineering has been used to generate and filter references used for inference and evaluation [37,51,142,143], systematically induce, detect, or elicit imitative falsehoods [26,100,112,126,132,148,179,315], and even create specific types of code hallucinations to test research methodologies [60].

- For confidence assessment and behavioral guidance, it has been used to elicit verbalized confidence, consistency, or uncertainty, and test or guide model behavior and alignment [48,84,86,87,144,145,159,230,232,235,267,277,290,313], reduce corpus-based social biases [270], extract and verify claims [251] as well as investigate failure cascades like hallucination snowballing [147].

- In knowledge integration scenarios it has been combined with retrieval modules or factual constraints [190,241,259,282], in agentic environments where prompts guide the generation of states, actions, and transitions [245], or the alignment process between queries and external knowledge bases [297], and even in the training process of a model where they are used to inject entity summaries and triplets [140]. Additionally, prompts have also been explored as explicit, language-based feedback signals in reinforcement learning settings, where natural language instructions are parsed and used to fine-tune policy decisions during training [305].

- scalability issues which arise from the number of intermediate tasks or their complexity [299],

- context dilution which demonstrates that prompts often fail when irrelevant context is retrieved, especially in RAG scenarios [190],

- lack of standardized prompting workflows which makes prompt engineering a significant trial and error task not only for end-users but also for NLP experts [326], hindering reliable mitigation, and

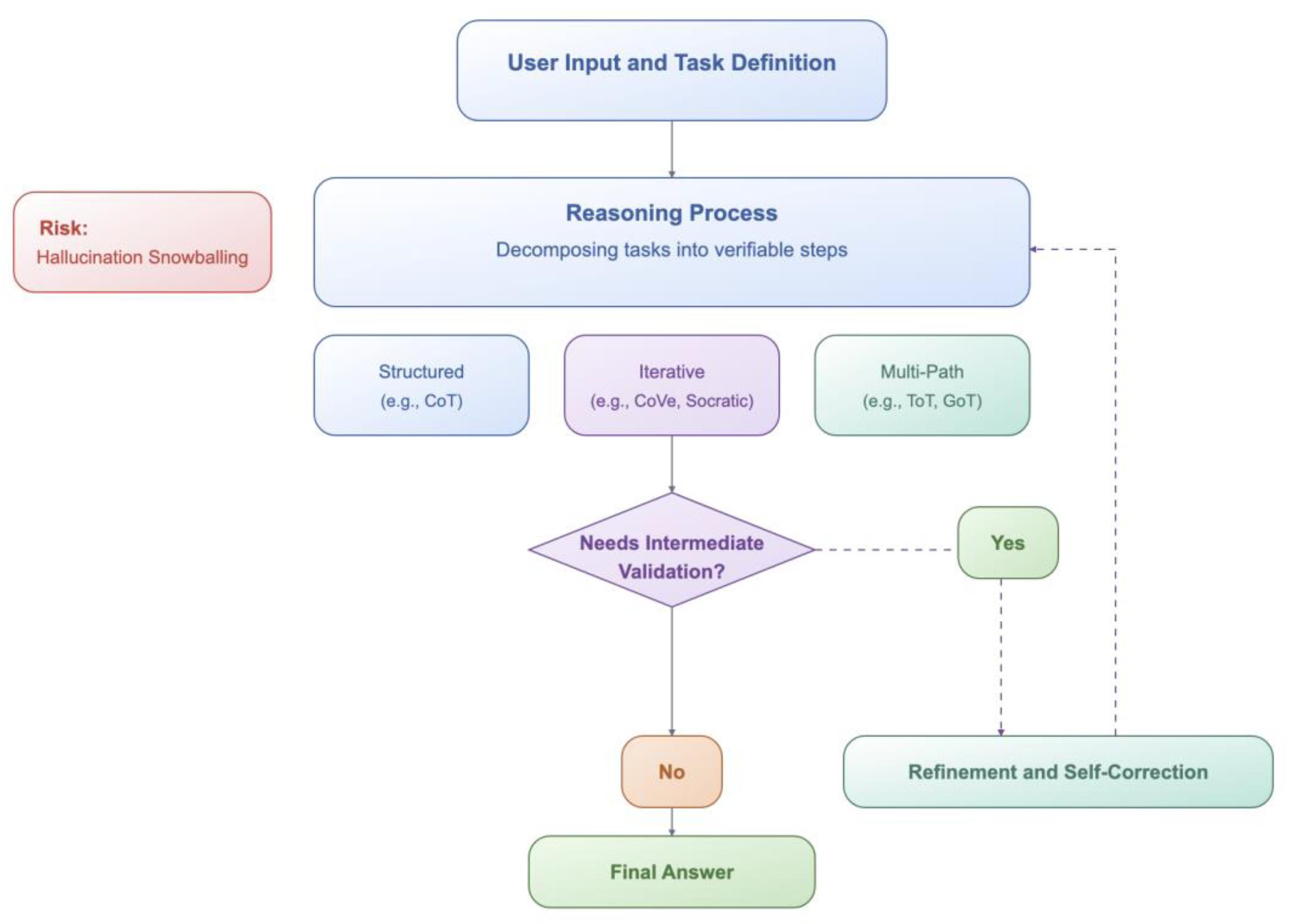

5.3.2. Structured or Iterative Reasoning Prompting

- Structured reasoning prompts modify the model’s behavior in a single forward pass: the model follows the request to enumerate steps in one shot, as there is typically no separate module that determines how and when to make these steps or whether to call external tools.

- Iterative reasoning, on the other hand, can further improve the generative capabilities of a model, by guiding it to decompose a task into a series of steps, each of which builds upon, refines, and supports previous steps.

- exploit the dialog capabilities of LLMs to detect logical inconsistencies by integrating deductive formal methods [75].

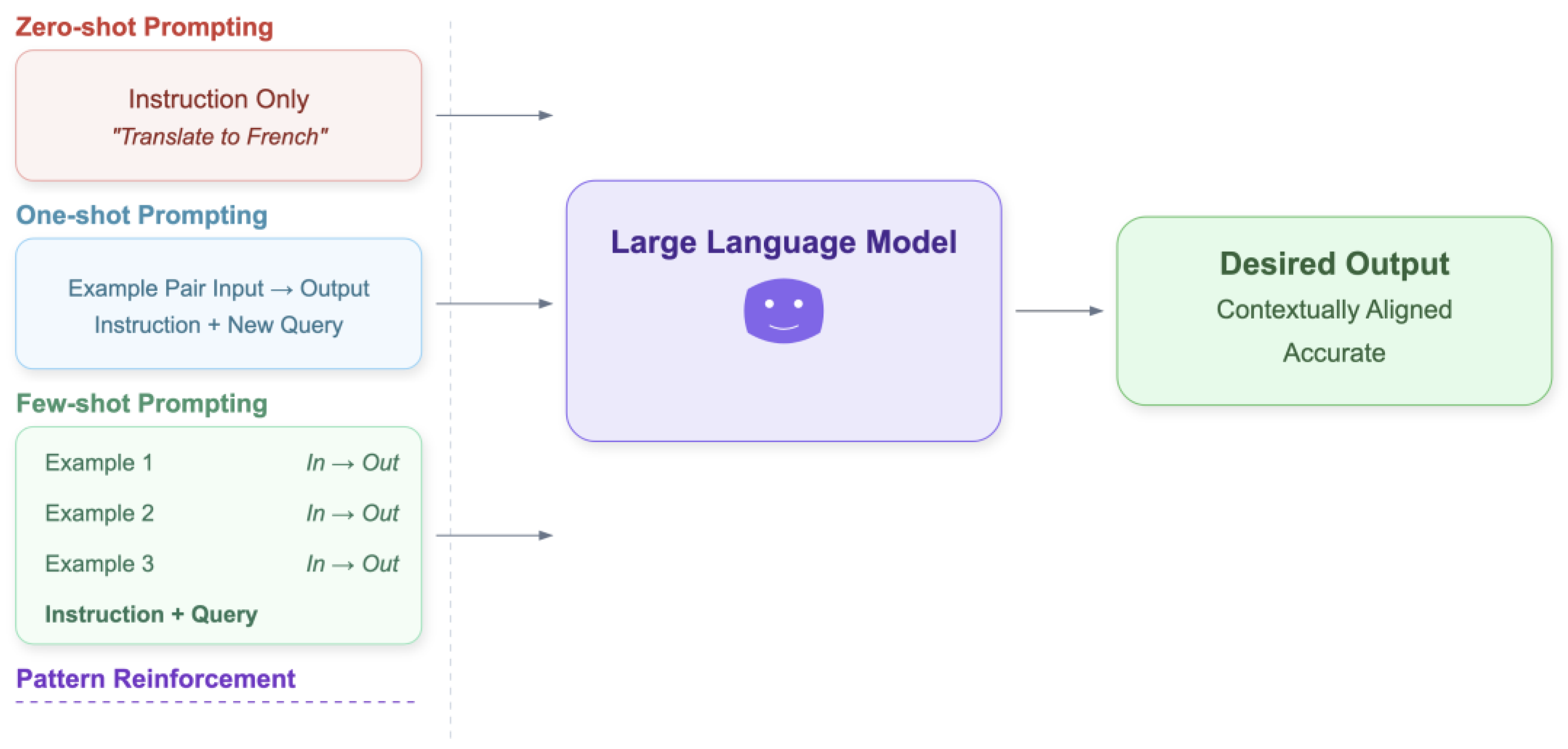

5.3.3. In-Context Prompting

- Pattern Reinforcement: By seeing multiple demonstrations, the model better aligns its response style and factual consistency with provided examples. For instance, Principle-Driven Self-Alignment provides 5 in-context exemplars alongside 16 human-written principles that guide the model by providing clear patterns for how it should comply with these principles, thus aligning its behavior and internal thoughts with the desired behavior demonstrated in the examples [230].

- Bias Reduction: Balanced example selection can minimize systematic biases, particularly in ambiguous queries [44,106] while few-shot examples have been used to calibrate GPT-3’s responses, demonstrating how different sets of balanced vs. biased prompts significantly influence downstream performance [232].

5.3.4. Context Optimization

5.3.5. System Prompt Design

5.4. Post-Generation Quality Control

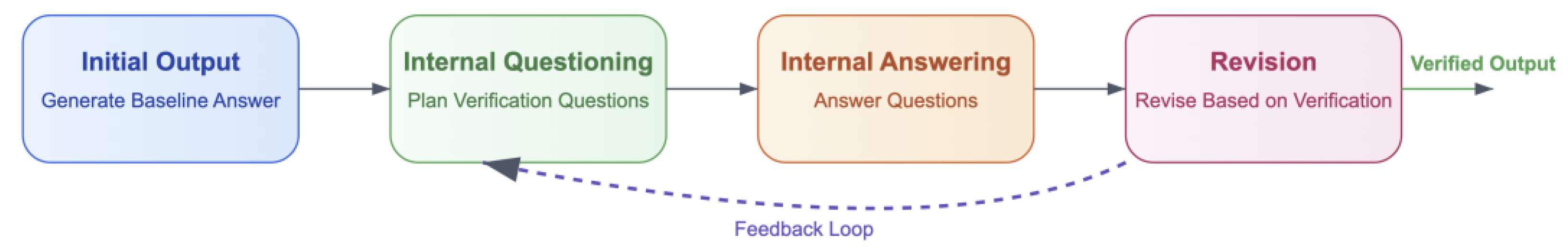

- Self-verification and Consistency Checking: Involves internal assessments of output quality, ensuring logical flow, and maintaining factual coherence within the generated content.

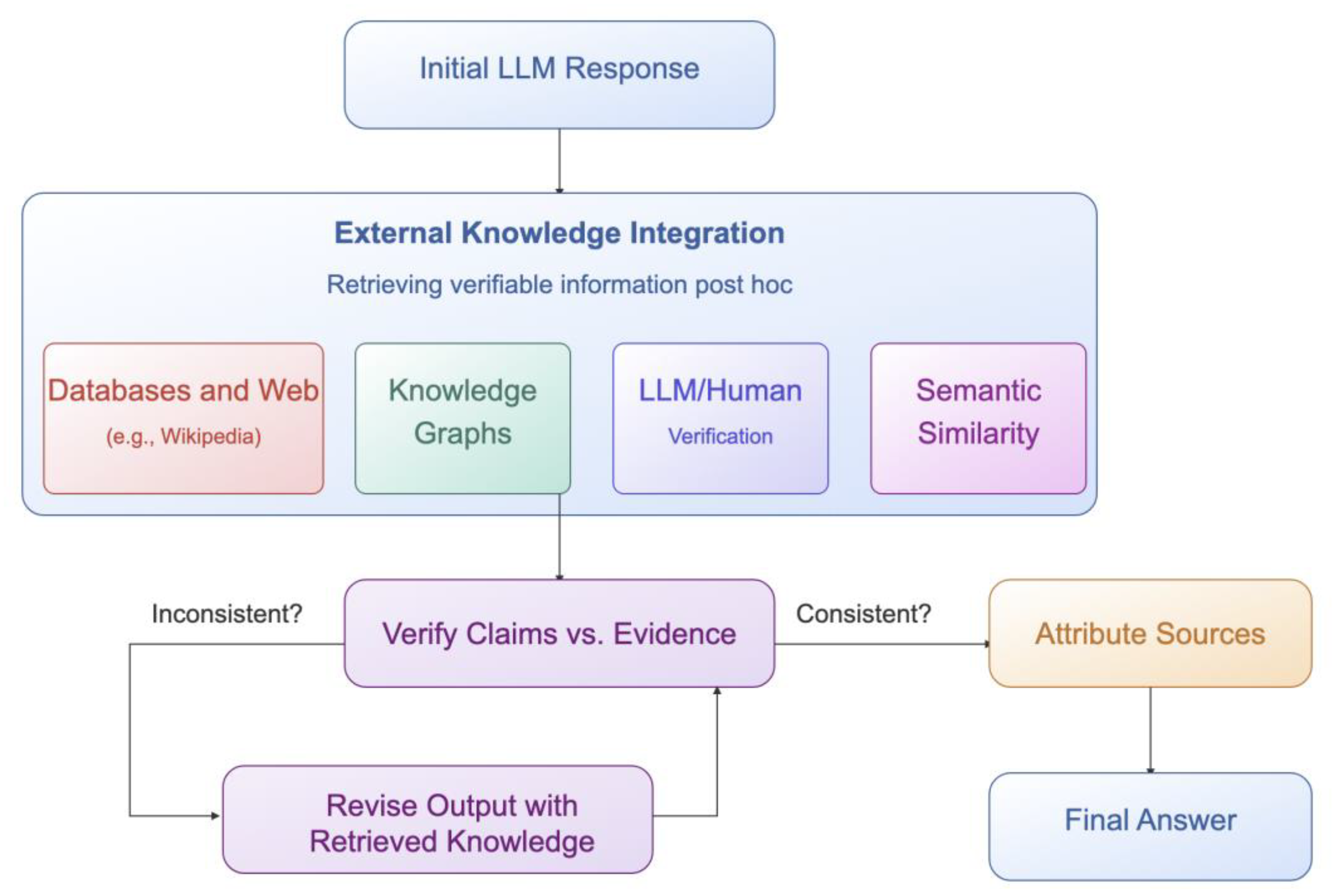

- External Fact-checking and Source Attribution: Validates information against outside authoritative sources or asks the model to explicitly name its sources.

-

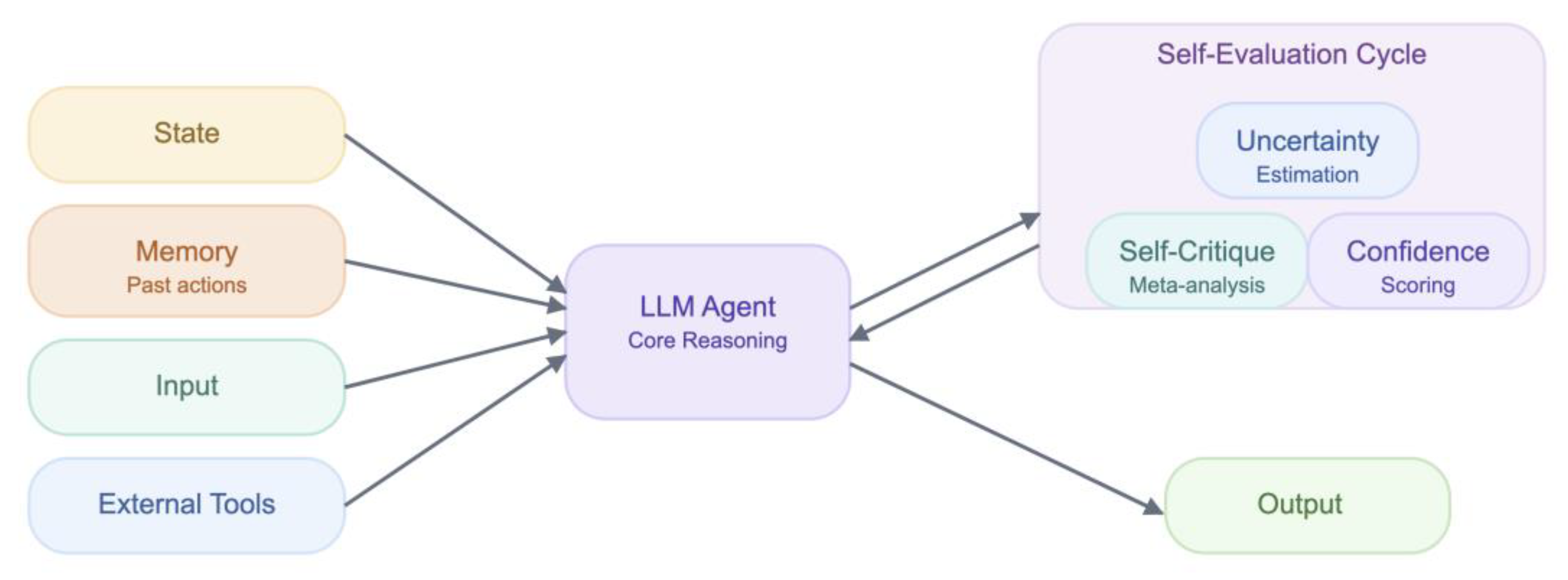

Reliability Quantification: a broader subcategory that encompasses:

- ○

- Uncertainty Estimation (quantifying the likelihood of claims) and

- ○

- Confidence Scoring (assigning an overall reliability score to the output).

- Output Refinement: Involves further shaping and iteratively polishing the generated text.

- Response Validation: Strictly focuses on confirming that the output meets specific, pre-defined criteria and constraints.

5.4.1. Self-Verification and Consistency Checking

5.4.2. External Fact-Checking

5.4.3. Uncertainty Estimation & Confidence Scoring

Uncertainty Estimation

- Entropy-based approaches: The Real-time Hallucination Detection method (RHD) in [203] also leverages entropy to detect output entities with low probability and high entropy, which are likely to be potential hallucinations. When RHD determines that the model is likely to generate unreliable text, it triggers a self-correction mechanism [203]. A similar mechanism Conditional Pointwise Mutual Information (CPMI) in [214], quantifies model uncertainty via token-level conditional entropy. Specifically, the method identifies hallucinated token generation as corresponding to high entropy states, where the model is most uncertain, thus confirming that uncertainty is a reliable signal [214]. INSIDE leverages the model’s internal states to directly measure uncertainty with the EigenScore metric, which represents the differential entropy in the sentence embedding space while a feature clipping method mitigates overconfident generations [156]. Uncertainty in [165] is measured with Pointwise Mutual Information (PMI) which quantifies overshadowing likelihood by identifying low-confidence conditions that are likely to be overshadowed. In this case, shifts in model confidence under controlled perturbations are measured by using the probability difference between p(y|x) and p(y|x′) which essentially serves as a method of uncertainty-based detection [165]. The concept of entropy is extended in a number of research papers to encompass semantics. For instance, in [82], the authors measure the model’s uncertainty over the meaning of its answers rather than just variations in specific words by using "semantic entropy," an entropy-based uncertainty estimator which involves generating multiple answers, clustering them by semantic meaning, and then computing the entropy of these clusters to quantify the model’s uncertainty [82]. Similarly, in [276] "semantic entropy probes (SEPs)" gauge the model’s uncertainty from the hidden states of a single generation, which is a more efficient approach than sampling multiple responses, log probabilities or naive entropy according to the authors [276]. In an Epistemic Neural Network (ENN) extracts hidden layer features from LLaMA-2, feeding them into a small MLP ENN trained on next-token prediction, whose outputs are combined with DoLa contrastive decoding logits. This hybrid approach improves uncertainty estimation by allowing the model to down-weight low-confidence generations [249]. Finally, in [314], the conventional wisdom that hallucinations are typically associated with low confidence is challenged with the introduction of Certain Hallucinations Overriding Known Evidence (CHOKE). Specifically, the researches use and evaluate three uncertainty metrics (semantic entropy, Token probability, Top-2 token probability gap), showing that hallucinations can occur with high certainty, even when the model “knows” the correct answer [314].

- Sampling: Sampling is a classic method for uncertainty estimation as exemplified in [113], where a model’s outputs are sampled multiple times and the variability in its output is used as a proxy for its uncertainty. Contrary to the confidence score being a simple, single-token probability, it is a numerical value that is derived from the resampling process, and it acts as a signal for verification and a reward in its reinforcement learning stage [113]. Similarly, sampling is also used in [274] where increasing divergence between sampled responses is an indicator of hallucinated content and uncertainty which the authors measure with various methods such as BERTScore and NLI [274]. Finally, the framework presented in [48] leverages three main components: sampling strategies to generate multiple responses, different prompting techniques to elicit the model’s uncertainty and aggregation techniques which are used to combine these multiple responses and their associated confidence scores to produce a final, calibrated confidence score [48].

- Monte Carlo methods: Fundamental uncertainty measures such as sequence log-probability and Monte-Carlo dropout dissimilarity are leveraged as key metrics to detect hallucinations and inform subsequent stages, such as refinement, detection, and re-ranking of the generated text, capturing the variability and confidence in its predictions [173]. In [245], reward estimation is based on the log probability of actions, effectively capturing how "confident" a model is about specific reasoning steps. While the authors do not explicitly term this as "uncertainty estimation," we believe that their approach overlaps significantly because the reward function evaluates the plausibility of reasoning steps. Specifically, the Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) uses these rewards to guide exploration, prioritizing reasoning paths with higher estimated rewards as the reward mechanism reflects the degree of trust in the reasoning trace generated by the LLM [245].

- Explicit Verbalization: The core method in [239] trains models to explicitly verbalize epistemic uncertainty by identifying "uncertain" vs. "certain" data. It uses supervised (prediction-ground truth mismatch) and unsupervised (entropy over generations) methods and subsequently evaluates model performance with Expected Calibration Error (ECE) and Average Precision (AP), enhancing models’ ability to express self-doubt about their knowledge. In a similar vein, SelfAware introduces a benchmark and method to assess a model’s self-knowledge by detecting when they should verbalize uncertainty in response to unanswerable questions [88]. Similarly, [288] fine-tunes GPT-3 to produce what the authors call "verbalized probability", which is essentially a direct expression of the model’s epistemic uncertainty. This teaches the model to be self-aware of its uncertainty, which is a "higher-order objective" that goes beyond the typical raw softmax-based confidence scoring. While we categorized [288] under Uncertainty Estimation, we do acknowledge that confidence scoring is a crucial component since it measures calibration of these scores using metrics such as mean square error (MSE) and mean absolute deviation (MAD). However, these scores are a direct outcome of the new verbalized probability method and not derived from existing logits [288].

- Semantic analysis: In [275], the authors propose semantic density to quantify uncertainty which measures similarity between a response and multiple completions in embedding space. Semantic density operates on a response-wise and not prompt-wise manner and doesn’t require model retraining, addressing key limitations of earlier uncertainty quantification methods (like semantic entropy or P(True)). While the authors consistently use the term “confidence” as a counterpart to “uncertainty”, and the final semantic density score is indeed a confidence indicator, yielding numerical scores in the range [0, 1] with provision for thresholding or filtering, we believe that this scoring is treated as the outcome of the proposed uncertainty metric [275]. Semantic analysis and logit-derived, token-level probabilistic measures are combined in [282] to calculate a confidence score for each atomic unit of an answer. This confidence is then integrated with textual entailment probabilities to produce a refined score to identify hallucinated spans. Although the authors use confidence scores that support thresholding, and consistently use the term "confidence," these confidence scores are used as part of a larger framework to detect model-generated hallucinations and thus we believe that confidence scoring is a means to an end, and that end is uncertainty estimation in [282].

- Training approaches: [280] explicitly links hard labels to overconfidence and proposes soft labels as a means of introducing uncertainty-aware supervision. This aligns with the theme of uncertainty estimation because their training objective is restructured to reflect model confidence calibration. They also evaluate overconfidence by plotting the NLL of incorrect answers, and argue that fine-tuning with soft labels reduces misplaced certainty—one of the major causes of hallucination [280]. The core contribution in [281], is a method to mitigate hallucinations by using "smoothed soft labels" as opposed to traditional hard labels that encourage overconfidence and disregard the inherent uncertainty in natural language. By introducing "uncertainty-aware supervision" through knowledge distillation, the student model learns from a more calibrated probability distribution. This approach aligns with the principle of maximum entropy and is designed to make models less overconfident and more reliable by improving factual grounding. This aligns with the theme of uncertainty estimation, because their training objective is restructured to reflect model confidence calibration. They also evaluate overconfidence by plotting the NLL of incorrect answers and argue that fine-tuning with soft labels reduces misplaced certainty—one of the major causes of hallucination [281].

- Composite methods: In [214], the authors utilize epistemic uncertainty to inform a modified beam search algorithm which prioritizes outputs with lower uncertainty, thus leading the model to reduce the generation of incorrect or nonexistent facts. In [96], a reference-free, uncertainty-based method uses a proxy model to calculate token and sentence-level hallucination scores based on uncertainty metrics. These metrics are then enhanced by focusing on keywords, propagating uncertainty through attention weights, and correcting token probabilities based on entity type and frequency to address over-confidence and under-confidence issues. Finally, in [4] the authors use the attention mechanism as a self-knowledge probe. Specifically, they design an uncertainty estimation head, which is essentially a lightweight attention head that relies on attention-derived features such as token-to-token attention maps and lookback ratios, serving as indicators of hallucination likelihood.

Confidence Scoring

5.4.4. Output Refinement

- RAG-based methods and Web searches, where external sources like documents or the web are directly used to retrieve information for output refinement. For instance, the Corrective Retrieval-Augmented Generation (CRAG) framework employs a lightweight retrieval evaluator and a decompose-then-recompose algorithm to assess the relevance of retrieved documents to a given query [69]. Similarly, EVER validates model outputs and iteratively rectifies hallucinations by revising intrinsic errors so that they align with factually verified content or re-formulates extrinsic hallucinations while warning users accordingly [102] while FAVA refines model outputs by performing fine-grained hallucination detection and editing at the span level. Specifically, it identifies specific segments of text, or "spans," that contain factual inaccuracies or subjective content and suggests edits by marking the incorrect span for deletion and providing a corrected span to replace it [112].

- Structured Knowledge Sources: These approaches integrate and reason over structured external data such as knowledge graphs or formal verification systems. For instance, [202] leverages the probabilistic inference capacity of Graph Neural Networks (GNN) to refine model outputs by processing relational data alongside textual information while [260] employs a re-ranking mechanism to refine and enhance conversational reasoning by leveraging walks over knowledge sub-graphs. Similarly, Neural Path Hunter (NPH) uses a generate-then-refine strategy that post-processes generated dialogue responses by detecting hallucinated entity mentions and refining those mentions using a KG query to replace incorrect entities with faithful ones [217]. During the revision phase of FLEEK, a fact revision module suggests corrections for dubious fact triplets based on verified evidence from Knowledge Graphs or the Web [116] while [75] integrates deductive formal methods with the dialectic capabilities of inductive LLMs to detect hallucinations through logical tests.

- External Feedback and verification: These methods rely on external signals, human feedback, or verified external knowledge to guide the refinement process. Using the emergent abilities of CoT reasoning and few-shot prompting, CRITIC revises hallucinated or incorrect outputs based on external feedback that includes free-form question answering, mathematical reasoning, or toxicity reduction [70]. Chain of Knowledge (CoK) uses a three-stage process comprising reasoning preparation, dynamic knowledge adapting, and answer consolidation to refine model outputs. If a majority consensus is not reached, CoK corrects the rationales by integrating knowledge from identified domains, heterogeneous sources, including structured and unstructured data, to gather supporting knowledge [52]. Model outputs are refined in [324] through the Verify-and-Edit framework that specifically post-edits Chain of Thought (CoT) reasoning chains. The process begins with the language model generating an initial response and its corresponding CoT as an intermediate artifact. Subsequently, the framework generates "verifying questions" and retrieves relevant external knowledge to answer them. The original CoT and the newly retrieved external facts are then used to re-adjust the generated output, correcting any unverified or factually incorrect information [324]. The Self-correction based on External Knowledge (SEK) module presented in [203] is a key component of the DRAD framework designed to mitigate hallucinations in LLMs. When the Real-time Hallucination Detection (RHD) module identifies a potential hallucination, the SEK module formulates a query using the context around the detected error and retrieves relevant external knowledge from an external corpus. Finally, the LLM truncates its original output at the hallucination point and regenerates the content by leveraging the retrieved external knowledge, thereby correcting the factual inaccuracies [203].

- Filtering Based on External Grounding: These techniques filter outputs by comparing them against external documents or ground truth. For instance, the HAR (Hallucination Augmented Recitations) pipeline presented in [126], employs Factuality Filtering and Attribution Filtering to extract factual answers while simultaneously removing any question, document, and answer pairs where the answer is not properly grounded in the provided document [126]. HaluEval-Wild uses an adversarial filtering process, manual verification of hallucination-prone queries, and selection of challenging examples so as to refine the model outputs and ensure the dataset includes only relevant, challenging cases for evaluation [142].

- Agent-Based Interaction with External Context: These involve agents that interact with external environments, systems, or receive structured external feedback for refinement. For instance, the mitigation agent in [51] is designed to refine and improve the output by interpreting an Open Voice Network (OVON) JSON message generated by the second-level agent. This JSON message contains crucial information, including the estimated hallucination level and detailed reasons for potential hallucinations, which guides the third agent’s refinement process [132].

- Model Tuning/Refinement with External Knowledge: Methods that explicitly use external knowledge during their training or refinement phase to improve model outputs. In [166], methods like refusal tuning, open-book tuning, and discard tuning are leveraged to refine the outputs of the model, thus ensuring consistency with external and intrinsic knowledge. The PURR model refines its outputs through a process akin to conditional denoising by learning to correct faux hallucinations—intentionally corrupted text that has been used to fine tune an LLM. The refinement happens as PURR denoises these corruptions by incorporating relevant evidence, resulting in more accurate and attributable outputs [235].

- Iterative self-correction, where approaches such as [252] leverage an adaptive, prompt-driven iterative framework for defect analysis, guided optimization, and response comparison using prompt-based voting. Output refinement is accomplished in [207] by employing Self-Checks where the model rephrases its own prompts or poses related questions to itself for internal consistency. Additionally, [273] uses in-context prompting to incorporate the model’s self-generated feedback for iterative self-correction while [303] focuses on rewriting and improving answers to enhance factuality, consistency, and entailment through Self-Reflection. Furthermore, [269] utilizes a prompting-based framework for the LLM to identify and adjust self-contradictions within its generated text and finally, in the Tree of Thoughts (ToT) framework [309], structured exploration is guided by search algorithms like Breadth-First Search or Depth-First Search thus helping the model perform self-evaluation at various stages to refine its reasoning path.

- Self-Regulation during Generation/Decoding, where the model re-adjusts its own output or decision-making process in real-time during generation. For instance, the Self-highlighted Hesitation method (SH2) presented in [277] refines the model’s output by iteratively recalibrating the token probabilities through hesitation and contrastive decoding, while the Hypothesis Verification Model (HVM) estimates faithfulness scores during decoding, refining the output at each step [302].

- Self-Generated Data for Improvement, where the LLM generates data or instructions which are subsequently used to finetune itself. For instance, the Self-Instruct framework bootstraps off the LLM’s own generations to create a diverse set of instructions for finetuning while in WizardLM such instructions are evolved and iteratively refined through elimination evolving to ensure a diverse dataset for instruction fine-tuning.

- Model-based techniques and tuning: LaMDA employs a generate-then-rerank pipeline that explicitly filters and ranks candidate responses based on safety and quality metrics. The discriminators are used to evaluate these attributes and the best-ranked response is selected for output [168]. Dehallucinator overwrites flagged translations by generating and scoring Monte Carlo dropout hypotheses, scoring them with a specific measure, and selecting the highest-scoring translation as the final candidate [189]. In [95], two models are responsible for generating the initial output and evaluating this output for inconsistencies using token-level confidence scoring and probabilistic anomaly detection. A feedback mechanism iteratively refines the output by flagging problematic sections and dynamically re-adjusting its internal parameters. Structured Comparative reasoning (SC2) combines approximate inference and pairwise comparison to select the most consistent structured representation from a number of intermediate representations [228]. In [48] techniques like sampling multiple responses and aggregating them for consistency aim to refine the model’s output by filtering for coherence and reliability while the Verbose Cloning stage in [230] uses carefully constructed prompts and context distillation to refine outputs by making them more comprehensive and detailed, addressing issues with overly brief or indirect responses. The central idea in [121] is to iteratively refine sequences generated by a base model using a separately trained corrector model. This process is based on value-improving triplets of the form (input, hypothesis, correction) which are examples of mapping a hypothesis to a higher-valued correction thus resulting in significant improvements in math program synthesis, lexical constrained generation and toxicity removal [121]. Finally, the MoE architecture presented in [247] uses majority voting to filter out erroneous responses and refines outputs by combining expert contributions, ensuring only consensus-backed outputs are used and that a more accurate and polished response is generated.

5.4.5. Response Validation

5.5. Interpretability and Diagnostic Approaches

5.5.1. Internal State Probing

- Detection — employing anomaly detection and linguistic analysis.

- Mitigation — suggesting cross-referencing with structured knowledge bases [32].

5.5.2. Neuron Activation and Layer Analysis

5.5.3. Attribution-Based Diagnostics

5.6. Agent-Based Orchestration

5.6.1. Reflexive / Self-Reflective Agents

5.6.2. Modular and Multi-Agent Architectures

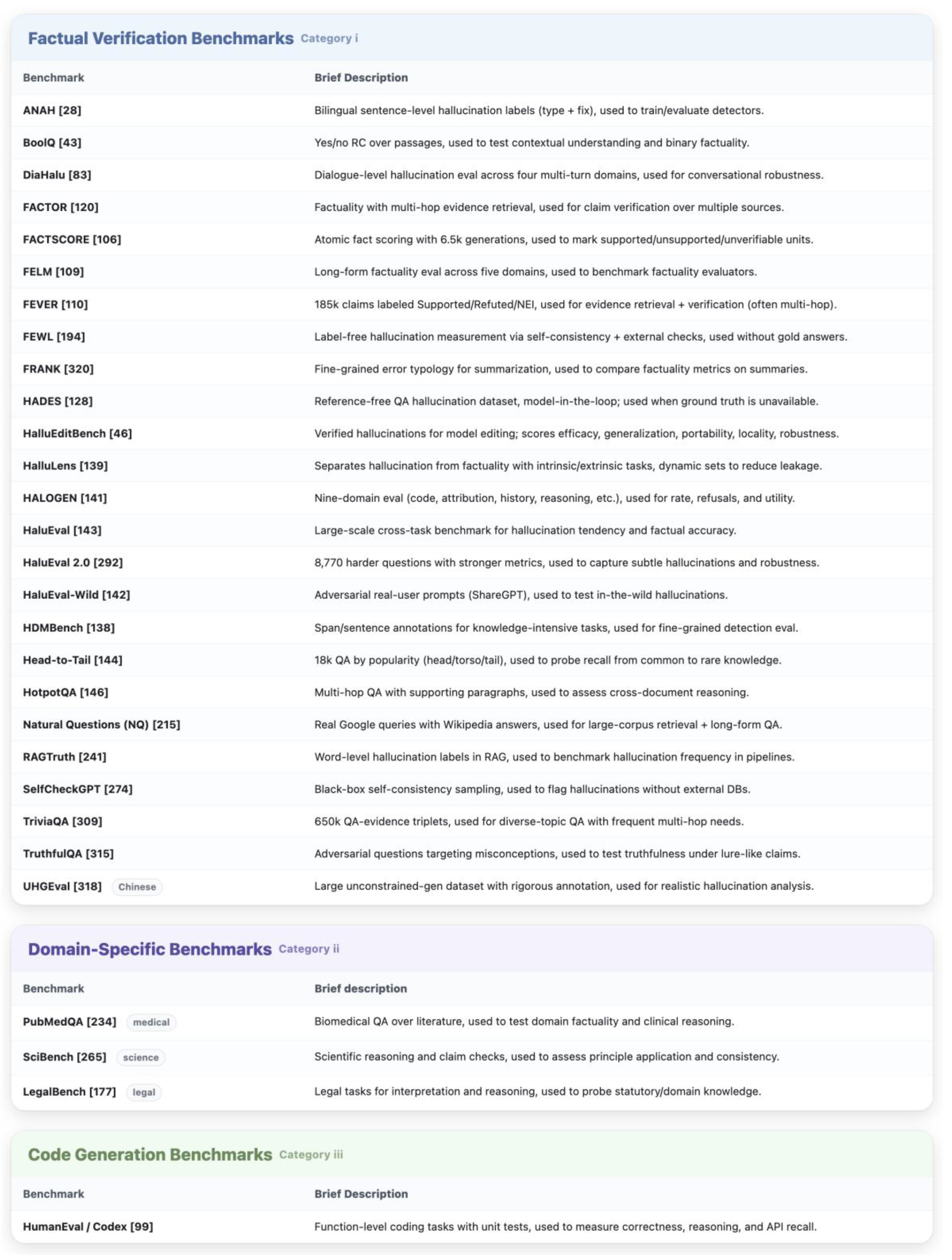

6. Benchmarks for Evaluating Hallucinations

-

Factual Verification Benchmarks: These benchmarks focus on assessing the factual accuracy of LLM outputs by comparing them against established ground truth.

- ○

- ANAH is a bilingual dataset for fine-grained hallucination annotation in large language models, providing sentence-level annotations for hallucination type and correction [28]

- ○

- BoolQ: A question answering dataset which focuses on yes/no questions, requiring models to understand the context and before deciding [43].

- ○

- DiaHalu is introduced as the first dialogue-level hallucination evaluation benchmark for LLMs. This dataset aims to address the limitations of existing benchmarks that often focus solely on factual hallucinations by covering four multi-turn dialogue domains: knowledge-grounded, task-oriented, chit-chat, and reasoning [83].

- ○

- FACTOR (Factuality Assessment Corpus for Text and Reasoning) is a benchmark designed to evaluate the factuality of language models, particularly their ability to perform multi-hop reasoning and retrieve supporting evidence [120]. This benchmark focuses on assessing whether a model’s generated text aligns with verifiable facts, demanding not only information retrieval capabilities but also the ability to reason over multiple pieces of evidence to validate claims.

- ○

- FACTSCORE [106] contributes a fine-grained, atomic-level metric designed to assess the factual precision of long-form text generation. Accompanied by a large benchmark of 6,500 model generations from 13 LLMs, FACTSCORE enables comparisons across models by distinguishing supported, unsupported, and unverifiable statements within a single output.

- ○

- FELM (Factuality Evaluation of Large Language Models) is a benchmark dataset designed to evaluate the ability of factuality evaluators to detect errors in LLM-generated text. FELM spans five domains—world knowledge, science/tech, math, reasoning, and writing/recommendation—and is primarily used to benchmark factuality detection methods for long-form LLM outputs [109].

- ○

- FEVER (Fact Extraction and Verification): FEVER is a dataset consisting of 185,445 claims that are classified as "Supported", "Refuted" or "NotEnoughInfo" [110]. The researchers argue that FEVER is a challenging testbed, since some claims require multi-hop reasoning and information retrieval, and can be used to assess the ability of models to not only retrieve relevant evidence but also to determine the veracity of claims based on that evidence.

- ○

- FEWL (Factuality Evaluation Without Labels): FEWL is a methodology for measuring and reducing hallucinations in large language models without relying on gold-standard answers [194]. This approach focuses on evaluating the factual consistency of generated text by using a combination of techniques, including self-consistency checking and external knowledge verification, to identify potential hallucinations.

- ○

- The FRANK benchmark introduces a typology of factual errors grounded in linguistic theory to assess abstractive summarization models. It annotates summaries from nine systems using fine-grained error categories, providing a dataset that enables the evaluation and comparison of factuality metrics [320].

- ○

- HADES (HAllucination DEtection dataset) is a reference-free annotated dataset specifically designed for hallucination detection in QA tasks without requiring ground-truth references, which is particularly useful for free-form text generation where such references may not be available. The creation of HADES involved perturbing text segments from English Wikipedia and then human-annotating them through a "model-in-the-loop" procedure to identify hallucinations [128].

- ○

- HalluEditBench is a dataset comprised of verified hallucinations across multiple domains and topics and measures editing performance across Efficacy, Generalization, Portability, Locality, and Robustness [46].

- ○

- HalluLens is a comprehensive benchmark specifically designed for evaluating hallucinations in large language models, distinguishing them from factuality benchmarks [139]. HalluLens includes both intrinsic and extrinsic hallucination tasks and dynamically generates test sets to reduce data leakage. The authors argue that factuality benchmarks like TruthfulQA [315] and HaluEval 2.0 [292] often conflate factual correctness with hallucination, although hallucinations are more about consistency with training data or user input rather than absolute truth. HalluLens, therefore, offers a more precise and task-aligned tool for hallucination detection.

- ○

- HALOGEN (Hallucinations of Generative Models) is a hallucination benchmark designed to evaluate LLM outputs across nine domains including programming, scientific attribution, summarization, biographies, historical events, and reasoning tasks. HALOGEN is used to measure hallucination frequency, refusal behavior, and utility scores for generative LLMs, providing insights into error types and their potential sources in pretraining data [141].

- ○

- HaluEval: HaluEval is a large-scale benchmark for the evaluation of hallucination tendencies of large language models across diverse tasks and domains [143]. It assesses models on their ability to generate factually accurate content and identify hallucinated information. The benchmark includes multiple datasets covering various factual verification scenarios, making it a comprehensive tool for evaluating hallucination detection and mitigation performance.

- ○

- HaluEval 2.0: HaluEval 2.0 is an enhanced version of the original HaluEval benchmark, containing 8,770 questions from such diverse domains as biomedicine, finance, science and education, offering wider coverage, more rigorous evaluation metrics for assessing factuality hallucinations in LLMs as well as challenging tasks to better capture subtle hallucination patterns and measure model robustness [292].

- ○

- HaluEval-Wild: HaluEval-Wild is a benchmark specifically designed to evaluate hallucinations within dynamic, real-world user interactions as opposed to other benchmarks that focus on controlled NLP tasks like question answering or summarization [142]. It is curated using challenging, and adversarially filtered queries from the ShareGPT dataset. These queries are categorized into five types to enable fine-grained hallucination analysis.

- ○

- HDMBench is a benchmark designed for hallucination detection across diverse knowledge-intensive tasks [138]. It includes span-level and sentence-level annotations, covering hallucinations grounded in both context and common knowledge. HDMBench enables the fine-grained evaluation of detection models, supporting future research on factuality by providing unified evaluation protocols and high-quality, manually validated annotations across multiple domains.

- ○

- Head-to-Tail: Head-to-Tail delves into the nuances of factual recall by categorizing information based on popularity [144]. It consists of 18,000 question-answer pairs and segments knowledge into "head" (most popular), "torso" (moderately popular), and "tail" (least popular) categories, mirroring the distribution of information in knowledge graphs.

- ○

- HotpotQA: HotpotQA evaluates multi-hop reasoning and information retrieval capabilities, requiring models to synthesize information from multiple documents to answer complex questions and it has proven to be particularly useful for evaluating factual consistency across multiple sources [146].

- ○

- NQ (Natural Questions): NQ is a large-scale dataset of real questions asked by users on Google, paired with corresponding long-form answers from Wikipedia [215]. It tests the ability to retrieve and understand information from a large corpus.

- ○

- RAGTruth is a dataset tailored for analyzing word-level hallucinations within standard RAG frameworks for LLM applications. It comprises nearly 18,000 naturally generated responses from various LLMs that can also be used to benchmark hallucination frequencies [241].

- ○

- SelfCheckGPT is a zero-resource, black-box benchmark for hallucination detection. It assesses model consistency by sampling multiple responses and measuring their similarity, without needing external databases or model internals [274].

- ○

- TriviaQA is a large-scale question-answering dataset that contains over 650,000 question-answer-evidence triplets that were created by combining trivia questions from various web sources with supporting evidence documents automatically gathered from Wikipedia and web search results [309]. The questions cover a diverse range of topics with many of those questions requiring multi-hop reasoning or the integration of information from multiple sources in order to generate a correct answer.

- ○

- TruthfulQA: TruthfulQA is a benchmark designed to assess the capability of LLMs in distinguishing between truthful and false statements, particularly those crafted to be adversarial or misleading [315].

- ○

- The UHGEval benchmark offers a large-scale, Chinese-language dataset for evaluating hallucinations under unconstrained generation settings. Unlike prior constrained or synthetic benchmarks, UHGEval captures naturally occurring hallucinations from five LLMs and applies a rigorous annotation pipeline, making it a more realistic and fine-grained resource for factuality evaluation [318].

-

Domain-Specific Benchmarks: These benchmarks target specific domains, testing the model’s knowledge and reasoning abilities within those areas.

- ○

- PubMedQA: This benchmark focuses on medical question answering, evaluating the accuracy and reliability of LLMs in the medical domain [234].

- ○

- SciBench: This benchmark verifies scientific reasoning and claim consistency, assessing the ability of LLMs to understand and apply scientific principles [265].

- ○

- LegalBench: This benchmark examines legal reasoning and interpretation, evaluating the performance of LLMs on legal tasks [177].

- Code Generation Benchmarks (e.g., HumanEval, Codex): These benchmarks assess the ability of LLMs to generate correct and functional code, which requires both factual accuracy and logical reasoning [99].

7. Practical Implications

- Keep humans in the loop with role clarity: Use Self-Reflection and external fact-checking pipelines to route low-confidence or conflicting outputs to a designated reviewer; require dual sign-off for irreversible actions when sources disagree.

8. Challenges

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Our Taxonomy Presented in Categories, Subcategories and Associated Papers

Appendix B. Summary Table of Benchmarks Used in Hallucination Detection and Mitigation

Appendix C. Hallucination Mitigation Subcategories Comparison Table

Glossary

- A

- ActLCD — Active Layer-Contrastive Decoding — Decoding that contrasts intermediate layers to steer token selection toward more factual continuations.

- Activation Decoding — Constrained decoding that adjusts next-token probabilities using activation/uncertainty signals to suppress hallucinations.

- AFHN — Adversarial Feature Hallucination Networks — Adversarial training to produce features and examples that stress models and reduce hallucinations.

- AggTruth — Attention aggregation across heads/layers to flag unsupported spans and improve factual consistency checks.

- ALIGNed-LLM — Aligns external knowledge (e.g., KG/entity embeddings) with the model’s representation space to ground generations.

- ALTI+ — Attribution method that quantifies how much each input token contributes to generated tokens for interpretability/factuality analysis.

- ANAH — Bilingual hallucination dataset with sentence-level annotations and suggested corrections.

- ATF — Adaptive Token Fusion — Merges redundant/similar tokens early to retain meaning while reducing noise and hallucination risk.

- AutoHall — Automatic pipeline to synthesize, detect, and evaluate hallucinations for training and benchmarking.

- AutoRAG-LoRA — Lightweight LoRA adaptation to better couple retrieval and generation in RAG systems.

- B

- BERTScore — Semantic similarity metric using contextual embeddings to evaluate generated text.

- BLEU — N-gram overlap metric; useful for surface similarity but not a direct measure of factuality.

- BoolQ — Yes/no question-answering dataset often used in factuality experiments.

- C

- CCL-XCoT — Cross-lingual transfer of Chain of Thought traces to improve reasoning and reduce hallucinations across languages.

- CD — Contrastive Decoding — Penalizes tokens favored by a weaker/contrast model to filter implausible continuations.

- Chain of Knowledge (CoK) — Grounds reasoning by explicitly incorporating external knowledge into intermediate steps.

- Chain of NLI (CoNLI) — Cascaded entailment checks over partial outputs to prune unsupported content.

- Chain of Thought (CoT) — Prompting that elicits step-by-step reasoning before the final answer.

- Chain of Verification (CoVe) — Contextualized word embeddings pre-trained on translation, used for stronger semantic representations.

- COMET-QE — Reference-free MT quality estimation used as a proxy signal for consistency.

- Conditional Pointwise Mutual Information (CPMI) — Decoding re-scoring that rewards tokens better supported by the source/context.

- Confident Decoding — Incorporates uncertainty estimates into beam/nucleus procedures to favor low-uncertainty continuations.

- CPM — Conditional Entropy Mechanism — Uses token-level entropy to detect and avoid uncertain/hallucination-prone outputs.

- CPO — Contrastive Preference Optimization — Preference optimization that uses contrastive signals to align outputs with faithful behavior.

- CRAG — Corrective Retrieval-Augmented Generation — Adds corrective/revision steps atop RAG to fix unsupported claims.

- CRITIC — A verify-and-edit framework where a “critic” process checks claims against evidence and proposes fixes.

- Critic-driven Decoding — Decoding guided by a trained critic/verifier that down-weights unsupported next tokens.

- D

- D&Q — Decompose-and-Query — Decomposes a question into sub-questions and retrieves evidence for each before answering.

- DeCoRe — Decoding by Contrasting Retrieval Heads — Contrasts retrieval-conditioned signals to suppress ungrounded tokens.

- Dehallucinator — Detect-then-rewrite approach that edits hallucinated spans into grounded alternatives.

- Delta — Compares outputs under masked vs. full context to detect and penalize hallucination-prone continuations.

- DiaHalu — Dialogue-level hallucination benchmark covering multiple multi-turn domains.

- DoLa — Decoding by Contrasting Layers — Uses differences between early vs. late layer logits to promote factual signals.

- DPO — Direct Preference Optimization — RL-free preference tuning that directly optimizes for chosen responses.

- DRAD — Decoding with Retrieval-Augmented Drafts — Uses retrieved drafts/evidence to guide decoding away from unsupported text.

- DreamCatcher — Detects and corrects hallucinations by cross-checking outputs against external evidence/tools.

- DrHall — Lightweight, fast hallucination detection targeted at real-time scenarios.

- E

- EigenScore — Uncertainty/factuality signal derived from the spectrum of hidden-state representations.

- EntailR — Entailment-based verifier used to check whether generated claims follow from retrieved evidence.

- EVER — Evidence-based verification/rectification that validates claims and proposes fixes during/after generation.

- F

- — Faith Finetuning — Direct finetuning objective to increase faithfulness of generations.

- Faithful Finetuning — Finetuning strategies that explicitly optimize for verifiable, source-supported outputs.

- FacTool — Tool-augmented factuality checking that extracts claims and verifies them against sources.

- FactPEGASUS — Summarization variant emphasizing factual consistency with the source document.

- FactRAG — RAG design focused on retrieving and citing evidence that supports each claim.

- FACTOR — Benchmark emphasizing multi-hop factuality and evidence aggregation.

- FAVA — Corrupt-and-denoise training pipeline to teach models to correct fabricated content.

- FELM — Benchmark for evaluating factuality evaluators on long-form outputs.

- FEVER — Large-scale fact verification dataset (Supported/Refuted/Not Enough Info).

- FG-PRM — Fine-Grained Process Reward Model — Process-level reward modeling for stepwise supervision of reasoning.

- FRANK — Fine-grained factual error taxonomy and benchmark for summarization.

- FreshLLMs — Uses live retrieval/search refresh to reduce outdated or stale knowledge.

- FActScore / FACTSCORE — Atomic, claim-level factuality scoring/benchmark for long-form text.

- G

- GAN — Generative Adversarial Network — Adversarial training framework used to stress and correct model behaviors.

- GAT — Graph Attention Network — Graph neural network with attention; used to propagate grounded evidence.

- GNN — Graph Neural Network — Neural architectures over graphs for structured reasoning/grounding.

- GoT — Graph-of-Thoughts — Represents reasoning as a graph of states/operations to explore multiple paths.

- Grad-CAM — Gradient-based localization on intermediate features for interpretability of decisions.

- Gradient × Input — Simple attribution method multiplying gradients by inputs to estimate token importance.

- Graph-RAG — RAG that leverages knowledge graphs/graph structure for retrieval and grounding.

- G-Retriever — Graph-aware retriever designed to recall evidence that reduces hallucinations.

- H

- HADES — Reference-free hallucination detection dataset for QA.

- HALO — Estimation + reduction framework for hallucinations in open-source LLMs.

- HALOGEN — Structure-aware reasoning/verification pipeline to reduce unsupported claims.

- HalluciNot — Retrieval-assisted span verification to detect and mitigate hallucinations.

- HaluBench — Benchmark suite for evaluating hallucinations across tasks or RAG settings.

- HaluEval — Large-scale hallucination evaluation benchmark.

- HaluEval-Wild — “In-the-wild” hallucination evaluation using web-scale references.

- HaluSearch — Retrieval-in-the-loop detection/mitigation pipeline that searches evidence while generating.

- HAR — Hallucination Augmented Recitations — Produces recitations/snippets that anchor generation to evidence.

- HDM-2— Hallucination Detection Method 2 — Modular multi-detector system targeting specific hallucination types.

- HERMAN — Checks entities/quantities in outputs against source to avoid numerical/entity errors.

- HILL — Human-factors-oriented hallucination identification framework/benchmark.

- Hidden Markov Chains — Sequential state models used to analyze latent dynamics associated with hallucinations.

- HIPO — Hard-sample-aware iterative preference optimization to improve robustness.

- HSP — Hierarchical Semantic Piece — Hierarchical text segmentation/representation to stabilize retrieval and grounding.

- HybridRAG — Combines multiple retrieval sources/strategies (e.g., dense + sparse + KG) for stronger grounding.

- HumanEval — Code generation benchmark often used in hallucination-sensitive program synthesis.

- HVM — Hypothesis Verification Model — Classifier/verifier that filters candidates by textual entailment with evidence.

- I

- ICD — Induce-then-Contrast Decoding — Induces errors with a weaker model and contrasts to discourage hallucinated tokens.

- INSIDE — Internal-state-based uncertainty estimation with interventions to reduce overconfidence.

- Input Erasure — Attribution by removing/ablating input spans to see their effect on outputs.

- InterrogateLLM — Detects hallucinations via inconsistency across multiple answers/contexts.

- Iter-AHMCL — Iterative decoding with hallucination-aware contrastive learning to refine outputs.

- ITI — Inference-Time Intervention — Nudges specific heads/activations along truth-aligned directions during decoding.

- J

- Joint Entity and Summary Generation — Summarization that jointly predicts entities and the abstract to reduce unsupported content.

- K

- KB — Knowledge Base — External repository of facts used for grounding/verification.

- KCA — Knowledge-Consistent Alignment — Aligns model outputs with retrieved knowledge via structured prompting/objectives.

- KG — Knowledge Graph — Graph-structured facts used for retrieval, verification, and attribution.

- KGR — Knowledge Graph Retrofitting — Injects/retrofits KG-verified facts into outputs or intermediate representations.

- KL-divergence — Divergence measure used in calibration/regularization and to compare layer distributions.

- Knowledge Overshadowing — When parametric priors dominate over context, causing the model to ignore given evidence.

- L

- LaBSE — Multilingual sentence encoder used for cross-lingual matching/verification.

- LASER — Language-agnostic sentence embeddings for multilingual retrieval/entailment.

- LAT — Linear Artificial Tomography — Linear probes/edits to reveal and steer latent concept directions.

- LayerSkip — Self-speculative decoding with early exits/verification by later layers.

- LID — Local Intrinsic Dimension — Dimensionality measure of hidden states linked to uncertainty/truthfulness.

- LinkQ — Forces explicit knowledge-graph queries to ground answers.

- LLM — Large Language Model — Transformer-based model trained for next-token prediction and generation.

- LLM Factoscope — Probing/visualization of hidden-state clusters to distinguish factual vs fabricated content.

- LLM-AUGMENTER — Orchestrates retrieval/tools around an LLM to improve grounding and reduce errors.

- Logit Lens — Projects intermediate residual streams to the vocabulary space to inspect token preferences.

- Lookback Lens — Attention-only method that checks whether outputs attend to relevant context.

- LoRA — Low-rank adapters for efficient finetuning, commonly used in factuality/hallucination pipelines.

- LQC — Lightweight Query Checkpoint — Predicts when a query needs verification or retrieval before answering.

- LRP — Layer-wise Relevance Propagation — Decomposes predictions to attribute token-level contributions.

- M

- MARL — Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning — Multiple agents coordinate/critique each other to improve reliability.

- MC — Monte Carlo — Stochastic sampling used for uncertainty estimation and search.

- MCTS — Monte Carlo Tree Search — Guided tree exploration used in deliberate, plan-and-verify reasoning.

- METEOR — MT metric leveraging synonymy/stemming; not a direct factuality measure.

- mFACT — Decoding-integrated factuality signal to prune low-faithfulness candidates.

- MixCL — Mixed contrastive learning (with hard negatives) to reduce dialog hallucinations.

- MoCo — Momentum contrast representation learning used to build stronger encoders.

- MoE — Mixture-of-Experts — Sparse expert routing to localize knowledge and reduce interference.

- N

- NEER — Neural evidence-based evaluation/repair methods that use entailment or retrieved evidence to improve outputs.

- Neural Path Hunter — Analyzes reasoning paths/graphs to locate error-prone segments for correction.

- Neural-retrieval-in-the-loop — Integrates a trainable retriever during inference to stabilize grounding.

- NL-ITI — Non-linear version of ITI with richer probes and multi-token interventions.

- NLU — Natural Language Understanding — Models/components (e.g., NLI, QA) used as verifiers or critics.

- Nucleus Sampling — Top-p decoding that samples from the smallest set whose cumulative probability exceeds p.

- O

- OVON — Open-Vocabulary Object Navigation; task setting where language directs navigation to open-set objects, used in agent/LLM evaluations.

- P

- PCA — Principal Component Analysis — Projects activations to principal subspaces to analyze truth/lie separability.

- PGFES — Psychology-guided two-stage editing and sampling along “truthfulness” directions in latent space.

- Persona drift — When a model’s stated persona/stance shifts across sessions or contexts.

- PoLLMgraph — Probabilistic/graph model over latent states to track hallucination dynamics.

- PMI — Pointwise Mutual Information — Signal for overshadowing/low-confidence conditions during decoding.

- Principle Engraving — Representation-editing to imprint desired principles into activations.

- Principle-Driven Self-Alignment — Self-alignment method that derives rules/principles and tunes behavior accordingly.

- ProbTree — Probabilistic Tree-of-Thought — ToT reasoning with probabilistic selection/evaluation of branches.

- PURR — Trains on corrupted vs. corrected claims to produce a compact, factuality-aware model.

- TOPICPREFIX — Prompt/prefix-tuning scheme to stabilize topic adherence and reduce drift.

- Q

- Q2 — Factual consistency measure comparing outputs to retrieved references.

- R

- R-Tuning — Instructioning/tuning models to abstain or say “I don’t know” when unsure.

- RAG — Retrieval-Augmented Generation — Augments generation with document retrieval for grounding.

- RAG-KG-IL — RAG integrated with knowledge-graph and incremental-learning components.

- RAG-Turn — Turn-aware retrieval for multi-turn tasks.

- RAGTruth — Human-annotated data for evaluating/teaching RAG factuality.

- RAP — Reasoning viA Planning — Planning-style reasoning that structures problem solving before answering.

- RARR — Retrieve-and-Revise pipeline that edits outputs to add citations and fix unsupported claims.

- RBG — Read-Before-Generate — Reads/retrieves first, then conditions generation on the evidence.

- REPLUG — Prepends retrieved text and averages probabilities across retrieval passes to ground decoding.

- RepE — Representation Engineering — Editing/steering latent directions to improve honesty/faithfulness.

- RefChecker — Reference-based fine-grained hallucination checker and diagnostic benchmark.

- Reflexion — Self-critique loop where the model reflects on errors and retries.

- RID — Retrieval-In-Decoder — Retrieval integrated directly into the decoder loop.

- RHO — Reranks candidates by factual consistency with retrieved knowledge or graph evidence.

- RHD — Real-time Hallucination Detection — Online detection and optional self-correction during generation.

- RLCD — Reinforcement Learning with Contrastive Decoding — RL variant that pairs contrastive objectives with decoding.

- RLHF — Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback — Uses human preference signals to align model behavior.

- RLAIF — Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback — Uses AI-generated preference signals to scale alignment.

- RLKF — Reinforcement-Learning-based Knowledge Filtering that favors context-grounded generation.

- ROUGE — Overlap-based summarization metric (e.g., ROUGE-L).

- RaLFiT — Reinforcement-learning-style fine-tuning aimed at improving truthfulness/factuality.

- S

- SC2— Structured Comparative Reasoning — Compares structured alternatives and selects the most consistent one.

- SCOTT — Self-Consistent Chain-of-Thought Distillation — Samples multiple CoTs and distills the consistent answer.

- SCD — Self-Contrastive Decoding — Penalizes over-represented priors to counter knowledge overshadowing.

- SEA — Spectral Editing of Activations — Projects activations along truth-aligned directions while suppressing misleading ones.

- SEAL — Selective Abstention Learning — Teaches models to abstain (e.g., emit a reject token) when uncertain.

- SEBRAG — Structured Evidence-Based RAG — RAG variant that structures evidence and grounding steps.

- SEK — Evidence selection/structuring module used to verify or revise outputs.

- SEPs — Semantic Entropy Probes — Fast probes that estimate uncertainty from hidden states.

- Self-Checker — Pipeline that extracts and verifies claims using tools or retrieval.

- Self-Checks — Generic self-verification passes (consistency checks, regeneration, or critique).

- Self-Consistency — Samples multiple reasoning paths and selects the majority-consistent result.

- Self-Familiarity — Calibrates outputs based on what the model “knows it knows” vs. uncertain areas.

- Self-Refine — Iterative refine-and-feedback loop where the model improves its own draft.

- Self-Reflection — The model reflects on its reasoning and revises responses accordingly.

- SELF-RAG — Self-reflective RAG where a critic guides retrieval and edits drafts.

- SelfCheckGPT — Consistency-based hallucination detector using multiple sampled outputs.

- — Self-Highlighted Hesitation — Injects hesitation/abstention mechanisms at uncertain steps.

- SimCLR — Contrastive representation learning framework used to build stronger encoders.

- SimCTG — Contrastive text generation that constrains decoding to avoid degenerate outputs.

- Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) — Matrix factorization used to analyze or edit latent directions.

- Socratic Prompting — Uses guided questions to elicit intermediate reasoning and evidence.

- T

- ToT — Tree-of-Thought — Branch-and-evaluate reasoning over a tree of intermediate states.

- TOPICPREFIX — Prompt/prefix-tuning that encodes topics to stabilize context adherence.

- TrueTeacher — Teacher-style training that builds a factual evaluator and uses it to guide student outputs.

- Truth Forest — Learns orthogonal “truth” representations and intervenes along those directions.

- TruthfulQA — Benchmark evaluating resistance to common falsehoods.

- TruthX — Latent editing method that nudges activations toward truthful directions.

- Tuned Lens — Learns linear mappings from hidden states to logits to study/steer layer-wise predictions.

- TWEAK — Think While Effectively Articulating Knowledge — Hypothesis-and-NLI-guided reranking that prefers supported continuations.

- U

- UHGEval — Hallucination evaluation benchmark for unconstrained generation in Chinese and related settings.

- UPRISE — Uses LLM signals to train a retriever that selects stronger prompts/evidence.

- V

- Verbose Cloning — Prompting/aggregation technique that elicits explicit, fully-specified answers to reduce ambiguity.

- X

- XCoT — Cross-lingual Chain-of-Thought prompting/transfer.

- XNLI — Cross-lingual NLI benchmark commonly used for entailment-based verification.

References

- S. M. T. I. Tonmoy et al., “A Comprehensive Survey of Hallucination Mitigation Techniques in Large Language Models,” Jan. 2024, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2401.01313.

- Y. Su, T. Lan, Y. Wang, D. Yogatama, L. Kong, and N. Collier, “A Contrastive Framework for Neural Text Generation,” Feb. 2022, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2202.06417.

- T. R. McIntosh et al., “A Culturally Sensitive Test to Evaluate Nuanced GPT Hallucination,” IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 51555–51572, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A.Shelmanov et al., “A Head to Predict and a Head to Question: Pre-trained Uncertainty Quantification Heads for Hallucination Detection in LLM Outputs,” May 2025, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2505.08200.

- J. White et al., “A Prompt Pattern Catalog to Enhance Prompt Engineering with ChatGPT,” Feb. 2023, [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2302.11382.