1. Introduction

Stroke is the leading cause of long-term disability worldwide, with a particularly high incidence in older adults. With an aging global population, the number of stroke survivors living with sequelae continues to increase [

1]. More than 50% of stroke survivors experience upper limb motor impairments [

2,

3], and many patients report persistent dysfunction in the chronic phase [

4,

5,

6]. Upper limb impairment severely restricts the performance of activities of daily living (ADLs), thereby reducing independence and quality of life. Consequently, the development of effective and feasible rehabilitation strategies to restore upper limb function remains an urgent issue.

One such rehabilitation approach for upper limb paresis is mirror therapy, which uses mirror visual feedback (MVF). This method was first introduced by Ramachandran et al. for the treatment of phantom limb pain [

7] and was later applied to motor recovery in post-stroke hemiparesis by Altschuler et al. [

8]. Subsequently, numerous randomized controlled trials have been conducted, and systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated its efficacy in improving upper limb function [

9,

10] and reducing spasticity in patients with stroke [

11].

In recent years, novel therapeutic approaches have been developed that combine MVF with techniques, such as electrical stimulation (ES), robotic assistance, and virtual reality (VR) in bimanual MVF therapy, aiming to promote afferent input from the affected side and enhance visual feedback [

12,

13,

14]. Zhuang et al. demonstrated that “associated mirror therapy” significantly improved motor function of the paretic upper limb and ADL performance [

15]. Furthermore, systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported that although conventional MVF produces a moderate effect size on paretic upper limb function (standardized mean difference [SMD] = 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.34–1.02), hybrid MVF incorporating ES or VR yields a large effect size (SMD = 1.28; 95% CI, 0.89–1.67) [

9]. In addition, interventions combining MVF with ES are significantly superior to sham therapy, ES alone, or MVF alone in improving upper limb motor control based on impairment level and gross grasping ability based on activity level [

16].

Previous neuroimaging studies, particularly those using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), have suggested that MVF activates neural networks associated with the mirror neuron system (MNS), including the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), superior temporal sulcus, and inferior parietal lobule [

17,

18]. More recently, studies employing resting-state fMRI have reported that visual input through a mirror facilitates ipsilateral pathway activation toward the paretic upper limb via increased spontaneous activity in the contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) and reconstructs functional connectivity between the bilateral M1, thereby promoting motor signal transmission from the ipsilesional M1 to the contralesional M1 [

19]. In addition, MVF recruits the MNS, corrects interhemispheric imbalance, and promotes motor recovery after stroke [

20].

In contrast, combined MVF and ES therapy is thought to indirectly contribute to motor recovery in patients with stroke by simultaneously enhancing proprioceptive and tactile inputs, increasing the activation of sensory cortices, and augmenting sensory projections to motor areas [

21]. Although recent studies using fMRI, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), and electroencephalography (EEG) have advanced our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying MVF, the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying combined MVF and ES therapy remain unclear.

In a previous study involving healthy young adults, we evaluated the effects of MVF alone and in combination with ES on brain activity using functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS). We demonstrated that although mirrored visual input activated the contralateral sensory cortex of the nonmoving limb, the addition of ES suppressed cortical activity [

22]. However, most of these fundamental findings have been derived from young adults, and studies focusing on healthy older adults remain limited. Given that aging is associated with changes in brain structure, hemodynamics, and sensorimotor processing [

23,

24], caution should be exercised when generalizing findings from young adults to older populations. Therefore, it is important to investigate whether similar effects are observed in healthy older adults. Moreover, although the combination of MVF and ES has been suggested to enhance rehabilitation effects by simultaneously activating sensory input and motor networks [

21], neurophysiological investigations in older adults remain insufficient.

Accordingly, the present study aimed to evaluate the effects of MVF alone and MVF combined with ES on upper limb function and cortical hemodynamics in healthy older adults using fNIRS, to clarify their efficacy and underlying neural mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

All the participants were volunteers who were confirmed to be free of neurological disorders based on a pre-screening questionnaire. Twenty-two healthy adults (12 men and 10 women; mean age, 63.5 ± 8.6 years) were initially enrolled. All participants were right-handed, as determined by Chapman’s handedness test [

25]. Owing to incomplete MRI or fNIRS data, five participants were excluded, leaving a final sample of 17 individuals (nine men and eight women; mean age, 63.4 ± 7.3 years).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hokkaido University Hospital (Clinical Research No. 012-0086). All the participants received a detailed explanation of the study objectives, ES and fNIRS procedures, associated safety considerations, potential risks, and their management. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before enrollment.

2.2. Experimental Overview

2.2.1. Experimental Condition Setup

The participants were seated in a reclining chair, and a mirror box was placed on a horizontal table in front of them. They were instructed to insert both hands into the mirror box with their forearms in a pronated position (ulnar side down). The participants were also instructed to remove accessories, such as rings and watches. Room temperature was maintained at 24°C.

2.2.2. Tasks

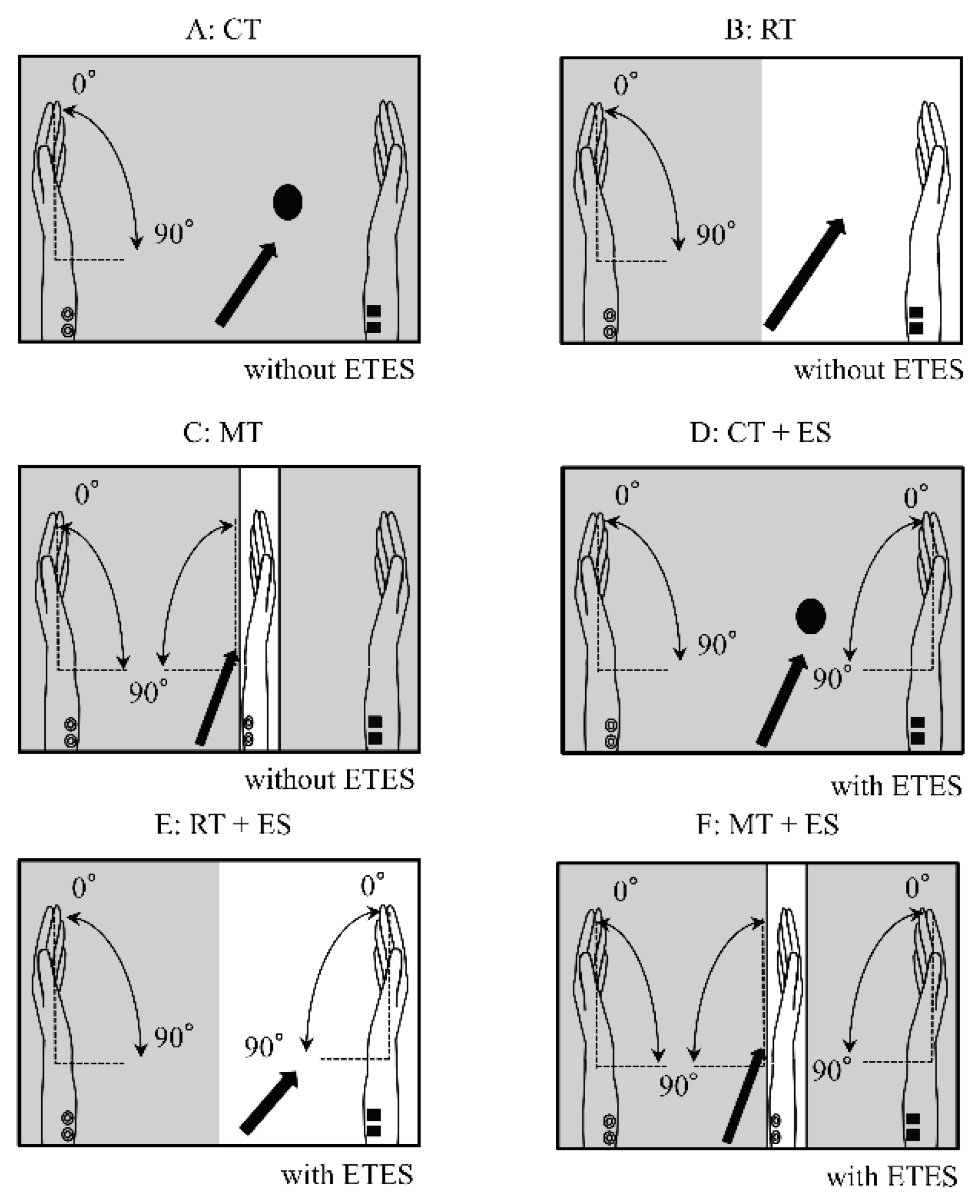

The tasks used in the experiments are illustrated in

Figure 1. In all tasks, the participants performed repetitive flexion of the left wrist at a frequency of 0.5 Hz for 30 s. Prior to the experiment, participants practiced moving their left hand to a metronome (Art Metronome, Mu-tech Co., Inc.) while using electromyography-triggered ES (ETES) on both hands. They were instructed to ensure that the movement of the electrically stimulated right hand was as similar as possible to voluntary movement of the left hand.

The six experimental conditions were as follows:

Circle task (CT): The lid of the mirror box was closed, and the participants observed a black circle drawn on top of the box without viewing their hands (

Figure 1A).

Right hand task (RT): The lid of the mirror box was open, and the participants observed their right hand at rest (

Figure 1B).

Mirror task (MT): The right hand was placed behind a mirror inside the mirror box, and the participants observed the mirror image so that the moving left hand overlapped with the right hand (

Figure 1C).

CT + ES: Using ETES, flexion of the right wrist was electrically induced in synchrony with voluntary contraction of the left forearm muscle. The stimulation device for the ETES was the LEMDES. During the task, stimulation electrodes were attached to the right wrist flexor muscles, and trigger signals were obtained from the left flexor carpi radialis (FCR). This setup enabled the right hand movement in response to the left hand movement. The lid of the mirror box was closed, and the participants were instructed to fixate on a black circle drawn on the box (

Figure 1D).

RT + ES: The participants observed electrically induced movement of their right hands (

Figure 1E).

MT + ES: Using ETES, the participants observed the mirror as in the MT condition (

Figure 1F).

The participants were instructed to focus only on the right hand rather than on the entire right upper limb. During the CT, RT, and MT conditions, the participants were instructed not to move their right hands.

To verify that the activity of the left forearm wrist flexors remained consistent, electromyographic (EMG) electrodes were attached between the medial epicondyle of the humerus and the palmar base of the second metacarpal, at a site 3–10 cm distal to the medial epicondyle (corresponding to the belly of the muscle), using disposable electrodes (Vitrode F; Nihon Kohden Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The EMG signals were connected directly to a multichannel amplifier (MEG-6108M, Nihon Kohden Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) and monitored in real time using the fNIRS system.

2.2.3. Equipment

2.2.3.1. Electromyography-Triggered Electrical Stimulation

The ETES system used in our previous study [

22] was used. The stimulation electrodes (rubber electrodes) were placed 2–3 cm apart on the right forearm flexor muscles, and the triggering EMG was recorded from the left FCR using surface-disposable Ag-AgCl electrodes (Vitrode F, Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan). The ground electrode was placed on the left olecranon. This method, developed by Futami et al. [

26], enables right hand movement to be elicited by voluntary left hand movement. In ETES, ES is triggered by EMG activity.

The stimulation parameters were as follows: frequency, 20 Hz; and pulse width, 500 ms. The ES intensity was set below each participant’s pain threshold but above the motor threshold before task initiation. The sensitivity of the triggered EMG was adjusted so that full joint movements could be elicited by ES.

2.2.4. Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Settings

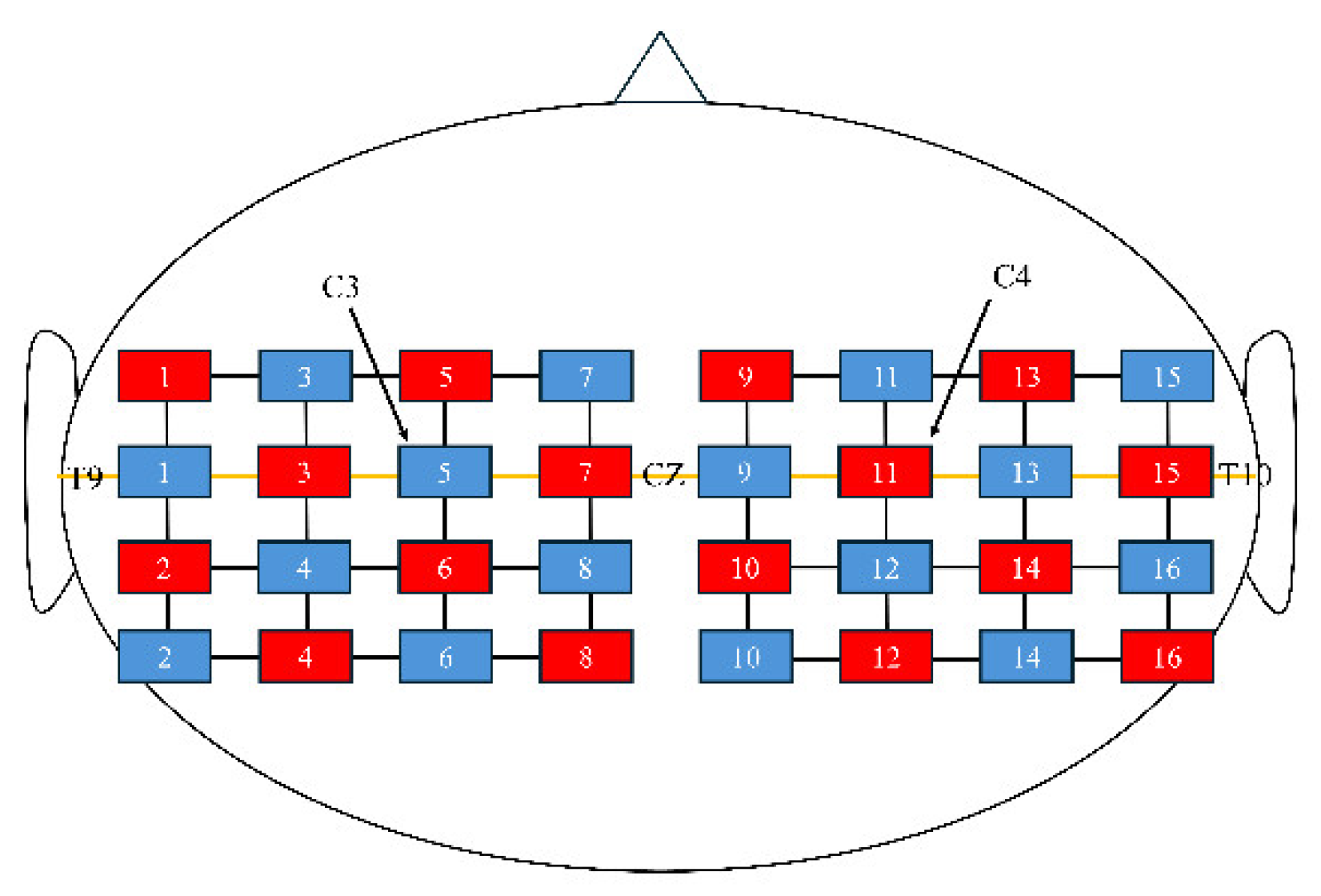

Hemodynamic responses were measured using fNIRS (FOIRE 3000; Shimadzu Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) with a holder consisting of 16 light-source probes and 16 detector probes arranged in a 4 × 4 × 2 configuration, yielding 48 channels. The probe placement was based on the virtual registration method described by Tsuzuki et al. [

27]. Specifically, the second column of probes from the front was aligned with the coronal reference curve, and the probe located in the second row from the top and second column from the front was positioned at C3 (or C4 for the right hemisphere) according to the international 10–20 system [

28] (

Figure 2). The distance between the light-source and detector probes was set at 3 cm.

Three wavelengths (708, 805, and 830 nm) were used to detect oxygenated hemoglobin (oxy-Hb), deoxygenated hemoglobin (deoxy-Hb), and total hemoglobin (total-Hb). A three-dimensional (3D) digitizer (FASTRAK; Polhemus, Colchester, VT, USA) was used to determine the anatomical location of each channel. In addition, 3D T1-weighted MR images of all participants were acquired using an MRI scanner (Signa Lightning; GE Healthcare). The channel positions obtained from the 3D digitizer were co-registered with each participant’s cortical surface using NIRS-SPM [

29]. The co-registered channels were classified into the bilateral IFG, precentral gyrus (PrG), postcentral gyrus (PoG), supplementary motor area (SMA), supramarginal gyrus (SMG), and superior parietal lobule (SPL).

Because the spatial resolution of fNIRS is limited to approximately 2–3 cm [

30], channels located within the sulci were excluded from the analysis. To standardize the changes in oxy-Hb levels, we confirmed the stability of the oxy-Hb signals at the onset of each task.

2.3. Data Processing

Based on previous reports indicating that changes in oxy-Hb concentration are more sensitive to neural activity than changes in deoxy-Hb or total-Hb concentration [

31,

32,

33], the present study focused on analyzing oxy-Hb concentration changes. Oxy-Hb signals were obtained using the modified Beer–Lambert law [

34] implemented in the fNIRS system. Baseline correction was performed by setting the mean concentration change during the 5 s preceding the task onset to zero. Motion artifacts were corrected using spline interpolation.

As a characteristic feature of fNIRS is that oxy-Hb responses to neural activity occur with a delay after task onset [

35], the mean oxy-Hb concentration was calculated over a 25-s window from 5 to 30 s after task initiation. The mean oxy-Hb values obtained from each task were analyzed using a two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with factors “ES condition (ESC; with or without ES)” and “visual condition (VC; circle fixation, right hand, mirror)” (2 × 3 design).

In addition, as a priori hypotheses, the simple effects of ES within each VC (CT + ES − CT, RT + ES − RT, MT + ES − MT) were set as primary contrasts. Familywise error rates were controlled for each region of interest (ROI) using the Bonferroni method (two-tailed, α = 0.05). Post hoc comparisons were also conducted using the Bonferroni correction. The EMG amplitudes obtained from the left wrist flexors were analyzed in the same manner. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 30 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Owing to probe placement issues, data from 13 participants were analyzed for the left IFG and nine participants for the right IFG.

3. Results

The results of the 2 × 3 repeated-measures ANOVA are presented in

Table 1, and the results of multiple comparisons are presented in

Table 2.

Left IFG: ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of ESC (F [

1,

12] = 8.72, p < 0.05) and a significant interaction between VC and ESC (F [

2,

24] = 4.66, p < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that oxy-Hb concentrations were higher in tasks with ES than in those without ES (p < 0.05). Moreover, oxy-Hb concentrations were significantly higher in MT + ES than in MT (p < 0.01).

Left PrG: A significant main effect of ESC was observed (F [

1,

16] = 8.49, p < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that oxy-Hb concentrations were higher in tasks with ES than in those without ES (p < 0.05). In addition, oxy-Hb concentrations were significantly higher in CT + ES than in CT (p < 0.05) and in MT + ES than in MT (p < 0.05).

Left PoG: A significant main effect of ESC was observed (F [

1,

16] = 6.99, p < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that oxy-Hb concentrations were higher in tasks with ES than in those without ES (p < 0.05). Furthermore, oxy-Hb concentrations were significantly higher in CT + ES than in CT (p < 0.01) and in RT + ES than in RT (p < 0.05).

Left SMG: A significant main effect of ESC was observed (F [

1,

16] = 7.49, p < 0.05). Post-hoc analysis showed that oxy-Hb concentrations were higher in tasks with ES than in those without ES (p < 0.05). In addition, oxy-Hb concentrations were significantly higher in CT + ES than in CT (p < 0.01), in RT + ES than in RT (p < 0.05), and in MT + ES than in MT (p < 0.05).

Left SPL: No significant main effects were observed in ANOVA. However, post-hoc analysis showed significantly higher oxy-Hb concentrations in CT + ES than in CT (p < 0.05) and RT than in CT (p < 0.05).

Right IFG: No significant main effects were observed in ANOVA. Post-hoc analysis revealed significantly higher oxy-Hb concentrations in CT + ES than in CT (p < 0.05).

Right PrG: No significant main effects were observed in ANOVA. Post-hoc analysis showed significantly higher oxy-Hb concentrations in CT + ES than in CT (p < 0.05).

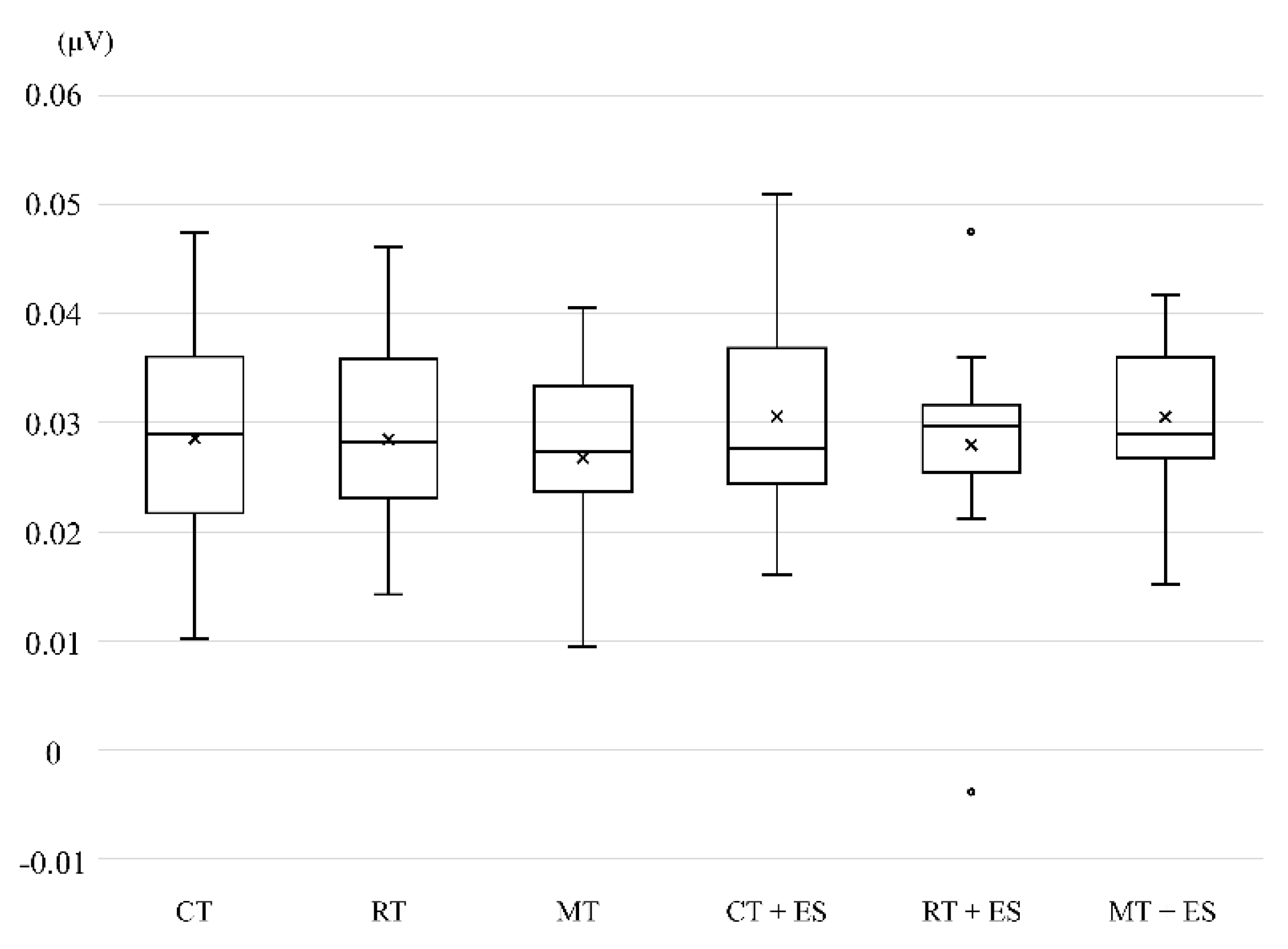

Finally, no significant differences were observed in the EMG amplitudes of the left forearm (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

In this study, we investigated the cortical hemodynamics during MVF alone and in combination with ES in healthy older adults using fNIRS. The findings can be summarized as follows. First, as a main effect, the addition of ES significantly increased oxy-Hb concentrations in the left IFG, left PrG, left PoG, and left SMG. Second, regarding interaction effects, a significant VC × ESC interaction was observed in the left IFG, with a particularly pronounced increase under the MT + ES condition. Third, the analysis of simple effects by condition revealed that CT + ES induced widespread activation extending to the left PoG, left PrG, left SMG, left SPL, right PrG, and right IFG, whereas RT + ES and MT + ES primarily enhanced activation in the left hemispheric MNS-related regions (IFG/SMG).

Taken together, these results indicate that ES generally enhances MVF-related cortical responses in healthy older adults and that the pattern of enhancement varies depending on the VC.

The widespread activation observed under the CT + ES condition is consistent with the Hemispheric Asymmetry Reduction in Older Adults, Compensation-Related Utilization of Neural Circuits, and Posterior–Anterior Shift in Aging models, which posit compensatory cortical recruitment associated with aging [

36,

37,

38]. Given that no significant differences were found in the left forearm EMG during the tasks, it is plausible that the additional right hemisphere activation reflected excessive cortical activation induced by ES rather than increased peripheral motor output. Numerous fMRI studies have demonstrated greater activation of the M1, premotor, and prefrontal cortices during hand motor tasks in older adults than in younger adults [

39,

40]. Such widespread cortical activity in older adults has been observed in both cognitive and motor domains and has been interpreted to reflect either compensatory processes or de-differentiation [

41].

Furthermore, Brodoehl et al. compared the sensory thresholds and brain activation in response to right upper limb somatosensory stimulation in younger and older adults [

24]. Their results showed that sensory thresholds increased with age and that compared with younger adults, older adults exhibited activation not only in the contralateral sensory cortex but also in the ipsilateral M1 and SMA. These findings suggest that the excessive activation observed in older adults reflects not only compensatory recruitment to counteract age-related declines in brain function but also changes in the balance between interhemispheric excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms. In addition, fMRI studies have shown that in older adults, tactile processing of peripheral input spreads beyond the contralateral primary somatosensory cortex to the bilateral secondary somatosensory cortex and parietal association areas. Therefore, the extension of activation to the SMG and SPL observed in CT + ES is consistent with this multiregional integration model [

42].

In contrast, in the RT + ES and MT + ES conditions, where visual guidance was present, activation was primarily localized to the left hemisphere’s MNS-related regions (IFG/SMG). Motor observation and MVF can engage interhemispheric inhibition [

43,

44] and intracortical inhibition [

45]. Such inhibitory mechanisms may suppress the spread of activity in the right hemisphere.

Taken together, these findings suggest that although ES enhances MVF-related responses in older adults, the expression of this enhancement diverges depending on the presence of visual cues and the involvement of inhibitory mechanisms accompanying motor observation.

When ES was combined with observation-based conditions (RT/MT), activation was observed in the left hemisphere MNS-related regions (IFG/SMG) and in the PrG. This finding can be interpreted as the integration of somatosensory inputs derived from the ES with MNS recruitment elicited by motor observation [

46,

47]. In the present study, no substantial differences were observed between MT + ES and RT + ES. Zhang et al. examined the differences in M1 activation following MVF and motor observation therapy in patients with stroke using TMS [

48]. They reported that motor-evoked potentials (MEPs) in M1 significantly increased only after MVF. In our study, oxy-Hb concentration significantly increased in the left PrG in the MT + ES condition, suggesting the possibility of enhanced activation of corticospinal neurons. However, because MEPs were not measured in this study, further investigation is required.

Unlike in our previous study [

22], the ES tasks in this study did not reduce oxy-Hb concentration, but instead increased it across the hemisphere corresponding to the stimulated muscles. Guirro et al. investigated the differences in sensory and motor thresholds for transcutaneous ES with respect to sex and age [

49]. They found that motor thresholds were higher in older adults. Because older adults tend to have a higher fat-to-muscle ratio, the current resistance is likely to increase, which in turn may necessitate a greater stimulation intensity to excite the motor nerves. This suggests that age-related changes in tissue composition are related to increased threshold intensity. In the present study, the ES intensity was set above the motor threshold but below the pain threshold. However, because the actual output levels were not measured, it remains unclear whether interindividual differences exist. However, this issue requires further investigation.

This study has some limitations. First, it was restricted to healthy older adults, all of whom were right-handed and employed a simple wrist flexion task; therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing the findings to patients with stroke or to more complex ADL-like movements. Second, the final analysis included only 17 participants, and the number of participants varied across ROIs (e.g., right IFG), leaving uncertainty in the effect estimation and the potential risk of Type II error. Third, fNIRS measurements are limited to the superficial cortical regions and cannot fully eliminate contamination from skin blood flow or systemic physiological noise. Fourth, although stimulation intensity was individually adjusted to “above motor threshold and below pain threshold,” actual stimulation parameters (e.g., mA, pulse width, total charge) and subjective intensity ratings were not recorded, making it difficult to fully control for interindividual variability in afferent sensory input.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we compared the cortical hemodynamics during MVF alone and MVF combined with ES in healthy older adults using fNIRS. The results demonstrated that the addition of ES generally enhanced MVF-related responses; however, the expression of this enhancement varied depending on the visual context. Specifically, ES predominantly increased activation in left hemisphere MNS-related regions, whereas under conditions with limited visual cues (CT + ES), activation extended to somatosensory–attentional/integration networks. In contrast, under observation-based conditions (RT/MT), the activation was primarily confined to the left hemisphere, suggesting the involvement of inhibitory mechanisms in motor observation. As no differences in EMG were observed during the tasks, these differences are interpreted as reflecting not variations in effort but rather the requirements of visuoafferent integration and age-related patterns of cortical recruitment.

Taken together, these findings suggest that combining ES with MVF is a promising approach for enhancing sensorimotor network recruitment in older adults. Moreover, the design of visual cues (e.g., the presence or richness of mirrored feedback) may allow the modulation of the extent of cortical activation. Future studies should aim to establish the clinical utility of this approach by quantifying the dose–response relationships of ES, directly examining the underlying mechanisms through the combined use of TMS and EEG, and evaluating functional transfer effects (motor performance and ADL) in patient populations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.I. and D.S.; methodology, Y.I.; software, Y.I.; validation, Y.I. and D.S.; formal analysis, Y.I. and M.N.; investigation, Y.I. and Y.N.; resources, Y.I. and Y.N.; data curation, Y.I. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.I.; writing—review and editing, Y.I. and D.S.; visualization, Y.I.; supervision, Y.I. and D.S.; project administration, Y.I.; funding acquisition, Y.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (grant number 24K23043).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Ethics Committee of Hokkaido University Hospital (010-0171) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available because of privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all participants for their time and cooperation in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADL |

Activities of daily living |

| MVF |

Mirror visual feedback |

| ES |

Electrical stimulation |

| VR |

Virtual reality |

| SMD |

Standardized mean difference |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| fMRI |

Functional magnetic resonance imaging |

| MNS |

Mirror neuron system |

| IFG |

Inferior frontal gyrus |

| M1 |

Primary motor cortex |

| TMS |

Transcranial magnetic stimulation |

| EEG |

Electroencephalography |

| fNIRS |

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy |

| ETES |

EMG-triggered electrical stimulation |

| FCR |

Flexor carpi radialis |

| EMG |

Electromyographic |

| CT |

Circle task |

| RT |

Right hand task |

| MT |

Mirror task |

| oxy-Hb |

Oxygenated hemoglobin |

| deoxy-Hb |

Deoxygenated hemoglobin |

| total-Hb |

Total hemoglobin |

| PrG |

Precentral gyrus |

| PoG |

Postcentral gyrus |

| SMG |

Supramarginal gyrus |

| SMA |

Supplementary motor area |

| SPL |

Superior parietal lobule |

| ESC |

Electrical stimulation condition |

| VC |

Visual condition |

| MEPs |

Motor-evoked potentials |

| ROI |

Region of interest |

References

- GBD 2021 Stroke Risk Factor Collaborators; Feigin, V.L. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 973–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, H.S.; Nakayama, H.; Raaschou, H.O.; Vive-Larsen, J.; Støier, M.; Olsen, T.S. Outcome and time course of recovery in stroke. Part I: Outcome. The Copenhagen Stroke Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1995, 76, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.S.; Coshall, C.; Dundas, R.; Stewart, J.; Rudd, A.G.; Howard, R.; Wolfe, C.D. Estimates of the prevalence of acute stroke impairments and disability in a multiethnic population. Stroke 2001, 32, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo-Filho, M.; Bemben, M.G.; Taiar, R.; Sañudo, B.; Furness, T.; Clark, B.C. Editorial: Interventional strategies for enhancing quality of life and health span in older adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Z.H.; Si, X.K.; Sun, X. Stroke-induced damage on the blood-brain barrier. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1248970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekoubou, A.; Nguyen, C.; Kwon, M.; Nyalundja, A.D.; Agrawal, A. Post-stroke everything. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2023, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, V.S.; Rogers-Ramachandran, D. Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with a mirror. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1996, 263, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschuler, E.L.; Wisdom, S.B.; Stone, L.; Foster, C.; Galasko, D.; Llewellyn, D.M.; Ramachandran, V.S. Rehabilitation of hemiparesis after stroke with a mirror. Lancet 1999, 353, 2035–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, E.; Jung, J.; Lee, S. Utilization of mirror visual feedback for upper limb function in poststroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vision 2023, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Guo, Y.; Wu, G.; Liu, X.; Fang, Q. Mirror therapy for motor function of the upper extremity in patients with stroke: A meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Gómez, E.; Inglés, M.; Aguilar-Rodríguez, M.; Sempere-Rubio, N.; Mollà-Casanova, S.; Serra-Año, P. Effects of mirror therapy on spasticity and sensory impairment after stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PM R 2023, 15, 1478–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Sui, Y.; Yu, W.; Yuan, Y. Effects of contralateral controlled functional electrical stimulation combined with mirror therapy on motor recovery and negative mood in stroke patients. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2023, 15, 6159–6169. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, J.; Liang, C.; Liu, R.; Yu, J.; Yang, T.; Bai, D. Combination of robot-assisted glove and mirror therapy improves upper limb motor function in subacute stroke patients: A randomized controlled pilot study. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1602896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Shin, W.S.; Bang, D.H. Mirror therapy using gesture recognition for upper limb function, neck discomfort, and quality of life after chronic stroke: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 3271–3278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.Y.; Ding, L.; Shu, B.B.; Chen, D.; Jia, J. Associated mirror therapy enhances motor recovery of the upper extremity and daily function after stroke: A randomized control study. Neural Plast. 2021, 2021, 7266263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurbuz, N.; Ikbali Afsar, S.; Ayaş, S.; Saracgil Cosar, S.N. Effect of mirror therapy on upper extremity motor function in stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2016, 28, 2501–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzer, G.; Selles, R.; Sezer, N.; Sutbeyaz, S.; Bussmann, J.B.; Koseoglu, F.; Atay, M.B.; Stam, H.J. Mirror therapy improves hand function in subacute stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008, 89, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthys, K.; Smits, M.; van der Geest, J.N.; van der Lugt, A.; Seurinck, R.; Stam, H.J.; Selles, R.W. Mirror-induced visual illusion of hand movements: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 675–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Ding, L.; Wang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Tong, S.; Jia, J.; Guo, X. Evidence of mirror therapy for recruitment of ipsilateral motor pathways in stroke recovery: A resting fMRI study. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.Q.; Fong, K.N.K.; Welage, N.; Liu, K.P.Y. The activation of the mirror neuron system during action observation and action execution with mirror visual feedback in stroke: A systematic review. Neural Plast. 2018, 2018, 2321045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Liu, T.W.; Ng, S.S.M.; Chen, P.M.; Chung, R.C.K.; Lam, S.S.L.; Li, C.S.K.; Chan, C.C.C.; Lai, C.W.K.; Ng, W.W.L.; Tang, M.W.S.; Hui, E.; Woo, J. Effects of mirror therapy with electrical stimulation for upper limb recovery in people with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2024, 46, 5660–5675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, Y.; Seki, K.; Makino, H.; Matsuo, Y.; Miyamoto, T.; Ikoma, K. Exploring hemodynamic responses using mirror visual feedback with electromyogram-triggered stimulation and functional near-infrared spectroscopy. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabeza, R. Hemispheric asymmetry reduction in older adults: The HAROLD model. Psychol. Aging 2002, 17, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodoehl, S.; Klingner, C.; Stieglitz, K.; Witte, O.W. Age-related changes in the somatosensory processing of tactile stimulation: An fMRI study. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 238, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, L.J.; Chapman, J.P. The measurement of handedness. Brain Cogn. 1987, 6, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futami, R.; Seki, K.; Kawanishi, T.; Sugiyama, T.; Cikajlo, I.; Handa, Y. Application of local EMG-driven FES to incompletely paralyzed lower extremities. In Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference of IFESS, Montreal, QC, Canada; 2005; pp. 204–206. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b536/c9db3b7a319eb3dab7d76d3ae799efb2c634.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Tsuzuki, D.; Jurcak, V.; Singh, A.K.; Okamoto, M.; Watanabe, E.; Dan, I. Virtual spatial registration of stand-alone fNIRS data to MNI space. NeuroImage 2007, 34, 1506–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasper, H.H. The ten–twenty electrode system of the International Federation. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1958, 10, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.C.; Tak, S.; Jang, K.E.; Jung, J.; Jang, J. NIRS-SPM: Statistical parametric mapping for near-infrared spectroscopy. NeuroImage 2009, 44, 428–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, P.W.; Stewart, M.S.; Lewis, G.; Dujovny, M.; Ausman, J.I. Intracerebral penetration of infrared light. J. Neurosurg. 1992, 76, 315–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, Y.; Sakatani, K.; Katayama, Y.; Fukaya, C. Increase in focal concentration of deoxyhaemoglobin during neuronal activity in cerebral ischaemic patients. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2002, 73, 182–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murkin, J.M.; Arango, M. Near-infrared spectroscopy as an index of brain and tissue oxygenation. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009, 103, i3–i13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiwara, N.; Sakatani, K.; Katayama, Y.; Murata, Y.; Hoshino, T.; Fukaya, C.; Yamamoto, T. Evoked-cerebral blood oxygenation changes in false-negative activations in BOLD contrast functional MRI of patients with brain tumors. NeuroImage 2004, 21, 1464–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiyama, A.; Seki, J.; Tanabe, H.C.; Sase, I.; Takatsuki, A.; Miyauchi, S.; Yanagida, T.; Iwata, Y. Circulatory basis of fMRI signals: Relationship between changes in the hemodynamic parameters and BOLD signal intensity. NeuroImage 2004, 21, 1204–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroeter, M.L.; Zysset, S.; von Cramon, D.Y. Shortening intertrial intervals in event-related cognitive studies with near-infrared spectroscopy. NeuroImage 2004, 22, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabeza, R.; Anderson, N.D.; Kester, J.; McIntosh, A.R. Hemispheric asymmetry reduction in old adults (HAROLD): Evidence for the compensation hypothesis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2002, 14, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.W.; Dennis, N.A.; Daselaar, S.M.; Fleck, M.S.; Cabeza, R. Que PASA? The posterior–anterior shift in aging. Cereb. Cortex 2008, 18, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, Y. Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009, 47, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hallett, M. The influence of normal human ageing on automatic movements. J. Physiol. 2005, 562, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuninckx, S.; Wenderoth, N.; Swinnen, S.P. Systems neuroplasticity in the aging brain: Recruiting additional neural resources for successful motor performance in elderly persons. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernard, J.A.; Seidler, R.D. Evidence for motor cortex dedifferentiation in older adults. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 1890–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Fu, S.; Zhi, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Ren, F.; Zhang, J.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y. Research progress on neural processing of hand and forearm tactile sensation: A review based on fMRI research. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2025, 21, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schütz-Bosbach, S.; Avenanti, A.; Aglioti, S.M.; Haggard, P. Don’t do it! Cortical inhibition and self-attribution during action observation. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2009, 21, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.G.; Ruddy, K.L. Vision modulates corticospinal suppression in a functionally specific manner during movement of the opposite limb. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 646–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Läppchen, C.H.; Ringer, T.; Blessin, J.; Seidel, G.; Grieshammer, S.; Lange, R.; Hamzei, F. Optical illusion alters M1 excitability after mirror therapy: A TMS study. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 108, 2857–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Merino, B.; Glaser, D.E.; Grèzes, J.; Passingham, R.E.; Haggard, P. Action observation and acquired motor skills: An fMRI study with expert dancers. Cereb. Cortex 2005, 15, 1243–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buccino, G.; Lui, F.; Canessa, N.; Patteri, I.; Lagravinese, G.; Benuzzi, F.; Porro, C.A.; Rizzolatti, G. Neural circuits involved in the recognition of actions performed by nonconspecifics: An fMRI study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2004, 16, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, B.; Li, J.; Yang, C.; Han, C.; Wang, Q. Mirror therapy versus action observation therapy: Effects on excitability of the cerebral cortex in patients after strokes. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2019, 12, 8763–8772. [Google Scholar]

- Guirro, R.R.J.; Guirro, E.C.O.; de Sousa, N.T.A. Sensory and motor thresholds of transcutaneous electrical stimulation are influenced by gender and age. PM R 2015, 7, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).