Submitted:

25 August 2025

Posted:

26 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

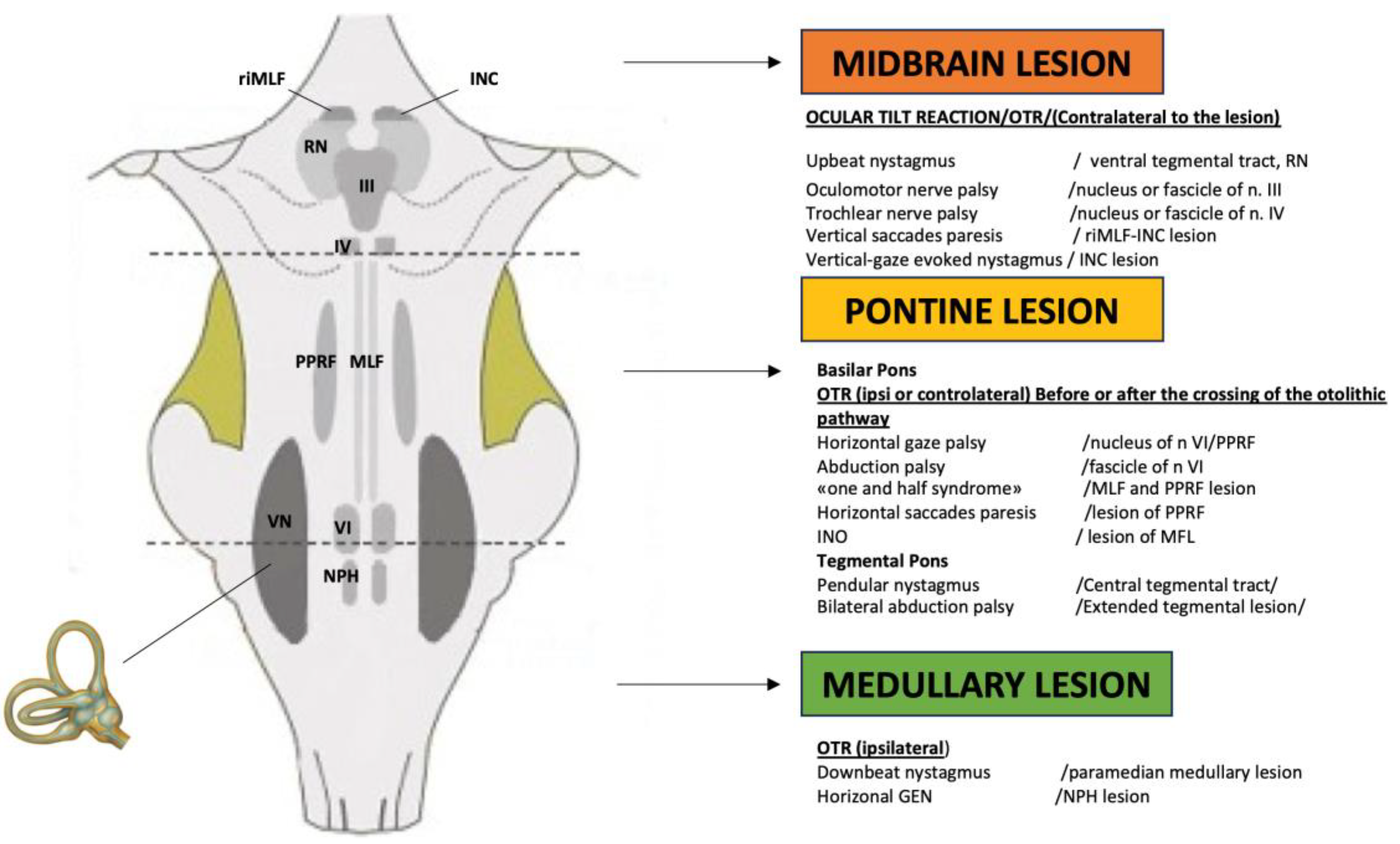

2. Symptoms and Signs in Brainstem Lesions

- -

- rotatory vertigo

- -

- postural instability or unsteadiness

- -

- postural crises

- -

- unclear or blurred vision.

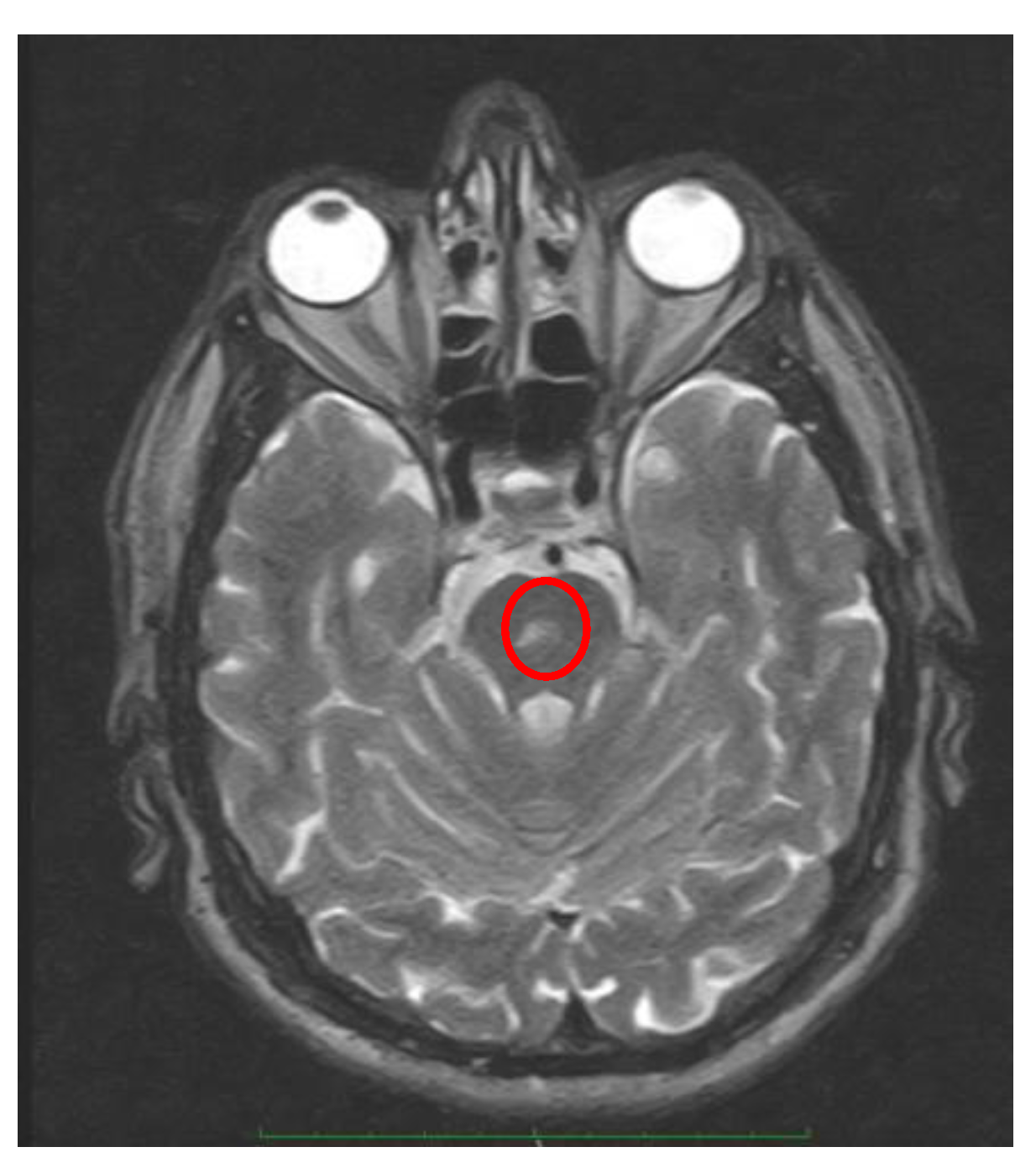

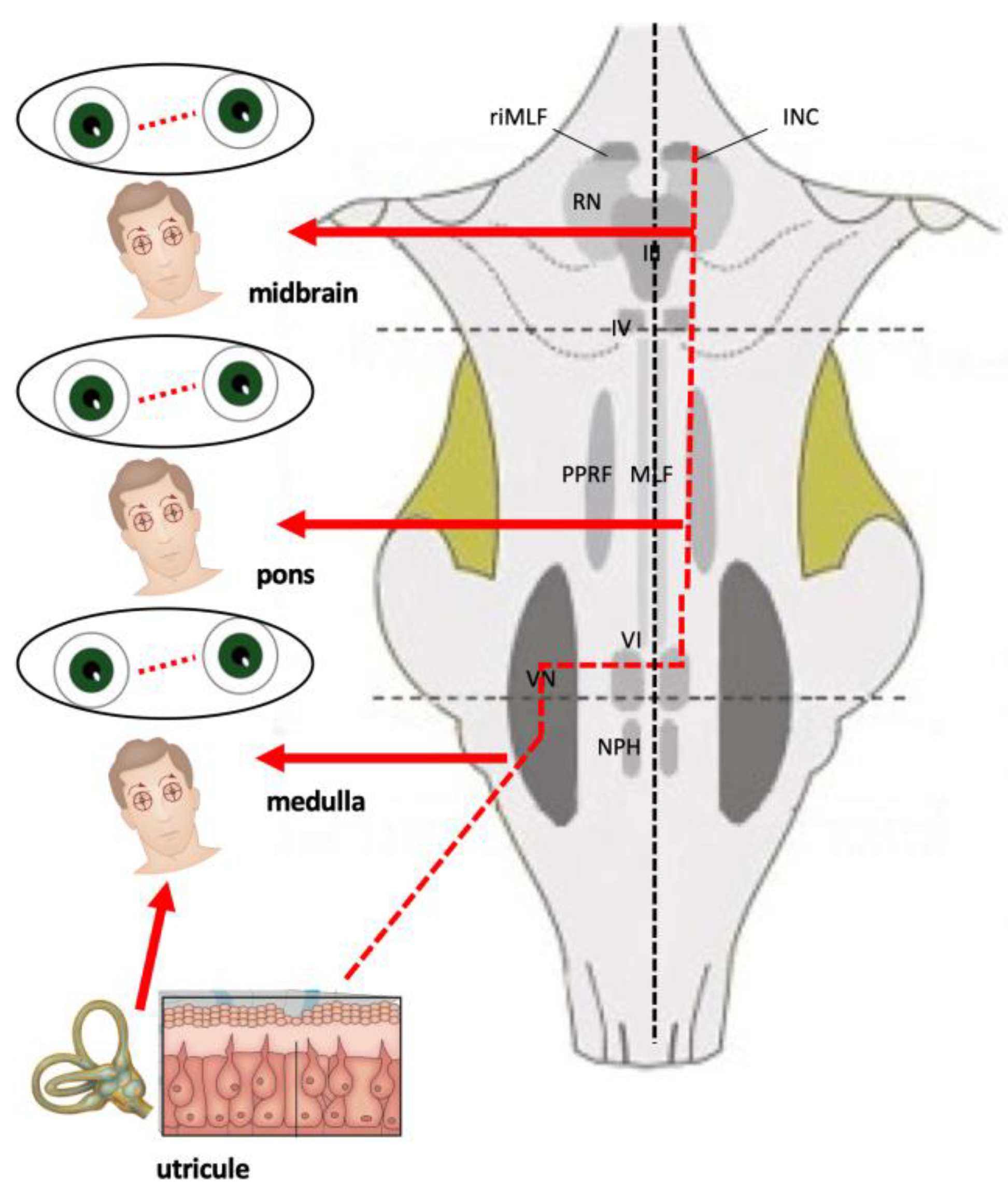

2.1. Abnormal Eye Movements in Medullary Lesions.

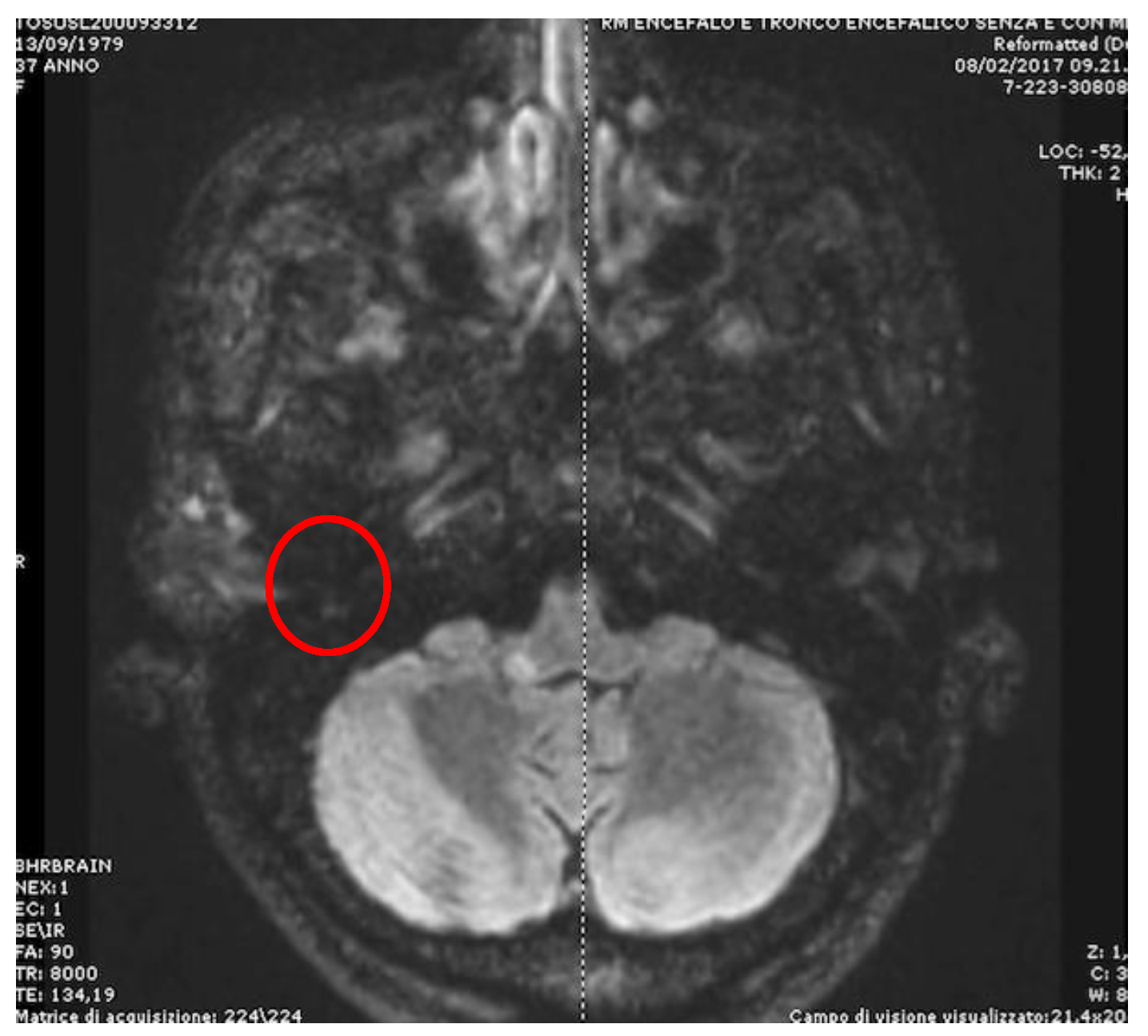

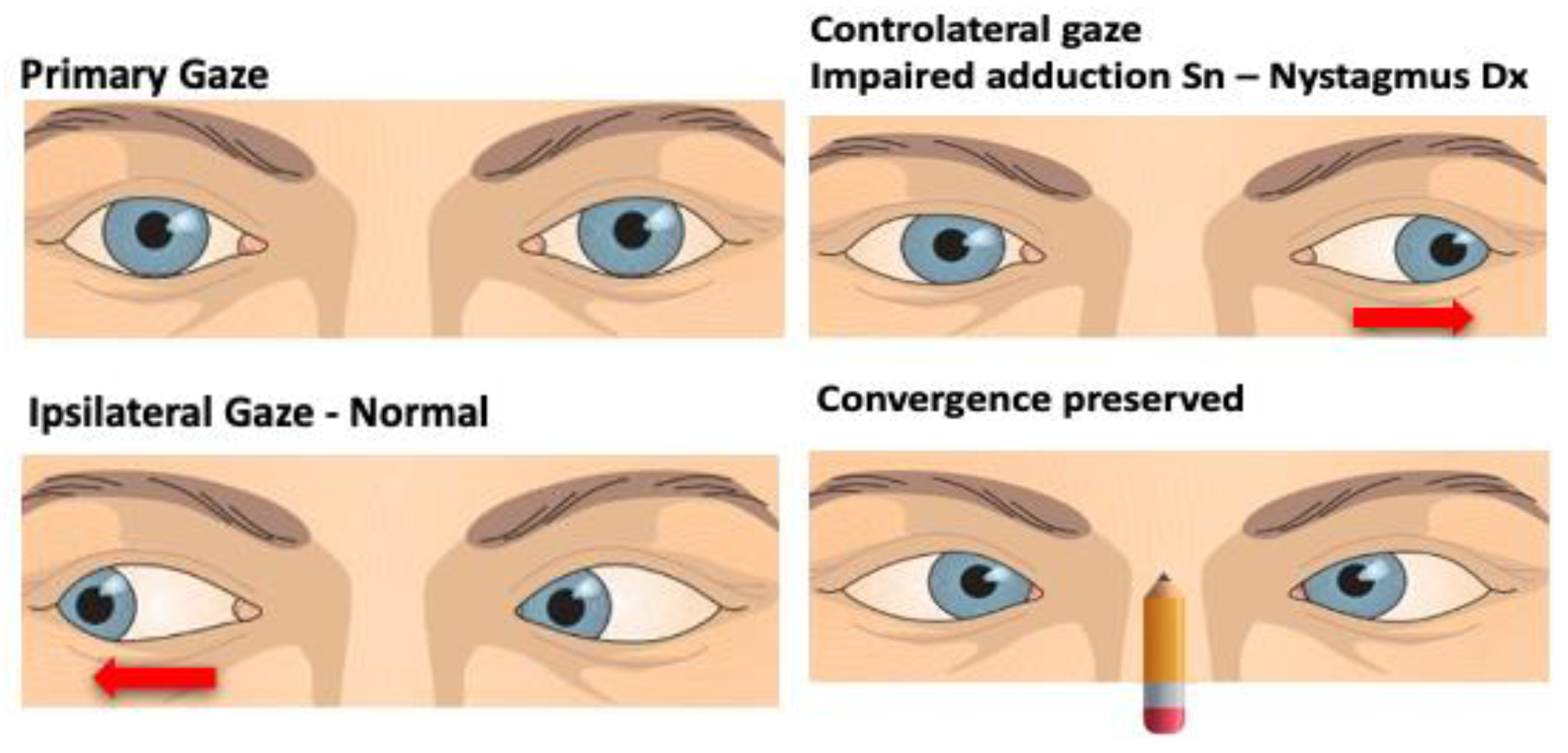

2.2. Abnormal Eye Movements in Pontine Lesions

2.3. Abnormal Eye Movements in Midbrain Lesions

3. Vascular Disorders of the Brainstem

4. Oto-Neurological Signs Associated with Brainstem Involvement

4.1. Central Positional Nystagmus

- The CPN may have any trajectory, but pure downbeat and apogeotropic bidirectional horizontal forms are far more common than upbeat, torsional, or mixed forms.

- Nystagmus which occurs during or shortly after a change of position, with little or no latency, suggests a central cause.

- Failure to fatigue/persistence of nystagmus especially after repeated supine roll test suggests a central cause.

- Intense positional nystagmus with little to no vertiginous sensation may also suggest a central cause.

- Poor or no response to repeated repositioning maneuvers.

- Apogeotropic bidirectional horizontal nystagmus. More commonly associated with cerebellar disease [54], this type of CPN shows no latency and no associated vertigo, lasts as long as the position is maintained and is reproduced by returning the patient to the same position. A brainstem lesion could induce an apogeotropic CPN because of a damage of the connection from nodulus, uvula (and sometimes tonsil) to the vestibular nuclei [12,53,55] (Figure 4).

- Positional downbeating nystagmus (PDN). While in the past the presence of PDN during the head- hanging position and/or in Dix-Hallpike was considered a sign of central vestibular involvement, at the present time PDN is more frequently associated to an apogeotropic variant of posterior canal BPPV [56] or anterior canal BPPV [57]. Two patterns of PDN can be recognized: paroxysmal, with poor or no latency, duration less than 1 minute, and occasionally with a upbeating nystagmus when the patient return to the sitting position reversal; persistent, sometimes preceded by a paroxysmal component [58]. The pathophysiology of PDN during a brainstem lesion is similar to that described for the apogeotropic horizontal positional nystagmus. Recently a case of paroxysmal CPN mimicking posterior canal BPPV was described due to a pontine infarction [59]. Finally, upbeating nystagmus and central bidirectional geotropic nystagmus of central origine are much rarer.

4.2.1. Head Shaking Nystagmus (HSN)

4.2.2. Smooth Pursuit and Saccades Abnormalities in Brainstem Lesions

4.4. Ocular Tilt Reaction (OTR)

- Skew deviation is a vertical misalignment of the eyes due to unilateral impairment of the otolith-ocular reflex. Hypotropia of the eye (on the side of the lesion if the damage affects the peripheral receptor and/or the pathways before their crossing, contralaterally in case of deficit after the commissure) (Figure 5)

- Ocular torsion (in the case of the right labyrinth, counterclockwise torsion from the viewer point of view in case of pre-decussation lesion, clockwise in case of post-decussation lesion)

- Head tilt (to the side of the lesion if the damage affects the peripheral receptor and/or the pathways before their crossing, contralaterally in case of deficit after the commissure).

4.2.2.1. Spontaneous Acquired Nystagmus in Brainstem Lesion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VOR | Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex |

| NPH | Nucleus propositus Hypoglossi |

| NR | Nucleus of Roller |

| OTR | Ocular Tilt Reaction |

| PPRF | Paramedian Pontine Reticular Formation |

| GEN | Gaze Evoked Nystagmus |

| HSN | Head Shaking Nystagmus |

| SP | Smooth Pursuit |

| MLF | Medial Longitudinal Fascicle |

| INO | Internuclear Ophthalmoplegia |

| SD | Skew Deviation |

| riMLF | rostral interstitial Nucleus of the Medial Longitudinal Fasciculus |

| PICA | Posterior-Inferior Cerebellar Artery |

| AICA | Anterior-Inferior Cerebellar Artery |

| ICP | Inferior Cerebellar peduncle |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| HIT | Head Impulse Test |

| CNP | Central Positional Nystagmus |

| PDN | Positional Downbeating Nystagmus |

| BPPV | Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo |

| DBN | Downbeat Nystagmus |

| UBN | Upbeat Nystagmus |

| TN | Torsional Nystagmus |

References

- Leigh, R.J.; Zee, D.S. The Neurology of Eye Movements, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Strupp, M.; Hüfner, K.; Sandmann, R.; Zwergal, A.; Dieterich, M.; Jahn, K.; Brandt, T. Central oculomotor disturbances and nystagmus: A window into the brainstem and cerebellum. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2011, 108, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich, M. Central vestibular disorders. J Neurol 2007, 254, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Ocular motor dysfunction due to brainstem disorders. J Neuroophthalmol 2018, 13, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M. The dizzy patient: Don’t forget disorders of the central vestibular system. Nat Rev Neurol 2017, 13, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kattah, J.C.; Saber Tehrani, A.S.; Roeber, S.; Gujrati, M.; Bach, S.E.; Newman Toker, D.E.; Blitz, A.M.; Horn, A.K.E. Transient Vestibulopathy in Wallenberg’s Syndrome: Pathologic Analysis. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, W.Y.; Gold, D.R. Ocular Motor and Vestibular Disorders in Brainstem Disease. J Clin Neurophysiol 2019, 36, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dieterich, M.; Brandt, T. Wallenberg’s syndrome: Lateropulsion, cyclorotation, and subjective visual vertical in thirty-six patients. Ann Neurol 1992, 31, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Moon, S.Y.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, H.C.; Park, S.H.; Yoon, B.W.; Roh, J.K. Ocular contrapulsion in rostral medial medullary infarction. Neurology 2004, 63, 1325–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Zee, D.S.; Du Lac, S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Nucleus prepositus hypoglossi lesions produce a unique ocular motor syndrome. Neurology 2016, 87, 2026–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Recent advances in head impulse test findings in central vestibular disorders. Neurology 2018, 90, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Seo, J.D.; Choi, Y.R.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S.; Choi, K.D. Inferior cerebellar peduncular lesion causes a distinct vestibular syndrome. Eur J Neurol 2015, 22, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Isolated central vestibular syndrome. Ann New York Acad Sci 2015, 1343, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierrot Deseilligny, C.; Milea, D. Vertical nystagmus: Clinical facts and hypotheses. Brain 2005, 128, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamagoe, K.; Shimizu, K.; Koganezawa, T.; Tamaoka, A. Downbeat nystagmus due to a paramedian medullary lesion. J Clin Neurosci 2012, 19, 1597–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelli, V.; Giannoni, B.; Volpe, G.; Faralli, M.; Marcelli, E.; Cavaliere, M.; Fetoni, A.R.; Pettorossi, V.E. Upbeat nystagmus: A clinical and pathophysiological review. Front Neurol 2025, 16, 1601434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiner, S.; Horn, A.K.; Wadia, N.H.; Sakai, H.; Buttner-Ennever, J.A. The neuroanatomical basis of slow saccades in spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (Wadia-subtype). Prog Brain Res 2008, 171, 575–581. [Google Scholar]

- Nishida, T.; Tychsen, L.; Corbett, J.J. Resolution of saccadic palsy after treatment of brain-stem metastasis. Arch Neurol 1986, 43, 1196–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhidayasiri, R.; Plant, G.T.; Leigh, R.J. A hypothetical scheme for the brainstem control of vertical gaze. Neurology 2000, 54, 1985–1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frohman, E.M.; Frohman, T.C.; Zee, D.S.; McColl, R.; Galetta, S. The neuro-ophthalmology of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol 2005, 4, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwergal, A.; Cnyrim, C.; Arbusow, V.; Glaser, M.; Fesl, G.; Brandt, T.; Strupp, M. Unilateral INO is associated with ocular tilt reaction in pontomesencephalic lesions: INO plus. Neurology 2008, 71, 590–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.U.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Evolution of symmetric upbeat into dissociated torsional-upbeat nystagmus in internuclear ophthalmoplegia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2013, 115, 1882–1884. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, S.; Galetta, S.L. Eye movement abnormalities in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Clin 2010, 28, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S. Internuclear ophthalmoplegia as an isolated or predominant symptom of brainstem infarction. Neurology 2004, 62.9, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Seze, J.; Lucas, C.; Leclerc, X.; Sahli, A.; Vermersch, P.; Leys, D. One-and-a-half syndrome in pontine infarcts: MRI correlates. Neuroradiology 1999, 41, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, A.M.; Rudge, P.; Gresty, M.A.; Du Boulay, G.; Morris, J. Abnormalities of horizontal gaze. Clinical, oculographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings. II. Gaze palsy and internuclear ophthalmoplegia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 1990, 53, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Ying, Z.; Sha, O.; Ding, Y. One-and-a-half syndrome with its spectrum disorders. Quantitative imaging in medicine and surgery 2017, 7, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M.; Sugiuchi, Y.; Shinoda, Y. Brainstem neural circuits triggering vertical saccades and fixation. Journal of Neuroscience 2024, 44, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Strupp, M.; Kremmyda, O.; Adamczyk, C.; Böttcher, N.; Muth, C.; Yip, C.W.; Bremova, T. Central ocular motor disorders, including gaze palsy and nystagmus. J. Neurol 2014, 261, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y.; Buttner-Ennever, J.A.; Straumann, D.; Hepp, K.; Hess, B.J.; Henn, V. Deficits in torsional and vertical rapid eye movements and shift of listing’s plane after uni- and bilateral lesions of the rostral interstitial nucleus of the medial longitudinal fasciculus. Exp Brain Res 1995, 106, 215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen, C.; Rambold, H.; Fuhry, L.; Büttner, U. Deficits in vertical and torsional eye movements after uni- and bilateral muscimol inactivation of the interstitial nucleus of Cajal of the alert monkey. Exp. Brain Res 1998, 119, 436–452. [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen, C.; Rambold, H.; Kempermann, U.; Buttner-Ennever, J.A.; Buttner, U. Localizing value of torsional nystagmus in small midbrain lesions. Neurolog. 2002, 59, 1956–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merwick, A.; Werring, D. Posterior circulation ischaemic stroke. Bmj 2014, 348, g3175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerber, K.A.; Meurer, W.J.; Brown, D.L.; Burke, J.F.; Hofer, T.P.; Tsodikov, A.; Hoeffner, E.G.; Fendrick, A.M.; Adelman, E.E.; Morgenstern, L.B. Stroke risk stratification in acute dizziness presentations: A prospective imaging-based study. Neurology 2015, 85, 1869–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarnutzer, A.A.; Berkowitz, A.L.; Robinson, K.A.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Newman-Toker, D.E. Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome. CMAJ 2011, 183, E571–E592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saber Tehrani, A.S.; Kattah, J.C.; Kerber, K.A.; Gold, D.R.; Zee, D.S.; Urrutia, V.C.; Newman-Toker, D.E. Diagnosing Stroke in Acute Dizziness and Vertigo: Pitfalls and Pearls. Stroke 2018, 49, 788–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanni, S.; Vannucchi, P.; Pecci, R.; Pepe, G.; Paciaroni, M.; Pavellini, A.; Ronchetti, M.; Pelagatti, L.; Bartolucci, M.; Konze, A.; Castellucci, A.; Manfrin, M.; Fabbri, A.; de Iaco, F.; Casani, A.P. Consensus paper on the management of acute isolated vertigo in the emergency department. Intern. Emerg. Med 2024, 19, 1181–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cnyrim, C.D.; Newman-Toker, D.; Karch, C.; Brandt, T.; Strupp, M. Bedside differentiation of vestibular neuritis from central “vestibular pseudoneuritis”. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2008, 79, 458–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattah, J.C.; Talkad, A.V.; Wang, D.Z.; Hsieh, Y.H.; Newman-Toker, D.E. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: Three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke 2009, 2009 40, 3504–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlow, J.A. Distinguishing Peripheral from Central Causes of Dizziness and Vertigo without using HINTS or STANDING J Emerg Med 2024, 67, e622–e633. 67 2024, 67, e622–e633. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, S.; Martinez, C.; Zalazar, G.; Moro, M.; Batuecas-Caletrio, A.; Luis, L.; Gordon, C. The Diagnostic Accuracy of Truncal Ataxia and HINTS as Cardinal Signs for Acute Vestibular Syndrome. Front. Neurol 2016, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarnutzer, A.A.; Edlow, J.A. Bedside Testing in Acute Vestibular Syndrome—Evaluating HINTS Plus and Beyond—A Critical Review. Audiol. Res 2023, 13, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Sohn, S.I.; Cho, Y.W.; Lee, S.R.; Ahn, B.H.; Park, B.R.; Baloh, R.W. Cerebellar infarction presenting isolated vertigo: Frequency and vascular topographical patterns. Neurology 2006, 67, 1178–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloh, R.W.; Yee, R.D.; Honrubia, V. Eye movements in patients with Wallenberg’s syndrome. Ann NY Acad.Sci 1981, 374, 600–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumral, E.; Bayulkem, G.; Evyapan, D. Clinical spectrum of pontine infarction: Clinical—MRI correlations. J. Neurol 2002, 249, 1659–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohman, E.M.; Frohman, T.C.; Fleckenstein, J.; Racke, M.K.; Hawker, K.; Kramer, P.D. Ocular contrapulsion in multiple sclerosis: Clinical features and pathophysiological mechanisms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2001, 70, 688–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, J.; Strupp, M. Central positional nystagmus: An update. J Neurol 2021, 269.4, 1851–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Less talked variants of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Neurol Sci 2022, 442, 120440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, H.J.; Glasauer, S.; Kim, J.S. Central paroxysmal positional nystagmus: Characteristics and possible mechanisms. Neurology 2015, 84, 2238–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schutter, E.; Adham, Z.O.; Kattah, J.C. Central positional vertigo: A clinical-imaging study. Prog Brain Res 2019, 249, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.F.; Tian, J.; Shan, X.; Tamargo, R.J.; Ying, H.; Zee, D.S. The cerebellar nodulus/uvula integrates otolith signals for the translational vestibulo-ocular reflex. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e13981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, N.K.; Kaski, D.; Saman, Y.; Sulaiman, A.A.-S.; Anwer, A.; Bamiou, D.E. Central Positional Nystagmus: A Systematic Literature Review. Front Neurol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.U.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, E.S.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, J.Y.; Kim, J.S. Central positional nystagmus in inferior cerebellar peduncle lesions: A case series. J Neurol 2021, 268, 2851–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttner, U.; Helmchen, C.; Brandt, T. Diagnostic Criteria for Central Versus Peripheral Positioning Nystagmus and Vertigo: A Review. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999, 119, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Imai, T.; Horii, A.; Takeda, N.; Higashi-Shingai, K.; Inohara, H. A case of apogeotropic nystagmus with brainstem lesion: An implication for mechanism of central apogeotropic nystagmus. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010, 37, 742–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Califano, L.; Mazzone, S.; Salafia, F.; Melillo, M.G.; Manna, G. Less common forms of posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2021, 41, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casani, A.P.; Cerchiai, N.; Dallan, I.; Sellari-Franceschini, S. Anterior canal lithiasis: Diagnosis and treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011, 144, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacovino, D.A.; Cherchi, M. Clinical spectrum of positional downbeat nystagmus: A diagnostic approach. J Neurol 2025, 272, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, E.; Jeong, H.S.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Central paroxysmal positional nystagmus mimicking posterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo in pontine infarction: A case report and literature review. J Neurol 2024, 271, 3672–3677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.A.; Lee, H.; Sohn, S.I.; Kim, J.S.; Baloh, R.W. Perverted head shaking nystagmus in focal pontine infarction. J Neurol Sci 2011, 301, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hain, T.C.; Spindler, J. Head-shaking nystagmus. In The Vestibulo-Ocular Reflex and Vertigo; Sharpe, J.A., Barber, H.O., Eds.; Raven Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 217–228. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.D.; Oh, S.Y.; Park, S.H.; Kim, J.H.; Koo, J.W.; Kim, J.S. Head-shaking nystagmus in lateral medullary infarction: Patterns and possible mechanisms. Neurology 2007, 68, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minagar, A.; Sheremata, W.A.; Tusa, R.J. Perverted head-shaking nystagmus: A possible mechanism. Neurology 2001, 57, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.A.; Lee, H.; Sohn, S.I.; Kim, J.S.; Baloh, R.W. Perverted head shaking nystagmus in focal pontine infarction. J Neurol Sci 2011, 301, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Jung, I.; Jung, J.M.; Kwon, D.Y.; Park, M.H.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.S. Characteristics and mechanism of perverted head-shaking nystagmus in central lesions: Video-oculography analysis. Clin Neurophysiol 2016, 127, 2973–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.B.; Boo, S.H.; Ban, J.H. Nystagmus-based approach to vertebrobasilar stroke presenting as vertigo without initial neurologic signs. Eur Neurol 2013, 70, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.L.; Sharpe, J.A.; Morrow, M.J. Paresis of contralateral smooth pursuit and normal vestibular smooth eye movements after unilateral brainstem lesions. Ann Neurol 1992, 31, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fracica, E.; Hale, D.; Gold, D.R. Diagnosing and localizing the acute vestibular syndrome–beyond the HINTS exam. J NeurolSci 2022, 442, 120451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, J.S. Update on the medial longitudinal fasciculus syndrome. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 3533–3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Vidailhet, M.; Gaymard, B. Ipsilateral Saccade Hypometria and Contralateral Saccadic Pursuit in a Focal Brainstem Lesion: A Rare Oculomotor Pattern. Cerebellum 2018, 17, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M. Vestibular syndromes in the roll plane: Topographic diagnosis from brainstem to cortex. Ann Neurol 1994, 36, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, M.C.; Donahue, S.P.; Vaphiades, M.; Brandt, T. Skew deviation revisited. Surv Ophthalmol 2006, 51, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmagyi, G.; Brandt, T.; Dieterich, M.; Curthoys, I.; Stark, R.; Hoyt, W. Tonic contraversive ocular tilt reaction due to unilateral meso-diencephalic lesion. Neurology 1990, 40, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, T.R.D.; Hoyt, W.F. Ocular tilt reaction due to an upper brainstem lesion: Paroxysmal skew deviation, torsion, and oscillation of the eyes with head tilt. Ann Neurol 1982, 11, 537–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, A.R.; Egan, R.A.; Barton, J.J. Pearls & Oy-sters: Paroxysmal ocular tilt reaction. Neurology 2009, 72, e67–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattah, J.C. Update on HINTS Plus, With Discussion of Pitfalls and Pearls. J Neurol Phys Ther 2019, 43, S42–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korda, A.; Zamaro, E.; Wagner, F.; Morrison, M.; Caversaccio, M.D.; Sauter, T.C.; Schneider, E.; Mantokoudis, G. Acute vestibular syndrome: Is skew deviation a central sign? J Neurol 2022, 269, 1396–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gufoni, M. Uphill/downhill nystagmus. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2017, 37, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.N.; Glaser, M.; Brandt, T.; Strupp, M. Downbeat nystagmus: Aetiology and comorbidity in 117 patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2008, 79, 672–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcelli, V.; Giannoni, B.; Volpe, G.; Faralli, M.; Fetoni, A.R.; Pettorossi, V.E. Downbeat nystagmus: A clinical and pathophysiological review. Front Neurol 2024, 15, 1394859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himi, T.; Kataura, A.; Tokuda, S.; Sumi, Y.; Kamiyama, K.; Shitamichi, M. Downbeat nystagmus with compression of the medulla oblongata by the dolichoectatic vertebral arteries. Am J Otol 1995, 16, 377–81. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengart, A.; Hedges, T.R., 3rd; Teal, P.A.; DeWitt, L.D.; Wu, J.K.; Wolpert, S.; Caplan, L.R. Intermittent downbeat nystagmus due to vertebral artery compression. Neurology 1993, 43, 216–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.S.; Yoon, B.; Choi, K.D.; Oh, S.Y.; Park, S.H.; Kim, B.K. Upbeat nystagmus: Clinicoanatomical correlations in 15 patients. J Clin Neurol 2006, 2, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.D.; Jung, D.S.; Park, K.P.; Jo, J.W.; Kim, J.S. Bowtie and upbeat nystagmus evolving into hemi-seesaw nystagmus in medial medullary infarction: Possible anatomic mechanisms. Neurology 2004, 62, 663–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirose, G.; Ogasawara, T.; Shirakawa, T.; Kawada, J.; Kataoka, S.; Yoshioka, A.; Halmagyi, G.M. Primary position upbeat nystagmus due to unilateral medial medullary infarction. Ann Neurol 1998, 43, 403–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, N.; Baloh, R.W.; Tomiyasu, U. Primary position upbeat nystagmus. Clinicopathol Study Neurol 1977, 27, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Bronstein, A.M.; Gresty, M.A.; Rudge, P.; du Boulay, E.P. Torsional nystagmus. A neuro-otological and MRI study of thirty-five cases. Brain 1992, 115, 1107–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrow, M.J.; Sharpe, J.A. Torsional nystagmus in the lateral medullary syndrome. Ann Neurol 1988, 1988 24, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.R.; Lueck, C.J. Hemi-seesaw nystagmus in lateral medullary syndrome. Neurology 2013, 80, 1261–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halmagy, G.; Aw, S.; Dehaene, I.; Curthoys, I.; Todd, M. Jerk-waveform see-saw nystagmus due to unilateral meso-diencephalic lesion. Brain 1994, 117, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi, T.; Ikeda, T.; Kikuchi, S. Periodic alternating nystagmus caused by a medullary lesion in acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Otol Neurotol 2014, 35, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averbuch-Heller, L.; Zivotofsky, A.Z.; Das, V.E.; DiScenna, A.O.; Leigh, R.J. Investigations of the pathogenesis of acquired pendular nystagmus. Brain 1995, 118, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresty, M.A.; Ell, J.J.; Findley, L.J. Acquired pendular nystagmus: Its characteristics, localising value and pathophysiology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 1982, 45, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Shaikh, A.G. Acquired pendular nystagmus. J Neurol Sci 2017, 375, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambold, H.; Kömpf, D.; Helmchen, C. Convergence retraction nystagmus: A disorder of vergence? Ann Neurol 2001, 50, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, F.; Hodgson, T.L.; Mort, D.; Kennard, C. Ocular flutter associated with a localized lesion in the paramedian pontine reticular formation. Ann Neurol 2001, 50, 413–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.P.; Gold, D.R.; Otero-Millan, J.; Huang, B.R.; Zee, D.S. Pendular oscillation and ocular bobbing after pontine hemorrhage. Cerebellum 2021, 20, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurnani, B.; Kaur, K.; Chaudhary, S.; Gandhi, A.S.; Balakrishnan, H.; Mishra, C.; Gosalia, H.; Dhiman, S.; Joshi, S.; Nagtode, A.H.; Jain, S.; Aguiar, M.; Rustagi, I.M. Nystagmus in Clinical Practice: From Diagnosis to Treatment—A Comprehensive Review. Clinical Ophthalmol 2025, 1617–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Examination | Search for |

|---|---|

| Head Posture | Head Tilt |

| Eye Movements Position of the eyes Straight ahead, look to the right, left, upward and downward, Cover test |

Primary misalignment, Spontaneous nystagmus Gaze function End point nystagmus |

| Smooth Pursuit | Saccadic, |

| Reduction of gain | |

| Saccades | Latency, velocity, accuracy |

| VOR functionality Clinical Head Impulse Test |

Presence of corrective saccades |

| Visual fixation suppression of the VOR | No suppression of VOR (mainly occur in cerebellar diseases) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).