1. Introduction

Traditionally considered a condition of middle-aged and older adults, MI is increasingly affecting younger individuals—often in the absence of conventional risk factors such as long-standing hypertension, diabetes, or established atherosclerosis. This emerging trend raises important questions about the adequacy of existing cardiovascular risk models and suggests the presence of alternative, underrecognized contributors to early-onset atherothrombotic disease.

In recent years, attention has turned to a range of novel risk factors that may play a disproportionately large role in the pathogenesis of MI in young adults. These include genetic variants (e.g., elevated lipoprotein(a)), inflammatory and autoimmune processes, thrombophilic states, the use of recreational substances (notably cocaine and cannabis), and persistent psychosocial stress. Lifestyle patterns unique to younger populations—such as sleep deprivation, disordered eating, and digital-era stress—also appear to exert independent cardiovascular effects.

Moreover, sex-specific aspects, especially the increasing recognition of MI in young women—often presenting without obstructive coronary disease—further complicate the clinical picture and highlight the limitations of traditional diagnostic and preventive strategies.

Given the potentially devastating socioeconomic consequences of MI of young people there is a pressing need to better characterize the spectrum of risk factors in this population. Such understanting will inform targeted prevention and long term strategy for this.

This review explores the evolving landscape of MI in young adults, focusing on the expanding spectrum of risk factors and pathophysiological mechanisms. By reevaluating current paradigms and integrating emerging evidence, we aim to better understand, identify, and ultimately prevent premature cardiovascular events in this unique population.

2. Epidemiology of Premature Myocardic Infarctions

In recent years, the clinical landscape of MI has undergone a noteworthy demographic shift. Once considered predominantly a disease of older adults, MI is now increasingly observed in younger individuals — often in their 30s or 40s — who may lack long-standing chronic conditions traditionally associated with coronary artery disease. This evolving epidemiological profile has drawn growing attention in cardiovascular research and practice [

1].

Current estimates suggest that approximately one in ten patients hospitalized for acute MI is under the age of 55. While men continue to represent the majority of these cases, recent data highlight a worrying trend: the incidence among young women appears to be rising or, at the very least, not declining at the same rate. Compounding this, women are more likely to present with atypical symptoms, experience delays in diagnosis, and suffer worse in-hospital outcomes [

2].

Geographical and socioeconomic differences play a significant role in the distribution of premature MI. In some high-income countries, incidence rates have plateaued or slightly decreased, largely due to better primary prevention. However, in many low- and middle-income regions, the number of young adults affected by MI remains substantial and, in some cases, continues to grow — reflecting disparities in healthcare access, education, and exposure to modifiable risk factor [

3].

Although traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as tobacco use, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes are still prevalent among young MI patients, they often coexist with newer, underrecognized contributors. Emerging evidence implicates psychosocial stress, recreational drug use, sedentary behavior linked to modern work environments, and proinflammatory conditions in the early development of atherothrombotic events. In addition, genetic susceptibilities — such as elevated levels of lipoprotein(a) or familial hypercholesterolemia — may play a disproportionately large role in this group, especially in the absence of overt lifestyle-related risk [

4].

The rising incidence of MI in younger populations, combined with their unique clinical characteristics and risk profiles, underscores the limitations of current cardiovascular risk assessment tools, which were largely developed based on older cohorts. Addressing this growing challenge requires not only earlier identification of at-risk individuals but also a broader understanding of the multifactorial nature of premature coronary disease — one that integrates biological, behavioral, environmental, and social dimensions. [

5]

3. Global Incidence and Prevalence

Determining the actual prevalence of coronary artery disease (CAD) in young adults remains a significant challenge, mainly because the clinical characteristics of both atherosclerotic and non-atherosclerotic forms are still not clearly delineated. This is particularly evident in cases of myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA), where the absence of standardized diagnostic protocols and limited use of intracoronary imaging often results in misdiagnosed or overlooked non-plaque mechanisms [

6].

Available epidemiological data on MI in younger individuals are sparse. Findings from the Framingham Heart Study illustrate a steep age-related increase in MI incidence among men—from 12.9 per 1,000 in those aged 30–34 to 71.2 per 1,000 in the 45–54 group. Women show consistently lower rates across the same age brackets. Notably, over a quarter of the myocardial infarctions in this study were asymptomatic, with unrecognized events occurring more frequently in women.[

7]

In South Asia, especially in India, early-onset CAD presents another layer of complexity [

8]. Data from a cohort of 877 patients indicated that roughly a third were diagnosed before turning 45. In over 90% of these cases, common lifestyle-related risk factors were present, including low fiber intake, smoking, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, alcohol use, sedentary habits, psychosocial stress, and central obesity. Notably, risk profiles differ by gender: young women with MI tend to have higher rates of comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes, depression, and heart failure, whereas men are more often affected by physical inactivity and elevated cholesterol levels. Evidence from the VIRGO and GENESIS-PRAXY studies also suggests that young women may experience MI via mechanisms that are less well understood, recover more slowly, and face a higher likelihood of complications, readmission, or even death compared to men their age [

9,

10].

Although the overall incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) has declined in the UK, the trend does not necessarily reflect what is happening among younger adults. Data between 1992 and 2012 show very low CHD rates in the 35–44 age group—0.5% in men and 0.18% in women—but prevalence increases sharply in older age groups. Younger individuals may be underdiagnosed, likely due to less typical symptom presentation and a reduced tendency to seek medical evaluation. As a result, only 3% of all CHD diagnoses are made in people under 40, a figure that may underrepresent the true burden in this demographic [

11,

12].

Modifiable risk factors remain central to the rising trend in early-onset CAD. Smoking, in particular, is widespread among young adults, with rates climbing to nearly 10%. Young women in the UK have been reported to smoke more heavily and for longer durations, potentially diminishing the protective cardiovascular effects of estrogen [

13]. In parallel, obesity has surged among children and young adults, with rates tripling in the last two decades. Cocaine use, another major concern, is a recognized precipitant of chest pain and myocardial infarction in younger people and continues to be frequently implicated. Taken together, these patterns suggest that while CAD might appear to be declining in the general population, a significant and growing risk is emerging among younger individuals—one that deserves much closer attention. [

14,

15]

4. Traditional VS Non Traditional Risk Factors

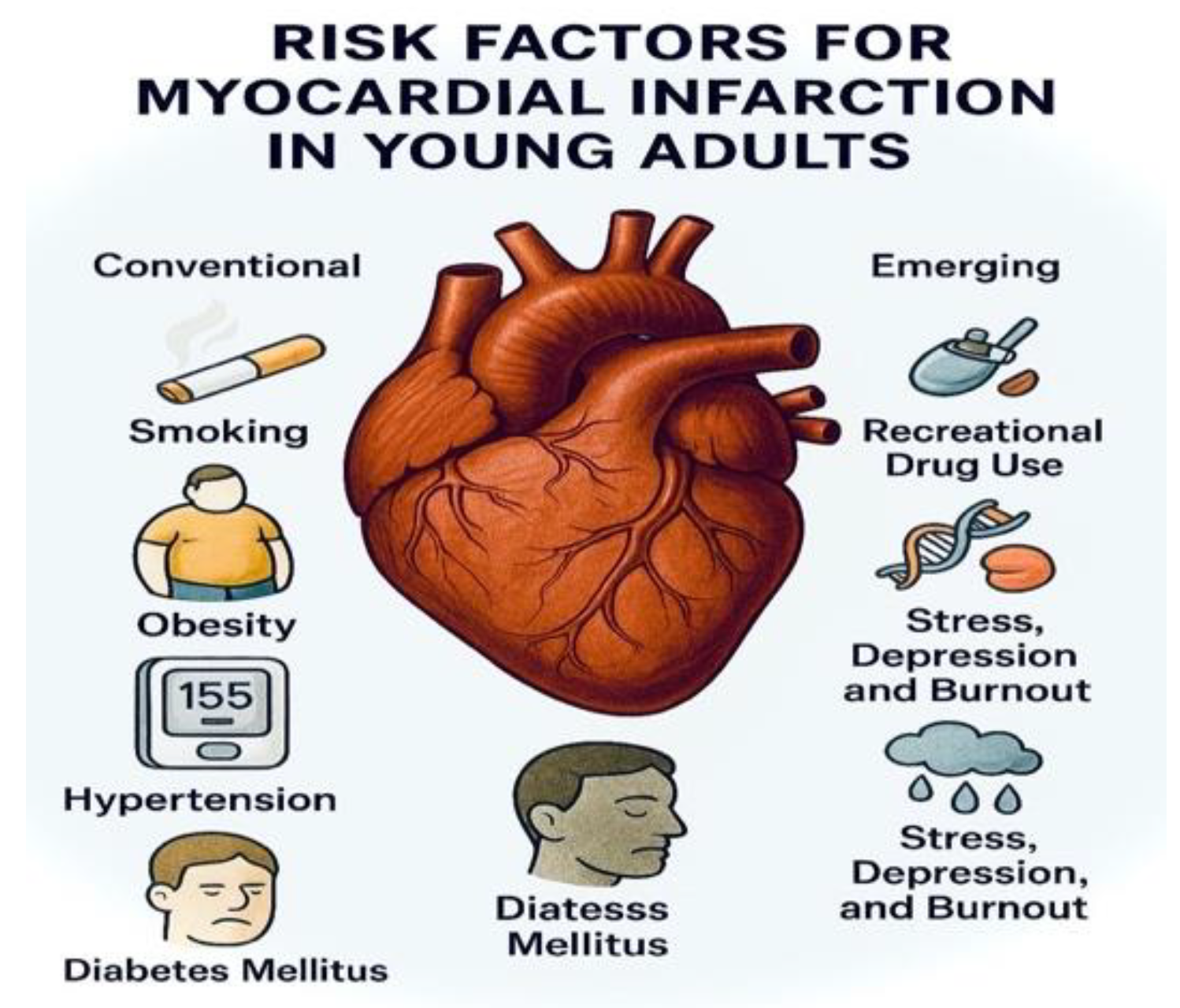

Young patients who experience myocardial infarction share with older individuals the classic cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia. However, a significant proportion of these younger patients differ from their older counterparts in terms of emerging risk factors. Young patients are frequently users of recreational drugs, and may present with various autoimmune diseases, familial hypercholesterolemia, elevated lipoprotein levels, as well as psychosocial factors such as stress, depression, and burnout, all of which play an increasingly recognized role in the pathogenesis of myocardial infarction in this age group.[

14,

15]

4.1. Conventional Cardiovascular Risk Factors Associated with Young AMI:

4.1.1. Dyslipidemia

Dyslipidemia is an important risk factor in young people who suffers AMI, with over 80% having at least one anormal lipid along other risk factors [

5]. Some studies data reveal that lipid profiles have improved in some European young adult population, but AMI in this patients continues to rise [

4].

In a cohort of adults under 40 age who suffers an AMI, 40 percent of them have abnormal levels of lipid, most commonly hypertriglyceridemia, high LDL-c and low HDL-C [

16].

A Korean study found that statin use implicated a higher AMI risk than non-using. Non statin users how have LDL-C >120mg/dL faced a 33% higher AMI risk vs those with <80mg/dL, and the statin users with LDL-C <80mg/dL had a 66% higher risk then non user with similar LDL-C value. Also, the HDL-C remains a consistent risk marker in younger adults.[

16,

17,

18,

19].

4.1.2. Hypertension

Hypertension contributes significantly to the development of atherosclerosis in the young. While often asymptomatic, elevated blood pressure is frequently underdiagnosed and untreated in this age group, exacerbating cardiovascular risk.[

20]. Results shows that young people received a diagnosis slower compared to older patients.

Delayed diagnosis allows vascular damage to progress silently, amplifying long term cardiovascular risk [

21].

Global, the prevalence of undiagnosed hypertension is high. A Indonesia study reveal that 55% of men and 44% of women age 26-35 age were undiagnosed [

22].

4.1.3. Smoking

Cigarette using promote endothelial inflammation and dysfunctions followed by thrombosis and lipid oxygenation, accelerating atherosclerosis without an important plaque burden.

Smoking remand one of the most common risk factor for AMI among all people. In a recent study, 52.5% from individual were smokers and in a Danish register data of patients, age 30-49, 74% were current smokers comparing with the rest of traditional risk factors (10% hyperlipemia, 15% hypertension, 7% diabetes). Recent studies reveals that a 9 fold in man to 13 fold in women increased AMI risk [

14].

Multiple studies confirm that active smoking is an important cardiovascular risk factor for younger women than man. In an UK cohort study revealed that women had an 13 higher risk of AMI comparing to 8,5% in man [

23].

The smoking cessation also have an important role, young people who quits smoking with one year post AMI had 70% lower all causes of mortality and 80% lower cardiovascular mortality over 11 year.

[14,24]

4.1.4. Obesity

Recent studies shown a strong association between obesity and AMI in young people. Data from numerous studies with AMI reveal that obesity is present in 78% of the patients who suffers an AMI at a young age. In young women, a BMI >30 increased the risk of AMI nearly by 4,7 fold (HR 4,71, 95% CI: 3,88-5,72) and also associated with higher cardiovascular mortality.[

25,

26]

4.1.5. Diabetes Mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is an important modify risk in young people who suffer AMI. A study from 2024 reveals that glycemic variability in patients with AMI is correlated with worse outcomes and higher rate of in-hospital mortality. The mortality of patients who suffers from diabetes mellitus with high glycemic values is increased with 1,25—3,40 [

27]. Glycemic fluctuations were associated with higher in-hospital mortality, most notably among AMI patients whose admission blood glucose was within the normal range.

Figure 1.

Traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factor in young.

Figure 1.

Traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factor in young.

4.2. Novel Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Young

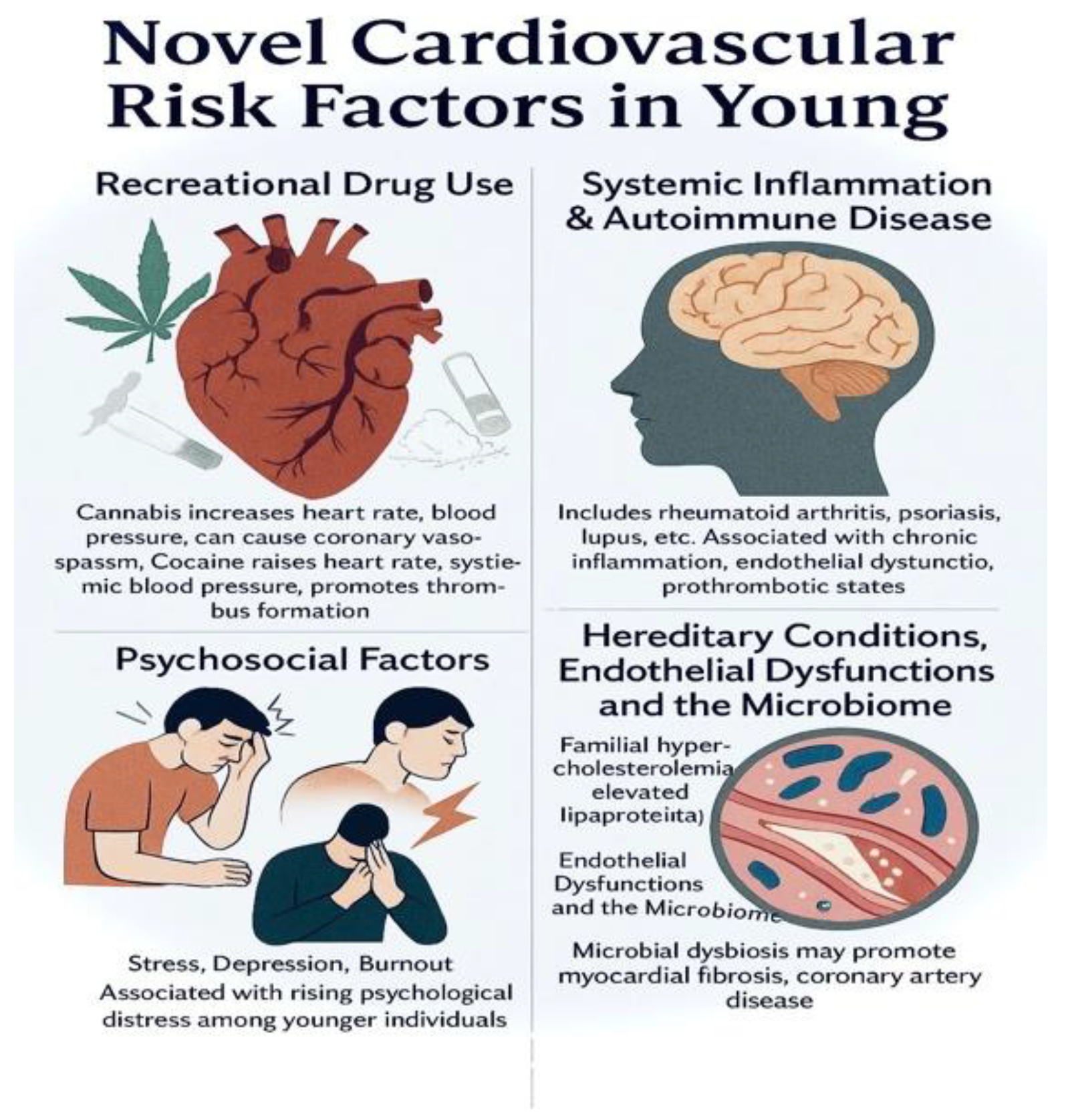

4.2.1. Recreational Drug Use

In the last years, the recreational drug use is recognized as an independent factor for AMI among young people, especially cannabis and cocaine use [

28].

Cocaine stimulates alpha-1 and beta-1 adrenergic receptors, increasing heart rate and systemic blood pressure, which in turn elevates myocardial oxygen demand. It can also induce coronary vasospasm, hours after use, particularly in epicardial vessels, reducing myocardial oxygen supply. Furthermore, it activates platelets and plasminogen, contributing to thrombus formation [

29,

30,

31]. Chronic use and the acute use have a different impact on cardiovascular system, unlike its chronic consequences, the acute cardiovascular impact of cocaine has been extensively documented. As a powerful stimulant, cocaine use has been linked to electrocardiographic changes, heightened blood pressure, arrhythmias, and AMI. The likelihood of MI in cocaine users is shaped by both underling cardiac risk factors and high-risk behaviors. Mechanistically, cocaine can provoke acute events through multiple pathways, including inhibition of cardiac sodium and potassium channels and promotion of coronary artery spasm or vasoconstriction. By contrast, the long-term cardiovascular effects of cocaine remain less clearly defined, with previous studies reporting inconsistent results [

29].

Cannabis increases heart rate and blood pressure and contributes to platelet aggregation, endothelial dysfunction, and coronary vasospasm.

In AMI registries, 10.7% of young patients reported cocaine and/or cannabis use. A French study found 12.6% of AMI patients tested positive for drug use, 34% of whom were under 50. [

32,

33]

Figure 2.

Novel cardiovascular risk in young.

Figure 2.

Novel cardiovascular risk in young.

4.2.2. Systemic Inflammation and Autoimmune Disease

Systemic inflammation and autoimmune disease make an important impact in the patient’s life, and a more important impact in the life of a young patients who suffers AMI.

Young AMI registry data reveal that 2,5% of patients under age 50 had an autoimmune disease or systemic inflammation (SID), such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus or multiple sclerosis. These patients where more often women and had hypertension comparing to others. Patients under age 50 with SID suffers 2 more higher all-cause mortality over 11 years [

34].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease that increases cardiovascular (CV) mortality by up to 50%, with a risk of acute coronary syndromes comparable to type 2 diabetes [

35]. Beyond traditional factors, persistent systemic inflammation drives endothelial dysfunction, accelerates atherosclerosis, and promotes unstable plaque formation. The distinct CV profile in RA includes myocardial infarction, sudden death, and silent ischemia [

36]. The “lipid paradox” — low lipid levels despite high CV risk — further reflects the central role of inflammation, while targeted anti-inflammatory therapy can reduce this burden [

37].

In systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), young patients—particularly women under 45—carry a disproportionately high risk of myocardial infarction, with incidence rates up to ten times greater than in the general population [

38]. This vulnerability is fueled not only by conventional risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia, but also by disease-specific drivers: persistent systemic inflammation, immune-mediated vascular injury, high disease activity, long-term corticosteroid exposure, and antiphospholipid antibodies. These mechanisms accelerate atherosclerosis, destabilize plaques, and heighten thrombotic potential, enabling severe coronary events to occur even in the absence of traditional risk profiles. Prompt control of inflammation and proactive cardiovascular surveillance are therefore critical to reducing the burden of premature AMI in SLE [

38].

In the last 5 years, multiple cohort studies and meta-analyses have confirmed that young adults with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) or axial spondylarthritis face a significantly higher risk of myocardial infarction—even after adjusting for traditional factors [

39]. Persistent systemic inflammation (TNF-α, IL-17), endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and frequent NSAID use accelerate atherosclerosis, while metabolic syndrome and smoking amplify this risk. TNF inhibitors appear protective [

40], with real-world data linking effective inflammation control to fewer acute coronary events. Early cardiovascular screening and aggressive disease management are essential to reduce premature MI in AS patients.

Psoriasis is a systemic, immune-mediated disease that accelerates atherogenesis and raises ASCVD risk beyond traditional factors, with signal strongest in moderate–severe skin disease. Mechanistically, chronic IL-17/TNF-α–driven inflammation promotes endothelial dysfunction, arterial stiffness, and pro-thrombotic pathways—biologic plausibility that aligns with higher MI/ACS rates in observational cohorts and contemporary reviews [

41]. Recent evidence links disease severity and duration to coronary microvascular dysfunction—an early substrate for type 1 MI—supporting the concept of “premature” coronary disease in younger patients with long-standing psoriasis [

42]. Therapeutically, large real-world and meta-analytic data suggest patients treated with modern biologics (anti-TNF, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-23) experience lower incident cardiovascular events versus oral/non-biologic therapy, consistent with the inflammation-hypothesis; signals are not uniform across all agents (eg, anti-IL-12/23) [

43].

Medium–large-vessel inflammation can directly involve coronaries—causing ostial stenoses, aneurysms, thrombosis, and rapid restenosis—on top of diffuse endothelial injury and pro-thrombotic signaling. The result is acute coronary events at ages where atherosclerosis alone would be unlikely. Takayasu arteritis (teens–young women): Contemporary reviews show frequent coronary involvement (esp. ostial/proximal lesions) with MI as a major cause of TAK-related death; multimodality imaging (CTCA/CMR) refines detection [

44]. Kawasaki disease (KD) (childhood) → young-adult MI: Persistent or giant coronary aneurysms carry long-term atherosclerotic change and MI risk years after the acute illness [

45]. ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV): Recent cohort/meta-analytic data show substantially higher cardiovascular events, including MI; risk peaks in the months after diagnosis and remains elevated [

46]. Polyarteritis nodosa (PAN): Medium-vessel necrotizing vasculitis with documented coronary arteritis/occlusions and MI—even in young patients—though uncommon overall [

47].

Systemic inflammation can profoundly affect lipid metabolism, exemplified by the paradoxical LDL-C rise seen after inflammation control in rheumatoid arthritis. In the Young-MI registry, patients with SID had similar overall lipid profiles to those without SID but showed a tendency toward higher triglycerides (P = 0.04). Despite comparable renal function at presentation, SID patients had significantly lower peak troponin levels during the index MI (P = 0.003), suggesting possible differences in myocardial injury patterns [

34,

48].

Studies also reveal that autoimmune disease contributes to AMI risk with the endothelial disfunction made from the inflammation, the immune complex deposition and the prothrombotic states. [

34,

49]

Among inflammatory markers, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) has uniquely transitioned into routine cardiovascular risk assessment, reflecting hepatic response to IL-6 stimulation. While CRP itself is not a causal driver of atherothrombosis, upstream mediators such as IL-1 and IL-6 actively promote plaque development and destabilization. Other candidates — myeloperoxidase (MPO), lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A₂ (Lp-PLA₂), and trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) — highlight diverse inflammatory and metabolic pathways linking immune activation to vascular injury. MPO fosters oxidative modification of LDL and impairs HDL function, Lp-PLA₂ amplifies oxidative stress within plaques, and TMAO, generated from gut microbial metabolism of red meat and eggs, accelerates foam cell formation, platelet activation, and thrombosis. Despite strong mechanistic evidence, these markers remain largely research tools; their integration into everyday risk stratification for young AMI patients awaits effective targeted interventions and broader validation across populations [

50,

51].

Post-AMI autoimmune responses such as Dressler syndrome is an important factor to reveal the importance of autoimmune system responses against myocardial neo-antigens formed as a respond to AMI [

52].

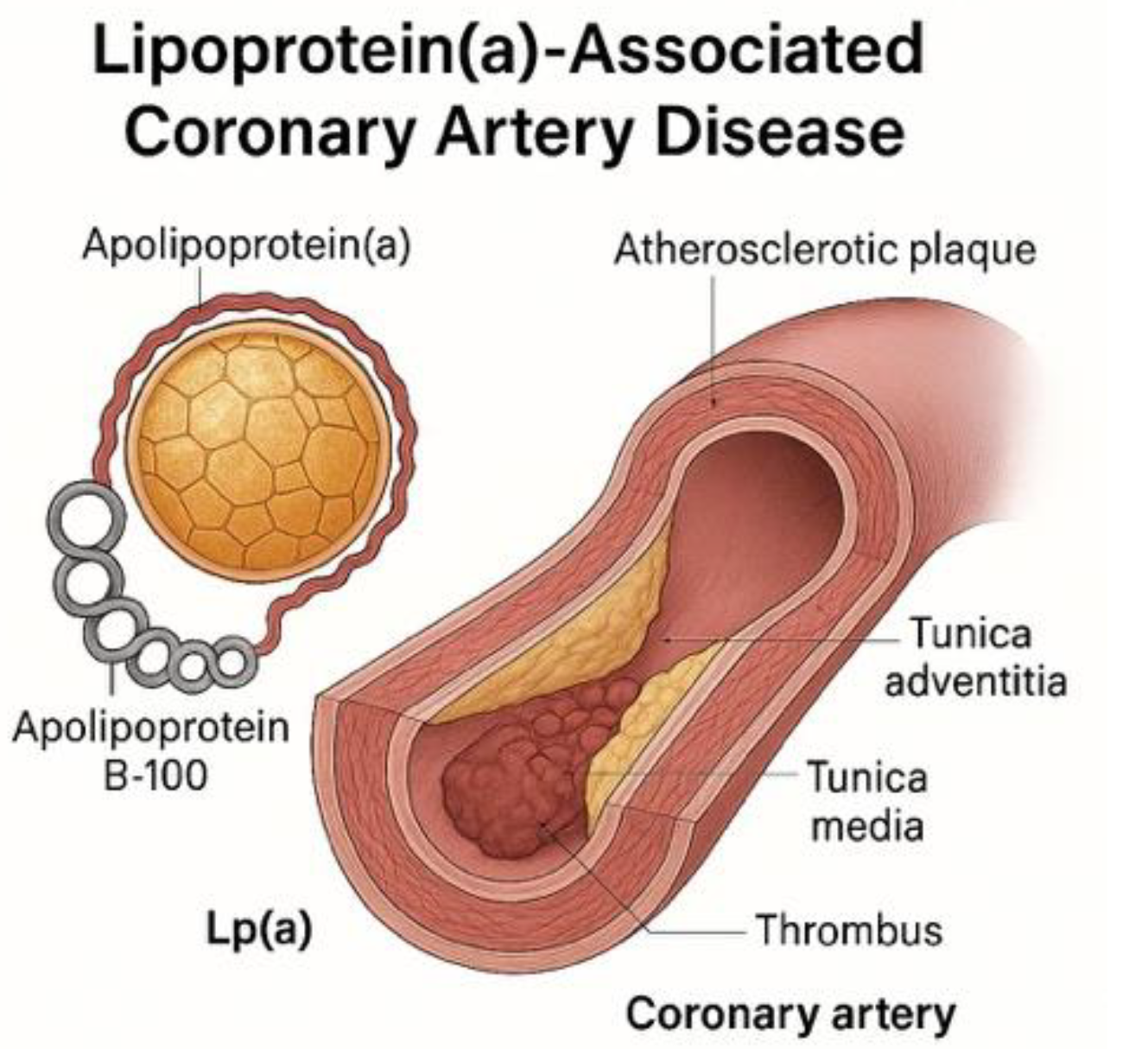

4.2.3. Hereditary Conditions: Hypercholesterolemia and Lipoprotein(A)

The prevalence of genetic lipid disorders makes an important role and relation to an early AMI due to the importance of an early diagnosis to initiation the treatment and prevent the AMI.

Familial hypercholesterolemia has a high prevalence among young AMI cohort, 1-5% are heterozygous for familial hypercholesterolemia (comparing to 0,5% in the rest of population). This pathology increases the risk of AMI in young age with 15-20 more comparative with the patients who doesn’t have familial hypercholesterolemia, and the patients who have it, have a 2.3 more risk of recurrence. A study with 690 patients reveal that patient with familial hypercholesterolemia have more likely a three vessel disease (p=0.007), and a higher thrombus burden and final TIMI slow/no-flow (p=0.027) comparing to the unlikely patient who suffer from the disease (p=0,006). [

53,

54,

55]

Lipoprotein A (LpA) is a stronger independent risk factor in young people with AMI due to pro-atherogenic and pro-thrombotic properties, being the particle who carries cholesterol molecules. High levels of LpA are correlated to 2-3 much higher risk of AMI comparing to normal levels. Also, levels >50mg/dL affects 20-25% of global individuals, and a value more than 180 mg/dL place the patients at a very high risk of AMI. US multi-ethic cohort revels that high levels of lipoprotein(A) is linked to a very high risk of AMI. This lipoprotein may be in the future a screening test for preventing the AMI in patients of any age [

56,

57,

58].

Other genetics lipid disorder implicated in AMI at young age are represented by ApoA5 polymorphism who is linked to higher values of triglycerides and like that, they increase the risk of AMI making also a predictor of yearly AMI. [

56,

58,

59]

Figure 3.

structure of Lipoprotein(a).

Figure 3.

structure of Lipoprotein(a).

4.2.4. Psychosocial Factors: Stress, Depressions, Burnout

Increased responsibilities, academic and career pressures, and social isolation contribute to rising psychological distress in younger populations

Meta-analyses found that depression has an 24% prevalence in patients who suffer an AMI, 12% have anxiety and 10% of them suffers from PTSD. Early psychological intervention has a very important role in prevention and recovery to those who suffers an AMI. [

60,

61].

4.2.5. Endothelial Dysfunctions and the Microbiome

The idea that microbiome is a important factor in development the cardiovascular disease increase in the last decade due to the influence of the metabolic system. Microbiome can use trimethylamine N-oxide, short chain fatty acids and bile acid pathways causing heart failure, atherosclerosis, hypertension, myocardial fibrosis and coronary artery disease [

58,

62].

Viral (e.g., cytomegalovirus, influenza A, hepatitis C) [

63] and bacterial (e.g., Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori) infections have been implicated in atherosclerosis via endothelial activation, cytokine upregulation, and heat shock protein expression [

64,

65]. While infection-driven inflammation is a plausible contributor, evidence from the Tsimane population — with high hsCRP prevalence but minimal coronary calcification — suggests that inflammation alone, in the absence of conventional risk factors, may be insufficient to promote coronary artery disease [

66].

A 2025 study found AMI patients had blood samples enriched in Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, Actinobacteriota and Bacteroides, however, the clinical significance of those in AMI remained unclear and warrant for further investigation. [

62]

Dysbiosis, including reduced microbial diversity and a shift toward Bacteroides-dominant profiles, may promote myocardial fibrosis and coronary artery disease. Further studies are needed to clarify the microbiota’s role in AMI. [

67]

HIV infections have an important role in AMI in young patients. Despite modern antiretroviral therapy, young people living with HIV face a 1.5–3× higher risk of myocardial infarction than HIV-negative peers, often occurring a decade earlier. The culprit is not simply atherosclerosis, but a triple hit [

68]

Immune dysregulation – persistent monocyte/macrophage activation and cytokine release (IL-6, TNF-α) destabilize plaques even when viral load is undetectable [

68,

69].

Endothelial injury – HIV proteins and chronic inflammation drive microvascular dysfunction, creating fertile ground for both type 1 and type 2 MI [

69].

Therapy-related effects – while integrase inhibitors are generally safer, certain regimens, especially recent abacavir exposure, have been linked to abrupt rises in MI risk [

69].

5. Clinical Presentations and Diagnostic Challenges

Typical symptomatology of presentations are representation of chest pain with or without radiating in arms or jaw, diaphoresis, dyspnea and dizziness. The atypical symptoms are representation of digestive symptoms like epigastric pain, indigestion, nausea or vomiting; neurological symptoms like fatigue, neck or back pain, or even syncopal episode are more often present in young women (90% of women are having atypical symptoms) [

70].

Some meta-analysis found that 11,6% of all gender patients who suffers AMI are presenting atypical symptoms and 33,6% are having no chest pain. Small studies reveal that 69% of young patients with AMI have no chest pain before the event [

70].

These atypical symptoms of presentation lead to misdiagnosis of this patients, which can increase in-hospital mortality (19% in atypical symptoms vs 3% in typal symptoms) due to the time of interventions, and because of that, is very important to know the non-specific symptoms for making a more rapidly intervention [

71].

The different batwing symptomatology is related to neural modulation and acute inflammation or ischemic changes cause by the epicardial coronary artery ischemic patterns [

72].

Duet o the atypical symptoms on presentation, time to diagnosis is often delayed, and the time to PCI is more often longer.

A South Asian registry showed that young patients with AMI have 125 minutes longer waiting time of the medical service presentation comparing to elderly patients and a European study reveal that the uncertainty diagnosis in primary care lead to longer time of waiting in younger patients [

73].

In Japanese studies reveal that this problems persist, and because of that, the patients fail to meet the guideline-recommended benchmarks for early intervention: <10 minutes door-to-ECG and <90 minutes door-to-PCI [

74].

These delays in diagnosis and PCI increase the risk of major adverse cardiac events, and may lead to long-term reductions in quality of life [

75,

76,

77].

The mortality rate in-hospital in young patients who suffer AMI is between 0,7% to 7%, typically lower than older people, but in short-term (30 days), young patients without standard risk factors has 30 more higher risk mortality. A cohort study found that the mortality rate is 120% higher in patients with STEMI comparing with N-STEMI where the risk is 12 more higher [

5,

78]

On long term mortality (one year), the patients <40 age have similar all-cause mortality comparing to those of 41-50 age [

78]. The STEMI and N-STEMI mortality rate is different to the short term risk: the STEMI patients have 2 more higher risk of mortality comparing to the general population, and the NSTEMI have 2,5-2,8 much higher risk of mortality. [

5,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

79,

80,

81]

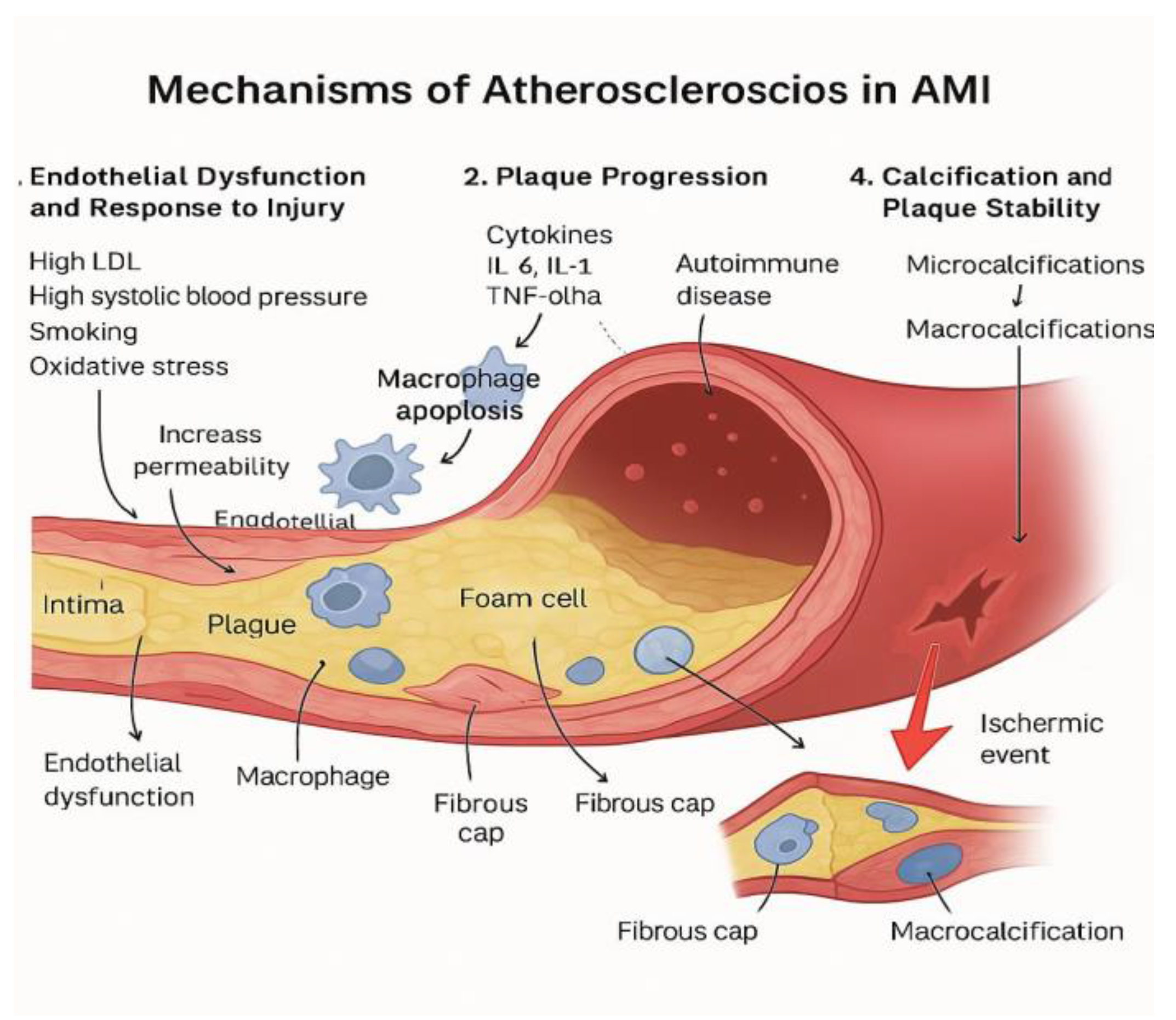

6.1. Atherothrombotic Pathways

Classical mechanism: The classic mechanism of atherosclerosis in AMI involves:

The endothelial dysfunctions and the response to the injury [

82]. The first factors who leads to this are represented by the high LDL, high systolic arterial blood pressure, smoking and the oxidative stress, this is leading to increase permeability of the endothelia from where the LDL particles enter in the intima of the artery, lead the process of oxidation and increase the inflammation. From that point, macrophage apoptosis contributes to increased inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.[

83].

Plaque progression: Chronic inflammation sustained by cytokines representing by IL 6, IL 1, TNF alpha, hs-CRP,promotes the growth and destabilization of plaque. Autoimmune diseases may contribute to this inflammatory process and accelerate plaque development in young individuals [

84,

85].

Intimal remodelation: The vascular smooth muscle cells respond to inflammation by proliferating and producing extracellular matrix leading to fibrous cap formation and also by transforming into foam cells contributing to plaque bulk and potentially necrotic formation [

86].

Calcification and plaque stability.: The instability plaque use to have microcalcifications comparing to stability plaque who have macrocalcification, and by that is more frequent the rupture of the unstable plaques and the promotion of a possible ischemic event [

87].

Figure 4.

Mechanism of Atherosclerosis in AMI.

Figure 4.

Mechanism of Atherosclerosis in AMI.

6.2. Non-Atherosclerotic Mechanism:

MINOCA is defined by AMI without >50% obstruction of the epicardial coronary artery and is a common cause of ischemic event, more often in young people, especially in young women. Is considerate a syndrome, not a single event because it includes: coronary plaque disruption and erosion, epicardial spasm, spontaneous coronary artery dissection(SCAD), microvascular dysfunction [

88]. Long term studies in young patients reveal 12% mortality over 7 years follow and a <30% reduction of the ventricular ejection fraction in young people who suffer from MINOCA [

89].

SCAD primarily affects young women, often without traditional risk factors (23-36% in women who suffer AMI). In SCAD the most come mechanism is represented by intimal tear who allowing the blood into the media and the rupture of the vasa vasorum causing intramural hematoma. This two events compressing the true lumen of the vessel and make a obstruction of the lumen. SCAD is associated with fibromuscular dysplasia (as pregnancy related vascular changes and connective tissues disorder, and emotional or physical stressors). The main treatment strategy is represented by conservative management (aspirin+beta-blockers), and the PCI strategy is reserved only for high risk patients [

90,

91,

92].

Vasospasm is a very frequent cause of MINOCA in young people, 20% of them have vasospasm. The main mechanism is represented by automatic overstimulation, endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and hyperreactivity of smooth muscle contractility. The main treatment strategy is represented by calcium channel blockers and nitroglycerin, avoid beta-blockers, and life style intervention [

93].

The microvascular dysfunction is cause by distal embolization of thrombus during PCI, ischemia-reperfusion injury who leads to endothelial swelling, pericyte contraction, glycocalyx shedding and capillary obstruction or microvascular inflammation and oxidative stress who leads to chronic dysfunction and remodeling. The main ways of diagnosis are represented by invasive index of microvascular resistance, hyperemic microvascular resistance and resistance reserve ration, and the non-invasive diagnosis ways are represented by PET imaging detect microvascular obstruction and quantify flow reserve. The main treatment strategy is represented by beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors/ARBs, statin, SGLT-2, colchicine. [

4,

93,

94]

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Young adults experiencing AMI represent a distinct and increasingly recognized clinical subgroup, in whom classical cardiovascular risk factors—such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia—often coexist with unconventional and age-specific contributors. Emerging literature from the past five years emphasizes the complex interplay between genetic predispositions (e.g., familial hypercholesterolemia, elevated lipoprotein(a)), psychosocial stressors (burnout, depression), recreational drug use, systemic inflammation, and autoimmune disease.

In contrast to older patients, young MI cases frequently lack obstructive coronary artery disease, with mechanisms like coronary vasospasm, spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD), microvascular dysfunction, and MINOCA (Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries) playing a central role. This etiologic diversity is matched by clinical heterogeneity—ranging from atypical symptomatology and delayed presentation to variable prognoses driven by microvascular injury and neurohormonal activation.

Diagnosis in young MI requires a high index of suspicion and often extends beyond conventional angiography, incorporating advanced imaging, intracoronary functional testing, and biomarker profiling. Management, too, must go beyond standard secondary prevention to address individualized needs—whether through calcium channel blockers for vasospasm, immunomodulatory therapy in autoimmune-mediated cases, or mental health support in stress-driven presentations.

Ultimately, MI in young adults is not simply a premature expression of an old disease; it is a multi-dimensional syndrome rooted in biology, behavior, and context. Future research and clinical strategies must adopt a more personalized, mechanism-oriented approach—one that integrates cardiovascular science with the evolving realities of a younger, more complex patient population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.C., M.T.L.P, S.I.C.; methodology, M.T.L.P.; resources, E.N.Ț, G.M., A.M.B, I.C.B and L.M. Ț.; writing—S.I.C, GM and O.I.; writing—review and editing, S.I.C. and E.N.Ț. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge was fully waived by the journal Medicina. The manuscript is submitted following the invitation from the Editorial Office (email dated 4 June 2025 to Prof. Istrătoaie Octavian).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. This study is a literature review and does not involve human participants or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study is a literature review and does not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

All data is available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| MI |

Myocardical infarction |

| CAD |

Coronary artery disease |

| MINOCA |

Myocardical infarction with non-obtrustive coronary arteries |

| CHD |

Coronary heart disease |

| AMI |

Acut myocardical infarction |

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| SID |

Systemic inflammation |

| RA |

Rheumatoid arthritis |

| CV |

Cardiovascular |

| SLE |

Systemic lupus eerythematosus |

| AS |

Ankylosing spondylitis |

| hsCRP |

High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

| MPO |

Myeloperoxidase |

| Lp-PLA2 |

Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 |

| TMAO |

Trimethylamine-N-oxide |

| LpA |

Lipoprotein A |

| SCAD |

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| TLA |

Three letter acronym |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

References

- Prakash, S.; Thomas, J.M.; Anantharaman, R. Clinical and Angiographic Profiles of Myocardial Infarction in a Young South Indian Population. Cureus 2024, 16, e63949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zheng, J.; Qian, F.; Zou, X.; Zou, S.; Wu, Z.; et al. Demographic and regional trends of acute myocardial infarction-related mortality among young adults in the US, 1999–2020. Npj Cardiovasc Heal 2025, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W.M.; Kelli, H.M.; Lisko, J.C.; Varghese, T.; Shen, J.; Sandesara, P.; et al. Socioeconomic Status and Cardiovascular Outcomes: Challenges and Interventions. Circulation 2018, 137, 2166–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaheen, M.; Pender, P.; Dang, Q.M.; Sinha, E.; Chong, J.J.H.; Chow, C.K.; et al. Myocardial Infarction in the Young: Aetiology, Emerging Risk Factors, and the Role of Novel Biomarkers. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, I.N. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Individuals: Demographic and Risk Factor Profile, Clinical Features, Angiographic Findings and In-Hospital Outcome. Cureus 2023, 15, e45803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parlati, A.L.M.; Nardi, E.; Sucato, V.; Madaudo, C.; Leo, G.; Rajah, T.; et al. ANOCA, INOCA, MINOCA: The New Frontier of Coronary Syndromes. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, R.B.S.; Pencina, M.J.; Massaro, J.M.; Coady, S. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Assessment: Insights from Framingham. Glob Heart 2013, 8, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnaswami, S.; Prasad, N.K.; Jacob Jose, V. A study of lipid levels in Indian patients with coronary arterial disease. Int J Cardiol 1989, 24, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, R.P.; Wang, Y.; Strait, K.M.; Lorenze, N.P.; D’Onofrio, G.; Bueno, H.; et al. Gender differences in the trajectory of recovery in health status among young patients with acute myocardial infarction: results from the variation in recovery: role of gender on outcomes of young AMI patients (VIRGO) study. Circulation 2015, 131, 1971–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, J.; Gill, A.; Mehran, R. Acute myocardial infarction in young women: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health 2018, 10, 267–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatnagar, P.; Wickramasinghe, K.; Wilkins, E.; Townsend, N. Trends in the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease in the UK. Heart 2016, 102, 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecoeur, E.; Domengé, O.; Fayol, A.; Jannot, A.-S.; Hulot, J.-S. Epidemiology of heart failure in young adults: a French nationwide cohort study. Eur Heart J 2023, 44, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.M.; Oncken, C.; Hatsukami, D. Women and Smoking: The Effect of Gender on the Epidemiology, Health Effects, and Cessation of Smoking. Curr Addict Reports 2014, 1, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleerup, H.B.; Dahm, C.C.; Thim, T.; Jensen, S.E.; Jensen, L.O.; Kristensen, S.D.; et al. Smoking is the dominating modifiable risk factor in younger patients with STEMI. Eur Hear Journal Acute Cardiovasc Care 2020, 9, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.Y.; Berman, A.N.; Biery, D.W.; Blankstein, R. Recent trends in acute myocardial infarction among the young. Curr Opin Cardiol 2020, 35, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotedar, S.; Garg, A.; Arora, A.; Chawla, S. Study of lipid profile in young patients (age 40 years or below) with acute coronary syndrome. J Fam Med Prim Care 2022, 11, 3034–3039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-B.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, H.; Hwang, I.-C.; Yoon, Y.E.; Park, H.E.; et al. Mildly Abnormal Lipid Levels, but Not High Lipid Variability, Are Associated With Increased Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Stroke in “Statin-Naive” Young Population A Nationwide Cohort Study. Circ Res 2020, 126, 824–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnesen, E.K.; Retterstøl, K. Secular trends in serum lipid profiles in young adults in Norway, 2001–2019. Atheroscler Plus 2022, 48, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, H.; Han, K.; Yoo, S.J.; Kim, M.K. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Level, Statin Use and Myocardial Infarction Risk in Young Adults. J Lipid Atheroscler 2022, 11, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, H.M.; Thorpe, C.T.; Bartels, C.M.; Schumacher, J.R.; Palta, M.; Pandhi, N.; et al. Undiagnosed hypertension among young adults with regular primary care use. J Hypertens 2014, 32, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antza, C.; Gallo, A.; Boutari, C.; Ershova, A.; Gurses, K.M.; Lewek, J.; et al. Prevention of cardiovascular disease in young adults: Focus on gender differences. A collaborative review from the EAS Young Fellows. Atherosclerosis 2023, 384, 117272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachma, P.; AzamMahalul Ainun, N.; Ika, F.; KanthaweePhitsanuruk Abdul, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hypertension among Young Adults: An Indonesian Basic Health Survey. Open Public Health J. [CrossRef]

- Moledina, S.M.; Shoaib, A.; Sun, L.Y.; Myint, P.K.; Kotronias, R.A.; Shah, B.N.; et al. Impact of the admitting ward on care quality and outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: insights from a national registry. Eur Hear Journal Qual Care Clin Outcomes 2022, 8, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biery, D.W.; Berman, A.N.; Singh, A.; Divakaran, S.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Collins, B.L.; et al. Association of Smoking Cessation and Survival Among Young Adults With Myocardial Infarction in the Partners YOUNG-MI Registry. JAMA Netw Open 2020, 3, e209649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stătescu, C.; Anghel, L.; Benchea, L.-C.; Tudurachi, B.-S.; Leonte, A.; Zăvoi, A.; et al. A Systematic Review on the Risk Modulators of Myocardial Infarction in the “Young”-Implications of Lipoprotein (a). Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikaiou, P.; Björck, L.; Adiels, M.; Lundberg, C.E.; Mandalenakis, Z.; Manhem, K.; et al. Obesity, overweight and risk for cardiovascular disease and mortality in young women. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2021, 28, 1351–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, W.; Liang, N. Blood glucose fluctuation and in-hospital mortality among patients with acute myocardial infarction: eICU collaborative research database. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0300323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.S.; Manocha, P.; Patel, J.; Patel, R.; Tankersley, W.E. Cannabis Use Is an Independent Predictor for Acute Myocardial Infarction Related Hospitalization in Younger Population. J Adolesc Heal Off Publ Soc Adolesc Med 2020, 66, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.T.; Park, T. Acute and Chronic Effects of Cocaine on Cardiovascular Health. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billman, G.E. Cocaine: a review of its toxic actions on cardiac function. Crit Rev Toxicol 1995, 25, 113–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaquen, B.S.; Cohen, V.; Eisenberg, M.J. Effects of cocaine on the coronary arteries. Am Heart J 2001, 142, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFilippis, E.M.; Singh, A.; Divakaran, S.; Gupta, A.; Collins, B.L.; Biery, D.; et al. Cocaine and Marijuana Use Among Young Adults With Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018, 71, 2540–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gresnigt, F.M.J.; Hulshof, M.; Franssen, E.J.F.; Vanhommerig, J.W.; de Lange, D.W.; Riezebos, R.K. Recreational drug use among young, hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome: A retrospective study. Toxicol Reports 2022, 9, 1993–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, B.; Biery, D.W.; Singh, A.; Divakaran, S.; Berman, A.N.; Wu, W.Y.; et al. Association of inflammatory disease and long-term outcomes among young adults with myocardial infarction: the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI Registry. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2022, 29, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houge, I.S.; Hoff, M.; Thomas, R.; Videm, V. Mortality is increased in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes compared to the general population – the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 3593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Yang, S.; Han, L.; Ba, X.; Shen, P.; Lin, W.; et al. Dyslipidemia in rheumatoid arthritis: the possible mechanisms. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1254753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meune, C.; Touzé, E.; Trinquart, L.; Allanore, Y. Abstract 1639: Trends in Cardiovascular Mortality in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis Over 50 years: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. Circulation 2009, 120, S536–S536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.W.; Liu, J.; Yang, D.M.; Xie, Y.; Peterson, E.D.; Navar, A.M.; et al. Incidence and Prevalence of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. JAMA Dermatology 2025, 161, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Lai, Y.-F.; Chien, W.-C.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chung, C.-H.; Chen, J.-T.; et al. Impact of Endophthalmitis on the Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Ankylosing Spondylitis Patients: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.C.; Lee, H.S.; Yang, J.; Park, M.-C. Cardiovascular risk according to biological agent exposure in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a nationwide population-based study. Clin Rheumatol 2025, 44, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGM; L WN, G. KJ, S. BJ. Cardiovascular Risk in Patients With Psoriasis. JACC 2021, 77, 1670–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaserico, S.; Papadavid, E.; Cecere, A.; Orlando, G.; Theodoropoulos, K.; Katsimbri, P.; et al. Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction in Asymptomatic Patients with Severe Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol 2023, 143, 1929–1936.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-L.; Fan, Y.-H.; Fan, K.-S.; Juan, C.-K.; Chen, Y.-J.; Wu, C.-Y. Cardiovascular disease risk in patients with psoriasis receiving biologics targeting TNF-α, IL-12/23, IL-17, and IL-23: A population-based retrospective cohort study. PLoS Med 2025, 22, e1004591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dzhus, M.; Mostbauer, H. Coronary artery lesions in Takayasu arteritis. Reumatologia 2023, 61, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiono, Y.; Takahata, M.; Ino, Y.; Tanimoto, T.; Kakimoto, N.; Suenaga, T.; et al. Pathological Alterations of Coronary Arteries Late After Kawasaki Disease: An Optical Coherence Tomography Study. JACC Adv 2024, 3, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgas, Y.; Mohammad, M.A.; Gisslander, K.; Rathmann, J.; Erlinge, D.; Jayne, D.; et al. Myocardial infarction in ANCA-associated vasculitis: a population-based cohort study. RMD Open. [CrossRef]

- Walter, D.J.; Bigham, G.E.; Lahti, S.; Haider, S.W. Shifting perspectives in coronary involvement of polyarteritis nodosa: case of 3-vessel occlusion treated with 4-vessel CABG and review of literature. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2024, 24, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.P.; Playford, M.P.; Frits, M.; Coblyn, J.S.; Iannaccone, C.; Weinblatt, M.E.; et al. The association between reduction in inflammation and changes in lipoprotein levels and HDL cholesterol efflux capacity in rheumatoid arthritis. J Am Heart Assoc 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țieranu, E.N.; Cureraru, S.I.; Târtea, G.C.; Vladuțu, V.-C.; Cojocaru, P.A.; Piorescu, M.T.L. , et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction and Diffuse Coronary Artery Disease in a Patient with Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Clin Med. [CrossRef]

- Alfaddagh, A.; Martin, S.S.; Leucker, T.M.; Michos, E.D.; Blaha, M.J.; Lowenstein, C.J.; et al. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Am J Prev Cardiol 2020, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosău, D.E.; Costache Enache, I.I.; Costache, A.D.; Tudorancea, I.; Ancuța, C.; Șerban, D.N.; et al. From Joints to the Heart: An Integrated Perspective on Systemic Inflammation. Life 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leib, A.D.; Foris, L.A.; Nguyen, T.; Khaddour, K. Dressler Syndrome., Treasure Island (FL): 2025.

- Bogsrud, M.P.; Øyri, L.K.L.; Halvorsen, S.; Atar, D.; Leren, T.P.; Holven, K.B. Prevalence of genetically verified familial hypercholesterolemia among young (<45 years) Norwegian patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. J Clin Lipidol 2020, 14, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmaghraby, K.M.; Abdel-Galeel, A.; Osman, A.H.; Hasan-Ali, H.; Abdelmegid, M.A.-K.F. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients with familial hypercholesterolemia presenting with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 27098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chávez-González, E.; Rodríguez-Jiménez, A.E.; Ferrer-Rodríguez, C.J.; Donoiu, I. Ventricular arrhythmias are associated with increased QT interval and QRS dispersion in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Rev Port Cardiol Orgao Of Da Soc Port Cardiol = Port J Cardiol an Off J Port Soc Cardiol 2022, 41, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, V.; Zirille, F.M.; Gill, E. Rethinking cardiovascular risk: The emerging role of lipoprotein(a) screening. Am J Prev Cardiol 2025, 21, 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, S.; Hernandez, S.; Rikhi, R.; Mirzai, S.; De Los Reyes, C.; McIntosh, S.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) as a Causal Risk Factor for Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2025, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buciu, I.C.; Tieranu, E.N.; Pircalabu, A.S.; Istratoaie, O.; Zlatian, O.M.; Cioboata, R.; et al. Exploring the Relationship Between Lipoprotein (a) Level and Myocardial Infarction Risk: An Observational Study. Medicina (Kaunas). [CrossRef]

- Bertolín-Boronat, C.; Marcos-Garcés, V.; Merenciano-González, H.; Martínez Mas, M.L.; Climent Alberola, J.I.; Perez, N.; et al. Familial Hypercholesterolemia Screening in a Cardiac Rehabilitation Program After Myocardial Infarction. Cardiogenetics 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faresjö, Å.; Karlsson, J.-E.; Segerberg, H.; Lebena, A.; Faresjö, T. Cardiovascular and psychosocial risks among patients below age 50 with acute myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2023, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, R.J.; Hao, Y.; Tan, E.W.Q.; Mok GJLe Sia, C.-H.; Ho, J.S.Y.; et al. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) After Acute Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2025;14. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Islam, F.; -Or-Rashid, M.H.; Mamun AAl Rahaman, M.S.; Islam, M.M.; et al. The Gut Microbiota (Microbiome) in Cardiovascular Disease and Its Therapeutic Regulation. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 903570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calborean, V.; Gheorman, V.; Istratoaie, O.; Mustafa, R.E.; Cojocaru, P.A.; Alexandru, D.O.; et al. QT interval analysis in patients with chronic liver disease. Rev Chim 2018, 69, 1134–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaar, B.J.H.; Prodan, A.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Muller, M. Gut Microbiota in Hypertension and Atherosclerosis: A Review. Nutrients. [CrossRef]

- Sessa, R.; Pietro MDi Filardo, S.; Turriziani, O. Infectious burden and atherosclerosis: A clinical issue. World J Clin Cases 2014, 2, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.; Thompson, R.C.; Trumble, B.C.; Wann, L.S.; Allam, A.H.; Beheim, B.; et al. Coronary atherosclerosis in indigenous South American Tsimane: a cross-sectional cohort study. Lancet (London, England) 2017, 389, 1730–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, S.; Chen, T.; Zhou, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xie, X.; et al. Distinct blood and oral microbiome profiles reveal altered microbial composition and functional pathways in myocardial infarction patients. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2025, 15, 1506382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, A.S.V.; Stelzle, D.; Lee, K.K.; Beck, E.J.; Alam, S.; Clifford, S.; et al. Global Burden of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation 2018, 138, 1100–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longenecker, C.T.; Sullivan, C.; Baker, J.V. Immune activation and cardiovascular disease in chronic HIV infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016, 11, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.S.; Bennett, S.; Holroyd, E.; Satchithananda, D.; Borovac, J.A.; Will, M.; et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndrome who present with atypical symptoms: a systematic review, pooled analysis and meta-analysis. Coron Artery Dis 2025, 36, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Singh, A.; Gadkari, C. Myocardial Infarction in Young Individuals: A Review Article. Cureus 2023, 15, e37102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.A.; Karim, H.M.R.; Panda, C.K.; Ahmed, G.; Nayak, S. Atypical Presentations of Myocardial Infarction: A Systematic Review of Case Reports. Cureus 2023, 15, e35492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peerwani, G.; Hanif, B.; Rahim, K.A.; Kashif, M.; Virani, S.S.; Sheikh, S. Presentation, management, and early outcomes of young acute coronary syndrome patients- analysis of 23,560 South Asian patients from 2012 to 2021. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2024, 24, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, A.; Mizobe, M.; Takahashi, J.; Funakoshi, H. Factors for delays in door-to-balloon time ≤ 90 min in an electrocardiogram triage system among patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a retrospective study. Int J Emerg Med 2023, 16, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, J.E.J.; Chaudhry, S.I.; Dreyer, R.P.; D’Onofrio, G.; Greene, E.J.; Hajduk, A.M.; et al. Sex Differences in Symptom Complexity and Door-to-Balloon Time in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am J Cardiol 2023, 197, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.J.; Feld, J.; Lange, S.A.; Günster, C.; Dröge, P.; Engelbertz, C.; et al. Impact of Guideline-Directed Drug Therapy after ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction on Outcome in Young Patients-Age and Sex-Specific Factors. J Clin Med. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Biery, D.W.; Singh, A.; Divakaran, S.; DeFilippis, E.M.; Wu, W.Y.; et al. Risk Factors and Outcomes of Very Young Adults Who Experience Myocardial Infarction: The Partners YOUNG-MI Registry. Am J Med 2020, 133, 605–612.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roston, T.M.; Aghanya, V.; Savu, A.; Fordyce, C.B.; Lawler, P.R.; Jentzer, J.; et al. Premature Acute Myocardial Infarction Treated With Invasive Revascularization: Comparing STEMI With NSTEMI in a Population-Based Study of Young Patients. Can J Cardiol 2024, 40, 2079–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan-Salvadores, P.; De La Torre Fonseca, L.M.; Calderon-Cruz, B.; Veiga, C.; Pintos-Rodríguez, S.; Fernandez Barbeira, S.; et al. Ischaemia-reperfusion time differences in ST-elevation myocardial infarction in very young patients: a cohort study. Open Hear. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.; Lan, N.S.R.; Phan, J.; Hng, C.; Matthews, A.; Rankin, J.M.; et al. Characteristics and Outcomes of Young Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Without Standard Modifiable Risk Factors. Am J Cardiol 2023, 202, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porapakkham, P.; Porapakkham, P.; Srimahachota, S.; Limpijankit, T.; Kiatchoosakun, S.; Chandavimol, M.; et al. The contemporary management and coronary angioplasty outcomes in young patients with ST-Elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) age < 40 years old: the insight from nationwide Thai PCI registry. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2024, 24, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaru-Zavaleanu, A.D.; Neacşu, A.I.; Cojocaru, A.; Osiac, E.; Gheonea, D.I. Heterogeneity in the Number of Astrocytes in the Central Nervous System after Peritonitis. Curr Heal Sci J 2021, 47, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitridge R, Thompson M, editors. No Title. Adelaide (AU):.

- Sterpetti, A.V. Inflammatory Cytokines and Atherosclerotic Plaque Progression. Therapeutic Implications. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2020, 22, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sircana, M.C.; Erre, G.L.; Castagna, F.; Manetti, R. Crosstalk between Inflammation and Atherosclerosis in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Is There a Common Basis? Life 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasouli-Drakou, V.; Ogurek, I.; Shaikh, T.; Ringor, M.; DiCaro, M.V.; Lei, K. Atherosclerosis: A Comprehensive Review of Molecular Factors and Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. [CrossRef]

- Ajoolabady, A.; Pratico, D.; Lin, L.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Bahijri, S.; Tuomilehto, J.; et al. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: pathophysiology and mechanisms. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţieranu, E.N.; Donoiu, I.; Istrătoaie, O.; Găman, A.E.; Ţieranu, M.L.; Ţieranu, C.G. , et al. Rare case of single coronary artery in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Rom J Morphol Embryol = Rev Roum Morphol Embryol 2017, 58, 1505–1508. [Google Scholar]

- Ipek, G.; Nural, A.; Cebeci, A.C.; Yucedag, F.F.; Bolca, O. Long-term outcomes in very young patients with myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries. Coron Artery Dis 2024, 35, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, M.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, R.; Zuo, P.; et al. Spontaneous left main coronary artery dissection occurred in a young male: a case report and review of literature. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2022, 22, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C.; Qadeer, Y.K.; Ang, S.P.; Wang, Z.; Alam, M.; Sharma, S.; et al. Incidence and in-hospital mortality among women with acute myocardial infarction with or without SCAD. Curr Probl Cardiol 2025, 50, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, P.-N.; Xu, C.; You, W.; Wu, Z.-M.; Xie, D.-J.; Zhang, H.; et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection as a Cause of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Female Population: A Single-center Study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017, 130, 1534–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Squires, I.; Khalil, S.; Patel, A.; Katukuri, N. MINOCA: Predictors and Future Management. Indian J Cardiovasc Dis Women n.d.;10. [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, A.; Zavaleanu, A.D.; Călina, D.C.; Gheonea, D.I.; Osiac, E.; Boboc, I.K.S.; et al. Different Age Related Neurological and Cardiac Effects of Verapamil on a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr Heal Sci J 2021, 47, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).