1. Introduction

The interplay between determinism, randomness, and free will has long fascinated both physicists and philosophers. In classical physics, determinism ruled, leaving no space for true unpredictability. In quantum mechanics, indeterminacy reemerges, yet the debate continues: is quantum randomness fundamental, or is it just epistemic?

Delayed-choice experiments, first envisioned by Wheeler [

1], test the counterintuitive nature of quantum measurement: a choice made after a particle’s detection can seemingly influence whether it exhibited wave-like or particle-like behavior. The delayed-choice quantum eraser (DCQE) variant [

2,

3] extends this framework by allowing the erasure or preservation of which-path information, with interference recovered or lost accordingly. It has challenged our intuition about causality, suggesting that measurement choices can seemingly retroactively determine whether or not interference patterns emerge.

In all implementations to date, the `choice’ of measurement basis has been made by beam splitters, or by quantum random number generators (QRNGs). Both are physical systems, governed by deterministic laws included in the quantum formalism. Thus, from a Bohmian or Everettian perspective, the universal wavefunction already encodes their future states.

A natural question arises: what if the choice mechanism is not reducible to physical determinism? If human free will exists in a strong sense—producing outcomes not predictable from prior physical states—then one could design an experiment to probe whether quantum predictions hold under such conditions.

Here, we propose a new variant of the DCQE experiment, in which the measurement choice is delegated to humans making spontaneous decisions within a short reaction window. If human free will exists in a form that escapes deterministic or quantum-mechanical prediction, then interference outcomes could differ from those obtained with physical random generators.

2. Related Work

A large-scale project known as the BIG Bell Test [

4] involved volunteers worldwide who provided random inputs to Bell inequality experiments via their keystrokes. While this addressed the “freedom-of-choice loophole” in nonlocality tests, the human inputs only replaced QRNGs in the selection of measurement bases for entangled particles. Our proposal differs fundamentally: it employs the

delayed-choice quantum eraser architecture, where the measurement setting must be chosen

after the signal photon has already been detected, and where quantum memory is required to extend the decision time window. To our knowledge, no experiment has yet tested whether genuinely human choices in this context yield results indistinguishable from quantum-random choices.

3. Proposed Experimental Setup

3.1. Overview

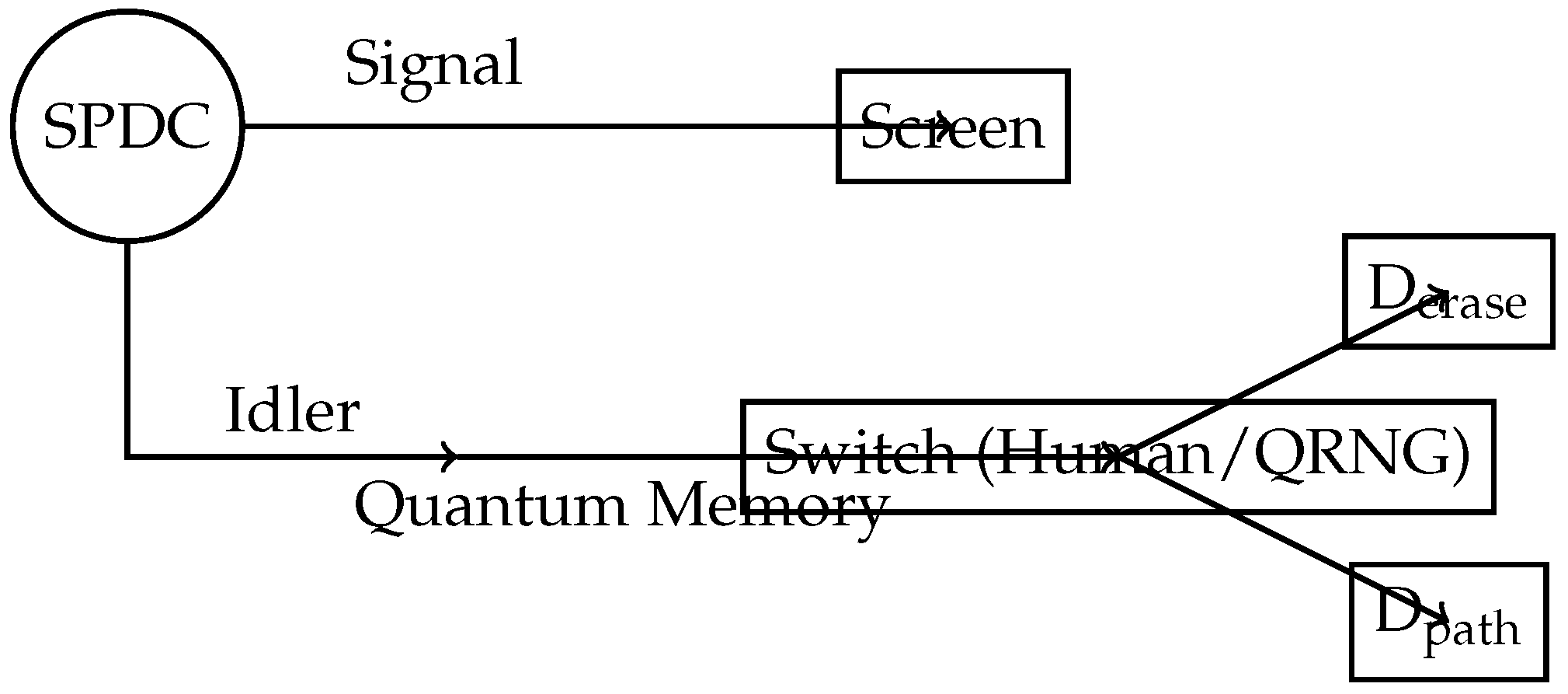

Our setup is based on the canonical delayed-choice quantum eraser [

3]. A signal photon is directed toward a detector screen

after passing through a double-slit-like apparatus. Its idler twin photon is delayed and directed to a set of detectors that either erase or reveal which-path information.

In our variant, the decision of whether the idler photon encounters a “which-path revealing” or a “which-path erasing” configuration is determined not by a QRNG but by human participants.

3.2. Human Decision Protocol

Participants are seated in front of a touchscreen interface. When the decision window opens, the screen displays four options (A, B, C, D). The participant must quickly and spontaneously select one option. Two options correspond to orienting a mirror (or optical switch) toward a path-erasing configuration; the other two correspond to a path-revealing configuration.

To minimize bias:

Participants are not told beforehand the meaning of the options.

The mapping between touchscreen options and measurement settings is randomized across runs.

Instructions emphasize spontaneity and discourage premeditation.

Communication between participants is forbidden to avoid shared strategies.

A large number of participants (e.g. 1000) ensures statistical significance. A parallel control experiment is performed using QRNGs for comparison.

3.3. Timing Constraints and Quantum Memory

The central challenge is ensuring that the signal photon hits the detection screen before the human choice is made, preserving the delayed-choice condition. To achieve this, we propose using quantum memories to store the idler photon for several seconds.

State-of-the-art quantum memories [

5,

6] can achieve storage times approaching the second scale. Extending memory duration to 4–5 seconds would be ideal to match human reaction times. Research into atomic ensemble memories and rare-earth-ion doped crystals provides a promising path.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the proposed delayed-choice setup with human decision.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the proposed delayed-choice setup with human decision.

To rigorously test whether human choices can play a causal role beyond deterministic or quantum-random dynamics, the timing of the events must satisfy the following inequality:

where:

: timestamp of the detection of the signal photon on .

: moment when the options (A, B, C, D) are displayed on the participant’s touchscreen.

: objective timestamp of the onset of the human decision (defined, for example, via EEG/EMG onset markers, or the timestamp of the touchscreen press).

: timestamp of the arrival of the idler photon at the measurement stage (after quantum memory storage and fast switching by Pockels cells).

The enforcement of this inequality chain is crucial: it ensures that no hidden correlation or “pre-programming” of the experimental apparatus could mimic a human-specific effect. Any deviation of the statistics under these conditions would point to a genuine role of human freedom in the outcome of a quantum experiment.

3.4. Bias Control

Potential biases include:

Participants deciding in advance: minimized by surprise timing, i.e., participants do not know in advance the structure and meaning of the choices displayed on the touchscreen.

Communication between participants: avoided by isolation and secrecy of task structure.

Data analysis bias: avoided by blind post-processing, where analysts do not know which runs correspond to human vs QRNG choices until after interference visibility is computed.

4. Expected Results

Two possibilities exist:

Quantum mechanics holds: Human choices yield results indistinguishable from QRNG-based choices. Interference appears only when which-path information is erased.

Violation in favor of free will: Human choices systematically produce interference patterns even in cases where, according to standard QM, no interference should appear. This would suggest that human decisions were not encoded in the prior universal wave function.

5. Discussion

If successful, the experiment would probe whether human free will manifests in physics in a manner irreducible to quantum randomness. A violation of quantum mechanics would have huge consequences beyond physics, impacting neuroscience and philosophy. Even if no violation is observed, the experiment would represent the first rigorous attempt to operationalize free will in quantum foundations.

References

- J.A. Wheeler, “The `past’ and the `delayed-choice double-slit experiment’,” in Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Theory, edited by A.R. Marlow, Academic Press (1978).

- M. O. Scully and K. Drühl, “Quantum eraser: A proposed photon correlation experiment concerning observation and delayed choice in quantum mechanics,” Phys. Rev. A, 25, 2208 (1982).

- Y.-H. Kim, R. Y.-H. Kim, R. Yu, S. P. Kulik, Y. Shih, and M. O. Scully, “Delayed choice quantum eraser,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 84, 1 (2000).

- The BIG Bell Test Collaboration, “Challenging local realism with human choices,” Nature, 557, 212–216 (2018).

- S.-J. Yang et al., “Highly retrievable spin-wave–photon entanglement source,” Phys. Rev. Lett., 117, 123601 (2016).

- T. Zhong et al., “Nanophotonic rare-earth quantum memory with optically controlled retrieval,” Science, 357, 1392–1395 (2017).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).