1. Introduction

Food waste is one of the most contemporary problems of our time, and it has social, ethical, and environmental repercussions. Combined with the issues of climate change and food insecurity that we inevitably experience, it is among the priorities of the European Union countries [

1] and the United Nations [

2,

3]. Every year, 1.3 billion tons of food intended for human consumption are thrown away, reaching approximately 33% of global food production. In this waste, we should also include the significant environmental impacts accompanying these foods’ processing since their production processes are highly resource-intensive and the losses are substantial [

4]. The most critical environmental impacts are greenhouse gas emissions, water and air pollution, and deforestation, observed at all food processing stages. Food waste and food loss (FLW) occur throughout the food value chain until final consumption and are two concepts that are differentiated [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Food waste (FW) results from food losses at the last stage of the value chain when the food is in the hands of the consumer, while food loss (FL) occurs at all stages of the value chain before reaching households. These stages incorporate agricultural production, transportation, product processing, and storage and distribution [

11].

FW is inextricably linked to the social profile of consumers and their habits. More important than these are their economic profile, their knowledge of food management issues, their preferences, and how much they are aware of the environment [

12,

13]. The intense urbanization that we have experienced in recent years has resulted in decentralization and population growth in cities. This phenomenon, combined with the increase in household incomes, inevitably leads to increased purchases of goods. The increase in the consumption of goods also includes the increase in the purchase of more food as a necessity. As a result, households produce more waste, which naturally provides food.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization, 61% of food losses are wasted by households, which is estimated to reach approximately 79 kg of food per consumer [

12,

13,

14]. Food waste also increases losses in water and other energy resources as an integral part of their production and processing. So, we immediately understand the benefits of reducing overall food losses, which will reduce per capita greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions at all supply chain stages. It is worth mentioning that the consequences of reducing food waste will also have benefits on the issue of climate change [

15]. According to research, total food losses contribute to 8% of greenhouse gas emissions and occupy 30% of global agricultural land, which receives all the cultivation care. Still, in the end, these products end up in the trash [

16].

One of the most important issues in reducing FLW is the achievement of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals, as the sustainability of our planet is threatened [

17,

18]. Knowing all the impacts that the issue of FW has on resource management as well as on important sustainability issues, all 193 UN members have included in their agenda with an implementation plan in 2030 the “Responsible Production and Consumption” in the context of achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 [

19,

20]. The realization of this goal requires planning and discipline in sustainable agricultural production processes and the implementation of circular economy methods [

21], as well as urging governments to reconsider all processes of the value chain of products from cultivation to distribution to reduce food losses by half by 2030 [

22]. A consequence of the above is the obligation of UN member states to commit to implementing what is required for sustainable rural development and sustainable utilization of all food losses [

23,

24].

In this article, we shed light on the factors that contribute to the behavior of consumers, who are the final managers of the most considerable quantities of food wasted. The research approach concerns consumer perceptions of food management, organization, consumer behavior, environmental knowledge, and impacts. The consumer profile is essential, with its economic and social aspects being more critical. Our main goal is to highlight the main factors that influence consumer behaviors on the issue of food waste and, through these factors, propose action plans to reduce food waste. The innovation and differentiation of this specific work in the region of Central Macedonia is the study of a new factor of this "sense of community" and its relationship with consumer behavior.

Considering the above, this research will study consumers’ perceptions of food waste. The remainder of the paper includes the theoretical background in the next section, whereas the materials and methods employed are presented in the third section. The fourth section discusses the result, and the final section concludes.

2. Theoretical Background

In recent years, numerous studies have focused on identifying factors and finding solutions to the issue of food waste, highlighting households as one of the most essential links in the food supply chain [

25,

26]. The most recent studies are those that highlight more practical issues in food management from the household perspective, such as the correct planning of the quantities to be processed, as well as more complex issues, such as proper storage and preservation practices [

27,

28]. However, several studies have approached the issue from the perspective of policies and government guidelines within their commitments to sustainable rural development goals. These approaches highlight essential topics such as educational campaigns as important tools for reducing food waste, how to indicate product expiration dates, and how the consumer is aware of and able to understand it [

29].

However, few studies have focused on environmental issues and the burden of food waste on the environment, such as greenhouse gas emissions and the depletion of available resources [

30]. The emergence of educational campaigns as an important factor in reducing food waste was also highlighted by Principato et al. [

31]. Educational campaigns proposing proper food management techniques to consumers as a solution for reducing food waste are of strategic importance. Also, Carmo Stangherlin and Barcellos [

32], studying the factors of reducing food waste, concluded that proper information and awareness of consumers is also the responsibility of the food industry and commercial stores. Both should contribute to informing the correct way of food management, which is also one of the main factors in minimizing food waste. Another modern approach is social media campaigns through which consumers can learn how to store food properly, plan meals better, and use leftovers. Finally, campaigns that promote the donation of unused food can help direct the use of surplus food to people in need [

33].

Consumer behavior seems to be the most prevalent and plays a decisive role in households’ food waste. Numerous studies have analyzed several of these factors by dividing households into individual groups and patterns, the most common of which are based on their purchasing attitude, their perception, and their educational level [

6,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Although food waste and its correlation with consumer behavior during times of crisis have been little studied, this is being negated in the COVID-19 period in which there are numerous studies [

23,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. In conclusion, the research carried out during the pandemic crisis on the issue of food waste reached common conclusions regarding consumer behaviors in different countries and cultures [

49,

50,

51,

52]. The most important of these is the shift of households to healthier foods, avoiding processed foods with preservatives and additives, strengthening the domestic market, thus strengthening the local economy, and strengthening e-commerce since it was consumers’ most preferred shopping channel [

53]. These specific conclusions are also confirmed by studies in Italy and Spain, highlighting the Internet as one of the most important ways to buy food [

23,

54]. A characteristic of all these studies is the highlighting of consumers’ need to reduce food waste through proper management, planning, organization, and awareness of the households themselves [

55,

56,

57,

58]. In conclusion, food waste is a multidimensional phenomenon influenced by environmental, social and psychological factors. The theory of planned behavior [

59] argues that attitudes, social norms and perceived control largely predict behavior. Knowledge of environmental issues and in particular food waste enhances environmental sensitivity and promotes responsible consumption [

60]. A sense of community positively influences social responsibility, while emotions, such as guilt and moral obligation, guide consumer choices [

61]. At the same time, sociodemographic factors such as income and marital status are related to consumption patterns and the ability to manage resources. The above theoretical assumptions provide the basis for developing hypotheses regarding household behavior towards food waste.

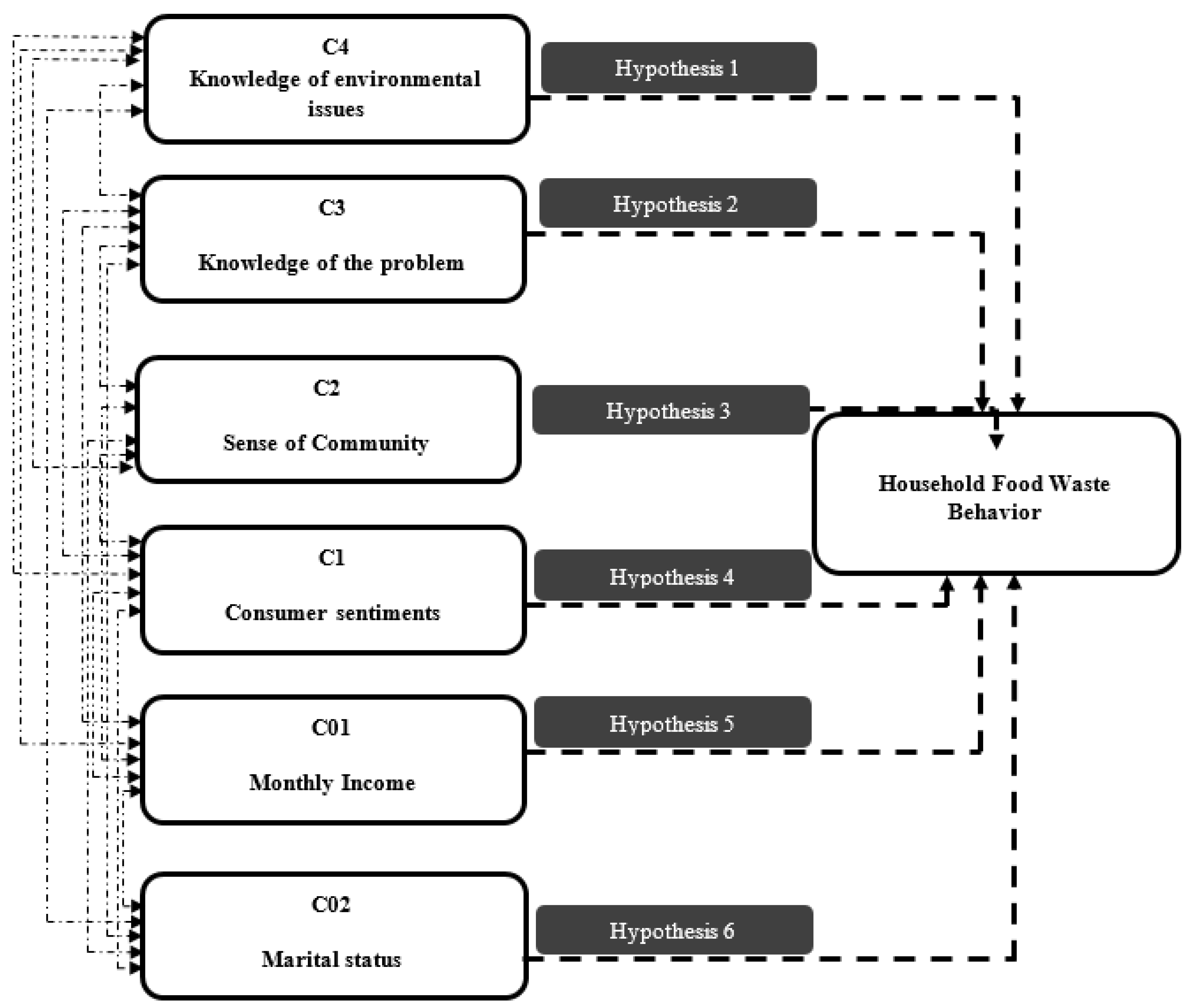

Based on the above, in this study, we will examine the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. There is a positive significant relationship between knowledge of environmental issues and household behavior on the issue of food waste.

Hypothesis 2. There is a significant positive relationship between knowledge of this specific issue and household behavior regarding food waste.

Hypothesis 3. There is a positive significant relationship between Sense of Community and household behavior on the issue of food waste.

Hypothesis 4. There is a significant positive relationship between consumer sentiments and household behavior on the issue of food waste.

Hypothesis 5. There is a positive significant relationship between monthly income and household behavior on the issue of food waste.

Hypothesis 6. There is a significant positive relationship between marital status and household behavior regarding the issue of food waste.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the conceptual framework.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling Procedure

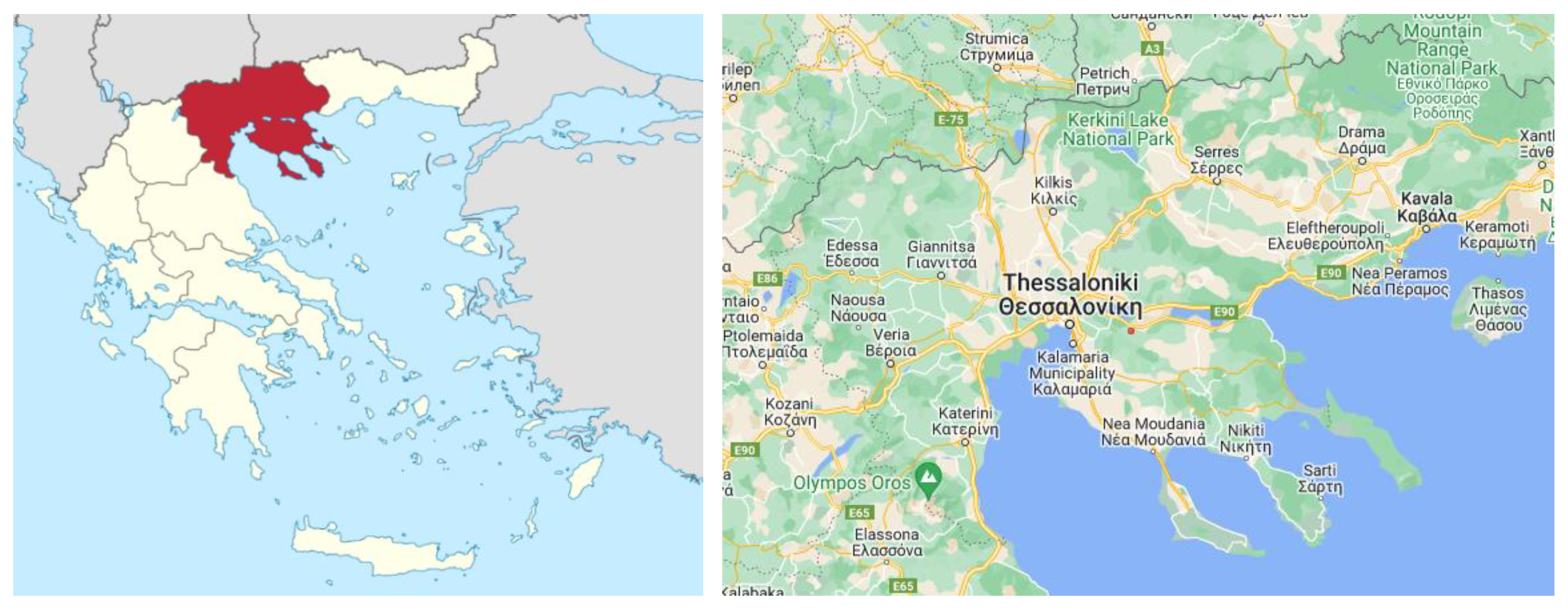

For this specific research, an electronic questionnaire was used to capture how consumers perceive the issues related to food waste in households. The specific data were also the primary data of the research conducted from January to August 2024. The sampling frame consisted of 1,795,670 people in Central Macedonia.

The Region of Central Macedonia is the largest in area (19,162 km²) and the second most populous region in Greece. It has well-developed industries, including the food, chemical, and mechanical equipment sectors, and is one of the strongest economic regions in the country. It also has the second largest number of households (735,829) and a higher number of households with more than two members than Attica. Additionally, it is the region with the largest number of households actively employed in the primary sector across all Greek regions [

62].Central Macedonia is unique in having simultaneous intense industrial, agricultural, and tourist development. It boasts the largest urban center outside of Attica and occupies a strategic position as a bridge between Greece and the Balkans. The Region of Central Macedonia is one of Greece’s most dynamic and multifaceted economic and cultural hubs. According to available data, it significantly contributes to the national GDP, ranking second after Attica. The region’s economy is diversified, with strong sectors in industry, services, and agriculture. Central Macedonia represents 17% of Greece’s economically active population. The share of the economically active population among those aged 15 and over was 51% in 2015 and 49% in 2020, reflecting a slight decrease in labor force participation. Overall, Central Macedonia presents a dynamic economy with diverse sectors contributing to its development. The minimum sample size required for a given population was determined according to the following formula:

where S is the minimum sample size to investigate, N is the total population size, e is the margin of error, z is how confident you can be that the population would choose an answer within a specific range, and p is the standard deviation (in this case 0.5%). The sampling method was simple random, and the final sample of the research consisted of 954 people.

Table 1 captures the demographics of the sample.

Figure 2.

Topographic map of the study area [

63].

Figure 2.

Topographic map of the study area [

63].

Each member of the population in random sampling has an equal chance of being selected in the sample in a survey. Simple random sampling occurs when placing the entire population in order 1 and 2, which is possible, and then 10–15% are selected by a random number process. Simple random sampling is commonly applied with telephone polls, where the population is physically sorted alphabetically in the telephone directory.

Initially, a landline directory frame was used as a sampling frame, i.e. we selected residential landline telephone directories as the basis for sampling. The records were grouped into pages based on sample size and a random subset of the records was selected from these. The selected contacts were then approached via telephone call, with the aim of collecting the participants’ email addresses. These addresses were used to send the questionnaire in electronic format. The questionnaire was sent after telephone communication and informing everyone in the sample. According to the research design, after the first sending of the questionnaire to all the individuals in the sample, a first telephone reminder of the research objectives followed a month later, and a second sending of the questionnaire was done. After completing all communications, 870 questionnaires were returned, of which 668 were considered valid, with a response rate of 70%. The rest of the questionnaires were not included because data was missing.

3.2. Methodology

According to the existing literature on household food waste as well as issues of recycling, reuse, and waste reduction were the questions that supported the research [

41,

42,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68]. Seven key questions were used to explore the factors contributing to household food waste behavior and employed a five-point Likert scale ranging from "very important" to "not at all important."

The adverse effects of food waste were assessed through four questions and a five-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly agree" to "strongly disagree" respondents expressed their views on environmental, economic, social, and environmental impacts. Their feelings towards society were measured through four questions. Using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ’’strongly agree’’ to ’’strongly disagree,’’ respondents rated their perception of whether people from their work, neighborhood, city, and country. Four questions were asked about the perception of knowledge of the research issue, and using a five-point Likert scale ranging from "very strong" to "not at all strong," respondents recorded their perception of food waste and pollution, the environment, resources, and landfills. Environmental knowledge was assessed through a five-point Likert scale ranging from "very important" to "not at all important," where respondents recorded their understanding of recycling, the environment, and environmental symbols. Three questions were included to assess food waste reduction using a five-point Likert scale ranging from "very unimportant" to "very important." The reuse of food waste was evaluated through five questions. Using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree,” respondents rated their perception of food waste. Finally, respondents’ perception of recycling was captured through four questions using a five-point Likert scale ranging from ’very unimportant’ to ’very important.’

The construct validity of the questionnaire was assessed by factor analysis (factor analysis) to extract the factors into principal components (principal component analysis) and the axis rotation method, varimax rotation. The resulting factors included (C1 Consumer sentiments, C2 Sense of Community, C3 Knowledge of the problem, C4 Knowledge of environmental issues, C5 Reduce, C6 Reuse, C7 Recycle, C01 Monthly Income, C02 Marital status. The standardized factor loadings and the reliability of the explanatory factors are presented in

Table 2.

The specific factors were later used in a path analysis model according to the original conceptual framework (

Figure 1), according to which the use of SPSS Amos 25 software also produced the path coefficients. Path analysis was chosen to examine and analyze the complexity of the relationships between independent factors, including direct and indirect effects. It will also allow us to incorporate any interactions between independent variables, allowing for the estimation of both direct and indirect effects, and the graphical representation of the model will help us better understand its structure. Estimation of the path model resulted in the following equation:

where bn (n = 1, 2, 3) are the partial standardized regression coefficients, and e is the measurement error. According to the results of the path analysis, the overall effects of the factors that contribute to household food waste behavior are:

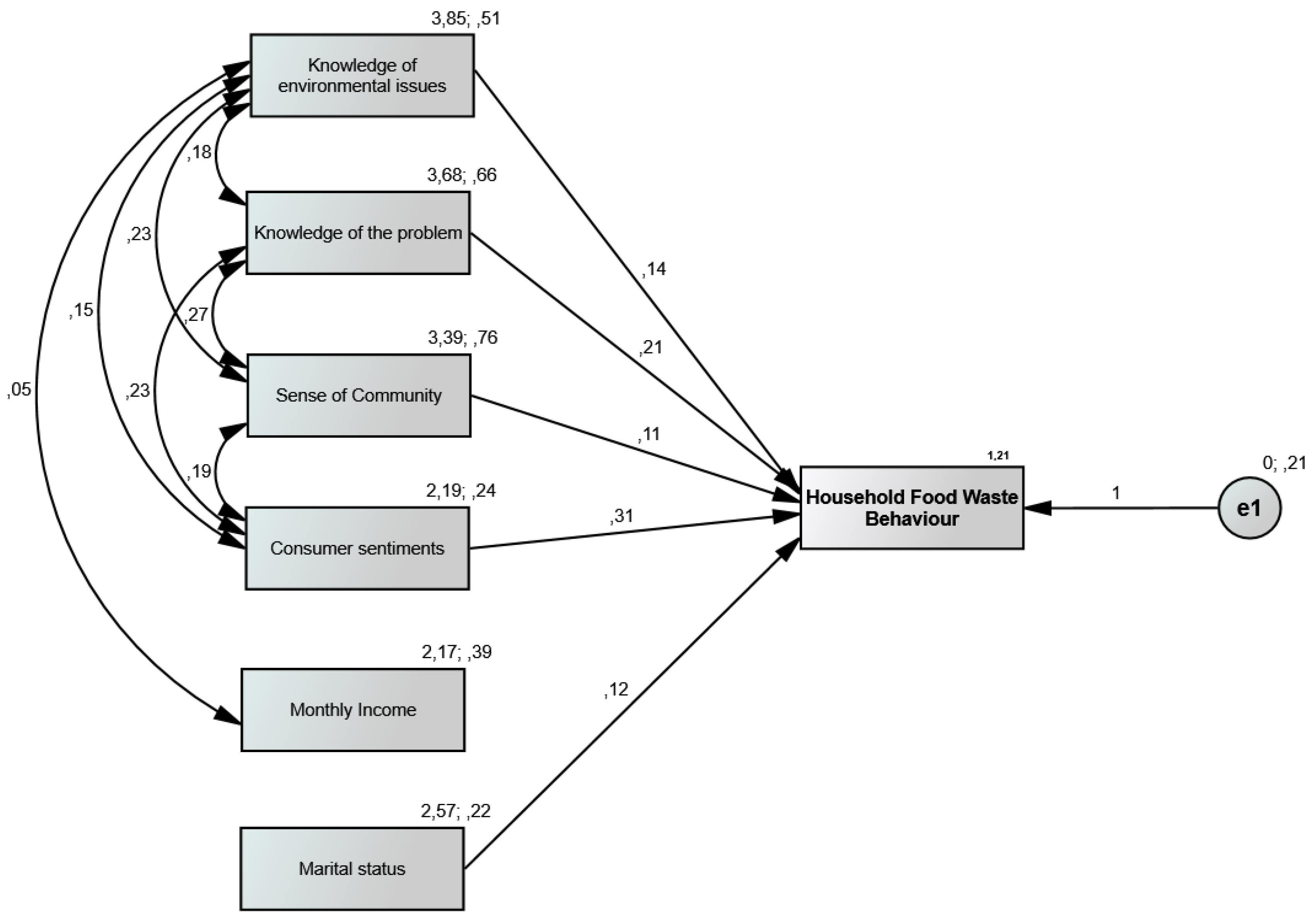

The value of the coefficient of determination R2 was 0.396, and all the results are depicted in

Table 2 and

Figure 3, showing all factor correlations with each other. The correlation matrix of all factors was created to explore the relationships between the extracted factors and each other and the main objective of the research.

The correlation table in

Table 3 helped the researchers to rule out some scenarios in the later stage of path analysis and to have an overall picture of the interactions between them. Also, the factors that show statistically significant values give a first estimate of their possible correlation with the behavior of households in food waste. The interactions of the factors and their contribution to household food waste behavior as an achievable goal are presented in the research model, estimated by the path analysis method below.

Existing literature demonstrates that household food waste is influenced by consumer behavior—a theme that is explanatoryly amplified through the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [

69]. Developed by Icek Ajzen [

70], TPB is a widely used sociopsychological framework that serves to analyze the critical factors that determine food waste behaviors and supports the design of effective strategies to reduce food waste [

71]. Many studies have examined the demographic and socioeconomic factors that influence food waste and waste reduction strategies [

72]. For all these reasons, this research assumes particular importance, as it aims to study complex forms of household food waste through various demographic and socioeconomic contexts.

4. Results and Discussion

The literature review on the issue of food waste in households and consumer behavior led them to identify six research hypotheses, which were examined for the calculation of the consumer behavior model. The model calculation results and the standardized path coefficient confirmed the five hypotheses, while one was rejected. Also, the correlation coefficient of the dependent variable (R2) was satisfactory, indicating an acceptable rate of explanation of the factors.

Considering the results of the model, the factor Knowledge of environmental issues (C4, β: 0.140, p < 0.01) contributes significantly to the behavior of households on the issue of food waste (hypothesis 1 is confirmed). Diaz-Ruiz et al. [

73] investigated a sample of 418 individuals in Barcelona and found an indirect relationship between consumers’ environmental concerns and minimizing food waste. Specifically, consumers who said they were more concerned about the environment showed that they wasted less food. Knowledge of the problem on the part of households seems to be positively related (C3, β: 0.21, p < 0.01) to their behavior on the issue of food waste (hypothesis 2 confirmed). Regarding the factor sense of community, there is a positive correlation (C2, β: 0.11, p < 0.01) with consumer behavior on the issue of food waste (hypothesis 3 confirmed). The factor Consumer Sentiments helps positively (C1, β: 0.31, p < 0.01) to household behavior and food waste (hypothesis 4 confirmed).

The monthly income does not appear to be a significant factor influencing consumer behavior and food waste (Hypothesis 5 is not confirmed), which contradicts other research findings that highlight the importance of economic profile in food waste [

74,

75,

76]. It should be stressed that consumer habits are primarily influenced by education and culture. Some households may be better able to manage the supply and consumption of food regardless of income due to better education or experience. Also, information about healthy eating, proper storage, and appropriate use of food may have a more significant impact than income. Households that are educated on how to reduce food waste may be less prone to waste. In addition, the tendency for households to buy more food to be "safe" may be a common phenomenon, regardless of income. In short, it can be said that while a household’s income may influence its ability to purchase food, other social, cultural, and psychological factors are also determinants of food consumption and wasting behavior. Finally, Marital Status appears to be one of the factors that have a positive correlation (C02, β: 0.12, p < 0.01) with household behavior on the issue of food waste (Hypothesis 6 is confirmed).

In contrast, Grasso et al. [

77], in their study involving 1,518 Danish and 1,511 Spanish consumers, examined the associations between marital status and household size and found no association with food waste. It should be emphasized that the variables related to consumer knowledge regarding waste recycling issues, purchasing packaging that contributes to waste reduction, and the knowledge and interpretation of environmental symbols on packaging are the ones that significantly influence household behavior on food waste, a fact confirmed by many studies [

68,

78,

79]. Also, the correct information of consumers on the issue of household waste and that its reduction leads to improving pollution, creating a better environment for future generations, and reducing the unnecessary use of landfills are among the most critical variables of the knowledge of the problem (C3) factor as highlighted by the literature [

80,

81,

82].

It is worth emphasizing that consumers feel closer to them as members of the same community as people in their neighborhood and their cities, while they feel guilty when they waste food because this act of theirs has negative impacts on the environment, the economy, and society. These emotions are the most critical in the Consumer Sentiments (C1) factor that influences household behavior; similar emotions have been recorded in other studies [

35,

51,

83,

84,

85]. In many societies, traditions, and habits around meals such as holidays, family gatherings, and local events can lead to excess food, as often more food is offered than is consumed. Also, in some cultures, food is considered sacred or has symbolic value, which can encourage proper use and an emphasis on reducing waste. Conversely, in other cultures, there may be less emphasis on food management, resulting in more waste. In addition, cultural values influence policy decisions about food management and strategies to reduce waste. Societies that emphasize sustainability may develop programs to reduce waste. Finally, one of the most critical variables that influence household behavior on the issue of food waste seems to be the number of family members and the number of children. This fact is also confirmed by Boz et al. [

86].

For the final adjustment of the model, some general criteria were used, such as non-significant X2 (at least p > 0.05, maybe even p > 0.10 or p > 0.20) and the SRMR and RMSEA indices. The result of the model estimation was satisfactory, as shown by the indices NFI = 0.99, IFI = 0.995, CFI = 0.98, and RMSEA=0.06. In addition, the analysis and mapping of the final model revealed interesting bidirectional relationships between the main factors. Knowledge of environmental issues (C4) has a direct bidirectional positive correlation with the remaining factors, except marital status. These specific correlations confirm that the correct information and, ultimately, the knowledge that consumers acquire positively affect how they feel about other members of the community and the guilt they have when they discard food. Additionally, there was a positive relationship between the knowledge of the problem factor (C4) and consumer sentiments (C1), highlighting that education and proper information positively impact the negative emotions and feelings of guilt of consumers when they throw away food.

Finally, the positive relationship found between monthly income (C01) and knowledge about environmental issues (C4) can be explained by the fact that households with higher incomes usually have access to educational opportunities and more complete information on critical environmental issues — such as climate change and sustainability. These are often the households that can invest in "green" technologies (e.g., solar water heaters, electric vehicles), as they have greater financial resources. In contrast, households with lower incomes may have neither access to relevant education nor the financial capacity to adopt such solutions. Furthermore, a financially constrained household often faces pressing needs — such as food and shelter — and focuses on them, resulting in a decrease in its active participation in environmental actions [

87,

88,

89]. Furthermore, evidence from Greek studies shows that both income and education level are positively related to the formation of environmental awareness and “nutrition” information (nutrition literacy). In the national context, people with higher income and better educational training show greater environmental literacy and are more willing to invest in environmentally friendly choices. According to the relevant report of the European Commission [

90] in Greece, concepts of sustainability and environmental awareness are integrated already in education — from preschool to higher education, with the aim of forming active and environmentally aware citizens.

Food production has a significant environmental impact and contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, while growing food consumes resources such as water and land. Government policies should focus on sustainability and environmental protection, thereby reducing waste. Also, money that could be invested in other sectors of the economy is wasted on food production, transport, and disposal. Policies should aim to reduce this waste to improve the economy. In addition, policies can include legislative initiatives aimed at reducing waste. This includes incentives for companies and consumers and regulations to redistribute food that will not be sold. Finally, policies focusing on public education and food waste awareness can help reduce waste individually and collectively.

5. Conclusions

This research aimed to highlight the factors that contribute to household attitudes on the issue of food waste in a large central region in Northern Greece to initiate actions through educational programs, information, and policies to reduce food waste. The results highlight Consumer Sentiments (C1) and Knowledge of the problem (C4) as the most critical factors regarding household attitudes. The study’s results exhibited five of the six initial research hypotheses confirming overall evidence from the literature on food waste. However, this research highlighted correlations between factors, most notably the relationship between education and consumers’ guilt, offering new perspectives and valuable evidence for future research. Consumers’ household behavior on the issue of food waste is multifaceted and complex as it shows correlations with many different factors, highlighting the difficulty in finding a direct solution. In this context, the factors involved are Knowledge of environmental issues, Knowledge of the problem, Consumer Sentiments, Sense of community, and Marital Status; in the full development of the factors, however, we should also highlight knowledge of food waste recycling, knowledge of purchasing packaging that reduces waste, knowledge about environmental symbols, Number of household members and Number of children in the family. It is a fact that the factors related to knowledge underline the gap that exists with educational programs.

Author Contributions

Z.P., investigation and CR.K. supervision.

Funding

This research received no external funding and the APC was not externally funded.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data is associated with this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- EU Commission. Roadmap to a resource efficient Europe. COM, 2011, 571.

- FAO. Food wastage footprint: Impacts on natural resources. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2013.

- FAO. Food wastage footprint full-cost accounting. Food Wastage Footprint. 2014.

- Gustavsson, J.; Cederberg, C.; Sonesson, U.; von Otterdijk, R.; Meybeck, A. Global food losses and food waste – Extent, causes and prevention. Food and Agriculture Organization, 2024.

- Teigiserova, D. A.; Hamelin, L.; Thomsen, M. Towards transparent valorization of food surplus, waste and loss: Clarifying definitions, food waste hierarchy, and role in the circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 136033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Mattia, G.; Di Leo, A.; Pratesi, C. A. The household wasteful behaviour framework: A systematic review of consumer food waste. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Rios, C.; Hofmann, A.; Mackenzie, N. Sustainability-oriented innovations in food waste management technology. Sustainability 2020, 13, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chaudhary, A.; Mathys, A. Nutritional and environmental losses embedded in global food waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 160, 104912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelakis, C.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Keramopoulou, C.; Theodossiou, G. Green Growth, Green Development and Climate Change Perceptions: Evidence from a Greek Region. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklavos, G.; Theodossiou, G.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Karelakis, C.; Ragazou, K. Environmental, Social, and Governance-Based Artificial Intelligence Governance: Digitalizing Firms’ Leadership and Human Resources Management. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noleppa, S.; Cartsburg, M. Das grosse Wegschmeissen: vom Acker bis zum Verbraucher: Ausmaß und Umwel teffekte der Lebensmittelverschwendung in Deutschland. WWF Deutschland, 2015.

- Schmidt, K. Explaining and promoting household food waste-prevention by an environmental psychological based intervention study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 111, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemare, M. F.; Çakir, M.; Peterson, H. H.; Novak, L.; Rudi, J. On the measurement of food waste. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koester, U.; Loy, J. P.; Ren, Y. Measurement and reduction of food loss and waste: Reconsidered. Agricultural Economics, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champions 12.3. Guidance on Interpreting Sustainable Development Goal Target 12.3. [Internet document]. Accessed 20 September 2022. https://champions123.org/sites/default/files/202009/champions-12-3-guidance-on-interpreting-sdg-target-12-3.pdf.

- FAO STAT. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome, 2018. http://faostat.fao.org.

- Principato, L.; Ruini, L.; Guidi, M.; Secondi, L. Adopting the circular economy approach on food loss and waste: The case of Italian pasta production. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 144, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklavos, G.; Theodossiou, G.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Karelakis, C.; Lazarides, T. Reinforcing sustainability and efficiency for agrifood firms: A theoretical framework. In Sustainability Through Green HRM and Performance Integration, pp. 101–120; IGI Global, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, L.; Bruggemann, R. The 17 United Nations’ sustainable development goals: A status by 2020. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2022, 29, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo Stangherlin, I.; de Barcellos, M. D.; Basso, K. The impact of social norms on suboptimal food consumption: A solution for food waste. J. Int. Food Agribusiness Mark. 2020, 32, 30–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsangas, M.; Gavriel, I.; Doula, M.; Xeni, F.; Zorpas, A. A. Life cycle analysis in the framework of agricultural strategic development planning in the Balkan region. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardra, S.; Barua, M. K. Halving food waste generation by 2030: The challenges and strategies of monitoring UN sustainable development goal target 12.3. J. Cleaner Prod. 2022, 380, 135042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, M.; Cui, H. D. Using food loss reduction to reach food security and environmental objectives – A search for promising leverage points. Food Policy 2021, 98, 101915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, C.; Alboni, F.; Falasconi, L. Quantities, determinants, and awareness of households’ food waste in Italy: A comparison between diary and questionnaires quantities. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leverenz, D.; Moussawel, S.; Maurer, C.; Hafner, G.; Schneider, F.; Schmidt, T.; Kranert, M. Quantifying the prevention potential of avoidable food waste in households using a self-reporting approach. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, S.; Grappi, S.; Bagozzi, R. P.; Barone, A. M. Domestic food practices: A study of food management behaviors and the role of food preparation planning in reducing waste. Appetite 2018, 121, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Holsteijn, F.; Kemna, R. Minimizing food waste by improving storage conditions in household refrigeration. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 128, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakos, D.; Szabó-Bódi, B.; Kasza, G. Consumer awareness campaign to reduce household food waste based on structural equation behavior modeling in Hungary. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 24580–24589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Massow, M.; Parizeau, K.; Gallant, M.; Wickson, M.; Haines, J.; Ma, D. W.; … Duncan, A. M. Valuing the multiple impacts of household food waste. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principato, L.; Secondi, L.; Pratesi, C. A. Reducing food waste: an investigation on the behaviour of Italian youths. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangherlin, I. D. C.; De Barcellos, M. D. Drivers and barriers to food waste reduction. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2364–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, J. A.; Alaybek, B.; Hartman, R.; Mika, G.; Leib, E. M. B.; Plekenpol, R.; … Sprenger, A. Initial assessment of the efficacy of food recovery policies in US States for increasing food donations and reducing waste. Waste Manag. 2024, 176, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, S. The effect of consumer perception on food waste behavior of urban households in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Rather, M. I.; Zargar, U. R. Understanding the food waste behavior in university students: An application of the theory of planned behaviour. J. Cleaner Prod. 2024, 437, 140632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, P.; Zacharatos, T.; Boukouvala, V. Consumer behaviour and household food waste in Greece. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 965–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etim, E.; Choedron, K. T.; Ajai, O.; Duke, O.; Jijingi, H. E. Systematic review of factors influencing household food waste behaviour: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 43(6), 803-827. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Bremer, P.; Jowett, T.; Lee, M.; Parker, K. S.; Gaugler, E. C.; Mirosa, M. What influences consumer food waste behaviour when ordering food online? An application of the extended theory of planned behaviour. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2330728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falasconi, L.; Cicatiello, C.; Franco, S.; Segrè, A.; Setti, M.; Vittuari, M. Such a shame! A study on self-perception of household food waste. Sustainability 2019, 11, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikovskaja, V.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. Food waste avoidance actions in food retailing: The case of Denmark. J. Int. Food Agribusiness Mark. 2017, 29, 328–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Nilashi, M.; Tseng, M. L.; Senali, M. G.; Abbasi, G. A. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behaviour: A systematic review. Appetite 2022, 176, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, G.; Cerroni, S.; Nayga Jr, R. M.; Yang, W. Impact of Covid-19 on household food waste: the case of Italy. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 585090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, E. A. D. M.; Freitas, M. G. M. T. D.; Demo, G. Food waste in restaurants: evidence from Brazil and the United States. J. Int. Food Agribusiness Mark. 2023, 35, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Javadi, F.; Hiramatsu, M. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behavior in Japan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baya Chatti, C.; Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H. Closing the Loop: Exploring Food Waste Management in the Near East and North Africa (NENA) Region during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Qi, D. How to reduce household food waste during and after the COVID-19 lockdown? Evidence from a structural model. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardekani, Z. F.; Sobhani, S. M. J.; Barbosa, M. W.; Amiri-Ardekani, E.; Dehghani, S.; Sasani, N.; De Steur, H. Determinants of household food waste behavior during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: an integrated model. Environ. Dev. Sustain. [CrossRef]

- Bashar, A.; Nyagadza, B.; Ligaraba, N.; Maziriri, E. T. The influence of Covid-19 on consumer behaviour: a bibliometric review analysis and text mining. Arab Gulf J. Sci. Res. 2024, 42, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatab, A. A.; Tirkaso, W. T.; Tadesse, E.; Lagerkvist, C. J. An extended integrative model of behavioural prediction for examining households’ food waste behaviour in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annunziata, A.; Agovino, M.; Ferraro, A.; Mariani, A. Household food waste: a case study in Southern Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Roe, B. E. Segmenting US consumers by food waste attitudes and behaviors: Opportunities for targeting reduction interventions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 45, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, L.; Fiszman, S.; Puerta, P.; Chaya, C.; Tárrega, A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities. Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelakis, C.; Papanikolaou, Z.; Theodosiou, G.; Goylas, A. Local Products Dynamics and the Determinants of Purchasing Behaviour. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2021, 16, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, B. E.; Bender, K.; Qi, D. The impact of COVID-19 on consumer food waste. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Voronova, V.; Kloga, M.; Paço, A.; Minhas, A.; Salvia, A. L.;... Sivapalan, S. COVID-19 and waste production in households: A trend analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 777, 145997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cequea, M. M.; Vásquez Neyra, J. M.; Schmitt, V. G. H.; Ferasso, M. Household food consumption and wastage during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak: A comparison between Peru and Brazil. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Prabhakar, G.; Duong, L. N. Usage of online food delivery in food waste generation in China during the crisis of COVID-19. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 58, 5602–5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. How household food shopping behaviors changed during COVID-19 lockdown period: Evidence from Beijing, China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naskar, S. T.; Lindahl, J. M. M. Forty years of the theory of planned behavior: a bibliometric analysis (1985–2024). Manag. Rev. Q. 2025, pp. 1–60. [CrossRef]

- Stancu, V.; Haugaard, P.; Lähteenmäki, L. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 2016, 96, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, K. C.; Gillis, H. L.; Kivlighan Jr, D. M. Process factors explaining psycho-social outcomes in adventure therapy. Psychotherapy 2017, 54, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority, Good Practice Advisory Committee. First Annual Report. 2023. http://www.statistics.gr.

- World Easy Guides. Available online: World Easy Guides. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/d/viewer?mid=1gwzsBXQFIkjFXK2_ZPUUoZGyHhE&hl=en&ll=39.54969270722924%2C21.76136687578175&z=13 (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Boulet, M.; Hoek, A. C.; Raven, R. Towards a multi-level household food waste and consumer behaviour framework: Untangling spaghetti soup. Appetite 2021, 156, 104856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withanage, S. V.; Dias, G. M.; Habib, K. Review of household food waste quantification methods: Focus on composition analysis. J. Cleaner Prod. 2021, 279, 123722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L. E.; Liu, G.; Cheng, S. Rural household food waste characteristics and driving factors in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. A.; Landry, C. E. Household food waste and inefficiencies in food production. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 103, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Bhadain, M.; Baboo, S. Household food waste: attitudes, barriers and motivations. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 2016–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehman, J. M.; Babbitt, C. W.; Flynn, C. What predicts and prevents source separation of household food waste? An application of the theory of planned behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L. L.; Guan, W. J.; Duan, C. Y.; Zhang, N. F.; Lei, C. L.; Hu, Y.; … Zhong, N. S. Effect of recombinant human granulocyte colony–stimulating factor for patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and lymphopenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fami, H. S.; Aramyan, L. H.; Sijtsema, S. J.; Alambaigi, A. Determinants of household food waste behavior in Tehran city: A structural model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 143, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Ruiz, R.; Costa-Font, M.; Gil, J. M. Moving ahead from food-related behaviours: an alternative approach to understand household food waste generation. J. Cleaner Prod. 2018, 172, 1140–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setti, M.; Falasconi, L.; Segrè, A.; Cusano, I.; Vittuari, M. Italian consumers’ income and food waste behavior. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 1731–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranchi, M.; Calabrò, G.; De Pascale, A.; Fazio, A.; Giannetto, C. Household food waste and eating behavior: empirical survey. Br. Food J. 2016, 118, 3059–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Talia, E.; Simeone, M.; Scarpato, D. Consumer behaviour types in household food waste. J. Cleaner Prod. 2019, 214, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A. C.; Olthof, M. R.; Boevé, A. J.; van Dooren, C.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Brouwer, I. A. Socio-demographic predictors of food waste behavior in Denmark and Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T. T.; Malek, L.; Umberger, W. J.; O’Connor, P. J. Household food waste disposal behaviour is driven by perceived personal benefits, recycling habits and ability to compost. J. Cleaner Prod. 2022, 379, 134636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, H.; Shaw, P. J.; Richards, B.; Clegg, Z.; Smith, D. What nudge techniques work for food waste behaviour change at the consumer level? A systematic review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, J.; Mataraarachchi, S. A review of landfills, waste and the nearly forgotten nexus with climate change. Environments 2021, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohini, C.; Geetha, P. S.; Vijayalakshmi, R.; Mini, M. L.; Pasupathi, E. Global effects of food waste. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2020, 9, 690–699. [Google Scholar]

- Vijay, V.; Kinsland, A.; Shah, T. CellMore: Reducing Food Waste and Landfills while Increasing Plastic Alternatives.2024.

- Daly, A. N.; Kearney, J. M.; O’Sullivan, E. J. The underlying role of food guilt in adolescent food choice: A potential conceptual model for adolescent food choice negotiations under circumstances of conscious internal conflict. Appetite 2024, 192, 107094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal-e-Hasan, S. M.; Mortimer, G.; Ahmadi, H.; Abid, M.; Farooque, O.; Amrollahi, A. How tourists’ negative and positive emotions motivate their intentions to reduce food waste. J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 2039–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, D.; Yap, C. C.; Wu, S. L.; Berezina, E.; Aroua, M. K.; Gew, L. T. A systematic review of country-specific drivers and barriers to household food waste reduction and prevention. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boz, Z.; Kiker, G.; Haase, H.; Orr, R.; Vignesh, A.; Campbell, C.; … Clemen, T. Modeling Waste: An Agent-Based Model to Support the Measurement of Household Food Waste. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T. Space to waste: the influence of income and retail choice on household food consumption and food waste in Indonesia. Int. Plan. Stud. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Jaenicke, E. C. Estimating food waste as household production inefficiency. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 102, 525–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J. L.; Ellison, B. Economics of household food waste. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 68, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaousi, G.; Stasinaki, S.; Melidoniotis, E.; Zavras, D.; Niakas, D. Socioeconomic inequalities in relation to health and nutrition literacy in Greece. Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2019, 3, e221–e229. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).