1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, oestrogen-dependent inflammatory disorder characterised by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity. It affects approximately 10% of women of reproductive age worldwide, with prevalence estimates ranging from 7% to 15% depending on population and diagnostic criteria[

1,

2,

3]. This condition impacts more than 190 million individuals globally and is associated with substantial impairment in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) across physical, psychological, sexual, and occupational domains[

1,

4,

5]. A multicentre study conducted across ten countries involving 1,418 women reported an average diagnostic delay of 6.7 years, with affected individuals losing an average of 10.8 hours of work per week due to symptoms and experiencing significantly reduced physical functioning compared to controls[

4]. Another cross-sectional analysis of women with laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis found an average weekly loss of 7.4 hours of productivity and reported that presenteeism and pain-related impairment reached levels as high as 65%[

5]. A recent umbrella review of systematic reviews further confirmed the strong association between endometriosis and multiple dimensions of psychological distress, including depression, anxiety, and deteriorated interpersonal relationships[

6]. Furthermore, endometriosis frequently coexists with adenomyosis, a condition with overlapping symptoms and hormonal sensitivities, which further complicates the clinical management of associated pain and represents a target for the same hormonal suppression strategies.

The pathophysiology of endometriosis-associated pain involves a complex hormonal-inflammatory axis characterized by local estradiol excess due to aberrant aromatase expression and deficient 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (17β-HSD2) activity, combined with progesterone resistance mediated by selective downregulation of the PR-B isoform. These alterations promote chronic inflammation, neuroangiogenesis, and nociceptive sensitization[

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. These mechanisms provide the biological rationale for hormonal suppression therapy and are discussed in detail in

Section 2.

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues suppress ovarian oestradiol synthesis via hypothalamic-pituitary axis inhibition, while progestins such as dienogest and gestrinone exert both central and local effects, including antagonism of oestrogenic activity and modulation of progesterone resistance[

8]. Although mechanistically distinct, these therapeutic classes share a unified objective: disruption of the oestrogen-driven inflammatory environment that sustains the pathophysiology of endometriosis.

The aim of the present review is to critically compare the three main hormonal strategies in endometriosis, not only in terms of analgesic efficacy but, crucially, with respect to their safety profiles and tolerability. In light of mounting evidence suggesting therapeutic equivalence in efficacy, the decision-making process has shifted towards a more individualised approach, prioritising side-effect profiles and patient preferences as core determinants of clinical success.

2. Pathophysiology of Endometriosis-Associated Pain

Pain in endometriosis arises from a complex interplay of endocrine, immunological, and neurological mechanisms within the lesion microenvironment. At its core, the disease exhibits a pathological hormonal profile characterised by local oestrogen dominance and progesterone resistance. These features promote chronic inflammation and neuroangiogenesis, which together sustain a state of pelvic hyperalgesia.

Endometriotic lesions develop endocrine autonomy through aberrant expression of aromatase, which allows ectopic cells to convert androgenic precursors into oestradiol locally. In parallel, the downregulation of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (17β-HSD2) limits estradiol inactivation, resulting in supraphysiological concentrations of bioactive oestrogens in the lesion microenvironment[

12,

13]. This local oestrogen excess drives the proliferation and survival of ectopic endometrial tissue and exacerbates inflammation through the induction of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) synthesis. In turn, PGE2 further stimulates aromatase expression, establishing a self-perpetuating cycle of inflammation and hormone production[

4].

Progesterone resistance constitutes a second critical element of this pathophysiological cascade. This phenomenon is attributed to the selective loss of progesterone receptor isoform B (PR-B), which impairs decidualisation and disrupts the anti-inflammatory actions of progesterone[

14]. The failure to respond to progesterone leads to persistent activation of inflammatory pathways, including the upregulation of cytokines and chemokines that promote tissue damage and nociceptor sensitisation.

A particularly important consequence of this hormonal-inflammatory dysregulation is the induction of neuroangiogenesis. Oestrogens and inflammatory cytokines stimulate the expression of neurotrophic factors, notably nerve growth factor (NGF), which promotes both the sprouting of sensory nerve fibres and the formation of new blood vessels within endometriotic lesions[

5,

15,

16]. This neural remodelling contributes to peripheral and central sensitisation, and has been closely linked to the severity of pain symptoms in affected individuals.

Collectively, these mechanisms form the basis for hormonal suppression as the primary medical strategy in the management of endometriosis. Therapeutic interventions targeting ovarian oestrogen production or counteracting the effects of oestrogen on endometriotic lesions have demonstrated substantial clinical benefit. The three main hormonal approaches, GnRH analogues, dienogest, and gestrinone, share the common goal of disrupting this endocrine-inflammatory feedback loop, though they do so through distinct pharmacodynamic mechanisms. A comparative evaluation of these therapies must therefore go beyond efficacy and consider their differing impacts on hormonal balance, inflammation, neuroangiogenesis, and ultimately pain modulation.

3. Materials and Methods

This narrative review was conducted with the objective of critically synthesising the current evidence on the clinical efficacy, tolerability, and safety profiles of the three principal hormonal strategies used in the treatment of endometriosis-associated pain: dienogest, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogues, and gestrinone. To ensure methodological transparency and clarity of clinical reasoning, this review followed the core principles outlined in the SANRA (Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles) guidelines.

A comprehensive literature search was performed in June 2025 across the MEDLINE/PubMed, Scopus and Embase databases. Distinct search strategies were developed for each therapeutic class, combining Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) with free-text keywords. For dienogest, the terms included Endometriosis, Dienogest, Progestins, “Pelvic Pain”, and “Hormonal Therapy”. In the case of GnRH analogues, the search encompassed terms such as “Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone”, “GnRH Agonists”, “GnRH Antagonists”, “Leuprolide”, “Elagolix”, and “Medical Management”. For gestrinone, given the relative scarcity of indexed clinical trials, the strategy prioritised high-quality systematic reviews and meta-analyses using terms like “Gestrinone”, “Hormonal Treatment”, and “Therapeutic Efficacy”. Additional primary studies on gestrinone were retrieved through backward citation tracking from pre-selected systematic reviews.

Studies were considered eligible if they included women of reproductive age with clinically or surgically confirmed endometriosis, assessed one of the three hormonal treatments as monotherapy, and reported outcomes relevant to pain relief, adverse effects, bone mineral density, or metabolic safety. Articles were excluded if they focused on infertility or assisted reproductive technologies, if they were not published in English, or if they consisted of preclinical models, narrative commentaries without systematic methodology, or studies lacking outcomes pertinent to tolerability or long-term safety.

These studies were selected based on their methodological quality and relevance to the review's core themes of efficacy, tolerability, and safety, with a preference for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and large randomized controlled trials where available. These comprised randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, prospective and retrospective observational studies, and pharmacovigilance reports. For each study, data were extracted regarding drug class, treatment duration, clinical endpoints, efficacy findings, adverse event profiles, and impact on bone or metabolic parameters. The data were then organised by therapeutic class to enable structured comparison and to highlight differences in tolerability that may influence real-world adherence and patient satisfaction.

Although no quantitative synthesis was performed, emphasis was placed on the clinical applicability of each finding and its implications for shared decision-making in contemporary gynecological endocrinology. The decision to adopt a structured narrative format, rather than a systematic review model, reflects the objective of integrating diverse forms of high-quality evidence into a cohesive, clinically meaningful framework for treatment individualisation.

4. Comparative Analysis of Hormonal Therapies

4.1. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH) Analogues

GnRH analogues constitute one of the most established and potent classes of pharmacological therapy for the management of moderate to severe endometriosis-associated pain. Their mechanism of action relies on suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, thereby inducing a reversible state of chemical menopause. GnRH agonists, such as leuprolide and goserelin, act by initially stimulating and then downregulating pituitary GnRH receptors (resulting in the characteristic flare-up phenomenon), whereas oral GnRH antagonists, such as elagolix and relugolix, provide immediate, dose-dependent suppression of gonadotropin secretion without an initial stimulatory phase[

9].

The efficacy of GnRH analogues is well established. In a pivotal double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, leuprolide acetate significantly reduced dysmenorrhoea and non-menstrual pelvic pain over a six-month treatment period[

8]. The introduction of oral antagonists further strengthened this evidence base. Phase III trials, such as Elaris EM-I and EM-II, demonstrated that elagolix significantly reduced both menstrual and non-menstrual pelvic pain in a dose-dependent manner compared to placebo[

17]. A recent network meta-analysis positioned leuprolide among the most effective pharmacological interventions for endometriosis-related pain[

18,

19].

Despite their robust efficacy, the profound hypoestrogenism induced by GnRH analogues is associated with a notable adverse effect profile, which constitutes the principal limitation of their long-term use and a major consideration in shared decision-making. Common side effects include vasomotor symptoms (e.g., hot flushes), vaginal dryness, mood changes, and loss of bone mineral density (BMD). Clinical studies have shown that monotherapy with leuprolide can lead to more than 6% loss of lumbar spine BMD within six months[

20]. When compared directly with dienogest in randomised trials, GnRH analogues exhibited comparable analgesic efficacy but were associated with a significantly higher incidence of hot flushes and a measurable decrease in BMD, whereas dienogest maintained BMD neutrality[

21].

To mitigate these adverse effects and extend the duration of treatment, the strategy of “add-back therapy” has been developed. This approach is based on the “estrogen threshold hypothesis,” which posits that concomitant administration of low-dose oestrogens and progestins can maintain estradiol levels within a therapeutic window, high enough to protect bone and alleviate vasomotor symptoms, yet low enough to avoid reactivation of endometriotic lesions[

22]. Seminal studies have demonstrated that add-back therapy prevents BMD loss and relieves hypoestrogenic symptoms without compromising the analgesic efficacy of GnRH analogues[

16]. This concept has been incorporated into modern oral combination regimens. In the SPIRIT 1 and 2 trials, relugolix combined with estradiol and norethindrone acetate in a once-daily oral formulation significantly reduced pain while preserving bone density over a 12-month treatment period[

23].

GnRH analogues offer a highly effective pharmacological option for pain management in endometriosis. However, their use requires careful counselling regarding the adverse effects associated with hypoestrogenism. For extended treatment durations, add-back therapy is strongly recommended to ensure safety and tolerability.

4.2. Dienogest

Dienogest is a synthetic oral progestin derived from 19-nortestosterone, developed specifically for the treatment of endometriosis and currently considered a first-line therapy in many international guidelines. Its mechanism of action is multifactorial: it exerts a strong progestogenic effect on the endometrium, resulting in decidualisation and subsequent atrophy of ectopic endometrial tissue. In addition, dienogest has local anti-inflammatory, antiangiogenic, and antiproliferative properties[

24]. Unlike GnRH analogues, it induces only moderate ovarian suppression and does not cause profound hypoestrogenism[

25].

The efficacy of dienogest at a daily dose of 2 mg has been well demonstrated in multiple randomised controlled trials (RCTs). In pivotal studies, it was shown to be significantly superior to placebo in reducing endometriosis-associated pelvic pain (EAPP), with clinically relevant improvements in pain scores observed at both 12 and 24 weeks of treatment[

25,

26].

A key argument supporting the clinical positioning of dienogest derives from head-to-head comparisons. A multicentre non-inferiority RCT directly compared dienogest with leuprolide acetate (a GnRH analogue) over a 24-week period. The study concluded that dienogest was non-inferior to leuprolide in reducing pain, with nearly identical reductions in Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores at the end of treatment (−47.5 mm for dienogest versus −46.0 mm for leuprolide)[

21]. This finding of equivalent analgesic efficacy was subsequently corroborated by network meta-analyses, which ranked dienogest at the same efficacy level as GnRH analogues for the treatment of endometriosis-related pain[

19].

The principal advantage of dienogest, and a central theme in shared decision-making, lies in its distinct tolerability profile. Because it does not induce severe hypoestrogenism, dienogest is not associated with bone mineral density (BMD) loss. The same RCT that demonstrated efficacy equivalence also found that while the leuprolide group experienced a significant decrease in BMD, the dienogest group maintained stable bone density, positioning it as a safe option for long-term use without the need for add-back therapy[

22]. Moreover, the incidence of vasomotor symptoms such as hot flushes is markedly lower when compared to GnRH analogues.

Nevertheless, dienogest presents its own set of tolerability challenges, particularly in relation to bleeding pattern disturbances, mood alterations, and weight gain. Irregular bleeding, spotting, and amenorrhoea are among the most commonly reported adverse events and are frequent causes of treatment discontinuation[

27]. Other progestogenic side effects such as headache, breast tenderness, depressed mood, and acne may occur, although generally with lower intensity[

26].

A notable concern is the psychiatric safety profile of dienogest, especially the potential for depressive symptoms. Clinical studies indicate that up to 5% of women using dienogest may experience mood changes, typically mild to moderate in intensity[

28]. However, more severe cases have also been reported, including major depressive disorder with suicidal ideation in patients without prior psychiatric history[

29]. A large prospective pharmacovigilance study (VIPOS) reported a modest but measurable increase in the risk of depression among dienogest users, with an adjusted hazard ratio of up to 1.8 compared to other hormonal therapies for endometriosis[

30]. Mechanistically, these mood-related effects may be mediated by changes in neurosteroid levels, particularly allopregnanolone, and its action on GABA-A receptors in limbic structures such as the hypothalamus and amygdala[

31,

32].

In light of these findings, it is advisable to conduct psychiatric screening prior to initiating treatment and to closely monitor mood symptoms, especially during the initial months of therapy.

Dienogest thus represents a therapeutic option with analgesic efficacy comparable to potent GnRH analogues, while offering the crucial benefit of preserving bone mineral density and avoiding severe vasomotor symptoms. Its use should involve a frank discussion with the patient regarding the acceptability of bleeding pattern disturbances as the principal adverse effect to be anticipated and managed.

4.3. Gestrinone

Gestrinone is a synthetic steroid derived from 19-nortestosterone, pharmacologically classified as an antiprogestogen with antiestrogenic and moderate androgenic activity, due to its affinity for progesterone, androgen, and estrogen receptors[

32]. Its mechanism of action in endometriosis is multifaceted: it suppresses pituitary gonadotropin release, resulting in anovulation and a hypoestrogenic state[

33], while simultaneously exerting a direct atrophic effect on ectopic endometrial tissue[

34]. This pharmacological profile positions gestrinone as a high-potency hormonal treatment.

The analgesic efficacy of gestrinone is robust and well documented. A recent network meta-analysis concluded that, for the management of non-menstrual pelvic pain, gestrinone was the most effective intervention among all pharmacological treatments evaluated[

19]. High-quality evidence supporting the central argument of this review comes from a multicentre, randomised, double-blind trial that directly compared gestrinone with leuprolide acetate (a GnRH analogue). The study demonstrated that gestrinone was equally effective in reducing pelvic pain, with no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups[

35]. The clinical efficacy of gestrinone has also been recognised in Cochrane systematic reviews, which list it as a valid therapeutic alternative, albeit with a distinct side-effect profile[

19].

A key consideration in therapeutic decision-making with gestrinone is its unique safety profile. Most importantly, its use has not been associated with serious adverse outcomes. A comprehensive systematic review including 32 clinical trials found no reports of major cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction or stroke, nor any mortality related to treatment[

31]. Furthermore, in contrast to GnRH analogues, multiple studies have shown that gestrinone does not induce bone mineral density loss; in some cases, a slight increase or maintenance of BMD was observed during treatment[

35,

36].

The most frequently reported adverse effects of gestrinone are androgenic. Guidelines from the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE), as well as Cochrane reviews and analyses by Fagundes et al., consistently identify seborrhoea, acne, and hirsutism as the most common treatment-related events. These effects are dose-dependent, as shown in trials that compared varying gestrinone regimens. While often categorized as dermatological, these manifestations can significantly impact a patient's quality of life and self-esteem, representing a critical potential barrier to treatment adherence. It is therefore important to note that individual susceptibility plays a significant role, making a personalised risk-benefit discussion essential in clinical decision-making.

Amenorrhoea, often induced by gestrinone, should not be regarded as an adverse effect in this context but rather as a therapeutic objective, since menstrual suppression is directly associated with relief from cyclic dysmenorrhoea[

31].

Gestrinone emerges as a therapeutically valid option with analgesic efficacy comparable, and in the case of non-menstrual pain, potentially superior, to that of other leading therapies. Its favourable cardiovascular and skeletal safety profiles further enhance its clinical appeal. However, the primary limitation, which heavily influences its acceptability for many patients, lies in its androgenic effects. These manifestations, while dose-dependent and influenced by individual sensitivity, can be highly distressing and must be positioned as a central topic of an open dialogue with the patient during therapeutic planning.

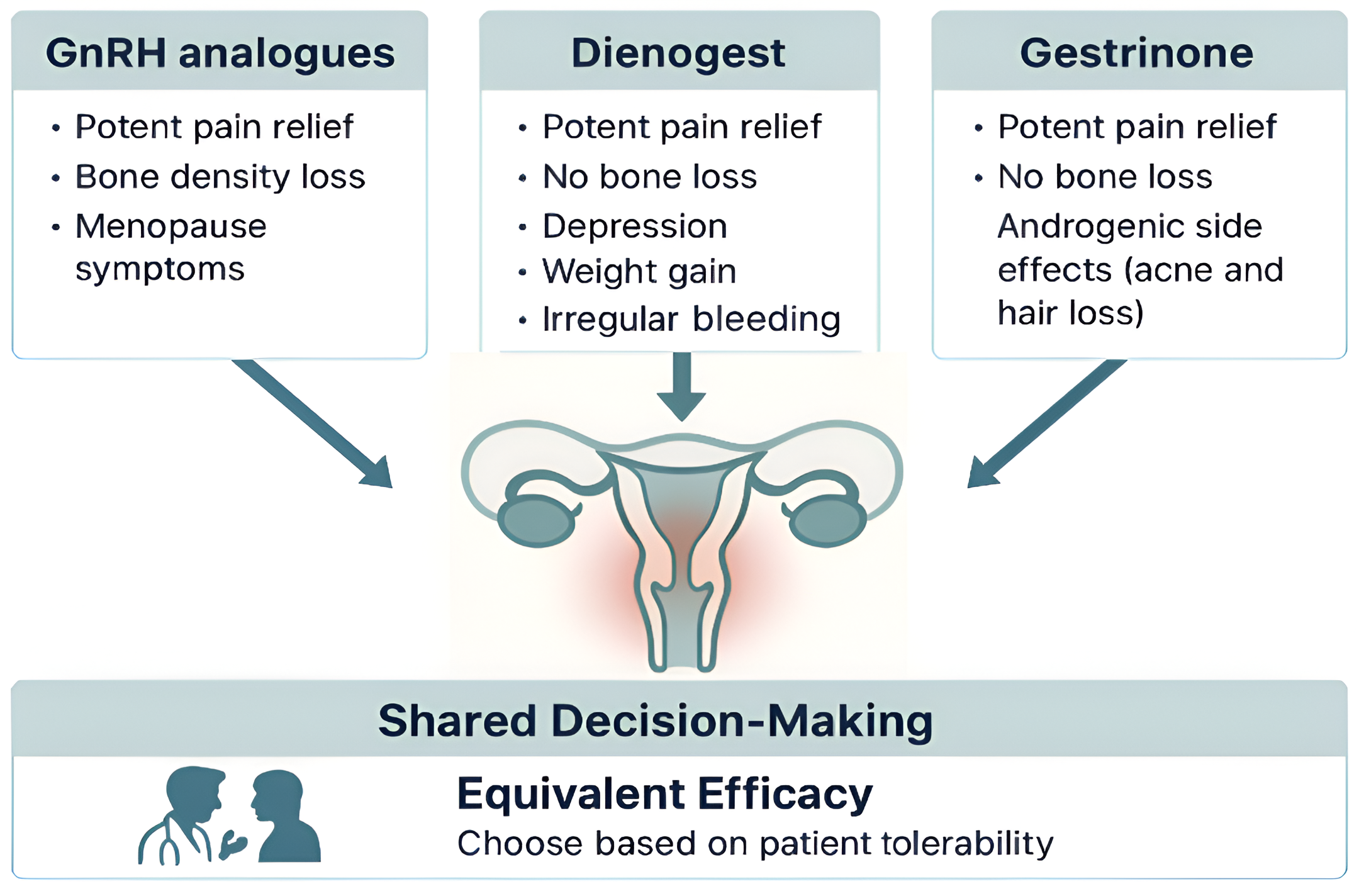

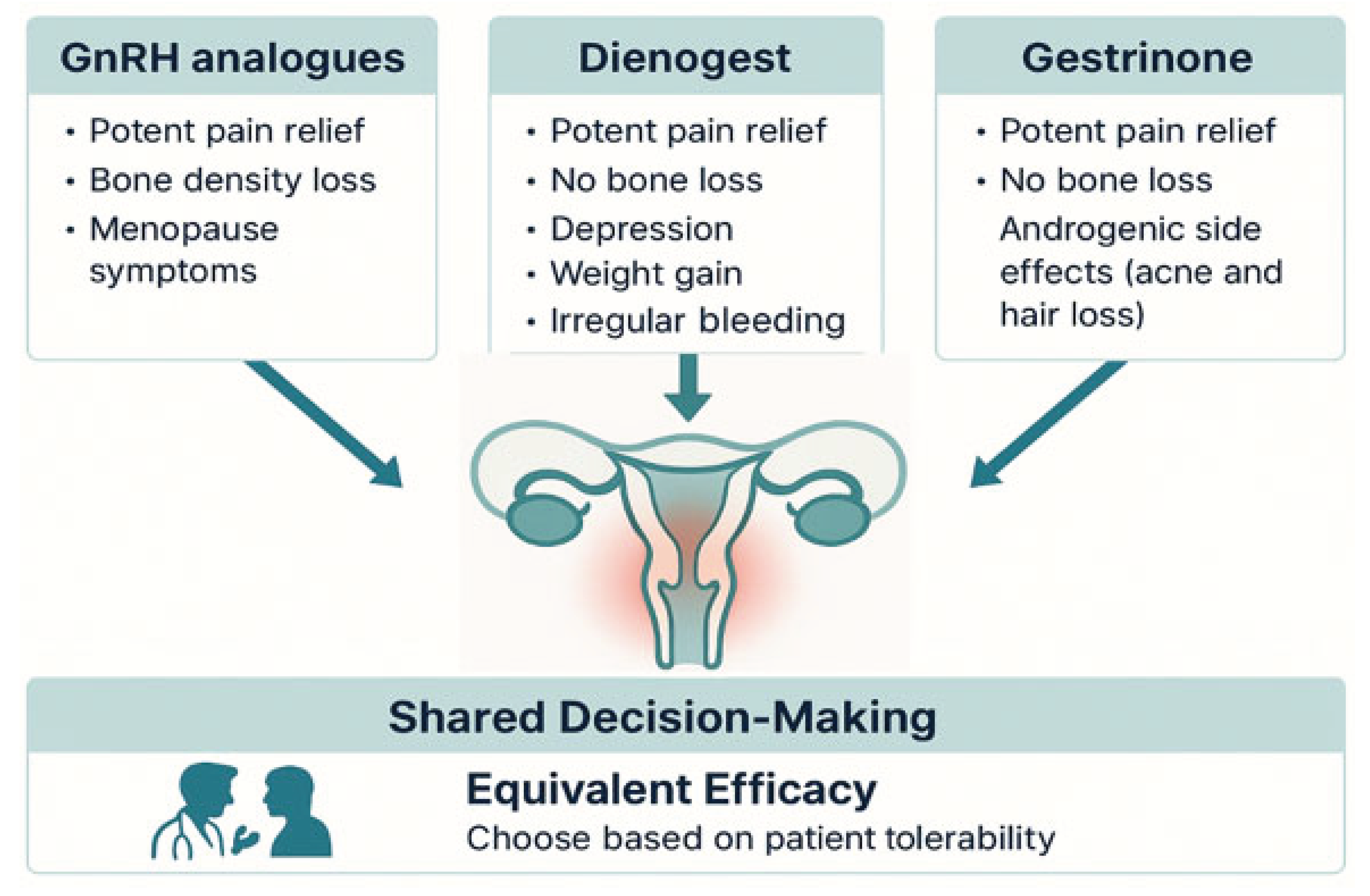

4.4. Comparative Summary of Efficacy and Safety

High-quality scientific literature, including randomised controlled trials and network meta-analyses, consistently supports the conclusion that GnRH analogues, dienogest, and gestrinone, demonstrate comparable efficacy in alleviating endometriosis-associated pain[

16,

20,

37]. Although subtle differences exist, such as the reported superiority of gestrinone for non-menstrual pelvic pain[

20], the overarching clinical message is the absence of a clear hierarchy in analgesic potency. This paradigm is summarised in

Table 1.

This equivalence in efficacy redirects the therapeutic decision-making process from a question of “which drug is most potent” to a more nuanced consideration of “which side-effect profile is most tolerable to the patient.” The most appropriate treatment thus becomes a matter of shared decision-making, wherein the physician presents a menu of equally effective options, and the patient selects the profile of adverse effects that best aligns with her personal values and lifestyle.

GnRH analogues offer potent pain relief but impose a hypoestrogenic burden, including vasomotor symptoms and, most importantly, significant bone loss, which mandates the addition of oestrogen–progestin supplementation for long-term use[

17,

22]. Dienogest achieves equivalent efficacy while preserving BMD, making it safer for extended therapy, although bleeding irregularities remain a key adherence challenge[

16,

21]. Gestrinone, meanwhile, offers similarly robust efficacy, with the added benefit of a favourable bone and cardiovascular safety profile. Its adverse effects are predominantly androgenic and aesthetic in nature, and their incidence depends largely on dosage and individual susceptibility[

24,

28].

There is no universally superior hormonal therapy for endometriosis-associated pain. Superiority is relative and patient-specific. The optimal choice is that which emerges from an informed, collaborative discussion between physician and patient, integrating clinical evidence with individual preferences and expectations (

Figure 1).

The therapeutic management of endometriosis-associated pain has evolved from a quest for superior efficacy to a more individualised approach that prioritises tolerability and patient-centred care. Robust clinical evidence indicates that GnRH analogues, dienogest, and gestrinone all offer comparable efficacy in the reduction of endometriosis-related pain[

16,

20,

38]. Consequently, the therapeutic hierarchy is no longer determined solely by potency but by the acceptability of each drug’s adverse effect profile in the context of long-term treatment.

GnRH analogues remain a powerful option for rapid and profound symptom relief. However, their use is inherently linked to a state of induced hypoestrogenism, which carries a well-established risk of vasomotor symptoms, mood disturbances, and clinically significant bone mineral density loss[

25]. Long-term treatment with these agents requires the implementation of add-back therapy to mitigate such adverse effects, following the principles of the estrogen threshold hypothesis[

22]. Modern fixed-dose combination therapies, such as relugolix with estradiol and norethindrone acetate, have been shown to preserve efficacy while maintaining skeletal safety over extended treatment periods[

14].

Dienogest represents a safer alternative for long-term therapy, with a favourable safety profile regarding BMD and a lower incidence of vasomotor symptoms. Randomised controlled trials have demonstrated that dienogest is as effective as GnRH analogues in pain reduction, while offering the advantage of bone preservation and reduced hypoestrogenic effects[

29]. However, it presents its own challenges: primarily irregular bleeding patterns and a modest but real risk of mood changes, including depressive symptoms[

28,

30,

36]. Large-scale pharmacovigilance data from the VIPOS study have documented an increased incidence of depression in dienogest users compared to other hormonal treatments[

29], and case reports have linked its use to major depressive episodes even in the absence of psychiatric history[

28].

Gestrinone offers a unique therapeutic profile. Its analgesic efficacy is not only equivalent to that of other options but may be superior in the context of non-menstrual pelvic pain[

20]. Importantly, gestrinone has shown no association with cardiovascular events or mortality in over 30 years of clinical trials[

31]. It is also bone-sparing and may even promote slight increases in BMD[

20,

38]. However, its androgenic effects, such as acne, seborrhoea, and hirsutism can impact adherence, particularly in patients sensitive to aesthetic or dermatological changes[

19,

22,

31]. These effects are dose-dependent and reversible upon discontinuation, but require thorough discussion during counselling.

In light of these data, no single agent can be universally recommended as the superior option for all patients. Instead, the ideal choice must derive from an informed, collaborative process that balances efficacy, safety, patient preferences, comorbidities, reproductive goals, and lifestyle factors. This framework of shared decision-making is increasingly recognised as a cornerstone of best practice in the management of chronic gynaecological conditions, particularly those with long-term treatment horizons and multifaceted impacts on quality of life[

1,

4].

Ultimately, the most effective therapy is not defined solely by its pharmacodynamic potency, but by the patient’s willingness and ability to adhere to it over time. Such adherence is enhanced when the treatment choice reflects the patient’s personal values, expectations, and tolerance for specific side effects. Physicians must therefore serve not only as prescribers, but as communicators and facilitators—translating scientific evidence into personalised treatment strategies that support autonomy and long-term wellbeing.

6. Limitations

This review was conducted according to the principles of a structured narrative synthesis and adheres to the SANRA guidelines to ensure methodological clarity and transparency. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. As a narrative review, this work does not include quantitative synthesis or formal meta-analytic comparisons. The conclusions drawn regarding therapeutic equivalence are based on a critical qualitative appraisal of high-level evidence, including randomized controlled trials and network meta-analyses[

16,

20,

29,

38]. While this approach allows for a clinically grounded interpretation of diverse data sources, it precludes the statistical pooling of effect sizes or formal assessments of heterogeneity.

Further limitations arise from the underlying evidence base. The heterogeneity of the primary studies in terms of design, populations, and treatment regimens limits direct comparability and generalizability across trials. Notably, no randomized clinical trial to date has directly compared all three drug classes within a single framework, meaning comparative conclusions rely on indirect analyses which are inherently less robust than head-to-head comparisons. Finally, as with all literature-based reviews, the possibility of publication bias cannot be entirely ruled out, as studies with negative or inconclusive results may be underrepresented.

With regard to gestrinone, while much of the published evidence derives from clinical trials conducted in the 1980s and 1990s, these studies were methodologically robust and remain clinically relevant. They consistently demonstrated strong analgesic efficacy, particularly in non-menstrual pelvic pain, as well as a favorable safety profile with respect to bone mineral density and cardiovascular risk. Importantly, gestrinone continues to be widely used in real-world clinical practice, particularly in Latin America and Southern Europe, where its therapeutic role is well established and supported by decades of accumulated clinical experience. Rather than constituting a limitation, the historical nature of this evidence highlights a robust legacy of use that predates the modern emphasis on patient-reported outcomes and shared decision-making metrics. Future studies incorporating contemporary tools for quality-of-life assessment and adherence monitoring would serve to expand, not validate, the existing evidence base. Future research should not only expand the evidence base with modern metrics but also explore the regulatory and pharmacoeconomic factors that currently limit gestrinone's availability in many regions, despite its long-standing clinical use and favorable safety profile.

Despite these limitations, the available evidence is sufficiently consistent and clinically compelling to support the central message of this review: that GnRH analogues, dienogest, and gestrinone all offer comparable efficacy in the management of endometriosis-associated pain. Therapeutic choice should therefore be driven not by assumptions of superiority, but by patient-specific factors such as tolerability, safety, comorbidities, and personal preferences within a shared decision-making model.

7. Conclusions

The management of endometriosis-associated pain has shifted from the pursuit of a pharmacological agent with superior efficacy to a more patient-centred framework that prioritises long-term tolerability and quality of life. High-level evidence from clinical trials and systematic reviews demonstrates that GnRH analogues, dienogest, and gestrinone offer clinically equivalent pain relief in women with endometriosis[

16,

20,

29,

38]. In this context, therapeutic selection is no longer determined by relative potency, but by the adverse effect profile most compatible with the patient’s values, comorbidities, and life circumstances.

Each treatment class presents a distinct balance between benefits and risks. GnRH analogues are potent and effective but induce a chemical menopause with predictable hypoestrogenic side effects, including significant bone mineral density loss, necessitating the use of add-back therapy for extended treatment[

17,

25,

32]. Dienogest avoids hypoestrogenic complications and preserves bone integrity, but irregular bleeding and potential mood disturbances may affect adherence[

28,

29]. Gestrinone, with its strong efficacy and absence of documented cardiovascular or skeletal harm, offers an appealing alternative, although its androgenic side effects must be carefully discussed and monitored[

19,

22,

31,

38].

In the absence of a clear hierarchy of efficacy, the therapeutic decision should be guided by a model of shared decision-making. The role of the clinician is to present the available evidence transparently, delineating the differential side-effect profiles of each option, and to support the patient in selecting a treatment aligned with her personal priorities and tolerability thresholds. The most effective therapy is not merely the one that reduces pain in clinical trials, but the one that a woman can safely and comfortably adhere to over time in the context of her lived experience.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—original draft preparation, and review and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this review are available in the cited references.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 17β-HSD2 |

17β-hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 2 |

| BMD |

Bone Mineral Density |

| ESHRE |

European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology |

| GnRH |

Gonadotropin-releasing hormone |

| HRQoL |

Health-related Quality of Life |

| MeSH |

Medical Subject Headings |

| NGF |

Nerve Growth Factor |

| PGE2 |

Prostaglandin E2 |

| PR-B |

Progesterone Receptor Isoform B |

| RCTs |

Randomised Controlled Trials |

| SANRA |

Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles |

| VAS |

Visual Analogue Scale |

References

- Della Corte, L.; Di Filippo, C.; Gabrielli, O.; Reppuccia, S.; La Rosa, V.L.; Ragusa, R.; Fichera, M.; Commodari, E.; Bifulco, G.; Giampaolino, P. The Burden of Endometriosis on Women’s Lifespan: A Narrative Overview on Quality of Life and Psychosocial Wellbeing. IJERPH 2020, 17, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zondervan, K.T.; Becker, C.M.; Missmer, S.A. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2020, 382, 1244–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bień, A.; Rzońca, E.; Zarajczyk, M.; Wilkosz, K.; Wdowiak, A.; Iwanowicz-Palus, G. Quality of Life in Women with Endometriosis: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Qual Life Res 2020, 29, 2669–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnoaham, K.E.; Hummelshoj, L.; Webster, P.; d’Hooghe, T.; De Cicco Nardone, F.; De Cicco Nardone, C.; Jenkinson, C.; Kennedy, S.H.; Zondervan, K.T. Impact of Endometriosis on Quality of Life and Work Productivity: A Multicenter Study across Ten Countries. Fertility and Sterility 2011, 96, 366–373.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fourquet, J.; Báez, L.; Figueroa, M.; Iriarte, R.I.; Flores, I. Quantification of the Impact of Endometriosis Symptoms on Health-Related Quality of Life and Work Productivity. Fertility and Sterility 2011, 96, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maulenkul, T.; Kuandyk, A.; Makhadiyeva, D.; Dautova, A.; Terzic, M.; Oshibayeva, A.; Moldaliyev, I.; Ayazbekov, A.; Maimakov, T.; Saruarov, Y.; et al. Understanding the Impact of Endometriosis on Women’s Life: An Integrative Review of Systematic Reviews. BMC Women’s Health 2024, 24, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Pavone, M.; Xue, Q.; Attar, E.; Trukhacheva, E.; Tokunaga, H.; Utsunomiya, H.; Yin, P.; Luo, X.; et al. Estrogen Receptor-β, Estrogen Receptor-α, and Progesterone Resistance in Endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med 2010, 28, 036–043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.G.; Rudnicki, M.; Yu, J.; Shu, Y.; Taylor, R.N. Progesterone Resistance in Endometriosis: Origins, Consequences and Interventions. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2017, 96, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machairiotis, N.; Vasilakaki, S.; Thomakos, N. Inflammatory Mediators and Pain in Endometriosis: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvoux, B.; D’Hooghe, T.; Kyama, C.; Koskimies, P.; Hermans, R.J.J.; Dunselman, G.A.; Romano, A. Inhibition of Type 1 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Impairs the Synthesis of 17β-Estradiol in Endometriosis Lesions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014, 99, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, T. Unveiling the Mechanisms of Pain in Endometriosis: Comprehensive Analysis of Inflammatory Sensitization and Therapeutic Potential. IJMS 2025, 26, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.; Cheng, Y.-H.; Pavone, M.; Yin, P.; Imir, G.; Utsunomiya, H.; Thung, S.; Xue, Q.; Marsh, E.; Tokunaga, H.; et al. 17β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase-2 Deficiency and Progesterone Resistance in Endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med 2010, 28, 044–050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulun, S.E. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 2009, 360, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, G.R.; Zeitoun, K.; Edwards, D.; Johns, A.; Carr, B.R.; Bulun, S.E. Progesterone Receptor Isoform A But Not B Is Expressed in Endometriosis1. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2000, 85, 2897–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokushige, N.; Markham, R.; Russell, P.; Fraser, I.S. Nerve Fibres in Peritoneal Endometriosis. Human Reproduction 2006, 21, 3001–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechsner, S.; Schwarz, J.; Thode, J.; Loddenkemper, C.; Salomon, D.S.; Ebert, A.D. Growth-Associated Protein 43–Positive Sensory Nerve Fibers Accompanied by Immature Vessels Are Located in or near Peritoneal Endometriotic Lesions. Fertility and Sterility 2007, 88, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.C.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.S.; Kotarski, J.; Archer, D.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Surrey, E.; Johnson, N.P.; Watts, N.B.; et al. Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist. N Engl J Med 2017, 377, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Kives, S.; Akhtar, M. Progestagens and Anti-Progestagens for Pain Associated with Endometriosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.; Farquhar, C. Endometriosis: An Overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014, 2014, CD009590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surrey, E.; Taylor, H.S.; Giudice, L.; Lessey, B.A.; Abrao, M.S.; Archer, D.F.; Diamond, M.P.; Johnson, N.P.; Watts, N.B.; Gallagher, J.C.; et al. Long-Term Outcomes of Elagolix in Women With Endometriosis: Results From Two Extension Studies. Obstetrics & Gynecology 2018, 132, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, A.M.; Ammar, I.M.M.; Alnemr, A.A.A.; Abdelrhman, A.A. Dienogest Versus Leuprolide Acetate for Recurrent Pelvic Pain Following Laparoscopic Treatment of Endometriosis. J Obstet Gynecol India 2018, 68, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, R.L. Hormone Treatment of Endometriosis: The Estrogenthreshold Hypothesis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1992, 166, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giudice, L.C.; As-Sanie, S.; Arjona Ferreira, J.C.; Becker, C.M.; Abrao, M.S.; Lessey, B.A.; Brown, E.; Dynowski, K.; Wilk, K.; Li, Y.; et al. Once Daily Oral Relugolix Combination Therapy versus Placebo in Patients with Endometriosis-Associated Pain: Two Replicate Phase 3, Randomised, Double-Blind, Studies (SPIRIT 1 and 2). The Lancet 2022, 399, 2267–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petraglia, F.; Hornung, D.; Seitz, C.; Faustmann, T.; Gerlinger, C.; Luisi, S.; Lazzeri, L.; Strowitzki, T. Reduced Pelvic Pain in Women with Endometriosis: Efficacy of Long-Term Dienogest Treatment. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2012, 285, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strowitzki, T.; Faustmann, T.; Gerlinger, C.; Schumacher, U.; Ahlers, C.; Seitz, C. Safety and Tolerability of Dienogest in Endometriosis: Pooled Analysis from the European Clinical Study Program. IJWH 2015, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindler, A. Dienogest in Long-Term Treatment of Endometriosis. IJWH 2011, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strowitzki, T.; Faustmann, T.; Gerlinger, C.; Seitz, C. Dienogest in the Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pelvic Pain: A 12-Week, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010, 151, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Park, J.K. Dienogest-Induced Major Depressive Disorder with Suicidal Ideation: A Case Report. Medicine 2021, 100, e27456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehner, S.; Becker, K.; Lange, J.A.; Von Stockum, S.; Heinemann, K. Risk of Depression and Anemia in Users of Hormonal Endometriosis Treatments: Results from the VIPOS Study. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology 2020, 251, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Follesa, P.; Porcu, P.; Sogliano, C.; Cinus, M.; Biggio, F.; Mancuso, L.; Mostallino, M.C.; Paoletti, A.M.; Purdy, R.H.; Biggio, G.; et al. Changes in GABAA Receptor Γ2 Subunit Gene Expression Induced by Long-Term Administration of Oral Contraceptives in Rats. Neuropharmacology 2002, 42, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoru, F.; Berretti, R.; Locci, A.; Porcu, P.; Concas, A. Decreased Allopregnanolone Induced by Hormonal Contraceptives Is Associated with a Reduction in Social Behavior and Sexual Motivation in Female Rats. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 3351–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, E.M. Treatment of Endometriosis with Gestrinone (R-2323), a Synthetic Antiestrogen, Antiprogesterone. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1982, 144, 895–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, P.L.; Bertolini, S.; Brunenghi, M.C.M.; Daga, A.; Fasce, V.; Marcenaro, A.; Cimato, M.; De Cecco, L. Endocrine, Metabolic, and Clinical Effects of Gestrinone in Women with Endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 1989, 52, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauppila, A.; Isomaa, V.; Rönnberg, L.; Vierikko, P.; Vihko, R. Effect of Gestrinone in Endometriosis Tissue and Endometrium. Fertil Steril 1985, 44, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gestrinone versus a Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist for the Treatment of Pelvic Pain Associated with Endometriosis: A Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind Study. Gestrinone Italian Study Group. Fertil Steril 1996, 66, 911–919. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. [Effect of gestrinone on the lipid metabolic parameters and bone mineral density in patients with endometriosis]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi 2005, 40, 175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Strowitzki, T.; Marr, J.; Gerlinger, C.; Faustmann, T.; Seitz, C. Dienogest Is as Effective as Leuprolide Acetate in Treating the Painful Symptoms of Endometriosis: A 24-Week, Randomized, Multicentre, Open-Label Trial. Hum Reprod 2010, 25, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercellini, P.; Cortesi, I.; Crosignani, P.G. Progestins for Symptomatic Endometriosis: A Critical Analysis of the Evidence. Fertility and Sterility 1997, 68, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).