1. Introduction

Leaf scald (LS), a disease caused by the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas albilineans (Xalb), is a major disease of sugarcane (Saccharum spp. hybrids). Its destructive impact is well-documented, leading to considerable economic losses (Rott et al., 1995; Rott and Davis, 2000). First identified in Australia in 1911 (Martin and Robinson, 1961), LS has since been detected in at least 65 countries (Rott and Davis, 2000). The widespread distribution of the disease is largely due to the exchange of symptomless but infected vegetative propagative material (seed-cane).

LS symptoms vary depending on whether the disease manifests in its chronic or acute form, as well as the prevailing weather conditions (Birch, 2001; Rott and Davis, 2000; Rott et al., 2011). A key challenge in managing LS is its prolonged latent phase, during which infected plants remain asymptomatic for weeks, months, or even years before developing visible symptoms (Rott et al., 1995). This extended asymptomatic period greatly contributes to the widespread dissemination of the disease, as infected but healthy-looking seed-cane is unknowingly propagated. The chronic form is characterized by the gradual appearance of pencil-like streaks, leaf bleaching, and necrosis, followed by the scalding of stalks and eventual stalk death. In contrast, the acute form leads to the sudden wilting and death of mature stalks without any preceding leaf symptoms. Other symptoms common to both forms include shortened stalk internodes, the presence of side shoots along the stalk, and red vascular bundles within the stalk (Martin et al., 1932; Birch, 2001). Diseased stalks often show red vascular bundles, which may be partially or completely blocked by pathogens (Birch, 2001; Blanco et al., 2010), particularly in highly susceptible cultivars.

Managing leaf scald primarily involves planting disease-free vegetative propagative material (seed cane), and resistant cultivars. Disease-free seed cane can be obtained from plants propagated through tissue culture techniques or by using hot-water treatment (Egan and Sturgess, 1980; Croft and Cox, 2013). However, screening for resistance is particularly challenging due to the extended latent period and symptom variability. Given that symptom expression can be delayed or inconsistent, early and accurate detection of Xalb in asymptomatic plants is critical for preventing further disease spread (Comstock and Irey, 1992). Therefore, the development and application of highly sensitive and efficient diagnostic tools is critical for identifying the disease in symptomless plants, particularly in seed-cane nurseries and breeding or quarantine programs (Duarte Dias et al., 2018; Garces et al., 2014). Multiple diagnostic methods have been developed to detect Xalb in infected stalks. These include isolation on Wilbrink’s medium (Ricaud and Ryan, 1989) or a semi selective medium (Davis et al., 1994), serological techniques (Alvarez et al., 1996; Comstock and Irey, 1992; Rott et al., 1994), PCR (Pan and Grisham, 1997; Pan et al., 1999; Wang et al., 1999), nested-PCR (Duarte Dias et al., 2018), quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) (Garces et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2020), and loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (Duarte Dias et al., 2018). This paper reviews the current industry-accessed diagnostic methods and opportunities from advanced technologies for more highly accurate, lower cost, and implementable future options.

2. Infection Process and Transmission

Unlike most Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria, the bacterium responsible for sugarcane leaf scald,

X. albilineans (

Figure 2b.1a), lacks the hypersensitive response and pathogenicity (Hrp) Type III secretion system (T3SS) (Pieretti et al., 2009). Additionally, this species within the

Xanthomonas genus has a notably smaller genome size of 3.8 Mb than other sequenced plant-pathogenic xanthomonads (Pieretti et al., 2009; 2012). Bacteria with reduced genomes are often associated with a high degree of specialization in specific niches and a limitation to certain host tissues (Jackson et al., 2011; Lindeberg, 2012; Purcell and Hopkins, 1996; Chatterjee et al., 2008). The pathogenicity of

Xalb, reflected in its ability to colonize sugarcane stalks and cause disease symptoms, varies among strains, indicating the presence of distinct pathotypes within the species (Daugrois et al., 2003; Champoiseau et al., 2006). A key factor in the pathogenicity of

Xalb is the production of a toxin called albicidin, which is crucial for symptom development in LS by inhibiting chloroplast differentiation (Birch and Patil, 1987a; Birch and Patil, 1987b; Birch, 2001). This inhibition leads to the characteristic white foliar stripes, although even toxin-deficient mutants of

Xalb can still cause disease symptoms (Rott et al., 2011).

Xalb spreads throughout the plant, colonizing leaves, roots, and stalks, primarily within the xylem (Birch, 2001; Klett and Rott, 1994). Microscopic examination has revealed changes in the vascular system associated with the disease, such as occlusions (Huerta-Lara et al., 2009). Whilst

Xalb was traditionally believed to be restricted to the xylem, recent studies using tagged bacteria have shown that it also invades non-vascular tissues like parenchyma and bulliform cells (Mensi et al., 2014). Meanwhile, occlusions observed in the stalk are linked to the production of a xanthan-like polysaccharide, composed of glucose, mannose, and glucuronic acid (Fontaniella et al., 2002; Blanco et al., 2010). This polysaccharide is referred to as "xanthan-like gum" because

Xalb lacks the gum gene cluster that other

Xanthomonas species use to produce xanthan gum, a crucial factor in their pathogenicity (Danhorn and Fuqua, 2007; Pieretti et al., 2015b). Additionally, it is possible that the sugarcane plant itself produces polysaccharides in response to

Xalb infection, which has also been linked to altered sucrose crystallization (Blanch et al., 2006).

LS symptoms in sugarcane, particularly in systemically infected plants, are well-documented, with two main forms of the disease recognized: chronic and acute (Rott and Davis, 2000). The chronic form manifests as white to yellow chlorotic stripes on the leaves, which can be as thin as pencil lines or several millimeters wide (

Figure 2b.1b). Emerging leaves may also display extensive white chlorosis. As the disease progresses, these stripes and chlorosis turn into areas of necrosis, leading to leaf wilting and drying. The tips of the leaves often curl inward, giving the plant a scorched appearance and the disease its name, "leaf scald." A common symptom in mature sugarcane is the abnormal growth of side shoots along the stalk, with those near the base being the most developed. The acute form of LS, characterized by the sudden wilting of mature stalks, tends to be restricted to highly susceptible sugarcane cultivars. Systemically infected plants may not always show symptoms, and the pathogen can persist in the stalks for months without causing visible signs of the disease. This asymptomatic phase, known as latency, can end for reasons that are not yet fully understood (Ricaud and Ryan, 1989).

Figure 1.

(a) Leaf scald (LS) disease-causing bacteria Xanthomonas albilineans (Xalb) under an electron microscope (adapted from Birch (2001); (b) pencil-line symptom (arrow) on LS-infected sugarcane leaf. Taken from an LS trial site at Woodford research station, Sugar Research Australia Limited (SRA), Woodford, Queensland, Australia.

Figure 1.

(a) Leaf scald (LS) disease-causing bacteria Xanthomonas albilineans (Xalb) under an electron microscope (adapted from Birch (2001); (b) pencil-line symptom (arrow) on LS-infected sugarcane leaf. Taken from an LS trial site at Woodford research station, Sugar Research Australia Limited (SRA), Woodford, Queensland, Australia.

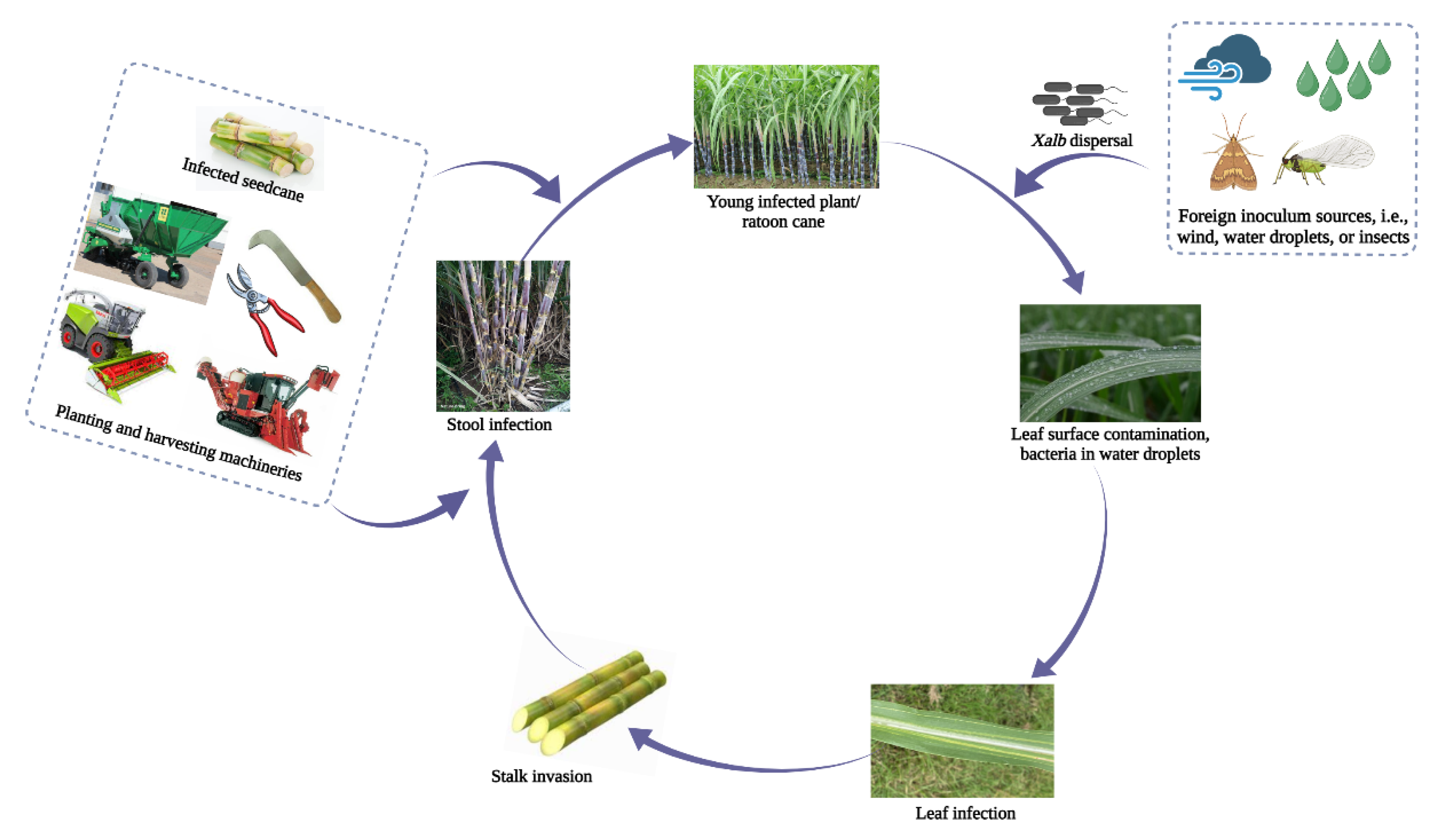

Xalb can survive outside its host plant and be transmitted aerially from unknown sources outside the field or contaminated sugarcane fields (Daugrois et al., 2003; Champoiseau et al., 2009). The pathogen can reach healthy sugarcane plants through various climatic factors, such as wind and rainfall. During harvest,

Xalb can be spread to healthy plants via contaminated tools, and infected plants may also regrow from stools that were previously inoculated either aerially or mechanically (Daugrois et al., 2012). The pathogen can also be spread through infected cuttings, with the bacteria colonizing new plants via the vascular system.

Xalb can later exude from systemically infected leaves, serving as a source of inoculum for a new disease cycle (

Figure 2

b.2).

Figure 2.

A sugarcane infection cycle of Xanthomonas albilineans (Xalb). The primary sources of infection are seed cane, contaminated planting, harvesting equipment, and environmental factors, i.e., winds, water droplets, or insects.

Figure 2.

A sugarcane infection cycle of Xanthomonas albilineans (Xalb). The primary sources of infection are seed cane, contaminated planting, harvesting equipment, and environmental factors, i.e., winds, water droplets, or insects.

3. Distribution and Economic Impact of LS

Leaf scald has been reported in at least 66 countries, primarily in regions with significant sugarcane production (Sandhu et al., 2013). The disease is believed to have originated in the East Indies and was initially confined to the Eastern Hemisphere. In Java, it was first identified as "Hundred Brown Disease," referring to the susceptibility of a particular sugarcane cultivar. The disease was later known as 'gomziekte' or gum disease, which was mistakenly thought to be the same as gummosis, caused by a similar bacterium, Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. vasculorum (Wiehe, 1951). However, these were later distinguished as separate diseases, and the Java gum disease was recognized as the same as the Australian LS, leading to the adoption of the name "leaf scald" for the disease caused by Xalb.

LS likely appeared in Australia before 1900, possibly introduced from Java or New Guinea. It was subsequently reported in other Eastern Hemisphere countries, including Fiji (1911), Taiwan (1919), the Philippines (1921), Mauritius (1928), and Madagascar (1936). The disease reached the Western Hemisphere via Brazil between 1926 and 1930 and was likely introduced into Guyana around the same time. In South America and the Caribbean, LS has been recorded in countries such as Argentina, Suriname, Martinique, Puerto Rico, and St. Lucia. In Hawaii, the first report of LS occurred in 1930, although evidence suggests the disease had been present for several years prior (Martin, 1938; Martin & Robinson, 1961).

There have been frequent outbreaks of LS in various countries, sometimes for unknown reasons. For example, a significant epidemic occurred in Mauritius in 1964, which seemed related to a loss of resistance in two sugarcane cultivars (Ricaud & Perombelon, 1964). Another serious epidemic in Mauritius in 1989 was attributed to the aerial transmission of the bacterium (Autrey et al., 1992b). Brazil, as the world’s leading sugarcane producer, has also experienced significant outbreaks of LS, which have contributed to severe yield losses in a commercial sugarcane field (González et al., 2024). These outbreaks are often linked to factors such as climatic conditions, the movement of infected planting material, variations in cultivar resistance, and insect vectors (Daugrois et al., 2012; Bini et al., 2023). The number of regions affected by LS continues to rise, with outbreaks reported in Cuba (Diaz et al., 2021), Mexico (García-Juárez et al., 2015), Florida (Comstock & Shine, 1992), Guadeloupe (Rott et al., 1994), Guatemala (Ovalle et al., 1995), Louisiana (Grisham et al., 1994), Mauritius (Autrey et al., 1995), Taiwan (Chen et al., 1993), and Texas (Isakeit & Irvine, 1995). In Florida, the disease has been linked to a new pathogenic strain (Davis, 1992). LS is primarily found in countries such as Australia, the USA, the Philippines, Myanmar, Thailand, Java, Laos, India, and Vietnam (Viswanathan et al., 1997; Saumtally et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2017). In China, it is now considered the most important quarantine disease in regions including Taiwan, Guangxi, Guangdong, Yunnan, Fujian, Jiangxi, Zhejiang, and Hainan (Li et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2018; Duan et al., 2021). The latest reports of new locations include Louisiana (Grisham et al., 1994), Guatemala (Ovalle et al., 1995), Texas (Saumtally et al., 2004), and Gabon (Mensi et al., 2013).

The degree of infection and severity of LS varies depending on the susceptibility of the sugarcane cultivar and the conditions in which it is grown. For example, the cultivar Yellow Caledonia is considered highly resistant in Australia but has shown susceptibility under certain conditions in Hawaii, such as during retarded cane growth due to low soil fertility, drought, and maturity (Martin, 1938).

LS can devastate plantations of susceptible cultivars within a few months or years, causing significant declines in cane yields at harvest and affecting the quality of extracted juice, particularly with the acute form of the disease (Hoy & Grisham, 1994). In Guadeloupe, Cochereau & Jean-Bart (1989), estimated crop losses from the disease are 13 t/ha. On the same island, field yield losses of 15-20% were reported for the susceptible cultivar B69379 (Rott et al., 1995). In Mexico, the disease was first detected in 1992, resulting in the destruction of 800 ha of the cultivar Mex64-1487. Currently, Mex69-290, which occupies 150,000 ha (25% of the sugarcane area), remains relatively unaffected, although preliminary studies indicate that it is susceptible.

In Australia, infected sugarcane fields suffer from reduced yields, with reports of a 20% decrease in the number of stalks and a reduction in sucrose content, ultimately affecting sugar quality (Hoy & Grisham, 1994; Sugarcane Research Australia, 2014). The disease not only reduces cane tonnage and sugar yield but also incurs additional costs for replanting, including the use of micro-propagated plantlets, heat treatment, and selection of resistant cultivars (Escober et al., 1980; Rott, 1995). High-yielding cultivars susceptible to LS, such as Q63 in Australia, B69379 in Guadeloupe, and M 69569 in Mauritius, should not be cultivated (Egan, 1971; Rott & Feldmann, 1991; Autrey et al., 1992b). Recent outbreaks in Louisiana have resulted in the loss of promising clones, necessitating changes in varietal improvement strategies (Hoy & Grisham, 1994).

4. Current Management Practices for LS and Their Limitations

Leaf scald (LS) in sugarcane is best managed by planting healthy seed cane and utilizing resistant cultivars (Rott and Davis, 2000).

Healthy seed cane: Healthy seed cane can be produced from plants derived from disease-free tissue culture propagation (Flynn and Anderlini, 1990; Feldmann et al., 1994) or through hot-water treatment. For hot water treatment, two methods are used to eliminate Xalb from seed cane: long hot water treatment (LHWT) and cold soak long hot water treatment (CS-LHWT). In LHWT, the canes are treated at 50°C for three hours. In CS-LHWT, the canes are soaked at ambient temperature for 40 to 48 hours, followed by a three-hour treatment at 50°C (Egan and Sturgess, 1980; Croft and Cox, 2013). A specific protocol involving a 40-hour soak in cold running water (15-25°C) followed by a 3-hour hot water soak at 50°C has been shown to eliminate Xalb, the causal pathogen of LS, with 95% control efficacy (Egan and Sturgess, 1980; Huang and Li, 2016). However, testing of propagative material, including non-tissue culture plants, is equally essential for detecting latent infections that can go unnoticed during the early stages of disease development. Even when propagative material is not derived from tissue culture, the pathogen can still be present and spread, making testing and early detection vital for disease management.

Resistant cultivars: The development and use of resistant sugarcane cultivars is pivotal and varietal screening tests have been established to identify and eliminate susceptible plants. Accurate determination of a genotype's resistance to Xalb is essential for the success of breeding programs. However, due to the erratic expression of LS symptoms susceptibility is often difficult to detect accurately (Comstock and Irey, 1992). Simultaneously, the development and use of marker sequences linked to identified and functionally relevant resistance genes in the plant would be hugely beneficial in selective resistance breeding strategies. (Costet et al., 2012). Alternatively, transgenically modified plants resistant to Xalb have been developed through the introduction of the albicidin detoxification (albD) gene via microprojectile bombardment (Birch et al., 2000). However, the spread of LS cannot be fully controlled by resistant cultivars alone, as even the most resistant genotypes can harbor low levels of the bacteria (Rott et al. 1997).

Antibiotics: Spraying antibiotics like streptomycin + tetracycline (60 g/ha in 500 L of water) or Plantomycin (250 g/ha in 500 L of water) at 2-week intervals is effective in managing Xalb in the field, particularly when applied two months after planting (Viswanathan and Padmanaban, 2008). Early-stage spraying of these antibiotics can reduce the severity of LS. However, it is not an effective way to eliminate the pathogen.

Biological control: Biological control methods have shown promise in managing LS. Pantoea dispersa (formerly Erwinia herbicola) has demonstrated strong extracellular detoxification of albicidin and provided effective biocontrol against Xalb in highly susceptible sugarcane cultivars (Zhang and Birch, 1996). Additionally, Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus may play a significant role in the defense of Xalb, as it inhibits the in vitro growth of Xalb (Blanco et al., 2005; Piñón et al., 2002; Arencibia et al., 2006). Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) also offer a biological alternative for LS control, producing antimicrobial peptides (bacteriocins) and other substances such as hydrogen peroxide, lactic acid, and reuterin that are effective against a range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including Xalb. These antimicrobial peptides are considered alternatives to conventional pesticides and antibiotics (Keymanesh et al., 2009).

Preventive measures: As an essential management strategy, prophylactic measures are also necessary to prevent further spread of the disease, which includes destroying diseased material, disinfecting cutting tools with bactericides, and enforcing strict phytosanitary controls before introducing plant material (quarantine).

Despite well-recognized management practices, LS continues to challenge sugarcane industries worldwide due to several practical issues. Growers often avoid heat treatment, despite its effectiveness, because of its potential negative impact on germination and the risk of incomplete treatment (Mehdi et al. 2024). The lack of LS-resistant cultivars exacerbates the problem, making it difficult to control the disease effectively. Additionally, recontamination of healthy crops is common, especially when growers use planting materials from nearby sources or their infected crops (Croft et al. 2000). The expense, labor intensity, and time required for effective management methods further deter the thorough implementation of these control measures. Moreover, many sugarcane cultivars can tolerate the LS pathogen without showing symptoms, or the symptoms may be too mild to detect, allowing the disease to persist unnoticed. These challenges highlight the importance of detecting infected seed cane in propagation nurseries to prevent the introduction of the pathogen into new crops and ensure more effective LS control.

5. Traditional and Advanced Detection Methods for Xalb

Sugarcane leaf scald is typically diagnosed by symptoms, but the delayed and inconsistent expression can lead to misidentifying infected plants as healthy, contributing to its global spread through seemingly disease-free planting materials (Rott, 1995). To improve the diagnosis of X. albilineans, methods beyond symptom observation may be employed, including isolation on selective culture media, plant inoculation, and biochemical, immunological, and molecular assays.

Selective media and serological methods: Current methods for Xalb detection primarily involve culturing on general plating media, such as Wilbrink’s medium (Ricaud & Ryan, 1989), or on semiselective media specifically for Xalb (Davis et al., 1994). Additionally, serological assays like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), dot immunobinding assay (DIA), and tissue blot immunosorbent assay (TBIA), utilizing either monoclonal or polyclonal antisera, have been developed (Tsai et al., 1990; Comstock & Irey, 1992; Rott et al., 1994). These assays have a detection threshold of around 105 cfu/mL, which may not always accurately identify the presence of Xalb in asymptomatic infected sugarcane stalks (Autrey et al., 1990; Irey & Comstock, 1991). While culturing on semi-selective media is more sensitive than serological methods and can detect lower bacterial titers, it requires 6–8 days for the pathogen to form characteristic colonies and is limiting in time-sensitive situations (Davis et al., 1994; Rott, 1995). DAC-ELISA and dot blot techniques have been standardized for detecting the bacterium in infected canes (Viswanathan and Ramesh, 2004). Among immunofluorescence, ELISA, and latex flocculation methods, direct ELISA has proven to be the most sensitive, detecting bacteria at concentrations as low as 104 cells/mL (Autrey et al., 1990). Comparatively, while ELISA is less effective than other techniques like Wilbrink’s medium isolation, it remains a valuable tool due to its efficiency in detecting Xalb in both symptomatic and symptomless plants (Davis et al., 1994). The Xalb selective medium (XAS), based on Wilbrink’s medium and developed by Davis et al. (1994), incorporates antibiotics and fungicides to selectively isolate Xalb, aiding in the identification of this slow-growing bacterium. However, dot blot and tissue blot techniques are ineffective for detecting Xalb at low concentrations, with positive results only achievable at densities of 105 cfu/mL (Wang et al., 1999).

Molecular methods: Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) protocols have been developed to detect X. albilineans in diseased sugarcane stalks. The initial PCR-based diagnostic test targeted genes involved in the biosynthesis of albicidin, a toxin produced by Xalb, and was effective in detecting the pathogen both in vitro and in sugarcane juice, especially when used in multiplex PCR (Davis et al., 1995). Primer sets such as Ala4/L1 (Pan et al., 1997) and PGBL1/PGBL2 (Pan et al., 1999), based on the ITS region between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes of Xalb, demonstrated efficient detection of bacterial populations down to 103 cfu/mL (Davis et al., 1998; Wang et al., 1999). However, Pan et al. (1999) reported successful detection in only 3 out of 15 asymptomatic plants, while Urashima and Zavaglia (2012) achieved 100% detection with conventional PCR, even in asymptomatic samples. Additionally, primers derived from DNA repetitive sequences, such as BOX and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC), allowed clear differentiation of Xalb from other bacteria (Lopes et al., 2001).

Garces et al. (2014) developed TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR assays targeting the albI gene involved in albicidin biosynthesis. While the TaqMan probe, which labels two quenchers (ZEN and ABkFQ), is complex and targets duplicated sequences in the Xalb genome, it provides high sensitivity. Wang et al. (2020) introduced a SYBR Green qPCR method based on the hrpB gene, but it may produce more false positives due to nonspecific reactions or primer dimers (Cao and Shockey, 2012). Shi et al. (2021) further improved qPCR sensitivity with a novel primer pair (XaABCF3/XaABCR3) and a new TaqMan probe (XaABCP3), achieving 100-fold greater sensitivity than conventional PCR for detecting Xalb in symptomless stalk juices. This qPCR assay, alongside those developed by Garces et al. (2014) and Wang et al. (2020), maintains the lowest detection limit of 100 copies/μl of genomic DNA, 100 fg/μl of bacterial genomic DNA, and 100 CFU/ml of cell suspension.

Further enhancements in PCR-based detection include nested PCR, which amplifies the region between the 16S rRNA and 23S rRNA genes, increasing specificity and sensitivity compared to conventional PCR (Honeycutt et al., 1995; Dias et al., 2019). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), another technique employed for detecting Xalb, uses a set of six primers for auto-cycling strand displacement DNA synthesis and produces large amounts of DNA and by-products, such as hydroxy naphthol blue (HNB) (Nagamine et al., 2002; Fischbach et al., 2015; Goto et al., 2009). Although qPCR is highly effective for detecting LS (Ginzinger, 2002), methods like LAMP and nested PCR have limitations. Isolation on selective media, while effective, is time-consuming and labor-intensive (Wang et al., 1999). Immunological and molecular methods, although robust and sensitive, require sophisticated laboratory setups, significant initial investment, and skilled labor, making them less suitable for on-farm application. Additionally, LAMP and nested PCR methods, despite their low detection limits, cannot easily determine pathogen population densities, and nested PCR requires an additional gel electrophoresis step (Dias et al., 2018).

Electrochemical detection: To address the limitations of traditional diagnostic methods, nanotechnology has emerged as a promising approach in both medical and agricultural diagnostics (Prasad et al., 2017). Recent advancements include the development of sensitive electrochemical biosensors that utilize nanoparticles to enhance detection capabilities. For instance, Umer et al. (2021) developed an electrochemical biosensor assay for detecting LS disease in sugarcane, which employs gold nanoparticles. This biosensor allows for dual detection: it provides qualitative results through a color change visible to the naked eye, and it can quantify target DNA at femtomolar levels using electrochemistry. Despite its high sensitivity and accuracy, the complex fabrication of these sensors poses challenges for their application in field conditions.

6. Challenges in On-Farm Detection of LS

Current diagnostic methods for detecting Xalb, including serological, molecular, and nanotechnology-based approaches, face significant challenges that limit their on-farm application. The time required for comprehensive sampling, transport, and handling can result in missed targets, degradation due to temperature fluctuations, and potential damage from chemical or enzymatic activity (Bakhtari, 2014; Maier et al., 2010). Serological assays using polyclonal antibodies may suffer from cross-reactivity with nonspecific targets (Rott et al., 1994), while monoclonal antibodies, though more specific, are costly and difficult to produce (Engvall, 2010). Additionally, antigenic variation among Xalb strains complicates accurate detection (Rott et al., 1986). Molecular methods require genomic DNA extraction from sugarcane samples, but PCR-based assays face issues with inhibitors in plant tissues—such as polysaccharides, proteins, and phenolic compounds—that can interfere with the reaction (Hedman and Rådström, 2013; Raˇcki et al., 2014; Schori et al., 2013), making these substances difficult to detect and remove from the extraction process (Martinelli et al., 2015). Furthermore, advanced diagnostic assays often lack portability and require expensive equipment, which severely restricts their use in under-resourced and field conditions.

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

In recent years, novel nanomaterials designed to enhance signal transduction and achieve ultrasensitive detection, along with integrated microfabricated devices for portable analysis, have made significant strides (Lim et al., 2015). Despite these advances in biomedical applications, their use in diagnosing plant-disease-causing pathogens remains limited. Integrated devices suitable for growers and diagnosticians would facilitate early and rapid on-farm or on-site testing throughout the growing season, eliminating the need for time-consuming sample preparation.

While some field-deployable methods, such as LAMP-based devices, have been developed for plant pathogen analysis, they still require additional equipment for sample preparation, and no such methods have been created specifically for Xalb (Ocenar et al., 2019; Prasannakumar et al., 2021; Rafiq et al., 2021). Although nanoparticle-based electrochemical methods for quantifying Xalb infections have been reported (Umer et al., 2021), more research is needed to develop a practical device for on-site testing. Most current methods are proof-of-concept demonstrations dependent on complex sensor fabrication and extensive optimization in well-equipped laboratories.

Despite progress in molecular and biosensor-based diagnostic technologies, the early-stage detection and quantification of Xalb DNA remains a significant challenge. Traditional methods such as microscopy, ELISA, and qPCR are resource-intensive, require centralized laboratories, and can delay disease identification by 1-2 weeks, which limits their utility for on-farm applications. In contrast, Loop-mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) has emerged as a promising field-deployable tool due to its rapid, specific detection without the need for a thermocycler. However, current LAMP protocols still require nucleic acid extraction, which complicates early and real-time use in the field (Prasannakumar et al., 2021). Electrochemical biosensors have also gained attention in plant pathology for their ability to offer label-free detection, minimal sample preparation, and real-time quantification. Nonetheless, these systems still require further refinement for effective deployment in agricultural settings (Umer et al., 2021).

This thesis addresses these challenges by developing two novel diagnostic methods: a colorimetric and fluorescence-based LAMP technique designed for rapid, portable detection with minimal equipment, and an innovative electrochemical biosensor aimed at providing low-cost, on-site pathogen quantification. Both methods will be validated against traditional PCR-based techniques to evaluate their feasibility for field use in sugarcane diagnostics. These advancements offer promising solutions for the early detection of Xalb and other pathogens, which could significantly improve pathogen management and help mitigate productivity losses in sugarcane cultivation. Ongoing optimization of these tools will be essential to fully realize their potential for widespread agricultural use.

Funding

Griffith University Higher Degree Research Scholarships for the First and third authors. Sugar research Australia funding through the Australian Research Council via Linkage Project (LP200100016).

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors do not have a conflict of interests.

Acknowledgments

Australian Government through the ARC Linkage project, and Sugar Research Australia financially supported this work.

References

- Alvarez, A.M., Schenck, S., Benedict, A.A., 1996. Differentiation of Xanthomonas albilineans strains with monoclonal antibody reaction patterns and DNA fingerprints. Plant Pathol. 45, 358-366. [CrossRef]

- Arencibia, A.D., Vinagre, F., Estevez, Y., Bernal, A., Perez, J., Cavalcanti, J., et al., 2006. Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus elicits a sugarcane defense response against a pathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas albilineans. Plant Signal. Behav. 1(5), 265-273. [CrossRef]

- Autrey, L.J.C., Saumtally, S., Dookun, A., Sullivan, S., Dhayan, S., 1992b. Aerial transmission of the leaf scald pathogen, Xanthomonas albilineans. Proc. 21st Int. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol. Congress, Bangkok, Thailand, 135-136.

- Autrey, L.J.C., Dookun, A., Saumtally, S., 1990. Improved serological methods for diagnosis of the leaf scald bacterium, Xanthomonas albilineans. Proc. Int. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol. 20, 704-713.

- Autrey, L.J.C., Saumtally, S., Dookun, A., Sullivan, S., Dhayan, S., 1995. Aerial transmission of leaf scald pathogen, Xanthomonas albilineans. Proc. Int. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol. 21, 508-526.

- Bakhtari, A., 2014. Managing odour sample degradation through on-site olfactometry and proper sample transportation and storage. Chem. Eng. Trans. 40, 163-168. [CrossRef]

- Birch, R., Bower, R., Elliott, A., Hansom, S., Basnayake, S., Zhang, L., 2000. Regulation of transgene expression: Progress towards practical development in sugarcane, and implications for other plant species. In: Proc. Int. Symp. Plant Genet. Eng., Havana, Cuba: Elsevier Science, 1999, pp. 1-12.

- Birch, R.G., Patil, S.S., 1987a. Correlation between albicidin production and chlorosis induction by Xanthomonas albilineans, the sugarcane pathogen. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 30, 199-206. [CrossRef]

- Birch, R.G., Patil, S.S., 1987b. Evidence that an albicidin-like phytotoxin induces chlorosis in sugarcane leaf scald disease by blocking plastid DNA replication. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 30, 207-214. [CrossRef]

- Birch, R.G., 2001. Xanthomonas albilineans and the antipathogenesis approach to disease control. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Blanch, M., Rodríguez, C.W., Legaz, M.E., Vicente, C., 2006. Modifications of sucrose crystallization by xanthans produced by Xanthomonas albilineans, a sugarcane pathogen. Sugar Tech 8, 255-259.

- Blanco, Y., Blanch, M.A., Piñón, D., Legaz, M.E., Vicente, C., 2005. Antagonism of Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus against Xanthomonas albilineans studied in alginate-immobilized sugarcane stalk tissues. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 99(4), 366-371. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, Y., Legaz, M.E., Vicente, C., 2010. Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus, a sugarcane endophyte, inhibits xanthan production by sugarcane-invading Xanthomonas albilineans. J. Plant Interact. 5, 241-248. [CrossRef]

- Cao, H., Shockey, J.M., 2012. Comparison of TaqMan and SYBR Green qPCR methods for quantitative gene expression in tung tree tissues. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 12296-12303. [CrossRef]

- Champoiseau, P., Rott, P., Daugrois, J.H., 2009. Epiphytic populations of Xanthomonas albilineans and subsequent sugarcane stalk infection are linked to rainfall in Guadeloupe. Plant Dis. 93, 339-346. [CrossRef]

- Champoiseau, P., Daugrois, J.H., Girard, J.C., Royer, M., Rott, P., 2006. Variation in albicidin biosynthesis genes and in pathogenicity of Xanthomonas albilineans, the sugarcane leaf scald pathogen. Phytopathology 96, 33-45. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., Almeida, R.P.P., Lindow, S., 2008. Living in two worlds: the plant and insect lifestyles of Xylella fastidiosa. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 46, 243-271. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T., Lin, C.P., Liang, Y.G., 1993. Leaf scald of sugarcane in Taiwan. Taiwan Sugar 40, 8-16.

- Chen, Y., Wang, Z., Liu, Y., Wang, X., Li, Y., Ma, P., Gu, B., Li, H., 2018. Recent advances in rapid pathogen detection method based on biosensors. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 37, 1021-1037. [CrossRef]

- Comstock, J.C., Irey, M.S., 1992. Detection of the leaf scald pathogen, Xanthomonas albilineans, using tissue blot immunoassay, ELISA, and isolation techniques. Plant Dis. 76, 1033-1035.

- Comstock, J.C., Shine, J.M., 1992. Outbreak of leaf scald of sugarcane, caused by Xanthomonas albilineans, in Florida. Plant Dis. 76, 426. [CrossRef]

- Costet, L., Cunff, L., Royaert, S., Raboin, L.M., Hervouet, C., Toubi, L., et al., 2012. Haplotype structure around Bru1 reveals a narrow genetic basis for brown rust resistance in modern sugarcane cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 125, 825-836. [CrossRef]

- Croft, B., Magarey, R., Whittle, P., 2000. Disease management. In: Manual of Cane Growing (eds Hogarth, D.M., Allsopp, P.G.). SRA, Brisbane.

- Croft, B.J., Cox, M., 2013. Procedures for the establishment and operation of approved seed plots. Sugar Research Australia Ltd. https://elibrary.sugarresearch.com.au/handle/11079/15325.

- Danhorn, T., Fuqua, C., 2007. Biofilm formation by plant-associated bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 401-422. [CrossRef]

- Daugrois, J.H., Dumont, V., Champoiseau, P., Costet, L., Boisne-Noc, R., Rott, P., 2003. Aerial contamination of sugarcane in Guadeloupe by two strains of Xanthomonas albilineans. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 109, 445-458. [CrossRef]

- Daugrois, J.H., Boisne-Noc, R., Champoiseau, P., Rott, P., 2012. The revisited infection cycle of Xanthomonas albilineans, the causal agent of leaf scald of sugarcane. Funct. Plant Sci. Biotechnol. 6(2), 91-97.

- Davis, M.J., 1992. Increased incidence of leaf scald disease in Florida associated with a genetic variant of Xanthomonas albilineans. Sugar Y Azúcar 87(6), 34.

- Davis, M.J., Rott, P., Baudin, P., Dean, J.L., 1994. Evaluation of selective media and immunoassays for detection of Xanthomonas albilineans, causal agent of sugarcane leaf scald disease. Plant Dis. 78, 78-82. [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.J., Rott, P., Astua-Monge, G., 1998. Multiplex, nested, PCR for detection of Clavibacter xyli subsp. xyli and Xanthomonas albilineans. Phytopathology 88(9 Suppl), S20.

- Davis, M.J., Warmuth, C.J., Rott, P., Chatenet, M., Baudin, P., 1994. Worldwide genetic variation in Xanthomonas albilineans. ISSCT.

- Dias, D.V., Fernandez, E., Cunha, M.G., Pieretti, I., Hincapie, M., Roumagnac, P., Comstock, J.C., Rott, P., 2018. Comparison of loop-mediated isothermal amplification, polymerase chain reaction, and selective isolation assays for detection of Xanthomonas albilineans from sugarcane. Trop. Plant Pathol. 43, 351-359. [CrossRef]

- Dias, V.D., Carrer Filho, R., de Campos Dianese, É., da Cunha, M.G., 2019. Detection of sugarcane leaf scald from latent infections. Científica 47(1), 21-27. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M., Peralta, E.L., Iglesia, A., Pazos, V., Carvajal, O., Perez, M.P., Giglioti, E.A., Gagliardi, P.R., Wendland, A., Camargo, L.E.A., 2001. Xanthomonas albilineans haplotype B responsible for a recent sugarcane leaf scald disease outbreak in Cuba. Plant Dis. 85, 334. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.Y., Zhang, Y.Q., Xu, Z.X., Lin, Y., Mao, L.R., Wang, W.H., Deng, Z.H., Huang, M.T., Gao, S.J., 2021. First report of Xanthomonas albilineans causing leaf scald on two chewing cane clones in Zhejiang province, China. Plant Dis. 105, 485. [CrossRef]

- Egan, B.T., Sturgess, O.W., 1980. Commercial control of leaf scald disease by thermotherapy and a clean seed program. Proc. Int. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol. 17, 1602–1606.

- Engvall, E., 2010. The ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Clin. Chem. 56, 319–320. [CrossRef]

- Feldmann, P., Sapotille, J., Grédoire, P., Rott, P., 1994. Micropropagation of sugar cane. In: Teisson, C. (Ed.), In Vitro Culture of Tropical Plants. La Librairie du Cirad, Montpellier, France, pp. 15–17.

- Fischbach, J., Xander, N.C., Frohme, M., Glökler, J.F., 2015. Shining a light on LAMP assays—A comparison of LAMP visualization methods including the novel use of berberine. Biotechnol. Tech. 58, 189–194. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.L., Anderlini, T.A., 1990. Disease incidence and yield performance of tissue culture generated seedcane over the crop cycle in Louisiana. J. Am. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol. 10, 113.

- Fontaniella, B., Rodriguez, C.W., Piñón, D., Vicente, C., Legaz, M.E., 2002. Identification of xanthans isolated from sugarcane juices obtained from scalded plants infected by Xanthomonas albilineans. J. Chromatogr. B 770, 275–281. [CrossRef]

- Garces, F.F., Gutierrez, A., Hoy, J.W., 2014. Detection and quantification of Xanthomonas albilineans by qPCR and potential characterization of sugarcane resistance to leaf scald. Plant Dis. 98, 121–126. [CrossRef]

- García-Juárez, H.S., Ortiz-García, C.F., Salgado-García, S., Valdez-Balero, A., Silva-Rojas, H.V., Ovalle-Sáenz, W.R., 2015. Presence of Xanthomonas albilineans (Ashby) Dowson in sugarcane crops in La Chontalpa, Tabasco, México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 48, 397–404. [CrossRef]

- Ginzinger, D.G., 2002. Gene quantification using real-time quantitative PCR: An emerging technology hits the mainstream. Exp. Hematol. 30, 503–512. [CrossRef]

- Goto, M., Honda, E., Ogura, A., Nomoto, A., Hanaki, K., 2009. Colorimetric detection of loop mediated isothermal amplification reaction by using hydroxy naphthol blue. Biotechnol. Tech. 46, 167–172. [CrossRef]

- Grisham, M.P., Legendre, B.L., Comstock, J.C., 1994. First report of leaf scald, caused by Xanthomonas albilineans, of sugarcane in Louisiana. Plant Dis. 77, 537. [CrossRef]

- Hedman, J., Rådström, P., 2013. Overcoming inhibition in real-time diagnostic PCR. In: Wilks, M. (Ed.), PCR Detection of Microbial Pathogens. Methods in Molecular Biology, Vol. 943. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp. 17–48.

- Honeycutt, R.J., Sobral, B.W., McClelland, M., 1995. tRNA intergenic spacers reveal polymorphisms diagnostic for Xanthomonas albilineans. Microbiology 141, 3229–3239. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Li, W., 2016. Colored Atlas of Control on Diseases, Insect Pests and Weeds of Modern Sugarcane. China Agriculture Press, Beijing.

- Huerta-Lara, M., Cárdenas-Soriano, E., Rojas-Martínez, R.I., López-Olguín, J.F., Reyes-López, D., Bautista-Calles, J., Romero-Arenas, O., 2009. Vascular bundle occlusion as a measure of sugarcane resistance to Xanthomonas albilineans. Interciencia 34, 247–251.

- Irey, M.S., Comstock, J.C., 1991. Use of an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect leaf scald pathogen, Xanthomonas albilineans, in sugarcane. J. Am. Soc. Sugar Cane Technol. 11, 48–52.

- Irvine, J.E., Amador, M., Gallo, R.M.I., Riess, C.M., Comstock, J.C., 1993. First report of leaf scald, caused by Xanthomonas albilineans, of sugarcane in Mexico. Plant Dis. 77, 846. [CrossRef]

- Isakeit, T., Irvine, J.E., 1995. First report of leaf scald, caused by Xanthomonas albilineans, of sugarcane in Texas. Plant Dis. 79, 860. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.W., Johnson, L.J., Clarke, S.R., Arnold, D.L., 2011. Bacterial pathogen evolution: breaking news. Trends Genet. 27, 32–40. [CrossRef]

- Keymanesh, K., Soltani, S., Sardari, S., 2009. Application of antimicrobial peptides in agriculture and food industry. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 25, 933–944. [CrossRef]

- Klett, P., Rott, P., 1994. Inoculum sources for the spread of leaf scald disease of sugarcane caused by Xanthomonas albilineans in Guadeloupe. J. Phytopathol. 142, 283–291. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.F., Huang, Y.K., 2012. Diagnosis, Detection and Control Technology of Modern Sugarcane Diseases. China Agriculture Press, Beijing.

- Lim, J.W., Ha, D., Lee, J., Lee, S.K., Kim, T., 2015. Review of micro/nanotechnologies for microbial biosensors. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 3, 61. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.H., Ntambo, M.S., Rott, P.C., Wang, Q.N., Lin, Y.H., Fu, H.Y., Gao, S.J., 2018. Molecular detection and prevalence of Xanthomonas albilineans, the causal agent of sugarcane leaf scald, in China. Crop Prot. 109, 17–23. [CrossRef]

- Lindeberg, M., 2012. Genome-enabled perspectives on the composition, evolution, and expression of virulence determinants in bacterial plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 50, 111–132. [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.A., Damann, K., Grelen, L., 2001. Xanthomonas albilineans diversity and identification based on Rep-PCR fingerprints. Curr. Microbiol. 42, 155–159. [CrossRef]

- Maier, T.S., Kuhn, J., Müller, C., 2010. Proposal for field sampling of plants and processing in the lab for environmental metabolic fingerprinting. Plant Methods 6, 6. [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.P., 1938. Sugarcane Diseases in Hawaii. Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association, Hawaii, 295 pp.

- Martin, J.P., Carpenter, C.W., Weller, D.M., 1932. Leaf scald disease of sugar cane in Hawaii. Plan. Rec. 36, 145–196.

- Martin, J.P., Robinson, P.E., C.G., 1961. Leaf scald. In: Martin, J.P., Abbott, E.V., Hughes, C.G. (Eds.), Sugarcane Diseases of the World, Vol. 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 79–107.

- Martinelli, F., Scalenghe, R., Davino, S., Panno, S., Scuderi, G., Ruisi, P., Villa, P., Stroppiana, D., Boschetti, M., Goulart, L.R., Cristina, E., Davis, C.E., Dandekar, A.M., 2015. Advanced methods of plant disease detection. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 35, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, F., Cao, Z., Zhang, S., Gan, Y., Cai, W., Peng, L., Wu, Y., Wang, W., Yang, B., 2024. Factors affecting the production of sugarcane yield and sucrose accumulation: suggested potential biological solutions. Front. Plant Sci. 15, 1374228. [CrossRef]

- Mensi, I., Girard, J.C., Pieretti, I., Larbre, F., Roumagnac, P., Royer, M., Rott, P., 2013. First report of sugarcane leaf scald in Gabon caused by a highly virulent and aggressive strain of Xanthomonas albilineans. Plant Dis. 97, 988. [CrossRef]

- Mensi, I., Vernerey, M.-S., Gargani, D., Nicole, M., Rott, P., 2014. Breaking dogmas: the plant vascular pathogen Xanthomonas albilineans is able to invade non-vascular tissues despite its reduced genome. Open Biol. 4, 130116. [CrossRef]

- Nagamine, K., Hase, T., Notomi, T., 2002. Accelerated reaction by loop-mediated isothermal amplification using loop primers. Mol. Cell. Probes 16, 223–229. [CrossRef]

- Ocenar, J., Arizala, D., Boluk, G., Dhakal, U., Gunarathne, S., Paudel, S., Dobhal, S., Arif, M., 2019. Development of a robust, field-deployable loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) assay for specific detection of potato pathogen Dickeya dianthicola targeting a unique genomic region. PLoS One 14, e0218868. [CrossRef]

- Ovalle, W., Comstock, J.C., Juarez, J., Soto, G., 1995. First report of leaf scald of sugarcane (Xanthomonas albilineans) in Guatemala. Plant Dis. 79, 212. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.B., Grisham, M., Burner, D., Legendre, B., Wei, Q., 1999. Development of polymerase chain reaction primers highly specific for Xanthomonas albilineans, the causal bacterium of sugarcane leaf scald disease. Plant Dis. 83, 218–222. [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.B., Grisham, M., Burner, D., 1997. A polymerase chain reaction protocol for the detection of Xanthomonas albilineans, the causal agent of sugarcane leaf scald disease. Plant Dis. 81, 189–194. [CrossRef]

- Pieretti, I., et al., 2009. The complete genome of Xanthomonas albilineans provides new insights into the reductive genome evolution of the xylem-limited Xanthomonadaceae. BMC Genomics 10, 616. [CrossRef]

- Pieretti, I., et al., 2012. Genomic insights into strategies used by Xanthomonas albilineans with its reduced artillery to spread within sugarcane xylem vessels. BMC Genomics 13, 658. [CrossRef]

- Pieretti, I., Pesic, A., Petras, D., Royer, M., Süssmuth, R.D., Cociancich, S., 2015b. What makes Xanthomonas albilineans unique amongst xanthomonads? Front. Plant Sci. 6, 289. [CrossRef]

- Piñón, D., Casas, M., Blanch, M.A., Fontaniella, B., Blanco, Y., Vicente, C., et al., 2002. Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus, a sugar cane endosymbiont, produces a bacteriocin against Xanthomonas albilineans, a sugar cane pathogen. Res. Microbiol. 153, 345–351. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R., Bhattacharyya, A., Nguyen, Q.D., 2017. Nanotechnology in sustainable agriculture: recent developments, challenges, and perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1014. [CrossRef]

- Prasannakumar, M., Parivallal, P.B., Pramesh, D., Mahesh, H.B., Raj, E., 2021. LAMP-based foldable microdevice platform for the rapid detection of Magnaporthe oryzae and Sarocladium oryzae in rice seed. Sci. Rep. 11, 178. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, A.H., Hopkins, D.L., 1996. Fastidious xylem-limited bacterial plant pathogens. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 34, 131–151. [CrossRef]

- Rački, N., Dreo, T., Gutierrez-Aguirre, I., Blejec, A., Ravnikar, M., 2014. Reverse transcriptase droplet digital PCR shows high resilience to PCR inhibitors from plant, soil and water samples. Plant Methods 10, 42. [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, A., Ali, W.R., Asif, M., Ahmed, N., Khan, W.S., Mansoor, S., Bajwa, S.Z., Amin, I., 2021. Development of a LAMP assay using a portable device for the real-time detection of cotton leaf curl disease in field conditions. Biol. Methods Protoc. 6, bpab010. [CrossRef]

- Ricaud, C., Ryan, C.C., 1989. Leaf scald. In: Ricaud, C., Egan, B.T., Gillaspie, A.G., Hughes, C.G. (Eds.), Diseases of Sugarcane: Major Diseases. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 39–58.

- Ricaud, C., Perombelon, M., 1964. Leaf scald. MSIRI Annu. Rep., Réduit, Mauritius, pp. 56–58.

- Rott, P., 1995. Leaf scald disease. In: Croft, B.J., Piggin, C.M., Wallis, E.S., Hogarth, D.M. (Eds.), Sugarcane Germplasm Conservation and Exchange. ACIAR Proceedings No. 67, Canberra, pp. 123–124.

- Rott, P., Arnaud, M., Baudin, P., 1986. Serological and lysotypical variability of Xanthomonas albilineans (Ashby) Dowson, causal agent of sugarcane leaf scald disease. J. Phytopathol. 116, 201–211. [CrossRef]

- Rott, P., Davis, M., 1995. Recent advances in research on variability of Xanthomonas albilineans, causal agent of sugarcane leaf scald disease. In: Proc. Int. Soc. Sugarcane Technol. Congr., Vol. 22, pp. 498–503.

- Rott, P., Davis, M.J., 2000. Leaf scald. In: Rott, P., Bailey, R.A., Comstock, J.C., Croft, B.J., Saumtally, A.S. (Eds.), A Guide to Sugarcane Diseases. CIRAD-ISSCT, Montpellier, France, pp. 38–44.

- Rott, P., Fleites, L., Marlow, G., Royer, M., Gabriel, D.W., 2011. Identification of new candidate pathogenicity factors in the xylem-invading pathogen Xanthomonas albilineans by transposon mutagenesis. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24, 594–605. [CrossRef]

- Rott, P., Soupa, D., Brunet, Y., Feldmann, P., Letourmy, P., 1995. Leaf scald (Xanthomonas albilineans) incidence and its effect on yield in seven sugarcane cultivars in Guadeloupe. Plant Pathol. 44, 1075–1084. [CrossRef]

- Sandhu, H.S., Rott, P., Comstock, J.C., Gilbert, R.A., 2013. Diseases in sugarcane. Sugarcane Handbook. Agronomy Department, UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida. Retrieved from: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/SC001.

- Saumtally, A., Dookun-Saumtally, A., Rao, G.P., Saumtally, A.S., Rott, P., 2004. Leaf scald of sugarcane: a disease of worldwide importance. In: Sugarcane Pathology: Bacterial and Nematode Diseases. New Hampshire: Science Publishers, pp. 65–76.

- Schori, M., Appel, M., Kitko, A., Showalter, A.M., 2013. Engineered DNA polymerase improves PCR results for plastid DNA. Appl. Plant Sci. 1, 1200519. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Zhao, J.Y., Zhou, J.R., Ntambo, M.S., Xu, P.Y., Rott, P.C., Gao, S.J., 2021. Molecular detection and quantification of Xanthomonas albilineans in juice from symptomless sugarcane stalks using a real-time quantitative PCR assay. Plant Dis. 105, 3451–3458. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.C., Lin, C.P., Chen, C.T., 1990. Characterization of Xanthomonas albilineans (Ashby) Dowson, the causal agent of sugarcane leaf scald disease. Plant Protect. Bull. 32, 125–135.

- Umer, M., Aziz, N.B., Al Jabri, S., Bhuiyan, S.A., Shiddiky, M.J., 2021. Naked eye evaluation and quantitative detection of the sugarcane leaf scald pathogen, Xanthomonas albilineans, in sugarcane xylem sap. Crop Pasture Sci. 72, 361–371. [CrossRef]

- Urashima, A.S., Zavaglia, A.C., 2012. Comparison of two diagnostic methods for leaf scald (Xanthomonas albilineans) of sugarcane. Summa Phytopathol. 38, 155–158. [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R., Padmanaban, P., 2008. Handbook on Sugarcane Diseases and their Management. Coimbatore: Sugarcane Breeding Institute.

- Viswanathan, R., Ramesh, S.A., 2004. Isolation and production of antiserum to Xanthomonas albilineans and diagnosis of the pathogen through serological techniques. J. Mycol. Plant Pathol. 34, 797–800.

- Viswanathan, R., Padmanaban, P., Mohanraj, D., Nallathambi, P., 1997. Occurrence of leaf scald disease in Tamil Nadu. Indian Phytopathol. 50, 149.

- Walker, D.I.T., 1987. Breeding for resistance. In: Heinz, J.D. (Ed.), Sugarcane Improvement through Breeding. Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam, pp. 445–502.

- Wang, H.B., Xiao, N.Y., Wang, Y.J., Guo, J.L., Zhang, J.S., 2020. Establishment of a qualitative PCR assay for the detection of Xanthomonas albilineans (Ashby) Dowson in sugarcane. Crop Prot. 130, 105053. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.K., Comstock, J.C., Hatziloukas, E., Schaad, N.W., 1999. Comparison of PCR, BIO-PCR, DIA, ELISA and isolation on semiselective medium for detection of Xanthomonas albilineans, the causal agent of leaf scald of sugarcane. Plant Pathol. 48, 245–252. [CrossRef]

- Wiehe, P.O., 1951. Leaf scald and chlorotic streak—two sugarcane diseases occurring in British Guiana. Lecture to Br. Guiana Sugar Prod. Ass.

- Zhang, L., Birch, R.G., 1996. Biocontrol of sugar cane leaf scald disease by an isolate of Pantoea dispersa which detoxifies albicidin phytotoxins. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 22, 132–136. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Y., Shan, H.L., Li, W.F., Cang, X.Y., Wang, X.Y., Yin, J., Luo, Z.M., Huang, Y.K., 2017. First report of sugarcane leaf scald caused by Xanthomonas albilineans in the province of Guangxi, China. Plant Dis. 101, 1541. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).