1. Introduction

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life-threatening disease, patients with ARDS usually need mechanical ventilation.

Treatment options for ARDS include low tidal volume ventilation, steroids, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and prone positioning [

1,

2]

. Prone positioning has been shown to recruit and stabilize dependent lung segments [

3]

, resulting in improving oxygenation and reducing mortality rates in moderate to severe ARDS cases. Current guidelines suggest a minimum duration of 16 hours for prone positioning therapy [

4].

Studies indicated that longer durations may confer greater benefits [

5,

6].

However, the optimal duration of prone positioning remains uncertain. In light of this, our study aims to compare the clinical outcomes associated with 16-hour versus 24-hour prone positioning sessions for patients diagnosed with moderate to severe ARDS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Enrollment

The study was conducted over a three-year period, spanning from July 2020 to July 2023, within the adult intensive care unit (ICU). Eligible participants were individuals aged 20 or above, diagnosed with moderate to severe ARDS and managed under protective lung ventilation protocols (tidal volume 4-8 ml/kg, plateau pressure ≤ 30 cmH2O, PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 150 mmHg, Positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) ≥ 5 cmH2O, FiO2 > 60%), and anticipated to survive for at least 24 hours. Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent abdominal surgery with an open abdominal wound, experienced massive hemoptysis, suffered from intracranial hemorrhage, were pregnant, or had spine or pelvic fractures. This prospective, randomized clinical study obtained approval from the human investigation and research committee of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (VGHKS19-CT11-14). Before enrolling the first patient, the study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04391387). This study performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. There are no conflicts of interest.

2.2. Randomization

After obtaining informed consent from the patients or their next of kin, participants were randomly assigned to one of two study groups using a software-generated randomization schedule. Randomization was allocated with 1:1 principle. Sequential numbers were put in sealed containers. Caregivers remained blinded to the randomization sequence. Upon assignment, arterial blood gas, serum lactate, and driving pressure measurements were taken. Residents and ICU nurses turn the subjects into the prone position after administering sedation and opioid therapy.

Following prone positioning, arterial blood gas, driving pressure, and serum lactate levels were assessed at the first hour, 8

th hour, 16

th hour and 24

th hour. These parameters were re-evaluated 8 hours after discontinuation of prone positioning. If patients achieved a PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio≥ 150 mmHg on FiO

2 ≤ 0.6 and PEEP ≤ 10 cmH

2O in the supine position, the next session of prone positioning therapy was discontinued [

7]. Conversely, if patients did not meet these criteria, the next session of prone positioning therapy was initiated, with subsequent arterial blood gas, driving pressure, and serum lactate checks.

Demographic data collected at randomization included primary ICU admission diagnosis, age, gender, body mass index (BMI), number of organ failures, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, serum lactate and arterial blood gas levels, days between ARDS onset and prone positioning, and pulmonary or extra-pulmonary causes of ARDS.

Furthermore, specific medications administered during the study period, such as steroids (methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone, dexamethasone, prednisolone), antibiotics, sedatives, muscle relaxants, and opioids, were recorded.

The protective lung strategy for ventilator settings entailed maintaining a tidal volume of 4-8 ml per predicted body weight, with plateau pressure kept ≤ 30 cmH

2O [

8].

2.3. Observations

Patients were monitored daily for the occurrence of pressure sores, endotracheal tube obstruction, tube dislodgement, ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), and the need for rescue use of ECMO. Monitoring of patients continued throughout the duration of prone position therapy, extending until the cessation of the final session.

2.4. Definitions

The diagnosis of ARDS follows the Berlin definition, which includes the following criteria [

9]:

Acute onset of infiltrates resulting from a known clinical insult or new/worsening respiratory symptoms within 7 days.

Bilateral opacity observed on chest imaging, not fully explained by effusions, lobar/lung collapse, or nodules.

Respiratory failure not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload.

Utilization of a minimum PEEP of at least 5 cmH2O.

The severity of ARDS is determined by the PaO2/FiO2 ratio: mild ARDS (200 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg), moderate ARDS (100 mmHg < PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 200 mmHg), and severe ARDS (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 100 mmHg).

Driving pressure is calculated as the difference between plateau pressure and PEEP, with plateau pressure defined as the pressure after the inspiratory pause.

A positive response to prone position therapy is indicated by an increase in the PaO2/FiO2 ratio of ≥20% following prone positioning. Mortality is defined as death at discharge.

Diagnosis of VAP required the agreement of two pulmonologists. All radiographs were reviewed independently by each pulmonologist, without knowledge of clinical details. The diagnosis followed a modified version of the criteria of The National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance (NNIS) system developed by the Centers for Disease Control [

10].

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcomes measured in this study were the changes in the PaO2/FiO2 ratio following each prone positioning session, variations in driving pressure and serum lactate levels. Secondary outcomes included the number of prone positioning sessions required, lengths of ICU and hospital stays, duration of mechanical ventilation, occurrences of pressure sores, tube dislodgement, endotracheal tube obstruction, incidents of ventilator-associated pneumonia, and mortality rates.表單的頂端

2.6. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 29.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). A comparison between the two treatment groups was conducted based on the intent-to-treat principle. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation, percentage, or median with interquartile ranges (IQRs). Student’s t-test was employed for comparing continuous variables with a normal distribution, while the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized for continuous variables with a non-normal distribution. Dichotomous variables were compared using either the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, depending on the expected frequency of occurrence. Differences in primary outcomes were analyzed using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc analysis with Bonferroni method. Difference of PaO2/FiO2 ratio change among different sessions of prone positioning was analyzed using two-way ANOVA. All p-values were two-tailed, and significance was considered at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

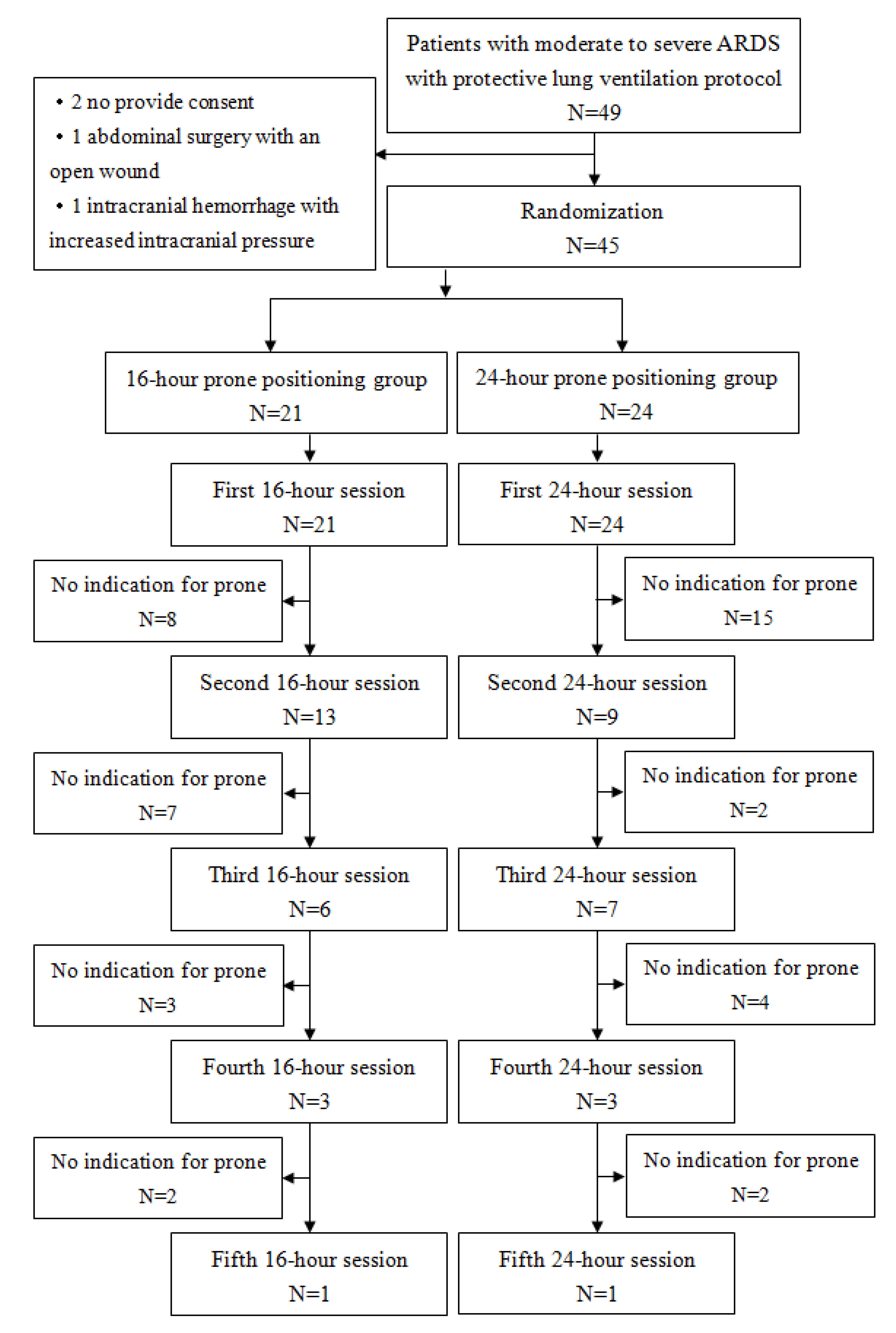

Forty-nine patients initially meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study. However, two patients did not provide consent, one had undergone abdominal surgery with an open wound, and another had intracranial hemorrhage with increased intracranial pressure. Consequently, 45 patients were included, with 21 receiving 16-hour prone position therapy and 24 receiving 24-hour therapy. The flow chart for all patients is presented in

Figure 1. All the patients completed study. The study ended when investigation and research expiration date reached. This study analyzed data with intent-to-treat principle.

At randomization, demographic characteristics such as gender, age, BMI, number of organ failures, APACHE II score, use of sedation, muscle relaxants, vasopressors, or steroids, time from ARDS onset to prone position therapy, pulmonary or extra-pulmonary cause of ARDS, and serum lactate levels were similar between the two groups (

Table 1).

No statistical differences were observed in respiratory parameters before the study period (

Table 2), indicating homogeneity between the two groups.

3.2. Primary Endpoints

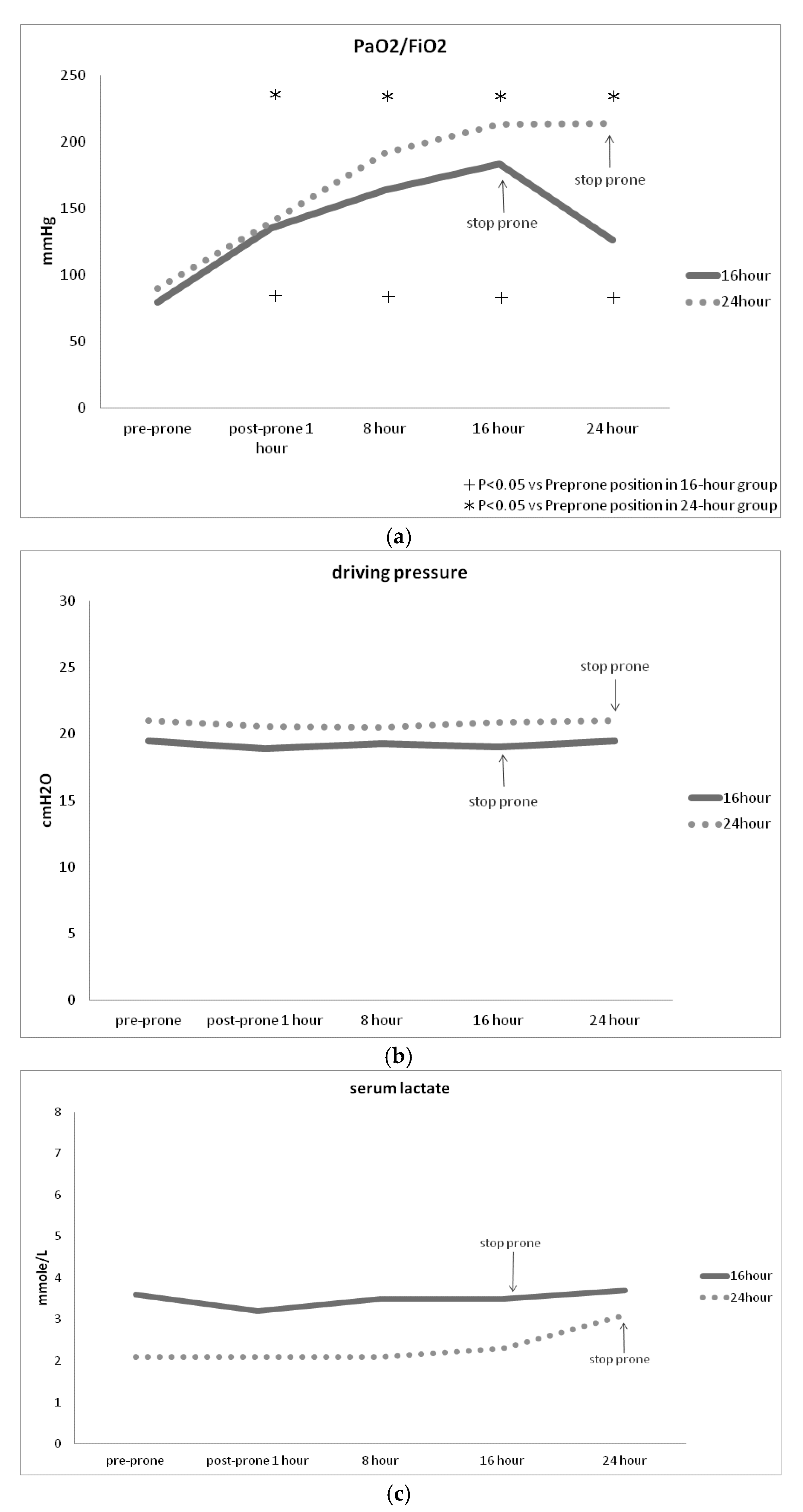

Both groups demonstrated a significant improvement in PaO

2/FiO

2 following prone position therapy (

Figure 2A), while there was no significant change in driving pressure (

Figure 2B) or serum lactate levels (

Figure 2C) during prone postioning. Notably, PaO

2/FiO

2 significantly increased within the first hour of prone positioning, but often decreased upon transitioning from prone to supine position (

Figure 2A). There were no significant differences of PaO

2/FiO

2 driving pressure or serum lactate levels between 16-hour group and 24 hour-group (

Figure 2 A,B,C).

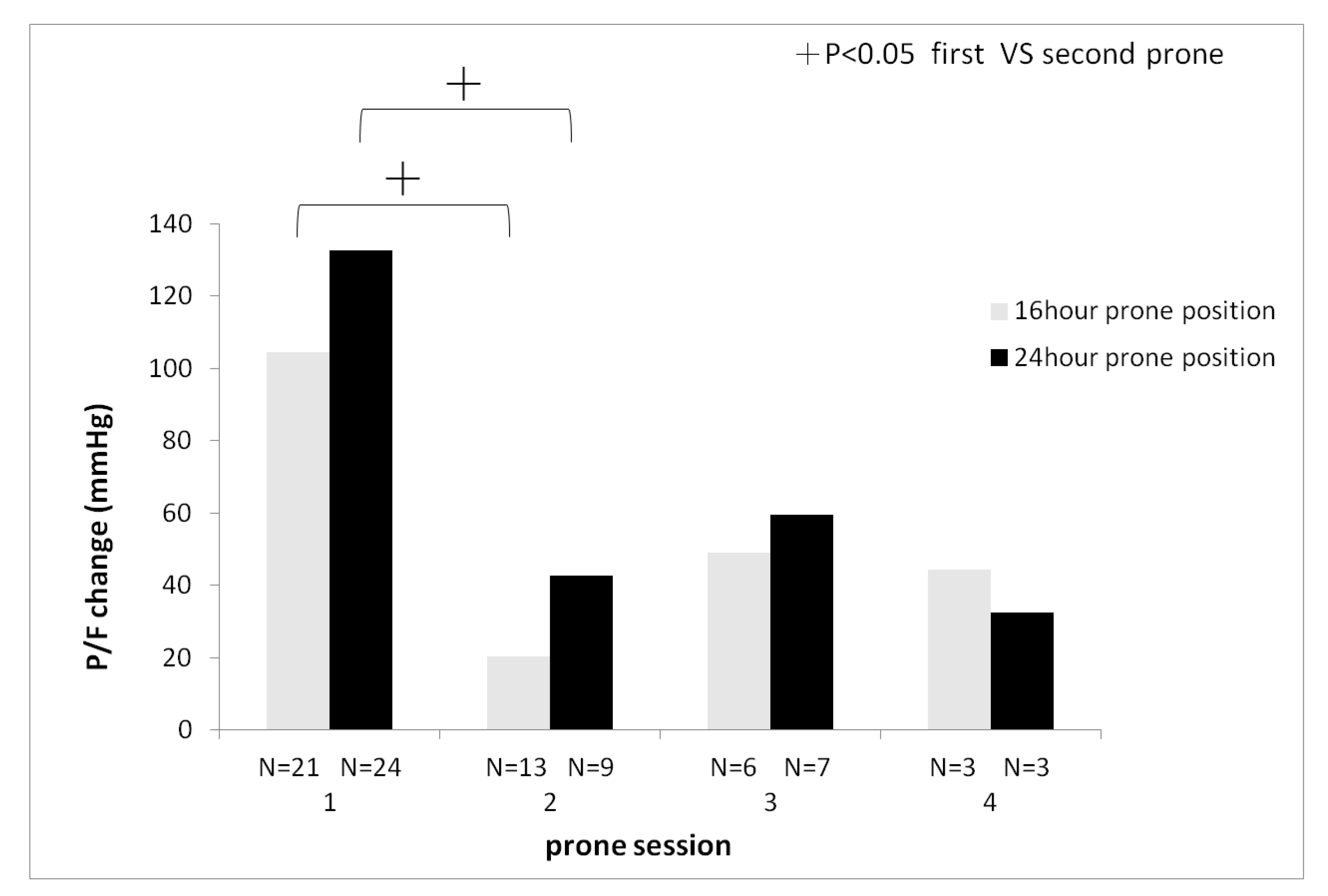

Additionally, a decreasing trend was observed in the change of PaO

2/FiO

2 between pre- and post-prone positioning. With subsequent sessions, there was a significantly higher change of PaO

2/FiO

2 ratio in the first session compared to the second session of prone positioning (24-hour group: first session 135

± 112.8 mmHg vs second session 42.6

± 50.5 mmHg,

P < 0.05, 16-hour group first session 104.4

± 84.9 mmHg vs second session 20.4

± 91.6 mmHg,

P < 0.05) (

Figure 3).

3.3. Secondary Clinical Outcomes

Secondary clinical outcomes, including the number of prone positioning sessions, changes in PaO

2/FiO

2 after discontinuation of prone positioning, incidence of tube dislodgement, endotracheal tube obstruction, pressure sores, ICU days, ventilator days, hospital days, and occurrences of VAP, are summarized in

Table 3. Patients undergoing 24-hour prone position therapy exhibited a tendency towards a lower rate of repeated prone positioning sessions compared to those receiving 16-hour therapy (37.5% vs. 61.9%, p=0.06) (

Table 3), although this difference did not reach statistical significance. No significant differences in complications such as pressure sores, tube dislodgement, endotracheal tube obstruction, or VAP were observed between the two groups. The mortality rate was not significantly different between the 16-hour group (57.1%) and the 24-hour group (54.2%), with both groups showing a high responder rate (95.2% vs. 95.8%). Additionally, there was no significant difference in the need for rescue ECMO use. The 30-day outcomes, including the length of ICU-free days, ventilator-free days, and survival while liberated from the ventilator, did not exhibit any significant differences (

Table 3).

4. Discussion

This study reveals that prone position therapy effectively enhances oxygenation for patients with moderate to severe ARDS in both 16-hour and 24-hour treatment groups. Early session of prone positioning has higher PaO2/FiO2 ratio improvement. However, it does not significantly improve driving pressure or serum lactate levels. Notably, the 24-hour duration of prone positioning demonstrates a tendency toward requiring fewer therapy sessions compared to the 16-hour duration.

In prior research, the increase in PaO

2 ranged from 23 to 78 mmHg, with PaO

2/FiO

2 improving by 21 to 161 mmHg [

11]. Our study shows a PaO

2/FiO

2 increase of 114.1 mmHg. The improvement results from a reduction in shunt and ventilation-perfusion heterogeneity that occurs because the lungs, which anatomically resemble a cone, fit into their cylinder-like thorax endosure with less distortion when patients are prone versus supine [

12,

13,

14,

15].

Driving pressure correlates with global lung strain [

16,

17] and is recognized as a risk factor for ARDS in mechanically ventilated patients [

18]. Reductions in driving pressure have been strongly linked to improved survival in ARDS cases [

16]. However, our study did not show reduced driving pressure significantly during prone positioning, one study found that driving pressure did not significantly change during prone positioning for ARDS patients [

19], which aligns with the findings of our study. Prone positioning exceeding 12 hours reduces mortality for patients with moderate to severe ARDS [

20], but it's not directly related to driving pressure.

While prone positioning significantly enhances oxygenation, it does not notably affect serum lactate levels. Lactate levels are influenced by various factors, including underlying diseases, medications, cellular metabolism, tissue perfusion, and regional areas of ischemia [

21]. A decrease in lactate levels reflects both improved microcirculation and increased lactate clearance, rather than solely increased oxygen delivery. Yoshida T et al. also reported that prone position did not significantly lower serum lactate levels (supine: 15 mg/dl vs prone: 13 mg/dl) [

22], consistent with our study.

Interestingly, the initial prone positioning session yields a significantly higher increase in PaO

2/FiO

2 compared to subsequent sessions. Prone position may be effective in improving oxygenation when initiated early (< 3 days) during the exudative phase, when congestive and compressive atelectasis are predominant features as opposed to the intermediate phase of ARDS (>1 week) [

23,

24].

The majority of observational studies report no improvement in partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO

2) [

11], similar to our findings. However, clinical outcomes tend to be more favorable when prone positioning results in a decreased PaCO

2 at the same minute ventilation [

25].

This study indicates that the 16-hour prone position group tends to undergo more repeated prone position therapy sessions. This trend arises from the observation that most patients who discontinued prone position therapy exhibited signs of worsening oxygenation, with their PaO2/FiO2 dropping below 150 mmHg, prompting the resumption of prone positioning therapy. In contrast, 24-hour prone position therapy demonstrates prolonged improvement in oxygenation. The longer duration of prone positioning confers the benefit of reducing the need for repeated therapy sessions, thereby decreasing clinical workload.

The response rate of prone position therapy is high up to 95.5% in this study. Lee DL et al showed that responders had a significantly shorter elapsed time from ARDS to prone position ventilation (8.4±2.9 vs 15.2±5.7 days, P<0.05), with a total response rate of 63.6% in that study [

26]. The average elapsed time from ARDS to the first prone position is one day in our study. L’Her E et al. conducted early prone position therapy during the first 24 hours and demonstrated that the response rate is 96% [

27], similar to our study.

Prone position therapy is associated with a higher incidence of pressure sores compared to the supine position, with age over 60 and a BMI above 28.4 being identified as risk factors for pressure sores [

28]. Additionally, endotracheal tube obstruction is another prevalent complication associated with prone positioning. Lee JM et al. demonstrated that prone positioning increased the risk of endotracheal tube obstruction by 2.16-fold (95% CI, 1.53-3.05, P < 0.001), based on a previous meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled studies [

29]. However, our study found no significant difference in complications between the 16-hour and 24-hour groups of patients, which is consistent with recent report by Page DB et al [

30].

This study has several limitations. The small sample size may limit the significance of some parameters. Additionally, being a single-center non-blinded randomized controlled study, further research involving multiple centers and nations is warranted.

5. Conclusions

Prone positioning ventilation significantly enhances oxygenation in patients with moderate to severe ARDS after just one hour of therapy. Early initiation of prone positioning yields better oxygenation improvement. The 24-hour prone positioning group tends to require fewer therapy sessions. Notably, there are no significant differences in oxygenation, driving pressure, serum lactate, mortality, or complications between the 16-hour and 24-hour groups.

Institutional Review Board Statements

the study was conducted in accordance with declaration of Helsinki and approved by the human investigation and research committee of Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital (VGHKS19-CT11-14).

Author Contributions

C. H.: Conceptualization, Methodology and Writing—original draft. S. L.: Investigation, Data curation. C. Y.: Investigation, Data curation. S. S.: Writing—review and editing. S. K.: Formal analysis. K. C.: Resources. All authors have read and agreed to publish version of manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, No. VGHKS109-084, KSVGH110-162, KSVGH111-199.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants include in this study.

Data Availability Statement

All the data are available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fan, E.; Del Sorbo, L.; Goligher, EC.; Hodgson, CL.; Munshi, L.; Walkey, AJ.; Adhikari, NJK.; Amato, MBP.;, Branson, R.; Brower, RG. ; et al. American Thoracic Society, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, and Society of Critical Care Medicine. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: Mechanical Ventilation in Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2017,195:1253-1263. [CrossRef]

- Meduri, GU.; Bridges, L.; Shih, MC.; Marik, PE.; Siemieniuk, RAC.; Kocak, M. Prolonged glucocorticoid treatment is associated with improved ARDS outcomes: analysis of individual patients' data from four randomized trials and trial-level meta-analysis of the updated literature. Intensive. Care. Med. 2016,42:829-840. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, AC. Conference on the scientific basis of respiratory therapy. Pulmonary physiotherapy in the pediatric age group. Comments of a devil's advocate. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1974,110:143-144. [CrossRef]

- Papazian, L.; Aubron, C.; Brochard, L.; Chiche, JD.; Combes, A.; Dreyfuss, D.; Guérin, C.; Jaber, S.; Mekontso-Dessap, A.; Mercat, A.; et al. Formal guideline: management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Ann. Intensive. Care. 2019,9:69. [CrossRef]

- Abroug, F.; Ouanes-Besbes, L.;Dachraoui, F.; Ouanes, I.;Brochard, L. An updated study-level meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials on proning in ARDS and acute lung injury. Crit. Care. 2011,15:R6. [CrossRef]

- McAuley, DF.; Giles, S.; Fichter, H.; Perkins, GD.; Gao, F. What is the optimal duration of ventilation in the prone position in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome?. Intensive. Care. Med. 2002,28:414-418. [CrossRef]

- Guerin, C.; Reignier, J.; Richard, JC.; Beuret, P.; Gacouin, A.; Boulain, T.; Mercier, E. Prone positioning in severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013,368:2159-2168. [CrossRef]

- Amato, MB.; Barbas, CS.; Medeiros, DM.; Magaldi, RB.; Schettino, GP.; Lorenzi-Filho, G.; Kairalla, RA.;, Deheinzelin, D.; Munoz, C.; Oliveira, R.; Takagaki, TY.; et al. Effect of a protective-ventilation strategy on mortality in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998,338:347-354. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, ND.; Fan, E.; Camporota, L.; Antonelli, M.; Anzueto, A.; Beale, R.; Brochard, L.; Brower, R.; Esteban, A.; Gattinoni, L.; et al. The Berlin definition of ARDS: an expanded rational, justification, and supplementary material. Intensive. Care. Med. 2012,38:1573-1582. [CrossRef]

- Miller, PR.; Johnson, JC 3rd.; Karchmer, T.; Hoth, JJ.; Meredith, JW.; Chang, MC. National Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System: From benchmark to bedside in trauma patients. J. Trauma. 2006,60:98-103. [CrossRef]

- Kallet, RH. A Comprehensive Review of Prone Position in ARDS. Respir. Care. 2015,60:1660-1687. [CrossRef]

- Lamm, WJ.; Graham, MM.; Albert, RK. Mechanism by which the prone position improves oxygenation in acute lung injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 1994,150:184-193. [CrossRef]

- Albert, RK.; Leasa, D.; Sanderson, M.; Robertson, HT.; Hlastala, MP. The prone position improves arterial oxygenation and reduces shunt in oleic-acid-induced acute lung injury. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1987,135:628-633. [CrossRef]

- Albert, RK.; Hubmayr, RD. The prone position eliminates compression of the lungs by the heart. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2000,161:1660-1665. [CrossRef]

- Malbouisson, LM.; Busch, CJ.; Puybasset, L.; Lu, Q.; Cluzel, P.; Rouby, JJ. Role of the heart in the loss of aeration characterizing lower lobes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. CT Scan ARDS Study Group. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2000,161:2005-2012. [CrossRef]

- Amato, MB.; Meade, MO.; Slutsky, AS.; Brochard, L.; Costa, EL.; Schoenfeld, DA.; Stewart, TE.; Briel, M.; Talmor, D.; Mercat, A.; et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015,372:747-755. [CrossRef]

- Ladha, K.; Vidal Melo, MF.; McLean, DJ.; Wanderer, JP.; Grabitz, SD.; Kurth, T.; Eikermann, M. Intraoperative protective mechanical ventilation and risk of postoperative respiratory complications: hospital based registry study. BMJ. 2015,351:h3646. [CrossRef]

- Roca, O.; Peñuelas, O.; Muriel, A.; García-de-Acilu, M.; Laborda, C.; Sacanell, J.; Riera, J.; Raymondos, K.; Du, B.; Thille, AW.; et al. Driving pressure is a risk factor for ARDS in mechanically ventilated subjects without ARDS. Respir. Care. 2021,66:1505-1513. [CrossRef]

- Riad, Z.; Mezidi, M.; Subtil, F.; Louis, B.; Guérin, C. Short-term effects of the prone positioning manoeuver on lung and chest wall mechanics in ARDS Patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2018,197:1355-1358. [CrossRef]

- Munshi, L.; Del Sorbo, L.; Adhikari, NKJ.; Hodgson, CL.; Wunsch, H.; Meade, MO.; Uleryk, E.; Mancebo, J.; Pesenti, A.; Ranier, VM.; et al. Prone Position for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017,14:S280-S288. [CrossRef]

- Kraut ,JA.; Madias, NE. Lactic acidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014,371:2309-2319. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Tanaka, A.; Roldan, R.; Quispe, R.; Taenaka, H.; Uchiyama, A.; Fujino, Y. Prone position reduces spontaneous inspiratory effort in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A bicenter study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care. Med. 2021,203:1437-1440. [CrossRef]

- Johannigman, JA.; Davis, K Jr.; Miller, SL.; Campbell, RS.; Luchette, FA.; Frame, SB.; Branson, RD. Prone positioning for acute respiratory distress syndrome in the surgical intensive care unit: Who when and how long? Surgery. 2000,128:708-716. [CrossRef]

- Blanch, L.; Mancebo, J.; Perez, M.; Martinez, M.; Mas, A.; Betbese, AJ.; Joseph, D.; BalluÂs, J.; Lucangelo, U. Short-term effects of prone position in critically ill patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive. Care. Med. 1997,23:1033-1039. [CrossRef]

- Gattinoni, L.; Vagginelli, F.; Carlesso, E.; Taccone, P.; Conte, V.; Chiumello, D.; Valenza, F.; Caironi, P.; Pesenti, A. Decrease in PaCO2 with prone position is predictive of improved outcome in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care. Med. 2003,31:2727-2733. [CrossRef]

- Lee, DL.; Chiang, HT.; Lin, SL.; Ger, LP.; Kun, MH.; Huang, YC. Prone position ventilation induces sustained improvement in oxygenation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome who have a large shunt. Crit. Care. Med. 2002,30:1446-1452. [CrossRef]

- L’Her, E.; Renault, A.; Oger, E.; Robaux, MA.; Boles, JM. A prospective survey of early 12-h prone positioning effects in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive. Care. Med. 2002,28:570-575. [CrossRef]

- Girard, R.; Baboi, L.; Ayzac, L.; Richard, J-C.; Guérin, C.; Group, PT. The impact of patient positioning on pressure ulcers in patients with severe ARDS: results from a multicentre randomised controlled trial on prone positioning. Intensive. Care. Med. 2014,40:397-403. [CrossRef]

- Lee, JM.; Bae, W.; Lee, YJ.; Cho, Y-J. The efficacy and safety of prone positional ventilation in acute respiratory distress syndrome: updated study-level meta-analysis of 11 randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care. Med. 2014,42:1252-1262. [CrossRef]

- Page, DB.; Russell, DW.; Gandotra, S.; Dransfield, MT. Prolonged prone position for COVID-19-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome: a randomized pilot clinical trial. Ann. Am. Thoracic. Soc. 2022,19:685-687. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).