Submitted:

22 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Nine Human-Specific Diseases Need Better-Defined Primary Pathogenicity

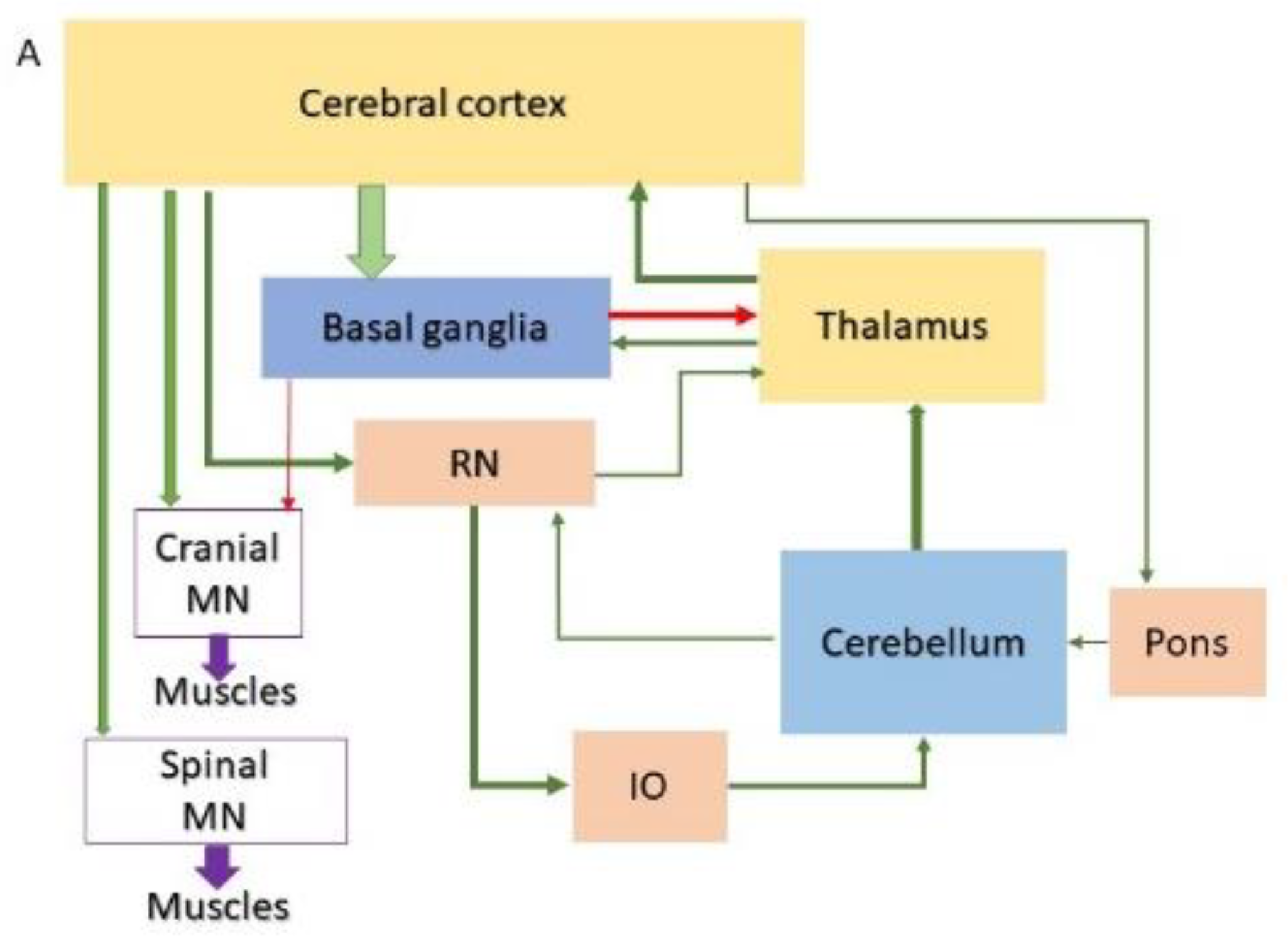

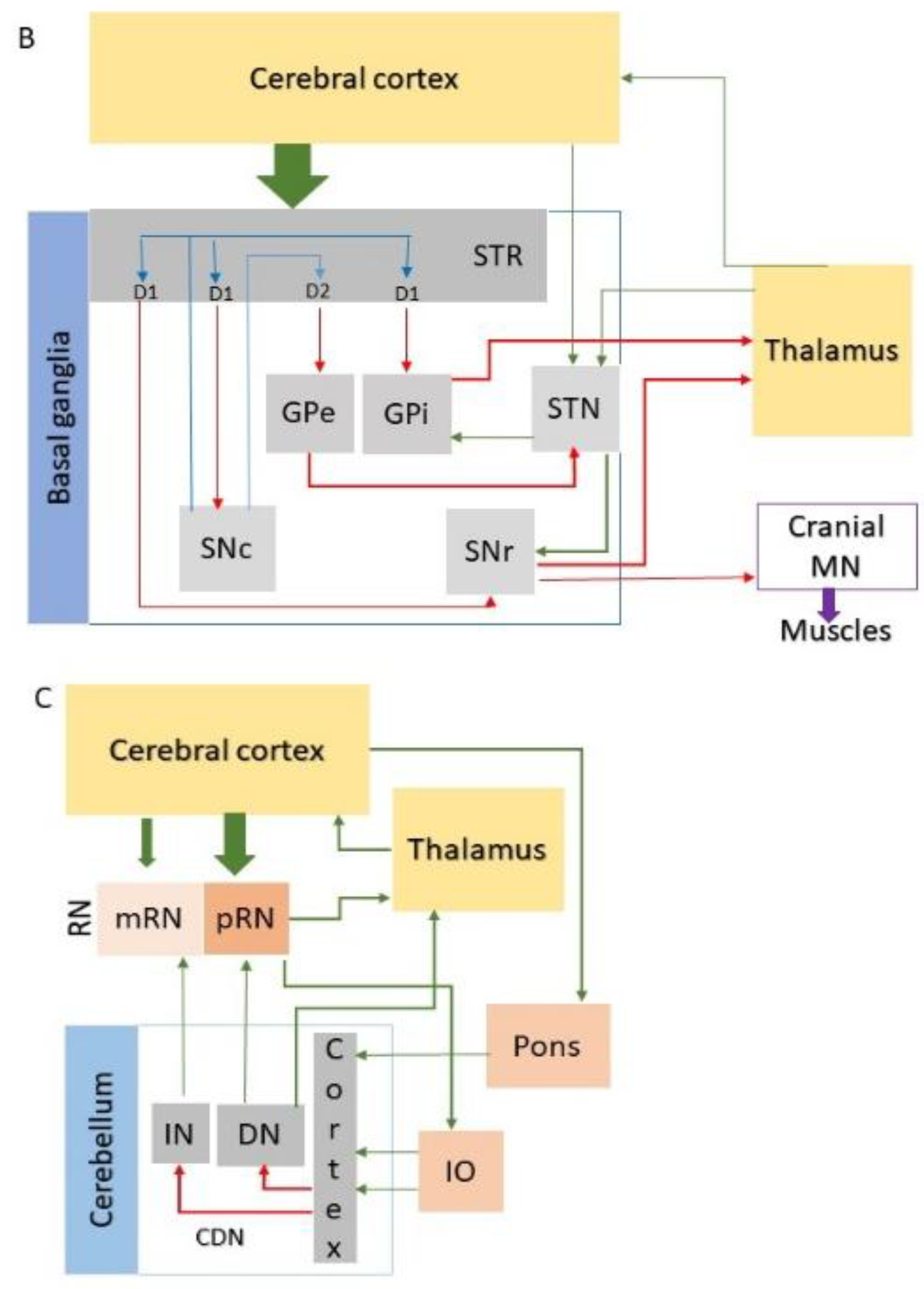

1.1. Dysfunctions and Degeneration of the Motor Coordination Network Stations

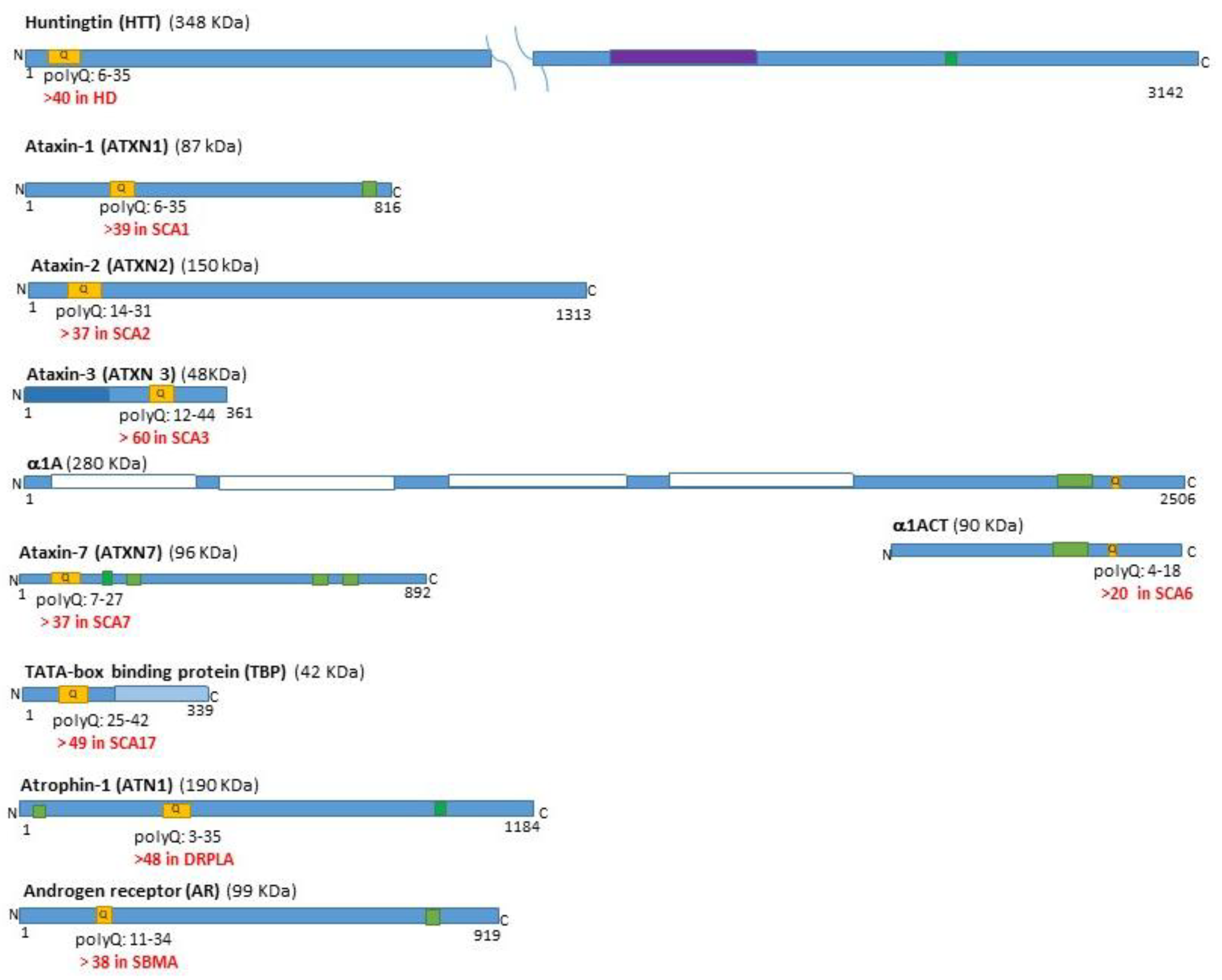

1.2. Expression and Dysfunction of the polyQ-Related Genes and Proteins

1.3. The Expansion of the Repeat Elongation is the New Challenge for the Primary Neuronal Pathogenesis

2. Approaches for Linking Neuronal-Type-Specific Vulnerability and Genetic Instability

2.1. The Neuronal Complexity, Excitability and Vulnerability to CAG Repeat Elongation in the Basal Ganglia.

2.2. The Neuronal Complexity, Excitability and Vulnerability to CAG Repeat Elongation in the Cerebellar Circuits

2.3. DNA Repair and Somatic Instability in Long-Projection Neurons Make the Motor Coordination Network

3. Conclusion and Outlook

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- La Spada AR, Taylor JP. Repeat expansion disease: progress and puzzles in disease pathogenesis. Nat Rev Genet. 2010, 11, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Spada AR, Taylor JP. Polyglutamines placed into context. Neuron. 2003, 38, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman AP, Shakkottai VG, Albin RL. Polyglutamine Repeats in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Annu Rev Pathol. 2019, 14, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoyas CA, La Spada AR. The CAG-polyglutamine repeat diseases: a clinical, molecular, genetic, and pathophysiologic nosology. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018, 147, 143–170. [Google Scholar]

- Paulson HL, Shakkottai VG, Clark HB, Orr HT. Polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias - from genes to potential treatments. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017, 18, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klockgether T, Mariotti C, Paulson HL. Spinocerebellar ataxia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019, 5, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüb U, Schöls L, Paulson H, Auburger G, Kermer P, Jen JC, et al. Clinical features, neurogenetics and neuropathology of the polyglutamine spinocerebellar ataxias type 1, 2, 3, 6 and 7. Prog Neurobiol. 2013, 104, 38–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson SL, Tsou WL, Prifti MV, Harris AL, Todi SV. A survey of protein interactions and posttranslational modifications that influence the polyglutamine diseases. Front Mol Neurosci. 2022, 15, 974167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLoughlin HS, Moore LR, Paulson HL. Pathogenesis of SCA3 and implications for other polyglutamine diseases. Neurobiol Dis. 2020, 134, 104635. [Google Scholar]

- Rüb U, Hoche F, Brunt ER, Heinsen H, Seidel K, Del Turco D, et al. Degeneration of the cerebellum in Huntington’s disease (HD): possible relevance for the clinical picture and potential gateway to pathological mechanisms of the disease process. Brain Pathol. 2013, 23, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijsen RAM, Toonen LJA, Gardiner SL, van Roon-Mom WMC. Genetics, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Progress in Polyglutamine Spinocerebellar Ataxias. Neurotherapeutics. 2019, 16, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cubo E, Martinez-Horta SI, Santalo FS, Descalls AM, Calvo S, Gil-Polo C, et al. Clinical manifestations of homozygote allele carriers in Huntington’s disease. Neurology. 2019, 92, e2101–e2108. [Google Scholar]

- Bostan AC, Strick PL. The basal ganglia and the cerebellum: nodes in an integrated network. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018, 19, 338–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewegen, HJ. The basal ganglia and motor control. Neural Plast. 2003, 10, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surmeier DJ, Graves SM, Shen W. Dopaminergic modulation of striatal networks in health and Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014, 29, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt Weisenhorn DM, Giesert F, Wurst W. Diversity matters - heterogeneity of dopaminergic neurons in the ventral mesencephalon and its relation to Parkinson’s Disease. J Neurochem. 2016, 139 (Suppl. S1), 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad AA, Wallén-Mackenzie Å. Architecture of the subthalamic nucleus. Commun Biol. 2024, 7, 78. [Google Scholar]

- De Zeeuw CI, Simpson JI, Hoogenraad CC, Galjart N, Koekkoek SK, Ruigrok TJ. Microcircuitry and function of the inferior olive. Trends Neurosci. 1998, 21, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen X, Du Y, Broussard GJ, Kislin M, Yuede CM, Zhang S, et al. Transcriptomic mapping uncovers Purkinje neuron plasticity driving learning. Nature. 2022, 605, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozareva V, Martin C, Osorno T, Rudolph S, Guo C, Vanderburg C, et al. A transcriptomic atlas of mouse cerebellar cortex comprehensively defines cell types. Nature. 2021, 598, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner A, Deng YP. Disrupted striatal neuron inputs and outputs in Huntington’s disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018, 24, 250–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacho M, Häusler AN, Brandstetter A, Iannilli F, Mohlberg H, Schiffer C, et al. Phylogenetic reduction of the magnocellular red nucleus in primates and inter-subject variability in humans. Front Neuroanat. 2024, 18, 1331305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landwehrmeyer GB, McNeil SM, Dure LS, Ge P, Aizawa H, Huang Q, et al. Huntington’s disease gene: regional and cellular expression in the brain of normal and affected individuals. Ann Neurol. 1995, 37, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusilli C, Migliore S, Mazza T, Consoli F, De Luca A, Barbagallo G, et al. Biological and clinical manifestations of juvenile Huntington’s disease: a retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 986–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latimer CS, Flanagan ME, Cimino PJ, Jayadev S, Davis M, Hoffer ZS, et al. Neuropathological Comparison of Adult Onset and Juvenile Huntington’s Disease with Cerebellar Atrophy: A Report of a Father and Son. J Huntingtons Dis. 2017, 6, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedjoudje A, Nicolas G, Goldenberg A, Vanhulle C, Dumant-Forrest C, Deverrière G, et al. Morphological features in juvenile Huntington disease associated with cerebellar atrophy - magnetic resonance imaging morphometric analysis. Pediatr Radiol. 2018, 48, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakazume S, Yoshinari S, Oguma E, Utsuno E, Ishii T, Narumi Y, et al. A patient with early onset Huntington disease and severe cerebellar atrophy. A patient with early onset Huntington disease and severe cerebellar atrophy. Am J Med Genet A. 2009, 149A, 598–601. [Google Scholar]

- Nance MA, Myers RH. Juvenile onset Huntington’s disease--clinical and research perspectives. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2001, 7, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan M, Scott C, Hof PR, Ansorge O. Betz cells of the primary motor cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2024, 532, e25567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babovic-Vuksanovic D, Snow K, Patterson MC, Michels VV. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA 2) in an infant with extreme CAG repeat expansion. Am J Med Genet. 1998, 79, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciorkowski AR, Shafrir Y, Hrivnak J, Patterson MC, Tennison MB, Clark HB, et al. Massive expansion of SCA2 with autonomic dysfunction, retinitis pigmentosa, and infantile spasms. Neurology. 2011, 77, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramocki MB, Chapieski L, McDonald RO, Fernandez F, Malphrus AD. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 presenting with cognitive regression in childhood. J Child Neurol. 2008, 23, 999–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donis KC, Saute JA, Krum-Santos AC, Furtado GV, Mattos EP, Saraiva-Pereira ML, et al. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 3/Machado-Joseph disease starting before adolescence. Neurogenetics. 2016, 17, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa K, Tanaka H, Saito M, Ohkoshi N, Fujita T, Yoshizawa K, et al. Japanese families with autosomal dominant pure cerebellar ataxia map to chromosome 19p13.1-p13.2 and are strongly associated with mild CAG expansions in the spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 gene in chromosome 19p13.1. Am J Hum Genet. 1997, 61, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Wang H, Xia Y, Jiang H, Shen L, Wang S, et al. A neuropathological study at autopsy of early onset spinocerebellar ataxia 6. J Clin Neurosci. 2010, 17, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansorge O, Giunti P, Michalik A, Van Broeckhoven C, Harding B, Wood N, et al. Ataxin-7 aggregation and ubiquitination in infantile SCA7 with 180 CAG repeats. Ann Neurol. 2004, 56, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donis KC, Mattos EP, Silva AA, Furtado GV, Saraiva-Pereira ML, Jardim LB, et al. Infantile spinocerebellar ataxia type 7: Case report and a review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2015, 354, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton LC, Frosch MP, Vangel MG, Weigel-DiFranco C, Berson EL, Schmahmann JD. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 7: clinical course, phenotype-genotype correlations, and neuropathology. Cerebellum. 2013, 12, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson J, Forsgren L, Sandgren O, Brice A, Holmgren G, Holmberg M. Expanded CAG repeats in Swedish spinocerebellar ataxia type 7 (SCA7) patients: effect of CAG repeat length on the clinical manifestation. Hum Mol Genet. 1998, 7, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyoshima Y, Takahashi H. Spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 17 (SCA17). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018, 1049, 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak B, Kozlowska E, Pawlik W, Fiszer A. Atrophin-1 Function and Dysfunction in Dentatorubral-Pallidoluysian Atrophy. Mov Disord. 2023, 38, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda S, Takahashi H. Neuropathology of dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy. Neuropathology; 1996. p. 48-55.

- Breza M, Koutsis G. Kennedy’s disease (spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy): a clinically oriented review of a rare disease. J Neurol. 2019, 266, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echaniz-Laguna A, Rousso E, Anheim M, Cossée M, Tranchant C. A family with early-onset and rapidly progressive X-linked spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy. Neurology. 2005, 64, 1458–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grunseich C, Kats IR, Bott LC, Rinaldi C, Kokkinis A, Fox D, et al. Early onset and novel features in a spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy patient with a 68 CAG repeat. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014, 24, 978–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saudou F, Humbert S. The Biology of Huntingtin. Neuron; 2016. p. P910-26.

- Gerbich TM, Gladfelter AS. Moving beyond disease to function: Physiological roles for polyglutamine-rich sequences in cell decisions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2021, 69, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee J, Kim M, Itoh TQ, Lim C. Ataxin-2: A versatile posttranscriptional regulator and its implication in neural function. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2018, 9, e1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäuerlein FJB, Saha I, Mishra A, Kalemanov M, Martínez-Sánchez A, Klein R, et al. In Situ Architecture and Cellular Interactions of PolyQ Inclusions. Cell. 2017, 171, 179–187.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa A, Ikeuchi T, Koike R, Matsubara N, Tsuchiya M, Nozaki H, et al. Long-term disability and prognosis in dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy: a correlation with CAG repeat length. Mov Disord. 2010, 25, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulson HL, Perez MK, Trottier Y, Trojanowski JQ, Subramony SH, Das SS, et al. Intranuclear inclusions of expanded polyglutamine protein in spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Neuron. 1997, 19, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo FA, Carvalho LR, Grinberg LT, Farfel JM, Ferretti RE, Leite RE, et al. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J Comp Neurol. 2009, 513, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent R, Azevedo FA, Andrade-Moraes CH, Pinto AV. How many neurons do you have? Some dogmas of quantitative neuroscience under revision. Eur J Neurosci. 2012, 35, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figiel M, Szlachcic WJ, Switonski PM, Gabka A, Krzyzosiak WJ. Mouse models of polyglutamine diseases: review and data table. Part I. Mol Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 393–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Switonski PM, Szlachcic WJ, Gabka A, Krzyzosiak WJ, Figiel M. Mouse models of polyglutamine diseases in therapeutic approaches: review and data table. Part II. Mol Neurobiol. 2012, 46, 430–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabrizi SJ, Ghosh R, Leavitt BR. Huntingtin Lowering Strategies for Disease Modification in Huntington’s Disease. Neuron. 2019, 101, 801–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadman, M. S: drug for Huntington disease fails in major trial, 2021.

- gusella@helix. mgh.harvard.edu GMoHsDG-HCEa, Consortium GMoHsDG-H. CAG Repeat Not Polyglutamine Length Determines Timing of Huntington’s Disease Onset. Cell. 2019, 178, 887–900.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusella JF, Lee JM, MacDonald ME. Huntington’s disease: nearly four decades of human molecular genetics. Hum Mol Genet. 2021, 30, R254–R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezenas du Montcel S, Durr A, Bauer P, Figueroa KP, Ichikawa Y, Brussino A, et al. Modulation of the age at onset in spinocerebellar ataxia by CAG tracts in various genes. Modulation of the age at onset in spinocerebellar ataxia by CAG tracts in various genes. Brain. 2014, 137 Pt 9, 2444–55. [Google Scholar]

- Handsaker RE, Kashin S, Reed NM, Tan S, Lee WS, McDonald TM, et al. Long somatic DNA-repeat expansion drives neurodegeneration in Huntington’s disease. Cell. 2025, 188, 623–639.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siletti K, Hodge R, Mossi Albiach A, Lee KW, Ding SL, Hu L, et al. Transcriptomic diversity of cell types across the adult human brain. Science. 2023, 382, eadd7046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apsley EJ, Becker EBE. Purkinje Cell Patterning-Insights from Single-Cell Sequencing. Cells.

- Gritton HJ, Howe WM, Romano MF, DiFeliceantonio AG, Kramer MA, Saligrama V, et al. Unique contributions of parvalbumin and cholinergic interneurons in organizing striatal networks during movement. Nat Neurosci. 2019, 22, 586–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenstock S, Dudanova I. Cortical and Striatal Circuits in Huntington’s Disease. Front Neurosci. 2020, 14, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011, 34, 441–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkin JL, Goldberg JA. Thinking Outside the Box (and Arrow): Current Themes in Striatal Dysfunction in Movement Disorders. Neuroscientist. 2019, 25, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan JW, Abercrombie ED. Relationship between subthalamic nucleus neuronal activity and electrocorticogram is altered in the R6/2 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. J Physiol. 2015, 593, 3727–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan JW, Abercrombie ED. Age-dependent alterations in the cortical entrainment of subthalamic nucleus neurons in the YAC128 mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2015, 78, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra HG, Byam CE, Lande JD, Tousey SK, Zoghbi HY, Orr HT. Gene profiling links SCA1 pathophysiology to glutamate signaling in Purkinje cells of transgenic mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2004, 13, 2535–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower MD, Tabrizi SJ. The breaking point where repeat expansion triggers neuronal collapse in Huntington’s disease. Cell Genom. 2025, 5, 100816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer RR, Pluciennik A. DNA Mismatch Repair and its Role in Huntington’s Disease. J Huntingtons Dis. 2021, 10, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telenius H, Kremer B, Goldberg YP, Theilmann J, Andrew SE, Zeisler J, et al. Somatic and gonadal mosaicism of the Huntington disease gene CAG repeat in brain and sperm. Nat Genet. 1994, 6, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik I, Kelley CP, Wang ET, Todd PK. Molecular mechanisms underlying nucleotide repeat expansion disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 589–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting EL, Hamilton J, Tabrizi SJ. Polyglutamine diseases. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2022, 72, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy L, Evans E, Chen CM, Craven L, Detloff PJ, Ennis M, et al. Dramatic tissue-specific mutation length increases are an early molecular event in Huntington disease pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2003, 12, 3359–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mätlik K, Baffuto M, Kus L, Deshmukh AL, Davis DA, Paul MR, et al. Cell Type Specific CAG Repeat Expansions and Toxicity of Mutant Huntingtin in Human Striatum and Cerebellum. Cell Type Specific CAG Repeat Expansions and Toxicity of Mutant Huntingtin in Human Striatum and Cerebellum. bioRxiv. 2023.

- Pressl C, Mätlik K, Kus L, Darnell P, Luo JD, Paul MR, et al. Selective vulnerability of layer 5a corticostriatal neurons in Huntington’s disease. Neuron. 2024, 112, 924–941.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao R, Matsuura T, Coolbaugh M, Zühlke C, Nakamura K, Rasmussen A, et al. Instability of expanded CAG/CAA repeats in spinocerebellar ataxia type 17. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008, 16, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium GMoHsDG-H. Identification of Genetic Factors that Modify Clinical Onset of Huntington’s Disease. Cell. 2015, 162, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaiya S, Cortes-Gutierrez M, Herb BR, Coffey SR, Legg SRW, Cantle JP, et al. Single-Nucleus RNA-Seq Reveals Dysregulation of Striatal Cell Identity Due to Huntington’s Disease Mutations. J Neurosci. 2021, 41, 5534–5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Bains MK, Mehrabi NF, Sehji T, Austria MDR, Tan AYS, Tippett LJ, et al. Cerebellar degeneration correlates with motor symptoms in Huntington disease. Ann Neurol. 2019, 85, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacher R, Lejeune FX, David I, Boluda S, Coarelli G, Leclere-Turbant S, et al. CAG repeat mosaicism is gene-specific in spinocerebellar ataxias. Am J Hum Genet. 2024, 111, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong SS, McCall AE, Cota J, Subramony SH, Orr HT, Hughes MR, et al. Gametic and somatic tissue-specific heterogeneity of the expanded SCA1 CAG repeat in spinocerebellar ataxia type 1. Nat Genet. 1995, 10, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zühlke C, Dalski A, Hellenbroich Y, Bubel S, Schwinger E, Bürk K. Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 (SCA1): phenotype-genotype correlation studies in intermediate alleles. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002, 10, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashida H, Goto J, Suzuki T, Jeong S, Masuda N, Ooie T, et al. Single cell analysis of CAG repeat in brains of dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy (DRPLA). J Neurol Sci. 2001, 190, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elam JS, Glasser MF, Harms MP, Sotiropoulos SN, Andersson JLR, Burgess GC, et al. The Human Connectome Project: A retrospective. Neuroimage. 2021, 244, 118543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley K, Shirley TL, Flaherty L, Messer A. Msh2 deficiency prevents in vivo somatic instability of the CAG repeat in Huntington disease transgenic mice. Nat Genet. 1999, 23, 471–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phadte AS, Bhatia M, Ebert H, Abdullah H, Elrazaq EA, Komolov KE, et al. FAN1 removes triplet repeat extrusions via a PCNA- and RFC-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023, 120, e2302103120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto RM, Dragileva E, Kirby A, Lloret A, Lopez E, St Claire J, et al. Mismatch repair genes Mlh1 and Mlh3 modify CAG instability in Huntington’s disease mice: genome-wide and candidate approaches. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003930. [Google Scholar]

| Disease | Forebrain | Midbrain | Hindbrain | SC | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX | TH |

R | Basal ganglia | RN | CN | Pons | Cerebellum | MO | MN | WM | |||||||

| STR | PL | STN | SN | PN | CN | CBC | CDN | IO | CN | ||||||||

| HD | |||||||||||||||||

| SCA1 | |||||||||||||||||

| SCA2 | |||||||||||||||||

| SCA3 | |||||||||||||||||

| SCA6 | |||||||||||||||||

| SCA7 | |||||||||||||||||

| SCA17 | |||||||||||||||||

| DRPLA | |||||||||||||||||

| SBMA | |||||||||||||||||

| Genes | Brain | CNS regions | Neural cell types | H | K | B | Ms | S | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | BG | R | TH | MB | CB | P | MO | SC | N | A | O | M | ||||||||

| HTT | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ATXN1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ATXN2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ATXN3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CACNA1A | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ATXN7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| TBP | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ATN1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| AR | ||||||||||||||||||||

| PolyQ disease | PolyQ protein | GOF | RBP sequestration | LOF | Nuclear inclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | HTT | + | + | nd | + |

| SCA1 | ATXN1 | + | nd | + | + |

| SCA2 | ATXN2 | + | + | + | + |

| SCA3 | ATXN3 | + | + | nd | + |

| SCA6 | 1ACT | + | nd | nd | + |

| SCA7 | ATXN7 | + | nd | nd | + |

| SCA17 | TBP | + | nd | nd | + |

| DRPLA | ATN1 | + | + | nd | + |

| SBMA | AR | + | nd | + | + |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).