Submitted:

23 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Materials

Animal Tissue Collection

Enzymatic Preparations

Glucuronidation Assays

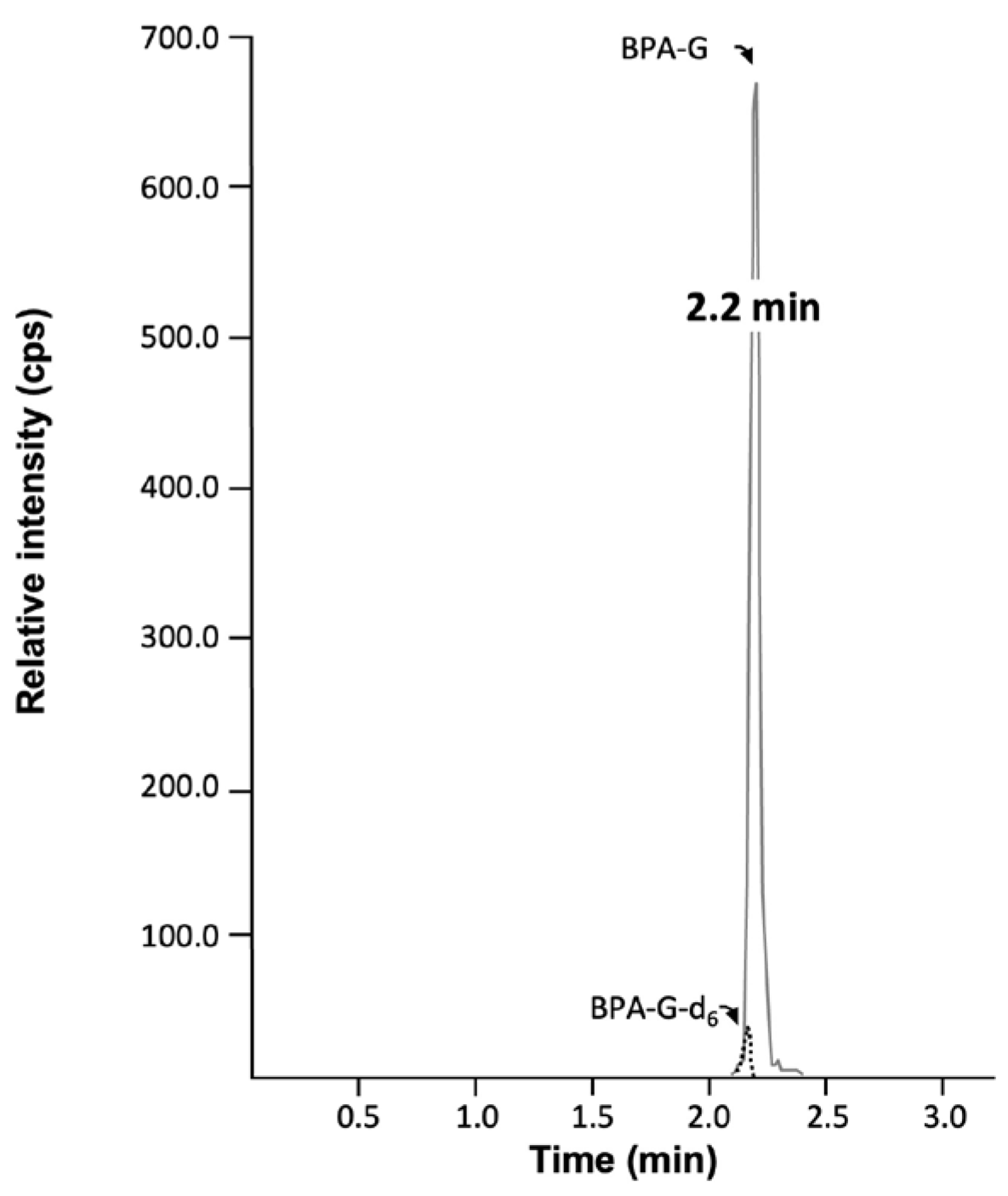

Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Total RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR Analyses

Results

Tissue Distribution of Bisphenol A-Glucuronide Formation in Mice

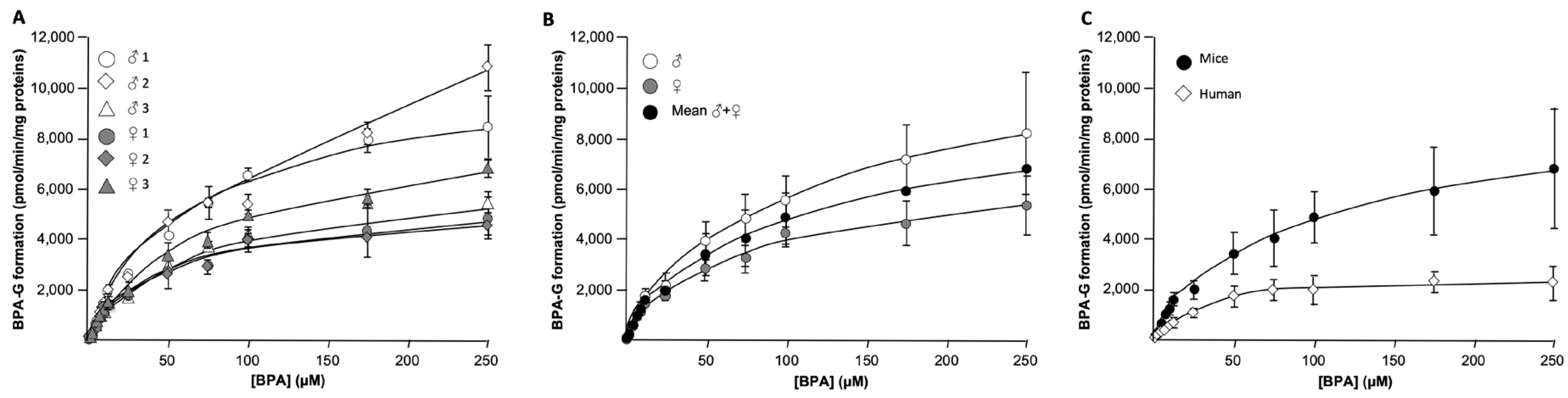

Kinetic Parameters of Hepatic BPA Glucuronidation in Mice and Humans

Kinetic Parameters of Intestinal and Biliary BPA-G Formation in Mice

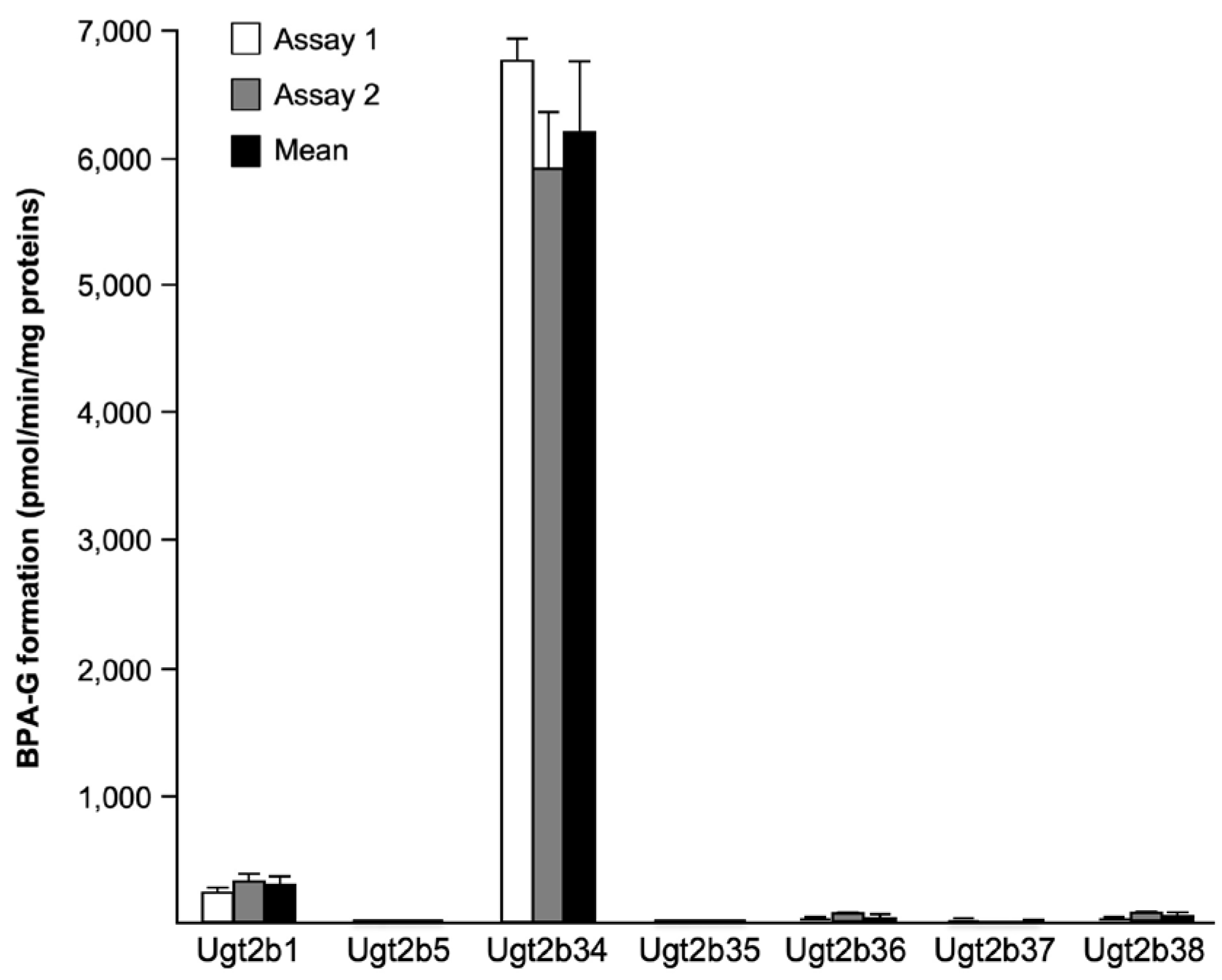

Identification of BPA-Conjugating Ugt2b enzymes in Mice

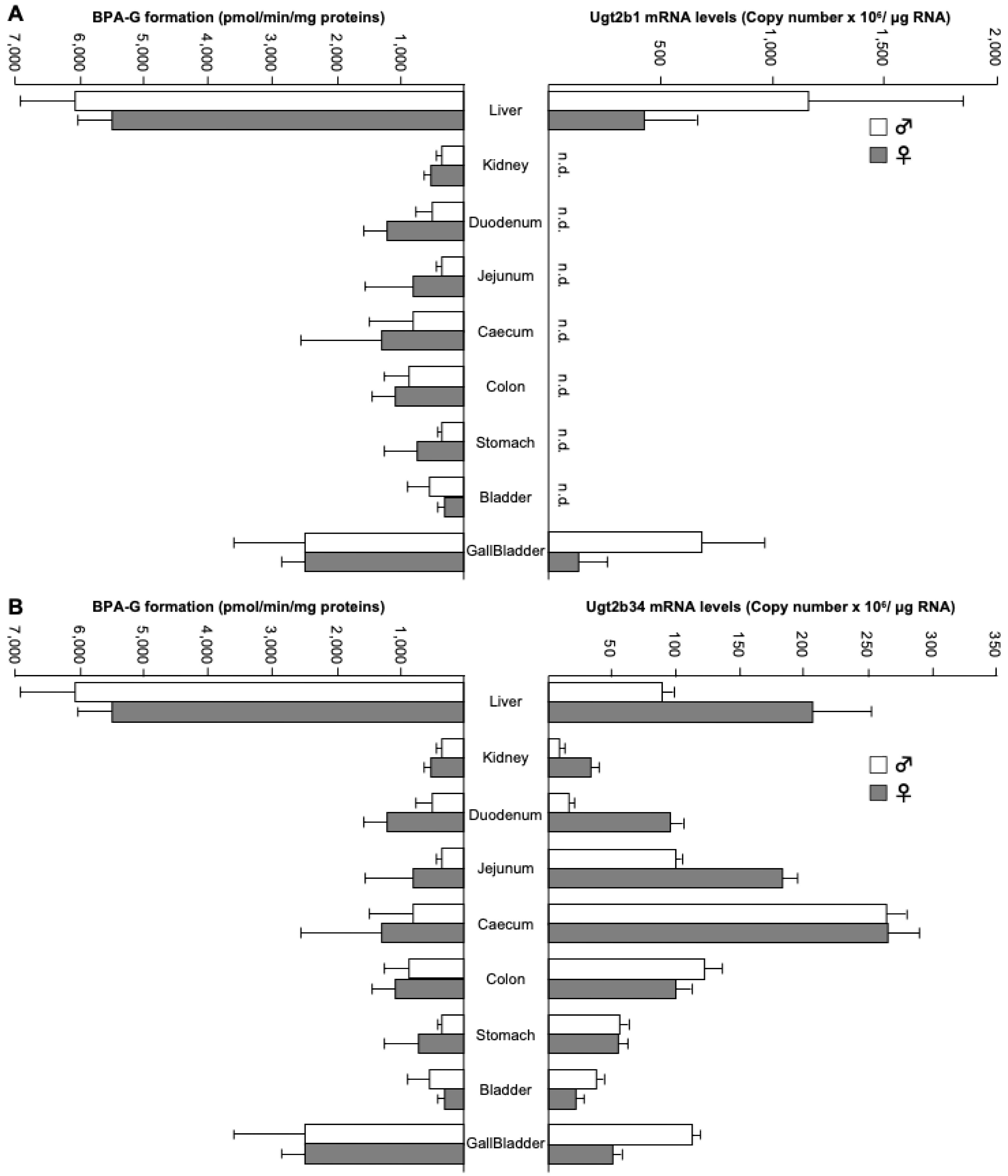

The Profile of Ugt2b34 mRNA Expression Correlates with BPA-G Formation

Discussion

Acknowledgment

Abbreviations

References

- Doerge, D.R.; Twaddle, N.C.; Vanlandingham, M.; Fisher, J.W. Pharmacokinetics of bisphenol A in neonatal and adult CD-1 mice: inter-species comparisons with Sprague-Dawley rats and rhesus monkeys. Toxicology letters 2011, 207, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, B.S. Bisphenol A: an endocrine disruptor with widespread exposure and multiple effects. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology 2011, 127, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calafat, A.M.; Ye, X.; Wong, L.Y.; Reidy, J.A.; Needham, L.L. Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003-2004. Environmental health perspectives 2008, 116, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerge, D.R.; Twaddle, N.C.; Vanlandingham, M.; Brown, R.P.; Fisher, J.W. Distribution of bisphenol A into tissues of adult, neonatal, and fetal Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2011, 255, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, I.A.; Galloway, T.S.; Scarlett, A.; Henley, W.E.; Depledge, M.; Wallace, R.B.; Melzer, D. Association of urinary bisphenol A concentration with medical disorders and laboratory abnormalities in adults. Jama 2008, 300, 1303–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, D.; Rice, N.E.; Lewis, C.; Henley, W.E.; Galloway, T.S. Association of urinary bisphenol a concentration with heart disease: evidence from NHANES 2003/06. PloS one 2010, 5, e8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura-Ogasawara, M.; Ozaki, Y.; Sonta, S.; Makino, T.; Suzumori, K. Exposure to bisphenol A is associated with recurrent miscarriage. Human reproduction 2005, 20, 2325–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantonwine, D.; Meeker, J.D.; Hu, H.; Sanchez, B.N.; Lamadrid-Figueroa, H.; Mercado-Garcia, A.; Fortenberry, G.Z.; Calafat, A.M.; Tellez-Rojo, M.M. Bisphenol a exposure in Mexico City and risk of prematurity: a pilot nested case control study. Environmental health : a global access science source 2010, 9, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.J.; Hong, Y.C.; Oh, S.Y.; Park, M.S.; Kim, H.; Leem, J.H.; Ha, E.H. Bisphenol A exposure is associated with oxidative stress and inflammation in postmenopausal women. Environmental research 2009, 109, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottenger, L.H.; Domoradzki, J.Y.; Markham, D.A.; Hansen, S.C.; Cagen, S.Z.; Waechter, J.M., Jr. The relative bioavailability and metabolism of bisphenol A in rats is dependent upon the route of administration. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 2000, 54, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurebayashi, H.; Harada, R.; Stewart, R.K.; Numata, H.; Ohno, Y. Disposition of a low dose of bisphenol a in male and female cynomolgus monkeys. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 2002, 68, 32–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchett, J.J.; Kuester, R.K.; Sipes, I.G. Metabolism of bisphenol a in primary cultured hepatocytes from mice, rats, and humans. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2002, 30, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkel, W.; Colnot, T.; Csanady, G.A.; Filser, J.G.; Dekant, W. Metabolism and kinetics of bisphenol a in humans at low doses following oral administration. Chemical research in toxicology 2002, 15, 1281–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuester, R.K.; Sipes, I.G. Prediction of metabolic clearance of bisphenol A (4,4 '-dihydroxy-2,2-diphenylpropane) using cryopreserved human hepatocytes. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2007, 35, 1910–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsberg, G.; Rice, D.C. Does rapid metabolism ensure negligible risk from bisphenol A? Environmental health perspectives 2009, 117, 1639–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, P.I.; Walter Bock, K.; Burchell, B.; Guillemette, C.; Ikushiro, S.; Iyanagi, T.; Miners, J.O.; Owens, I.S.; Nebert, D.W. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2005, 15, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillemette, C.; Levesque, E.; Harvey, M.; Bellemare, J.; Menard, V. UGT genomic diversity: beyond gene duplication. Drug Metab Rev 2010, 42, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knights, K.M.; Miners, J.O. Renal UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and the glucuronidation of xenobiotics and endogenous mediators. Drug metabolism reviews 2010, 42, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanioka, N.; Naito, T.; Narimatsu, S. Human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms involved in bisphenol A glucuronidation. Chemosphere 2008, 74, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanioka, N.; Oka, H.; Nagaoka, K.; Ikushiro, S.; Narimatsu, S. Effect of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B15 polymorphism on bisphenol A glucuronidation. Archives of toxicology 2011, 85, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokota, H.; Iwano, H.; Endo, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Inoue, H.; Ikushiro, S.; Yuasa, A. Glucuronidation of the environmental oestrogen bisphenol A by an isoform of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase, UGT2B1, in the rat liver. Biochem J 1999, 340 ( Pt 2) Pt 2, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, P.I.; Bock, K.W.; Burchell, B.; Guillemette, C.; Ikushiro, S.; Iyanagi, T.; Miners, J.O.; Owens, I.S.; Nebert, D.W. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2005, 15, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, P.; Trottier, J.; Verreault, M.; Bélanger, J.; Kaeding, J.; Barbier, O. Enzymatic Production of Bile Acid Glucuronides Used as Analytical Standards for Liquid Chromatography−Mass Spectrometry Analyses. Mol Pharm 2006, 3, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trottier, J.; Verreault, M.; Grepper, S.; Monté, D.; Bélanger, J.; Kaeding, J.; Caron, P.; Inaba, T.T.; Barbier, O. Human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A3 enzyme conjugates chenodeoxycholic acid in the liver. Hepatology 2006, 44, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbier, O.; Girard, C.; Breton, R.; Belanger, A.; Hum, D.W. N-glycosylation and residue 96 are involved in the functional properties of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 11540–11552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumida, A.; Kinoshita, K.; Fukuda, T.; Matsuda, H.; Yamamoto, I.; Inaba, T.; Azuma, J. Relationship between mRNA levels quantified by reverse transcription-competitive PCR and metabolic activity of CYP3A4 and CYP2E1 in human liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999, 262, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trottier, J.; El Husseini, D.; Perreault, M.; Paquet, S.; Caron, P.; Bourassa, S.; Verreault, M.; Inaba, T.T.; Poirier, G.G.; Belanger, A.; et al. The human UGT1A3 enzyme conjugates norursodeoxycholic acid into a C23-ester glucuronide in the liver. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, L.; Campeau, A.-S.; Caron, S.; Morin, F.-A.; Meunier, K.; Trottier, J.; Caron, P.; Verreault, M.; Barbier, O. Enantiomer Selective Glucuronidation of the Non-Steroidal Pure Anti-Androgen Bicalutamide by Human Liver and Kidney: Role of the Human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A9 Enzyme. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2013, 113, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanioka, N.; Isobe, T.; Tanaka-Kagawa, T.; Jinno, H.; Ohkawara, S. In vitro glucuronidation of bisphenol A in liver and intestinal microsomes: interspecies differences in humans and laboratory animals. Drug Chem Toxicol 2022, 45, 1565–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, L.; Chouinard, S.; Paquet, S.; Verreault, M.; Trottier, J.; Belanger, A.; Barbier, O. Androgen Glucuronidation in Mice: When, Where, and How. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.B.; Klaassen, C.D. Tissue- and gender-specific mRNA expression of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) in mice. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2007, 35, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, C.S.; Kenneke, J.F.; Hess-Wilson, J.K.; Lipscomb, J.C. Differences between human and rat intestinal and hepatic bisphenol A glucuronidation and the influence of alamethicin on in vitro kinetic measurements. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2010, 38, 2232–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Yuki, G.; Yokota, H.; Kato, S. Bisphenol A glucuronidation and absorption in rat intestine. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2003, 31, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teeguarden, J.G.; Waechter, J.M., Jr.; Clewell, H.J., 3rd; Covington, T.R.; Barton, H.A. Evaluation of oral and intravenous route pharmacokinetics, plasma protein binding, and uterine tissue dose metrics of bisphenol A: a physiologically based pharmacokinetic approach. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology 2005, 85, 823–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, P.I.; Hu, D.G.; Gardner-Stephen, D.A. The regulation of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase genes by tissue-specific and ligand-activated transcription factors. Drug Metab Rev 2010, 42, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.A.; Vom Saal, F.S.; Welshons, W.V.; Drury, B.; Rottinghaus, G.; Hunt, P.A.; Toutain, P.L.; Laffont, C.M.; VandeVoort, C.A. Similarity of bisphenol A pharmacokinetics in rhesus monkeys and mice: relevance for human exposure. Environmental health perspectives 2011, 119, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, H.; Tsuruta, A.; Kudo, S.; Ishii, T.; Fukushima, Y.; Iwano, H.; Yokota, H.; Kato, S. Bisphenol a glucuronidation and excretion in liver of pregnant and nonpregnant female rats. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals 2005, 33, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer forward | Primer reverse | Temp | |

| PPIA | 5’-TCCTGGCATCTTGTCCATG-3’ | 5’-CATCCAGCCATTCAGTCTTG-3’ | 56°C |

| Ugt2b1 | 5’-TATGTTGCAGGTGTTGCT-3’ | 5’-GTCCCAGAAGGTTCGAAC-3’ | 62°C |

| Ugt2b34 | 5’-ATGTCAGAATTGAGTGACAGG-3’ | 5’-TGTCGTGGGTCTTCCTAAT-3’ | 63°C |

| ♂ 1 | ♂ 2 | Mean ♂1+2 | ♀ 1 | ♀ 2 | Mean ♀1+2 | Mean ♂+♀ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | 5,484.0±293.1 | 6,663.9±783.0 | 6,074.0±835.1 | 5,594.1±312.2 | 5,407.0±662.6 | 5,500.6±503.4 | 5,787.3±735.2 |

| Kidney | 423.0±5.0 | 275.6±3.3 | 349.3±80.8 | 609.5±39.5 | 436.2±48.8 | 522.8±102.9 | 436.1±126.5 |

| Duodenum | 715.6±89.0 | 303.6±5.9 | 509.6±232.6 | 901.5±86.6 | 1,526.4±114.6 | 1,214.0±354.1 | 861.8±465.7 |

| Jejunum | 393.3±5.8 | 324.0±98.0 | 358.6±72.8 | 1,469.7±113.2 | 129.8±13.4 | 799.8±737.4 | 579.2±550.2 |

| Ileum | 127.6±5.2 | 315.2±14.7 | 221.4±103.2 | 100.3±8.4 | 14.3±3.7 | 57.3±47.5 | 139.3±114.9 |

| Caecum | 1,416.4±56.5 | 207.4±10.5 | 811.9±663.2 | 136.6±11.5 | 2,442.2±82.5 | 1,289.4±1,263.9 | 1,050.7±994.1 |

| Colon | 1,192.5±63.4 | 524.2±209.8 | 858.4±391.4 | 1,397.1±65.5 | 768.4±25.0 | 1,082.8±347.2 | 970.6±371.7 |

| Mammary gland | 7.1±1.9 | 7.9±0.4 | 7.5±1.3 | 13.4±0.7 | 19.1±2.8 | 16.3±3.6 | 11.9±5.3 |

| Gallbladder | 1,643.9±175.5 | 3,256.6±1,097.6 | 2,450.3±1,129.0 | 2,556.2±328.8 | 2,348.7±477.2 | 2,452.5±383.7 | 2,451.4±803.9 |

| Heart | B.L.Q | 1.1±0.4 | 1.1±0.4 | 4.4±0.6 | 1.1±0.1 | 2.7±1.8 | 1.8±1.6 |

| Brain | B.L.Q | 1.1±0.1 | 1.1±0.1 | 0.8±0.2 | B.L.Q | 0.8±0.2 | 0.9±0.2 |

| Stomach | 295.4±48.7 | 401.0±20.3 | 348.2±66.8 | 235.8±77.7 | 1,184.8±107.6 | 710.3±526.6 | 529.2±404.7 |

| Lung | 22.2±1.0 | 27.3±1.0 | 24.8±3.0 | 34.4±4.1 | 27.6±0.7 | 31.0±4.5 | 27.9±4.9 |

| Muscle | 0.9±0.1 | 0.3±0.0 | 0.6±0.4 | B.L.Q | B.L.Q | B.L.Q | 0.6±0.4 |

| Adipose tissue | 17.3±1.4 | 41.1±3.1 | 29.2±13.2 | 43.7±5.2 | 33.9±3.4 | 38.8±6.6 | 34.0±11.1 |

| Bladder | 249.2±8.7 | 847.1±76.7 | 548.1±331.1 | 257.4±24.4 | 391.1±63.7 | 324.3±85.0 | 436.2±258.4 |

| Pancreas | 16.6±2.0 | 22.9±3.2 | 19.8±4.2 | 35.3±10.1 | 26.0±15.8 | 30.7±12.9 | 25.2±10.8 |

| ♂ 1 | ♂ 2 | Mean ♂1+2 | ♀ 1 | ♀ 2 | Mean ♀1+2 | Mean♂+♀ | |

| Spleen | 3.7±0.2 | 6.4±0.9 | 5.0±1.6 | 7.0±0.3 | 20.0±0.2 | 13.5±7.1 | 9.3±6.6 |

| Adrenals | 3.4±0.1 | 7.8±0.3 | 5.6±2.4 | 4.9±0.1 | 5.9±0.5 | 5.4±0.7 | 5.5±1.7 |

| Skin | 1.3±0.1 | 9.1±0.4 | 5.2±4.3 | 2.0±0.1 | 2.1±0.1 | 2.1±0.1 | 3.6±3.3 |

| Prostate | 4.3±0.5 | 4.5±0.2 | 4.4±0.4 | N.A | N.A | N.A | 4.4±0.4 |

| Epididymis | 9.8±1.3 | 25.4±2.6 | 17.6±8.7 | N.A | N.A | N.A | 17.6±8.7 |

| Testis | 113.5±2.9 | 133.4±12.2 | 123.4±13.5 | N.A | N.A | N.A | 123.4±13.5 |

| Bulbospongious | B.L.Q | 2.0±0.1 | 2.0±0.1 | N.A | N.A | N.A | 2.0±0.1 |

| Seminal vesicle | 3.4±0.2 | B.L.Q | 3.4±0.2 | N.A | N.A | N.A | 3.4±0.2 |

| Uterus | N.A | N.A | N.A | 36.7±1.6 | 32.2±6.5 | 34.5±4.9 | 34.5±4.9 |

| Oviduct | N.A | N.A | N.A | 155.3±5.3 | 124.3±7.0 | 139.8±17.9 | 139.8±17.9 |

| Ovary | N.A | N.A | N.A | 11.7±3.1 | 14.9±1.4 | 13.3±2.8 | 13.3±2.8 |

| Vagina | N.A | N.A | N.A | 44.9±3.8 | 81.4±2.6 | 63.1±20.2 | 63.1±20.2 |

| KM | Vmaxapp. | CLINT. (Vmaxapp./KM) | ||

| µM | pmol/min/mg proteins | μL/min/mg proteins | ||

| Mice | ♂ 1 | 76.2±6.8 | 8,447.5±1,244.5 | 110.9 |

| ♂ 2 | 157.9±26.0 | 10,814.6±923.9 | 68.7 | |

| ♂ 3 | 64.6±9.2 | 5,461.5±114.9 | 84.5 | |

| Mean ♂ 1-3 | 99.6±50.8 | 8,241.2±2,457.1 | 88.0±21.3 | |

| ♀ 1 | 52.6±7.7 | 4,834.2±827.6 | 91.9 | |

| ♀ 2 | 39.9±4.9 | 4,519.6±333.1 | 113.4 | |

| ♀ 3 | 75.3±7.1 | 6,798.9±338.5 | 90.3 | |

| Mean ♀ 1-3 | 55.9±18.0 | 5,384.2±1,171.3 | 98.5±12.9 | |

| Mean♂+♀ | 77.8±41.6 | 6,812.7±2,376.4 | 93.3±16.8 | |

| Human | Assay 1 | 33.3±6.8 | 2,079.9±341.9 | 62.4 |

| Assay 2 | 37.5±3.6 | 2,854.6±92.7 | 76.1 | |

| Mean | 35.4±3.0 | 2,467.3±547.9 | 69.2±9.7 |

| KM | Vmaxapp. | CLINT. (Vmaxapp./KM) | ||

| µM | pmol/min/mg proteins | μL/min/mg proteins | ||

| Caecum | ♂ | 97.1±13.3 | 4,223.1±410.9 | 43.5 |

| ♀ | 74.4±9.4 | 8,443.5±298.4 | 113.4 | |

| ♂+♀ | 85.8±16.0 | 6,333.3±2,984.3 | 78.5±49.5 | |

| Colon | ♂ | 82.3±13.7 | 5,844.3±85.9 | 71.0 |

| ♀ | 52.1±5.4 | 1,556.7±188.3 | 29.9 | |

| ♂+♀ | 67.2±21.4 | 3,700.5±3,031.8 | 50.4±29.1 | |

| Gallbladder | Pool* | 19.6±7.5 | 3,729.4±92.9 | 190.3 |

| KM | Vmaxapp. | CLINT. (Vmaxapp./KM) | ||

| µM | pmol/min/mg proteins | μL/min/mg proteins | ||

| Ugt2b1 | Assay 1 | 2.6±0.5 | 333.5±17.8 | 126.3 |

| Assay 2 | 2.3±0.6 | 445.2±48.3 | 191.9 | |

| Mean | 2.5±0.2 | 389.4±79.0 | 159.1±46.4 | |

| Ugt2b34 | Assay 1 | 100.7±17.4 | 8,615.5±1,003.9 | 85.5 |

| Assay 2 | 96.0±9.5 | 10,747.2±670.6 | 111.9 | |

| Mean | 98.4±3.3 | 9,681.3±1,507.3 | 98.7±18.7 | |

| UGT2B15 | Assay 1 | 36.7±4.4 | 897.1±166.8 | 24.4 |

| Assay 2 | 37.8±4.8 | 1,103.1±54.9 | 29.2 | |

| Mean | 37.2±0.8 | 1,000.1±145.7 | 26.8±3.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).