Submitted:

24 August 2025

Posted:

25 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

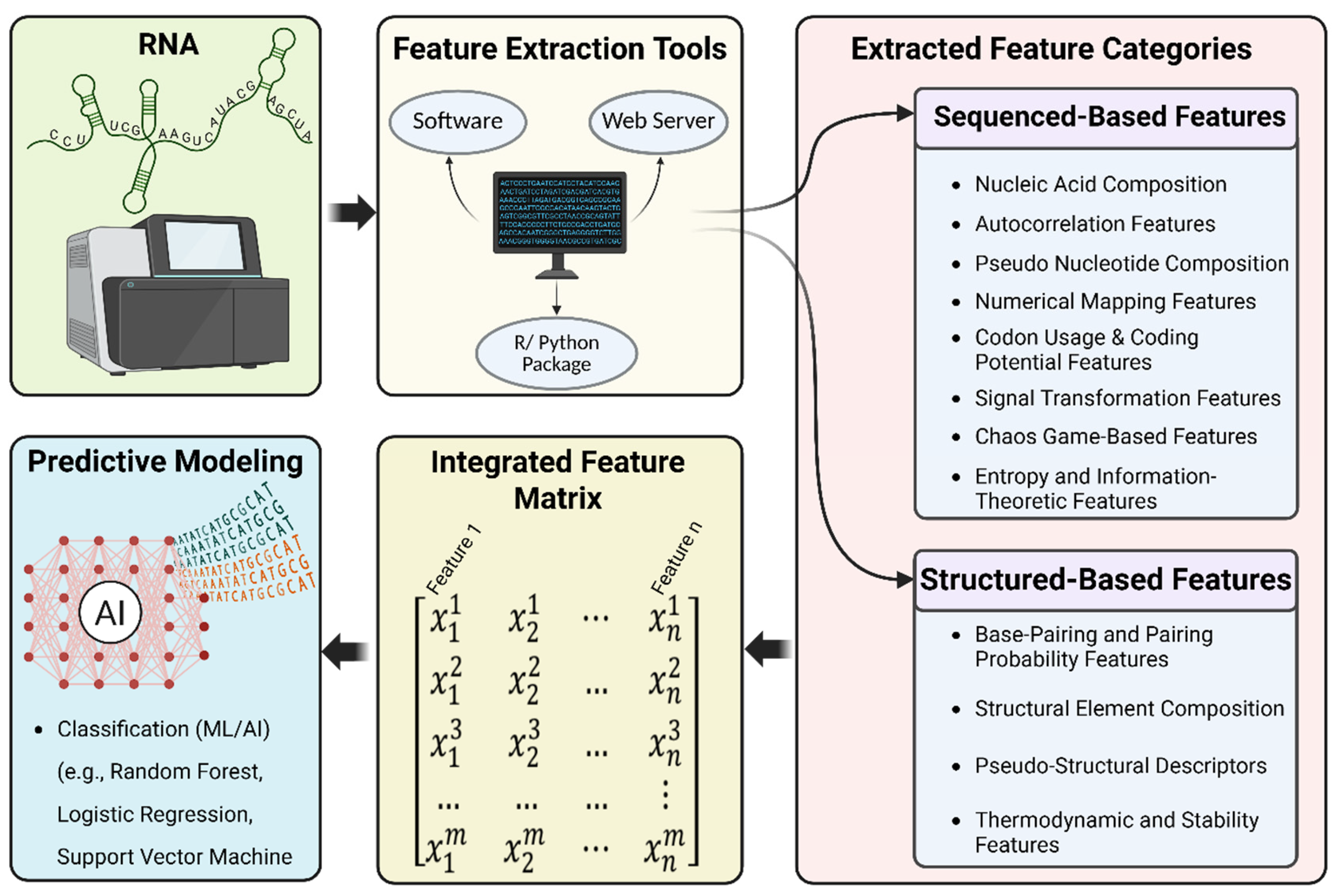

2. Foundations of RNA Feature Extraction

2.1. Sequence-Based Features

2.1.1. Nucleic Acid Composition

2.1.2. Autocorrelation Descriptors

2.1.3. Pseudo Nucleotide Composition

2.1.4. Numerical Mapping Features

2.1.5. Codon Usage and Coding Potential Features

2.1.6. Signal Transformation Features (Fourier-Based)

2.1.7. Chaos Game-Based Features

2.1.8. Entropy and Information-Theoretic Features

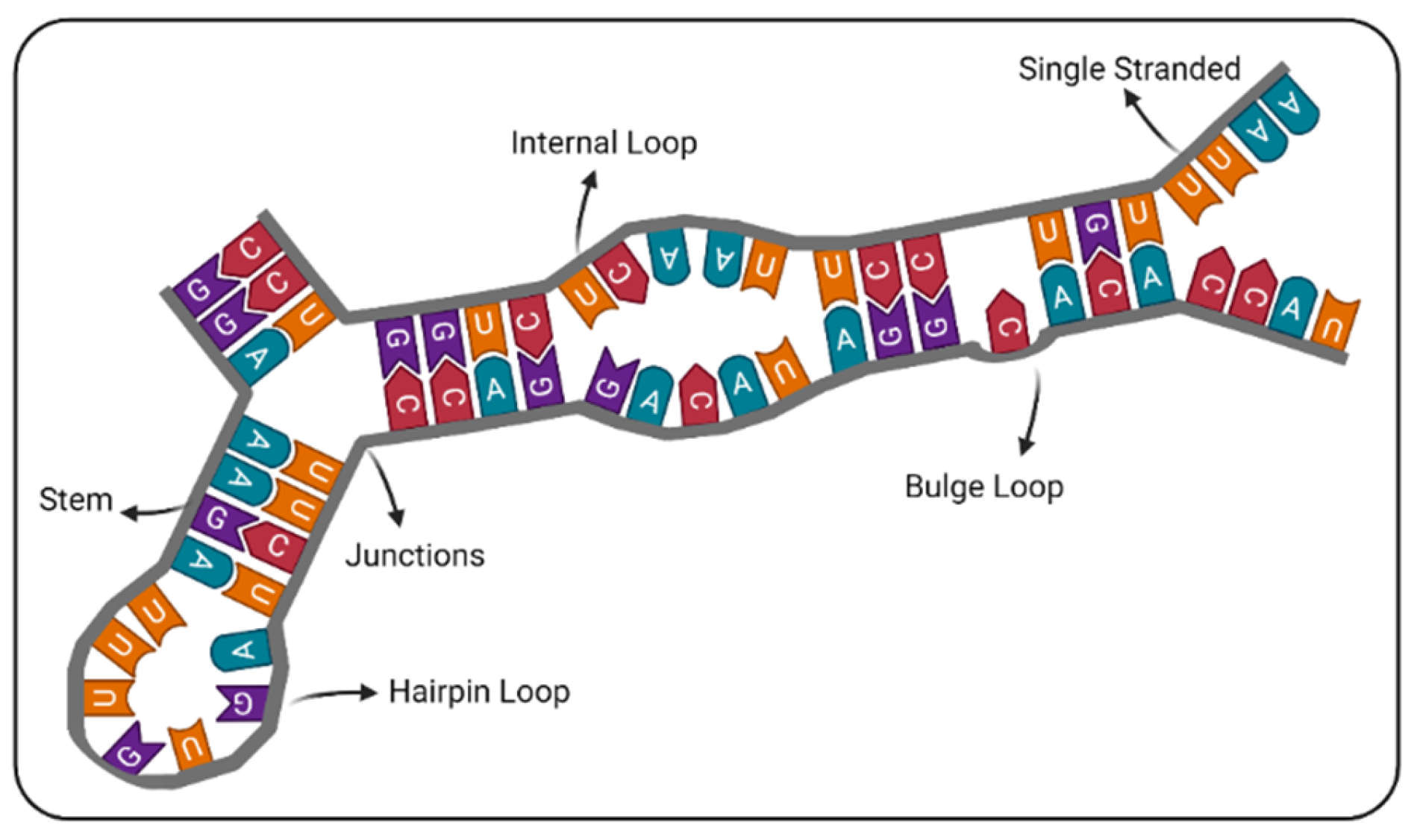

2.2. Structural Feature Extraction

2.2.1. Paired Ratio

2.2.2. Triplet

2.2.3. Pseudo-Structure Status Composition (PseSSC) & Pseudo-Distance Structure Status Pair Composition (PseDPC)

2.2.4. Number of Distinct Loop Structures

2.2.5. Coverage of Different Loop Structures

2.2.6. GC Content of Paired Nucleotides

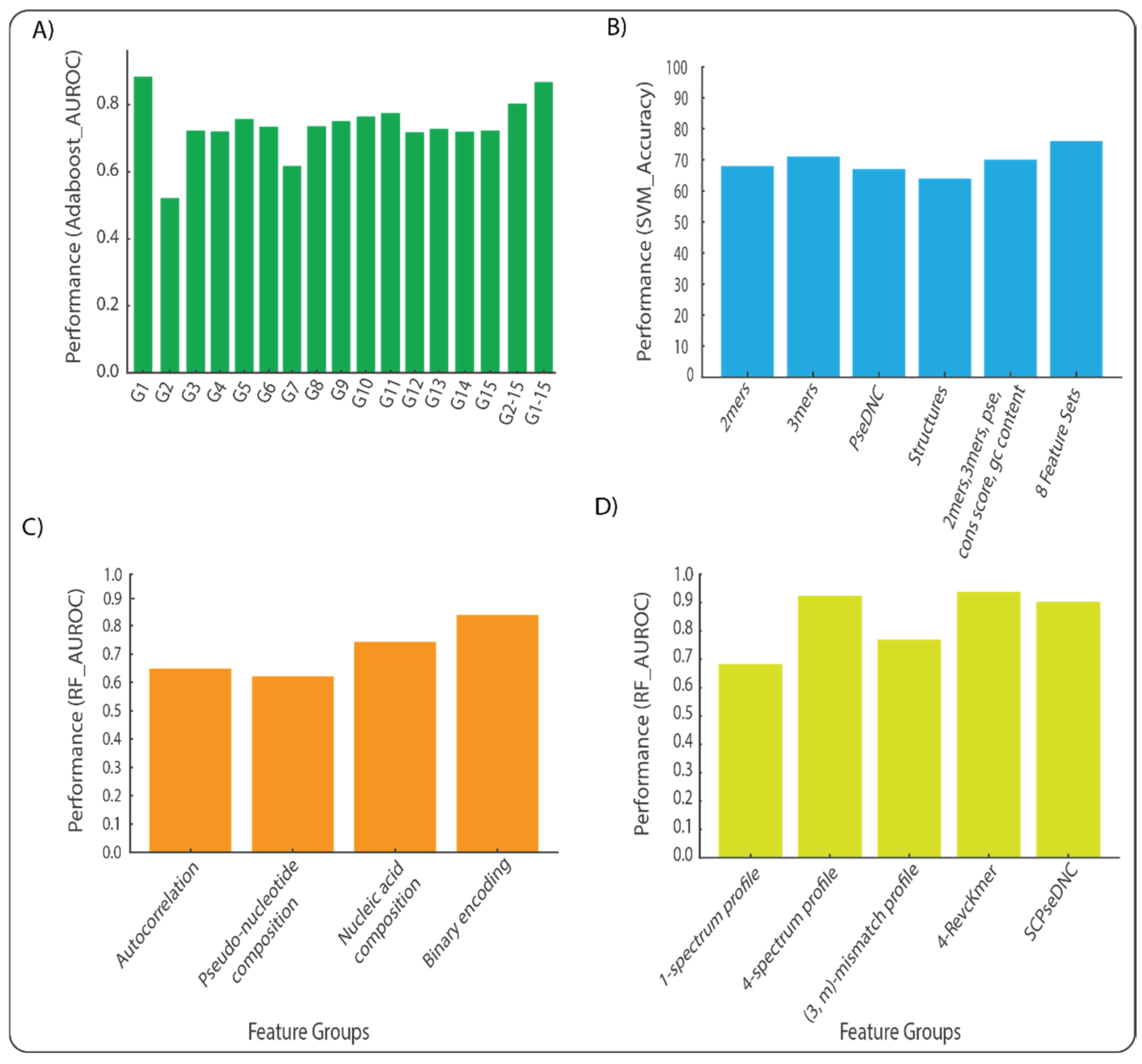

3. Comparative Impact of Feature Set Choice on Model Performance

4. Feature Extraction Tools

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Kukurba KR, Montgomery SB. RNA Sequencing and Analysis. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2015 Apr 13;2015(11):951–69.

- Deshpande, D.; Chhugani, K.; Chang, Y.; Karlsberg, A.; Loeffler, C.; Zhang, J.; Muszyńska, A.; Munteanu, V.; Yang, H.; Rotman, J.; et al. RNA-seq data science: From raw data to effective interpretation. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 997383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitić, T.; Caporali, A. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in endothelial cell function. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2023, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvier, A.; Walter, N.G. Regulation of bacterial gene expression by non-coding RNA: It is all about time! Cell Chem. Biol. 2024, 31, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinn JL, Chang HY. Genome regulation by long noncoding RNAs. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:145–66.

- Schmitt AM, Chang HY. Long noncoding RNAs in cancer pathways. Cancer cell. 2016 Apr 11;29(4):452-63.

- van der Sluis F, van den Broek EL. Model interpretability enhances domain generalization in the case of textual complexity modeling. Patterns (N Y). 2025 Feb 6;6(2):101177.

- Murdoch, W.J.; Singh, C.; Kumbier, K.; Abbasi-Asl, R.; Yu, B. Definitions, methods, and applications in interpretable machine learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 22071–22080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greener, J.G.; Kandathil, S.M.; Moffat, L.; Jones, D.T. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 23, 40–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonidia, R.P.; Sampaio, L.D.H.; Domingues, D.S.; Paschoal, A.R.; Lopes, F.M.; de Carvalho, A.C.P.L.F.; Sanches, D.S. Feature extraction approaches for biological sequences: a comparative study of mathematical features. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, B.; Dauvin, A.; Cabeli, V.; Kmetzsch, V.; El Khoury, J.; Dissez, G.; Ouardini, K.; Grouard, S.; Davi, A.; Loeb, R.; et al. Robust evaluation of deep learning-based representation methods for survival and gene essentiality prediction on bulk RNA-seq data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Jeon, H.; Yeo, N.; Baek, D. Big data and deep learning for RNA biology. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 1293–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, A.L.; Bustillo, L.; Rodrigues, T. Limitations of representation learning in small molecule property prediction. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, L.; Gouk, H.; Loy, C.C.; Hospedales, T.M. Self-Supervised Representation Learning: Introduction, advances, and challenges. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2022, 39, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Yang, Y.; Xia, C.; Mirza, A.H.; Shen, H. Recent methodology progress of deep learning for RNA–protein interaction prediction. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2019, 10, e1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Núñez JR, Rodríguez C, Vásquez-Serpa LJ, Navarro C. The Challenge of Deep Learning for the Prevention and Automatic Diagnosis of Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Dec 23;14(24):2896.

- Ding, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, X.; Tian, Y.; Dai, J. Trade-offs between machine learning and deep learning for mental illness detection on social media. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonidia, R.P.; Domingues, D.S.; Sanches, D.S.; de Carvalho, A.C.P.L.F. MathFeature: feature extraction package for DNA, RNA and protein sequences based on mathematical descriptors. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Li, X.; Ding, H.; Xu, L.; Xiang, H. Prediction of m5C Modifications in RNA Sequences by Combining Multiple Sequence Features. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2020, 21, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.-X.; Li, S.-H.; Zhang, Z.-M.; Zhang, D.; Yang, H.; Ding, H. A Brief Survey for MicroRNA Precursor Identification Using Machine Learning Methods. Curr. Genom. 2020, 21, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Meng, J.; Luan, Y. RNAI-FRID: novel feature representation method with information enhancement and dimension reduction for RNA–RNA interaction. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arceda VM. An Analysis of k-Mer Frequency Features with Machine Learning Models for Viral Subtyping of Polyomavirus and HIV-1 Genomes. InProceedings of the Future Technologies Conference 2020 Oct 31 (pp. 279-290). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kirk, J.M.; Kim, S.O.; Inoue, K.; Smola, M.J.; Lee, D.M.; Schertzer, M.D.; Wooten, J.S.; Baker, A.R.; Sprague, D.; Collins, D.W.; et al. Functional classification of long non-coding RNAs by k-mer content. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzi, C.; Barriere, S.; Villemin, J.-P.; Bretones, L.D.; Mancheron, A.; Ritchie, W. iMOKA: k-mer based software to analyze large collections of sequencing data. Genome Biol. 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Jia, P.; Zhao, Z. Deep4mC: systematic assessment and computational prediction for DNA N4-methylcytosine sites by deep learning. Briefings Bioinform. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Shi, J.; Tang, G.; Wu, W.; Yue, X.; Li, D. Predicting small RNAs in bacteria via sequence learning ensemble method. 2017 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 643–647.

- Luo, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, W.; Tu, S.; Zhu, X.; Tian, G.; Liu, B. Accurate Prediction of Transposon-Derived piRNAs by Integrating Various Sequential and Physicochemical Features. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0153268–e0153268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, C.S.; Eskin, E.; Cohen, A.; Weston, J.; Noble, W.S. Mismatch string kernels for discriminative protein classification. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liang, C. LncDC: a machine learning-based tool for long non-coding RNA detection from RNA-Seq data. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Tran, H.; Liang, Z.; Lin, H.; Zhang, L. Identification and analysis of the N6-methyladenosine in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae transcriptome. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, srep13859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammod, R.; Ahmed, S.; Farid, D.M.; Shatabda, S.; Sharma, A.; Dehzangi, A.; Hancock, J. PyFeat: a Python-based effective feature generation tool for DNA, RNA and protein sequences. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 3831–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubert, B. SkewDB, a comprehensive database of GC and 10 other skews for over 30,000 chromosomes and plasmids. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rzhetsky, A. SkewIT: The Skew Index Test for large-scale GC Skew analysis of bacterial genomes. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, G.-H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G.-Z.; Yang, L. RNAlight: a machine learning model to identify nucleotide features determining RNA subcellular localization. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. BioSeq-Analysis: a platform for DNA, RNA and protein sequence analysis based on machine learning approaches. Briefings Bioinform. 2017, 20, 1280–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur M, Patiyal S, Dhall A, Jain S, Tomer R, Arora A, Raghava GP. Nfeature: A platform for computing features of nucleotide sequences. BioRxiv. 2021 Dec 16:2021-12.

- Chen, Zhen, Pei Zhao, Chen Li, Fuyi Li, Dongxu Xiang, Yong-Zi Chen, Tatsuya Akutsu et al. iLearnPlus: a comprehensive and automated machine-learning platform for nucleic acid and protein sequence analysis, prediction and visualization. Nucleic acids research 49, no. 10 (2021): e60-e60.

- Chen, W.; Lei, T.-Y.; Jin, D.-C.; Lin, H.; Chou, K.-C. PseKNC: A flexible web server for generating pseudo K-tuple nucleotide composition. Anal. Biochem. 2014, 456, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, X.; Brooker, J.; Lin, H.; Zhang, L.; Chou, K.-C. PseKNC-General: a cross-platform package for generating various modes of pseudo nucleotide compositions. Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 119–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Fang, L.; Chou, K.-C. Pse-in-One: a web server for generating various modes of pseudo components of DNA, RNA, and protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W65–W71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lin, H.; Chou, K.-C. Pseudo nucleotide composition or PseKNC: an effective formulation for analyzing genomic sequences. Mol. Biosyst. 2015, 11, 2620–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Wu, H.; Chou, K.-C. Pse-in-One 2.0: An Improved Package of Web Servers for Generating Various Modes of Pseudo Components of DNA, RNA, and Protein Sequences. Nat. Sci. 2017, 09, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Liu, F.; Fang, L.; Wang, X.; Chou, K.-C. repRNA: a web server for generating various feature vectors of RNA sequences. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2015, 291, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, P.-F.; Zhao, W.; Miao, Y.-Y.; Wei, L.-Y.; Wang, L. UltraPse: A Universal and Extensible Software Platform for Representing Biological Sequences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsonis, A.A.; Elsner, J.B.; Tsonis, P.A. Periodicity in DNA coding sequences: Implications in gene evolution. J. Theor. Biol. 1991, 151, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassiou, D. Genomic signal processing. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2001, 18, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarthy, N.; Spanias, A.; Iasemidis, L.D.; Tsakalis, K. Autoregressive Modeling and Feature Analysis of DNA Sequences. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2004, 2004, 952689–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshid, H.O.; Pham, N.T.; Manavalan, B.; Kurata, H.; Akbar, S. Meta-2OM: A multi-classifier meta-model for the accurate prediction of RNA 2′-O-methylation sites in human RNA. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0305406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.-T. Z Curves, An Intutive Tool for Visualizing and Analyzing the DNA Sequences. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1994, 11, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-L. Study on the Specific ncRNAs Based on Z-curve Method. 2008 International Conference on MultiMedia and Information Technology (MMIT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 790–793.

- Yang Y ling, Wang J, Yu JF, Liu G zhong. An Analysis of Non-Coding RNA Using Z-Curve Method. In 2008. p. 129–32.

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.-T. A Brief Review: The Z-curve Theory and its Application in Genome Analysis. Curr. Genom. 2014, 15, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Park, H.J.; Dasari, S.; Wang, S.; Kocher, J.-P.; Li, W. CPAT: Coding-Potential Assessment Tool using an alignment-free logistic regression model. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e74–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roymondal, U.; Das, S.; Sahoo, S. Predicting Gene Expression Level from Relative Codon Usage Bias: An Application to Escherichia coli Genome. DNA Res. 2009, 16, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonidia, R.P.; Sampaio, L.D.H.; Domingues, D.S.; Paschoal, A.R.; Lopes, F.M.; de Carvalho, A.C.P.L.F.; Sanches, D.S. Feature extraction approaches for biological sequences: a comparative study of mathematical features. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, T.; Yin, C.; Yau, S.S.-T. Numerical encoding of DNA sequences by chaos game representation with application in similarity comparison. Genomics 2016, 108, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, C.; Chen, Y.; Yau, S.S.-T. A measure of DNA sequence similarity by Fourier Transform with applications on hierarchical clustering. J. Theor. Biol. 2014, 359, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löchel, H.F.; Heider, D. Chaos game representation and its applications in bioinformatics. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 6263–6271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, S.; Bailey, B.A.; Salamon, P.; Aziz, R.K.; Edwards, R.A. Applying Shannon's information theory to bacterial and phage genomes and metagenomes. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenreiro Machado JA, Costa AC, Quelhas MD. Shannon, Rényie and Tsallis entropy analysis of DNA using phase plane. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications. 2011 Dec 1;12(6):3135–44.

- Tsallis, C.; Mendes, R.; Plastino, A. The role of constraints within generalized nonextensive statistics. Phys. A: Stat. Mech. its Appl. 1998, 261, 534–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamano, T. Information theory based on nonadditive information content. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 63, 046105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter JS, Mathews DH. RNAstructure: software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010 Mar 15;11(1):129.

- Han, S.; Liang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, W.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. LncFinder: an integrated platform for long non-coding RNA identification utilizing sequence intrinsic composition, structural information and physicochemical property. Briefings Bioinform. 2018, 20, 2009–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Hamada, M. Recent trends in RNA informatics: a review of machine learning and deep learning for RNA secondary structure prediction and RNA drug discovery. Briefings Bioinform. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathews, D.H.; Turner, D.H. Prediction of RNA secondary structure by free energy minimization. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006, 16, 270–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, D.H.; Sabina, J.; Zuker, M.; Turner, D.H. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 288, 911–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; SantaLucia, J., Jr.; Burkard, M.E.; Kierzek, R.; Schroeder, S.J.; Jiao, X.; Cox, C.; Turner, D.H. Thermodynamic Parameters for an Expanded Nearest-Neighbor Model for Formation of RNA Duplexes with Watson−Crick Base Pairs. Biochemistry 1998, 37, 14719–14735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, D.H.; Disney, M.D.; Childs, J.L.; Schroeder, S.J.; Zuker, M.; Turner, D.H. Incorporating chemical modification constraints into a dynamic programming algorithm for prediction of RNA secondary structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 7287–7292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Chan, C.Y.; Lawrence, C.E. RNA secondary structure prediction by centroids in a Boltzmann weighted ensemble. RNA 2005, 11, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Z.J.; Gloor, J.W.; Mathews, D.H. Improved RNA secondary structure prediction by maximizing expected pair accuracy. RNA 2009, 15, 1805–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Honer Zu Siederdissen, C.; Tafer, H.; Flamm, C.; Stadler, P.F.; Hofacker, I.L. ViennaRNA Package 2.0. Algorithms Mol. Biol. 2011, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List of RNA structure prediction software. In: Wikipedia [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Aug 11]. t: Available from, 1305.

- Xue, C.; Li, F.; He, T.; Liu, G.-P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Classification of real and pseudo microRNA precursors using local structure-sequence features and support vector machine. BMC Bioinform. 2005, 6, 310–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ali, H.; Xu, Y.; Xie, J.; Xu, S. BiPSTP: Sequence feature encoding method for identifying different RNA modifications with bidirectional position-specific trinucleotides propensities. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fang, L.; Liu, F.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Chou, K.-C.; Budak, H. Identification of Real MicroRNA Precursors with a Pseudo Structure Status Composition Approach. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0121501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu B, Fang L, Liu F, Wang X, Chou KC. iMiRNA-PseDPC: microRNA precursor identification with a pseudo distance-pair composition approach. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics. 2016 Jan 2;34(1):223–35.

- Lopes, I.d.O.; Schliep, A.; Carvalho, A.C.d.L.d. The discriminant power of RNA features for pre-miRNA recognition. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, 124–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, T.; Mendel, J.; Cho, H.; Choudhary, M. Prediction of Bacterial sRNAs Using Sequence-Derived Features and Machine Learning. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalid, R.; Naveed, H.; Khalid, Z. Computational prediction of disease related lncRNAs using machine learning. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Ju, Y.; Zou, Q.; Ni, F. lncRNA localization and feature interpretability analysis. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2024, 36, 102425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Shi, J.; Wu, W.; Yue, X.; Zhang, W. Sequence-based bacterial small RNAs prediction using ensemble learning strategies. BMC Bioinform. 2018, 19, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, J.; Yao, Z.-J.; Wen, M.; Zhu, M.-F.; Wang, N.-N.; Miao, H.-Y.; Lu, A.-P.; Zeng, W.-B.; Cao, D.-S. BioTriangle: a web-accessible platform for generating various molecular representations for chemicals, proteins, DNAs/RNAs and their interactions. J. Chemin- 2016, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H. BioSeq-Analysis2.0: an updated platform for analyzing DNA, RNA and protein sequences at sequence level and residue level based on machine learning approaches. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e127–e127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhao, P.; Li, F.; Marquez-Lago, T.T.; Leier, A.; Revote, J.; Zhu, Y.; Powell, D.R.; Akutsu, T.; I Webb, G.; et al. iLearn: an integrated platform and meta-learner for feature engineering, machine-learning analysis and modeling of DNA, RNA and protein sequence data. Briefings Bioinform. 2019, 21, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerifar, S.; Norouzi, M.; Ghandi, M. A tool for feature extraction from biological sequences. Briefings Bioinform. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, K.-C. Some remarks on protein attribute prediction and pseudo amino acid composition. J. Theor. Biol. 2011, 273, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Tool/Package Name | Access Type | Type of Feature Categories | Published Year | Ref |

| RepRNA | Web server | Oligonucleotide composition; pseudo-nucleotide composition; structure composition | 2016 | [45] |

| PseKNC | Web server | Pseudo-dinucleotide composition (PseDNC); pseudo-trinucleotide composition (PseTNC) | 2014 | [39] |

| PseKNC-General | Web server | K-tuple nucleotide composition; autocorrelation descriptors; pseudo-nucleotide composition | 2015 | [40] |

| BioTriangle | Web server | Nucleic acid composition; autocorrelation descriptors; pseudo-nucleotide composition | 2016 | [85] |

| BioSeq-Analysis2.0 | Web server | Residue-level composition; sequence-level physicochemical and structural descriptors | 2019 | [86] |

| BioSeq-Analysis | Standalone program & web server | Nucleic acid composition; autocorrelation descriptors; pseudo-nucleotide composition; predicted structure composition | 2019 | [36] |

| Nfeature | R/Python package & web server | Nucleic acid composition; distance distribution of nucleotides; nucleotide repeat index; pseudo-composition; entropy | 2021 | [37] |

| iLearn | Python toolkit | Nucleic acid composition; binary encoding; position-specific trinucleotide tendencies; autocorrelation; pseudo-composition | 2019 | [87] |

| iLearnPlus | R/Python package & web server | Nucleic acid composition; residue composition; position-specific trinucleotide tendencies; autocorrelation; physicochemical; mutual information; similarity-based; pseudo-composition | 2021 | [38] |

| ftrCOOL | R/Python package | Nucleic acid composition; substitution matrices; k-nearest-neighbor RNA; local position-specific k-frequency; maxORF-based | 2022 | [88] |

| PyFeat | Python toolkit | Z-curve; GC content; AT/GC ratio; cumulative skew; Chou’s pseudo-composition; k-gap statistics | 2019 | [32] |

| MathFeature | R/Python package & web server | Numerical mapping; chaos game descriptors; Fourier transform; entropy and graph descriptors; pseudo-composition | 2022 | [19] |

| Pse-In-One | Web server | Nucleic acid composition; autocorrelation descriptors; pseudo-nucleotide composition | 2015 | [41] |

| Pse-in-One 2.0 | Web server | Nucleic acid composition; autocorrelation; triplet sequence-structure elements; pseudo-structure status composition; PseDPC | 2017 | [44] |

| UltraPse | Software platform | Nucleic acid composition; autocorrelation descriptors; pseudo-nucleotide composition | 2017 | [46] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).