1. Introduction

Maternal immune activation (MIA) refers to a state in which the maternal immune system—critical for supporting fetal development—is activated during pregnancy by infections or other triggers. Emerging evidence links MIA to an increased risk of miscarriage as well as neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring, particularly autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [

1,

2,

3]. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), ASD is characterized by persistent deficits in social communication together with restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. Surveillance by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that approximately one in 36 children in the United States is diagnosed with ASD [

4,

5]. The apparent prevalence has risen in recent years, underscoring the urgency of elucidating pathogenic mechanisms and establishing effective interventions. MIA is recognized as an environmental factor that contributes to the pathogenesis of complex neurodevelopmental conditions through interactions with genetic susceptibility [

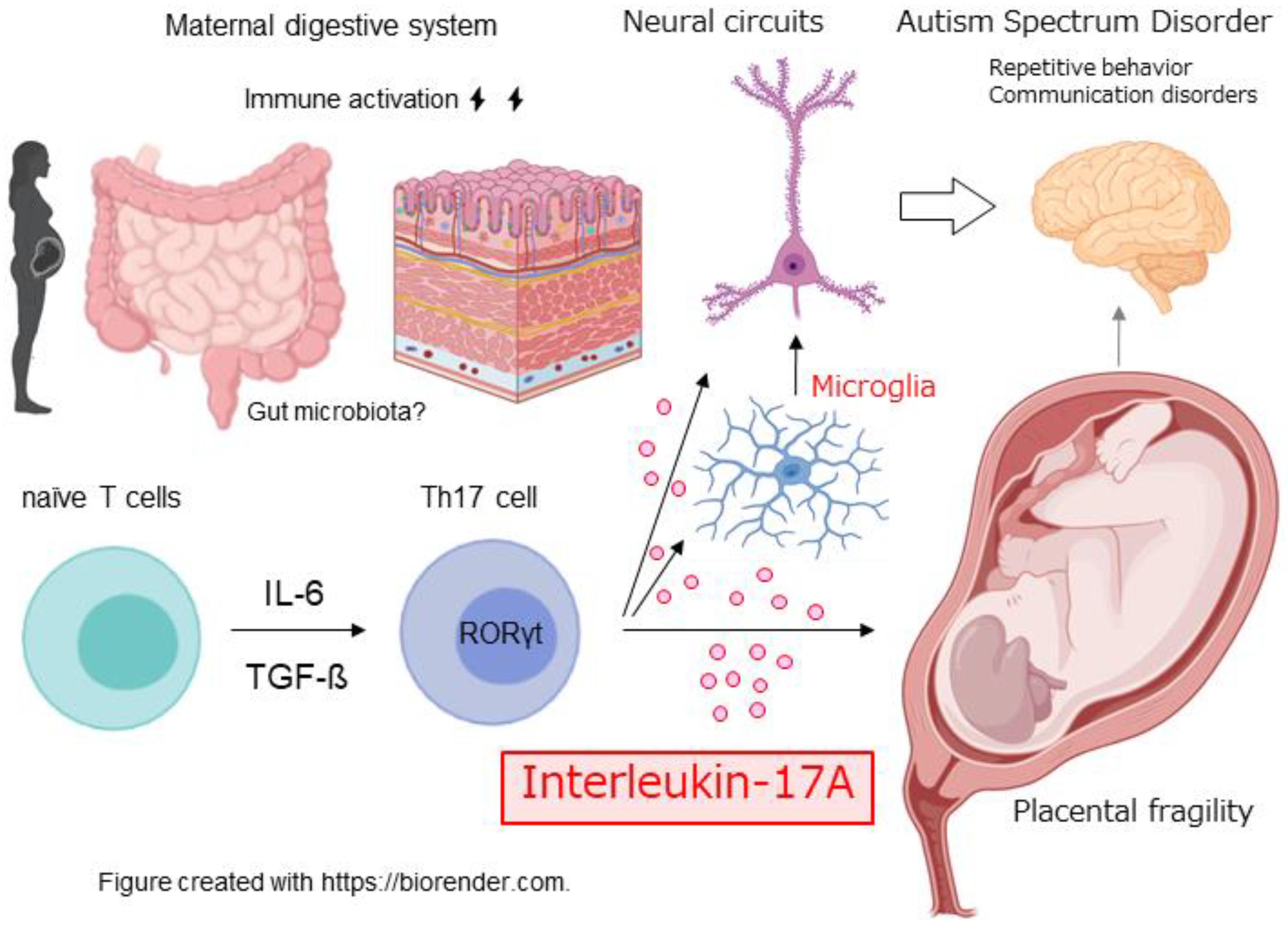

6]. This “two-hit hypothesis” posits that the combination of genetic vulnerability and environmental insults initiates disease and provides a valuable framework for understanding ASD’s complex etiology. In this review, we synthesize recent advances on how MIA affects miscarriage risk and fetal brain development. We focus in particular on interleukin-17A (IL-17A) and microglia, considering how these factors influence cortical development, and we conclude by discussing the clinical implications of MIA research and priorities for future investigation (

Figure 1).

2. Overview of Maternal Immune Activation (MIA)

Maternal immune activation (MIA) denotes a transient activation of the maternal immune system by bacterial or viral infection during pregnancy. While this response typically serves as a crucial defense that protects both mother and fetus from infection, excessive or dysregulated activation perturbs fetal development [

7]. Hallmark features include systemic inflammation, heightened cytokine production, and downstream effects on the placenta and the fetal brain. In preclinical research, the most widely used paradigm is administration of polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)]. This double-stranded RNA analog mimics viral infection and elicits a robust inflammatory cascade through Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3) [

8]. Complementary models—lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to simulate bacterial signals, live influenza infection, and stress-based paradigms—are also employed to interrogate distinct facets of MIA.

MIA induces a characteristic cytokine milieu dominated by interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interleukin-17A (IL-17A) [

9]. Each exerts discrete yet interacting effects on the developing brain: IL-6 governs neural progenitor proliferation and differentiation; IL-1β influences neuronal survival and synaptic plasticity; TNF-α modulates the balance between neuronal survival and death; and IL-17A, central to this review, drives microglial activation and can alter neural progenitor dynamics. These mediators operate within an integrated network rather than in isolation; understanding MIA therefore requires attention to the temporal dynamics and cross-talk of the cytokine network as a whole.

3. MIA and the Risk of Fetal Loss

Maternal immune activation (MIA) is recognized as a risk factor for miscarriage. Epidemiological studies show that infections during pregnancy increase the risk of fetal loss, with particularly strong associations reported for influenza and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [

10,

11,

12]. Additional evidence links maternal reproductive and obstetric histories to neurodevelopmental outcomes in offspring, including correlations between a maternal history of miscarriage and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk, associations between preterm birth and ASD, and increased ASD risk among fetuses exposed to preeclampsia [

13,

14,

15].

Mechanistically, MIA can precipitate fetal loss through placental dysfunction, breakdown of maternal–fetal immune tolerance, activation of coagulation pathways, and direct disturbances of fetal development. Pregnancy depends on shielding the semi-allogeneic fetus from maternal immune attack; MIA disrupts this delicate equilibrium. Among candidate mediators, interleukin-17A (IL-17A) is of particular interest. IL-17A is an inflammatory cytokine produced primarily by T helper 17 (Th17) cells [

16,

17]. Th17 differentiation requires the transcription factor RORγt, and converging evidence implicates this axis in heightened miscarriage risk [

18,

19,

20]. Clinically, women with recurrent spontaneous abortion exhibit higher circulating IL-17A levels than healthy pregnant controls [

21,

22].

To probe causality, we examined T-cell–specific RORγt-overexpressing mice (RORγt-Tg) in an MIA paradigm [

23,

24,

25]. RORγt-Tg dams show chronically elevated serum IL-17A, a significantly higher rate of poly(I: C)-induced fetal loss than wild-type dams, and reduced placental expression of the adhesion molecule E-cadherin—findings consistent with increased placental fragility under inflammatory challenge. Intriguingly, poly(I: C) administration did not further raise circulating IL-17A in RORγt-Tg dams, a pattern that could reflect feedback regulation, pregnancy-specific immune tolerance, or other immunomodulatory inputs [

3,

23]. Even so, the heightened susceptibility to fetal loss in RORγt-Tg pregnancies underscores the central contribution of IL-17A-driven pathways to MIA-induced miscarriage and highlights the complexity of immune regulation during gestation.

4. Relationship Between Miscarriage and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Several studies suggest an association between miscarriage and subsequent neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring [

15]. Reports indicate that women who experience recurrent miscarriages may have an increased likelihood that later-born children will develop neurodevelopmental conditions; however, the mechanisms underlying this association remain incompletely understood. Common etiologic substrates may contribute to both outcomes. The placenta, far from being a mere conduit for nutrients, is an active endocrine and immunologic organ that produces hormones and growth factors influencing fetal brain development. Placental dysfunction can precipitate miscarriage and, at the same time, adversely affect neurodevelopment—for example, by inducing fetal hypoxia and nutrient insufficiency. Moreover, specific placental histopathological features have been linked to increased risk of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in offspring. Collectively, these observations raise the possibility that placental health forms a mechanistic bridge between miscarriage and neurodevelopmental outcomes, although this field remains in progress and many questions persist.

5. Effects of MIA on Fetal Brain Development

Recent studies implicate T helper 17 (Th17) cells and interleukin-17A (IL-17A) in the pathogenesis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Elevated serum IL-17A has been observed in individuals with ASD, and higher IL-17A levels have been reported to correlate with greater symptom severity [

26,

27]. In mouse models of maternal immune activation (MIA), maternal production of IL-17A is induced by viral-mimetic immune challenges; notably, ASD-like cortical abnormalities and behavioral phenotypes are ameliorated by administration of anti-IL-17A antibodies, by genetic blockade of Th17 differentiation via RORγt deficiency, and by depletion of gut microbiota that drive Th17 responses [

28].

IL-17A appears to play a central role in the induction of ASD-like behaviors and cortical structural anomalies (so-called cortical “patches”) under MIA. In work by Choi and colleagues, MIA-induced maternal IL-17A production, the rescue of ASD-like behaviors by anti-IL-17A treatment, the suppression of these behaviors in RORγt-knockout mice, and the reproduction of ASD-like behaviors and cortical patches by direct fetal intraventricular IL-17A delivery were demonstrated [

29]. Mechanistically, IL-17A may act directly on neural progenitors or indirectly via microglia; additional proposed mechanisms include increased blood–brain barrier permeability, altered neuronal gene expression, and astrocyte activation. In combination, these actions can yield ASD-like structural and behavioral outcomes [

6,

30].

Microglia—the resident immune cells of the central nervous system—are pivotal to neurodevelopment [

31]. MIA alters microglial activation profiles in the fetal brain and can perturb circuit formation [

32]. Reported effects include changes in microglial transcriptional programs, activation states, cytokine production, synaptic pruning, and motility, any of which may disrupt normal brain development and produce long-lasting neurodevelopmental abnormalities [

33].

Microglia express the IL-17A receptor IL-17RA, and in models of neuroinflammation (e.g., experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and Parkinsonian paradigms), IL-17A drives overexpression of pro-inflammatory mediators in glia and exacerbates pathology [

34,

35]. Complementary in vitro studies likewise show that IL-17A stimulation increases microglial expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

In our laboratory, direct intraventricular administration of recombinant IL-17A to fetal mouse brains revealed robust effects on microglia: cells accumulated predominantly in periventricular zones and in medial cortical regions (including cingulate cortex), and those at the ventricular surface adopted amoeboid morphologies and CD68-positive activated phenotypes [

36,

37]. These findings indicate that IL-17A reconfigures both the activation state and spatial distribution of microglia. Periventricular aggregation of activated microglia could promote excessive phagocytosis of neural progenitors [

38], whereas medial cortical accumulation may influence the formation of long-range commissural connections such as the corpus callosum.

Microglial activation in response to MIA is unlikely to be purely transient. Potential longer-term consequences include altered synapse density, chronic neuroinflammation, shifts in neurotransmitter balance, and dysregulated production of neurotrophic factors. We posit that the convergence of these durable changes contributes to the pathogenesis of neurodevelopmental disorders, and we are continuing to dissect how IL-17A shapes cortical morphogenesis over time.

6. DOHaD and MIA

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) framework posits that the prenatal and early postnatal environment shapes lifelong health and disease risk [

39,

40]. Within this framework, maternal immune activation (MIA) constitutes a salient prenatal environmental exposure. As reviewed above, MIA is associated with increased risk of fetal loss and with neurodevelopmental outcomes—particularly autism spectrum disorder (ASD)—aligning with the DOHaD concept that the fetal immune milieu programs later health trajectories.

The roles of interleukin-17A (IL-17A) and microglia highlighted in this review offer concrete mechanistic inroads for DOHaD. Their influence on fetal cortical development relates not only to phenotypes evident at birth or in early childhood but also to vulnerability to psychiatric conditions across adulthood [

41]. MIA-driven reconfiguration of microglial activation can persist, predisposing the brain to chronic neuroinflammation and potentially increasing the risk of neurodegenerative disease [

42]. More broadly, MIA provides a tractable model for interrogating gene–environment interactions—a core DOHaD tenet—thereby refining the “two-hit” view in which genetic susceptibility and environmental challenges jointly determine developmental trajectories.

Positioned at the nexus of neuroimmunology and developmental neuroscience, MIA research is accelerating our understanding of immune–neural interactions during gestation. It is informing pathophysiology and therapeutic discovery for neurodevelopmental disorders. Ultimately, the significance of this work extends beyond disease-specific mechanisms to the wider DOHaD context of how fetal environments sculpt lifelong health. From a public-health perspective, advancing this knowledge base should catalyze prevention strategies and precision medicine grounded in DOHaD principles.

7. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

Progress in MIA research carries broad clinical implications, including early identification of high-risk pregnancies, development of novel therapeutics, improved infection control during pregnancy, design of early-life intervention programs, and applications to precision medicine. For example, profiling serum IL-17A together with microglial activation markers is a candidate strategy for stratifying neurodevelopmental risk during pregnancy. Therapeutically, IL-17A-neutralizing antibodies and agents that modulate microglial activation represent promising foundations for preventive and disease-modifying approaches. To advance the field, key priorities include:

1. Cytokines beyond IL-17A. Define how IL-6, TNF-α, and other inflammatory mediators contribute to MIA-driven alterations in fetal brain development [

30,

43].

2. Durable circuit effects of microglial activation. Determine how MIA—particularly IL-17A–driven microglial activation—shapes synaptogenesis, circuit remodeling, and network function across development [

44,

45].

3. Critical windows of susceptibility. Pinpoint gestational stages at most significant risk to guide targeted prevention and timing of interventions [

46].

4. Gene–environment interplay. Identify genetic backgrounds that confer heightened vulnerability to MIA and leverage these insights for individualized prevention and treatment [

47].

5. Therapeutic mitigation. Develop and test strategies to blunt MIA sequelae, including IL-17A blockade and microglia-modulating drugs [

48,

49].

6. Translation to humans. Rigorously evaluate the extent to which animal-model findings generalize to human pregnancy and neurodevelopment [

50].

7. Longitudinal follow-up. Conduct long-term cohort studies of MIA-exposed offspring to define trajectories of risk, prognosis, and windows for intervention [

51,

52].

8. Co-exposures and context. Map interactions between MIA and other environmental factors—nutrition, psychosocial stress, and chemical exposures—to capture real-world complexity [

53].

As science advances, ethical and societal questions require parallel attention: clear risk-communication strategies for pregnant individuals and the public, careful evaluation of the ethical acceptability of prenatal immunomodulation, and measures to mitigate anxiety among expectant mothers. Addressing these dimensions will facilitate responsible translation. In tandem with human validation, deeper mechanistic work, and therapeutic development, the field should prioritize returning insights to clinical practice to strengthen prenatal care and support healthy fetal development.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kenyu Nakamura and Kyoko Kishi for their valuable discussions and critical reading of this manuscript. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (KAKENHI Nos. 19K08065, 22K07611), and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas “Multiscale Brain” (No. 19H05201) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology MEXT Japan. T.S. was also supported by the Foundation for Advanced Medical Research, the Naito Foundation, the Takeda Science Foundation, the Kawano Masanori Memorial Public Interest Incorporated Foundation for Promotion of Pediatrics, the Taiju Life Social Welfare Foundation, the Life Science Foundation of Japan, the Nakatomi Foundation, the Mishima Kaiun Memorial Foundation, the Kanehara Ichiro Memorial Foundation for Medical Science and Medical Care, the Foundation for Pharmaceutical Research. Part of this work was supported by the NIBB Collaborative Research Program and Advanced Animal Model Support (16H06276) of Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas to T.S.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Abbreviations

| ASD |

Autism spectrum disorder |

| CDC |

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CD68 |

Cluster of differentiation 68 (marker of activated microglia/macrophages) |

| DOHaD |

Developmental Origins of Health and Disease |

| DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| IL-1β |

Interleukin-1 beta |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IL-17A |

Interleukin-17A. |

| IL-17RA |

Interleukin-17 receptor A |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| MIA |

Maternal immune activation |

| poly(I: C) |

Polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid (viral dsRNA mimetic) |

| RORγt |

Retinoic acid receptor–related orphan receptor gamma t |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| Tg |

Transgenic |

| Th17 |

T helper 17 (cell). |

| TGF-β |

Transforming growth factor beta. |

| TLR3 |

Toll-like receptor 3 |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

References

- Patterson, P.H. Maternal infection and immune involvement in autism. Trends Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, M.L.; McAllister, A.K. Maternal immune activation: Implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Science 2016, 353, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asumi Kubo, A.; Kamiya, S.; Sasaki, T. Effects of Maternal Immune Activation and IL-17A on Abortion. Bio Clinica 2024, 39, 38–40. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, D.L.; Braun, K.V.N.; Baio, J.; Bilder, D.; Charles, J.; Constantino, J.N.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2018, 65, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Bakian, A.V.; Bilder, D.A.; Durkin, M.S.; Esler, A.; et al. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years—Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2021, 70, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knuesel, I.; Chicha, L.; Britschgi, M.; Schobel, S.A.; Bodmer, M.; Hellings, J.A.; Toovey, S.; Prinssen, E.P. Maternal immune activation and abnormal brain development across CNS disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 10, 643–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, G.; Cardenas, I. The immune system in pregnancy: A unique complexity. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010, 63, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, S.; Khan, D.; Kong, E.; Berger, A.; Pollak, A.; Pollak, D.D. The poly(I:C)-induced maternal immune activation model in preclinical neuropsychiatric drug discovery. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 149, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.P.; Li, J.; Garbett, K.; Mirnics, K.; Patterson, P.H. Maternal immune activation alters fetal brain development through interleukin-6. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 10695–10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldenberg, R.L.; Thompson, C. The infectious origins of stillbirth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 189, 861–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, D.B.; Savitz, D.A.; Kramer, M.S.; Gessner, B.D.; Katz, M.A.; Knight, M.; et al. Maternal influenza and birth outcomes: Systematic review of comparative studies. BJOG 2017, 124, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Mascio, D.; Khalil, A.; Saccone, G.; Rizzo, G.; Buca, D.; Liberati, M.; et al. Outcome of coronavirus spectrum infections (SARS, MERS, COVID-19) during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2020, 2, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eaton, W.W.; Mortensen, P.B.; Thomsen, P.H.; Frydenberg, M. Obstetric complications and risk for severe psychopathology in childhood. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, H.J.; Eaton, W.W.; Madsen, K.M.; Vestergaard, M.; Olesen, A.V.; Agerbo, E.; et al. Risk factors for autism: Perinatal factors, parental psychiatric history, and socioeconomic status. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2005, 161, 916–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.K.; Krakowiak, P.; Baker, A.; Hansen, R.L.; Ozonoff, S.; Hertz-Picciotto, I. Preeclampsia, placental insufficiency, and autism spectrum disorder or developmental delay. JAMA Pediatr. 2015, 169, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffen, S.L. Structure and signalling in the IL-17 receptor family. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009, 9, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C. TH17 cells in development: An updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 337–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.I.; McKenzie, B.S.; Zhou, L.; Tadokoro, C.E.; Lepelley, A.; Lafaille, J.J.; et al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 2006, 126, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Heink, S.; Grothe, H.; Guralnik, A.; Reinhard, K.; Elflein, K.; et al. A Th17-like developmental process leads to CD8+ Tc17 cells with reduced cytotoxic activity. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.-J.; Hao, C.-F.; Yi-Lin; Yin, G.-J.; Bao, S.-H.; Qiu, L.-H.; et al. Increased prevalence of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in peripheral blood and decidua in unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion patients. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2010, 84, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Tian, Z.; Wei, H. TH17 cells in human recurrent pregnancy loss and pre-eclampsia. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 11, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-S.; Wu, L.; Tong, X.-H.; Wu, L.-M.; He, G.-P.; Zhou, G.-X.; et al. Study on the relationship between Th17 cells and unexplained recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 65, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tome, S.; Sasaki, T.; Takahashi, S.; Takei, Y. Elevated maternal retinoic acid-related orphan receptor-γt enhances the effect of polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid in inducing fetal loss. Exp. Anim. 2019, 68, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Nagata, R.; Takahashi, S.; Takei, Y. Effects of RORγt overexpression on the murine central nervous system. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2021, 41, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoh, K.; Morito, N.; Ojima, M.; Shibuya, K.; Yamashita, Y.; Morishima, Y.; et al. Overexpression of RORγt under control of the CD2 promoter induces polyclonal plasmacytosis and autoantibody production in transgenic mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2012, 42, 1999–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ayadhi, L.Y.; Mostafa, G.A. Elevated serum levels of interleukin-17A in children with autism. J. Neuroinflammation 2012, 9, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Dang, Y.; Yan, Y. Serum interleukin-17A and homocysteine levels in children with autism. BMC Neurosci. 2024, 25, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Yim, Y.S.; Ha, S.; Atarashi, K.; Tan, T.G.; et al. Maternal gut bacteria promote neurodevelopmental abnormalities in mouse offspring. Nature 2017, 549, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, G.B.; Yim, Y.S.; Wong, H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.V.; et al. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science 2016, 351, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, H.; Czupalla, C.J.; Lee, D.; Chen, M.B.; Burke, A.N.; Zera, K.A.; et al. Aged blood impairs hippocampal neural precursor activity and activates microglia via brain endothelial cell VCAM1. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 988–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salter, M.W.; Stevens, B. Microglia emerge as central players in brain disease. Nat. Med. 2017, 23, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrem, B.E.L.; Domínguez-Iturza, N.; Stogsdill, J.A.; Faits, T.; Kim, K.; Levin, J.Z.; et al. Fetal brain response to maternal inflammation requires microglia. Development 2024, 151, dev202252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozaki, K.; Kato, D.; Ikegami, A.; Hashimoto, A.; Sugio, S.; Guo, Z.; et al. Maternal immune activation induces sustained changes in fetal microglia motility. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das Sarma, J.; Ciric, B.; Marek, R.; Sadhukhan, S.; Caruso, M.L.; Shafagh, J.; et al. Functional interleukin-17 receptor A is expressed in central nervous system glia and upregulated in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neuroinflammation 2009, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Z.; Wang, C.; Zepp, J.; Wu, L.; Sun, K.; Zhao, J.; et al. Act1 mediates IL-17–induced EAE pathogenesis selectively in NG2+ glial cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1401–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, T.; Tome, S.; Takei, Y. Intraventricular IL-17A administration activates microglia and alters their localization in the mouse embryo cerebral cortex. Mol. Brain 2020, 13, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thion, M.S.; Ginhoux, F.; Garel, S. Microglia and early brain development: An intimate journey. Science 2018, 362, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.L.; Martínez-Cerdeño, V.; Noctor, S.C. Microglia regulate the number of neural precursor cells in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 4216–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, P.D.; Hanson, M.A.; Buklijas, T. A conceptual framework for the developmental origins of health and disease. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2010, 1, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M.A.; Gluckman, P.D. Developmental origins of health and disease—global public health implications. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2015, 29, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbo, S.D.; Schwarz, J.M. Early-life programming of later-life brain and behavior: A critical role for the immune system. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2009, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattei, D.; Ivanov, A.; Ferrai, C.; Jordan, P.; Guneykaya, D.; Buonfiglioli, A.; et al. Maternal immune activation results in complex microglial transcriptome signature in the adult offspring that is reversed by minocycline treatment. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalmau, I.; Finsen, B.; Zimmer, J.; González, B.; Castellano, B. Development of microglia in the postnatal rat hippocampus. Hippocampus 1998, 8, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C.J.; Russell, K.I.; Wang, Y.T.; Christie, B.R. Contribution of NR2A and NR2B NMDA subunits to bidirectional synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus in vivo. Hippocampus 2006, 16, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argaw, A.T.; Asp, L.; Zhang, J.; Navrazhina, K.; Pham, T.; Mariani, J.N.; et al. Astrocyte-derived VEGF-A drives blood–brain barrier disruption in CNS inflammatory disease. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2454–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Oppenheim, J.J. Th17 cells and Tregs: Unlikely allies. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014, 95, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, Y.; Mera, T.; Wang, L.; Faustman, D.L. Homogeneous expansion of human T-regulatory cells via tumor necrosis factor receptor 2. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedoszytko, B.; Lange, M.; Sokołowska-Wojdyło, M.; Renke, J.; Trzonkowski, P.; Sobjanek, M.; et al. The role of regulatory T cells and genes involved in their differentiation in pathogenesis of selected inflammatory and neoplastic skin diseases. Part I: Treg properties and functions. Postepy Dermatol. Alergol. 2017, 34, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajeeth, C.K.; Kronisch, J.; Khorooshi, R.; Knier, B.; Toft-Hansen, H.; Gudi, V.; et al. Effectors of Th1 and Th17 cells act on astrocytes and augment their neuroinflammatory properties. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajeeth, C.K.; Löhr, K.; Floess, S.; Zimmermann, J.; Ulrich, R.; Gudi, V.; et al. Effector molecules released by Th1 but not Th17 cells drive an M1 response in microglia. Brain Behav. Immun. 2014, 37, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelhardt, B.; Ransohoff, R.M. Capture, crawl, cross: The T cell code to breach the blood–brain barriers. Trends Immunol. 2012, 33, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipollini, V.; Anrather, J.; Orzi, F.; Iadecola, C. Th17 and cognitive impairment: Possible mechanisms of action. Front. Neuroanat. 2019, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, A.; Ciric, B. Role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of CNS inflammatory demyelination. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 333, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).