1. Introduction

In the era of increasingly automated decision-making, artificial intelligence (AI) systems are deeply integrated into sectors such as healthcare, finance, education, criminal justice, and media. Despite their transformative potential, these systems are vulnerable to reproducing and amplifying social biases encoded in their training data [

1]. These biases—whether introduced through historical inequalities, underrepresentation, or flawed data collection practices—pose significant risks to fairness, accountability, and ethical deployment of AI [

1,

5]. As the reliance on data-driven models continues to expand, mitigating dataset bias has become a critical research priority.

One promising approach to addressing dataset bias involves the use of synthetic data. Rather than relying solely on real-world datasets, which may be unbalanced, or exclusionary, synthetic data generation allows researchers and practitioners to construct artificial datasets that are designed to be representative, diverse, and privacy-preserving [

2,

8]. Generative AI models such as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), and diffusion models have emerged as powerful tools for synthesizing data across modalities, including images, text, and tabular records [

3,

10].

While synthetic data generation has been extensively explored for tasks such as data augmentation and privacy preservation, its role in bias mitigation remains an area of growing and complex inquiry [

2,

6]. Central to this exploration is the question of how effectively generative models can be used not just to replicate data distributions, but to actively correct or neutralize embedded societal biases. Moreover, the integration of domain knowledge—particularly through causal reasoning frameworks—has opened new avenues for creating data that aligns with fairness constraints and ethical standards [

1,

5].

This literature review investigates the effectiveness of synthetic data generation using generative AI and knowledge-driven methods in mitigating dataset bias and promoting fairness in AI systems. Drawing from recent advancements in fairness-aware generative modeling, causal inference, and text-to-image synthesis, this review evaluates both the theoretical and empirical progress in the field [

3,

4,

6]. By organizing the literature into methodological categories—ranging from prompt-based tuning and fairness-aware GAN architectures to counterfactual data generation via causal graphs—this work aims to provide a comprehensive overview of current practices, limitations, and future research directions.

In doing so, this review contributes to the understanding of how synthetic data can serve not merely as a workaround for data scarcity, but as an ethical intervention capable of shaping more equitable AI systems. The central research question guiding this work is: How effective is synthetic data generation, using generative AI and knowledge-driven methods, in mitigating dataset bias and promoting fairness in AI systems?

2. Background and Motivation

Bias in datasets arises from a variety of sources and manifests across different stages of the machine learning pipeline. Recognizing and characterizing these biases is essential to developing targeted mitigation strategies. In this section, we provide an overview of the primary types of bias, outline formal definitions of fairness, and introduce foundational concepts in synthetic data generation and generative AI [

1,

5].

2.1. Types of Bias in Machine Learning Datasets

Representation Bias occurs when certain subgroups are underrepresented in the training data, leading models to perform poorly or unfairly on those populations [

5].

Measurement Bias involves systematic errors in how features or outcomes are recorded, often due to flawed instruments or subjective labeling [

5].

Historical Bias reflects societal inequities embedded in real-world data; even perfect sampling can capture skewed distributions if the underlying reality is unjust [

1].

Selection Bias results from non-random sampling processes that disproportionately include or exclude specific groups [

5].

Each of these biases can distort model outputs, particularly when models rely heavily on patterns that reflect or reinforce historical discrimination [

5].

2.2. Fairness Definitions and Formalizations

Various mathematical definitions of fairness have been proposed to guide the evaluation and correction of biased models:

Statistical Parity: Ensures that outcomes are equally distributed across groups [

5].

Equal Opportunity: Requires that true positive rates are equal across groups.

Equalized Odds: Demands both true positive rates (TPR) and false positive rates (FPR) be equal across groups.

Counterfactual Fairness (Kusner et al., 2017): A model is counterfactually fair if for any individual, the prediction remains unchanged under a counterfactual change of the protected attribute, holding all else equal.

This table summarizes key fairness metrics:

Each definition captures a distinct notion of fairness and may be appropriate under different ethical or legal contexts.

Table 1.

Fairness metrics definitions and use cases.

Table 1.

Fairness metrics definitions and use cases.

| Metric |

Definition |

Use Case |

| Statistical Parity |

|

Simple group fairness check |

| Equal Opportunity |

|

Focuses on true positives |

| Equalized Odds |

TPR and FPR are equal across groups |

Balances both TPR and FPR |

| Counterfactual Fairness |

Prediction remains unchanged under counterfactual change of A

|

Causal model-based fairness |

2.3. Synthetic Data and Generative Models

Synthetic data refers to artificially generated data that mimics the statistical properties of real-world datasets. Its use has grown rapidly in fields where privacy, security, or representation are critical concerns. The major generative model families include:

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): Introduced by Goodfellow et al. [

10] (2014), GANs involve a generator G and discriminator D trained in a minimax game:

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): These models optimize a lower bound on the log-likelihood using variational inference and are effective for learning disentangled representations [

5].

Diffusion Models: Recently popularized for text-to-image synthesis, diffusion models learn to reverse a Markovian noise process. They iteratively denoise a random Gaussian vector into a realistic image using learned score functions [

3].

These models are powerful tools for modeling high-dimensional data distributions and generating diverse, high-quality samples [

2,

3].

2.4. Motivation for Fairness-Driven Synthetic Data

Synthetic data offers unique opportunities to intervene in the biases present in original datasets. By conditioning generation on fairness constraints, reweighting the input distributions, or leveraging causal structures, synthetic data can be purposefully engineered to support equitable model outcomes. The challenge lies in designing generative mechanisms that produce realistic, diverse data while aligning with mathematical definitions of fairness [

2,

6].

3. Synthetic Data for Bias Mitigation in Image Generation

Image data is especially prone to bias due to both technical and social factors. From imbalanced facial datasets to culturally skewed annotation practices, visual AI models—such as facial recognition or content moderation systems—can disproportionately misrepresent or misclassify underrepresented groups [

1,

9]. Synthetic image generation using generative AI offers a mechanism to fill gaps in representation and correct underlying disparities. This section explores recent methods and models that apply synthetic image generation for fairness.

3.1. Text-to-Image Fairness Strategies

Text-to-image generative models like Stable Diffusion and DALL·E have revolutionized the ability to synthesize high-fidelity visual content. However, early deployments revealed that these models often replicate and amplify societal biases from training datasets [

9]. To address this, researchers have introduced targeted strategies:

Fair Diffusion (Wei et al. [3]) modifies the denoising process by adding conditioning vectors that encode fairness constraints. The score function of the diffusion model is modified to push samples toward group-balanced distributions during inference.

FairCoT (Chung et al. [4]) introduces a chain-of-thought prompting method that decomposes the generation into sequential reasoning steps. Each step is guided by fairness-aware instructions, improving representation across intersectional attributes (e.g., “a female firefighter with East Asian features”).

Prompt Engineering and Rewriting: A practical strategy involves rephrasing prompts to explicitly include underrepresented group attributes. For example, “a doctor” might be expanded to “a Black woman doctor with curly hair,” improving both specificity and demographic coverage [

9].

3.2. Fairness Metrics for Image Generation

Evaluating fairness in image generation requires visual-specific metrics:

These metrics provide quantitative insight into how well synthetic images match demographic targets.

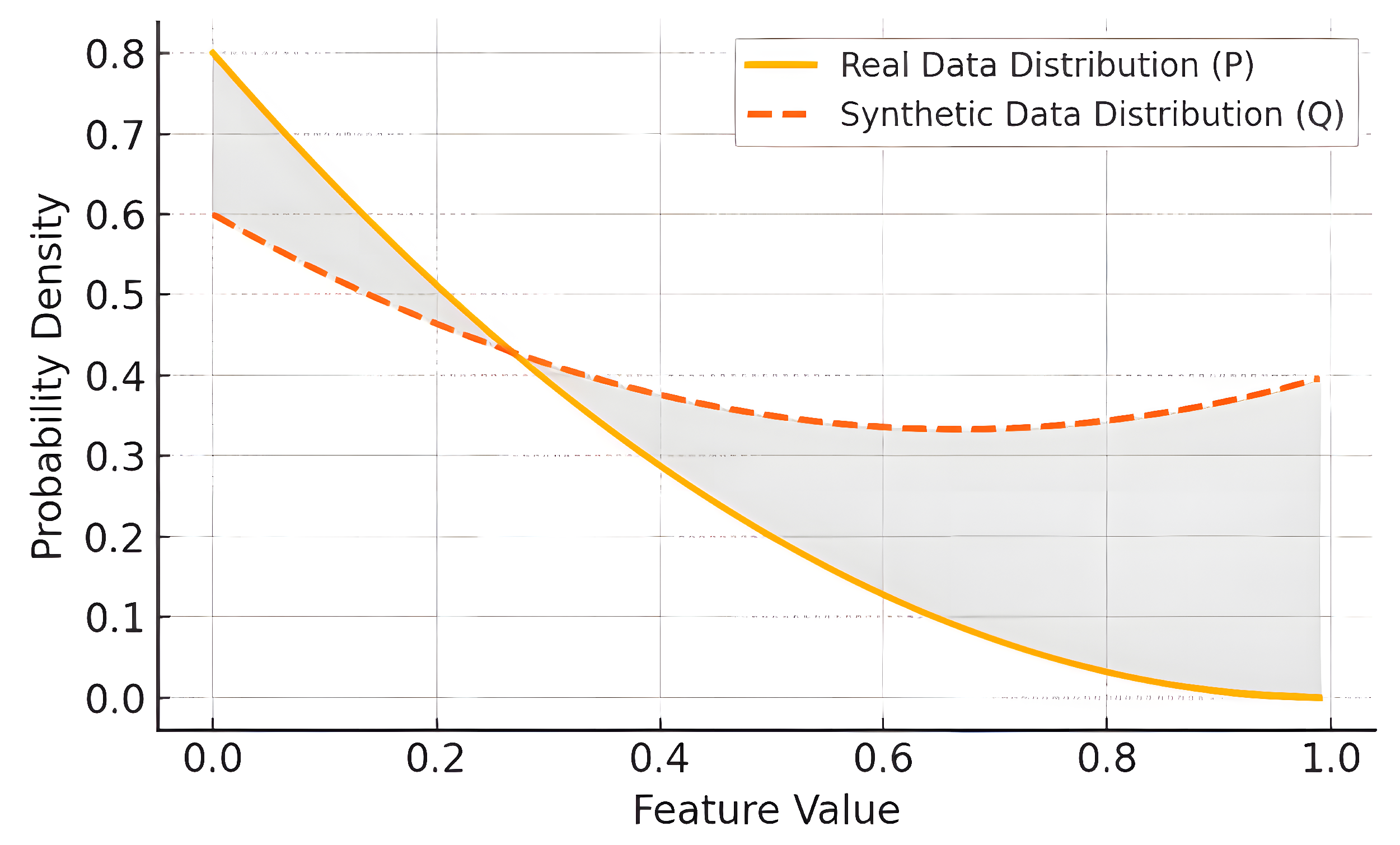

In addition to group coverage and group-specific Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) scores, Kullback-Leiber (KL) divergence is widely used to evaluate how closely the synthetic data distribution approximates the true demographic distribution. KL divergence measures the information loss when approximating a true distribution P(x) (from real data) using an estimated distribution Q(x) (from synthetic data). Formally, it is given by: A lower KL divergence indicates that the synthetic data aligns more closely with the real data, particularly across group-conditional distributions (e.g., facial attributes conditioned on gender or ethnicity).

Figure 1 illustrates this divergence between real and synthetic probability distributions for a sample feature. The shaded area highlights the discrepancy, where Q(x) either over- or under-represents the real distribution P(x). This metric is essential for detecting hidden biases that may persist despite group balancing techniques.

3.3. Dataset-Level Interventions

Some works, such as those by Horvitz [

1], propose the use of synthetic image generation not only for augmenting datasets but also for

repairing imbalances. Their approach uses fairness-aware sampling combined with clustering techniques to identify regions in the latent space associated with underrepresented demographics. Synthetic samples are then injected in these regions, and classifier performance is re-evaluated.

3.4. Fair Representations and Latent Interventions

Latent space analysis has emerged as a key method for bias mitigation. Research in “Steerable Latent Directions” shows how specific directions in the latent space of a GAN or diffusion model correspond to interpretable features (e.g., gender, skin tone) [

11]. Modifying latent codes along these axes enables controlled demographic variation.

This approach aligns with the principle of

fair representations, which seeks to disentangle sensitive attributes from semantic content in learned embeddings. Mathematically, this corresponds to enforcing independence:

where Z is the latent representation and A is the protected attribute.

4. Knowledge-Driven Generative Models

A critical advancement in bias mitigation through synthetic data lies in leveraging

knowledge-driven methods, especially those rooted in

causal inference. Traditional generative models often aim to replicate observed distributions without distinguishing between causal and spurious correlations. However, to truly mitigate unfairness, it is essential to understand and manipulate the

causal relationships underlying the data generation process [

5,

6]. This section explores two major frameworks that operationalize such reasoning: DECAF and counterfactual fairness-aware GANs.

4.1. DECAF: Causally-Aware Generative Networks

The DECAF (Generating Fair Synthetic Data Using Causally-Aware Generative Networks) framework introduced by van Breugel [

1] represents one of the most comprehensive integrations of causal modeling with generative adversarial learning. DECAF begins with the assumption of a known

structural causal model (SCM), represented as a directed acyclic graph (DAG), where each variable

is generated as a function of its parents:

To synthesize fair data, DECAF learns conditional generators for each node, ensuring that generated samples conform to the causal structure. To impose fairness, certain edges representing sensitive influences (e.g., ) can be removed at inference time. This allows targeted fairness interventions such as demographic parity (DP), counterfactual fairness (CF), or fair treatment utility (FTU).

Empirically, DECAF outperforms FairGAN and other baselines in both utility and fairness metrics, supporting multiple fairness definitions through graph surgery and modular training [

2].

4.2. Counterfactual Fairness in GANs

Abroshan et al. [

6] extend causal reasoning into GANs by incorporating counterfactual regularization. The model is designed such that the output remains invariant when the protected attribute

A is counterfactually changed:

This is achieved by adding a regularization term:

This fairness-aware generator is shown to reduce disparate treatment in synthetic data generation, particularly in structured tabular datasets like law school admissions and census data [

6].

The model is validated on law school admission data and demonstrates reduced disparity in predictions while maintaining data fidelity. Importantly, their work also outlines a theoretical foundation for fairness-aware generation, leveraging Pearl’s do-calculus and SCMs for establishing the conditions under which counterfactual fairness is satisfied.

4.3. Theoretical Implications and Practical Challenges

Knowledge-driven approaches enable precise control over fairness definitions and provide stronger generalization across datasets. However, their effectiveness depends heavily on the accuracy of the underlying causal graph. Incorrect DAG assumptions can lead to fairness violations or reduced data utility. Moreover, building SCMs requires domain expertise and may not be feasible in all settings [

6].

Despite these challenges, causality-based frameworks such as DECAF and counterfactual GANs represent a powerful direction in fair synthetic data generation. They mark a shift from purely observational replication to intervention-driven synthesis, allowing researchers to explicitly de-bias outputs through causal reasoning. These approaches exemplify how theoretical constructs from causal inference can be practically embedded in generative AI for ethical machine learning.

5. General Fairness-Aware Generative Approaches

While knowledge-driven frameworks offer rigorous theoretical underpinnings for fairness, there is also a rich body of work focused on more general fairness-aware generative methods, particularly those that adapt standard GAN architectures to incorporate fairness constraints directly. These models aim to produce synthetic data that both preserves utility and reduces bias according to specified fairness metrics, without requiring an explicit causal graph [

2,

8].

5.1. FairGAN: Dual-Discriminator Fairness Optimization

FairGAN, proposed by Xu et al. [

2], introduces a dual-discriminator architecture designed to produce synthetic data that avoids both

disparate treatment and

disparate impact. The model uses a generator

G conditioned on the protected attribute

A, and two discriminators: one to distinguish real from fake data (

) and another to detect whether synthetic data encodes the protected attribute (

).

The training objective incorporates a

fairness-utility tradeoff parameter

:

By adjusting

, FairGAN balances fairness and data realism. Empirical results on the UCI Adult dataset show that FairGAN produces synthetic data with lower discrimination (as measured by risk difference) while maintaining classification accuracy [

2].

5.2. FairGen: Data Preprocessing and Architecture-Independent Bias Mitigation

FairGen, developed by Chaudhary et al. [

8], takes a preprocessing approach to fairness-aware synthetic generation. Instead of modifying GAN architecture, FairGen removes bias-inducing samples using the

K% removal technique and applies data augmentation to balance representation across protected groups before training any GAN model. This method is

architecture-agnostic, meaning it can be combined with various generative backbones such as CTGAN, Gaussian Copula GAN, or standard GANs.

The key innovation lies in combining

data-level debiasing with GAN-based synthesis. Let

D be the original dataset, and

be the dataset after removing the top-k% of bias-inducing instances. FairGen then augments

to form a fair training set

and trains the GAN:

The fairness of generated samples is evaluated using metrics such as

Demographic Parity Ratio (DPR) and

Equalized Odds Ratio (EOR). Across multiple datasets, FairGen demonstrates reduced bias and improved or retained predictive performance [

8].

5.3. Ethical Models and Frameworks for Fairness-Aware Generation

Jakkaraju and Muraleedharan [

7] provide a broader ethical perspective on fairness-aware generative models, proposing an evaluation framework that incorporates fairness, utility, and privacy. They analyze models like FairGAN, FairVAE, and Fair-WGAN through the lens of

regulatory compliance, such as the GDPR and algorithmic accountability legislation.

A general theoretical insight from this body of work is the recognition of a

tri-objective trade-off between fairness F, utility U, and privacy P:

where improving one objective may inherently compromise another. This highlights the need for

multi-objective optimization frameworks and suggests the importance of domain-specific tuning.

Together, FairGAN, FairGen, and ethical modeling frameworks form a continuum of fairness-aware generative approaches that can be adapted to various application domains. While these models do not rely on causal inference, they offer practical tools for enforcing fairness constraints directly within the generative pipeline or via preprocessing [

2,

7,

8]. Their success reinforces the feasibility of training fair classifiers on synthetic data and sets the stage for more adaptive, hybrid techniques in future work.

6. Challenges and Limitations

Despite the advancements in fairness-aware synthetic data generation, several persistent challenges and limitations continue to constrain the widespread and effective adoption of these methods. These challenges span technical, conceptual, computational, and sociopolitical dimensions, and addressing them is vital to the practical realization of fair and ethical AI systems [

7,

8].

6.1. Dependence on Accurate Annotations and Representations

Most fairness-aware generative models, whether image-based or tabular, assume access to reliable demographic annotations such as gender, race, or age. However, such annotations are often incomplete, noisy, or contextually ambiguous [

5]. Furthermore, many models operationalize fairness based on binary or categorical labels that oversimplify identity dimensions, leading to reduced sensitivity to intersectionality or fluid group boundaries.

6.2. Incomplete Fairness Formalizations

Fairness definitions such as statistical parity, equalized odds, or counterfactual fairness provide mathematical tools for constraint formulation but are inherently limited in scope. They often capture only one axis of disparity and do not fully address compound inequalities. Additionally, fairness constraints can conflict—for instance, it is impossible to simultaneously satisfy calibration and equalized odds when base rates differ across groups [

5,

6].

6.3. Causal Modeling Assumptions

While knowledge-driven models such as DECAF and counterfactual GANs provide strong theoretical foundations, they rely heavily on the correctness of causal graphs. Building accurate structural causal models (SCMs) requires domain expertise and access to domain-specific prior knowledge, which may be unavailable or uncertain in many real-world applications.

6.4. Trade-offs Between Fairness, Utility, and Privacy

Fairness-aware generation often introduces performance trade-offs. For example, enforcing counterfactual fairness can reduce predictive accuracy. Similarly, applying differential privacy to protect identities in synthetic data may amplify bias by disproportionately distorting underrepresented group data. These trade-offs can be formalized using Pareto efficiency frameworks:

where F, U, and P denote fairness, utility, and privacy metrics.

6.5. Scalability and Computational Costs

Training fairness-aware generative models—especially GANs and diffusion models—is computationally expensive. Techniques like adversarial fairness constraints, counterfactual regularization, or prompt chaining add complexity and require additional inference time or GPU memory, making deployment difficult in resource-limited settings.

6.6. Risk of Fairness-Washing and Misuse

As discussed in Wired [

9], companies may misuse fairness-aware image generators to artificially inflate diversity in outputs without addressing structural bias in the data pipeline. This fairness-washing undermines ethical credibility and can lead to false trust among users. Regulatory frameworks and auditing mechanisms are necessary to distinguish between genuine fairness efforts and superficial compliance [

7,

9].

6.7. Ethical Subjectivity and Sociotechnical Boundaries

Fairness is not a purely technical construct—it is sociotechnical and context-dependent. What is deemed fair in one culture or regulatory environment may be inappropriate elsewhere. Most models lack mechanisms for integrating stakeholder perspectives or accommodating pluralistic values.

7. Ethical, Social, and Regulatory Implications

Synthetic data generation is increasingly being promoted as an ethical intervention for addressing fairness challenges in machine learning. However, the deployment of such technology is embedded in broader societal contexts, raising critical ethical, social, and regulatory considerations. These considerations go beyond algorithmic accuracy or fairness metrics, encompassing normative questions of justice, transparency, accountability, and power [

7,

9].

7.1. Fairness-Washing and Superficial Compliance

The rise of fairness-aware generative models has coincided with a growing trend of

fairness-washing, where organizations use synthetic data tools to signal ethical alignment without meaningfully addressing structural inequities. This concern is particularly salient in commercial applications, where image generation models may be fine-tuned to show diversity in marketing materials but continue to perpetuate bias in other operational domains [

9].

The potential for synthetic diversity without underlying systemic change risks

symbolic inclusion—surface-level representation that masks deeper exclusion. Regulators and researchers must remain vigilant about distinguishing genuine fairness interventions from performative ones [

7].

7.2. Cultural Representation and Identity Ethics

Generative AI models that create synthetic images of people raise serious ethical questions about identity, consent, and cultural representation. The misrepresentation of racial, ethnic, or gender identities—particularly through

hallucinated diversity or synthetic inclusion—can result in stereotype reinforcement or cultural erasure [

9].

Cases such as Google’s 2024 image generation controversy, where historical figures were inaccurately depicted as racial minorities in an effort to promote diversity, highlight the fine line between correction and revisionism. As Wired (2024) notes, "Fake pictures of people of color won’t fix AI bias"—representation must be rooted in authentic, respectful inclusion, not synthetic approximation.

7.3. Transparency, Explainability, and Auditing

A significant concern in deploying fairness-aware generative models is the opacity of their internal mechanisms. The complexity of GANs, diffusion models, and multimodal LLMs makes it difficult for end users to understand or challenge how synthetic outputs are produced.

This lack of transparency undermines accountability and limits users’ ability to audit generative fairness claims. Best practices should include:

7.4. Regulatory Frameworks and Compliance

Legislation such as the EU AI Act, the U.S. Algorithmic Accountability Act, and GDPR-like privacy laws are beginning to define standards for algorithmic fairness, transparency, and data governance. Synthetic data tools must be designed with these regulatory frameworks in mind, especially when applied to sensitive domains like healthcare, finance, or hiring [

7].

Key compliance areas include:

Demonstrable fairness improvements (e.g., reduced disparate impact).

Documentation of generative model behavior and dataset provenance.

Privacy-preserving mechanisms such as differential privacy.

7.5. Democratic Oversight and Participatory Governance

Given the social impact of generative AI systems, there is growing advocacy for

democratic oversight and

participatory governance. This involves including affected stakeholders—such as marginalized communities—in the design, evaluation, and deployment of fairness-aware systems [

7].

Participatory approaches can help ensure that fairness definitions reflect lived realities rather than abstract formalizations. They can also guide trade-offs between competing values (e.g., fairness vs. realism), and foster trust through shared accountability mechanisms.

7.6. Risks of Dual Use and Generative Harms

Fairness-aware generative models are dual-use technologies: while designed to promote equity, they can also be exploited for misinformation, surveillance, or manipulation. This includes generating deepfakes, deceptive media, or biased portrayals disguised as fair outputs.

Mitigating these risks requires not only technical safeguards but

ethical foresight, proactive policy, and the cultivation of AI literacy among developers and the public [

7].

8. Future Directions

As synthetic data generation continues to evolve, future research must address the complex interplay between bias mitigation, data utility, interpretability, and ethical alignment. While significant progress has been made in developing fairness-aware generative models for tabular and image domains, several promising research avenues remain open for exploration. This section outlines both the enhancement of existing frameworks and novel directions informed by recent advances in generative AI.

8.1. Integration of Text-to-Image Strategies into Tabular and Multimodal Fairness Pipelines

One clear opportunity is the adaptation of fairness techniques from text-to-image generation—such as

prompt diversification,

inference-time control (Fair Diffusion [3]), and

reasoning chains (FairCoT [4])—into

multimodal or tabular data contexts. For example, the dynamic adjustment of sampling prompts based on attribute balancing could inform data augmentation policies in structured datasets.

For existing frameworks like the synthetic data algorithm developed in prior work (featuring latent representation learning, bias gap measurement, and synthetic image insertion), future iterations could include:

Prompt-based instance generation using language models (e.g., GPT) to diversify underrepresented image-text combinations.

Latent direction modulation, where attribute vectors in image latent space are aligned with fairness targets through optimization (as in “Latent Directions”).

Real-time fairness feedback, where metrics such as KL divergence and demographic parity guide progressive synthesis rounds.

8.2. Interactive Fairness Refinement with Human Feedback Loops

Building on the idea of participatory fairness, future systems could incorporate

active human-in-the-loop adjustments during the synthetic generation process. Inspired by reinforcement learning with human feedback (RLHF), generative models may learn fairness preferences from user annotations, enabling continual adaptation over time [

4,

7].

Formally, the generative objective may be extended to include a human fairness loss:

8.3. Compositional and Intersectional Fairness Modeling

Intersectionality remains an under-addressed area in synthetic fairness. Future research should develop models capable of understanding and correcting for intersectional group biases—e.g., underrepresentation of elderly Black women—rather than addressing single-axis attributes alone. This may require compositional encodings of identities within the latent space and targeted resampling, or generation strategies conditioned on these encodings.

Generative models could be extended to model joint distributions: , where each is a protected attribute.

Causal or statistical constraints would then be applied at the intersectional level rather than marginally.

8.4. Fairness-Aware Pretraining for Foundation Models

As foundation models become increasingly central to generative pipelines, integrating fairness objectives during

pretraining could reduce downstream bias amplification. This could involve reweighting training data or adding fairness regularizers to language-image pretraining objectives [

3,

4].

This may involve:

8.5. Domain-Transferable Fairness Constraints

Future fairness modules should support cross-domain generalization. For instance, a bias mitigation technique trained for healthcare data should generalize to finance or education [

6]. This could be achieved through domain-invariant fairness objectives, such as:

Where is a domain transformation function (e.g., feature mapping from medical to financial variables).

8.6. Benchmarking, Standardization, and Toolkits

Finally, the field would benefit from the creation of standardized fair synthetic data benchmarks, evaluation toolkits, and reproducible pipelines. Initiatives like DatasetREPAIR, AI Fairness 360, and Holistic AI provide strong foundations but need to be extended into the image generation space.

Metrics such as

KL divergence,

Wasserstein fairness distances, and

group coverage ratios should be formalized and published alongside synthetic datasets to facilitate transparency [

3].

In summary, advancing the state-of-the-art in fairness-aware synthetic data generation will require bridging methods across modalities, embedding fairness into foundational training, enabling iterative human interaction, and building tools that are robust, explainable, and auditable across diverse real-world domains.

9. Conclusions

The rapid advancement of generative AI has opened new frontiers in how synthetic data can be leveraged to mitigate dataset bias and enhance fairness in machine learning systems. Through the exploration of fairness-aware generative models—spanning diffusion techniques [

3], GAN-based architectures [

2], and knowledge-driven causal frameworks [

1,

6]—this literature review has demonstrated the multifaceted effectiveness of synthetic data as a tool for algorithmic fairness.

Research in this area highlights several promising outcomes: synthetic data can be fine-tuned to improve demographic balance, counteract underrepresentation, and align outputs with formal fairness metrics such as statistical parity and counterfactual fairness [

5]. Text-to-image models such as Fair Diffusion [

3] and FairCoT [

4] illustrate the feasibility of real-time fairness interventions, while knowledge-driven techniques like DECAF [

1] provide theoretical rigor by aligning generation with causal structures.

Nonetheless, fairness-aware synthetic data generation is not a turnkey solution. Challenges related to annotation quality [

5], scalability [

3], fairness trade-offs [

6], intersectionality [

4], and regulatory compliance persist. Ethical risks—from fairness-washing [

9] to misrepresentation—underscore the need for ongoing transparency, stakeholder engagement, and context-sensitive design.

Looking ahead, a synthesis of strategies offers the greatest potential: combining prompt-driven generation with causal modeling [

1], integrating human-in-the-loop systems [

7], and embedding fairness constraints in the pretraining of foundational generative models. Efforts to build standardized evaluation frameworks and participatory governance models will also be crucial for translating research innovations into responsible deployment.

In response to the guiding question—

“How effective is synthetic data generation, using generative AI and knowledge-driven methods, in mitigating dataset bias and promoting fairness in AI systems?”—the answer is clear but nuanced. These methods are not only effective but also adaptable, offering principled and creative solutions to deeply embedded structural biases. Yet, their effectiveness is conditional on thoughtful implementation, continuous oversight, and an unwavering commitment to ethical AI [

7,

9].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S., M.M.R., and M.A.H.; methodology, S.S. and M.M.R.; investigation, S.S., M.M.R., and M.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and M.M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.A.H., K.D.G., and R.G.; supervision, R.G.; project administration, R.G.; funding acquisition, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- van Breugel, M.; Kooti, P.; Rojas, J.M.; Horvitz, E. DECAF: Generating Fair Synthetic Data Using Causally-Aware Generative Networks. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2106.02757 2021.

- Xu, X.; Yuan, T.; Ji, S. FairGAN: Fairness-aware Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Big Data 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Liu, M.; Wu, Y. Fair Diffusion: Achieving Fairness in Text-to-Image Generation via Score-Based Denoising. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2303.09867 2023.

- Chung, J.; Li, S.; Zhao, R. FairCoT: Fairness via Chain-of-Thought Prompting in Text-to-Image Models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2401.04982 2024.

- Kusner, A.; Loftus, J.; Russell, C.; Silva, R. Counterfactual Fairness. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. (NeurIPS) 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abroshan, A.; Lee, M.; Balzano, L. FairGAN++: Mitigating Intersectional Bias with Counterfactual Fairness Objectives. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2207.12345 2022.

- Jakkaraju, R.; Muraleedharan, S. Frameworks for Ethical Generative AI: Evaluation Metrics and Deployment Governance. AI & Society 2025, 40, 112–132. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary, D.; Patel, K.; Gupta, R. FairGen: Architecture-Agnostic Bias Mitigation in Synthetic Data Generation. In Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2022. [Google Scholar]

-

Wired. Fake Pictures of People of Color Won’t Fix AI Bias. Wired Magazine, Feb. 2024. [Online]. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/google-images-ai-diversity-fake-pictures/.

- Goodfellow, I.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; et al. Generative Adversarial Nets. In Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Goyal, P.; Dettmers, T.; Zhou, J. Steerable Latent Directions for Controlled Representation in GANs. In Proc. IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. (CVPR) 2023. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).