1. Introduction

In recent years, sustainable supply chain management has evolved rapidly, driven by rising CEA and the growing need for businesses to integrate environmental considerations into product design, sourcing, and marketing. Retailers have emerged as pivotal actors in this transition, leveraging SB, also known as private labels, not only for price competitiveness but also for quality and sustainability differentiation (Gielens et al., 2021). Recent figures underscore the market relevance of SB-NB competition: in 2024, U.S. store brand sales reached USD 271 billion, accounting for 20.7% of dollar share and 23.1% of unit share, with sales growth outpacing national brands (PLMA, 2025). Moreover, consumer behavior shifts during the COVID-19 pandemic have had lasting effects; Mookherjee et al. (2024) showed that greater availability and reliability of SBs during supply shortages increased perceived brand helpfulness, fostering long-term loyalty and sustaining SB growth in the post-pandemic period. These trends confirm the strategic importance of understanding competitive dynamics between SBs and NBs in sustainable supply chains.

Extensive research has examined SB-NB competition from multiple perspectives, including pricing, brand positioning, and channel management.

From the consumer perception and brand image perspective, Collins-Dodd and Lindley (2003) found that store image and SB attitudes significantly influence consumer perceptions, while Diallo (2012) highlighted the combined influence of retailer brand image and price positioning on purchase intentions. Huang and Feng (2020) further demonstrated that a money-back guarantee can enhance SB competitiveness by strengthening consumer trust.

From the pricing and channel management perspective, Kurata et al. (2007) investigated multi-channel pricing, showing that balanced retail price changes can benefit both brands. Cheng et al. (2021) analyzed a three-tier SB supply chain, revealing mutual effects between SB and NB pricing. Li and Chen (2018) examined the timing of pricing decisions and showed that early commitments can reallocate bargaining power among retailers, suppliers, and the overall supply chain.

From the supply chain structure and coordination perspective, Wei and Zhao (2011) utilized game theory to determine optimal internal pricing, retail prices, and remanufacturing proportions in both centralized and decentralized closed-loop supply chains, highlighting how coordination mechanisms can improve profitability. Wu et al. (2012) analyzed the impact of commodity substitutability on equilibrium quantities under different power structures in a supply chain with two retailers and one supplier, showing that higher substitutability intensifies competition and alters optimal pricing strategies. Similarly, Huang et al. (2016) investigated pricing and cooperation in a two-level supply chain with a common manufacturer and duopoly retailers, finding that cooperative arrangements outperform purely competitive strategies in terms of profit.

From the policy and environmental sustainability perspective, Madani and Rasti-Barzoki (2017) developed a mathematical model for energy price management under government tariffs, demonstrating the influence of policy instruments on pricing and supply chain performance. Jamali and Rasti-Barzoki (2018) examined green and non-green product pricing in chain-to-chain competitive dual-channel supply chains, revealing that environmental positioning can shift market share and profitability. Ranjan and Jha (2019) proposed pricing and coordination strategies for dual-channel supply chains that integrate green quality and sales effort, highlighting trade-offs between environmental investment and marketing incentives. Ranjbar et al. (2020) explored conflicting recycling systems in competitive closed-loop supply chains, identifying how competition between recycling channels impacts both pricing and collection performance. Looking ahead, Ndlovu (2024) examined the evolving "battle fronts" between PLBs and NBs, identifying future areas of competitive focus such as strategic collaborations, diversified product lines, and new pricing models in response to market transitions.

Collectively, these studies provide valuable insights into pricing strategies under diverse competitive and structural conditions. However, they predominantly emphasize price, channel configuration, and in some cases product quality or remanufacturing, without explicitly incorporating environmental differentiation, for example, asymmetries in environmental investment between competing products, or the influence of CEA on optimal pricing and investment decisions. This omission limits their direct applicability to contexts where sustainability considerations substantially shape consumer behavior and supply chain strategy.

Parallel literature on CEA and green supply chains provides complementary insights. Liu et al. (2012) developed a two-stage supply chain model to quantify how CEA influences optimal pricing decisions and environmental improvement levels, finding that higher CEA incentivizes greater green investment and supports higher selling prices. Zhang et al. (2015) examined the role of CEA in determining order volumes and channel realignment between competing products, showing that increased CEA can shift demand toward greener offerings and prompt supply chain restructuring. Yang et al. (2017) analyzed benefit-sharing contracts under carbon tax policies, demonstrating how first-mover advantages can encourage emission abatement, while Yang and Chen (2018) evaluated cost-sharing and revenue-sharing mechanisms to stimulate retailer-driven carbon reduction, revealing conditions under which cooperative schemes outperform unilateral efforts. He and Deng (2020) incorporated CEA into competitive pricing models, concluding that heightened environmental awareness intensifies price competition but can also enhance market share for greener products. Heydari et al. (2020) compared pricing of green products based on their environmental quality attributes, highlighting that premium pricing is more sustainable when product greenness meets or exceeds consumer expectations.

More recent studies have expanded this integration of sustainability into supply chain strategies. SAIDI et al. (2024) modelled the combined effects of sustainability and resilience on supply chain pricing strategies, showing how investment efficiency and policy interventions shape profitability. Hamdi (2024) reviewed sustainable packaging trends in the consumer-packaged goods sector, noting that innovations such as RFID, AI, and biodegradable materials can reduce environmental impact while enhancing brand value. Li and Xiong (2025) integrated CEA and fairness concerns into green supply chain decision-making, demonstrating how consumer environmental mindset and manufacturer fairness attitudes jointly affect greenness, pricing, and advertising strategies. Krishnan et al. (2024) linked green marketing strategies to consumer loyalty through the mediating role of perceived value, offering empirical evidence from the Malaysian retail sector. Kadam (2024) compared green marketing approaches in developed and developing markets, identifying contextual factors that influence effectiveness. Phonthanukitithaworn et al. (2024) empirically tested the relationship between green supplier cooperation and waste management outcomes in emerging markets, finding that green distribution practices significantly improve customer engagement in sustainable behaviors. Hayyat (2024) discussed the integration of digital technologies such as IoT and blockchain into green operations, showing how digitalization enhances environmental performance and operational efficiency. P23) further analyzed the integration of corporate social responsibility (CSR) investments into dual-channel closed-loop supply chains, revealing how channel structure and consumer sensitivity to CSR influence optimal pricing, recycling rates, and profitability.

Although these studies collectively deepen our understanding of how CEA and sustainability factors shape supply chain strategies, few explicitly connect CEA-driven environmental investment to SB-NB competitive pricing models, particularly in scenarios involving varying channel leadership structures and different levels of product substitutability. This gap limits the applicability of existing findings to competitive retail environments where sustainability is a key differentiator. To address this gap, this paper investigates three research questions:

RQ 1. How does CEA influence the retail prices of SB and/or NB products?

RQ 2. How does CEA impact the wholesale price of NB products?

RQ 3. What is the optimal level of environmental investment in SB and/or NB products?

Our approach develops a mathematical model for a two-stage supply chain comprising one NB manufacturer and one retailer selling both SB and NB products. We analyze three channel power structures: Manufacturer-Stackelberg (MS), Retailer-Stackelberg (RS), and Vertical Nash (VN), under two environmental investment scenarios: NB-only investment and investment in both SB and NB products. Game-theoretic methods yield equilibrium retail prices, wholesale prices, environmental investment levels, and profits. Numerical simulations illustrate the effects of CEA and product substitutability on these outcomes, identifying the conditions under which each power structure is optimal.

The main findings are: when only NB products are environmentally invested in, CEA positively affects both manufacturer and retailer profits by increasing NB demand and allowing upward price adjustments for both brands; CEA and product substitutability jointly determine the optimal channel power structure, with high CEA/low substitutability favoring manufacturer-led structures and high substitutability favoring retailer-led structures; high substitutability leads retailers to set higher retail prices for both SB and NB due to stronger cross-price effects; and RS structures ensure retailer profitability across a wide range of CEA and substitutability levels due to control over both SB and NB pricing.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents the model structure, variables, and assumptions.

Section 3 analyses equilibrium outcomes under different power structures and investment scenarios.

Section 4 discusses managerial implications.

Section 5 concludes with key insights and suggestions for future research.

2. Model Description

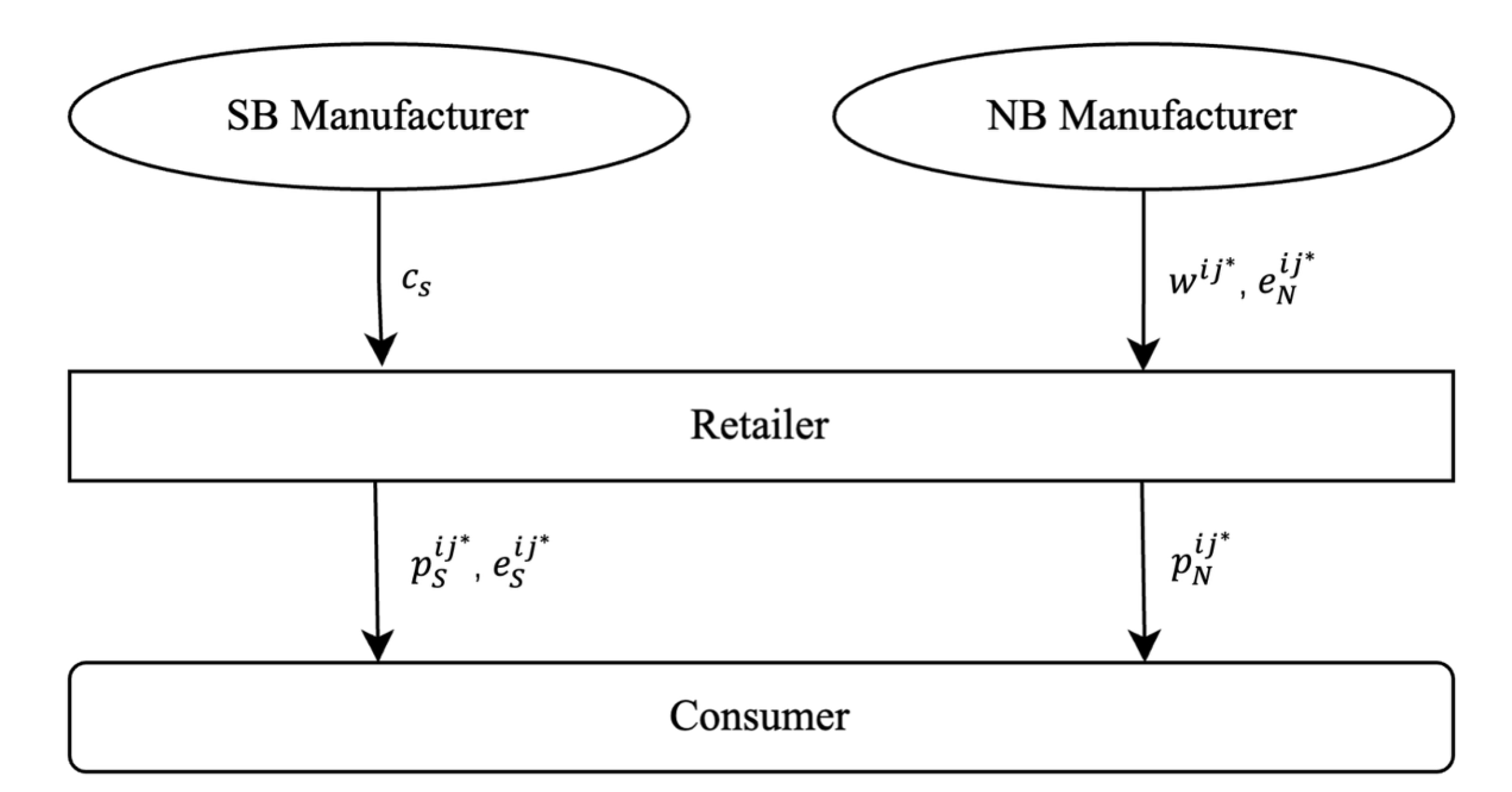

This study examines the impact of consumer environmental awareness on the decision-making processes of supply chain participants engaged in the provision of SB and NB products. The analysis focuses on two distinct scenarios: the CO scenario, in which environmental efforts are implemented exclusively for NB products, and the CC scenario, where such efforts are extended to both NB and SB products. To evaluate the channel power structure, we employ the framework established by Choi (1996) and consider three game models: the Manufacturer-Stackelberg (MS) model, where the manufacturer assumes a leadership role; the Retailer-Stackelberg (RS) model, where the retailer takes the lead; and the Vertical Nash (VN) model, characterized by simultaneous decision-making by both parties. As

Figure 1 illustrated, the manufacturer determines the unit wholesale price and the total environmental level for the NB products. In addition, the retailer determines the unit retail prices for NB and SB products, as well as the total environmental level for SB products. In particular, the SB products are produced by the retailer’s contracted manufacturer in a unit fixed cost, represented by

.

Table 1.

Decision Variables

Table 1.

Decision Variables

| Variable |

Description |

|

The total environmental level for SB and NB products, . |

|

The retail price for SB and NB products, . |

|

The unit wholesale price for NB products, . |

Table 2.

Model Parameters

Table 2.

Model Parameters

| Parameter |

Description |

|

The unit fixed production cost for NB and SB products. |

|

The coefficient of consumer environmental sensitivity. |

|

The intensity of channel competition between two brands’ products. |

|

The profit function of NB manufacturer, . |

|

The profit function of the retailer, . |

|

The demand function of SB and NB products, . |

|

The coefficient of environmental investment cost of SB and NB products. |

| * |

The superscript that represents the optimal solution. |

In our model, we firstly study the impact of CEA on the decision-making of supply chain players and the profit of the players. We assume that the retailer is mighty, and there is no quality diversity between two brands products. In this paper, we develop three game patterns to deliberate various channel-leadership structures:

Manufacturer-Stackelberg (MS): the NB manufacturer determines the wholesale price and the environmental level for NB products utilizing the response function from the retailer. Then, the retailer determines the retail price of the SB and NB products, and the environmental level of SB products to maximize its profit.

Retailer-Stackelberg (RS): the NB manufacturer determines the wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products conditional on the margin of themselves. The retailer sets up the margin of the NB products utilizing the reaction functions of the NB manufacturer on the basic of the respective wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products.

Vertical Nash (VN): the NB manufacturer determines the wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products, the retailer determines the margin of NB products conditional on the respective wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products, simultaneously.

Then, we define the environmental investment function of brand

l as follow (Liu et al. 2012):

is the environmental investment cost for two brand products,

.

is one coefficient that represents the environmental investment cost of products. The higher

, the lower the efficiency of environmental production. That is to say, the environmental investment is a concave function of the environmental level of products,

increases as the environmental level increases. However, the coefficient of environmental investment cost between two brands is different. Without loss of generality, we suppose that

because it is a fact that the efficiency of NB production was higher than that of SB production in real business. For instance, NB manufacturer normally has the better production technology and equipment.

Next, We define the demand function of brand i rewritten by Choi (1996) from two cases: The first case contains an environmental NB () and a traditional SB (), which denoted by (C, O). The second case contains an environmental SB () and an environmental NB (), which denoted by (C, C). The demand function is influenced by retail price and environmental investment.

In this setting, is the coefficient of customer environmental sensitivity, which represents the preference of customers regarding environment-friendly products. The higher , the more sensitive consumers are to the environmental level of products. In the other words, the higher CEA, the more the consumers willingly pay higher prices for the products which has the high environmental quality (Chitra, 2007). is intensity of competition between two brands. The higher , the higher substitutability between two brand products, where .

To simplify the model analysis, we suppose that the fixed cost (no environmental investment) of two brands products is equal, where . Besides, both the NB manufacturer and the retailer are risk neutral. The decision function is the expected profit maximization.

3. Model Analysis

We discuss the competition between SB and NB by comparing six scenarios under different channel leadership structures and production decisions (environmental investment or not), which denoted by COMS, CORS, COVN, CCMS, CCRS, CCVN.

3.1. One Traditional SB and One Environmental NB (C, O)

In (C, O), we evaluate performance of supply chain that there are two types of products, which includes a traditional SB and an environmental NB. The profit maximization for the retailer and the manufacturers are:

3.1.1. Manufacturer-Stackelberg (COMS)

In the scenario of COMS, the decision process follows:

Step 1: NB manufacturer decides the wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products.

Step 2: The Retailer decides the retail price for SB and NB products.

Based on backward induction, we obtain the first order condition with respect to

and

:

The Hessian matrix of Equation (

7) satisfies that

. Hence, we obtained the optimal solutions for

and

by solving the equations (8) and (9):

Then, we substituted the equations (10) and (11) to Equation (

6), and solved the optimization problem for Equation (

6) with respect to

and

(

of Equation (

6) was also greater than 0):

Next, substitute the equations (12) and (13) to the equations (10) and (11), we get the optimal solutions of retail price for SB and NB.

Finally, the profit for NB manufacturer and retailer are:

Theorem 1.

There exists one unique solution in COMS for the retail price of SB and NB products, the environmental level and the wholesale price of NB products.

In COMS, we can know that the optimal profit of the NB manufacturer,

, is not related to the intensity of competition between SB and NB,

, see the Equation (

16). It is also obvious that

,

, and

.

Corollary 1.

Under COMS, when the intensity of competition between SB and NB, β, increase, the optimal prices of NB and SB, , , increases, the optimal profit of the NB manufacturer, , remain unchanged, while the optimal profit of the retailer, , increases.

Corollary 1 shows that it’s more profitable for the retailer in the case of COMS, while there is no effect on the profit of the NB manufacturer. When the intention of competition between two brands, or the substitutability of two brands’ products, increases, the retail prices of both brands’ products also increase. Moreover, the wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products are not influenced by the competition intention.

From the equations (10) and (11), we can get , . Hence, Corollary 2 can be acquired.

Corollary 2.

Under COMS, when the environmental level of NB products, , increases, the optimal prices of NB and SB, , , will increase.

Corollary 2 shows that when the NB manufacturer enhances the environmental investment of NB products, the retail price of NB products will also increase. In such situation, the price pressure from NB products for SB products goes down. The retailer will also increase the retail price for SB products to maximize its profit.

Similarly, from the equations (12)-(17), we can get the results as follow: , and .

Corollary 3.

Under COMS, with the coefficient of customer environmental sensitivity, τ, increases, the optimal prices of NB and SB, , , the optimal wholesale price of NB products, , the optimal environmental level of NB products, , and the optimal profit of the NB manufacturer and the retailer, , , increase.

Corollary 3 shows that if the environmental investment of NB products has a more significant impact on the demand of NB products under COMS, the retail price of two brands products, the wholesale price of NB products, and the environmental level of NB products will increase. In this situation, the impact of environmental protection investment on the demand increases, improving the brand awareness of NB products and increasing the demand of NB products. Meanwhile, the retailer will also increase the retail price of SB products because of the retail price increasing of NB products. As a result, both the profit of the NB manufacturer and the retailer increase.

3.1.2. Retailer-Stackelberg (CORS)

Under the scenarios of CORS, the retailer has stronger market control than the NB manufacturer, and more bargaining power in the channel of supply chain. In this situation, the wholesale price of NB manufacturer depends on the retail price set by the retailer, and the retailer determines the corresponding retail prices for products by the response function of NB manufacturer. Therefore, the decision process in CORS follows:

Step 1: the retailer first decides the optimal retail prices for SB and NB products.

Step 2: NB manufacturer decides the optimal wholesale price and environmental level for NB products.

In this circumstance, we set the retail price of NB products as follows (

is the margin of SB products for the retailer):

Then, we substitute Equation (

18) into Equation (

6). The first order function of the wholesale price and the environmental level for NB products can be obtained:

Solve the optimization problem for the equations of (20) and (21), the optimal wholesale price and environmental level for NB products are:

Substitute the equations (22) and (23) to the Equation (

7), we acquired the optimal retail prices for SB and NB products by solving the first order functions of

and

.

From the Equation (

22) and (23),

, and the limiration of

is equal to

. As a result,

. Substitute the Equation (

24) and (25) to the Equation (

22) and (23),

and

can be obtained.

Finally, the optimal profit for NB manufacturer and the retailer are (

):

Theorem 2.

There exists one unique solution in CORS for the retail price of SB and NB products, the environmental level and the wholesale price of NB products.

Corollary 4.

Under CORS, when the intensity of competition between SB and NB increases, β, the profit of the NB manufacturer decreases.

In the scenario of CORS, except for the profit of the NB manufacturer, the impact of the coefficient of customer environmental sensitivity and the intensity of competition between SB and NB on the retail price of NB and SB products, the environmental level of NB products, and the profit of the retailer are similar with the scenario of COMS, we will discuss in section 4 by numerical examples.

3.1.3. Vertical Nash (COVN)

In the COVN scenario, there is no leader in the supply chain. The decision process is as follows: the NB manufacturer decides the wholesale price and the environmental level for NB products, and the retailer decides the retail prices for both SB and NB products.

For the optimization problem, the NB manufacturer and the retailer make their decision-making by themselves, which maximizes their profit. In COVN, we obtained the optimal wholesale price and the environmental level for NB products by solving equations (8), (9), (20), and (21).

Likewise, the optimal retail price of SB and NB products, and the optimal environmental level of SB products can be also acquired.

Finally, the optimal profit for NB manufacturer and the retailer are:

Theorem 3.

There exists one unique solution in COVN for the retail price of SB and NB products, the environmental level and the wholesale price of NB products.

3.2. One Environmental SB and One Environmental NB (C, C)

In (C, C), we evaluate the competition between SB and NB that both two brand introduced environmental investment to acquire more market share and then increase their own profit. There are two differences between two brands’ products: retail price and environmental level. The profit maximization for the retailer and the manufacturers is:

3.2.1. Manufacturer-Stackelberg (CCMS)

In the scenario of CCMS, the decision process follows:

Step 1: The NB manufacturer decides the wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products.

Step 2: The Retailer decides the retail price of SB and NB products, and the environmental level of SB products.

The same as the scenario COMS, we obtained the first-order condition with respect to

, and

based on backward induction:

Solve the equations (38), (39), and (40),

and

are:

Substitute the equations (40), (41), and (42) to the Equation (

36). Then, we obtained the optimal solutions for

and

.

Finally, we acquired the optimal solutions for

, and

.

Theorem 4.

There exists one unique solution in CCMS for the retail price of SB and NB products, the environmental level of SB products, the environmental level and the wholesale price of NB products.

3.2.2. Retailer-Stackelberg (CCRS)

Under the scenario of CCRS, the retailer holds stronger market control than the NB manufacturer, thereby possessing greater bargaining power within the supply chain channel. In this setting, the wholesale price determined by the NB manufacturer depends on the retail price set by the retailer, while the retailer, in turn, sets the corresponding retail prices for products based on the NB manufacturer’s response function. Accordingly, the decision process in the scenario CCRS unfolds as follows:

Step 1: The retailer first decides the optimal retail prices for SB and NB products, and the environmental level of SB products.

Step 2: The NB manufacturer decides the optimal wholesale price and environmental level for NB products.

For the optimization problem, the same to CORS, we also set

. Then, we obtained the first-order condition of the wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products.

Then, solve the equations (49) and (50).

Next, we substituted (49) and (50) to the equations (36) and (37). Solve the first order condition of

, and

. Finally, the optimal

, and

can be also obtained (

).

Theorem 5.

There exists one unique solution in CCRS for the retail price of SB and NB products, the environmental level of SB products, the environmental level and the wholesale price of NB products.

3.2.3. Vertical Nash (CCVN)

In the CCVN scenario, there is no leader in the supply chain. The decision process is as follows: the NB manufacturer decides the wholesale price and the environmental level for NB products, while the retailer decides the retail prices for SB and NB products, as well as the environmental level for SB products. For the optimization problem, the NB manufacturer and the retailer independently make decisions to maximize their profits. In the CCVN case, the optimal wholesale price and the environmental level for NB products are obtained by solving equations (38), (39), (49), and (50).

Theorem 6.

There exists one unique solution in CCVN for the retail price of SB and NB products, the environmental level of SB products, the environmental level, and the wholesale price of NB products.

Corollary 5.

Under CCVN, with the consumer environmental sensitivity increases, the environmental level and the wholesale price of NB products, , increases. Besides, is not related to the intensity of competition between SB and NB. See equations (58) and (59).

4. Numerical Analysis

To verify the correctness of the results in section 3, we assume that , and changes in the interval of . Then, we compared the optimal profit of the NB manufacturer and the retailer, and the optimal retail price of SB and NB products under different scenarios.

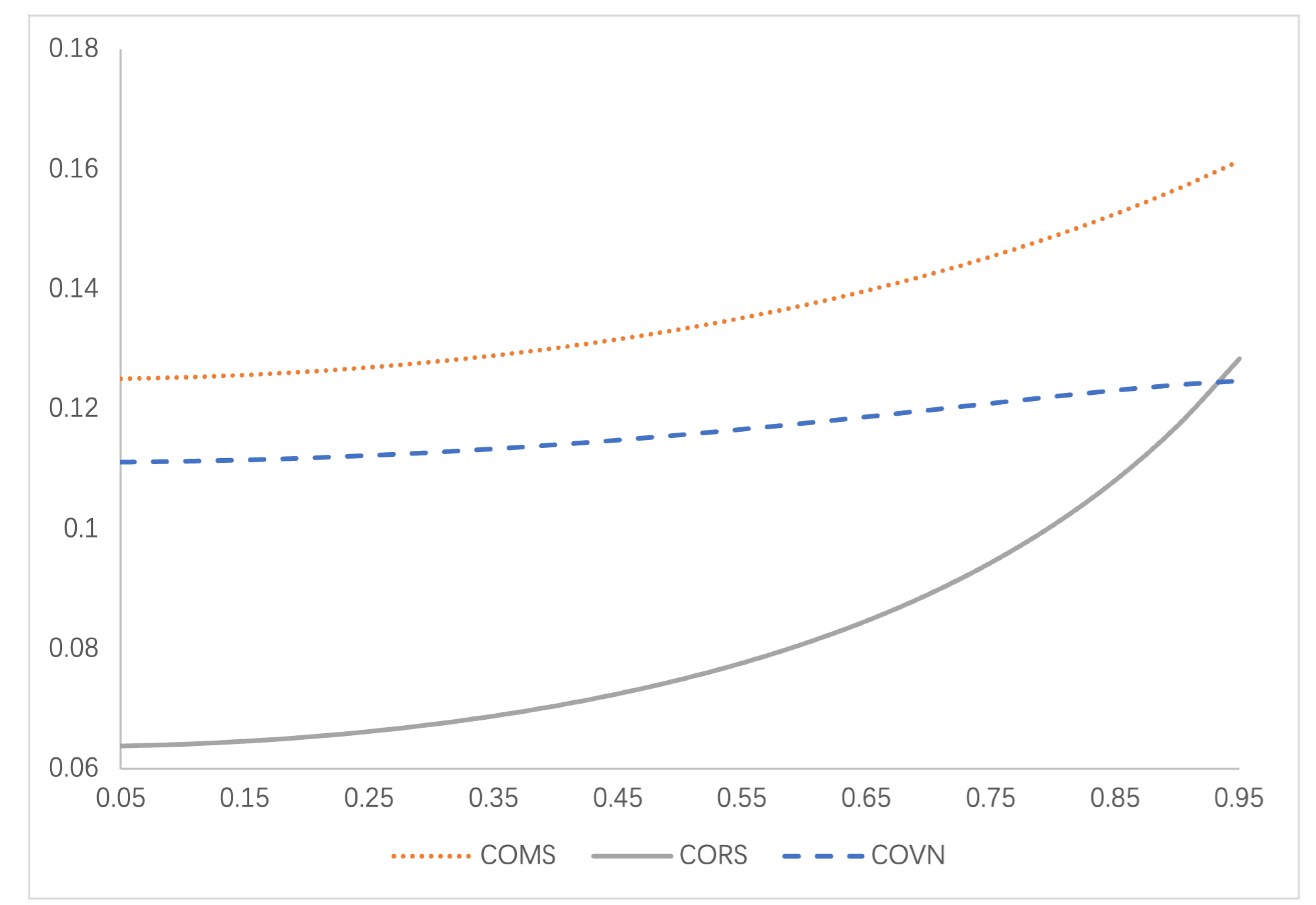

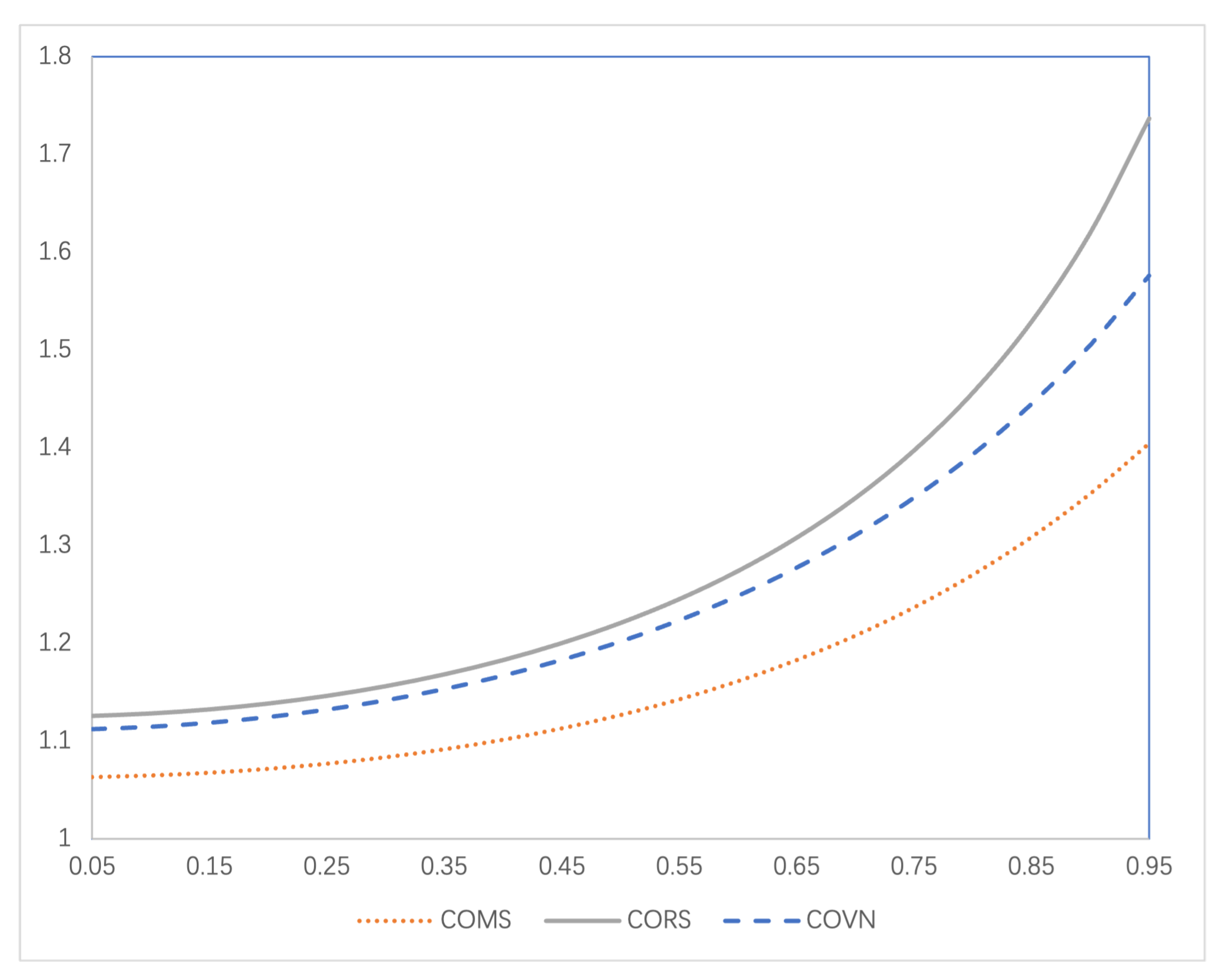

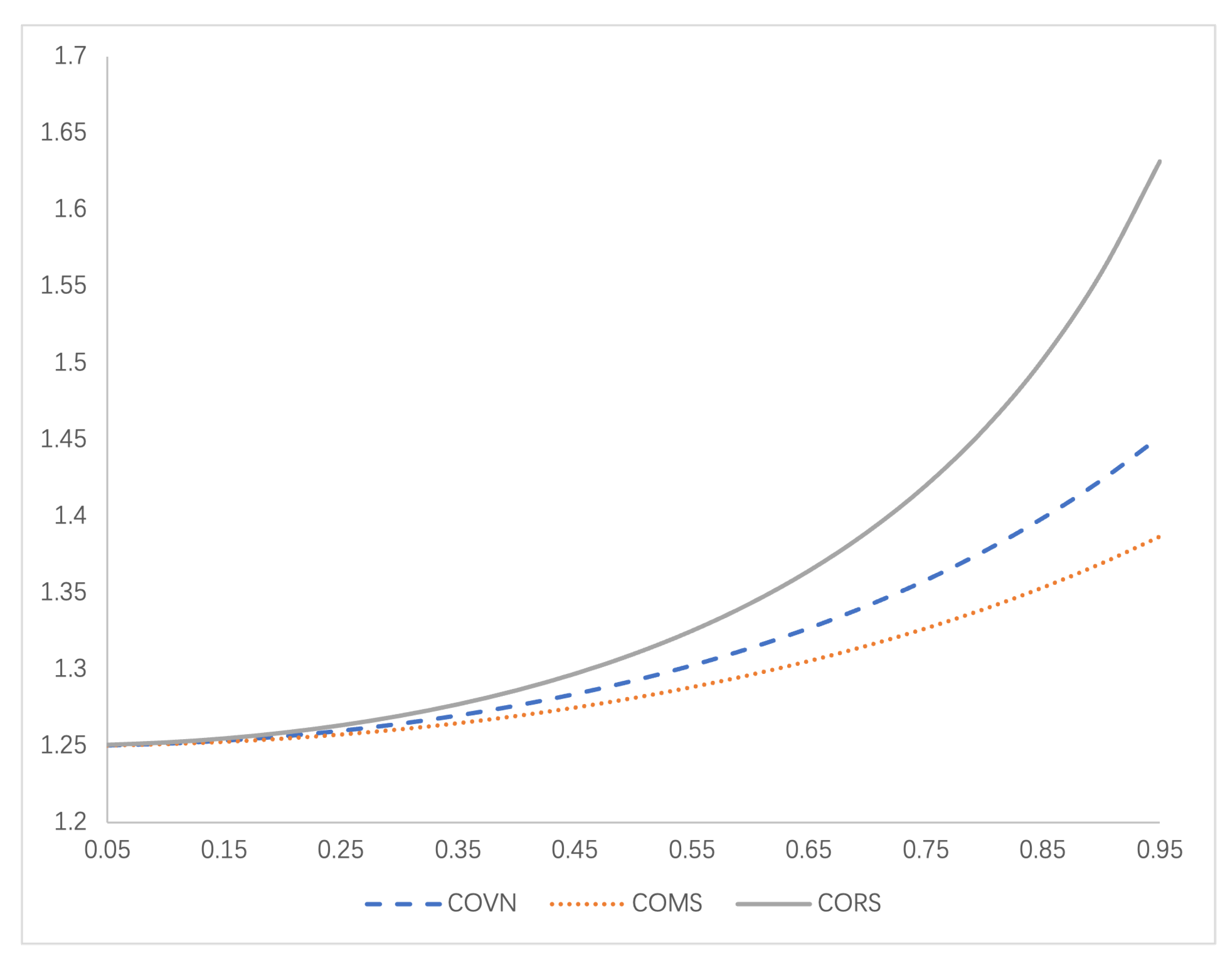

4.1. The Numerical Analysis of COMS, CORS, and COVN

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the variations and comparisons of the NB manufacturer’s optimal profit.

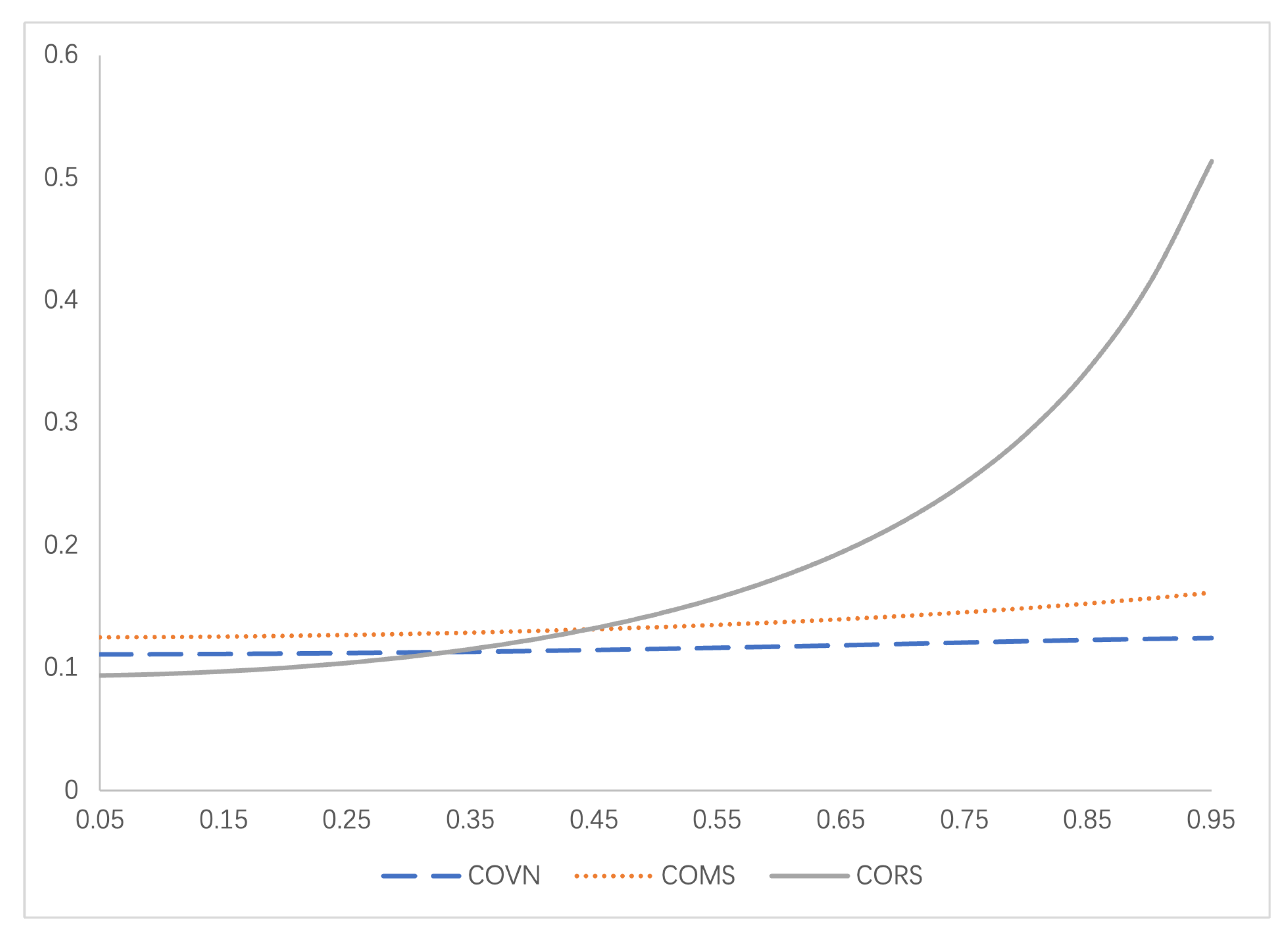

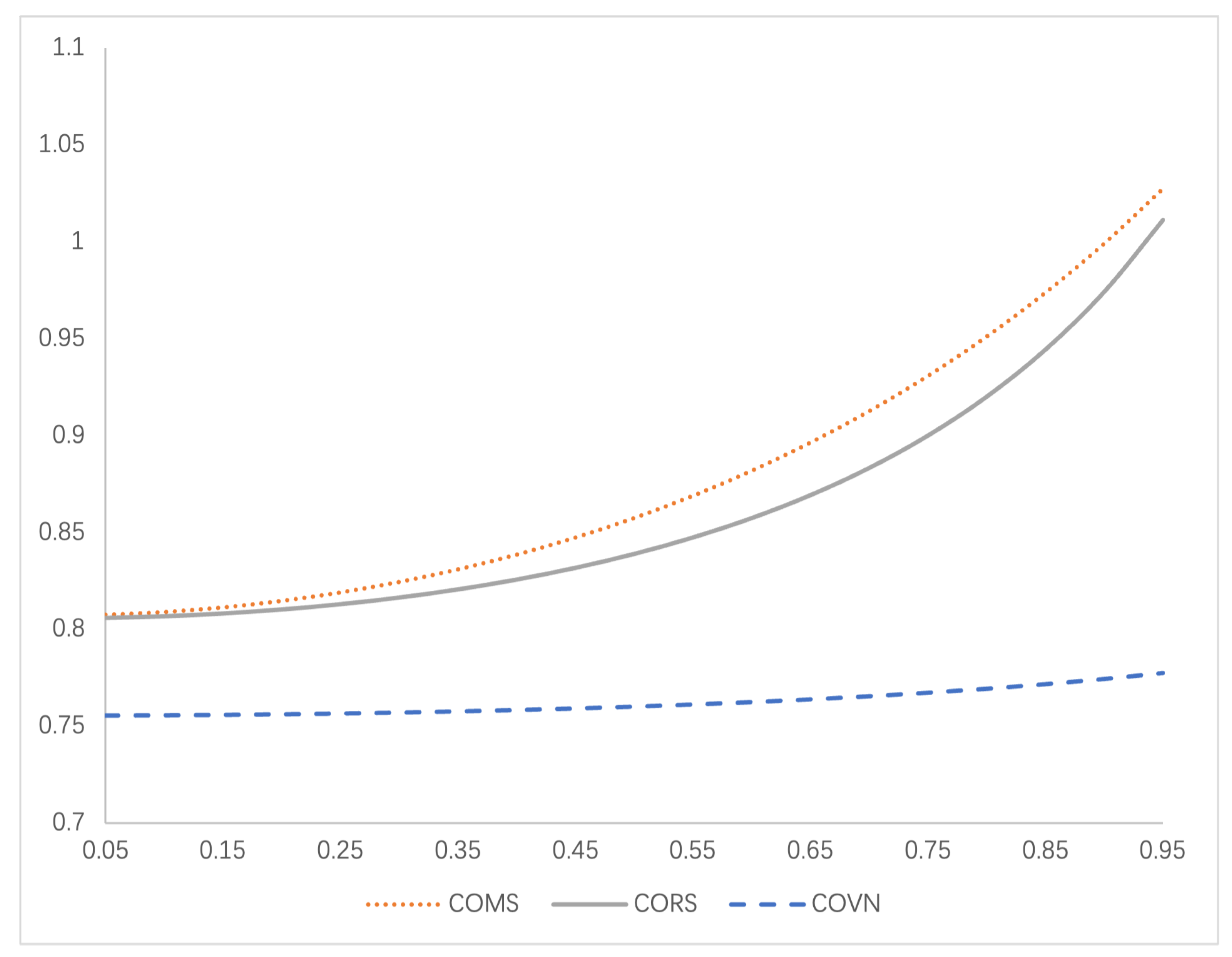

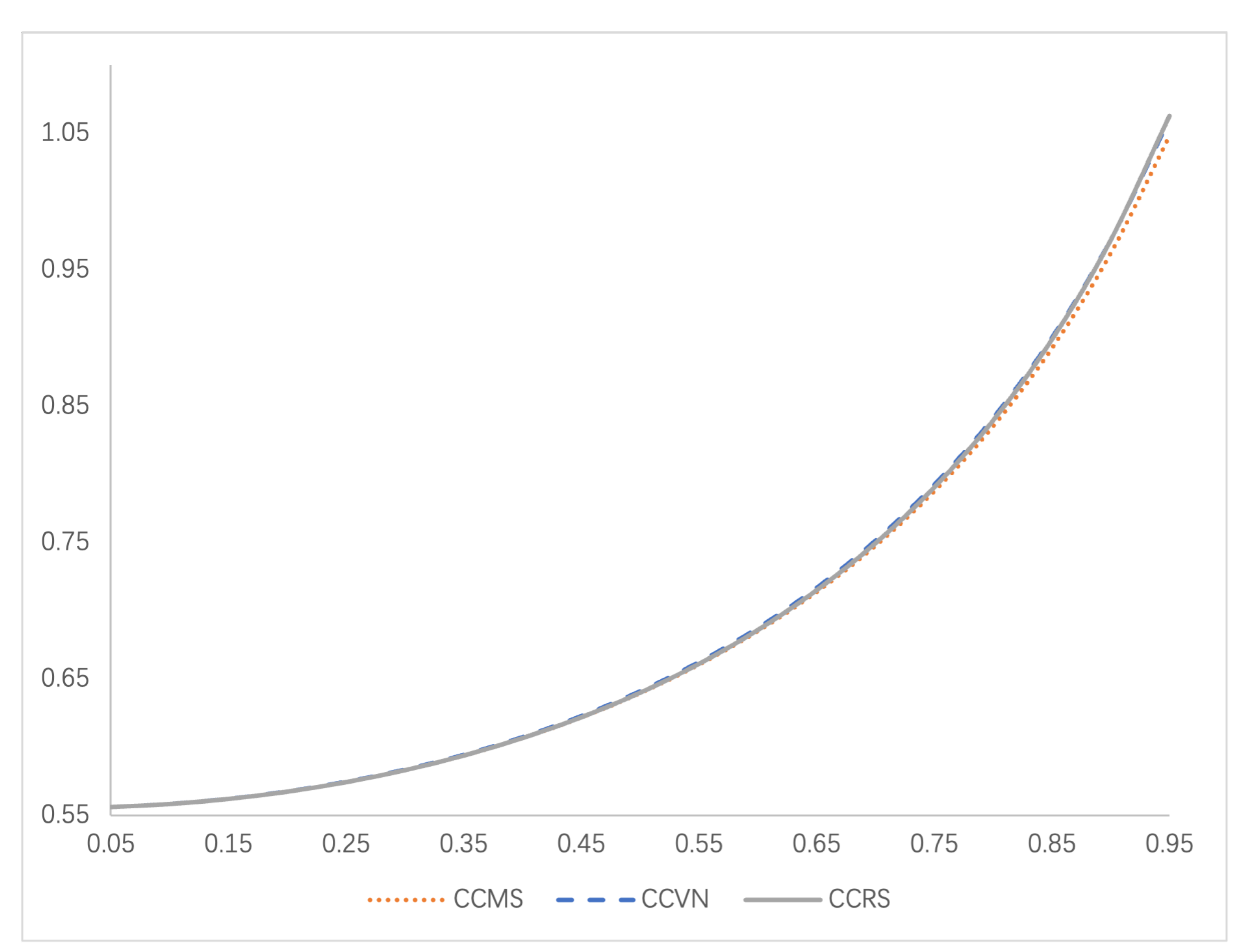

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 depict the trends and comparisons of the retailer’s optimal profit.

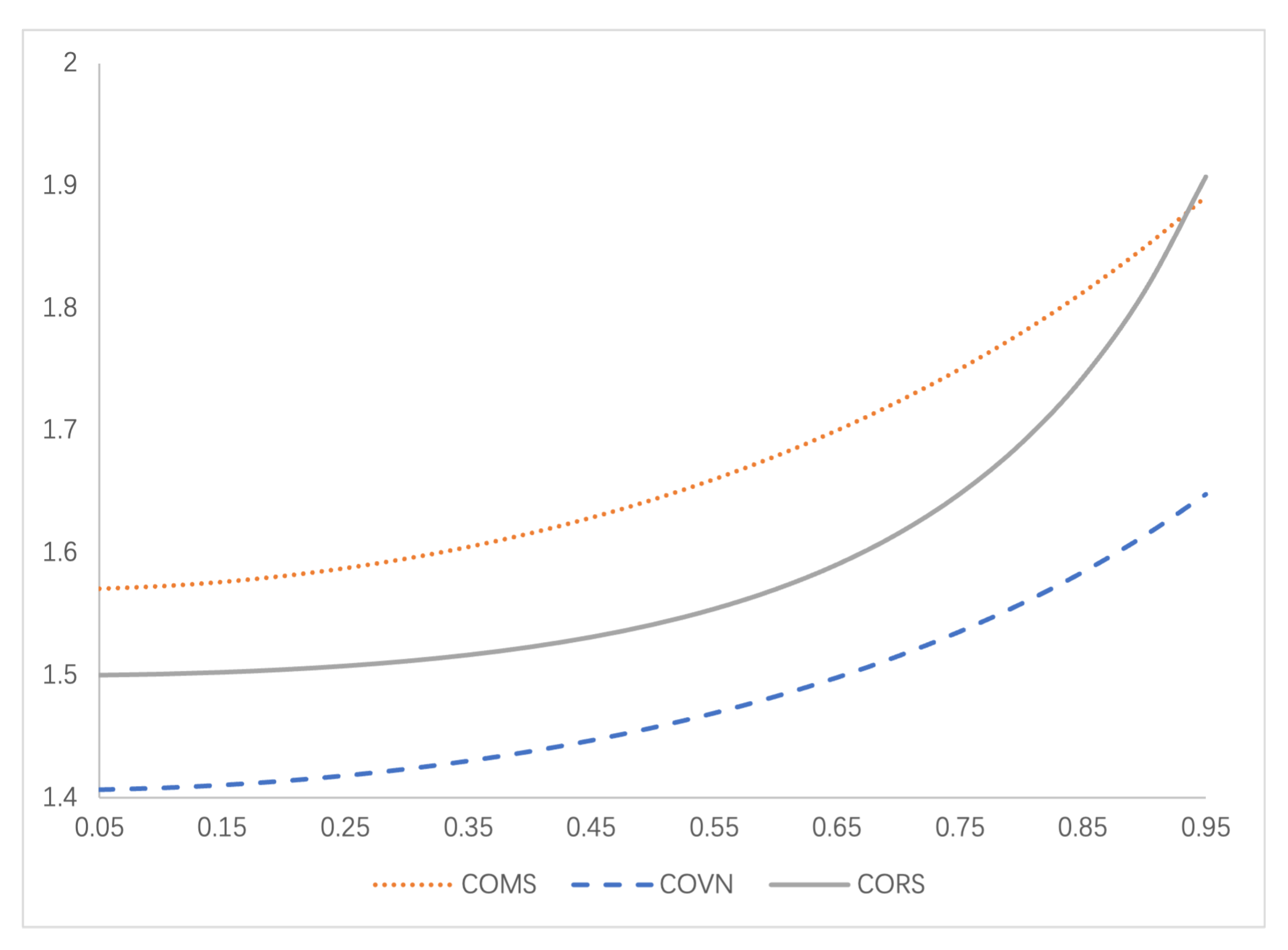

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 present the changes and comparisons in the optimal retail price of the NB product.

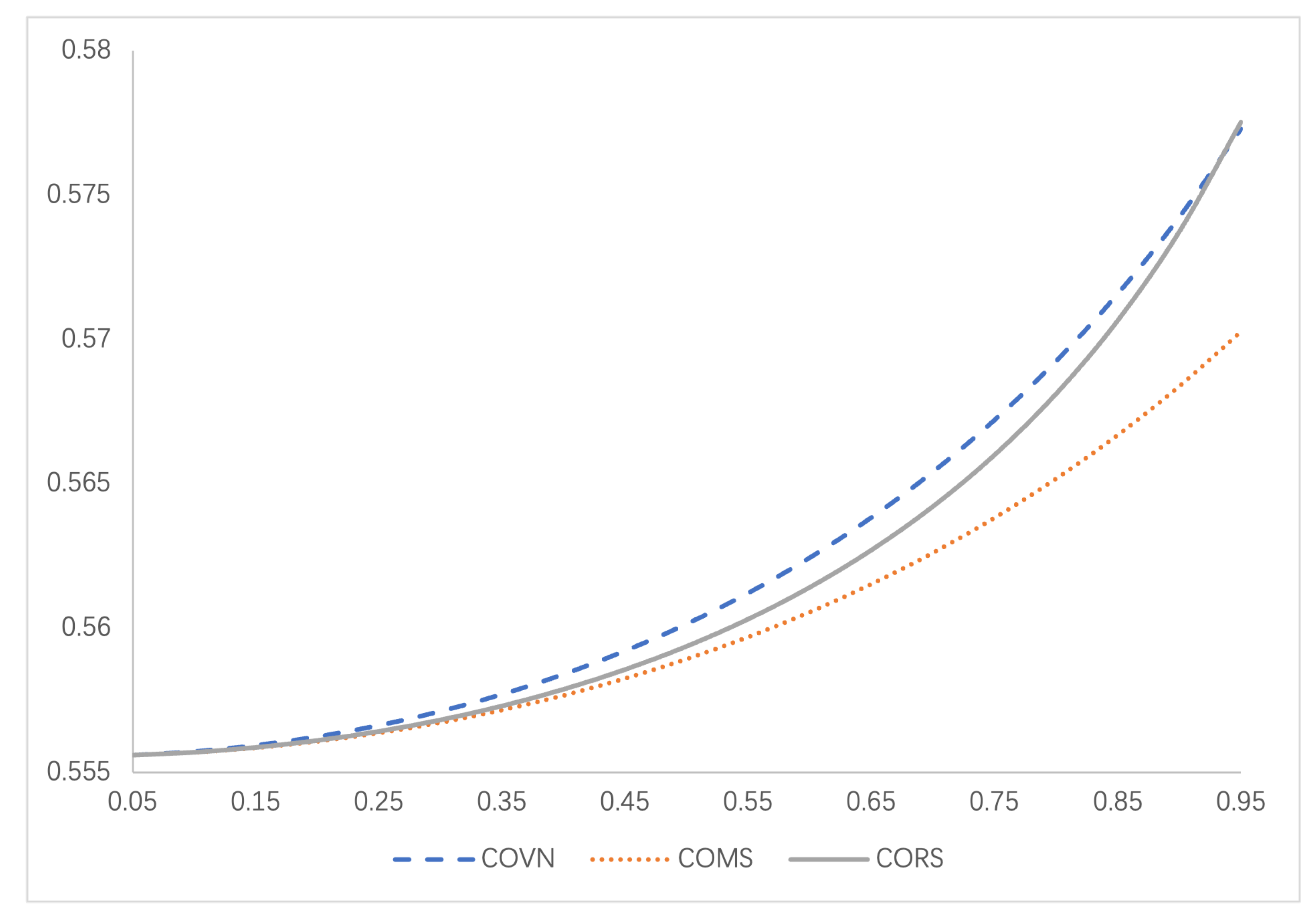

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show the differences and comparisons in the retail price of the SB product.

Specifically,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 show that the optimal profits of NB manufacturer in COMS, CORS, and COVN in the case

are greater than the case

. When the intensity of competition between SB and NB products is high, the NB manufacturer is more profitable. From the viewpoint of channel leadership, when the intensity of competition between two brands is low, the NB manufacturer is more profitable under COMS, while the NB manufacturer is more profitable under CORS when the intensity of competition between two brands. In addition,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show that it is more beneficial for the retailer in COMS, CORS, and COVN under the condition

than that of

. The retailer can obtain more profit in the channel-leadership of CORS regardless of the intensity of competition between SB and NB when the NB manufacturer introduces environmental production for NB products.

Observation 1. Under the situation that there are one traditional SB and one environmental NB, it is favorable for the NB manufacturer to choose the channel-leadership of Manufacturer-Stackelberg if the intensity of competition between SB and NB is not high. Otherwise, it is better to choose the channel-leadership of Retailer-Stackelberg.

Observation 2. Under the situation that there are one traditional SB and one environmental NB, the retailer always can achieve profit maximization under the channel-leadership of Retailer-Stackelberg.

Observation 1 shows the optimal decision-making in the channel-leadership for the NB manufacturer who introduced the environmental production under the situation that there is a traditional SB that competing with its products in supply chain. Observation 2 shows the best channel-leadership strategy for the retailer who faces the competition between a traditional SB and an environmental NB. In other words, the retailer who has the strong barging ability in supply chain can optimize their operational management from the perspective of the channel-leadership.

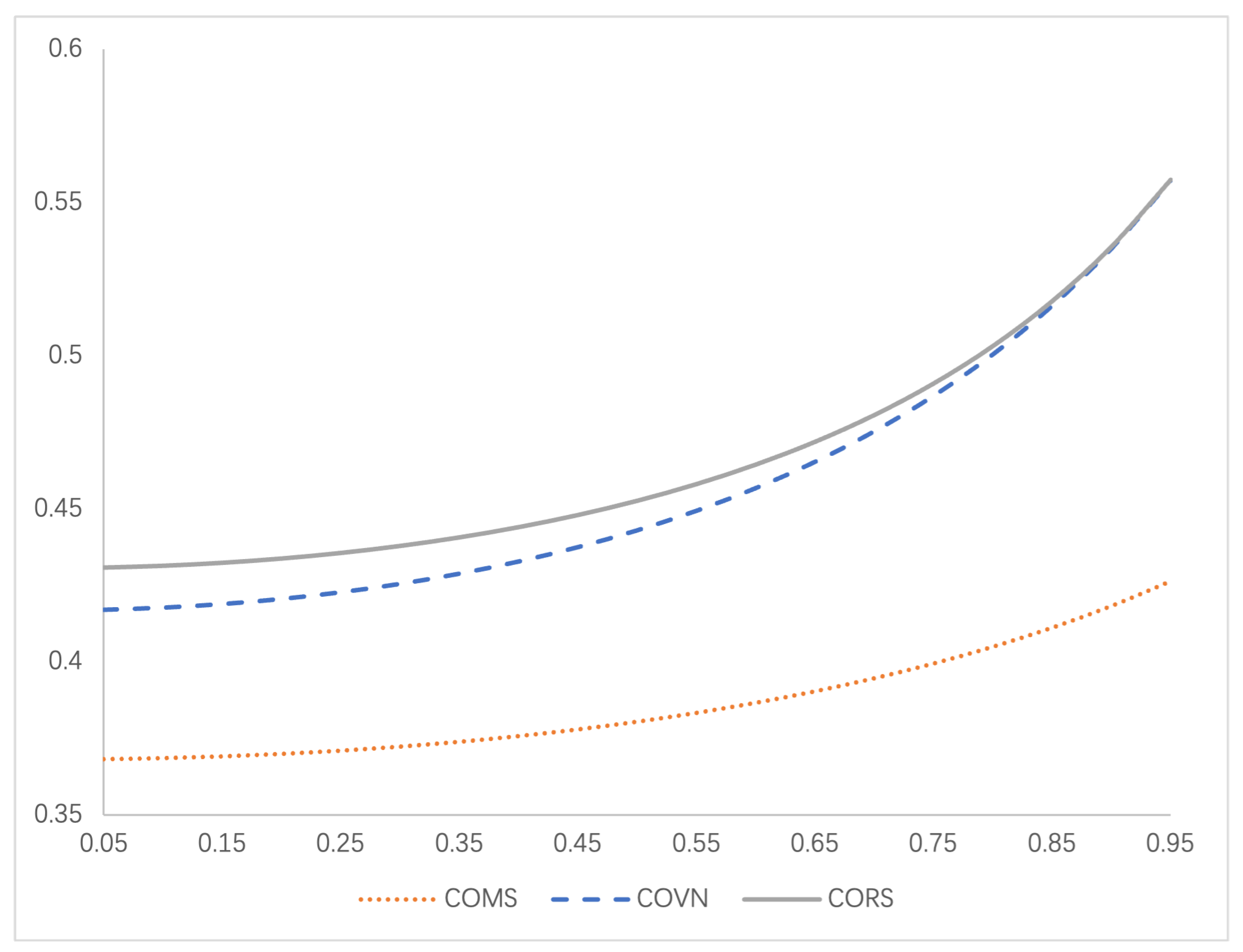

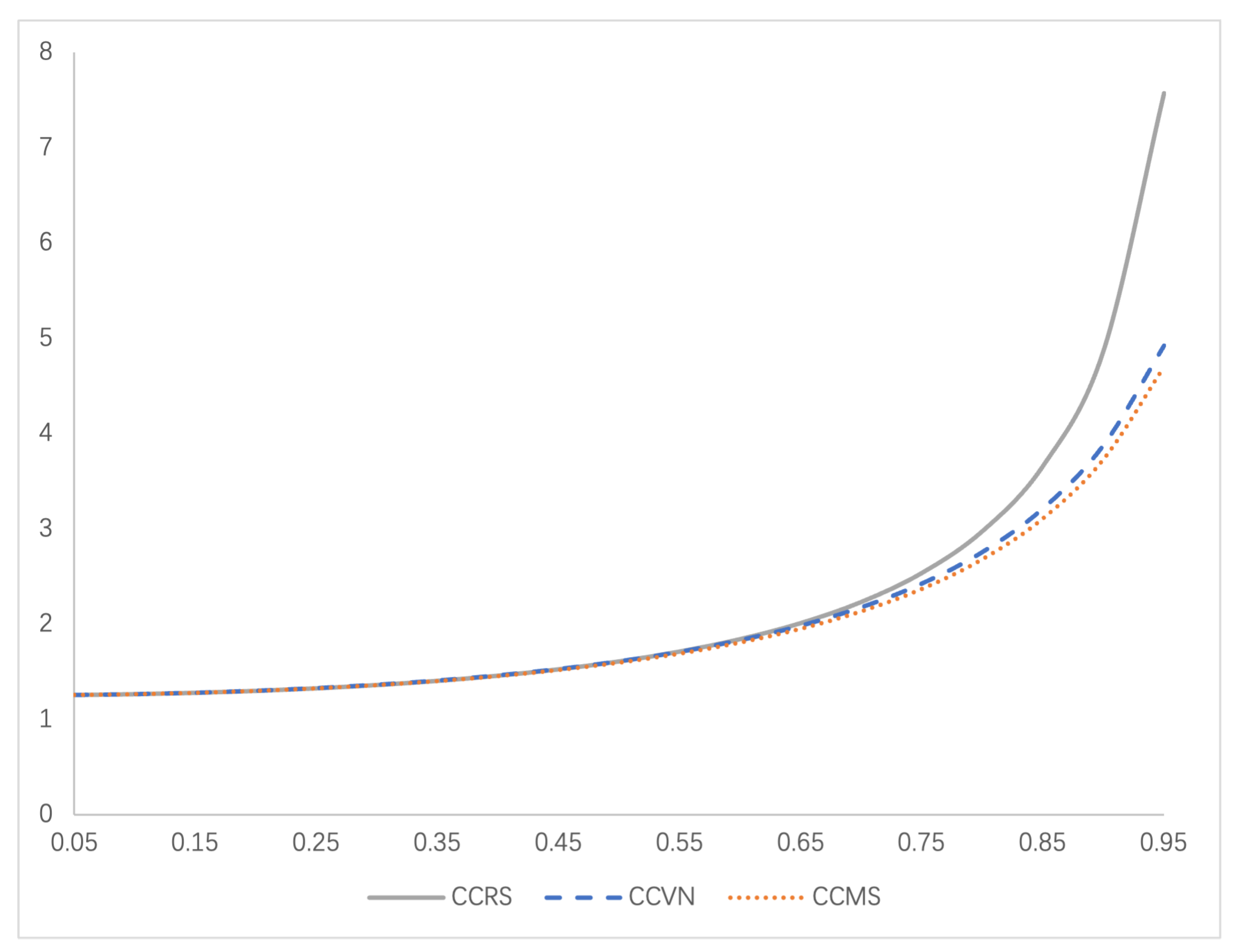

Moreover,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 show how consumer environmental sensitivity influences the retail prices of NB and SB products under varying intensities of competition between the two brands. Several implications for practical pricing strategies can be drawn from these results.

Observation 3. Under the situation that there are one traditional SB and one environmental NB, the optimal retail price of NB products always satisfies that , whether the intensity of competition between SB and NB is high or low.

Observation 4. Under the situation that there are one traditional SB and one environmental NB, the optimal retail price of SB products in the channel-leadership of Manufacturer-Stackelberg is lowest, and satisfies that when the intensity of competition between SB and NB is high, otherwise.

Observation 3 indicates that the retailer is likely to set a high retail price for NB products when acting as the follower in the supply chain, because the retailer does not have information about the wholesale price and the environmental level of NB products. Under such circumstances, to achieve profit maximization, it is safer for the retailer to set a high retail price for NB products (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Observation 4 shows that the optimal retail price of SB products is the lowest under the Manufacturer-Stackelberg channel leadership. The reason is that the retailer lacks effective information about NB products and thus tends to set a low retail price for SB products to capture more market share. Furthermore, the optimal retail price of SB products in the CORS scenario is higher than that in the COVN scenario when competition between SB and NB products is fierce. In other words, the higher the intensity of competition between the two brands, the higher the retail price of SB products.

Observation 5. Under the situation that there is one traditional SB and one environmental NB, the retail price of NB products is always higher than the retail price of SB products when the intensity of competition between SB and NB is low. See

Figure 6 and

Figure 8.

Observation 6. Under the situation that there is one traditional SB and one environmental NB, if both the intensity of competition between SB and NB and the consumer environmental sensitivity are high, it is beneficial for both the NB manufacturer and the retailer to choose the channel-leadership of Retailer-Stackelberg.

Observation 7. Under the situation that there are one traditional SB and one environmental NB, if both the intensity of competition between SB and NB and the consumer environmental sensitivity are low, it is beneficial for the NB manufacturer to choose the channel-leadership of Manufacturer-Stackelberg. (See

Figure 4 and

Figure 5).

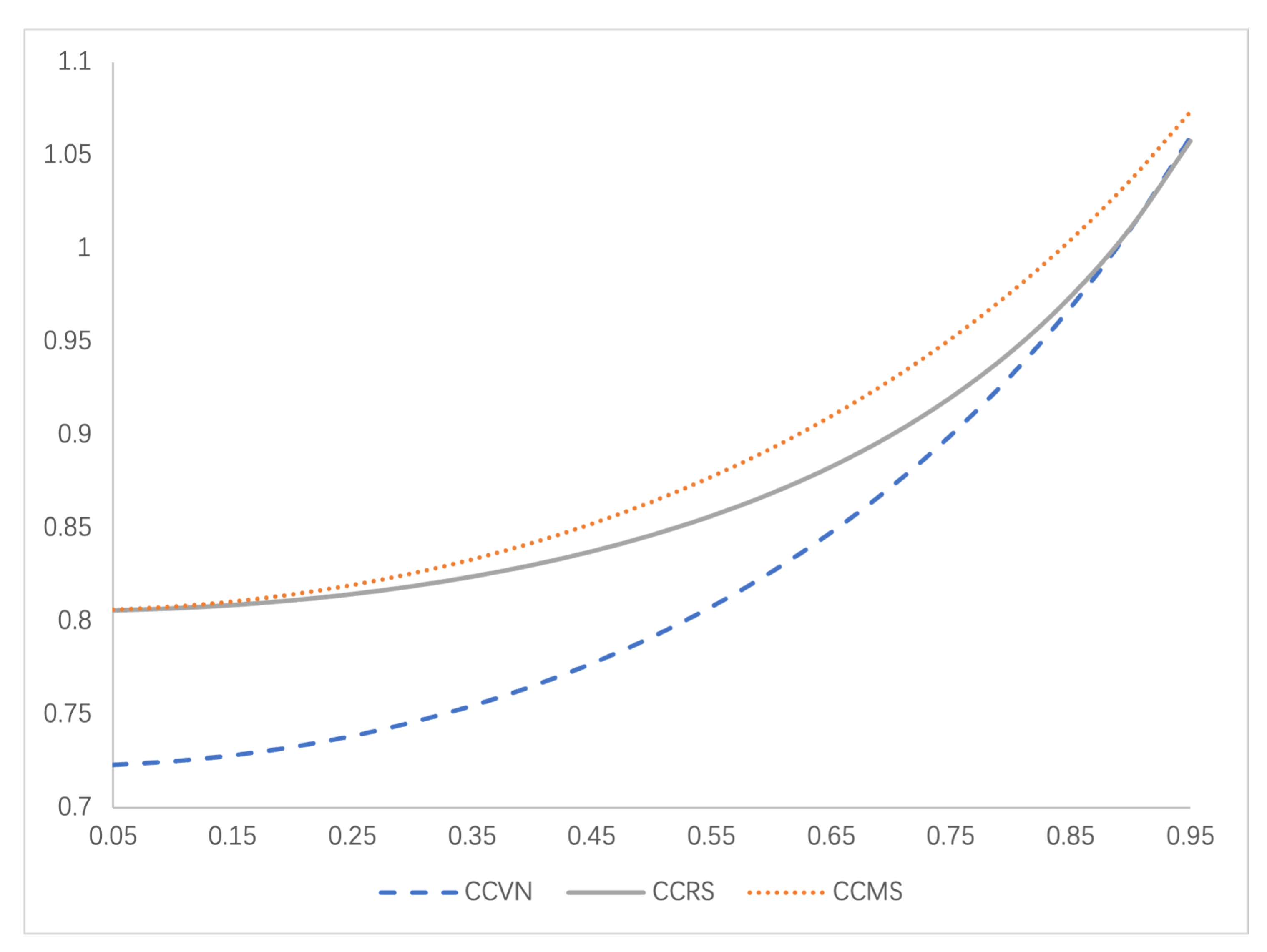

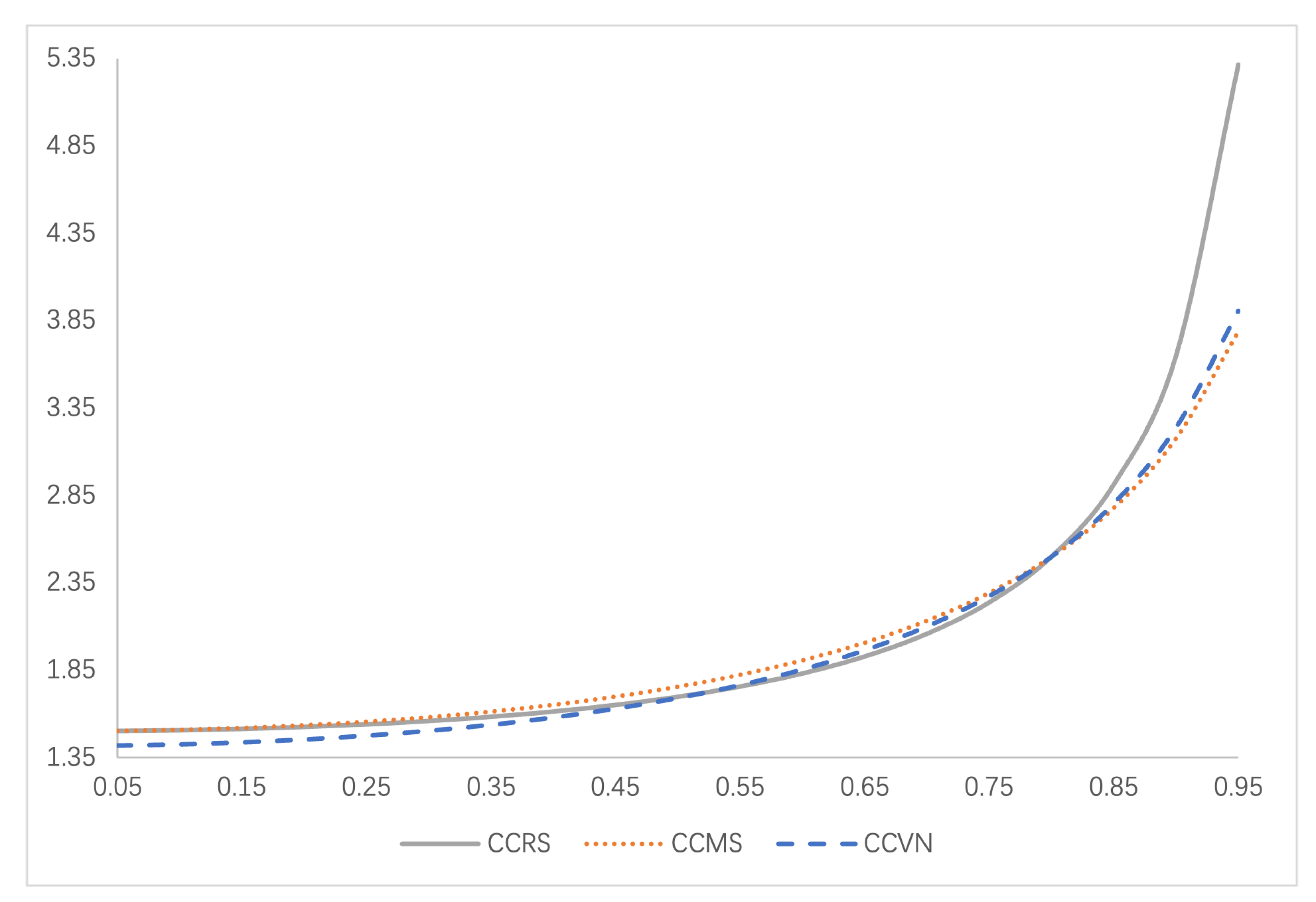

4.2. The Numerical Analysis of CCMS, CCRS, and CCVN

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate the changes and comparisons in the optimal retail price of SB products, while

Figure 12 and 13 present the differences and comparisons in the retail price of SB products. In this paper, the optimal profits of the retailer and the NB manufacturer are not discussed in detail because the corresponding results are overly complex and impractical for numerical illustration.

Observation 8. Under the situation that there is one environmental SB and one environmental NB, when the intensity of competition between SB is low, there is nearly no difference among the retail prices of SB products in the three types of channel-leadership structure. See

Figure 10.

Observation 9. Under the situation that there is one environmental SB and one environmental NB, as the consumer environmental sensitivity increases, the retail prices of SB and NB products increase. See

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

Observation 10. Under the situation that there are one environmental SB and one environmental NB, the retail price of NB products satisfy that

, if both the intensity of competition between SB and NB and the consumer environmental sensitivity are too low. the retail price of NB products satisfies that

, if the intensity of competition between SB and NB is high, and the consumer environmental sensitivity is low. See

Figure 12 and

Figure 13.

5. Managerial Implication

In contemporary business practice, both consumers and enterprises are making increasing efforts to protect the environment, leading to a steady expansion of the market for environmentally friendly products. Empirical evidence indicates that environmentally conscious consumers are willing to pay a premium for such products. For example, Conrad (2005) demonstrated that higher consumer environmental awareness results in greater willingness to pay, a finding consistent with the conclusions of this paper. Building on this evidence, our study examines consumer environmental sensitivity, defined as the influence of consumer environmental awareness on the profits of supply chain participants and the pricing of SB and NB products. The results show that, whether environmental production is adopted only for NB products or for both NB and SB products, the retail prices of both increase as consumer environmental awareness rises. Furthermore, when the NB manufacturer introduces environmental production for NB products, both the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s profits increase in response to growing consumer environmental awareness.

These findings indicate that consumer environmental awareness is a key factor influencing profitability in SB-NB supply chains. Firms can strategically incorporate consumer environmental awareness into their supply chain management to enhance product competitiveness and market positioning. Specifically, as our results show, when NB products are produced using environmentally friendly methods, both the retailer and the NB manufacturer benefit. This dual gain creates opportunities for higher value-added product offerings while simultaneously improving operational efficiency across the supply chain.

Furthermore, in a competitive environment where the retailer introduces an SB, the NB manufacturer should not only target environmentally conscious consumers but also capture demand from consumers with lower environmental awareness to remain competitive. For instance, if the NB manufacturer implements green production, it can employ marketing strategies to highlight the importance of environmental protection, thereby increasing product demand. In other words, by converting consumers with low environmental awareness into those with higher awareness, the NB manufacturer can stimulate additional demand and expand its market base.

Our study also provides managerial insights for NB manufacturers and SB-introducing retailers on addressing environmental issues in SB-NB competition from the perspectives of channel-leadership structure and competition intensity. When only NB products are produced using environmentally friendly methods, and both the competition intensity between the two brands and consumer environmental awareness are low, the Manufacturer-Stackelberg leadership structure consistently yields higher profitability for the NB manufacturer. Conversely, when both competition intensity and consumer environmental awareness are high, the Retailer-Stackelberg leadership structure benefits both the NB manufacturer and the retailer. For both parties, selecting the most suitable channel-leadership structure is therefore a critical operational management decision.

Although our results identify the optimal channel-leadership strategy under various scenarios, in practice it is often challenging to accurately assess competition intensity and consumer environmental awareness—particularly the former. Under such uncertainty, information sharing between the NB manufacturer and the retailer becomes essential. By cooperating to exchange market intelligence, both parties can more effectively determine the optimal channel-leadership structure for the entire supply chain, thereby achieving mutually beneficial outcomes.

6. Conclusion and Discussion

This paper evaluates the impact of consumer environmental awareness (CEA) on competition between store brands (SB) and national brands (NB) in a two-stage supply chain comprising one NB manufacturer and one retailer. Prior studies have shown that higher consumer environmental awareness increases consumers’ willingness to pay for environmentally friendly products (Chitra, 2007). In this study, we consider both price competition and product environmental levels. Two cases are analyzed in the model: (1) a traditional SB competing with an environmentally friendly NB, and (2) both SB and NB being environmentally friendly. Equilibrium outcomes are derived under three types of channel-leadership structures for each case: (1) Manufacturer-Stackelberg, (2) Retailer-Stackelberg, and (3) Vertical Nash. We further examine how different channel-leadership structures shape the decisions of supply chain participants, and how interactions among CEA, competition intensity, and leadership structure influence profits and strategic choices for both the NB manufacturer and the retailer.

The main findings indicate that, in the case where only NB products are environmentally friendly, CEA positively affects the profits of both the NB manufacturer and the retailer, as well as the retail prices of SB and NB products, the environmental levels of both products, and the wholesale price of NB products. CEA and competition intensity jointly determine the optimal channel-leadership structure. High competition intensity leads the retailer to set higher retail prices for both SB and NB products. Under the NB-only environmental production case, the Retailer-Stackelberg structure consistently ensures retailer profitability, whereas the Manufacturer-Stackelberg structure secures NB manufacturer profitability when both competition intensity and CEA are high. Conversely, when both competition intensity and CEA are low, both parties prefer the Retailer-Stackelberg structure. In the case where both SB and NB are environmentally friendly, CEA and competition intensity exert a positive influence on all key decision variables. Across all scenarios, our analysis provides optimal retail prices, environmental levels, and wholesale prices for decision-makers under different cases and leadership structures.

This study offers valuable insights into how CEA influences supply chain decision-making. Nevertheless, the model has certain limitations, particularly due to the assumption of deterministic demand. While such demand functions are common in analytical models, real-world demand is often influenced by uncertainty—for example, sales of raincoats decline when there are fewer rainy days. Addressing demand uncertainty is therefore a promising avenue for future research on SB-NB competition under CEA considerations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, YANG XIAO; Methodology, YANG XIAO; Modeling and formal analysis, YANG XIAO; Data curation, YANG XIAO; Software and numerical simulation, YANG XIAO and YUXIAO LIANG; Validation, YANG XIAO, YUXIAO LIANG and NAN SHEN; Writing—original draft preparation, YANG XIAO; Writing—review & editing (including grammar checking and language polishing), YANG XIAO, YUXIAO LIANG, and NAN SHEN. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

- Ailawadi, K.L.; Neslin, S.A.; Gedenk, K. (2001). Pursuing the value-conscious consumer: Store brands versus national brand promotions. Journal of Marketing, 65(1), 71–89.

- Assarzadegan, P.; Hejazi, S.R.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. (2024). A Stackelberg differential game theoretic approach for analyzing coordination strategies in a supply chain with retailer’s premium store brand. Annals of Operations Research, 336(3), 1519–1549.

- Cai, G.G.; Zhang, Z.G.; Zhang, M. (2009). Game theoretical perspectives on dual-channel supply chain competition with price discounts and pricing schemes. International Journal of Production Economics, 117(1), 80–96.

- Cheng, R.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ke, H. (2021). Impacts of store-brand introduction on a multiple-echelon supply chain. European Journal of Operational Research, 292(2), 652–662.

- Chitra, K. (2007). In search of the green consumers: A perceptual study. Journal of Services Research, 7(1), 173–191.

- Choi, S.C. (1996). Price competition in a duopoly common retailer channel. Journal of Retailing, 72(2), 117–134.

- Collins-Dodd, C.; Lindley, T. (2003). Store brands and retail differentiation: The influence of store image and store brand attitude on store own brand perceptions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 10(6), 345–352.

- Conrad, K. (2005). Price competition and product differentiation when consumers care for the environment. Environmental and Resource Economics, 31(1), 1–19.

- Diallo, M.F. (2012). Effects of store image and store brand price-image on store brand purchase intention: Application to an emerging market. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(3), 360–367.

- Gielens, K.; Ma, Y.; Namin, A.; Sethuraman, R.; Smith, R.J.; Bachtel, R.C.; Jervis, S. (2021). The future of private labels: Towards a smart private label strategy. Journal of Retailing, 97(1), 99–115.

- Hamdi, M. (2024). Sustainable packaging trends in the consumer packaged goods market. Harvard University.

- Hayyat, A. (2024). The effect of organizational green operations and digitalization to promote green supply chain performance. In Human Perspectives of Industry 4.0 Organizations (pp. 183–223). CRC Press.

- He, D., & Deng, X. (2020). Price competition and product differentiation based on the subjective and social effect of consumers’ environmental awareness. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(3), 716.

- Heydari, J., Govindan, K., & Basiri, Z. (2020). Balancing price and green quality in presence of consumer environmental awareness: a green supply chain coordination approach. International Journal of Production Research, 1-19.

- Huang, Z.; Feng, T. (2020). Money-back guarantee and pricing decision with retailer’s store brand. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 10189.

- Huang, H.; Ke, H.; Wang, L. (2016). Equilibrium analysis of pricing competition and cooperation in supply chain with one common manufacturer and duopoly retailers. International Journal of Production Economics, 178, 12–21.

- Jamali, M.B.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. (2018). A game theoretic approach for green and non-green product pricing in chain-to-chain competitive sustainable and regular dual-channel supply chains. Journal of Cleaner Production, 170, 1029–1043.

- Kadam, C. (2024). Green marketing strategies in developing and developed markets. University of Vaasa.

- Krishnan, V.; Nusraningrum, D.; Prebakarran, P.N.; Wahid, S.D.M. (2024). Fostering consumer loyalty through green marketing: Unveiling the impact of perceived value in Malaysia’s retail sector. Journal of Ecohumanism, 3(8), 4318-4335.

- Kurata, H.; Yao, D.Q.; Liu, J.J. (2007). Pricing policies under direct vs. indirect channel competition and national vs. store brand competition. European Journal of Operational Research, 180(1), 262–281.

- Li, F.; Xiong, H. (2025). Green supply chain decision-making considering fair concerns and consumer environmental mindset. Heliyon, 11(5).

- Li, W.; Chen, J. (2018). Pricing and quality competition in a brand-differentiated supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 202, 97–108.

- Liu, Z.L.; Anderson, T.D.; Cruz, J.M. (2012). Consumer environmental awareness and competition in two-stage supply chains. European Journal of Operational Research, 218(3), 602–613.

- Madani, S.R.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. (2017). Sustainable supply chain management with pricing, greening and governmental tariffs determining strategies: A game-theoretic approach. Computers & Industrial Engineering, 105, 287–298.

- Mookherjee, S.; Malampallayil, S.; Mohanty, S.; Tran, N.X. (2024). Pandemic-led brand switch: Consumer stickiness for private-label brands. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 23(6), 2767–2780.

- Ndlovu, S.G. (2024). Private label brands vs national brands: New battle fronts and future competition. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2321877.

- Private Label Manufacturers Association. PLMA’s 2025 Annual Private Label Trade Show. Available online: https://plma.com/events/plmas-2025-annual-private-label-trade-show (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Phonthanukitithaworn, C.; Srisathan, W.A.; Worakittikul, W.; Inthachack, M.; Pancha, A.; Naruetharadhol, P. (2024). Conceptualising the effects of green supply chain on firms’ propensity for responsible waste disposal practices in emerging markets. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 17(1), 429–447.

- PLMA. (2025, March 24). Sales of U.S. store brands surged in 2024. Private Label Manufacturers Association.

- Ranjan, A.; Jha, J.K. (2019). Pricing and coordination strategies of a dual-channel supply chain considering green quality and sales effort. Journal of Cleaner Production, 218, 409–424.

- Ranjbar, Y.; Sahebi, H.; Ashayeri, J.; Teymouri, A. (2020). A competitive dual recycling channel in a three-level closed loop supply chain under different power structures: Pricing and collecting decisions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 272, 122623.

- SAIDI, D.; Ait Bassou, A.; El Alami, J.; Hlyal, M. (2024). Sustainability and resilience analysis in supply chain considering pricing policies and government economic measures. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications, 15(1), 123–136.

- Wei, J.; Zhao, J. (2011). Pricing decisions with retail competition in a fuzzy closed-loop supply chain. Expert Systems with Applications, 38(9), 11209–11216.

- Wu, C.H.; Chen, C.W.; Hsieh, C.C. (2012). Competitive pricing decisions in a two-echelon supply chain with horizontal and vertical competition. International Journal of Production Economics, 135(1), 265–274.

- Xiao, Y.; Kurata, H. (2023, November). Optimizing Pricing Strategies in Dual-Channel Closed-Loop Supply Chains: An Analysis of Manufacturers’ Corporate Social Responsibility Investment. In The International Conference on Smart Manufacturing, Industrial & Logistics Engineering (SMILE) (pp. 813–830). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Yang, H.; Chen, W. (2018). Retailer-driven carbon emission abatement with consumer environmental awareness and carbon tax: Revenue-sharing versus cost-sharing. Omega, 78, 179–191.

- Yang, H.; Luo, J.; Wang, H. (2017). The role of revenue sharing and first-mover advantage in emission abatement with carbon tax and consumer environmental awareness. International Journal of Production Economics, 193, 691–702.

- Yu, Y.; Han, X.; Hu, G. (2016). Optimal production for manufacturers considering consumer environmental awareness and green subsidies. International Journal of Production Economics, 182, 397–408.

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; You, J. (2015). Consumer environmental awareness and channel coordination with two substitutable products. European Journal of Operational Research, 241(1), 63–73.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).