1. Introduction

Tobacco use, encompassing both smoked and smokeless forms, is a significant yet under-documented public health issue among justice-involved populations. Incarcerated individuals are particularly vulnerable to a range of health risks due to the widespread use of harmful substances, including tobacco, areca nut, alcohol, narcotics, misused prescription drugs, and synthetic compounds- all of which contribute substantially to the health burden within correctional facilities. Globally, people who have been incarcerated are at high risk for smoking and its health problems, mainly due to limited access to prevention and treatment programs [

1]. The carceral environment itself fosters high tobacco consumption due to the stress of incarceration, the stigma associated with justice involvement, and the challenges of reintegrating into society after release. India reportedly has 1,382 prisons, with a total capacity of 332,782 inmates. However, the inmate population often exceeds full capacity [

2]. Such restrictive living conditions tend to compound existing risk behaviors and increase exposure to active and passive smoking.

A survey conducted in the central jail of Bangalore revealed a very high tobacco smoking prevalence at 92.6% among 1352 inmates who consumed tobacco [

3]. Smoking prevalence in prisons is at least two to three times higher than in the general population [

4].

Tobacco use is a leading cause of poor oral health in these settings and is closely associated with dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral mucosal lesions [

5]. Both smoked and smokeless tobacco products are major etiological factors in the development of oral health problems, including oral submucous fibrosis, leukoplakia, and lichen planus. Tobacco products, including beedis and cigarettes, are readily available in prison canteens, and there is no enforced restriction on smoking within the facility, highlighting the urgent need for public health interventions. Without access to effective tobacco-dependence treatment during incarceration or post-release, the majority of individuals are likely to relapse, perpetuating the cycle of addiction [

6].

Health is a fundamental human right, yet prisoners within the Indian Criminal Justice System remain a vulnerable and underserved population, requiring urgent attention in oral health care, health promotion, and tobacco cessation. The lack of targeted interventions exacerbates poor health outcomes and places a considerable strain on public healthcare systems after incarceration. This challenge is further compounded by limited access to oral healthcare facilities and a shortage of dental professionals willing to serve within the prison system [

7].

While numerous studies have explored the prevalence of medical diseases among incarcerated populations, there is a notable gap in research addressing oral health, particularly within the context of tobacco use and motivation to quit. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in Navi Mumbai to comprehensively assess the patterns of tobacco consumption and its impact on oral health among incarcerated individuals. By focusing on a central prison in this area, this study provides insights into an understudied aspect of public health, highlighting the oral health disparities in a vulnerable and marginalized population. The unique scope of this research bridges a critical knowledge gap and lays the groundwork for targeted interventions and policy development in correctional healthcare.

2. Objectives

Evaluate the demographic characteristics of the inmates and examine the patterns of tobacco use, including both smoked and smokeless forms

Estimate the inmates’ readiness and motivation to quit tobacco use

Assess the prevalence of oral health issues, specifically, dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral mucosal lesions and explore their association with tobacco use.

3. Study Design

This study was designed following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines and was conducted from September 2023 to December 2023 following ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee of XXXXX(XXXXX/XXX/XXX/XXXX/XXX-P). Prior approval for the study was obtained from the jail authorities. Informed consent was secured from the prison inmates, and participation in the study was entirely voluntary.

4. Study Population

The study was conducted at a central prison in Navi Mumbai, India. Out of 3333 total eligible inmates, 3321 participated, while 12 were excluded due to non-consent. Participants were clearly informed that their participation was voluntary and that refusal or nonparticipation would have no impact on their treatment, rights, or privileges within the prison. All male inmates aged 21 years and above who were incarcerated during the study period and provided informed consent were included in the study.

5. Study Setting

The dental professionals responsible for screening the inmates received prior training in diagnosing oral diseases and interpreting indices under the supervision of three senior faculty members.

The data collection was carried out systematically across the entire prison, with each barrack being covered in an organized manner. Over four months, each prisoner was interviewed and examined individually in the respective prison barracks. Each interview and examination lasted 10 to 15 minutes. One-on-one interviews were conducted, with the dental professional and the prison inmate seated across from each other at a bench. Three interviews were carried out simultaneously within the barracks, under the supervision of senior faculty members and the presence of security personnel. Adequate spatial separation was ensured to maintain participant privacy and uphold the confidentiality of responses. After the completion of each examination, the prisoner was instructed to return to their respective cell.

6. Conceptual Framework

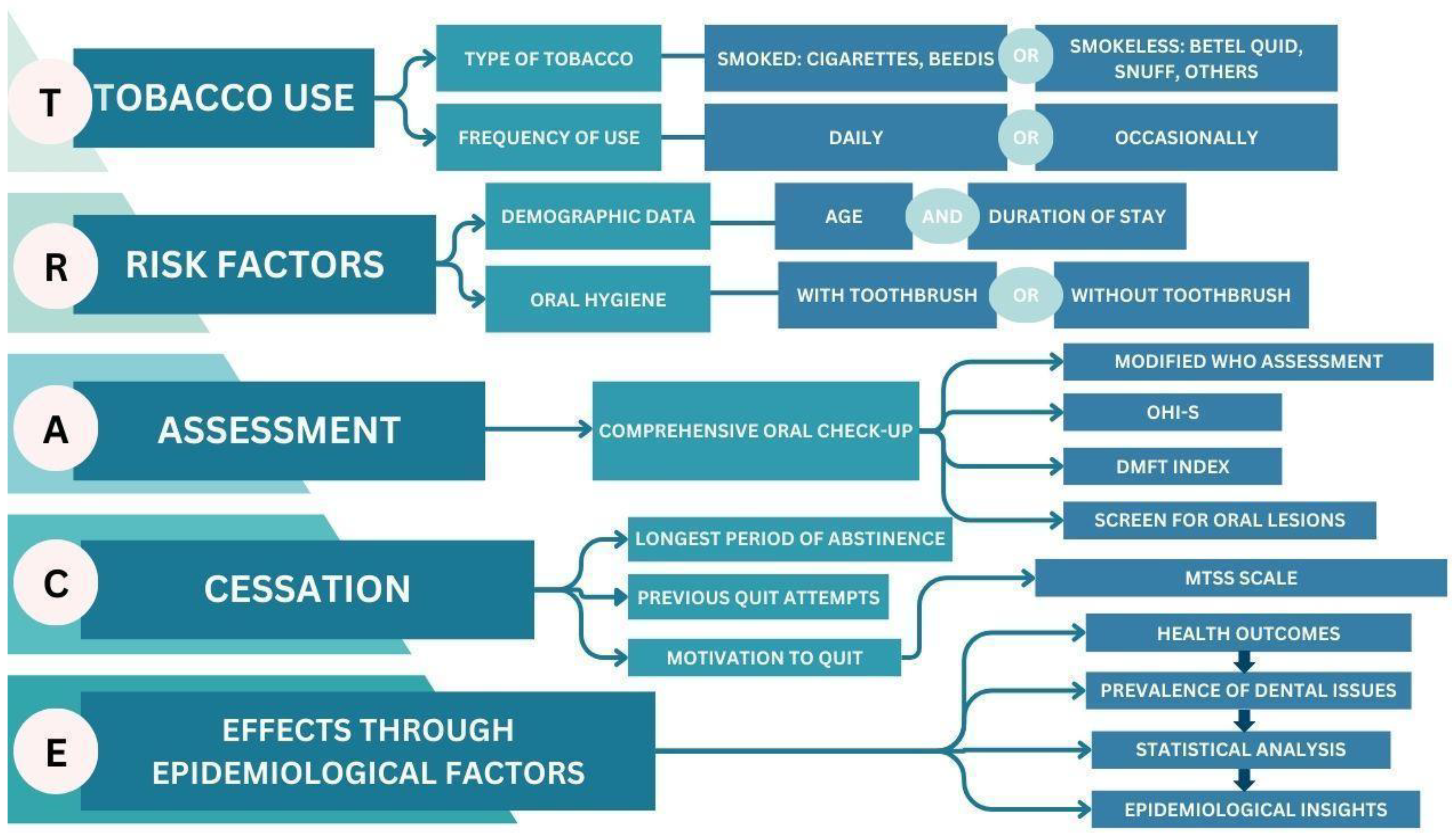

This descriptive cross-sectional study used a novel TRACE (Tobacco Use, Risk Factors, Assessment, Cessation, Effects through Epidemiological Factors) framework to examine the inmates, as described in

Figure 1. It systematically identifies and analyzes the patterns of tobacco use, associated risk factors, cessation motivation, and the impact of these variables on the oral health outcomes of incarcerated individuals.

The TRACE framework consists of an interview and oral examination. Tobacco use patterns and demographic information, such as age and duration of incarceration, were collected.

The study also evaluated tobacco use among inmates, including both smoked and smokeless forms. Additionally, a modified version of the Motivation to Stop Scale (MTSS) was employed to assess inmates’ readiness and motivation to quit tobacco use, including previous quit attempts and their desire to quit in the future.

The clinical assessment was done using a mouth mirror, explorer, and WHO probe under natural light to assess the use of the Decayed, Missing, Filled Teeth (DMFT) index and the Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified (OHI-S). The DMFT index allowed for classifying the participants’ dental health based on the presence of decayed, missing, and filled teeth. The Oral Hygiene Index- Simplified (OHI-S) assessed the level of oral hygiene based on debris and calculus scores.

7. Sample Size

A pilot study was initially conducted among 50 inmates to estimate the effect size and variability of key parameters. Using the data obtained from the pilot and G*Power Statistics Software (version 3.1.9.7), the minimum required sample size was determined to be 3333 inmates to achieve adequate statistical power.

A total population sampling technique, consistent with WHO recommendations for research in closed populations such as prisons, was employed, wherein all eligible inmates (N=3333) within the central prison were invited to participate. Out of these, 3321 inmates provided informed consent and were enrolled in the study.

8. Statistical Analysis

The data obtained were entered in Microsoft Excel and analyzed statistically using the SPSS software, version 21; SPSS Inc., (Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were computed, which included percentages, means, and standard deviations. The normality of the data distribution was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used to check for any significant differences in the DMFT and OHI-S scores. Multiple linear regression was also performed to assess the associated factors for DMFT and OHI-S. For all the tests, confidence level and level of significance were set at 95% and 5%, respectively.

9. Results

9.1. Demographic Characteristics and Tobacco Consumption

In line with the predefined study objectives, the demographic characteristics of the participants were assessed alongside their tobacco consumption profiles. The study reports the prison population with a mean age of 41.76 ± 9.63 years. 45.1% of participants were between the ages of 41 and 50. Regarding the length of incarceration, around 45.2% of the participants had been incarcerated for 1-5 years.

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the study population.

Tobacco use was prevalent among 53.1% of the study population. Of these, 24.0% used betel quid, 13.6% smoked cigarettes, and 11.0% used toombak (snuff). The remaining 46.9% of inmates were non-users of tobacco products.

As for oral hygiene practices, 68.1% of the inmates reported brushing their teeth with a toothbrush, while 31.9% did not use a toothbrush to maintain oral hygiene.

9.2. Motivation to Quit Tobacco Use

In addressing the second objective of this study, the inmates’ readiness and motivation to quit tobacco use was examined.

Table 2 summarizes the patterns of tobacco use and quitting behaviors among 1765 individuals, including users of cigarettes, beedis, betel quid, snuff, and other smokeless tobacco products. The majority (82.8%) reported that the most prolonged period they have gone without using tobacco was less than one day, while 0.3% had gone twelve months or more without it. Nearly half (48.0%) had attempted to quit once, and 27.5% had never tried. 76.3% of the participants wanted to quit, while 23.7% did not wish to stop. Regarding motivation to quit, 29.5% intended to stop within the next three months, and 13.7% hoped to stop soon, while 23.7% had no intention of quitting. Only 0.2% of tobacco users firmly intended to stop within the next month. These results highlight varied levels of motivation and quitting attempts within the group.

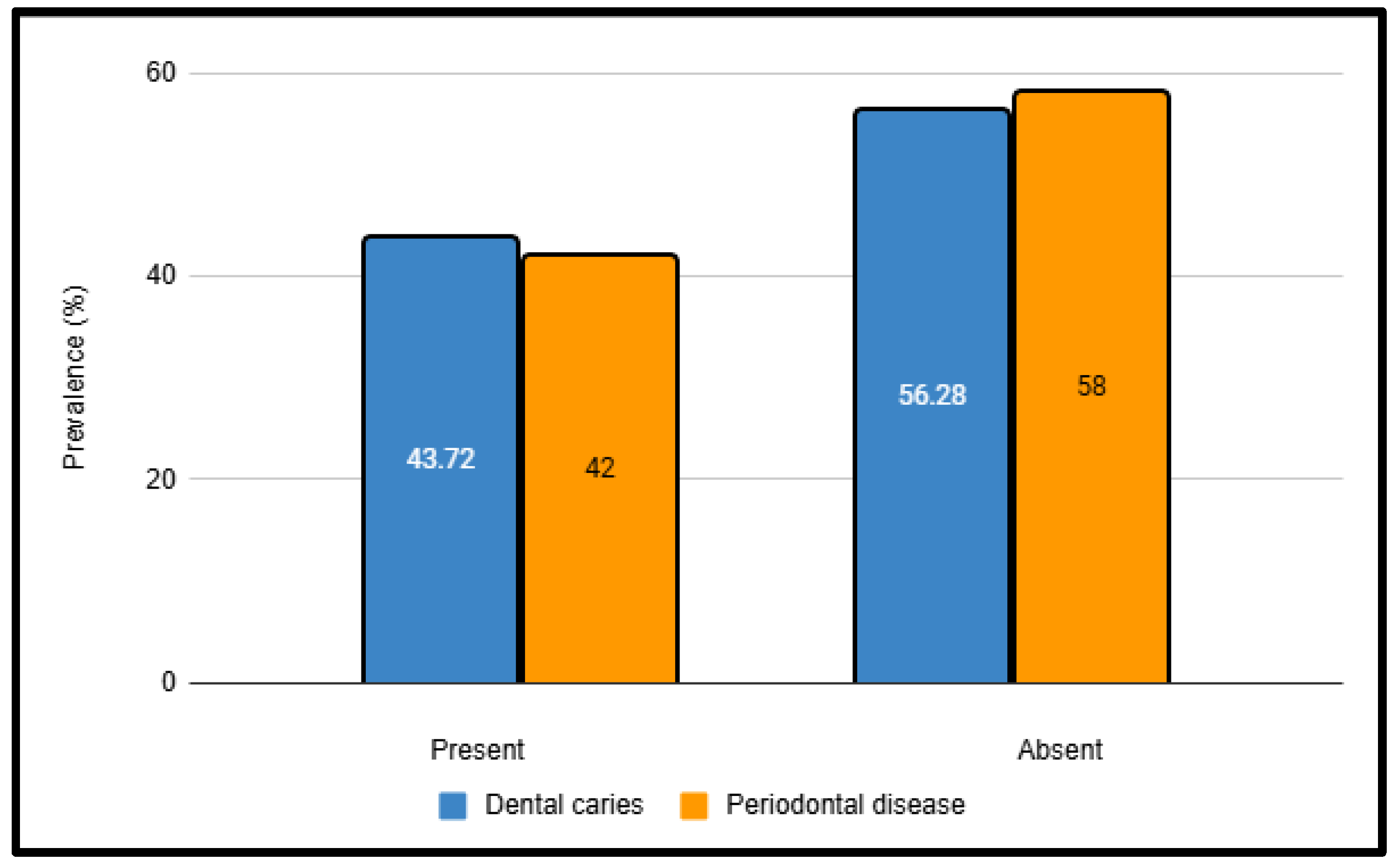

9.3. Prevalence of Dental Caries and Periodontal Disease

The third objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of dental caries, periodontal disease, and oral mucosal lesions and explore their association with tobacco use. The prevalence of dental caries was found to be 43.72%, while that of periodontal disease was 46.04% (

Figure 2). The Decayed, Missing, Filled Teeth (DMFT) index revealed that the mean number of decayed teeth (DT) was highest in the 31-40 years age group (5.15 ± 3.54), and the mean number of missing teeth (MT) increased significantly with age, peaking at 5.81 ± 1.66 in the >50 years age group. Filled teeth (FT) were significant across all age groups. The DMFT index significantly increased with age, with the highest score observed in the >50 years group (10.73 ± 2.14). Significant differences were observed between age groups for both the DMFT and Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified (OHI-S) scores (p < 0.001), with older inmates exhibiting poorer oral health and hygiene (

Table 3).

9.4. Oral Health Outcomes

Poor oral hygiene was common, particularly among older inmates, with the highest Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified (OHI-S) scores observed in the >50 years age group. Statistically significant differences were observed across the age groups (p < 0.001) for both the Debris Index-Simplified (DI-S) and Calculus Index-Simplified (CI-S), indicating poorer oral hygiene among older inmates, as seen in

Table 3. Tobacco consumption varied by age, with younger inmates more likely to use tobacco than older inmates.

Table 4 presents the findings from a multiple linear regression analysis examining the relationship between demographic variables and oral health indicators —the Decayed Missing Filled Teeth (DMFT) Index and the Oral Hygiene Index-Simplified (OHI-S) Index —among prisoners. The analysis revealed that both OHI-S and DMFT are significantly associated with age (p < 0.001) and oral hygiene practices (p < 0.001), showing dependencies of 15.1% and 0.3%, respectively. The prevalence of tobacco use was significantly associated with poorer oral health outcomes, with smokers and users of smokeless tobacco showing higher levels of dental caries and periodontal disease.

9.5. Oral Mucosal Lesions

A total of 86 inmates, accounting for 4.8% of total tobacco users, presented with oral mucosal lesions. The most common lesion was oral submucous fibrosis, observed in 2.3% of tobacco users, followed by leukoplakia (0.8%), candidiasis (0.6%), ulceration (0.5%), and lichen planus (0.3%) (

Table 5).

10. Discussion

The results of this study help analyze the tobacco consumption profiles, motivation to quit tobacco, and oral health status among incarcerated people using the TRACE (Tobacco Use, Risk Factors, Assessment, Cessation and Effects through Epidemiology) framework. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine such trends in the central jail of Navi Mumbai. Tobacco use in correctional facilities remains a significant concern, with reported prevalence rates ranging from 50% to 83% [

1]. In this study, 53.1% of inmates reported tobacco use, with 39.5% consuming smokeless forms of tobacco. This disproportionate rate of tobacco use is linked to a variety of factors, including the stressful and restrictive nature of the carceral environment, limited healthcare access, and the social and economic vulnerabilities faced by such individuals.

The study population consisted of 3321 male inmates, with a mean age of 41.76 ± 9.63 years. A substantial proportion (45.1%) were aged between 41 and 50 years, and 45.2% had been incarcerated for 1–5 years. The higher prevalence of tobacco use in this age group could be due to more prolonged exposure to tobacco before incarceration and habitual coping mechanisms formed over time.

Tobacco use in the form of beedi, cigarettes, snuff, betel quid, and other smokeless forms was observed in 1765 inmates (53.1%), likely driven by factors such as boredom, stress relief, peer influence, or a combination of these. Despite the prohibition of tobacco in Indian jails, the study found a significant number of prisoners engaging in this habit with access to these substances. This highlights potential gaps in law enforcement and prison management by security personnel. These findings align with those of Veera Reddy et al., who reported that 42.8% of prisoners in Karnataka jails had similar adverse tobacco habits [

8].

The study also assessed inmates’ motivation to quit tobacco, using the MTSS (Motivation to Stop Scale), adapted from Dawkins et al. [

9]. This revealed that 76.3% of tobacco users expressed a desire to quit, reflecting a high level of motivation to stop despite the challenges faced in the correctional environment. However, the availability of cessation resources remains a concerning barrier, with only a tiny proportion of inmates having access to such programs [

10].

The prevalence of dental caries in this study was 43.72%, which is relatively lower compared to other studies reporting higher rates of untreated dental conditions [

11]. The DMFT index is a widely used method to assess dental caries prevalence and treatment needs. A 2012 study in Karnataka’s central prison reported a mean DMFT score of 5.26, indicating a high caries burden [

12]. Similarly, a 2022 study in Uttarakhand found a mean DMFT of 5.40 ± 6.49, highlighting poor oral hygiene, limited dental care, and neglect as key contributors to the oral health challenges in incarcerated populations [

13]. This study is consistent with others that reported high DMFT scores increasing with age; however, the higher filled teeth index suggests that the sustained efforts of the satellite center located within this central jail may have contributed to reducing the burden of oral health issues among inmates. These findings underscore the need to establish additional satellite centers for dental health across all jails to further address oral health disparities.

Periodontal disease was observed in 46.04% of inmates, representing nearly half of the study population and highlighting the compounded impact of tobacco use on oral health. In contrast, previous studies have reported periodontal disease rates as high as 97%, indicating significant variability in prevalence [

14].

Oral mucosal lesions (OML) were identified in 86 (4.8%) inmates out of the 1765 tobacco users, with the most prevalent conditions being oral submucous fibrosis (2.3%) and leukoplakia (0.8%). These findings align with a study conducted in Bhopal’s central jail by Arjun et al., which reported similar lesions as the most common, though at a higher prevalence of 34.8% in their population [

15].

Our findings underscore the urgent need for tobacco cessation programs tailored to such populations. Without adequate treatment, the vast majority of smokers relapse upon reentry into society, as tobacco use remains prevalent even after release [

16]. The risk of relapse remains high due to barriers such as lack of access to healthcare, tobacco retail density in communities, and social stigma.

Several limitations must be acknowledged. The reliance on self-reported data for tobacco use may introduce bias, as inmates could underreport consumption due to social desirability. The study’s cross-sectional nature restricts the ability to infer causality between tobacco use and oral health outcomes. A longitudinal study would provide more robust evidence of causality. Moreover, the study exclusively focused on adult male prisoners, limiting the findings’ applicability to female inmates or juveniles. Tobacco use behaviors and oral health outcomes are also influenced by dynamic social and environmental factors, which could lead to variations over time. Lastly, the research was conducted in a single facility with a dental satellite center, restricting the generalizability of the findings to other correctional settings or populations without similar healthcare infrastructure.

11. Future Implications

Future research should utilize the TRACE (Tobacco Use, Risk Factors, Assessment, Cessation, and Effects through Epidemiological Factors) framework in prisons across India to address the current scarcity of literature in this realm. This framework can guide studies that focus on expanding tobacco cessation programs within correctional facilities, providing comprehensive support through nicotine replacement therapies, counseling, and peer support. Improving access to routine oral healthcare, particularly by establishing dental satellite centers in more prisons, is crucial for addressing the high prevalence of dental caries and periodontal disease. Additionally, enhancing oral health education tailored to the needs of incarcerated individuals can foster better self-care practices and reduce tobacco use. Longitudinal studies based on the TRACE framework are necessary to assess the long-term impact of tobacco cessation and oral health interventions. Integrating such programs into correctional healthcare policies, focusing on post-release care, will ensure continuity of care and reduce the long-term public health burden.

12. Conclusions

This study maps the oral health and tobacco risk profiles among inmates in a central prison in Navi Mumbai, revealing that 43.72% suffer from dental caries and 46.04% from periodontal disease. Notably, 53.1% of inmates used some form of tobacco, and 76.3% of them expressed a willingness to quit, underscoring the need for effective cessation programs.

Prisons, as part of the Indian Criminal Justice System, must evolve from punitive institutions to centers of rehabilitation, integrating comprehensive oral health care and targeted cessation initiatives. By addressing these disparities with evidence-based reforms, correctional facilities can enhance inmate well-being and reduce the broader public health burden. This study bridges a critical research gap and advocates for systemic change in correctional healthcare.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.P.N. and V.K.; methodology, V.K and M.V.; software, M.U., M.D.; validation, V.K., M.D., M.V.; formal analysis, K.P.N. and Z.D.B.; investigation, V.K., K.P.N., D.D..; resources, M.V., D.D., and A.S.; data curation, A.S., R.T., and Z.D.B.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K., A.S.; writing—review and editing, Z.D.B., K.P.N., N.M.; visualization, N.M.,D.D, R.T.; supervision, K.P.N., M.V.,V.K.; project administration, K.P.N., D.D..; funding acquisition, Z.D.B., N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Dr G.D. Pol Foundation Y.M.T. Dental College and Hospital, Navi Mumbai. (protocol code YMTDC/IEC/OUT/2024/272-P).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical and legal restrictions associated with research on incarcerated individuals. Data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with prior approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee and relevant prison administration.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the prison authorities for their cooperation and support in facilitating this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gorrilla AA, Kaye JT, Pavlik J, et al. A Call for Health Equity in Tobacco Control and Treatment for the Justice-Involved Population. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2024;67(4):631-636. [CrossRef]

- Spaulding AC, Eldridge GD, Chico CE, et al. Smoking in Correctional Settings Worldwide: Prevalence, Bans, and Interventions. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2018;40(1):82-95. [CrossRef]

- Naik S, Ramachandra S, Vadavadagi S, Dhananjaya K, Khanagar S, Kumar A. Assessment of effectiveness of smoking cessation intervention among male prisoners in India: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of International Society of Preventive and Community Dentistry. 2014;4(5):110. [CrossRef]

- Cropsey K, Eldridge G, Weaver M, Villalobos G, Stitzer M, Best A. Smoking cessation intervention for female prisoners: Addressing an urgent public health need. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:1894–901.

- Clare JH. Dental Health Status, Unmet Needs, and Utilization of Services in a Cohort of Adult Felons at Admission and After Three Years Incarceration. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2002;9(1):65-76. [CrossRef]

- de Andrade D, Kinner SA. Systematic review of health and behavioral outcomes of smoking cessation interventions in prisons. Tobacco Control. 2016;26(5):495-501.

- Tiwari R, Megalamanegowdru J, Agrawal R, Gupta A, Parakh A, Chandrakar M. Using PUFA Index Oral Health in Correctional Facilities: A Study on Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Prisoners in Central India Review Articles in Dentistry; Chettinad Health City Medical Journal, 2014; 3(3):109-114.

- Reddy V, Kondareddy CV, Siddanna S, Manjunath M. A survey on oral health status and needs of life-imprisoned inmates in central jails of Karnataka, India. International Dental Journal 2012;62:27-32.

- Dawkins L, Ford A, Bauld L, Balaban S, Tyler A, Cox S. A cross-sectional survey of smoking characteristics and quitting behaviour from a sample of homeless adults in Great Britain. Addictive behaviors. 2019 Aug 1;95:35-40.

- Valera P, Reid A, Acuna N, Mackey D. The smoking behaviors of incarcerated smokers. Health Psychology Open. 2019;6(1). [CrossRef]

- Fotedar S, Chauhan A, Bhardwaj V, Manchanda K, Fotedar V. Association between oral health status and oral health-related quality of life among the prison inmate population of Kanda model jail, Shimla, Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian Journal of Public Health. 2016;60(2):150.

- Reddy V, Kondareddy CV, Siddanna S, Manjunath M. A survey on oral health status and treatment needs of life-imprisoned inmates in central jails of Karnataka, India. Int Dent J 2012;62:27–32. [CrossRef]

- Balkrishna A, Singh K, Sharma A, Parkar SM, Oberoi G. Oral health among prisoners of District Jail, Haridwar, Uttarakhand, India-A cross-sectional study. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 2022;24:41–7.

- Dayakar M, Shivprasad D, Pai P. Assessment of periodontal health status among prison inmates: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Indian Society of Periodontology 2014; 18(1):74-77. [CrossRef]

- Arjun TN, Hongal S, Sahu RN, Saxena V, Saxena E, Jain S. Assessment of oral mucosal lesions among psychiatric inmates residing in central jail, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India: A cross-sectional survey. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 2014; 56(3): 265-270.

- Frank MR, Blumhagen R, Weitzenkamp D, et al. Tobacco Use Among People Who Have Been in Prison: Relapse and Factors Associated with Trying to Quit. Journal of Smoking Cessation. 2017;12(2):76-85. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).