Submitted:

21 August 2025

Posted:

22 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

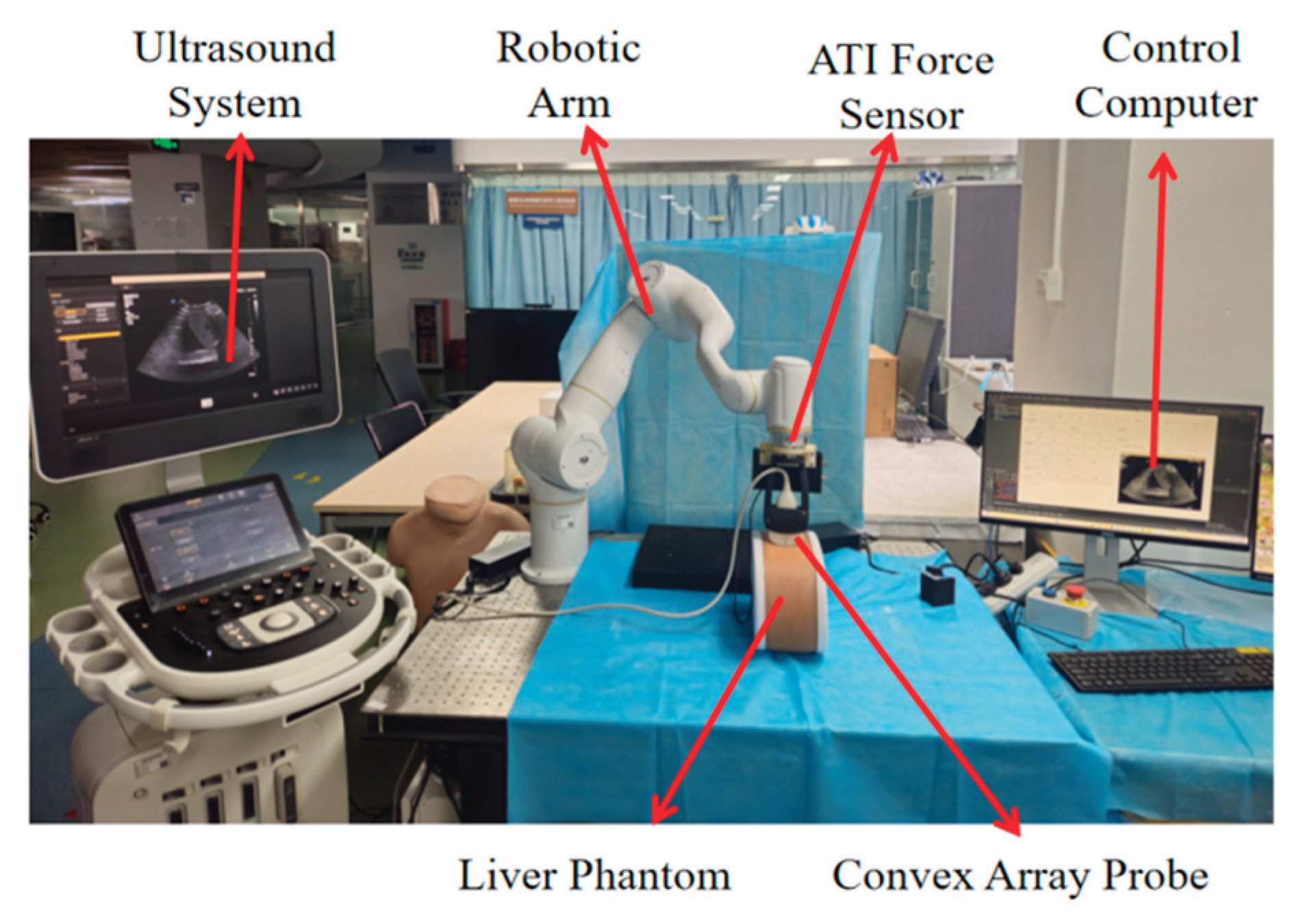

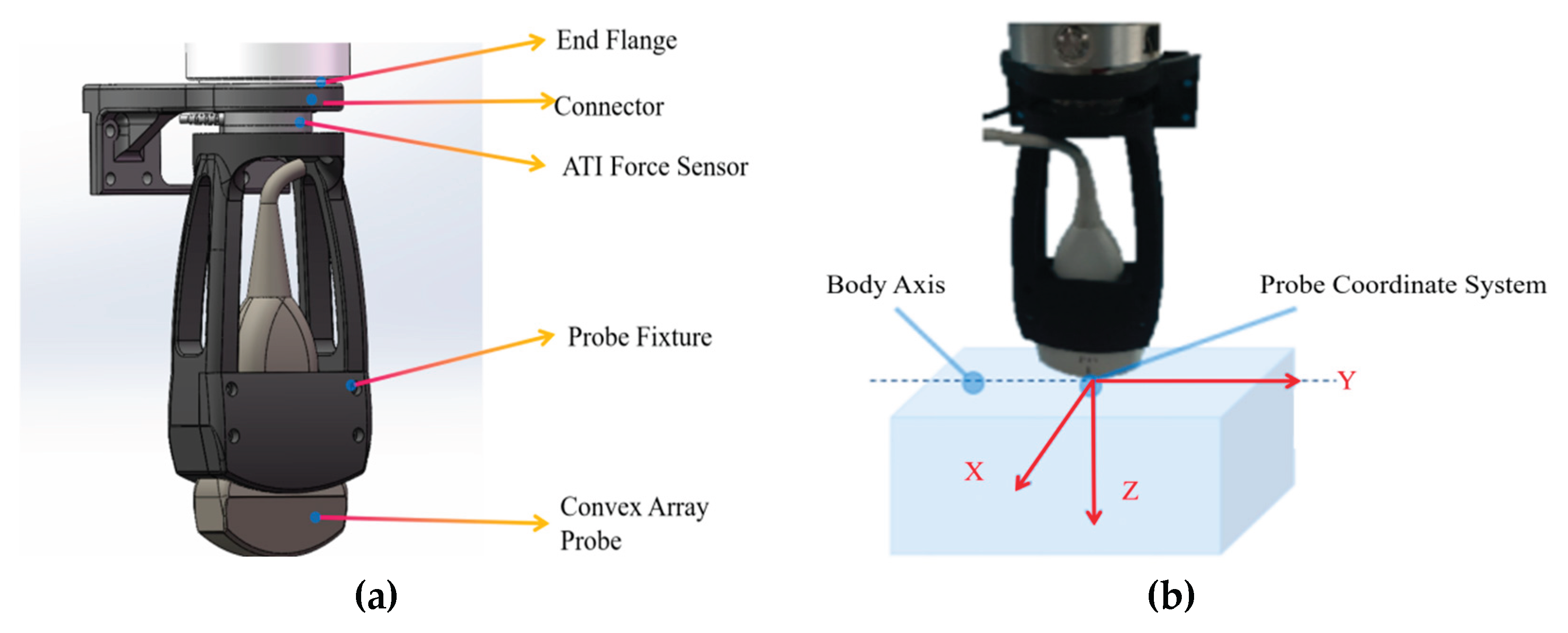

2.1. Robotic Ultrasound Scanning System Construction

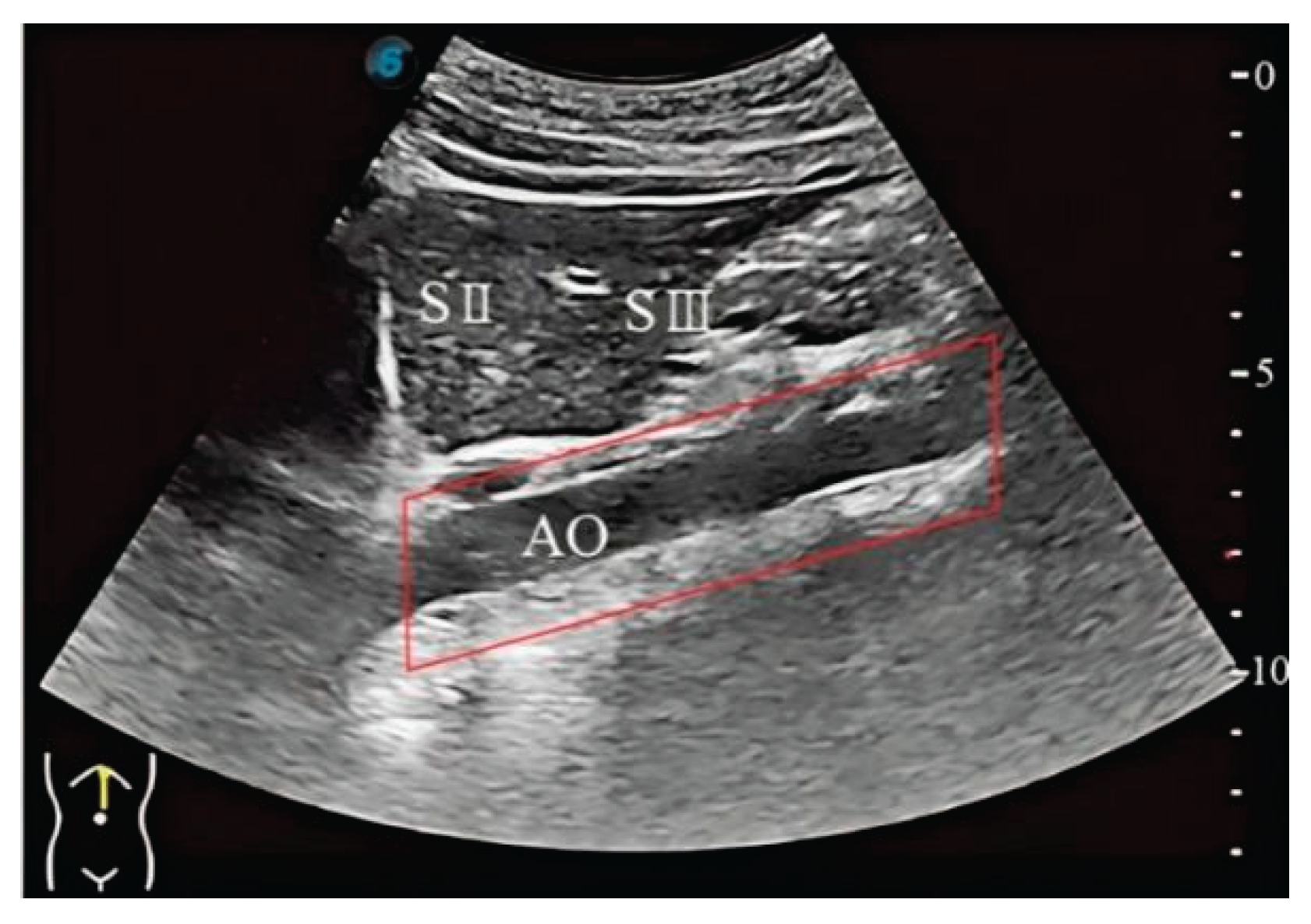

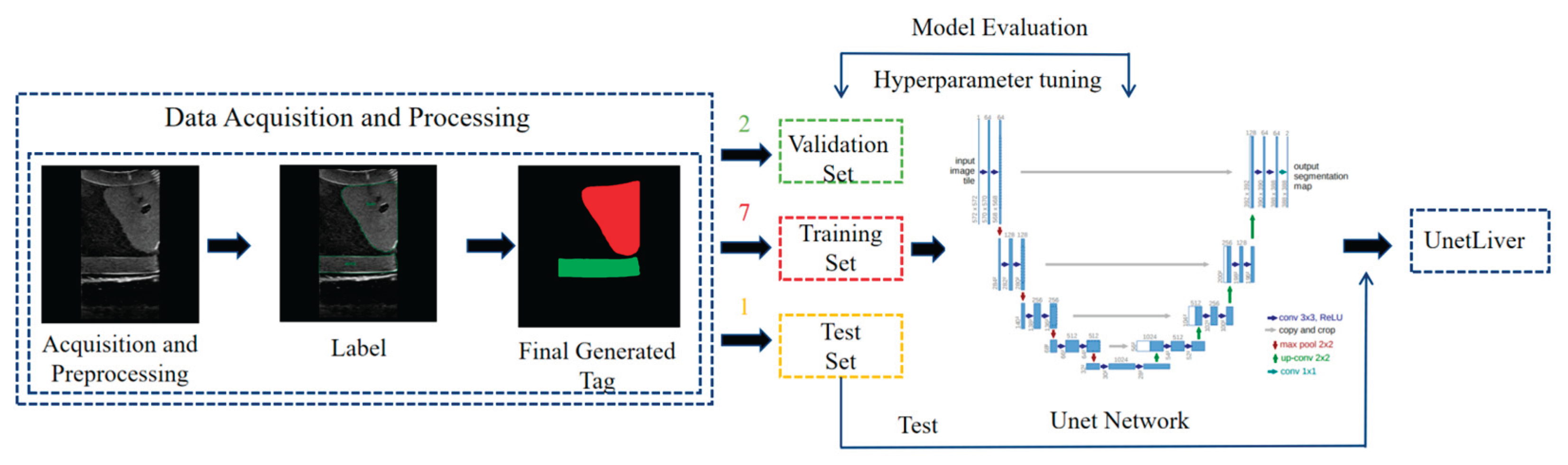

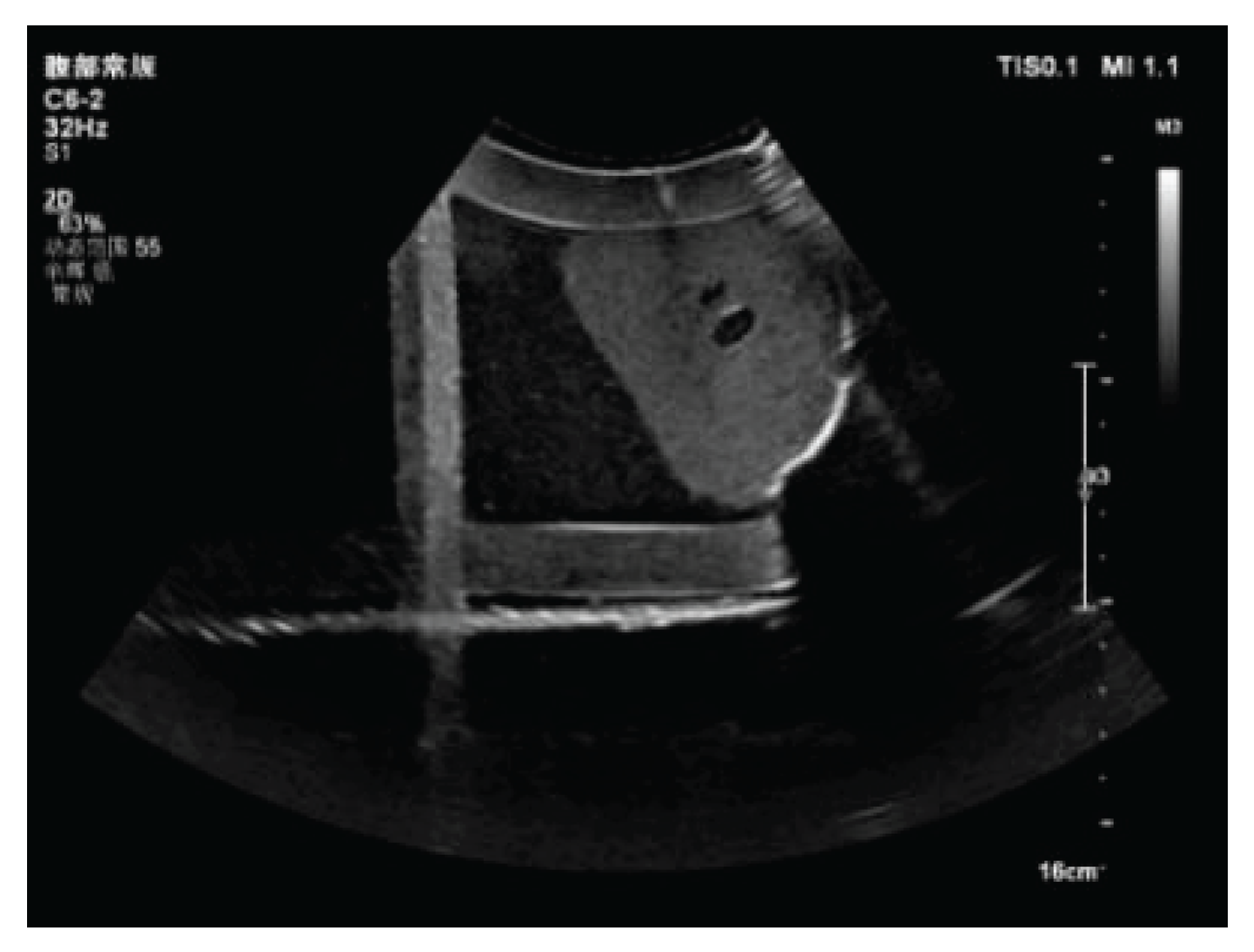

2.2. Liver Standard Plane Localization

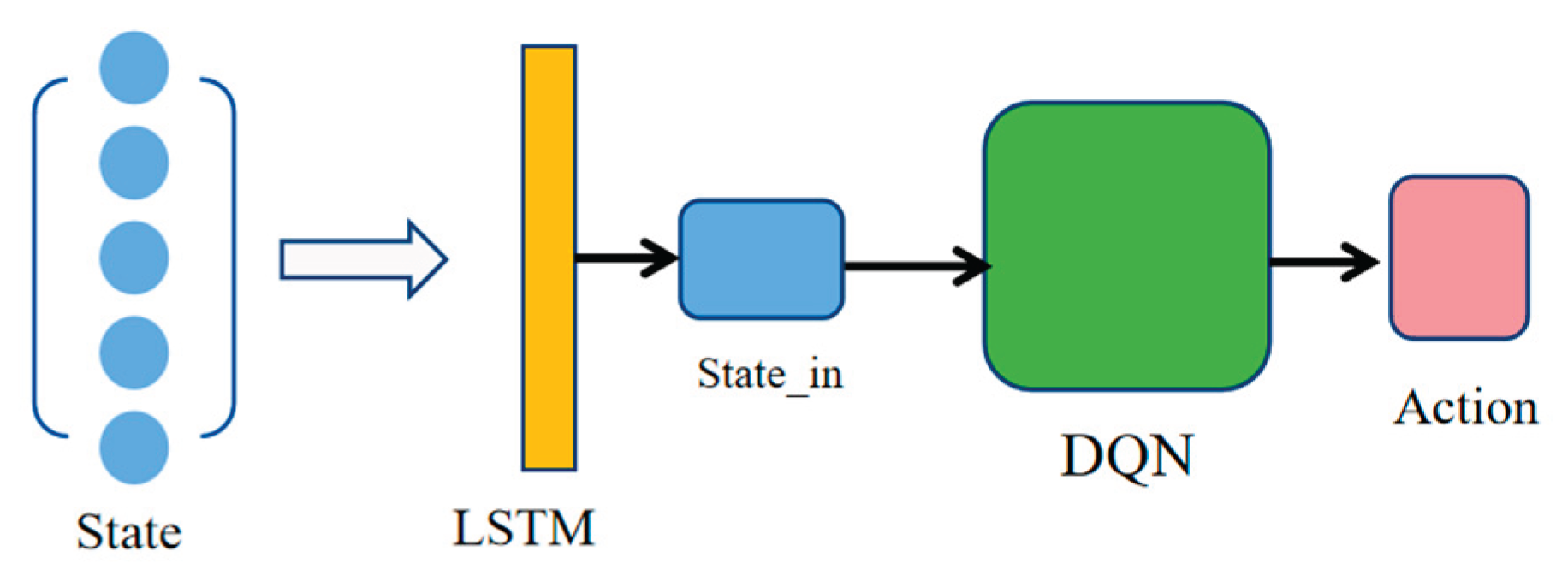

2.3. Construction and Training of the Reinforcement Learning Agent

3. Results

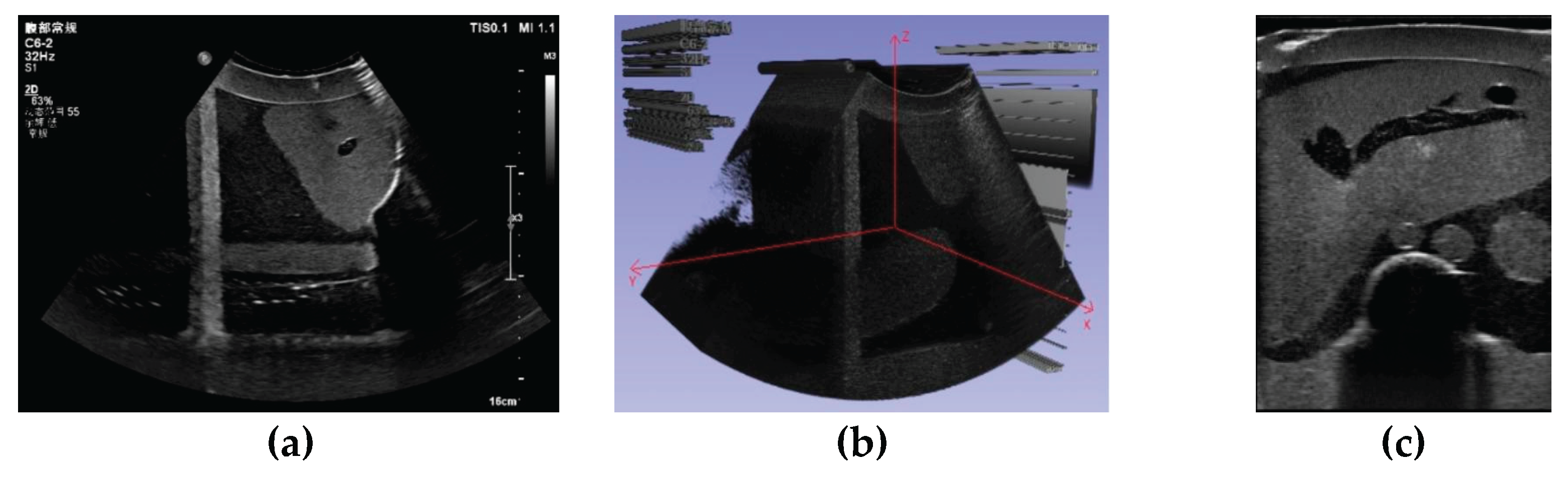

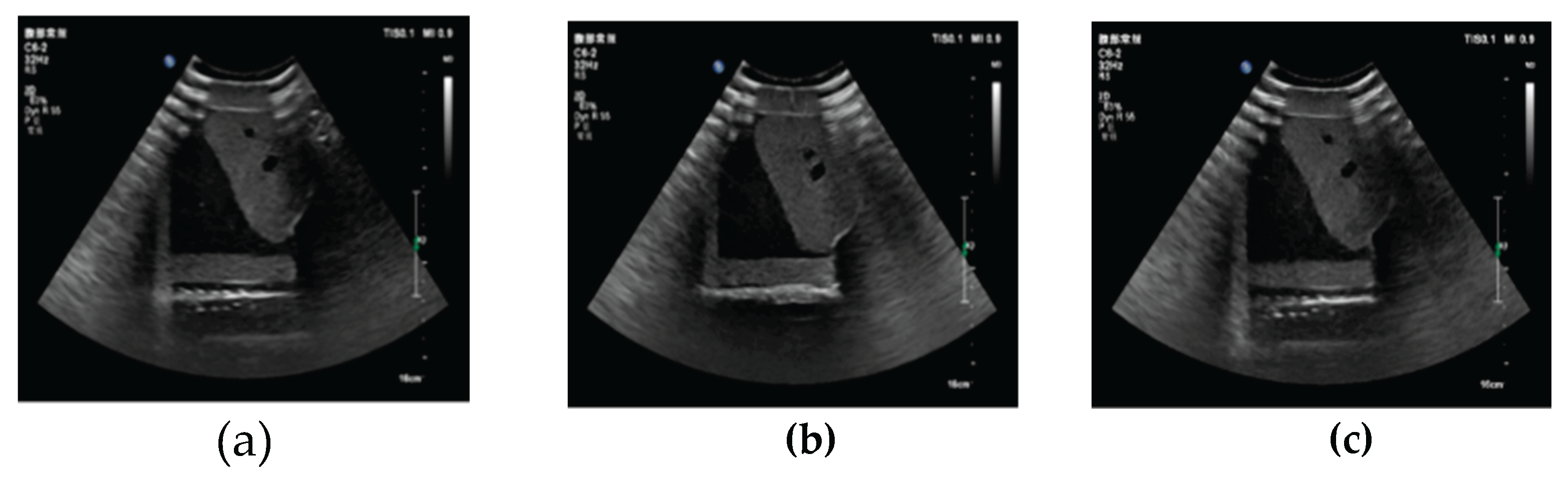

3.1. Three-Dimensional Reconstruction Results of Local Liver Ultrasound

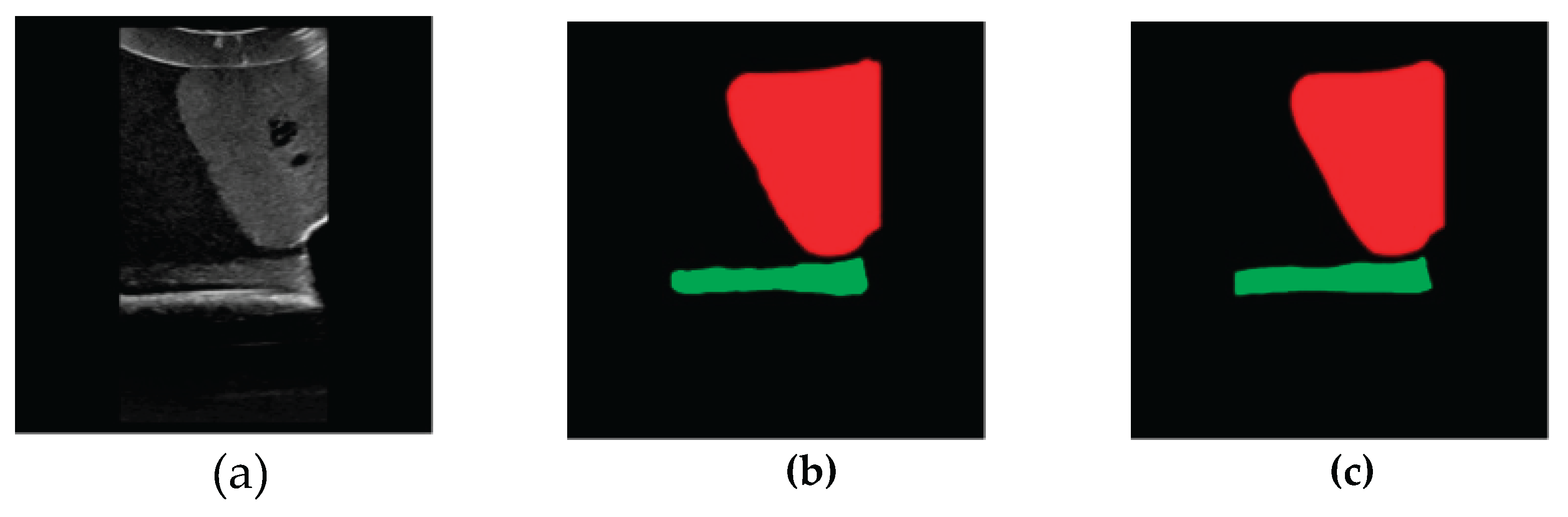

3.2. Image Segmentation and Recognition Results

3.3. Experiment Results of the Reinforcement Learning Agent

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newman, P. G., & Rozycki, G. S. (1998). The history of ultrasound. Surgical clinics of north America, 78(2), 179-195.

- Shung, K. K. (2011). Diagnostic ultrasound: Past, present, and future. J Med Biol Eng, 31(6), 371-4.

- K. J. Schmailzl and O. Ormerod, Ultrasound in Cardiology. Oxford, U.K.: Blackwell Sci., 1994.

- Peeling, W. B., & Griffiths, G. J. (1984). Imaging of the prostate by ultrasound. The Journal of urology, 132(2), 217-224.

- Leinenga, G., Langton, C., Nisbet, R., & Götz, J. (2016). Ultrasound treatment of neurological diseases—current and emerging applications. Nature Reviews Neurology, 12(3), 161-174. [CrossRef]

- P. W. Callen, Ultrasonography in Obstetrics and Gynecology. London,U.K.: Elsevier Health Sci., 2011.

- Baumgartner, C. F., Kamnitsas, K., Matthew, J., Fletcher, T. P., Smith, S., Koch, L. M., ... & Rueckert, D. (2017). SonoNet: real-time detection and localisation of fetal standard scan planes in freehand ultrasound. IEEE transactions on medical imaging, 36(11), 2204-2215. [CrossRef]

- Chang, K. V., Kara, M., Su, D. C. J., Gürçay, E., Kaymak, B., Wu, W. T., & Özçakar, L. (2019). Sonoanatomy of the spine: a comprehensive scanning protocol from cervical to sacral region. Medical ultrasonography, 21(4), 474-482. [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, M. K., & Chin, K. J. (2017). Spinal sonography and applications of ultrasound for central neuraxial blocks. Diunduh dari: http://www. nysora. com/techniques/neuraxialand-perineuraxial-techniques/ultrasoundguided/3276-spinal-and-epidural-block. html, 1.

- Muir, M., Hrynkow, P., Chase, R., Boyce, D., & Mclean, D. (2004). The nature, cause, and extent of occupational musculoskeletal injuries among sonographers: recommendations for treatment and prevention. Journal of Diagnostic Medical Sonography, 20(5), 317-325.

- Berg, W. A., Blume, J. D., Cormack, J. B., & Mendelson, E. B. (2006). Operator dependence of physician-performed whole-breast US: lesion detection and characterization. Radiology, 241(2), 355-365. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G. Z., J. Nelson, B., Murphy, R. R., Choset, H., Christensen, H., H. Collins, S., ... & McNutt, M. (2020). Combating COVID-19—The role of robotics in managing public health and infectious diseases. Science robotics, 5(40), eabb5589.

- Nakadate, R., Solis, J., Takanishi, A., Minagawa, E., Sugawara, M., & Niki, K. (2010, October). Implementation of an automatic scanning and detection algorithm for the carotid artery by an assisted-robotic measurement system. In 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (pp. 313-318). IEEE.

- Nakadate, R., Uda, H., Hirano, H., Solis, J., Takanishi, A., Minagawa, E., ... & Niki, K. (2009, October). Development of assisted-robotic system designed to measure the wave intensity with an ultrasonic diagnostic device. In 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (pp. 510-515). IEEE.

- Mustafa, A. S. B., Ishii, T., Matsunaga, Y., Nakadate, R., Ishii, H., Ogawa, K., ... & Takanishi, A. (2013, December). Development of robotic system for autonomous liver screening using ultrasound scanning device. In 2013 IEEE international conference on robotics and biomimetics (ROBIO) (pp. 804-809). IEEE.

- Mustafa, A. S. B., Ishii, T., Matsunaga, Y., Nakadate, R., Ishii, H., Ogawa, K., ... & Takanishi, A. (2013, July). Human abdomen recognition using camera and force sensor in medical robot system for automatic ultrasound scan. In 2013 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) (pp. 4855-4858). IEEE.

- ROSEN J. Surgical robotics[M]// Medical Devices: Surgical and Image-Guided Technologies. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2013: 63-98.

- Pan, Z., Tian, S., Guo, M., Zhang, J., Yu, N., & Xin, Y. (2017, August). Comparison of medical image 3D reconstruction rendering methods for robot-assisted surgery. In 2017 2nd International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM) (pp. 94-99). IEEE.

- Sung, G. T., & Gill, I. S. (2001). Robotic laparoscopic surgery: a comparison of the da Vinci and Zeus systems. Urology, 58(6), 893-898. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q., Lan, J., & Li, X. (2018). Robotic arm based automatic ultrasound scanning for three-dimensional imaging. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 15(2), 1173-1182. [CrossRef]

- Merouche, S., Allard, L., Montagnon, E., Soulez, G., Bigras, P., & Cloutier, G. (2015). A robotic ultrasound scanner for automatic vessel tracking and three-dimensional reconstruction of b-mode images. IEEE transactions on ultrasonics, ferroelectrics, and frequency control, 63(1), 35-46. [CrossRef]

- Dou, H., Yang, X., Qian, J., Xue, W., Qin, H., Wang, X., ... & Ni, D. (2019, October). Agent with warm start and active termination for plane localization in 3D ultrasound. In International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention (pp. 290-298). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Jarosik, P., & Lewandowski, M. (2019, October). Automatic ultrasound guidance based on deep reinforcement learning. In 2019 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS)(pp. 475-478). IEEE..

- Milletari, F., Birodkar, V., & Sofka, M. (2019). Straight to the point: Reinforcement learning for user guidance in ultrasound. In Smart Ultrasound Imaging and Perinatal, Preterm and Paediatric Image Analysis: First International Workshop, SUSI 2019, and 4th International Workshop, PIPPI 2019, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2019, Shenzhen, China, October 13 and 17, 2019, Proceedings 4 (pp. 3-10). Springer International Publishing.

- Hase, H., Azampour, M. F., Tirindelli, M., Paschali, M., Simson, W., Fatemizadeh, E., & Navab, N. (2020, October). Ultrasound-guided robotic navigation with deep reinforcement learning. In 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (pp. 5534-5541). IEEE.

- Li, K., Wang, J., Xu, Y., Qin, H., Liu, D., Liu, L., & Meng, M. Q. H. (2021, May). Autonomous navigation of an ultrasound probe towards standard scan planes with deep reinforcement learning. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 8302-8308). IEEE.

- Bi, Y., Jiang, Z., Gao, Y., Wendler, T., Karlas, A., & Navab, N. (2022). VesNet-RL: Simulation-based reinforcement learning for real-world US probe navigation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 7(3), 6638-6645. [CrossRef]

- Al Qurri, A., & Almekkawy, M. (2023). Improved UNet with attention for medical image segmentation. Sensors, 23(20), 8589. [CrossRef]

- Jain, G., Kumar, A., & Bhat, S. A. (2024). Recent developments of game theory and reinforcement learning approaches: A systematic review. IEEE Access, 12, 9999-10011. [CrossRef]

- Wen, X., & Li, W. (2023). Time series prediction based on LSTM-attention-LSTM model. IEEE access, 11, 48322-48331. [CrossRef]

- Russell, B. C., Torralba, A., Murphy, K. P., & Freeman, W. T. (2008). LabelMe: a database and web-based tool for image annotation. International journal of computer vision, 77, 157-173. [CrossRef]

| Reward Function | Condition |

|---|---|

| -1 | Out of bounds 1 |

| Outside the alert bounds & | |

| Within the alert bounds & | |

| Outside the alert bounds & | |

| Within the alert bounds & | |

| Outside the alert bounds & | |

| Within the alert bounds & | |

| 5 | |

| 1 |

| First Test | Second Test | Third Test | Average | |

| MSE | 539.5 | 351.0 | 505.6 | 465.37 |

| PSNR | 20.8 dB | 22.7 dB | 21.09dB | 21.53dB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).