1. Introduction

Thromboembolic complications, although rare, remain one of the most relevant adverse events of atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation and are closely linked to endothelial damage [

1,

2]. Traditional energy sources such as radiofrequency (RF) and cryoballoon (CB) ablation can induce a procoagulant response, with elevated tissue plasminogen activator and von Willebrand factor (vWF) levels, predisposing patients to thrombosis and stroke [

3]. Pulsed-field ablation (PFA) is a novel non-thermal technique that creates lesions through irreversible electroporation using ultra-short electrical impulses [

4]. Preclinical and translational studies demonstrated that PFA is highly tissue-selective, effectively ablating cardiac myocytes while largely preserving the endothelium and extracellular matrix [

5,

6]. This endothelial-sparing effect may translate into a lower thromboembolic risk compared with thermal ablation modalities. To date, however, no clinical study has directly compared PFA with CB ablation regarding the extent of endothelial injury. Therefore, this study was designed to address this knowledge gap by assessing biomarkers of endothelial damage after pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) with PFA versus CB.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective observational study included 25 patients with paroxysmal drug-refractory AF in whom the biomarkers were evaluated during the peri-procedural period of the PVI using a pentaspline PFA catheter (Farawave, Farapulse Inc.) or 2nd-generation CB catheter (POLARx, Boston Scientific Inc.). The study was conducted at the Cardiovascular Diseases Department, University Hospital of Split, Croatia. The strategy was decided before the procedure started at the physician’s discretion.

AF was classified as paroxysmal if episodes spontaneously converted to sinus rhythm within seven days or were terminated by electrical or pharmaceutical cardioversion within 48 h [

7]. Exclusion criteria included age under 18, non-paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, prior PVI, additional left atrium substrate modification, severe structural cardiac abnormalities, active thromboembolic processrenal or liver failure, coagulopathy, thrombocytopenia, known malignancy, and recent surgical procedure. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital of Split (Class: 500-03/21-01/100, Number:2181-147/01/06/M.S.-21-01). The study adhered to the ethical guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in a priori approval by the institution’s Ethics Committee.

For each patient, a comprehensive medical history was undertaken. Patients had a physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) recording, and baseline anthropometric measurements. All patients were treated according to current evidence-based medicine and guidelines. Transthoracic echocardiography was done using the Vivid IQ platform (GE HealthCare, Chicago, IL, USA) for every enrolled patient. The same experienced echocardiographer, blinded to the treatment assigned, obtained all echocardiographic measurements according to the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification [

8]. Simpson’s 2D bi-plane approach assessed left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). The left atrial diameter was measured in the parasternal long-axis view.

Fasting blood samples for determination of D-dimer, brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT), and other routine biochemical parameters were taken for all participants one day before and one day after the procedure. All samples were analyzed in the same laboratory by an operator blinded to the subject’s assignment in the study group by good laboratory practice. Von Willebrand antigen (vWF Ag, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) was used to quantify the degree of endothelial damage. Blood samples for vWF Ag were collected from the left atrium at two pre-specified time points during the procedure: before ablation (after heparin administration and transseptal puncture) and after the last PV isolation. Before collecting the sample, the first 10 mL of blood were discarded. The samples were immediately centrifuged, and plasma was aliquoted and stored at -20 °C until analysis. Samples for vWF Ag were analyzed on Atellica COAG 360 System coagulation analyzer (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany). The high-sensitivity cardiac troponin T (hs-cTnT) and N-terminal (1–76) pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) concentrations were determined using the electrochemiluminescence (ECLIA) method using the Eclesys®Cobas e801 Roche Diagnostics (Roche, Manheim, Germany). Standard flow-cytometry-based hematologic analyses (ADVIA 2120i, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) were utilized to ascertain the complete blood count. Standard laboratory methods (Cobasc702, Roche Diagnostics, Manheim, Germany) were used to measure the concentrations of glucose and creatinine in fasting plasma. D-dimer was determined by using standard analyses (BCS, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany).

The ablations were performed under conscious sedation with a bolus of midazolam and fentanyl, followed by a continuous propofol infusion. Unfractionated heparin boluses (150–200 IU/kg each), depending on previous oral anticoagulants, were administered. Activated clotting time (ACT) was monitored at 30-min intervals, followed by additional heparin boluses to maintain an ACT of 350 s. Before ablation, the presence of a left atrial thrombus was excluded by using either pre-procedure transesophageal echocardiography or intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) (AcuNav system, Siemens, Munich, Germany). In the following cases, we used our standard approach to perform PVI with the PFA technique. After a single transseptal puncture, the Farawave ablation catheter was advanced to the ostia of all PVs: left superior PV, left inferior PV, right inferior PV, and right superior PV. ICE imaging and fluoroscopy were used to monitor catheter positioning at the antral level. A train of five consecutive waveforms was delivered for each application, accounting for a total of 2.5 s of ablation time. We used two catheter configurations in each PV ostium: four applications in the ‘flower’ configuration, with the catheter shape fully open, and four applications in the ‘basket’ configuration, with the catheter shape partially closed. The Cryoablation was performed with a single transseptal puncture, and a steerable 15-Fr sheath (POLARSHEATHTM, Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough, MA, USA) was introduced into the left atrium. Then, by moving the balloon catheter over an inner lumen circular mapping catheter, a 28-mm CB (POLARxTM, Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough MA, USA) was advanced toward each PV ostium (POLARMAPTM, Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough MA, USA). Before ablation, PV potentials were recorded at a PV ostium using a mapping catheter (POLARMAPTM, Boston Scientific Corporation, Marlborough, MA, USA). Following balloon inflation, operators repositioned the catheter under fluoroscopic guidance to seal the PV ostium completely. Before ablation, complete PV occlusion was documented using selective contrast injection. If the time to isolation (TTI) was 60 s or less, cryoablation applications lasted 180 s. However, if the TTI exceeded 60 s, a cryoablation application of 240 s was carried out. If no PVI was obtained, additional freeze applications were carried out. Bi-directional PVI in sinus rhythm was confirmed after PV cryoablation at a proximal site in the PV ostium. To detect phrenic nerve palsy during right PVs ablations, right phrenic nerve pacing with a deflectable quadripolar catheter was performed. Skin-to-skin procedure time is defined as the time from the first sheath inserted to the last sheath removed from the patient. In all cases, pericardial effusion was excluded with ICE after the procedure, and the access site was closed with a ‘ modified Figure 8’ suture.

All data analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Mac® (version 25.0, IBM, Ar-monk, NY, USA) and Prism 6 for Mac® (version 6.01, GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range) based on the variable distribution normality or number (N) with percentage (%) within the par-ticular category of interest. The normality of distribution for continuous variables was as-sessed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For differences between groups of interest (PFA vs. CB), an independent samples t-test was used for continuous variables with normal distribution, while the Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables with non-normal distribution. The chi-squared (χ2) test determined differences between groups regarding categorical variables. For the main analysis, circulating levels of vWF were examined in the “before–after” analysis in which the initial values (one day before the ablation procedure) of each patient were pairwise compared to the values obtained after the ablation procedure (one day after the procedure). The mean percent change from before to after the ablation procedure was calculated for each group using the following formula: [(Measurement2 − Measurement1)/Measurement1] × 100, and these values were then compared between both groups of interest by using an independent samples t-test. All results that reached a significance level (p) <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and two-tailed p-values were reported in all instances.

3. Results

Among 25 consecutive patients with paroxysmal AF, 14 patients underwent PFA and 11 underwent cryoablation, respectively. The mean age was 61 ± 10 years, and 56% were female. Arterial hypertension was present in more than half of the patients (52%), while one had diabetes mellitus (4%). The mean LVEF and LA diameter were 64 ± 5% and 42 ± 5 mm, with no difference between the two groups. The median duration of AF since the initially recorded episode was 60 months (IQR 36–126). The baseline, clinical, echocardiographic, and laboratory data did not significantly differ between the two examined groups, as shown in

Table 1.

Furthermore, there was a considerable decrease in the skin-to-skin procedure time and left atrial dwell time in the PFA group compared to the cryoablation group, as shown in

Table 2.

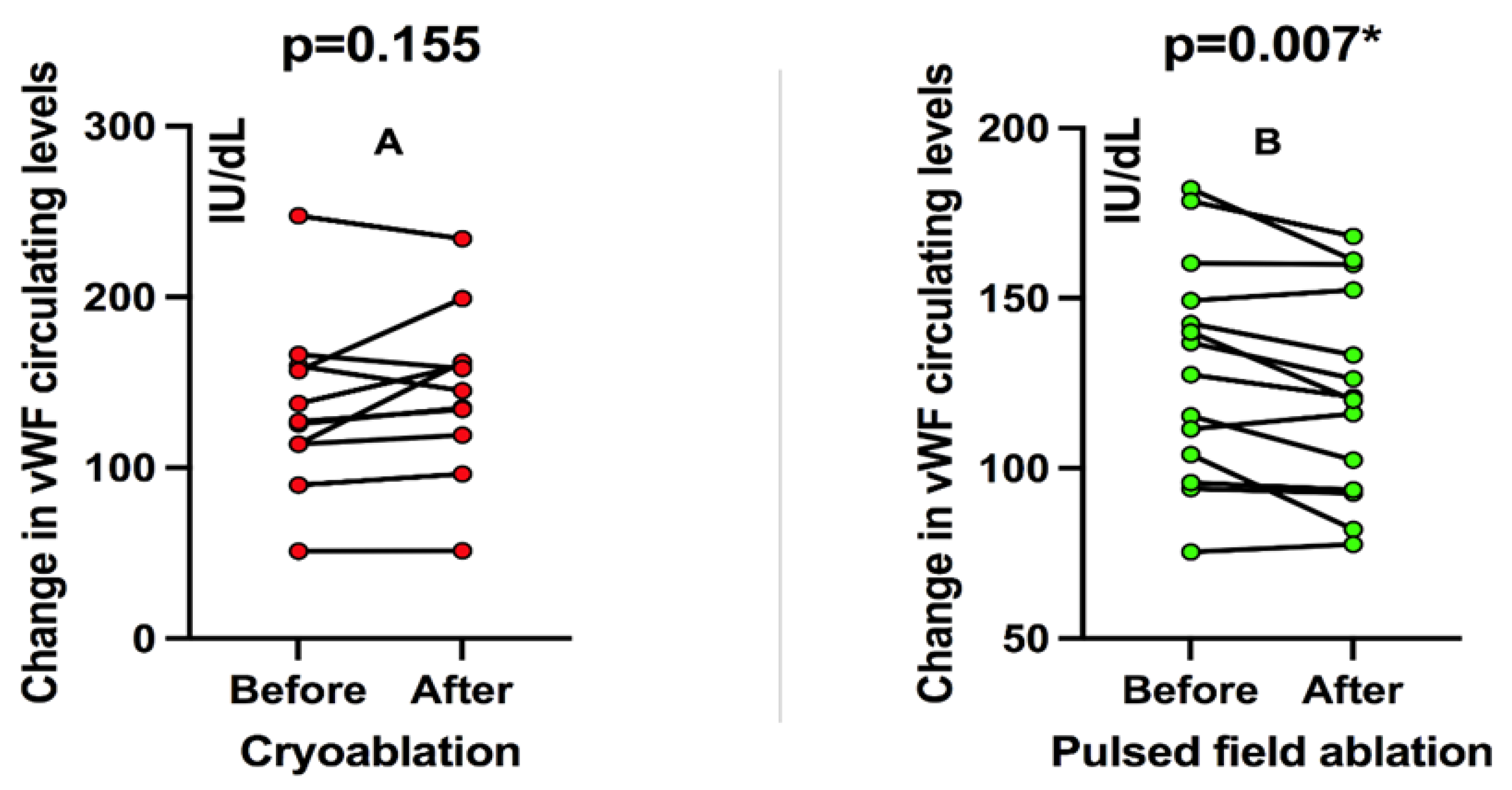

In patients treated with cryoablation, there was no significant change in circulating vWF levels before and after the ablation procedure when patients were analyzed pairwise in a “before-after” fashion (an increase of 9.5%, p = 0.155;

Figure 1A). On the other hand, patients treated with PFA showed a significant decrease in circulating vWF levels compared to before and after ablation (decrease of 7.6%, p = 0.007;

Figure 1B).

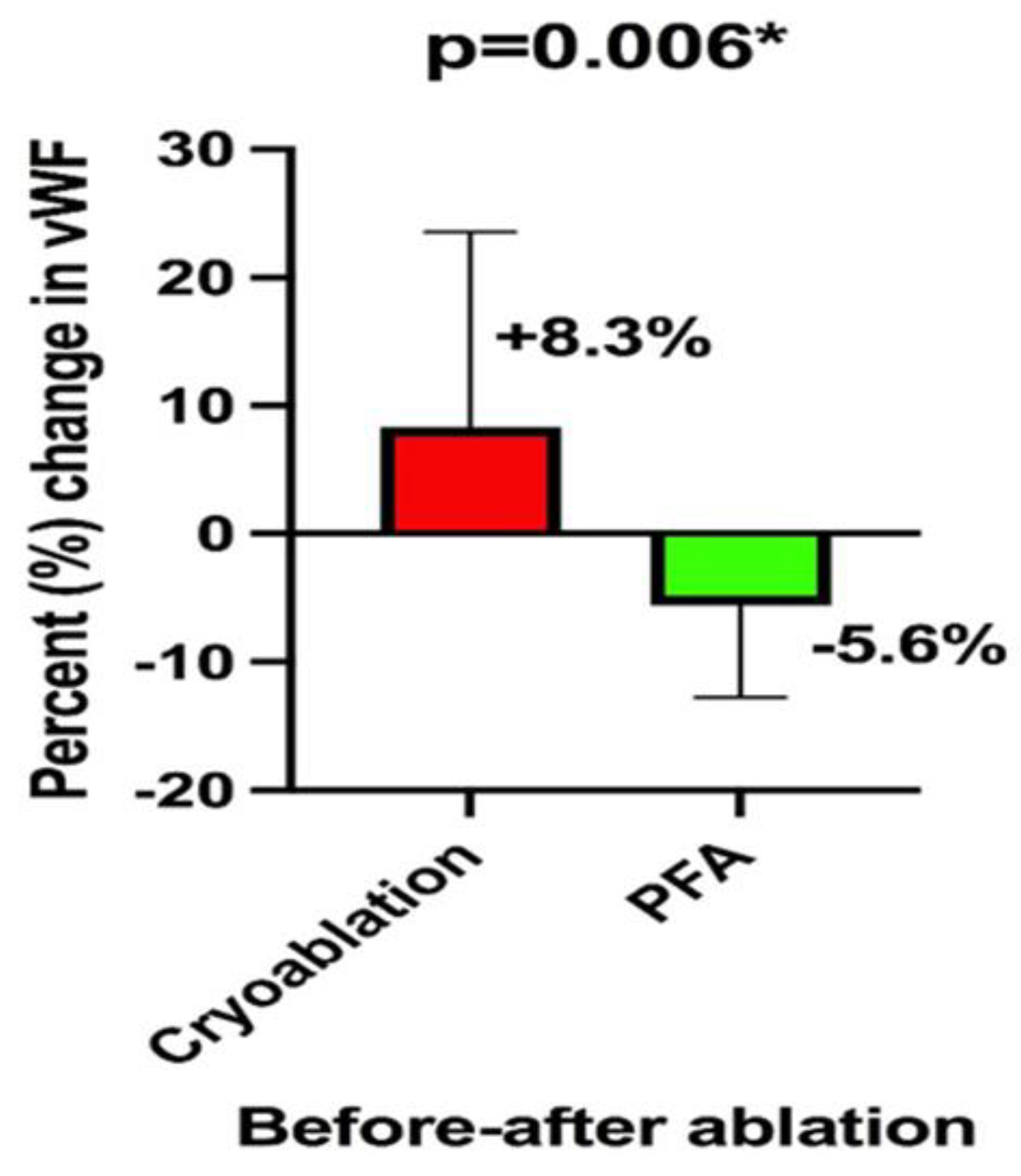

When both groups of interest were analyzed in terms of the mean difference in percent change of circulating vWF before and after the ablation procedure, in a non-pairwise fashion, it could be observed that patients receiving PFA had a decrease of 5.6±7% while patients receiving cryoablation had an 8.3±15% increase in the circulating vWF levels. This difference between the groups was significant (p = 0.006), as shown in

Figure 2.

4. Discussion

In this study, we compare the effects of two ablation catheters for PVI that use different energy sources, the CB ablation and the PFA on endothelial function. The results of our study indicate that PFA may be linked to a reduced extent of endothelial injury when compared to cryoablation, as assessed by measuring the serum levels of vWF.

One potential advantage of the novel approaches to cardiac ablation based on cell electroporation is tissue specificity [

9,

10]. Endothelial cells are susceptible to injury, and anticoagulative properties are lost when endothelial continuity is disrupted. Our findings are consistent with emerging evidence that PFA exerts less endothelial activation compared with thermal ablation modalities. In a recent study by Osmancik et al. PFA produced markedly higher myocardial injury than radiofrequency (RF) ablation, yet levels of platelet activation and coagulation markers, including vWF antigen, fibrin monomers, and D-dimers, were not increased and the inflammatory response was attenuated [

11]. Conversely, recent studies demonstrated that both RF and CB ablation significantly enhanced endothelial injury and coagulation activation [

12,

13]. Importantly, Koruth et al. provided preclinical proof that PFA selectively ablates myocardial tissue while preserving endothelial and vascular structures, thereby reducing the risk of thrombus formation [

14]. In addition to preserving endothelial integrity, PFA appears promising in terms of neurological safety [

15,

16]. However, patients undergoing longer procedures with greater cumulative energy delivery are more likely to experience thromboembolic complications. In our study, PFA significantly reduced both total procedure and left atrial dwell time compared to CB ablation, implying direct benefits for patients and healthcare providers. Taken together with our biomarker findings of endothelial activation, these results suggest that PFA may not only preserve vascular integrity but also lower thromboembolic and cerebral embolic risks through both biological and procedural mechanisms. However, further large-scale and long-term studies are required to definitively confirm these potential safety advantages.

Our research has some limitations worth discussing. First, the number of patients enrolled in the study was limited. Our study’s limitation was that we only examined laboratory biomarkers reflecting endothelial injury, which may only be a surrogate for endothelial damage, and the data only reflect the two types of ablation catheters used in the study. However, this study could not evaluate the efficacy or rate of complications in the two procedures. Because the study group size was small, clinical conclusions are limited; however, there may be differences between patients in the two groups (the small sample sizes may mean that important differences between the groups are missed by type 2 error). We feel that this study provides an important conceptual framework for future research efforts. More extensive studies will be required to compare the clinical outcomes of various ablation methods and energy delivery systems.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, in this prospective study comparing PFA and CB ablation for PVI, we demonstrated that PFA is associated with significantly less endothelial injury, as reflected by a reduction in circulating von Willebrand factor levels, whereas CB ablation induced a pro-coagulant endothelial response. Importantly, PFA markedly shortened left atrial dwell and ablation times, which may further contribute to a reduced thrombogenic risk. Taken together, our results suggest that PFA combines endothelial preservation with procedural efficiency, thereby potentially lowering thromboembolic complications compared with thermal ablation modalities. While these findings reinforce the concept of PFA as an “endothelial-sparing” ablation modality, additional large-scale and long-term studies are needed to confirm the vascular and neurological safety profile of this novel energy source.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., J.B. and Z.J.; methodology, J.K, M.K. and J.A.B.; validation, J.B., T.B. and JA.B.; formal analysis, T.B, A.A and D.S.D.B.K.; investigation, J.K.; re-sources, J.K, Z.J., J.B. and D.S.D; writing—original draft preparation, J.K, M.K. and. JA.B.; writ-ing—review and editing, Z.J., A.A. and J.B.; visualization, JA.B. and B.K; supervision, J.B. and T.B.; project administration, J.K.; funding acquisition, J.B. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because some of the data set will be used for further research.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply grateful to the dedicated teams at both the Department of Ar-rhythmia and Electrophysiology Laboratory and the Department of Medical Laboratory Diag-nostics at the University Hospital of Split. Their unwavering support and invaluable assistance in handling any official matters I faced have been sincerely appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liang, J.J.; Elafros, M.A.; Mullen, M.T.; Muser, D.; Hayashi, T.; Enriquez, A.; Pathak, R.K.; Zado, E.S.; Santangeli, P.; Arkles, J.S.; et al. Anticoagulation use and clinical outcomes after catheter ablation in patients with persistent and longstanding persistent atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2018, 29, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeis S, Gerstenfeld EP, Kalman J, Saad EB, Sepehri Shamloo A, Andrade JG, et al. 2024 European Heart Rhythm Association/Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2024, 26.

- Bulava, A.; Slavík, L.; Fiala, M.; Heinc, P.; Škvařilova, M.; Lukl, J.; Krčová, V.; Indrák, K. Endothelial Damage and Activation of the Hemostatic System During Radiofrequency Catheter Isolation of Pulmonary Veins. Journal of Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology 2004, 10, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, V.Y.; Koruth, J.; Jais, P.; Petru, J.; Timko, F.; Skalsky, I.; Hebeler, R.; Labrousse, L.; Barandon, L.; Kralovec, S.; et al. Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation with Pulsed Electric Fields. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018, 4, 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Driel VJHM, Neven K, van Wessel H, Vink A, Doevendans PAFM, Wittkampf FHM. Low vulnerability of the right phrenic nerve to electroporation ablation. Heart Rhythm. 2015, 12, 1838–1844. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy VY, Dukkipati SR, Neuzil P, Anic A, Petru J, Funasako M, et al. Pulsed Field Ablation of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021, 7, 614–627. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gelder, I.C.; Rienstra, M.; Bunting, K.V.; Casado-Arroyo, R.; Caso, V.; Crijns, H.J.G.M.; De Potter, T.J.R.; Dwight, J.; Guasti, L.; Hanke, T.; et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024, 45, 3314–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for Cardiac Chamber Quantification by Echocardiography in Adults: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015, 16, 233–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaminska, I.; Kotulska, M.; Stecka, A.; Saczko, J.; Drag-Zalesinska, M.; Wysocka, T.; Choromanska, A.; Skolucka, N.; Nowicki, R.; Marczak, J.; et al. Electroporation-induced changes in normal immature rat myoblasts (H9C2). Gen Physiol Biophys. 2012, 31, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maor, E.; Ivorra, A.; Rubinsky, B. Non Thermal Irreversible Electroporation: Novel Technology for Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells Ablation. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osmancik, P.; Bacova, B.; Hozman, M.; Pistkova, J.; Kunstatova, V.; Sochorova, V.; Waldauf, P.; Hassouna, S.; Karch, J.; Vesela, J.; et al. Myocardial Damage, Inflammation, Coagulation, and Platelet Activity During Catheter Ablation Using Radiofrequency and Pulsed-Field Energy. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2024, 10, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieragnoli, P.; Gori, A.M.; Ricciardi, G.; Carrassa, G.; Checchi, L.; Michelucci, A.; Priora, R.; Cellai, A.P.; Marcucci, R.; Padeletti, L.; et al. Effects of cryoablation and radiofrequency ablation on endothelial and blood clotting activation. Intern Emerg Med. 2014, 9, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malmborg, H.; Christersson, C.; Lönnerholm, S.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C. Comparison of effects on coagulation and inflammatory markers using a duty-cycled bipolar and unipolar radiofrequency pulmonary vein ablation catheter vs. a cryoballoon catheter for pulmonary vein isolation. EP Europace 2013, 15, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koruth, J.S.; Kuroki, K.; Iwasawa, J.; Viswanathan, R.; Brose, R.; Buck, E.D.; Donskoy, E.; Dukkipati, S.R.; Reddy, V.Y. Endocardial ventricular pulsed field ablation: a proof-of-concept preclinical evaluation. EP Europace 2020, 22, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochstadt, A.; Barbhaiya, C.R.; Jankelson, L.; Levine, J. Pulsed field ablation and periprocedural stroke risk—A step in the right direction. Heart Rhythm. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Gómez, J.M.; Ortiz-Fernández, Á.; Soler-Martínez, J.; Gabaldón-Pérez, A.; Iraola-Viana, D.; Martínez-Brotons, Á.; Bondanza-Saavedra, L.; Domínguez-Mafé, E.; Redondo-Nieto, L.; Picazo-Campos, P.; et al. Incidence of brain lesions following pulsed field ablation for atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).