1. Introduction

Chronic lung diseases (CLDs) in children encompass a spectrum of conditions that lead to structural lung abnormalities and impaired pulmonary function that, in some cases, lead to severe respiratory symptoms [

1]. Cystic Fibrosis (CF), non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis (NCFB), and Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia (PCD) are commonly grouped under the term chronic suppurative lung diseases (CSLDs), a clinical phenotype characterized by chronic endobronchial infection, ongoing inflammation, and mucopurulent airway secretions [

2].

Cystic fibrosis affects approximately 1 in 2,500 live births in European populations [

3], while NCFB presents with highly variable prevalence depending on diagnostic criteria, ranging from 0.2 to 735 per 100,000 children [

4]. PCD, a rare congenital disorder of motile cilia, is estimated to occur in 1 in 20,000 individuals, although underdiagnosis is frequent due to clinical heterogeneity [

5].

Persistent airway inflammation, ventilation-perfusion mismatch, and recurrent infections can impair cardiopulmonary efficiency, induce respiratory and peripheral muscle weakness, reduce daily physical activity levels, and negatively affect growth and nutritional status [

6,

7]. As a result, children with CLDs frequently demonstrate diminished exercise capacity, reduced muscle strength, and intermittently decreased participation in physical activities, all of which contribute to a lower health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [

8].

Structured exercise training has emerged as a core therapeutic component in the management of chronic pediatric respiratory diseases. It has been shown to improve aerobic capacity, reduce dyspnea, enhance muscle strength, and promote better HRQoL [

9,

10]. In cystic fibrosis and other CSLDs, exercise interventions are associated with slower disease progression, improved pulmonary function, and decreased hospitalization rates [

11].

Physiotherapists play a pivotal role in this process by conducting detailed assessments of functional and exercise capacity, providing crucial information for the design and progression of individualized rehabilitation programs . The European Respiratory Society emphasises that rehabilitation for non-asthmatic children, such as those with bronchiectasis, should be delivered by trained physiotherapists with pediatric expertise, and should include components such as airway clearance, strength training, aerobic exercise, and breathing strategies [

12].

Although cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is considered the gold standard for evaluating exercise tolerance, field exercise tests, such as the six-minute walk test (6MWT), modified shuttle walk test (mSWT), and step tests, have been widely adopted as practical alternatives in the clinical setting [

13].

These field-based exercise tests require minimal equipment, provide valid and reproducible estimates of functional capacity, and are generally well tolerated by children with moderate-to-severe chronic lung diseases, including cystic fibrosis [

14,

15].

Despite the increasing recognition of field tests in pediatric respiratory care, the literature lacks clarity regarding validity and reliability for assessing functional capacity in children with CLDs other than asthma.

Therefore, this scoping review aims to systematically map the existing field-based exercise tests used to assess functional capacity in children with chronic lung diseases other than asthma.

2. Method

2.1. Overview

This scoping review was structured following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

16]. The methods were developed on the basis of the methodological framework for scoping review recommended by Arksey and O’Malley [

17] as well as by Levac et al. [

18].

2.2. Research Questions

The research questions were as follows: “Which field tests are used to assess functional capacity in children with CLDs other than asthma?” and “Are those field tests valid and reliable?”.

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria were original publications that (a) included children (aged 6-12 years) with CLDs except asthma, (b) investigated the use of field tests for assessing the functional capacity of the targeted group, (c) studies in the English language. Children with (a) asthma (b) cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, neurological diseases or cancer as a comorbidity, or (c) athletes, were excluded. Abstracts, book reviews, book chapters, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, scoping reviews, grey literature, case series/reports, commentaries, letters to the editor, editorials, clinical practice guidelines, and protocols were also excluded.

2.4. Search Strategy

A systematic literature search (

Appendix A) was performed from inception to May 20, 2025, using 3 electronic databases: PubMed, Medline (via EBSCOhost) and Web of Science, using a combination of subject headings and keywords. The search strategy was designed using keywords and MESH terms related to Lung Diseases, Obstructive, Exercise Test and Pediatrics. The concepts and key index terms used were adapted to the selected databases, and the keywords were combined using Boolean logical operators (AND and OR). Citations of the included articles and relevant systematic reviews were used for a hand-held search of additional eligible studies for inclusion.

2.5. Screening and Article Selection

All retrieved articles were imported into Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute) Web app, and duplicates were removed manually (

https://www.rayyan.ai). Two researchers (PD and AM) independently screened all titles, abstracts, and full texts for inclusion. In case of discrepancies at any stage of the study selection, a third researcher (EK) was consulted to make the final decision.

2.6. Data Extraction and Verification

Two researchers (PD and AM) extracted all the data from the included articles. A template was developed to guide data extraction, including the author and year of publication, study design, field test, diagnosis, study population and sample size, purpose, and reported outcomes. All extracted data were synthesized and collated in a descriptive table summary.

2.7. Quality Assessment

To assess the methodological quality of the included studies, we employed the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, developed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), a part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [

19]. This tool is specifically designed for use in studies that include non-randomized observational studies, such as cohort and cross-sectional designs.

The tool comprises 14 items that evaluate critical aspects of study design and conduct, including: clarity of the research question and study objectives, definition and representativeness of the study population, sample size justification, adequacy of participation rate, reliability and validity of exposure and outcome measures, temporal relationship between exposure and outcome, appropriateness of statistical analyses, and consideration of potential confounding variables.

Each item was assessed as “Yes”, “No”, “Cannot Determine”, “Not Reported”, or “Not Applicable”. Based on the number and nature of the criteria met, an overall quality rating was assigned to each study as Good, Fair, or Poor, following the guidance provided by the NHLBI.

Two reviewers (PD and VS) independently performed the quality assessments. Any discrepancies in scoring or overall ratings were resolved through discussion and consensus. When disagreement persisted, a third reviewer (EK) was consulted to reach a final decision. The results of the quality assessment were used to inform the interpretation of the findings and the strength of the evidence presented in this review.

2.8. Data Synthesis and Analysis

A narrative synthesis was conducted for relevant outcomes and methodological characteristics of all included studies. The results and discussion sections of all the included articles were presented to identify the field test used to assess the functional capacity of children with CLDs.

3. Results

3.1. Flow of Studies

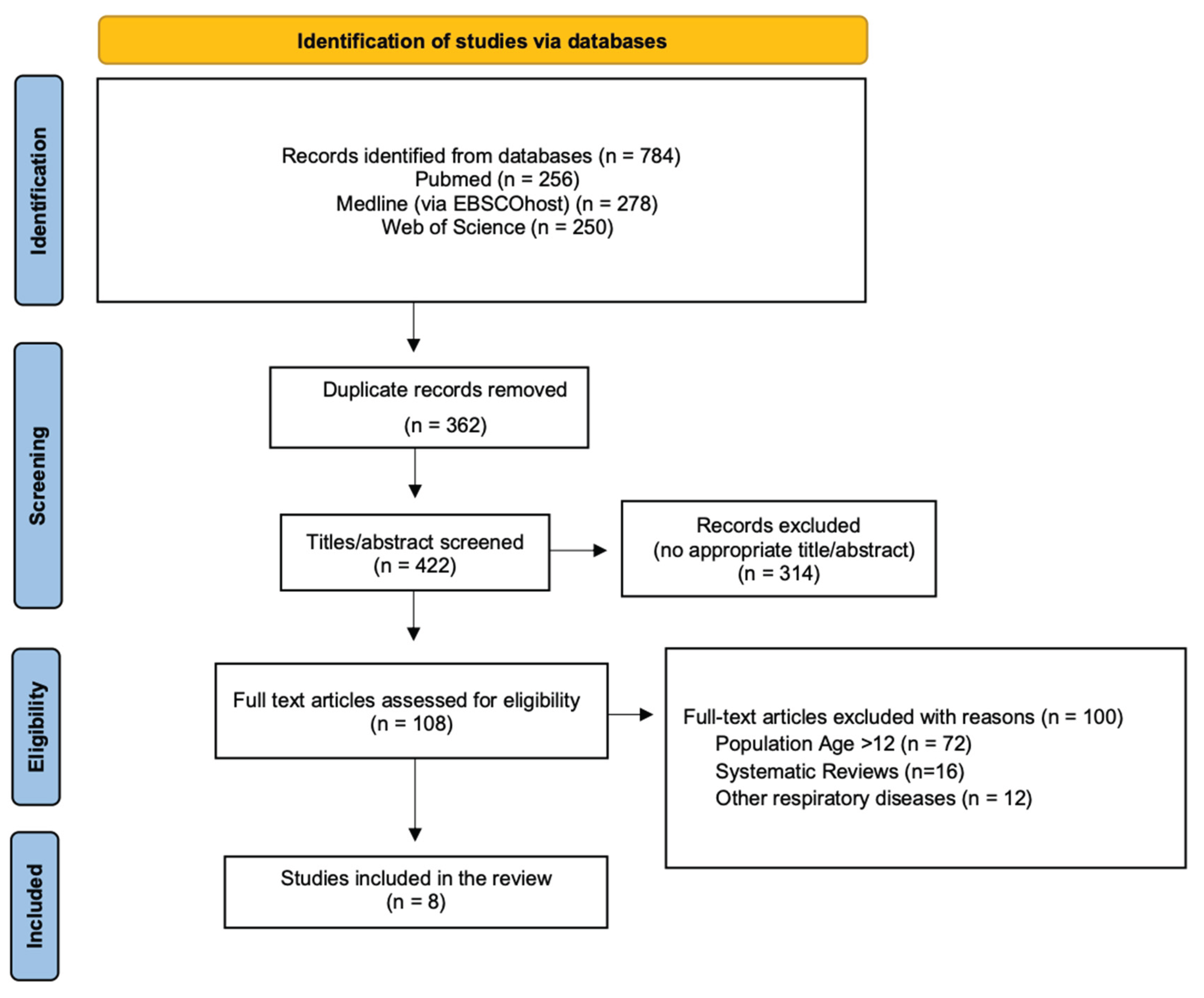

The initial search from the 3 electronic databases yielded a total of 784 publications. After the removal of the duplicate articles and the titles and abstracts screening, a total of 8 articles were collected and assessed for eligibility. The PRISMA flowchart in

Figure 1 shows the literature review strategy and the reasons for article exclusion.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

The characteristics of the included studies (n = 8) are presented in

Table 1. They were published between 2019 and 2025 and employed diverse methodological designs, including cross-sectional (n=5), repeated measures (n=1), prospective longitudinal (n = 1), and multicenter observational (n=1) approaches. The primary aims of the studies varied: some focused on establishing test-retest reliability (n=3), minimal detectable changes (n=2), cardiorespiratory responses (n=5), or associations with physiological parameters such as respiratory muscle strength (n=2), and lung function (n=3).

Seven out of eight studies investigated children with CF, and one study included participants with PCD. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 132 participants, with reported age ranges between 7 and 11 years.

3.3. Field Tests Used

Five different field tests employed in the assessment of functional capacity in children with CLDs: the 6MWT, mSWT, three-minute step test (3mST), one-minute sit-to-stand test (1mSTS), and the TGlittre-Pediatric test (TGlittre-P). The 6MWT emerged as the most utilized test, featured in three studies [

20,

22,

25] (CF: n=2, PCD: n=1). The mSWT, used in two studies [

24,

26], involving children with CF. Each of the 3mST [

25], TGlittre-P test [

23] and 1mSTS [

30] was used in a single study featuring children with CF.

3.4. Reported Outcomes of the Field Tests

The main outcome measure during the walking tests was the distance covered (in meters). During the 3mST, all participants completed the test at the prescribed cadence of 30 steps per minute without early termination. Children with CF demonstrated a higher mean rating of perceived exertion at test completion compared to HC, despite achieving a comparable step count and no significant differences in heart rate or oxygen saturation recovery profiles [

21]. Performance in the 1mSTS was quantified by the total number of repetitions completed. Additionally, repetitions were normalized by body mass (kg), and total work (TW) was estimated by multiplying the repetitions by body mass [

27]. For the TGlittre-P test, the main performance indicator was the total time required to complete the test [

23]. Cardiorespiratory responses were common outcome measures across all field tests [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. They included heart rate (HR), respiratory rate (RR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate variation (VHR = HRpeak − HRbaseline). The rating of perceived exertion and sensation of dyspnea was assessed using the Borg scale. Peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO₂%) was monitored at baseline, throughout, and upon completion of each test.

Among the eight studies, only one incorporated a structured assessment of cardiopulmonary recovery following test completion. Silva et al. (2021), utilising the 3-minute step test, measured recovery indices including the Borg dyspnea and fatigue, SBP after the test and up to five minutes of recovery.

3.5. Test-Retest Reliability

The test-retest reliability has been examined only in children diagnosed with CF. One of the three studies that employed the 6MWT demonstrated high test-retest reliability for the distance covered (6MWD), with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) ranging from 0.708 to 0.948 (mean ICC: 0.874), indicating strong reproducibility. Moreover, physiological and subjective outcomes—including heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation (SpO₂), fatigue, and dyspnea—were consistently reported, further supporting the test’s responsiveness and construct validity. Similarly, for the mSWT, one study reported high reproducibility (ICC ≥ 0.80) across three timepoints. The TGlittre-P test also demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability, with an ICC of 0.849, supporting its consistency in measuring functional performance over time.

3.6. Methodological Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included observational studies was assessed using the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies developed by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) [

19]. This tool evaluates 14 criteria that encompass internal validity elements such as clear research objectives, defined populations, sample size justification, timing of exposure and outcome assessments, adequacy of follow-up, and adjustment for confounding. Each study was rated as “Good”, “Fair”, or “Poor” quality based on the collective strength of its design and reporting.

Table 2.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.

Table 2.

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies.

| No. |

Villanueva et al.

(2019) |

Silva et al.

(2021) |

Innocenti et al. (2021) |

Scalco et al.

(2021) |

Leite et al.

(2021) |

Firat et al.

(2022) |

Mucha et al.

(2023) |

Santos Costa et al. (2025) |

| 1. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 2. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 3. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 4. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 5. |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

| 6. |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| 7. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 8. |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| 9. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 10. |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

N/A |

| 11. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 12. |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

N/R |

| 13. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| 14. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Rate |

Fair |

Fair |

Good |

Fair |

Good |

Fair |

Fair |

Fair |

4. Discussion

This scoping review provides a comprehensive synthesis of field tests employed to assess functional capacity in CLDs other than asthma, with a predominant focus on CF and limited representation of PCD. While field tests have long been integral to adult pulmonary rehabilitation—particularly in populations with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—their application in pediatric populations remains underdeveloped [

28].

Among the tests identified, the 6MWT emerged as the most frequently used and well-supported field test. Its widespread adoption is likely due to its simplicity, minimal equipment requirements, and strong correlation with clinically meaningful outcomes such as forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV₁), aerobic capacity (VO₂peak), and physical activity levels in children with CF [

29]. Its reproducibility and responsiveness to clinical changes support its utility in the clinical setting. Preceding studies in children with moderate-to-severe asthma showed that the 6MWD is significantly lower compared to healthy reference values. This diminished functional capacity likely reflects a combination of ventilatory limitation, deconditioning, and exercise-induced dynamic hyperinflation, all of which may contribute to the impaired heart rate recovery we observed among children with other CLDs such as CF [

30].

The mSWT addresses an incremental format that approximates maximal effort and correlates more strongly with VO₂peak than the 6MWT in pediatric populations [

31]. Studies included in this review demonstrated good test–retest reliability, responsiveness, and the ability to distinguish between healthy peers and pediatric patients for both functional tests [

24,

26]. These findings align with those of del Corral et al. [

32], who reported excellent test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.975) for the mSWT in children and adolescents aged 7-15 years with CF. This comparison highlights both the robustness of mSWT in CF and the need for similar estimates across other pediatric CLDs and specific age groups. Beyond test reliability, the mSWT has also provided valuable insights into autonomic impairment, as previous studies in asthmatic children aged 9–11 years, demonstrated significantly reduced heart rate recovery (69 ± 12 bpm) compared to healthy peers (79 ± 15 bpm) at the end of the test, supporting the presence of autonomic nervous system dysregulation in this population [

33].

Emerging tools such as the 1mSTS and the TGlittre-P test offer additional dimensions of assessment. The 1mSTS is increasingly recognized for its relationship with lower-limb muscle strength, lung function, and CPET outcomes in children with CF [

34]. Furthermore, the test offers a multidimensional assessment of functional status by simulating activities of daily living as it captures endurance, strength, balance, and coordination in a single tool. Evidence from pediatric CF cohorts supports its reliability and clinical applicability particularly in highlighting limitations that may not be evident on more aerobic-focused tests such as the 6MWT [

35].

The 3mST, although less extensively studied, has emerged as a feasible and reproducible tool for evaluating submaximal exercise capacity in children with CF, both in face-to-face and remote assessment [

36]. Notably, the test provides insights into the perceived exertion of dyspnea and fatigue as an indicator of reduced exercise tolerance, despite central cardiac responses (HR) might be comparable to healthy controls.

Beyond objective indices, the sensation of breathlessness, as captured via ratings of RPE during functional tests, is measurable and clinically informative in children with chronic disease. In cystic fibrosis, Borg dyspnea scores obtained immediately after the 6MWT correlate with 6MWD and cardiorespiratory strain, supporting RPE as a valid symptom-limited marker of capacity [

37]. Consistent with this, pediatric cardiology guidance explicitly integrates Borg dyspnea/fatigue ratings into 6MWT procedures for congenital heart disease, underscoring their relevance to recovery profiling [

38].

Beyond their role in functional assessment, field tests may also serve as sensitive markers of clinical stability and predictors of adverse outcomes in pediatric chronic lung diseases. Exercise tolerance, as measured by the 6MWT, is associated with a higher risk of hospitalization and earlier lung function decline [

39].

Moreover, incorporating symptom perception measures, such as the Borg dyspnea and fatigue scales, enhances the value of field tests, capturing aspects of exercise intolerance that are not reflected by physiological indices alone [

40]. These insights highlight that field-based assessments should not be viewed merely as substitutes for cardiopulmonary exercise testing, but rather as multidimensional tools that integrate physiological, functional, and patient-reported outcomes in clinical care.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this scoping review is its comprehensive approach, systematically synthesizing evidence from pediatric (6-12 years old) chronic lung disease populations, other than asthma, while including a variety of functional field tests, such as walking, stepping, and multi-task tests, allowing comparisons across tests and conditions, highlighting gaps in the literature. Importantly, by focusing on non-asthma CLDs, this review addresses an underrepresented yet clinically important pediatric subgroup.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. The heterogeneity of included studies in terms of disease diagnosis and testing protocols limits direct assumptions. For example, the 3mST and the 1mSTS lack test-retest reliability in this specific age group. In addition, most available evidence originates from cystic fibrosis studies, with sparse data for rarer conditions such as NCFB.

Future Recommendations

Future perspectives could aim to use the standardized protocols for field tests in pediatric CLDs other than asthma populations, enabling cross-study comparisons and reference values across tests. Multicenter studies, particularly in NCFB are needed to validate the psychometric properties and clinical responsiveness of field tests. The integration of symptom-based measures, such as sensation of dyspnea and ratings of perceived exertion, alongside physiological outcomes, could provide a more complete picture of functional limitations and patient experience. Finally, longitudinal studies assessing the prognostic value of these field tests for clinical outcomes, including exacerbations, hospitalization risk, and quality of life, would strengthen the evidence base for their routine use in pediatric respiratory care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D., E.A.K.; methodology, P.D., A.M., V.S. and E.A.K.; validation, K.D., and E.A.K.; formal analysis, P.D., D.M.; data curation, P.D., K.D., E.A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.D., E.A.K, A.M., V.S., and D.M.; writing—review and editing, P.D., E.A.K, A.M., V.S., D.M. and K.D.; visualization, P.D. and E.A.K.; supervision, K.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 1mSTS |

One-Minute Sit-To-Stand Test |

| 3mST |

Three-Minute Step Test |

| 6MWD |

Distance covered during 6MWT |

| 6MWT |

Six-Minute Walk Test |

| CLDs |

Chronic Lung Diseases |

| COPD |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| CPET |

Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing |

| CSLDs |

Chronic Suppurative Lung Diseases |

| CF |

Cystic Fibrosis |

| DBP |

Diastolic Blood Pressure |

| FEV₁ |

Forced Expiratory Volume in One Second |

| HC |

Healthy Controls |

| HR |

Heart Rate |

| HRQoL |

Health-Related Quality of Life |

| ICC |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficients |

| MDC |

Minimal Detectable Changes |

| mSWT |

Modified Shuttle Walk Test |

| NCFB |

Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis |

| PCD |

Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia |

| RPE |

Rating of Perceived Exertion |

| RR |

Respiratory Rate |

| SBP |

Systolic Blood Pressure |

| TGlittre-P |

TGlittre-Pediatric test |

| VHR |

Variation of Heart Rate

|

Appendix A

| Category |

Search Terms |

| Lung Diseases, Obstructive |

cystic fibrosis, non-cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, primary ciliary dyskinesia |

| Exercise Test |

functional test, field test, step test, exercise test, treadmill test, 6-minute walk test, 6MWT, chester step test, CST, 3-minute step test, 3MST, incremental shuttle walk test, ISWT, modified shuttle walk test, MSWT, 2-minute walk test, 2MWT, timed-up and go, TUG, 1-minute sit-to-stand test, 1mSTST, 30-second sit-to-stand test, 30secSTS, endurance shuttle walk test, ESWT, 20 meter shuttle run, beep test |

| Pediatrics |

child* |

| P - Patient, Population, or Problem |

What are the most important characteristics of the patient? How would you describe a group of patients similar to yours? |

Children (0-12 years) with Cystic Fibrosis, non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis, and Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia |

| I - Intervention, Exposure, Prognostic Factor |

What main intervention, prognostic factor, or exposure are you considering? What do you want to do for the patient (prescribe a drug, order a test, etc.)? |

Field tests are performed for the assessment of functional capacity and exercise tolerance, such as the 6-minute walk test, the incremental shuttle walk test, the 3-minute step test, etc. |

| C - Comparison |

What is the main alternative to compare with the intervention? |

- |

| O - Outcome |

What do you hope to accomplish, measure, improve, or affect? |

As outcomes, we aim to investigate functional capacity, exercise capacity, and exercise tolerance |

| T - Time Factor |

|

We consider any intervention time period |

| S – Study design |

|

|

References

- Bush, A.; Fleming, L. Diagnosing and managing pediatric chronic lung diseases. Lancet Respir. Med. 2019, 7, 682–693. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, A.B.; Bush, A.; Grimwood, K. Bronchiectasis in children: diagnosis and treatment. Horton, R., Ed.; Elsevier: London, UK, 2018; 10150, pp. 866–879. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.C.; et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 65–124. [Google Scholar]

- McCallum, G.B.; Binks, M.J. The epidemiology of chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis in children and adolescents. Front. Pediatr. 2017, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J.S.; et al. Diagnosis and management of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2014, 15, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, I.S.; Vilarinho, R.; Amaral, L. Influence of history of bronchiolitis on health-related physical fitness (muscle strength and cardiorespiratory fitness) in children and adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Muscles 2025, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelbasset, W.K.; Soliman, G.S.; Elshehawy, A.A.; Alrawaili, S.M. Exercise capacity and muscle fatiguability alterations following a progressive maximal exercise of lower extremities in children with cystic fibrosis. Afr. Health Sci. 2018, 18, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggio, A.B.; Hofer, M.F.; Martin, X.E.; Marchand, L.M.; Beghetti, M.; Farpour-Lambert, N.J. Reduced physical activity level and cardiorespiratory fitness in children with chronic diseases. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2010, 169, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joschtel, B.; Gomersall, S.R.; Tweedy, S.; Petsky, H.; Chang, A.B.; Trost, S.G. Effects of exercise training on physical and psychosocial health in children with chronic respiratory disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2018, 4, e000409. [Google Scholar]

- Klijn, P.H.; Oudshoorn, A.; van der Ent, C.K.; van der Net, J.; Kimpen, J.L.; Helders, P.J. Effects of anaerobic training in children with cystic fibrosis: a randomized controlled study. Chest 2004, 125, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneiderman, J.E.; Wilkes, D.L.; Atenafu, E.G.; et al. Longitudinal relationship between physical activity and lung health in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 43, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A.B.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for pediatric bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 58, 2002990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P.F.; Chan, E.Y.T.; Ng, D.K.K.; Kwok, K.L.; Yip, A.Y.F.; Leung, S.Y. Correlation between 6-min walk test and cardiopulmonary exercise test in Chinese patients. Pediatr. Respirol. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 2, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.L.; Stockton, K.; Wilson, C.; Russell, T.G.; Johnston, L.M. Exercise testing for children with cystic fibrosis: A systematic review. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2020, 55, 1996–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riner, W.F.; Sellhorst, S.H. Physical activity and exercise in children with chronic health conditions. J. Sport Health Sci. 2013, 2, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; et al. A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- López-de-Uralde-Villanueva, I.; Sarría Visa, T.; Moscardó Marichalar, P.; del Corral, T. Minimal detectable change in six-minute walk test in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2019, 43, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.P.; Araujo, E.V.; Machado, I.P.; et al. Rating of perceived exertion in three-minute step test in children with cystic fibrosis. Int. J. Exerc. Sci. 2021, 14, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ιnnocenti, D.; Masi, E.; Taccetti, G.; et al. Six minute walk test in Italian children with cystic fibrosis aged 6 and 11. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2021, 92, 2047. [Google Scholar]

- Scalco, J.C.; Martins, R.; Almeida, A.C.S.; Caputo, F.; Schivinski, C.I.S. Test–retest reliability and minimal detectable change in TGlittre-P test in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Disabil. Rehabil. 2021, 44, 3701–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, L.R.; Queiroz, K.C.V.; da Silva, F.H.; Coelho, C.C.; Donadio, M.V.F.; Aquino, E.D.S. Clinical use of the modified shuttle test in children with cystic fibrosis: Is one test sufficient? Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firat, M.; Bosnak-Guclu, M.; Sismanlar-Eyuboglu, T.; Tana-Aslan, A. Respiratory muscle strength, exercise capacity and physical activity in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia: a cross-sectional study. Respir. Med. 2022, 191, 106719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, F.C.; Gonçalves Wamosy, R.M.; Scalco, J.C.; et al. Comparison of the modified shuttle walk test in children with cystic fibrosis and healthy controls. Physiother. Res. Int. 2024, 29, e2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, B.S.; Fischer, D.L.; de Lima, F.Á.L.; da Costa, M.S.; Vendrusculo, F.M.; Donadio, M.V.F. The 1-minute sit-to-stand test in children with cystic fibrosis: cardiorespiratory responses and correlations with aerobic fitness, nutritional status, pulmonary function, and quadriceps strength. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2025, Online ahead of print. [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; et al. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 44, 1428–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade Lima, C.; Dornelas de Andrade, A.; Campos, S.L.; Brandão, D.C.; Mourato, I.P.; Britto, M.C.A. Six-minute walk test as a determinant of the functional capacity of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: A systematic review. Respir. Med. 2018, 137, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade LB, Silva DA, Salgado TL, Figueroa JN, Lucena-Silva N, Britto MC. Comparison of six-minute walk test in children with moderate/severe asthma with reference values for healthy children. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2014, 90, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, J.; Howard, J.; Wallace, E.; Elborn, J.S. Validity of a modified shuttle test in adult cystic fibrosis. Thorax 1999, 54, 437–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Corral T, Gómez Sánchez Á, López-de-Uralde-Villanueva I. Test-retest reliability, minimal detectable change and minimal clinically important differences in modified shuttle walk test in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2020, 19, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, É.P. Soares, B.A., Reimberg, M.M. et al. Heart rate recovery in asthmatic children and adolescents after clinical field test. BMC Pulm Med. 2021.

- Kilic, K.; Vardar-Yagli, N.; Ademhan-Tural, D.; et al. The effects of telerehabilitation versus home-based exercise on muscle function, physical activity, and sleep in children with cystic fibrosis: A randomized controlled trial. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2025, 45, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, H.; Cani, K.; Araújo, J.; Mayer, A. Reliability and validity of the Glittre-ADL test to assess the functional status of patients with interstitial lung disease. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2021, 18, 14799731211012962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vendrusculo, F.M.; da Costa, G.A.; Bagatini, M.A.; et al. Feasibility of performing the 3-minute step test with remote supervision in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis: A comparative study. Pediatr. Investig. 2024, 8, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha MT, Rozov T, de Oliveira RC, Jardim JR. Six-minute walk test in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2006, 41, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah SS, Mohanty S, Karande T, Maheshwari S, Kulkarni S, Saxena A. Guidelines for physical activity in children with heart disease. Ann Pediatr Cardiol. 2022, 15, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schneiderman, J.E.; Wilkes, D.L.; Atenafu, E.G.; et al. Longitudinal relationship between physical activity and lung health in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2014, 43, 817–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.S.; Mohanty, S.; Karande, T.; et al. Guidelines for physical activity in children with heart disease. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2022, 15, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).