Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 05C15, 68R10, 68W20

1. Introduction

- design and implement a randomized algorithm that is based on analogy to the Ising model in statistical mechanics;

- we test the performance on random graphs and on a subset of DIMACS that is a standard library of benchmark instances for graph coloring;

- we show that the algorithm designed is not only able to provide near optimal (or, even optimal) solutions, but it is also very robust in the sense that it is not very sensitive to the choice of parameter(s);

2. The Graph Coloring Problem and the Basic Algorithm

2.1. Graph Coloring Problems

2.2. The Algorithm of Petford and Welsh for k-Coloring Decision Problem

| Algorithm 1 Petford-Welsh algorithm for k-coloring |

|

2.3. The Algorithm of Petford and Welsh and Generalized Boltzmann Machine

- the generalized Boltzmann machine indeed generalizes the standard model and that probability of state converges toas the number of steps tends to infinity ( is a normalizing constant).

- the update rule of the model corresponds to the Petford Welsh algorithm when the problem considered is graph coloring.

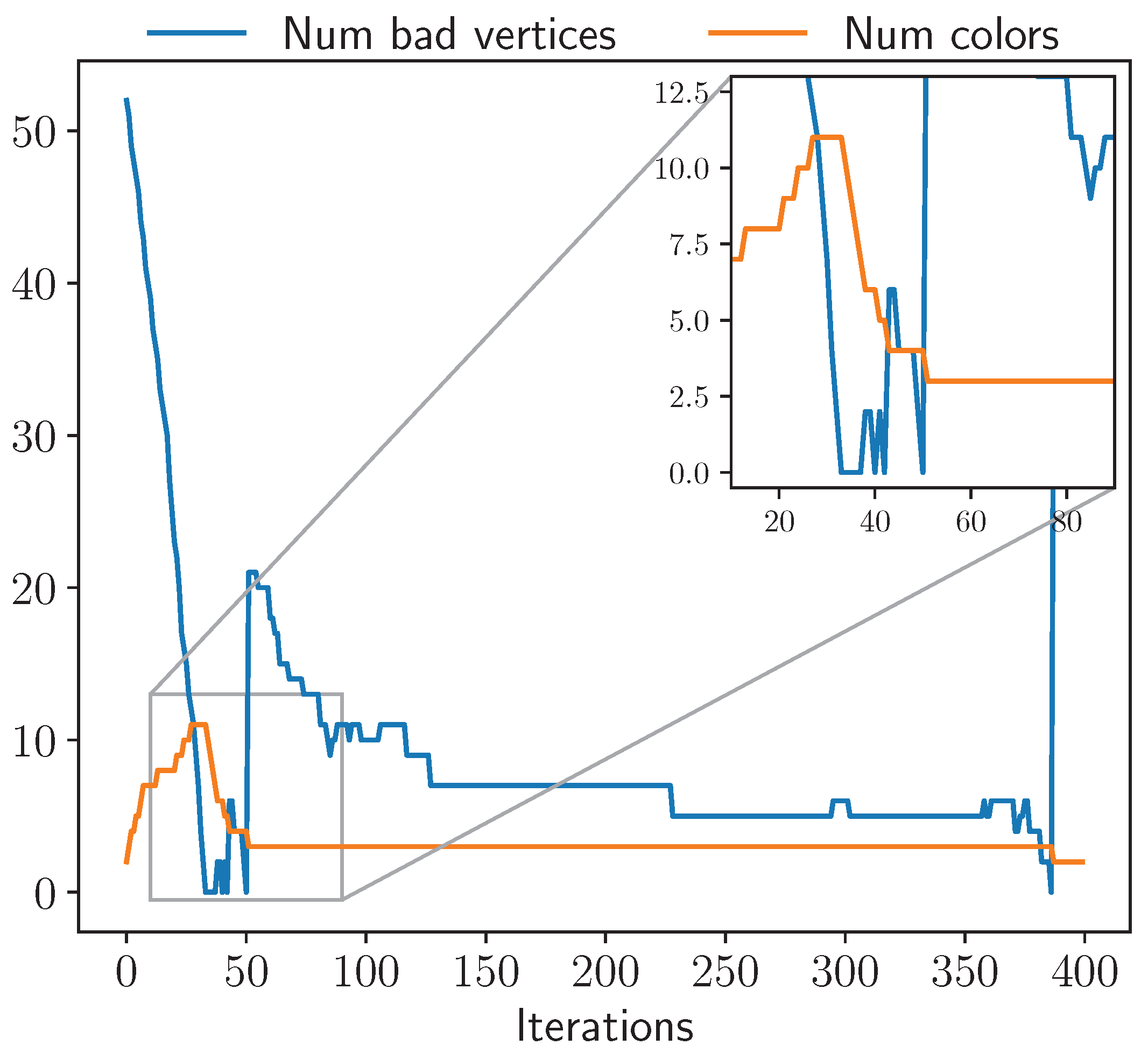

3. The New DYNAMIC Algorithm for Estimating

| Algorithm 2 Dynamic k-Coloring Algorithm |

|

| Algorithm 3 Procedure: ChooseColor |

|

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets

4.1.1. Random k-Colorable Graphs

- N is the total number of vertices,

- k is the number of partitions,

- P is the edge probability between vertices in different partitions, expressed as a percentage (e.g., means probability ),

- i is the instance number.

4.1.2. DIMACS Graphs

4.1.3. Some More Info on Experiments

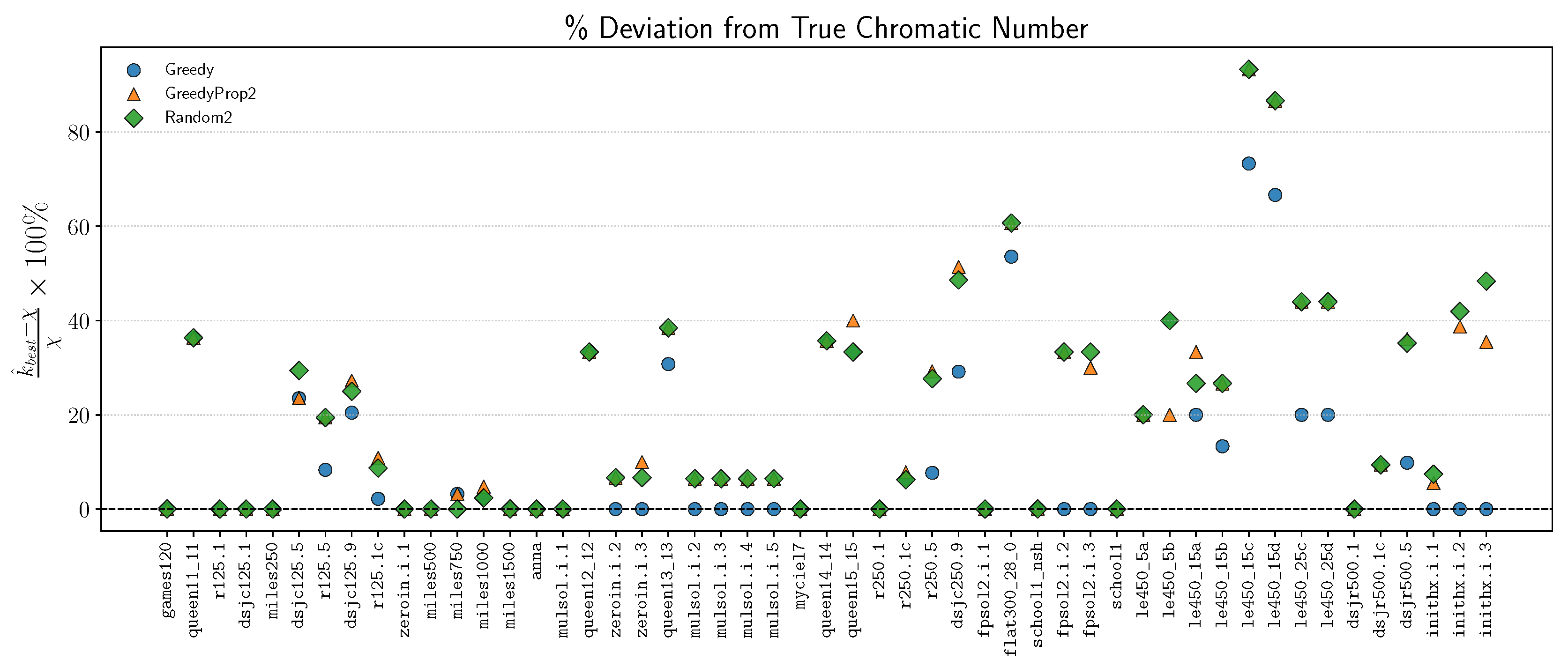

- Random2: Coloring the vertices randomly with 2 colors.

- Greedy: Coloring the graph with greedy algorithm which colors the “largest first” strategy, i.e., nodes are colored in descending order of degree. Note that this method always yields a proper coloring.

- GreedyProp2: A local propagation-based coloring method that starts from a random node and greedily colors neighbors using the least frequent color in their neighborhood. Uses 2 colors and aims to minimize conflicts.

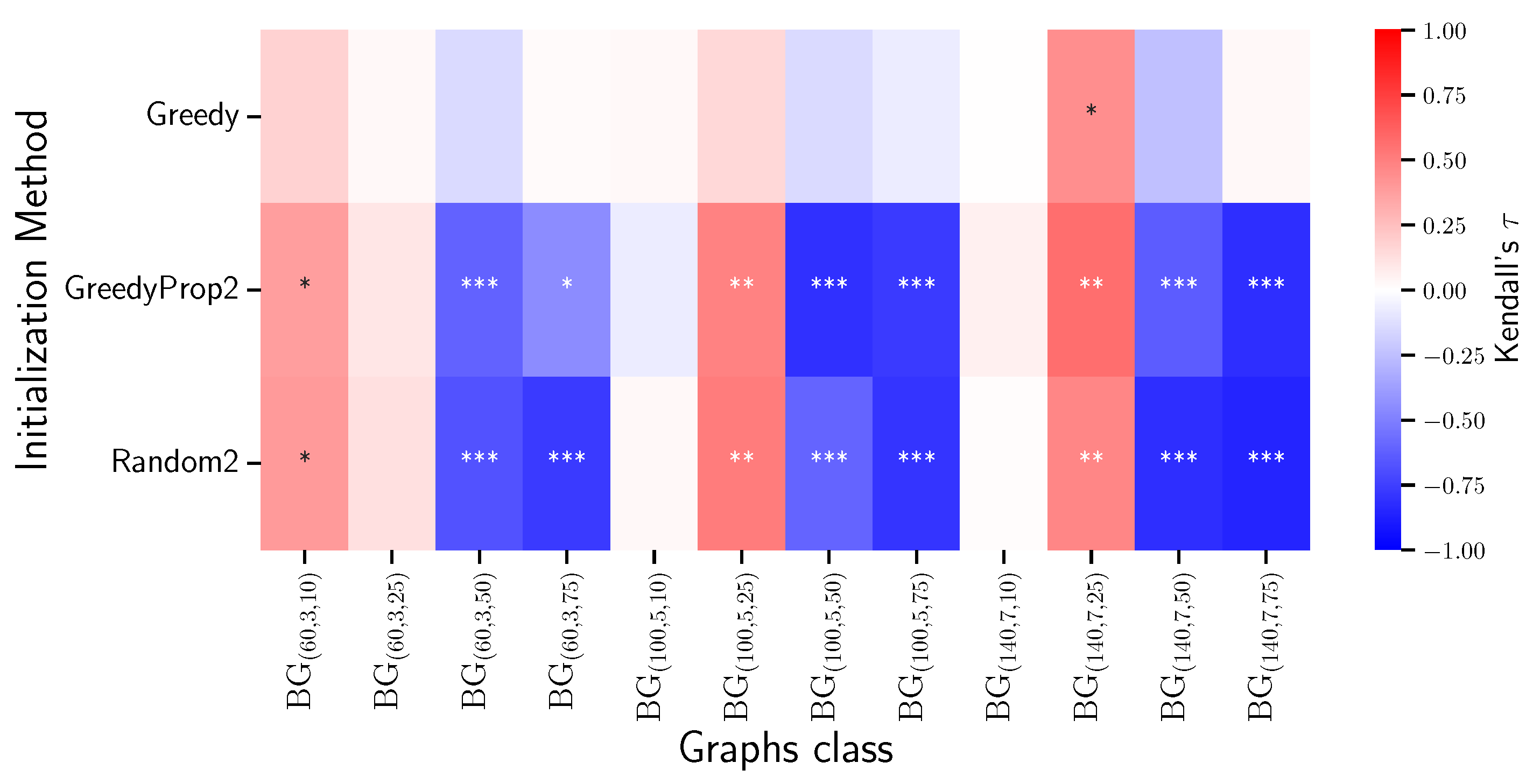

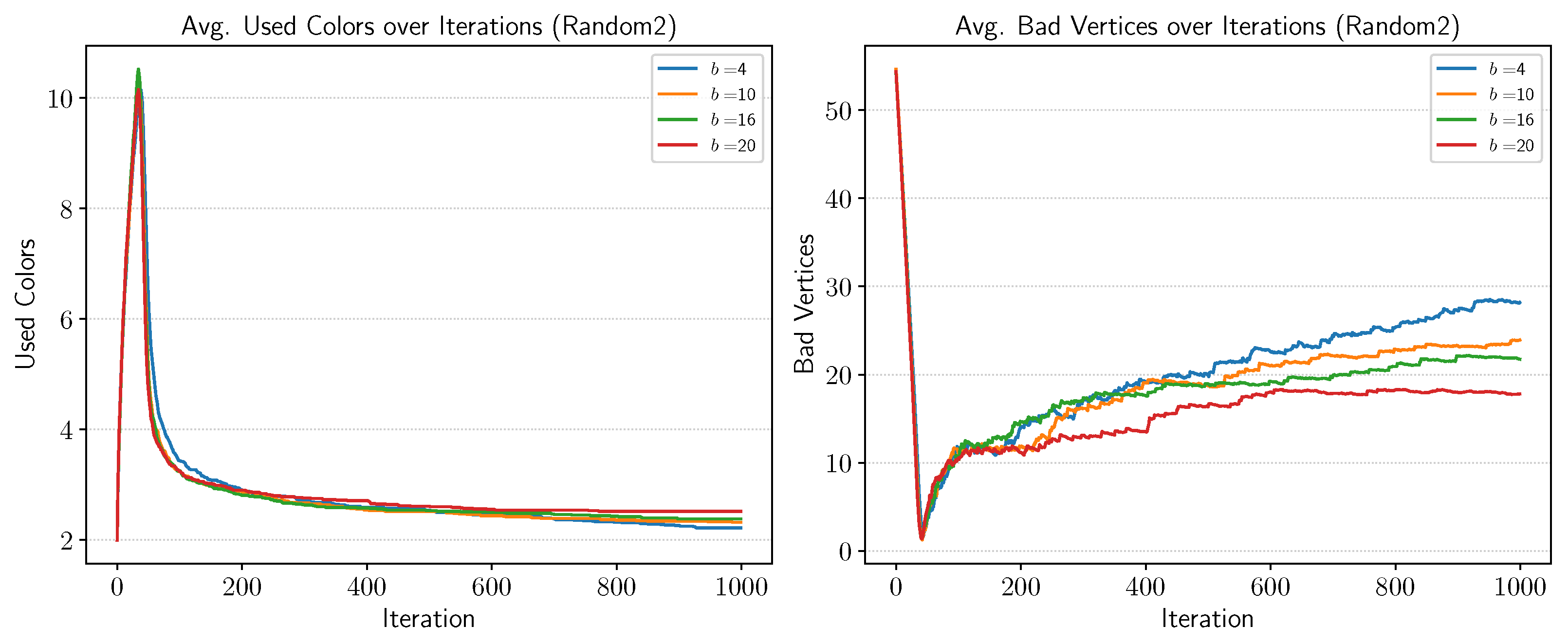

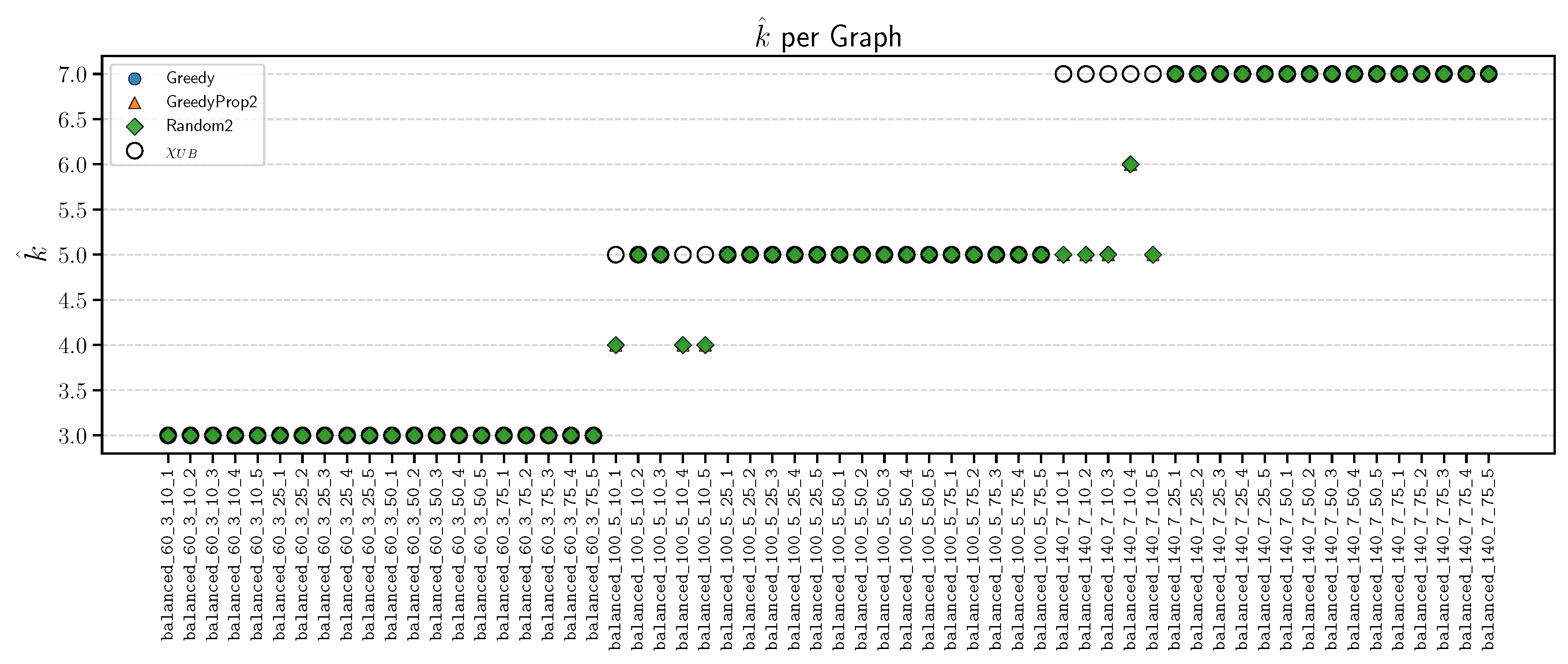

4.2. Experiment on Colorable Random Graphs

- A positive indicates that as b increases, the number of iterations tends to increase (i.e., slower convergence).

- A negative implies that higher base values are associated with fewer iterations (i.e., faster convergence).

4.3. Experiments on DIMACS Graphs

5. Conclusions

- Investigate more principled strategies for base selection and initialization to improve reliability and convergence speed.

- Explore parallel or distributed implementations to enhance scalability on large graph instances.

- Benchmark the approach against recent heuristic solvers, including those based on deep learning and quantum optimization.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karp, R. Reducibility among combinatorial problems. In: Complexity of Computer Computations. R. Miller and J. Thatcher, Eds. Plenum Press 1972, pp. 85–103.

- Appel, K.; Haken, W. Solution of the Four Color Map Problem. Scientific American 1977, 237, 108–121. [CrossRef]

- de Werra, D. Restricted coloring models for timetabling. Discrete Mathematics 1997, 165-166, 161–170. Graphs and Combinatorics, . [CrossRef]

- King, A.D.; Nocera, A.; Rams, M.M.; Dziarmaga, J.; Wiersema, R.; Bernoudy, W.; Raymond, J.; Kaushal, N.; Heinsdorf, N.; Harris, R.; et al. Beyond-classical computation in quantum simulation. Science 2025, 388, 199–204. [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, N.; McMahon, P.L.; Byrnes, T. Ising machines as hardware solvers of combinatorial optimization problems, 2022, [arXiv:quant-ph/2204.00276]. To appear in Nature Reviews Physics.

- Lee, H.; Jeong, K.C.; Kim, P. Quantum Circuit Optimization by Graph Coloring, 2025, [arXiv:quant-ph/2501.14447].

- D’Hondt, E. Quantum approaches to graph colouring. Theoretical Computer Science 2009, 410, 302–309. Computational Paradigms from Nature, . [CrossRef]

- Tabi, Z.; El-Safty, K.H.; Kallus, Z.; Haga, P.; Kozsik, T.; Glos, A.; Zimboras, Z. Quantum Optimization for the Graph Coloring Problem with Space-Efficient Embedding. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Quantum Computing and Engineering (QCE), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, 2020; pp. 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Ardelean, S.; Udrescu, M. Graph coloring using the reduced quantum genetic algorithm. PeerJ Computer Science 2022, [8:e836].

- Shimizu, K.; Mori, R. Exponential-Time Quantum Algorithms for Graph Coloring Problems. Algorithmica 2022, p. 3603–3621.

- Asavanant, W.; Charoensombutamon, B.; Yokoyama, S.; Ebihara, T.; Nakamura, T.; Alexander, R.N.; Endo, M.; Yoshikawa, J.i.; Menicucci, N.C.; Yonezawa, H.; et al. Time-Domain-Multiplexed Measurement-Based Quantum Operations with 25-MHz Clock Frequency. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2021, 16, 034005. [CrossRef]

- Arrazola, J.M.; Delgado, A.; Bardhan, B.R.; Lloyd, S. Quantum-inspired algorithms in practice. Quantum 2020, 4, 307. [CrossRef]

- Chakhmakhchyan, L.; Cerf, N.J.; Garcia-Patron, R. Quantum-inspired algorithm for estimating the permanent of positive semidefinite matrices. Physical Review A 2017, 96. [CrossRef]

- da Silva Coelho, W.; Henriet, L.; Henry, L.P. Quantum pricing-based column-generation framework for hard combinatorial problems. Physical Review A 2023, 107. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.M.R. A Guide to Graph Colouring; Springer Nature Switzerland, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Petford, A.; Welsh, D. A Randomised 3-coloring Algorithm. Discrete Mathematics 1989, 74, 253–261.

- Donnelly, P.; Welsh, D. The antivoter problem: Random 2-colourings of graphs. In Graph Theory and Combinatorics (Cambridge, 1983), Academic Press, London. 1984, pp. 133–144.

- Žerovnik, J. A Randomized Algorithm for k–colorability. Discrete Mathematics 1994, 131, 379–393.

- Ubeda, S.; Žerovnik, J. A randomized algorithm for a channel assignment problem. Speedup 1997, 11, 14–19.

- Ikica, B.; Gabrovšek, B.; Povh, J.; Žerovnik, J. Clustering as a dual problem to colouring. Computational and Applied Mathematics 2022, 41, 147.

- Žerovnik, J. A randomised heuristical algorithm for estimating the chromatic number of a graph. Information Processing Letters 1989, 33, 213–219. [CrossRef]

- Shawe-Taylor, J.; Žerovnik, J. Boltzmann machine with finite alphabet, 1992. RHBNC Departmental Technical Report CSD-TR-92-29, extended abstract appears in Artificial Neural Networks 2, vol 1, 391-394.

- Ackley, D.H.; Hinton, G.E.; Sejnowski, T.J. A learning algorithm for boltzmann machines. Cognitive science 1985, 9, 147–169.

- Lundy, M.; Mees, A. Convergence of an annealing algorithm. Mathematical Programming 1986, 34, 111–124. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.S.; Trick, M.A., Eds. Cliques, Coloring, and Satisfiability: Second DIMACS Implementation Challenge, Vol. 26, DIMACS Series in Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science. American Mathematical Society, 1996. Proceedings of the Second DIMACS Implementation Challenge held October 11–13, 1993.

- Marappan, R.; Bhaskaran, S. New evolutionary operators in coloring DIMACS challenge benchmark graphs. International Journal of Information Technology 2022, 14, 3039–3046. Published August 19, 2022; Received April 25, 2022; Accepted July 28, 2022, . [CrossRef]

- Kole, A.; Pal, A. Efficient Hybridization of Quantum Annealing and Ant Colony Optimization for Coloring DIMACS Graph Instances. J Heuristics 2025, 31, 29. [CrossRef]

- https://mat.tepper.cmu.edu/COLOR/instances.html. Accessed: 2025-08-14.

- https://cedric.cnam.fr/~porumbed/graphs/. Accessed: 2025-08-14.

- https://sites.google.com/site/graphcoloring/links. Accessed: 2025-08-14.

- https://github.com/omkarbihani/Dynamic_Petford_Welsh.

- Gabrovšek, B.; Žerovnik, J. A fresh look to a randomized massively parallel graph coloring algorithm. Croatian Operational Research Review 2024, 15, 105–117.

| Graph | N | (, mean iters.) | ||||

| Greedy | GreedyProp2 | RandomProp2 | ||||

| balanced_60_3_10_1 | 60 | 141 | 3 | (3, 100, 642.68) | (3, 100, 1302.94) | (3, 99, 1821.76) |

| balanced_60_3_10_2 | 60 | 113 | 3 | (3, 100, 106.49) | (3, 100, 465.34) | (3, 100, 569.14) |

| balanced_60_3_10_3 | 60 | 133 | 3 | (3, 74, 10190.38) | (3, 93, 7186.72) | (3, 94, 6029.05) |

| balanced_60_3_10_4 | 60 | 130 | 3 | (3, 100, 1530.08) | (3, 100, 1029.23) | (3, 100, 1176.21) |

| balanced_60_3_10_5 | 60 | 118 | 3 | (3, 100, 459.19) | (3, 100, 541.94) | (3, 100, 977.8) |

| balanced_60_3_25_1 | 60 | 286 | 3 | (3, 100, 138.41) | (3, 100, 244.05) | (3, 100, 310.88) |

| balanced_60_3_25_2 | 60 | 294 | 3 | (3, 100, 75.15) | (3, 100, 313.53) | (3, 100, 375.84) |

| balanced_60_3_25_3 | 60 | 307 | 3 | (3, 100, 780.74) | (3, 100, 253.35) | (3, 100, 347.57) |

| balanced_60_3_25_4 | 60 | 290 | 3 | (3, 100, 42.57) | (3, 100, 312.86) | (3, 100, 343.8) |

| balanced_60_3_25_5 | 60 | 305 | 3 | (3, 100, 416.05) | (3, 100, 380.13) | (3, 100, 366.63) |

| balanced_60_3_50_1 | 60 | 617 | 3 | (3, 100, 0.0) | (3, 100, 134.96) | (3, 100, 167.42) |

| balanced_60_3_50_2 | 60 | 620 | 3 | (3, 100, 12.45) | (3, 100, 139.09) | (3, 100, 161.89) |

| balanced_60_3_50_3 | 60 | 615 | 3 | (3, 100, 0.0) | (3, 100, 139.67) | (3, 100, 167.31) |

| balanced_60_3_50_4 | 60 | 607 | 3 | (3, 100, 101.06) | (3, 100, 140.56) | (3, 100, 155.89) |

| balanced_60_3_50_5 | 60 | 585 | 3 | (3, 100, 13.14) | (3, 100, 151.34) | (3, 100, 162.3) |

| balanced_60_3_75_1 | 60 | 922 | 3 | (3, 100, 18.46) | (3, 100, 123.56) | (3, 100, 144.42) |

| balanced_60_3_75_2 | 60 | 887 | 3 | (3, 100, 0.0) | (3, 100, 132.12) | (3, 100, 141.11) |

| balanced_60_3_75_3 | 60 | 873 | 3 | (3, 100, 0.0) | (3, 100, 127.72) | (3, 100, 148.82) |

| balanced_60_3_75_4 | 60 | 895 | 3 | (3, 100, 0.0) | (3, 100, 122.42) | (3, 100, 145.22) |

| balanced_60_3_75_5 | 60 | 886 | 3 | (3, 100, 0.0) | (3, 100, 125.22) | (3, 100, 145.73) |

| balanced_100_5_10_1 | 100 | 401 | 5 | (4, 87, 13128.01) | (4, 86, 16060.19) | (4, 81, 16753.02) |

| balanced_100_5_10_2 | 100 | 415 | 5 | (5, 100, 20.55) | (5, 100, 240.4) | (5, 100, 264.25) |

| balanced_100_5_10_3 | 100 | 437 | 5 | (5, 100, 55.58) | (5, 100, 306.05) | (5, 100, 321.21) |

| balanced_100_5_10_4 | 100 | 394 | 5 | (4, 78, 11475.01) | (4, 51, 20058.78) | (4, 55, 21395.64) |

| balanced_100_5_10_5 | 100 | 365 | 5 | (4, 100, 2782.52) | (4, 100, 4984.56) | (4, 100, 5133.19) |

| balanced_100_5_25_1 | 100 | 997 | 5 | (5, 100, 983.59) | (5, 100, 1649.32) | (5, 100, 1906.21) |

| balanced_100_5_25_2 | 100 | 955 | 5 | (5, 100, 5284.42) | (5, 100, 2634.18) | (5, 100, 2838.9) |

| balanced_100_5_25_3 | 100 | 1007 | 5 | (5, 100, 564.73) | (5, 100, 2511.9) | (5, 100, 2338.59) |

| balanced_100_5_25_4 | 100 | 1026 | 5 | (5, 100, 1221.94) | (5, 100, 1570.72) | (5, 100, 1549.94) |

| balanced_100_5_25_5 | 100 | 1047 | 5 | (5, 100, 2068.82) | (5, 100, 1785.53) | (5, 100, 1672.43) |

| balanced_100_5_50_1 | 100 | 2032 | 5 | (5, 100, 286.49) | (5, 100, 358.45) | (5, 100, 360.32) |

| balanced_100_5_50_2 | 100 | 2021 | 5 | (5, 100, 103.01) | (5, 100, 357.99) | (5, 100, 364.16) |

| balanced_100_5_50_3 | 100 | 2005 | 5 | (5, 100, 196.63) | (5, 100, 368.24) | (5, 100, 367.94) |

| balanced_100_5_50_4 | 100 | 2014 | 5 | (5, 100, 154.58) | (5, 100, 351.25) | (5, 100, 380.66) |

| balanced_100_5_50_5 | 100 | 2086 | 5 | (5, 100, 139.04) | (5, 100, 356.6) | (5, 100, 357.76) |

| balanced_100_5_75_1 | 100 | 2993 | 5 | (5, 100, 179.48) | (5, 100, 284.43) | (5, 100, 277.5) |

| balanced_100_5_75_2 | 100 | 2990 | 5 | (5, 100, 88.3) | (5, 100, 278.52) | (5, 100, 286.92) |

| balanced_100_5_75_3 | 100 | 3004 | 5 | (5, 100, 44.88) | (5, 100, 270.54) | (5, 100, 288.61) |

| balanced_100_5_75_4 | 100 | 2994 | 5 | (5, 100, 0.0) | (5, 100, 273.09) | (5, 100, 270.02) |

| balanced_100_5_75_5 | 100 | 3042 | 5 | (5, 100, 0.0) | (5, 100, 269.09) | (5, 100, 273.38) |

| balanced_140_7_10_1 | 140 | 826 | 7 | (5, 95, 18607.58) | (5, 94, 25152.38) | (5, 93, 24742.58) |

| balanced_140_7_10_2 | 140 | 837 | 7 | (5, 66, 34506.83) | (5, 67, 33209.18) | (5, 53, 27958.49) |

| balanced_140_7_10_3 | 140 | 836 | 7 | (5, 89, 25239.54) | (5, 83, 24031.25) | (5, 89, 29304.94) |

| balanced_140_7_10_4 | 140 | 880 | 7 | (6, 100, 411.99) | (6, 100, 706.27) | (6, 100, 732.43) |

| balanced_140_7_10_5 | 140 | 866 | 7 | (5, 21, 41444.86) | (5, 20, 34369.45) | (5, 27, 34863.89) |

| balanced_140_7_25_1 | 140 | 2079 | 7 | (7, 100, 8915.54) | (7, 100, 11801.03) | (7, 100, 10159.86) |

| balanced_140_7_25_2 | 140 | 2101 | 7 | (7, 100, 6355.96) | (7, 100, 10853.21) | (7, 100, 10400.25) |

| balanced_140_7_25_3 | 140 | 2099 | 7 | (7, 100, 8596.3) | (7, 100, 8723.64) | (7, 100, 8021.37) |

| balanced_140_7_25_4 | 140 | 2073 | 7 | (7, 100, 16328.22) | (7, 100, 11899.88) | (7, 100, 11190.06) |

| balanced_140_7_25_5 | 140 | 2081 | 7 | (7, 100, 11418.61) | (7, 99, 15249.36) | (7, 98, 15336.41) |

| balanced_140_7_50_1 | 140 | 4151 | 7 | (7, 100, 262.65) | (7, 100, 690.69) | (7, 100, 690.55) |

| balanced_140_7_50_2 | 140 | 4210 | 7 | (7, 100, 370.72) | (7, 100, 661.65) | (7, 100, 679.32) |

| balanced_140_7_50_3 | 140 | 4263 | 7 | (7, 100, 492.75) | (7, 100, 637.24) | (7, 100, 675.79) |

| balanced_140_7_50_4 | 140 | 4125 | 7 | (7, 100, 467.31) | (7, 100, 694.28) | (7, 100, 691.0) |

| balanced_140_7_50_5 | 140 | 4157 | 7 | (7, 100, 495.34) | (7, 100, 677.32) | (7, 100, 680.06) |

| balanced_140_7_75_1 | 140 | 6320 | 7 | (7, 100, 60.02) | (7, 100, 433.22) | (7, 100, 437.48) |

| balanced_140_7_75_2 | 140 | 6193 | 7 | (7, 100, 73.96) | (7, 100, 445.82) | (7, 100, 446.87) |

| balanced_140_7_75_3 | 140 | 6315 | 7 | (7, 100, 0.0) | (7, 100, 436.23) | (7, 100, 437.4) |

| balanced_140_7_75_4 | 140 | 6288 | 7 | (7, 100, 0.0) | (7, 100, 440.22) | (7, 100, 434.73) |

| balanced_140_7_75_5 | 140 | 6327 | 7 | (7, 100, 51.28) | (7, 100, 427.07) | (7, 100, 437.93) |

| Graph | N | (, mean iters.) | |||||

| 4 | 10 | 16 | 20 | ||||

| balanced_60_3_10_1 | 60 | 141 | 3 | (3, 100, 695.42) | (3, 99, 1821.76) | (3, 84, 2764.3) | (3, 89, 3865.74) |

| balanced_60_3_10_2 | 60 | 113 | 3 | (3, 100, 515.2) | (3, 100, 569.14) | (3, 100, 893.56) | (3, 100, 1006.98) |

| balanced_60_3_10_3 | 60 | 133 | 3 | (3, 99, 4693.02) | (3, 94, 6029.05) | (3, 71, 8626.0) | (3, 83, 8887.23) |

| balanced_60_3_10_4 | 60 | 130 | 3 | (3, 100, 943.75) | (3, 100, 1176.21) | (3, 99, 1645.39) | (3, 96, 2417.18) |

| balanced_60_3_10_5 | 60 | 118 | 3 | (3, 100, 642.64) | (3, 100, 977.8) | (3, 100, 1192.56) | (3, 100, 1638.29) |

| balanced_60_3_25_1 | 60 | 286 | 3 | (3, 100, 381.43) | (3, 100, 310.88) | (3, 100, 369.22) | (3, 100, 370.98) |

| balanced_60_3_25_2 | 60 | 294 | 3 | (3, 100, 395.92) | (3, 100, 375.84) | (3, 100, 465.47) | (3, 100, 377.13) |

| balanced_60_3_25_3 | 60 | 307 | 3 | (3, 100, 360.63) | (3, 100, 347.57) | (3, 100, 350.03) | (3, 100, 398.08) |

| balanced_60_3_25_4 | 60 | 290 | 3 | (3, 100, 422.08) | (3, 100, 343.8) | (3, 100, 403.84) | (3, 100, 520.77) |

| balanced_60_3_25_5 | 60 | 305 | 3 | (3, 100, 397.65) | (3, 100, 366.63) | (3, 100, 525.41) | (3, 100, 367.76) |

| balanced_60_3_50_1 | 60 | 617 | 3 | (3, 100, 195.69) | (3, 100, 167.42) | (3, 100, 159.6) | (3, 100, 153.43) |

| balanced_60_3_50_2 | 60 | 620 | 3 | (3, 100, 188.98) | (3, 100, 161.89) | (3, 100, 156.33) | (3, 100, 155.23) |

| balanced_60_3_50_3 | 60 | 615 | 3 | (3, 100, 203.25) | (3, 100, 167.31) | (3, 100, 161.82) | (3, 100, 160.19) |

| balanced_60_3_50_4 | 60 | 607 | 3 | (3, 100, 191.83) | (3, 100, 155.89) | (3, 100, 156.58) | (3, 100, 155.55) |

| balanced_60_3_50_5 | 60 | 585 | 3 | (3, 100, 205.22) | (3, 100, 162.3) | (3, 100, 165.02) | (3, 100, 162.7) |

| balanced_60_3_75_1 | 60 | 922 | 3 | (3, 100, 168.98) | (3, 100, 144.42) | (3, 100, 134.4) | (3, 100, 128.55) |

| balanced_60_3_75_2 | 60 | 887 | 3 | (3, 100, 170.32) | (3, 100, 141.11) | (3, 100, 134.14) | (3, 100, 139.94) |

| balanced_60_3_75_3 | 60 | 873 | 3 | (3, 100, 169.04) | (3, 100, 148.82) | (3, 100, 139.94) | (3, 100, 134.79) |

| balanced_60_3_75_4 | 60 | 895 | 3 | (3, 100, 172.41) | (3, 100, 145.22) | (3, 100, 139.99) | (3, 100, 133.7) |

| balanced_60_3_75_5 | 60 | 886 | 3 | (3, 100, 167.05) | (3, 100, 145.73) | (3, 100, 140.89) | (3, 100, 143.09) |

| balanced_100_5_10_1 | 100 | 401 | 5 | (4, 97, 13190.37) | (4, 81, 16753.02) | (4, 53, 16991.64) | (4, 46, 22098.61) |

| balanced_100_5_10_2 | 100 | 415 | 5 | (5, 100, 398.44) | (5, 100, 264.25) | (5, 100, 254.16) | (5, 100, 302.62) |

| balanced_100_5_10_3 | 100 | 437 | 5 | (5, 100, 511.94) | (5, 100, 321.21) | (5, 100, 344.07) | (5, 100, 341.93) |

| balanced_100_5_10_4 | 100 | 394 | 5 | (4, 74, 17104.27) | (4, 55, 21395.64) | (4, 36, 15245.31) | (4, 36, 18423.08) |

| balanced_100_5_10_5 | 100 | 365 | 5 | (4, 100, 6756.25) | (4, 100, 5133.19) | (4, 92, 7948.3) | (4, 90, 9283.31) |

| balanced_100_5_25_1 | 100 | 997 | 5 | (5, 100, 1912.59) | (5, 100, 1906.21) | (5, 100, 3172.81) | (5, 100, 2970.73) |

| balanced_100_5_25_2 | 100 | 955 | 5 | (5, 100, 2399.05) | (5, 100, 2838.9) | (5, 100, 4031.06) | (5, 98, 4129.43) |

| balanced_100_5_25_3 | 100 | 1007 | 5 | (5, 100, 2155.09) | (5, 100, 2338.59) | (5, 100, 3491.09) | (5, 100, 4366.11) |

| balanced_100_5_25_4 | 100 | 1026 | 5 | (5, 100, 1738.32) | (5, 100, 1549.94) | (5, 100, 2120.71) | (5, 99, 2405.43) |

| balanced_100_5_25_5 | 100 | 1047 | 5 | (5, 100, 1879.04) | (5, 100, 1672.43) | (5, 100, 2205.61) | (5, 99, 2809.86) |

| balanced_100_5_50_1 | 100 | 2032 | 5 | (5, 100, 494.76) | (5, 100, 360.32) | (5, 100, 353.94) | (5, 100, 363.79) |

| balanced_100_5_50_2 | 100 | 2021 | 5 | (5, 100, 486.64) | (5, 100, 364.16) | (5, 100, 356.96) | (5, 100, 362.47) |

| balanced_100_5_50_3 | 100 | 2005 | 5 | (5, 100, 500.43) | (5, 100, 367.94) | (5, 100, 355.03) | (5, 100, 342.84) |

| balanced_100_5_50_4 | 100 | 2014 | 5 | (5, 100, 496.93) | (5, 100, 380.66) | (5, 100, 363.29) | (5, 100, 368.81) |

| balanced_100_5_50_5 | 100 | 2086 | 5 | (5, 100, 468.94) | (5, 100, 357.76) | (5, 100, 352.61) | (5, 100, 343.38) |

| balanced_100_5_75_1 | 100 | 2993 | 5 | (5, 100, 364.13) | (5, 100, 277.5) | (5, 100, 265.89) | (5, 100, 258.95) |

| balanced_100_5_75_2 | 100 | 2990 | 5 | (5, 100, 360.49) | (5, 100, 286.92) | (5, 100, 265.55) | (5, 100, 268.35) |

| balanced_100_5_75_3 | 100 | 3004 | 5 | (5, 100, 366.07) | (5, 100, 288.61) | (5, 100, 268.0) | (5, 100, 266.7) |

| balanced_100_5_75_4 | 100 | 2994 | 5 | (5, 100, 355.45) | (5, 100, 270.02) | (5, 100, 270.02) | (5, 100, 251.35) |

| balanced_100_5_75_5 | 100 | 3042 | 5 | (5, 100, 371.88) | (5, 100, 273.38) | (5, 100, 258.92) | (5, 100, 257.87) |

| balanced_140_7_10_1 | 140 | 826 | 7 | (5, 18, 35862.94) | (5, 93, 24742.58) | (5, 64, 28914.0) | (5, 49, 35911.02) |

| balanced_140_7_10_2 | 140 | 837 | 7 | (5, 1, 57864.0) | (5, 53, 27958.49) | (5, 29, 35530.97) | (5, 14, 33685.79) |

| balanced_140_7_10_3 | 140 | 836 | 7 | (5, 13, 36733.54) | (5, 89, 29304.94) | (5, 55, 35117.38) | (5, 41, 27400.78) |

| balanced_140_7_10_4 | 140 | 880 | 7 | (6, 100, 1512.85) | (6, 100, 732.43) | (6, 100, 784.11) | (6, 100, 773.35) |

| balanced_140_7_10_5 | 140 | 866 | 7 | (5, 1, 16516.0) | (5, 27, 34863.89) | (5, 12, 46650.42) | (5, 3, 41211.67) |

| balanced_140_7_25_1 | 140 | 2079 | 7 | (7, 100, 11995.24) | (7, 100, 10159.86) | (7, 100, 18648.95) | (7, 93, 20292.3) |

| balanced_140_7_25_2 | 140 | 2101 | 7 | (7, 100, 10610.82) | (7, 100, 10400.25) | (7, 95, 17490.02) | (7, 89, 19993.64) |

| balanced_140_7_25_3 | 140 | 2099 | 7 | (7, 100, 12229.11) | (7, 100, 8021.37) | (7, 96, 15969.44) | (7, 91, 18847.48) |

| balanced_140_7_25_4 | 140 | 2073 | 7 | (7, 100, 18558.72) | (7, 100, 11190.06) | (7, 92, 19471.47) | (7, 81, 23240.46) |

| balanced_140_7_25_5 | 140 | 2081 | 7 | (7, 97, 21587.37) | (7, 98, 15336.41) | (7, 87, 24726.77) | (7, 75, 25699.41) |

| balanced_140_7_50_1 | 140 | 4151 | 7 | (7, 100, 1008.77) | (7, 100, 690.55) | (7, 100, 668.54) | (7, 100, 621.5) |

| balanced_140_7_50_2 | 140 | 4210 | 7 | (7, 100, 982.48) | (7, 100, 679.32) | (7, 100, 633.29) | (7, 100, 621.91) |

| balanced_140_7_50_3 | 140 | 4263 | 7 | (7, 100, 949.27) | (7, 100, 675.79) | (7, 100, 637.21) | (7, 100, 586.59) |

| balanced_140_7_50_4 | 140 | 4125 | 7 | (7, 100, 989.17) | (7, 100, 691.0) | (7, 100, 672.0) | (7, 100, 652.75) |

| balanced_140_7_50_5 | 140 | 4157 | 7 | (7, 100, 1004.81) | (7, 100, 680.06) | (7, 100, 641.17) | (7, 100, 648.6) |

| balanced_140_7_75_1 | 140 | 6320 | 7 | (7, 100, 615.39) | (7, 100, 437.48) | (7, 100, 414.44) | (7, 100, 401.85) |

| balanced_140_7_75_2 | 140 | 6193 | 7 | (7, 100, 632.38) | (7, 100, 446.87) | (7, 100, 412.05) | (7, 100, 402.7) |

| balanced_140_7_75_3 | 140 | 6315 | 7 | (7, 100, 610.55) | (7, 100, 437.4) | (7, 100, 414.22) | (7, 100, 393.11) |

| balanced_140_7_75_4 | 140 | 6288 | 7 | (7, 100, 619.77) | (7, 100, 434.73) | (7, 100, 411.04) | (7, 100, 395.9) |

| balanced_140_7_75_5 | 140 | 6327 | 7 | (7, 100, 631.73) | (7, 100, 437.93) | (7, 100, 396.85) | (7, 100, 397.37) |

| Graph | N | (, mean iters.) | ||||

| Greedy | GreedyProp2 | RandomProp2 | ||||

| queen10_10 | 100 | 1470 | 11 | (12, 10, 2424.0) | (12, 10, 4409.7) | (12, 10, 6195.8) |

| games120 | 120 | 638 | 9 | (9, 10, 0.0) | (9, 10, 130.4) | (9, 10, 134.4) |

| queen11_11 | 121 | 1980 | 11 | (13, 9, 20870.7) | (13, 9, 27059.1) | (13, 10, 32604.3) |

| r125.1 | (122, 125*) | 209 | 5 | (5, 10, 0.0) | (5, 10, 90.7) | (5, 10, 104.4) |

| dsjc125.1 | 125 | 736 | 5 | (5, 8, 34609.1) | (5, 8, 29797.5) | (5, 7, 20002.1) |

| dsjc125.5 | 125 | 3891 | 17 | (18, 1, 20353.0) | (19, 10, 7272.5) | (18, 1, 17936.0) |

| dsjc125.9 | 125 | 6961 | 44 | (48, 9, 17507.1) | (48, 8, 19232.4) | (47, 1, 42144.0) |

| miles250 | (125, 128*) | 387 | 8 | (8, 10, 0.0) | (8, 10, 182.7) | (8, 10, 248.2) |

| r125.1c | 125 | 7501 | 46 | (46, 10, 1130.9) | (46, 10, 7622.2) | (46, 10, 8777.6) |

| r125.5 | 125 | 3838 | 36 | (38, 2, 72.0) | (40, 10, 20087.7) | (40, 10, 21611.7) |

| zeroin.i.1 | (126, 211*) | 4100 | 49 | (49, 10, 0.0) | (49, 4, 35532.0) | (49, 7, 24083.0) |

| miles1000 | 128 | 3216 | 42 | (42, 5, 11994.6) | (42, 3, 38704.3) | (42, 6, 20584.8) |

| miles1500 | 128 | 5198 | 73 | (73, 10, 0.0) | (73, 10, 2960.7) | (73, 10, 2937.4) |

| miles500 | 128 | 1170 | 20 | (20, 10, 0.0) | (20, 10, 739.0) | (20, 10, 708.7) |

| miles750 | 128 | 2113 | 31 | (31, 8, 6198.0) | (31, 9, 20833.4) | (31, 8, 24205.4) |

| anna | 138 | 493 | 11 | (11, 10, 0.0) | (11, 10, 393.7) | (11, 10, 386.9) |

| mulsol.i.1 | (138, 197*) | 3925 | 49 | (49, 10, 0.0) | (49, 10, 10602.4) | (49, 10, 8138.3) |

| queen12_12 | 144 | 2596 | 12 | (14, 2, 61455.0) | (14, 2, 37436.5) | (14, 2, 31584.0) |

| zeroin.i.2 | (157, 211*) | 3541 | 30 | (30, 10, 0.0) | (31, 1, 76718.0) | (32, 3, 37033.3) |

| zeroin.i.3 | (157, 206*) | 3540 | 30 | (30, 10, 0.0) | (32, 3, 28664.7) | (31, 1, 28682.0) |

| queen13_13 | 169 | 3328 | 13 | (16, 10, 3766.9) | (16, 10, 3931.6) | (16, 10, 2236.1) |

| mulsol.i.2 | (173, 188*) | 3885 | 31 | (31, 10, 0.0) | (32, 2, 21774.5) | (33, 6, 20340.2) |

| mulsol.i.3 | (174, 184*) | 3916 | 31 | (31, 10, 0.0) | (31, 1, 66168.0) | (32, 2, 53135.5) |

| mulsol.i.4 | (175, 185*) | 3946 | 31 | (31, 10, 0.0) | (33, 7, 36817.3) | (32, 2, 71797.5) |

| mulsol.i.5 | (176, 186*) | 3973 | 31 | (31, 10, 0.0) | (32, 2, 46180.0) | (31, 1, 80600.0) |

| myciel7 | 191 | 2360 | 8 | (8, 10, 0.0) | (8, 10, 444.9) | (8, 10, 838.4) |

| queen14_14 | 196 | 4186 | 14 | (17, 10, 16586.2) | (17, 10, 6326.1) | (17, 10, 12055.2) |

| queen15_15 | 225 | 5180 | 15 | (18, 6, 31860.2) | (18, 8, 42906.9) | (18, 5, 46113.6) |

| dsjc250.9 | 250 | 27897 | 72 | (81, 1, 85070.0) | (82, 1, 10028.0) | (81, 1, 69051.0) |

| r250.1 | 250 | 867 | 8 | (8, 10, 0.0) | (8, 10, 261.9) | (8, 10, 269.6) |

| r250.1c | 250 | 30227 | 64 | (64, 9, 36834.7) | (64, 9, 30456.6) | (64, 7, 34651.6) |

| r250.5 | 250 | 14849 | 65 | (70, 10, 0.0) | (76, 1, 121885.0) | (77, 5, 68487.4) |

| fpsol2.i.1 | (269, 496*) | 11654 | 65 | (65, 10, 0.0) | (65, 7, 77886.9) | (65, 9, 88497.9) |

| flat300_28_0 | 300 | 21695 | 28 | (36, 1, 135010.0) | (36, 2, 93484.0) | (36, 6, 102437.5) |

| school1_nsh | 352 | 14612 | 14 | (14, 9, 21266.3) | (14, 9, 8520.3) | (14, 8, 14151.0) |

| fpsol2.i.2 | (363, 451*) | 8691 | 30 | (30, 10, 0.0) | (38, 2, 83531.0) | (38, 1, 90906.0) |

| fpsol2.i.3 | (363, 425*) | 8688 | 30 | (30, 10, 0.0) | (38, 2, 102963.5) | (36, 1, 141087.0) |

| school1 | 385 | 19095 | 14 | (14, 9, 23410.7) | (14, 9, 6986.8) | (14, 10, 11152.2) |

| le450_15a | 450 | 8168 | 15 | (16, 1, 173285.0) | (17, 10, 6486.9) | (17, 10, 6299.5) |

| le450_15b | 450 | 8169 | 15 | (17, 10, 9.7) | (17, 10, 7481.9) | (16, 2, 136735.0) |

| le450_15c | 450 | 16680 | 15 | (16, 1, 187434.0) | (17, 9, 154051.8) | (16, 1, 123032.0) |

| le450_15d | 450 | 16750 | 15 | (17, 7, 139141.7) | (17, 10, 134227.2) | (16, 1, 175603.0) |

| le450_25c | 450 | 17343 | 25 | (29, 6, 101.0) | (29, 1, 185791.0) | (30, 10, 87136.5) |

| le450_25d | 450 | 17425 | 25 | (29, 6, 178.5) | (30, 10, 78094.9) | (30, 9, 41700.2) |

| le450_5a | 450 | 5714 | 5 | (6, 3, 96363.3) | (6, 5, 28477.6) | (6, 6, 79516.3) |

| le450_5b | 450 | 5734 | 5 | (6, 4, 144962.2) | (6, 4, 72683.5) | (6, 5, 89260.0) |

| dsjr500.1 | 500 | 3555 | 12 | (12, 10, 127.6) | (12, 10, 1596.9) | (12, 10, 1672.4) |

| dsjr500.1c | 500 | 121275 | 85 | (86, 5, 123670.8) | (86, 2, 192601.5) | (87, 6, 145665.0) |

| dsjr500.5 | 500 | 58862 | 122 | (133, 3, 11.3) | (149, 1, 7558.0) | (150, 3, 127779.3) |

| inithx.i.1 | (519, 864*) | 18707 | 54 | (54, 10, 0.0) | (56, 1, 216367.0) | (55, 1, 201835.0) |

| inithx.i.2 | (558, 645*) | 13979 | 31 | (31, 10, 0.0) | (40, 1, 217881.0) | (43, 1, 218428.0) |

| inithx.i.3 | (559, 621*) | 13969 | 31 | (31, 10, 0.0) | (42, 1, 154076.0) | (43, 1, 25165.0) |

| Graph | N | (, mean iters.) | |||||

| 4 | 10 | 16 | 20 | ||||

| games120 | 120 | 638 | 9 | (9, 10, 177.3) | (9, 10, 134.4) | (9, 10, 126.9) | (9, 10, 128.1) |

| queen11_11 | 121 | 1980 | 11 | (15, 10, 2769.0) | (13, 10, 32604.3) | (13, 10, 4902.1) | (13, 10, 2155.5) |

| r125.1 | (122, 125*) | 209 | 5 | (5, 10, 121.9) | (5, 10, 104.4) | (5, 10, 104.2) | (5, 10, 97.0) |

| dsjc125.1 | 125 | 736 | 5 | (5, 1, 33786.0) | (5, 7, 20002.1) | (5, 6, 18344.8) | (5, 1, 10833.0) |

| miles250 | (125, 128*) | 387 | 8 | (8, 10, 317.3) | (8, 10, 248.2) | (8, 10, 243.8) | (8, 10, 148.8) |

| r125.1c | 125 | 7501 | 46 | (50, 1, 59577.0) | (46, 10, 8777.6) | (46, 10, 9069.3) | (46, 9, 15232.7) |

| dsjc125.9 | 125 | 6961 | 44 | (55, 1, 6142.0) | (47, 1, 42144.0) | (45, 1, 4447.0) | (45, 2, 28926.0) |

| dsjc125.5 | 125 | 3891 | 17 | (22, 10, 24273.1) | (18, 1, 17936.0) | (18, 10, 16079.5) | (18, 10, 15916.4) |

| r125.5 | 125 | 3838 | 36 | (43, 6, 19662.5) | (40, 10, 21611.7) | (39, 10, 18904.4) | (38, 2, 31847.5) |

| zeroin.i.1 | (126, 211*) | 4100 | 49 | (49, 10, 18571.4) | (49, 7, 24083.0) | (49, 2, 38714.5) | (49, 1, 14981.0) |

| miles500 | 128 | 1170 | 20 | (20, 10, 4683.0) | (20, 10, 708.7) | (20, 10, 582.5) | (20, 10, 648.7) |

| miles1500 | 128 | 5198 | 73 | (73, 3, 27536.7) | (73, 10, 2937.4) | (73, 10, 2347.4) | (73, 10, 2365.5) |

| miles750 | 128 | 2113 | 31 | (31, 1, 58027.0) | (31, 8, 24205.4) | (31, 10, 9100.0) | (31, 10, 6223.3) |

| miles1000 | 128 | 3216 | 42 | (43, 1, 16999.0) | (42, 6, 20584.8) | (42, 8, 11433.0) | (42, 10, 18577.8) |

| mulsol.i.1 | (138, 197*) | 3925 | 49 | (49, 10, 3733.0) | (49, 10, 8138.3) | (49, 10, 11425.8) | (49, 10, 5581.1) |

| anna | 138 | 493 | 11 | (11, 10, 372.8) | (11, 10, 386.9) | (11, 10, 433.7) | (11, 10, 4241.2) |

| queen12_12 | 144 | 2596 | 12 | (16, 10, 23088.2) | (14, 2, 31584.0) | (14, 10, 10706.6) | (14, 10, 4711.0) |

| zeroin.i.2 | (157, 211*) | 3541 | 30 | (30, 3, 47465.0) | (32, 3, 37033.3) | (32, 1, 27708.0) | (32, 1, 40091.0) |

| zeroin.i.3 | (157, 206*) | 3540 | 30 | (30, 4, 45605.8) | (31, 1, 28682.0) | (32, 1, 41272.0) | (32, 2, 55011.0) |

| queen13_13 | 169 | 3328 | 13 | (18, 10, 2047.7) | (16, 10, 2236.1) | (15, 8, 21428.2) | (15, 10, 7008.4) |

| mulsol.i.2 | (173, 188*) | 3885 | 31 | (31, 4, 27328.5) | (33, 6, 20340.2) | (33, 3, 37431.0) | (33, 6, 34503.5) |

| mulsol.i.3 | (174, 184*) | 3916 | 31 | (31, 4, 60165.0) | (32, 2, 53135.5) | (33, 4, 31618.5) | (33, 4, 60413.5) |

| mulsol.i.4 | (175, 185*) | 3946 | 31 | (31, 5, 40779.6) | (32, 2, 71797.5) | (32, 1, 20705.0) | (33, 4, 47436.8) |

| mulsol.i.5 | (176, 186*) | 3973 | 31 | (31, 2, 21881.0) | (31, 1, 80600.0) | (32, 2, 41175.0) | (33, 4, 61435.2) |

| myciel7 | 191 | 2360 | 8 | (8, 10, 490.2) | (8, 10, 838.4) | (8, 9, 768.7) | (8, 10, 4736.4) |

| queen14_14 | 196 | 4186 | 14 | (19, 10, 17020.5) | (17, 10, 12055.2) | (16, 1, 13392.0) | (16, 6, 35802.7) |

| queen15_15 | 225 | 5180 | 15 | (20, 1, 112258.0) | (18, 5, 46113.6) | (18, 10, 3611.6) | (17, 2, 59238.0) |

| r250.1c | 250 | 30227 | 64 | (68, 1, 39166.0) | (64, 7, 34651.6) | (64, 7, 47749.0) | (64, 6, 48614.7) |

| r250.1 | 250 | 867 | 8 | (8, 10, 382.2) | (8, 10, 269.6) | (8, 10, 261.3) | (8, 10, 337.1) |

| dsjc250.9 | 250 | 27897 | 72 | (107, 1, 47221.0) | (81, 1, 69051.0) | (79, 3, 43635.7) | (78, 6, 79146.7) |

| r250.5 | 250 | 14849 | 65 | (83, 2, 88465.5) | (77, 5, 68487.4) | (74, 2, 65300.5) | (74, 5, 48315.4) |

| fpsol2.i.1 | (269, 496*) | 11654 | 65 | (65, 10, 31441.9) | (65, 9, 88497.9) | (65, 5, 105803.4) | (65, 2, 102137.0) |

| flat300_28_0 | 300 | 21695 | 28 | (45, 4, 50999.5) | (36, 6, 102437.5) | (33, 1, 143072.0) | (32, 1, 88643.0) |

| school1_nsh | 352 | 14612 | 14 | (14, 10, 10003.8) | (14, 8, 14151.0) | (14, 5, 63549.0) | (14, 6, 27482.8) |

| fpsol2.i.3 | (363, 425*) | 8688 | 30 | (35, 2, 119802.0) | (36, 1, 141087.0) | (39, 1, 98128.0) | (40, 1, 162869.0) |

| fpsol2.i.2 | (363, 451*) | 8691 | 30 | (34, 2, 109884.0) | (38, 1, 90906.0) | (37, 1, 145146.0) | (40, 1, 66835.0) |

| school1 | 385 | 19095 | 14 | (14, 10, 7080.2) | (14, 10, 11152.2) | (14, 9, 17417.0) | (14, 10, 11591.4) |

| le450_5b | 450 | 5734 | 5 | (6, 10, 17455.8) | (6, 5, 89260.0) | (7, 10, 19146.4) | (7, 10, 52126.6) |

| le450_5a | 450 | 5714 | 5 | (5, 1, 169416.0) | (6, 6, 79516.3) | (6, 1, 137162.0) | (6, 4, 100053.0) |

| le450_15d | 450 | 16750 | 15 | (28, 1, 23854.0) | (16, 1, 175603.0) | (19, 1, 220765.0) | (20, 1, 194484.0) |

| le450_25c | 450 | 17343 | 25 | (36, 2, 151978.0) | (30, 10, 87136.5) | (28, 10, 77927.4) | (27, 4, 100118.0) |

| le450_25d | 450 | 17425 | 25 | (36, 3, 37371.0) | (30, 9, 41700.2) | (28, 10, 63732.8) | (27, 8, 139768.8) |

| le450_15c | 450 | 16680 | 15 | (29, 10, 24378.9) | (16, 1, 123032.0) | (20, 3, 180997.3) | (20, 1, 187445.0) |

| le450_15b | 450 | 8169 | 15 | (19, 1, 150060.0) | (16, 2, 136735.0) | (16, 10, 16153.4) | (15, 2, 112835.5) |

| le450_15a | 450 | 8168 | 15 | (19, 2, 95430.5) | (17, 10, 6299.5) | (16, 10, 18193.5) | (15, 1, 121410.0) |

| dsjr500.1c | 500 | 121275 | 85 | (93, 1, 84314.0) | (87, 6, 145665.0) | (86, 2, 185044.5) | (86, 1, 202039.0) |

| dsjr500.1 | 500 | 3555 | 12 | (12, 10, 5808.9) | (12, 10, 1672.4) | (12, 10, 1355.3) | (12, 10, 1343.8) |

| dsjr500.5 | 500 | 58862 | 122 | (165, 1, 244534.0) | (150, 3, 127779.3) | (145, 4, 121450.5) | (143, 1, 216451.0) |

| inithx.i.1 | (519, 864*) | 18707 | 54 | (54, 8, 184365.0) | (55, 1, 201835.0) | (58, 2, 188375.0) | (56, 1, 174260.0) |

| inithx.i.2 | (558, 645*) | 13979 | 31 | (38, 1, 181649.0) | (43, 1, 218428.0) | (44, 1, 208224.0) | (44, 1, 113023.0) |

| inithx.i.3 | (559, 621*) | 13969 | 31 | (38, 1, 153621.0) | (43, 1, 25165.0) | (43, 2, 138566.5) | (46, 2, 114019.0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).