1. Introduction

In underground mining and civil infrastructure, rock reinforcement systems are crucial for stabilising excavations and ensuring safety under static and dynamic loading. Rock bolts and adhesive anchors are particularly valued for their adaptability and capacity to provide support in fractured and heterogeneous ground [

1]. The expansion of mining and tunnelling into complex and tropical geological settings has driven demand for robust, high-performance reinforcement solutions [

2]. Adhesive bolts, also known as chemical anchors, are now widely adopted due to their strong bond with diverse substrates, especially where mechanical anchors struggle [

3]. Field and laboratory research has consistently demonstrated that adhesive anchors can outperform mechanical alternatives in fractured and variable ground conditions [

4], provided installation is carefully controlled [

5].

Experimental studies demonstrate that anchor performance in fractured rock is sensitive to bolt position, angle, and installation density [

6], while field instrumentation reveals the complexity of stress transfer between the bolt, grout, and rock mass [

7]. Laboratory and numerical investigations show that both axial and lateral restraint by bolts enhances the shear strength of joints, with optimal installation angles providing maximum strength [

8]. Modern designs account for various failure modes, including tension, shear, and combined loading, as well as the impact of installation quality, rock mass variability, and environmental degradation ([

9,

10,

11,

12]). The long-term performance of anchors, particularly in deep or humid environments, is a major consideration for tunnel safety and stability [

13].

Anchoring effects in fractured rock are also determined by bolt type and pretension, influencing strength, residual capacity, and failure modes [

5]. Deformation models for jointed rock masses account for elastic and crushing failure zones, showing how bolt diameter, anchorage angle, and rock strength affect the extent of crushing and yield modes [

14]. Shear performance remains a critical factor, especially in jointed or fractured rock masses. Modern reviews and experiments demonstrate that shear resistance is governed by a combination of reinforcement, pin, and friction effects, as well as the normal stress and angle of installation [

15]. Classic and recent research has clarified how fully grouted bolts transmit load, with failure often initiated at the grout–rock interface or along bolt ribs, and the presence of multiple shear surfaces increases complexity [

10,

12,

15]. Durability and long-term integrity are increasingly emphasised in design. Factors such as corrosion, cyclic loading, hygrothermal changes, and bond deterioration are major drivers of anchor failure, especially in tropical climates with high humidity and aggressive groundwater [

13,

16]. Field investigations and long-term monitoring have prompted the adoption of new materials, such as corrosion-resistant coatings, polymer grouts, and non-metallic bolts [

17].

Dynamic loading conditions present additional risks and uncertainties. Research has demonstrated that cyclic, seismic, and blast loading can induce progressive bond degradation, micro-cracking at the adhesive–substrate interface, and ultimately brittle or pull-out failure of anchors [

18,

19,

20].

Negative Poisson’s ratio (NPR) bolts have emerged as effective supports in deep mining, increasing peak failure strength and energy absorption under disturbance loads [

21]. D-bolts, a form of energy-absorbing bolt, demonstrate high deformation capacity and distribute load more evenly than conventional bolts, reducing premature failures in highly deformed tunnels [

22]. Energy-absorbing and constant-resistance bolts represent a major innovation for dynamic conditions, where high deformation and impact loads are present. The CEF (compression-expansion-friction) bolt, for example, was developed to provide a controlled, constant resistance and accommodate large displacements, showing enhanced performance in both laboratory and finite element simulations [

20]. These bolts absorb energy through controlled deformation or slippage, which is essential for stability in areas prone to seismic events or rock bursts [

23]. Industry guidelines, codes, and manufacturer recommendations frequently fail to capture the challenges of fractured and variable ground in the tropics [

24,

25]. Additionally, practical in-situ inspection and non-destructive testing of adhesive anchors is still an evolving field, with recent research on acoustic emission and electromagnetic methods showing promise but requiring further validation in tropical and mining environments [

26,

27].

Numerical and experimental comparisons of bond materials show that while the bond type (resin, cement, polymer) affects strength, strata characteristics play a decisive role in performance [

4]. Further, guided wave propagation and numerical methods are now being utilised to assess bond quality and detect defects in installed bolts [

28]. Studies from China, Europe, and Australia have shown regional differences in rock mass response and anchor efficiency, underlining the need for locally validated models and protocols [

29].

Advanced guided wave and acoustic emission methods are used for bolt integrity evaluation, providing new approaches for non-destructive testing of rock bolts [

30]. Load distribution along anchor length and the interface between grout and rock have been quantified, revealing that the highest shear stress is near the bolt tip, and damage typically initiates where shear exceeds bond strength [

31].

Yield-bolts, combining tension and compression elements, demonstrate superior bearing capacity and deformation properties, offering promise for challenging high-stress environments [

32]. The performance of mechanical and friction-based bolts is also influenced by installation details, such as washer geometry and anchor tightening, highlighting the importance of construction quality control [

33].

Research on glass fibre reinforced plastic (GFRP) bolts shows their efficacy in enhancing deformation modulus and strength in 3D-fractured rock, with optimal reinforcement at specific anchor angles [

34]. In the realm of dynamic support, energy-releasing bolts such as the J-bolt provide controlled deformation and energy absorption under repeated impact, maintaining tunnel stability in seismic-prone areas [

35].

Experimental models of non-persistent jointed rock confirm that bolts improve strength and change failure modes, particularly in rocks with intermediate joint angles [

36]. Dynamic finite element analyses have advanced design for slopes supported with anchors, capturing the interaction of anchors and rock mass under earthquake loading [

37].

The mechanical properties of bolts and anchoring agents are a focus for optimisation, with research indicating that stress concentrations are significant at thread bottoms and that matching grout and rod properties is essential for effective bonding [

38]. Jointed rock masses reinforced with bolts show improved compressive strength, controlled crack propagation, and enhanced resistance to deformation, findings confirmed by both physical modelling and FLAC3D simulations [

39].

Innovative approaches to bolt fixation, such as self-expanding mixtures, have demonstrated superior bearing capacity and energy absorption compared to traditional resin or cement-anchored bolts [

40]. International field and laboratory research continues to diversify anchor technology and improve design protocols for variable, high-risk ground [

41].

This breadth of research highlights the critical role of experimental and numerical studies in advancing anchor design for tropical, fractured, and intact rock conditions. By integrating laboratory and high-fidelity numerical modelling, using Phase 2 for surface mines and Unwedge for tunnels, this study aims to bridge gaps between laboratory, simulation, and field performance. The resulting synthesis supports safer, more effective design and deployment of adhesive bolts in the world’s most challenging environments [

42,

43].

4. Discussion of Findings

This study aimed to evaluate the performance and reliability of adhesive anchors, specifically chemical bolts bonded with epoxy and vinyl ester resins, under both static and dynamic loading conditions, within fractured and intact rock environments. A hybrid approach combining experimental testing and numerical simulation (Phase 2 & Unwedge) was adopted to assess pull-out behaviour, bonding integrity, and mechanical resilience. Overall, the findings across methods converged consistently, demonstrating that the selected adhesive bolts provide robust and adaptable reinforcement in demanding mining applications.

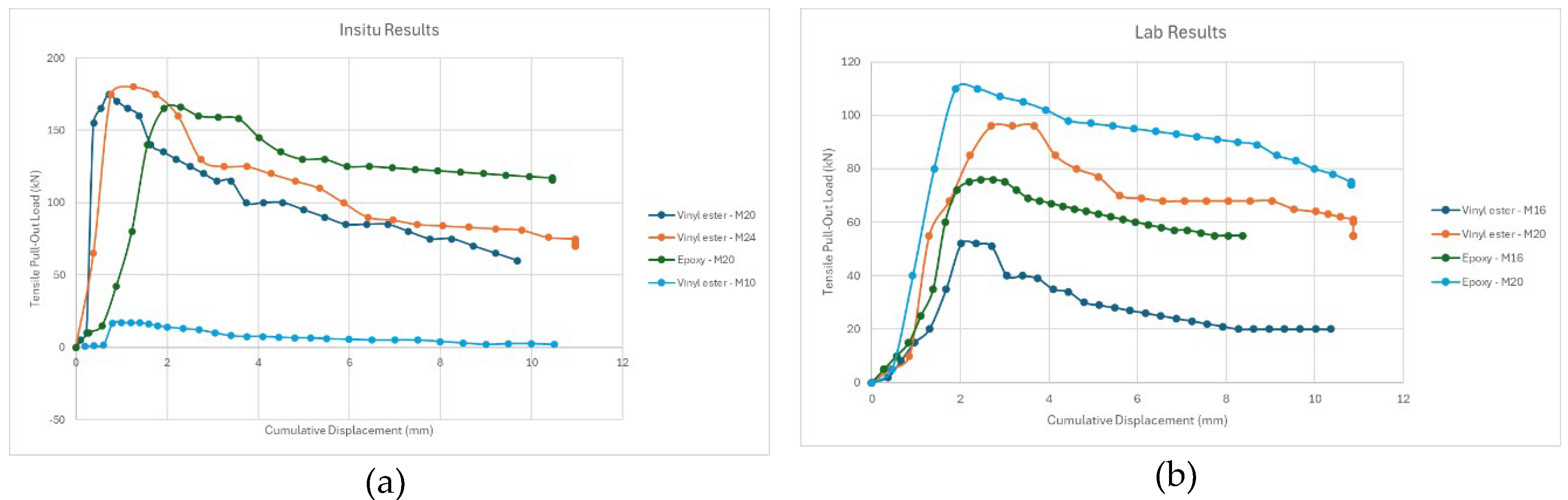

Experimental results from static pull-out tests in both concrete and rock showed high bond capacities, with epoxy-based anchors outperforming vinyl ester variants in terms of both peak load and bond stiffness. This is in line with results from [

96], who observed that epoxy resins yielded superior ductility and energy dissipation, particularly when embedment depths were optimised. Moreover, even in fractured rock configurations, bond integrity was retained, indicating resilience against crack propagation, a key parameter in dynamic mining environments.

The Phase 2 analysis revealed progressive stress redistribution and strain concentration patterns around excavation boundaries, particularly under unsupported scenarios. When supports were introduced, especially with reduced bolt spacing (<1 m), bolt mobilisation improved substantially, arresting wedge detachment and reducing tensile failures. This confirms findings from [

97], where pre-tensioned resin anchors exhibited reduced displacement and increased peak resistance across varying rock moduli.

In the Unwedge-supported simulations, dense bolt spacings (0.5 m to 1 m) showed high wedge stability, with FoS values exceeding critical thresholds across all geometries. At wider spacings (≥1.5 m), bolt participation decreased, and roof instability reemerged, validating earlier centrifuge-based observations by [

90]. These findings are reinforced by thermal degradation results from [

98] , who noted a 6.6–31.3% loss in bond strength under elevated temperature, a relevant factor in tropical underground conditions.

Figure 33a displayed minimal plasticity, aligning with low-stress conditions in closely spaced bolt configurations, while Figure 33b indicated extensive yielding consistent with wider spacing. These outcomes paralleled earlier FEM investigations by [

99], demonstrating that both numerical and experimental results can reliably predict long-term anchor performance.

Across experimental and numerical methods, results align with contemporary literature that supports the use of epoxy and vinyl ester chemical anchors for underground reinforcement. The novelty of this study lies in its integration of experimental pull-out behaviour with 3D stress-mapped simulations in both surface and tunnel geometries, a critical link missing in many earlier studies. Additionally, while many authors have assessed bolt performance under static conditions, this study advances understanding by evaluating dynamic load readiness, specifically through failure mode verification and strain visualisation under load transitions. Moreover, the hybrid verification approach (including Phase2) adds confidence to the generalizability of the findings across geological contexts.

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

This study substantiates the reliability and applicability of chemical anchors (adhesive bolts) in complex mining scenarios, including environments subjected to dynamic loading, fractured rock conditions, and elevated thermal gradients. The findings demonstrate that epoxy resin systems exhibit superior mechanical resilience under high-load and high-temperature conditions, making them particularly suitable for demanding underground applications. Moreover, support systems configured with closely spaced bolts, typically less than 1.0 meters apart, consistently showed enhanced stability through improved load distribution and wedge confinement. The numerical simulations conducted throughout this study further reinforced these observations, offering predictive insight into failure mechanisms and support behaviour across varying geometries and stress regimes. Collectively, these outcomes confirm that adhesive bolts possess the mechanical and operational attributes necessary for reliable integration into modern mine support systems, with clear benefits in terms of structural integrity, safety, and long-term durability.

The study utilised Rocscience RS2 (Phase 2 and Unwedge) as the primary numerical modelling platform to simulate both surface and subsurface excavation scenarios. The RS2 simulations, combined with experimental data, confirmed that short-length adhesive bolts (190 mm–250 mm), when embedded correctly and spaced optimally, effectively mitigated tensile failure and reduced the propagation of stress concentration zones. Dynamic resilience was particularly evident in scenarios involving wedge instability, where resin-grouted anchors curtailed detachment and deformation propagation across fractured interfaces. Based on these findings, the following technical recommendations are proposed:

For fractured or highly stressed rock environments, bolt spacing should not exceed 1.0 m, especially when dealing with asymmetric wedge geometries or regions prone to seismic activity.

Epoxy-based resins should be prioritised for high-temperature zones and long-term static or cyclic loading, while vinyl ester systems may be appropriate for environments demanding early-age strength development.

Incorporating rock mass classification, joint persistence, and stress anisotropy into numerical simulations significantly enhances predictive reliability and should become standard in preliminary design stages.

Long-term in-situ performance studies of resin anchors under real mine conditions are necessary to validate laboratory findings and refine models under operational variability.

Engineering codes and mine design guidelines should integrate time-dependent curing effects, resin-specific bond-slip profiles, and spacing optimisation strategies derived from dynamic interaction studies.

The research presented herein bridges a crucial knowledge gap in the performance characterisation of adhesive anchors in mining contexts, particularly within tropical geological settings. By integrating comprehensive laboratory testing with advanced numerical modelling in RS2, the study offers a high-fidelity evaluation of bolt performance under both static and dynamic loading. These findings not only validate the deployment of chemical anchors in structurally demanding applications but also inform safer, data-driven support strategies for future mining projects. This contribution stands to enhance both academic understanding and practical engineering of underground support systems in some of the world's most challenging geological environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.M., J.F, and F.S.; methodology, T.M, J.M., and F.S.; software, T.M., J.M., and F.S.; validation, T.M., I.T., and F.S.; formal analysis, T.M., investigation, T.M.; resources, T.M., J.M., and F.S.; data curation, T.M., J.M., and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, T.M.,; writing—review and editing, T.M., J.M., and F.S.; visualization, T.M., J.M., F.S.; supervision, J.M, and F.S.; project administration, J.M., and F.S.; funding acquisition, T.M., J.M., and F.S

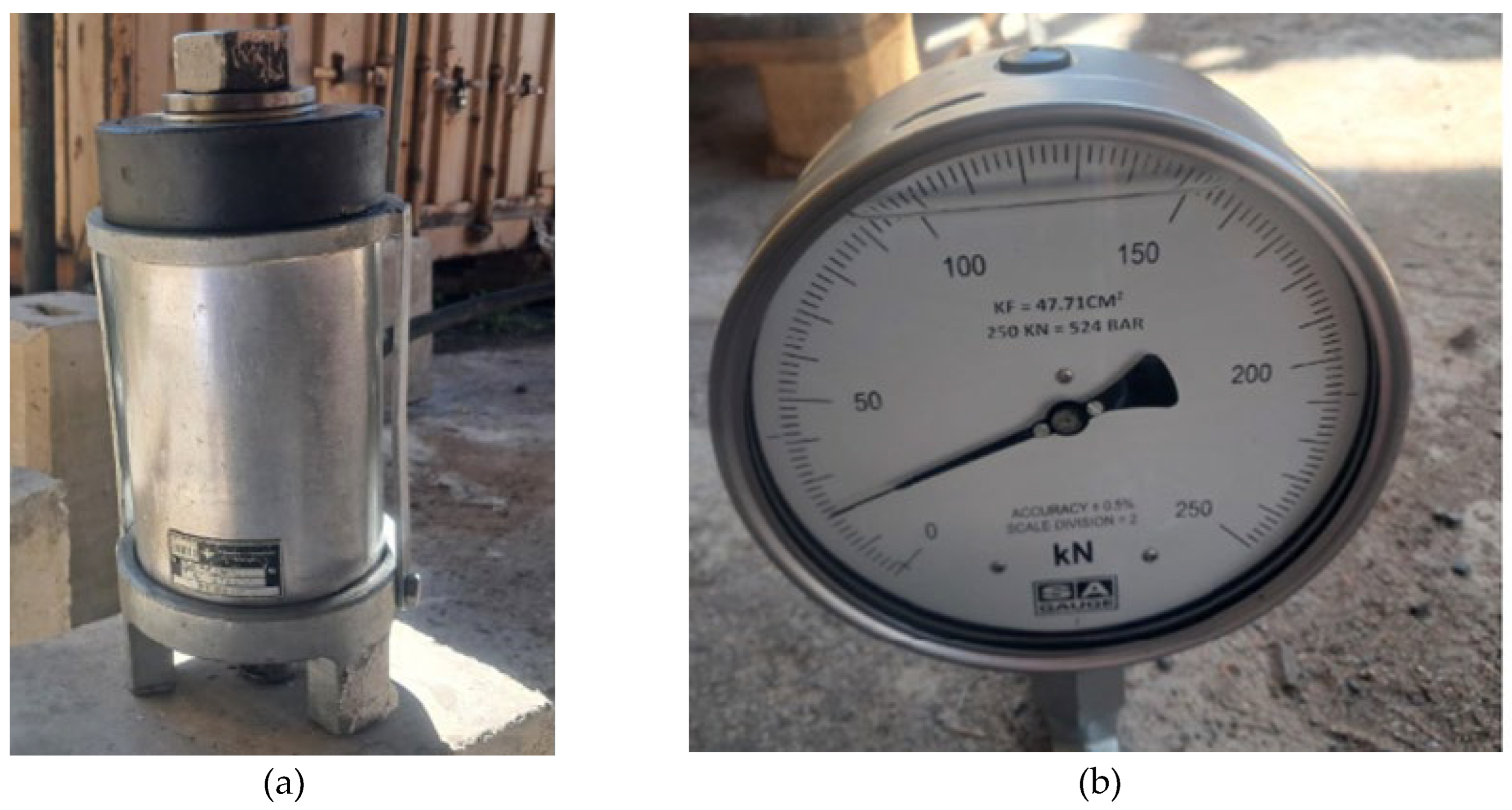

Figure 1.

Pull-out test apparatus. (a) Tripod pull-out rig, and (b) calibrated 250kN pressure gauge.

Figure 1.

Pull-out test apparatus. (a) Tripod pull-out rig, and (b) calibrated 250kN pressure gauge.

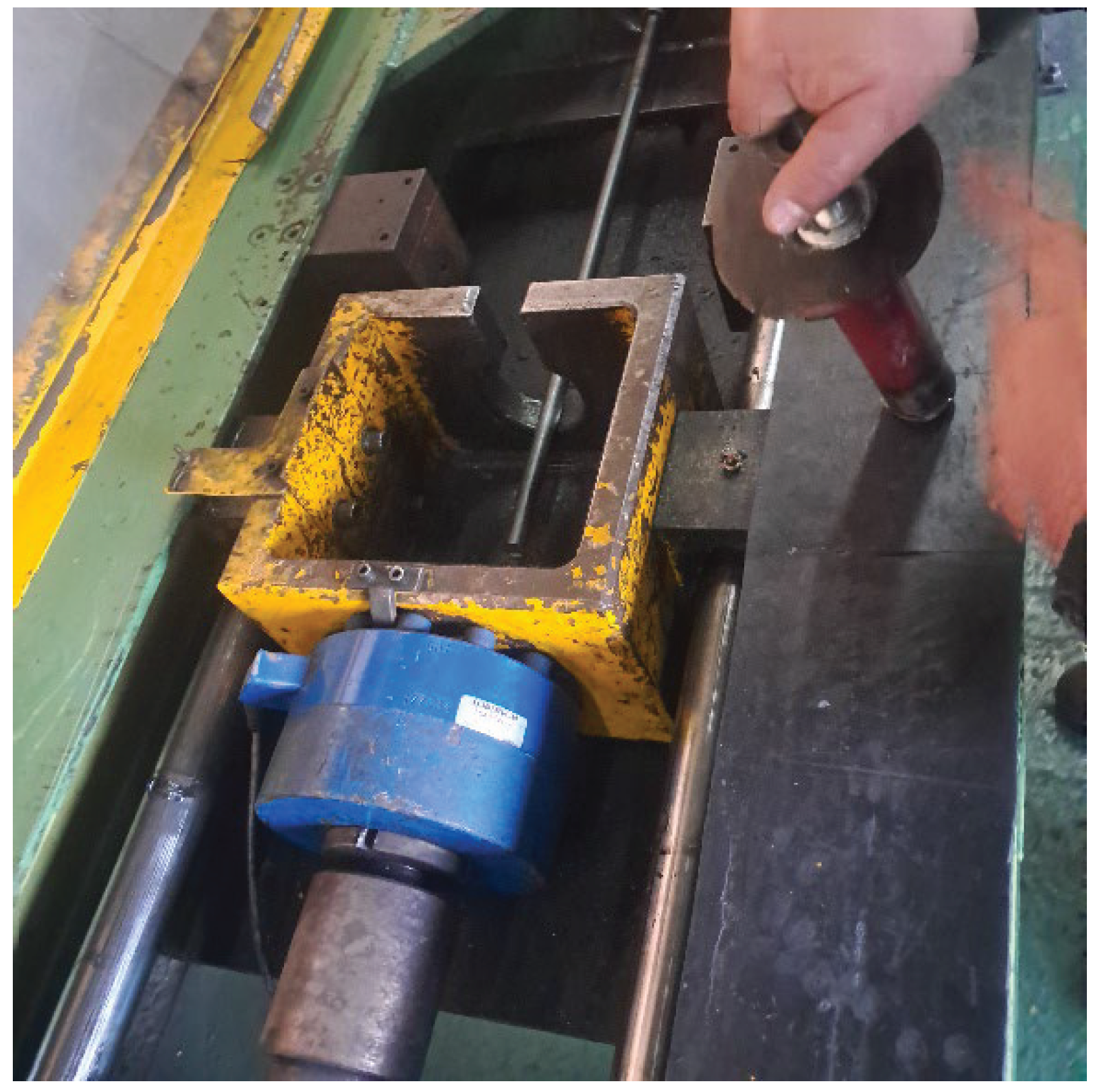

Figure 2.

Field static pull-out test setup at Videx Mining Facility.

Figure 2.

Field static pull-out test setup at Videx Mining Facility.

Figure 3.

Installed bolt prior to testing.

Figure 3.

Installed bolt prior to testing.

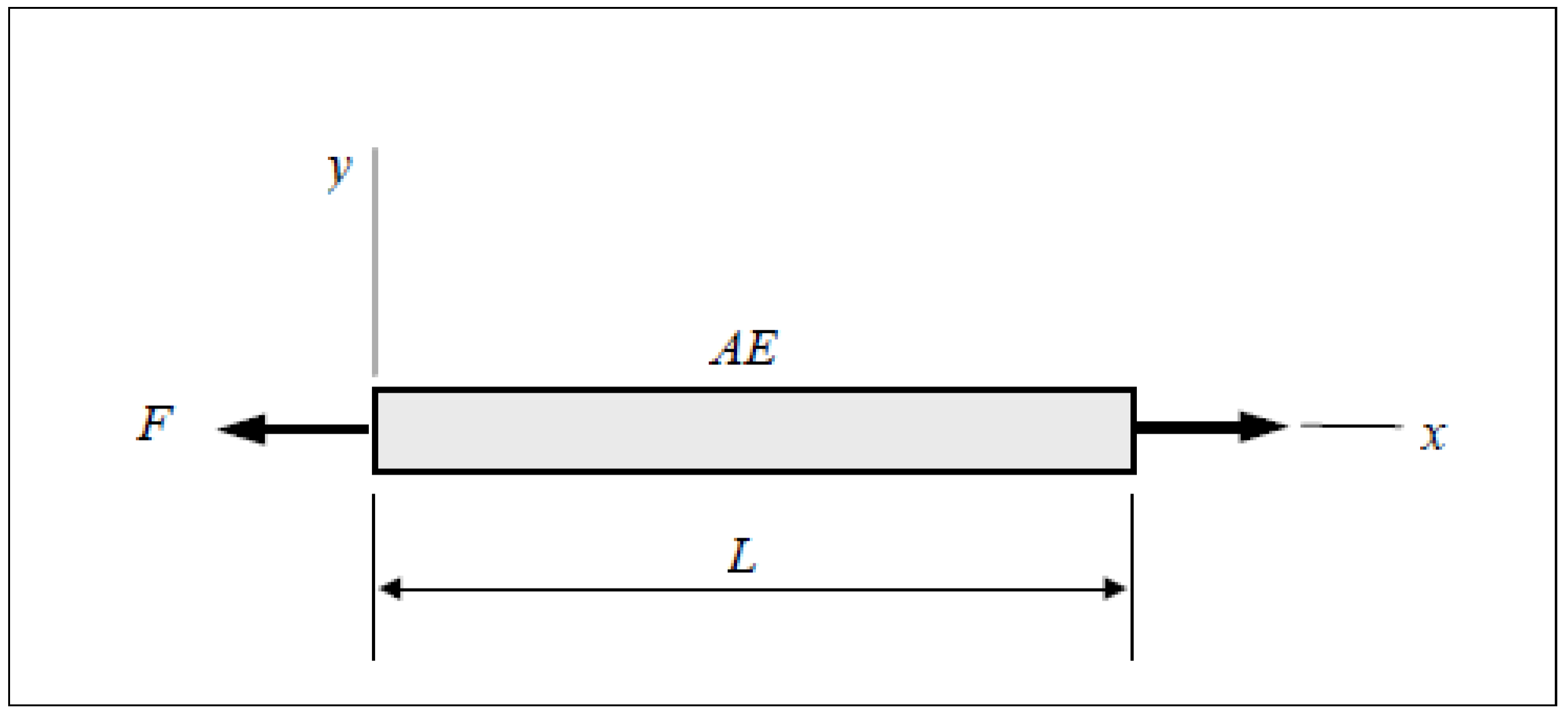

Figure 4.

Schematic of end-anchored bolt model.

Figure 4.

Schematic of end-anchored bolt model.

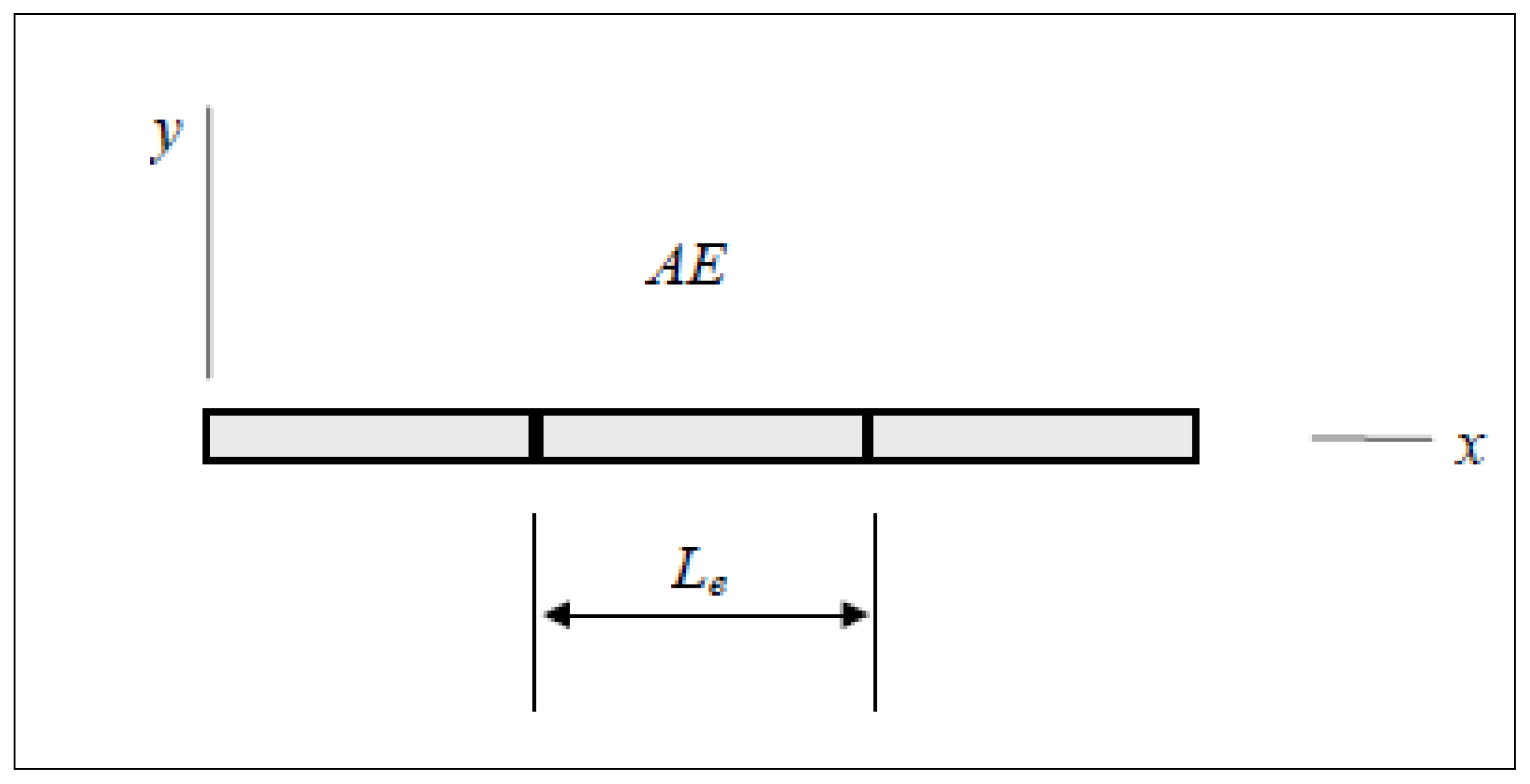

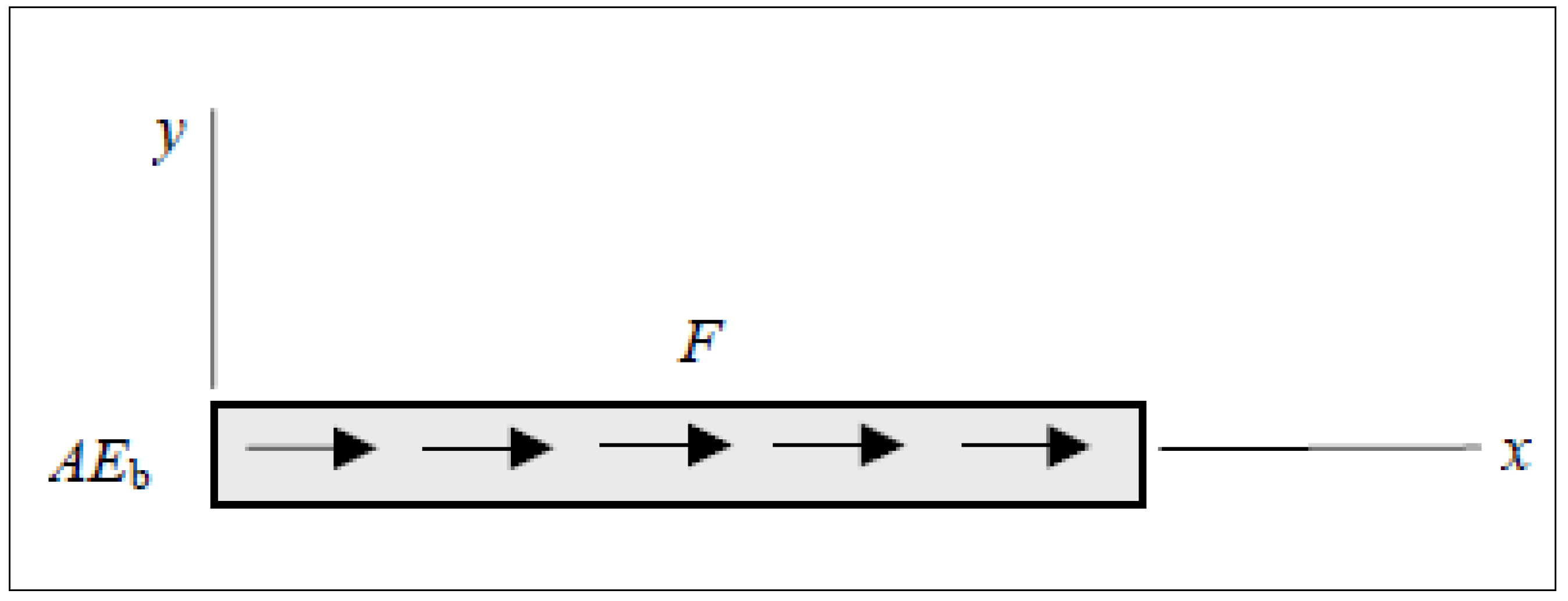

Figure 5.

Mesh discretisation of a fully bonded adhesive bolt.

Figure 5.

Mesh discretisation of a fully bonded adhesive bolt.

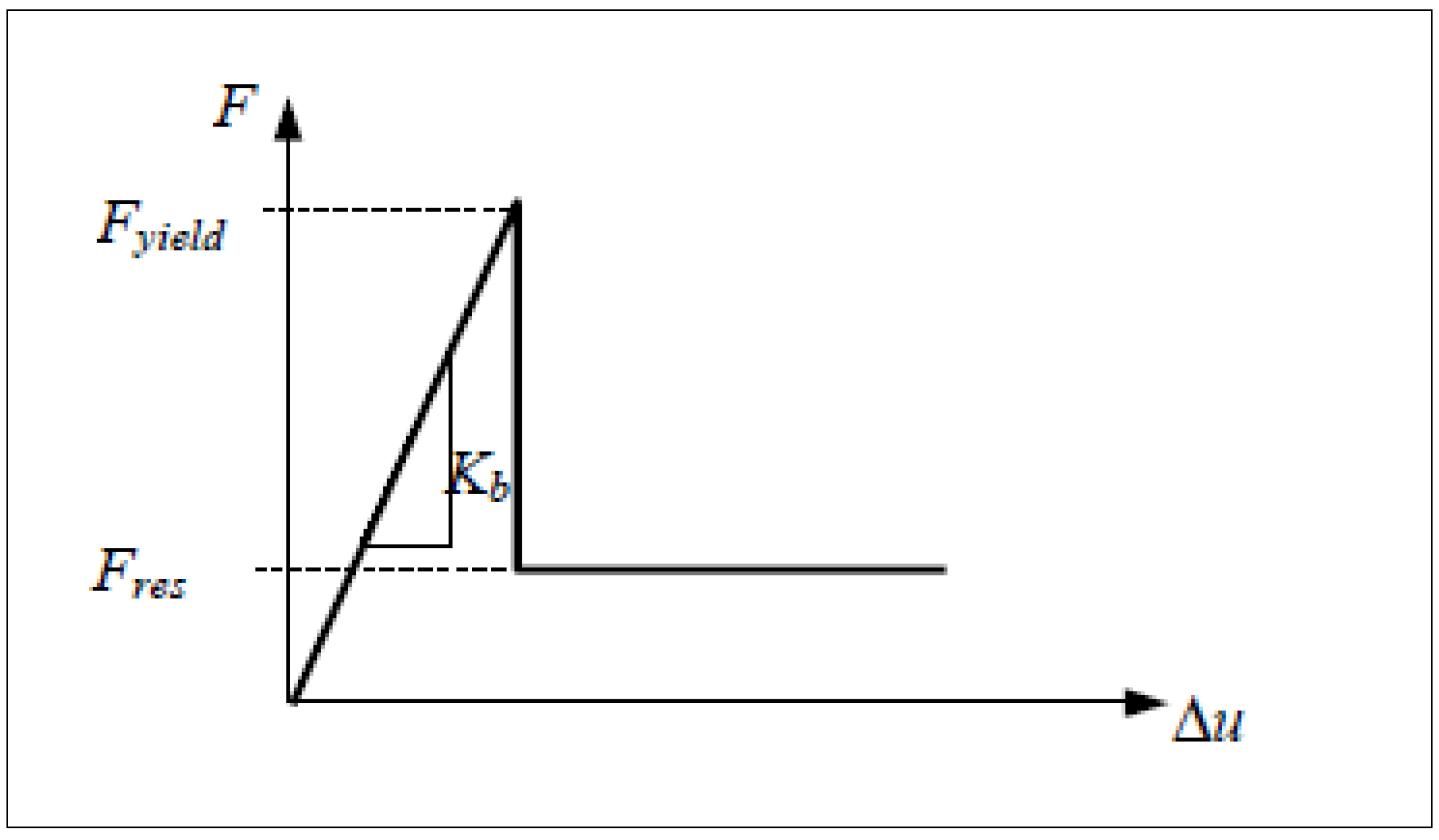

Figure 6.

Force–elongation behaviour for bolt element, showing yield and residual force plateau.

Figure 6.

Force–elongation behaviour for bolt element, showing yield and residual force plateau.

Figure 7.

Shear bolt model with displacement interaction across the grout/rock interface [

51].

Figure 7.

Shear bolt model with displacement interaction across the grout/rock interface [

51].

Figure 6.

Example of mesh and bolt configuration for Phase 2 simulation.

Figure 6.

Example of mesh and bolt configuration for Phase 2 simulation.

Figure 7.

Simulated force distribution and displacement field in the Phase 2 model.

Figure 7.

Simulated force distribution and displacement field in the Phase 2 model.

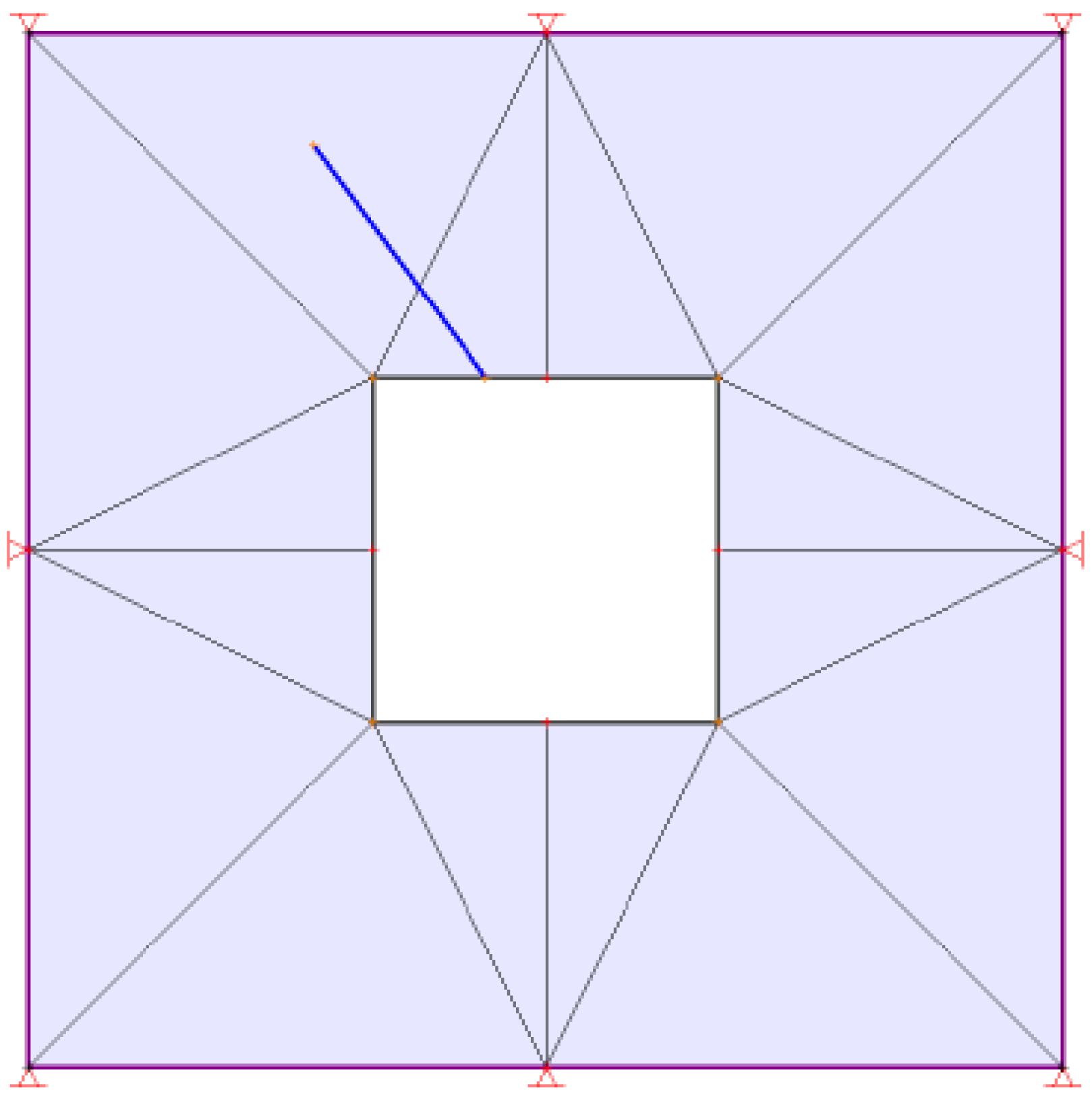

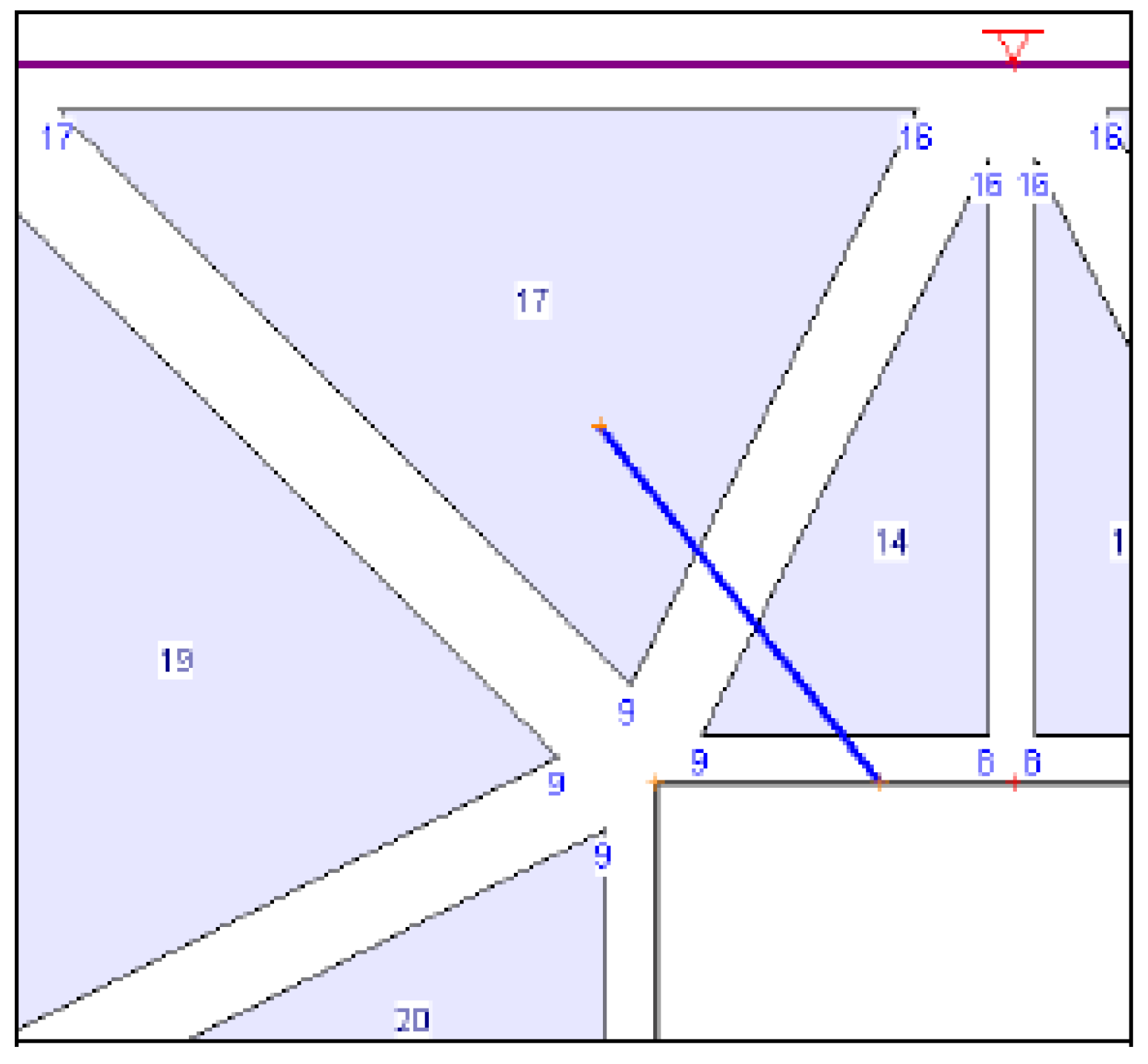

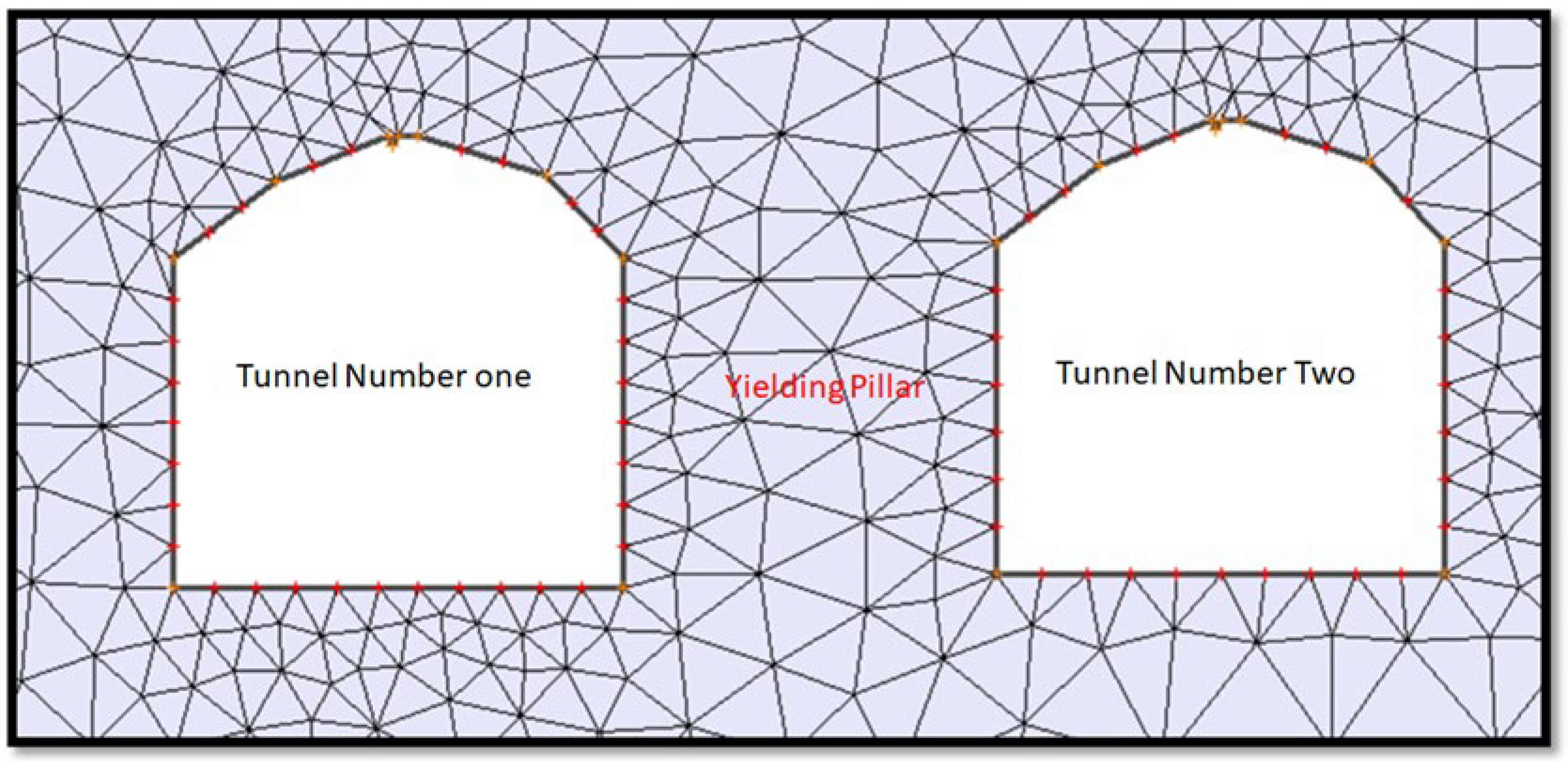

Figure 8.

Tunnel and pillar geometry with applied 3-noded mesh in Phase 2.

Figure 8.

Tunnel and pillar geometry with applied 3-noded mesh in Phase 2.

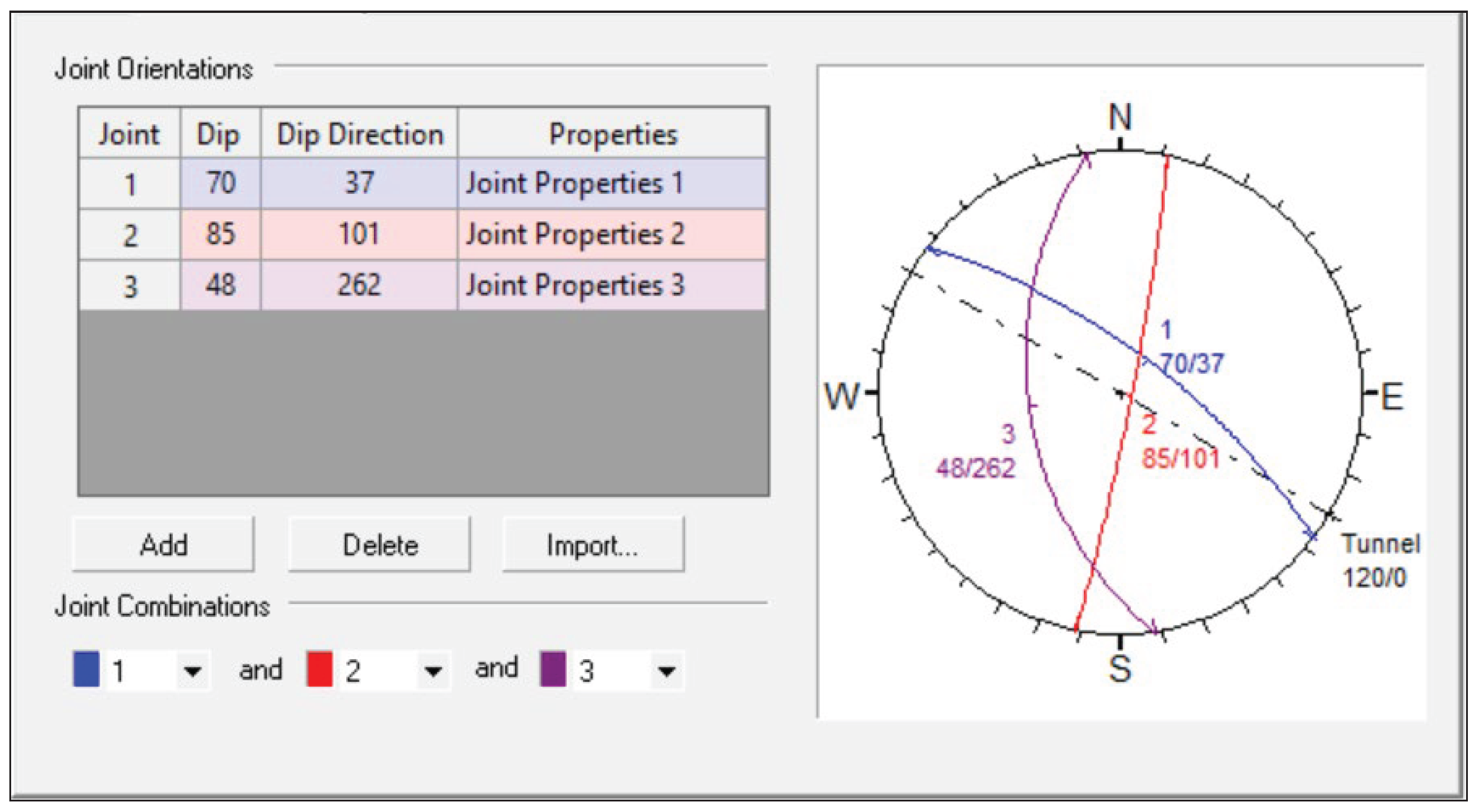

Figure 10.

Stereonet of simulated joint sets for surface excavation model.

Figure 10.

Stereonet of simulated joint sets for surface excavation model.

Figure 11.

Summary of load-displacement curves for all vinyl ester and epoxy bolts in the lab and in situ tests, (a) Summary of load-displacement curves for vinyl ester & epoxy bolts (in situ results) and (b) Summary of load-displacement curves for vinyl ester & epoxy bolts (lab results).

Figure 11.

Summary of load-displacement curves for all vinyl ester and epoxy bolts in the lab and in situ tests, (a) Summary of load-displacement curves for vinyl ester & epoxy bolts (in situ results) and (b) Summary of load-displacement curves for vinyl ester & epoxy bolts (lab results).

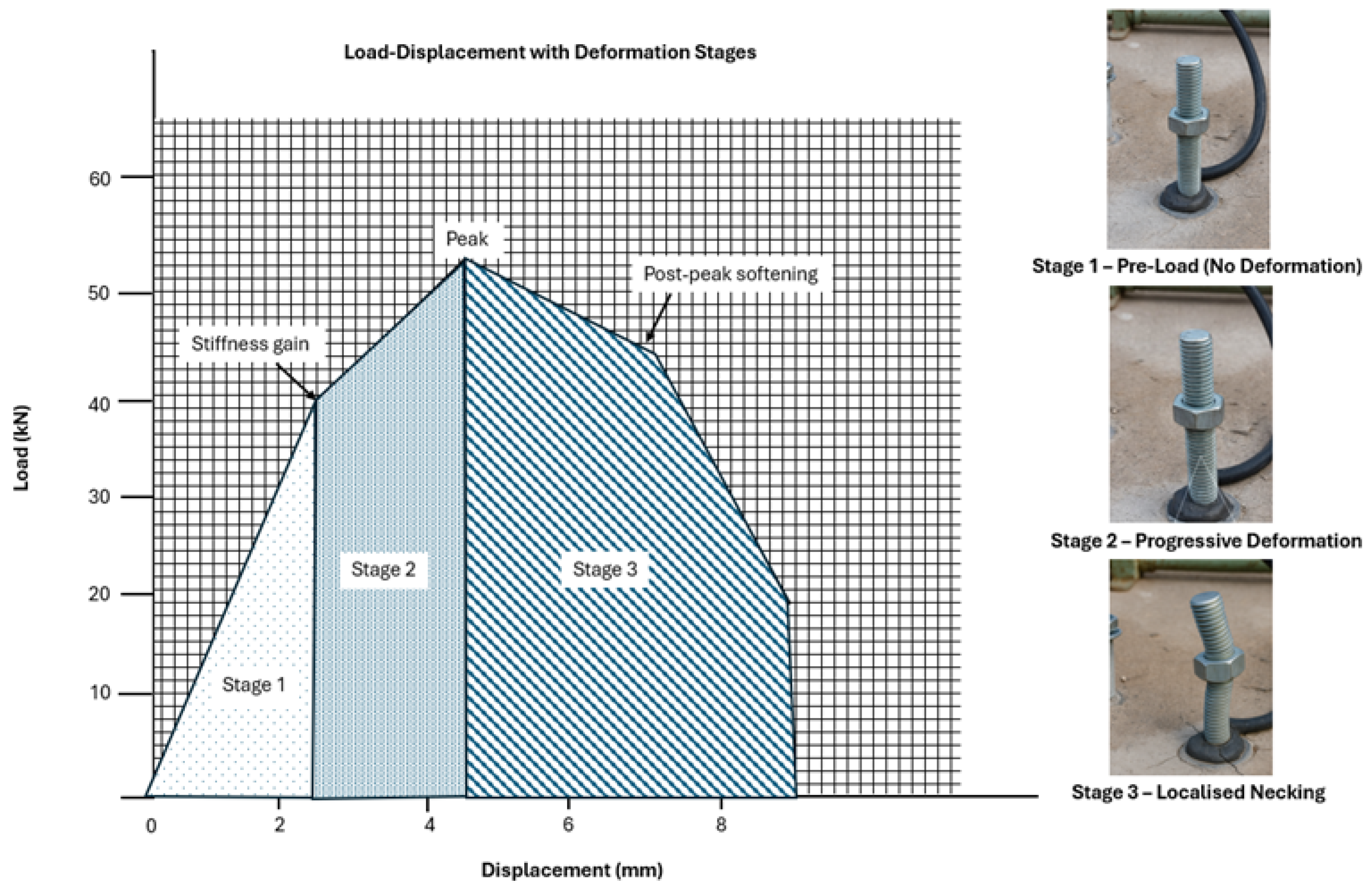

Figure 12.

Load–displacement response of an M16 vinyl-ester bolt in intact rock, showing stiffness gain, peak capacity and post-peak softening.

Figure 12.

Load–displacement response of an M16 vinyl-ester bolt in intact rock, showing stiffness gain, peak capacity and post-peak softening.

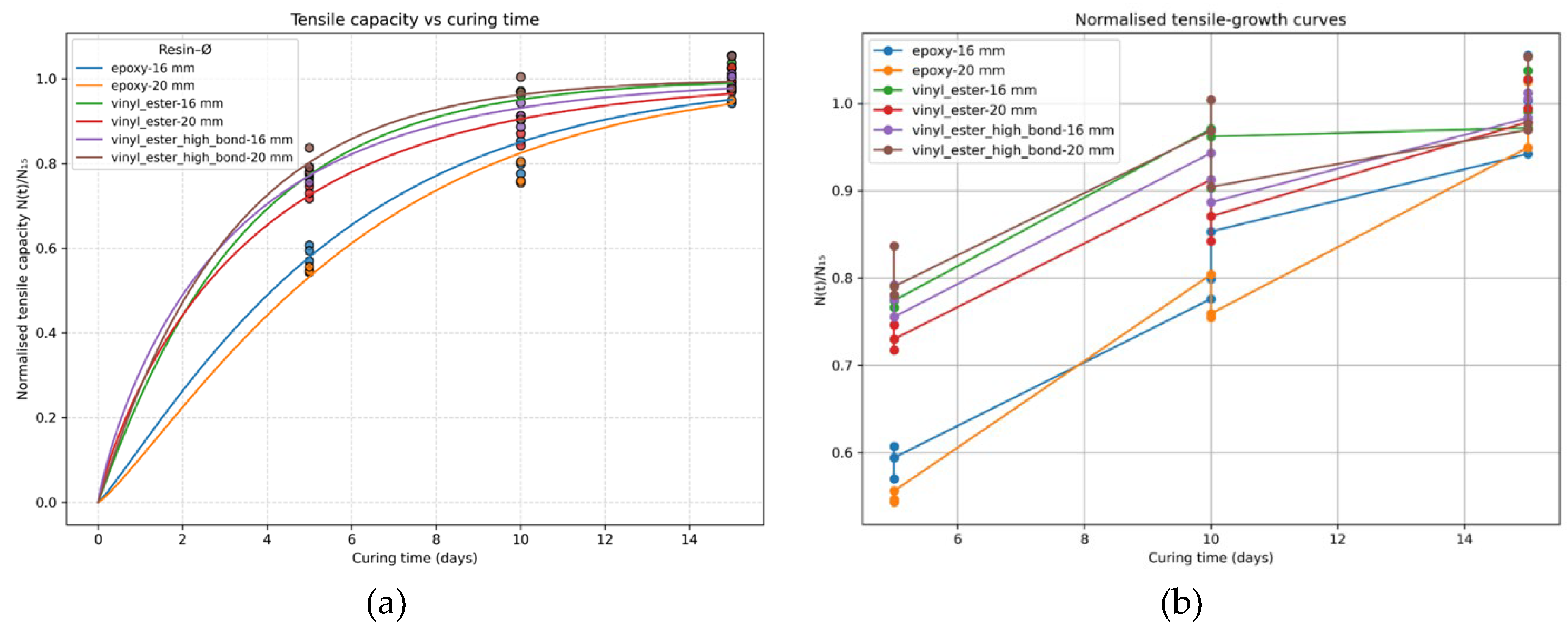

Figure 13.

(a) Mean tensile capacity as a function of curing time. Error bars show ±1 SD (n = 3). Vinyl-ester systems show superior early strength compared to epoxy. (b) Shear capacity development over curing time for six anchor configurations.

Figure 13.

(a) Mean tensile capacity as a function of curing time. Error bars show ±1 SD (n = 3). Vinyl-ester systems show superior early strength compared to epoxy. (b) Shear capacity development over curing time for six anchor configurations.

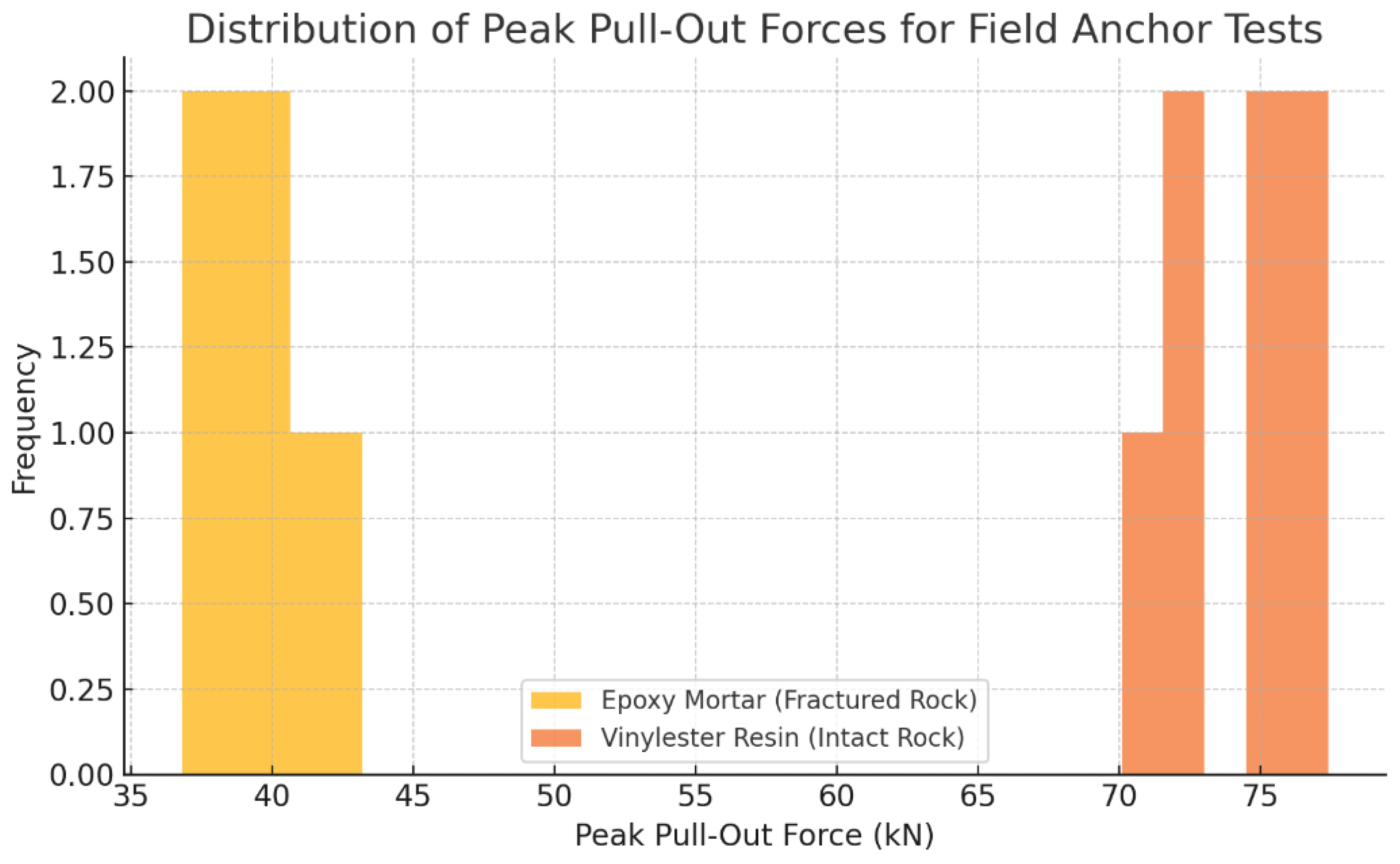

Figure 14.

Distribution of peak pull-out forces for adhesive-bonded bolts in the field, comparing epoxy mortar (fractured rock) and vinyl ester resin (intact rock) systems.

Figure 14.

Distribution of peak pull-out forces for adhesive-bonded bolts in the field, comparing epoxy mortar (fractured rock) and vinyl ester resin (intact rock) systems.

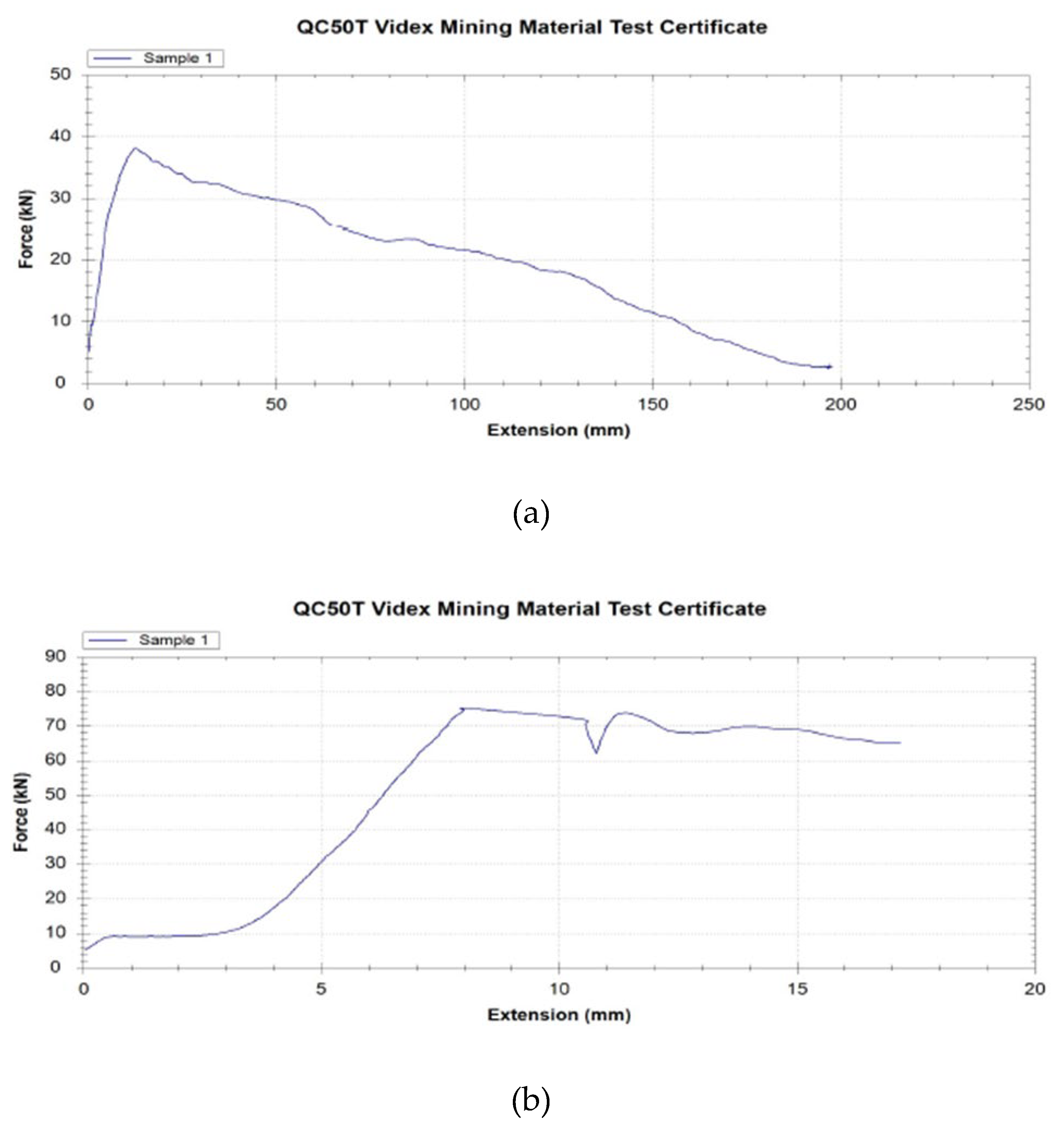

Figure 15.

(a) Load-extension curve for a bolt installed in fractured rock (epoxy mortar, 20 mm × 250 mm). (b) Load-extension curve for a bolt installed in intact rock (vinyl ester resin, 20 mm × 250 mm).

Figure 15.

(a) Load-extension curve for a bolt installed in fractured rock (epoxy mortar, 20 mm × 250 mm). (b) Load-extension curve for a bolt installed in intact rock (vinyl ester resin, 20 mm × 250 mm).

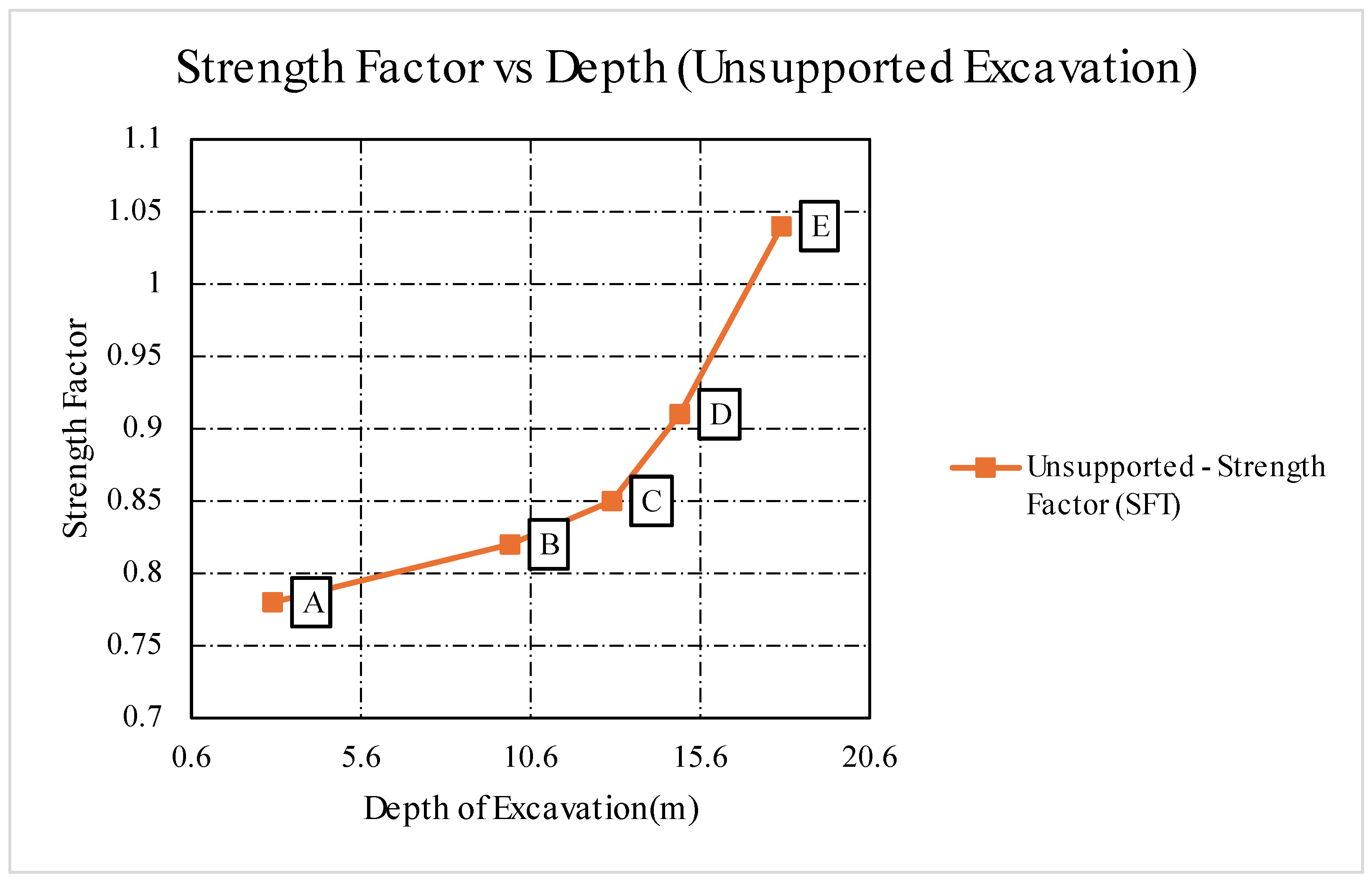

Figure 16.

Strength Factor vs. Depth for Stage 3 (Unsupported Excavation).

Figure 16.

Strength Factor vs. Depth for Stage 3 (Unsupported Excavation).

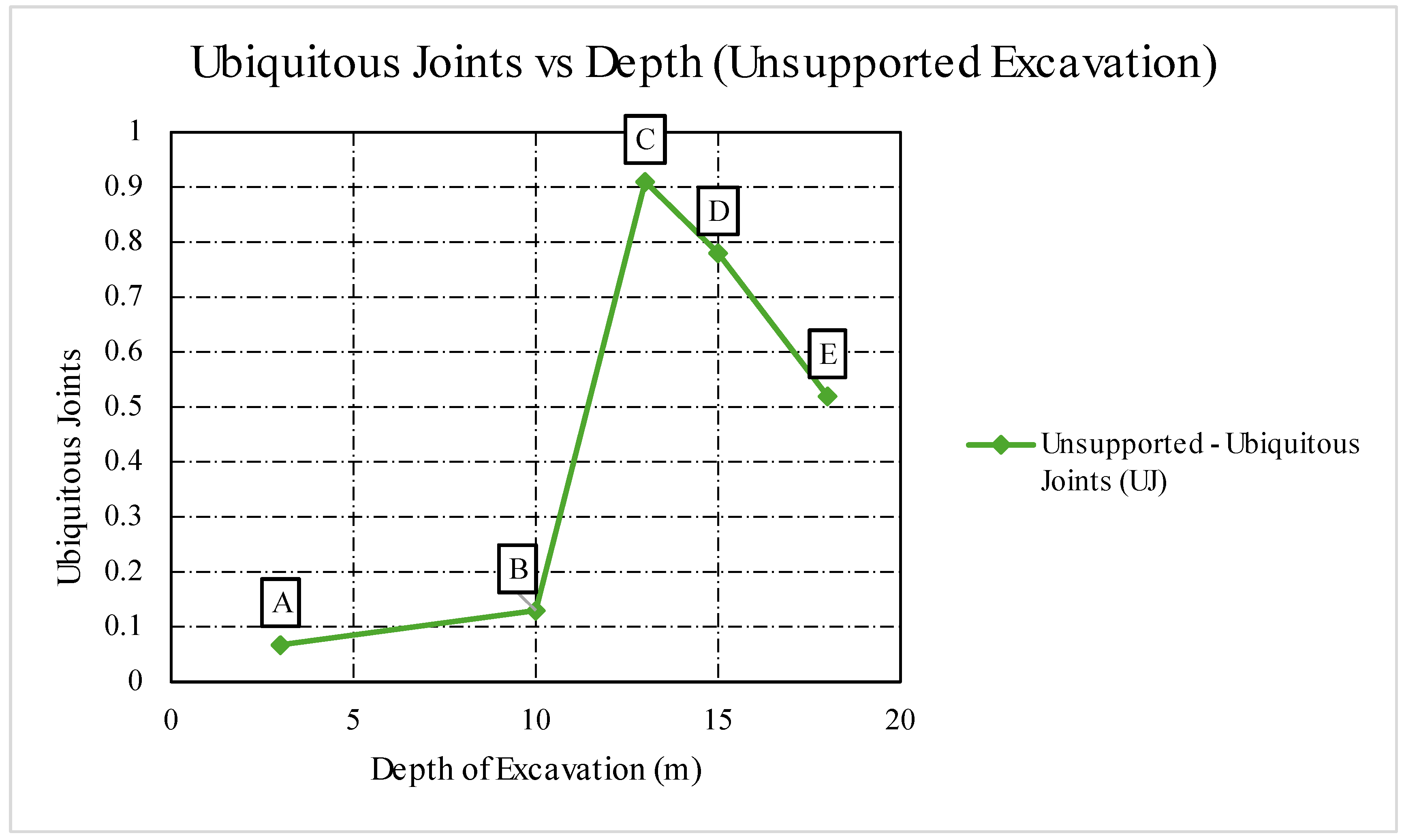

Figure 17.

Ubiquitous Joints vs. Depth for Stage 3 (Unsupported Excavation).

Figure 17.

Ubiquitous Joints vs. Depth for Stage 3 (Unsupported Excavation).

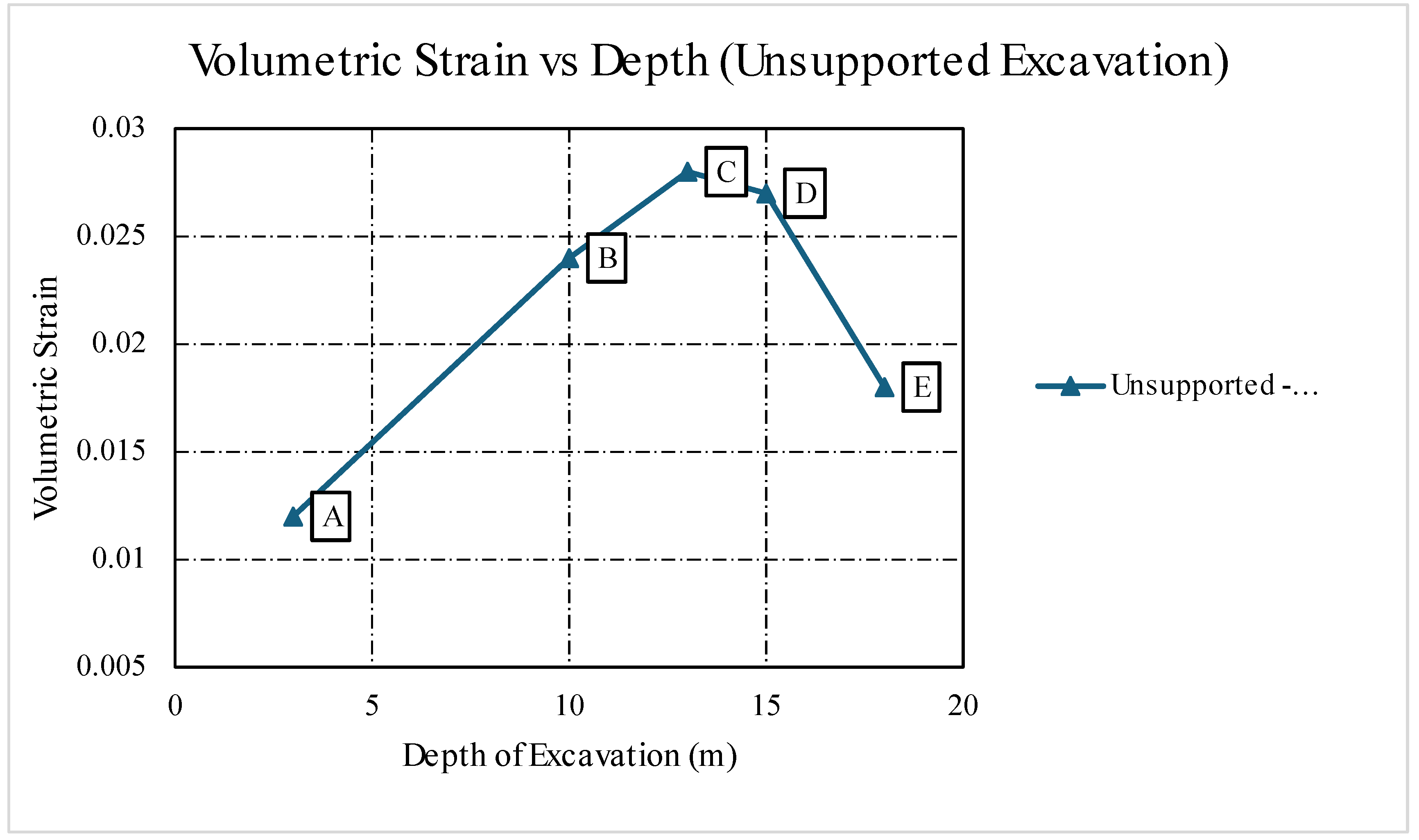

Figure 18.

Volumetric Strain vs. Depth for Stage 3 (Unsupported Excavation).

Figure 18.

Volumetric Strain vs. Depth for Stage 3 (Unsupported Excavation).

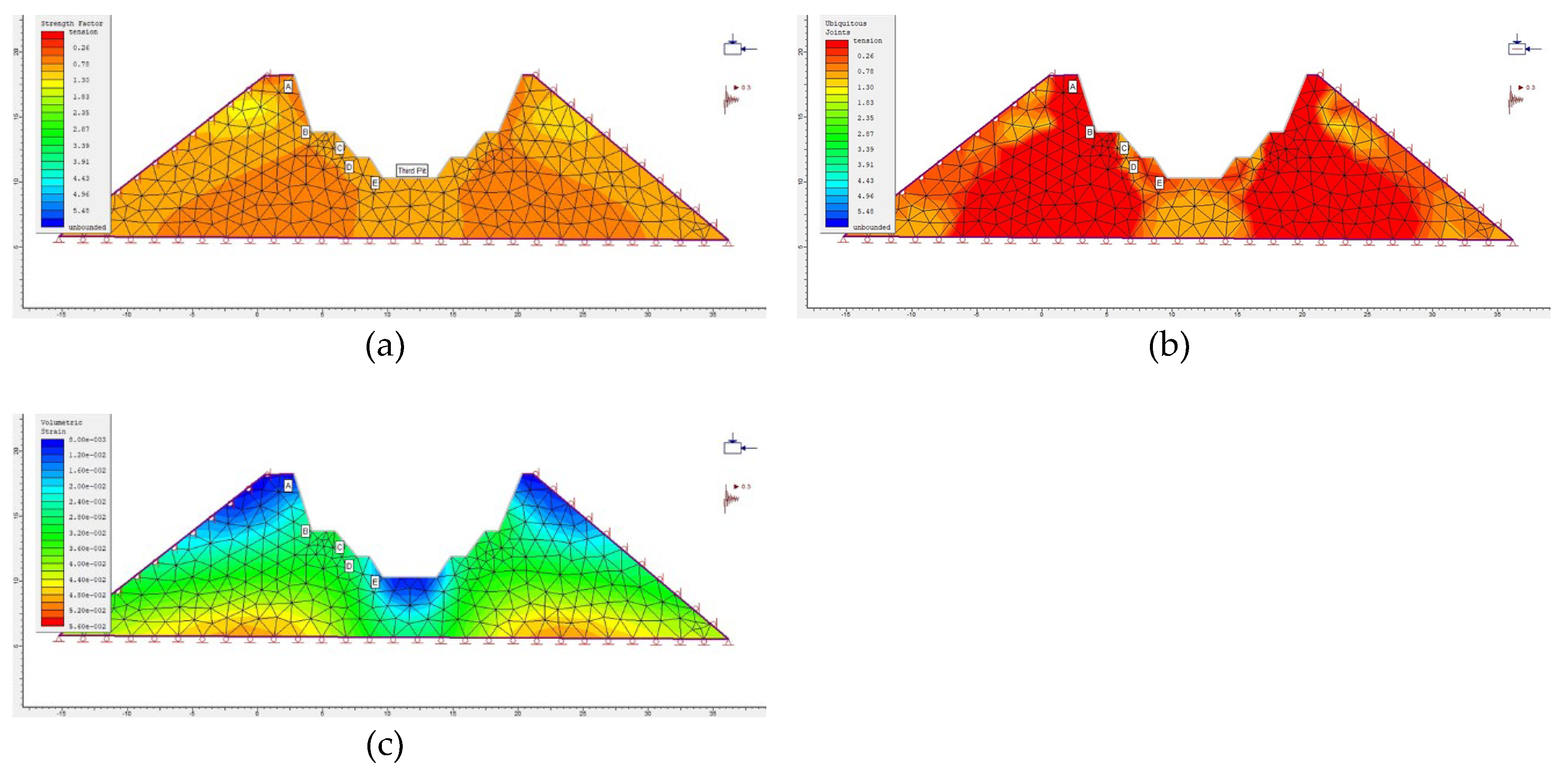

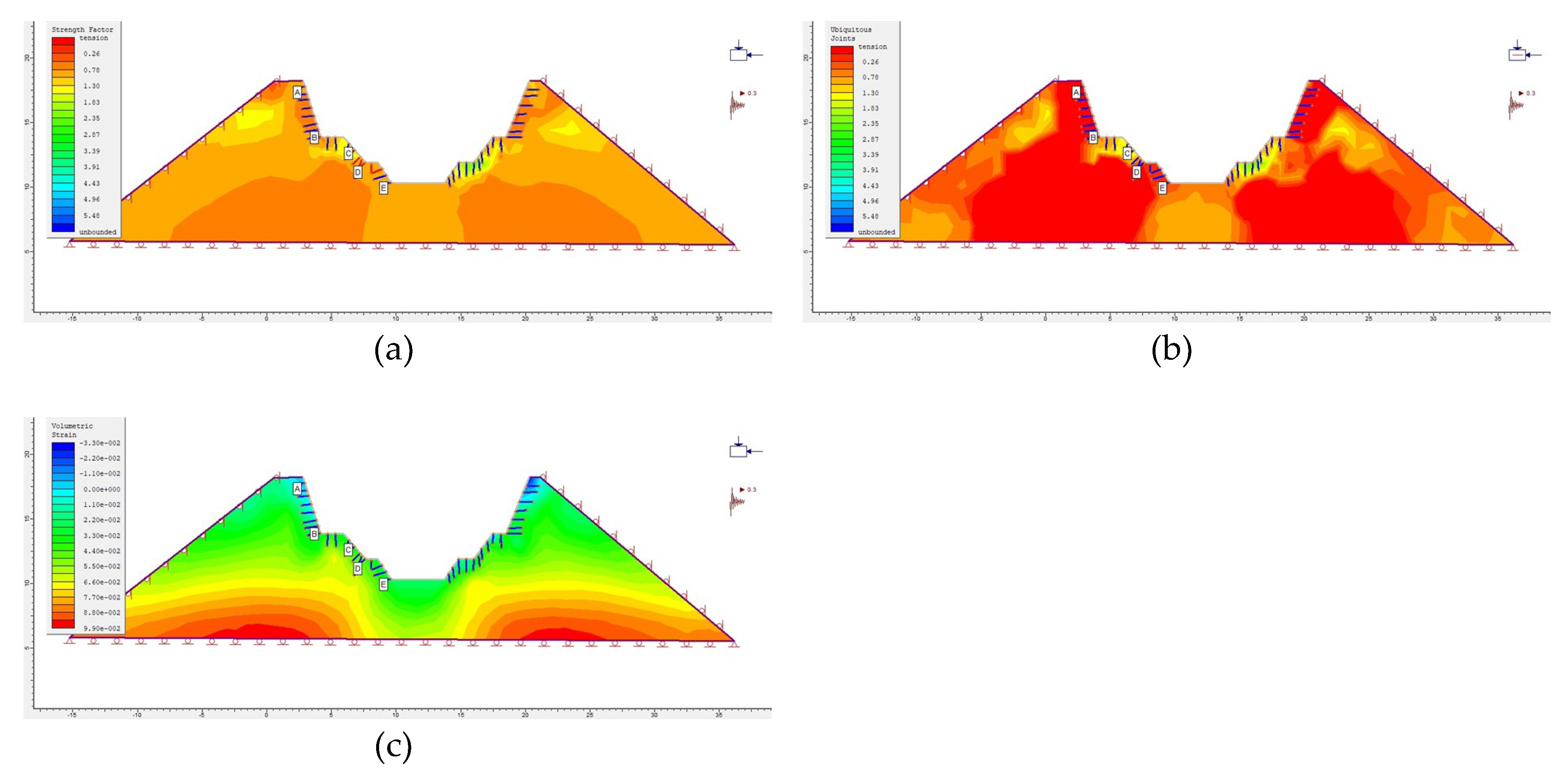

Figure 19.

(a) Modelled distribution of strength factor across the excavation (Stage 3). (b) Modelled distribution of ubiquitous joint factor (Stage 3). (c) Modelled distribution of volumetric strain (Stage 3).

Figure 19.

(a) Modelled distribution of strength factor across the excavation (Stage 3). (b) Modelled distribution of ubiquitous joint factor (Stage 3). (c) Modelled distribution of volumetric strain (Stage 3).

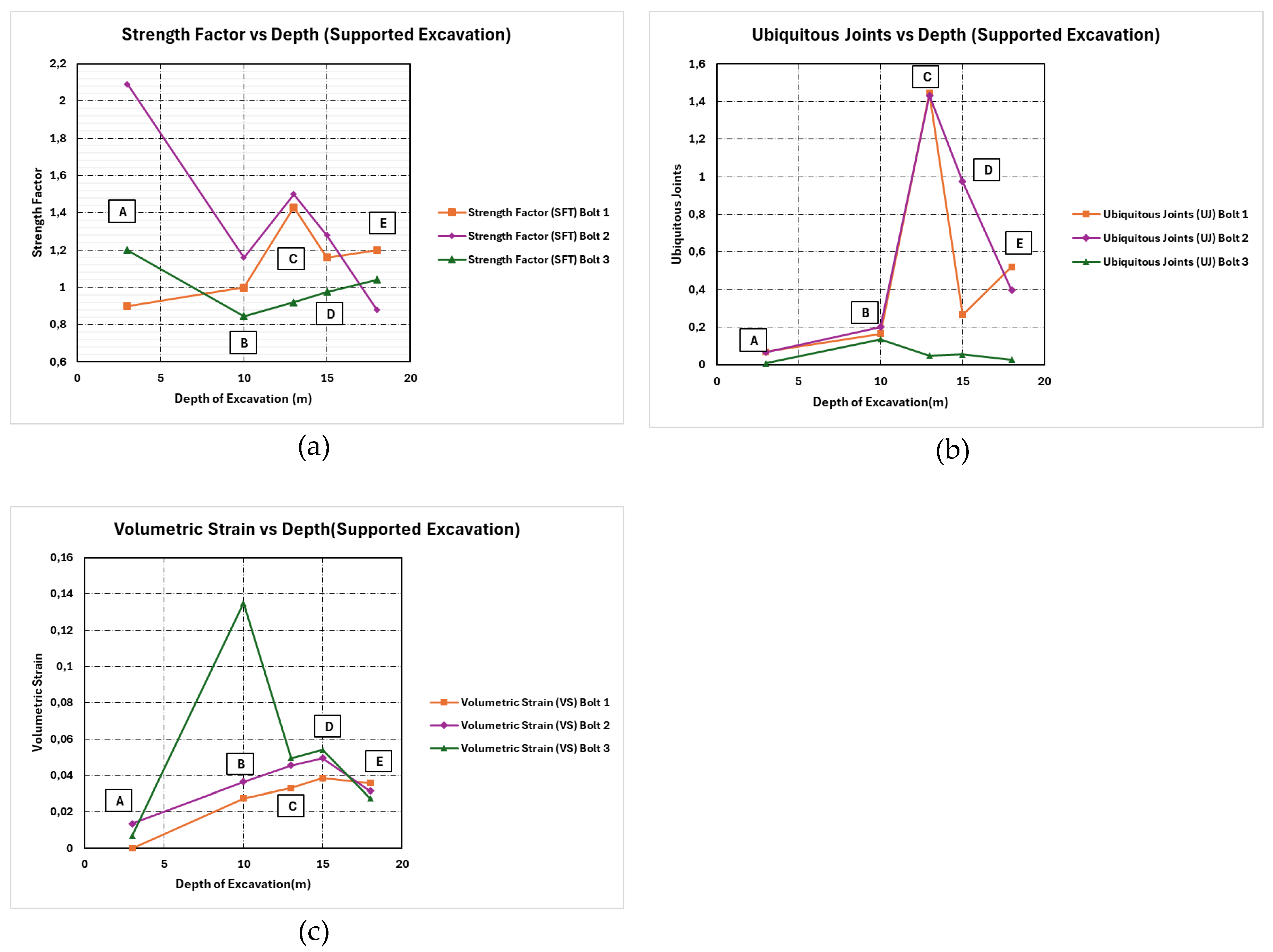

Figure 20.

Plots for surface excavations that are supported (Bolt 1) - (a) Strength Factor vs. Depth for supported excavation (Bolts 1–3). (b)Ubiquitous Joints vs. Depth for supported excavation (Bolts 1–3). (c)Volumetric Strain vs. Depth for supported excavation (Bolts 1–3).

Figure 20.

Plots for surface excavations that are supported (Bolt 1) - (a) Strength Factor vs. Depth for supported excavation (Bolts 1–3). (b)Ubiquitous Joints vs. Depth for supported excavation (Bolts 1–3). (c)Volumetric Strain vs. Depth for supported excavation (Bolts 1–3).

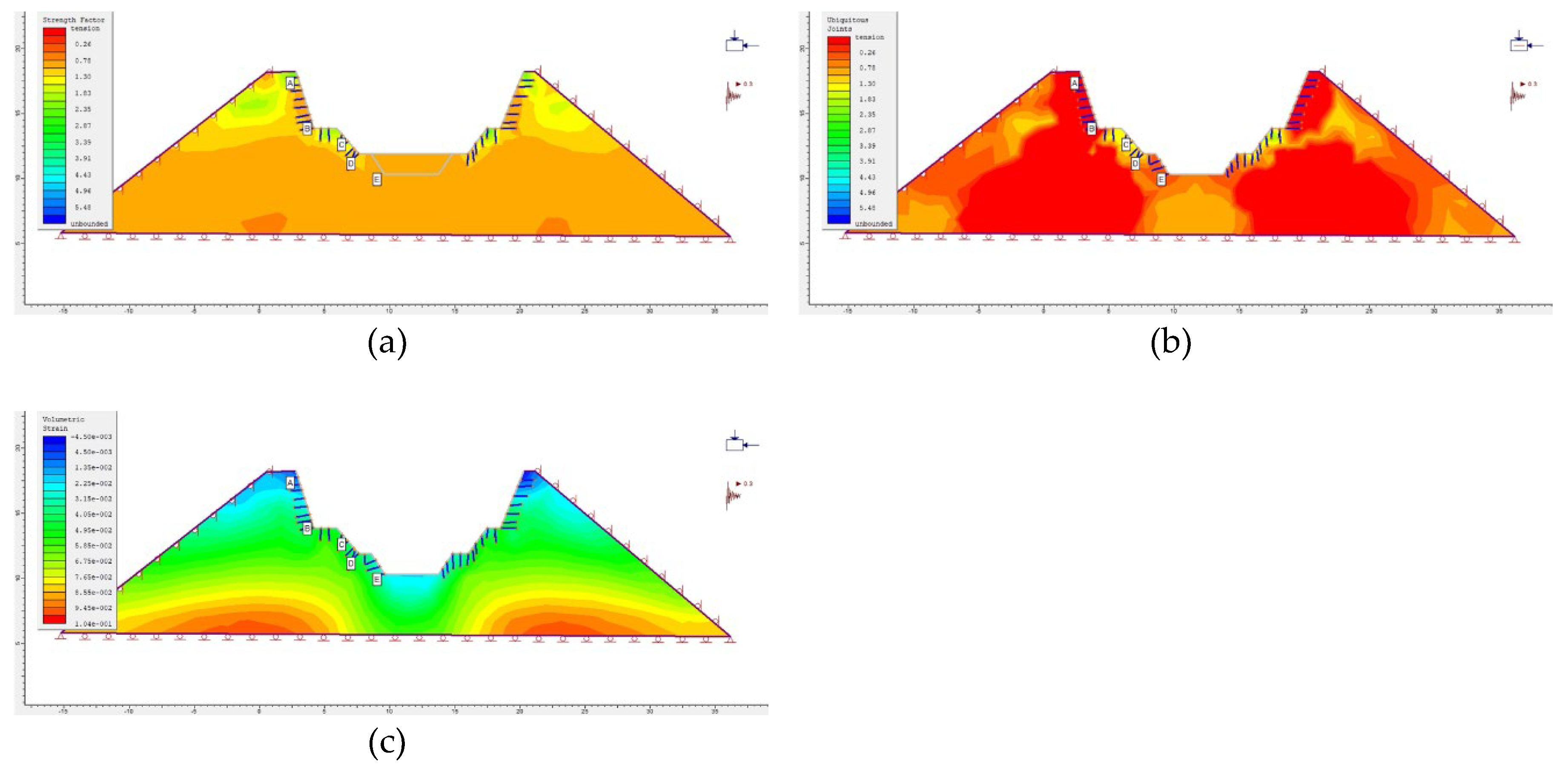

Figure 21.

Bolt 1 (a) Modelled strength factor distribution (supported excavation). (b) Modelled ubiquitous joint distribution (supported excavation). (c) Modelled volumetric strain distribution (supported excavation).

Figure 21.

Bolt 1 (a) Modelled strength factor distribution (supported excavation). (b) Modelled ubiquitous joint distribution (supported excavation). (c) Modelled volumetric strain distribution (supported excavation).

Figure 22.

Bolt 2 (a) Modelled strength factor distribution (supported excavation). (b) Modelled ubiquitous joint distribution (supported excavation). (c) Modelled volumetric strain distribution (supported excavation).

Figure 22.

Bolt 2 (a) Modelled strength factor distribution (supported excavation). (b) Modelled ubiquitous joint distribution (supported excavation). (c) Modelled volumetric strain distribution (supported excavation).

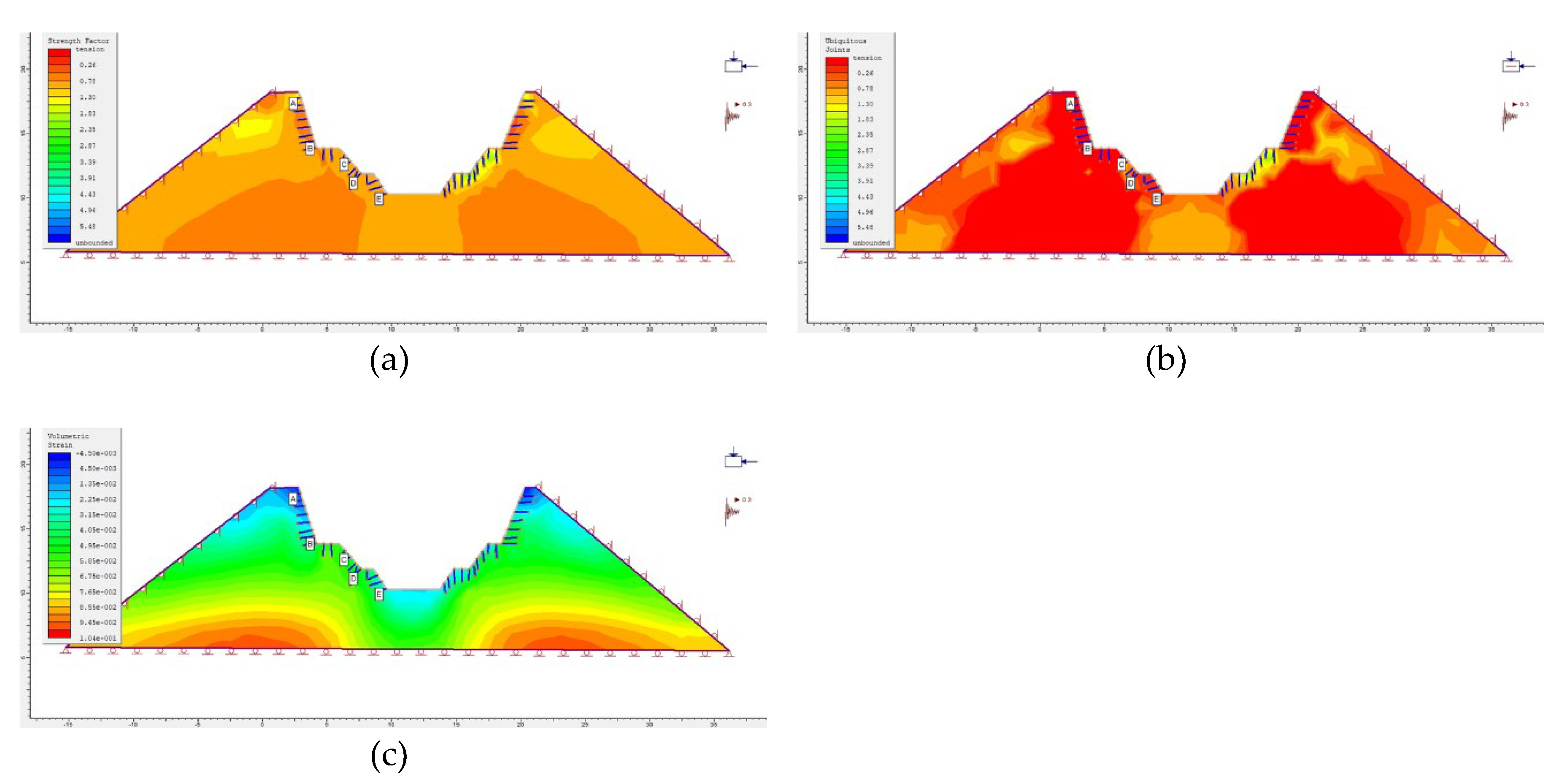

Figure 23.

Bolt 3 (a) Modelled strength factor distribution (supported excavation). (b) Modelled ubiquitous joint distribution (supported excavation). (c) Modelled volumetric strain distribution (supported excavation).

Figure 23.

Bolt 3 (a) Modelled strength factor distribution (supported excavation). (b) Modelled ubiquitous joint distribution (supported excavation). (c) Modelled volumetric strain distribution (supported excavation).

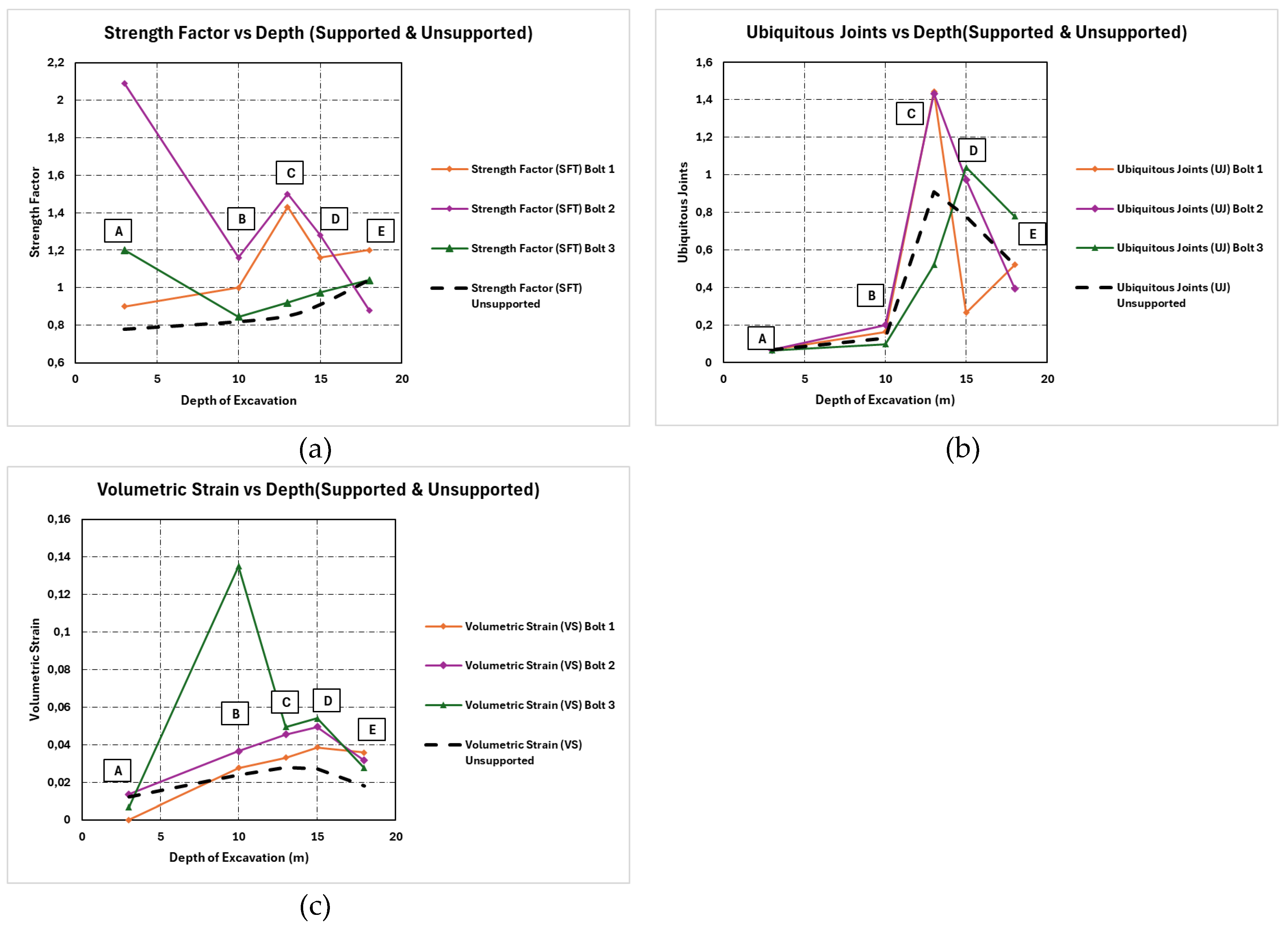

Figure 24.

Plots for surface excavations that are supported and unsupported. (a)Strength Factor vs Depth. (b) Ubiquitous Joints vs Depth. (c) Volumetric Strain vs Depth.

Figure 24.

Plots for surface excavations that are supported and unsupported. (a)Strength Factor vs Depth. (b) Ubiquitous Joints vs Depth. (c) Volumetric Strain vs Depth.

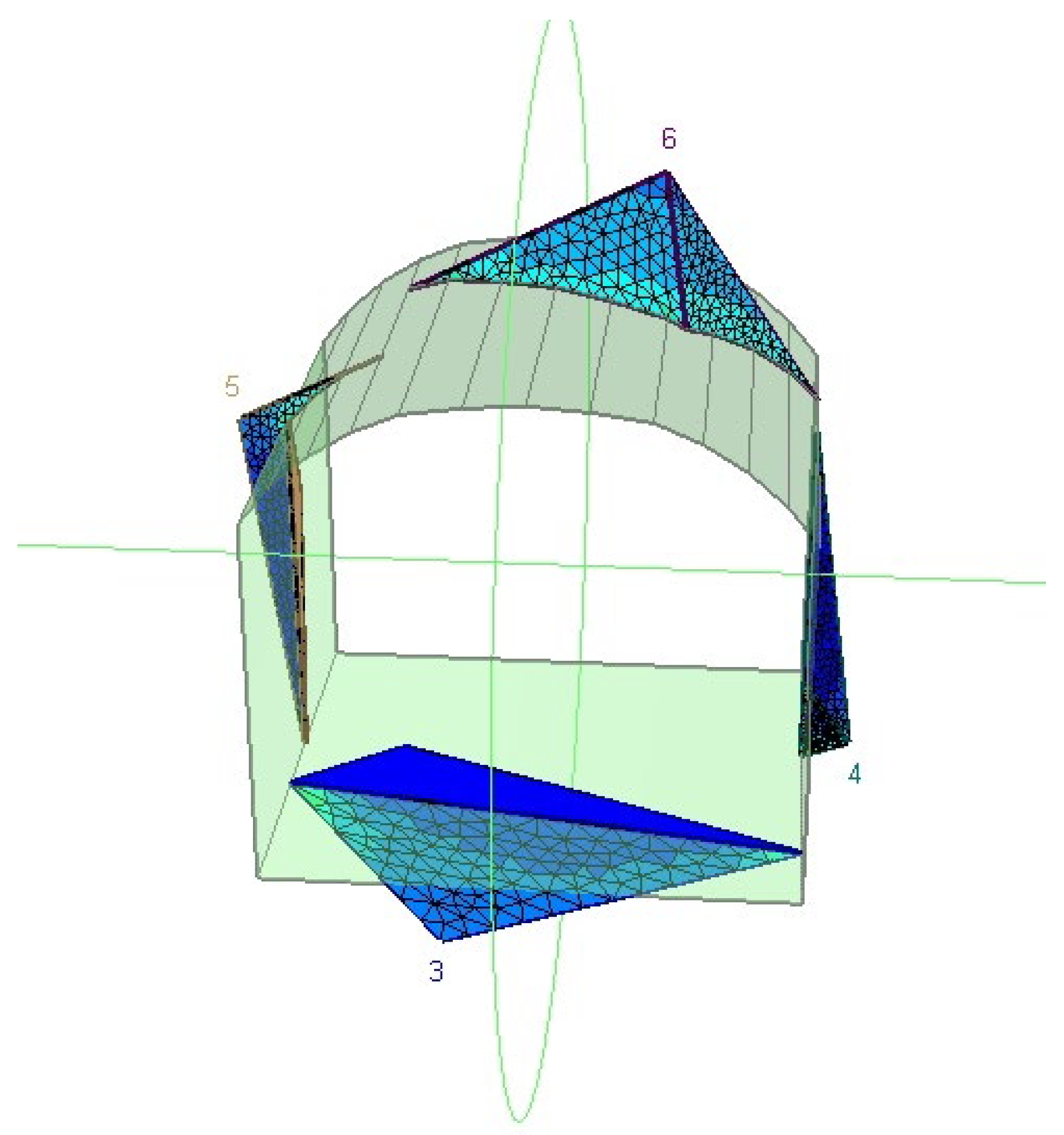

Figure 25.

Three-dimensional visualisation of wedge geometry in the unsupported tunnel scenario.

Figure 25.

Three-dimensional visualisation of wedge geometry in the unsupported tunnel scenario.

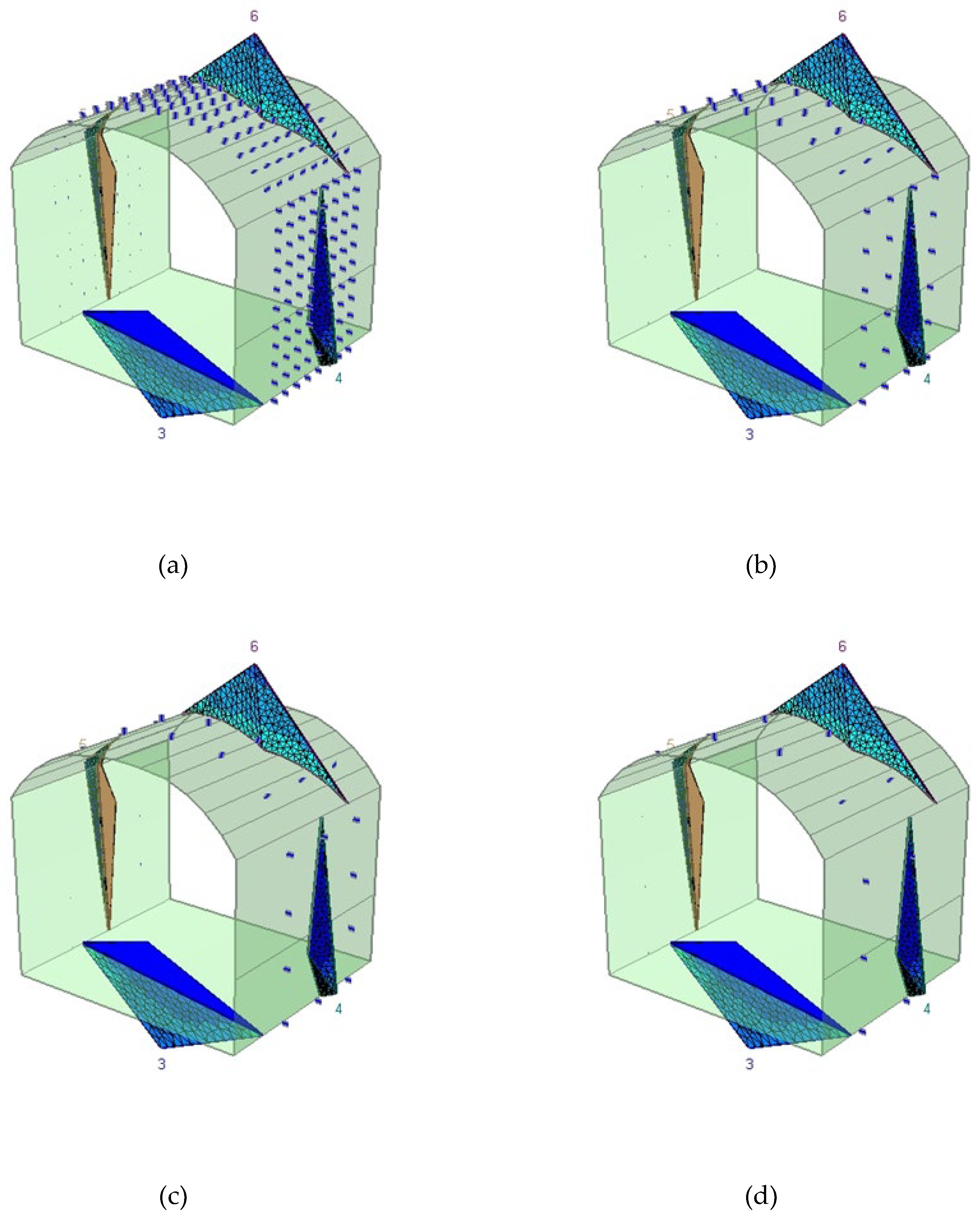

Figure 26.

Simulated tunnel response using 190 mm resin bolts at spacings of (a) 0.5 m, (b) 1.0 m, (c) 1.5 m, and (d) 2.0 m. Plots show major principal stress contours highlighting the evolution of support effectiveness and failure localisation under dynamic loading.

Figure 26.

Simulated tunnel response using 190 mm resin bolts at spacings of (a) 0.5 m, (b) 1.0 m, (c) 1.5 m, and (d) 2.0 m. Plots show major principal stress contours highlighting the evolution of support effectiveness and failure localisation under dynamic loading.

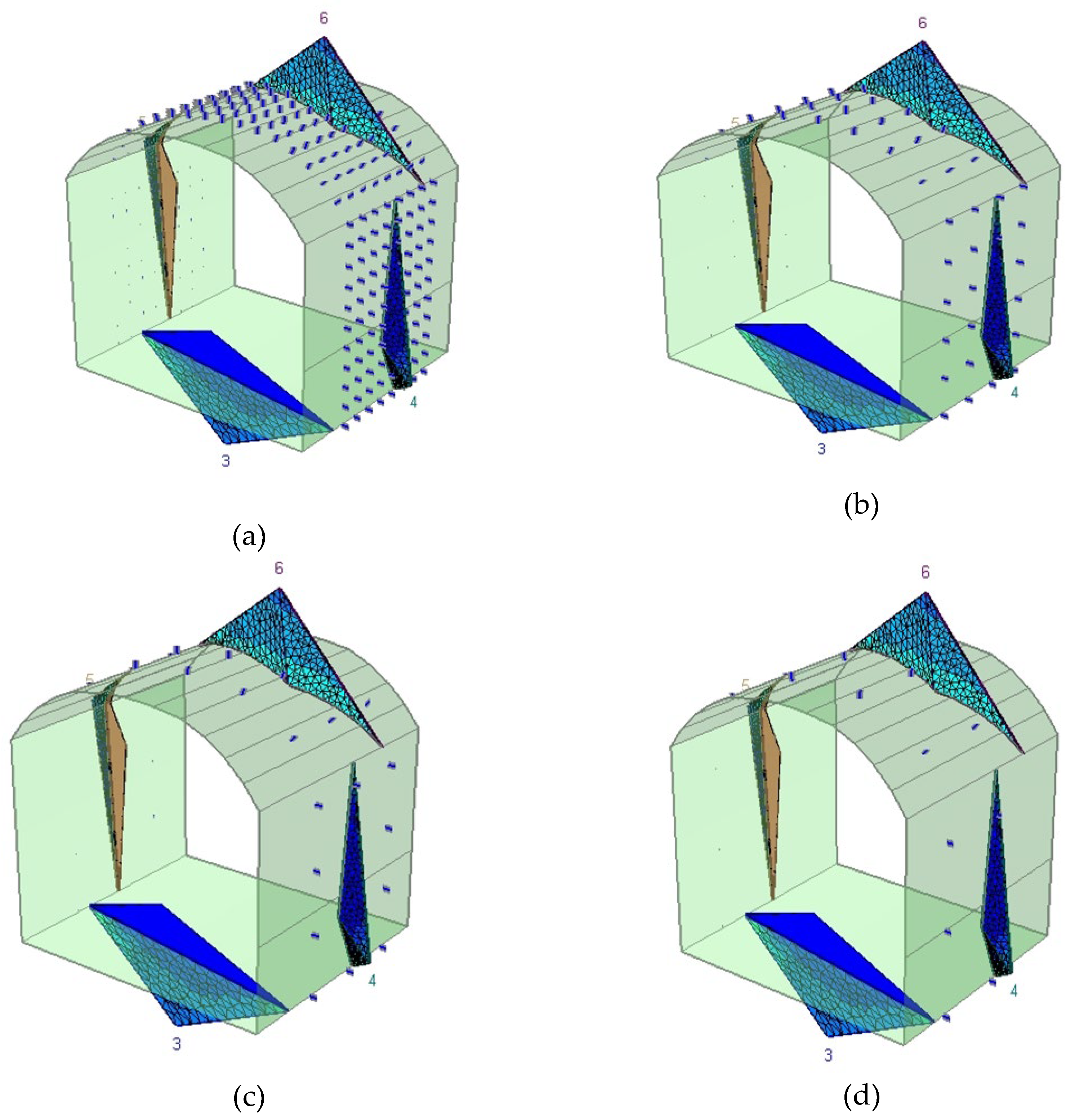

Figure 27.

Stress distribution and bolt interaction patterns for 200 mm bolts at varying spacings: (a) 0.5 m, (b) 1.0 m, (c) 1.5 m, and (d) 2.0 m. The figures illustrate progressive loss of confinement and increased stress localisation as spacing increases, particularly near the roof and wall wedges. Optimal load transfer and bolt engagement are observed at or below 1.0 m spacing.

Figure 27.

Stress distribution and bolt interaction patterns for 200 mm bolts at varying spacings: (a) 0.5 m, (b) 1.0 m, (c) 1.5 m, and (d) 2.0 m. The figures illustrate progressive loss of confinement and increased stress localisation as spacing increases, particularly near the roof and wall wedges. Optimal load transfer and bolt engagement are observed at or below 1.0 m spacing.

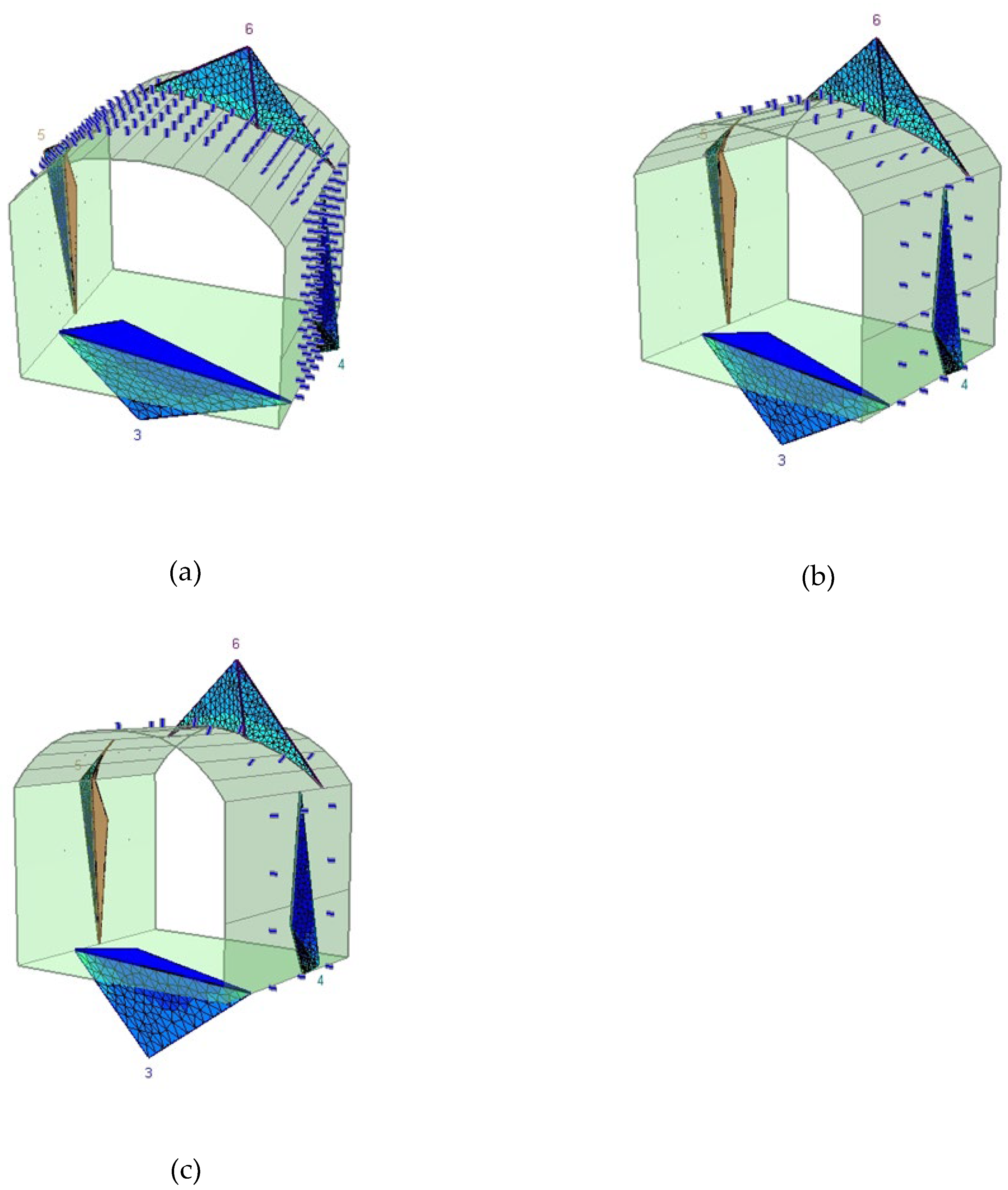

Figure 28.

Stress distribution and bolt engagement under dynamic loads for 250 mm bolts at varying spacing: (a) 0.5 m spacing, (b) 1.0 m spacing, (c) 1.5 m spacing. Increased spacing correlates with heightened stress localisation and reduced bolt efficacy, particularly near the roof and shoulder wedges.

Figure 28.

Stress distribution and bolt engagement under dynamic loads for 250 mm bolts at varying spacing: (a) 0.5 m spacing, (b) 1.0 m spacing, (c) 1.5 m spacing. Increased spacing correlates with heightened stress localisation and reduced bolt efficacy, particularly near the roof and shoulder wedges.

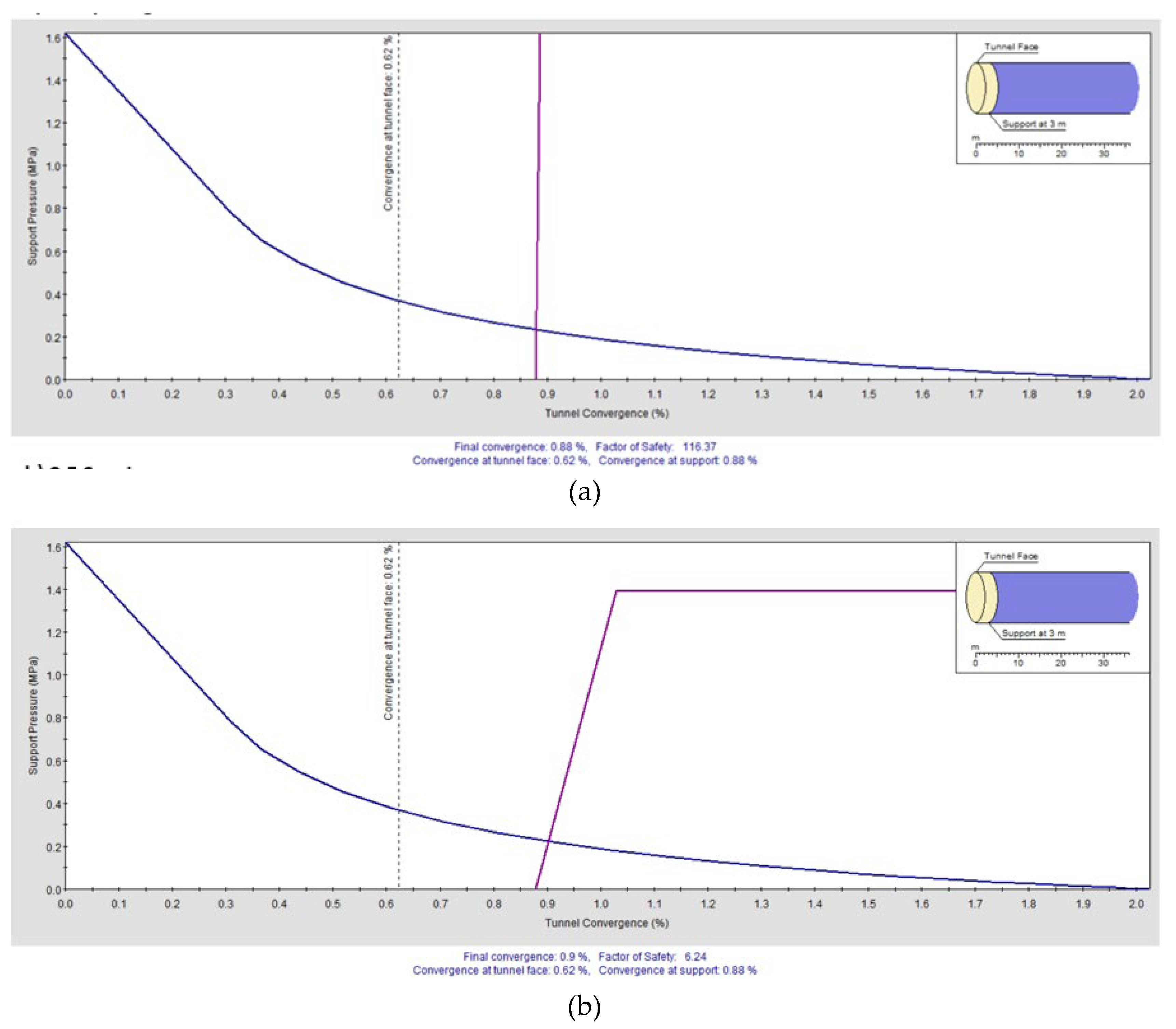

Figure 30.

Ground Reaction and Support Reaction Curves for Varying Bolt Spacings (a) 0.1 m and (b) 0.5 m.

Figure 30.

Ground Reaction and Support Reaction Curves for Varying Bolt Spacings (a) 0.1 m and (b) 0.5 m.

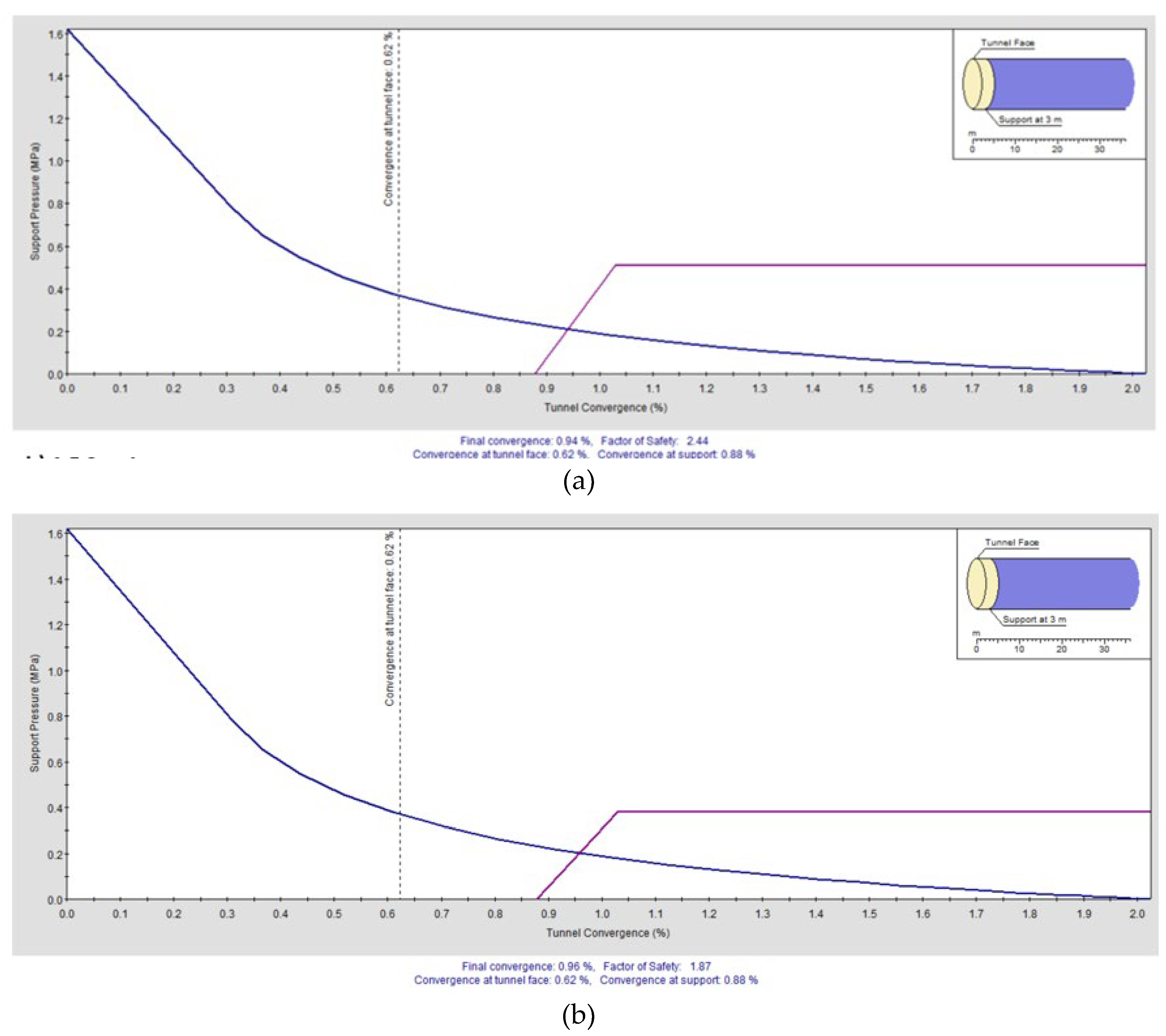

Figure 31.

Ground Reaction and Support Reaction Curves for Varying Bolt Spacings (a) 1.0 m and (b) 1.5 m.

Figure 31.

Ground Reaction and Support Reaction Curves for Varying Bolt Spacings (a) 1.0 m and (b) 1.5 m.

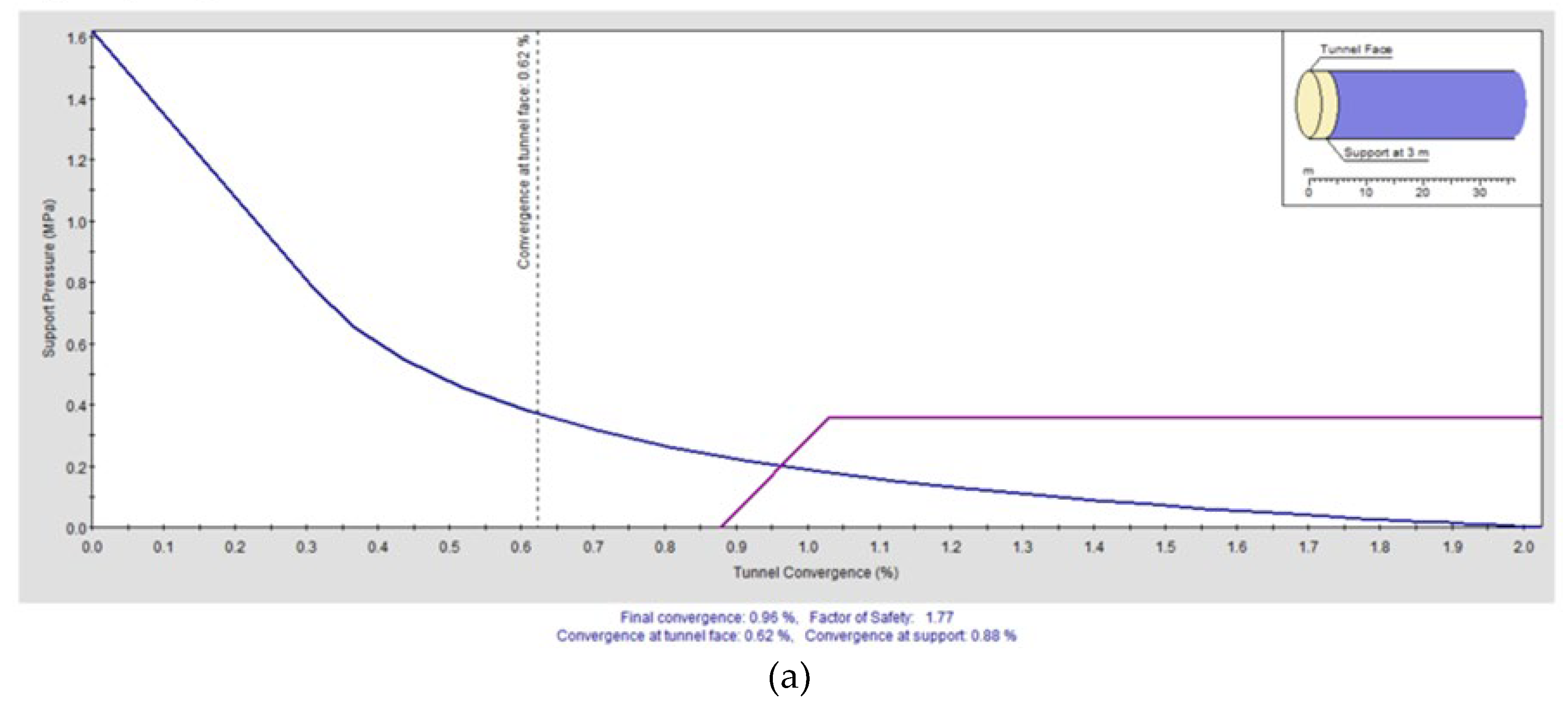

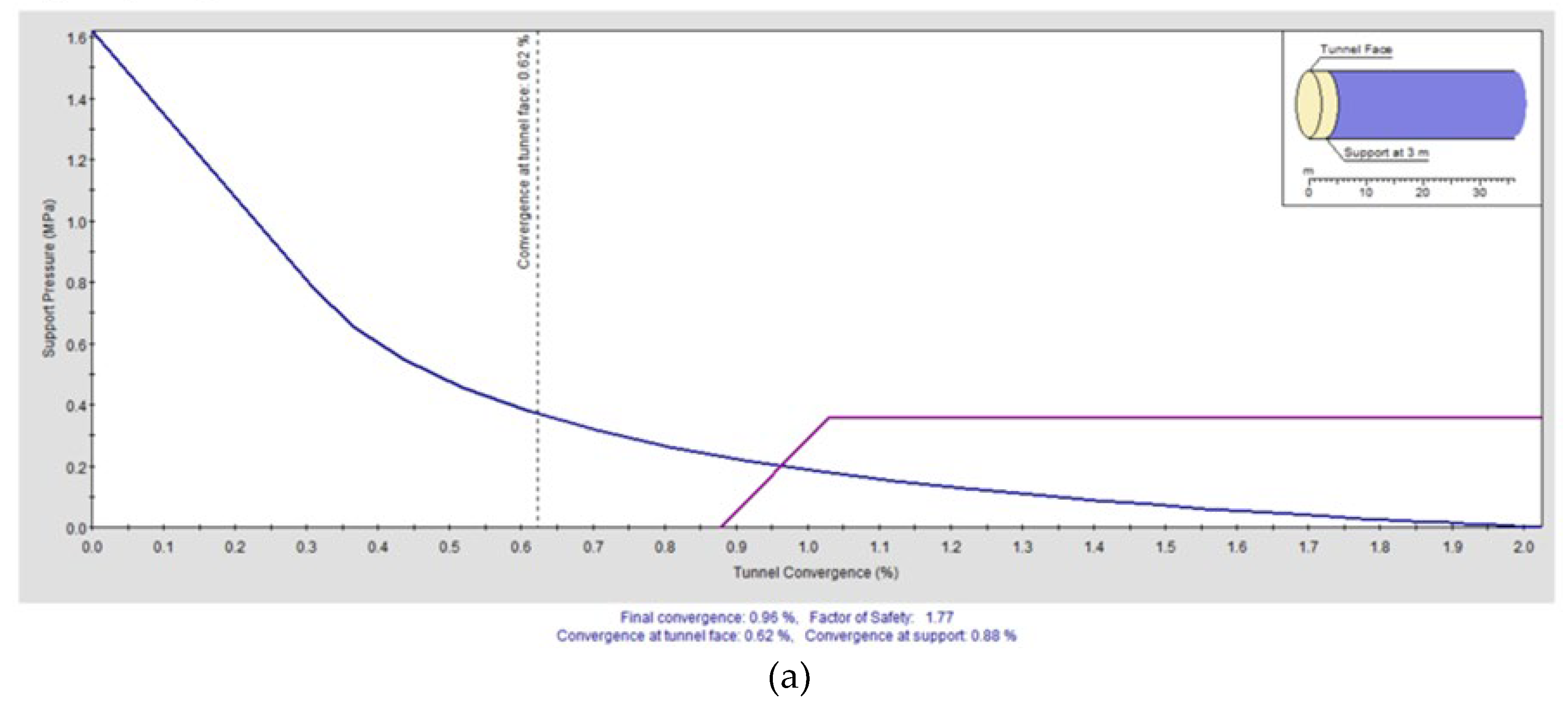

Figure 32.

Ground Reaction and Support Reaction Curves for Varying Bolt Spacings (a) 0.1 m and (b) 0.5 m.

Figure 32.

Ground Reaction and Support Reaction Curves for Varying Bolt Spacings (a) 0.1 m and (b) 0.5 m.

Table 1.

Key parameters for static field testing at Videx Mining Facility.

Table 1.

Key parameters for static field testing at Videx Mining Facility.

| Parameter |

Value/Range |

| Rock condition |

Fractured / Intact |

| Hole diameter |

18mm, 24mm |

| Bolt Diameters |

16mm, 20mm |

| Bolt Lengths |

160mm, 245mm |

| Number of bolts |

15 |

| Curing time |

12–24 hours |

| Loading rate |

2 mm/min |

| Resin type |

Two-part (standard vinyl ester and epoxy) |

Table 2.

Input parameters for fully bonded adhesive bolts in Phase 2 modelling.

Table 2.

Input parameters for fully bonded adhesive bolts in Phase 2 modelling.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Bolt Type |

Fully bonded |

| Bolt Length (m) |

2.4 |

| Bolt Diameter (mm) |

20 |

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) |

210 |

| Bond Strength (MPa) |

1.3 |

| Bolt Spacing (m) |

2.0 |

Table 3.

Material properties used in Phase 2 simulation.

Table 3.

Material properties used in Phase 2 simulation.

| Material |

Young’s Modulus (GPa) |

Poisson’s Ratio |

UCS (MPa) |

Bond Strength (MPa) |

Density (kg/m³) |

| Intact Rock |

35 |

0.25 |

80 |

— |

2700 |

| Fractured Rock |

18 |

0.28 |

20 |

— |

2650 |

| Grout/Adhesive |

14 |

0.22 |

12 |

1.3 |

2000 |

| Steel (bolt) |

210 |

0.30 |

— |

— |

7850 |

Table 4.

Input parameters used for Unwedge simulation.

Table 4.

Input parameters used for Unwedge simulation.

| Parameter |

Value |

| Bench/Slope Height (m) |

[e.g., 10.0] |

| Bench Width (m) |

[e.g., 8.0] |

| Slope Angle (°) |

[Field-measured] |

| Joint 1 Dip / Direction |

70° / 37° |

| Joint 2 Dip / Direction |

85° / 101° |

| Joint 3 Dip / Direction |

48° / 262° |

| Bolt Spacing (in/out plane) |

2.0 m × 2.0 m |

| Principal Stress σ₁ (MPa) |

89 |

| σ₂ / σ₃ (MPa) |

47 / 27 |

Table 5.

Summary of Peak Load Results.

Table 5.

Summary of Peak Load Results.

| Resin Type |

Bolt Size (mm) |

Test Type |

Mean Peak Load (kN) |

Std. Dev. (kN) |

COV (%) |

| Vinyl ester resin – 16 mm bolt – length 160mm |

16 |

Lab |

26.39 |

12.69 |

48.08 |

| Vinyl ester resin – 20 mm bolt – length 245mm |

20 |

Lab |

65.00 |

19.86 |

30.55 |

| Epoxy resin – 16 mm bolt – length 160mm |

16 |

Lab |

56.43 |

19.18 |

33.99 |

| Epoxy resin – 20 mm bolt – length 245mm |

20 |

Lab |

6.97 |

3.55 |

50.94 |

| Vinyl ester resin – 16 mm bolt – length 160mm |

20 |

In-situ |

103.67 |

43.67 |

42.12 |

| Vinyl ester resin – 24 mm bolt – length 210mm |

24 |

In-situ |

98.90 |

35.02 |

35.41 |

| Epoxy resin – 20 mm bolt – length – 350mm |

20 |

In-situ |

118.17 |

37.63 |

31.84 |

| Vinyl ester resin – 10 mm bolt – length 90mm |

10 |

In-situ |

8.12 |

5.40 |

66.51 |

Table 6.

Tensile and Shear Capacities for each anchor configuration.

Table 6.

Tensile and Shear Capacities for each anchor configuration.

| Anchor system |

Diameter × embedment (mm) |

Day 5 tensile (kN) |

Day 10 tensile (kN) |

Day 15 tensile (kN) |

Day 5 shear (kN) |

Day 10 shear (kN) |

Day 15 shear (kN) |

| Epoxy |

16 × 160 |

43 |

61 |

72 |

36 |

51 |

60 |

| |

20 × 245 |

65 |

92 |

108 |

54 |

77 |

90 |

| Standard Vinyl-ester |

16 × 160 |

51 |

63 |

68 |

43 |

52 |

57 |

| |

20 × 245 |

77 |

94 |

102 |

64 |

78 |

85 |

| High-bond Vinyl-ester) |

16 × 125 |

44 |

57 |

62 |

36 |

47 |

52 |

| |

20 × 210 |

69 |

88 |

97 |

57 |

73 |

81 |

Table 7.

Numerical outputs at selected points during Stage 3 (Unsupported Surface Excavation).

Table 7.

Numerical outputs at selected points during Stage 3 (Unsupported Surface Excavation).

| Point |

Strength Factor |

Ubiquitous Joints |

Volumetric Strain |

Depth (m) |

| A |

0.78 |

0.068 |

0.012 |

3 |

| B |

0.82 |

0.13 |

0.024 |

10 |

| C |

0.85 |

0.91 |

0.028 |

13 |

| D |

0.91 |

0.78 |

0.027 |

15 |

| E |

1.04 |

0.52 |

0.018 |

18 |

Table 8.

Summary of numerical outputs for supported excavation at key control points.

Table 8.

Summary of numerical outputs for supported excavation at key control points.

| STAGE 3 |

|---|

| Bolt No. |

Bolt Type & Size |

Load Capacity |

Point |

Strength Factor |

Ubiquitous Joints |

Volumetric Strain |

Depth (m) |

| BOLT 1 |

Epoxy Resin, Length 245mm, Diameter 20mm |

55,000 kN |

A |

0,9 |

0,0685 |

0 |

3 |

| B |

1 |

0,1637 |

0,0275 |

10 |

| C |

1,43 |

1,4436 |

0,033 |

13 |

| D |

1,16 |

0,265 |

0,0385 |

15 |

| E |

1,2 |

0,52 |

0,03575 |

18 |

| BOLT 2 |

Epoxy Resin, Length 200mm, Diameter 20mm |

35,000 kN |

Point |

Strength Factor |

Ubiquitous Joints |

Volumetric Strain |

Depth (m) |

| A |

2,09 |

0,0675 |

0,0135 |

3 |

| B |

1,16 |

0,2 |

0,0365 |

10 |

| C |

1,5 |

1,4325 |

0,0455 |

13 |

| D |

1,28 |

0,975 |

0,0495 |

15 |

| E |

0,88 |

0,395 |

0,0315 |

18 |

| BOLT 3 |

Epoxy Resin, Length 190mm, Diameter 20mm |

25,000 kN |

Point |

Strength Factor |

Ubiquitous Joints |

Volumetric Strain |

Depth (m) |

| A |

1,2 |

0,065 |

0,00675 |

3 |

| B |

0,845 |

0,0975 |

0,135 |

10 |

| C |

0,92 |

0,52 |

0,0495 |

13 |

| D |

0,975 |

1,04 |

0,054 |

15 |

| E |

1,04 |

0,78 |

0,0275 |

18 |

Table 9.

Calculated Factor of Safety and Weights for Identified Wedges (Unsupported Tunnel Case).

Table 9.

Calculated Factor of Safety and Weights for Identified Wedges (Unsupported Tunnel Case).

| Wedge ID |

Location |

Factor of Safety (FS) |

Weight (tonnes) |

| 4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

4.60 |

0.79 |

| 5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1.69 |

0.99 |

| 6 |

Roof wedge |

2.64 |

3.10 |

Table 10.

Variation in Factor of Safety (FoS) and Wedge Weight for 190 mm Resin-Grouted Bolts at Different Spacings under Tunnel Support Conditions.

Table 10.

Variation in Factor of Safety (FoS) and Wedge Weight for 190 mm Resin-Grouted Bolts at Different Spacings under Tunnel Support Conditions.

| Bolt length |

Bolt spacing |

Wedge ID |

Location |

Factor-of-Safety (FS) |

Weight (t) |

| 190 mm |

0.10 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

1 258,48 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

74,787 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

50,019 |

3,104 |

| 190 mm |

0.50 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

35,783 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,741 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,676 |

3,104 |

| 190 mm |

1.00 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

14,446 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,705 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,65 |

3,104 |

| 190 mm |

1.50 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

25,936 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,691 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,643 |

3,104 |

| 190 mm |

2.00 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

14,446 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,691 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,643 |

3,104 |

Table 11.

Variation in Factor of Safety (FoS) and Wedge Weight for 200 mm Resin-Grouted Bolts at Different Spacings under Tunnel Support Conditions.

Table 11.

Variation in Factor of Safety (FoS) and Wedge Weight for 200 mm Resin-Grouted Bolts at Different Spacings under Tunnel Support Conditions.

| Bolt length |

Bolt spacing |

Wedge ID |

Location |

Factor-of-Safety (FS) |

Weight (t) |

| 200 mm |

0.10 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

1 385,78 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

82,088 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

55,613 |

3,104 |

| 200 mm |

0.50 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

39,01 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,747 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,679 |

3,104 |

| 200 mm |

1.00 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

16,059 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,708 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,652 |

3,104 |

| 200 mm |

1.50 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

27,549 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,691 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,643 |

3,104 |

| 200 mm |

2.00 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

16,059 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,691 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,643 |

3,104 |

Table 12.

Variation in Factor of Safety (FoS) and Wedge Weight for 250 mm Resin-Grouted Bolts at Different Spacings under Tunnel Support Conditions.

Table 12.

Variation in Factor of Safety (FoS) and Wedge Weight for 250 mm Resin-Grouted Bolts at Different Spacings under Tunnel Support Conditions.

| Bolt length |

Bolt spacing |

Wedge ID |

Location |

Factor-of-Safety (FS) |

Weight (t) |

| 250 mm |

0.10 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

2 095,00 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

124,336 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

87,37 |

3,104 |

| 250 mm |

0.50 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

39,01 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,747 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,679 |

3,104 |

| 250 mm |

1.00 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

24,13 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,723 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,66 |

3,104 |

| 250 mm |

1.50 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

27,549 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

1,691 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

2,643 |

3,104 |

| 250 mm |

2.00 m |

4 |

Lower-Right wedge |

17,059 |

0,787 |

| |

|

5 |

Upper-Left wedge |

2,691 |

0,985 |

| |

|

6 |

Roof wedge |

3,643 |

3,104 |