Submitted:

20 August 2025

Posted:

21 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

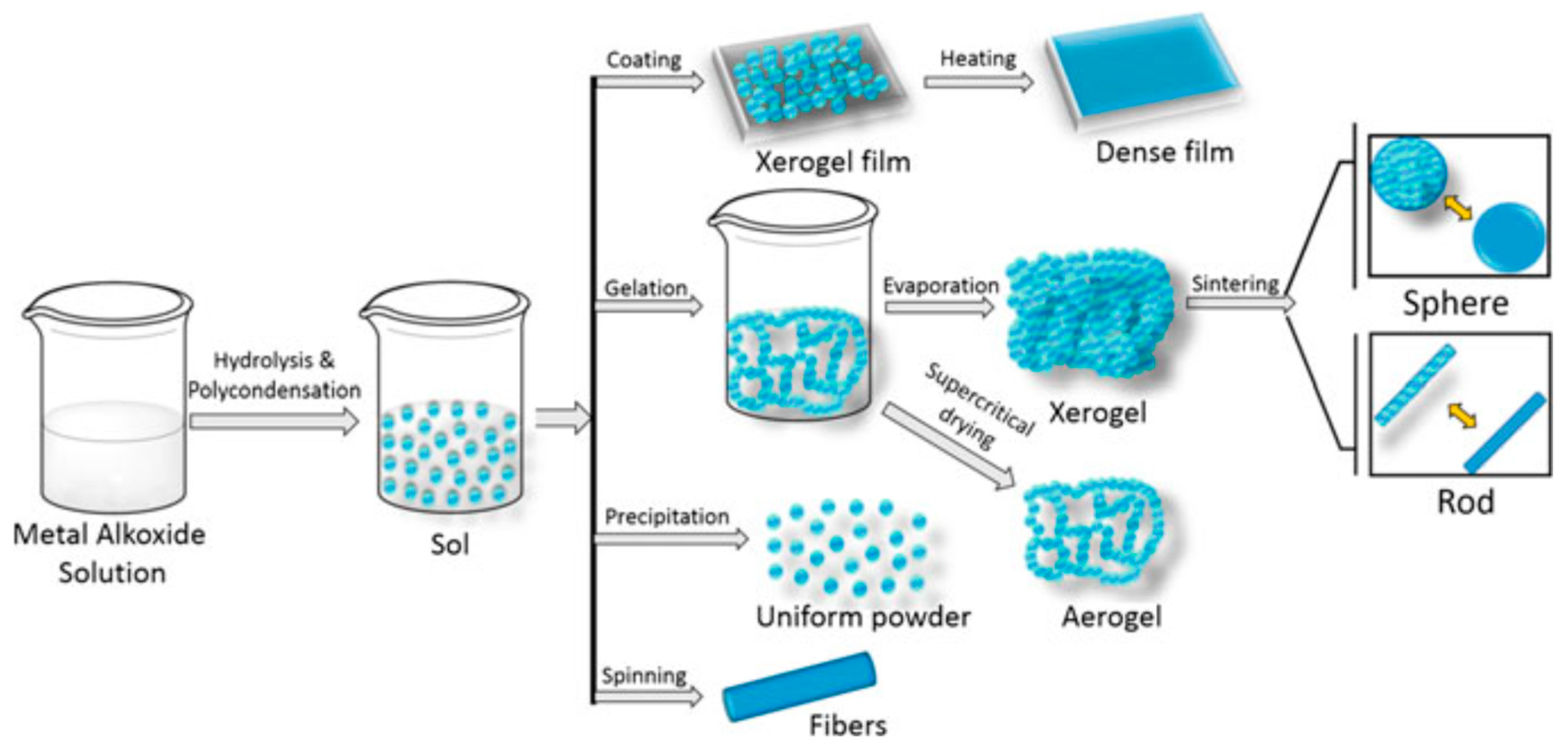

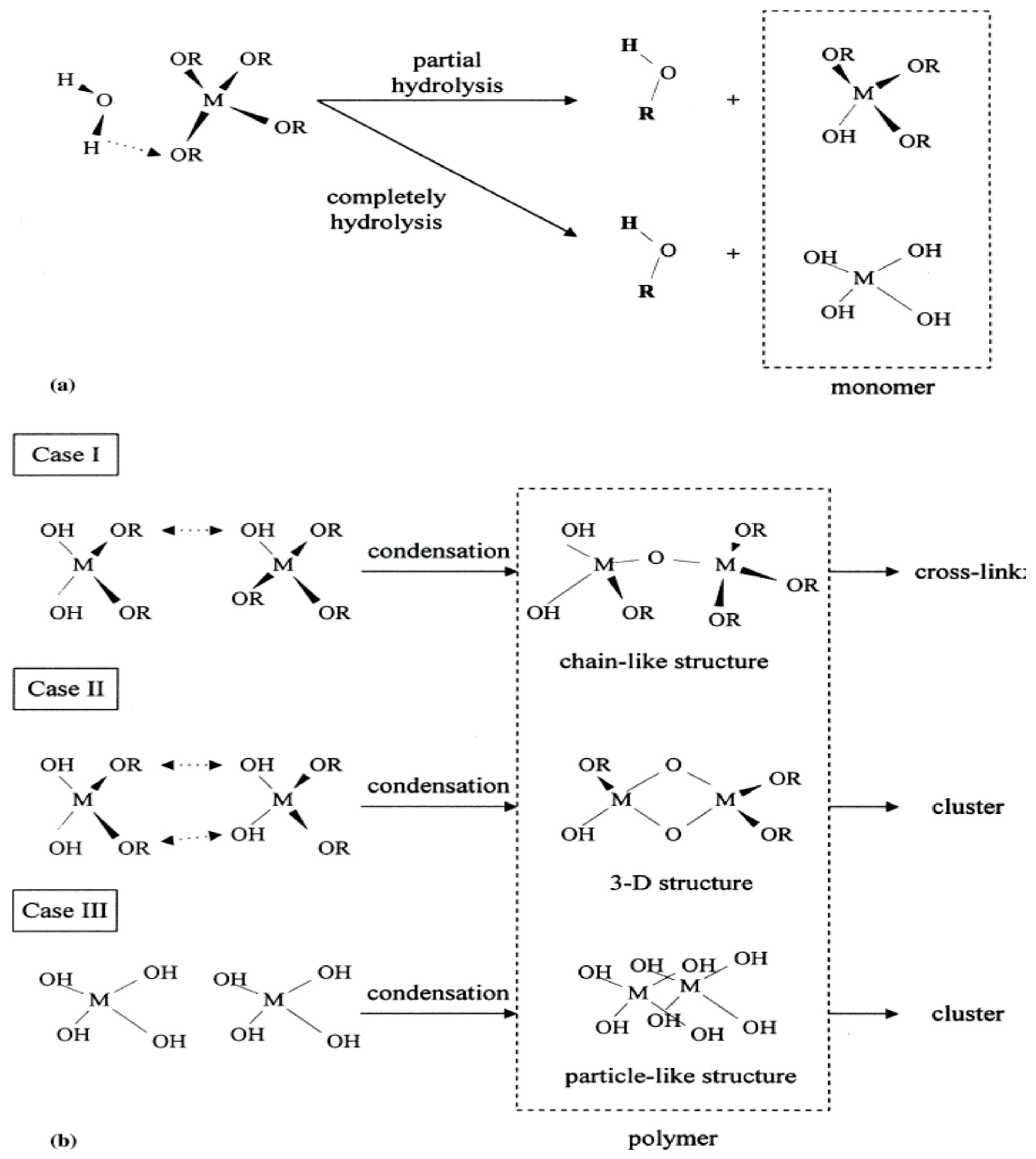

Sol-Gel Method for TiO2 Synthesis

| Ti(OR)4 + 4H2O → Ti (OH)4 + (ROH)4 | 1. Hydrolysis |

| Ti(OH)4 → TiO2 + 2H2O | 2. Condensation |

Factors Affecting Particle Properties of TiO2 NPs

Uses of TiO2 NPs in Biology

Conclusion

References

- Chen, X. and S.S. Mao, Titanium dioxide nanomaterials: synthesis, properties, modifications, and applications. Chemical reviews, 2007. 107(7): p. 2891-2959. [CrossRef]

- Akinnawo, S., Synthesis, modification, applications, and challenges of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Research Journal of Nanoscience and Engineering, 2019. 3(4): p. 10-22. [CrossRef]

- Malekshahi Byranvand, M., et al., A review on synthesis of nano-TiO2 via different methods. Journal of nanostructures, 2013. 3(1): p. 1-9.

- Zhao, B., et al., Brookite TiO2 nanoflowers. Chemical communications, 2009(34): p. 5115-5117. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H., et al., Synthesis of high-quality brookite TiO2 single-crystalline nanosheets with specific facets exposed: tuning catalysts from inert to highly reactive. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2012. 134(20): p. 8328-8331. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohno, Y., et al., Pseudo-cube shaped brookite (TiO2) nanocrystals synthesized by an oleate-modified hydrothermal growth method. Crystal growth & design, 2011. 11(11): p. 4831-4836.

- Raj, K. and B. Viswanathan, Effect of surface area, pore volume and particle size of P25 titania on the phase transformation of anatase to rutile. 2009.

- Liu, G., et al., The role of crystal phase in determining the photocatalytic activity of nitrogen-doped TiO2. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 2009. 329(2): p. 331-338. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, M., A.Z. Abdullah, and M. Rafatullah, Recent development in the green synthesis of titanium dioxide nanoparticles using plant-based biomolecules for environmental and antimicrobial applications. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2021. 98: p. 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Lazar, M.A., S. Varghese, and S.S. Nair, Photocatalytic water treatment by titanium dioxide: recent updates. Catalysts, 2012. 2(4): p. 572-601. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., et al., Effect of water composition on TiO2 photocatalytic removal of endocrine disrupting compounds (EDCs) and estrogenic activity from secondary effluent. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2012. 215: p. 252-258. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dastjerdi, R. and M. Montazer, A review on the application of inorganic nano-structured materials in the modification of textiles: focus on anti-microbial properties. Colloids and surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 2010. 79(1): p. 5-18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubacka, A., et al., Understanding the antimicrobial mechanism of TiO2-based nanocomposite films in a pathogenic bacterium. Scientific Reports, 2014. 4(1): p. 4134. [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubbu, G.D., et al., Folate targeted PEGylated titanium dioxide nanoparticles as a nanocarrier for targeted paclitaxel drug delivery. Advanced Powder Technology, 2013. 24(6): p. 947-954. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Garcia, M. and J. Rodgriguez, Metal oxide nanoparticles. 2007, Brookhaven National Lab. (BNL), Upton, NY (United States).

- Xu, P., et al., A new strategy for TiO 2 whiskers mediated multi-mode cancer treatment. Nanoscale research letters, 2015. 10: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Comune, M., et al., Antimicrobial and pro-angiogenic properties of soluble and nanoparticle-immobilized LL37 peptides. Biomaterials Science, 2021. 9(24): p. 8153-8159. [CrossRef]

- Liu, E., et al., Cisplatin loaded hyaluronic acid modified TiO 2 nanoparticles for neoadjuvant chemotherapy of ovarian cancer. Journal of Nanomaterials, 2015. 16(1): p. 275-275.

- Abushowmi, T.H., et al., Comparative effect of glass fiber and nano-filler addition on denture repair strength. Journal of Prosthodontics, 2020. 29(3): p. 261-268. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., et al., Nanoparticle-reinforced resin-based dental composites. Journal of Dentistry, 2008. 36(6): p. 450-455. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkubo, C., S. Hanatani, and T. Hosoi, Present status of titanium removable dentures–a review of the literature. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 2008. 35(9): p. 706-714. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, F., TiO_2 photocatalysis fundamentals and applications. A Revolution in cleaning technology, 1999: p. 14-21.

- Maneerat, C. and Y. Hayata, Antifungal activity of TiO2 photocatalysis against Penicillium expansum in vitro and fruit tests. International journal of food microbiology, 2006. 107(2): p. 99-103. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jawad, A.A., et al., Synthesis Methods and Applications of TiO2 based Nanomaterials. Al-Nahrain Journal of Science, 2022. 25(4): p. 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, A.L. and M. Manefield, The role of lipids in activated sludge floc formation. AIMS Environmental Science, 2015. 2(2): p. 122-133. [CrossRef]

- Hong, I., VOCs degradation performance of TiO2 aerogel photocatalyst prepared in SCF drying. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 2006. 12(6): p. 918-925.

- Zhang, Y., et al., Mullite fibers prepared by sol–gel method using polyvinyl butyral. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 2009. 29(6): p. 1101-1107. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-S., et al., Synthesis of nanocrystalline TiO2 in toluene by a solvothermal route. Journal of Crystal Growth, 2003. 254(3-4): p. 405-410. [CrossRef]

- Burda, C., et al., Chemistry and properties of nanocrystals of different shapes. Chemical reviews, 2005. 105(4): p. 1025-1102. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.G. and K.K. Rao, Polymorphic phase transition among the titania crystal structures using a solution-based approach: from precursor chemistry to nucleation process. Nanoscale, 2014. 6(20): p. 11574-11632. [CrossRef]

- Liu, A., et al., Low-temperature preparation of nanocrystalline TiO2 photocatalyst with a very large specific surface area. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2006. 99(1): p. 131-134. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.-S. and Y.-W. Chen, Preparation of titania particles by thermal hydrolysis of TiCl4 in n-propanol solution. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 2003. 78(3): p. 739-745. [CrossRef]

- Vickers, N.J., Animal communication: when I’m calling you, will you answer too? Current Biology, 2017. 27(14): p. R713-R715. [CrossRef]

- Ullattil, S.G. and P. Periyat, Sol-gel synthesis of titanium dioxide. Sol-Gel Materials for Energy, Environment and Electronic Applications, 2017: p. 271-283.

- Schubert, U., Chemical modification of titanium alkoxides for sol–gel processing. Journal of Materials Chemistry, 2005. 15(35-36): p. 3701-3715. [CrossRef]

- Periyat, P., et al., Aqueous colloidal sol–gel route to synthesize nanosized ceria-doped titania having high surface area and increased anatase phase stability. Journal of sol-gel science and technology, 2007. 43: p. 299-304. [CrossRef]

- Baiju, K., et al., Enhanced photoactivity of neodymium-doped mesoporous titania synthesized through aqueous sol–gel method. Journal of sol-gel science and technology, 2007. 43: p. 283-290. [CrossRef]

- Periyat, P., P. Saeed, and S. Ullattil, Anatase titania nanorods by pseudo-inorganic templating. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing, 2015. 31: p. 658-665. [CrossRef]

- Varma, H.K., et al., Characteristics of alumina powders prepared by spray-drying of Boehmite Sol. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 1994. 77(6): p. 1597-1600. [CrossRef]

- Jahromi, H.S., et al., Effects of pH and polyethylene glycol on surface morphology of TiO2 thin film. Surface and Coatings Technology, 2009. 203(14): p. 1991-1996. [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T., K. Okada, and H. Itoh, Synthetic of uniform spindle-type titania particles by the gel–sol method. 1997, Elsevier. p. 140-143.

- Chai, L.-y., et al., Effect of surfactants on preparation of nanometer TiO2 by pyrohydrolysis. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China, 2007. 17(1): p. 176-180. [CrossRef]

- Vorkapic, D. and T. Matsoukas, Effect of temperature and alcohols in the preparation of titania nanoparticles from alkoxides. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 1998. 81(11): p. 2815-2820. [CrossRef]

- Matijević, E., M. Budnik, and L. Meites, Preparation, and mechanism of formation of titanium dioxide hydrosols of narrow size distribution. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 1977. 61(2): p. 302-311. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.D. and J. Jeong, The effects of temperature on particle size in the gas-phase production of TiO2. Aerosol Science and Technology, 1995. 23(4): p. 553-560. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S., et al., A new observation on the phase transformation of TiO2 nanoparticles produced by a CVD method. Aerosol science and technology, 2005. 39(2): p. 104-112. [CrossRef]

- Schmuki, P., et al. TiO2 Nanotube Diameter Directs Cell Fate. in ECS Meeting Abstracts. 2007. IOP Publishing.

- Xu, Y., W. Zheng, and W. Liu, Enhanced photocatalytic activity of supported TiO2: dispersing effect of SiO2. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology A: Chemistry, 1999. 122(1): p. 57-60. [CrossRef]

- Nyamukamba, P., et al., Synthetic methods for titanium dioxide nanoparticles: a review. Titanium dioxide-material for a sustainable environment, 2018. 8: p. 151-175.

- Nyamukamba, P., C. Greyling, and L. Tichagwa, Preparation of photocatalytic TiO2 nanoparticles immobilized on carbon nanofibres for water purification. 2011, University of Fort Hare.

- Yu, H.-F. and S.-M. Wang, Effects of water content and pH on gel-derived TiO2–SiO2. Journal of non-crystalline solids, 2000. 261(1-3): p. 260-267. [CrossRef]

- Barringer, E.A. and H.K. Bowen, Formation, packing, and sintering of monodisperse TiO2 powders. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 1982. 65(12): p. C-199-C-201. [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, K.P., et al., Microbicidal activity of TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized by sol–gel method. IET nanobiotechnology, 2016. 10(2): p. 81-86. [CrossRef]

- Sugapriya, S., R. Sriram, and S. Lakshmi, Effect of annealing on TiO2 nanoparticles. Optik, 2013. 124(21): p. 4971-4975. [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, S., et al. Investigation of the role of pH on structural and morphological properties of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. in IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. 2020. IOP Publishing.

- Santhi, K., et al., Synthesis and characterization of TiO2 nanorods by hydrothermal method with different pH conditions and their photocatalytic activity. Applied Surface Science, 2020. 500: p. 144058. [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, M., et al., Hydrothermal preparation of highly photoactive TiO2 nanoparticles. Catalysis Today, 2007. 129(1-2): p. 50-58. [CrossRef]

- Hayle, S.T. and G.G. Gonfa, Synthesis and characterization of titanium oxide nanomaterials using sol-gel method. American Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 2014. 2(1): p. 1. [CrossRef]

- Maness, P.-C., et al., Bactericidal activity of photocatalytic TiO2 reaction: toward an understanding of its killing mechanism. Applied and environmental microbiology, 1999. 65(9): p. 4094-4098. [CrossRef]

- Shah, M., et al., Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles via biological entities. Materials, 2015. 8(11): p. 7278-7308. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, R., et al., Photocatalytic inactivation of influenza virus by titanium dioxide thin film. Photochemical & Photobiological Sciences, 2012. 11: p. 1293-1298. [CrossRef]

- Syngouna, V.I. and C.V. Chrysikopoulos, Inactivation of MS2 bacteriophage by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in the presence of quartz sand with and without ambient light. Journal of colloid and interface science, 2017. 497: p. 117-125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W., et al., MicroRNA response and toxicity of potential pathways in human colon cancer cells exposed to titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Cancers, 2020. 12(5): p. 1236. [CrossRef]

- Mazurkova, N., et al., Interaction of titanium dioxide nanoparticles with influenza virus. Nanotechnologies in Russia, 2010. 5: p. 417-420. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim Fouad, G., A proposed insight into the anti-viral potential of metallic nanoparticles against novel coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19). Bulletin of the National Research Centre, 2021. 45: p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S., et al., Antibacterial and antiviral potential of colloidal Titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles suitable for biological applications. Materials Research Express, 2019. 6(10): p. 105409. [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy, M.M. and A. Derbalah, Antiviral activity of titanium dioxide nanostructures as a control strategy for broad bean strain virus in faba bean. Pest management science, 2019. 75(3): p. 828-834. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Hernandez, M., et al., Nanoparticles as potential antivirals in agriculture. Agriculture, 2020. 10(10): p. 444. [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.A., et al., Synthesis and characterization of titanium dioxide nanoparticles by chemical and green methods and their antifungal activities against wheat rust. Chemosphere, 2020. 258: p. 127352. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, S., and H. Choi, Method for providing enhanced photosynthesis. Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology, Jeju, South Korea, 2005.

- Lei, Z., et al., Effects of nanoanatase TiO 2 on photosynthesis of spinach chloroplasts under different light illumination. Biological trace element research, 2007. 119: p. 68-76. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodzadeh, H. and R. Aghili, Effect on germination and early growth characteristics in wheat plants (Triticumaestivum L.) seeds exposed to TiO2 nanoparticles. 2014.

- Owolade, O., and D. Ogunleti, Effects of titanium dioxide on the diseases, development and yield of edible cowpea. Journal of plant protection research, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al., Influence of nano-anatase TiO 2 on the nitrogen metabolism of growing spinach. Biological trace element research, 2006. 110: p. 179-190. [CrossRef]

- Jaberzadeh, A., et al., Influence of bulk and nanoparticles titanium foliar application on some agronomic traits, seed gluten, and starch contents of wheat subjected to water deficit stress. Notulae botanicae horti agrobotanici cluj-napoca, 2013. 41(1): p. 201-207. [CrossRef]

- Morteza, E., et al., Study of photosynthetic pigments changes of maize (Zea mays L.) under nano TiO 2 spraying at various growth stages. SpringerPlus, 2013. 2: p. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Raliya, R., P. Biswas, and J. Tarafdar, TiO2 nanoparticle biosynthesis and its physiological effect on mung bean (Vigna radiata L.). Biotechnology Reports, 2015. 5: p. 22-26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raliya, R., et al., Mechanistic evaluation of translocation and physiological impact of titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles on the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plant. Metallomics, 2015. 7(12): p. 1584-1594. [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, S., et al., Role of chemical composition and redox modification of poorly soluble nanomaterials on their ability to enhance allergic airway sensitization in mice. Particle and Fibre Toxicology, 2019. 16(1): p. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, E.B., et al., Anaerobic digestion to reduce biomass and remove arsenic from As-hyperaccumulator Pteris vittata. Environmental pollution, 2019. 250: p. 23-28. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, W., et al., Utilization of biochar produced from invasive plant species to efficiently adsorb Cd (II) and Pb (II). Bioresource Technology, 2020. 317: p. 124011. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dağhan, H., et al., Impact of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs) on growth and mineral nutrient uptake of wheat (Triticum vulgare L.). Biotech Studies, 2020. 29(2): p. 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Larue, C., et al. Investigation of titanium dioxide nanoparticles toxicity and uptake by plants. in Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 2011. IOP Publishing.

| Precursor | Solvent | Catalysis | pH |

Temperature oC |

Crystalline phase | Particles size | Reference |

| Ti(OBu)4 5 cc |

Isopropyl Alcohol 10 cc |

HNO3 | 2 | 400 600 800 |

Anatase Mix (anatase + rutile) Rutile |

6 nm 25.8 nm 33 nm |

[53] |

| TTIP 0.4 M |

Ethyl alcohol 0.1 M | NaOH | 8.5 | 450 900 |

Anatase Rutile |

21-24 nm 69-74 nm |

[54] |

| TTIP 5.5 ml |

Ethanol 54.8 ml |

NH4OH Or HCl |

1 7 10 |

500 | Anatase with rutile Anatase Anatase |

14 nm 19 nm 20 nm |

[55] |

| TTIP 5 mL |

Deionized water 100 mL | NaOH | 7 9 |

400 | Anatase | 14 nm 16 nm |

[56] |

| TTIP 76.7 ml |

Isopropanol 76.4 ml |

HNO3 | 1.5 | 400 500 |

Anatase | 5-10 nm | [57] |

| TiCl4 3.5 ml |

Ethanol 35 ml |

NH4OH | 1.1 | 250 400 600 |

Anatase |

9.22 nm 14.33 nm 36.72 nm |

[58] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).