1. Introduction

Functional Cognitive Disorders are characterized by significant subjective cognitive complaints in the absence of corresponding objective neurological abnormalities typically associated with dementia or other neurodegenerative conditions [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Increasingly recognized as the cognitive counterpart of FND reflects symptoms that are primarily driven by psychological mechanisms, attentional dysregulation, and impaired metacognition rather than structural brain pathology [

5,

6].

Diagnostic ambiguity and terminological overlap remain common in clinical settings, often leading to confusion among healthcare professionals and distress for patients [

3,

7]. Labels such as Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD), pseudodementia, or the colloquial “worried well” have historically been used to describe individuals presenting with cognitive complaints in the absence of identifiable neurodegenerative processes [

1,

8]. However, these terms lack etiological clarity and are frequently unsatisfactory for patients seeking a definitive explanation, often resulting in persistent anxiety and repeated consultations [

9].

Clinicians face considerable challenges when attempting to differentiate FCD from early presentations of MCI or dementia, as the reported symptoms often appear similar at first glance [

10,

11]. Nonetheless, several distinguishing features have been consistently reported in recent research. These include internal inconsistency in cognitive test performance, preserved conversational fluency, a tendency for patients to attend appointments unaccompanied, and the presentation of detailed written notes documenting their cognitive concerns [

12,

13,

14].

Accurate recognition of FCD is of critical importance [

14]. Misdiagnosis may lead to unwarranted investigations, inappropriate treatments, and heightened patient anxiety. In contrast, a correct diagnosis offers reassurance and enables targeted interventions, including psychoeducation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and metacognitive training, which have shown promise in improving patient outcomes [

15,

16].

Despite increasing clinical awareness, there remains a pressing need to standardize diagnostic frameworks, develop validated assessment tools, and promote a positive identification model rather than relying on exclusion [

1,

11]. This paper aims to clarify the concept of FCD, synthesize practical diagnostic strategies grounded in empirical evidence, and reinforce the view of FCD as a distinct, generally non-progressive clinical entity deserving of focused clinical attention and research.

2. Definition and Diagnostic Challenges

Functional Cognitive Disorder is increasingly recognized as the cognitive counterpart of FND, marked by prominent subjective cognitive complaints without corresponding objective evidence of neurological pathology [

1,

5,

17,

18,

19]. Unlike neurodegenerative conditions, the symptoms of FCD are believed to arise from psychological mechanisms, attentional dysfunction, and impaired metacognitive monitoring, rather than structural brain damage [

15,

20]

.

A defining diagnostic feature of FCD is internal inconsistency, whereby an individual’s cognitive performance fluctuates significantly within the same domain or across tasks, often influenced by situational, emotional, or attentional factors [

1,

21,

22]. For example, individuals may demonstrate better delayed recall than immediate recall, or perform inconsistently across similar memory tasks, patterns atypical of progressive neurological diseases.

FCD is frequently misclassified or conflated with related constructs such as SCD, pseudodementia, and the informal label “worried well” [

6,

8,

14]. While SCD broadly refers to individuals who report cognitive complaints in the absence of measurable impairment on neuropsychological tests, pseudodementia typically describes cognitive symptoms that emerge secondary to psychiatric disorders, particularly depression, and are considered potentially reversible with adequate treatment [

3,

9]. However, these terms lack the specificity and explanatory power offered by the FCD framework, often leaving patients with lingering uncertainty about the cause and significance of their cognitive symptoms [

1,

7].

One of the primary challenges for clinicians is the differentiation of FCD from early presentations of MCI or dementia, given the similarity in reported symptoms and the often-normal results of initial cognitive testing [

6,

10]. Despite this overlap, longitudinal studies and structured clinical observations suggest that FCD follows a stable, non-progressive course, distinguishing it from true neurodegenerative conditions [

14,

23,

24]

.

Importantly, misdiagnosis in either direction can be harmful. Patients erroneously labeled with MCI may develop heightened anxiety about impending dementia, which in turn may exacerbate subjective symptoms and reduce overall quality of life [

25,

26,

27]. In contrast, individuals with undiagnosed FCD may undergo unnecessary investigations, receive inappropriate treatments, or lack access to appropriate psychological support [

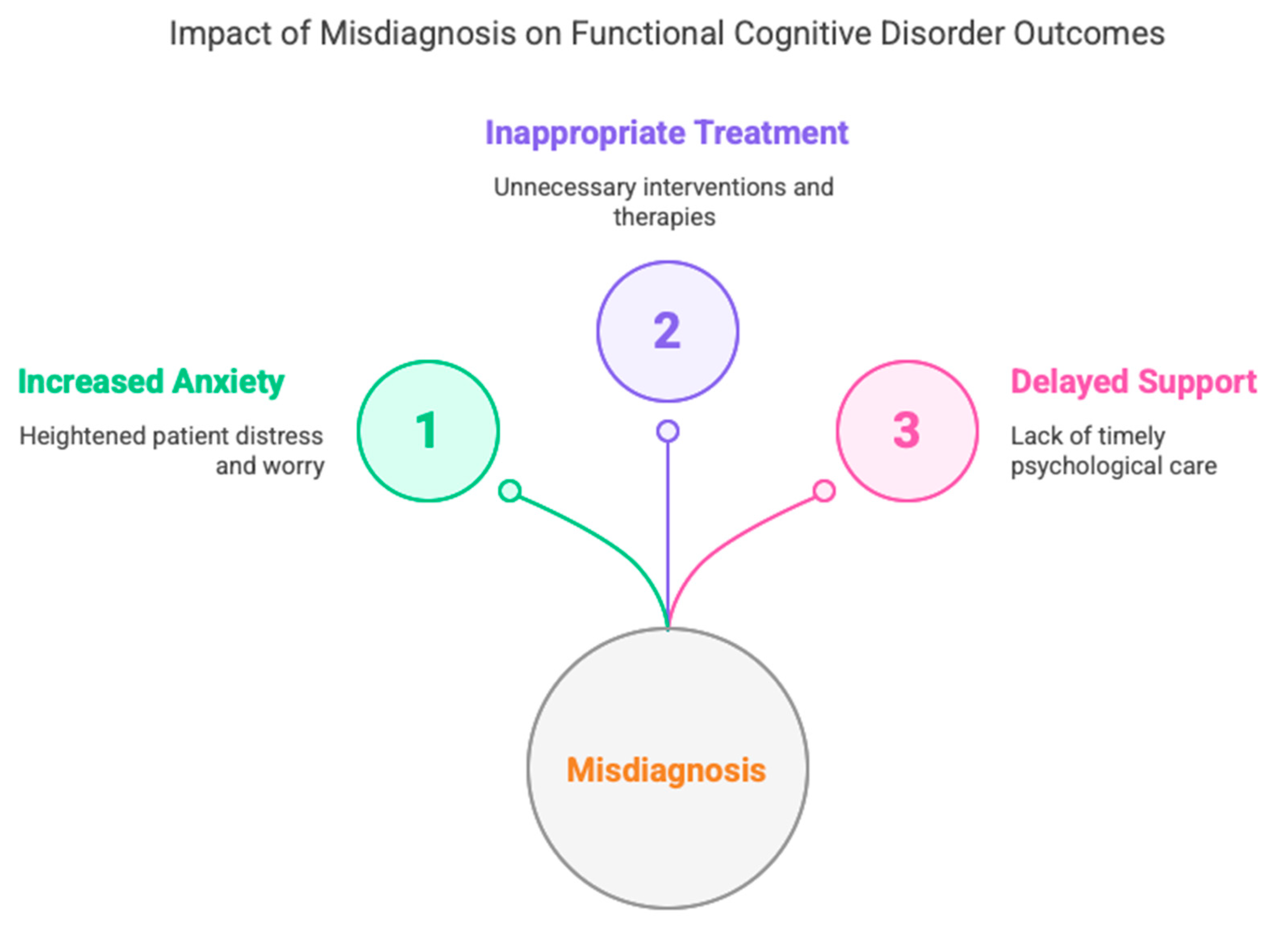

28]. This diagram (

Figure 1) highlights the three major consequences of misdiagnosing FCD: (1) Increased Anxiety, reflecting the distress experienced by patients when diagnostic uncertainty reinforces fears of neurodegeneration; (2) Inappropriate Treatment, representing the risk of unwarranted pharmacological or therapeutic interventions aimed at misattributed conditions; and (3) Delayed Support, referring to the missed opportunity for timely, targeted psychological care such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or metacognitive rehabilitation. Together, these outcomes underscore the critical importance of early and accurate diagnosis.

In response to these diagnostic complexities, recent expert consensus emphasizes the need for positive diagnostic criteria, including internal inconsistency, characteristic interactional behavior, and communication pattern, rather than relying solely on the exclusion of neurodegenerative disease [

5,

12]. This approach supports clearer clinical decision-making and empowers patients with a coherent, explanatory framework for their symptoms.

3. Clinical Signs and Diagnostic Features

Recognizing FCD in clinical practice hinges on identifying a set of characteristic features that reliably distinguish it from neurodegenerative conditions such as MCI and dementia. One of the most critical of these is internal inconsistency, the observation that a patient's cognitive performance varies significantly across time or contexts within the same cognitive domain, in a manner that is incompatible with structural brain disease [

1,

10]. For instance, patients may demonstrate better delayed than immediate recall or maintain fluent conversational abilities while performing poorly on formal memory tasks, suggesting preserved cognitive capacity with context-dependent impairments in retrieval [

6,

15].

A clinically useful operational set of diagnostic criteria for FCD has been proposed by Ball et al. [

1], which includes the following elements:

One or more symptoms of impaired cognitive function;

Evidence of internal inconsistency in performance;

Symptoms not better explained by another medical, neurological, or psychiatric disorder;

Symptoms that result in significant distress, impairment, or warrant clinical attention.

Beyond these core features, systematic reviews and diagnostic meta-analyses have identified additional behavioral and interactional clues that enhance diagnostic confidence. For example, individuals with FCD often present with a distinctive communication profile, characterized by greater fluency and coherence compared to patients with dementia. They frequently provide detailed, unsolicited examples of their cognitive complaints, reflecting preserved episodic memory and meta-awareness [

6,

12].

Interactional behaviors also offer important diagnostic cues [

29]. Patients with FCD are more likely to attend appointments alone, bring structured written notes about their symptoms, and express high levels of concern, often in contrast to dementia patients, who are commonly accompanied by caregivers who contribute substantively to the clinical narrative [

13,

14,

21]. One particularly specific marker is the absence of the "head-turning sign", the behavior of looking toward a caregiver for assistance during memory testing, a behavior frequently seen in dementia but rarely in FCD [

28,

30].

The presence of psychiatric comorbidities, particularly anxiety and depression, is another significant clinical correlate. While FCD is not solely attributable to affective disorders, these comorbidities can contribute to the development and persistence of functional cognitive symptoms [

16,

31].

In an observational study, Teodoro et al. [

32] found that patients with FCD spoke for a median of 124 seconds when describing their memory concerns, markedly longer than the 42-second median in patients with neurodegenerative diagnoses. This verbosity and richness of description suggest preserved verbal fluency and attentional resources, further supporting the functional nature of the disorder.

To enhance diagnostic precision, quantitative tools and structured assessment scales have been developed. Instruments such as the Schmidtke Criteria, the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) for somatic symptom severity, and interactional rating scales can help differentiate FCD from MCI and dementia with encouraging sensitivity and specificity [

6,

23,

33].

Ultimately, the diagnosis of FCD should rest on positive identification of these distinctive features rather than exclusion of organic disease alone [

11,

34]. Careful attention to narrative coherence, metacognitive markers, and psychosocial context allows clinicians to deliver a confident, compassionate diagnosis. This approach not only prevents inappropriate escalation to dementia care pathways but also supports timely psychological intervention and improves overall patient outcomes [

1,

16]

.

4. Communication Patterns and Interactional Profiles

Distinctive communication styles and interpersonal behaviors are central to the clinical recognition of FCD [

10]. Unlike individuals with neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease, patients with FCD typically exhibit preserved or even enhanced verbal fluency during consultations. These communication features serve as positive diagnostic clues, offering contrast to the vague, hesitant, or under-detailed responses often observed in patients with early dementia [

12,

16].

A hallmark characteristic of FCD is the patient’s ability to provide detailed, unsolicited examples of perceived cognitive failures, such as forgetting appointments or losing track of tasks, which are often described in vivid narrative form [

10]. This suggests not only intact episodic memory but also heightened meta-awareness of perceived lapses [

32]. In contrast, individuals with neurodegenerative conditions frequently rely on generalities, require assistance from informants, or are unable to specify the nature or context of their complaints [

10,

31].

Key communication-based features include:

Longer response duration: In a study by Teodoro et al. [

32], individuals with FCD spoke for a median of 124 seconds when describing their cognitive concerns, significantly longer than the 42 seconds observed in patients with neurodegenerative disorders. This verbosity may reflect intact working memory and linguistic fluency, characteristics inconsistent with progressive dementia.

Higher volume and breadth of complaints: Patients with FCD often report difficulties across multiple cognitive domains, memory, attention, word-finding, multitasking, which may indicate heightened vigilance to normal cognitive fluctuations rather than true multidomain cognitive impairment [

1,

16].

“Attending alone” behavior: A notable feature in FCD populations is the tendency to arrive unaccompanied at clinical appointments. These patients often bring written summaries or bullet-pointed notes detailing their concerns, behaviors seldom observed in individuals with dementia, who are frequently accompanied by family members who provide collateral information and support [

1,

12].

Absence of the “head-turning sign”: In neurodegenerative conditions, patients often glance toward caregivers for reassurance or help during cognitive testing, a behavior that is rare in FCD, further reinforcing the functional, rather than organic, nature of their symptoms [

28].

These interactional features and preserved communication abilities underscore the non-progressive nature of FCD and support a positive diagnostic approach that emphasizes what is present, such as coherence, meta-awareness, and social fluency, rather than focusing solely on what is absent [

12,

15].

Recognizing and interpreting these subtle conversational and interpersonal markers requires clinical experience and active listening. However, when used systematically, these features can empower clinicians to move beyond diagnostic exclusion, providing patients with clearer explanations, targeted interventions, and relief from diagnostic uncertainty [

1,

11].

5. Metacognition and Psychological Factors

A growing body of research indicates that impaired metacognition and psychological distress are central to the pathophysiology of FCD. Metacognition, the ability to monitor, reflect upon, and evaluate one’s cognitive performance, is often dysfunctional in individuals with FCD. This metacognitive dysfunction contributes to increased self-monitoring, hyperawareness, and misinterpretation of normal cognitive fluctuations as pathological decline [

1,

16,

31]

.

One key psychological trait frequently observed in FCD is memory perfectionism, whereby individuals hold unrealistically high standards for their memory performance. Even minor forgetfulness is viewed as unacceptable and alarming, fostering a sense of cognitive failure [

10,

35]. This perfectionism may drive hypervigilant attentional styles, wherein patients monitor their memory processes excessively, paradoxically worsening their subjective experience of dysfunction [

1,

15].

Several cognitive-affective biases are commonly associated with FCD (

Table 1):

Impaired metacognitive ability: Patients with FCD often overestimate their cognitive deficits, even in the context of normal or near-normal neuropsychological test results. They may misattribute benign lapses to serious dysfunction, due in part to poor calibration between subjective experiences and objective performance [

1,

16].

Negative interpretation bias: Individuals with FCD may selectively attend to episodes of forgetfulness and interpret them as signs of progressive brain disease, reinforcing anxiety and worry [

16]

Memory-related anxiety and societal expectations: Cultural narratives and personal beliefs about aging or family history of dementia can exacerbate memory-related fears. Many patients report assuming that cognitive decline is inevitable, thereby interpreting normal lapses as harbingers of irreversible decline [

32].

Cogniphobia: This term describes the avoidance of cognitively demanding situations due to fear of failure or embarrassment. Patients with FCD may reduce engagement in work or social settings, limiting opportunities to challenge maladaptive beliefs and perpetuating functional impairment [

1,

6].

These cognitive and emotional dynamics create a self-perpetuating cycle in which excessive self-focus, distress, and avoidance reinforce the salience and persistence of cognitive complaints. Encouragingly, targeted psychological interventions such as cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which aim to address metacognitive beliefs, reduce avoidance, and promote adaptive thinking, have shown promising outcomes in this population [

6,

16].

Reduces exposure to corrective experiences, reinforcing dysfunctional beliefs.

Mood and anxiety disorders are commonly comorbid with FCD. Although they may intensify cognitive concerns, FCD should not be viewed merely as a manifestation of affective disturbance. Rather, it constitutes a distinct clinical entitythat overlaps with but is not reducible to depression or generalized anxiety disorder [

6,

31]. The presence of psychiatric comorbidities should be regarded as diagnostically informative, helping clinicians contextualize symptom development and persistence.

Ultimately, understanding the psychological architecture of FCD provides both explanatory insight and therapeutic direction. Shifting the clinical narrative away from structural pathology and toward dysfunctional self-appraisal, maladaptive illness beliefs, and metacognitive dysregulation allows clinicians to offer patients a hopeful and scientifically grounded explanation of their symptoms.

6. Long-Term Outcomes

Understanding the long-term trajectory of FCD is essential for distinguishing it from progressive neurodegenerative conditions such as MCI and dementia. One of the most common concerns among patients diagnosed with FCD is the fear that their cognitive symptoms represent the early stages of an irreversible decline. This anxiety is often intensified by diagnostic uncertainty and the overlap in early clinical presentations with neurodegenerative syndromes [

1,

6].

However, longitudinal studies increasingly support the view that FCD is generally a stable, non-progressive condition, with most individuals maintaining consistent cognitive functioning over time [

16,

31]

. One of the most compelling studies in this domain is a 10-year prospective follow-up involving individuals with SCD. Within this cohort, a subset who met criteria for FCD based on the Schmidtke inventory did not progress to MCI or dementia throughout the follow-up period [

6,

23]. This suggests that the use of structured, symptom-based criteria such as the Schmidtke scale may offer strong predictive validity in identifying individuals at low risk for neurodegeneration.

These findings underscore the clinical value of making a positive diagnosis of FCD, rather than one based on exclusion. When clearly communicated, such a diagnosis can provide significant reassurance to patients, shift the therapeutic focus away from unnecessary diagnostic testing, and redirect care toward more appropriate psychological and rehabilitative strategies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy or metacognitive training [

1,

16].

Nevertheless, FCD is not a monolithic condition. Heterogeneity exists in clinical presentations and outcomes. While many individuals demonstrate cognitive stability or spontaneous improvement, others may experience persistent distress, often linked to unresolved psychological factors, comorbid anxiety or depression, or entrenched maladaptive beliefs about cognitive functioning [

10,

35]. In a minority of cases, symptoms initially attributed to FCD may eventually evolve into neurodegenerative disorders, though such instances may reflect baseline diagnostic uncertainty, misclassification, or true comorbidity [

1,

21].

Recent models conceptualize FCD as existing along a spectrum, ranging from brief, reversible episodes of cognitive dysfunction to more chronic and impairing functional syndromes [

1,

15]. Crucially, this variability in presentation does not imply inevitable progression, but rather highlights the importance of individualized, longitudinal care and periodic reassessment when new clinical features emerge.

In practice, communicating the typically benign prognosis of FCD can be transformative for patients. It not only alleviates anxiety but also promotes better engagement with psychological therapies and supportive interventions. Moreover, it prevents premature entry into dementia care pathways, thus reducing unnecessary medicalization and reinforcing the functional nature of the condition [

6,

31].

7. Assessment Methods

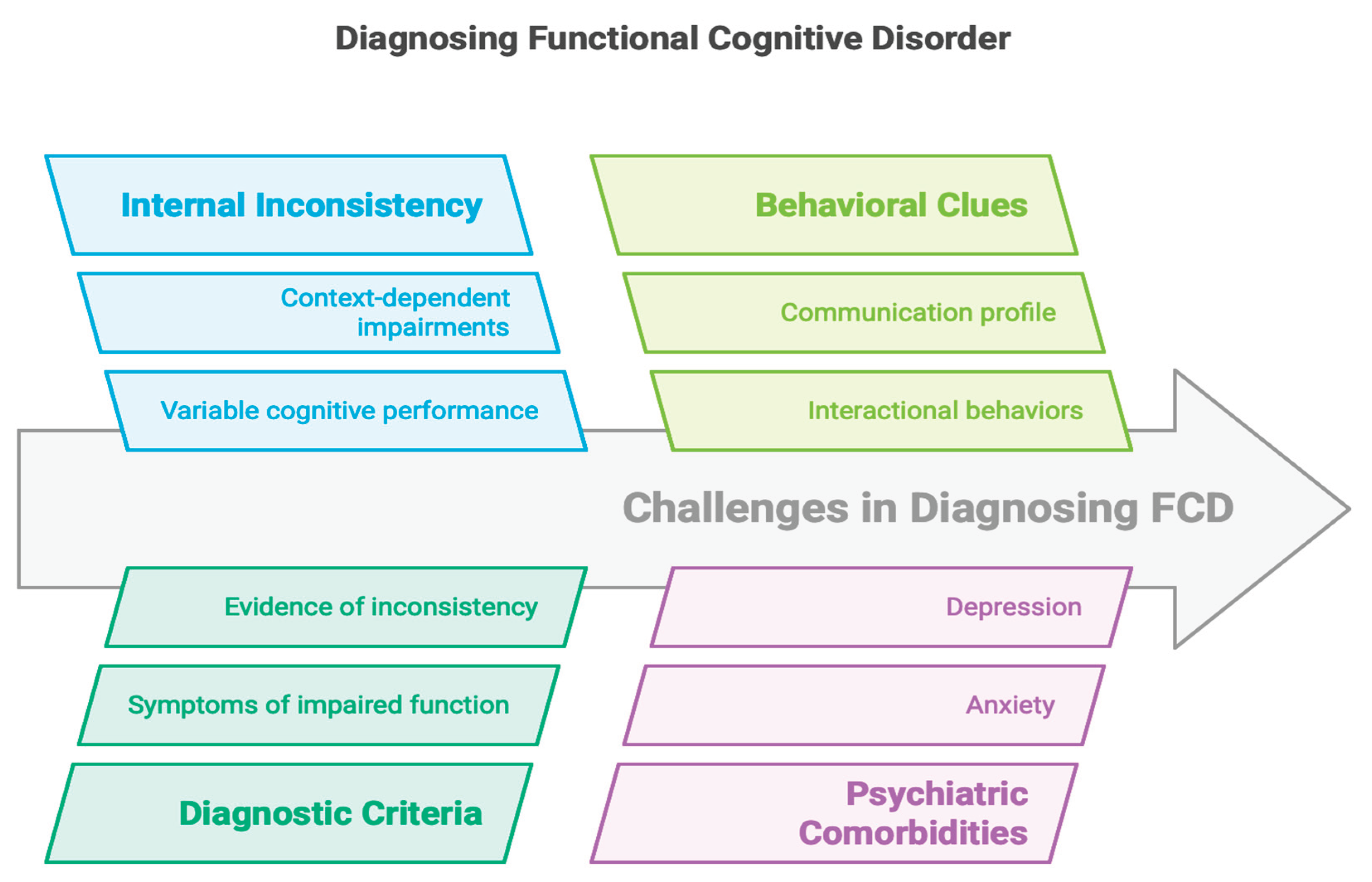

Diagnosing FCD requires a multimodal clinical approach that combines careful interviewing, observational data, formal neuropsychological testing, and validated structured tools (

Figure 2). Unlike neurodegenerative disorders, where imaging, cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, or genetic testing may support the diagnosis, FCD remains a clinical diagnosis, centered on the identification of positive features and the exclusion of progressive pathology [

1,

6].

Various assessment methods contribute uniquely to the diagnostic process of FCD, as outlined in

Table 2. Neuropsychological testing evaluates key cognitive domains such as memory and attention, helping to detect impairments that are inconsistent with typical neuroanatomical patterns. Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) and Mini-mental state examination (MMSE), as brief cognitive screening tools, may show normal scores despite severe subjective complaints, suggesting a functional rather than neurodegenerative origin. Medical Symptom Validity Tests (e.g., MSVT) assess the consistency and effort of responses, often revealing attentional interference or metacognitive disruption rather than intentional deception. Questionnaires like the PHQ-15,

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and

Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire (MMQ) evaluate somatic symptoms, mood, sleep, and memory beliefs; elevated scores in the absence of objective deficits further support a functional diagnosis. Interactional analysis observes symptom narratives and communication behaviors, such as coherence, verbosity, and attending appointments alone, which can be characteristic of FCD presentations. The MINI interview helps identify comorbid psychiatric conditions like depression, anxiety, or trauma that are relevant to the formulation of FCD. Finally, the Schmidtke Criteria provide a standardized, symptom-based framework with predictive value for non-progression, strengthening the diagnostic confidence in functional cognitive presentations.

7.1. Neuropsychological Testing

Formal neuropsychological assessments are essential to evaluate cognitive domains such as memory, attention, language, and executive functioning. In FCD, testing often reveals normal or inconsistently impaired results, with patterns that do not conform to known neuroanatomical distributions [

1,

21]. A typical red flag is a discrepancy between severe subjective complaints and relatively intact objective performance [

36].

7.2. Cognitive Screening Instruments

Brief cognitive screeners like the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) are commonly used as initial tools. While not specific to FCD, normal performance on these tests, when paired with marked self-reported deficits, should raise clinical suspicion for a functional etiology [

37,

38].

7.3. Medical Symptom Validity Tests (MSVT)

Performance validity tests such as the MSVT can help assess effort and test-taking consistency. In FCD, suboptimal performance is not necessarily indicative of malingering, but may instead reflect attentional disruption, anxiety, or metacognitive interference [

10,

35]. These instruments must be interpreted within a compassionate clinical context.

7.4. Structured Questionnaires

Several validated self-report tools support the diagnosis of FCD and help assess common psychological comorbidities:

PHQ-15: Somatic symptom severity [

33];

HADS: Depression and anxiety screening [

1].

PSQI: Sleep disturbance assessment [

39];

MMQ: Assesses memory beliefs and self-perception [

10];

High scores in the absence of objective impairment suggest a functional overlay or psychological contributors to the cognitive complaints.

7.5. Interactional and Conversational Assessment

Patients' speech patterns and interpersonal behavior can be diagnostically informative. Tools developed by Reuber et al. [

12] and Teodoro et al. [

32] measure features such as narrative coherence, verbosity, and spontaneous detail, which help differentiate FCD from organic cognitive decline. For instance, patients with FCD often provide long, detailed accounts of their symptoms, demonstrating preserved verbal fluency and insight.

7.6. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview is a structured psychiatric interview that facilitates identification of mood and anxiety disorders, conditions that frequently co-occur with FCD and may influence symptom persistence [

31].

7.7. The Schmidtke Criteria

This 10-item inventory was designed to aid in diagnosing functional memory disorder by evaluating symptom inconsistency, preserved daily function, and distress. Its predictive validity for identifying patients unlikely to progress to dementia has been demonstrated in long-term follow-up studies [

6,

23].

8. Related Concepts and Differential Diagnosis

FCD shares overlapping features with several cognitive conditions and distinguishing it from these is crucial for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

8.1. Subjective Cognitive Decline

SCD refers to the perception of cognitive decline in the absence of objective deficits on testing [

8]. While some cases of SCD precede neurodegenerative disease, others, especially those with internal inconsistency and psychiatric comorbidities, align more closely with FCD [

6,

31]

8.2. Pseudodementia

This older term refers to cognitive symptoms caused by depression or psychiatric disorders. Although pseudodementia can overlap with FCD, the latter is not solely attributable to mood disorders. FCD emphasizes the role of metacognitive dysfunction and cognitive-behavioral mechanisms rather than only affective disturbance [

1,

10].

8.3.“Worried Well”

Often used dismissively, this term refers to cognitively intact individuals with high health anxiety. However, it lacks clinical utility and may invalidate genuine distress. In contrast, FCD acknowledges these concerns within a diagnostic framework, providing a more respectful and therapeutic lens [

1,

16]

.

8.4. Cogniform Disorder

A proposed but not widely adopted term, Cogniform Disorder encompasses functional cognitive symptoms not explained by neurological disease. It overlaps conceptually with FCD and reflects ongoing efforts to formalize the diagnosis of functional memory syndromes [

10]

8.5. Functional Neurological Disorder

FCD is increasingly recognized as the cognitive counterpart to FND. Both share features such as symptom inconsistency, non-progressive course, and associations with psychological distress and attentional dysregulation [

1,

15]. Recognizing this relationship helps align FCD within the broader category of functional disorders.

9. Conclusion

Functional Cognitive Disorder represents an increasingly recognized but still underdiagnosed condition within the spectrum of cognitive disorders. Characterized by genuine cognitive complaints in the absence of progressive neurological pathology, FCD challenges traditional diagnostic paradigms, which often rely heavily on exclusion. However, emerging evidence highlights the presence of positive diagnostic features, such as internal inconsistency, distinct communication styles, and preserved interactional profiles, that support a confident clinical diagnosis.

Differentiating FCD from conditions like mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and pseudodementia is essential. Misclassification not only leads to inappropriate investigations and management strategies but can also heighten patient distress and reinforce maladaptive illness beliefs. In contrast, a timely and accurate diagnosis of FCD can provide significant reassurance and guide individuals toward evidence-based psychological interventions that target metacognitive dysfunction, memory-related anxiety, and associated behavioral avoidance.

Longitudinal data support the view of FCD as a non-progressive condition for most individuals, with stable cognitive trajectories over time. These findings, alongside tools such as the Schmidtke criteria and structured conversational profiling, offer clinicians robust strategies for identifying FCD in memory clinic populations.

Despite these advances, FCD remains an under-researched area. Further work is needed to refine diagnostic criteria, validate assessment tools, and develop tailored treatment pathways. Recognizing FCD as a legitimate and treatable clinical entity, rather than as a diagnosis of exclusion, is essential for improving patient care, reducing stigma, and integrating functional cognitive disorders more meaningfully into the landscape of neuropsychiatric medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M., C.A., F.P., and K.F.; Methodology, I.M., F.P., and A.C.; Validation, I.M., C.A., F.P., and K.F.; Formal analysis, I.M. and V.R..; Investigation, I.M., C.A., F.P., K.F., and M.V.; Data curation, I.M. and M.V.; Writing - original draft preparation, I.M. and K.F.; Writing - review and editing, I.M., F.P., A.C., V.R., C.A., and M.V.; Visualization, I.M. and K.F.; Supervision, A.C. and D.K.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PHQ-15 |

Patient Health Questionnaire-15 |

| HADS |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| PSQI |

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| MMQ |

Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire |

| FCD |

Functional Cognitive Disorder |

References

- Ball, H.A.; McWhirter, L.; Ballard, C.; Bhome, R.; Blackburn, D.J.; Edwards, M.J.; Fleming, S.M.; Fox, N.C.; Howard, R.; Huntley, J.; et al. Functional Cognitive Disorder: Dementia’s Blind Spot. Brain 2020, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, N.A.; Cope, S.R.; Bailey, C.; Isaacs, J.D. Functional Cognitive Disorders: Identification and Management. BJPsych Adv 2019, 25, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.; Pal, S.; Blackburn, D.; Reuber, M.; Thekkumpurath, P.; Carson, A. Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2015, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Medina, D.S.; Arenas-Vargas, P.A.; del Pilar Velásquez-Duque, M.; Bagnati, P.M. Functional Cognitive Disorder: Beyond Pseudodementia. Neurology Perspectives 2025, 5, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, C.; Ball, H.; Swirski, M. Functional Cognitive Disorder: Diagnostic Challenges and Future Directions. Diagnostics 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabreira, V.; Frostholm, L.; McWhirter, L.; Stone, J.; Carson, A. Clinical Signs in Functional Cognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. J Psychosom Res 2023, 173, 111447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.; Bell, S.M.; Blackburn, D.M. How the UK Describes Functional Memory Symptoms. Psychogeriatrics 2017, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; Van Boxtel, M.; Breteler, M.; Ceccaldi, M.; Chételat, G.; Dubois, B.; Dufouil, C.; Ellis, K.A.; Van Der Flier, W.M.; et al. A Conceptual Framework for Research on Subjective Cognitive Decline in Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman-Filipiak, A.M.; Giordani, B.; Heidebrink, J.; Bhaumik, A.; Hampstead, B.M. Self- and Informant-Reported Memory Complaints: Frequency and Severity in Cognitively Intact Individuals and Those with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Neurodegenerative Dementias. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2018, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, C.; Newson, M.; Hayre, A.; Coulthard, E. Functional Cognitive Disorder: What Is It and What to Do about It? Pract Neurol 2015, 15, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabreira, V.; McWhirter, L.; Carson, A. Functional Cognitive Disorder: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Differentiation from Secondary Causes of Cognitive Difficulties. Neurol Clin 2023, 41, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuber, M.; Blackburn, D.J.; Elsey, C.; Wakefield, S.; Ardern, K.A.; Harkness, K.; Venneri, A.; Jones, D.; Shaw, C.; Drew, P. An Interactional Profile to Assist the Differential Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative and Functional Memory Disorders. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2018, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharambe, V.; Larner, A.J. Functional Cognitive Disorders: Demographic and Clinical Features Contribute to a Positive Diagnosis. Neurodegener Dis Manag 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, L.; Ritchie, C.; Stone, J.; Carson, A. Identifying Functional Cognitive Disorder: A Proposed Diagnostic Risk Model. CNS Spectr 2022, 27, 754–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teodoro, T.; Edwards, M.J.; Isaacs, J.D. A Unifying Theory for Cognitive Abnormalities in Functional Neurological Disorders, Fibromyalgia and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Systematic Review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2018, 89, 1308–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhome, R.; McWilliams, A.; Price, G.; Poole, N.A.; Howard, R.J.; Fleming, S.M.; Huntley, J.D. Metacognition in Functional Cognitive Disorder. Brain Commun 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laukaityte, U.; Laukaityte, U. The Scope of Functional Neurological Disorder: Symptom Perception, Inference, and Psychiatry 2024.

- Tamilson, B.; Poole, N.; Agrawal, N. The Co-Occurrence of Functional Neurological Disorder and Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp, S.; Kapur, N.; Graham, C.D.; Reuber, M. Functional Cognitive Disorder: Differential Diagnosis of Common Clinical Presentations. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhome, R.; McWilliams, A.; Huntley, J.D.; Fleming, S.M.; Howard, R.J. Metacognition in Functional Cognitive Disorder- a Potential Mechanism and Treatment Target. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 2019, 24, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, S.J.; Blackburn, D.J.; Harkness, K.; Khan, A.; Reuber, M.; Venneri, A. Distinctive Neuropsychological Profiles Differentiate Patients with Functional Memory Disorder from Patients with Amnestic-Mild Cognitive Impairment. Acta Neuropsychiatr 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, N.D.; Rush, B.K. Neuropsychological Evaluation of Functional Cognitive Disorder: A Narrative Review. Clinical Neuropsychologist 2024, 38, 302–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke, K.; Metternich, B. Validation of Two Inventories for the Diagnosis and Monitoring of Functional Memory Disorder. J Psychosom Res 2009, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, N.A.; Cope, S.R.; Bailey, C.; Isaacs, J.D. Functional Cognitive Disorders: Identification and Management. BJPsych Adv 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabbagh, M.N.; Boada, M.; Borson, S.; Chilukuri, M.; Dubois, B.; Ingram, J.; Iwata, A.; Porsteinsson, A.P.; Possin, K.L.; Rabinovici, G.D.; et al. Early Detection of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) in Primary Care. Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease 2020, 7, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, E.C.; Delano-Wood, L.; Galasko, D.R.; Salmon, D.P.; Bondi, M.W. Subjective Cognitive Complaints Contribute to Misdiagnosis of Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 2014, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voros, V.; Fekete, S.; Tenyi, T.; Rihmer, Z.; Szili, I.; Osvath, P. Untreated Depressive Symptoms Significantly Worsen Quality of Life in Old Age and May Lead to the Misdiagnosis of Dementia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 2020, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghadiri–Sani, M.; Larner, A. Head turning sign for diagnosis of dementia and mild cognitive impairment: a revalidation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2013, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsey, C.; Drew, P.; Jones, D.; Blackburn, D.; Wakefield, S.; Harkness, K.; Venneri, A.; Reuber, M. Towards Diagnostic Conversational Profiles of Patients Presenting with Dementia or Functional Memory Disorders to Memory Clinics. Patient Educ Couns 2015, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, P.; Usarel, C.; Ispirli, G.; Isik, A.T. Attended with and Head-Turning Sign Can Be Clinical Markers of Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults. Int Psychogeriatr 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, L.; Ritchie, C.; Stone, J.; Carson, A. Functional Cognitive Disorders: A Systematic Review. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, T.; Koreki, A.; Chen, J.; Coebergh, J.; Poole, N.; Ferreira, J.J.; Edwards, M.J.; Isaacs, J.D. Functional Cognitive Disorder Affects Reaction Time, Subjective Mental Effort and Global Metacognition. Brain 2023, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascherek, A.; Zimprich, D.; Rupprecht, R.; Lang, F.R. What Do Cognitive Complaints in a Sample of Memory Clinic Outpatients Reflect? GeroPsych: The Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry 2011, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Patten, R.; Bellone, J.A. The Neuropsychology of Functional Neurological Disorders. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2023, 45, 957–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picon, E.L.; Todorova, E. V.; Palombo, D.J.; Perez, D.L.; Howard, A.K.; Silverberg, N.D. Memory Perfectionism Is Associated with Persistent Memory Complaints after Concussion. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology 2022, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamarian, L.; Högl, B.; Delazer, M.; Hingerl, K.; Gabelia, D.; Mitterling, T.; Brandauer, E.; Frauscher, B. Subjective Deficits of Attention, Cognition and Depression in Patients with Narcolepsy. Sleep Med 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, A.J. Screening Utility of the Attended Alone Sign for Subjective Memory Impairment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2014, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, A.J. “Who Came with You?” A Diagnostic Observation in Patients with Memory Problems? [1]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarik Elhadd, K. Functional Cognitive Disorders: Can Sleep Disturbance Contribute to a Positive Diagnosis? Article in Journal of Sleep Disorders & Therapy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).