1. Introduction

Neonatal thyroid function testing, primarily based on Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) assessment, detects not only Permanent Congenital Hypothyroidism (PCH), which has an incidence of approximately 1 in 4,000 births, but also Transient Congenital Hypothyroidism (TCH) (1). The incidence of TCH varies and can be as high as 1 in 10 newborns, with the main cause being iodine deficiency (ID). Robust evidence supports a cause-and-effect relationship between iodine deficiency and the pathogenesis of TCH [

2,

3,

4]. In affected children, normal thyroid function is typically achieved by the end of the third year of life, allowing discontinuation of levothyroxine treatment. Normal thyroid function is subsequently maintained into adulthood, similar to other healthy individuals [

5,

6].

Following the introduction of newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism, the incidence of TCH in Europe, where iodine deficiency was historically prevalent, was reported to be nearly eight times higher than in North America, where iodine deficiency had been addressed decades earlier [

7]. The role of iodine deficiency in the aetiology of TCH has also been confirmed through studies demonstrating the preventive effects of iodine supplementation [

8].

In Greece, newborn screening for congenital hypothyroidism (CH) using TSH measurement in dried blood spots (Guthrie Card) began in 1979 through the Institute of Child Health (ICH). The first dataset, collected one year after the program’s initiation from a sample of 75,879 newborns, reported a prevalence of CH (including both permanent and transient forms) of 1 in 4,200 [

9]. A subsequent report in 1994, based on a larger sample of 1,274,000 newborns, showed a prevalence of CH at 1 in 3,379. Notably, in this report, the TSH cut-off for the initial screening was set at 30 mU/L. In the same study, “false positive” cases were reported at a prevalence of 1 in 368, amounting to 3,459 cases. However, the term "false positive" was used differently than the current understanding of TCH [

10]. The estimated overall prevalence of TCH, irrespective of causative factors, was 1 in 14,154 [

11]. From the year 2012 the cut-off point was further reduced to 7 mU/L.

Although the general Greek population is now considered to be iodine-replete, the majority of pregnant Greek women are mildly iodine-deficient according to WHO criteria. Still, a significant number of cases exhibit moderate iodine deficiency [

12]. A clinical study conducted in Athens in 2012, which monitored iodine intake in a sample of pregnant women during the first trimester, found that more than 50% had urinary iodine excretion (UIE) levels below 100 µg/L, and one-third had levels below 50 µg/L, indicative of mild and moderate iodine deficiency, respectively [

13].

The aim of our retrospective study was to record the cases of TCH and the main causative factor over a 10-year period (2010–2019) in Greece, a period when the country was iodine-replete. We sought to analyse the factors contributing to the occurrence of TCH and study its specific aetiopathogenic characteristics in conjunction with existing data on daily iodine intake during the same period.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

The number of births in Greece between 2010 and 2019 (Group A) was collected from the Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) archives [

14]. Additionally, from the archives of the Institute of Child Health (ICH) in Greece, which covers newborn screening across the country, we recorded all newborns screened for Congenital Hypothyroidism (CH) during the same period (Group A1). TSH levels were measured in dried blood spots using Guthrie cards. Blood samples were collected via heel prick between the third and fifth day of life, typically prior to hospital discharge, and the Guthrie cards were mailed to the ICH daily or every second day.

If a TSH value on the Guthrie card exceeded 7 mU/L, a second measurement was performed in duplicate using the initial Guthrie card. TSH levels below 7 mU/L on the repeat specimen were considered normal, and no further action was undertaken, as the infant was typically over 1 month old at the time of re-examination. A TSH value above 7 mU/L on the initial Guthrie card was considered positive for CH, and the newborn was referred for biochemical and clinical evaluation. CH was confirmed, and treatment with L-thyroxine was initiated if serum TSH levels exceeded 10 mU/L.

For all identified cases of CH, we followed-up with families, paediatricians, and paediatric endocrinologists to determine whether L-thyroxine therapy had been successfully discontinued for at least two months after the child’s third birthday. Demographic data, including gender, gestational age, and birth weight, were collected from the archives of the ICH. Maternal data, including thyroid medication use and the presence of elevated thyroid autoantibodies (antithyroglobulin or antiperoxidase) during pregnancy and childbirth, were also recorded (Group B). Newborns were categorized as full-term (Group B1) or premature (Group B2). From this group of identified CH cases with successful contact with families and doctors, we classified cases that had successfully discontinued thyroxine treatment as presenting with TCH (Group C). The remaining cases were considered to have PCH (Group D).

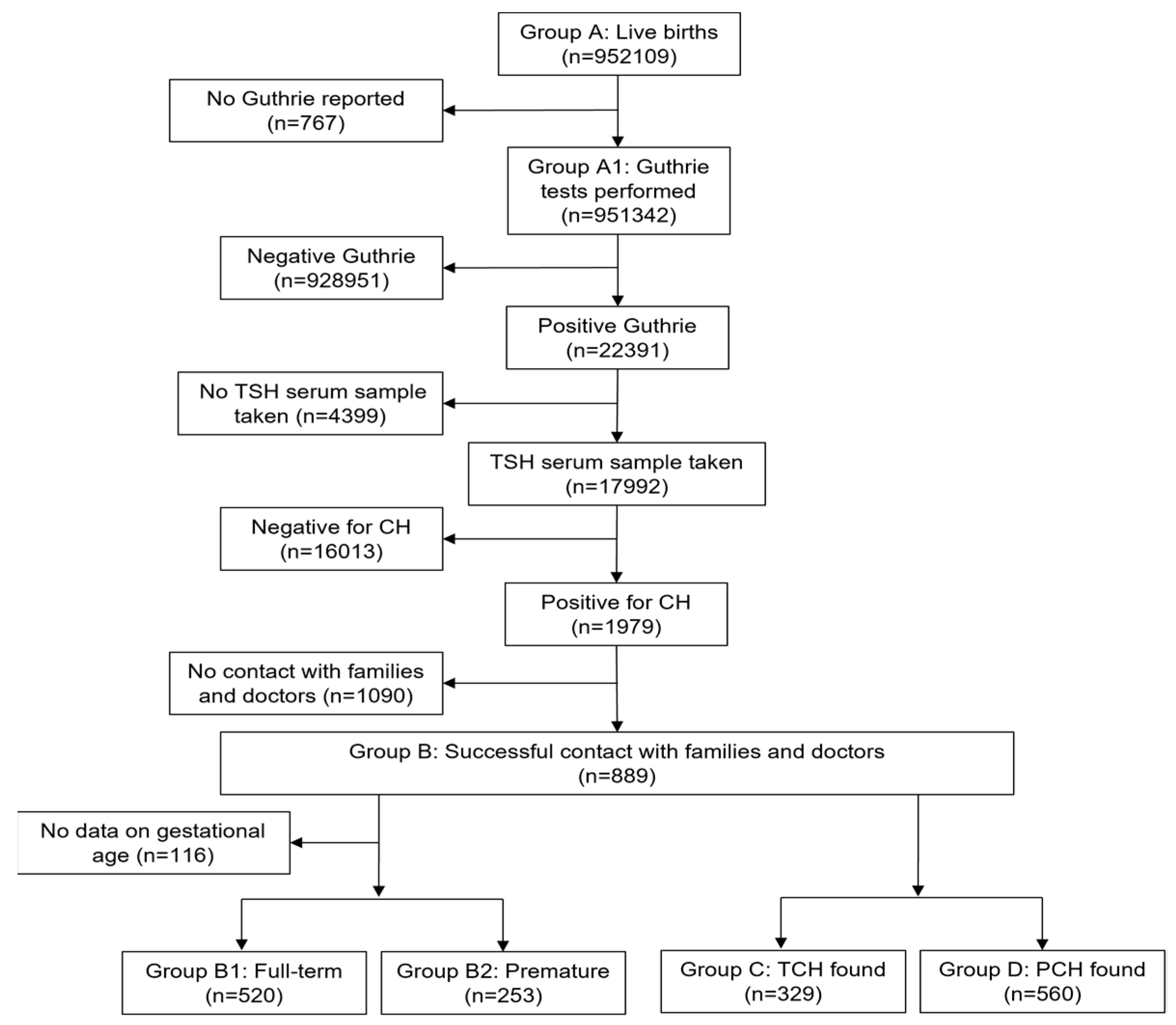

The flow-chart of data collection and preliminary analysis is shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Data Selection

To identify TCH cases not influenced by maternal factors during gestation, the following subgroups were subsequently defined:

Group C: Children who successfully discontinued thyroxine therapy, classified as TCH

Group C1: Full-term babies

Group C2: Premature babies

Group Ca: Children whose mothers had elevated thyroid autoantibodies but normal thyroid function tests (TFTs), and not receiving thyroid medication during pregnancy

-

Group C3: Children whose mothers received thyroid medication during pregnancy

Group D: Children who continued thyroxine therapy, classified as PCH

Group D1: Full-term babies

Group D2: Premature babies

Group Da: Children whose mothers had elevated thyroid autoantibodies, normal TFTs, and not receiving thyroid medication during pregnancy

-

Group D3: Children whose mothers received thyroid medication during pregnancy

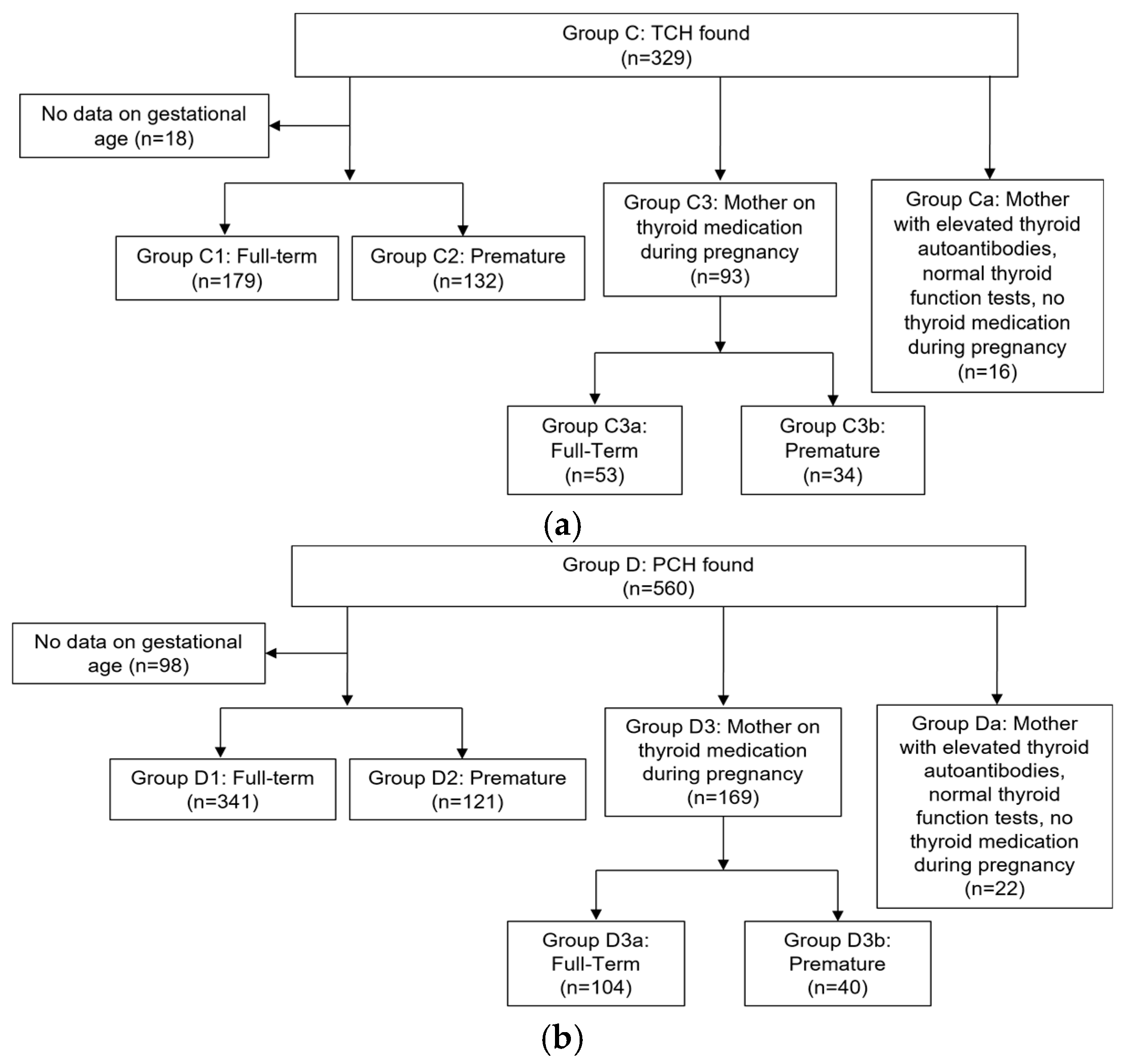

To identify TCH cases not influenced by maternal factors during gestation, such as medication use or elevated thyroid autoantibodies, we excluded Groups Ca and C3 from the total of Groups C1 and C2, resulting in the Target Group of our study. This group was further divided into full-term (Target Group 1) and premature (Target Group 2) infants. The flow-chart of the selection of the cases included in the analysis is shown in

Figure 2a and

Figure 2b.

2.3. Laboratory Measurements

Commercially available reagents from Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany) were used to measure serum TSH, antithyroglobulin antibodies, and antiperoxidase antibodies. Analyses were performed on an Elecsys 2010 apparatus (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) using an electrochemiluminescence technique.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (version 17.0; Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. Student’s t-test was used for comparisons of numerical variables, while Pearson’s χ2 test was employed for comparisons of proportions. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between the centile of birth weight, premature birth (1 = yes, 0 = no), gender of the child (female = 1, male = 0), maternal treatment for hyper- or hypothyroidism(1 = yes, 0 = no), and the presence of increased maternal antithyroid antibodies with normal thyroid function (1 = yes, 0 = no) with the occurrence of transient hypothyroidism in children (1 = yes, 0 = no). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to evaluate the effects of gender, term/preterm birth status, and transient/permanent hypothyroidism on the centile of birth weight.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study received approval from the local ethics committee of the Institute of Child Health (Decision Number 740A/16.7.2025). Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of the participating children.

3. Results

The total number of births in the decade 2010-2019 according to the ELSTAT data was 952,109.

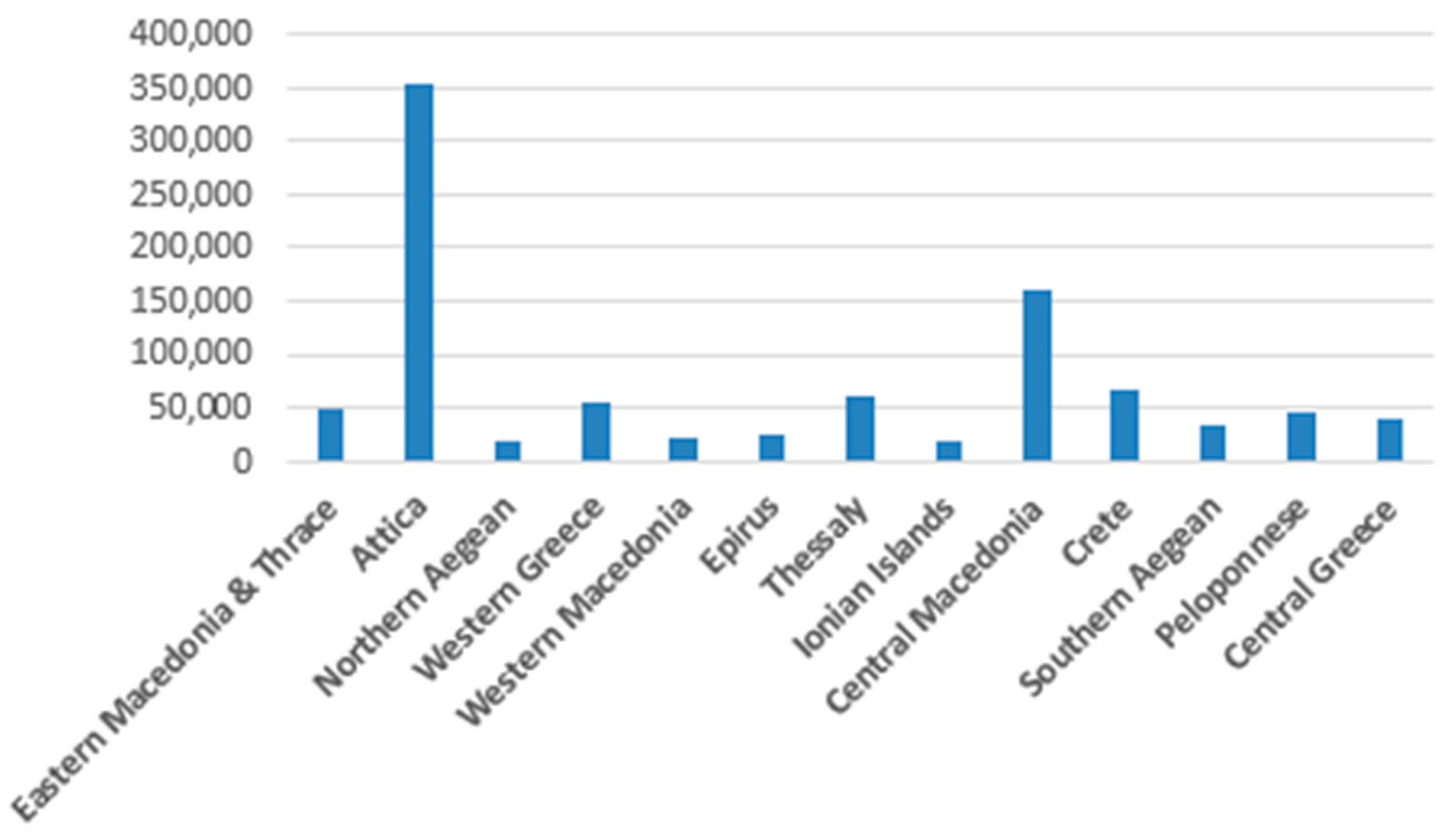

Figure 3 presents the geographical distribution of Group A.

The total number of newborns assessed in the period 2010-2019 in the ICH in Greece was 951,342 (99%) (Group A1). During this period, 22,391 newborns were detected with TSH >8 mIU/L after the second check on the initial card. Among those, 17,992 underwent re-testing with a serum sample, while 4,399 cases could not be re-assessed. Out of the re-tested newborns, 1,979 were screened positive for congenital hypothyroidism (CH) and immediately began treatment with levothyroxine.

After contacting the families and doctors of these cases, successful contact was made with 889 individuals (Group B). From this group, it was found that 329 children had successfully discontinued thyroxine treatment (Group C). These cases are classified as presenting with TCH. The remaining 560 cases were considered to have PCH (Group D).

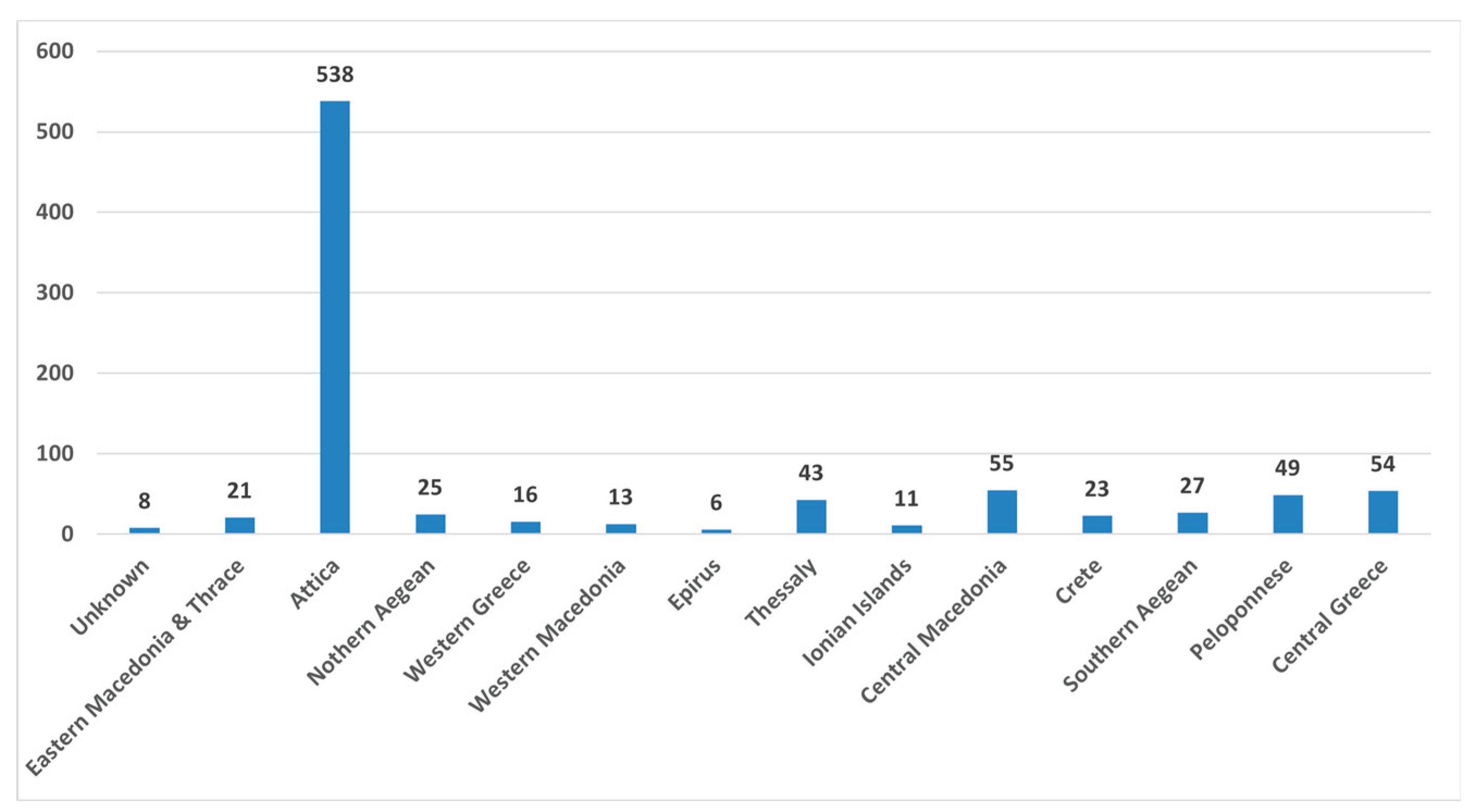

Figure 4 presents the geographical distribution of Group B.

It is evident that the geographical distribution of cases with TCH closely mirrors the distribution of total births per geographic area.

Results for 300 cases were available regarding maternal thyroid autoimmunity positivity with normal thyroid function (Groups Ca and Da) and maternal thyroid treatment (Groups C3 and D3). Further results are shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis revealed that, while controlling for all other predictor variables, the odds ratio of transient hypothyroidism was 2.078 times (95% CI: 1.530 to 2.821, p = 0.001) in prematurely born children compared to those born at term. The effect of other predictors on transient versus permanent hypothyroidism was not significant. ANOVA indicated an interaction between prematurity/permanent hypothyroidism and centile of birthweight (F = 7.861 & 5.205, p = 0.005 & 0.023, respectively).

The cases not influenced by maternal factors during gestation, such as medication use or elevated thyroid autoantibodies were 262 (girls=140, boys=122). Out of them, 95 presented TCH (Target Group) while the rest PCH. The only determining factor for PCH is gender: Females had an odds ratio of 1.86 (1.06 - 3.26, p=0.029).

4. Discussion

The primary objective of this retrospective study was to document cases of transient congenital hypothyroidism (TCH) in Greece from 2010 to 2019 and analyse contributing factors. Data from this decade suggest that Greece was iodine-replete, except for sporadic cases of iodine deficiency among pregnant women [

12,

15].

Our stepwise approach to analysing TCH cases identified key factors influencing its occurrence, including prematurity, maternal autoimmune thyroid disease, and maternal use of medications affecting thyroid function. Genetic causes of TCH, such as mutations in factors influencing thyroid hormone production, are rare, and goitrogens are not a dietary concern for Greek pregnant women [

13]. Iodine availability remains the most significant exogenous factor influencing thyroid hormone biosynthesis and TCH occurrence [

5].

Prematurity emerged as the leading cause of TCH in our study. This finding persisted across the total cohort and subgroups, including those exposed to adverse maternal environments (e.g., increased thyroid autoantibodies or maternal thyroid medications) and those without such influences. It is known that the risk for TCH increases with the degree of prematurity [

16,

17]. There is robust evidence supporting a causal relationship between inadequate iodine intake and TCH [

1,

18,

19]. Studies have also demonstrated that iodine supplementation prevents TCH [

8]. Prematurity is one of the most important factors for TCH development, especially in iodine-sufficient countries. Other causes of TCH are maternal exposure to thyroid medications, increased maternal thyroid autoantibodies, the use of iodine-based skin disinfectants on premature infants or, of course, untreated maternal hypothyroidism [

20]. The incidence of TCH increases with the lower gestational age and is attributed to immaturity of the thyroid function to respond to a variety of factors, such as those mentioned above [

17]. Our findings are in line with existing literature data, both regarding the total number of TCH identified as well as in the Target Group.

In agreement with previous reports, we found interaction between prematurity/permanent hypothyroidism and birthweight centile. This finding indicates different maturity levels of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis in small for gestational age babies [

20,

21]. This may be attributed to genetic factors, maternal nutritional status, placental function and transfer of nutrients, intrauterine hormones and growth factors [

22].

The prevalence of TCH varies globally, probably due to differences in iodine intake. For example, TCH accounts for 5–65% of diagnosed congenital hypothyroidism (CH) cases worldwide. In North America, where iodine sufficiency has been established for many years, TCH prevalence is approximately 10% [

23,

24]. Neonatal thyroid is particularly susceptible to iodine deficiency due to its low iodine content at birth and higher iodine turnover compared to adults [

1]. Increased iodine requirements during the neonatal period may prevent some neonates with underlying vulnerabilities from developing normal thyroid function, necessitating levothyroxine treatment. A subset of these children eventually regains normal thyroid function and discontinue treatment [

6]. Indicators of TCH include lower levothyroxine requirements during treatment, lower TSH levels at diagnosis, a normally positioned thyroid gland, lower screening TSH levels, higher FT4 levels at diagnosis, low birthweight, male gender, and the absence of TSH elevation during treatment [

25,

26].

The newborn screening program, initiated in Greece in September 1979 and performed in the ICH, has significantly improved child health. However, comparing our data with earlier Greek reports on TCH is challenging due to differences in study designs, cutoff thresholds, and data presentation. Early studies used higher TSH thresholds (≥30 mU/ml) and reported recall cases only [

9]. Subsequent studies lowered TSH thresholds to 20 mU/L, leading to more accurate detection [

10]. The most recent study in 2010 estimated the overall prevalence of TCH as 1:14,154, including cases from all causative factors [

11]. The commonest cause of CH in Greece is ectopy of the thyroid gland followed by aplasia of the thyroid [

27]. In the current study, we excluded TCH cases influenced by exogenous maternal factors (e.g., maternal thyroid disease or goitrogens) to identify a “Target Group” with TCH attributable solely to insufficient iodine intake. The observed prevalence of TCH in relation to the total number of detected cases with CH is 1:6. Meanwhile, the noted incidence of TCH in relation to births is 1:3061. For the Target Group of our study we found an incidence of TCH in relation to the total detected cases with CH to be 1:21 and the incidence in relation to births at 1:10000. The prevalence and incidence rates of TCH in this group therefore reflect the sufficient iodine intake in Greece.

Regarding gender, the only determining factor is female sex for PCH. This finding is in accordance with previous reports [

28]. The preponderance of female cases is mostly associated with dysgenesis of the thyroid gland [

27,

29].

Despite improvements in iodine status across Europe, including the Balkan Peninsula, iodine deficiency (ID) remains a concern in some regions. In Greece, efforts to address ID began approximately 50 years ago, when iodopenic goiter was still endemic [

30,

31]. Earlier studies reported urine iodine concentrations (UIC) ranging from 20 to 50 µg/L, indicating moderate to severe ID. Gradual improvements have been achieved through iodized salt use, better transportation, and higher living standards. Recent reports suggest that Greece is now iodine-replete, though mild ID persists in some areas [

15,

32]. A study conducted in Athens in 2012 reported that over 50% of pregnant women had UIC <100 µg/L, with one-third having UIC <50 µg/L, indicating mild to moderate ID [

13]. A nationwide survey in 2018 found a median UIC of 127.1 µg/L confirming adequate iodine intake overall [

12]. The scattered distribution of TCH cases in our Target Group aligns with these findings, suggesting local variations in iodine intake.

We strongly support the suggestion by the 2020–2021 updated European CH consensus guideline, for retesting TSH levels at the second postnatal week of life or 2 weeks after the first screening in preterm and low birth weight infants [

33,

34].

Our study’s main strength is the identification of TCH cases solely attributable to insufficient iodine intake, separated from other causative factors. This distinction allows for a detailed comparison of characteristics and contributing factors. However, limitations include the retrospective design and missed cases due to challenges in follow-up, particularly among transient populations, especially immigration flows from Asia and residents of remote areas.

5. Conclusions

Our findings support that prematurity is the main factor for TCH in a recently iodine-replete country such as Greece. The findings emphasize the importance of iodine sufficiency during pregnancy and neonatal life. The increased global prevalence of CH since 1979, particularly in regions like the Eastern Mediterranean area, highlights the importance of improved detection through lower screening thresholds and advances in screening methods. Factors contributing to this increase include higher preterm birth rates and improved neonatal survival. They also underscore the need for robust follow-up programs and the development of guidelines for the management of CH. Future efforts should focus on addressing iodine deficiency in vulnerable populations and improving access to healthcare services for comprehensive newborn screening.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Eftychia Koukkou, Christina Kanaka-Gantenbein and Kostas Markou; Data curation, Eftychia Koukkou, Panagiotis Girginoudis, Michaela Nikolaou, Anna Taliou, Alexandra Tsigri and Danae Barlaba; Formal analysis, Marianna Panagiotidou and Ioannis Ilias; Methodology, Eftychia Koukkou and Kostas Markou; Supervision, Eftychia Koukkou, Christina Kanaka-Gantenbein and Kostas Markou; Visualization, Marianna Panagiotidou; Writing – review & editing, Kostas Markou.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Child Health (Decision Number 740A/16.7.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Delange, F. “Screening for congenital hypothyroidism used as an indicator of the degree of iodine deficiency and of its control.” Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association vol. 8,12 (1998): 1185-92. [CrossRef]

- Nazeri, P et al. “Neonatal thyrotropin concentration and iodine nutrition status of mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” The American journal of clinical nutrition vol. 104,6 (2016): 1628-1638. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M et al. “Iodine deficiency in pregnant women in Europe.” The lancet. Diabetes & endocrinology vol. 3,9 (2015): 672-4. [CrossRef]

- Berg, V et al. “Thyroid homeostasis in mother-child pairs in relation to maternal iodine status: the MISA study.” European journal of clinical nutrition vol. 71,8 (2017): 1002-1007. [CrossRef]

- Peters, C and Schoenmakers N. “MECHANISMS IN ENDOCRINOLOGY: The pathophysiology of transient congenital hypothyroidism.” European journal of endocrinology vol. 187,2 R1-R16. 20 Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Markou, KB et al. “Hyperthyrotropinemia during iodide administration in normal children and in children born with neonatal transient hypothyroidism.” The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism vol. 88,2 (2003): 617-21. [CrossRef]

- Delange, F. Delange, F. “The disorders induced by iodine deficiency.” Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association vol. 4,1 (1994): 107-28. [CrossRef]

- Tylek-Lemańska, D et al. “Iodine deficiency disorders incidence in neonates based on the experience with mass screening for congenital hypothyroidism in southeast Poland in the years 1985-2000.” Journal of endocrinological investigation vol. 26,2 Suppl (2003): 32-8. in the Years 1985-2000." Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 26, 2003, pp. 32-38.

- Mengreli, C et al. “Neonatal screening for hypothyroidism in Greece.” European journal of pediatrics vol. 137,2 (1981): 185-7. [CrossRef]

- Mengreli, C et al. “The screening programme for congenital hypothyroidism in Greece: evidence of iodine deficiency in some areas of the country.” Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway: 1992). Supplement vol. 394 (1994): 47-51. [CrossRef]

- Mengreli, C et al. “Screening for congenital hypothyroidism: the significance of threshold limit in false-negative results.” The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism vol. 95,9 (2010): 4283-90. [CrossRef]

- Koukkou, E et al. “Pregnant Greek Women May Have a Higher Prevalence of Iodine Deficiency than the General Greek Population.” European thyroid journal vol. 6,1 (2017): 26-30. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, Elizabeth N et al. “Perchlorate and thiocyanate exposure and thyroid function in first-trimester pregnant women from Greece.” Clinical endocrinology vol. 77,3 (2012): 471-4. [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/SPO03/- (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Koutras, D et al. “Greece is iodine sufficient.” Lancet (London, England) vol. 362,9381 (2003): 405-6. [CrossRef]

- Delange, F et al. “Increased risk of primary hypothyroidism in preterm infants.” The Journal of pediatrics vol. 105,3 (1984): 462-9. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R et al. “Dynamic Screening of Thyroid Function for the Timely Diagnosis of Congenital Hypothyroidism in Very Preterm Infants: A Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study.” Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association vol. 33,9 (2023): 1055-1063. [CrossRef]

- Nordenberg, D. , et al. "Iodine Deficiency in Europe: A Continuing Concern." Edited by F. Delange, J. T. Dunn, and D. Glinoer, Plenum Press, 1993, pp. 211-218.

- Nazeri, Pantea et al. “Neonatal thyrotropin concentration and iodine nutrition status of mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” The American journal of clinical nutrition vol. 104,6 (2016): 1628-1638. [CrossRef]

- Klosinska, M et al. “Congenital Hypothyroidism in Preterm Newborns - The Challenges of Diagnostics and Treatment: A Review.” Frontiers in endocrinology vol. 13 860862. 18 Mar. 2022022. [CrossRef]

- Bagnoli, F et al. “Thyroid function in small for gestational age newborns: a review.” Journal of clinical research in pediatric endocrinology vol. 5 Suppl 1,Suppl 1 (2013): 2-7. [CrossRef]

- Gluckman, PD, and Harding, JE. “The physiology and pathophysiology of intrauterine growth retardation.” Hormone research vol. 48 Suppl 1 (1997): 11-6. [CrossRef]

- Burrow GN, Dussault JH “Neonatal Thyroid Screening. The frequency of transient primary hypothyroidism is almost 8 times higher in Europe than in North America” Raven Press, New York, 1980, pp 1-322.

- Burns, Robert et al. “Can neonatal TSH screening reflect trends in population iodine intake?”. Thyroid: official journal of the American Thyroid Association vol. 18,8 (2008): 883-8. [CrossRef]

- Tuli, Gerdi et al. “Diagnostic Re-Evaluation and Potential Predictor Factors of Transient and Permanent Congenital Hypothyroidism in Eutopic Thyroid Gland.” Journal of clinical medicine vol. 10,23 5583. 27 Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kara, Cengiz et al. “Transient Congenital Hypothyroidism in Turkey: An Analysis on Frequency and Natural Course.” Journal of clinical research in pediatric endocrinology vol. 8,2 (2016): 170-9. [CrossRef]

- Panoutsopoulos, G et al. “Scintigraphic evaluation of primary congenital hypothyroidism: results of the Greek screening program.” European journal of nuclear medicine vol. 28,4 (2001): 529-33. [CrossRef]

- Hashemipour, M et al. “A Systematic Review on the Risk Factors of Congenital Hypothyroidism”. Journal of Pediatrics Review. vol.7 (2019): 199-210. [CrossRef]

- Castanet, M et al. “Nineteen years of national screening for congenital hypothyroidism: familial cases with thyroid dysgenesis suggest the involvement of genetic factors.” The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism vol. 86,5 (2001): 2009-14. [CrossRef]

- Malamos, B et al. “Endemic goiter in Greece: epidemiologic and genetic studies.” The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism vol. 26,7 (1966): 688-95. [CrossRef]

- Beckers, C et al. “The effects of mild iodine deficiency on neonatal thyroid function.” Clinical endocrinology vol. 14,3 (1981): 295-9. [CrossRef]

- Michalaki, Marina et al. “The odyssey of nontoxic nodular goiter (NTNG) in Greece under suppression therapy, and after improvement of iodine deficiency.” Thyroid” vol. 18,6 (2008): 641-5. [CrossRef]

- van Trotsenburg, Paul et al. “Congenital Hypothyroidism: A 2020-2021 Consensus Guidelines Update-An ENDO-European Reference Network Initiative Endorsed by the European Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and the European Society for Endocrinology.” Thyroid”: vol. 31,3 (2021): 387-419. [CrossRef]

- Boros E et al.Delayed Thyrotropin Rise in Preterm Newborns: Value of Multiple Screening Samples and of a Detailed Clinical Characterization Thyroid Vol. 35, No. 7 738-747. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).