Submitted:

19 August 2025

Posted:

20 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, Z.; Drury, C.F.; Yang, X.; Reynolds, W.D. Water-soluble carbon and the carbon dioxide pulse are regulated by the extent of soil drying and rewetting. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2014, 78, 1267–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnard, R.L.; Blazewicz, S.J.; Firestone, M.K. Rewetting of soil: revisiting the origin of CO2 emissions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 147, 107819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, H.F. The effect of soil drying on humus decomposition and nitrogen availability. Plant Soil 1958, 10, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Haney, R.L.; Hons, F.M.; Zuberer, D.A. Determination of microbial biomass and nitrogen mineralization following rewetting of dried soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1996, 60, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, R.L.; Brinton, W.F.; Evans, E. Soil CO2 respiration: comparison of chemical titration, CO2 IRGA analysis and the Solvita gel system. Renew. Ag. Food Syst. 2008, 23, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, G.M.; Kitchen, N.R.; Veum, K.S.; Camberato, J.J.; Ferguson, R. B.; Fernandez, F.G.; Franzen, D.W.; Laboski, C.A.M.; Nafziger, E.D.; Sawyer, J.E.; Yost, M. Relating four-day soil respiration to corn nitrogen fertilizer needs across 49 U.S. Midwest fields. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marando, G.; Jimenez, P.; Rosa, R.; Julia, M.; Ginovart, M.; Bonmati, M. Effects of air-drying and rewetting on extractable organic carbon, microbial biomass, soil respiration, and β-glucosidase and β-galactosidase activities of minimally disturbed soils under Mediterranean conditions. In Soil enzymology in the recycling of organic wastes and environmental restoration; Trasar-Cepeda, C., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Karlen, D.L.; Mausbach, M.J.; Doran, J.W.; Cline, R.G.; Harris, R.F.; Schuman, G.E. Soil quality: a concept, definition, and framework for evaluation (a guest editorial). Soil Sci. Soc. of Am. J. 1997, 61, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zornoza, R.; Acosta, J.A.; Bastida, F.; Domínguez, S.G.; Toledo, D.M.; Faz, A. Identification of sensitive indicators to assess the interrelationship between soil quality, management practices and human health. Soil 2015, 1, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Quinones, V.; Stockdale, E.A.; Banning, N.C.; Hoyle, F.C.; Sawada, Y.; Wherrett, A.D.; Jones, D.L.; Murphy, D.V. Soil microbial biomass—interpretation and consideration for soil monitoring. Soil Res. 2011, 49, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J. Short-term C mineralization (aka the flush of CO2) as an indicator of soil biological health. CABI Reviews: perspectives in agriculture, veterinary science, nutrition, and natural resources. 2018, 13, 17. [Google Scholar]

- McGonigle, T.P.; Turner, W.G. Grasslands and croplands have different microbial biomass carbon levels per unit of soil organic carbon. Agriculture 2017, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Haney, R.L.; Honeycutt, C.W.; Schomberg, H.H.; Hons, F.M. Flush of carbon dioxide following rewetting of dried soil relates to active organic pools. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Pershing, M.R.; Crozier, C.; Osmond, D.; Schroeder-Moreno, M. Soil-test biological activity with the flush of CO2: I. C and N characteristics of soils in corn production. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2018, 82, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Dalal, R.C.; Moody, P.W.; Smith, C.J. Relationships of soil respiration to microbial biomass, substrate availability and clay content. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, K.; McGonigle, T.; Koiter, A. Microbe biomass in relation to organic carbon and clay in soil. Soil Syst. 2020, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 3. Chemical Methods; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zibilske, L.M. Carbon mineralization. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Microbiological and biochemical properties; Weaver, R.W., Ed.; Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, G.W.; Or, D. Particle-size analysis. In Methods of soil analysis. Part 4. Physical methods, Dane, G.H., Topp, G.C., Eds.; Soil Science Society of America, Madison, WI, USA, 2002; pp. 255–293.

- Crittenden, S.; Cavers, C.; Xing, Z. The effect of four tillage systems on agronomic properties and soil health indicators in southern Manitoba. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2024, 104, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, S.M.; Nathan, M.V. Soil organic matter. In Recommended chemical soil test procedures for the North Central Region; North Central Regional Research Publication, Missouri Agricultural Experimental Station SB1001, 2015.

- Zar, J.H. Statistical methods, 5th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trumbore, S. Age of soil organic matter and soil respiration: radiocarbon constraints on belowground C dynamics. Ecol. Appl. 2000, 10, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennock, D.; Bedard-Haughn, A.; Viaud, V. Chernozemic soils of Canada: genesis, distribution, and classification. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2011, 91, 710–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikha, M.M.; Rice, C.W.; Milliken, G.A. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization as affected by drying and wetting cycles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2005, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinton, W.F. Laboratory soil handling affects CO2 respiration, amino-N and water stable aggregate results. Agri. Res. and Tech. 2020, 24, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J. Probing deep to express root-zone enrichment of soil-test biological activity on southeastern U.S. farms. Agric. Environ. Lett. 2022, 7, e20087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Haney, R.L.; Honeycutt, C.W.; Arshad, M.A.; Schomberg, H.H.; Hons, F.M. Climatic influences on active fractions of soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagal, E. Measurement of microbial biomass in rewetted air-dried soil by fumigation-incubation and fumigation-extraction techniques. Soil Bio. Biochem. 1993, 25, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R. Response of osmolytes in soil to drying and rewetting. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 70, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R. Do microbial osmolytes or extracellular depolymerization products accumulate as soil dries. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 98, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.L.; Weitz, K.K.; Thompson, A.M.; Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.L.; Lipton, M.S. Real-time and rapid respiratory response of the soil microbiome to moisture shifts. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franzluebbers, A.J. Potential C and N mineralization and microbial biomass from intact and increasingly disturbed cores of varying texture. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1999, 31, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, A.; Marschner, P. Drying and rewetting frequency influences cumulative respiration and its distribution over time in two soils with contrasting management. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 72, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miner, G.L.; Delgado, J.A.; Ippolito, J.A.; Stewart, C.E. Soil health management practices and crop productivity. Agric. Environ. Lett. 2020, 5, e20023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparda, A.; Miller, R.O.; Anderson, G.; Hsieh, Y.-P. Real-time soil CO2 respiration rate determination and the comparison between the infrared gas analyzer and microrespirometer (MicroRes®) methods. Comm. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2017, 48, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Bradford, M.A.; Wood, S.A. Global meta-analysis of the relationship between soil organic matter and crop yields. Soil 2019, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Bradford, M.A.; Augarten, A.J.; Cooley, E.T.; Radatz, A.M.; Radatz, T.; Ruark, M.D. Positive associations of soil organic matter and crop yields across a regional network of working farms. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2022, 86, 384–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, T.M.; Mooshammer, M.; Socolar, Y.; Calderon, F.; Cavigelli, M.A.; Culman, S.W.; Deen, W.; Drury, C.F.; Garcia y Garcia, A.; Gaudin, A.C.M.; Harkcom, W.S.; Lehman, R.M.; Osborne, S.L.; Robertson, G.P.; Salerno, J.; Schmer, M.R.; Strock, J.; Grandy, A.S. Long-term evidence shows that crop-rotation diversification increases agricultural resilience to adverse growing conditions in North America. One Earth 2020, 2, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

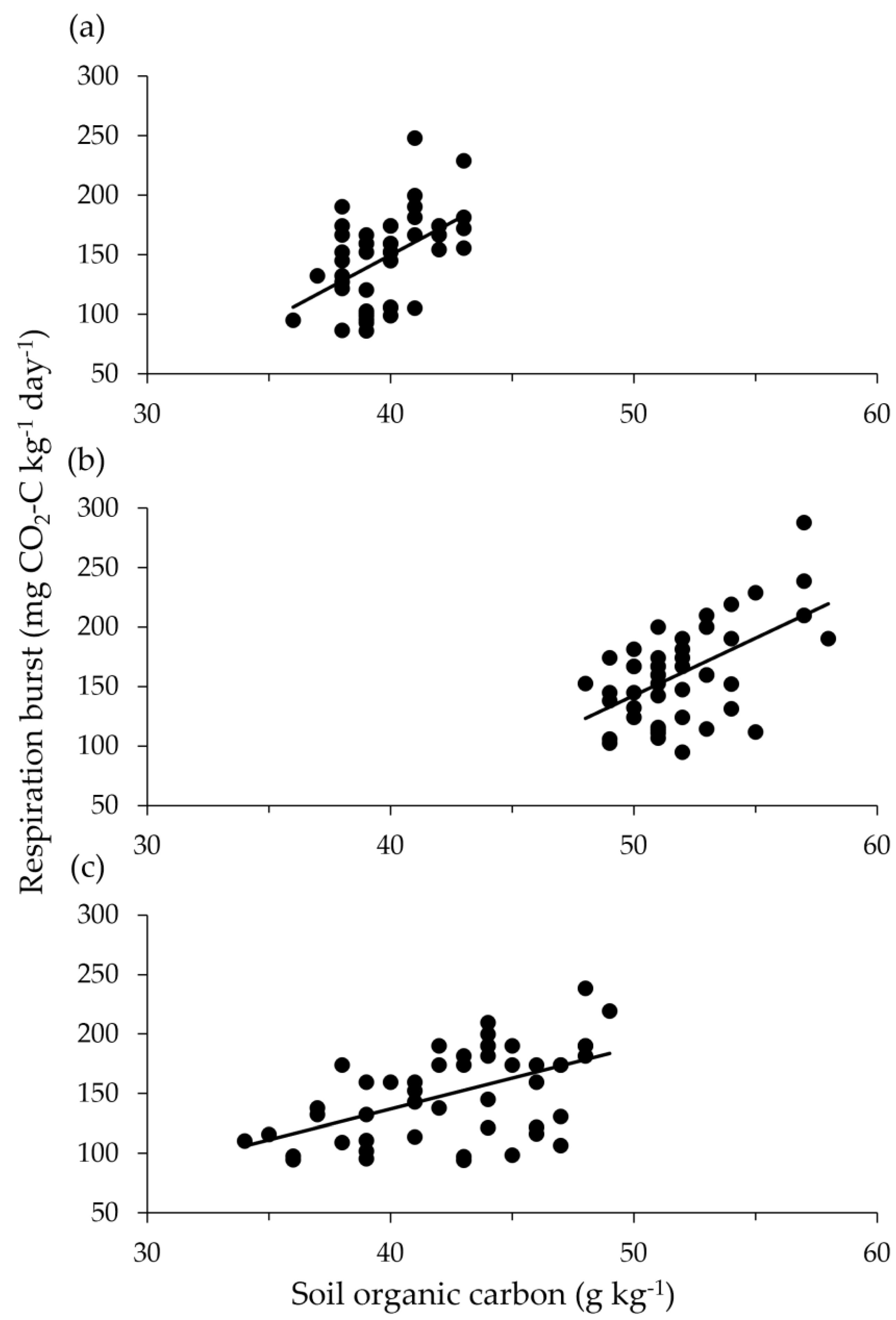

| (a) | |||||

| Source | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

| Regression | 1 | 11116.6 | 11116.6 | 642.5 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 154 | 2664.7 | 17.3 | ||

| Total | 155 | 13781.3 | |||

| (b) | |||||

| Source | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

| Regression | 1 | 535.9 | 535.9 | 67.6 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 22 | 174.4 | 7.9 | ||

| Total | 23 | 710.3 | |||

| (c) | |||||

| Source | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

| Regression | 1 | 1973.6 | 1973.6 | 53.3 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 22 | 814.9 | 37.0 | ||

| Total | 23 | 2788.5 | |||

| Site | % sand | % silt | % clay | Texture |

| BRP | 54.7 | 29.6 | 15.7 | sandy loam |

| Pasture A | 90.0 | 4.2 | 5.8 | sand |

| Pasture B | 53.3 | 37.5 | 9.2 | sandy loam |

| (a) | |||||

| Source | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

| Regression | 1 | 15999.5 | 15999.5 | 15.1 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 46 | 48630.2 | 1057.2 | ||

| Total | 47 | 64629.7 | |||

| (b) | |||||

| Source | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

| Regression | 1 | 25268.2 | 25268.2 | 22.4 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 46 | 51937.3 | 1129.1 | ||

| Total | 47 | 77205.5 | |||

| (c) | |||||

| Source | DF | SS | MS | F | P |

| Regression | 1 | 19234.7 | 19234.7 | 17.9 | <0.001 |

| Residual | 46 | 49369.8 | 1073.3 | ||

| Total | 47 | 68604.5 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).