Introduction

The need for more cost-effective, noninvasive, and clinically applicable methods that would ultimately increase the live birth rates and reduce the number of IVF cycles a couple undergo to achieve a family has been growing. The technological road block is not in oocyte fertilisation, nor

in vitro cultured growth to blastocyst stage; but in identifying the IVF concieved blastocysts/embryos that will implant and develop succesfully after transfer to the uterus. In this respect biological genetic composition of IVF blastocyst have been assessed prior to transfer via PGT-A. However, this has had only very limited success in improving success rates [

1,

2]. The complementary focus has been to look at the metabolic features of blastocysts [

3]. More so than with blastocyst biopsy, the challenge has been to assess the metabolic signature of a blastocyst without destroying or damaging it. In this respect Non-invasive screening of Spent Blastocyst Media (SBM) has seen advancements [

4,

5]. The ability to detect and measure multiple analytes simultaneously using modern mass spectrometry tools has made this metabolic profiling of blastocyst prior to transfer feasiable [

3]. Current developments in high-throughput, clinically applicable, hardware and bioinformatic tools; getting closer to the goal of increasing live birth rates [

3]. However,

in vitro environment variables, such as culture media composition, temperature, humidity, and air quality, potentially impact the differences in the proteomic/metabolomic spectral profiles in mass spectrmetry studies [

6]. They have been shown to affect epigenetics and, subsequently, embryo morphology, developmental kinetics, physiology, and metabolism [

7].

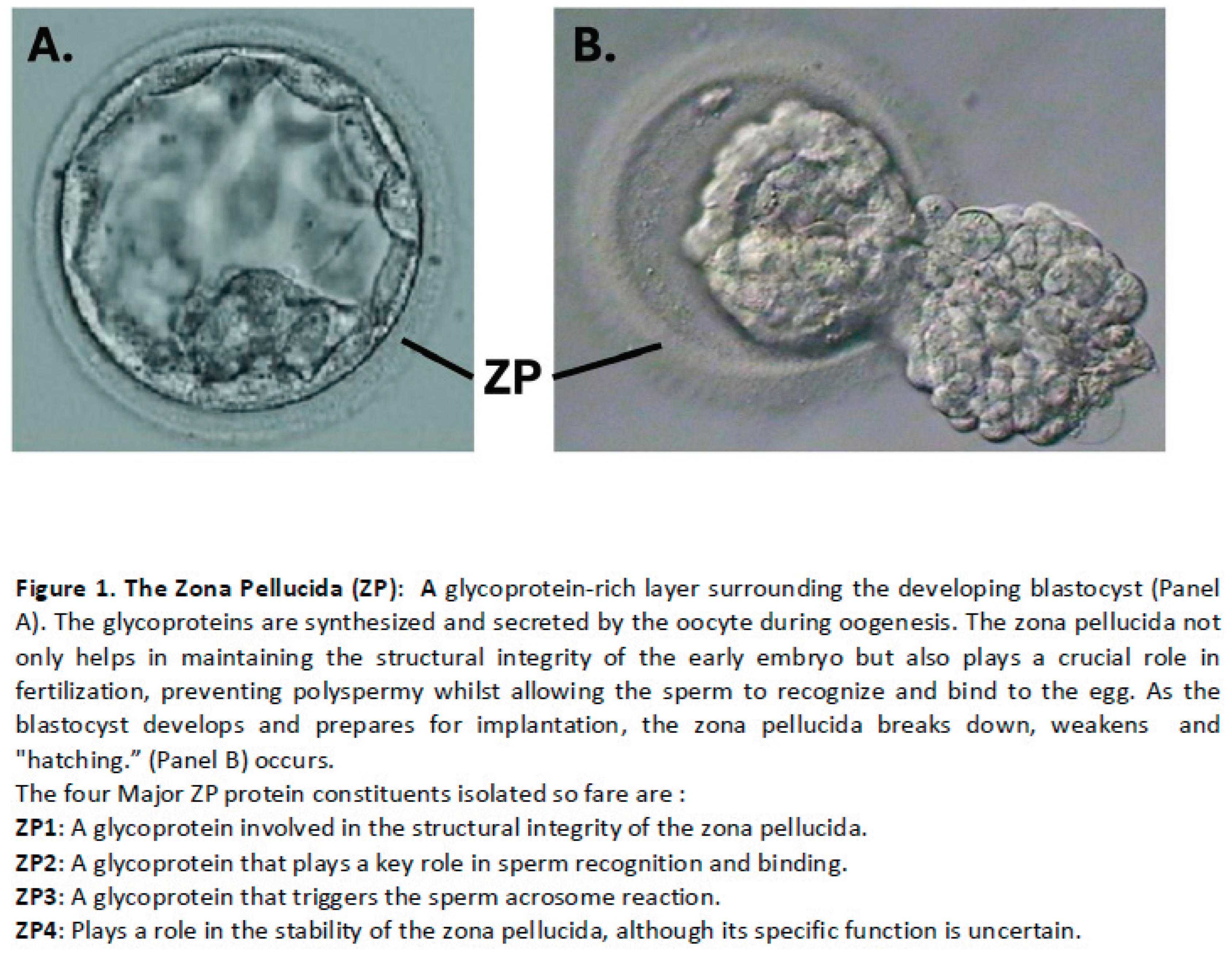

Besides environmental factors, the differences in the protocol are also fundamental. One of such components is the hatching of the embryo prior to implantation. After fertilization the zona pellucida (ZP), a glycoprotein coat surrounding the oocyte, and then the embryo is there to protect the embryo from premature implantation, multiple fertilization, microorganisms and immune cells prior to implantation while traversing through the female reproductive tract [

8] (

Figure 1). The embryo hatches from ZP around the late blastocyst stage, maximizing communication between endometrial and trophoblast cells, orchestrating embryo adhesion.

In vivo, spontaneous hatching occurs on day six or seven following fertilization.

In vitro it happens at about day five through six, however, many clinics implant embryos at day three, hoping for spontaneous hatching in the uterus [

9]. Nevertheless, hatching failure may occur, so the technique of Assisted Hatching (AH) was introduced to thin or break ZP, facilitating the hatching process. AH was first reported over three decades ago, in 1988, where the method was employed to facilitate sperm penetration [

10]. Assisted hatching disrupts or thins the surface of ZP by mechanical, chemical or, most commonly, laser-mediated procedures [

11]. A Cochrane meta-analysis review analyzing the outcomes following AH, that included 31 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), concluded that AH may lead to an increase of the clinical pregnancy rate by 12% to 57% [

12]. Thus for a clinic peformic 1000 IVF cycles per year with a 30% live birth rate, this could mean an additional 36 to 171 clinical pregnancies. However, a more recent Cochrane meta-analysis, which included 39 RCTs, has reported that majority of the published studies are heavily biased. The authors of the latest Cochrane reviews suggested that studies have had a high heterogenicity and previous conclusions may have been based on poor evidence [

13]. Thus, the value of AH for any purpose other than assisted insemination or blastocyst cell sampling is controversial.

Nevertheless, some quality embryos fail to implant due to unsuccessful hatching. Therefore, AH has been employed to improve the implantation capacity of an embryo, especially with patients over 35 years old, with particularly thick ZP, or for embryos that have been subject to freeze-thaw cycle as this also contributes to a harder ZP [

14]. For the embryos with a breached integrity of the ZP, nutrients and growth factors in culture media are more readily available for the embryo, and metabolites can be exchanged easier. Ultimately, this two-way exchange of molecules between media and embryo changes the composition of the SBM. Given the bi-directional transport is altered by the hatching from the ZP, hatching of an embryo, both spontaneous or assisted, will impact on the mass spectral profile of the SBM. We hypothesized that hatching may subsequently lead to a better-quality spectral profile and therefore better prediction models based on mass spectrometry data features. Ultimately, this would translate into an increase in live birth rate.

The aim of the study was to analyse retrospective SBM samples of hatched and unhatched embryos for the differences in the mass spectral profile and the predictive modeling potential for a defined outcome, an intrauterine pregnancy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

We have re-examined the previously collected data, slicing the database, based on a hatching variable and examining its impact. SBM were collected from women undergoing routine-assisted reproduction cycles at the Virginia Center for Reproductive Medicine (VCRM), between March 2014 and July 2021.

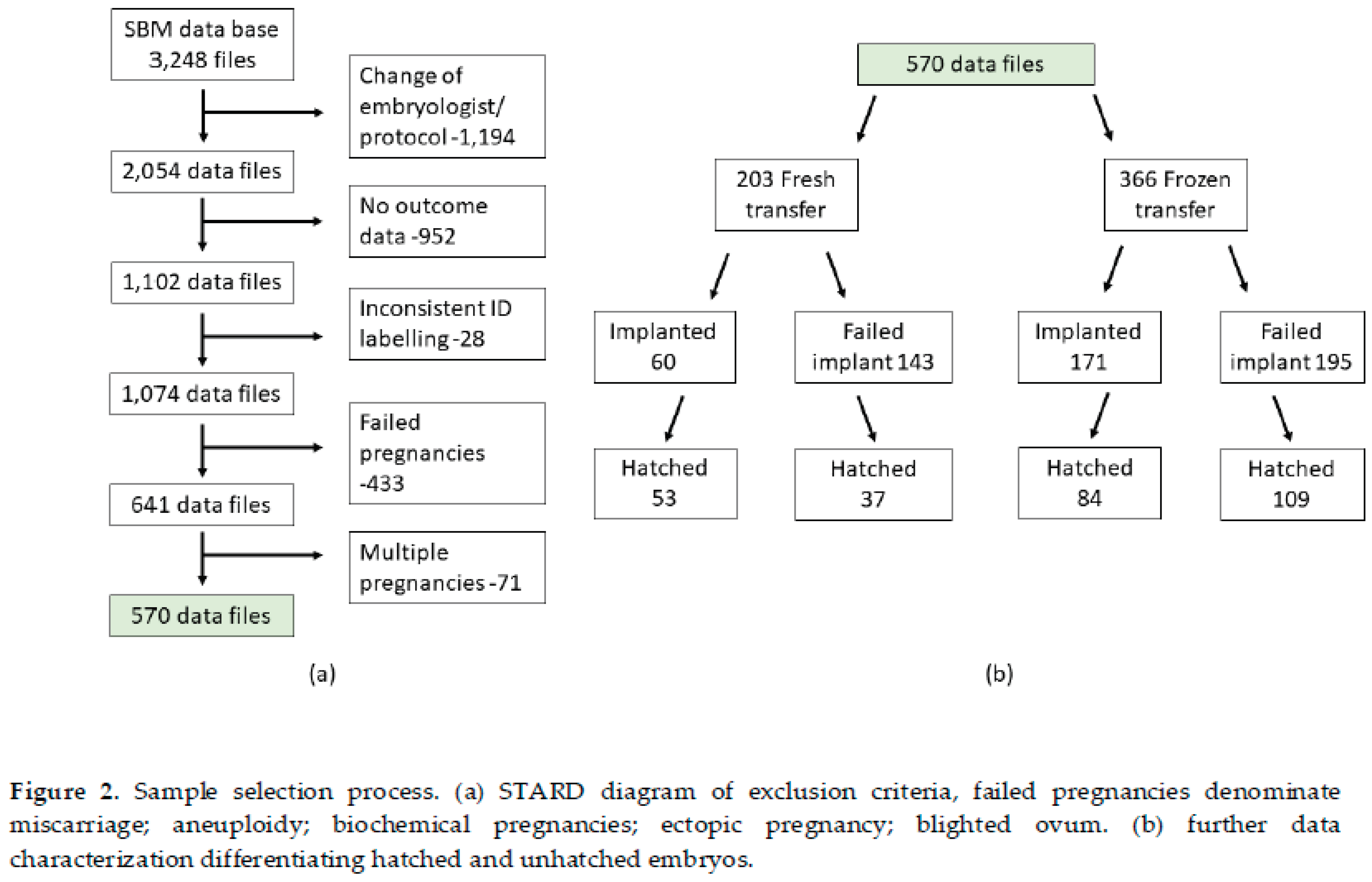

A cohort of 3248 SBM samples had been subjected to a standardized mass spectral analysis. Oocyte retrieval, embryo culturing and culture media collection were performed as previously described [

15]. Sample selection for the study is represented in the STARD diagram of sample inclusion criteria, together with further data characterisation (

Figure 2). The final number of spectral data was 570 samples (of which 283, were hatched embryos).

All couples gave consent for the culture media to be used. The study was approved by VCRM’s Institutional Review Board (fshararaVCRMED20230126).

Twenty to fifty microliters from each SBM were collected in an Eppendorf tube and immediately frozen at –20 °C until shipped to the UK for analysis. Each SBM corresponded to only one blastocyst. A media sample was used as a negative control. All procedures including ICSI, biopsies, and ET were performed by the same embryologist. During the study period, the same continuous media (Global, Life Global, USA) was used for all embryo growth.

2.2. MALDI-ToF Mass Spectrometry

SBM was thawed, thoroughly mixed, diluted 1:10 in a mass spectrometry grade water (Romil, UK). Pre-processed samples were plated on a 48 well stainless-steel target plate using a sandwich technique with α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) matrix. Samples were analysed using MALDI-ToF mass spectrometry (MALDI 8020, Shimadzu, UK). The instrument was externally calibrated by Bradykinin Fragment 1–7 (756.4 Da) (ProteoMass, Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich, Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, USA). Data were collected in a mass range of 200–2000 m/z. A total of 8500 shots per sample were collected in a positive linear mode with a 100 Hz solid-state laser (355 nm). Averaged data were exported in mzML format.

2.3. Bioinformatics

The spectral quality was evaluated based on the identification of a minimum of seven peaks with a signal to noise ratio higher than 5-fold. Normalization to total ion count, spectral alignment with a reference peak (379 m/z), and smoothing with Savitzky–Golay filter was performed prior to using a peak detection algorithm [

16]. The reference peak was chosen based on the empirical observation of the prevalence of a peak located at 379 ± 5 m/z that correlated with high quality secreteome MS data in the same experimental conditions [

17]. Upon quality selection, peak heights were systematically extracted from spectral data using a computational pipeline previously described in [

17]. The computational pipeline was implemented using code written in Python version 3.8 and all data visualization using the Python library matplotlib under Jupyter Notebook environment.

2.4. Data Modelling

Implantation potential was modeled by applying supervised machine learning on two build datasets (hatched and unhatched embryos) containing mass spectral features (peak heights) mapped to implanted and not implanted outcomes. Classification models were generated using the MS pattern-based scoring EvA-3 machine learning algorithm, where further explanation and equations can be found [

17]. Briefly, the algorithm learns how to combine peak heights towards building a pattern with optimal predictive performance. The algorithm evaluates the statistical significance of each peak by grouping them into implanted and not implanted embryos outcomes and performs a non-parametric two-tail Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for feature selection. The algorithm also calculates the peak enrichment as a fraction of total detected peaks, combining this information into a classification score that accounts for both peak differences in medians and peak presence based on enrichment.

Probabilities as a function of classification models scores from EvA-3 were calculated according to the following equation:

; where:

P is the probability of implantation in percentage;

S is the score obtained by the classification model;

L, K and C are logistic model parameters that were obtained through fitting the model to data.

Model fitting was performed using the curve fit algorithm from the Scipy optimize Python library.

3. Results

We have previously developed bioinformatic tools for embryo selection based on their ploidy status [

17] and selection of embryo for implantation with the highest potential for intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) [

15], based on the SBM profiles as analysed by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. With a continuous collection of samples, we have expanded the database and were able to further dissect the data based on other variables, without compromising on diagnostic power. In this report, the main goal was the analysis of hatching influence on the quality of the data and subsequently the influence on the predictive value potential.

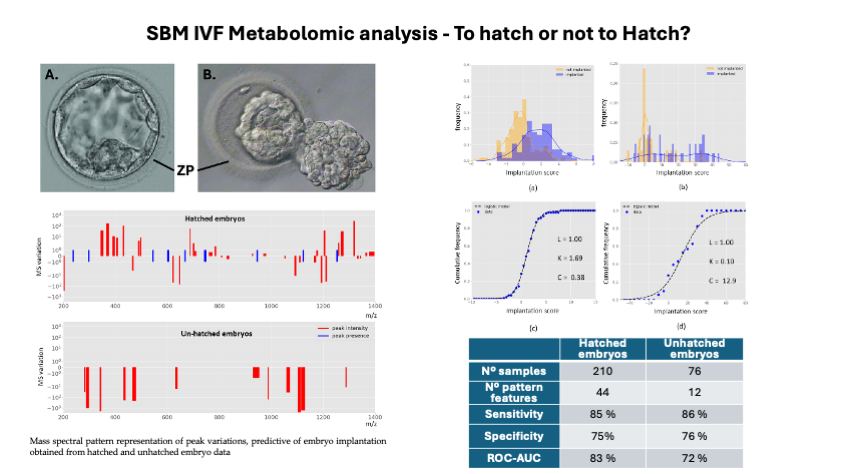

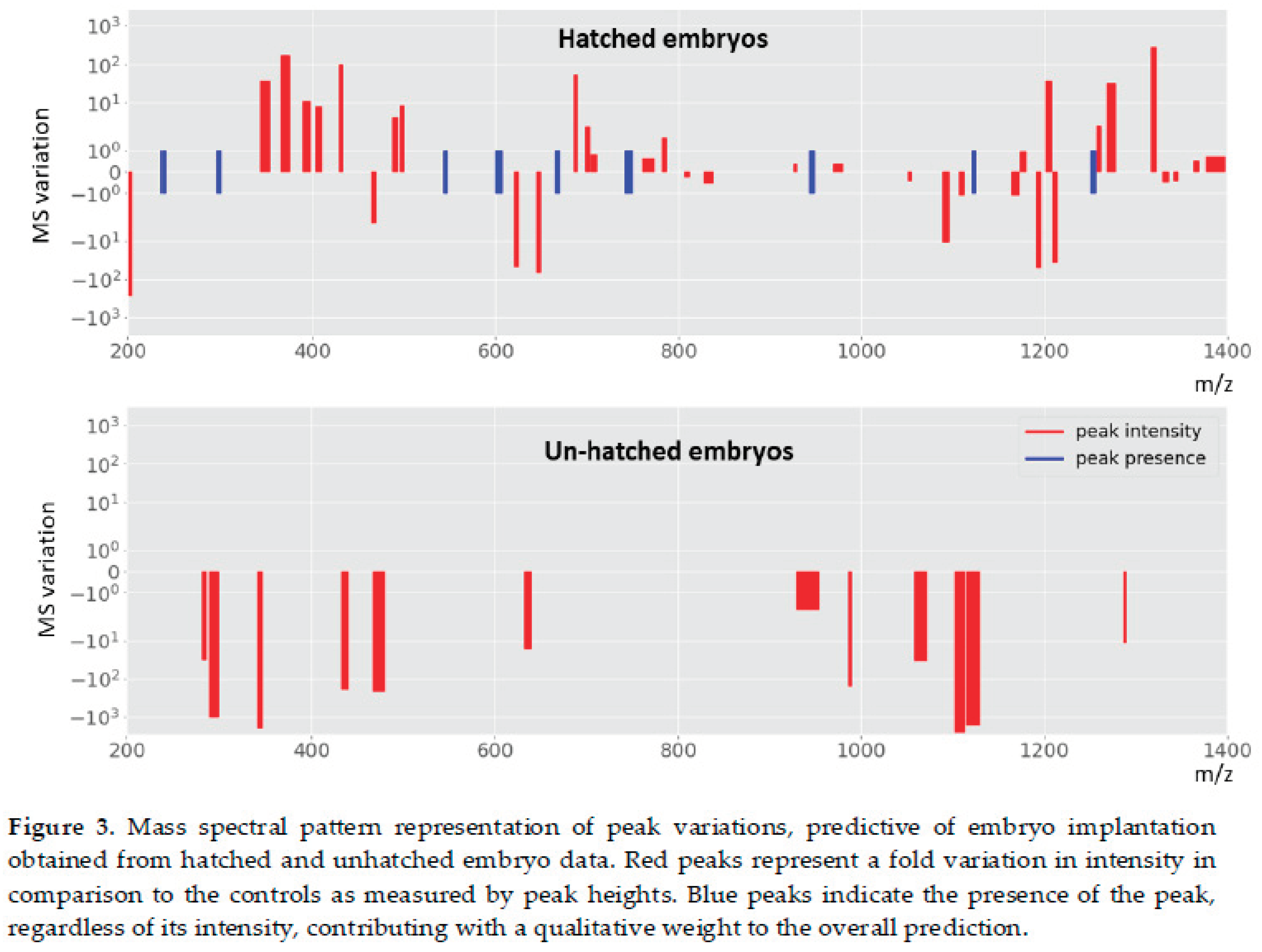

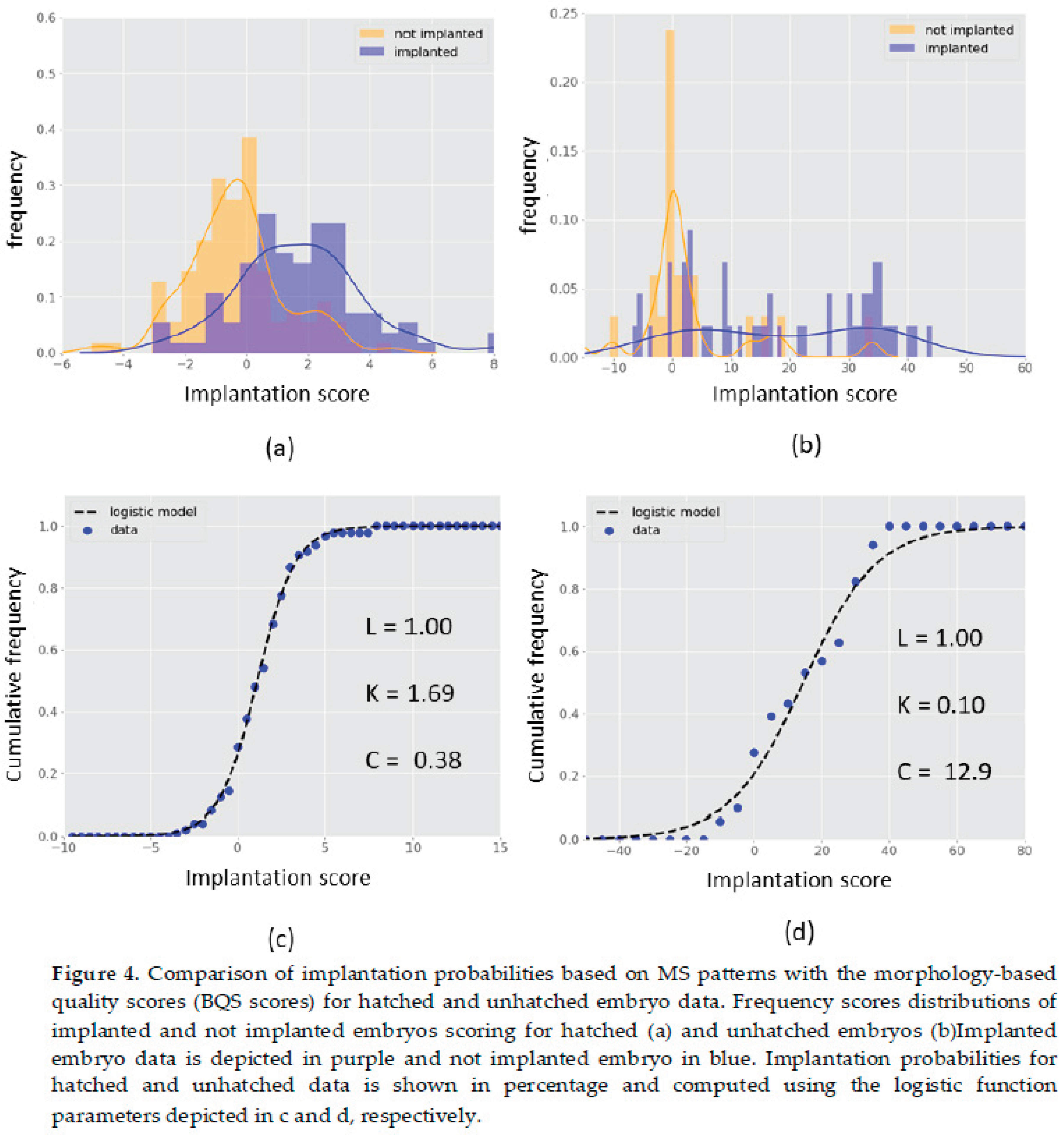

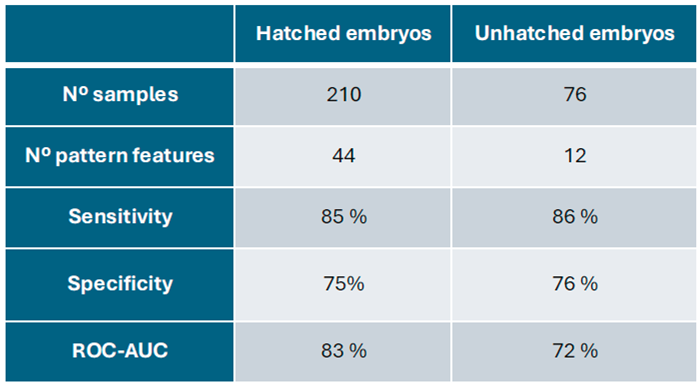

In this work, we applied a machine learning framework on a larger embryo dataset which renders two mass spectral patterns that are predictive of embryo implantation. These patterns are the components of two scoring-based classification models for the embryo implantation outcome. One that is specific for embryo hatching data and another for unhatched embryo data. Both models rendered reasonable and similar predictive performance in terms of their sensitivity and specificity (

Table 1). However, the predictive power is higher for the model generated with hatched embryo data as it gives a better area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC, 83% versus 72%). The obtained patterns associated to these models are represented by relative median fold variations of intensity or enriched peak presence in comparison with not implanted embryo data (controls), found in the region of 200 m/z – 1,400 m/z (

Figure 3). The obtained peak intensity variations in these patterns were quite expressive ranging from 1.3-fold up to three orders of magnitude.

In comparison, we found qualitative and quantitative differences between mass spectral profiles of hatched and unhatched embryos, indicating distinct molecular profiles Hatched embryo profiles were richer in the number of peaks (total of 44) in comparison with unhatched embryo profiles (total of 12). Among these, we identified multiple peaks in particular m/z regions that were not present in unhatched embryo data including peak intensities variation and the presence of specific peaks (

Figure 2). Further, only hatched embryo pattern shows peak increases and the presence of new peaks in comparison with the controls (not implanted data). Interestingly, unhatched embryo pattern is only described by median intensity fold decreases (negative values) in comparison with the controls. This is perhaps due to the bi-directional communication in hatched samples, where particular molecules were able to enter the SBM at the substantial levels to be picked up by the machine learning algorithm as classification features during model development, whereas unhatched embryo profiles only represent key molecular consumption events with predictive capacity.

Based on our classification models, we estimated the implantation probability using a logistic model fit on the models scores and analysed their distribution among implanted and not implanted embryos (

Figure 4). A greater number of significant and distinguishing features has resulted in better data modelling for predicting the implantation potential. The logistic model fit was more accurately represented for the hatched data (

Figure 4c,d) supporting the application of such modelling framework. Cumulative frequency plots show superior data distribution in hatched dataset, unlike unhatched dataset that heterogenous distribution of scores was observed (

Figure 4). Thus, data suggest that embryo hatching leads to richer spectral profiles that are associated with better predictive potential. Finally, using the fitted logistic model equations (see parameters in

Figure 4c and 4d), we computed the implantation probability as a function of models scores for all data. Both hatched and unhatched derived probabilistic models show high discrimination between implanted and not implanted embryos (

Figure 4). Importantly, both probabilistic models show a much higher discrimination between implanted and not implanted embryos in comparison with the currently used embryo quality grading. The BQS was calculated based on the criteria established by Gardner and Schoolcraft, first reported by Rehman

et al. [

18]. Further, our results show that for a > 95% chance of discrimination between implanted and not implanted, the probability threshold is 60% (hatched) and 30% (unhatched), supporting their applicability in IVF as an embryo quality selection index superior to the currently used. Moreover, the 60% probability threshold obtained in hatched embryo is more realistic for embryo selection decision in comparison with the 30% of unhatched supporting the idea that embryo hatching provides additional and relevant predictive information.

4. Discussion

Noninvasive screening has been gaining a lot of attention, for both best embryo selection and aneuploidy screening. Almagor

et al., have investigated the proteome of the hatching blastocysts [

19]. Such proteome/metabolome analysis of the SBM may circumvent the necessity of a biopsy, which could compromise the implantation potential due to induced trauma [

20,

21,

22]. Advantages of noninvasive screening have been discussed previously [3, 23, 24]; but subjective evaluations based on morphology/morpho-kinetics are f[3,23,24lawed by bias and low concordance rates between embryologists [

25]. This has to be eliminated in blastocyst assessment and selection protocols. Therefore, the key aim is to differentiate the implantation ability of morphologically identical (euploid) embryos to improve success rates. Thus, the ability to select the best embryo by noninvasive non-subjective methods is most likely to be made possible by the biochemical analysis of SBM.

Spent blastocyst media (SBM), that would otherwise be discarded, offers a rich source of information without the requirement to disturb, or more invasively take a trophectoderm biopsy from, the developing embryo. More importantly, it has the capacity to differentiate morphologically identical embryos. There are two main approaches to the analysis of SBM. The first is to target and identify the specific biomarkers, which would subsequently be used in targeted assays. Another approach is a spectral pattern correlation to the outcome of interest without the identification of the resolving peaks, not limited to specific biomarkers. Both of these methods could be affected by the changes in the SBM, compromising the detection of metabolomes, proteins, amino acids, cfDNA, mRNA, and other molecules of interest. The role of hatching for the quality of the analysis of the SBM for a noninvasive embryo implantation potential screening has not been previously investigated.

An embryo hatching is a process of blastocyst escape through the ZP, preceding blastocyst expansion in order to establish cell contacts between the trophectoderm and endometrial epithelium. It is a critical pre-requisite for implantation in a receptive endometrium. This process is a chrono-genetically controlled event and may play a role in preventing non-developing/retarded embryos from implanting [

26]. Zona pellucida (ZP) breaking is initiated by blastocyst expansion, creating pressure on the ZP which, together with chemical digestion by lytic enzymes, concludes the hatching process [

27]. Human ZP is a 13–19-μm thick three-dimensional network, composed of carbohydrates and glycoproteins, expressing four specific glycoproteins (ZP1-ZP4) [

28]. This structure ceases to be vital when embryo compaction occurs and structural joints are formed between blastomeres [

14] (see figure 1). As suggested by the pioneers of assisted hatching, breached ZP enhances the molecular exchange between the embryo and its environment [

29]. Several reports have suggested that the ZP is permeable to all substances dissolved in water, including larger molecules such as serum albumin, antibodies, and even some viruses [

30,

31]. However, the size of the molecule is not the only factor influencing ZP permeability; molecular configuration- degree of aggregation and charge characteristics of the molecules are also important factors [

32]. Our earlier studies had shown that the glycoprotein human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG -approximately 36,000 Da) was detected only after the embryo hatched and that proteins of masses higher than 16,000 Da have difficulty crossing the ZP [

33].

Thus, hatching releases molecules to the extra zonal environment. Furthermore, material from fragmented cells that would offer important information of the embryo development potentially enters the SBM after embryo hatching [

9]. Although some authors suggested, that even after hatching, 20% of the embryos do not expel sufficient amounts of material for non-invasive genetic testing [

34], and possibly also for proteomic studies. However, as demonstrated here, the sensitivity of mass spectrometry techniques is such that hatching allows the capture of significantly more data present in the media (

Figure 3).

Proteo-metabolomic technologies such as mass spectrometry offer a fast turnaround time (less than 30 minutes), high throughput, and economically viable options, which in turn will benefit not only clinics but also couples undergoing IVF treatment. Furthermore, “reproductomics” greatly benefit from the increasing technological advancements in the bioinformatics field. New computational approaches, tailored for data obtained from noninvasive sampling generated by mass spectrometry are being created [

35,

36]. With the help of automated bioinformatics pipelines, complex SBM dynamics are being translated into predictive models for the best embryo selection, tailored for the specific needs of an IVF clinic.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated, that SBM from embryos that have been hatched gave rise to much more informative spectra. This, in turn, provides the best chance of detecting metabolic and secretory spectral patterns of functional importance. Furthermore, whether transferring hatched or unhatched blastocyst this work indicates the predictive capacity of SBM mass spectral profiling for embryo implantation potential to be higher than the currently used in most IVF clinics.